Abstract

Urban protected areas are an important resource to people and wildlife, providing many ecosystem services. During the initial phase of the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown during March–June 2020, there was a major increase in the number of hikers and bicyclists in urban protected areas, including the Webster Woods in Newton, Massachusetts (USA), an 82.5-ha protected area. The Webster Woods is one of the largest protected areas near the center of Boston and is widely used in conservation textbooks as an example of the effects of habitat fragmentation on the amount of undisturbed habitat. Prior to the pandemic, the Webster Woods had been extensively fragmented by paved roads, dirt roads, and trails, with little interior habitat remaining. During the first four months of the pandemic, hikers and bicyclists made 4.9 km of new social (or informal) trails, an increase of 36%. This recent fragmentation represents a dramatic increase in the level of human impact on the area, reducing the amount of interior habitat from 3.2 to 2.1 ha. Levels of human activity returned to pre-pandemic levels in autumn 2020 and city officials have started closing access to some of the new trails, allowing vegetation to regrow. It is possible that similar increases in social trails and associated fragmentation have occurred in other protected areas (especially those in urban areas) around the world due to the pandemic, and these disturbances should be evaluated for their effects on plant and animal populations.

Keywords: Social trails, Habitat fragmentation, COVID-19, Protected areas, Urban park

1. Introduction

Urban protected areas provide essential ecosystem services, creating habitat for local wildlife as well as opportunities for people to observe and enjoy nature (Secretariat of the CBD 2008; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment 2005; Mexia et al. 2018). The importance of urban protected areas was illustrated dramatically during the COVID-19 pandemic when city residents crowded into nearby protected areas to relax and exercise (Rushing 2020; Adler and Hendricks 2020). In some parts of the world, managers had to close urban protected areas to prevent over-crowding, virus transmission, and damage to the parks (Friedman et al. 2020).

With greater visitation to parks during the pandemic, hikers and walkers widened paths as people tried to avoid close contact (Primack, personal observation; Miller-Rushing, personal observation). Hikers and bicyclists also began to make new paths, perhaps as a way to avoid crowded existing trails and to explore and experience new areas. It is unknown to what extent these new social trails (i.e., informal trails created casually or deliberately by foot or bike traffic) increased the degree of fragmentation of urban protected areas, if these trails are temporary or permanent, or if government agencies need to take action to close these social trails.

Social trails are considered problematic in many protected areas because they can damage sensitive vegetation, increase erosion, alter microclimates and increase fragmentation (Wimpey and Marion 2011; Ballantyne and Pickering 2015; Barros and Pickering 2017; Havlick et al. 2016; Lucas 2020). Habitat fragmentation created by social trails can have unintended negative consequences for wildlife and other aspects of biodiversity (Corlett et al. 2020; Rutz et al. 2020; Bates et al. 2020) by reducing habitat, altering environmental conditions, and inhibiting the movement of species (Saunders et al. 1991; Haddad et al. 2015; Fahrig 2017; Laurance et al., 2007, Laurance et al., 2011). The edges of social trails can provide entry points for invasive species. People and dogs walking on social trails can also disturb wildlife, particularly during times of reproduction (Miller et al. 1998; Reed and Merenlender 2011; Bötsch et al. 2018).

The Webster Woods, in Newton, Massachusetts (USA) represents a case study of the creation of new social trails and fragmentation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Changes in the trail system, including social trails, have been well mapped over the past 50 years, so new social trails can be readily identified and compared to past changes in trails. The vegetation of the Woods is predominantly deciduous oak-maple forest with abundant deciduous ericaceous shrubs and scattered wildflowers. It is likely that increased fragmentation of the Woods will result in some species increasing and others decreasing in abundance as the amount of edge habitat increases and the amount of interior habitat decreases. A past field study from these Woods demonstrated that bumblebees foraging on flowering shrubs only rarely crossed a road, even though they were capable of doing so (Bhattacharya et al. 2003). The Webster Woods is also an interesting case because it provides the basis for the idealized model park used in several university textbooks to illustrate the effects of habitat fragmentation on undisturbed habitats (for example, Primack 1993; Sher and Primack 2019).

In this study, we use the Webster Woods as a case study to address two questions: (1) How much has the trail network increased during the COVID-19 pandemic? (2) How much has habitat fragmentation increased during the COVID-19 pandemic? The results of this analysis can be used to suggest ways to manage this area to reduce the effects of fragmentation and can stimulate researchers to investigate the impacts of COVID-19 on other protected areas around the world, particularly those in urban areas.

2. Methods

2.1. Study site

The study site comprises the undeveloped woodland known as the Webster Woods (also sometimes known as the Hammond Woods), in Newton, Massachusetts, in metropolitan Boston. The Woods constitute an area of 82.5 ha, and parcels of it are owned by the City of Newton and the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. The area is contained within a five-sided block of busy urban roads. Within the area bounded by these roads are residential neighborhoods, with the Webster Woods in the undeveloped interior. The Webster Woods likely remained undeveloped due to the difficult-to-develop landscape of rock outcrops and ledges, surface boulders, swamps, and thin soil.

The Woods are transected east-to-west by a commuter railroad and north-to-south by a four-lane highway (Fig. 1 ). Also present in the Woods, bordering the highway, is a former synagogue, built in 1957, and its irregularly shaped parking lots. The railroad and highway divide the Woods into four unequal parts. Within each of these parts, the area is further divided by: (1) dirt roads, essentially wide paths, all established prior to 1972, (2) hiking trails established prior to 1972, and (3) social trails created between 1972 and 2019. Between March and June 2020, state health regulations and recommendations limited travel and indoor school and business activities, including the uses of commercial gyms, in Massachusetts. During this time, the number of people walking and using trail bikes in the woods increased substantially, in the process creating more social trails in the Woods. Some of the new trails appear to have been deliberately created by trail bikers to enter new parks of the Woods and to experience steep terrain. These new trails are predominantly about 1 m wide, but can vary from 0.3 to 2 m wide, and many of them have exposed soil and often significant erosion. After June 2020, the number of visitors to the Woods substantially declined, though numbers were still somewhat above pre-pandemic levels, and no new trails were created.

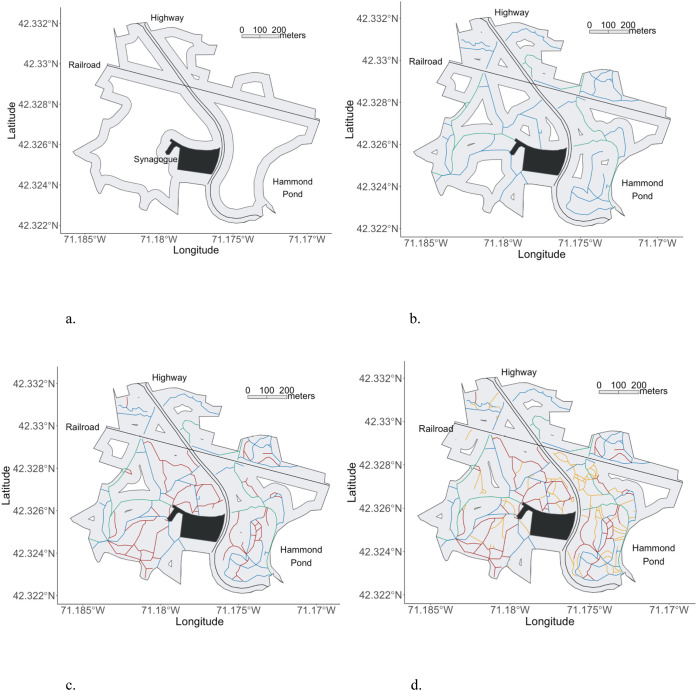

Fig. 1.

Maps of the Webster Woods, Newton, MA, with grey areas indicating the regions within 50 m of an edge. A. Showing the boundaries, railroad, highway, and synagogue (the whole property shown in black). B. With the addition of dirt roads (green) and trails (blue) as of 1972. C. with the addition of new trails as of 2019 (red). D. with the addition of new trails as of 2020 (orange). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

2.2. Mapping the trails

We mapped the dirt roads and trails (including social trails) using a detailed topographic map, official trail maps, and personal field notes. We mapped the trails that existed in three different years: 1972, 2019, and 2020. In addition, in 1971 and 1972 the flora of the Webster Woods was inventoried, creating a detailed account of the Woods, including the dirt roads and trails (Primack 1972).

2.3. Analyzing fragmentation

We analyzed fragmentation of the Webster Woods using the following five snapshots:

-

1.

Before the establishment of the railroad, highway, and synagogue (and its associated parking lots)

-

2.

Establishment of the railroad, highway, and synagogue (and its associated parking lots)

-

3.

Railroad, highway, synagogue, dirt roads, and trails in 1972

-

4.

Railroad, highway, synagogue, dirt roads, and trails in 2019

-

5.

Railroad, highway, synagogue, dirt roads, and trails in July 2020

Whenever we refer to the synagogue in our analysis, we are referring to the entire property, which includes the building and parking lots.

For each snapshot, we calculated the following:

-

•

The length of the boundary around the Woods, both prior to fragmentation and after the establishment of the railroad, highways, and synagogue

-

•

The length of the dirt roads and trails

-

•

The area of edge habitat, using a 50-m buffer extending from the boundary of the Woods and on either side of dirt roads and trails

While different edge effects can vary considerably in the distance they penetrate into adjacent undisturbed habitat, research on habitat fragmentation suggests that microclimate and ecological effects are most pronounced within 50 m of forest edges (Laurance et al. 2011).

We initially used Google Maps to delineate trails, park outline, highway, railroad, and synagogue boundary. We then exported the maps as KML files and analyzed them using R version 3.5.2 (R Core Team 2018). We analyzed the data using the packages sf and units (Pebesma 2018; Pebesma et al. 2016), and created maps using ggplot2 (Wickham 2016).

3. Results

3.1. How much has the trail network increased during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Due to its irregular shape, the boundary of the Webster Woods—without the highway, railroad, and synagogue—is 5585 m (Table 1 ). The combined outlines of the parkway, railroad, and synagogue have a total length of 3089 m, and divide the Webster Woods into four parts. The dirt roads and trails in the Woods in 1972 had a length of 8409 m. Between 1972 and 2019, an additional 5348 m of social trails had been added by hikers and bicyclists, bringing the total length of dirt roads and trails to 13,757 m. During the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, 4948 m of new social trails were created, an increase of 36%. During the four months of the pandemic, almost as many new social trails were created as had been created during the previous 48 years.

Table 1.

The length of boundaries, the length of dirt roads and trails, and the area of interior habitat that existed at five different snapshots in time. The area of interior habitat is calculated with a 50 m buffer.

| Snapshot time period | Individual length (m) |

Total length (m) | Interior habitat (ha) | Interior habitat (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boundaries: | ||||

| Prior to fragmentation | 5585 | 5585 | 61.0 | 71.3 |

| After establishment of railroad, parkway, synagogue | 3089 | 8674 | 37.4 | 43.7 |

| Dirt roads and trails: | ||||

| 1972 | 8409 | 8409 | 8.2 | 9.5 |

| 2019 | 5348 | 13,757 | 3.2 | 3.7 |

| 2020 | 4948 | 18,705 | 2.1 | 2.4 |

3.2. How much has fragmentation increased during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Considering only the boundaries of the Webster Woods and using a 50-m buffer, 61 ha (71.3%) of the Webster Woods is interior habitat (Table 1). When we add the railroad, highway, and synagogue, the Woods has 37.4 ha (43.7%) interior habitat. When we add the dirt roads and trails that existed in 1972, the amount of interior habitat declines to 8.2 ha (9.5%). Interior habitat declines to 3.2 ha (3.7%) when we add dirt roads and trails that existed in 2019, and to 2.1 ha (2.4%) when we add new social trails created in 2020.

4. Discussion

Beginning in March 2020, the number of hikers and bicyclists in the Webster Woods increased substantially, leading to the creation of roughly 5 km of new social trails. This represents an increase of 36% over the 14-km trail network that existed in 2019. The length of new social trails created during the first four months of the pandemic was comparable to the length of new social trails created in the 47 years from 1972 to 2019. Because the Woods were already so fragmented as of 2019, these new trails created during the pandemic had relatively little impact on the amount of interior habitat. This would likely also be the case in other small protected areas that might have experienced similar amounts of social trail creation. However, larger protected areas (e.g., urban parks like Middlesex Fells in Boston or Stanley Park in Vancouver) could have experienced greater declines in interior habitat area. While we focus on trail length and fragmentation in our analysis, these new trails would have also had the effect of decreasing habitat connectivity and increasing habitat isolation.

In this study, for convenience we treated all boundaries, trails, dirt roads, the highway, and the railroad as equivalent in their contributions to fragmentation and impacts on interior habitat. This is certainly an over-simplification. The highway is the noisiest place. The asphalt surface and cars dramatically alter the microclimate near the road. The railroad is very loud when trains pass and is bordered by a chain link fence that prevents the movement of large ground-dwelling animals. Trails and dirt roads alter microclimate conditions the least, but they were used extensively during the pandemic by joggers, mountain bikers, and dog walkers—with many dogs off leash—which can alter the behaviors of wildlife and hikers (Reed and Merenlender, 2008, Reed and Merenlender, 2011; Davis et al. 2010; Reilly et al. 2017; Bötsch et al. 2018). This increased level of fragmentation might also alter the sense of tranquility that many people seek when they visit an urban park.

Many new social trails appeared to result from teenagers and young adults using mountain bikes to access isolated areas of the park and steeper terrain. As the pandemic restrictions began to ease in July 2020 and when signs prohibiting biking in the woods were posted, the level of mountain biking in the woods appeared to diminish (personal observation). By the end of 2020, the number of walkers and bicyclists in the woods appeared to be far below the March–June levels, and no additional social trails were created. The second wave of COVID-19 restrictions in December 2020 did not appear to result in an increase in visitors to the Woods, possibly due to the colder weather (daytime temperatures regularly around 0 degrees C) dampening some people's willingness to walk and bike outside.

With the arrival of autumn and winter 2020, a layer of fallen leaves and snow covered the woodland floor. It is possible that many of the new trails created in 2020 will disappear and will no longer be used. However, some of these social trails continue to be used, even through autumn and winter, and will likely persist, especially where they extend the trail system into previously inaccessible areas and provide convenient short cuts between older trails.

The Newton Conservation Commission has implemented management options to close certain new social trails that are perceived to be particularly damaging because they have increased erosion on steep slopes. Actions being taken include blocking entry points with fallen tree limbs and rock walls and posting signs saying trails are closed. The Commission is also considering allowing certain social trails to remain, where they improve visitor flow and access. The recovery of the disused and closed trails will likely take at least several years in places via the re-sprouting of low ericaceous shrubs where they have been damaged. Active plant restoration is probably not needed at this site.

Our findings suggest that during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in Massachusetts, USA, this urban protected area experienced dramatic increases in social trail creation and fragmentation because of unusually heavy use for recreation and exercise. We present just one case study, but anecdotal reports from other protected areas suggest this might be a widespread phenomenon in other urban parks (O'Neill, personal observation) and national parks (Miller-Rushing, personal observation). It is possible that other parks might have experienced reduced visitor usage due to more restricted pandemic lockdowns and parks being closed to public access, which may have reduced social trail creation. We suggest that researchers and managers investigate expansion of social trails in other protected areas and take the opportunity to assess impacts to microclimate, human recreational use, plant populations, and wildlife behavior. We also recommend that researchers and managers assess methods for closing social trails and restoring native habitats. Parks elsewhere might also have experienced other changes in human activity, such as increased recreational fishing, increased dog-walking, decreased trail maintenance by volunteers, and decreased removal of invasive plant species, which should be examined for their ecological and conservation impacts.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Richard Primack: all project aspects; Carina Terry: formal analysis, visualization, validation, writing – review and editing.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors of this paper certify that they have NO conflicts of interests associated with the creation and publication of this manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Jennifer Steel and Doug Greenfield of the City of Newton for advice and maps. Tara Miller, Abraham Miller-Rushing, and Lucy Zipf provided helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

- Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2008. Protected Areas in Today's World: Their Values and Benefits for the Welfare of the Planet. Montreal, Technical Series, no. 36, i-vii + 96.

- Wimpey J., Marion J.L. A spatial exploration of informal trail networks within Great Falls Park, VA. J. Environ. Manag. 2011;92:1012–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adler E., Hendricks M. Safe? KC Park Is Packed Even as COVID-19 Crisis Pushes Social Distancing. 2020. www.kansascity.com/news/coronavirus/article241529276.html Kansas City Star.

- Ballantyne M., Pickering C.M. Differences in the impacts of formal and informal recreational trails on urban forest loss and tree structure. J. Environ. Manag. 2015;159:94–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2015.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros A., Pickering C.M. How networks of informal trails cause landscape level damage to vegetation. Environ. Manag. 2017;60:57–68. doi: 10.1007/s00267-017-0865-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates, A.E., Primack, R.B., Moraga, P., Duarte, C.M., 2020. COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown as a “global human confinement experiment” to investigate biodiversity conservation. Biological conservation, 108665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bhattacharya M., Primack R.B., Gerwein J. Are roads and railroads barriers to bumblebee movement in a temperate suburban conservation area? Biol. Conserv. 2003;109:37–45. [Google Scholar]

- Bötsch Y., Tablado Z., Sheri D., Kéry M., Graf R.F., Jenni L. Effect of recreational trails on forest birds: human presence matters. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018;6:175. doi: 10.3389/fevo.2018.00175. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team, 2018. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. www.R-project.org/.

- Corlett R.T., Primack R.B., Devictor V., Maas B., Goswami V.R., Bates A.E., Koh L.P., Regan T.J., Loyola R., Pakeman R.J. Impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on biodiversity conservation. Biol. Conserv. 2020;246:108571. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis C.A., Leslie D.M., Jr., Walter W.D., Graber A. Mountain biking trail use affects reproductive success of nesting golden-cheeked warblers. Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 2010;122(3):465–474. [Google Scholar]

- Fahrig L. Ecological responses to habitat fragmentation per se. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2017;48:1–23. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110316-022612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freidman W., Allen J.G., Lipsitch M. Keep parks open. The benefits of fresh air outweigh the risks of infection. Washington Post. 2020;(April 13, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Haddad N.M., Brudvig L.A., Clobert J., Davies K.F., Gonzalez A., Holt R.D., Lovejoy T.E., Sexton J.O., Austin M.P., Collins C.D., Cook W.M., Damschen E.I., Ewers R.M., Foster B.L., Jenkins C.N., King A.J., Laurance W.F., Levey D.J., Margules C.R., Melbourne B.A., Nicholls A.O., Orrock J.L., Song D.-X., Townshend J.R. Habitat fragmentation and its lasting impact on Earth’s ecosystems. Sci. Adv. 2015;1 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havlick D.G., Billmeyer E., Huber T., Vogt B., Rodman K. Informal trail creation: hiking, trail running, and mountain bicycling in shortgrass prairie. J. Sustain. Tour. 2016 doi: 10.1080/09669582.2015.1101127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laurance W.F., Nascimento H.E., Laurance S.G., Andrade A., Ewers R.M., Harms K.E., Luizão R.C., Ribeiro J.E. Habitat fragmentation, variable edge effects, and the landscape-divergence hypothesis. PLoS One. 2007;2(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurance W.F., Camargo J.L., Luizão R.C., Laurance S.G., Pimm S.L., Bruna E.M., Stouffer P.C., Williamson G.B., Benítez-Malvido J., Vasconcelos H.L., Van Houtan K.S., Zartman C.E., Boyle S.A., Didham R.K., Andrade A., Lovejoy T.E. The fate of Amazonian forest fragments: a 32-year investigation. Biol. Conserv. 2011;144:56–67. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2010.09.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas E.K. California Fish and Wildlife; Recreation Special Issue: 2020. A Review of Trail-related Fragmentation, Unauthorized Trails, and Other Aspects of Recreation Ecology in Protected Areas; pp. 95–125. [Google Scholar]

- Mexia T., Vieira J., Príncipe A., Anjos A., Silva P., Lopes N., Freitas C., Santos-Reis M., Correia O., Branquinho C., Pinho P. Ecosystem services: urban parks under a magnifying glass. Environ. Res. 2018;160:469–478. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millennium Ecosystem Assessment . Island Press; Washington, DC: 2005. Ecosystems and Human Well-being: Synthesis. [Google Scholar]

- Miller S.G., Knight R.L., Miller C.K. Influence of recreational trails on breeding bird communities. Ecol. Appl. 1998;8:162–169. doi: 10.2307/2641318. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pebesma, E., 2018. Simple features for R: standardized support for spatial vector data. The R Journal 10 (1), 439-446, doi:10.32614/RJ-2018-009.

- Pebesma, E., Mailund, T., Hiebert, J., 2016. Measurement units in R. The R Journal 8(2), 486–494. doi:10.32614/RJ-2016-061.

- Primack, R.B., 1972. The changing flora of the Hammond Woods. Harvard University, unpublished undergraduate thesis.

- Primack R.B. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 1993. Essentials of Conservation Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Reed S.E., Merenlender A.M. Quiet, nonconsumptive recreation reduces protected area effectiveness. Conserv. Lett. 2008;1:146–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-263X.2008.00019.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed S.E., Merenlender A.M. Effects of management of domestic dogs and recreation on carnivores in protected areas in northern California. Conserv. Lett. 2011;25:504–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01641.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reilly M.L., Tobler M.W., Sonderegger D.L., Beier P. Spatial and temporal response of wildlife to recreational activities in the San Francisco Bay ecoregion. Biol. Conserv. 2017;207:117–126. [Google Scholar]

- Rushing E. Illegal Parking, Public Defecation, Overflowing Trash Cans: Crowds Cause Mess at Parks During Coronavirus Pandemic. 2020, April 3. www.inquirer.com/news/coronavirus-covid-19-state-national-parks-closed-crowded-social-distancing-valley-forge-20200403.html?__vfz=medium%3Dsharebar The Philadelphia Inquirer.

- Rutz C., Loretto M.-C., Bates A.E., Davidson S.C., Duarte C.M., Jetz W., Johnson M., Kato A., Kays R., Mueller T. COVID-19 lockdown allows researchers to quantify the effects of human activity on wildlife. Nature Ecology & Evolution. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41559-020-1237-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders D.A., Hobbs R.J., Margules C.R. Biological consequences of ecosystem fragmentation: a review. Conserv. Biol. 1991;5:18–32. www.jstor.org/stable/2386335?origin=JSTOR-pdf [Google Scholar]

- Sher A.A., Primack R.B. Second edition. Sinauer Associates; Sunderland, MA: 2019. An Introduction to Conservation Biology. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H., 2016. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag, New York, New York.