Abstract

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) has been used as a core therapy for treating dysbiosis-related diseases by remodeling gut microbiota. The methodology and technology for improving FMT are stepping forward, mainly including washed microbiota transplantation (WMT), colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) for microbiota delivery, and purified Firmicutes spores from fecal matter. To improve the understanding of the clinical applications of FMT, we performed a systematic literature review on FMT published from 2011 to 2021. Here, we provided an overview of the reported clinical benefits of FMT, the methodology of processing FMT, the strategy of using FMT, and the regulations on FMT from a global perspective. A total of 782 studies were included for the final analysis. The present review profiled the effectiveness from all clinical FMT uses in 85 specific diseases as eight categories, including infections, gut diseases, microbiota–gut–liver axis, microbiota–gut–brain axis, metabolic diseases, oncology, hematological diseases, and other diseases. Although many further controlled trials will be needed, the dramatic increasing reports have shown the promising future of FMT for dysbiosis-related diseases in the gut or beyond the gut.

Keywords: Fecal microbiota transplant, Washed microbiota transplantation, Transendoscopic enteral tube, Spore, Clostridioides difficile, Methodology, Microbiota–gut–brain axis

Introduction

Humans have applied human fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) to treat diseases for thousands of years in China.[1,2] In ancient China (AD 300–400 years), Hong Ge as a doctor of traditional Chinese medicine described the details on using fecal suspension for the treatment of the serious conditions, such as food poisoning and fever.[1,2] The ancient medical record of human FMT was confirmed by the following criteria[2]: (1) the delivered materials are from human feces; (2) the administration route is the digestive tract; (3) the efficacy is caused by microbiota from the fresh fecal water or fermented fecal matter according to the modern medicine; (4) the recorded prescription, methods, indications, and efficacy in ancient literature are clear enough to be identified. Importantly, FMT has been used for refractory diseases by some elder-generation physicians in recent decades in China, indicating the sustained long tradition of using FMT from ancient to modern China.[2]

The emerging refractory antibiotics related resistance in the post-antibiotics era has led physicians and scientists to revalue the role of FMT in modern medicine.[3] FMT was reported as a highly effective treatment for pseudomembranous enterocolitis by Eiseman et al[4] in 1958. The Clostridioides difficile infection (CDI) was later identified as the main pathogen of pseudomembranous colitis. Then, FMT as a well-established treatment for recurrent CDI has experienced a renaissance in recent years with great attention worldwide.[5] In the last decade, a series of pilot studies on FMT, in conditions such as ulcerative colitis (UC), Crohn's disease (CD), epilepsy, autism, and recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs), have revealed the potential effectiveness of FMT beyond CDI.[6–13] In addition, the improved FMT methodology based on automated purification and washing process was named washed microbiota transplantation (WMT), which changed the preparation of fecal microbiota and the safety of transplantation.[14,15] However, a complete understanding on how FMT cures or improves the patients and a general review of all FMT-treated diseases have not been undertaken.

We recently reviewed the global data on the safety of FMT from 2000 to 2020.[16] FMT-related adverse events (AEs) were observed in 19% of FMT procedures with the most frequently reported FMT-related AEs being diarrhea (10%) and abdominal discomfort/pain/cramping (7%). FMT-related serious adverse events (SAEs), including infections and deaths, have been reported in 1.4% of patients who underwent FMT (0.99% microbiota-related SAEs). All reported FMT-related SAEs were in patients with mucosal barrier injury. In this review, we aimed to summarize the effectiveness of FMT for all conditions from 2011 to 2021, and discussed important medical progress of FMT from the perspective of medical history. The present review will assist physicians, researchers, patients, and health providers in general to arrive at a comprehensive understanding on FMT.

Methods

Our search terms were applied to medical publications and databases from EMBASE, MEDLINE, CNKI (database in Chinese), and Wanfang Data from (database in Chinese) January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2021. The search terms were derived from our previously published study.[16] The inclusion criteria included: (1) studies referencing FMT for human subjects showing benefits with no limitation of age and gender; (2) article type: original full-text article, meeting abstracts, and letters to the editor on the clinical studies; (3) reports in English or Chinese. Exclusion criteria included: (1) duplicated reports; (2) non-original reports such as commentary, consensus, reviews, and meta-analysis; (3) publications in Chinese reporting on the same patients in an English article. The reports on pilot case study, high-quality real-world cohort study, and randomized controlled clinical trial (RCT) were cited and discussed.

Global Trend in the Benefits of FMT

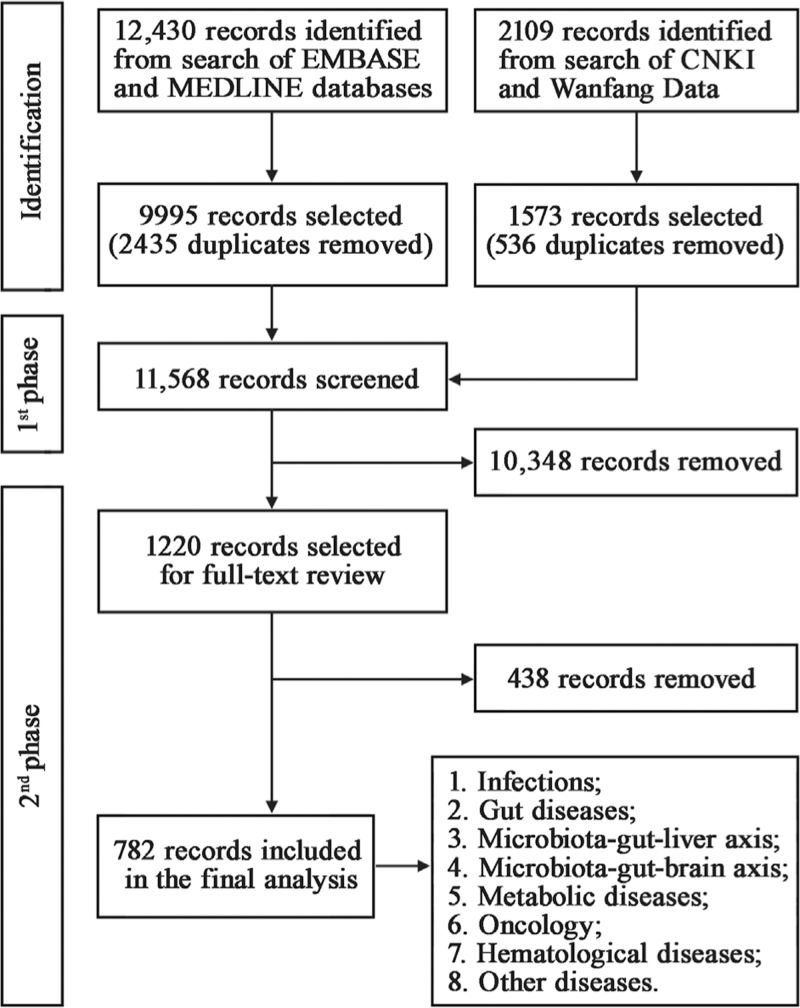

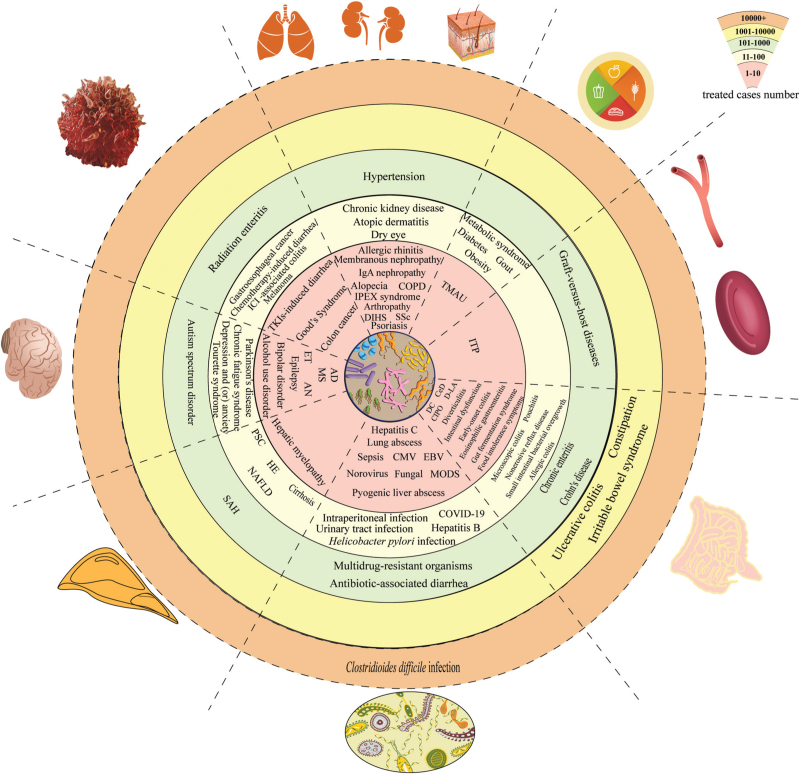

A total of 14,539 records were identified in the search. After the exclusion, removal of duplication, screening and reviewing of full-text articles, we selected 782 searched studies for analysis in this review [Figure 1]. We divided all studies into eight main categories: infections, gut diseases, microbiota–gut–liver axis, microbiota–gut–brain axis, metabolic diseases, oncology, hematological diseases, and other diseases. Each category was further subdivided into specific diseases. A total of 85 diseases were shown in Figure 2. The number of treated cases using FMT for each disease were clarified as the following level: 1–10, 11–100, 101–1000, 1001–10,000, 10,000+. The baseline characteristics and main findings of high-quality clinical research (defined as any randomized clinical trial or any study with sample size ≥100 or the largest study on each disease with sample size ≥5) on the benefits of FMT were shown in Supplementary Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

Figure 2.

Benefits from human FMT. AD: Alzheimer's disease; AN: Anorexia nervosa; CeD: Celiac disease; CIPO: Chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction; CMV: Cytomegalovirus; COPD: Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; COVID-19: Coronavirus disease 2019; DC: Diversion colitis; Ig A: Immunoglobulin A; DIHS: Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome; D-LA: D-lactic acidosis; EBV: Epstein–Barr virus; ET: Essential tremor; FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation; HE: Hepatic encephalopathy; ICI: Immune checkpoint inhibitor; IPEX syndrome: Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome; ITP: Immune thrombocytopenia; MODS: Multiple organ dysfunction syndrome; MS: Multiple sclerosis; NAFLD: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease; PSC: Primary sclerosing cholangitis; SAH: Severe alcoholic hepatitis; SSc: Systemic sclerosis; TKI: Tyrosine kinase inhibitor; TMAU: Trimethylaminuria.

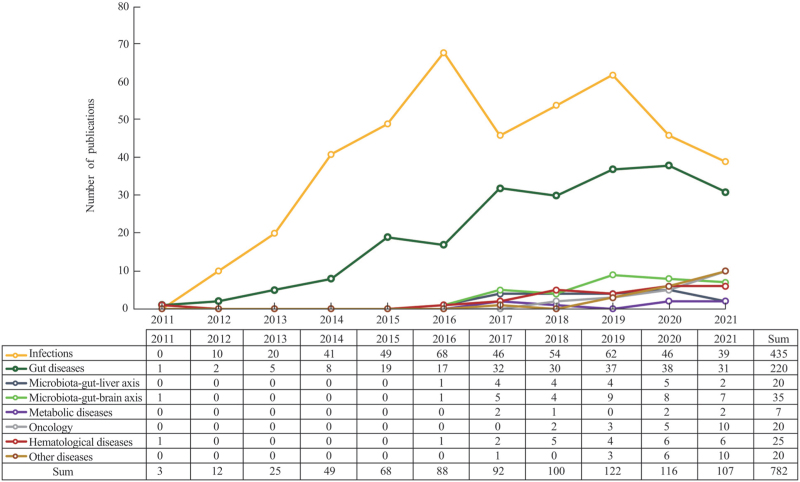

The global trend in the benefits from FMT was shown in Figure 3. The uses of FMT for infections and gut diseases were the most widely documented, followed by neuropsychological, hematological, and liver diseases.

Figure 3.

Global trend in the benefits from FMT. FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation.

Benefits from FMT

FMT and infections

Bacterial infections

CDI

From 2011 to 2021, a total of over 10,000 patients with CDI have benefited from FMT globally. In 1983, Schwan et al[17] documented the first cure of CDI by rectal infusion of feces using the patient's partner as a donor. Later in 2013, the first RCT by van Nood et al[18] reported the infusion of donor feces was significantly more effective for the treatment of recurrent CDI than vancomycin. FMT has been expanded to treat CDI in the children, the elderly, and pregnant patients.[19–21] In the most recent studies from Europe and Australia, the use of antibiotics as a pre-treatment has been unhelpful in most cases, highlighting the superiority of FMT treatments as an initial primary therapy.[22]

Occasionally, CDI occurred with other diseases. Meighani et al[23] found that the response to FMT and the rate of CDI relapse in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) were not statistically different compared to the rest of the cohort. A retrospective study found that overall cure rate of FMT for CDI was 91.3% at 3 months in solid organ transplantation patients.[24] Notably, Elopre and Rodriguez[25] reported two cases of treating recurrent CDI in human immunodeficiency virus-infected individuals with FMT.

Multidrug-resistant organisms (MDROs)

Recently, at least 100 patients suffering from MDRO infection have benefited from FMT. In 2015, Crum-Cianflone et al[26] reported a case in which FMT utilized for relapsing CDI successfully eradicated colonization with several MDROs. According to Lee et al's[27] study, overall negative conversion of MDROs within 1 month (40% vs. 0%) and 3 months (28.6% vs. 11.1%) was significantly different between FMT and control groups.

UTIs

In a retrospective case-control study, there was a significant decrease in the frequency of UTIs, from a median of 4 (range 3–7) episodes in the year before to 1 (0–4) episodes in the year after FMT.[28] Biehl et al[13] also reported on a kidney transplant recipient successfully treated with FMT for recurrent UTI.

Antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD)

More than 100 patients with AAD were reported to have been treated with FMT. Dai et al[29] reported that 2/2 patients with abdominal pain, 13/15 of diarrhea, 9/13 of abdominal distention, and 1/2 of hematochezia improved after FMT.

Other bacterial infections

In 2013, Zhang et al[30] first reported the successful treatment using a standardized FMT for a case of refractory CD complicated with intraperitoneal fistula. Moreover, a prospective study demonstrated that the overall eradication rate of Helicobacter pylori was 40.6% (13/32) by WMT.[31] FMT also showed its efficacy in some extraintestinal infections such as pyogenic liver abscess, sepsis, and multiple organ dysfunction syndrome.[32–34]

Viral infections

Hepatitis B

It is reported that >100 hepatitis B carriers had undergone FMT. In 2017, a clinical trial showed that in the FMT arm, all participants (3/3) achieved HBeAg clearance while none in the control arm did.[35] Chauhan et al[36] reported similar results. An open-label RCT demonstrated that FMT with tenofovir is superior to tenofovir alone in improving clinical outcomes in acute-on-chronic liver failure due to hepatitis B.[37]

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)

According to a case report, two patients diagnosed with COVID-19 showed negative severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) polymerase chain reaction (PCR) stool testing 1 month after FMT.[38]

Other viral infections

FMT appeared to be efficacious in norovirus infection and cytomegalovirus colitis.[39,40]

Fungal infection

In one Chinese patient with UC and recurrent invasive infection of Candida glabrata, inflammatory markers rapidly decreased after WMT via colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing (TET) within 1 week and repeated fecal fungal culture tests were negative during hospitalization and follow-up.[41]

FMT and gut diseases

UC

Perhaps the earliest FMT carried out in 1988 treated UC successfully in one patient with over 20-year remission.[42] Borody et al[43] showed that 67.7% of UC patients (42/62) achieved complete clinical remission after FMT, and 24.2% of patients (15/62) achieved partial responses. Later in a randomized trial, his group showed FMT effectiveness in 27% vs. 8% in placebo.[44] Costello et al's[8] RCT demonstrated that steroid-free remission was achieved in 12 of the 38 participants (32%) receiving pooled donor FMT compared with 3 of the 35 (9%) receiving autologous FMT. A recent double-blind RCT showed that repeated FMTs could induce and maintain clinical, endoscopic, and histologic remission in four (100%) UC patients.[45] More than 1000 patients with UC have been treated with FMT globally between 2011 and 2021.

CD

Over 100 CD patients have benefited from FMT since the first successful case report of FMT in CD was published in 1989.[42] In 2013, Zhang et al[30] reported a patient with severe CD successfully treated using mid-gut FMT. In a retrospective study, the rate of clinical improvement and remission of CD at the first month after FMT was 86.7% (26/30) and 76.7% (23/30), respectively.[9] According to Xiang et al's[10] study, 72.7% (101/139), 61.6% (90/146), 76% (19/25), and 70.6% (12/17) of CD patients achieved improvement in abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and fever, respectively, at 1 month after FMT. An RCT also showed that the steroid-free clinical remission rate at 10 weeks and 24 weeks was 44.4% (4/9) and 33.3% (3/9) in the placebo group while 87.5% (7/8) and 50.0% (4/8) in FMT group.[46]

Constipation

As early as 1989, a case with chronic constipation showed improvement after bowel-flora alteration.[42] In total, over 1000 patients with slow transit constipation (STC) underwent FMT globally from 2011 to 2021. Tian et al[47] carried out a randomized controlled trial, where FMT was significantly more effective (30% higher cure rate) for treatment of STC than conventional treatment.

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Almost 1000 patients with IBS have been treated with FMT. In Pinn et al's[48] study, 70% of the patients with IBS experienced resolution or improvement of symptoms after FMT. A double-blind RCT found that 36 of 55 (65%) participants receiving FMT vs. 12 of 28 (43%) receiving the placebo showed a response at 3 months.[49] Another clinical trial also confirmed the efficacy of FMT for patients with IBS.[50]

Pouchitis

In 2016, Fang et al[51] reported successful treatment of chronic pouchitis utilizing FMT. According to Stallmach et al's[52] report, symptoms of chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis were resolved in four of five patients within 4 weeks after the last FMT. A pilot study showed that four of nine patients receiving FMT were in clinical remission at 30-day follow-up, and three patients remained in remission until a 6-month follow-up.[53]

Other gut diseases

In 2014, FMT was first utilized in treating eosinophilic gastroenteritis and achieved a positive clinical response.[54] According to a pilot study, symptoms of allergic colitis in 17 infants were relieved within 2 days of FMT, and no relapse was observed in the next 15 months.[55] Clancy and Borody[56] also showed that FMT could alleviate food intolerance symptoms. Several studies reported that the symptoms of diversion colitis improved after FMT.[57,58] It is also reported that FMT had a positive therapeutic effect in treating microscopic colitis, collagenous colitis, and recurrent diverticulitis.[59–61] Zheng et al[62] reported that WMT reduced proton pump inhibitor dependency in non-erosive reflux disease.

In a case report, full recovery of duodenal villi and clinical symptoms of celiac disease after FMT was reported.[63] Gastrointestinal symptoms of small intestinal bacterial overgrowth significantly improved after FMT in some reports.[64,65] FMT had also been reported in effectively treating chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction, gut fermentation syndrome, and D-lactic acidosis.[66–68]

FMT and the microbiota–gut–liver axis

Hepatic encephalopathy (HE)

In 2016, Kao et al[69] reported that the symptoms and examination indicators were improved in a patient with HE after receiving five weekly FMTs. One RCT showed that no FMT participant developed further HE whereas five patients in the standard of care group developed further HE.[70] According to Mehta et al's[71] report, six patients with HE experienced sustained clinical response with single FMT treatment at post-treatment week 20.

Severe alcoholic hepatitis (SAH)

At least 100 SAH patients had received FMT recently. In 2017, Philips et al[72] reported a steroid non-responder with SAH discharged home on the 10th day after FMT. In their following studies, they found that bilirubin, Child–Turcotte–Pugh (CTP), and Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) and MELD-sodium scores decreased significantly in the FMT group compared to the historical controls group.[73] FMT showed a better outcome compared to steroid therapy for 90-day survival in SAH.[74]

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Allogenic FMT in patients with NAFLD/metabolic dysfunction-associated fatty liver disease (MAFLD) was reported to help improve abnormal small intestinal permeability.[75] In addition, Witjes et al[76] observed a trend toward improved necro-inflammatory histology, and significant changes in the expression of hepatic genes involved in inflammation and lipid metabolism following allogenic FMT.

Cirrhosis

It was reported that FMT had improved CTP scores and led to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines.[77] A significant reduction was observed in plasma ammonia at day 30 post-FMT, with a trend toward an increase in ammonia in the placebo group.[78]

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC)

A case with PSC was afebrile and anicteric after the third and fourth session of FMT, respectively, and remained so up to 1 year.[79] In a prospective study, three PSC patients experienced a ≥50% decrease in alkaline phosphatase (ALP) levels after FMT.[80]

Hepatic myelopathy

According to Sun et al's[81] report, the muscle strength of both legs in a case diagnosed with hepatic myelopathy was increased at various degrees after three FMTs.

FMT and the microbiota–gut–brain axis

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD)

It has been reported that over 100 cases with ASD had undergone FMT therapy from 2011 to 2021. Ward et al[82] found that ASD symptoms were markedly improved in half of the 8-year-old subjects. According to Kang et al's[12,83] study, behavioral ASD symptoms improved significantly and persisted 8 weeks and autism-related symptoms improved even more at a 2-year follow-up after FMT stopped.

Parkinson's disease (PD)

A case with PD successfully maintained daily unobstructed defecation until the end of follow-up and the tremor in the legs almost disappeared 1 week after FMT.[84] Another study also reported motor, non-motor, and constipation scores were improved in 5/6 patients 4 weeks following the FMT.[85]

Psychiatric disorders

Several studies reported that depression and anxiety symptoms in IBS patients were improved by FMT.[86,87] In a case report, the patient with mental depression felt less sleepy, had a better appetite, and became more talkative and euphoric after FMT.[88] Another case report also demonstrated the benefits of FMT in a patient with bipolar disorder.[89] In addition, a few patients with alcohol use disorder and anorexia nervosa achieved some improvements from FMT.[90,91]

Other neurological disorders

He et al[11] firstly reported that the patient had no recurrence of epilepsy during the entire 20 months of follow-up after FMT in treating CD. Gunaratne et al[92] also found that FMT reduced seizures. Moreover, several case studies reported improvement in Alzheimer's disease symptoms following FMT.[93,94] FMT also showed its efficacy in chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, essential tremor, and Tourette syndrome.[95–98]

FMT and metabolic diseases

Diabetes

In 2018, Cai et al[99] firstly reported that the glycemic control was improved, with remarkable relief of the symptoms of painful diabetic neuropathy in particular after two infusions of FMTs. According to a prospective study, the insulin dose of the patients with brittle diabetes began to decrease from 1 week post-WMT, with the most significant decrease at 1 month post-WMT.[100] One RCT also demonstrated that FMT halted a decline in endogenous insulin production in recently diagnosed patients with type 1 diabetes in 12 months after disease onset.[101]

Obesity

In a retrospective study, the mean body mass index (BMI) of all the patients pre-transplant was 28.9 kg/m2, and the mean BMI of all the patients 1–3 months post-FMT was 27.4 kg/m2.[102]

Metabolic syndrome

Allegretti et al[103] observed a significant change in glucose area under the curve (AUC) at week 12, and in the insulin AUC at week 6 in the FMT group compared to placebo.

Other metabolic diseases

A recent prospective study has proven that WMT was effective in reducing serum uric acid levels and improving gout symptoms in gout patients.[104] FMT has shown its efficacy in trimethylaminuria.[64]

FMT and oncology

Tumor

In a prospective study, FMT together with anti-programmed cell death protein-1 (anti-PD-1) provided clinical benefit in 6 of 15 melanoma patients.[105] Baruch et al[106] also found that FMT promoted response in immunotherapy–refractory melanoma patients. Moreover, an RCT showed that FMT from overweight or obese donors in cachectic patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer could help to improve disease control rate at 12 weeks compared with the autologous group.[107] The improvement of Good's syndrome by FMT was observed in one case.[108]

Radiation enteritis (RE)

Ding et al[109] for the first time reported that FMT brought the possibility to cure chronic refractory RE. WMT has been used a regular therapy for RE in few WMT centers in China. Patients with RE benefited from WMT with the improvement in diarrhea, rectal hemorrhage, abdominal/rectal pain, and fecal incontinence. The ongoing trials on WMT will essentially change the clinical management of RE.

Drug-associated colitis

Over 10 cases suffering from complications related to antitumor drugs have received FMT. FMT was utilized for the first time in immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis and achieved encouraging results according to Wang et al's[110] report in 2018. Their subsequent study showed that endoscopic remission was achieved in 64% of the 11 patients who responded to FMT 4–8 weeks after FMT.[111] FMT also showed its efficacy in the treatment of diarrhea induced by tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma.[112]

FMT and hematological diseases

Graft-versus-host diseases (GVHD)

It has been reported that over 100 patients with GVHD had benefited from FMT. Kakihana et al[113] conducted a pilot study in which all acute GVHD patients responded to FMT, with three complete responses and one partial response. Moreover, a pilot study by Qi et al[114] showed that compared to those who did not receive FMT, patients achieved a higher progression-free survival after FMT. In an RCT study, more patients achieved clinical remission in the FMT group than in the control on days 14 and 21 after FMT.[115]

Other hematological diseases

In 2011, Borody et al[116] first reported a “cure” of the concomitant immune thrombocytopenia in a patient being treated with FMT for UC.

FMT and other diseases

FMT and skin diseases

Rebello et al[117] reported incidental benefits of hair growth in two alopecia patients after FMT. Huang et al[118] reported clinical efficacy of FMT treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis.

FMT and kidney diseases

Alleviation of refractory IgA nephropathy by intensive FMT was reported by Zhao et al[119]. In an RCT, the patients who received FMT had less progression of chronic kidney disease at 6 months.[120]

FMT and immune disorders

A recent RCT demonstrated that FMT reduced lower gastrointestinal symptoms of systemic sclerosis.[121] One study reported resolution of the symptoms of allergic rhinitis and drug withdrawal of anti-histaminic drugs after seven sessions of FMT for UC.[122] Dramatic improvement was reported in drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome after FMT.[123]

FMT and arthropathy

In a case report, FMT for CDI resulted in a decrease in psoriatic arthritis disease activity.[124] Zeng et al[125] showed that the disease activity index of rheumatoid arthritis dropped after FMT. A patient with axial arthritis also reported relief in his back pain and a reduction in morning stiffness after FMT.[122]

FMT and other diseases

The blood pressure-lowering effect by WMT was observed in hypertensive patients, especially in those who underwent WMT via the lower gastrointestinal tract and in those not taking antihypertensive drugs.[126] One patient with the chronic obstructive pulmonary disease was significantly relieved from the respiratory symptoms after WMT.[127] In a prospective study, five individuals subjectively reported improved dry eye symptoms 3 months after FMT.[128] Wu et al[129] reported that the patient with immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked (IPEX) syndrome responded with remission of diarrhea after receiving FMT.

Methodology of FMT

Donor screening

Selecting an appropriate donor is vital to the success of FMT. Donors for FMT can be divided into two types, allogeneic donors and autologous donors, according to the source of fecal matter.[130] The allogeneic source is more commonly adopted than an autologous source because it can meet the requirement for one-to-many treatments.[130] Moreover, it has demonstrated improved efficacy compared with an autologous source.[130]

The strategy of screening healthy donors for FMT is the concept of exclusive methods. However, the recommended protocols varied among different guideline or consensus.[131,132] The exclusion criteria for screening allogeneic donors can be listed into eight dimensions: age, physiology, pathology, psychology, veracity, time, living environment, and recipients. The guidance on donor screening of WMT, including questionnaire screening, interview screening, laboratory screening and monitoring screening, was coined in Nanjing consensus on WMT in 2019.[15]

During the pandemic of SARS-CoV-2, specific recommendations have been released to reorganize the workflow of FMT to avoid the potential risk of the virus transmission through the FMT procedure.[133] Briefly, these recommendations included the use of remote assessment of patients and donors whenever possible, the expansion of donor screening with questionnaires and laboratory testing aimed at excluding SARS-CoV-2 infection, and the application of specific safety measures during the endoscopic FMT procedure.

Preparation of fecal microbiota

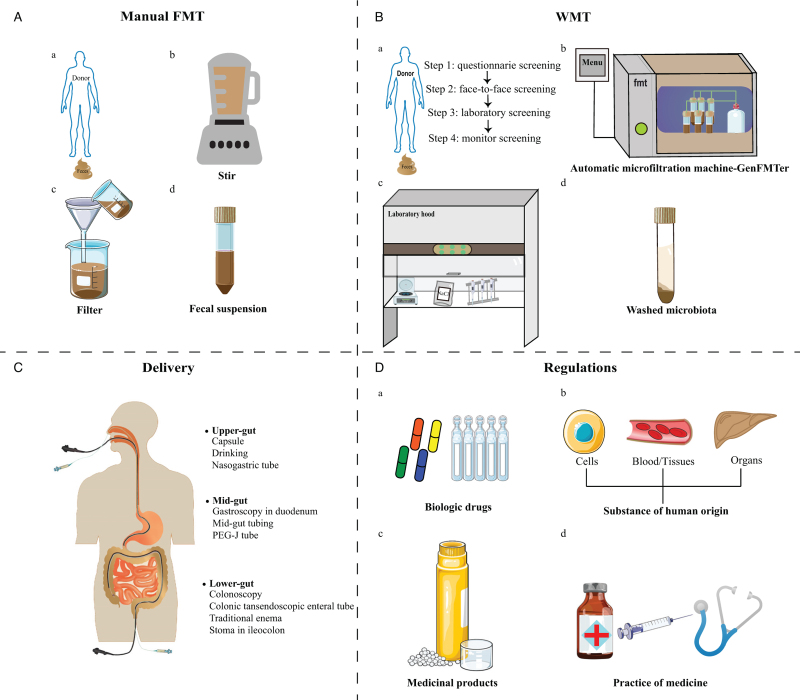

The methods of laboratory preparation for FMT reported in the literature can be classified into manual FMT and WMT. The preparation of manual FMT was shown in Figure 4A. The dosage for delivering FMT mainly depends on the fecal weight, instead of the precise volume or amount of microbiota.[131]

Figure 4.

Methodology and regulations of FMT. (A) Manual preparation of fecal microbiota; (B) the process of WMT; (C) delivery of FMT/WMT; (D) the regulation policy of FMT/WMT. FMT: Fecal microbiota transplantation; PEG-J: Percutaneous endoscopic gastrojejunostomy; WMT: Washed microbiota transplantation.

A newly improved methodology for FMT coined WMT is based on the automatic purification and washing process [Figure 4B].[14] This method, originally designed on the concept of washed microbiota preparation, is based on the automatic microfiltration machine (GenFMTer, FMT Medical, Nanjing, China) and the following repeated centrifugation plus suspension with support from specific facilities.[14,16] WMT has been used by multiple FMT centers in China since 2014.[6,31,62,134] This progressive method permits the delivery of a precise dose of microbiota more possible.[15]

Routes of delivering

The delivery methods for FMT/WMT can be grouped into the upper-gut, mid-gut, and lower-gut [Figure 4C].[2,15,44,135] Gastroscopic-guided fecal transplants, as well as microbiota capsules, are direct ways to transplant into the upper-gut. Gastroscopic transplants can be guided as far as the small intestine beyond the second duodenal segment, defined as the mid-gut, via endoscopy, nasojejunal tube, mid-gut TET, small intestine stoma or percutaneous endoscopic gastro-jejunostomy (PEG-J). FMT can be also delivered to the lower-gut through colonoscopy, enema, distal ileum stoma, colostomy, and colonic TET. Among all delivering methods, colonic TET is perhaps the safest with the lowest rate of delivery-related AEs according to a recent systematic review.[16]

Colonic TET is the latest progress on FMT delivery. It was proven to be a safe and convenient procedure for multiple FMTs and colonic medication administration for patients aged over 7 years old.[136] According to a survey, patients who had undergone FMT by TET were more likely to recommend FMT than patients who had not.[137] Zhong et al[138] also reported that colonic TET was a safe and convenient delivery method in children aged 3–7 years.

Treatment strategy using FMT

In 2015, Cui et al[6] proposed a step-up FMT strategy for the steroid-dependent UC. Their pilot study demonstrated that 8 of 14 (57.1%) patients achieved clinical improvement and were able to discontinue steroids following step-up FMT.[6] The step-up FMT strategy consists of three parts: step 1 refers to single FMT; step 2 refers to multi-FMTs (≥2); step 3 refers to the FMT combined with regular medication (such as steroids, cyclosporine, anti-tumor necrosis factor-α (anti-TNF-α) antibody, or exclusive enteral nutrition) after the failure of step 1 or step 2.[2,139] This step-up FMT strategy can be considered for patients with refractory/severe infectious and immune-related diseases, especially when patients do not respond to single/multiple FMTs.

Increasing typical studies highlighted the necessity to formulate a treatment ladder with step 1, step 2, and step 3. In 2016, Kakihana et al[113] reported multiple FMTs with steroids improved acute GVHD. In 2017, Fischer et al[140] reported that sequential FMTs with interval antibiotics improved the outcome of treatment for patients with severe or severe-complicated CDI. In 2019, Ding et al[7] reported that 74.3% (81/109) and 51.4% (56/109) of UC patients achieved clinical response at 1 month and 3 months after step-up FMT, respectively.

Regulatory agencies and FMT

The regulations on FMT vary from country or area worldwide. Overall, FMT can be placed into four categories: biological drug, human cell or tissue-based product, medicinal product, or practice of medicine [Figure 4D].[15,141] Unfortunately, classification by national agencies has a significant impact on the direct availability of FMT products for patients. The main benefit of the biological regulatory paradigm is guaranteeing the safety and efficacy of FMT in any given disease. From Kragsnaes et al's[142] view, a centralized, non-profit, blood and tissue transplant service was an ideal model to run a stool bank of high-quality FMT products and provide equivalent accessibility. Keller et al[143] suggested that stool for FMT be classified as a transplant product and not as a drug. Australia and Switzerland's regulatory bodies have classified FMT as an investigational medicinal product, making FMT more widely accessible to patients.[141] Regulatory authorities may choose to regulate stool under the discretion of the practicing doctor. Under this approach, all decisions relating to donor screening, material processing, and potentially decisions related to indication usage, are delegated to each patient's doctor and their doctor's supervisory institution.[141] The policy on the use of FMT in China is the permitted medical therapy for CDI and many other diseases.[144]

Although the treatment utility of FMT is generally on the rise, barriers remain to patient accessibility bolstered by complex regulatory affairs across jurisdictions. Concurrent international standardization in Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP) manufacturing for FMT products could also support the effectiveness and safety standards for FMT in line with other biological therapies and thus accelerate adoption in lagging countries.

Future Direction

The significance of the present review is to provide a comprehensive picture of many diseases with only small samples, for improving better understanding of FMT in the future. FMT has gained the great attention in the past decade in the world. All of those FMT-treated diseases can be named dysbiosis-related diseases, which essentially consist of three types of inflammation, including acute inflammation (CDI, etc.), chronic inflammation (chronic UC and CD, etc.), and chronic low-grade inflammation (type 2 diabetes, NAFLD, obesity, etc.). Accumulating studies have provided evidence for understanding the logic on treating CDI, UC, and CD by targeting gut microbiota.[15,145] However, the treatment using FMT for chronic low-grade inflammation needs more larger sample size studies and RCT studies.

FMT technology is developing, which mainly involved the latest WMT and spores transplantation.[14,146] The evidence linking clinical findings and animal experiments supports that WMT is safer, more precise and more quality-controllable method than the crude FMT by manual. WMT has been widely used as a legal medical therapy requiring hospital ethical approval in China for CDI and beyond, especially for those difficult and critical dysbiosis-related diseases.[15] The latest research revealed that washed preparation of fecal microbiota has changed the transplantation-related safety, quantitative method, and delivery.[144] The purified Firmicutes spores from ethanol-treated donated stool were recently reported as an investigated new drug (SER-109) for the treatment of recurrent CDI in USA.[146] This opens up a new development path of FMT for the pharmaceutical industry. However, there is a lack of head-to-head study of regular FMT/WMT vs. SER-109 for their use for diseases beyond CDI.

Conclusion

The current review aimed to create an encyclopedia of clinical FMT reports of benefits including case reports, case series reports, real-world studies, and RCT studies. Since FMT was formally named in 2011, a total of emerging 85 diseases treated by FMT have been reported. The number of studies on FMT/WMT has increased dramatically within the past decade. Integrated with our previous systematic review on FMT-related AEs from 2000 to 2020 worldwide, we profiled the back side and front side of FMT. Although many further controlled trials will be needed, the dramatic increasing in reports has shown the promising future of FMT for dysbiosis-related diseases in the gut or beyond the gut.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81873548) and the Nanjing Medical University Fan Daiming Research Funds for Holistic Integrative Medicine.

Conflicts of interest

Zhang FM conceived the concept of GenFMTer, transendoscopic enteral tubing, and related devices. Borody TJ has a pecuniary interest in the Centre for Digestive Diseases, Finch Therapeutics, and Gioconda Ltd, and holds patents in the field of FMT and inflammatory bowel disease treatment. Other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

How to cite this article: Wang Y, Zhang S, Borody TJ, Zhang F. Encyclopedia of fecal microbiota transplantation: a review of effectiveness in the treatment of 85 diseases. Chin Med J 2022;135:1927–1939. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000002339

Supplemental digital content is available for this article.

References

- 1.Zhang F, Luo W, Shi Y, Fan Z, Ji G. Should we standardize the 1,700-year-old fecal microbiota transplantation? Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:1755.author reply p.1755-1756. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang F, Cui B, He X, Nie Y, Wu K, Fan D. Microbiota transplantation: Concept, methodology and strategy for its modernization. Protein Cell 2018; 9:462–473. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0541-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borody TJ, Khoruts A. Fecal microbiota transplantation and emerging applications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011; 9:88–96. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eiseman B, Silen W, Bascom GS, Kauvar AJ. Fecal enema as an adjunct in the treatment of pseudomembranous enterocolitis. Surgery 1958; 44:854–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Surawicz CM, Brandt LJ, Binion DG, Ananthakrishnan AN, Curry SR, Gilligan PH, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of Clostridium difficile infections. Am J Gastroenterol 2013; 108:478–498. quiz 499. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Zhao Y, Wang H, Peng Z, et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation strategy: a pilot study for steroid-dependent ulcerative colitis. J Transl Med 2015; 13:298.doi: 10.1186/s12967-015-0646-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Zhang T, Cui B, Ji G, et al. Long-term safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplant in active ulcerative colitis. Drug Saf 2019; 42:869–880. doi: 10.1007/s40264-019-00809-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costello SP, Hughes PA, Waters O, Bryant RV, Vincent AD, Blatchford P, et al. Effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on 8-week remission in patients with ulcerative colitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019; 321:156–164. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.20046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cui B, Feng Q, Wang H, Wang M, Peng Z, Li P, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation through mid-gut for refractory Crohn's disease: Safety, feasibility, and efficacy trial results. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 30:51–58. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiang L, Ding X, Li Q, Wu X, Dai M, Long C, et al. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation in Crohn's disease: A new target treatment? Microb Biotechnol 2020; 13:760–769. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Z, Cui BT, Zhang T, Li P, Long CY, Ji GZ, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation cured epilepsy in a case with Crohn's disease: The first report. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23:3565–3568. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i19.3565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kang DW, Adams JB, Gregory AC, Borody T, Chittick L, Fasano A, et al. Microbiota transfer therapy alters gut ecosystem and improves gastrointestinal and autism symptoms: an open-label study. Microbiome 2017; 5:10.doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0225-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biehl LM, Cruz Aguilar R, Farowski F, Hahn W, Nowag A, Wisplinghoff H, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in a kidney transplant recipient with recurrent urinary tract infection. Infection 2018; 46:871–874. doi: 10.1007/s15010-018-1190-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang T, Lu G, Zhao Z, Liu Y, Shen Q, Li P, et al. Washed microbiota transplantation vs. manual fecal microbiota transplantation: Clinical findings, animal studies and in vitro screening. Protein Cell 2020; 11:251–266. doi: 10.1007/s13238-019-00684-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fecal Microbiota Transplantation-standardization Study Group. Nanjing consensus on methodology of washed microbiota transplantation. Chin Med J 2020; 133:2330–2332. doi: 10.1097/cm9.0000000000000954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marcella C, Cui B, Kelly CR, Ianiro G, Cammarota G, Zhang F. Systematic review: The global incidence of faecal microbiota transplantation-related adverse events from 2000 to 2020. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2021; 53:33–42. doi: 10.1111/apt.16148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwan A, Sjölin S, Trottestam U, Aronsson B. Relapsing Clostridium difficile enterocolitis cured by rectal infusion of homologous faeces. Lancet 1983; 2:845.doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van Nood E, Vrieze A, Nieuwdorp M, Fuentes S, Zoetendal EG, de Vos WM, et al. Duodenal infusion of donor feces for recurrent Clostridium difficile. N Engl J Med 2013; 368:407–415. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kronman MP, Nielson HJ, Adler AL, Giefer MJ, Wahbeh G, Singh N, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation via nasogastric tube for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in pediatric patients. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2015; 60:23–26. doi: 10.1097/mpg.0000000000000545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Agrawal M, Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ, Kelly C, Freeman S, Surawicz C, et al. The long-term efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplant for recurrent, severe, and complicated Clostridium difficile infection in 146 elderly individuals. J Clin Gastroenterol 2016; 50:403–407. doi: 10.1097/mcg.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saeedi BJ, Morison DG, Kraft CS, Dhere T. Fecal microbiota transplant for Clostridium difficile infection in a pregnant patient. Obstet Gynecol 2017; 129:507–509. doi: 10.1097/aog.0000000000001911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roshan N, Clancy AK, Borody TJ. Faecal microbiota transplantation is effective for the initial treatment of Clostridium difficile infection: A retrospective clinical review. Infect Dis Ther 2020; 9:935–942. doi: 10.1007/s40121-020-00339-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meighani A, Hart BR, Bourgi K, Miller N, John A, Ramesh M. Outcomes of fecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Dis Sci 2017; 62:2870–2875. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4580-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng YW, Phelps E, Ganapini V, Khan N, Ouyang F, Xu H, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent and severe Clostridium difficile infection in solid organ transplant recipients: a multicenter experience. Am J Transplant 2019; 19:501–511. doi: 10.1111/ajt.15058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Elopre L, Rodriguez M. Fecal microbiota therapy for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection in HIV-infected persons. Ann Intern Med 2013; 158:779–780. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-158-10-201305210-00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Crum-Cianflone NF, Sullivan E, Ballon-Landa G. Fecal microbiota transplantation and successful resolution of multidrug-resistant-organism colonization. J Clin Microbiol 2015; 53:1986–1989. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00820-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee JH, Shin JB, Ko WJ, Kwon KS, Kim H, Shin YW. Efficacy and safety of fecal microbiota transplantation on clearance of multi-drug resistance organism in multicomorbid patients: A prospective non-randomized comparison trial. United European Gastroenterol J 2020; 8:499.doi: 10.1177/2050640620927345. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tariq R, Pardi DS, Tosh PK, Walker RC, Razonable RR, Khanna S. Fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent Clostridium difficile infection reduces recurrent urinary tract infection frequency. Clin Infect Dis 2017; 65:1745–1747. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai M, Liu Y, Chen W, Buch H, Shan Y, Chang L, et al. Rescue fecal microbiota transplantation for antibiotic-associated diarrhea in critically ill patients. Crit Care 2019; 23:324.doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2604-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang FM, Wang HG, Wang M, Cui BT, Fan ZN, Ji GZ. Fecal microbiota transplantation for severe enterocolonic fistulizing Crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol 2013; 19:7213–7216. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i41.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ye ZN, Xia HHX, Zhang R, Li L, Wu LH, Liu XJ, et al. The efficacy of washed microbiota transplantation on Helicobacter pylori eradication: A pilot study. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2020; 2020:8825189.doi: 10.1155/2020/8825189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pan JS. Fecal microbiota transplantation accelerates the healing of pyogenic liver abscess. Hepatol Int 2017; 11:S853–S854. doi: 10.1007/s12072-016-9783-9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li Q, Wang C, Tang C, He Q, Zhao X, Li N, et al. Successful treatment of severe sepsis and diarrhea after vagotomy utilizing fecal microbiota transplantation: A case report. Crit Care 2015; 19:37.doi: 10.1186/s13054-015-0738-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wei Y, Yang J, Wang J, Yang Y, Huang J, Gong H, et al. Successful treatment with fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with multiple organ dysfunction syndrome and diarrhea following severe sepsis. Crit Care 2016; 20:332.doi: 10.1186/s13054-016-1491-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ren YD, Ye ZS, Yang LZ, Jin LX, Wei WJ, Deng YY, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces hepatitis B virus e-antigen (HBeAg) clearance in patients with positive HBeAg after long-term antiviral therapy. Hepatology 2017; 65:1765–1768. doi: 10.1002/hep.29008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chauhan A, Kumar R, Sharma S, Mahanta M, Vayuuru SK, Nayak B, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in hepatitis B e antigen-positive chronic hepatitis B patients: A pilot study. Dig Dis Sci 2021; 66:873–880. doi: 10.1007/s10620-020-06246-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahmad J, Kumar M, Sarin SK, Sharma S, Choudhury A, Jindal A, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation with tenofovir is superior to tenofovir alone in improving clinical outcomes in acute-on-chronic liver failure due to hepatitis B: An open label randomized controlled trial (NCT02689245). J Hepatol 2019; 70:e102.doi: 10.1016/S0618-8278(19)30181-1. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Biliński J, Winter K, Jasiński M, Szczęś A, Bilinska N, Mullish BH, et al. Rapid resolution of COVID-19 after faecal microbiota transplantation. Gut 2022; 71:230–232. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2021-325010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Barberio B, Massimi D, Bonfante L, Facchin S, Calò L, Trevenzoli M, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for norovirus infection: A clinical and microbiological success. Therap Adv Gastroenterol 2020; 13:1756284820934589.doi: 10.1177/1756284820934589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karolewska-Bochenek K, Lazowska-Przeorek I, Grzesiowski P, Dziekiewicz M, Dembinski L, Albrecht P, et al. Faecal microbiota transfer - A new concept for treating cytomegalovirus colitis in children with ulcerative colitis. Ann Agric Environ Med 2021; 28:56–60. doi: 10.26444/aaem/118189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu X, Cui BT, Zhang FM. Washed microbiota transplantation for the treatment of recurrent fungal infection in a patient with ulcerative colitis. Chin Med J 2021; 134:741–742. doi: 10.1097/CM9.0000000000001212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Borody TJ, George L, Andrews P, Brandl S, Noonan S, Cole P, et al. Bowel-flora alteration: A potential cure for inflammatory bowel disease and irritable bowel syndrome? Med J Aust 1989; 150:604.doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1989.tb136704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Borody T, Wettstein A, Campbell J, Leis S, Torres M, Finlayson S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in ulcerative colitis: Review of 24 years experience. Am J Gastroenterol 2012; 107:S665.doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.275. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paramsothy S, Kamm MA, Kaakoush NO, Walsh AJ, van den Bogaerde J, Samuel D, et al. Multidonor intensive faecal microbiota transplantation for active ulcerative colitis: A randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2017; 389:1218–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30182-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Haifer C, Paramsothy S, Kaakoush NO, Saikal A, Ghaly S, Yang T, et al. Lyophilised oral faecal microbiota transplantation for ulcerative colitis (LOTUS): A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2022; 7:141–151. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(21)00400-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sokol H, Landman C, Seksik P, Berard L, Montil M, Nion-Larmurier I, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to maintain remission in Crohn's disease: a pilot randomized controlled study. Microbiome 2020; 8:12.doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-0792-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tian H, Ge X, Nie Y, Yang L, Ding C, McFarland LV, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with slow-transit constipation: A randomized, clinical trial. PLoS One 2017; 12:e0171308.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pinn DM, Aroniadis OC, Brandt LJ. Is fecal microbiota transplantation the answer for irritable bowel syndrome? A single-center experience. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109:1831–1832. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Johnsen PH, Hilpüsch F, Cavanagh JP, Leikanger IS, Kolstad C, Valle PC, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation versus placebo for moderate-to-severe irritable bowel syndrome: a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, single-centre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2018; 3:17–24. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30338-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.El-Salhy M, Hatlebakk JG, Gilja OH, Bråthen Kristoffersen A, Hausken T. Efficacy of faecal microbiota transplantation for patients with irritable bowel syndrome in a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gut 2020; 69:859–867. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang S, Kraft CS, Dhere T, Srinivasan J, Begley B, Weinstein D, et al. Successful treatment of chronic pouchitis utilizing fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT): A case report. Int J Colorectal Dis 2016; 31:1093–1094. doi: 10.1007/s00384-015-2428-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stallmach A, Lange K, Buening J, Sina C, Vital M, Pieper DH. Fecal microbiota transfer in patients with chronic antibiotic-refractory pouchitis. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111:441–443. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kousgaard SJ, Michaelsen TY, Nielsen HL, Kirk KF, Brandt J, Albertsen M, et al. Clinical results and microbiota changes after faecal microbiota transplantation for chronic pouchitis: a pilot study. Scand J Gastroenterol 2020; 55:421–429. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2020.1748221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dai YX, Shi CB, Cui BT, Wang M, Ji GZ, Zhang FM. Fecal microbiota transplantation and prednisone for severe eosinophilic gastroenteritis. World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20:16368–16371. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i43.16368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Liu SX, Li YH, Dai WK, Li XS, Qiu CZ, Ruan ML, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation induces remission of infantile allergic colitis through gut microbiota re-establishment. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23:8570–8581. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i48.8570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clancy A, Borody T. Improvement in food intolerance symptoms after pretreatment with antibiotics followed by faecal microbiota transplantation: A case report. Case Rep Clin Nutr 2021; 4:7–13. doi: 10.1159/000517306. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gundling F, Tiller M, Agha A, Schepp W, Iesalnieks I. Successful autologous fecal transplantation for chronic diversion colitis. Tech Coloproctol 2015; 19:51–52. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1220-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tominaga K, Tsuchiya A, Yokoyama J, Terai S. How do you treat this diversion ileitis and pouchitis? Gut 2019; 68:593–758. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2017-315591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doran A, Vance S, Warren C, Kolling G, Chaplain A, Archbald-Pannone L, et al. Microscopic colitis in recurrent C. difficile infection may resolve spontaneously after FMT. Am J Gastroenterol 2015; 110:S584.doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.294. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Günaltay S, Rademacher L, Hörnquist EH, Bohr J. Clinical and immunologic effects of faecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with collagenous colitis. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23:1319–1324. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i7.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Meyer DC, Hill SS, Bebinger DM, McDade JA, Davids JS, Alavi K, et al. Resolution of multiply recurrent and multifocal diverticulitis after fecal microbiota transplantation. Tech Coloproctol 2020; 24:971–975. doi: 10.1007/s10151-020-02275-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zheng YM, Chen XY, Cai JY, Yuan Y, Xie WR, Xu JT, et al. Washed microbiota transplantation reduces proton pump inhibitor dependency in nonerosive reflux disease. World J Gastroenterol 2021; 27:513–522. doi: 10.3748/WJG.V27.I6.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.van Beurden YH, van Gils T, van Gils NA, Kassam Z, Mulder CJJ, Aparicio-Pagés N. Serendipity in refractory celiac disease: Full recovery of duodenal villi and clinical symptoms after fecal microbiota transfer. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis 2016; 25:385–388. doi: 10.15403/jgld.2014.1121.253.cel. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lahtinen P, Mattila E, Anttila VJ, Tillonen J, Teittinen M, Nevalainen P, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation in patients with Clostridium difficile and significant comorbidities as well as in patients with new indications: A case series. World J Gastroenterol 2017; 23:7174–7184. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v23.i39.7174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Xu F, Li N, Wang C, Xing H, Chen D, Wei Y. Clinical efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with small intestinal bacterial overgrowth: A randomized, placebo-controlled clinic study. BMC Gastroenterol 2021; 21:54.doi: 10.1186/s12876-021-01630-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Vandekerckhove E, Janssens F, Tate D, De Looze D. Treatment of gut fermentation syndrome with fecal microbiota transplantation. Ann Intern Med 2020; 173:855.doi: 10.7326/L20-0341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gu L, Ding C, Tian H, Yang B, Zhang X, Hua Y, et al. Serial frozen fecal microbiota transplantation in the treatment of chronic intestinal pseudo-obstruction: A preliminary study. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2017; 23:289–297. doi: 10.5056/jnm16074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Davidovics ZH, Vance K, Etienne N, Hyams JS. Fecal transplantation successfully treats recurrent D-lactic acidosis in a child with short bowel syndrome. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr 2017; 41:896–897. doi: 10.1177/0148607115619931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kao D, Roach B, Park H, Hotte N, Madsen K, Bain V, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in the management of hepatic encephalopathy. Hepatology 2016; 63:339–340. doi: 10.1002/hep.28121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bajaj JS, Kassam Z, Fagan A, Gavis EA, Liu E, Cox IJ, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant from a rational stool donor improves hepatic encephalopathy: A randomized clinical trial. Hepatology 2017; 66:1727–1738. doi: 10.1002/hep.29306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Mehta R, Kabrawala M, Nandwani S, Kalra P, Patel C, Desai P, et al. Preliminary experience with single fecal microbiota transplant for treatment of recurrent overt hepatic encephalopathy—A case series. Indian J Gastroenterol 2018; 37:559–562. doi: 10.1007/s12664-018-0906-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Philips CA, Phadke N, Ganesan K, Augustine P. Healthy donor faecal transplant for corticosteroid non-responsive severe alcoholic hepatitis. BMJ Case Rep 2017; 2017:bcr2017222310.doi: 10.1136/bcr-2017-222310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Philips CA, Pande A, Shasthry SM, Jamwal KD, Khillan V, Chandel SS, et al. Healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation in steroid-ineligible severe alcoholic hepatitis: A pilot study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2017; 15:600–602. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sharma S, Pande A, Khillan V, Rastogi A, Arora V, Shasthry SM, et al. Post-fecal microbiota transplant taxa correlate with 3-month survival in severe alcoholic hepatitis patients. J Hepatol 2020; 73:S137–S138. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(20)30785-6. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Craven L, Rahman A, Nair Parvathy S, Beaton M, Silverman J, Qumosani K, et al. Allogenic fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease improves abnormal small intestinal permeability: A randomized control trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:1055–1065. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Witjes JJ, Smits LP, Pekmez CT, Prodan A, Meijnikman AS, Troelstra MA, et al. Donor fecal microbiota transplantation alters gut microbiota and metabolites in obese individuals with steatohepatitis. Hepatol Commun 2020; 4:1578–1590. doi: 10.1002/hep4.1601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Dhiman RK, Roy A, Premkumar M, De A, Verma N, Duseja A. Single session fecal microbiota transplantation in decompensated cirrhosis: An initial experience of clinical endpoints. Hepatology 2020; 72:124A–125A. doi: 10.1002/hep.31578. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Woodhouse C, Edwards L, Mullish BH, Kronsten V, Tranah T, Zamalloa A, et al. Results of the PROFIT trial, a PROspective randomised placebo-controlled feasibility trial of faecal microbiota transplantation in advanced cirrhosis. J Hepatol 2020; 73:S77–S78. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(20)30687-5. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Philips CA, Augustine P, Phadke N. Healthy donor fecal microbiota transplantation for recurrent bacterial cholangitis in primary sclerosing cholangitis - a single case report. J Clin Transl Hepatol 2018; 6:438–441. doi: 10.14218/jcth.2018.00033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Allegretti JR, Kassam Z, Carrellas M, Mullish BH, Marchesi JR, Pechlivanis A, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: A pilot clinical trial. Am J Gastroenterol 2019; 114:1071–1079. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sun L, Li J, Lan LL, Li XA. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on hepatic myelopathy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98:e16430.doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000016430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ward L, O’Grady HM, Wu K, Cannon K, Workentine M, Louie T. Combined oral fecal capsules plus fecal enema as treatment of late-onset autism spectrum disorder in children: Report of a small case series. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3:2219.doi: 10.1093/ofid/ofw172.1767. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kang DW, Adams JB, Coleman DM, Pollard EL, Maldonado J, McDonough-Means S, et al. Long-term benefit of microbiota transfer therapy on autism symptoms and gut microbiota. Sci Rep 2019; 9:5821.doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-42183-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Huang H, Xu H, Luo Q, He J, Li M, Chen H, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation to treat Parkinson's disease with constipation: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98:e16163.doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000016163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Segal A, Zlotnik Y, Moyal-Atias K, Abuhasira R, Ifergane G. Fecal microbiota transplant as a potential treatment for Parkinson's disease - A case series. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2021; 207:106791.doi: 10.1016/j.clineuro.2021.106791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Kurokawa S, Kishimoto T, Mizuno S, Masaoka T, Naganuma M, Liang KC, et al. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with irritable bowel syndrome, functional diarrhea and functional constipation: An open-label observational study. J Affect Disord 2018; 235:506–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2018.04.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kilinçarslan S, Evrensel A. The effect of fecal microbiota transplantation on psychiatric symptoms among patients with inflammatory bowel disease: An experimental study. Actas Esp Psiquiatr 2020; 48:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cai T, Shi X, Yuan LZ, Tang D, Wang F. Fecal microbiota transplantation in an elderly patient with mental depression. Int Psychogeriatr 2019; 31:1525–1526. doi: 10.1017/S1041610219000115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hinton R. A case report looking at the effects of faecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2020; 54:649–650. doi: 10.1177/0004867420912834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Bajaj JS, Gavis EA, Fagan A, Wade JB, Thacker LR, Fuchs M, et al. A randomized clinical trial of fecal microbiota transplant for alcohol use disorder. Hepatology 2021; 73:1688–1700. doi: 10.1002/hep.31496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.De Clercq NC, Frissen MN, Davids M, Groen AK, Nieuwdorp M. Weight gain after fecal microbiota transplantation in a patient with recurrent underweight following clinical recovery from anorexia nervosa. Psychother Psychosom 2019; 88:52–54. doi: 10.1159/000495044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gunaratne AW, Clancy A, Borody T. Antibiotic therapy followed by faecal microbiota transplantation alleviates epilepsy - A case report. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:S1783.doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000715796.75284.28. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Hazan S. Rapid improvement in Alzheimer's disease symptoms following fecal microbiota transplantation: a case report. J Int Med Res 2020; 48:300060520925930.doi: 10.1177/0300060520925930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Park SH, Lee JH, Shin J, Kim JS, Cha B, Lee S, et al. Cognitive function improvement after fecal microbiota transplantation in Alzheimer's dementia patient: A case report. Curr Med Res Opin 2021; 37:1739–1744. doi: 10.1080/03007995.2021.1957807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kenyon JN, Coe S, Izadi H. A retrospective outcome study of 42 patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, 30 of whom had irritable bowel syndrome. Half were treated with oral approaches, and half were treated with faecal microbiome transplantation. Hum Microb J 2019; 13:100061.doi: 10.1016/j.humic.2019.100061. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Borody T, Leis S, Campbell J, Torres M, Nowak A. Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in multiple sclerosis (MS). Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:S352.doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.336_7. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Liu XJ, Wu LH, Xie WR, He XX. Faecal microbiota transplantation simultaneously ameliorated patient's essential tremor and irritable bowel syndrome. Psychogeriatrics 2020; 20:796–798. doi: 10.1111/psyg.12583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ding X, Li Q, Xiang L, Li P, Zhang T, Zhang F. Selective microbiota transplantation is effective for controlling Tourette's syndrome. United European Gastroenterol J 2019; 7:461–462. doi: 10.1177/205064061985467. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Cai TT, Ye XL, Yong HJ, Song B, Zheng XL, Cui BT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation relieve painful diabetic neuropathy: A case report. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97:e13543.doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Li YY, Zhu YX, Zhou Y, Qian C, Zou J, Chen RR, et al. Efficacy and safety of washed microbiota transplantation in the treatment of brittle diabetes. Chin J Diabetes Mellitus 2020; 12:962–967. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn115791-20200609-00356. [Google Scholar]

- 101.De Groot P, Nikolic T, Pellegrini S, Sordi V, Imangaliyev S, Rampanelli E, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation halts progression of human new-onset type 1 diabetes in a randomised controlled trial. Gut 2021; 70:92–105. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-322630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Muenyi V, Kerman DH. Changes in the body mass index (BMI) of patients treated with fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) for recurrent C. difficile infection. Gastroenterology 2017; 152:S820–S821. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(17)32834-2. [Google Scholar]

- 103.Allegretti JR, Kassam Z, Hurtado J, Marchesi JR, Mullish BH, Chiang A, et al. Impact of fecal microbiota transplantation with capsules on the prevention of metabolic syndrome among patients with obesity. Hormones (Athens) 2021; 20:209–211. doi: 10.1007/s42000-020-00265-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Xie WR, Yang XY, Deng ZH, Zheng YM, Zhang R, Wu LH, et al. Effects of washed microbiota transplantation on serum uric acid levels, symptoms and intestinal barrier function in patients with acute and recurrent gout: a pilot study. Dig Dis 2021; doi: 10.1159/000521273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Davar D, Dzutsev AK, McCulloch JA, Rodrigues RR, Chauvin JM, Morrison RM, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant overcomes resistance to anti-PD-1 therapy in melanoma patients. Science 2021; 371:595–602. doi: 10.1126/science.abf3363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Baruch EN, Youngster I, Ben-Betzalel G, Ortenberg R, Lahat A, Katz L, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant promotes response in immunotherapy-refractory melanoma patients. Science 2021; 371:602–609. doi: 10.1126/science.abb5920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.De Clercq NC, van den Ende T, Prodan A, Hemke R, Davids M, Pedersen HK, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation from overweight or obese donors in cachectic patients with advanced gastroesophageal cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase II study. Clin Cancer Res 2021; 27:3784–3792. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jagessar SAR, Long C, Cui B, Zhang F. Improvement of Good's syndrome by fecal microbiota transplantation: The first case report. J Int Med Res 2019; 47:3408–3415. doi: 10.1177/0300060519854913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Ding X, Li Q, Li P, Chen X, Xiang L, Bi L, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation: A promising treatment for radiation enteritis? Radiother Oncol 2020; 143:12–18. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2020.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Wang Y, Wiesnoski DH, Helmink BA, Gopalakrishnan V, Choi K, DuPont HL, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for refractory immune checkpoint inhibitor-associated colitis. Nat Med 2018; 24:1804–1808. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Wang Y, Ma W, Abu-Sbeih H, Jiang ZD, DuPont H, Thomas AS. Fecal microbiota transplant (FMT) for immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) induced-colitis (IMC) refractory to immunosuppressive therapy. Am J Gastroenterol 2020; 115:S89.doi: 10.14309/01.ajg.0000702784.27702.88. [Google Scholar]

- 112.Ianiro G, Rossi E, Thomas AM, Schinzari G, Masucci L, Quaranta G, et al. Faecal microbiota transplantation for the treatment of diarrhoea induced by tyrosine-kinase inhibitors in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun 2020; 11:4333.doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-18127-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kakihana K, Fujioka Y, Suda W, Najima Y, Kuwata G, Sasajima S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for patients with steroid-resistant acute graft-versus-host disease of the gut. Blood 2016; 128:2083–2088. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-05-717652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Qi X, Li X, Zhao Y, Wu X, Chen F, Ma X, et al. Treating steroid refractory intestinal acute graft-vs.-host disease with fecal microbiota transplantation: A pilot study. Front Immunol 2018; 9:2195.doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.02195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Zhao Y, Li X, Zhou Y, Gao J, Jiao Y, Zhu B, et al. Safety and efficacy of fecal microbiota transplantation for grade IV steroid refractory GI-GvHD patients: Interim results from FMT2017002 trial. Front Immunol 2021; 12:678476.doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.678476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Borody T, Campbell J, Torres M, Nowak A, Leis S. Reversal of idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura [ITP] with fecal microbiota transplantation [FMT]. Am J Gastroenterol 2011; 106:S352.doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.336_7. [Google Scholar]

- 117.Rebello D, Yen E, Lio P, Kelly CR. Unexpected benefits: Hair growth in two alopecia patients after fecal microbiota transplant. Am J Gastroenterol 2016; 111:S623–S624. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2016.365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Huang HL, Xu HM, Liu YD, Shou DW, Nie YQ, Chen HT, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation as a novel approach for the treatment of atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol 2021; 48:e574–e576. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.16169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Zhao J, Bai M, Yang X, Wang Y, Li R, Sun S. Alleviation of refractory IgA nephropathy by intensive fecal microbiota transplantation: The first case reports. Ren Fail 2021; 43:928–933. doi: 10.1080/0886022X.2021.1936038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Arteaga Muller GY, Camacho-Ortiz A, Garza-Gonzalez E, Flores-Treviño SM, Bocanegra-Ibarias P, Fabela-Valdez GC, et al. Decreased progression of CKD in patients undergoing fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT). J Am Soc Nephrol 2021; 32:731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Fretheim H, Chung BK, Didriksen H, Baekkevold ES, Midtvedt Ø, Brunborg C, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation in systemic sclerosis: A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized pilot trial. PLoS One 2020; 15:e0232739.doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Mahajan R, Midha V, Singh A, Mehta V, Gupta Y, Kaur K, et al. Incidental benefits after fecal microbiota transplant for ulcerative colitis. Intest Res 2020; 18:337–340. doi: 10.5217/ir.2019.00108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Wei Y, Li N, Xing H, Guo T, Gong H, Chen D. Effectiveness of fecal microbiota transplantation for severe diarrhea after drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome. Medicine (Baltimore) 2019; 98:e18476.doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000018476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Selvanderan SP, Goldblatt F, Nguyen NQ, Costello SP. Faecal microbiota transplantation for Clostridium difficile infection resulting in a decrease in psoriatic arthritis disease activity. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2019; 37:514–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Zeng J, Peng L, Zheng W, Huang F, Zhang N, Wu D, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation for rheumatoid arthritis: A case report. Clin Case Rep 2020; 9:906–909. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.3677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Zhong HJ, Zeng HL, Cai YL, Zhuang YP, Liou YL, Wu Q, et al. Washed microbiota transplantation lowers blood pressure in patients with hypertension. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2021; 11:679624.doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.679624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Zhang T, Ding X, Dai M, Zhang H. Washed microbiota transplantation in patients with respiratory spreading diseases: Practice recommendations. Med Microecol 2021; 7:100024.doi: 10.1016/j.medmic.2020.100024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Watane A, Cavuoto KM, Rojas M, Dermer H, O Day J, Banerjee S, et al. Fecal microbial transplant in individuals with immune-mediated dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol 2022; 233:90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2021.06.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Wu W, Shen N, Luo L, Deng Z, Chen J, Tao Y, et al. Fecal microbiota transplantation before hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in a pediatric case of chronic diarrhea with a FOXP3 mutation. Pediatr Neonatol 2021; 62:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2020.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Zhang F, Zhang T, Zhu H, Borody TJ. Evolution of fecal microbiota transplantation in methodology and ethical issues. Curr Opin Pharmacol 2019; 49:11–16. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2019.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Cammarota G, Ianiro G, Kelly CR, Mullish BH, Allegretti JR, Kassam Z, et al. International consensus conference on stool banking for faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2019; 68:2111–2121. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-319548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Haifer C, Kelly CR, Paramsothy S, Andresen D, Papanicolas LE, McKew GL, et al. Australian consensus statements for the regulation, production and use of faecal microbiota transplantation in clinical practice. Gut 2020; 69:801–810. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Ianiro G, Mullish BH, Kelly CR, Sokol H, Kassam Z, Ng SC, et al. Screening of faecal microbiota transplant donors during the COVID-19 outbreak: Suggestions for urgent updates from an international expert panel. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 2020; 5:430–432. doi: 10.1016/s2468-1253(20)30082-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Xiang L, Yu Y, Ding X, Zhang H, Wen Q, Cui B, et al. Exclusive enteral nutrition plus immediate vs. delayed washed microbiota transplantation in Crohn's disease with malnutrition: A randomized pilot study. Front Med (Lausanne) 2021; 8:666062.doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.666062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Halaweish HF, Boatman S, Staley C. Encapsulated fecal microbiota transplantation: development, efficacy, and clinical application. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 2022; 12:826114.doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2022.826114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, Zhang T, Xu L, Cui B, et al. Colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing: A novel way of transplanting fecal microbiota. Endosc Int Open 2016; 4:E610–E613. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-105205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Zhong M, Sun Y, Wang HG, Marcella C, Cui BT, Miao YL, et al. Awareness and attitude of fecal microbiota transplantation through transendoscopic enteral tubing among inflammatory bowel disease patients. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8:3786–3796. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i17.3786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Zhong M, Buch H, Wen Q, Long C, Cui B, Zhang F. Colonic transendoscopic enteral tubing: Route for a novel, safe, and convenient delivery of washed microbiota transplantation in children. Gastroenterol Res Pract 2021; 2021:6676962.doi: 10.1155/2021/6676962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Cui B, Li P, Xu L, Peng Z, Xiang J, He Z, et al. Step-up fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) strategy. Gut Microbes 2016; 7:323–328. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1151608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Fischer M, Sipe B, Cheng YW, Phelps E, Rogers N, Sagi S, et al. Fecal microbiota transplant in severe and severe-complicated Clostridium difficile: A promising treatment approach. Gut Microbes 2017; 8:289–302. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2016.1273998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Scheeler A. Where stool is a drug: International approaches to regulating the use of fecal microbiota for transplantation. J Law Med Ethics 2019; 47:524–540. doi: 10.1177/1073110519897729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Kragsnaes MS, Nilsson AC, Kjeldsen J, Holt HM, Rasmussen KF, Georgsen J, et al. How do I establish a stool bank for fecal microbiota transplantation within the blood- and tissue transplant service? Transfusion 2020; 60:1135–1141. doi: 10.1111/trf.15816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Keller JJ, Vehreschild MJ, Hvas CL, Jørgensen SM, Kupciskas J, Link A, et al. Stool for fecal microbiota transplantation should be classified as a transplant product and not as a drug. United European Gastroenterol J 2019; 7:1408–1410. doi: 10.1177/2050640619887579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Lu G, Wang W, Li P, Wen Q, Cui B, Zhang F. Washed preparation of faecal microbiota changes the transplantation related safety, quantitative method and delivery. Microb Biotechnol 2022; doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.14074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Allegretti JR, Mullish BH, Kelly C, Fischer M. The evolution of the use of faecal microbiota transplantation and emerging therapeutic indications. Lancet 2019; 394:420–431. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)31266-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Feuerstadt P, Louie TJ, Lashner B, Wang EEL, Diao L, Bryant JA, et al. SER-109, an oral microbiome therapy for recurrent Clostridioides difficile infection. N Engl J Med 2022; 386:220–229. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2106516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.