Abstract

The isolation of cellulose has found considerable applications recently due to its attractive characteristics. Cellulose from Albizia gummifera of different size classifications (425 μm–599 μm and 600 μm–849 μm) was investigated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), scanning electron microscopy (SEM), and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) analyses. The crystal plane of the preferred orientation was at (020) for the most prominent peaks. The two size classifications have a strong broad peak around 3320 cm−1 (425 μm–599 μm), and 3330 cm−1 (600 μm–849 μm), which corresponds to a different stretching mode of O–H. High percentages of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) were noticed among the elements observed in the two size classifications. The crystallinity index (CrI) obtained for the two sizes were 61.1% for 425–599 μm, and 55.8% for 600 μm–849 μm. The 425 μm–599 μm size classification had a greater crystallinity index than the 600 μm–849 μm size classification, which indicates a stronger capacity for reinforcing. These particles were also effective as fillers in composite materials. The results revealed that Albizia gummifera cellulose possessed promising potential for device applications and capable of being used in the preparation of composite materials.

Keywords: Wood, Cellulose, Crystalline index, Size classifications, XRD, SEM, FTIR

Wood; Cellulose; Crystalline index; Size classifications; XRD; SEM; FTIR.

1. Introduction

The geometric increase in the world population has led to environmental degradation (deforestation) caused by industrial activities that invariably affect the increasing amount of waste materials (natural or synthetic) in the environment.

Wood dust has been identified as waste that sometimes poses health risk to human existence. However, studies have been conducted on wood dust materials with interesting potential applications (Oluyamo and Adekoya 2015; Oluyamo et al., 2017a). Wood is a combination of hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin, together with smaller amounts of pectic substances, that have been widely used for years due to its availability in building and other industries (Oluyamo and Adekoya 2015; Oluyamo et al., 2017b; Adekoya et al., 2018; Lu et al., 2021).

One of the major constituents or parts of lignocelluloses is cellulose. It is a semicrystalline polysaccharide, a polymeric component containing from 4 % to 50 % cellulose, the macromolecules of which are nanofibrils with a width of 3 nm–5 nm. There are regions in each nanofibril where the arrangement of cellulose is highly crystalline and amorphous (Seddiqi et al., 2021). Promising results on cellulose have also been obtained in several areas of industrial applications that have served as a significant improvement to the economic development in many countries (Oluyamo and Adekoya, 2021).

Cellulose can be modified by physical, chemical, or biological means depending on the demand in industry. The modification of this polymer affects its properties and behavior (Liyanage et al., 2021). The isolation of cellulose has mainly been done by sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. Pulping the sample with a solution of concentrated NaOH transforms the cellulose to sodium cellulose and then reverts it to cellulose after washing thoroughly with distilled water. During digestion, strong hydrogen intermolecular bonding (H-bonding) is destroyed to form sodium cellulose.

However, the effect of size classifications on the mechanical performance of materials cannot be overemphasized. This effect of size classifications greatly affects other parameters (crystalline cellulose, specific gravity, etc.) in predicting the mechanical properties of cellulose material. To an extent, the size classifications affect both the physical and mechanical properties of the cellulose fibres. It also influences the mechanical properties of materials, such as Young's modulus, shear modulus, yielding stress, fracture toughness, etc (Joda et al., 2022).

Similarly, the crystallinity index is an important crystalline structure of cellulose parameters that has a roles in both accessibility and the determination of the strength of materials (Madhushani et al., 2021). Several methods have been used to determine the crystallinity index of cellulose due to its uniqueness in interpreting the structural changes in cellulose after physicochemical and biological treatments (Zhang et al., 2021). The effects of crystallinity on mechanical properties vary depending on the state of the polymer's amorphous regions. In addition, Tsuji and Ikada (2016) investigated the effect of crystallinity on the physical properties and morphologies of poly (Llactide). The result shows that the tensile strength increased with increasing crystallinity, behaving similarly to Young's modulus.

Various analysis techniques have been used for the characterization of cellulose. However, X-ray diffraction (XRD) gives detailed and comprehensive information on crystallinity index, crystalline size, and interplanar spacing (French and Santiago, 2013; Lee and Mani, 2017; Zhao et al., 2017; Adekoya et al., 2018), while useful information relating to hydrogen bonding during crystal transformation is easily obtained by Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Schenzel et al., 2005; Agarwal et al., 2010).

Studies available on cellulose focus on its preparation, properties, and applications (Ago et al., 2016; Horseman et al., 2017; Visanko et al., 2017; Eichhorn et al., 2022). Nonetheless, information about the properties of cellulose of different size classifications using the same pretreatment procedure is scarce. Recent research revealed that different size classification have effects on the properties of materials (Adekoya et al., 2018; Oluyamo and Adekoya 2021).

Consequently, it is believed that the use of cellulose as a composite material will depend to a large extent on the size classifications. Understanding this will give an insight into the influence of size classifications on materials in determining the crystallinity index, crystalline size, and potential for device utilization and applications.

Therefore, the present research is expected to establish the influence of size classifications on the crystallinity index of albizia gummifera cellulose and establish it uses as composite materials.

2. Experiments and methods

2.1. Methods

Albizia gummifera sample was harvested from different sawmills in Akure, Akure local government area of Ondo State, Nigeria. The sample was pulverized and sieved into 425 μm–599 μm and 600 μm–849 μm sizes with the aid of a mechanical sieve shaker (RX-94 duo Model; W.S. Tyler, Mentor, OH, USA) at the wood laboratory of the Federal University of Technology, Akure, Nigeria as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of the isolated Cellulose (Adekoya et al., 2018).

Samples were pretreated for the removal of hemicellulose and lignin as previously reported by Adekoya et al. (2018). The wood dust was treated at 90 °C with 20 % NaOH for 90 min with a liquor to wood ratio of 20:1 in a bath under atmospheric pressure. After digestion, the treated sample was filtered, washed thoroughly with water, oven-dried for 6 h at 105 °C to a constant gravimetric weight, and stored in a polythene bag for further processing. Thereafter, 20 g of the dried treated sample was placed in a flask, then 200 mL of hot (100 °C) water was added, along with 12 g of NaClO2 and 3 mL of acetic acid, and then covered and intermittently stirred for 30 min at 70 °C in a water bath. After the first 30 min, the same quantity of NaClO2 (12 g) and acetic acid (3 mL) were added again and intermittently stirred and maintained for another 30 min before switching the bath off. The samples were allowed to stay in the water bath for 24 h before filtration and washing thoroughly with water. The sample obtained was dried at 105 °C to a constant gravimetric weight and the image is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Cellulose extraction image of Albizia gummifera.

2.2. Test

The cellulose samples were further characterized by XRD (Philips PW 3170 X’PERT Pro diffractometer, Philips Analytical, Almelo, Netherlands), scanning electron microscopy (SEM; FEI NOVA 200 NanoSEM Equipment, FEI Company, Hillsboro OR, USA) with accelerating voltage of up to 30 kV, FTIR (Thermo Nicolet 5700 FTIR Spectrometer, Nicolet, Madison, WI, USA), and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX, FEI NOVA 200 NanoSEM Equipment, FEI Company, Hillsboro Oregon, USA) spectroscopy analyses.

The crystallinity index (CrI) of the isolated cellulose was obtained from the equation established by Segal et al. (1959) with intensity diffraction (Iam) and maximum intensity (I020) at 18° (2θ):

| (1) |

The crystalline size (L) corresponds to the diffraction plane of Full width at half maximum (H) at Bragg's angle and given as Eq. (2),

| (2) |

where, K is a constant and is equal to 0.91.

The inter-planar spacing (d) was calculated from Eq. (3),

| (3) |

where λ = 0.154 nm, which is the wavelength of the incident, and n is the order of reflection.

The surface chains (X) of thickness (h = 0.57 m) of the isolated cellulose can be obtained using Eq. (4):

| (4) |

The crystalline structures (Z) can be calculated from Eq. (5),

| (5) |

where nm) and (nm) are the d-spacing of Iβ () and Iβ (110) peaks respectively.

The energy of hydrogen bonds (EH) for the OH stretching bonds was obtained using Eq. (6),

| (6) |

where k is a constant (1/k = 2.625 × 102 kJ), γo and γ are the standard OH groups (3560 cm−1) and bonded OH groups frequencies, respectively.

The distance (R) of the hydrogen bond was calculated in Eq. (7),

| (7) |

where Δγ = γo – γ, and γ is the stretching frequency observed in the infrared spectrum and γo is the monomeric OH stretching frequency, which is taken to be 3600 cm−1 of the sample.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. XRD analysis

The X-ray diffraction pattern of the samples in Figures 3a and 3b revealed two prominent peaks at 2θ = 22.241° for 425 μm–599 μm and 22.107° for 600 μm–849 μm of the crystalline size of 1.742 nm and 1.748 nm respectively. The sharp peaks of the diffraction pattern indicate that the samples were made up of cellulose (Adekoya et al., 2018).

Figure 3.

a. X-ray diffraction patterns of Albizia gummifera of 425 μm to 5999 μm size. b. X-ray diffraction patterns of Albizia gummifera of 600 μm–849 μm size.

The values of the CrI increased as the size classifications decreased. The CrI of the two classifications were 61.1% and 55.8% for 425 μm–599 μm and 600 μm–849 μm, respectively, with crystal orientation at (020) plane. Other parameters are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Band 2θ (°) and interplanar spacing obtained from the cellulose samples.

| Classification (μm) | () |

(110) |

(004) |

(020) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2θ | d (Å) | 2θ | d(Å) | 2θ | d (Å) | 2θ | d (Å) | |

| 425 to 599 | 14.972 | 5.910 | 16.910 | 5.240 | 35.175 | 2.549 | 22.241 | 3.994 |

| 600 to 849 | 14.904 | 5.937 | 17.010 | 5.208 | 35.075 | 2.556 | 22.107 | 4.018 |

The relatively high percentage in crystalliity index of 425 μm–599 μm might be associated with the reduction in the corresponding amorphous state of the material due to the probable dissociation of the bonds as a result of pulping. Moreover, this can also be due to significant increase in surface-area-to-volume ratio, chemical reactivity, or electron (quantum) confinement (Gumuskaya et al., 2003; Oluyamo and Adekoya 2021). Besides, high crystallinity index is associated to increase stiffness, rigidity and strength of the isolated cellulose. As a result, 425 μm–599 μm size classification has high potential mechanical property and reinforcing capability than 600 μm–849 μm size classification.

In addition, high crystallinity index in 425 μm–599 μm indicates that it is more crystalline and has a more regular aligned chain than 600 μm–849 μm. Also, the reinforcing capability of materials is a measure of their crystallinity index. An increase in crystallinity index increases the reinforcing of materials, and this could be applied as fillers in composite materials. Consequently, the cellulose sample of 425 μm–599 μm has better reinforcing capability than the 600 μm–849 μm size range.

The crystalline interior chain X was calculated as 0.04 for the size classifications. The results obtained indicate that the proportion of crystallite interior chains, X, was the same for both samples examined.

The values of the crystalline structures (Z) obtained were -21.085 (425 μm–599 μm) and -13.628 (600 μm–849 μm) for the two size classifications. These values for the two classifications were less than zero, which indicate that the isolated cellulose samples show Iβ (monoclinic) dominancy.

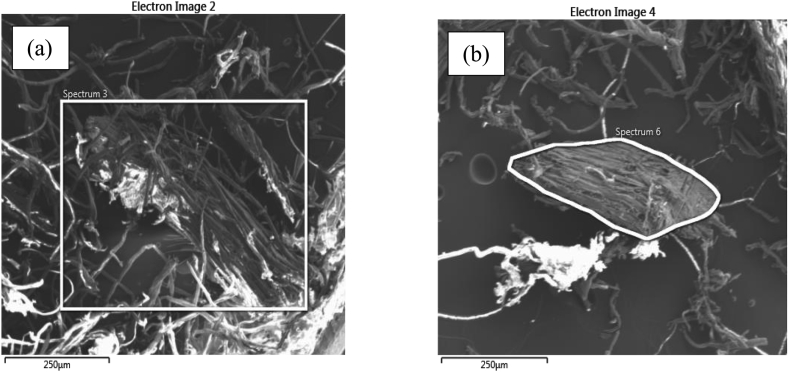

3.2. SEM analysis

The morphology of the isolated sample of the two size classifications were characterized using SEM analysis as shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

SEM micrographs of Albizia gummifera at (a) 425μm to 599 μm and (b) 600 μm to 849μm.

After successful removal of the non-cellulosic component during pulping and bleaching processing, a fibre-like shape for the two size classifications was observed. This pretreatment assisted in increasing the fibre surface area and exposing the polysaccharides to an acidic medium. This increase in the surface area creates a good bond with the natural fibre. The chemicals used during the pulping and bleaching helped in removing the non-cellulosic material and in increasing the mechanical strength of the cellulose fibril-reinforced composites.

The elemental composition of isolated cellulose was investigated using the EDX technique attached to the SEM.

The EDX spectra (Figure 5) were ascribed to the energy levels. High percentages of carbon (C) and oxygen (O) were noticed among the elements observed in the two size classifications. The presence of sodium and silicon may be due to the chemicals used during the pulping (NaOH) and the residual lignin.

Figure 5.

EDX spectrum of (a) 425 μm–599 μm and (b) 600 μm–849 μm size classifications.

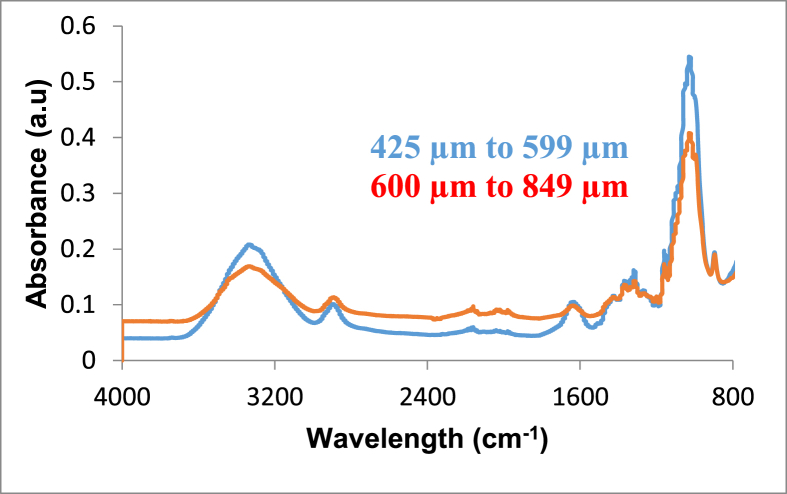

3.3. FTIR analysis

The FTIR spectra group for the isolated cellulose of the size classifications studied was shown with the spectra analyses in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

FTIR spectra of Albizia gummifera.

It was observed that the absorption had a strong broad peak around 3320 cm−1 for 425 μm–599 μm and 3330 cm−1 for 600 μm–849 μm size classifications, which corresponds to a different stretching mode of O–H while the peak around 2890 cm−1 corresponded to the stretching vibration of C–H. This indicates functional groups were found in cellulose materials (Kamphunthong et al., 2012; Han et al., 2013).

The band around 1160 cm−1 peak relates to anti-symmetric stretch bridging of C–O–C groups. The absorption band near 849 cm−1 peak corresponds to C–O–C symmetric stretching of β (1⟶4)-glycosidic linkage.

The bands around 1020 cm−1, 1090 cm−1, 1200 cm−1, and 1300 cm−1 were ascribed to C–O, C–C, C–O–H plane bending, and CH2 wagging vibrations, respectively, in the isolated cellulose. However, due to the absorbed water experienced, the peak around 1610 cm−1 corresponded to OH bending.

The hydrogen bond is one of the key factors responsible for the various properties of cellulose. Thus, a higher interaction between the adjacent chains resulted in closer cellulose chains. This will result in fibres with high mechanical properties (Kempaiah et al., 2020). This is essential in composite formulations before investigating their potential as reinforcing fillers.

The intra-molecular hydrogen bonds appear around 3320 cm−1 and 3320 cm−1 for the two size classifications. These values obtained were similar to other values for cellulose fibre (Cichosz and Masek, 2020). Additionally, celluloses within these bands were dominated by monoclinic cellulose Iβ.

The hydrogen bond energy (EH) and distance (R) of the hydrogen bond for the two size classifications studied were 17.770 kJ and 2.777 Å for 425 μm–599 μm and 16.959 kJ and 2.779 Å for 600 μm–849 μm size classifications using Eqs. (6) and (7), respectively. The values obtained showed that the fibre has high intra-molecular hydrogen bond, which is ascribed to low hydrogen bond distance. The 425 μm–599 μm size classification has high hydrogen bond energy, which resulted to higher mechanical properties than the 600 μm–899 μm size classification.

4. Conclusions

The study examined the characterization of cellulose from Albizia gummifera of different size classifications for device utilization and application.

The CrI values obtained were 61.1% for 425 μm–599 μm and 55.8% for 600 μm–849 μm with preferred orientation at (020) plane for the most prominent peak. The high value of the crystallinity index of 425 μm–599 μm showed that the size classification has higher reinforcing capability and could be applied as fillers in composite materials than that of the 600 μm–849 μm classification. The intra-molecular hydrogen bonds appear around 3320 cm−1 for 425–599 μm and 3330 cm−1 for 600–849 μm size classifications. The hydrogen bond energy (EH) and distance (R) of the hydrogen bond for the two size classifications were 17.770 kJ and 2.777 Å for 425 μm–599 μm and 16.959 kJ and 2.779 Å for 600 μm–849 μm, which indicates fibres had a high intra-molecular hydrogen bond ascribed to low hydrogen bond distance.

Declarations

Author contribution statement

Mathew Adefusika Adekoya, Shuhuan Liu, Sunday Samuel Oluyamo: Conceived and designed the experiment; Performed the experiments; Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Oyenike Tosin Oyeleye: Analyzed and interpreted the data; Contributed reagents, materials, analysis tools or data; Wrote the paper.

Rasheed Toyin Ogundare: Conceived and designed the experiments; Performed the experiments; Wrote the paper.

Funding statement

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.

Declaration of interests statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Additional information

No additional information is available for this paper.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the Federal of University Technology, Akure, Ondo State, Nigeria, and Edo State University Uzairue, Auchi, Edo State, Nigeria for providing enablement during the early stage of the research.

References

- Adekoya M.A., Oluyamo S.S., Oluwasina O.O., Popoola A.I. Structural characterization and solid state properties of thermal insulating cellulose materials of different size classifications. Bioresources. 2018;13(1):906–917. [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal U.P., Reiner R.S., Ralph S.A. Cellulose I crystallinity determination using FT– Raman spectroscopy: univariate and multivariate methods. Cellulose. 2010;17(4):721–733. [Google Scholar]

- Ago M., Ferrer A., Rojas O.J. Starch-based biofoams reinforced with lignocellulose nanofibrils from residual palm empty fruit bunches: water sorption and mechanical strength. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2016;4(10):5546–5552. [Google Scholar]

- Eichhorn S.J., Etale A., Wang J., Berglund L.A., Li Y., Cai Y., Chen C., Cranston E.D., Johns M.A., Fang Z., Li G., Hu L., Khandelwal M., Lee K.Y., Oksman K., Pinitsoontorn S., Quero F., Sebastian A., Titirici M.M., Xu Z., Vignolini S., Frka-Petesic B. Current international research into cellulose as a function nanomaterial for advanced applications. J. Mater. Sci. 2022;57:5697–5767. [Google Scholar]

- French A.D., Santiago C.M. Cellulose polymorphy, crystallite size, and the Segal crystallinity index. Cellulose. 2013;20(1):583–588. [Google Scholar]

- Gumuskaya E., Usta M., Kirci H. The effects of various pulping conditions on crystalline structure of cellulose in cotton linters. Polym. Degrad. Stabil. 2003;81(3):559–564. [Google Scholar]

- Han J.Q., Zhou C.J., Wu Y.Q., Liu F.Y., Wu Q.L. Self-assembling behavior of cellulose nanoparticles during freeze-drying: effect of suspension concentration, particle size, crystal structure, and surface charge. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14(5):1529–1540. doi: 10.1021/bm4001734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horseman T., Tajvidi M., Diop C.I.K., Gardner D.J. Preparation and property assessment of neat lignocellulose nanofibrils (LCNF) and their composite films. Cellulose. 2017;24(9):2455–2468. [Google Scholar]

- Jorda J., Kain G., Barbu M.-C., Koll B., Petutschnigg A., Kral P. Mechanical properties of cellulose and flax fiber unidirectional reinforced plywood. Polymers. 2022;14:843–858. doi: 10.3390/polym14040843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamphunthong W., Hornsby P., Sirisinha K. Isolation of cellulose nanofibers from para rubberwood and their reinforcing effect in poly(vinyl alcohol) composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2012;125(2):1642–1651. [Google Scholar]

- Kempaiah R., Gurappa G., Tomar R., Poletto M., Luiz H., Junior O., Annadurai V., Somashekar R. FTIR and WAXS Studies on six vegetal fibers. Cellul. Chem. Technol. 2020;54(3-4):187–197. [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Mani S. Mechanical pretreatment of cellulose pulp to produce cellulose nanofibrils using a dry grinding method. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2017;104:179–187. [Google Scholar]

- Liyanage S., Acharya S., Parajuli P., Shamshina J.L., Abidi N. Production and surface modification of cellulose bioproducts. Polymers. 2021;13(19):3433–3461. doi: 10.3390/polym13193433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y., He Q., Fan G., Cheng Q., Song G. Extraction and modification of hemicellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: a review. Green Process. Synth. 2021;10(1):779–804. [Google Scholar]

- Madhushani W.H., Priyadarshana R.W.I.B., Ranawana S.R.W.M.C.J.K., Senarathna K.G.C., Kaliyadasa P.E. Determining the crystallinity index of cellulose in chemically and mechanically extracted banana fiber for the synthesis of nanocellulose. Natural Fibers. 2021;18:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Oluyamo S.S., Adekoya M.A. Effect of dynamic compression on the thermal conductivities of selected wood products of different particle sizes. Int. Res. J. Pure Appl. Phys. 2015;3(1):22–29. [Google Scholar]

- Oluyamo S.S., Aramide T.M., Adekoya M.A., Famutmi O.F. Variation of bulk and particle thermal properties of some selected wood materials for solar device applications. IOSR J. Appl. Phys. 2017;9(3):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- Oluyamo S.S., Adekoya M.A., Bello O.R. Dynamic compression and thermo - physical properties of some wood particles in South Western Nigeria. Pak. J. Scient. Ind. Res. Series A: Phys. Sci. 2017;60(2):79–84. [Google Scholar]

- Oluyamo S.S., Adekoya M.A. Characterization of cellulose nanoparticles for materials device applications and development. Mater. Today Proc. 2021;38(2):595–598. [Google Scholar]

- Schenzel K., Fischer S., Brendler E. New method for determining the degree of cellulose I crystallinity by means of FT Raman spectroscopy. Cellulose. 2005;12(3):223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Seddiqi H., Oliaei E., Honarkar H., Jin J., Geonzon L.C., Bacabac R.G., Klein-Nulend J. Cellulose and its derivatives: towards biomedical applications. Cellulose. 2021;28(4):1893–1931. [Google Scholar]

- Segal L., Creely J.J., Martin A.E., Conrad C.M. An empirical method for estimating the degree of crystallinity of native cellulose using the X-ray diffractometer. Textil. Res. J. 1959;29:786–794. [Google Scholar]

- Tsuji H., Ikada Y. Properties and morphologies of poly (L-lactide): 1. Annealing condition effects on properties and morphologies of poly (L-lactide) Polymer. 1995;36:2709–2716. [Google Scholar]

- Visanko M., Sirvio J.A., Piltonen P., Sliz R., Liimatainen H., Illikainen M. Mechanical fabrication of high-strength and redispersible wood nanofibers from unbleached ground wood pulp. Cellulose. 2017;24:4173–4187. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang K., Wang W., Zhao K., Ma Y., Wang Y., Li Y. Recent development in foodborne nanocellulose: preparation, properties, and applications in food industry. Food Biosci. 2021;44:101410–101425. Part A) [Google Scholar]

- Zhao D., Yang F., Dai Y., Tao F., Shen Y., Duan W., Zhou X., Ma H., Tang L., Li J. Exploring crystalline structural variations of cellulose during pulp beating of tobacco stems. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017;174:146–153. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data was used for the research described in the article.