ABSTRACT

Vaccinating health-care workers against influenza during the COVID-19 pandemic can effectively prevent and control influenza and reduce COVID-19 strain on health systems. This study was conducted to explore influenza vaccination coverage and determinants among health-care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020/2021 influenza season in Ningxia. This cross-sectional survey included demographic characteristics of health-care workers, influenza vaccination status, reasons for not getting vaccinated, and whether influenza vaccination was recommended for others. We found that influenza vaccine rate of health-care workers was 39.6%. A binary logistic regression analysis showed that health-care workers’ vaccination coverage was higher when the individuals were aware of the effect of the influenza vaccine (OR = 0.624, 95% CI: 0.486–0.802). Health-care workers who from internal medicine (OR = 1.494, 95% CI: 1.146–1.948), pediatrics (OR = 2.091, 95% CI: 1.476–2.962), and surgery departments (OR = 1.373, 95% CI: 1.014–1.859) had a lower coverage than those who worked in vaccination and infectious disease departments. The main reasons that some stated for not getting vaccinated were that they felt it was unnecessary (52.22%). Health-care workers who were vaccinated against influenza were more likely to recommend influenza vaccination to their patients than health-care workers who had not been vaccinated. The incidence of influenza among health-care workers was higher than that of the general population in Ningxia. Under the policy of voluntary and self-pay influenza vaccination in Ningxia, the coverage rate of influenza vaccine among health-care workers was far below the vaccination requirements of influenza vaccine in influenza season even during the COVID-19 epidemic.

KEYWORDS: Health-care workers, influenza vaccine, vaccination coverage

Introduction

Influenza is an acute respiratory infectious disease caused by the influenza virus, which endangers human health. It was also the first infectious disease to be monitored globally by the WHO.1 Influenza can cause a yearly seasonal epidemic, resulting in significant global morbidity, severe illness, and death and in a serious disease burden.

Although influenza viruses are prone to mutation, the influenza vaccine is still one of the most effective measures against influenza.2 Data have shown that influenza and SARS-CoV-2 viruses did spread simultaneously during the COVID-19 pandemic. Influenza vaccination can help prevent or reduce the severity of influenza diseases, reducing outpatient, inpatient, and intensive care unit patients. This can then effectively alleviate the burden on the health-care system caused by COVID-19.3–6 A study showed that health-care workers, who usually worked at medical and health organization, had a higher risk of getting influenza because they were more likely to be exposed to the virus than the general population.1 Health-care workers who have not been vaccinated were 3.4 times more likely to get influenza than healthy adults. Meanwhile, health-care workers who were infected with the influenza virus may cause disruption to medical services, thereby affecting medical treatment of other patients.7 In addition, health-care workers infected with influenza may cause in-hospital infections of influenza in patients in contact, increasing the risk of serious illness, complications, and death.8 Therefore, it is more important for health-care workers to be vaccinated against influenza, especially for COVID-19 prevention and control.

As a result, the WHO and many countries have put more emphasis on influenza vaccination and issued a series of policies. SAGE of the WHO issued Seasonal Influenza Vaccination Recommendations during the COVID-19 Pandemic in September 2020, and health-care workers and the elderly were identified as the highest priority groups. In the latest “Influenza vaccine inoculation and technology of China (2021–2022),” the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention indicated that the pandemic was not over. Combined with the new epidemic situation, recommendations should be given to the protection of medical personnel, including clinical care workers, public health workers, and health quarantine workers. In this unique period, the whole world should focus on the importance of influenza vaccination for health-care workers, but the real state of influenza vaccination remains unclear.

The Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region is a relatively underdeveloped region in northwestern China, in which the influenza vaccination policy for health-care workers is voluntary and chargeable. Moreover, the influenza vaccination status in health-care workers in this region is currently unknown. Therefore, we conducted a retrospective cross-sectional study to investigate the influenza vaccination rate and influencing factors among health-care workers, either working in community health centers or hospitals during the epidemic period of COVID-19 in 2020/2021 influenza season.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional survey was conducted through Wenjuanxing (wjx.cn). Questionnaires were sent to 22 counties and districts in Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region. The participants included health-care workers from secondary and higher hospitals and community health centers. Sample size was calculated using a cluster sampling formula, and the estimated sample size was 1,152. At least 52 health-care workers were surveyed in each county.

Data source

Because of COVID-19 prevention and control measures, we sent QR codes to eligible people to allow them to complete questionnaires online. The questionnaire was voluntary, and each participant could only answer once. The questionnaire included general demographic information, employment information, influenza vaccination status, reasons for not getting vaccinated, and whether influenza vaccination was recommended for others. To improve the reliability of the questionnaire, specific vaccination data were required if the respondents stated that they had been vaccinated against influenza. Reasons for not getting vaccinated are mutually exclusive.

Influenza incidence was used to evaluate the occurrence of influenza, which refers to the proportion of people with influenza. Influenza season refers to the span of time in which the influenza virus is at its most contagious. This period generally occurs during the colder months of the year. In China, this refers to the period from November to March each year. Influenza vaccine coverage was used to evaluate vaccination rate, which refers to the proportion of people vaccinated against influenza during the influenza season.

Data on influenza cases were obtained from China information system for disease control and prevention, which was a network direct reporting system in China. Data on influenza vaccinations were obtained from the China information management system for immunization programming. Population data were obtained from the Ningxia Statistical Yearbook.

Statistical analysis

The original survey data were imported into Microsoft Excel from the Wenjuanxing, and the data were analyzed by SPSS 25.0. A Chi-square test was used to compare all categorical variables, while continual variables were compared using a t-test for two independent samples. A binary logistic regression model was used to analyze the influencing factors of influenza vaccination among health-care workers. The dependent variable was whether an individual was vaccinated from August 2020 to March 2021. Independent variables were sex, education, occupation, field of work, professional title, monthly average income, knowledge of the effect of influenza vaccine, age, and the length of service.

Relative risks were estimated by calculating odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05, and all statistical tests were two sided.

Results

General demographic characteristics

A total of 2,192 valid questionnaires were collected, covering all 22 counties and districts in Ningxia. Among the 2192 respondents, 868 participants were vaccinated against influenza in 2020/2021 influenza season, and the vaccination rate of health-care workers against influenza was 39.6%. The mean age of respondents was 35.6 ± 9.146 y (range 18–59 y), of whom 1752 (79.93%) were women. The study included 953 (43.50%) physicians and 1,239 (56.50%) nurses. All health-care workers’ characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Influenza vaccination coverage of health-care workers in 2020/2021 influenza season.

| Characteristics | Category | n (%) or mean ± SD | vaccinated n (%) or mean ± SD | p (chi-square test or t test) | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of subjects | - | 2192 | 868 (39.60) | - | - |

| Sex | Male | 440 (20.07) | 143 (32.50) | 0.001 | Ref. |

| Female | 1752 (79.93) | 725 (41.38) | 0.888 (0.681–1.157) | ||

| Education | Junior high school and below | 6 (0.27) | 1 (16.67) | 0.000 | Ref. |

| High school | 110 (5.02) | 59 (53.64) | 0.161 (0.017–1.495) | ||

| Junior college | 809 (36.91) | 363 (44.87) | 0.203 (0.022–1.844) | ||

| University degree | 1223 (55.79) | 436 (35.65) | 0.243 (0.027–2.219) | ||

| Master degree and above | 44 (2.01) | 9 (20.45) | 0.443 (0.042–4.643) | ||

| Occupation | Physicians | 953 (43.5) | 306 (32.11) | 0.000 | Ref. |

| Nurses | 1239 (56.5) | 562 (45.36) | 0.833 (0.654–1.060) | ||

| Field of work | Vaccination | 460 (21.0) | 237 (51.52) | 0.000 | Ref. |

| Infectious disease Department | 259 (11.8) | 131 (50.58) | 0.915 (0.663–1.261) | ||

| Internal medicine | 695 (31.7) | 253 (36.40) | 1.494 (1.146–1.948) | ||

| Pediatrics | 420 (19.2) | 104 (24.76) | 2.091 (1.476–2.962) | ||

| Surgery | 358 (16.3) | 143 (39.94) | 1.373 (1.014–1.859) | ||

| Professional title | Senior | 72 (3.28) | 27 (37.5) | 0.143 | Ref. |

| Vice-senior | 250 (11.41) | 86 (34.4) | 1.000 (0.552–1.815) | ||

| Middle | 444 (20.26) | 176 (39.64) | 0.698 (0.375–1.300) | ||

| Primary | 914 (41.7) | 355 (38.84) | 0.727 (0.372–1.419) | ||

| No title | 512 (23.36) | 224 (43.75) | 0.725 (0.356–1.477) | ||

| Monthly average income | ≤3000 | 645 (29.43) | 295 (45.74) | 0.000 | Ref. |

| 3001–5000 | 1116 (50.91) | 424 (37.99) | 1.162 (0.914–1.477) | ||

| 5001–8000 | 328 (14.96) | 102 (31.1) | 1.287 (0.886–1.869) | ||

| 8001–1000 | 69 (3.15) | 32 (46.38) | 0.693 (0.384–1.250) | ||

| ≥10,001 | 34 (1.55) | 15 (44.12) | 0.601 (0.269–1.344) | ||

| Know the effect of influenza vaccine | Yes | 1815 (82.80) | 760 (41.87) | 0.000 | 0.624 (0.486–0.802) |

| No | 377 (17.20) | 108 (28.63) | Ref. | ||

| Age, y | - | 35.60 ± 9.146 | 35.90 ± 9.105 | 0.209 | 0.985 (0.955–1.015) |

| Length of service, y | - | 11.12 ± 9.420 | 12.58 ± 9.474 | 0.069 | 0.996 (0.968–1.026) |

Determinants of influenza vaccination among health-care workers

Univariate analysis identified that there were no significant differences in age, length of service, and professional titles between influenza vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups (all p > 0.05). Statistical differences were found between two groups in sex, education, occupation, field of work, professional title, monthly average income, and knowledge of the effect of the influenza vaccine (p < 0.05). Details are shown in Table 1.

Binary logistic regression was used to analyze the factors affecting the coverage of influenza vaccination. The data showed that health-care workers’ vaccination coverage was higher when individuals were aware of the effect of the influenza vaccine (OR = 0.624, 95% CI: 0.486–0.802). Health-care workers who worked in internal medicine (OR = 1.494, 95% CI: 1.146–1.948), pediatrics (OR = 2.091, 95% CI: 1.476–2.962), and surgery (OR = 1.373, 95% CI: 1.014–1.859) had a lower coverage than those who worked in vaccination and infectious disease department (Table 1).

Reasons for having not being vaccinated

In this work, 900 health-care workers gave a clear reason for not being vaccinated, including that they thought it was unnecessary (52.22%), they did not have enough time (15.11%), there was a lack of vaccines (11.44%), they were worried about acute adverse reactions (5.44%), a lack of knowledge about vaccine (4.67%), vaccine cost (4.44%), and doubts about its safety (4.11%) and efficacy (2.56%). Details are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Reasons for not getting influenza vaccination among health-care workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in 2020/2021 influenza season.

| Reasons for not being vaccinateda | No. | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Unnecessary | 470 | 52.22 |

| Lack of time | 136 | 15.11 |

| Lack of vaccines | 103 | 11.44 |

| Worried about acute adverse reactions | 49 | 5.44 |

| Lack of knowledge about vaccine | 42 | 4.67 |

| High price | 40 | 4.44 |

| Doubts about its safety | 37 | 4.11 |

| Doubts about its efficacy | 23 | 2.56 |

aThese reasons are mutually exclusive.

Recommendation rate for influenza vaccines

The rate at which physicians recommended their patients to receive influenza vaccine was also analyzed. We found that 25.78% of health-care workers always recommended it, while 35.86% of health-care workers recommended it only sometimes. Furthermore, 25.82% recommended the vaccine occasionally, and 12.54% never recommended it. The proportion of health-care workers recommended the vaccine who had been vaccinated against influenza was higher than that of health-care workers who had not been vaccinated (90.44% vs. 85.5%, χ2 = 33.68, p < 0.001). Details are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Vaccination recommendations of vaccines in influenza vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups.

| Vaccination recommendationsa | N (%) | IV (n, %) | INV (n, %) | p (chi-square test) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Always recommended | 565 (25.78) | 277 (31.91) | 288 (21.75) | <0.001 |

| Sometimes recommended | 786 (35.86) | 299 (34.45) | 487 (36.78) | |

| Recommended occasionally | 566 (25.82) | 209 (24.08) | 357 (26.96) | |

| Never recommended | 275 (12.55) | 83 (9.56) | 192 (14.5) |

aThese choices are mutually exclusive.

Influenza incidence and vaccination rate of the population

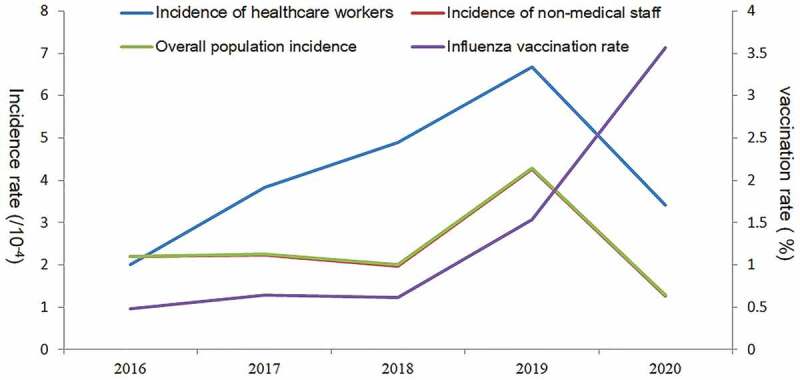

Influenza surveillance data in the past 5 y showed that from 2016 to 2019, the incidence of influenza in Ningxia increased year by year and dropped sharply in 2020. The incidence of whole population and non-medical personnel dropped to the lowest incidence level in recent 5 y. Moreover, the incidence of health-care workers was higher than the average level of the whole population and the non-medical staff except for in 2016. From 2016 to 2020, the influenza vaccination rate of the whole population in Ningxia increased year by year, with the highest levels being observed in 2020 in the past 5 y (3.5%). However, this was still lower than the influenza vaccination rate of health-care workers (3.57% vs. 39.6%, χ2 = 8245.005, p < 0.001). Details are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Influenza incidence and influenza vaccination rate in Ningxia from 2016 to 2020.

Incidence of health-care workers: the proportion of health-care workers with influenza of Ningxia. Incidence of non-medical staff: the proportion of non-medical staff with influenza of Ningxia. Overall population incidence: the proportion of influenza in the whole population of Ningxia. Influenza vaccination rate: the proportion of the whole population vaccinated against influenza of Ningxia.

Discussion

The present cross-sectional study in a representative population sample found that the influenza vaccine coverage of health-care workers in Ningxia was 39.6% during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was far below the average coverage in China during the 2019/2020 influenza season (67%).9 During the 2017/2018 influenza season in the USA, one study10 showed that the influenza vaccination coverage among health-care workers reached 78.4%, which was over twice the rate of the present study even before the COVID-19 pandemic.

We assumed that during the COVID-19 pandemic, many people, including health-care workers, might have been concerned about the devastating consequences caused by the extra burden of seasonal influenza,11 which led to a substantial increase in the vaccination rate of influenza vaccine. The influenza vaccination rate in Ningxia had increased year by year in the previous 5 y, reaching the highest level (3.57%) in 2020, which agreed with our hypothesis. Although the influenza vaccination rate of health-care workers in 2020 was obviously higher than that of the whole population, because of their occupation, as a high-risk group of influenza incidence and key personnel for epidemic prevention and control in the COVID-19 epidemic, this vaccination rate was far below the expected coverage. Interestingly, under the pressure of prevention and control in COVID-19 pandemic, the influenza vaccination rate of health-care workers has still not increased to a sufficient level. This phenomenon may be related to the Chinese government’s measures to deal with COVID-19 outbreak, such as free vaccination of COVID-19 vaccine for all Chinese personnel. One study12 suggested that different COVID-19 vaccines are highly effective against the original strain and variants of concern. Therefore, a widespread COVID-19 vaccination campaign has rendered influenza vaccination less urgent. Moreover, interventions such as social distancing and mask wearing are the key measures to control the spread of COVID-19 epidemic.13,14 Given the common transmission route between COVID-19 and influenza, the same protective behavior also greatly limits influenza transmission.13,15,16 In the 2020/2021 flu season, the incidence of influenza in Ningxia had dropped to the lowest level in the past 5 y. Consistent with our research results, studies have shown that there is a significant drop in influenza cases for both the 2020–2021 influenza season in the Northern Hemisphere and the 2020 influenza season in the Southern Hemisphere.14,16,17

In addition to the impact of COVID-19, we also investigated and analyzed other potential reasons that may affect the influenza vaccination rate of health-care workers in Ningxia. First, the mandatory influenza vaccination policy has been confirmed as an effective intervention to achieve high short-term and sustainable vaccination rates in health-care workers.18,19 In the United States, the vaccination rate rose from 47.6% to 94.8% after the influenza vaccination coverage among health-care workers was demanded as a requirement for employment. Similarly, it was shown that the vaccine coverage increased when vaccination was required or encouraged by the workplaces in China.9 Conversely, because influenza vaccination mainly relies on recommendations and voluntary vaccination in health-care workers20 in European countries, the voluntary influenza vaccination coverage rarely exceeds 60–70%.21–23 Secondly, free vaccinations can increase vaccine coverage. It was also showed that the cost of influenza vaccination was a common obstacle to obtaining the vaccination in places where vaccination was not covered or subsidized by insurance.24 One study indicated that influenza vaccine coverage increased significantly from 7.2% to 30.5% after vaccinations became free for health-care workers in Xining City, China.25 Therefore, the voluntary and self-pay influenza vaccination policy in Ningxia is a disadvantage for health-care workers to receive influenza vaccination.

Thirdly, vaccination coverage was closely related to vaccine awareness among health-care workers. A study by Surendranath26 revealed that poor vaccine awareness was a challenge and barrier among health-care workers in many countries. Likewise, in this study, the binary logistic regression analysis showed that health-care workers who understood the effectiveness of influenza vaccine and whose expertise was in vaccination and infectious disease were more likely to get vaccinated than others. Therefore, professional knowledge of disease prevention and control and a strong awareness of self-prevention by vaccine may account for this. Moreover, health-care workers from infectious disease departments may know that they are more exposed to influenza viruses. Furthermore, consistent with most studies,27,28 compared with the non-vaccinated group, health-care workers who had been vaccinated against influenza vaccine were more likely to recommend the vaccine to their patients. Some studies29,30 have shown that in the face of emerging vaccine hesitancy, health-care workers are the most trusted advisor and influencer of vaccination decisions. If strongly recommended by them, public vaccination acceptance may increase, which is conducive to increase the population vaccination rate. In contrast, the biggest reason for remaining unvaccinated in health-care workers in this study was that they believed the influenza vaccination was unnecessary (52.22%), which indicated that unvaccinated health-care workers did not perceive themselves as a ‘high-risk’ population and did not recognize the significance. The lower vaccination rate and awareness resulted in higher morbidity among health-care workers than non-medical staff in 2016–2020. For this reason, many previous studies31–35 have shown that the effective educational interventions were useful in modifying vaccination behavior and improving vaccination rates among health-care workers. Last but not least, improving accessibility to vaccination services can significantly improve the vaccination rate in health-care workers.36,37 Health-care workers engaged in vaccination had a geographical accessibility, they were more convenient to get vaccinated than others, resulting in higher vaccination coverage. We also found that 15.11% of health-care workers did not receive vaccinations because of a simple lack of time. Therefore, accessibility played an important role in the vaccination of health-care workers.

In view of the above factors affecting influenza vaccination for health-care workers, mandatory and free vaccine policies may be effective measures to increase influenza vaccine coverage in Ningxia. Furthermore, education and improved vaccine accessibility among health-care workers cannot be ignored. Increased vaccine awareness in health-care workers may further encourage them to recommend vaccination and effectively improve the public vaccination opinion to achieve higher vaccination coverage in high-risk groups.

Limitations

This study was not without its limitations. First, the questionnaire was distributed to all hospitals and community health service centers in Ningxia; every health-care worker can fill in the questionnaire until the number of tasks in their region was completed. Therefore, the questionnaire-filling rate among different departments was unbalanced. Second, the vaccination situation in the present study was self-reported by responders, instead of checking the actual vaccination records by investigators, so it may have information bias. Third, the data could only be included when the questionnaire was completed by respondents, so the response rate cannot be calculated. Despite these limitations, this study, for the first time, investigated influenza vaccination status and influencing factors among health-care workers in Ningxia during the 2020/2021 influenza season under the impact of COVID-19 epidemic and made a unique contribution to the prevention and control of influenza.

Conclusion

The incidence of influenza among health-care workers was higher than that of the general population in Ningxia. Furthermore, the influenza vaccination rate among health-care workers was only 39.6%, which was far below the requirements in influenza season during the COVID-19 epidemic. Under a voluntary and self-pay vaccination policy, a lack of awareness and poor geographical accessibility were major reasons for the poor vaccination rate among health-care workers. Therefore, we must take effective measures to increase influenza vaccine coverage. Ultimately, the target of high vaccination coverage among high-risk groups will be achieved.

Acknowledgments

All authors acknowledge and thank their respective universities and affiliations. The authors specially thank Professor Wenjun Yang of Hainan Medical College for her advice in the writing process.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Key Technology Research and Development Program of Ningxia Hui Autonomous Region (No.2020BEG01001).

Author contributions

Xiaojuan Shi, Ying Zhang, and Luping Zhou prepared the questionnaire and coordinated the data collection. Xiaojuan Shi performed statistical analyses. Xiaojuan Shi, Ying Zhang, and Luping Zhou drafted the initial manuscript. Liwei Zhou and Hui Qiao reviewed and revised the final manuscript and critically reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Availability of data materials

The datasets used and analyzed in this study are available from corresponding authors on a reasonable request.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This questionnaire was reviewed and approved by the Ethical Review Committee of Ningxia Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Respondents participated in the survey after providing informed consent.

References

- 1.Kuster SP, Shah PS, Coleman BL, Lam P-P, Tong A, Wormsbecker A, McGeer A.. Incidence of influenza in healthy adults and healthcare workers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2011;6(10):1. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0026239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dini G, Toletone A, Sticchi L, Orsi A, Bragazzi NL, Durando P. Influenza vaccination in healthcare workers: a comprehensive critical appraisal of the literature. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2018;14(3):772–7. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2017.1348442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carman WF, Elder AG, Wallace LA, McAulay K, Walker A, Murray GD, Stott DJ. Effects of influenza vaccination of health-care workers on mortality of elderly people in long-term care: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet (London, England). 2000;355(9198):93–97. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)05190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayward AC, Harling R, Wetten S, Johnson AM, Munro S, Smedley J, Murad S, Watson JM. Effectiveness of an influenza vaccine programme for care home staff to prevent death, morbidity, and health service use among residents: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333(7581):1241–1246. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39010.581354.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lemaitre M, Meret T, Rothan-Tondeur M, Belmin J, Lejonc J-L, Luquel L, Piette F, Salom M, Verny M, Vetel J-M, et al. Effect of influenza vaccination of nursing home staff on mortality of residents: a cluster-randomized trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(9):1580–1586. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saxén H, Virtanen M. Randomized, placebo-controlled double blind study on the efficacy of influenza immunization on absenteeism of health care workers. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1999;18(9):779–783. doi: 10.1097/00006454-199909000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pereira M, Williams S, Restrick L, Cullinan P, Hopkinson NS. Healthcare worker influenza vaccination and sickness absence – an ecological study. Clin Med (London, England). 2017;17(6):484–489. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.17-6-484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Haviari S, Bénet T, Saadatian-Elahi M, André P, Loulergue P, Vanhems P. Vaccination of healthcare workers: a review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2015;11(11):2522–2537. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2015.1082014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yi H, Yang Y, Zhang L, Zhang M, Wang Q, Zhang T, Zhang Y, Qin Y, Peng Z, Leng Z. Improved influenza vaccination coverage among health-care workers: evidence from a web-based survey in China, 2019/2020 season. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2021;17(7):2185–2189. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1859317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Fink RV, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Williams WW, Graitcer SB, Fiebelkorn AP, Lu P-J. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel—United States, 2017–18 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(38):1050–1054. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6738a2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zipfel CM, Colizza V, Bansal S. The missing season: the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on influenza. Vaccine. 2021;39(28):3645–3648. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2021.05.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiolet T, Kherabi Y, MacDonald CJ, Ghosn J, Peiffer-Smadja N. Comparing COVID-19 vaccines for their characteristics, efficacy and effectiveness against SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern: a narrative review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2022;28(2):202–221. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haug N, Geyrhofer L, Londei A, Dervic E, Desvars-Larrive A, Loreto V, Pinior B, Thurner S, Klimek P. Ranking the effectiveness of worldwide COVID-19 government interventions. Nat Hum Behav. 2020;4(12):1303–1312. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-01009-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Di Domenico L, Pullano G, Sabbatini CE, Boëlle PY, Colizza V. Impact of lockdown on COVID-19 epidemic in Île-de-France and possible exit strategies. BMC Med. 2020;18(1):240–252. doi: 10.1186/s12916-020-01698-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cowling BJ, Ali ST, Ng TWY, Tsang TK, Li JCM, Fong MW, Liao Q, Kwan MY, Lee SL, Chiu SS, et al. Impact assessment of non-pharmaceutical interventions against coronavirus disease 2019 and influenza in Hong Kong: an observational study. The Lancet Public Health. 2020;5(5):e279–e288. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30090-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soo RJJ, Chiew CJ, Ma S, Pung R, Lee V. Decreased influenza incidence under COVID-19 control measures, Singapore. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(8):1933–1935. doi: 10.3201/eid2608.201229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, Brammer L, Sullivan S, Pineda RF, Cohen C, Fry AM. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1305–1309. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maltezou HC, Ioannidou E, De Schrijver K, Francois G, De Schryver A. Influenza vaccination programs for healthcare personnel: organizational issues and beyond. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(21):11122–11130. doi: 10.3390/ijerph182111122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talbot TR, Babcock H, Caplan AL, Cotton D, Maragakis LL, Poland GA, Septimus EJ, Tapper ML, Weber DJ. Revised SHEA position paper: influenza vaccination of healthcare personnel. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(10):987–995. doi: 10.1086/656558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maltezou HC, Botelho-Nevers E, Brantsæter AB, Carlsson R-M, Heininger U, Hübschen JM, Josefsdottir KS, Kassianos G, Kyncl J, Ledda C, et al. Vaccination of healthcare personnel in Europe: update to current policies. Vaccine. 2019;37(52):7576–7584. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jorgensen P, Mereckiene J, Cotter S, Johansen K, Tsolova S, Brown C. How close are countries of the WHO European region to achieving the goal of vaccinating 75% of key risk groups against influenza? Results from national surveys on seasonal influenza vaccination programmes, 2008/2009 to 2014/2015. Vaccine. 2018;36(4):442–452. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maltezou HC, Poland GA. Immunization of health-care providers: necessity and public health policies. Healthcare (Basel). 2016;4(3):47–55. doi: 10.3390/healthcare4030047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherian T, Morales KF, Mantel C, Lambach P, Al Awaidy S, Bresee JS, Chunsuttiwat S, Coulibaly D, Feng L, Hale R. Factors and considerations for establishing and improving seasonal influenza vaccination of health workers: report from a WHO meeting, January 16–17, Berlin, Germany. Vaccine. 2019;37(43):6255–6261. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.07.079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gorska-Ciebiada M, Saryusz-Wolska M, Ciebiada M, Loba J. Pneumococcal and seasonal influenza vaccination among elderly patients with diabetes. Postepy Higieny I Medycyny Doswiadczalnej (Online). 2015;69:1182–1189. doi: 10.5604/17322693.1176772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xu L, Zhao J, Peng Z, Ding X, Li Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Zheng J, Cao H, Ma B. An exploratory study of influenza vaccination coverage in healthcare workers in a Western Chinese city, 2018–2019: improving target population coverage based on policy interventions. Vaccines (Basel). 2020;8(1):92–100. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Surendranath M, Wankhedkar R, Lele J, Cintra O, Kolhapure S, Agrawal A, Dewda P. A modern perspective on vaccinating healthcare service providers in India: a narrative review. Infect Dis Ther. 2022;11(1):81–99. doi: 10.1007/s40121-021-00558-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q, Yue N, Zheng M, Wang D, Duan C, Yu X, Zhang X, Bao C, Jin H. Influenza vaccination coverage of population and the factors influencing influenza vaccination in mainland China: a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2018;36(48):7262–7269. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang JS, Zhang LJ, Feng LZ, Zhao JH, Ma YY, Xu LL. Influenza vaccination and its influencing factors among clinical staff of the hospitals in 2016-2017 season, Xining, Qinghai province, China. Zhonghua Liu Xing Bing Xue Za Zhi = Zhonghua Liuxingbingxue Zazhi. 2018;39(8):1066–1070. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.issn.0254-6450.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paterson P, Meurice F, Stanberry LR, Glismann S, Rosenthal SL, Larson HJ. Vaccine hesitancy and healthcare providers. Vaccine. 2016;34(52):6700–6706. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiley KE, Massey PD, Cooper SC, Wood NJ, Ho J, Quinn HE, Leask J. Uptake of influenza vaccine by pregnant women: a cross-sectional survey. Med J Aust. 2013;198(7):373–375. doi: 10.5694/mja12.11849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Schmidt S, Saulle R, Di Thiene D, Boccia A, La Torre G. Do the quality of the trials and the year of publication affect the efficacy of intervention to improve seasonal influenza vaccination among healthcare workers?: results of a systematic review. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(2):349–361. doi: 10.4161/hv.22736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bryant KA, Stover B, Cain L, Levine GL, Siegel J, Jarvis WR. Improving influenza immunization rates among healthcare workers caring for high-risk pediatric patients. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25(11):912–917. doi: 10.1086/502319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hollmeyer H, Hayden F, Mounts A, Buchholz U. Review: interventions to increase influenza vaccination among healthcare workers in hospitals. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2013;7(4):604–621. doi: 10.1111/irv.12002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Macdonald L, Cairns G, Angus K, de Andrade M. Promotional communications for influenza vaccination: a systematic review. J Health Commun. 2013;18(12):1523–1549. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2013.840697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Whitaker JA, Poland CM, Beckman TJ, Bundrick JB, Chaudhry R, Grill DE, Halvorsen AJ, Huber JM, Kasten MJ, Mauck KF. Immunization education for internal medicine residents: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Vaccine. 2018;36(14):1823–1829. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2018.02.082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Black CL, Yue X, Ball SW, Donahue SMA, Izrael D, de Perio MA, Laney AS, Lindley MC, Graitcer SB, Lu P-J. Influenza vaccination coverage among health care personnel – United States, 2013-14 influenza season. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(37):805–811. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Music T. Protecting patients, protecting healthcare workers: a review of the role of influenza vaccination. Int Nurs Rev. 2012;59(2):161–167. doi: 10.1111/j.1466-7657.2011.00961.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]