ABSTRACT

Scientists have emerged with innovative research on non-human primates showing that the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine increases neutralizing antibody levels against all variants. The current cross-sectional survey was designed to evaluate the knowledge, perception, and acceptance of the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine among the patients visiting the various dental clinics in Aseer region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. A total of 609 dental patients were selected from various dental clinics by a simple random probability sampling method. The questionnaire was designed in multiple languages and categorized as demographic information, knowledge, perception, and acceptance of participants to a booster dose. An anonymous, self-administered, closed-ended online, and paper-based questionnaire was used to assess the above parameters. In the current survey, the majority of the participants were Saudis (80.8%) with an age mean of 37.7 ± 8.7 years. About 68.6% (418 out of 609) of participants had poor knowledge about the booster dose. Significant differences in the levels of knowledge were found in relation to gender, area of residency, education, nationality, and occupation. The distribution of level of perception of booster dose differs significantly among participants of different marital statuses and nationalities. Hesitation to booster was reported more in the rural than in the urban population. Despite a low level of knowledge, a higher level of good perception and acceptance of booster doses were reported among the studied population.

KEYWORDS: Acceptance, booster dose, COVID-19, knowledge and awareness, perception

Introduction

COVID-19 disease has been declared a pandemic by WHO.1 It has spread rapidly causing massive fatalities worldwide, and no definitive curative treatment is known. Therefore, an immense, enthusiastic, international effort commenced to develop a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine to prevent the people from getting seriously ill and hospitalized. There were more than 100 prospective vaccines currently in different development stages,2 and several candidate vaccines were already in clinical trials.3 There are emerging evidences from eminent researchers in nonhuman primates that the booster dose of the COVID-19 vaccine increases production of neutralizing antibody titer against all variants of SARS-CoV-2.4,5 The situation was deteriorating worldwide, so requisite elaborative long-term studies could not be carried out, as they were time-consuming. So, WHO also gave emergency approval for the use of the vaccines. The vaccines were being considered to have the role of sheet anchor in this pandemic.

On the other hand, the discrepancy between the health policy guidelines from the states and the information being propagated from some prominent media personalities and political leaders in the US and the world over made it difficult for the health community to deliver a unified protocol needed to curb the highly contagious pandemic.6 Moreover, beliefs in conspiracy theories were circulating within social and traditional media.7–9 Conspiracy beliefs act as deterrents to take definitive action in the current pandemic because they are difficult to invalidate.10,11 Also, belief in any one of them is likely to be associated with belief in others, suggesting that some persons are more susceptible to such beliefs, regardless of their content.12 Some conspiracy beliefs have been associated with unreasonable fears of vaccination and unwillingness to vaccinate.13,14 This finding could be problematic because the surest means of controlling the pandemic was by vaccinating a high proportion of those susceptible to the Coronavirus disease.15 If conspiracy beliefs are associated with mistaken fears about the nature or effects of vaccination, their circulation could devitalize the country’s ability to control COVID-19.16

Besides, various factors influenced the desire for vaccination. It depends on the individual beliefs, psychological, physical, and financial factors.17,18 Some get vaccinated to prevent getting infected with the disease, whereas those who are medically compromised get vaccinated to avoid complications. Some get vaccinated to enjoy the freedom from restrictions imposed, while others get vaccinated to ease travel restrictions. Vaccine hesitancy is also one of the significant concerns that impair the effort to control the pandemic. Studies have been carried out evaluating the factors responsible for vaccine hesitancy in different segments of the population worldwide. In China, vaccine scandals and a series of reports about the serious side-effects of vaccination have increased vaccination hesitancy and distrust in the country’s immunization program.19 In a study, investigators evaluated the COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. They have recorded concerns about the dearth of long-term safety studies, adverse effects, possible congenital effects, skipping certain testing phases for rapid development, as well as concerns regarding the politicization of the matter for short-term personal political gains.20 Besides, there were undesirable side effects reported in certain individuals after the COVID-19 vaccination such as immune thrombocytopenia,21 and even anaphylaxis.22

Vaccines protect against infections by stimulating the immune system to mount an antibody response without actually causing infections. Widge et al. found higher antibody levels in COVID-19 vaccinated individuals (17 weeks after the first vaccination) as compared to individuals recovering from COVID-19 infection with a median of 34 days since diagnosis (range 23 to 54).23,24 However, with the passage of time, the antibody levels that are developed in response to the vaccines, decline, and COVID-19 vaccines are no exception.25 In a recently conducted study, Mizrahi et al., also found that protection against infection and disease gradually reduces with time.26 So, a booster dose is required to augment the immune response. A review by Shekhar et al. concluded that third or subsequent doses of COVID-19 vaccines can potentially boost the neutralizing antibody titers against SARS-CoV-2 and its variants.27

Booster dose vaccination has been initiated in KSA recently. So, with this background, we have designed a study to find out the knowledge, perception, and acceptance of the booster dose of COVID-19 vaccine among the patients visiting the various dental clinics in the Aseer region, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Materials and methods

The current cross-sectional study was carried out among dental patients visiting government and private dental clinics in the Aseer region of KSA from 1 September 2021 to 30 November 2021. The patients were selected by a simple random probability sampling method. The questionnaire was designed in the English, Arabic, Hindi, and Urdu language and was categorized into four segments: 1) demographics and general characteristics of the participants; 2) knowledge and awareness of the participants about booster dose; 3) perception of the participants about booster dose; and 4) participants’ acceptance for a booster dose.

The present survey design was introduced before the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the College of Dentistry, King Khalid University, Saudi Arabia, to acquire ethical clearance (IRB/KKUCOD/ETH/2020-21/020). The present study was carried out both online and physically in full accordance with the regulations established by the Declaration of Helsinki. The assessment of knowledge, perception, and acceptance of booster dose was done utilizing an anonymous, self-administered, closed-ended online and paper-based questionnaire. The questionnaire was distributed to the Saudi/non-Saudi population residing in both rural/urban regions and working in the government/private sector. Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants before filling out the survey form. The confidentiality of data was well preserved throughout the study by keeping it anonymous and asking the participants to select honest answers and options.

A pilot survey was conducted on 30 randomly selected patients from private and government clinics before initiating the actual data collection; however, these pilot samples were excluded from the final sample size. The prime objective of the pilot survey was to guarantee the validity and reliability of the questionnaire. The face and content validity of the questionnaire was assessed by specialists in the field of research. Face validity was evaluated through the review and comments offered by a panel of experts related to readability, clarity of wording, layout, and feasibility of the questionnaire. Content validity was evaluated by the content validity index, which is the mean content validity ratio of all questions in a questionnaire. The content validity index for our test was 0.82. The questionnaire was modified according to the participant’s suggestions and comments, to make it more comprehensive and understandable.

Knowledge and acceptance score were computed by offering a “1” score for each positive/correct response and a ”0” score for each negative/wrong response. The final scores were presented in the form of a percentage by adding all the points of the participants followed by calculating the percentage. The final knowledge and awareness scores were divided into three classes depending on percentage: poor knowledge (0–40%), fair knowledge (41 < 70%), and good knowledge (70% and above).28 The participant’s perception responses were assessed using 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 to 5 (1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree).

After complete data collection, the collected data was cleaned, coded, and entered into Microsoft Excel. The data on categorical variables are shown as n (% of participants – prevalence) and the data on continuous variables is presented as mean and standard deviation (SD). The intergroup statistical comparison of the distribution of categorical variables was tested using Pearson’s Chi-square test. In the entire study, P-values less than 0.05 were considered to be statistically significant. The entire data was statistically analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 22.0, IBM Corporation, USA) for MS Windows.

Results

Of 609 participants in the study, a higher proportion of participants were females (52.4%) and were aged between 20 and 39 years (60.9%) followed by 40–59 years (30.7%). The age (mean ± SD) of the whole group of participants was 37.7 ± 8.7 years and the minimum-maximum age range was 16–72 years. A total of 59.8% were married and 42.5% were graduates. A higher proportion was Saudis (80.8%), employed (53.9%), and lived in urban areas (82.1%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the participants.

| Variable | Total (N = 609) |

|

|---|---|---|

| No (%) | ||

| Gender | Male | 290 (47.6%) |

| Female | 319 (52.4%) | |

| Age | <20 years | 31 (5.1%) |

| 20–39 years | 371 (60.9%) | |

| 40–59 years | 187 (30.7%) | |

| > = 60 years | 20 (3.3%) | |

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 224 (36.8%) |

| Married | 364 (59.8%) | |

| Others | 21 (3.4%) | |

| Education | Primary School | 20 (3.3%) |

| Secondary School | 67 (11.0%) | |

| Diploma | 175 (28.7%) | |

| Graduate | 259 (42.5%) | |

| Post Graduate | 88 (14.4%) | |

| Nationality | Saudi | 492 (80.8%) |

| Indian | 37 (6.1%) | |

| Egyptian | 23(3.8%) | |

| Pakistani | 15 (2.5%) | |

| Yemeni | 18 (3.0%) | |

| Bangladeshi | 6 (1.0%) | |

| Sudani | 9 (1.5%) | |

| Others | 9 (1.5%) | |

| Occupation | Unemployed | 184 (30.2%) |

| Employed | 328 (53.9%) | |

| Housewife | 97 (15.9%) | |

| Area of residence | Rural | 109 (17.9%) |

| Urban | 500 (82.1%) | |

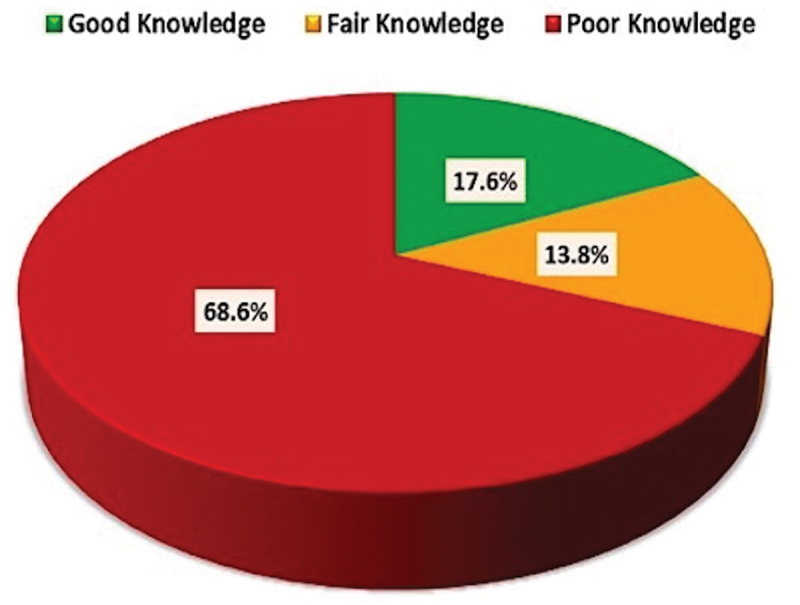

Of 609 participants who participated in the study, 17.6% (107 out of 609) had good knowledge, 13.8% (84 out of 609) had fair knowledge and 68.6% (418 out of 609) had poor knowledge about the booster dose (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Levels of knowledge about booster dose.

Significant differences in the level of knowledge were found in association with gender, area of residency, education, nationality, and occupation (Table 2). The distribution of the level of knowledge differs significantly between groups of male and female participants (P-value <0.05). The distribution of level of good knowledge was significantly higher among the group of female participants compared to male participants (P-value <0.05). The distribution of the level of knowledge did not differ significantly across various age and marital status groups of the participants (P-value >0.05), however increasing age groups revealed comparatively good and fair knowledge compared to their younger counterparts.

Table 2.

Association of socio-demographic variables with the knowledge levels.

| Variable | Good Knowledge (N = 107) |

Fair Knowledge (N = 84) |

Poor Knowledge (N = 418) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 69 (23.8%) | 39 (13.4%) | 182 (62.8%) | .001** |

| Female | 38 (11.9%) | 45 (14.1%) | 236 (74.0%) | ||

| Age | <20 years | 5 (16.1%) | 4 (12.9%) | 22 (71.0%) | .845NS |

| 20–39 years | 71 (19.1%) | 48 (12.9%) | 252 (67.9%) | ||

| 40–59 years | 29 (15.5%) | 28 (15.0%) | 130 (69.5%) | ||

| > = 60 years | 2 (10.0%) | 4 (20.0%) | 14 (70.0%) | ||

| Area of residency | Rural | 12 (11.0%) | 10 (9.2%) | 87 (79.8%) | .021* |

| Urban | 95 (19.0%) | 74 (14.8%) | 331 (66.2%) | ||

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 41 (18.3%) | 32 (14.3%) | 151 (67.4%) | .106NS |

| Married | 66 (8.1%) | 46 (12.6%) | 252 (69.2%) | ||

| Others | 0 (0.0%) | 6 (28.6%) | 15 (71.4%) | ||

| Education | Primary School | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (15.0%) | 17 (85.0%) | <.001** |

| Secondary School | 6 (9.0%) | 5 (7.5%) | 56 (83.6%) | ||

| Diploma | 19 (10.9%) | 26 (14.9%) | 130 (74.3%) | ||

| Graduate | 45 (17.4%) | 38 (14.7%) | 176 (68.0%) | ||

| Post Graduate | 37 (42.0%) | 12 (13.6%) | 39 (44.3%) | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 74 (15.0%) | 65 (13.2%) | 353 (71.7%) | <.001** |

| Indian | 20 (54.1%) | 6 (16.2%) | 11 (29.7%) | ||

| Egyptian | 4 (17.4%) | 5 (21.7%) | 14 (60.9%) | ||

| Pakistani | 2 (13.3%) | 5 (33.3%) | 8 (53.3%) | ||

| Yemeni | 2 (11.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (88.9%) | ||

| Bangladeshi | 1 (16.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (66.7%) | ||

| Sudani | 3 (33.3%) | 1(11.1%) | 5 (55.6%) | ||

| Others | 1 (11.1%) | 1 (11.1%) | 7 (77.8%) | ||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 28 (15.2%) | 34 (18.5%) | 122 (66.3%) | .013* |

| Employed | 70 (21.3%) | 37 (11.3%) | 221 (67.4%) | ||

| Housewife | 9 (9.3%) | 13 (13.4%) | 75 (77.3%) | ||

P-value for Chi-square test. P-value <.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

*P-value <.05, **P-value <.001, NS-statistically non-significant, higher mean score indicates a higher level of knowledge and vice-versa.

The distribution of level of knowledge (fair or good) was significantly higher among the group of participants from urban areas as compared to the rural areas (P-value <0.05). The distribution of a good level of knowledge was significantly higher among the group of participants with graduation and post-graduation education compared to other lower education groups (P-value <0.05). The distribution of level of knowledge differs significantly among participants of different nationalities (P-value <0.05). The distribution of good knowledge scores was reported among employed participants as compared to unemployed (P-value <0.05).

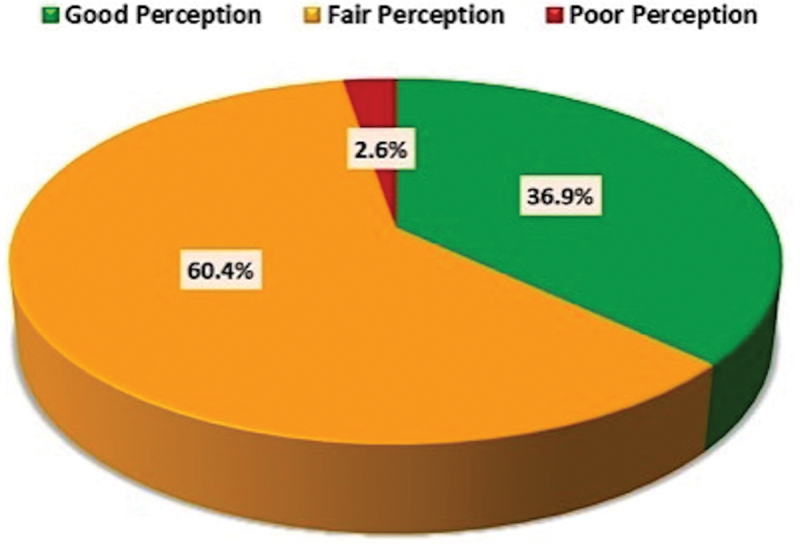

Of 609 participants who participated in the study, about 36.9% (225 out of 609) participants had a good perception, 60.4% (368 out of 609) had a fair perception, while 2.6% (16 out of 609) had a poor perception about the booster dose (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Perceptions for booster dose among the participants.

The distribution of level of perception about booster dose did not differ significantly among participants of different gender, ages, area of residency, and education (P-value >0.05). However, participants from male, young age group and residing in the rural area revealed a slightly better level of perception. Significant differences in the levels of perception were found in association with marital status and nationality. Married participants revealed a good level of perception as compared to unmarried and others (P-value <0.05). On considering nationalities, Sudani and others showed good perception as compared to other nationals, however Saudis and Egyptian nationals presented fair perception level to booster dose (P-value <0.05). The employment status of the participants had no significant impact on the perception level of booster dose (P-value >0.05) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Association of socio-demographic variables with the perception levels.

| Variable | Good Perception (N = 225) |

Fair Perception (N = 368) |

Poor Perception (N = 16) |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. (%) | No. (%) | No. (%) | |||

| Gender | Male | 116 (40.0%) | 164 (56.6%) | 10 (3.4%) | .123NS |

| Female | 109 (34.2%) | 204 (63.9%) | 6 (1.9%) | ||

| Age | <20 | 17 (54.8%) | 13 (41.9%) | 1 (3.2%) | .076NS |

| 20 - 39 | 137 (36.9%) | 226 (60.9%) | 8 (2.2%) | ||

| 40 - 59 | 69 (36.9%) | 112 (59.9%) | 6 (3.2%) | ||

| > = 60 | 2 (10.0%) | 17 (85.0%) | 1 (5.0%) | ||

| Area of residency | Rural | 35 (32.1%) | 68 (62.4%) | 6 (5.5%) | .078NS |

| Urban | 190 (38.0%) | 300 (60.0%) | 10 (2.0%) | ||

| Marital Status | Unmarried | 78 (34.8%) | 141 (62.9%) | 5 (2.2%) | .036* |

| Married | 145 (39.8%) | 208 (57.1% | 11 (3.0%) | ||

| Others | 2 (9.5%) | 19 (90.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Education | Primary School | 3 (15.0%) | 17 (85.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | .174NS |

| Secondary School | 27 (40.3%) | 37 (55.2%) | 3 (4.5%) | ||

| Diploma | 61 (34.9%) | 107 (61.1%) | 7 (4.0%) | ||

| Graduate | 96 (37.1%) | 157 (60.6%) | 6 (2.3%) | ||

| Post Graduate | 38 (43.2%) | 50 (56.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Nationality | Saudi | 171 (34.8%) | 309 (62.8%) | 12 (2.4%) | .017* |

| Indian | 16 (43.2%) | 21 (56.8%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Egyptian | 8 (34.8%) | 15 (65.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Pakistani | 7 (46.7%) | 6 (40.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | ||

| Yemeni | 8 (44.4%) | 8 (44.4%) | 2 (11.1%) | ||

| Bangladeshi | 2 (33.3%) | 4 (66.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Sudani | 7 (77.8%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Others | 6 (66.7%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Occupation | Unemployed | 67 (36.4%) | 107 (58.2%) | 10 (5.4%) | .079NS |

| Employed | 122 (37.2%) | 202 (61.6%) | 4 (1.2%) | ||

| Housewife | 36 (37.1%) | 59 (60.8%) | 2 (2.1%) | ||

P-value for Chi-square test. P-value <.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

*P-value <.05, NS-statistically non-significant, higher mean score indicates a higher level of knowledge and vice-versa.

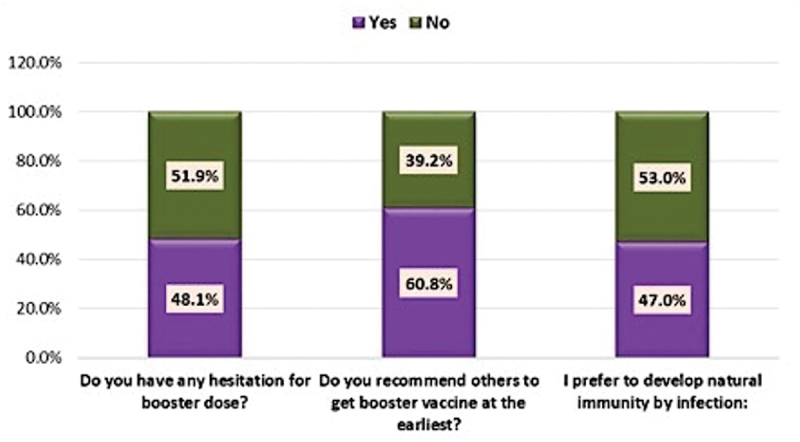

Of 609 participants who participated in the study, 48.1% (293 out of 609) participants reported hesitation to a booster dose. A total of 60.8% (370 out of 609) recommended others to get the booster vaccine at the earliest, whereas 47.0% (286 out of 609) preferred to develop natural immunity by infection (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Acceptance for booster dose among the participants.

A higher proportion (55%) of the rural participants compared to urban ones (46.6%) revealed hesitation to a booster dose. About 62.8% of the urban participants compared to 51.4% of the rural ones recommended others to get the booster vaccine at the earliest, the difference being statistically significant. A higher proportion of the rural participants (49.5%) compared to urban participants (46.5%) had a preference to develop natural immunity by infection. A higher proportion (60%) of participants aged ≥60 years had a hesitation for booster dose as compared to other age groups (45.2%–48.7%). About 71.0% of the participants aged <20 years recommended others to get the booster vaccine at the earliest as compared to other age groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Relation of demographic variables and acceptance for a booster dose.

| Variables | Acceptance |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesitation for the booster dose |

p-value | Recommend others to get the booster dose at the earliest |

p-value | Preference to develop natural immunity by infection |

p-value | |||||

| Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | Yes (%) | No (%) | |||||

| Area of residency | Rural | 60(55.0%) | 49(45.0%) | .110NS | 56(51.4%) | 53(48.6%) | .027* | 54(49.5%) | 55(50.5%) | .564NS |

| Urban | 233(46.6%) | 267(53.4%) | 314(62.8%) | 186(37.2%) | 232(46.5%) | 267(53.5%) | ||||

| Age (in yrs) | <20 | 14(45.2%) | 17(54.8%) | .722NS | 22(71.0%) | 9(29.0%) | .474NS | 11(35.5%) | 20(64.5%) | .400NS |

| 20 - 39 | 176(47.4%) | 195(52.6%) | 227(61.2%) | 144(38.8%) | 182(49.2%) | 188(50.8%) | ||||

| 40 - 59 | 91(48.7%) | 96(51.3%) | 111(59.4%) | 76(40.6%) | 83(44.4%) | 104(55.6%) | ||||

| > = 60 | 12(60.0%) | 8(40.0%) | 10(50.0%) | 10(50.0%) | 10(50.0%) | 10(50.0%) | ||||

| Gender | Male | 124(42.8%) | 169(53.0%) | .012* | 199(68.6%) | 171(53.6%) | <.001* | 135(46.7%) | 151(47.3%) | .878NS |

| Female | 169(53.0%) | 150(47.0%) | 91(31.4%) | 148(46.4%) | 154(53.3%) | 168(52.7%) | ||||

| Education | Primary | 6(30.0%) | 14(70.0%) | .056NS | 15(75.0%) | 5(25.0%) | .280NS | 10(50.0%) | 10(50.0%) | .179NS |

| Secondary | 34(50.7%) | 33(49.3%) | 46(68.7%) | 21(31.3%) | 29(43.3%) | 38(56.7%) | ||||

| Diploma | 97(55.4%) | 78(44.6%) | 99(56.6%) | 76(43.4%) | 93(53.1%) | 82(46.9%) | ||||

| Graduate | 121(46.7%) | 138(53.3%) | 159(61.4%) | 100(38.6%) | 121(46.9%) | 33(37.5%) | ||||

| Postgraduate | 35(39.8%) | 53(60.2%) | 51(58.0%) | 37(42.0%) | 137(53.1%) | 55(62.5%) | ||||

P-value for Chi-square test. P-value <.05 is considered to be statistically significant.

*P-value <.05, **P-value <.001, NS-statistically non-significant, higher mean score indicates a higher level of knowledge and vice-versa.

A higher proportion of the participants aged ≥60 years (50.0%) as compared to other age groups had a preference to develop natural immunity due to infection. A significantly higher proportion (53%) of females had a hesitation for booster dose as compared to males (42.8%). About 68.6% of the males recommended others to get the booster vaccine at the earliest as compared to females (53.5%), the difference being statistically significant. A slightly higher percentage of females (53.3%) as compared to males (47.7%) preferred to develop natural immunity by infection. Insignificant differences were found in acceptance of booster dose among participants of different education levels. A higher proportion of the postgraduates (62.5%) did not have a preference to develop natural immunity by infection as compared to those with lower educational levels (46.9%–56.7%) (Table 4).

Discussion

The suffering of the people from COVID-19 over the last 2 years is beyond words, and it has influenced all aspects of human life including their health. Numerous studies have been conducted around the world to evaluate the effects of COVID-19 on the population.29–33 Most of the medications only provide symptomatic relief. There is no definitive curative treatment available at present, so the only possible way out rests on the vaccination of the masses. The success of the vaccination program in any country depends on the knowledge, awareness, and acceptance of the vaccination process by the people in the country. Most of the countries around the world have already started implementing the recommended two-doses of vaccines program. But as the new variants of the SARS-CoV-2 are still affecting the health of the population, it becomes apparent to develop the booster vaccines to counter these new variants, especially the delta (B.1.617.2 and AY lineages) and Omicron (B.1.1.529).34 To ensure the success of booster vaccine program, people must understand their importance.35,36 To gain an in-depth understanding of this preparedness, the current study was aimed at evaluating the knowledge, perception, and acceptance of the people in Saudi Arabia toward the vaccine booster program.

In the current study, a total of 609 individuals have participated in this study. Most of the participants were females (52.4%), and the majority were aged between 20 and 39 years. These figures resemble another study in Saudi Arabia where the female participants were more (56.4%) as compared to the males.36 The Saudi citizens constituted 80.8% of the target population, which is similar to another study where Saudi citizens constituted more than 98% of the study population.36 59.8% of the population was married and 82.1% of the participants were from the urban areas. 42.5% of the participants had completed their graduation and 53.9% were employed.

As far as the knowledge part is concerned, more than half of the participants (68.6%) had poor knowledge of the booster, whereas 17.6% had good knowledge and 13.8% had fair knowledge. There was a statistically significant difference in the level of knowledge among the male and female participants (P-value <.05). The increase in age correlated with the increased level of knowledge, although it was not statistically significant. The distribution of knowledge was significantly better in people from urban areas and those with graduation/post-graduation degrees, as compared to the people from the rural areas and those who were less educated (P-value <.05). Significantly higher (good) levels of knowledge were recorded among the participants who were employed as compared to the others.

While assessing the attitude for the booster dose, the majority of the participants (60.4%) had a fair perception, 36.9% had a good perception and 2.6% had a poor perception. The perception was better among the male participants, among the younger age groups, and those residing in the rural areas. The married participants had significantly better (good level) perceptions than the unmarried ones. From among the participants of different nationalities, the Sudani nationals had a good level of perception, while the Saudi and Egyptians had a fair level of perception.

Half of the participants (48.1%) were hesitant toward the booster dose, which was in contrast to a study in China,37 where 84.8% of the participants accepted the booster doses. These figures were roughly similar to an earlier study about vaccination acceptance in Saudi Arabia,36 wherein 60.8% of participants were worried about vaccine side effects, 61% were afraid of injection and 48.2% feared allergic complications. The hesitation for vaccination is more in comparison to a study in the American population wherein 38.2% of the participants were reluctant for the booster dose.38 The acceptance of vaccination and booster depends upon the trust of the participants upon the experts in the field (scientists and health-care workers).39 In a study, significantly higher percentage of vaccine booster hesitant people had less trust in the information provided by the government agencies about the vaccines.39

Insignificant differences were found in acceptance of booster doses among the participants of different education levels, which contrasts with a study in America where less educated, single/unmarried, and participants living in the southern part of the nation were more hesitant to vaccine booster program. However, 60.8% of the participants recommended others to get the booster vaccination at the earliest. Almost half (47%) of the participants preferred to develop natural immunity through infection, which is slightly less than an earlier study about vaccine acceptance in Saudi Arabia, in which 53.2% of participants thought that getting a disease naturally was a much safer way of developing immunity than the vaccine.36 There was a difference between the rural and urban populations toward the booster vaccine acceptance.

More of the rural people (55%) were hesitant toward the booster as compared to the urban (46.6%). A significantly higher number of the urban people (62.8%) recommended the earliest vaccination of others as compared to the rural ones (51.4%). More rural participants (49.5%) preferred the natural immunity to develop through infection as compared to the urban ones (46.5%). A higher proportion of elderly participants were hesitant toward the booster dose as compared to the other age groups and the hesitation was significantly more in females as compared to the males. In contrast, significantly, a higher number of males recommended booster to others at the earliest, as compared to the females. The female participants are more inclined to the development of natural immunity by infection as compared to the males. On the other hand, higher proportions of the postgraduates were not in favor of the idea to get infected to develop natural immunity, as compared to others.

Our study has a few limitations. The cross-sectional design cannot confirm the causality of the relationship between the compared variables. The self-reported response could over or underestimate the result. The responses were collected through online and face to face questionnaires that could have led to subjective variation in the responses. The study’s weakness is that it was conducted in a single city of the Aseer Region of KSA. We should have used convergent and discriminant validity to provide a more valid judgment of the questionnaire validity. We hope in the future to have all the required resources to do multicentric studies. However, the strength of our study was that representative samples were taken of people attending various dental clinics that were widely dispersed in the city, making it heterogenous and all-encompassing.

Thus, the study underlies the beliefs, awareness, and judgment of the people of Saudi Arabia regarding the uptake of the booster vaccine, and the government agencies need to communicate effectively with the people regarding the benefits of the vaccine to increase the vaccinated population in the country, which will help clear the COVID-19 pandemic effectively.

Conclusions

We can conclude that more than half of the participants had poor knowledge about the booster dose. The knowledge level was higher in the urban and educated population. There was a statistically significant difference in the level of knowledge among male and female participants. The perception was better among males, younger age groups and those residing in the rural areas. Almost half of the population were hesitant toward the booster dose, more rural than urban population. However, a large number of people recommended others to get the booster at the earliest. Health-care agencies and professionals recommend all to take the booster dose as it seems to be the surest and fastest way to safeguard ourselves and also control the pandemic.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their appreciation to the Deanship of Scientific Research at King Khalid University, Abha, Saudi Arabia, for funding this work through the Large Research Group Project under grant number (RGP-2/234/1443).

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Supporting data are available on request from author Shahabe Saquib (drsaquib24@gmail.com).

Institutional review board statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of KING KHALID UNIVERSITY (IRB/KKUCOD/ETH/2020-21/020).

Informed consent statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website at https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2022.2095162.

References

- 1.World Health Organization . Coronavirus disease (COVID-19). Situation Report-130. World Health Organization; 2020. May 29 [accessed Nov 30]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200529-covid-19-sitrep-130.pdf?sfvrsn=bf7e7f0c_4. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization . DRAFT landscape of COVID-19 candidate vaccines. World Health Organization; 2020. June 24 [accessed Nov 30]. https://www.who.int/who-documents-detail/draft-landscapeof-covid-19-candidate-vaccines. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sanger DE, Kirkpatrick DD, Zimmer C, Thomas K, Wee SL.. Profits and pride at stake, the race for a vaccine intensifies. The New York Times. 2020. May 2 [accessed Nov 30]. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/02/us/politics/vaccines-coronavirus-research.html.

- 4.Corbett KS, Gagne M, Wagner DA, O’Connell S, Narpala SR, Flebbe DR, Andrew SF, Davis RL, Flynn B, Johnston TS, et al. Protection against SARS-CoV-2 Beta variant in mRNA-1273 vaccine–boosted nonhuman primates. Science. 2021;374(6573):1–8. Epub 2021 Oct 21. PMID: 34672695. doi: 10.1126/science.abl8912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Andrews N, Stowe J, Kirsebom F, Toffa S, Rickeard T, Gallagher E, Gower C, Kall M, Groves N, O’Connell AM, et al. Covid-19 vaccine effectiveness against the Omicron (B.1.1.529) variant. N Engl J Med. 2022;386(16):1532–1546. Epub 2022 Mar 2. PMID: 35249272. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2119451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.World Health Organization . World Health Organization outbreak communication planning guide. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2008. [accessed Nov 30]. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0277-9536(20)30575-X/sref49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Funke D. Rush Limbaugh is spreading a conspiracy theory about the Coronavirus and Trump’s re-election. Washington (DC): Poynter Institute; 2020. [accessed Nov 30]. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0277-9536(20)30575-X/sref13. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Infotagion . Factcheck: is COVID-19 a “Big Pharma” Conspiracy? 2020. [accessed Nov 30]. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0277-9536(20)30575-X/sref22.

- 9.Lee BY. No, COVID-19 was not bioengineered. Here’s the research that Debunks that idea. Forbes. 2020. [accessed Nov 30]. http://refhub.elsevier.com/S0277-9536(20)30575-X/sref28.

- 10.Lewandowsky S, Ecker UKH, Seifert CM, Schwarz N, Cook J. Misinformation and its correction: continued influence and successful debiasing. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2012;13(3):106–131. PMID: 26173286. doi: 10.1177/1529100612451018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Uscinski JE, Klofstad C, Atkinson MD. What drives conspiratorial beliefs? the role of informational cues and predispositions. Political Res Q. 2016;69:57–71. doi: 10.1177/1065912915621621. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Douglas KM, Uscinski JE, Sutton RM, Cichocka A, Nefes T, Ang CS, Deravi F. Understanding conspiracy theories. Polit Psychol. 2019;40:3–35. doi: 10.1111/pops.12568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hornsey MJ, Finlayson M, Chatwood G, Begeny CT. Donald Trump and vaccination: the effect of political identity, conspiracist ideation and presidential tweets on vaccine hesitancy. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2020;88:103947. doi: 10.1060/j.jesp.2019.103947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jolley DD, Douglas KM. The effects of anti-vaccine conspiracy theories on vaccination intentions. PloS One. 2014;9(2):389177. PMID: 24586574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Greenwood B. The contribution of vaccination to global health: past, present and future. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2014;369(1645):20130433. PMID: 24821919. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2013.0433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daniel RD, Jamieson KH. Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of COVID-19 in the U.S. Soc Sci Med. 2020;263:113356. PMID: 32967786. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glanz K, Rimer BK, Viswanath K. Health behavior and health education: theory, research, and practice. 4th ed. San Fracisco: John Wiley & Sons; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Becker MH, Maiman LA, Kirscht JP, Haefner DP, Drachman RH. The health belief model and predic- tion of dietary compliance: a field experiment. J Health Soc Behav. 1977;18(4):348–366. PMID: 617639. doi: 10.2307/2955344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lucia VC, Kelekar A, Afonso NM. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among medical students. J Public Health (Oxf). 2021;43:445–449. PMID: 33367857. doi: 10.1093/pubmed/fdaa230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang R, Penders B, Horstman K. Addressing vaccine hesitancy in China: a Scoping Review of Chinese Scholarship. Vaccines. 2019;8(1):2. PMID: 31861816. doi: 10.3390/vaccines8010002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarawneh O, Tarawneh H. Immune thrombocytopenia in a 22-year-old post Covid-19 vaccine. Am J Hematol. 2021;96(5):E133–E134. PMID: 33476455. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garvey LH, Nasser S. Anaphylaxis to the first COVID-19 vaccine: is polyethylene glycol (PEG) the culprit? COVID-19 CORRESPONDENCE. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126(3):e106–e108. PMID: 33386124. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Widge AT, Rouphael NG, Jackson LA, Anderson EJ, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Stevens LJ, Pruijssers AJ, et al. Durability of responses after SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccination. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(1):80–82. PMID: 3327038. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2032195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Anderson EJ, Rouphael NG, Widge AT, Jackson LA, Roberts PC, Makhene M, Chappell JD, Denison MR, Stevens LJ, Pruijssers AJ, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of SARS-CoV-2 mRNA-1273 vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:2427–2438. PMID: 32991794. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2028436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shrotri M, Navaratnam AM, Nguyen V, Byrne T, Geismar C, Fragaszy E, Beale S, Fong WLE, Patel P, Kovar J, et al. Spike-Antibody waning after second dose of BNT162b2 or ChAdox1. Lancet. 2021;398(10298):385–387. PMID: 34274038. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01642-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mizrahi B, Lotan R, Kalkstein N, Peretz A, Perez G, Ben-Tov A, Chodick G, Gazit S, Patalon T. Correlation of SARS-CoV-2 breakthrough infections to time-from-vaccine. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6379. PMID: 34737312. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26672-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shekhar R, Garg I, Pal S, Kottewar S, Sheikh AB. COVID-19 vaccine booster: to boost or not to boost. Infect Dis Rep. 2021;13:924–929. PMID: 34842753; PMCID: PMC8628913. doi: 10.3390/idr13040084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Arora S, Abullais SS, Attar N, Pimpale S, Saifullah ZK, Saluja P, Abdulla AM, Shamsuddin S. Evaluation of knowledge and preparedness among Indian dentists during the current COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2020;13:841–854. PMID: 32922024. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S268891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hemmer CJ, Löbermann M, Reisinger EC. COVID-19: epidemiology and mutations: an update. Radiologe. 2021;61(10):880–887. PMID: 34542699. doi: 10.1007/s00117-021-00909-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blanco JR, Cobos-Ceballos MJ, Navarro F, Sanjoaquin I, Arnaiz de Las Revillas F, Bernal E, Buzon-Martin L, Viribay M, Romero L, Espejo-Perez S, et al. Pulmonary long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections after hospital discharge. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2021;27:892–896. PMID: 33662544. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2021.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ioannou P, Karakonstantis S, Astrinaki E, Saplamidou S, Vitsaxaki E, Hamilos G, Sourvinos G, Kofteridis DP. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 variant B.1.1.7 among vaccinated health care workers. Infect Dis (Lond). 2021;53(11):876–879. PMID: 34176397. doi: 10.1080/23744235.2021.1945139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shi JC, Yu ZJ, He GQ, Chen W, Ye XC, Wu ZX, Zhu XQ, Pan JZ, Jiang XG. Epidemiological features of 105 patients infected with the COVID-19. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113:212–217. PMID: 33268103. doi: 10.1016/j.jnma.2020.09.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Center for Disease Control and Prevention . SARS-CoV-2 variant classifications and definitions. 2021. Nov 30 [accessed Dec 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/variants/variant-info.html.

- 34.Center for Disease Control and Prevention . COVID-19 vaccine booster shots. 2021. Nov 30 [accessed Dec 30]. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/vaccines/booster-shot.html.

- 35.EMA Pandemic Task Force for COVID-19 . Heterologous primary and booster COVID-19 vaccination evidence based regulatory considerations. 2021. Dec 13 [accessed Dec 30]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/report/heterologous-primary-booster-covid-19-vaccination-evidence-based-regulatory-considerations_en.pdf.

- 36.Alduwayghiri EM, Khan N. Acceptance and attitude toward COVID-19 vaccination among the public in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2021;22:730–734. PMID: 34615775. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10024-3114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yadete T, Batra K, Netski DM, Antonio S, Patros MJ, Bester JC. Assessing acceptability of COVID-19 vaccine booster dose among adult Americans: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1424. PMID: 3496017. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai X, Zhu H, Wang J, Huang Y, Jing R, Lyu Y, Zhang H, Feng H, Guo J, Fang H. Public perceptions and acceptance of COVID-19 booster vaccination in China: a cross-sectional study. Vaccines (Basel). 2021;9(12):1461. PMID: 34960208. doi: 10.3390/vaccines9121461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Toro-Ascuy D, Cifuentes-Muñoz N, Avaria A, Pereira-Montecinos C, Cruzat G, Zorondo-Rodriguez F, Fuenzalida LF. Underlying factors that influence the acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine in a country with a high vaccination rate. Vaccines (Basel). 2022;10:681. PMID: 35632437. doi: 10.3390/vaccines10050681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Supporting data are available on request from author Shahabe Saquib (drsaquib24@gmail.com).