ABSTRACT

The complete remineralization of organic matter in anoxic environments relies on communities of microorganisms that ferment organic acids and alcohols to CH4. This is accomplished through syntrophic association of H2 or formate producing bacteria and methanogenic archaea, where exchange of these intermediates enables growth of both organisms. While these communities are essential to Earth’s carbon cycle, our understanding of the dynamics of H2 or formate exchanged is limited. Here, we establish a model partnership between Syntrophotalea carbinolica and Methanococcus maripaludis. Through sequencing a transposon mutant library of M. maripaludis grown with ethanol oxidizing S. carbinolica, we found that genes encoding the F420-dependent formate dehydrogenase (Fdh) and F420-dependent methylene-tetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenase (Mtd) are important for growth. Competitive growth of M. maripaludis mutants defective in either H2 or formate metabolism verified that, across multiple substrates, interspecies formate exchange was dominant in these communities. Agitation of these cultures to facilitate diffusive loss of H2 to the culture headspace resulted in an even greater competitive advantage for M. maripaludis strains capable of oxidizing formate. Finally, we verified that an M. maripaludis Δmtd mutant had a defect during syntrophic growth. Together, these results highlight the importance of formate exchange for the growth of methanogens under syntrophic conditions.

IMPORTANCE In the environment, methane is typically generated by fermentative bacteria and methanogenic archaea working together in a process called syntrophy. Efficient exchange of small molecules like H2 or formate is essential for growth of both organisms. However, difficulties in determining the relative contribution of these intermediates to methanogenesis often hamper efforts to understand syntrophic interactions. Here, we establish a model syntrophic coculture composed of S. carbinolica and the genetically tractable methanogen M. maripaludis. Using mutant strains of M. maripaludis that are defective for either H2 or formate metabolism, we determined that interspecies formate exchange drives syntrophic growth of these organisms. Together, these results advance our understanding of the degradation of organic matter in anoxic environments.

KEYWORDS: formate, metabolism, methanogenesis, syntrophy

INTRODUCTION

Methanogens generate ~80% of the CH4 produced annually on Earth (1) and are essential for the remineralization of organic matter in oxidant-depleted, anoxic environments such as swamps, sediments, rice paddy fields, intestinal tracts of ruminants, and wastewater treatment plants. In these environments, methanogens consume the products of bacterial fermentations to generate CH4; however, key details surrounding this nutrient exchange remain unknown. A better characterization of the interactions between methanogens and fermenting organisms is essential for understanding the role methanogens play in the global carbon cycle.

Several decades after the cultivation of the first methanogens, it was found that many grow in mutualistic partnerships where their ability to produce methane is dependent on a bacterial syntroph producing H2 (2). For example, in the absence of a methanogenic partner, syntrophs cannot ferment ethanol to acetate and H2, which is a thermodynamically unfavorable reaction under standard conditions. However, when a methanogen maintains a low partial pressure of H2, ethanol oxidation becomes favorable (2). While most methanogens can reduce CO2 to CH4 using H2 as an electron donor, many are additionally capable of using alternate electron donors such as formate (Equation 1 & 2 [3]), and many syntrophs can produce formate instead of H2. Due to the low concentrations of intermediates that are maintained during syntrophic growth, it has remained difficult to determine the relative contributions of H2 versus formate exchange to growth (4).

| (1) |

| (2) |

Under typical in situ conditions, the redox potentials of the H+/H2 and CO2/formate couples are similar (EH2 = −358 ± 12 mV and Eformate = −366 ± 19 mV [5]). Therefore, use of either electron donor for methanogenesis results in nearly identical free energy yield. While H2 is traditionally considered the primary electron donor to hydrogenotrophic methanogens (6), recent discoveries suggest an underappreciated importance of formate (7, 8). In Methanoculleus thermophilus and Methanospirillum hungatei, formate dehydrogenase activity is essential for coupling of the first and last step of methanogenesis through flavin-based electron bifurcation (7, 9). Methanococcus maripaludis is also capable of using formate as an electron donor for this reaction (10). A recent metabolic model investigated contributions of H2 and formate to methanogenesis and found that, in addition to acetate and H2, formate-based methanogenesis was a major driver of organic matter remineralization (8). H2 is a small, apolar molecule, so it may be advantageous as a metabolic intermediate in aggregated cultures like flocs or sediments where rapid diffusion between closely associated organisms is favored. Formate may be preferred in aqueous planktonic cultures where solubility of the anion is more important and rapid diffusion of insoluble H2 would be detrimental to growth (4, 11–13).

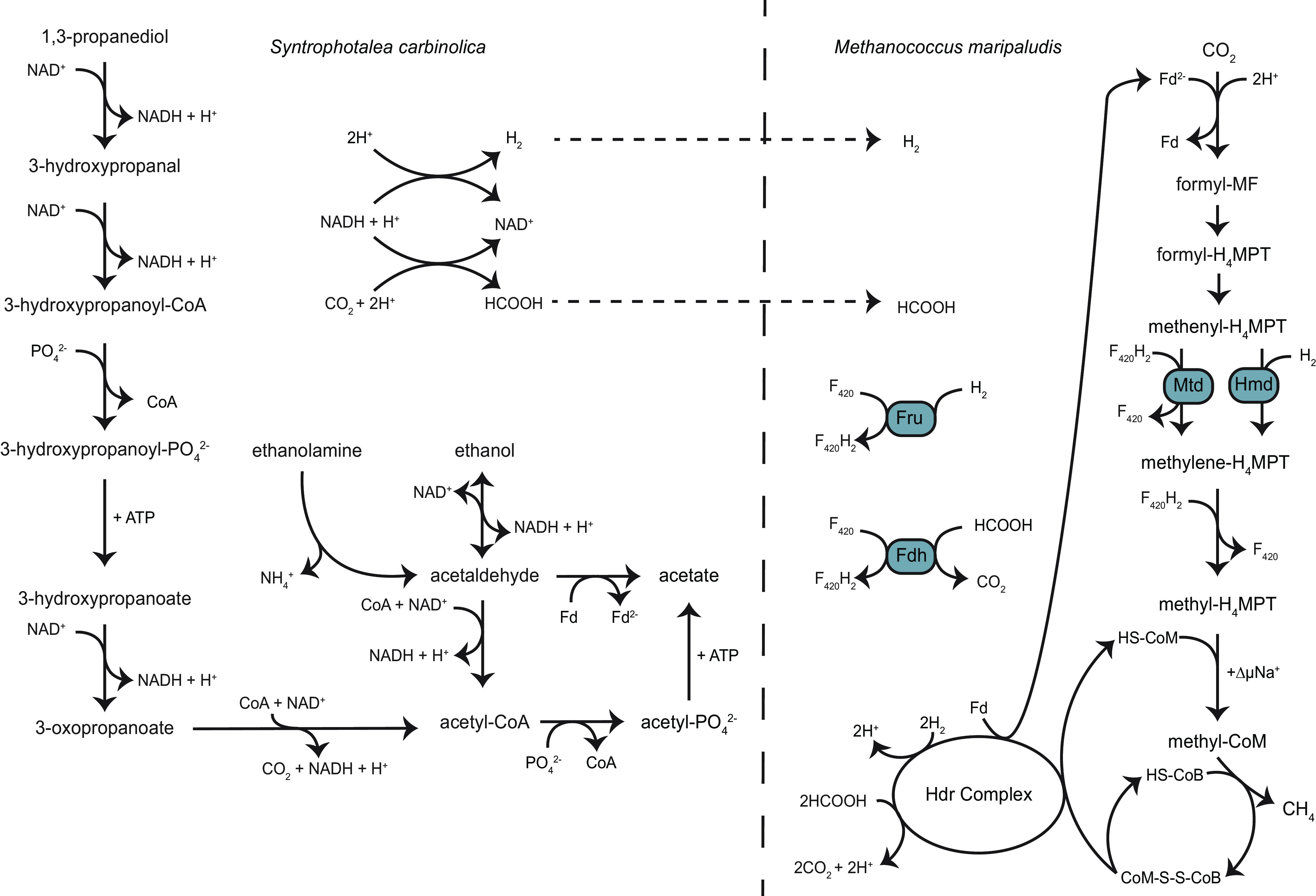

Syntrophotalea carbinolica Bd1, previously Pelobacter carbinolicus (14), is an obligate fermenter that uses ethanolamine, ethanol, and 1,3-propanediol as substrates through syntrophic interactions with a methanogenic partner such as M. maripaludis (Fig. 1). Oxidation of each substrate results in H2 (eqs. 3–5) and/or formate (eqs. 6–8) production, with different yields per mole of starting substrate. However, whether differing rates of H2/formate production influences community composition is unknown.

FIG 1.

Schematic overview of S. carbinolica and M. maripaludis syntrophic metabolism using either 1,3-propanediol, ethanolamine, or ethanol as the sole electron donor. Either H2 or formate can be produced by S. carbinolica and either substrate can serve as the electron donor for CO2 reduction by M. maripaludis. Fru, F420-reducing hydrogenase; Fdh, formate dehydrogenase; Mtd, F420-dependent methylene-H4MPT dehydrogenase; Hmd, H2-dependent methylene-H4MPT dehydrogenase.

H2 production from ethanolamine, ethanol, and 1,3-propanediol:

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Formate production from ethanolamine, ethanol, and 1,3-propanediol:

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

A robust suite of genetic tools and in-depth understanding of the genes/proteins for H2 and formate oxidation makes M. maripaludis an excellent model for assessing nutrient exchange during syntrophic growth (15–19). S. carbinolica was chosen as a syntrophic partner due to its similar growth kinetics, temperature, and salt optima to M. maripaludis (20). S. carbinolica is unable to catalyze direct interspecies electron transfer using conductive filaments and relies solely on the exchange of H2 or formate when grown with hydrogenotrophic methanogens (5, 21). Leveraging these features, we use a genetic approach to determine the relative importance of H2 and formate exchange during syntrophic growth of these organisms.

RESULTS

Growth on ethanolamine, ethanol, and 1,3-propanediol under syntrophic conditions.

We found that M. maripaludis and S. carbinolica can only grow through the oxidation of ethanol or 1,3-propanediol in coculture; neither organism can oxidize these substrates in axenic culture (Fig. S1). This is due to the inability of M. maripaludis to use ethanol and 1,3-propanediol directly and that fermentation of these substrates by S. carbinolica is thermodynamically unfavorable in axenic culture (22, 23). Interestingly, S. carbinolica can grow axenically using ethanolamine as the sole substrate (Fig. S1); we hypothesize that this is due to energy conservation by reduction of ferredoxin (Fd) during the oxidation of acetaldehyde to acetate coupled to the reduction of acetaldehyde to ethanol using NADH (Fig. 1) (24). An Rnf complex catalyzes electron transfer from reduced Fd to NAD+ to conserve energy (24). When M. maripaludis is present during growth on ethanolamine, S. carbinolica instead generates H2 and/or formate as substrates for methanogenesis as evidenced by growth of M. maripaludis under these conditions (Fig. 2).

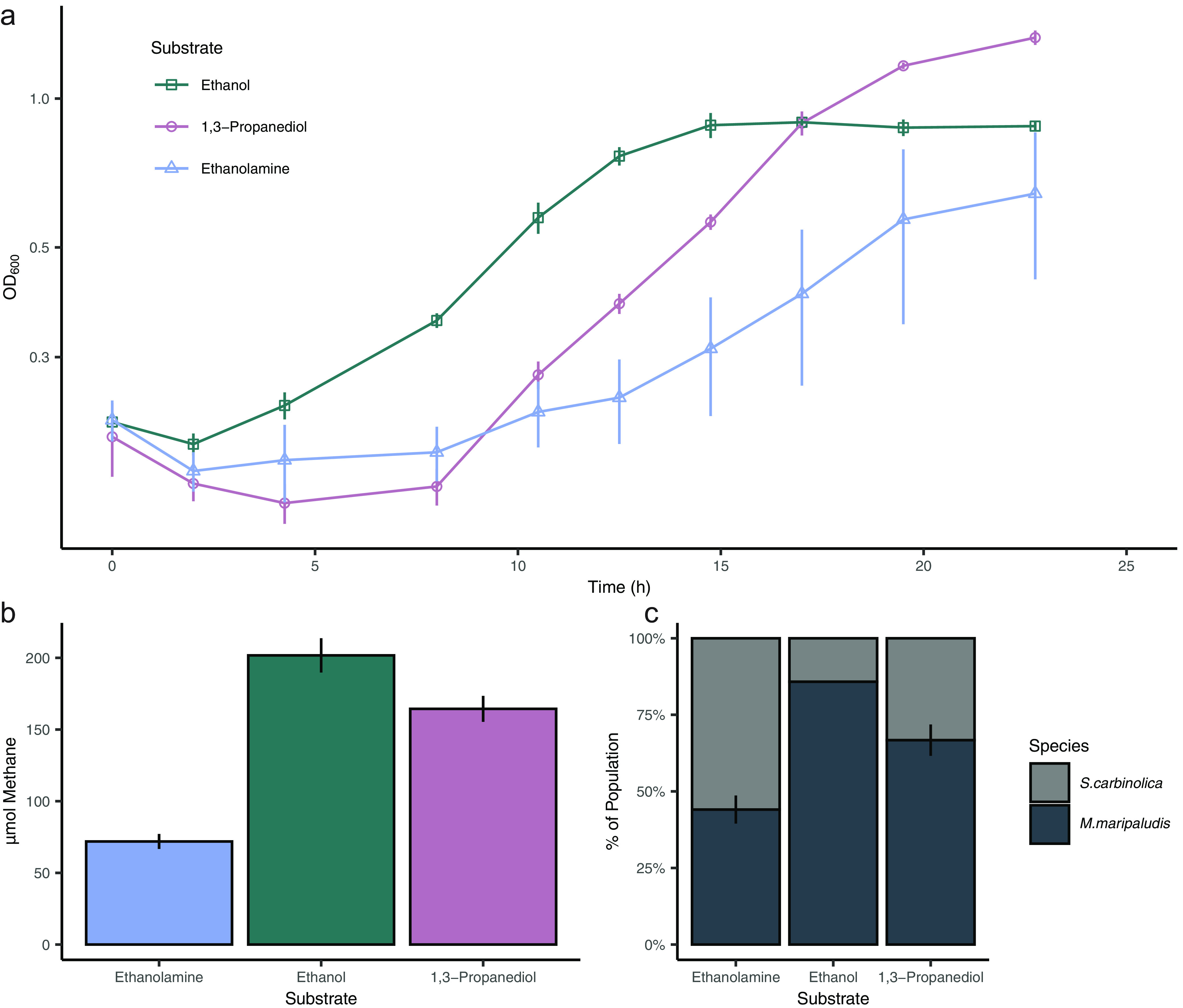

FIG 2.

Growth and methane production by S. carbinolica and M. maripaludis grown on ethanolamine, ethanol, and 1,3-propanediol. (a) Growth on each substrate. (b) CH4 produced on each substrate. Values are normalized to the optical density of the culture at the time of measurement to enable direct comparisons between substrates. The color palate from panel A was applied for each substrate in panel B. (c) Distribution of organisms during growth on each substrate as determined by direct cell counts. Data in all panels are averages and standard deviations for triplicate cultures. Data were collected from cells during the exponential phase of growth (OD600 range of 0.4 to 0.6).

During syntrophic growth, 1 mole of H2 or formate is produced from the oxidation of ethanolamine, 2 moles from ethanol oxidation, and 4 moles from 1,3-propanediol oxidation (Fig. 1 and eqs. 3–8). We hypothesized that these different production rates would alter the ratio of S. carbinolica cells to M. maripaludis cells during growth. To assess syntrophic growth on each substrate, relative activity of M. maripaludis was assessed by monitoring growth and quantifying methane accumulation and species abundance (Fig. 2). Methane production was reflective of the proportion of M. maripaludis observed in each condition. During growth with ethanolamine, 71.9 ± 5.2 μmol CH4 were produced with M. maripaludis accounting for 44.5 ± 4.6% percent of the population. With ethanol, 201.7 ± 12.0 μmol CH4 were produced with M. maripaludis accounting for 85.8 ± 0.4% of the population, and with 1,3 propanediol 164.3 ± 9.1 μmol CH4 were produced with M. maripaludis accounting for 66.7 ± 5.1% of the population. Even though 1,3-propanediol should produce the most H2 or formate per mole of substrate, it was when cocultures used ethanol that the highest CH4 concentrations were observed, and the largest proportion of the population was comprised of M. maripaludis. We hypothesize this is due to the fact 1,3-propanediol oxidation by S. carbinolica yields 2 moles of ATP (Fig. 1), while ethanolamine and ethanol oxidations yield a maximum of 1. As a result, S. carbinolica may have an energy yield advantage over M. maripaludis during the oxidation of 1,3-propanediol.

Transposon mutagenesis and sequencing (TnSeq) suggests interspecies formate exchange drives syntrophic growth.

S. carbinolica is capable of producing H2 or formate as fermentation products (5). Each of these substrates can act as electron donors for methanogenesis; however, it is unclear if one is preferred. We employed TnSeq to determine whether substrate preference exists. A population of M. maripaludis transposon insertion mutants (25) was grown syntrophically with S carbinolica on ethanol for approximately 30 generations with sampling and assessment of fitness for each mutant in the population every 5 to 10 generations (Fig. 3). Ethanol was chosen as the substrate for this experiment for several reasons, including (i) the first syntrophic interactions described in the literature were described in an ethanol oxidizing community (2), (ii) M. maripaludis comprises the largest proportion of the community on ethanol (Fig. 2c), and (iii) we generally observed the shortest lags in growth upon transition to syntrophic growth on ethanol (Fig. 2a), likely because ethanol is produced as an intermediate during axenic growth of S. carbinolica on acetoin (5). Several genes that were previously identified as essential for axenic growth of M. maripaludis (25) also had defects during syntrophic growth (Data set S1). This is unsurprising given that the medium composition in our experiments was nearly identical to the medium used in (25).

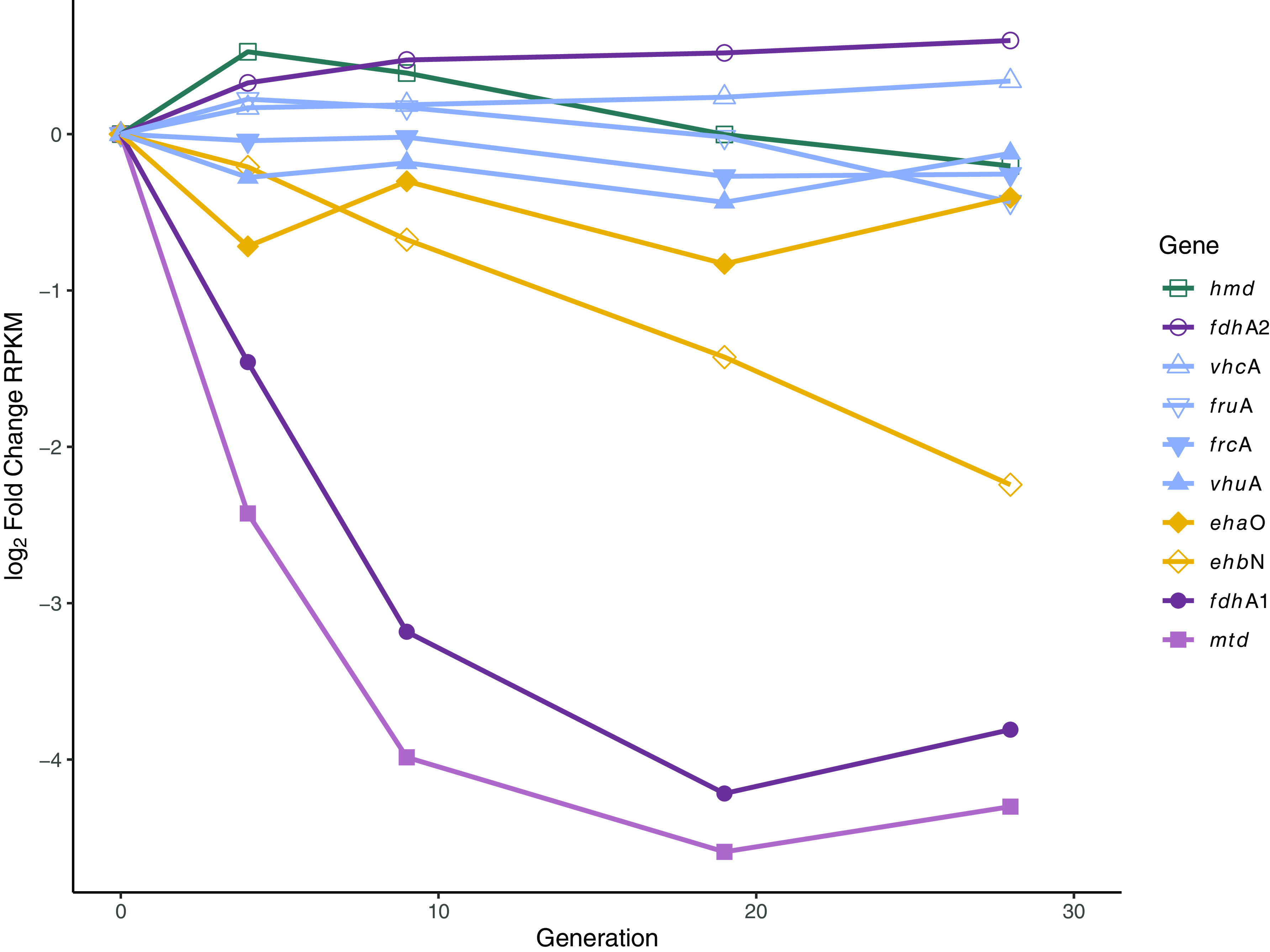

FIG 3.

Fitness of genes involved in electron transfer reactions in methanogenesis determined from sequencing a transposon insertion library (TnSeq) in ethanol oxidizing syntrophic conditions with S. carbinolica. Fitness of transposon mutants tracked by log2 fold change of RPKM over generations. Hmd, H2-dependent methylene-H4MPT dehydrogenase; Fdh, formate dehydrogenase; Vhc and Vhu, selenocysteine and cysteine containing F420-non-reducing hydrogenase; Fru and Frc, selenocysteine and cysteine containing F420-reducing hydrogenase; Eha and Ehb, membrane-bound, energy-converting hydrogenase; Mtd, F420-dependent methylene-H4MPT dehydrogenase.

To determine whether H2 or formate exchange drives syntrophic growth of S. carbinolica and M. maripaludis, we focused our analysis on genes that encode redox active proteins necessary for methanogenesis (Fig. 1). These are hydrogenases, formate dehydrogenases, and the F420-dependent methylene-tetrahydromethanopterin (H4MPT) dehydrogenase (Mtd). Either formate or H2 can reduce F420 for the Mtd-dependent reaction. Only insertions in the membrane-bound, energy-converting hydrogenase (ehb), formate dehydrogenase 1 (fdh1), and mtd were associated with a defect during syntrophic growth (Fig. 3). Insertions in fdhA1 and mtd resulted in a 10- to 16-fold decrease in mutant abundance within 10 generations while insertions in ehbN resulted in a more modest ~4-fold decrease in mutant abundance after 30-generations. Insertions in all other hydrogenases and formate dehydrogenases resulted in less than a 2-fold change in mutant abundance across 30 generations. Fdh1 is the primary isoform responsible for formate oxidation in M. maripaludis; the alternate isoform, Fdh2, is not essential for formate-dependent methanogenesis and its physiological role is not known (26–28). Because Fdh catalyzes the oxidation of formate to CO2 and the concomitant reduction of cofactor F420 to F420H2 and Mtd uses F420H2 as the electron donor for the reduction of methenyl-H4MPT, this suggests an importance for interspecies exchange of formate in these cultures.

Competitive analysis of mutants verifies the importance of formate-dependent methanogenesis.

To verify the importance of interspecies formate transfer during syntrophic growth, we generated an M. maripaludis strain that lacks both copies of fdh (ΔfdhA1B1 ΔfdhA2B2), hereafter referred to as Δfdh, that cannot use formate as an electron donor for growth (Fig. S2). We also used an M. maripaludis strain that lacks several cytoplasmic hydrogenases (ΔvhuAU ΔvhcA ΔfruA ΔfrcA), hereafter referred to as Δ4H2ase (19), that cannot use H2 as an electron donor for growth (Fig. S2). The Δfdh strain grows as well as wild type on H2 and the Δ4H2ase strain grows as well as wild type on formate. Additionally, an 8 bp DNA sequence encoding a unique molecular identifier (UMI) was introduced into each strain to track their abundance across growth conditions using sequencing.

To validate the use of UMIs, we first wanted to confirm that introduction of these did not impact growth. Each UMI was introduced into wild type M. maripaludis before mixing the resulting strains in equal ratios. The mixed culture was inoculated with S. carbinolica into medium with ethanol as a substrate and the relative abundance of each UMI was monitored over 20 generations. Both UMIs were maintained at the initial starting ratio (1:1) across the entire experiment (Fig. S3). Additionally, we tested whether the Δfdh and Δ4H2ase strains could compete against wildtype under syntrophic growth conditions with ethanol as the sole substrate for growth. Both strains decreased in relative abundance across 20 generations with the Δfdh strain exhibiting a more severe disadvantage (Fig. S4).

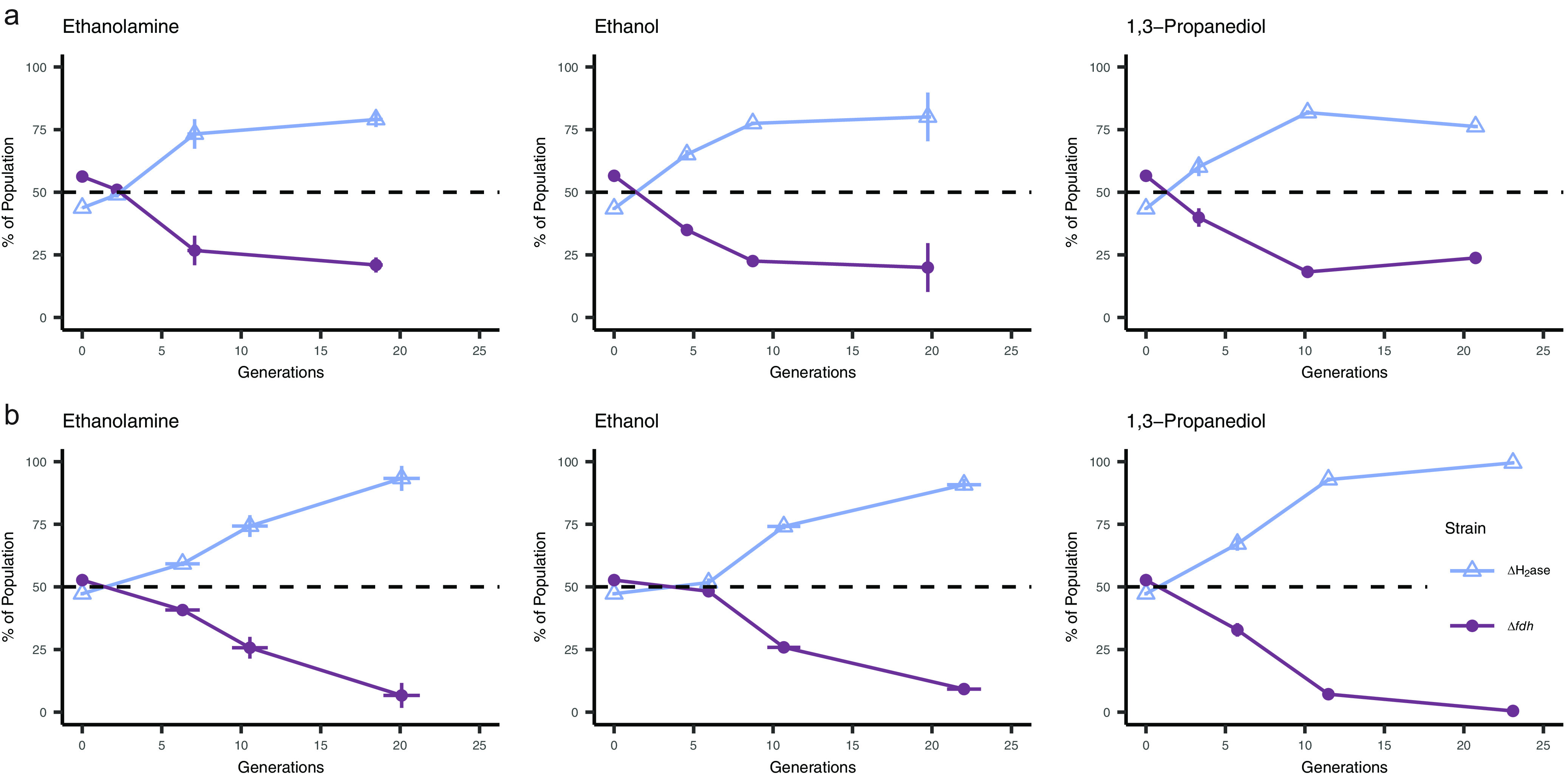

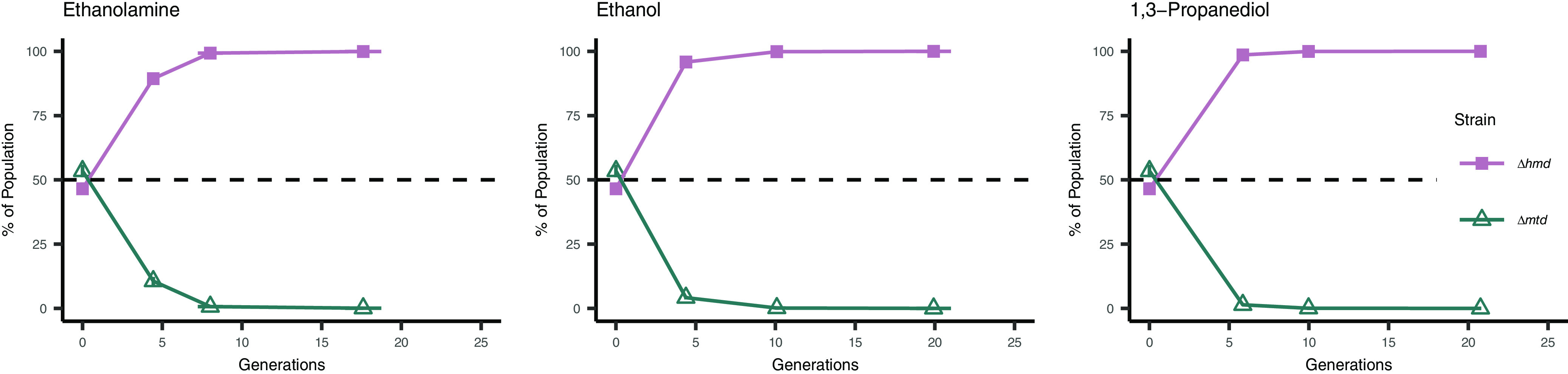

To more clearly assess whether H2 of formate exchange dominated during syntrophic growth, we competed the M. maripaludis Δ4H2ase and Δfdh strains across multiple substrates to determine whether differences in community composition (Fig. 2) have an impact on nutrient exchange. The M. maripaludis Δ4H2ase and Δfdh strains were mixed in an equal ratio and grown syntrophically with S. carbinolica using ethanolamine, ethanol, or 1,3-propanediol as substrates. Cultures were grown under both static and shaking conditions. Relative abundance of each strain was determined through sequencing of the UMI over 20 generations. For all 3 substrates, the Δ4H2ase strain increased in abundance relative to the Δfdh strain (Fig. 4), suggesting a competitive advantage for M. maripaludis using formate as an electron donor for methanogenesis. In static cultures, relative proportions of the strains stabilized after ~10 generations such that the Δ4H2ase strain represented ~75% of the total M. maripaludis population. In shaking cultures, the Δ4H2ase strain represented up to 99% of the total M. maripaludis population, suggesting that agitation drove more H2 into the gas phase and created conditions that further favored use of the soluble formate anion for methanogenesis.

FIG 4.

Competition between M. maripaludis Δ4H2ase (blue open triangle) and Δfdh (purple solid circle) strains in syntrophy with S. carbinolica across substrates in (a) stationary and (b) agitated cultures. Strain proportion determined through amplicon sequencing of UMIs. Data in all panels are averages and standard deviations for triplicate cultures.

The Mtd-dependent reduction of methenyl-H4MPT is preferred over the Hmd-dependent reaction.

To further validate the fitness differences observed during growth of the transposon mutant library on ethanol (Fig. 3), we introduced UMIs into M. maripaludis strains lacking hmd and mtd. As expected, when mixed with wildtype and grown with S. carbinolica using ethanol, the Δmtd strain decreased in relative abundance across 20 generations and the Δhmd strain was maintained in the population at the same frequency (Fig. 3 and Fig. S4). These data further suggest that formate exchange drives syntrophic growth as both Hmd and Mtd catalyze the reduction of methenyl-H4MPT to methylene-H4MPT (Fig. 1), but Hmd requires H2 as the electron donor for this reaction.

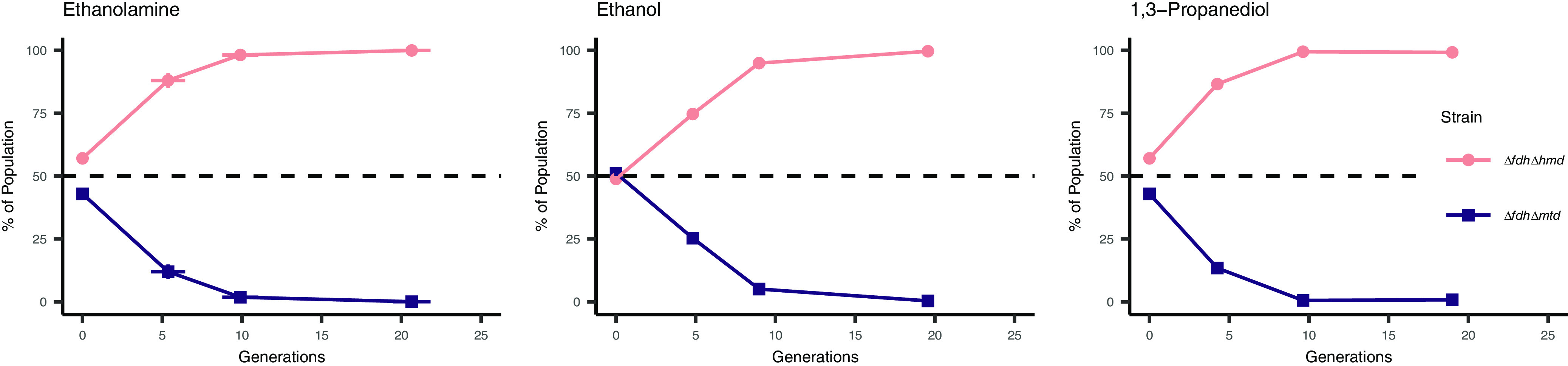

As further validation of the importance of Mtd to syntrophic growth, the Δhmd and Δmtd strains were directly competed in the presence of S. carbinolica in medium containing ethanolamine, ethanol, or 1,3-propanediol as sole carbon sources. On all 3 substrates, the Δhmd strain comprised over 99% of the M. maripaludis population within 10 generations (Fig. 5), suggesting that the Mtd-dependent reduction of methenyl-H4MPT is favored over the Hmd-dependent reaction.

FIG 5.

Competition between M. maripaludis Δmtd and Δhmd strains in stationary syntrophic conditions with S. carbinolica across substrates. Strain proportion determined through amplicon sequencing of UMIs. Data in all panels are averages and standard deviations for triplicate cultures.

F420H2-dependent reduction of methenyl-H4MPT is preferred, even when H2 transfer drives syntrophic growth.

The growth advantage of the Δhmd mutant over the Δmtd mutant may be due to an abundance of F420H2 from formate oxidation or due to a higher affinity of the Mtd-dependent pathway for substrates. In axenic culture, loss of mtd results in a growth defect when formate is the sole electron donor for methanogenesis (29). However, the Δmtd strain grows as well as wild type when H2 is the sole electron donor. To assess the roles of Hmd and Mtd under H2-dependent syntrophic growth conditions, we generated 2 mutant strains of M. maripaludis lacking either hmd or mtd in the Δfdh background. This effectively limits selective pressure from F420H2 abundance due to formate oxidation. For the reduction of methenyl-H4MPT, the ΔfdhΔmtd mutant can use H2 through direct oxidation by Hmd and the ΔfdhΔhmd mutant can use H2 throughout the combined activities of the F420-dependent hydrogenase (Fru) and Mtd (28, 29).

We introduced UMIs into the ΔfdhΔmtd and ΔfdhΔhmd strains, mixed in equal ratios, and inoculated with S. carbinolica into medium with ethanolamine, ethanol, or 1,3-propanediol as substrates. When forced to grow by interspecies H2 exchange, the ΔfdhΔhmd strain comprised over 99% of the M. maripaludis population within 10 generations (Fig. 6), verifying that Mtd-dependent methenyl-H4MPT reduction is favored.

FIG 6.

Competition between M. maripaludis ΔfdhΔhmd and ΔfdhΔmtd strains in stationary syntrophic conditions with S. carbinolica across substrates. Strain proportion determined through amplicon sequencing of UMIs. Data in all panels are averages and standard deviations for triplicate cultures.

DISCUSSION

The exchange of H2 or formate between methanogens and their syntrophic partners drives the remineralization of organic matter in anoxic environments. Prior studies designed to understand the dynamics of this nutrient exchange have focused on using transcriptomics or proteomics (5, 30, 31), small molecule inhibitors of hydrogenases or formate dehydrogenases (32), measurement of H2 or formate in cocultures (5), mutant strains of the bacterial partner organism (30, 33), or cocultures with multiple distinct methanogenic species capable of using exclusively H2 or H2 and formate in tandem (2). These studies have identified several cases where formate exchange likely drives syntrophic interactions. However, it must be noted that each approach has limitations.

Measurement of a metabolite is not necessarily evidence of its importance and syntrophic organisms can readily switch between H2 or formate production to overcome small molecule inhibitors or the loss of genes encoding hydrogenases or formate dehydrogenases. Additionally, transcriptomics and proteomics do not measure relative activities of enzymes, and use of different methanogenic species can be confounded due to differences in growth rates. To overcome some of these issues, we employed an assay to compete mutant strains of M. maripaludis against each other and measured their relative abundance to infer the importance of H2 and formate exchange for supporting syntrophic growth (Fig. 4 and 5). We have tracked the contribution of both metabolic intermediates to methanogenesis in a community where the production/consumption of each are viable modes of electron transfer for the species involved (eqs. 1–8). Under these conditions, we found that interspecies formate exchange results in a greater flux of electrons between species during syntrophic growth. This approach holds promise to assessing nutrient exchange for a variety of syntrophic organisms.

Previous analysis of formate dehydrogenase and hydrogenase expression patterns and enzymatic activity has suggested that metabolic intermediate exchange may vary depending on the substrate oxidized (32). Within the M. maripaludis and S. carbinolica model system, we found that formate-based metabolism had a fitness advantage in syntrophic growth regardless of substrate. We initially hypothesized that the selection for the formate utilizing strain would be amplified in the 1,3-propanediol oxidizing cultures relative to ethanol and ethanolamine oxidizing cultures as there are predicted 2- to 4-fold more H2 equivalents generated per 1,3-propanediol oxidized. However, all three substrates stabilized with the Δ4H2ase strain comprising approximately 75% of the methanogen population. Even when flux of intermediates is greater, the relative contributions of H2 or formate to growth of M. maripaludis remains stable. Selection favoring formate utilizing strains is increased across all substrates when cultures are agitated, likely due to an increase in transfer of H2 into the culture headspace.

The other metabolic reaction that was strongly favored during syntrophic growth was the F420H2-dependent reduction of methenyl-H4MPT by Mtd. During growth on formate, the reasons for this are clear, Fdh generates F420H2 through formate oxidation; however, during growth with H2, F420H2 can be generated by Fru. Despite both the Fru/Mtd reaction and the Hmd reaction using the same substrate, Mtd was still strongly favored. Fru has a higher affinity for H2 than Hmd with a Km of ~10 μM compared to ~200 μM (34, 35). Because S. carbinolica relies on M. maripaludis maintaining a low partial pressure of H2, maintaining H2 at a lower concentration is advantageous to the community. When H2 concentrations are ~10 μM, the ΔG of ethanol oxidation is estimated to be approximately −68 kJ mol−1 compared to −46 kJ mol−1 at H2 concentrations of ~200 μM. Regardless of whether formate or H2 exchange occurs, our data supports that the Mtd-dependent reduction of methenyl-H4MPT should be favored.

In addition to fdh and mtd, several other genes were identified as important for growth in our TnSeq experiment (Data set S2). Many of these genes appear to be involved in protein synthesis (e.g., ribosomal proteins) or other cell functions that were previously identified as essential for growth (25). Therefore, we focused our efforts on genes encoding proteins that carry out electron transfer reactions in methanogenesis. Mutants with an insertion in ehbN exhibited an ~4-fold decrease in abundance after 28 generations during syntrophic growth (Fig. 3). Ehb reduces ferredoxin that acts as the electron donor for several biosynthetic reactions (e.g., acetate and amino acid synthesis) (36). Prior studies found that M. maripaludis mutants defective for carbon assimilation showed a growth defect when grown under formate-oxidizing conditions, even when acetate was present in the growth medium (37). This suggests that, even on our acetate containing medium, cells that preferentially oxidize formate may require Ehb for anabolism. Thus, the importance of Ehb for anabolism during growth with formate could explain why ehbN mutants have a fitness defect in syntrophic conditions, where formate-based methanogenesis predominates.

Nutrient exchange between syntrophic partners is essential for methanogenesis in the environment. Here, we demonstrate that formate exchange between S. carbinolica and M. maripaludis is favored across several conditions and substrates. Combined with recent studies highlighting the importance of formate for growth and methanogenesis in several organisms (7, 9), this suggests that formate plays an underappreciated role in the metabolism of methanogenic archaea. Leveraging an expanding number of methanogenic archaea that can be genetically manipulated (38–41), the approaches described here hold promise for assessing nutrient exchange in a variety of syntrophic partnerships.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Growth conditions.

Strains were grown at 37°C in McCas medium or McCas-formate medium as previously described (26) in Balch tubes or in 100 mL serum vials, except (NH4)2S was used instead of Na2S following the method of (38). Serum vials were filled with 20 mL medium to keep proportion of headspace and medium consistent with that of Balch tubes. McCas medium used for S. carbinolica and syntrophic growth was prepared with an 80% N2-20% CO2 headspace. S. carbinolica was grown in McCas medium with 10 mM acetoin without agitation. M. maripaludis cultures grown with H2 as the electron donor were pressurized to 280 kPa with an 80% H2-20% CO2 gas mix. For growth with formate as the electron donor, cultures were pressurized to 207 kPa with an 80% N2-20% CO2 gas mix. All S. carbinolica and syntrophic cultures were pressurized to 138 kPa with an 80% N2-20% CO2 gas mix. For syntrophic growth, medium was supplemented with 50 mM substrate (ethanol, ethanolamine, or 1,3-propanediol). For M. maripaludis strain selection, media was supplemented with neomycin (1 mg mL−1) or 6-azauracil (0.25 mg mL−1) when appropriate. Escherichia coli was grown in lysogeny broth or on lysogeny broth 1% agar plates supplemented with ampicillin (50 μg mL−1) and incubated at 37°C.

S. carbinolica, M. maripaludis strains, and syntrophic cultures were grown to stationary phase prior to inoculation into growth analysis conditions. To remove residual electron donor, strains were pelleted and washed twice with McCas medium by pressurizing cultures to 280 kPa with an 80% N2-20% CO2 gas mix and centrifuging at 2,500 × g (Avanti J-15, Beckman Coulter). Cultures were inoculated from washed and OD600 normalized cultures grown with the respective medium to allow for normalization to occur. Growth was measured by optical density at 600 nm (OD600) using a spectrophotometer (Genesys 30, Thermo Scientific).

Cell counts and CH4 measurements.

To determine the relative proportion of M. maripaludis to S. carbinolica during growth on ethanolamine, ethanol, or 1,3-propanediol, cells were counted by microscopy. Co-cultures were grown overnight on each substrate before transfer to fresh medium (4% inoculum) and outgrown to an OD600 of ~0.4. At this point, 1.5 mL of culture was mixed with 0.15 mL of a 25% glutaraldehyde solution and incubated at room temperature for 20 min under anoxic conditions. The fixed culture material was pelleted by centrifugation (10,000 × g for 2 min) and resuspended in 50 μL of medium. The concentrated culture material was mounted on a microscope slide and imaged using an ECHO Revolve R4 hybrid microscope in the upright orientation. The microscope was equipped with a high-resolution condenser (numerical aperture 0.85, working distance 7 mm) and a 100x fluorite oil phase objective lens (numerical aperture 1.30, working distance 0.2 mm). Rod shaped cells were counted as S. carbinolica and coccoid cells were counted as M. maripaludis. Four fields of view were imaged for each replicate, and cultures were grown in triplicate for each substrate.

To measure CH4 accumulation, headspace from a second set of cultures was sampled and transferred to sealed 5 mL vials (1:10 vol/vol). Gas samples were collected using a Hamilton sample lock syringe. CH4 was measured on a GC-2014 gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector and an 80/100 porapak N column (6 ft x 1/8in x 2.1 mm SS). Carrier gas was run at a 25 mL min−1 flow rate. CH4 concentrations in these samples were calculated by comparison to samples with known concentrations of CH4 and normalized to the optical density of the culture.

Molecular techniques.

All primers, plasmids, and strains are available in Tables S1 and 2. All PCRs were performed using Phusion High-Fidelity DNA polymerase (New England Biolabs). For tracking relative abundance of M. maripaludis strains, each strain was labeled with a replicative plasmid containing an 8 bp UMI. To generate the UMI containing plasmids, complementary oligonucleotides containing 5′-GAGGTCTCTNNNNNNNNCGT flanked by ~20 bp homology arms were annealed to generate double stranded DNA. The annealed oligonucletide and pLW40neo digested with NsiI were assembled using NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly (New England Biolabs). To generate an fdhA1B1 deletion construct (pCRUptNeoΔfdhA1B1), 500 bp flanking the genes were PCR amplified using primers listed in Table S1. PCR products were restriction digested with XbaI, AscI, and NotI then purified using PureLink PCR purification kit (Invitrogen) and combined with XbaI and NotI-digested pCRUptNeo. The plasmid was assembled using T4 DNA ligase (Invitrogen). Assembled plasmids were electroporated into E. coli DH5α. Plasmids were purified using a PureLink quick plasmid miniprep kit (Invitrogen). Replicative and integrative plasmids were transformed into M. maripaludis strains using the polyethylene glycol method (42). pCRUptNeoΔfdhA1B1 was transferred into a ΔfdhA2B2 strain (26) and subjected to neomycin-based and 6-azauracil-based selection/counterselection as described previously (26) to produce the Δfdh strain. Following transformation with replicative plasmids, M. maripaludis strains were plated on McCas or McCas-formate medium supplemented with neomycin and grown for 3 days before screening for positive transformants using PCR. Strains were maintained in media supplemented with neomycin until inoculation into syntrophic conditions. All mutants were verified by Sanger sequencing of the appropriate locus.

TnSeq.

A previously generated M. maripaludis strain S2 transposon library with ~30,000 individual mutants was used (25). The library was washed and inoculated with S. carbinolica (0.5 mL each) in McCas medium in serum vials with ethanol as the electron donor. The population was incubated undisturbed for ~5 generations before sampling and transfer. At each time point, 1 mL of culture material was collected, and DNA was extracted from each sample using the DNeasy blood and tissue kit (Qiagen). Library preparation and sequencing was performed by the University of Minnesota Genomics Center (UMGC). UMGC used the NEBNext library preparation kit following manufacturer’s instructions. Libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NextSeq 2000 platform mid-output 2 × 150 bp paired end sequencing.

Scripts used for analysis are available at https://github.com/LeslieDay/SyntrophyCode. Cutadapt (v.1.18) (43) was used to trim adapters and sequence matching the Tn5 inverted repeat. Additionally, reads were trimmed from the 3′ end until a base with a quality score of 30 (Q30) or greater was reached. Reads with less than 30 bases remaining were discarded. The remaining reads were mapped to M. maripaludis S2 genome using Bowtie 2 (v.2.3.4.1) (44) with default parameters. For reads that mapped to a single location, insertion site was determined. Reads mapping to insertions occurring after the first 5% of the gene and before the last 20% of the gene were counted, consistent with parameters used by Sarmiento et al., 2013 (25). Subsequent analysis was performed using R (v.4.1.0) (45). Counts were normalized by reads per kilobase gene per million mapped reads (RPKM). Raw, normalized, and log2 data for non-essential coding genes are listed in Data set S2. Non-coding genes, previously experimentally determined essential genes, and genes determined by past transposon analysis to be essential (25) are available in Data set S1.

Growth of M. maripaludis strains under competitive conditions.

All competition experiments were performed in serum vials containing McCas medium and 50 mM substrate (ethanol, ethanolamine, or 1,3-propanediol). M. maripaludis strains containing a UMI were grown, washed, and mixed in equal proportions based on the OD600 of each strain before inoculation into serum bottles with S. carbinolica. Static cultures were undisturbed between transfers and agitated cultures were incubated on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm. After subinoculation, remaining culture was transferred to a Balch tube for OD600 measurement and samples were collected for sequencing. Template DNA was prepared by pelleting and lysing M. maripaludis through resuspension in sterile ddH2O. The resuspension was centrifuged to remove cell lysate and the supernatant used as a template for PCR. A 400 bp fragment covering the 8 bp UMI was amplified using one of seven indexed primers (Tables S1 and 2). Up to seven amplicon reactions, all with different indexes, were pooled and purified using PureLink PCR cleanup kit (Invitrogen). Illumina DNA libraries were prepared and sequenced using the NextSeq 2000 platform at 200Mbp depth by the Microbial Genome Sequencing Center (MiGS).

The code and analysis parameters for analyzing amplicon sequencing of the UMI is available at https://github.com/LeslieDay/SyntrophyCode. Sample sequences were demultiplexed based on index. Sequences were counted if both the primer index and plasmid UMI were present and had a quality score greater than or equal to 10 (Q10). For each indexed sample, strain proportion was calculated by dividing the strain associated UMI count by the total UMI counts multiplied by 100. For both Tn5 library and syntrophy competition experiments, generations were estimated by dividing the OD600 at the time of sampling by the OD600 of the inoculating culture multiplied by the dilution factor.

Data availability.

All datasets and code used in this study are freely available in the supplemental materials or through referenced links. Microbial strains will be made available on request.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank William Whitman for providing the transposon mutant library used in this study and Jon Badalamenti for helpful discussions. This work was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences under grant number DE-SC0019148.

Footnotes

Supplemental material is available online only.

Contributor Information

Kyle C. Costa, Email: kcosta@umn.edu.

Arpita Bose, Washington University in St. Louis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Saunois M, Stavert AR, Poulter B, Bousquet P, Canadell JG, Jackson RB, Raymond PA, Dlugokencky EJ, Houweling S, Patra PK, Ciais P, Arora VK, Bastviken D, Bergamaschi P, Blake DR, Brailsford G, Bruhwiler L, Carlson KM, Carrol M, Castaldi S, Chandra N, Crevoisier C, Crill PM, Covey K, Curry CL, Etiope G, Frankenberg C, Gedney N, Hegglin MI, Höglund-Isaksson L, Hugelius G, Ishizawa M, Ito A, Janssens-Maenhout G, Jensen KM, Joos F, Kleinen T, Krummel PB, Langenfelds RL, Laruelle GG, Liu L, Machida T, Maksyutov S, McDonald KC, McNorton J, Miller PA, Melton JR, Morino I, Müller J, Murguia-Flores F, et al. 2020. The global methane budget 2000–2017. Earth Syst Sci Data 12:1561–1623. 10.5194/essd-12-1561-2020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bryant MP, Wolin EA, Wolin MJ, Wolfe RS. 1967. Methanobacillus omelianskii, a symbiotic association of two species of bacteria. Arch Mikrobiol 59:20–31. 10.1007/BF00406313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thauer RK. 1998. Biochemistry of methanogenesis: a tribute to Marjory Stephenson:1998 Marjory Stephenson Prize Lecture. Microbiology 144:2377–2406. 10.1099/00221287-144-9-2377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schink B, Montag D, Keller A, Müller N. 2017. Hydrogen or formate: Alternative key players in methanogenic degradation. Environ Microbiol Rep 9:189–202. 10.1111/1758-2229.12524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt A, Frensch M, Schleheck D, Schink B, Müller N. 2014. Degradation of acetaldehyde and its precursors by Pelobacter carbinolicus and P acetylenicus. PLoS One 9:e115902. 10.1371/journal.pone.0115902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dworkin M, Falkow S, Rosenberg E, Schleifer K-H, Stackebrandt E. 2006. The Prokaryotes. Springer; New York, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdul Halim MF, Day LA, Costa KC. 2021. Formate-dependent heterodisulfide reduction in a Methanomicrobiales Archaeon. Appl Environ Microbiol 87:e02698-20. 10.1128/AEM.02698-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun H, Yang Z, Shi G, Arhin SG, Papadakis VG, Goula MA, Zhou L, Zhang Y, Liu G, Wang W. 2021. Methane production from acetate, formate and H2/CO2 under high ammonia level: modified ADM1 simulation and microbial characterization. Sci Total Environ 783:147581. 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.147581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watanabe T, Pfeil-Gardiner O, Kahnt J, Koch J, Shima S, Murphy BJ. 2021. Three-megadalton complex of methanogenic electron-bifurcating and CO2-fixing enzymes. Science 373:1151–1156. 10.1126/science.abg5550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milton RD, Ruth JC, Deutzmann JS, Spormann AM. 2018. Methanococcus maripaludis employs three functional heterodisulfide reductase complexes for flavin-based electron bifurcation using hydrogen and formate. Biochemistry 57:4848–4857. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b00662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thiele JH, Zeikus JG. 1988. Control of interspecies electron flow during anaerobic digestion: significance of formate transfer versus hydrogen transfer during syntrophic methanogenesis in flocs. Appl Environ Microbiol 54:20–29. 10.1128/aem.54.1.20-29.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boone DR, Johnson RL, Liu Y. 1989. Diffusion of the interspecies electron carriers H2 and formate in methanogenic ecosystems and its implications in the measurement of Km for H2 or formate uptake. Appl Environ Microbiol 55:1735–1741. 10.1128/aem.55.7.1735-1741.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schink B, Stams AJM. 2013. Syntrophism among prokaryotes, p 471–493. In Rosenberg E., DeLong EF., Lory S., Stackebrandt E., Thompson F., (ed), The Prokaryotes Prokaryotic Communities and Ecophysiology. Springer, New York City, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Waite DW, Chuvochina M, Pelikan C, Parks DH, Yilmaz P, Wagner M, Loy A, Naganuma T, Nakai R, Whitman WB, Hahn MW, Kuever J, Hugenholtz P. 2020. Proposal to reclassify the proteobacterial classes Deltaproteobacteria and Oligoflexia, and the phylum Thermodesulfobacteria into four phyla reflecting major functional capabilities. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol 70:5972–6016. 10.1099/ijsem.0.004213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarmiento FB, Leigh JA, Whitman WB. 2011. Genetic systems for hydrogenotrophic methanogens, p 43–73. In Rosenzweig AC, Ragsdale SW, (ed), Methods in Enzymology. Academic Press, Cambridge MA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendrickson EL, Haydock AK, Moore BC, Whitman WB, Leigh JA. 2007. Functionally distinct genes regulated by hydrogen limitation and growth rate in methanogenic Archaea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:8930–8934. 10.1073/pnas.0701157104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xia Q, Wang T, Hendrickson EL, Lie TJ, Hackett M, Leigh JA. 2009. Quantitative proteomics of nutrient limitation in the hydrogenotrophic methanogen Methanococcus maripaludis. BMC Microbiol 9:149. 10.1186/1471-2180-9-149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Costa KC, Lie TJ, Jacobs MA, Leigh JA. 2013. H2-independent growth of the hydrogenotrophic methanogen Methanococcus maripaludis. mBio 4:e00062-13. 10.1128/mBio.00062-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lie TJ, Costa KC, Lupa B, Korpole S, Whitman WB, Leigh JA. 2012. Essential anaplerotic role for the energy-converting hydrogenase Eha in hydrogenotrophic methanogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 109:15473–15478. 10.1073/pnas.1208779109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sehink B. 1984. Fermentation of 2,3-butanediol by Pelobacter carbinolicus sp. nov., and evidence for propionate formation from C2 compounds. Arch Microbiol 137:33–41. 10.1007/BF00425804. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rotaru A-E, Shrestha PM, Liu F, Ueki T, Nevin K, Summers ZM, Lovley DR. 2012. Interspecies electron transfer via hydrogen and formate rather than direct electrical connections in cocultures of Pelobacter carbinolicus and Geobacter sulfurreducens. Appl Environ Microbiol 78:7645–7651. 10.1128/AEM.01946-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jones WJ, Paynter MJB, Gupta R. 1983. Characterization of Methanococcus maripaludis sp. nov., a new methanogen isolated from salt marsh sediment. Arch Microbiol 135:91–97. 10.1007/BF00408015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sieber JR, McInerney MJ, Gunsalus RP. 2012. Genomic insights into syntrophy: the paradigm for anaerobic metabolic cooperation. Annu Rev Microbiol 66:429–452. 10.1146/annurev-micro-090110-102844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aklujkar M, Haveman SA, DiDonato R, Chertkov O, Han CS, Land ML, Brown P, Lovley DR. 2012. The genome of Pelobacter carbinolicus reveals surprising metabolic capabilities and physiological features. BMC Genomics 13:1–24. 10.1186/1471-2164-13-690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sarmiento F, Mrazek J, Whitman WB. 2013. Genome-scale analysis of gene function in the hydrogenotrophic methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110:4726–4731. 10.1073/pnas.1220225110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Costa KC, Wong PM, Wang T, Lie TJ, Dodsworth JA, Swanson I, Burn JA, Hackett M, Leigh JA. 2010. Protein complexing in a methanogen suggests electron bifurcation and electron delivery from formate to heterodisulfide reductase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:11050–11055. 10.1073/pnas.1003653107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wood GE, Haydock AK, Leigh JA. 2003. Function and regulation of the formate dehydrogenase genes of the methanogenic Archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol 185:2548–2554. 10.1128/JB.185.8.2548-2554.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lupa B, Hendrickson E, Leigh J, Whitman W. 2008. Formate-dependent H2 production by the mesophilic methanogen Methanococcus maripaludis. Appl Environ Microbiol 74:6584–6590. 10.1128/AEM.01455-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hendrickson EL, Leigh JA. 2008. Roles of coenzyme F420-reducing hydrogenases and hydrogen- and F420-dependent methylenetetrahydromethanopterin dehydrogenases in reduction of F420 and production of hydrogen during methanogenesis. J Bacteriol 190:4818–4821. 10.1128/JB.00255-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meyer B, Kuehl J, Deutschbauer AM, Price MN, Arkin AP, Stahl DA. 2013. Variation among Desulfovibrio species in electron transfer systems used for syntrophic growth. J Bacteriol 195:990–1004. 10.1128/JB.01959-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walker CB, Redding-Johanson AM, Baidoo EE, Rajeev L, He Z, Hendrickson EL, Joachimiak MP, Stolyar S, Arkin AP, Leigh JA, Zhou J, Keasling JD, Mukhopadhyay A, Stahl DA. 2012. Functional responses of methanogenic archaea to syntrophic growth. ISME J 6:2045–2055. 10.1038/ismej.2012.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sieber JR, Le HM, McInerney MJ. 2014. The importance of hydrogen and formate transfer for syntrophic fatty, aromatic and alicyclic metabolism. Environ Microbiol 16:177–188. 10.1111/1462-2920.12269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Meyer B, Kuehl JV, Deutschbauer AM, Arkin AP, Stahl DA. 2013. Flexibility of syntrophic enzyme systems in Desulfovibrio species ensures their adaptation capability to environmental changes. J Bacteriol 195:4900–4914. 10.1128/JB.00504-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thauer RK, Klein AR, Hartmann GC. 1996. Reactions with molecular hydrogen in microorganisms: evidence for a purely organic hydrogenation catalyst. Chem Rev 96:3031–3042. 10.1021/cr9500601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shima S, Thauer RK. 2007. A third type of hydrogenase catalyzing H2 activation. Chem Rec 7:37–46. 10.1002/tcr.20111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Major TA, Liu Y, Whitman WB. 2010. Characterization of energy-conserving hydrogenase B in Methanococcus maripaludis. J Bacteriol 192:4022–4030. 10.1128/JB.01446-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sattler C, Wolf S, Fersch J, Goetz S, Rother M. 2013. Random mutagenesis identifies factors involved in formate-dependent growth of the methanogenic archaeon Methanococcus maripaludis. Mol Genet Genomics 288:413–424. 10.1007/s00438-013-0756-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fonseca DR, Halim MFA, Holten MP, Costa KC. 2020. Type IV-like pili facilitate transformation in naturally competent Archaea. J Bacteriol 202:e00355-20. 10.1128/JB.00355-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rother M, Metcalf WW. 2005. Genetic technologies for Archaea. Curr Opin Microbiol 8:745–751. 10.1016/j.mib.2005.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Susanti D, Frazier MC, Mukhopadhyay B. 2019. A genetic system for Methanocaldococcus jannaschii: an evolutionary deeply rooted hyperthermophilic methanarchaeon. Front Microbiol 10:1–15. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fink C, Beblawy S, Enkerlin AM, Mühling L, Angenent LT, Molitor B. 2021. A shuttle-vector system allows heterologous gene expression in the thermophilic methanogen Methanothermobacter thermautotrophicus ΔH. mBio 12:e02766-21. 10.1128/mBio.02766-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tumbula DL, Makula RA, Whitman WB. 1994. Transformation of Methanococcus maripaludis and identification of a Pst I-like restriction system. FEMS Microbiology Lett 121:309–314. 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1994.tb07118.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Martin M. 2011. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet j 17:10–12. 10.14806/ej.17.1.200. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R Core Team. 2021. R: A language and environment for statistical computing R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Fig. S1 to S4 and Tables S1 and S2. Download aem.01159-22-s0001.pdf, PDF file, 0.2 MB (228KB, pdf)

Data Set S1. Download aem.01159-22-s0002.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.1 MB (143.1KB, xlsx)

Data Set S2. Download aem.01159-22-s0003.xlsx, XLSX file, 0.3 MB (309KB, xlsx)

Data Availability Statement

All datasets and code used in this study are freely available in the supplemental materials or through referenced links. Microbial strains will be made available on request.