Background:

Despite growing rates of postmastectomy breast reconstruction, the time contribution of breast reconstruction surgeons in comprehensive breast cancer care is often poorly accounted for by hospital and healthcare systems. This study models encounter volume and operative time utilization of breast reconstruction surgeons among patients undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction.

Methods:

All clinical encounters and operative time from a consecutive sample of breast cancer patients undergoing mastectomy and reconstruction were analyzed. Encounter volume and operative time utilization less than or equal to 4 years after diagnosis were modeled over time.

Results:

A total of 5057 breast cancer encounters were analyzed. Mean (SD) clinical encounter volume was 45.9 (28.5) encounters per patient, with encounter volume varying by specialty [plastic surgery: 16.5; medical oncology: 15.9; breast surgery: 7.2; radiation oncology: 6.3 mean encounters]. Receipt of adjuvant radiation, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, and major complications during reconstruction predicted higher encounter volume. Mean (SD) operative time utilization was 702 (317) minutes per patient [plastic surgery: 547 (305); breast surgery: 155 (71) minutes]. While both encounter volume and operative time for radiation oncologists and breast surgeons, respectively, were concentrated in the first year after diagnosis, medical oncologists and plastic surgeons sustained high clinical and operative time utilization 3 years after breast cancer diagnosis.

Conclusions:

Encounter volume and operative time utilization with breast reconstruction surgeons persist 3 years after a breast cancer diagnosis and are tied to treatment characteristics and incidence of reconstruction complications. Institutional- and system-level resource allocation must account for the complex and lengthy duration of care inherent to breast reconstruction care.

Takeaways

Question: How many encounters are necessary to reach completion of breast cancer treatment and reconstruction?

Findings: In a review of 5000 clinical encounters, patients undergoing breast reconstruction had the highest numbers of total encounters and operative minutes with plastic surgeons compared with other breast cancer specialties, and plastic surgery encounter utilization continued up to 3 years after diagnosis.

Meaning: This study emphasizes the quantity and duration of clinical and operative effort required by plastic surgeons to care for patients undergoing breast reconstruction.

INTRODUCTION

With evolving healthcare systems toward value-based payment structures, defining the value that plastic surgeons bring to medical centers has become increasingly important in recent years.1 As a field, plastic surgeons serve as essential operative consultants to other specialties, contributing higher case complexity which in turn generates downstream revenue for hospital systems.2,3 In addition to providing favorable profit margins, plastic surgeons contribute value to healthcare systems through time allocation and duration of clinical care, as reconstructive surgeons often assume long-term surgical follow-up including care for long-term complications. However, despite substantial time and financial contributions, the time contribution and encounter effort of plastic surgeons within academic medical systems remains poorly captured by hospitals and healthcare systems nationally.2

Postmastectomy breast reconstruction is one clinical example that requires significant time expenditure by plastic surgeons within medical centers. Pursuit of breast reconstruction has been associated with substantial psychosocial benefits after mastectomy and is an essential component of comprehensive breast cancer care.4–6 Owing to the well-documented benefits and passage of the Women’s Health and Cancer Right’s Act in 1998, there is a rising population of patients electing to pursue postmastectomy breast reconstruction,7,8 exceeding 130,000 procedures in 2020.9 With this growth, the resource demands required by cancer centers and institutions to care for this population has also risen considerably over the past decade. As the overall incidence of breast cancer and the breast reconstruction patient population continues to grow,10 appropriate allocation of operating room time, clinic space, and hiring patterns for breast reconstruction surgeons to meet this growth becomes essential to allow for expansion and sustainability of clinical programs. However, to date, the clinical and operative effort of breast reconstruction surgeons has yet to be quantified and often remains underestimated by academic medical centers and healthcare systems.

This study aimed to define the value of breast reconstruction surgeons by modeling the longitudinal encounter volume and operative time utilization required to care for a population of patients undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction. We hypothesized that breast reconstruction surgeons contribute substantial encounter time and operative utilization several years after an initial breast cancer diagnosis, findings that could inform system-level reimbursement models and institution-level models of clinic and operating room space needed to care for the growing population of breast reconstruction patients nationally.

METHODS

After institutional review board approval, the medical records of all consecutive patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy at Duke University from 2017 to 2018 were reviewed. Patients were included who had 4 years or more of follow-up, who underwent breast reconstruction, and who underwent the entirety of their breast cancer care (including medical oncology, radiation if applicable, mastectomy, reconstruction, and long-term follow-up) at Duke University. Exclusion criteria included bilateral prophylactic mastectomies performed without a diagnosis of breast cancer, less than 4 years of documented follow-up in the medical record, receipt of any breast cancer-related care at an outside institution, or documented mortality during the study period. All breast cancer-related encounters available in the electronic medical records were recorded for each patient. Date of encounter, encounter specialty (medical oncology, radiation oncology, breast surgery, or plastic surgery), and encounter type [new patient visit, established patient or postoperative visit, including expansion, minor procedure (including nipple areolar tattooing, or revisions under local anesthesia in the clinic), surgery (including re-operations for complications and revisions), chemotherapy or radiation treatment visits, and telephone encounters/electronic medical record messages] were recorded for each encounter. Encounters were modeled by quarter after diagnosis (90-day periods) by provider type and treatment variables.

For every operative encounter, total operative time (defined as skin incision to closure) was recorded in minutes. For joint cases (ie, mastectomy with tissue expander placement or mastectomy with immediate free flap), the recorded time in the medical record when surgeons scrubbed in and out was used to calculate respective mastectomy and respective reconstruction operative times.

Oncologic variables included breast cancer overall stage (American Joint Committee on Cancer 8th edition), hormone receptor status, breast cancer laterality, treatment history, including receipt of neoadjuvant and/or adjuvant and adjuvant radiation, type of mastectomy, occurrence of germline genetic mutations, and occurrence of a major (defined to require operative intervention) or minor (defined to require nonoperative management) complication during breast reconstruction. Reconstruction variables collected included reconstructive subtype [tissue expander (TE)-to-implant, TE-to-free flap, immediate free flap, pedicled autologous reconstruction] and numbers of revisions.

Demographic, oncologic, and reconstructive characteristics were summarized using frequency and percentage for categorical variables or mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables, respectively. Encounters were modeled each quarter (90-day period) after diagnosis, stratified by provider specialty. Within surgical subspecialties, operative time was modeled over time by years after diagnosis. Multivariable linear regression models were used to identify candidate predictors of higher encounter volume and operative time across the cohort. The analysis was conducted in R (R Core Team 2021, Vienna, Austria).

RESULTS

Of the 356 patients undergoing mastectomy from 2017 to 2018, 110 patients underwent breast reconstruction and met the inclusion criteria of the study. Oncologic and reconstructive characteristics are summarized in Supplemental Digital Content 1 [See table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows oncologic and reconstruction details of the cohort (N = 110 patients. http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C304]. Briefly, most patients had ER+ (73.6%) PR+ (70.0%) invasive ductal carcinoma (63.6%) or ductal carcinoma in situ (40.9%) and most were of overall stages 0-IIA. Twenty-nine patients underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy (26.4%), 39 received adjuvant chemotherapy (36.1%), and 32 underwent adjuvant radiation (29.6%). Regarding reconstruction history, the majority of the cohort underwent TE-to-implant reconstruction (51.6%) or either staged or immediate free flap reconstruction (46.6%). Among patients undergoing free flap reconstruction, most received deep inferior epigastric artery perforator flaps. Major complications after reconstruction requiring a return to the operating room occurred in 28 patients (25.5%), whereas minor complications occurred in 22 patients (20.0%) (Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/PRSGO/C304).

From the 110 included patients, 5057 breast cancer–related encounters were collected and modeled over time. While 1.4% of encounters occurred before breast cancer diagnosis, most encounters occurred in the first year after diagnosis (65.5%), with years 2, 3, and 4 after diagnosis representing 19.4%, 9.8%, and 4.0% of all respective recorded encounters. Most encounters were established clinic visits (45.0%) or either chemotherapy or radiation treatment visits (25.2%). Telephone encounters or electronic medical record messaging accounted for 9.4% of all encounters (Table 1). Mean (SD) clinical encounter volume was 45.9 (28.5) encounters per patient, and mean (SD) encounter volume per patient varied between specialties [plastic surgery: 16.5 (12.7); medical oncology: 15.9 (14.8); breast surgery: 7.2 (3.7); radiation oncology: 6.3 (11.2) mean encounters]. Although mean encounter volume increased with overall breast cancer stage for radiation oncology and medical oncology, encounter volume for plastic surgery and breast surgery did not vary by breast cancer stage (Table 2).

Table 1.

Characterization of All Breast Cancer-related Encounters of Those Who Underwent Breast Reconstruction (N = 5057 encounters)

| Total Cohort | Medical Oncology | Radiation Oncology | Plastic Surgery | Breast Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of encounters | N = 5057 | 1750 (34.7%) | 690 (13.7%) | 1819 (36.1%) | 787 (15.6%) |

| No. encounters: before diagnosis | 69 (1.4%) | 21 (1.2%) | 11 (1.6%) | 5 (0.3%) | 32 (4.1%) |

| No. encounters: year 1 | 3314 (65.5%) | 1129 (64.5%) | 626 (90.7%) | 923 (50.7%) | 629 (79.9%) |

| No. encounters: year 2 | 980 (19.4%) | 297 (17.0%) | 43 (6.2%) | 565 (31.1%) | 72 (9.1%) |

| No. encounters: year 3 | 493 (9.8%) | 212 (12.1%) | 7 (1.0%) | 238 (13.1%) | 36 (4.6%) |

| No. encounters: year 4+ | 201 (4.0%) | 91 (5.2%) | 3 (0.4%) | 88 (4.8%) | 18 (2.3%) |

| Encounter type | (N = 5045) | ||||

| New patient clinic visit | 378 (7.5%) | 97 (5.6%) | 77 (11.2%) | 90 (4.9%) | 114 (14.5%) |

| Established clinic visit | 2268 (45.0%) | 722 (41.3%) | 114 (16.5%) | 1022 (56.2%) | 409 (52.0%) |

| Minor procedure/expansion | 208 (4.1%) | 2 (0.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 204 (11.2%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Surgery | 362 (7.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 222 (12.2%) | 140 (17.8%) |

| Revision | 26 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 25 (1.4%) | 1 (0.1%) |

| Re-operation for complications | 58 (1.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 56 (3.1%) | 2 (0.3%) |

| Treatment (chemo, XRT) | 1273 (25.2%) | 785 (44.9%) | 487 (70.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Telephone/MyChart Visit | 472 (9.4%) | 141 (8.1%) | 11 (1.6%) | 200 (11.0%) | 120 (15.2%) |

Table 2.

Mean (SD) Number of Encounters for All Breast Cancer Stages by Provider for Those Who Underwent Breast Reconstruction (N = 110 patients)

| Breast Cancer Overall Stage | All | Medical Oncology | Radiation Oncology | Plastic Surgery | Breast Surgery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 45.9 (28.5) | 15.9 (14.8) | 6.3 (11.2) | 16.5 (12.7) | 7.2 (3.7) |

| Stage 0 | 32.4 (12.9) | 3.3 (2.4) | 0.4 (0.5) | 20.6 (11.1) | 8.1 (5.6) |

| Stage I | 34.0 (19.0) | 11.0 (10.2) | 3.3 (8.2) | 13.3 (8.2) | 6.3 (3.3) |

| Stage II | 55.5 (23.0) | 23.0 (12.8) | 7.6 (11.4) | 18.0 (12.0) | 6.7 (3.1) |

| Stage III | 76.6 (41.8) | 30.4 (19.8) | 13.1 (12.6) | 24.1 (22.0) | 8.7 (3.7) |

Multivariable linear regression was then used to identify predictors of encounter volume across provider types (Table 3). Across the cohort, receipt of adjuvant radiation [odds ratio (OR) 18.6; 95% confidence interval (CI) 5.3–31.9; P = 0.007], neoadjuvant chemotherapy (OR 18.3; 95% CI 3.5–33.2; P = 0.02), and major complication incurred during breast reconstruction (OR 12.6; 95% CI 0.3–24.8; P = 0.04) were associated with higher overall encounter volume. Other variables (including breast cancer stage and reconstruction subtype) did not independently predict overall volume.

Table 3.

Multivariate Linear Regression Model Predicting Average Number of Encounters per Year (All Specialties)

| Estimate | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 28.8 | (−16.9, 74.6) | 0.213 |

| Overall stage | |||

| Stage I | REF | REF | REF |

| Stage 0 | 3.7 | (−14.2, 21.5) | 0.681 |

| Stage II | 1.7 | (−11.9, 15.4) | 0.800 |

| Stage III | 9.8 | (−9.8, 29.5) | 0.322 |

| Hormone receptor status | |||

| ER+ | −7.0 | (−30.7, 16.6) | 0.554 |

| PR+ | 10.2 | (−8.9, 29.2) | 0.291 |

| HER2+ | 13.0 | (−2.8, 28.8) | 0.106 |

| Triple negative | 10.2 | (−15.0, 35.3) | 0.422 |

| Tobacco use | |||

| Past | 9.2 | (−3.5, 21.8) | 0.154 |

| Current | −7.7 | (−45.2, 29.9) | 0.684 |

| BMI | −0.1 | (−1.3, 1.1) | 0.857 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 18.3 | (3.5, 33.2) | 0.016 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | 4.8 | (−7.2, 16.8) | 0.423 |

| Neoadjuvant radiation | 8.4 | (−25.6, 42.3) | 0.625 |

| Adjuvant radiation | 18.6 | (5.3, 31.9) | 0.007 |

| Age (y) | −0.2 | (−0.7, 0.4) | 0.575 |

| Germline genetic mutation | 5.5 | (−17.2, 28.3) | 0.629 |

| Bilateral cancer | 2.8 | (−16.5, 22.0) | 0.775 |

| Reconstruction subtype | |||

| TE-to-implant | −3.2 | (−19.5, 13.1) | 0.697 |

| TE-to-free flap | −0.2 | (−18.2, 17.7) | 0.978 |

| Immediate free flap | 7.2 | (−8.8, 23.2) | 0.374 |

| Reconstruction laterality | |||

| Unilateral | REF | REF | REF |

| Bilateral | −0.7 | (−11.9, 10.5) | 0.900 |

| Major complication, reconstruction | 12.6 | (0.3, 24.8) | 0.044 |

| Minor complication, reconstruction | 13.3 | (−0.5, 27.1) | 0.058 |

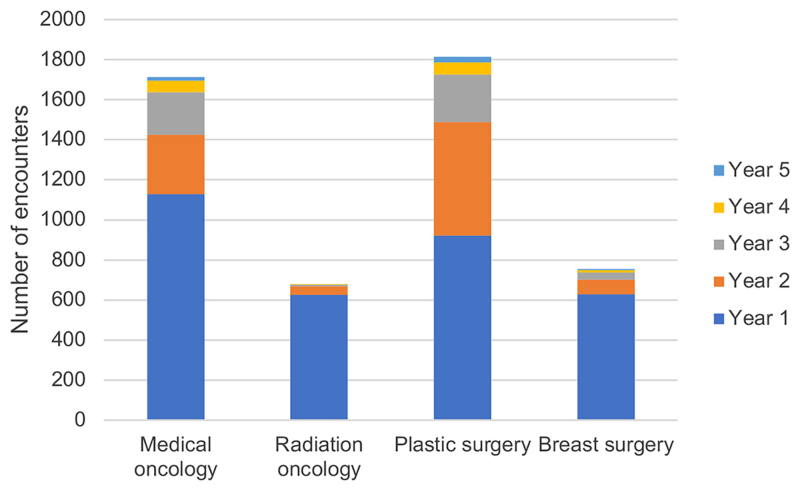

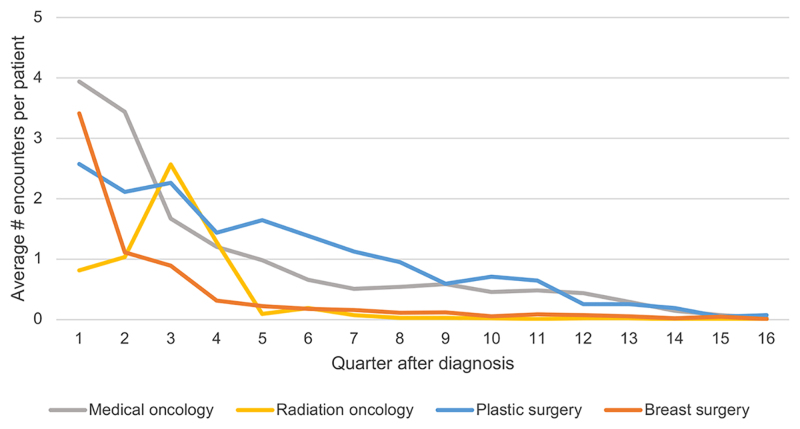

Encounters were then modeled for each provider type by time after diagnosis. Before diagnosis, most visits were with medical oncologists (30.4%) or breast surgeons (46.4%). In year 1 after diagnosis, medical oncologists accounted for 30.4% of encounters, radiation oncologists accounted for 18.9%, plastic surgeons accounted for 27.9%, and breast surgeons accounted for 19.0% of encounters. In years 2 and 3 following diagnosis, most encounters were with medical oncologists (30.3% and 43.0% for years 2 and 3, respectively) and plastic surgeons (56.7% and 48.3% for years 2 and 3, respectively). From year 4 and onward, medical oncology accounted for 45.3% of encounters; plastic surgery, 43.7%; breast surgery, 9.0%; and radiation oncology, 1.0% of encounters (Table 1, Figure 1). Although the majority of encounter volume for breast surgeons and radiation oncologists occurred in the first year after diagnosis (79.9% and 90.7%, respectively), plastic surgeons and medical oncologists continued to have significant encounter volume in years 2 (31.3% and 17.0%, respectively) and 3 (13.1% and 12.1%, respectively) after diagnosis. Maps of encounter volume were then constructed to model fluctuations in encounter volume over time by 90-day periods after diagnosis (Figure 2). Encounter volume of breast surgery and radiation oncology peaked and dropped within 15 months of diagnosis. After 15 months, encounter volume was highest with medical oncology and plastic surgery. Within the 90-day study time frames, both plastic surgery and medical oncology continued to have measurable encounter volume up to 45 months (3.75 years) after diagnosis (Figure 2).

Fig. 1.

Number of encounters each year after breast cancer diagnosis for medical oncology, radiation oncology, plastic surgery, and breast surgery.

Fig. 2.

Average number of encounters per patient every 90 days after breast cancer diagnosis for medical oncology, radiation oncology, plastic surgery, and breast surgery among patients undergoing breast reconstruction (N = 5057 encounters).

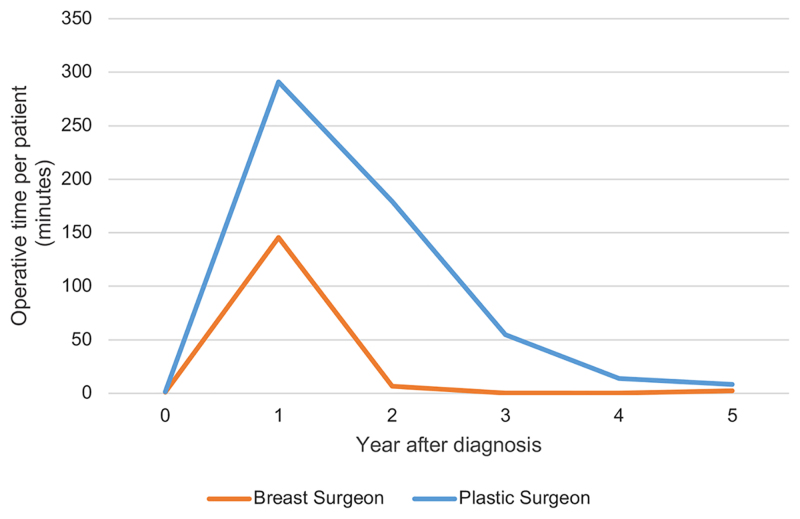

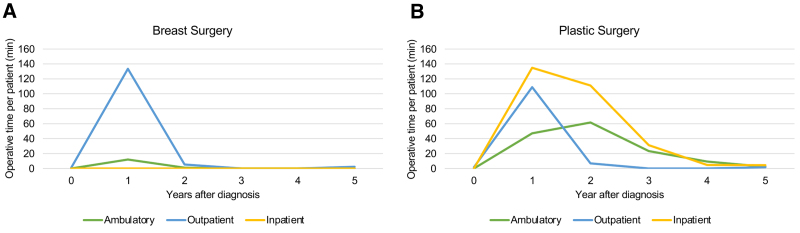

Among the surgical subspecialties, utilization of operative time was then modeled by time after diagnosis. Patients pursuing breast reconstruction had a mean (SD) of 701.5 (317.4) total operative minutes within the first 4 years after diagnosis, including 154.6 (71.3) minutes with breast surgery and 547.0 (305.1) minutes with plastic surgery. Ambulatory cases accounted for 157.2 mean operative minutes per patient (22.3%), outpatient cases accounted for 261.0 mean operative minutes per patient (37.0%), and inpatient cases accounted for 286.3 mean minutes per patient (40.6%). Mean total operative time tended to be higher among patients receiving radiation (781.7 minutes versus 670.3 minutes), and among patients undergoing immediate free flap (899.0 minutes) or TE-to-free flap (973.8 minutes) compared with TE-to-implant reconstruction (547.7 minutes; Table 4). Although the majority of breast surgery operative time was concentrated in year 1 after diagnosis (94.2%), operative time of plastic surgery was dispersed over 3 years (year 1: 53.2%, year 2: 32.8%, year 3: 10.0% total operative time). After multivariate adjustment, independent predictors of total operative time with plastic surgery included pursuit of TE-to-free flap (OR 323.4; 95% CI: 149.5–497.3; P < 0.001) or immediate free flap reconstruction (OR 303.0; 95% CI: 144.6–461.4; P < 0.001), and the occurrence of a major complication during reconstruction (OR 198.5; 95% CI: 82.6–314.4; P = 0.001). Predictors of increased breast surgeon operative time included modified radical mastectomy (compared with simple) (OR 128.9; 95% CI: 26.5–231.3; P = 0.01) and pursuit of a bilateral mastectomy (OR 39.5; 95% CI: 1.8–77.1; P = 0.04; Table 5). Although the majority of breast surgery operative time occurred in the first year after diagnosis, plastic surgeons continued to have substantial (mean >50 minutes per patient) operative time 3 years after the index diagnosis (Figure 3). Most breast surgery operative encounters consisted of outpatient (23 hour stay) cases concentrated in the first year after diagnosis (Figure 4A). Operative volume of plastic surgeons was distributed across ambulatory cases, outpatient cases, and inpatient cases; whereas most plastic surgery ambulatory cases occurred in the first year, volume of both inpatient and ambulatory cases persisted up to 3 years after diagnosis (Figure 4B).

Table 4.

Quantification of Operative Time by Specialty (among Patients Undergoing Breast Reconstruction)

| Total Operative Time | Breast Surgery | Plastic Surgery | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total operative time (min) (mean, SD) | 701.5 (317.4) | 154.6 (71.3) | 547.0 (305.1) |

| Total operative time: year 1 (min) (mean, SD) | 436.4 (271.9) | 145.6 (67.9) | 290.8 (261.6) |

| Total operative time: year 2 (min) (mean, SD) | 185.7 (251.0) | 6.5 (25.9) | 179.2 (243.4) |

| Total operative time: year 3 (min) (mean, SD) | 54.7 (153.5) | 0.1 (1.2) | 54.6 (153.4) |

| Total operative time: year 4 (min) (mean, SD) | 14.4 (60.0) | 0.2 (2.4) | 14.1 (60.0) |

| Total operative time: year 5 (min) (mean, SD) | 10.4 (71.9) | 2.2 (17.5) | 8.3 (60.0) |

| Case classification | |||

| Ambulatory (mean per patient) (min) | 157.2 | 13.5 | 143.7 |

| Outpatient (mean per patient) (min) | 261.0 | 142.1 | 118.9 |

| Inpatient (mean per patient) (min) | 286.3 | 0.0 | 286.3 |

| Breast cancer stage | |||

| Stage 0 | 784.1 (276.7) | 172.3 (49.4) | 611.8 (294.7) |

| Stage I | 614.9 (330.4) | 153.3 (81.5) | 461.6 (286.8) |

| Stage II | 747.3 (290.9) | 162.4 (63.2) | 584.9 (295.1) |

| Stage III | 819.7 (259.4) | 162.3 (84.2) | 657.4 (242.0) |

| Radiation | |||

| No: mean operative time | 670.3 (319.3) | 150.9 (67.7) | 519.4 (305.6) |

| Yes: mean operative time | 781.7 (300.2) | 166.6 (79.7) | 615.2 (291.8) |

| Reconstructive modality | |||

| TE-to-implant | 547.7 (273.5) | 154.7 (74.8) | 393.0 (259.8) |

| TE-to-free flap | 973.8 (222.2) | 133.7 (70.4) | 840.1 (183.8) |

| Free flap | 899.0 (253.9) | 163.2 (67.8) | 735.9 (238.0) |

| Pedicled autologous | 752.5 (41.7) | 189.6 (59.4) | 563.5 (101.1) |

| Mastectomy type | |||

| Nipple sparing | 530.6 (218.2) | 146.5 (45.5) | 384.1 (218.2) |

| Skin sparing | 689.4 (327.5) | 144.1 (84.6) | 545.3 (306.3) |

| Simple | 746.7 (316.7) | 156.4 (70.7) | 592.5 (311.6) |

| Modified radical | 991.3 (234.9) | 245.3 (12.7) | 746.0 (223.1) |

| Length of stay | 2.6 (2.2) | 1.1 (0.4) | 3.1 (2.2) |

Table 5.

Multivariate Linear Regression Model Predicting Surgeon Operative Time

| Breast Surgery Operative Time | Plastic Surgery Operative Time | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | 95% CI | P | Estimate | 95% CI | P | ||

| (Intercept) | 230.4 | (75.2, 385.6) | 0.004 | (Intercept) | 384.0 | (−43.0, 811.1) | 0.077 |

| Overall stage | Overall stage | ||||||

| Stage I | REF | REF | REF | Stage I | REF | REF | REF |

| Stage 0 | 26.0 | (−29.2, 81.1) | 0.351 | Stage 0 | 72.2 | (−96.7, 241.0) | 0.397 |

| Stage II | 7.8 | (−37.5, 53.0) | 0.733 | Stage II | −44.7 | (−172.9, 83.5) | 0.489 |

| Stage III | 3.0 | (−55.7, 61.6) | 0.920 | Stage III | −22.0 | (−204.8, 160.8) | 0.811 |

| Mastectomy type | Reconstruction subtype | ||||||

| Simple | REF | REF | REF | TE−to−Implant | −115.6 | (−272.6, 41.4) | 0.146 |

| Nipple sparing | −37.2 | (−84.8, 10.4) | 0.123 | TE−to−Free Flap | 323.4 | (149.5, 497.3) | <0.001 |

| Skin sparing | −36.1 | (−77.0, 4.7) | 0.082 | Free Flap | 303.0 | (144.6, 461.4) | <0.001 |

| Modified radical | 128.9 | (26.5, 231.3) | 0.014 | Pedicled Flap | 241.6 | (−99.6, 582.7) | 0.162 |

| Major complication of mastectomy | 16.6 | (−58.9, 92.1) | 0.662 | Major complication | 198.5 | (82.6, 314.4) | 0.001 |

| Minor complication of mastectomy | 53.4 | (−8.1, 114.8) | 0.088 | Minor complication | 113.4 | (−16.8, 243.6) | 0.087 |

| Tobacco past | −6.1 | (−48.8, 36.6) | 0.776 | Tobacco past | −20.9 | (−141.6, 99.8) | 0.731 |

| Tobacco current | 27.9 | (−62.3, 118.1) | 0.539 | Tobacco current | −97.1 | (−452.4, 258.2) | 0.587 |

| BMI | −0.3 | (−4.1, 3.4) | 0.858 | BMI | 7.4 | (−3.7, 18.5) | 0.189 |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | −44.0 | (−90.7, 2.6) | 0.064 | Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 33.0 | (−105.6, 171.6) | 0.636 |

| Axillary lymph node dissection | 10.8 | (−23.2, 44.8) | 0.528 | Adjuvant chemotherapy | −40.8 | (−154.1, 72.5) | 0.474 |

| Cancer bilateral | 21.0 | (−40.0, 82.1) | 0.494 | Adjuvant radiation | −40.1 | (−167.3, 87.0) | 0.531 |

| Age | −1.2 | (−3.0, 0.7) | 0.208 | Age | −3.6 | (−8.6, 1.4) | 0.158 |

| Germline genetic mutation | −15.9 | (−91.5, 59.8) | 0.677 | Germline genetic mutation | −84.3 | (−302.1, 133.6) | 0.443 |

| ER+ | −2.8 | (−81.7, 76.1) | 0.944 | ER+ | −6.3 | (−229.2, 216.6) | 0.955 |

| PR+ | −15.0 | (−79.4, 49.4) | 0.643 | PR+ | −51.4 | (−230.8, 127.9) | 0.569 |

| HER2+ | −7.6 | (−58.9, 43.7) | 0.768 | HER2+ | 30.0 | (−118.1, 178.1) | 0.687 |

| Triple negative | −27.6 | (−112.3, 57.2) | 0.519 | Triple negative | 51.0 | (−184.3, 286.4) | 0.667 |

| Mastectomy bilateral | 39.5 | (1.8, 77.1) | 0.040 | Breast reconstruction bilateral | 7.8 | (−95.2, 110.8) | 0.880 |

Fig. 3.

Total operative time per patient by specialty and year after diagnosis (N = 362 operative encounters).

Fig. 4.

Operative time by case classification and year after diagnosis. A, Breast surgery. B, Plastic surgery.

DISCUSSION

In the context of evolving healthcare systems and reimbursement patterns nationally, a comprehensive definition of the effort that breast reconstruction surgeons contribute to breast cancer care becomes essential. Defining the effort of breast reconstruction surgeons enables system-level advocacy for appropriate structuring of payment models for breast cancer and reconstruction care, and also enables institution-level advocacy for appropriate allocation of hospital resources to care for this growing patient population. This study modeled total encounter volume and operative time utilization in the first 4 years after breast cancer diagnosis for patients undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction. We found that patients pursuing breast reconstruction had the highest clinical encounter volume and operative time utilization with plastic surgeons compared with all other specialties, and that this clinical and operative utilization with plastic surgeons persisted up to 3 years after the initial diagnosis of breast cancer. Clinical and operative utilization was tied to treatment characteristics, reconstruction subtype, and incidence of reconstructive complications. Overall, this study highlights the complex and lengthy duration of care that is inherent to breast reconstruction care, data that must be accounted for in future iterations of value-based models and institutional plans for resource allocation within cancer centers.

Across the plastic surgery literature, there is growing evidence that the contributions of plastic surgeons remain largely undervalued within academic medical centers. Downstream, this problem has a myriad of implications within academic centers, including inadequate resource allocation of clinic space, operating room time, and hiring patterns necessary for timely patient care as well as the growth and sustainability of clinical programs. To address this discrepancy, several studies have calculated the profitability of plastic surgeons to the bottom line of major medical centers. In retrospective review of inpatient cases, Vartanian et al found that cases involving a plastic surgeon had a higher overall profit margin, including net revenue margin, contribution margin, and case mix index, compared with cases without a plastic surgeon.2 In addition, in another review of case logs at a large medical center, Wang et al found that plastic surgeons generated over $2 million in save dollars by salvaging complications in a single fiscal year.3 However, generating these save dollars through salvage of complications requires significant time expenditure both in the operating room and clinic, time that is another substantial component of the effort and value that plastic surgeons bring to medical centers. However, to date, the time contribution of plastic surgeons in medical centers has yet to be quantified and accounted for in academic centers.

In this study, we model the encounter volume and operative time utilization of plastic surgeons involved in care of a population of patients undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction. We find that in the first 4 years after breast cancer diagnosis, patients undergoing breast reconstruction have the highest numbers of total encounters and operative minutes with plastic surgeons compared with all other breast-cancer–related specialties. In addition, the time distribution of both encounter and operative volume varied significantly by specialty across the cohort. While encounter volume of breast surgeons was concentrated within 90 days of diagnosis (quarter one) and radiation oncologists was also concentrated in a 90-day period (quarter three), encounter volumes of both medical oncologists and plastic surgeons were sustained up to three years after diagnosis. Furthermore, operative time utilization of plastic surgeons persisted throughout years two and three after diagnosis, with over half of plastic surgery operative time utilization occurring after year one.

Broadly, these data may inform institution-level resource allocation of clinic space and operating room time within academic centers. Based on this study, each patient with a new diagnosis of breast cancer who elects to pursue postmastectomy reconstruction will require an average of 46 clinical encounters across breast cancer providers, including 17 clinical encounters with plastic surgeons and nearly 550 operative minutes for breast reconstruction. As the population of breast cancer patients seeking reconstruction grows,7,8 the popularity of prophylactic reconstructive surgery rises,7,11 and the established long-term benefits of autologous reconstruction shift referral patterns toward tertiary academic centers,12,13 the necessary resources to care for a population of breast cancer patients at academic centers will continue to increase. This study highlights the substantial clinical encounter effort and time that is necessary from plastic surgeons through completion of the process of breast reconstruction. The well-established increasing rates of breast reconstruction nationally and the significant effort required for breast reconstruction captured herein necessitate appropriate resource allocation to meet this need. This allocation is necessary not only to appropriately account for provider value and effort, but also to enable timely access to breast reconstruction in line with the tenants of the Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act.14

In addition, these data may inform the structure of future iterations of value-based payment models in breast cancer care. In the context of ongoing consideration of payment reform in the United States, increasing efforts have been placed recently on generating estimates of value in breast cancer and reconstruction care.1,15,16 However, the contribution of adjuvant therapies and complications to the treatment durations and the numerous discrete pathways available to patients pursuing reconstruction underlie the challenge of defining episode durations, or the total time period required for breast cancer-related care, for breast reconstruction patients. Prior studies have utilized the Marketscan claims database to study distribution of costs after breast reconstruction, finding that a 1-year time horizon captured most costs related to reconstruction events, revisions, and complications.15 In this study, comorbidities, complications, and adjuvant therapies all contributed to total cost incurred during reconstruction.15 However, other institutional studies have found that time to completion of reconstruction varies from 10 to 40 months, with duration varying based on reconstruction subtype, treatment factors (including tamoxifen use), and pursuit of revisions.17 In this study, we also identify a lengthy duration of care required to capture all events to completion of breast reconstruction, with a significant proportion of both encounter effort and operative time with plastic surgeons occurring after a 1-year time horizon in the second and third years after a breast cancer diagnosis. In this cohort, encounter volumes varied based on receipt of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, adjuvant radiation, and occurrence of major complications during reconstruction. These findings underscore the importance of adjustment for adjuvant therapies and complications in future bundled payment models. These data also suggest that a lengthier duration of care may be needed for breast reconstruction to adequately capture all events from initial surgery to completion of revisions, such that these models adequately enable timely access to all phases of breast reconstruction for all patients.

This study has limitations with implications for its interpretation. First and foremost, our sample is representative of the patient population and multidisciplinary practice patterns at a single academic cancer center, which may not be representative of the patient populations or treatment plans involved in other centers across the country. Comparisons of raw encounter volume may underestimate encounter complexity. For example, estimates of clinical encounter volume do not measure the actual time spent during encounters as would be performed in a time-driven activity-based costing study, and therefore cannot estimate associations between time and costs incurred throughout phases of breast cancer care. However, this study aimed to emphasize the (1) lengthy episode duration and (2) complexity and variability of treatment pathways involved in care of breast reconstruction patients. These data highlight the complexity and duration of provider effort required for postmastectomy breast reconstruction, data that may enable advocacy for the institutional and system-wide value of plastic surgeons in comprehensive breast cancer care.

CONCLUSIONS

In a longitudinal assessment of clinical and operative encounter volume, patients undergoing postmastectomy breast reconstruction had the highest numbers of total encounters and operative minutes with plastic surgeons compared with all other breast cancer–related specialties. Although clinical encounter volume of breast surgeons and radiation oncologists was concentrated in the first year after diagnosis, encounter volume of plastic surgeons and medical oncologists persisted up to 3 years after diagnosis. Clinical encounter volume varied by receipt of adjuvant therapy and incidence of reconstruction complications, and total operative time was associated with reconstructive subtype. Overall, this study emphasizes the quantity and duration of clinical encounter and operative effort required by plastic surgeons to care for patients undergoing breast reconstruction, data that must be accounted for in future iterations of value-based models and institution-level models for resource allocation within academic centers.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Published online 12 December 2022.

Disclosure: The authors have no financial interest to declare in relation to the content of this article.

Related Digital Media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSGlobalOpen.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sheckter CC, Matros E, Lee GK, et al. Applying a value-based care framework to post-mastectomy reconstruction. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2019;175(3):547–551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vartanian ED, Ebner PJ, Liu A, et al. Reconstructive surgeons as essential operative consultants: quantifying the true value of plastic surgeons to an academic medical center. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;149:767e–773e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TY, Nelson JA, Corrigan D, et al. Contribution of plastic surgery to a health care system: our economic value to hospital profitability. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:154e–160e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Santosa KB, Qi J, Kim HM, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg 2018;153:891–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson JA, Allen RJ, Jr, Polanco T, et al. Long-term patient-reported outcomes following postmastectomy breast reconstruction: an 8-year examination of 3268 patients. Ann Surg. 2019;270:473–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mundy LR, Rosenberger LH, Rushing CN, et al. The evolution of breast satisfaction and well-being after breast cancer: a propensity-matched comparison to the norm. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;145:595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Panchal H, Matros E. Current trends in postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140(5S Advances in Breast Reconstruction):7S–13S. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jagsi R, Jiang J, Momoh AO, et al. Trends and variation in use of breast reconstruction in patients with breast cancer undergoing mastectomy in the United States. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:919–926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Plastic surgery statistics report. American Society of Plastic Surgeons; 2020. Available at https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf. Accessed March 29, 2022.

- 10.Chen Z, Xu L, Shi W, et al. Trends of female and male breast cancer incidence at the global, regional, and national levels, 1990–2017. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180:481–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baskin AS, Wang T, Bredbeck BC, et al. Trends in contralateral prophylactic mastectomy utilization for small unilateral breast cancer. J Surg Res. 2021;262:71–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matros E, Yueh JH, Bar-Meir ED, et al. Sociodemographics, referral patterns, and Internet use for decision-making in microsurgical breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1087–1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yueh JH, Slavin SA, Bar-Meir ED, et al. Impact of regional referral centers for microsurgical breast reconstruction: the New England perforator flap program experience. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208:246–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.United States. Congress. Senate. Committee on Finance. Subcommittee on Health Care. Women’s Health and Cancer Rights Act of 1997: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Health Care of the Committee on Finance, United States Senate, One Hundred Fifth Congress, first session, on S. 249, November 5, 1997. Washington: U.S.G.P.O.: For sale by the U.S. G.P.O., Supt. of Docs., Congressional Sales Office; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berlin NL, Chung KC, Matros E, et al. The costs of breast reconstruction and implications for episode-based bundled payment models. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2020;146:721e–730e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sheckter CC, Razdan SN, Disa JJ, et al. Conceptual considerations for payment bundling in breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:294–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ticha P, Wu M, Mestak O, et al. Evaluation of the number of follow-up surgical procedures and time required for delayed breast reconstruction by clinical risk factors, type of oncological therapy, and reconstruction approach. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2022;46:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.