Abstract

Context.

Children with life-shortening serious illnesses and medically-complex care needs are often cared for by their families at home. Little, however, is known about what aspects of pediatric palliative and hospice care in the home setting (PPHC@Home) families value the most.

Objectives.

To explore how parents rate and prioritize domains of PPHC@Home as the first phase of a larger study that developed a parent-reported measure of experiences with PPHC@Home.

Methods.

Twenty domains of high-value PPHC@Home, derived from the National Consensus Project’s Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care, the literature, and a stakeholder panel, were evaluated. Using a discrete choice experiment, parents provided their ratings of the most and least valued PPHC@Home domains. We also explored potential differences in how subgroups of parents rated the domains.

Results.

Forty-seven parents participated. Overall, highest-rated domains included Physical aspects of care: Symptom management, Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the child, and Care coordination. Lowest-rated domains included Spiritual and religious aspects of care and Cultural aspects of care. In exploratory analyses, parents who had other children rated the Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the sibling(s) domain significantly higher than parents who did not have other children (P = 0.02). Furthermore, bereaved parents rated the Caregiver support at the end of life domain significantly higher than parents who were currently caring for their child (P = 0.04). No other significant differences in domain ratings were observed.

Conclusion.

Knowing what parents value most about PPHC@Home provides the foundation for further exploration and conversation about priority areas for resource allocation and care improvement efforts.

Keywords: Pediatric palliative care, pediatric hospice care, home-based care, discrete choice experiment

Introduction

Children with life-shortening serious illnesses and medically-complex care needs are increasingly cared for by their families at home, particularly toward the end of life.1–4 These children and families are supported in the home setting by palliative and hospice care programs that vary in structure, staffing, funding, and patient census.5–9 As a result, many children and their families in the U.S. have variable and, at times, inadequate access to high-quality pediatric palliative and hospice care in the home setting (PPHC@Home).7,10,11

Previous research with primarily inpatient-based samples of parents and providers has identified several factors that improve parents’ perceptions of the quality of care, including effective pain and symptom management,12–16 child-centered and family-centered care and decision making,12,16 inclusion of siblings in care processes,13,17 consistent and high-quality communication between family and providers,13–17 family education and preparation for the end of life,14 psychosocial and spiritual care,12,15–17 a comfortable death,15,16 care coordination and management,12,16 and bereavement care.13 evidence suggests that these domains of care are as important in the home setting.7,10,13,18–22 Little is known, however, about which of these care domains parents value the most in supporting their child in their home, and how these domains compare in importance to one another. Previous studies prioritized areas for high-quality PPHC@Home clinical care and research using Delphi methods with PPHC@Home stakeholders, including providers and parents.18,20 Among top-rated priorities were services, techniques, and resources for pain and symptom relief and psychological support for children and young adults.18 Given limitations to Delphi-rating methodologies, including the limited ability to differentiate between similar rating scores18 and concerns about stability of rating scores,23 we do not know which of these care domains are most important in supporting children at home. Although high-quality PPHC@Home encompasses the spectrum of care domains,20,22 health care resources, particularly in the home and community setting,7,8 are finite. Knowing, therefore, what parents value most could help guide allocation of these scarce resources, as well as future clinical and research efforts to measure and improve the quality of PPHC@Home.

The goal of this analysis was to measure parents’ priorities for PPHC@Home using a quantitative choice-based approach. This analysis represents the first phase of a larger study to develop a parent-reported measure of experiences with PPHC@Home.24

Methods

Study Design

We conducted a cross-sectional assessment of parents’ priorities regarding the importance of 20 different PPHC@Home domains of care. This assessment represents the first phase of a larger project to develop a parent-reported measure of experiences with PPHC@Home.24 The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s Institutional Review Board approved the conduct of this study.

Conceptual Framework for the Domains

The framework for the domains used in this study came from the National Consensus Project’s (NCP) Clinical Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (fourth edition),22 which were further adapted using pediatric palliative care (PPC)-specific guidelines and the literature20,25–28 and informed by a panel of stakeholders (PPC providers and parent advocates). The adapted framework includes 20 PPHC@Home-specific domains and subdomains (Table 1).

Table 1.

Domains of High-Quality PPHC in the Home

| Domains | Description |

|---|---|

| Communication between family and care team | Care team communicates with the child and family to make sure that the care provided meets the child’s and family’s values, preferences, goals, and needs |

| Relationship between family and care team | Relationship between care team and family is built on trust, respect, and advocacy for the child’s and family’s needs |

| Knowledge and skills of care team providers | Care team members have the necessary education and training to provide high-quality palliative care for children and families |

| Access to care | Care team provides access to palliative and hospice care to the child and family 24 hours a day, seven days a week |

| Physical care: Communication | Care team provides information about treatments for child’s pain and other physical symptoms (e.g., nausea, fatigue, constipation) |

| Physical care: Symptom management | Care team assesses and manages pain and other physical symptoms and side effects based on the best available medical evidence |

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care (child, parents, siblings, and extended social network)a | Care team assesses and manages psychological and emotional issues (such as anxiety, distress, coping, grief) of the child, family, and family’s community based on the best available medical evidence |

| Practical aspects of care | Care team provides the family with assistance and resources for dealing with financial and insurance-related issues |

| Social aspects of care (child, parents)a | Care team helps with social issues to meet child-family needs, promote child-family goals, and maximize child-family strengths and well-being (examples include helping family maintain and strengthen their support network; help family develop strategies to balance caregiving, work, and family needs) |

| Spiritual and religious aspects of care | Care team assists with religious and spiritual rituals or practices as desired by the child and family |

| Cultural aspects of care | Care team respects the child’s and family’s cultural beliefs and language preferences |

| Communication at the end of life | Care team works with the child and family to develop and implement a care plan to address actual or potential symptoms at the end of life |

| Caregiver support at the end of life | Care team meets the emotional, spiritual, social, and cultural needs of families at the end of life (e.g., preparing parents for the end of life) |

| Ethical and legal aspects of care | Child’s and family’s goals, preferences, and choices are respected within the limits of state and federal law, current standards of medical care, and professional standards of practice These goals/preferences/choices are documented and shared with all professionals involved in the child’s care |

| Coordination of care | Care team works to make sure that when there are transfers between health care settings and providers, that there is timely and thorough communication of the child’s/family’s goals, preferences, values, and clinical information to ensure continuity of care and seamless follow-up (e.g., getting needed services, arranging for medical equipment) |

| Continuity of care | Care team works to make sure that the delivery of palliative and hospice care is seamless across care settings and providers (e.g., the same providers work with family) |

PPHC = pediatric palliative and hospice care.

Note: These domains are based on the National Consensus Project’s Clinical Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care (fourth edition),22 which were further adapted using pediatric palliative care-specific guidelines and the literature20,25–28 and informed by a panel of pediatric palliative care stakeholders (providers and parent advocates).

Separate subdomain for each group.

Sample

Parents were eligible if they were english speaking, older than 18 years, and had a child with a serious illness who was younger than 25 years at the time care was received. We included parents whose children were currently receiving PPHC@Home, as well as bereaved parents whose children had previously received PPHC@Home. Parents were recruited from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia’s (CHOP) Pediatric Advanced Care Team and from the Courageous Parents Network (CPN), which is a virtual community of parents, families, and providers that supports parents with information, skills, tools, and other resources during their child’s illness journey.29

For participants recruited from CHOP, the principal investigator (PI; first author [J. Y. B.]) worked closely with Pediatric Advanced Care Team’s nurse coordinator and social worker to screen for eligible participants. The PI then contacted participants by phone. Interested parents provided their electronic informed consent and completed the Web-based survey concurrently (in person or by phone) with the PI or independently via a Web link. For participants recruited from CPN, the PI worked closely with staff of CPNs to post recruitment materials to the CPN listserv and social media page. Interested participants contacted the PI via phone or electronic mail and were screened for eligibility. eligible participants provided their electronic informed consent and completed the survey via a Web link either concurrently with the PI or independently. Participants were compensated with a $30 gift card for their time and effort.

Discrete Choice experiment

Participants engaged in a discrete choice experiment (DCE), which is a quantitative choice-based approach to evaluating individuals’ stated preferences regarding choices in health care30–34 and other settings.35,36 We used a DCE with maximum difference (MaxDiff) scaling to obtain a quantitative estimate of the relative importance of each domain (i.e., domain importance scores), as rated by parents, and to rank the PPHC@Home domains by order of the parent-rated importance scores.

Participants first reviewed a list of all 20 PPHC@Home domains and associated definitions (as displayed in Table 1); these definitions were available to participants throughout the DCE. Participants were then presented with sets displaying four of the 20 domains. Within each set, participants were instructed to choose, from the four listed domains, the one that they felt was the most important in supporting their child in the home and the domain they felt was least important. This process was repeated for a total of 15 sets, each set being a different combination of the 20 domains, with the same instructions to choose the most and least important among the four domains listed in that set. Across all the sets for each respondent, the design of the DCEs ensured that each domain was shown exactly three times and in a balanced set of combinations and permutations with the other domains. Completing all 15 sets took participants approximately 8–10 minutes.

Data Analysis

Based on the choices that participants made across the 15 DCE sets, domain importance scores were calculated using a hierarchical Bayesian application of multinomial logistic regression, which estimated the average (mean) probability, with 95% CIs, of each domain being chosen as the most or least important for individual participants and across the entire sample. The raw logit scores were then transformed to a relative importance score on a 0–100 probability scale, where scores sum to 100 across domains.37,38 This transformation facilitates a readily interpretable comparison of domains.39 More specifically, this transformed score indicates the relative importance of domains on a common scale; for example, a domain that is given a score of 10 is perceived by respondents (as revealed via their choices) as being twice as important as a domain with a score of 5. Domains were rank ordered according to their importance score, where higher scores indicated higher perceived importance. To describe the variation in how respondents rated each domain, we also calculated the interquartile range (IQR) in each domain and reported the median, 25th and 75th percentiles, and any outliers.40

In additional analyses, we explored how domain ratings differed depending on whether there were siblings in the household, whether the parent was bereaved, and whether the parent was a mother or a father. All comparisons were conducted using two-sample independent t-tests. Given the exploratory nature of these subgroup analyses, P-values < 0.1 were considered statistically significant.

Sample Size Considerations

DCEs of the design we used converge on stable estimates of the relative scores for items with as few as 20 participants in subgroups.41,42 There are currently no standard guidelines for defining sample sizes for these DCE studies; therefore, simulation studies, where the effect of different sample sizes are simulated to test the effect on the reliability of estimates, are recommended.43 Using data from a previous DCE with a sample of 200 parents of children with serious illnesses,34 we used a bootstrap approach to draw overall data set samples of 20, 30, or 50 individual responses to the DCE at a time, doing so with replacement and iterating this process 100 times for each sample size. Across all three sample sizes, all items were consistently ordered from top to bottom. Although the CIs indicated that similarly-rated items may, for some samples, switch ranking, they demonstrated that with a sample size of 30, high-rated items can be clearly differentiated from low-rated items. Thus, we aimed to recruit a minimum of 30 parent participants from 30 unique families.

Survey and Analytic Software

We designed the DCE and deployed the survey instruments using Lighthouse Studio (Version 9.6.1; Sawtooth Software, Provo, UT), which includes a cloud-based survey platform. We calculated the domain importance scores based on participants’ choices across the DCE sets using Lighthouse Studio and conducted statistical analysis of the importance scores using Stata, version 15.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

Forty-seven parents from 45 families participated (Table 2). Most participants were white (89.4%), non-Hispanic (91.5%), and mothers (93.6%) who were married or partnered (87.2%) and had completed college or graduate school (68.1%). Parents’ mean age was 42.6 years (SD 8.5). Fourteen parents (29.8%) were bereaved, and 33 (70.2%) parents were currently caring for their child at home. Sixteen of the 47 parents (34%) received care for their child primarily from CHOP’s interprofessional palliative care service.

Table 2.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Parents and Children

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Parents’ Characteristics (n = 47) | |

| Parent type | |

| Mother | 44 (93.6) |

| Father | 3 (6.4) |

| Age | |

| Mean/SD | 42.6 (8.5) |

| Race | |

| White | 42 (89.4) |

| Black or African American | 1 (2.1) |

| More than one race/other | 3 (6.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.1) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 43 (91.5) |

| Hispanic | 3 (6.4) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.1) |

| Religious preference | |

| Christian (Protestant, Catholic, Mormon, etc.) | 31 (66.0) |

| Jewish | 6 (12.8) |

| Muslim | 0 |

| Buddhist | 1 (2.1) |

| Hindu | 1 (2.1) |

| Atheist | 3 (6.4) |

| Agnostic | 2 (4.3) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (6.4) |

| Highest education level completed | |

| Grade school | 1 (2.1) |

| High school/general educational development | 2 (4.3) |

| Trade/technical/vocational | 4 (8.5) |

| Associates/professional | 8 (17.0) |

| College | 19 (40.4) |

| Graduate school | 13 (27.7) |

| Relationship status | |

| Married/partnered | 41 (87.2) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 6 (12.8) |

| Number of other children | |

| 0 | 11 (23.4) |

| 1–3 | 35 (74.5) |

| 4 or more | 1 (2.1) |

| Employment status | |

| Full time | 23 (48.9) |

| Part time | 5 (10.6) |

| Not employed outside the home | 17 (36.2) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4.3) |

| Bereavement status | |

| Bereaved | 14 (29.8) |

| Currently caring for child at home | 33 (70.2) |

| Affiliation | |

| CHOP | 16 (34.0) |

| CPN | 31 (66.0) |

| Children’s Characteristics (n = 45) | |

| Age (yrs) | |

| One or less | 8 (17.8) |

| 2–4 | 9 (20.0) |

| 5–9 | 5 (11.1) |

| 10–18 | 17 (37.8) |

| 19–25 | 6 (13.3) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 21 (46.7) |

| Male | 24 (53.3) |

| Race | |

| White | 37 (82.2) |

| Black or African American | 2 (4.4) |

| More than one race/other | 5 (11.1) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic | 39 (86.7) |

| Hispanic | 4 (8.9) |

| Prefer not to answer | 2 (4.4) |

| Primary complex chronic condition (Note: not mutually exclusive; thus, the percent does not sum to 100%) | |

| Cardiovascular | 10 (22.2) |

| Gastrointestinal | 4 (8.9) |

| Genetic or congenital | 22 (48.9) |

| Hematologic or immunologic | 4 (8.9) |

| Malignancy | 5 (11.1) |

| Metabolic | 10 (22.2) |

| Neuromuscular, neurologic, or mitochondrial | 23 (51.1) |

| Respiratory | 6 (13.3) |

| Other/unknown | 1 (2.2) |

| Primary care team (hospice v. palliative care) | |

| Hospice | 19 (42.2) |

| Palliative care | 24 (53.3) |

| Unknown/not sure | 2 (4.4) |

| Length of time receiving home-based palliative or hospice care | |

| Less than one month | 5 (11.1) |

| One to three months | 5 (11.1) |

| Four to six months | 7 (15.6) |

| Seven to 12 months | 5 (11.1) |

| One to two years | 8 (17.8) |

| More than two years | 15 (33.3) |

CHOP = Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; CPN = Courageous Parents Network.

Note: Unless otherwise noted, cell entries are percentages. Percentages are within each demographic or clinical characteristic variable.

Participants were parents to 45 children who have received PPHC@Home. Approximately half of these children were between birth and nine years, and half were between 10 and 25 years. Most prevalent primary diagnoses included neuromuscular, neurologic, or mitochondrial (51.1%), genetic or congenital(48.9%), cardiovascular (22.2%), and metabolic(22.2%) diseases. More than half of these children received home-based support primarily from a palliative care team (53.3%), and a third of these children received PPHC@Home for more than two years(33.3%).

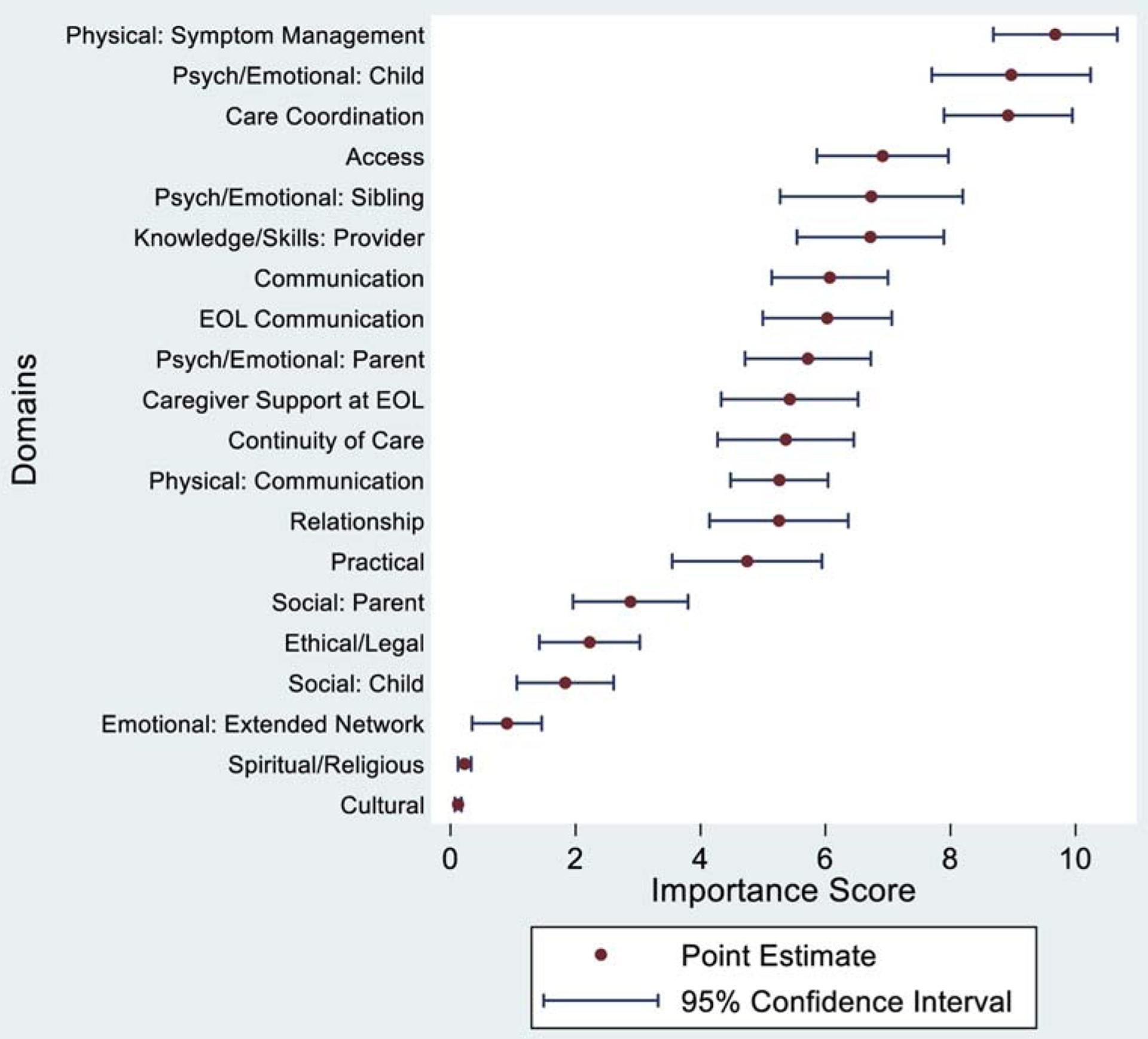

Average Domain Importance Scores and Ranking

Among the 20 domains of PPHC@Home (Fig. 1), parents ranked the Physical aspects of care: Symptom management domain the highest (mean score = 9.68; 95% CI = 8.71, 10.64), followed by Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the child (mean score = 8.97; 95% CI = 7.74, 10.21) and Care coordination (mean score = 8.92; 95% CI = 7.92, 9.92). Among the lowest-ranked domains were emotional aspect of care for the extended social network (0.90; 95% CI = 0.36, 1.45), Spiritual and religious aspects of care (mean score = 0.22; 95% CI = 0.12, 0.32), and Cultural aspects of care (mean score = 0.12; 95% CI = 0.07, 0.17).

Fig. 1.

Average importance scores across domains. Note: This figure contains the point estimates of the mean importance score for each domain. The 95% CI around each point estimate represents our level of confidence that the interval captures the true point estimate. EOL = end of life.

In terms of relative importance, parents rated the Physical aspects of care: Symptom management domain as being twice as important as the Practical aspects of care domain (mean score = 9.68 vs. 4.75) and nearly 10 times as important as the emotional aspects of care for the family’s extended social network domain (mean score = 9.68 vs. 0.90).

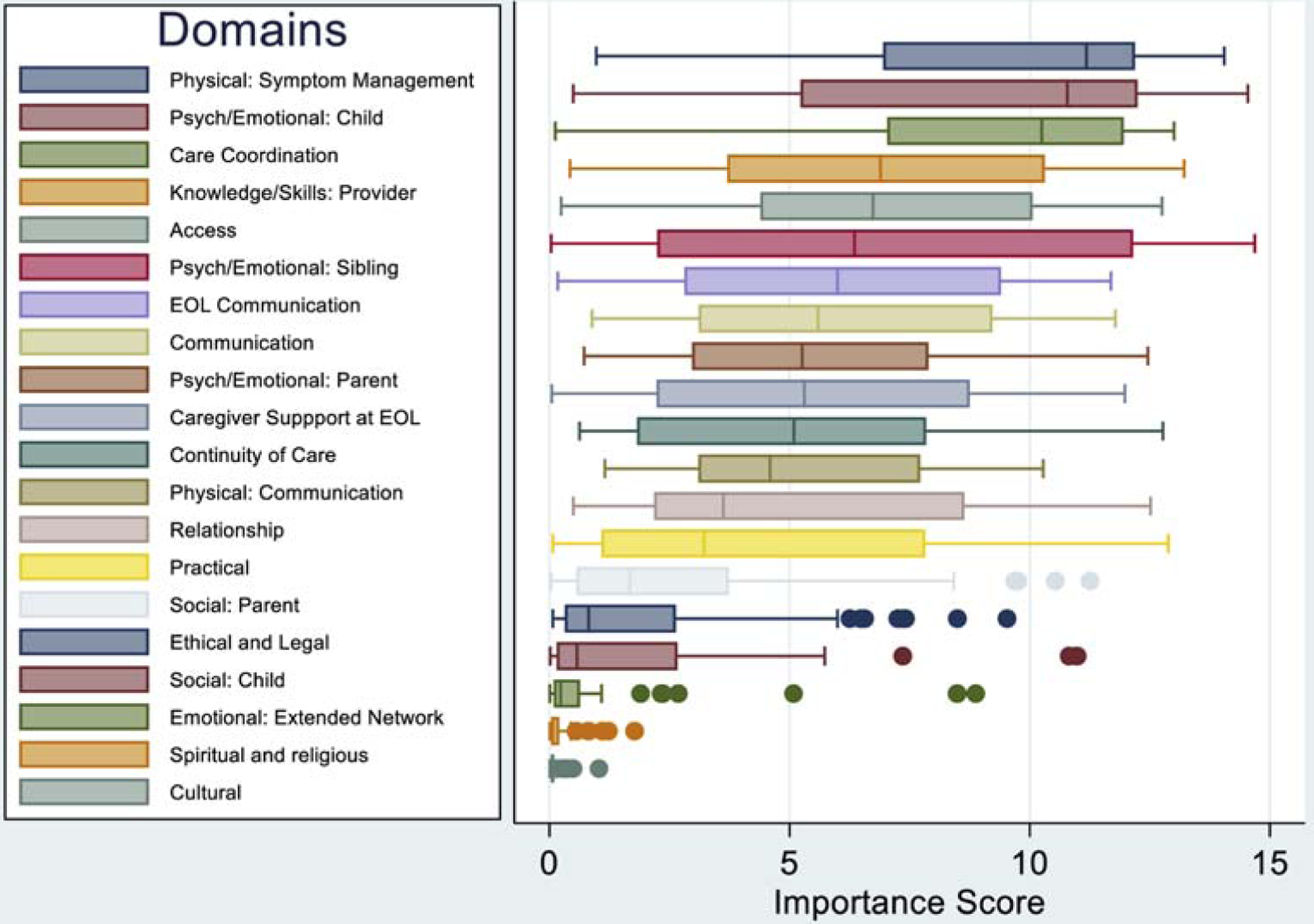

Individual-Level Variation in Domain Importance Scores and Ranking

Domains differed not only regarding their mean importance score, but also in the degree to which the participants, as a group, varied in their scores for given domains. For example, the Physical aspects of care: Symptom management domain had a median score of 11.18 and an IQR range of 5.25, whereas the Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the sibling(s) domain had a median score of 6.35, yet a much larger IQR of 9.91, representing greater variation in how respondents rated this domain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Individual-level variation across domain importance scores. Note: This graph presents the interquartile range of domains, which represents the spread of the middle half of the scores in each domain. The line within each box represents the median, the left edge of the box represents the 25th percentile, and the right edge represents the 75th percentile of scores. The whiskers extending out of the box represents minimum and maximum scores, except for outliers (defined as more than 1.5 interquartile range beyond the 25th and 75th quartiles), which are represented by the dots.40 EOL = end of life.

Additional Analysis: Subgroup Comparisons in Domain Importance Scores

We examined three potential notions of how parents might differ in their importance ratings of domains. First, we assessed how parents with other children rated the sibling-specific domain (Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the sibling) compared with parents who did not have other children. The mean score for parents with at least one other child (n = 38) was 7.55 (95% CI 6.01, = 9.10), whereas for parents without other children (n = 9), the mean score was 3.27 (95% CI = −0.48, 7.02) (t = −2.44; P 0.02). Second, we compared parents currently caring for their child (n = 33) and bereaved parents (n = 14) across all 20 domains; only the Caregiver support at the end of life domain had significantly different scores at the P < 0.1 level (t = −2.07; P = 0.04), where bereaved parents rated this domain 1.5 times as important as parents currently caring for their child. Third, mothers’ (n = 44) and fathers’ (n = 3) domain importance scores did not display any statistically significant differences (Table 3).

Table 3.

Subgroup Domain Score Comparisons: Two-Sample Independent t-Tests

| Domain | Subgroup | Mean | 95% CI | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single domain: Parents without other children (n = 9) vs. parents with other children (n = 38) | ||||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care for the sibling(s) | ||||

| No siblings | 3.27 | −0.48, 7.02 | 0.02a | |

| One or more siblings | 7.55 | 6.01, 9.10 | ||

| Across all domains: parents currently caring for child (n = 33) vs. bereaved parents (n = 14) | ||||

| Communication between family and care team | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 6.08 | 4.99, 7.16 | 0.98 | |

| Bereaved | 6.05 | 4.00, 8.10 | ||

| Relationship between family and care team | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.53 | 4.24, 6.82 | 0.45 | |

| Bereaved | 4.61 | 2.21, 7.00 | ||

| Knowledge and skills of care team providers | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 6.63 | 5.12, 8.13 | 0.81 | |

| Bereaved | 6.94 | 4.93, 8.96 | ||

| Access to care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 6.55 | 5.32, 7.79 | 0.29 | |

| Bereaved | 7.77 | 5.56, 9.97 | ||

| Physical care: Communication | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.39 | 4.46, 6.31 | 0.62 | |

| Bereaved | 4.96 | 3.31, 6.62 | ||

| Physical care: Symptom management | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 9.33 | 8.05, 10.60 | 0.28 | |

| Bereaved | 10.50 | 8.92, 12.07 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Parent | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.70 | 4.42, 6.99 | 0.97 | |

| Bereaved | 5.75 | 3.98, 7.53 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Child | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 8.78 | 7.23, 10.32 | 0.64 | |

| Bereaved | 9.43 | 6.92, 11.95 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Sibling(s) | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 6.84 | 4.99, 8.69 | 0.83 | |

| Bereaved | 6.49 | 3.86, 9.13 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Extended social network | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 1.04 | 0.30, 1.79 | 0.45 | |

| Bereaved | 0.57 | −0.18, 1.33 | ||

| Practical aspects of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.21 | 3.76, 6.66 | 0.24 | |

| Bereaved | 3.65 | 1.36, 5.95 | ||

| Social aspects of care: Parents | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 3.18 | 2.02, 4.35 | 0.31 | |

| Bereaved | 2.16 | 0.60, 3.73 | ||

| Social aspects of care: Child | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 2.02 | 0.96, 3.08 | 0.47 | |

| Bereaved | 1.40 | 0.56, 2.24 | ||

| Spiritual and religious aspects of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 0.20 | 0.09, 0.31 | 0.48 | |

| Bereaved | 0.28 | 0.01, 0.56 | ||

| Cultural aspects of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 0.14 | 0.07, 0.22 | 0.19 | |

| Bereaved | 0.07 | 0.03, 0.11 | ||

| Communication at the end of life | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.80 | 4.43, 7.17 | 0.51 | |

| Bereaved | 6.56 | 5.08, 8.04 | ||

| Caregiver support at the end of life | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 4.72 | 3.34, 6.10 | 0.04a | |

| Bereaved | 7.10 | 5.47, 8.72 | ||

| Ethical and legal aspects of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 2.04 | 1.09, 3.00 | 0.49 | |

| Bereaved | 2.65 | 0.99, 4.31 | ||

| Coordination of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 8.99 | 7.75, 10.23 | 0.84 | |

| Bereaved | 8.76 | 6.67, 10.85 | ||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Currently caring for child | 5.82 | 4.43, 7.22 | 0.20 | |

| Bereaved | 4.28 | 2.56, 5.99 | ||

| Across all domains: Mothers (n = 44) vs. fathers (n = 3) | ||||

| Communication between family and care team | ||||

| Mothers | 6.10 | 5.13, 7.07 | 0.77 | |

| Fathers | 5.55 | −3.12, 14.21 | ||

| Relationship between family and care team | ||||

| Mothers | 5.13 | 3.97, 6.29 | 0.40 | |

| Fathers | 7.07 | −1.87, 16.02 | ||

| Knowledge and skills of care team providers | ||||

| Mothers | 6.72 | 5.51, 7.93 | 0.99 | |

| Fathers | 6.73 | −6.81, 20.28 | ||

| Access to care | ||||

| Mothers | 6.99 | 5.90, 8.08 | 0.60 | |

| Fathers | 5.84 | −3.88, 15.56 | ||

| Physical care: Communication | ||||

| Mothers | 5.10 | 4.30, 5.91 | 0.12 | |

| Fathers | 7.57 | 1.95, 13.19 | ||

| Physical care: Symptom management | ||||

| Mothers | 9.65 | 8.62, 10.68 | 0.28 | |

| Fathers | 10.08 | −0.11, 20.26 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Parent | ||||

| Mothers | 5.74 | 4.67, 6.80 | 0.89 | |

| Fathers | 5.44 | −1.23, 12.11 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Child | ||||

| Mothers | 8.75 | 7.42, 10.08 | 0.17 | |

| Fathers | 12.29 | 10.14, 14.44 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Sibling(s) | ||||

| Mothers | 6.80 | 5.29, 8.31 | 0.72 | |

| Fathers | 5.73 | −9.79, 21.25 | ||

| Psychological and emotional aspects of care: Extended social network | ||||

| Mothers | 0.91 | 0.32, 1.50 | 0.97 | |

| Fathers | 0.86 | −2.29, 4.01 | ||

| Practical aspects of care | ||||

| Mothers | 4.82 | 3.57, 6.06 | 0.64 | |

| Fathers | 3.67 | −7.66, 15.01 | ||

| Social aspects of care: Parents | ||||

| Mothers | 3.01 | 2.04, 3.99 | 0.27 | |

| Fathers | 0.92 | −0.11, 1.94 | ||

| Social aspects of care: Child | ||||

| Mothers | 1.79 | 0.98, 2.59 | 0.65 | |

| Fathers | 2.52 | −4.44, 9.48 | ||

| Spiritual and religious aspects of care | ||||

| Mothers | 0.24 | 0.12, 0.35 | 0.43 | |

| Fathers | 0.06 | −0.01, 0.14 | ||

| Cultural aspects of care | ||||

| Mothers | 0.13 | 0.07, 0.18 | 0.40 | |

| Fathers | 0.04 | −0.01, 0.08 | ||

| Communication at the end of life | ||||

| Mothers | 6.09 | 5.01, 7.18 | 0.63 | |

| Fathers | 5.06 | −2.87, 13.00 | ||

| Caregiver support at the end of life | ||||

| Mothers | 5.50 | 4.36, 6.64 | 0.60 | |

| Fathers | 4.33 | −5.20, 13.87 | ||

| Ethical and legal aspects of care | ||||

| Mothers | 2.34 | 1.50, 3.19 | 0.26 | |

| Fathers | 0.49 | −0.88, 1.85 | ||

| Coordination of care | ||||

| Mothers | 8.89 | 7.81, 9.96 | 0.78 | |

| Fathers | 9.48 | 1.41, 17.55 | ||

| Continuity of care | ||||

| Mothers | 5.30 | 4.20, 6.41 | 0.67 | |

| Fathers | 6.27 | −7.75, 20.29 | ||

Significant at P < 0.1 level.

Discussion

We conducted a DCE to prioritize 20 PPHC@Home domains based on quantitative parent-rated domain importance scores and identified, through exploratory analysis, potential differences in how subgroups of parents rated these domains. Several of our findings warrant discussion.

First, parents ranked Physical aspects of care: Symptom management and Psychological/emotional aspects of care for the child as the most important domains. This prioritization is unsurprising, given the proportion of children with serious illness who experience pain and other distressing physical symptoms, such as fatigue, reduced mobility, and constipation,2,44–47 and psychological symptoms, such as sadness, worry, and anxiety.2,45,48,49 The relief of symptoms is often described by pediatric and adult patients and their family caregivers as a top concern and priority for quality palliative and end-of-life care;12,15,50−53 yet, the assessment and management of pain and other symptoms has room for improvement for patients across ages, diagnoses, and settings.13,15,49,53–57 Inadequate pain and symptom management has been associated with child and family outcomes, such as lower child health-related quality of life,45,58 long-term parental grief and distress,59,60 and parents’ more negative perceptions of care quality.12,13,61

Parents also ranked Care coordination among the most important domains. Seriously-ill and medically-complex children often have significant care needs, necessitating care from a complex network of providers across numerous settings and institutions.62 As a result, parents, providers, and health care leaders have identified care coordination as a significant need26,52,63 and a priority for clinical practice, policy, and research.25,26,64,65 Notably, care coordination was added as a key theme in each domain in the most recent edition of the NCP Guidelines,22 and with good reason: care coordination is associated with improved care quality and child and family outcomes (e.g., quality of life, symptom management, death in preferred location) in the home and community settings.8,19,20,62,66–68 However, coordinating care by health care teams, a time-consuming endeavor, is often not reimbursed.69,70 Future research should examine the effectiveness and efficiency of different models of care coordination, followed by advocacy to align reimbursement with high-value service models.

The lowest-ranked domains in this study were Spiritual and religious aspects of care and Cultural aspects of care. Although we know that these care domains are critical components of effective PPHC,71–74 they have been found to be more important for some families than others.54,71 In particular, these two domains may be ranked lower by parents in our sample, who were largely white, non-Hispanic, and Christian; a more diverse sample of parents may have prioritized these domains higher. Another possible explanation is that when parents are forced to choose between domains, as in this discrete choice exercise, parents may prioritize the management of their child’s symptoms and the effective coordination of their child’s care over spiritual or cultural aspects of care. A previous DCE study identified parents’ beliefs about what they need to do to be a good parent to their seriously-ill child. This study, conducted with 200 parents of children with serious illness, similarly found that beliefs such as Making my child feel loved and Focusing on my child’s comfort were ranked higher by parents than the belief Focusing on my child’s spiritual well-being.34 Finally, some children and families may receive support for their spiritual, religious, and cultural needs from community-based organizations or other social support networks and may simply not expect or require this type of support from their PPHC@Home team.

We did observe potential differences in how subgroups of parents ranked the domains. In particular, we found that parents who had other children ranked the Psychological/emotional aspects of care for sibling(s) domain more than twice as important as parents who did not have other children. This finding is unsurprising in light of the documented needs of siblings of seriously-ill children52,56,75,76 and the significant stress parents face when balancing the care of their seriously-ill child with care of the child’s siblings.77,78 Given the proximity of siblings to their ill sibling’s care in the home setting,76 further intervention-based research is needed to understand how this support may best be provided to siblings in the home setting in particular. We also observed differences in how bereaved parents and parents currently caring for their child rated the Caregiver support at the end of life domain. This is likely because parents who are actively caring for their child who is not yet at the end of life may not see bereavement care as important when compared with other domains representing more immediate needs or concerns. Alternatively, parents may be unwilling or unable to consider a time when bereavement care is needed for their family.

Finally, we did not observe significant differences in how mothers and fathers ranked the domains, although these rankings represent the views of only three fathers and, thus, precludes any conclusions to be drawn. Although further exploration with larger samples of fathers is greatly needed in this area, previous research with larger samples of fathers have found that the major areas of problems, hopes, and goals related to a child’s care were not significantly different between mothers and fathers,79 and that the type of support parents need to care for their child with serious illness at home may be the same, regardless of gender.77

This study has four limitations that warrant mention. First, the gender and sociodemographic characteristics of our sample were relatively homogenous. Although this homogeneity is not surprising given issues with gender80,81 and minority82 imbalance in PPC studies, as well as disparities in access to home-based hospice care in general by minority patients,83 additional research with larger and more sociodemographically diverse samples is critically needed to more fully understand parental priorities, particularly among underrepresented groups (e.g., fathers, racial and ethnic minorities, single parents, other cultural and religious groups, families from lower socioeconomic groups).

Second, although families in our study received care from various geographic regions of the U.S. (e.g., east Coast, Mid-Atlantic, Mid-West, South), we did not collect data about the PPHC@Home programs that served the families in our sample. As a result, parents may have evaluated a domain of care as less important if services addressing that domain (e.g., spiritual care, support for the sibling) were ineffective or unavailable or if families chose not to use particular services. These variations in experiences may have influenced parents’ domain ratings. We do note that, anecdotally, as part of this overall larger study, several bereaved parents recounted receiving less-than-effective aspects of their PPHC@Home experiences that they felt were very important to improve on for future children and families. For example, several parents discussed a lack of adequate access to appropriately-trained (e.g., pediatric and palliative/hospice care trained) nursing support in the home; yet, all of these parents acknowledged the critical role nursing care plays in good PPHC@Home. Future research is needed to evaluate differences in care experiences with larger samples of families who receive different models of care (e.g., adult hospice programs that also care for children, pediatric-specific hospice programs, hospital-based PPC programs that also support families at home) from different geographic regions of the U.S.

Third, this study may have omitted important domains of PPHC@Home. We believe, however, that this is unlikely because the domains were based on the NCP Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care22 and informed by PPC-specific guidelines and literature20,25–28 and by a panel of PPHC stakeholders.

Fourth, because of the cross-sectional design of this study, we do not know how much individual parental ratings of importance change over time. Future longitudinal studies will be important to examine trends in parents’ priorities over the course of their child’s illness. Our findings, however, build on and extend beyond findings from previous studies, providing quantitative evidence for the overall importance of excellent pain and symptom management, psychological and emotional support for seriously-ill children, and integrated, coordinated care for children with serious illness and their families in the home setting.19,66–68,75,84,85

Conclusion

The priorities for PPHC@Home among parents in this study represent a foundation for further exploration and conversation about how to prioritize finite health care resources and where to focus care improvement efforts and future research, particularly in the home-based setting, for seriously-ill children and their families.

Key Message.

This article describes parents’ priorities for pediatric palliative and hospice care in the home setting (PPHC@Home). Parents provided their ratings and rankings of PPHC@Home domains in a discrete choice experiment. Understanding parents’ priorities for PPHC@Home facilitates further exploration and conversation about priority areas for resource allocation and care improvement efforts.

Disclosures and Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the Justin Michael Ingerman Center for Palliative Care at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the Courageous Parents Network, who facilitated the design and data collection phases of this study. In particular, they thank Karen Crew and Dana Dombrowski for their guidance and effort on this project, as well as Russell Nye for his review of this manuscript. They also acknowledge all the clinicians, researchers, and parent advocates who shared their time and expertise with them. And finally, they thank the parents who so generously gave their time and energy to participate in this project—they are truly grateful for parents’ willingness to share their perspectives with them.

This work was supported by the National Institute of Nursing Research of the National Institutes of Health under award number F31NR017554. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. This work was additionally supported by the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing Office of Nursing Research’s Student Research grant, the Independence Blue Cross Foundation’s Nurses for Tomorrow Scholars Program, and the Sawtooth Software Academic Grant.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Feudtner C, Feinstein JA, Satchell M, Zhao H, Kang TI. Shifting place of death among children with complex chronic conditions in the United States, 1989–2003. JAMA 2007;297:2725–2732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, et al. Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics 2011;127:1094–1101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feudtner C, Silveira MJ, Christakis DA. Where do children with complex chronic conditions die? Patterns in Washington State, 1980–1998. Pediatrics 2002;109:656–660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nageswaran S, Radulovic A, Anania A. Transitions to and from the acute inpatient care setting for children with life-threatening illness. Pediatr Clin North Am 2014;61: 761–783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Feudtner C, Womer J, Augustin R, et al. Pediatric palliative care programs in children’s hospitals: a cross-sectional national survey. Pediatrics 2013;132:1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Friebert S, Williams C. NHPCO’S facts and figures: Pediatric palliative and hospice care in America. Alexandria, VA: NHPCO, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaye E, Rubenstein J, Levine D, et al. Pediatric palliative care in the community. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:315–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boyden JY, Curley MAQ, Deatrick JA, Ersek M. Factors associated with the use of U.S. community-based palliative care for children with life-limiting or life-threatening illnesses and their families: an integrative review. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:117–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindley L, Mark B, Lee SYD. Providing hospice care to children and young adults: a descriptive study of end-of-life organizations. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2009;11:315–323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carroll JM, Torkildson C, Winsness JS. Issues related to providing quality pediatric palliative care in the community. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54:813–827. xiii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindley LC, Kieim-Malpass J. Quality of paediatric hospice care for children with and without multiple complex chronic conditions. Int J Palliat Nurs 2017;23:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donnelly JP, Huff SM, Lindsey ML, McMahon KA, Schumacher JD. The needs of children with life-limiting conditions: a healthcare-provider-based model. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2005;22:259–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Contro N, Larson J, Scofield S, Sourkes B, Cohen H. Family perspectives on the quality of pediatric palliative care. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2002;156:14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9155–9161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyer EC, Ritholz MD, Burns JP, Truog RD. Improving the quality of end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit: parents’ priorities and recommendations. Pediatrics 2006;117:649–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weidner NJ, Cameron M, Lee RC, et al. End-of-life care for the dying child: what matters most to parents. J Palliat Care 2011;27:279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andresen EM, Seecharan GA, Toce SS. Provider perceptions of child deaths. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158: 430–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malcolm C, Knighting K, Forbat L, Kearney N. Prioritisation of future research topics for children’s hospice care by its key stakeholders: a Delphi study. Palliat Med 2009;23: 398–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thienprayoon R, Grossoehme D, Humphrey L, et al. “There’s just no way to help, and they did.” Parents name compassionate care as a new domain of quality in pediatric home-based hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Med 2020; 23:767–776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thienprayoon R, Mark MSJ, Grossoehme D. Provider-prioritized domains of quality in pediatric home-based hospice and palliative care: a study of the Ohio Pediatric Palliative Care and end-of-Life Network. J Palliat Med 2018;31:290–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Widger KA, Wilkins K. What are the key components of quality perinatal and pediatric end-of-life care? A literature review. J Palliat Care 2004;20:105–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, 4th ed. Richmond, VA: National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trevelyan EG, Robinson PN. Delphi methodology in health research: how to do it? Euro J Integr Med 2015;7: 423–428. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyden J, Ersek M, Deatrick J, et al. Developing a parent-reported measure of experiences with home-based pediatric palliative and hospice care: a multi-method, multi-stake-holder approach. In development. BMC Palliat Care. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feudtner C, Friebert S, Jewell J. Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics 2013;132:966–972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Field MJ, Behrman RE. When children die: Improving palliative and end-of-life care for children and their families. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2003: 419–420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization (NHPCO). Standards of practice for pediatric palliative care. Alexandria, VA: NHPCO, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Widger K, Brennenstuhl S, Duc J, Tourangeau A, Rapoport A. Factor structure of the Quality of Children’s Palliative Care Instrument (QCPCI) when completed by parents of children with cancer. BMC Palliat Care 2019;18. 10.1186/s12904-019-0406-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Courageous Parents Network. Available from https://courageousparentsnetwork.org/. Accessed April 23, 2020.

- 30.Gomes B, de Brito M, Sarmento VP, et al. Valuing attributes of home palliative care with service users: a pilot discrete choice experiment. J Pain Symptom Manage 2017; 54:973–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huynh E, Coast J, Rose J, Kinghorn P, Flynn T. Values for the ICECAP-Supportive Care Measure (ICECAP-SCM) for use in economic evaluation at end of life. Soc Sci Med 2017;189:114–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mangham LJ, Hanson K, McPake B. How to do (or not to do) … designing a discrete choice experiment for application in a low-income country. Health Policy Plan 2009; 24:151–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryan M, Gerard K, Amaya-Amaya M. Using discrete choice experiments to value health and health care. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feudtner C, Walter JK, Faerber JA, et al. Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatr 2015; 169:39–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sawtooth Software. Maximum difference scaling: improved measures of importance and preference for segmentation. 2003. Available from https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/support/technical-papers/maxdiff-best-worst-scaling/maximum-difference-scaling-improved-measures-of-importance-and-preference-for-segmentation-2003. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 36.Louviere JJ, Flynn TN, Carson RT. Discrete choice experiments are not conjoint analysis. J Choice Model 2010;3: 57–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chrazan K, Orme B. Applied MaxDiff: A practitioner’s guide to best-worst scaling. Provo, UT: Sawtooth Software, Inc., 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sawtooth Software. Aggregate score estimation via logit analysis. 2018. Available from https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/help/lighthouse-studio/manual/maxdiff_aggregate_logit_analysis.html. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 39.Sawtooth Software. The MaxDiff system technical paper. 2013. Available from https://www.sawtoothsoftware.com/support/technical-papers/maxdiff-best-worst-scaling/maxdiff-technical-paper-2013. Accessed June 5, 2020.

- 40.Agresti A, Finlay B. Statistical methods for the social sciences, 4th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Bekker-Grob EW, Donkers B, Jonker MF, Stolk EA. Sample size requirements for discrete-choice experiments in healthcare: a practical guide. Patient 2015;8:373–384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lancsar E, Louviere J. Conducting discrete choice experiments to inform healthcare decision making. Pharmacoeconomics 2008;26:661677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Flynn TN, Louviere JJ, Peters TJ, Coast J. Best-worst scaling: what it can do for health care research and how to do it. J Health econ 2007;26:171–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jalmsell L, Kreicbergs U, Onelov E, Steineck G, Henter J-I. Symptoms affecting children with malignancies during the last month of life: a nationwide follow-up. Pediatrics 2006;117:1314–1320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Ullrich C, et al. Quality of life in children with advanced cancer: a report from the PediQUEST study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2016;52: 243–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schmidt P, Otto M, Hechler T, et al. Did increased availability of pediatric palliative care lead to improved palliative care outcomes in children with cancer? J Palliat Med 2013; 16:1034–1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med 2000; 342:326–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kersun LS, Shemesh E. Depression and anxiety in children at the end of life. Pediatr Clin North Am 2007;54: 691–708. xi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Theunissen JM, Hoogerbrugge PM, Achterberg TV, et al. Symptoms in the palliative phase of children with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;49:160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ 2006;174:627–633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Namisango E, Bristowe K, Allsop MJ, et al. Symptoms and concerns among children and young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions: a systematic review highlighting meaningful health outcomes. Patient 2019;12: 15–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stevenson M, Achille M, Lugasi T. Pediatric palliative care in Canada and the United States: a qualitative metasum-mary of the needs of patients and families. J Palliat Med 2013;16:566–577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vohra JU, Brazil K, Hanna S, Abelson J. Family perceptions of end-of-life care in long-term care facilities. J Palliat Care 2004;20:297–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Meyer EC, Burns JP, Griffith JL, Truog RD. Parental perspectives on end-of-life care in the pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med 2002;30:226–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singer P, Martin D, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: patients’ perspectives. JAMA 1999;281:163–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thienprayoon R, Marks e, Funes M, et al. Perceptions of the pediatric hospice experience among English- and Spanish-speaking families. J Palliat Med 2016;19:30–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng NT, Li Q, Hanson LC, et al. Nationwide quality of hospice care: findings from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services hospice quality reporting program. J Pain Symptom Manage 2018;55:427–432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Meeske KA, Patel SK, Palmer SN, Nelson MB, Parow AM. Factors associated with health-related quality of life in pediatric cancer survivors. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2007;49: 298–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kreicbergs U, Valdimarsdottir U, Onelov E, et al. Care-related distress: a nationwide study of parents who lost their child to cancer. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:9162–9171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.van der Geest IMM, Darlington A, Streng IC, et al. Parents’ experiences of pediatric palliative care and the impact on long-term parental grief. J Pain Symptom Manage 2014; 47:1043–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Homer CJ, Marino B, Cleary PD, et al. Quality of care at a children’s hospital: the parent’s perspective. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1999;153:1123–1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cohen E, Lacombe-Duncan A, Spalding K, et al. Integrated complex care coordination for children with medical complexity: a mixed-methods evaluation of tertiary care-community collaboration. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12: 366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cady RG, Belew JLJC. Parent perspective on care coordination services for their child with medical complexity. Children (Basel) 2017;4:45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Baker JN, Levine DR, Hinds PS, et al. Research priorities in pediatric palliative care. J Pediatr 2015;167:467–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lipkin P, Alexander J, Cartwright J. Care coordination in the medical home: integrating health and related systems of care for children with special health care needs. Pediatrics 2005;116:1238–1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Friedrichsdorf SJ, Postier A, Dreyfus J, et al. Improved quality of life at end of life related to home-based palliative care in children with cancer. J Palliat Med 2015;18:143–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bona K, Bates J, Wolfe J. Massachusetts’ Pediatric Palliative Care Network: successful implementation of a novel state-funded pediatric palliative care program. J Palliat Med 2011;14:1217–1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Knapp CA, Madden VL, Curtis CM, et al. Partners in care: together for kids: Florida’s model of pediatric palliative care. J Palliat Med 2008;11:1212–1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ronis S, Grossberg R, Allen R, Hertz A, Kleinman L. Estimated nonreimbursed costs for care coordination for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 2019;143: e20173562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Coller R, Ehlenbach M. Making time to coordinate care for children with medical complexity. Pediatrics 2019;143: e20182958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hexem KR, Mollen CJ, Carroll KW, Lanctot DA, Feudtner C. How parents of children receiving pediatric palliative care use religion, spirituality, or life philosophy in tough times. J Palliat Med 2011;14:39–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wiener L, McConnell DG, Latella L, Ludi E Cultural and religious considerations in pediatric palliative care. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:47–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Davies B, Brenner P, Orloff S, Sumner L, Worden W. Addressing spirituality in pediatric hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Care 2002;18:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Davies B, Contro N, Larson J, Widger K. Culturally-sensitive information-sharing in pediatric palliative care. Pediatrics 2010;125:e859–e865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gaab E, Owens G, MacLeod R. Siblings caring for and about pediatric palliative care patients. J Palliat Med 2014; 17:62–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eaton Russell C, Widger K, Beaune L, et al. Siblings’ voices: a prospective investigation of experiences with a dying child. Death Stud 2018;42:184–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Verberne LM, Kars MC, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, et al. Aims and tasks in parental caregiving for children receiving palliative care at home: a qualitative study. Eur J Pediatr 2017;176:343–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mooney-Doyle K, Deatrick JA. Parenting in the face of childhood life-threatening conditions: the ordinary in the context of the extraordinary. Palliat Support Care 2016;14: 187–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hill DL, Miller VA, Hexem KR, et al. Problems and hopes perceived by mothers, fathers and physicians of children receiving palliative care. Health expect 2015;18: 1052–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hinds PS, Burghen EA, Pritchard M. Conducting end-of-life studies in pediatric oncology. West J Nurs Res 2007;29: 448–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Macdonald ME, Chilibeck G, Affleck W, Cadell S. Gender imbalance in pediatric palliative care research samples. Palliat Med 2010;24:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Knapp CA, Madden VL, Curtis C, Sloyer PJ, Shenkman EA. Assessing non-response bias in pediatric palliative care research. Palliat Med 2010;24:340–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cohen LL. Racial/ethnic disparities in hospice care: a systematic review. J Palliat Med 2008;11:763–768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Gans D, Hadler MW, Chen X, et al. Impact of a pediatric palliative care program on the caregiver experience. J Hosp Palliat Nurs 2015;17:559–565. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Vollenbroich R, Duroux A, Grasser M, et al. Effectiveness of a pediatric palliative home care team as experienced by parents and health care professionals. J Palliat Med 2012; 15:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]