Abstract

Background:

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique challenge for pharmacists as they navigated information scarcity on the frontlines while being identified as information experts. Alberta pharmacists looked to their professional organizations for direction regarding what their roles should be in a crisis. The objective of this study was to explore pharmacists’ roles and services and how they were communicated by pharmacy organizations during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

The study used a conventional content analysis method to explore the online communication of relevant pharmacy organizations for Alberta pharmacists. Five organization websites (National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities, Canadian Pharmacists Association [CPhA], Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists [CSHP], Alberta College of Pharmacy [ACP] and the Alberta Pharmacists’ Association [RxA]) were examined to identify and catalogue publicly accessible documents that communicated pharmacists’ roles and services during the first year of the pandemic for Alberta pharmacists.

Results:

A total of 92 documents were collected from CPhA (60), CSHP (2), ACP (26) and RxA (4). While most documents communicated information about pharmacists’ roles in public health, patient care and drug and personal protective equipment supply, more than one-third of the documents (32/92, 34.8%) required contextual information to interpret the communication. There was an observed shift in the communication after the first 6 months, becoming more direct in its messaging and context.

Conclusion:

These pharmacy organizations communicated information for pharmacists’ roles and services to provide direction and guidance in the ever-changing context of the COVID-19 pandemic for Alberta pharmacists. Their communication became clearer and more direct as the pandemic progressed, requiring less inference to understand the intended message.

Knowledge into Practice.

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique challenge for pharmacists as they navigated information scarcity on the frontlines and rapidly changing policies.

To navigate the rapidly changing information landscape of this unprecedented pandemic, professional pharmacy organizations communicated information to Alberta pharmacists regarding their roles and services.

Pharmacists responding to disasters and emergencies typically revert to novice proficiency level, requiring additional instruction and guidance to help navigate their actions and response in the new context.

There was an observed shift and confidence in the pharmacy organizations’ communication as the pandemic progressed past the first 6 months, with the communication becoming more direct and clearer in its messaging and context.

Introduction

Historically, pharmacists have been recognized and accepted as drug experts, but this was expanded during the COVID-19 pandemic, as pharmacists were identified as a trusted and reliable information source for guidance, education and policy.1-3 Pharmacists were integral in these conversations with patients and community members as they navigated various challenges and policy changes.2,4

Pharmacists were affected by several key policy changes and challenges during the first 12 months of the pandemic. Initially, supply was a major theme, with pharmacists struggling to access personal protective equipment (PPE) for their staff or patients and policy changes regarding pharmacists rationing medication dispensing. 4 This rationing was done in an effort to preserve the supply chain and ensure ongoing equitable access. In addition, policy around pharmacists’ prescribing of narcotics was temporarily expanded to maintain patients’ access to chronic pain medications.5,6 The next major change for pharmacists as the pandemic evolved was their service as asymptomatic testing sites for COVID-19 infections. 7 Vaccinations became another significant challenge for both the changes required for the routine influenza season vaccinations and the new vaccines that became available to protect against COVID-19 infections. 4 The new vaccines and emerging COVID treatments came with informational challenges for pharmacists as they navigated the evolving research and battled the misinformation “infodemic.” 8

Evidence for pharmacists’ involvement on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic exists,1-4,9-18 but how pharmacy organizations communicated information about pharmacists’ roles during the pandemic has yet to be explored. The objective of this study was to explore what pharmacists’ roles and services were and how those were communicated during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Mise En Pratique Des Connaissances.

La pandémie de la COVID-19 a présenté un défi unique pour les pharmaciens, qui ont dû faire face à une pénurie d’informations en première ligne et à l’évolution rapide des politiques.

Pour composer avec l’évolution rapide du paysage de l’information de cette pandémie sans précédent, les organisations pharmaceutiques professionnelles ont communiqué aux pharmaciens de l’Alberta des informations sur leurs rôles et services.

Les pharmaciens qui font face à des catastrophes et des urgences reviennent généralement à un niveau de compétence débutant, et nécessitent des instructions et des conseils supplémentaires pour les guider dans leurs actions et leurs interventions dans le nouveau contexte.

On a observé un changement et une plus grande confiance dans la communication des organisations pharmaceutiques à mesure que la pandémie progressait après les 6 premiers mois; la communication est devenue plus directe et plus claire dans son message et son contexte.

Methods

Study design

A conventional content analysis was performed using a systematic approach in reviewing and evaluating documents. 19 Alberta was selected as a province of interest for its established advanced scope of pharmacy practice and the location of the researchers.

Pharmacy organizations

Specific to the pharmacy profession in Alberta, there are 5 pharmacy organizations that provide direction and information to frontline pharmacists, the public and governments. Two represent regulatory bodies, the National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities (NAPRA) and the Alberta College of Pharmacy (ACP), and 3 advocacy bodies, the Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA), the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP) and the Alberta Pharmacists’ Association (RxA). The regulatory bodies serve to protect the public and regulate pharmacy practice at the national and provincial level.20,21 The advocacy bodies differ in focus, with CSHP being specific to pharmacists and technicians in the national hospital pharmacy practice setting and CPhA and RxA being more specific to community pharmacists, pharmacy technicians and pharmacies at the national and provincial level, respectively.22-24

Data collection, extraction and analysis

A manual search of 5 pharmacy organization websites was conducted to extract publicly accessible written documents (e.g., statements, guidance, frequently asked questions and news articles) related to pharmacists’ roles and services during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. Websites and webpages were chosen as sources of documents for their accessibility, ability to rapidly respond to the changing pandemic landscape and the broad range of possible audiences (e.g., governments, public and pharmacy personnel). A systematic strategy was used that included using specific search terms (“pharmacist,” “COVID-19,” “coronavirus,” “role,” “service,” “pandemic,” “scope of practice”) to screen webpages. In addition, a manual review of relevant sections of the pharmacy organizations’ webpages (e.g., news/advocacy pages, specific COVID-19 information pages, etc.) was undertaken to ensure no documents were missed. The specific search terms were piloted prior to the official screening to ensure the search terms used would capture all relevant documents.

The websites were reviewed by one of the researchers (C.S.) between February 1 and March 15, 2021, and documents were screened for eligibility. Documents were included if they were publicly accessible, published during the first year of the pandemic (March 11, 2020–March 15, 2021) and referred to pharmacists’ roles and services. Documents that were presented in alternative media types (e.g., surveys, webinars, video content, etc.), did not explicitly refer to the pandemic or pharmacists’ roles or were not endorsed by the organization were excluded from this study. Webpages were captured and saved as documents to preserve the information that was reviewed and included in this study at time of data collection.

Data extraction was performed using a predefined and piloted template in Microsoft Excel. An inductive approach was used to analyze the roles and services described in the documents. A deductive approach was used to analyze communication style. Communication was evaluated for its positivity of pharmacists’ undertaking the role and directness, meaning that no inference was required to explicitly understand what was being communicated. A second team member (M.L.A. or K.E.W.) reviewed 30% of the identified documents for consistency of data collected, extracted and analyzed.

Results

Documents

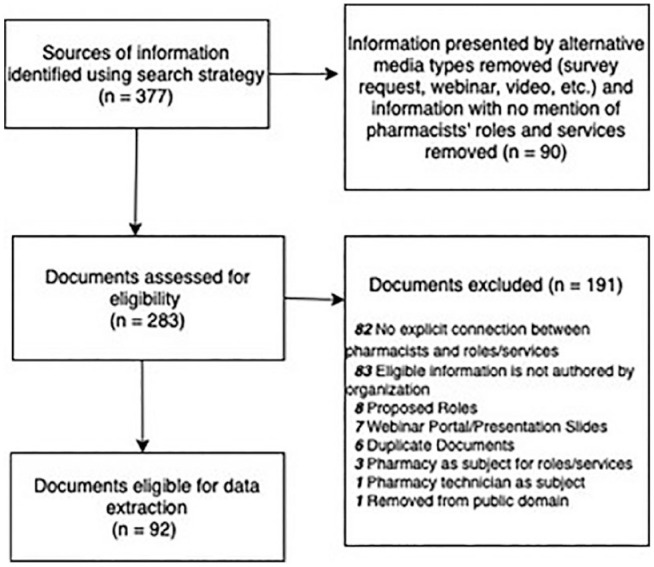

The initial search identified 377 sources of information, of which 283 written documents were captured and screened for eligibility (Figure 1). Of these, 92 documents met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis.

Figure 1.

Document-screening process

The baseline characteristics of the 92 documents are displayed in Table 1. Notably, none of the information published by NAPRA was publicly accessible, and only 2 documents by CSHP were publicly accessible on their website. There was an almost even split between documents published in the first and second 6-month study period (44 and 45, respectively). The documents mostly targeted pharmacists and pharmacy staff as their audience (71/92, 77.2%), with few being generalized for public (17/92, 18.5%) or government (4/92, 4.3%) audiences.

Table 1.

Characteristics of publicly accessible documents included in the study

| % (N = 92) | |

|---|---|

| Organization | |

| NAPRA | 0 (0) |

| CSHP | 2.2 (2) |

| CPhA | 65.2 (60) |

| ACP | 28.3 (26) |

| RxA | 4.3 (4) |

| Timing of publication | |

| First 6 months of the pandemic (March 4, 2020–September 1, 2020) | 46.7 (43) |

| Second 6 months of the pandemic (September 1, 2020–March 15, 2021) | 50 (46) |

| Date not specified | 3.3 (3) |

| Audience | |

| Pharmacists and pharmacy staff | 77.2 (71) |

| Government | 4.3 (4) |

| Public | 18.5 (17) |

ACP, Alberta College of Pharmacy; CPhA, Canadian Pharmacists Association; CSHP, Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists; NAPRA, National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities; RxA, Alberta Pharmacists’ Association.

Communication of roles and services

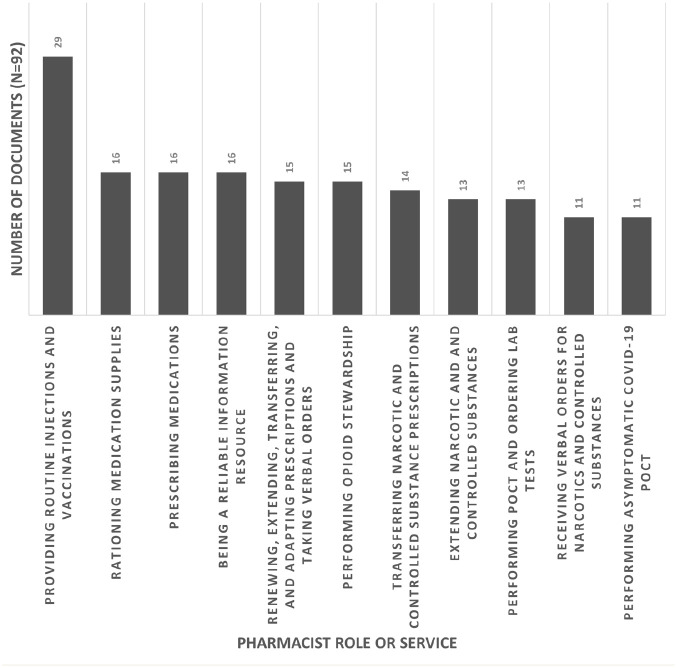

The top 10 roles and services communicated by the pharmacy organizations during the first year of the pandemic are highlighted in Figure 2. The top 10 roles and services included narcotic prescribing (receiving verbal orders, extending and transferring prescriptions and opioid stewardship), point-of-care testing (POCT), asymptomatic COVID-19 testing, pharmacist prescribing (independent prescribing, renewing, extending, transferring and accepting verbal orders), rationing medication supplies, providing routine injections and vaccinations and being a reliable information resource (Figure 2), with the highest role/service being routine vaccinations (e.g., influenza vaccine for the flu season).

Figure 2.

Top 10 most frequently described roles performed by pharmacists communicated by pharmacy organizations during COVID-19 subdivided by organization communicating the role

*POCT, point-of-care testing.

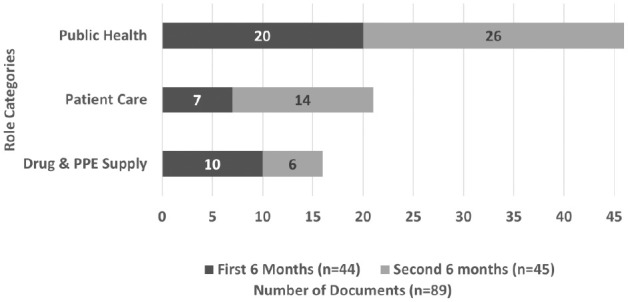

The roles were further grouped into 3 categories: public health, patient care and drug and PPE supply (Figure 3). There was a noticeable increase in pharmacists’ public health and patient care roles mentioned as the pandemic surpassed the first 6 months from 45.5% (20/44) to 57.8% (26/45) and 15.9% (7/44) to 31.1% (14/45), respectively. Contrastingly, as the supply chains began to stabilize, communication of pharmacists’ roles in drug and PPE supply decreased. Three documents did not specify the date written and were excluded from this subcategorization.

Figure 3.

An observed shift in the frequency of roles mentioned from the first 6 months (March-August 2020) to the second 6-month period (September 2020–February 2021)

The analysis indicates that pharmacists’ roles and services were not new for Alberta pharmacists. For example, pharmacists already educated their patients on medications, provided vaccination services, prescribed medications, provided POCT and critically appraised new research and evidence. 2 However, what was new was the context in which these roles were being performed.

Communication style

In just under half (44/92, 47.8%) of the documents, communication was positive and empowering of pharmacists’ stepping up to meet the needs of society by providing their roles and services (Table 2). The other large proportion (43/92, 46.7%) of the documents conveyed a neutral and factual communication tone. Only 5 documents used cautionary language in their mention of pharmacists’ roles and services. Overall, the frequency of direct communication increased from 50% (22/44) of the documents in the first 6 months to 77.8% (35/45) in the second 6-month period.

Table 2.

Pharmacy organizations’ communication

| Communication of pharmacists’ roles and services | Total, % (N = 92) | CPhA, % (n = 60) | CSHP, % (n = 2) | ACP, % (n = 26) | RxA, % (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (e.g., “Managing Canada’s drug supply has required an extraordinary effort, expertise and care by pharmacy teams under the most difficult of circumstances.” [CPhA]) 25 | 47.8 (44) | 60 (36) | 100 (2) | 15.4 (4) | 50 (2) |

| Neutral (e.g., “Regulated members must take reasonable steps to maintain a secure drug supply.”[ACP]) 26 | 46.7 (43) | 35 (21) | 0 (0) | 76.9 (20) | 50 (2) |

| Cautionary (e.g., “Over 60% of pharmacists are extremely or very concerned about their safety and the safety of pharmacy staff during COVID-19. Access to appropriate PPE could help to alleviate these concerns, but supplies of PPE remain limited across Canada.” [CPhA])27,28 | 5.4 (5) | 5 (3) | 0 (0) | 7.7 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Directness of communication | |||||

| Inference required (e.g., “Pharmacies are working around the clock to ensure that Canadians are safe with respect to medication use and timely access to medications.” [CPhA]) 29 | 34.8 (32) | 40 (24) | 0 (0) | 30.8 (8) | 0 (0) |

| Clear and direct (e.g., “Authorized pharmacists can make a difference in the fight against COVID-19 by using their skills to help with crucial tasks such as vaccine administration and education.” [ACP]) 30 | 65.2 (60) | 60 (36) | 100 (2) | 69.2 (18) | 100 (4) |

ACP, Alberta College of Pharmacy; CPhA, Canadian Pharmacists Association.

While pharmacists’ roles and services did not change, the context in which they were performed was continually evolving with the ongoing and prolonged nature of the COVID-19 pandemic. More than one-third of the documents (32/92, 34.8%) required contextual knowledge to fully interpret the communication. For example, although drug shortages predated the pandemic, in response to the rapidly evolving instability in supply chains due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a policy change was introduced across Canada to ration medication supplies and limit dispensing from 100-day to 30-day quantities, 31 with pharmacists being on the frontline of actioning this policy change. The quote below highlights the messaging about this pharmacist’s role in rationing medication supplies to ensure equitable access and its communication to the public. However, for a general audience, it requires inference and context to understand the implications of this policy change for people getting their medications dispensed by pharmacists at pharmacies.

In the last few weeks, pharmacists have seen a tremendous surge in demand for medical supplies and medications as a result of the evolving and ongoing COVID-19 crisis. As a result, it has become necessary for pharmacies to carefully manage their medication inventories to protect against the real risk of shortages during this critical period. This is a temporary but necessary measure. (CPhA) 32

Another finding was the use of pharmacy as a synonym for pharmacist. Our analysis revealed instances of metonymic slippage, a figure of speech in which an object or concept is referred to by an attribute or object closely associated with it rather than its own name. Inference was required to identify that the document is referring to pharmacists’ roles and services and not the pharmacy. Pharmacies are brick-and-mortar buildings in which patients can access health care from pharmacists. Pharmacists are licensed health care providers who can practise in any setting, including outside the community pharmacy premise. For example, in the quote below, pharmacies do not administer tests; pharmacists and pharmacy staff perform this role.

Pharmacies in Alberta and in parts of the United States are now permitted to administer some types of tests for COVID-19. (CPhA) 33

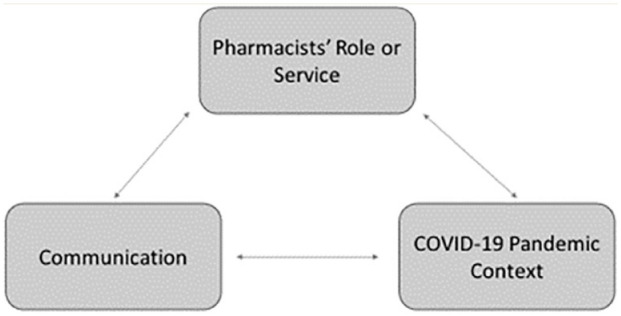

Conceptual framework

To frame pharmacy organizations’ communication of pharmacists’ roles and services during the first 12 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, we developed the conceptual framework model highlighted in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Conceptual framework model of communication of pharmacists’ roles and services during the COVID-19 pandemic

This conceptual framework can be applied by pharmacists to guide action when receiving communications from pharmacy organizations. Three examples from this study using the conceptual framework model are presented in Table 3. In example 1, the pharmacists’ role of managing and evaluating the appropriateness of narcotics had not changed, but the context surrounding this role to involve additional responsibility and authorization has been altered with the pandemic and the subsequent policy changes. Another issue that was prominent in the data was managing the influenza season amidst the COVID-19 pandemic (example 2, Table 3). Again, the specific pharmacist role and service of administering influenza vaccinations was not new. However, there was a need to communicate the logistics of providing this in-person service, balancing public safety and public health needs. To further provide evidence for the conceptual framework model, the third example illustrates the cautionary tone used to communicate the changing context of pharmacist referral documentation. Alberta pharmacists’ status as regulated health care professionals did not change with the pandemic. However, the context of the pandemic changed with the closure of massage services, and patients needed a referral to be able to access the services. The cautionary communication reinforced pharmacists’ need to self-assess their existing expertise, knowledge and scope of practice in response to patients’ request for referral for massage therapy. Thus, with the rapidly evolving pandemic and information landscape, communication of the contextual changes requiring referral or a prescription for health services was vitally important to patient care and safety.

Table 3.

Examples using the conceptual framework model

| Context | Role | Communication | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Example 1: Narcotic legislation changes | • Health Canada issued a temporary exemption to the

Controlled Drugs and Substances Act to address the overdose

crisis that was occurring simultaneously with the COVID-19

pandemic.5,34

This exemption allowed pharmacists flexibility in managing prescriptions for narcotics. 40 |

Changes allowed pharmacists to5,34,35

• extend or renew prescriptions for patients that were unable to get to their original prescribing provider. • take a verbal order from prescribers for prescriptions while many appointments were virtual or telehealth. • deliver controlled substances to patients that were unable to attend the pharmacy (e.g., people in quarantine or with increased health risk). |

“Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, temporary exemptions have been made under CDSA, creating an opportunity to provide continuity of care to some of the most vulnerable Canadians and helping us ensure their care is not interrupted, especially in times where they may be experiencing more stress, anxiety and isolation. . . . These exemptions permit pharmacists to care for their patients by extending prescriptions, transferring prescriptions to other pharmacists, receiving verbal orders and allowing pharmacy employees to deliver prescriptions of controlled substances to patients’ homes or other locations where they may be.” (CPhA) 36 |

| Example 2: Influenza vaccination season | • Providing an in-person vaccination service during an ongoing pandemic required additional considerations to keep personnel and the community safe (e.g., infection control, safety measures, etc.). | • Pharmacists were responsible for the mass vaccination

campaign during the influenza season amid the

pandemic. • This included using infection prevention and cleaning measures, scheduling appointments and avoiding walk-ins, fielding questions, patient screening for COVID infection, wearing appropriate PPE, administering vaccinations and completing documentation/postimmunization requirements. 37 |

“CPhA continues to promote importance of flu preparedness to avoid ‘twindemic’. Canadians are about to face yet another challenge in the COVID-19 pandemic: the arrival of flu season. . . . ‘About 35% of flu vaccinations in Canada are given by pharmacists each year,” says Shelita Dattani, director of practice development with the Canadian Pharmacists Association. She’s expecting that ‘as some family practice clinics have cut down on in-person appointments during COVID-19, pharmacists may be giving many more flu shots this year — and they’ve been preparing for months.’ ” (CPhA, inference required to understand the specific preparedness actions being undertaken by pharmacists) 38 |

| Example 3: Massage referral | • Massage therapy services closed to limit COVID-19

transmission. • An exemption was passed that allowed Albertans to access massage therapy with a written prescription from a medical doctor, or a written referral from a regulated health professional (e.g., physiotherapists and chiropractors). Albertans were requesting prescriptions to access the massage therapy service exemption. |

Pharmacists providing prescription and referral services as regulated health professionals with a responsibility to perform necessary physical assessments within their scope of practice. | “Regulated members who are considering making a referral must evaluate their own competencies and consider whether this request might be better channeled through the patient’s chiropractor, physiotherapist, or physician. As this is a public health measure designed to minimize the spread of COVID-19, regulated members considering a patient’s request for referral to access massage therapy services should consider the relative risk of massage therapy services against the need to reduce the spread of COVID-19. Regulated members who choose to issue a referral must only do so once they have established a professional relationship with the patient, assessed the patient and determined that a referral is in the best interest of the patient. Regulated members are reminded that they are required to avoid any conflicts of interest and declare any personal or professional interest with any massage therapist to any patient who may be affected.” (ACP) 39 |

ACP, Alberta College of Pharmacy; CDSA, Controlled Drugs and Substances Act; CPhA, Canadian Pharmacists Association; PPE, personal protective equipment.

Discussion

Disasters such as pandemics are chaotic events with limited information initially available. This study explored relevant Canadian pharmacy organizations’ communications of pharmacists’ roles and services during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic for Alberta pharmacists. We observed how these organizations shifted to providing crisis communications to effectively respond and provide guidance to frontline pharmacists, amid the sparse and rapidly changing information. Most of the communication provided by these 5 organizations was direct in the messaging and conveyed a positive, neutral or factual communication style and in some situations used a cautionary communication tone. However, more than one-third of the documents included in this study required knowledge of the specific context and inference for the messaging to be interpreted. While pharmacists’ roles were not new, without clear communication, given the new context of the disaster and policy changes, miscommunication and misinformation can occur. In addition, there was a noticeable increase in pharmacists’ public health and patient care roles mentioned as the pandemic surpassed the first 6 months.

Crisis or risk communication is defined as “the real-time exchange of information, advice and opinions between experts, community leaders or officials and the people who are at risk, which is an integral part of any emergency response.” 40 In addition, the World Health Organization states that effective risk communication is integral to save lives and should include “well-targeted information, with clear messages.” 41 Thus, to navigate the rapidly changing information landscape of this unprecedented pandemic, Alberta pharmacists looked to 5 professional organizations for guidance and direction to what their roles and services should be in a crisis and society’s expectations of the profession. While pharmacists’ roles and services remained unchanged, the context in which they were performed was altered with the pandemic. The pharmacy organizations included in this study provided crisis and risk communications to inform pharmacists’ actions and conversations.

Of the 92 publicly accessible documents, the majority were published by the advocacy bodies—CPhA, CSHP and RxA—followed by the Alberta regulatory body, ACP. There were no documents publicly available by the federal NAPRA regulatory body. However, this was not surprising, given that health care policy is provincial and NAPRA represents provincial regulatory organizations. The pharmacy organizations’ websites were a key communication source to provide rapidly changing and timely information for pharmacists’ conversations with their patients and community members. Notably, CPhA used a specific landing page on its website and provided documents appropriately named “The Daily/The Weekly” to communicate rapidly changing and timely COVID-19 related news and updates to pharmacists and the public.

When it comes to health and drug knowledge, pharmacists have achieved expertise proficiency as information professionals. 42 They are capable of distilling the vast information related to drugs and tailoring their communication to the situation in front of them. When faced with a situation, individuals at an expert level do not rely on rules alone but intuitively default to what they normally do. 43 However, it is postulated that pharmacists, when responding to disasters and emergencies, typically revert to novice proficiency level requiring instruction and guidance to help navigate their actions. 43 They are unfamiliar with the context to make sense of the information and to act accordingly. A study by Johnston et al. 44 reported pharmacists’ challenges with receiving clear communications specific to changing policies and legislation amidst the increased responsibility to provide public health information. The conceptual framework model in this study suggests the same, as pharmacists’ roles were not new, but the context was new and needed to be effectively communicated. Thus, the communication approach should match the changing context and amid a pandemic should be in the form of crisis and risk communications. Our study identified a positive shift in communication by pharmacy organizations as the pandemic progressed past the first 6 months, becoming more direct and clearer in its messaging and context. This is promising, as pharmacists continued to lean into their public health informational role throughout the ongoing pandemic and continued to be a reliable source for COVID conversations.2,3

Limitations

This study focused specifically on Alberta-relevant pharmacy organizations and publicly accessible communications that did not require membership from the organization to view. While communication can take many forms (e.g., webinars) and additional communication channels specific to their members may have been used, we included online communication of pharmacy organizations to the entire pharmacy profession, public and governments. Thus, this study cannot make any generalizations on other communication channels that were used by these organizations. Although the pandemic is ongoing, this study was limited to examining the communication during the first year of the pandemic. In addition, we did not explore pharmacists’ understanding of the communication received from their representative organizations during the study period, which warrants further investigation.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic presented a unique challenge for pharmacy organizations and pharmacists as they navigated rapidly changing policy and information scarcity on the frontlines. While pharmacists’ roles were not new, the context rapidly evolved throughout the first year of the pandemic. In this study, regulatory and advocacy pharmacy organizations provided crisis communication and direction to navigate the changing context of the COVID-19 pandemic, as pharmacists leaned into their public health informational role and being a reliable source for COVID conversations. While COVID conversations were mostly positive and empowering, it is important that crisis communications be clear and direct in its messaging to avoid miscommunication. ■

Footnotes

Author Contributions: K. Watson, M. Ackman and T. Schindel designed the study and provided supervision. C. Safnuk performed the data collection. C. Safnuk, K. Watson and M. Ackman performed data analysis. C. Safnuk wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the manuscript and approved the final version.

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Margaret L. Ackman  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6591-495X

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6591-495X

Theresa J. Schindel  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3221-4444

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3221-4444

Kaitlyn E. Watson  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6617-9398

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6617-9398

Contributor Information

Calli Safnuk, Alberta Health Services, Calgary.

Margaret L. Ackman, Alberta Health Services, Calgary and Edmonton.

Theresa J. Schindel, College of Health Sciences.

Kaitlyn E. Watson, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences and EPICORE Centre, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

References

- 1. Bragazzi NL, Mansour M, Bonsignore A, Ciliberti R. The role of hospital and community pharmacists in the management of COVID-19: towards an expanded definition of the roles, responsibilities and duties of the pharmacist. Pharmacy (Basel) 2020;8(3):140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Watson KE, Schindel TJ, Barsoum ME, Kung JY. COVID the catalyst for evolving professional role identity? A scoping review of global pharmacists’ roles and services as a response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Pharmacy 2021;9(2):99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paudyal V, Cadogan C, Fialova D, et al. Provision of clinical pharmacy services during the COVID-19 pandemic: experiences of pharmacists from 16 European countries. Res Soc Adm Pharm 2021;17(8):1507-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Lee DH, Watson KE, Al Hamarneh YN. Impact of COVID-19 on frontline pharmacists’ roles and services in Canada: the INSPIRE Survey. Can Pharm J 2021;154(6):368-73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Government of Canada. Subsection 56(1) class exemption for patients, practitioners and pharmacists prescribing and providing controlled substances in Canada. 2020. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/controlled-substances-precursor-chemicals/policy-regulations/policy-documents/section-56-1-class-exemption-patients-pharmacists-practitioners-controlled-substances-covid-19-pandemic.html (accessed Fe. 5, 2021).

- 6. Canadian Pharmacists Association. What can pharmacists do under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) during the COVID-19 pandemic? 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/function/utilities/pdf-server.cfm?thefile=/cpha-on-the-issues/CDSA-Adapting_EN.pdf (accessed Feb. 5, 2021).

- 7. Bourne K. All Loblaw pharmacies, shoppers locations in Alberta to offer asymptomatic COVID-19 testing. Global News. 2020. Available: https://globalnews.ca/news/7284041/health-officials-to-update-alberta-covid-19-situation-tuesday-afternoon/ (accessed Sep. 30, 2020).

- 8. Erku DA, Belachew SA, Abrha S, et al. When fear and misinformation go viral: pharmacists’ role in deterring medication misinformation during the ‘infodemic’ surrounding COVID-19. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021;17(1):1954-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hayden JC, Parkin R. The challenges of COVID-19 for community pharmacists and opportunities for the future. Ir J Psychol Med 2020;37(3):198-203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Pharmaceutical Federation. FIP health advisory COVID-19: guidelines for pharmacists and the pharmacy workforce. 2020. Available: https://www.fip.org/file/4729 (accessed Aug. 18, 2020).

- 11. Johnston K, O’Reilly CL, Cooper G, Mitchell I. The burden of COVID-19 on pharmacists. J Am Pharm Assoc 2020;S1544-3191(20):30528-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jordan D, Guiu-Segura JM, Sousa-Pinto G, Wang LN. How COVID-19 has impacted the role of pharmacists around the world. Farm Hosp 2021;45(2):89-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Kristina SA, Herliana N, Hanifah S. The perception of role and responsibilities during COVID-19 pandemic: a survey from Indonesian pharmacists. Int J Pharm Res 2020;12(suppl 2):3034-9. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li H, Zheng S, Liu F, Liu W, Zhao R. Fighting against COVID-19: innovative strategies for clinical pharmacists. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021;17(1):1813-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Li M, Razaki H, Mui V, Rao P, Brocavich S. The pivotal role of pharmacists during the 2019 coronavirus pandemic. J Am Pharm Assoc 2020;60(6):e73-e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sousa Pinto G, Hung M, Okoya F, Uzman N. FIP’s response to the COVID-19 pandemic: global pharmacy rises to the challenge. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021;17(1):1929-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Visacri MB, Figueiredo IV, Lima TdM. Role of pharmacist during the COVID-19 pandemic: a scoping review. Res Social Adm Pharm 2021;17(1):1799-806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yi ZM, Hu Y, Wang GR, Zhao RS. Mapping evidence of pharmacy services for COVID-19 in China. Front Pharmacol 2020;11:555753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bowen GA. Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qual Res J 2009;9(2):27-40. [Google Scholar]

- 20. National Association of Pharmacy Regulatory Authorities (NAPRA). NAPRA—about. Available: https://www.napra.ca/ (accessed Jun. 14, 2021).

- 21. Alberta College of Pharmacy (ACP). Who we are. 2020. Available: https://abpharmacy.ca/ (accessed Jun. 14, 2021).

- 22. Alberta Pharmacists Association (RxA). About advocacy. Available: https://rxa.ca/ (accessed Jun. 14, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 23. Canadian Pharmacists Association (CPhA). About CPhA. 2021. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/ (accessed Jun. 14, 2021).

- 24. Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists (CSHP). Who we are. 2020. Available: https://cshp.ca/ (accessed Jun. 14, 2021).

- 25. Public & Professional Affairs Department. The daily: CPhA’s COVID-19 update for April 16. Ottawa (Ontario): Canadian Pharmacists Association; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/COVIDDaily-April16.pdf (accessed Feb. 3, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alberta College of Pharmacy. COVID-19 guidance—delivery of drugs to assisted living facilities. Edmonton (Alberta): ACP; 2020. Available: https://abpharmacy.ca/covid-19-guidance-delivery-drugs-assisted-living-facilities (accessed Feb. 1, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 27. Canadian Pharmacists Association. National survey of community pharmacists and practice challenges during COVID-19. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/Infographic_drug-shortages-COVID_EN.pdf (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28. Canadian Pharmacists Association. National survey of community pharmacists on drug supply issues during COVID-19. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/Infographic_drug-shortages-COVID_EN.pdf (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 29. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Open letter to the government of Canada—Re: access to personal protective equipment (PPE) for pharmacy professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/assets/File/cpha-on-the-issues/CPhA-Open-Letter-to-Government-re-PPE.pdf (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 30. Alberta College of Pharmacy. Pharmacists needed to administer COVID-19 vaccine. Edmonton (Alberta): ACP; 2020. Available: https://abpharmacy.ca/articles/pharmacists-needed-administer-covid-19-vaccine (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 31. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Stepping up: the 30-day limit, drug shortages and doing what it takes to protect the drug supply. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/stepping-up-the-30-day-limit-drug-shortages-and-doing-what-it-takes-to-protect-the-drug-supply/ (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 32. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Statement on 30-day supply of prescription medications. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/statement-on-30-day-supply-of-prescription-medications/ (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Canadians urge expanding COVID-19 asymptomatic testing across Canada—English. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/canadians-urge-expanding-covid-19-asymptomatic-testing-across-canada/ (accessed Feb. 3, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 34. Government of Canada. Frequently asked questions: subsection 56(1) class exemption for patients, practitioners and pharmacists prescribing and providing controlled substances in Canada. Ottawa (Ontario): Health Canada; 2021. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/health-concerns/controlled-substances-precursor-chemicals/policy-regulations/policy-documents/section-56-1-class-exemption-patients-pharmacists-practitioners-controlled-substances-covid-19-pandemic/frequently-asked-questions.html (accessed Apr. 27, 2022). [Google Scholar]

- 35. Alberta College of Pharmacy. Controlled drugs and substances exemption guidelines. 2021. Available: https://abpharmacy.ca/sites/default/files/Guidelines_Controlled.pdf (accessed Apr. 27, 2022).

- 36. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Canadian pharmacists’ harmonized scope 2020 to focus efforts on pharmacist opioid stewardship. Ottawa (Ontario): CPhA; 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/news-events/news/canadian-pharmacists-harmonization-scope-2020-to-focus-efforts-on-pharmacist-opioid-stewardship/ (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 37. Canadian Pharmacists Association. Suggested best practices for community pharmacy: providing influenza immunizations during the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/education-practice-resources/patient-care/influenza/influenza-2020-2021-suggested-best-practices-for-pharmacies/ (accessed Feb. 5, 2021).

- 38. Public & Professional Affairs Department. The weekly: CPhA’s COVID-19 update for September 9. CPhA. 2020. Available: https://www.pharmacists.ca/cpha-ca/function/utilities/pdf-server.cfm?thefile=/cpha-on-the-issues/COVIDWeekly-Sep9.pdf (accessed Feb. 5, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 39. Alberta College of Pharmacy. Can pharmacists write referrals for massage therapy? Edmonton (Alberta): ACP; 2021. Available: https://abpharmacy.ca/articles/can-pharmacists-write-referrals-massage-therapy (accessed Feb. 1, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 40. World Health Organization. Communicating risk in public health emergencies: A WHO guideline for emergency risk communication (ERC) policy and practice. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction (UNDRR) Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, World Health Organization. UNDRR Asia Pacific COVID-19 brief: risk communication and countering the ‘infodemic.’ New York: United Nations; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Byrd GD. Can the profession of pharmacy serve as a model for health informationist professionals? J Med Library Assoc 2002;90(1):68-75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Dreyfus SE, Dreyfus HL. A five-stage model of the mental activities involved in directed skill acquisition. Berkeley: University of California Berkeley Operations Research Center; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Johnston K, O’Reilly CL, Scholz B, Mitchell I. The experiences of pharmacists during the global COVID-19 pandemic: a thematic analysis using the jobs demands-resources framework. Res Social Adm Pharm 2022;18(9):3649-55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]