Abstract

Rationale

The incidence and sites of mucus accumulation and molecular regulation of mucin gene expression in coronavirus (COVID-19) lung disease have not been reported.

Objectives

To characterize the incidence of mucus accumulation and the mechanisms mediating mucin hypersecretion in COVID-19 lung disease.

Methods

Airway mucus and mucins were evaluated in COVID-19 autopsy lungs by Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff staining, immunohistochemical staining, RNA in situ hybridization, and spatial transcriptional profiling. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-infected human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cultures were used to investigate mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2–induced mucin expression and synthesis and test candidate countermeasures.

Measurements and Main Results

MUC5B and variably MUC5AC RNA concentrations were increased throughout all airway regions of COVID-19 autopsy lungs, notably in the subacute/chronic disease phase after SARS-CoV-2 clearance. In the distal lung, MUC5B-dominated mucus plugging was observed in 90% of subjects with COVID-19 in both morphologically identified bronchioles and microcysts, and MUC5B accumulated in damaged alveolar spaces. SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE cultures exhibited peak titers 3 days after inoculation, whereas induction of MUC5B/MUC5AC peaked 7–14 days after inoculation. SARS-CoV-2 infection of HBE cultures induced expression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands and inflammatory cytokines (e.g., IL-1α/β) associated with mucin gene regulation. Inhibiting EGFR/IL-1R pathways or administration of dexamethasone reduced SARS-CoV-2–induced mucin expression.

Conclusions

SARS-CoV-2 infection is associated with a high prevalence of distal airspace mucus accumulation and increased MUC5B expression in COVID-19 autopsy lungs. HBE culture studies identified roles for EGFR and IL-1R signaling in mucin gene regulation after SARS-CoV-2 infection. These data suggest that time-sensitive mucolytic agents, specific pathway inhibitors, or corticosteroid administration may be therapeutic for COVID-19 lung disease.

Keywords: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, airway mucin, MUC5B, MUC5AC

At a Glance Commentary

Scientific Knowledge on the Subject

Mucus clearance is a fundamental innate defense mechanism of the lung. Airway mucus exhibits a protective role against viral acquisition, but excessive mucus secretion and accumulation in response to viral infections can produce airway mucus obstruction. Despite reports of excessive mucus in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) clinical settings, comprehensive characterizations of the regulation of mucin secretion and sites of mucus accumulation in COVID-19 lungs have not been reported.

What This Study Adds to the Field

MUC5B-dominated mucin hypersecretion was observed throughout airway, but not alveolar, epithelia in COVID-19 autopsy lungs. Mucus accumulation was prevalent in the distal lung bronchioles, bronchiolized microcysts, and damaged alveolar regions. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)–infected human bronchial epithelial cell cultures exhibited maximal SARS-CoV-2 titers at Day 3 after inoculation, whereas the induction of MUC5B and MUC5AC RNA/protein peaked at Days 7–14 after inoculation. Inhibiting epidermal growth factor receptors, abrogation of IL-1 receptor activation, or dexamethasone administration reduced human bronchial epithelial cell mucin gene induction after SARS-CoV-2 infection. Mucolytic agents, epidermal growth factor receptor/IL-1 receptor antagonists, and/or corticosteroids may be beneficial at targeted intervals for the treatment of the airway mucoobstructive component of COVID-19 lung disease.

The secreted airway mucins provide broad protective roles against viral infections via mechanical clearance and decoy receptor activities (1–9). However, excessive mucin secretion can produce airway mucus obstruction after viral infection, deranging ventilation and serving as the nidus for secondary bacterial infections (10–12).

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) generated the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) global pandemic (13). The severity of COVID-19 principally reflects its pulmonary manifestations, including alveolar pneumonias and the acute respiratory distress syndrome (14, 15). Multiple clinical studies have reported increased mucus production in severe COVID-19 lung disease, including 1) increased MUC1 and MUC5AC concentrations in tracheal aspirates (16, 17), 2) repeated endotracheal tube obstruction caused by viscous mucus (18, 19), and 3) persistent mucus production during subacute to chronic clinical phases (20, 21). However, data describing the severity of airway mucus accumulation and/or alveolar mucus accumulation, sites of mucin hypersecretion, and the molecular pathways responsible for upregulation of mucin expression after SARS-CoV-2 infection are lacking.

In this study, we hypothesized that a combination of inflammatory and reparative/dysreparative responses to SARS-CoV-2 infection produces robust mucus accumulation in COVID-19 autopsy lungs. Accordingly, we investigated the sites of mucus accumulation, mucin gene expression patterns, and mucin gene regulatory pathways in a large collection of COVID-19 autopsy lungs using immunocytochemical, RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH), and spatial transcriptomic approaches. SARS-CoV-2 human bronchial epithelial (HBE) infection models quantitated the kinetics, magnitude, and mechanisms of mucin hypersecretion and searched for countermeasures. Some of the results of these studies have been reported previously in the form of an abstract (22).

Methods

COVID-19 Autopsy and Control Lungs

A diagram describing COVID-19 autopsy specimen sources and allocations to specific studies is shown in Figure 1 (details outlined in Table E1 in the online supplement). Descriptions of the methods for each study are available in the online supplement.

Figure 1.

A diagram showing acquisition, exclusion, and allocation of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) autopsy specimens. AB-PAS = Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff; IHC = immunohistochemistry; NIH = National Institutes of Health; RNA-ISH = RNA in situ hybridization; UNC = University of North Carolina.

Results

COVID-19 Autopsy Tracheobronchial Proximal Airway Epithelia Exhibit Mucin Hyperproduction

Twenty-one COVID-19 autopsy lungs were suitable for proximal airway studies (Figure 2). Intraepithelial Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS) staining was increased in COVID-19 proximal airways as compared with controls (Figures 2A and 2B). RNA-ISH molecular studies, performed in a subset of lungs with available tissues (n = 7), demonstrated increased MUC5B expression compared with controls MUC5AC expression followed a similar pattern but was not significantly different (Figures 2C and 2D). Of the seven proximal airways studied molecularly, SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA was detected by RNA-ISH in the epithelium of one acute (<20 d from symptom onset to death) and no chronic (>20 d from symptoms to death) COVID-19 autopsy lungs (Figure 2E).

Figure 2.

Goblet cell metaplasia and mucin gene expression in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and control autopsy proximal airways. (A) Representative images from control (CTRL) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) autopsy (COVID-19) tracheobronchial specimens stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS) and probed by RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH) for MUC5B and MUC5AC. (B) Morphometric quantification of AB-PAS staining signals in the tracheobronchial airways of control (n = 11) and COVID-19 autopsy specimens (n = 21). Triangles correspond to the same specimens shown in C and D. (C, D) RNA-ISH for (C) MUC5B and (D) MUC5AC signals in the tracheobronchial airways of control (n = 11) and COVID-19 autopsy specimens (n = 7). Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. NS = not significant; *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; Mann-Whitney U test. (E) Representative images from tracheas from acute and subacute/chronic COVID-19 autopsy lungs probed for SARS-CoV-2 RNA-ISH. One of five acute COVID-19 lungs (<20 d onset from symptoms to death) was SARS-CoV-2 RNA-ISH positive, whereas neither of two chronic (>20 d onset from symptoms to death) COVID-19 lungs was positive. Scale bars, 20 μm.

Distal Airway Mucus Accumulation and Mucin Gene Expression in COVID-19 Lungs

We initially investigated COVID-19 airway mucus accumulation within all distal airway structures (i.e., bronchioles and clustered microcyst structures) (see Figures 3A and 3B, Supplementary Methods, and Figures E5 and E6). Bronchioles were defined as single airways with a diameter <2 mm, an absence of cartilage and submucosal glands, and the presence of airway smooth muscle and an adjacent blood vessel (23). Microcysts were defined by criteria developed from idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) pathologic criteria, including clustered structures, <1 mm size, in areas adjacent to parenchymal damage/fibrosis (24–27).

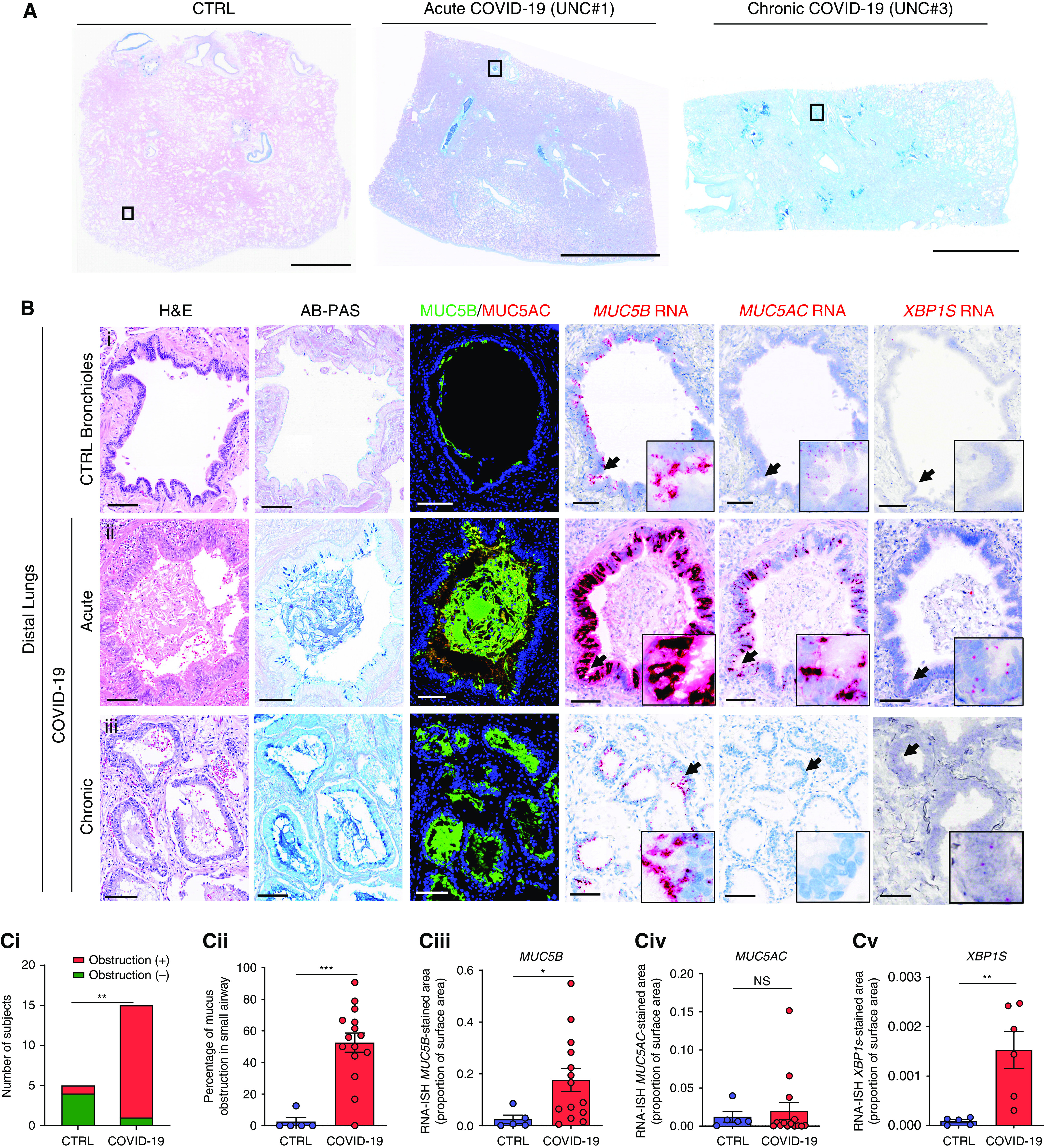

Figure 3.

MUC5B and MUC5AC RNA and protein expression in distal pulmonary regions of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and control autopsy lungs. (A) Representative low-power images of control (CTRL) and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)– infected (COVID-19) acute (3 d) and chronic (31 d) autopsy lung sections stained with Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS). (B) Magnified images of boxed regions of each tissue section shown in A stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and AB-PAS; immunofluorescence staining for MUC5B and MUC5AC protein; and probed for MUC5B, MUC5AC, and XBP1S by RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH). The control and acute COVID-19 airway structures were morphologically identified as bronchioles, whereas the structure in the chronic COVID-19 lung specimen was identified as a microcyst. Black arrows indicate the regions magnified in each inset. Scale bars, 5 mm (A); 100 μm (B). (C, i) Numbers of control versus COVID-19 autopsy subject lungs with mucus-obstructed airways. **P < 0.01; Fisher’s exact test. n = 5 for control and n = 15 for COVID-19. (C, ii) Percentage of distal airways within each autopsy lung specimen obstructed by mucus for control (n = 5) and COVID-19 (n = 15) lungs. Mann-Whitney U test. Total airway structures counted for control lungs = 31 (median, 6 per lung) and for COVID-19 lungs = 970 (median, 34 per lung). (C, iii–v) Morphometric quantification of RNA-ISH (C, iii) MUC5B, (C, iv) MUC5AC, and (C, v) XBP1S expression in distal airway structures within control (n = 5) and COVID-19 autopsy lungs (n = 14 for MUC5B and MUC5AC and n = 7 for XBP1S). Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. Mann-Whitney U test. NS = not significant; *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.001. UNC = University of North Carolina.

We have previously reported that normal lungs exhibit 1) little mucus accumulation, 2) MUC5AC expression limited to large airways, and 3) MUC5B expression in proximal and preterminal bronchioles but not terminal bronchioles or alveoli (23). Of the 15 COVID-19 lungs suitable for distal lung studies, 14 (93%) exhibited mucus accumulation in distal airway structures, a percentage significantly greater than normal controls (Figure 3C, i). Importantly, in the COVID-19 lungs with mucus accumulation, >50% of the observed airway structures/lung exhibited mucus accumulation (Figure 3C, ii). Airway mucus accumulation was associated with increased epithelial MUC5B but not MUC5AC expression (Figure 3C, iii, iv). Notably, in regions with preserved bronchiolar structures, extension of MUC5B expression from preterminal into terminal/respiratory bronchioles was noted in COVID-19 but not normal airways (Figure E2). Increased XBP1S was also detected in distal airway epithelia, consistent with increased mucin synthesis and/or a role for XBP1S as a selective regulator of MUC5B expression in this region (Figure 3C, v) (28).

Sites of Mucin Hypersecretion/Mucus Accumulation in the Distal Lung

Mucus accumulation in bronchioles and microcysts likely reflects overlapping but different pathophysiologies and effects on pulmonary function. Therefore, detailed morphologic analyses were performed to assign the sites of mucus accumulation to pre-/terminal bronchiolar versus microcyst structures (Figure 4 and Supplementary Methods). Such analyses were difficult because of the degree of epithelial damage/repair and the paucity of molecular markers to distinguish the two structures.

Figure 4.

Mucus obstruction in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) bronchiolar and microcystic structures of COVID-19 autopsy lungs. (A, B) Representative images of Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS) and Sirius red staining for acute (A; n = 7) and chronic (B; n = 8) phase COVID-19 autopsy lungs. (A) AB-PAS–stained acute COVID-19 lung with bronchioles scored outlined in green and depicted in the magnified image to the right. (B) AB-PAS–stained chronic COVID-19 autopsy lung with microcysts outlined in red and in the magnified image to the right. Scale bars, 1 mm. (C) Number of control (CTRL) and acute versus chronic COVID-19 autopsy lungs that exhibit morphologically defined bronchioles only, microcysts only, or a combination of bronchioles and microcysts. (D) Numbers of control versus COVID-19 autopsy lungs with identified bronchioles without (–) or with (+) bronchiolar mucus accumulation/obstruction. (E) Percentage of mucus-obstructed bronchioles in each control and COVID-19 autopsy lung shown in D. Numbers bronchioles counted = 31 from 5 controls (median, 6 per lung) and 95 from 10 COVID-19 autopsy lungs (median, 6.5 per lung) in which bronchioles were morphologically identified. (F) Fraction of COVID-19 lungs with morphologically identified microcysts that exhibited concomitant mucus accumulation. Note: No control lungs exhibited microcysts. (G) Percentage of microcyst structures within each microcyst-containing COVID-19 autopsy lung with significant (⩾50% lumen) mucus accumulation. No microcysts for mucus accumulation in controls. (H, I) MUC5B (H) and MUC5AC (I) RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH)–stained area normalized to airway surface epithelia, subgrouped by the presence of microcysts (MC). Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. Fisher’s exact test (D), Mann-Whitney U test (E, G–I). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. BV = blood vessel; NIH = National Institutes of Health.

The distributions of bronchioles and microcysts defined morphologically by hematoxylin and eosin staining in the study cohorts as a function of disease stage are shown in Figures 4A–4C. Bronchioles only were identified in control lungs. Bronchioles were identified at similar frequencies within acute (five of seven) and chronic (five of eight) COVID-19 autopsy lungs. Microcyst clusters were identified in 9 of 15 COVID-19 autopsy lungs (Figure 4C), whereas no control lungs exhibited microcysts. As predicted from the hypothesis that microcysts emerge in response to parenchymal injury in the chronic COVID-19 phase, microcysts were more common in the chronic (seven of eight) than the acute (two of seven) phase COVID-19 lungs. Numbers of bronchioles counted in this study included 31 from 5 controls (median of 6 per lung) and 95 from the 10 COVID-19 lungs (median of 6.5 per lung) in which bronchioles could be identified. Eight hundred seventy-five individual microcyst structures were counted in the 9 microcyst-containing COVID-19 autopsy lungs/specimen (median of 90 per lung).

Mucus accumulation in bronchioles and microcysts was quantitated by AB-PAS staining. The fraction of autopsy lungs with mucus obstruction of morphologically identified bronchioles was greater in COVID-19 than control lungs (Figure 4D). The magnitude of the mucoobstructive bronchiolar burden per lung was also high in COVID-19 autopsy lungs, with an average of ∼50% of bronchioles within each COVID-19 lung exhibiting mucus obstruction (Figure 4E). Parallel analyses compared mucus accumulation in microcysts. All COVID-19 lungs that exhibited microcysts had concomitant mucus accumulation (Figure 4F). In COVID-19 lungs with microcysts, ∼60% of individual microcyst structures exhibited mucus accumulation (Figure 4G). Finally, a similar pattern of raised MUC5B expression, but not MUC5AC expression, as measured by RNA-ISH, was observed in both bronchiolar and microcyst structures (Figures 4H and 4I). These data suggest that the prevalence, severity, and MUC5B molecular basis of mucus accumulation is broadly similar in bronchioles and microcysts after SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Spatial Transcriptomic Studies of Distal/Terminal Bronchioles in COVID-19 Lungs

Spatial transcriptomic studies compared three COVID-19 lungs with four normal controls with goals of 1) molecular characterization of morphologically defined bronchioles versus microcysts (Figures 3 and 4) and 2) gaining insight into mucin synthesis/cell metabolic features associated with COVID-19–associated airway mucoobstruction. Regions of interest (ROIs) in two COVID-19 lungs (one acute, one chronic) were focused on morphologically defined distal bronchioles and on morphologically defined microcysts in the third chronic lung (see Supplementary Methods and Figure E3A). COVID-19 ROIs as a group were transcriptionally distinct from control ROIs, as evidenced by principal component analysis plots (Figure E3B). Trends for suppression of the distal airway markers SFTPB and SCGB3A2 were noted in COVID-19 distal airway structures (Figure E3C). Alveolar epithelial genes (e.g., SFTPC) were not detected in the sampled ROIs (Figure E3C). Notably, among the three studied COVID-19 lungs, the one with morphologically defined microcysts (UNC#3) contained epithelial cells with expression of aberrant basaloid gene features (Figure E3D) (29), suggesting the addition of an IPF-like pathophysiology to a postviral mucoregulatory epithelial dysfunction (i.e., bronchiolization of “microcysts”), which may resemble the features observed during lung repair after influenza or parainfluenza virus infection in mice (30–33). Spatial transcriptomic analyses of grouped COVID-19 bronchioles provided confirmatory evidence for upregulation of mucin-associated pathways, coupled to upregulated host defense response and remodeling pathways, whereas cilium assembly pathways were downregulated (Figure E4).

Alveolar MUC5B Accumulation

Immunofluorescence costaining of MUC5B with a pan-airway marker, SOX2, and an alveolar type II (ATII) cell marker, LAMP3, detected MUC5B protein in damaged COVID-19 lung alveolar spaces contiguous with bronchioles and microcysts (Figures E5 and E6). MUC5B mRNA expression was routinely observed in distal bronchioles and microcysts but rarely observed in MUC5B protein-containing alveoli lined by ATII cells (Figures E5 and E6).

Pathways Mediating Increased Mucin Secretion in COVID-19 Airways

The pattern of predominant upregulation of MUC5B in airway epithelia in COVID-19 lungs (Figures 3, 4, E2, E5, and E6) suggested that pathways associated with mucoobstructive diseases, not MUC5AC-dominated T2-inflammatory pathways, mediate mucin hypersecretion in COVID-19 lung disease (10, 34, 35). Ligands associated with mucin overproduction in mucoobstructive diseases (e.g., epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR] ligands; AREG [amphiregulin], IL1B, and IL6) were detected by RNA-ISH in inflammatory cells located within mucus plugs and airway epithelia in COVID-19 lungs (Figure 5A). Immunofluorescence colocalization studies demonstrated that these ligands were coexpressed most frequently with macrophage (CD68) and/or neutrophil markers (myeloperoxidase) predominately in intraluminal and submucosal regions (Figures 5B and 5C).

Figure 5.

Identification of candidate mucin transcriptional regulators AREG (amphiregulin), IL1B, and IL6 via RNA expression in coronavirus disease (COVID-19) autopsy lungs. (A) AREG, IL1B, and IL6 RNA expression in representative control (CTRL) and COVID-19 bronchioles. Upper right and lower left insets show intraepithelial and lumen areas, respectively. (B) Confocal microscopic images of fluorescence RNA in situ hybridization (RNA-ISH) for AREG, IL1B, or IL6 (red) with a macrophage marker CD68 (green) and a neutrophil marker MPO (myeloperoxidase; gray) with differential interference contrast (DIC) imaging of distal bronchioles in COVID-19 autopsy lungs. Arrows indicate the regions magnified in insets. Scale bars, 100 μm (A); 20 μm (B). (C) Frequency of AREG, IL1B, and IL6 colocalization with CD68+, MPO+, or double-positive/double-negative cells in the COVID-19 autopsy lungs (n = 4 or 5). A total of 200 randomly selected AREG/IL1B/IL6-positive cells were counted.

Bacterial Infection

To investigate the association between mucus accumulation and secondary bacterial infection, COVID-19 autopsy lungs were studied with bacterial 16S RNA-ISH probes. Of the 12 lungs studied, 8 (67%) exhibited positive bacterial 16S rRNA signals in mucus plugs (n = 2), peribronchial areas (n = 4), and alveolar regions (n = 3) (Figure E7). Thus, a significant fraction of COVID-19 lungs exhibited 16S RNA signals that were bronchiolocentric and likely associated with accumulated mucus.

SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE Cultures and Mucin–Gene Regulation

SARS-CoV-2 titers in HBE cultures peaked at Day 3 after inoculation, followed by virus suppression or elimination by Day 14 (Figure 6A). Bulk RNA-sequencing of SARS-CoV-2–infected and mock-infected HBEs revealed that both MUC5B and MUC5AC gene expression were upregulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection and peaked in the subacute (Day 7) to chronic phase (Day 14) (Figure 6B). These findings were paralleled by upregulation of genes associated with increased mucin gene transcription, including SPDEF (Figure E8A) (35–39). In contrast, RNAs coding for other host defense proteins secreted by club cells, including SCGB1A1 and SLPI, were decreased or unchanged over this SARS-CoV-2 postinfection interval (Figure E8B).

Figure 6.

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection of human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cultures over a 14-day interval. (A) Viral titers as plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/ml) over time. DPI = days postinfection. (B) Fold changes (virus vs. mock) in RNA transcripts per million (TPM) for the secretory mucins (MUC5B and MUC5AC) over time. (C) Histological sections of HBE cells at Days 3 and 14 after SARS-CoV-2 infection as visualized by hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining, Alcian blue and periodic acid–Schiff (AB-PAS) staining, and MUC5B and MUC5AC immunohistochemistry. Scale bar, 20 μm. (D) Fold changes (virus vs. mock) of HBE cell AB-PAS–positive areas normalized to basement membrane lengths at Days 3 and 14 after SARS-CoV-2 infection. (E) Fold changes (virus vs. mock) of MUC5B- and MUC5AC-positive areas normalized to HBE epithelial areas at Days 3 and 14 after SARS-CoV-2 infection. (F) IFN-β gene expression (expressed as transcripts/million [TPM]) in virus-infected versus mock cultures at Days 1, 3, 7, and 14 after inoculation. See Figure E11C for other IFN genes. (G) Fold changes (virus vs. mock) in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands (AREG [amphiregulin] and HBEGF) over time after infection. (H) Fold changes (virus vs. mock) in mucin-regulatory cytokine genes IL1A, IL1B, and IL-6. n = 14 individual HBE donors. Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. One-sample Wilcoxon test (B, D, E, G, H) and Wilcoxon test (F). NS = not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Histologic studies demonstrated that AB-PAS–positive HBE cells were more frequent in SARS-CoV-2–infected versus mock cultures after SARS-CoV-2 infection at Days 3 and 14 (Figures 6C and 6D). Immunohistochemical studies of SARS-CoV-2–infected HBEs confirmed upregulation of MUC5B expression in AB-PAS–positive mucous cells at Day 14 (Figures 6C and 6E). MUC5AC protein was scarcely detected at baseline and was not significantly induced after SARS-CoV-2 infection compared with controls (Figures 6C and 6E).

We next searched the HBE bulk RNA-sequencing data for genes activated by SARS-CoV-2 infection that may be associated within an upregulation of MUC5B. IFNs (e.g., IFNB1, IFNL1, and IFNL2) are mucin regulatory candidates and were induced by SARS-CoV-2 (Figures 6F and E8C) (40, 41). However, the temporal patterns of expression of IFNs and IFN-stimulated genes were the inverse of mucin induction (i.e., IFNs and IFN-stimulated genes peaked at Days 1–3 and waned by Day 14) (42) (Figures 6F, E8C, and E8D). Evidence of upregulation of the IFN-induced IDO1 and AHR genes implicated in mucin transcriptional regulation followed the same kinetics (Figure E8E) (42, 43). Furthermore, evidence of canonical cytochrome gene regulation by AHR was not detected (Figure E8F) (44). In contrast, EGFR ligand gene expression (e.g., AREG and HBEGF) was persistently elevated after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 6G) (45). Despite the absence of inflammatory cells in our in vitro model, expression of both IL1A and IL1B was also persistently upregulated after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 6H). Note, IL-6 is produced after IL-1α/β exposure in HBE cells (35, 44, 46, 47). Consistent with IL-1α/β induction, IL-6 expression was upregulated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, suggesting that IL-6 may also be a regulator of mucin gene expression (Figure 6H) (47). Accordingly, further characterizations of EGFR, IL-1α/β, and IL-6 causal relationships to mucin gene transcription in SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE cells were performed.

Inhibition of EGFR Blocks Mucin Gene Induction by SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Block of EGFR pathways with either an EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (gefitinib) or an EGFR monoclonal antibody (cetuximab) resulted in significant reduction of mucin gene expression in virus-infected cultures without effects on SARS-CoV-2 infectivity at Days 3 to 7 after inoculation (Figure 7). EGFR block was also associated with decreased expression of EGFR ligands (HBEGF, AREG) and inflammatory cytokines (CXCL8, IL6) but not other epithelial host defense (SGCB1A1, SLPI, MX2) or structural genes (FOXJ1, DNAH5) (Figures 7 and E9). The block of EGFR-mediated mucin gene transcription by an extracellular EGFR monoclonal antibody (cetuximab) suggests EGFR was activated by extracellular SARS-CoV-2–induced release of EGFR ligands (e.g., AREG or HB-EGF [heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor]).

Figure 7.

Effect of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibition on secretory mucin RNA expression and peak viral titers in severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)-infected human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cultures. (A, B) Mucin, EGFR ligand, cytokine (IL6, CXCL8) gene expression, and peak SARS-CoV-2 virus titers with EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor (gefitinib [Gefi]) (A) or EGFR monoclonal antibody (cetuximab [Cetu]) (B) administration versus vehicle. Data were derived from HBE cells from n = 6 or 7 donors. No correction has been made for multiple statistical comparisons. Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon test. NS = not significant; *P < 0.05.

IL-1R Ablation or IL-1R Inhibition Reduces Mucin Gene Induction after SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The SARS-CoV-2–induced increased RNA expression of MUC5B and MUC5AC genes was suppressed in IL1R1 CRISPR-knockout (CRISPR-KO) cultures (Figure 8A). Consistent with RNA data, histologic hematoxylin and eosin, AB-PAS, and whole-mount staining revealed that mucin production was inhibited in SARS-CoV-2–infected CRISPR-KO as compared with CRISPR negative control cells (Figures 8B, 8C, and E10A) (48). Note, the likely more sensitive whole-mount immunofluorescence staining technique detected MUC5AC as well as MUC5B protein induction after SARS-CoV-2 infection. However, the effects of IL-1R deletion were complex with respect to mucin induction. Most important, IL1R1-KO cells were less infectable than negative control cells, and infectivity was related to MUC5B and MUC5AC expression (Figures 8D and 8E). Associated with decreased infectivity, SARS-CoV-2–induced expression of mucoregulatory pathway ligands (e.g., AREG, HBEGF, and IL6) was also reduced in SARS-CoV-2–infected IL1R1-KO cells (Figure 8A). IL-1R block by an IL-1R antagonist, anakinra, though less active than IL1R1 KO, exhibited similar trends (Figure E10D), despite the strong effect of anakinra on IL-1β–mediated mucins and inflammatory pathways (Figure E10E).

Figure 8.

Effect of IL-1 receptor modulation on secretory mucin RNA expression and severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) viral infectivity. (A) Comparison of SARS-CoV-2 infection of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated IL-1 receptor knockout (KO) versus negative control (NC) human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells with respect to relative mRNA expression of MUC5B, MUC5AC, IL6, HBEGF, AREG, and CXCL8 normalized to TBP after 3- and 7-day inoculation. Data were derived from HBE cells from n = 5–7 donors. (B) Representative whole-mount immunofluorescence staining images for MUC5B (green), MUC5AC (red), α-tubulin (cilia; gray), and DAPI (nuclei) in NC or IL1R1 CRISPR KO HBE cells 7 days after SARS-CoV2 infection. Scale bar, 20 μm. (C) Quantification of MUC5B, MUC5AC, and α-tubulin staining area in IL1R1 KO versus NC HBEs normalized to DAPI-positive area. n = 5 donors. (D) SARS-CoV-2 viral titers in plaque-forming units per milliliter (PFU/ml) in NC versus IL1R1 CRISPR KO HBE cells after SARS-CoV2 infection over 7 days. n = 7 donors. DPI = days postinfection. (E) Linear regressions showing correlations between viral titers (PFU/ml) at Day 3 and MUC5B or MUC5AC RNA expression at Day 7. n = 5–7 donors. No correction has been made for multiple statistical comparisons. Scatterplot histograms present mean ± SEM. Mixed effect model (A, D), Mann-Whitney U tests (C), and Spearman’s rank-order correlation tests (ρ = Spearman’s rho) (E). *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

IL-6 Receptor Block

IL-6 administration minimally affected mucin secretion in HBE cells as compared with IL-1β as previously reported (35, 47) (Figure E11A). The IL-6R antagonist (tocilizumab) treatment did not modify mucin or related gene expression patterns after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure E11B).

Dexamethasone Inhibits Mucin Induction after SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Dexamethasone administration between Days 3 and 14 after SARS-CoV-2 inoculation significantly reduced MUC5B and MUC5AC RNA and protein expression at 14 days after inoculation (Figures 9A and 9B). Dexamethasone also reduced expression of SCGB1A1 but, as expected, increased expression of epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunit genes (49). Similar gene regulatory responses to dexamethasone were observed in mock cultures (Figure E12).

Figure 9.

Effect of dexamethasone treatment on severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2)–infected human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cultures and coronavirus disease (COVID-19) autopsy lungs. (A) Relative expression of mucin, SCGB1A1 (secretoglobin 1A1), SPDEF (sterile α-motif pointed domain epithelial specific transcription factor), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ligands, cytokines, and epithelial sodium channel (ENaC) subunit genes normalized to TBP, and peak virus titers. (B, i) Representative images of whole-mount vehicle versus dexamethasone (Dex)-treated HBE cultures stained for MUC5B (green), MUC5AC (red), cilia (α-tubulin; white), and nuclei (blue). Scale bars, 20 μm. (B, ii) Signal quantification in whole mounts of MUC5B and MUC5AC for SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE cultures treated with vehicle versus dexamethasone at 14 days after infection. Data were derived from HBE cells from n = 8 donors. (C) Percentage of airways obstructed/lung for COVID-19 autopsy lungs from patients treated (+) or not (–) with steroids during their clinical course (see Figure 4). (D) Relationships between MUC5B (D, i) and MUC5AC (D, ii) expression in COVID-19 autopsy lungs from patients not treated with (–) or treated with (+) steroids during their clinical course. RNA-ISH = fluorescence RNA in situ hybridization. Histogram bars and error bars represent mean ± SEM. Wilcoxon tests (B) and Mann-Whitney U tests (D). NS = not significant; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01.

Effect of Steroid Administration on COVID-19 Autopsy Distal Lung Mucus Accumulation/Mucin Expression

COVID-19 autopsy lungs were analyzed as a function of steroid administration. Although small in number, an interesting pattern emerged: 1) AB-PAS quantitation revealed no difference in the percentage of mucus-obstructed airway luminal structures with versus without steroid administration (Figure 9C), but 2) trends for decreased MUC5B and MUC5AC expression were observed in steroid-treated versus non–steroid-treated subjects (Figures 9D).

Discussion

The principal lower respiratory features of severe phase COVID-19 include dry cough, pneumonia, and hypoxemia. Although there are case reports suggesting airway mucus hypersecretion is also a feature of COVID-19, there are no comprehensive datasets describing the time course and sites of mucus hypersecretion/accumulation or mechanisms that trigger mucin hypersecretion in COVID-19 lungs (20, 50, 51).

Studies of proximal airway epithelia in COVID-19 autopsy lungs by RNA-ISH detected SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA coding for the spike protein in airway epithelia in acute phase disease but not in subacute to chronic phase disease (Figure 2E), consistent with patterns from other COVID-19 autopsy studies (52–54). Goblet cell metaplasia, characterized by MUC5B-dominated and more variable MUC5AC mucin expression, was observed in chronic phase COVID-19 tracheobronchial samples, consistent with previous reports of proximal airway mucin induction (16, 42) and endotracheal tube mucus obstruction (18, 19) in subjects with COVID-19 with prolonged ICU stays.

An important observation made by this study was the high prevalence (>90% of subjects) (Figures 3C, i; 4D; and 4F) and extensive fraction (∼50% of airways affected per subject) of mucus accumulation in distal airway epithelium-lined structures in COVID-19 lungs (Figures 3C, ii; 4E; and 4G). However, the phenotype of distal airway mucus accumulation in COVID-19 autopsy lungs is complex and reflects multiple time- and space-dependent pathophysiologies. Preterminal and terminal bronchioles, beginning with the acute phase of disease, exhibited significant mucus accumulation/obstruction (Figures 3 and 4). MUC5B was the dominant mucin upregulated in bronchiolar epithelia (Figures 3, 4, and E2). Post–SARS-CoV-2 infection-induced epithelial and inflammatory cell signaling pathways, including EGFR and cytokines (IL-1α/β, IL-6, nuclear factor [NF]-κB), likely mediate a significant component of the upregulation of MUC5B mucin transcription in these structures (Figures 5–8). These data suggest that bronchiolar mucus obstruction could contribute to the hypoxia, pulmonary inflammation, and secondary bacterial infection characteristic of the COVID-19 syndrome. Notably, the peripheral location of mucus plugging may explain why productive sputum is not a classic feature of COVID-19 (55). Our bronchiolar mucus plugging data are consistent with a recent computed tomography–based study of small airway disease after SARS-CoV-2 infection that revealed a high incidence of air trapping/small airway disease in COVID-19 survivors (56).

In parallel, a significant number of mucus-plugged microcyst-like structures, typically associated with damaged/fibrotic regions, were observed predominantly in chronic (>20 d) autopsy lungs (Figures 3, 4, E3, and E4). Microcyst-like structures have been observed after severe viral infection in mice, likely reflecting in part bronchiolization of damaged alveolar regions (30–33). Mucus accumulation with increased MUC5B expression in terminal bronchioles that do not normally express MUC5B and “bronchiolized microcysts” has also previously been reported in IPF (26, 29, 57, 58). Extensive molecular profiling of these affected regions in IPF has revealed complex and dynamic interrelationships between terminal bronchiolar secretory cells, termed “terminal airway-enriched secretory cells” or “respiratory airway secretory cells,” basal cells, and ATII/AT0 cells (59–63). Our molecular analyses of cell types lining distal airspace structures in SARS-CoV-2–infected lungs were limited by virus- and/or inflammation-induced suppression of defining distal bronchiolar cell genes (e.g., SCGB3A2) (Figure E3C). Nonetheless, global spatial transcriptomic approaches suggested that morphologically defined terminal bronchioles in COVID-19 specimens exhibited club cell–like gene signatures, including NOTCH, suppressed cilial genes, and upregulation of MUC5B and mucin secretory pathways, whereas the more distal microcyst-like structures were lined by MUC5B-expressing secretory epithelia but also with the basaloid-type cells reported in distal IPF microcysts (Figure E3D) (64, 65). This finding, plus the association of microcysts with areas of fibrosis, raises the possibility that IPF-like pathophysiologies also contribute to the increased MUC5B expression and mucus accumulation in the terminal respiratory units of subjects with later-stage COVID-19. Ultimately, elucidating the time and spatial evolution of the multiple pathophysiologies that may coalesce on mucin gene regulation/mucus accumulation in pre-/terminal bronchioles and alveolar ducts, and perhaps, eventually, microcysts, in the COVID-19 syndrome may require, among other studies, lineage-tracing studies in SARS-CoV-2– infected animal models (66).

Similarly, the implications of MUC5B accumulation in damaged alveoli of patients with COVID-19 are not yet clear. Aberrant MUC5B expression in alveolar regions has been reported in IPF, especially in association with a MUC5B promoter polymorphism (26, 57). Our RNA-ISH and immunohistochemical studies, however, suggest that MUC5B protein accumulation in alveoli of COVID-19 lungs did not reflect ectopic MUC5B secretion by ATII cells (Figures E5 and E6). It is possible that the extension of MUC5B expression into the terminal/respiratory bronchioles of patients with COVID-19, where MUC5B is not normally expressed, and/or microcysts allowed retrograde transport of secreted MUC5B protein into alveoli. Longitudinal studies of post–COVID-19 subjects are required to ascertain whether alveolar mucin accumulation and MUC5B polymorphisms relate to the incidence/severity of long-term clinical pulmonary outcomes.

Studies of inflammatory cells recovered by BAL from patients with COVID-19 lung disease and spatial transcriptomic studies of COVID-19 autopsy lungs have described pulmonary inflammatory cells as sources of mucoregulatory ligands (64, 67, 68). Our autopsy lung studies identified the proximity of inflammatory cells expressing AREG and IL-1β to airway epithelia that may add to or, perhaps, dominate intraepithelial mucin regulatory responses in chronic phase COVID-19 lungs (Figures 5B and 5C). These mucoregulatory ligands almost certainly are involved in mucin regulation throughout all airway regions but also may be important in upregulation of MUC5B in bronchiolized epithelial microcysts (24–26, 57).

SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE cultures investigated during acute (Days 1–3) and subacute/chronic (Days 7–14) phases provided insights into epithelium-intrinsic mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2–infected airway epithelial mucin gene induction. MUC5B and MUC5AC RNA and MUC5B protein concentrations increased coincident with waning infection/longer times after inoculation (Figure 6) (65). This pattern is consistent with our proximal airway COVID-19 autopsy data (Figure 2) and previous reports describing acutely infected COVID-19 patients with high viral loads and low mucin gene expression as compared to chronic COVID-19 patients with no/low viral loads, increased mucin gene expression, and persistent airway mucus production (19, 69).

A series of in vitro HBE studies suggested potential causal relationships between candidate SARS-CoV-2–induced mucoregulatory pathways and mucin transcription. For example, two different EGFR inhibitors produced significant reductions of mucin gene expression after SARS-CoV-2 infection (Figure 7). IL1R1 KO blunted viral replication, which hindered discrimination between direct versus indirect (e.g., inhibition of viral replication) effects on observed reductions in mucin gene transcription (Figure 8). The finding of reduced viral replication with IL-1R block/deletion is consistent with recent reports that IL-1β increases HBE cell SARS-CoV-2 infectivity (70). Studies of IL-6 monoclonal antibody–treated HBE cultures suggested that IL-1α/β–dependent induction of IL-6 production was not a significant contributor to mucin regulation (Figure E11). In sum, these data suggest that HBE mucin gene regulation in response to SARS-CoV-2 infection is mediated by multiple pathways, including both EGFR and IL-1R pathways, which may exhibit crosstalk with direct SARS-CoV-2 activation of NF-κB (70–74). Further studies are required to elucidate the integrated epithelial regulation of post–SARS-CoV-2 mucin regulatory responses.

Finally, the potential inhibitory effects of dexamethasone on mucin transcription, a recommended therapy for severely ill patients with COVID-19 requiring oxygen, ventilatory support, and/or acute respiratory distress syndrome, were studied (75–77). Dexamethasone administration initiated 3 days after SARS-CoV-2 infection of HBE cultures reduced MUC5B and MUC5AC expression at both RNA and protein levels 14 days after inoculation (Figure 9). These data paralleled the COVID-19 autopsy subgroup analysis revealing trends for reduced MUC5B and MUC5AC RNA expression in the steroid- versus non–steroid-treated patients (Figure 9). These observations suggest that one mode of dexamethasone effectiveness in the clinic reflects its mucoinhibitory activity. Systematic studies of COVID-19 mucus plugging in dexamethasone-treated subjects, complementing our in vitro observations, will be required to rigorously test this possibility in clinical settings.

However, as with many therapeutic agents, dexamethasone exhibited multiple effects on RNA expression, some of which may be adverse. For example, dexamethasone reduced SCGB1A1 expression, suggesting dexamethasone may impair mucosal immunity and/or alter airway cell populations. Furthermore, the observed dexamethasone induction of ENaC subunit expression is well characterized and may result in accelerated Na+/fluid absorption, dehydration of bronchiolar epithelial surfaces, and production of hyperconcentrated, difficult-to-clear mucus (78). The observations that the dexamethasone-treated subgroup of our COVID-19 autopsy cohort exhibited AB-PAS–defined mucoobstruction similar to the untreated subgroup, despite reduced mucin gene expression, may be consistent with a steroid-ENaC off-target effect (78, 79).

Limitations

Our study has limitations. For example, >50% of the autopsy specimens investigated exhibited extensive airway epithelial detachment/sloughing, causing exclusion from histologic/molecular investigations (Figures 1 and E1). One report indicated that tracheobronchial obstruction observed in COVID-19 might be caused by sloughed epithelium (18). However, it was not possible to discern whether the sloughing observed histologically reflected virus-induced disease or postmortem artifacts. Our morphometric analyses were also limited by absence of inflation procedures for COVID-19 lungs and limited blocks/lung for analyses. The limitations in defining terminal bronchiolar/microcyst structures are discussed above (Figure E3C). Finally, our COVID-19 autopsy cohort included specimens from patients early in the pandemic, without steroid treatment, and later specimens from patients treated with steroid regimens that varied in dose, agent, and duration. Although this treatment difference allowed some quantitative comparisons, the variation in this therapeutic agent and others remains a limitation.

In summary, in vivo and in vitro studies demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection causes striking subacute to chronic MUC5B-dominated distal airway mucus accumulation via, in part, EGFR- and IL-1R–dependent pathways. These data suggest that direct-acting mucolytic agents, and perhaps inhibitors of mucin transcriptional regulatory pathways, may be beneficial at targeted times in the COVID-19 clinical course. The opposing effects of dexamethasone administration (i.e., reduced mucin gene expression) raised ENaC expression in SARS-CoV-2–infected HBE cultures, which suggests the need to clarify the risk/benefit ratio of this agent in treating the mucoobstructive component of SARS-CoV-2–induced lung disease. Finally, the mucus plugging in the distal microcyst regions associated with fibrosis may reflect a different time domain/IPF-like pathophysiology (e.g., XBP1S dependent). The role of antifibrotic agents in this disease manifestation is under investigation in mouse models and clinical trials (66). An important challenge for therapy of all phases of disease will be to identify effective biomarkers of bronchiolar/distal lung mucus to gauge therapeutic effectiveness.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Eric Roe for editing the manuscript. They also thank the UNC Tissue Procurement and Cell Culture Core for providing HBE cells; Lauren Ralph, Edison Floyd, and Mia Evangelista in the Pathology Services Core for expert technical assistance with sectioning, histological staining, and GeoMx assays; the Center for Gastrointestinal Biology and Disease for sectioning the tissue blocks; and the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center Translational Genomics Lab for performing GeoMx sequencing procedures.

Footnotes

Supported by NIH grants (UH3 HL123645, R01 HL136961, P30 DK 065988, P30 DK 034987, and P01 HL108808 [R.C.B.], R01 HL155951 [G.C.], and AI108197 and AI157253 [R.S.B.]) and by Cystic Fibrosis Foundation grants BOUCHE19R0 and BOUCHE19XX0 (R.C.B.), KATO20I0 (T.K.), MIKAMI19XX0 (Y.M.), and OKUDA20G0 (K.O.). T.A. is a Japan Society for the Promotion of Science Overseas Research Fellow. Additional grant support includes Carolina for the Kids Faculty Grant 2021 (G.C.) and an Emergent Ventures Fast Grant (Fast Grants Award 2250). The authors also acknowledge the generous support provided by the Rapidly Emerging Antiviral Drug Development Initiative at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. The Pathology Services Core at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill is supported in part by a National Cancer Institute Center Core Support Grant (5P30CA016080-42).

Author Contributions: S.H.R. provided primary human bronchial epithelial (HBE) cells and excised lungs. K.O. and F.B.A. provided human control lung sections. L.B.T., A.C.B., S.S., F.J.M., S.M.H., D.S.C., and the NIH COVID-19 Autopsy Consortium provided COVID-19 autopsy lung sections. T.K., T.A., and P.H. reviewed these sections. C.E.E., M.R.C., and A.B.B. performed in vitro SARS-CoV-2 infection to HBE cell cultures and virus titering. H.D. and Y.M. contributed to bioinformatic and statistical analyses. R.C.G. performed RNA in situ hybridization. L.S. performed Western blotting. T.K., T.A., and Y.M. quantified the images. T.K. and T.A. performed all the other experiments. C.E. provided mouse anti-MUC5B antibody. G.D.l.C. supervised the GeoMx assays. G.C. and W.K.O’N. provided guidance and feedback on the overall work. W.K.O’N., S.H.R., R.S.B., and R.C.B. designed and supervised the project. T.K. and T.A. drafted the manuscript. T.K., T.A., W.K.O’N., and R.C.B. finalized the manuscript. All the authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This article has an online supplement, which is accessible from this issue’s table of contents at www.atsjournals.org.

Originally Published in Press as DOI: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2606OC on July 11, 2022

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. McAuley JL, Corcilius L, Tan HX, Payne RJ, McGuckin MA, Brown LE. The cell surface mucin MUC1 limits the severity of influenza A virus infection. Mucosal Immunol . 2017;10:1581–1593. doi: 10.1038/mi.2017.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roy MG, Livraghi-Butrico A, Fletcher AA, McElwee MM, Evans SE, Boerner RM, et al. Muc5b is required for airway defence. Nature . 2014;505:412–416. doi: 10.1038/nature12807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wallace LE, Liu M, van Kuppeveld FJM, de Vries E, de Haan CAM. Respiratory mucus as a virus-host range determinant. Trends Microbiol . 2021;29:983–992. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2021.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Adivitiya, Kaushik MS, Chakraborty S, Veleri S, Kateriya S. Mucociliary respiratory epithelium integrity in molecular defense and susceptibility to pulmonary viral infections. Biology (Basel) . 2021;10:95. doi: 10.3390/biology10020095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zanin M, Baviskar P, Webster R, Webby R. The interaction between respiratory pathogens and mucus. Cell Host Microbe . 2016;19:159–168. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2016.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chatterjee M, van Putten JPM, Strijbis K. Defensive properties of mucin glycoproteins during respiratory infections-relevance for SARS-CoV-2. MBio . 2020;11:e02374-20. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02374-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Denneny E, Sahota J, Beatson R, Thornton D, Burchell J, Porter J. Mucins and their receptors in chronic lung disease. Clin Transl Immunology . 2020;9:e01120. doi: 10.1002/cti2.1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. McShane A, Bath J, Jaramillo AM, Ridley C, Walsh AA, Evans CM, et al. Mucus. Curr Biol . 2021;31:R938–R945. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2021.06.093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wardzala CL, Wood AM, Belnap DM, Kramer JR. Mucins inhibit coronavirus infection in a glycan-dependent manner. ACS Cent Sci . 2022;8:351–360. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.1c01369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boucher RC. Muco-obstructive lung diseases. N Engl J Med . 2019;380:1941–1953. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1813799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Koeppen M, McNamee EN, Brodsky KS, Aherne CM, Faigle M, Downey GP, et al. Detrimental role of the airway mucin Muc5ac during ventilator-induced lung injury. Mucosal Immunol . 2013;6:762–775. doi: 10.1038/mi.2012.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Singanayagam A, Footitt J, Marczynski M, Radicioni G, Cross MT, Finney LJ, et al. Airway mucins promote immunopathology in virus-exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. J Clin Invest . 2022;132:e120901. doi: 10.1172/JCI120901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. China Novel Coronavirus Investigating and Research Team A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med . 2020;382:727–733. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet . 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet . 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lu W, Liu X, Wang T, Liu F, Zhu A, Lin Y, et al. Elevated MUC1 and MUC5AC mucin protein levels in airway mucus of critical ill COVID-19 patients. J Med Virol . 2021;93:582–584. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. He J, Cai S, Feng H, Cai B, Lin L, Mai Y, et al. Single-cell analysis reveals bronchoalveolar epithelial dysfunction in COVID-19 patients. Protein Cell . 2020;11:680–687. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rubano JA, Jasinski PT, Rutigliano DN, Tassiopoulos AK, Davis JE, Beg T, et al. Tracheobronchial slough, a potential pathology in endotracheal tube obstruction in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the intensive care setting. Ann Surg . 2020;272:e63–e65. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000004031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wiles S, Mireles-Cabodevila E, Neuhofs S, Mukhopadhyay S, Reynolds JP, Hatipoğlu U. Endotracheal tube obstruction among patients mechanically ventilated for ARDS due to COVID-19: a case series. J Intensive Care Med . 2021;36:604–611. doi: 10.1177/0885066620981891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Manckoundia P, Franon E. Is persistent thick copious mucus a long-term symptom of COVID-19? Eur J Case Rep Intern Med . 2020;7:002145. doi: 10.12890/2020_002145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Manna S, Baindara P, Mandal SM. Molecular pathogenesis of secondary bacterial infection associated to viral infections including SARS-CoV-2. J Infect Public Health . 2020;13:1397–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2020.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kato T, Asakura T, Edwards C, Dang H, Mikami Y, Okuda K, et al. Prevalence and mechanisms of bronchiolar mucus plugging in COVID-19 lung disease [abstract] Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2022;205:A3612. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202111-2606OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Okuda K, Chen G, Subramani DB, Wolf M, Gilmore RC, Kato T, et al. Localization of secretory mucins MUC5AC and MUC5B in normal/healthy human airways. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;199:715–727. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201804-0734OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Verleden SE, Tanabe N, McDonough JE, Vasilescu DM, Xu F, Wuyts WA, et al. Small airways pathology in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet Respir Med . 2020;8:573–584. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30356-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Chilosi M, Poletti V, Murer B, Lestani M, Cancellieri A, Montagna L, et al. Abnormal re-epithelialization and lung remodeling in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: the role of deltaN-p63. Lab Invest . 2002;82:1335–1345. doi: 10.1097/01.lab.0000032380.82232.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Seibold MA, Smith RW, Urbanek C, Groshong SD, Cosgrove GP, Brown KK, et al. The idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis honeycomb cyst contains a mucocilary pseudostratified epithelium. PLoS One . 2013;8:e58658. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ikezoe K, Hackett TL, Peterson S, Prins D, Hague CJ, Murphy D, et al. Small airway reduction and fibrosis is an early pathologic feature of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;204:1048–1059. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202103-0585OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chen G, Ribeiro CMP, Sun L, Okuda K, Kato T, Gilmore RC, et al. XBP1S regulates MUC5B in a promoter variant-dependent pathway in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis airway epithelia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2019;200:220–234. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201810-1972OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adams TS, Schupp JC, Poli S, Ayaub EA, Neumark N, Ahangari F, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals ectopic and aberrant lung-resident cell populations in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Sci Adv . 2020;6:eaba1983. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aba1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Vaughan AE, Brumwell AN, Xi Y, Gotts JE, Brownfield DG, Treutlein B, et al. Lineage-negative progenitors mobilize to regenerate lung epithelium after major injury. Nature . 2015;517:621–625. doi: 10.1038/nature14112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zuo W, Zhang T, Wu DZ, Guan SP, Liew AA, Yamamoto Y, et al. p63+Krt5+ distal airway stem cells are essential for lung regeneration. Nature . 2015;517:616–620. doi: 10.1038/nature13903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Keeler SP, Agapov EV, Hinojosa ME, Letvin AN, Wu K, Holtzman MJ. Influenza A virus infection causes chronic lung disease linked to sites of active viral RNA remnants. J Immunol . 2018;201:2354–2368. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1800671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wu K, Kamimoto K, Zhang Y, Yang K, Keeler SP, Gerovac BJ, et al. Basal epithelial stem cells cross an alarmin checkpoint for postviral lung disease. J Clin Invest . 2021;131:e149336. doi: 10.1172/JCI149336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Woodruff PG, Modrek B, Choy DF, Jia G, Abbas AR, Ellwanger A, et al. T-helper type 2-driven inflammation defines major subphenotypes of asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2009;180:388–395. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0392OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chen G, Sun L, Kato T, Okuda K, Martino MB, Abzhanova A, et al. IL-1β dominates the promucin secretory cytokine profile in cystic fibrosis. J Clin Invest . 2019;129:4433–4450. doi: 10.1172/JCI125669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Xu Y, Kitzmiller J, Wert SE, Maeda Y, et al. SPDEF is required for mouse pulmonary goblet cell differentiation and regulates a network of genes associated with mucus production. J Clin Invest . 2009;119:2914–2924. doi: 10.1172/JCI39731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Park KS, Korfhagen TR, Bruno MD, Kitzmiller JA, Wan H, Wert SE, et al. SPDEF regulates goblet cell hyperplasia in the airway epithelium. J Clin Invest . 2007;117:978–988. doi: 10.1172/JCI29176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Korfhagen TR, Kitzmiller J, Chen G, Sridharan A, Haitchi HM, Hegde RS, et al. SAM-pointed domain ETS factor mediates epithelial cell-intrinsic innate immune signaling during airway mucous metaplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA . 2012;109:16630–16635. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208092109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Chen G, Korfhagen TR, Karp CL, Impey S, Xu Y, Randell SH, et al. Foxa3 induces goblet cell metaplasia and inhibits innate antiviral immunity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2014;189:301–313. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201306-1181OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Sa Ribero M, Jouvenet N, Dreux M, Nisole S. Interplay between SARS-CoV-2 and the type I interferon response. PLoS Pathog . 2020;16:e1008737. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1008737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Park A, Iwasaki A. Type I and Type III interferons - induction, signaling, evasion, and application to combat COVID-19. Cell Host Microbe . 2020;27:870–878. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2020.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Liu Y, Lv J, Liu J, Li M, Xie J, Lv Q, et al. Mucus production stimulated by IFN-AhR signaling triggers hypoxia of COVID-19. Cell Res . 2020;30:1078–1087. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00435-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Giovannoni F, Quintana FJ. SARS-CoV-2-induced lung pathology: AHR as a candidate therapeutic target. Cell Res . 2021;31:1–2. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00447-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Vogel CF, Khan EM, Leung PS, Gershwin ME, Chang WL, Wu D, et al. Cross-talk between aryl hydrocarbon receptor and the inflammatory response: a role for nuclear factor-κB. J Biol Chem . 2014;289:1866–1875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.505578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Klann K, Bojkova D, Tascher G, Ciesek S, Münch C, Cinatl J. Growth factor receptor signaling inhibition prevents SARS-CoV-2 replication. Mol Cell . 2020;80:164–174.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Khan YM, Kirkham P, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Brd4 is essential for IL-1β-induced inflammation in human airway epithelial cells. PLoS One . 2014;9:e95051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0095051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chen Y, Thai P, Zhao YH, Ho YS, DeSouza MM, Wu R. Stimulation of airway mucin gene expression by interleukin (IL)-17 through IL-6 paracrine/autocrine loop. J Biol Chem . 2003;278:17036–17043. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210429200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Conant D, Hsiau T, Rossi N, Oki J, Maures T, Waite K, et al. Inference of CRISPR edits from Sanger trace data. CRISPR J . 2022;5:123–130. doi: 10.1089/crispr.2021.0113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rubenstein RC, Lockwood SR, Lide E, Bauer R, Suaud L, Grumbach Y. Regulation of endogenous ENaC functional expression by CFTR and ΔF508-CFTR in airway epithelial cells. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2011;300:L88–L101. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00142.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Konopka KE, Wilson A, Myers JL. Postmortem lung findings in a patient with asthma and coronavirus disease 2019. Chest . 2020;158:e99–e101. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Yin W, Cao W, Zhou G, Wang L, Sun J, Zhu A, et al. Analysis of pathological changes in the epithelium in COVID-19 patient airways. ERJ Open Res . 2021;7:00690-2020. doi: 10.1183/23120541.00690-2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Borczuk AC, Salvatore SP, Seshan SV, Patel SS, Bussel JB, Mostyka M, et al. COVID-19 pulmonary pathology: a multi-institutional autopsy cohort from Italy and New York City. Mod Pathol . 2020;33:2156–2168. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-00661-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schaefer IM, Padera RF, Solomon IH, Kanjilal S, Hammer MM, Hornick JL, et al. In situ detection of SARS-CoV-2 in lungs and airways of patients with COVID-19. Mod Pathol . 2020;33:2104–2114. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0595-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hou YJ, Okuda K, Edwards CE, Martinez DR, Asakura T, Dinnon KH, III, et al. SARS-CoV-2 reverse genetics reveals a variable infection gradient in the respiratory tract. Cell . 2020;182:429–446.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Dunican EM, Elicker BM, Henry T, Gierada DS, Schiebler ML, Anderson W, et al. Mucus plugs and emphysema in the pathophysiology of airflow obstruction and hypoxemia in smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2021;203:957–968. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202006-2248OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Cho JL, Villacreses R, Nagpal P, Guo J, Pezzulo AA, Thurman AL, et al. Quantitative chest CT assessment of small airways disease in post-acute SARS-CoV-2 infection. Radiology . 2022;304:185–192. doi: 10.1148/radiol.212170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Evans CM, Fingerlin TE, Schwarz MI, Lynch D, Kurche J, Warg L, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: a genetic disease that involves mucociliary dysfunction of the peripheral airways. Physiol Rev . 2016;96:1567–1591. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00004.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yang IV, Coldren CD, Leach SM, Seibold MA, Murphy E, Lin J, et al. Expression of cilium-associated genes defines novel molecular subtypes of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Thorax . 2013;68:1114–1121. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Basil MC, Cardenas-Diaz FL, Kathiriya JJ, Morley MP, Carl J, Brumwell AN, et al. Human distal airways contain a multipotent secretory cell that can regenerate alveoli. Nature . 2022;604:120–126. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04552-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rustam S, Hu Y, Mahjour SB, Randell SH, Rendeiro AF, Ravichandran H, et al. A unique cellular organization of human distal airways and its disarray in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease bioRxiv; 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 12]. Available from: 10.1101/2022.03.16.484543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Kadur Lakshminarasimha Murthy P, Sontake V, Tata A, Kobayashi Y, Macadlo L, Okuda K, et al. Human distal lung maps and lineage hierarchies reveal a bipotent progenitor. Nature . 2022;604:111–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04541-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Strunz M, Simon LM, Ansari M, Kathiriya JJ, Angelidis I, Mayr CH, et al. Alveolar regeneration through a Krt8+ transitional stem cell state that persists in human lung fibrosis. Nat Commun . 2020;11:3559. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17358-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Hogan BL, Barkauskas CE, Chapman HA, Epstein JA, Jain R, Hsia CC, et al. Repair and regeneration of the respiratory system: complexity, plasticity, and mechanisms of lung stem cell function. Cell Stem Cell . 2014;15:123–138. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2014.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Melms JC, Biermann J, Huang H, Wang Y, Nair A, Tagore S, et al. A molecular single-cell lung atlas of lethal COVID-19. Nature . 2021;595:114–119. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03569-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Posch W, Vosper J, Noureen A, Zaderer V, Witting C, Bertacchi G, et al. C5aR inhibition of nonimmune cells suppresses inflammation and maintains epithelial integrity in SARS-CoV-2-infected primary human airway epithelia. J Allergy Clin Immunol . 2021;147:2083–2097.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2021.03.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dinnon KH, III, Leist SR, Okuda K, Dang H, Fritch EJ, Gully KL, et al. A model of persistent post SARS-CoV-2 induced lung disease for target identification and testing of therapeutic strategies bioRxiv; 2022. [accessed 2022 Jul 12]. Available from: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abo5070. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Liao M, Liu Y, Yuan J, Wen Y, Xu G, Zhao J, et al. Single-cell landscape of bronchoalveolar immune cells in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med . 2020;26:842–844. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-0901-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Grant RA, Morales-Nebreda L, Markov NS, Swaminathan S, Querrey M, Guzman ER, et al. NU SCRIPT Study Investigators Circuits between infected macrophages and T cells in SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia. Nature . 2021;590:635–641. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-03148-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Desai N, Neyaz A, Szabolcs A, Shih AR, Chen JH, Thapar V, et al. Temporal and spatial heterogeneity of host response to SARS-CoV-2 pulmonary infection. Nat Commun . 2020;11:6319. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20139-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Nakano S, Okuda K, Edwards C, Dang H, Asakura T, Kato T, et al. Pathways balancing SARS-COV-2 infectivity and disease severity in CF [abstract] J Cyst Fibros . 2021;20:S244. [Google Scholar]

- 71. Su CM, Wang L, Yoo D. Activation of NF-κB and induction of proinflammatory cytokine expressions mediated by ORF7a protein of SARS-CoV-2. Sci Rep . 2021;11:13464. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92941-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Li Y, Tang XX. Abnormal airway mucus secretion induced by virus infection. Front Immunol . 2021;12:701443. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.701443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Kircheis R, Haasbach E, Lueftenegger D, Heyken WT, Ocker M, Planz O. NF-κB pathway as a potential target for treatment of critical stage COVID-19 patients. Front Immunol . 2020;11:598444. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.598444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Poppe M, Wittig S, Jurida L, Bartkuhn M, Wilhelm J, Müller H, et al. The NF-κB-dependent and -independent transcriptome and chromatin landscapes of human coronavirus 229E-infected cells. PLoS Pathog . 2017;13:e1006286. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1006286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. RECOVERY Collaborative Group. Dexamethasone in hospitalized patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med . 2021;384:693–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2021436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tomazini BM, Maia IS, Cavalcanti AB, Berwanger O, Rosa RG, Veiga VC, et al. COALITION COVID-19 Brazil III Investigators Effect of dexamethasone on days alive and ventilator-free in patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome and COVID-19: the CoDEX randomized clinical trial. JAMA . 2020;324:1307–1316. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Sterne JAC, Murthy S, Diaz JV, Slutsky AS, Villar J, Angus DC, et al. WHO Rapid Evidence Appraisal for COVID-19 Therapies (REACT) Working Group Association between administration of systemic corticosteroids and mortality among critically ill patients with COVID-19: a meta-analysis. JAMA . 2020;324:1330–1341. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.17023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Zhou Z, Duerr J, Johannesson B, Schubert SC, Treis D, Harm M, et al. The ENaC-overexpressing mouse as a model of cystic fibrosis lung disease. J Cyst Fibros . 2011;10(Suppl 2):S172–S182. doi: 10.1016/S1569-1993(11)60021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Livraghi-Butrico A, Kelly EJ, Wilkinson KJ, Rogers TD, Gilmore RC, Harkema JR, et al. Loss of Cftr function exacerbates the phenotype of Na+ hyperabsorption in murine airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol . 2013;304:L469–L480. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00150.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]