Abstract

Objectives

Elevated concentrations of soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) predict progression to severe respiratory failure (SRF) or death among patients with COVID-19 pneumonia and guide early anakinra treatment. As suPAR testing may not be routinely available in every health-care setting, alternative biomarkers are needed. We investigated the performance of C-reactive protein (CRP), interferon gamma-induced protein-10 (IP-10) and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) for predicting SRF or death in COVID-19.

Methods

Two cohorts were studied; one discovery cohort with 534 patients from the SAVE-MORE clinical trial; and one validation cohort with 364 patients from the SAVE trial including also 145 comparators. CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL were measured by the MeMed Key® platform in order to select the biomarker with the best prognostic performance for the early prediction of progression into SRF or death.

Results

IP-10 had the best prognostic performance: baseline concentrations 2000 pg/ml or higher predicted equally well to suPAR (sensitivity 85.0 %; negative predictive value 96.6 %). Odds ratio for poor outcome among anakinra-treated participants of the SAVE-MORE trial was 0.35 compared to placebo when IP-10 was 2,000 pg/ml or more. IP-10 could divide different strata of severity for SRF/death by day 14 in the validation cohort. Anakinra treatment decreased this risk irrespective the IP-10 concentrations.

Conclusions

IP-10 concentrations of 2,000 pg/ml or higher are a valid alternative to suPAR for the early prediction of progression into SRF or death the first 14 days from hospital admission for COVID-19 and they may guide anakinra treatment.

Trial registration.

Keywords: IP-10, Prognosis, COVID-19, Respiratory failure, Anakinra

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CRP, C-reactive protein; HR, hazard ratio; IFN, interferon; IL, interleukin; IP-10, interferon gamma-induced protein-10; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; NPV, negative predictive value; PaO2/FiO2, Fraction of partial pressure of oxygen divided by inspired oxygen air mix; PPV, positive predictive value; ROC, receiver operating characteristics curve; SD, standard deviation; SRF, severe respiratory failure; suPAR, soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor; TNF, tumor-necrosis factor; TRAIL, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand; WHO-CPS, World Health Organization Clinical Progression Scale

1. Introduction

Since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, more than 6 million affected individuals have died [1]. Deaths are due to progression into severe respiratory failure (SRF) requiring invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation [2]. Therefore, early recognition of patients at risk and early start of treatment is an important strategy to prevent progression into SRF. In order to achieve this, early biomarkers of SRF are crucial. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) is the only biomarker so far proven to guide an appropriate immunomodulatory treatment [3], [4]. In the SAVE-MORE trial, patients with elevated concentrations of plasma suPAR, an indicator of endothelial activation by the IL-1 inflammatory pathway, were allocated to treatment with anakinra or placebo in addition to Standard-of-Care (SoC) therapy [5]. Using the World Health Organization Clinical Progression Scale (WHO-CPS) as a measure of clinical efficacy, anakinra treatment had 0.36 odds ratio for poor outcome compared to placebo by day 28. Clinical improvement was associated with significant decrease of progression into SRF. Results of the SAVE-MORE trial led to the approval of anakinra guided by suPAR for the treatment of COVID-19 pneumonia in adults by the European Medicines Agency [6]. The Food and Drug Administration has also recently provided Emergency Use Authorization to anakinra treatment in the United States [7].

As suPAR testing may not be routinely available in every health-care setting, alternative biomarkers easy to perform by non-invasive tests in clinical laboratories, are needed to identify patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who are at risk of SRF. In this context, previous studies have shown calprotectin, soluble interleukin-2 receptors and SCOPE score as potential predictors for the development of SRF and/or death in COVID-19 patients [8], [9], [10]. In order to explore this topic, we used the novel platform (MeMed Key®) which measures the circulating concentrations of three endogenous inflammatory mediators: C-reactive protein (CRP), interferon gamma- induced protein-10 (IP-10), and TNF (tumor necrosis factor)-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) [11], [12], [13]. The platform was originally designed to distinguish between bacterial and viral infection, but recent studies have shown that these biomarkers may be also helpful to predict COVID-19 severity and potentially guide immunomodulatory treatment [14], [15], [16]. We aimed to investigate whether any of these three inflammatory mediators could be used to early predict the risk of progression into SRF and predict response to anakinra treatment. The prediction of risk was performed using samples coming from the phase 3 SAVE-MORE study. Response to anakinra was done using one independent discovery cohort (phase 3 SAVE-MORE study) and one validation cohort (phase 2 SAVE study).

2. Methods

2.1. Patients

The discovery cohort included patients screened for eligibility for the SAVE-MORE study (NCT04680949) [5] and the validation cohort included patients enrolled in the SAVE study (NCT04357366) [4]. The SAVE-MORE trial was approved by the National Ethics Committee of Greece (approval 161/20) and by the Ethics Committee of the National Institute for Infectious Diseases Lazzaro Spallanzani, IRCCS, in Rome (1 February 2021). The SAVE trial was approved by the National Ethics Committee of Greece (approval 38/20). Written informed consent was provided by all patients prior to enrolment in either study.

Both studies had similar inclusion and exclusion criteria. The two studies differed in the design of the intervention. SAVE-MORE was a double-blind randomized clinical trial and study participants were 1:2 randomly allocated to once daily subcutaneous treatment with either placebo or anakinra for 10 days in addition to SoC. The daily dose of anakinra was 100 mg. SAVE was an open-label single-arm non-randomized trial and all study participants were treated with active drug, i.e. anakinra. Daily anakinra dose (100 mg) and duration of anakinra treatment (10 days) were the same as in the anakinra arm of the randomized SAVE-MORE trial. An interim analysis of the first 130 patients of the SAVE trial has been published [4]. Since then, the SAVE trial has been completed with the enrolment of 1,000 patients.

Study participants of both trials were adults of either gender, hospitalized with radiological findings of pneumonia by SARS-CoV-2 and plasma suPAR 6 ng/ml or more. Infection was confirmed by PCR testing. Similar exclusion criteria applied in both studies: non-invasive or mechanical ventilation, stage IV malignancy, any do-not-resuscitate decision, ratio of partial oxygen pressure to fraction of inspired oxygen less than 150, severe hepatic failure, any primary immunodeficiency, neutrophils less than 1500/mm3, oral or intravenous corticosteroids more than 0.4 mg/kg/day of equivalent prednisone the last 15 days, any anti-cytokine biologic treatment the last month, hemodialysis, and pregnancy or lactation.

For the purposes of the current study, only available stored samples of patients of the two cohorts, collected at screening were used for measurement of biomarkers. Available data of patients screened for both studies were demographics, treatment with dexamethasone, severity according to WHO and development of SRF or death by day 14.

2.2. Biomarker measurements

suPAR concentrations were measured in plasma samples using the suPARnostic Quick Triage kit (Virogates) and a point-of-care reader. Serum screening samples were kept refrigerated at −80 °C in the central study lab, which was the Laboratory of Immunology of Infectious Diseases at the 4th Department of Internal Medicine, Attikon University General Hospital. Levels of CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL were measured on a MeMed Key® (MeMed Diagnostics, Tirat Carmel, Israel) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Lower limits of quantitation for CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL were 1 mg/ml, 100 pg/ml and 15 pg/ml respectively.

2.3. Endpoints

The primary endpoint was to identify which of the three studied biomarkers, CRP, IP-10 or TRAIL, is the best predictor of progression of COVID-19 pneumonia to SRF or death by day 14. SRF was defined as PaO2/FiO2 less than 150 necessitating high-flow oxygen or non-invasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation. This analysis was conducted among participants of the SAVE-MORE cohort. Patients allocated to the anakinra and SoC treatment arm were excluded from this analysis to avoid confounding coming from anakinra treatment benefit on progression into SRF/death.

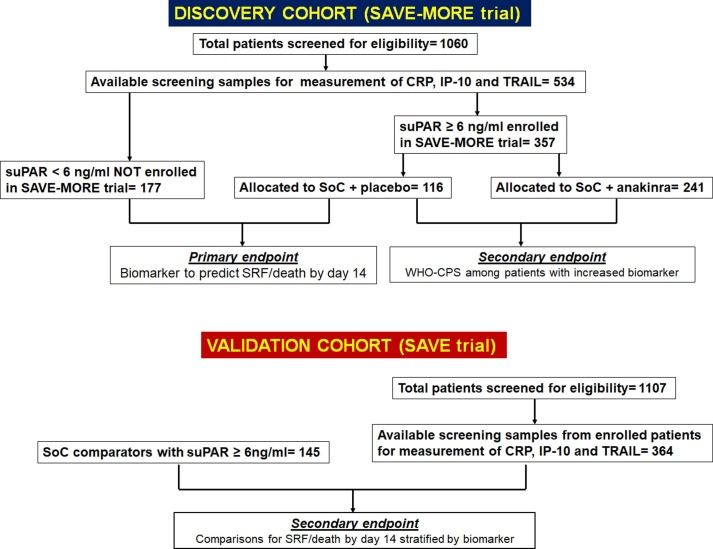

The secondary endpoints were a) the clinical efficacy of anakinra treatment according to the distribution of the 11-point WHO-CPS for patients with biomarker concentrations above the defined cut-offs (this analysis included participants in the SAVE-MORE trial); and b) the impact of anakinra treatment on the progression to SRF/death by day 14 among patients stratified by the concentrations of the biomarker (this analysis included participants in the SAVE trial) (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Study flow chart The discovery cohort was composed of available samples coming from patients who were screened for eligibility for the SAVE-MORE trial. The primary study endpoint aimed to the development of a cut-off concentration of one of the studied biomarkers CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL to early discriminate the risk for progression into SRF/death by day 14. To make this comparison, patients who failed screening because of suPAR less than 6 ng/ml and patients who were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial and were allocated to treatment with placebo and SoC (standard-of-care) were compared. The secondary endpoint was the comparison of the allocation of the 11-point WHO-CPS by day 28 between placebo-treated and anakinra treated patients. For this comparison, only patients with biomarker concentration above the developed cut-off were encountered. The validation cohort was composed by patients who participated in the SAVE trial. The progression into SRF/death by day 14 was compared between patients treated with SoC and anakinra and comparators.Abbreviations CPS: Clinical Progression Scale; CRP: C-reactive protein; IP-10: interferon gamma- induced protein-10; suPAR: soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor; TRAIL: TNF- related apoptosis-inducing ligand; WHO: World Health Organization.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Categorical data were presented as frequencies and confidence intervals (CI); continuous variables with normal distribution as mean with standard deviation (SD). Fisher’s exact test was used for comparison of categorical data whereas Student’s t-test or non-parametric Mann Whitney test were used for the comparison of continuous data, as appropriate. The prognostic capacity of studied biomarkers was evaluated by the area under the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve and 95 %CI. The optimal cut-offs were calculated by the Youden’s index. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV) and negative predictive value (NPV) were calculated by a 2 × 2 table. The areas under the ROC curve were compared by the method of Hanley and McNeil [17]. For the analysis of the impact of anakinra treatment in the distribution of the 11-point WHO-CPS by day 28 among patients with increased biomarkers in the SAVE-MORE trial, multivariate ordinal regression analysis was run. COVID-19 severity, treatment with dexamethasone and body mass index entered as co-variates according to the original statistical analysis plan [5]. For the analysis of the impact of anakinra treatment for progression into SRF/death by day 14 in the SAVE trial, a multivariate Cox forward conditional regression model was used. Biomarker concentrations, COVID-19 severity and dexamethasone treatment entered as co-variates. Adjusted hazard ratio (HR) and 95 %CI were calculated. Any two-sided p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was performed using the software SPSS version 26.0.

3. Results

3.1. Patient population and analysis of the primary endpoint

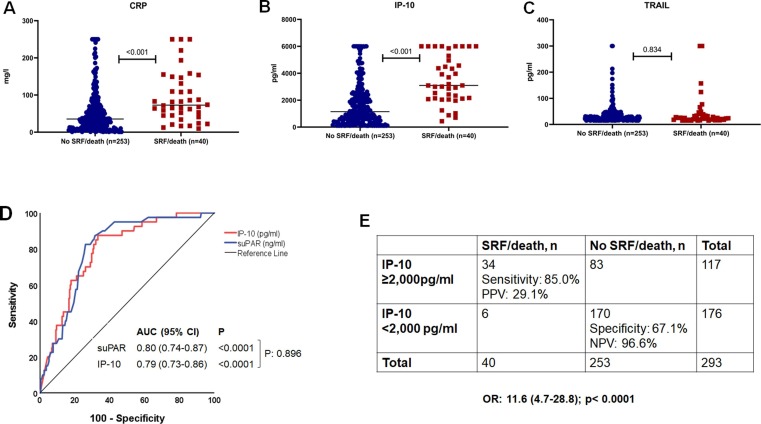

In order to develop prognostic cut-offs for CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL, screening samples from patients who were not enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial because of suPAR less than 6 ng/ml and from patients who were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial and who were allocated to placebo treatment were analyzed. In total, patients of this cohort had a mean age of 58 (±13.6) years, 63.3 % were male and 75.3 % had severe infection (Supplementary Table 1). The concentrations of CRP and IP-10 at screening were higher among the patients who progressed into SRF or died the first 14 days (Fig. 2 A and 2B). In contrast, TRAIL concentrations did not differ between patients with a poor or favorable outcome (Fig. 2C). ROC curve analysis showed that among the three biomarkers, IP-10 concentrations had the best performance for the early progression into SRF or death (Supplementary Fig. 1). IP-10 had equal performance to suPAR (Fig. 2D) and a concentration of 2,000 pg/ml was the best cut-off with sensitivity of 85.0 % and specificity of 67.2 % to predict a poor outcome (Fig. 2E and Supplementary Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Development of IP-10 (interferon gamma- induced protein-10) for the early detection of risk of progression to severe respiratory failure (SRF) or death the first 14 days The analysis includes 293 patients who were screened for eligibility of participation at the SAVE-MORE trial; 177 patients failed screening because they had circulatory concentrations of suPAR (soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor) less than 6 ng/ml; 116 patients had suPAR 6 ng/ml or more, were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial and were allocated to treatment with placebo and standard-of-care.A)Comparison of circulating concentrations of C-reactive protein (CRP) at screening between patients who progressed into SRF/death and patients who did not progress into SRF/death by day 14.B)Comparison of circulating concentrations of IP-10 at screening between patients who progressed into SRF/death and patients who did not progress into SRF/death by day 14.C)Comparison of circulating concentrations of TRAIL (TNF- related apoptosis-inducing ligand) at screening between patients who progressed into SRF/death and patients who did not progress into SRF/death by day 14.D)Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves of IP-10 and suPAR for the early prediction of the risk for progression into SRF or death the first 14 days.E) Prognostic performance of concentrations of IP-10 greater than 2,000 pg/ml for the early prediction of the risk for progression into SRF or death the first 14 days.Abbreviations AUC: area under the curve; CI: confidence intervals; OR: odds ratio NPV: negative predictive value; PPV: positive predictive value.

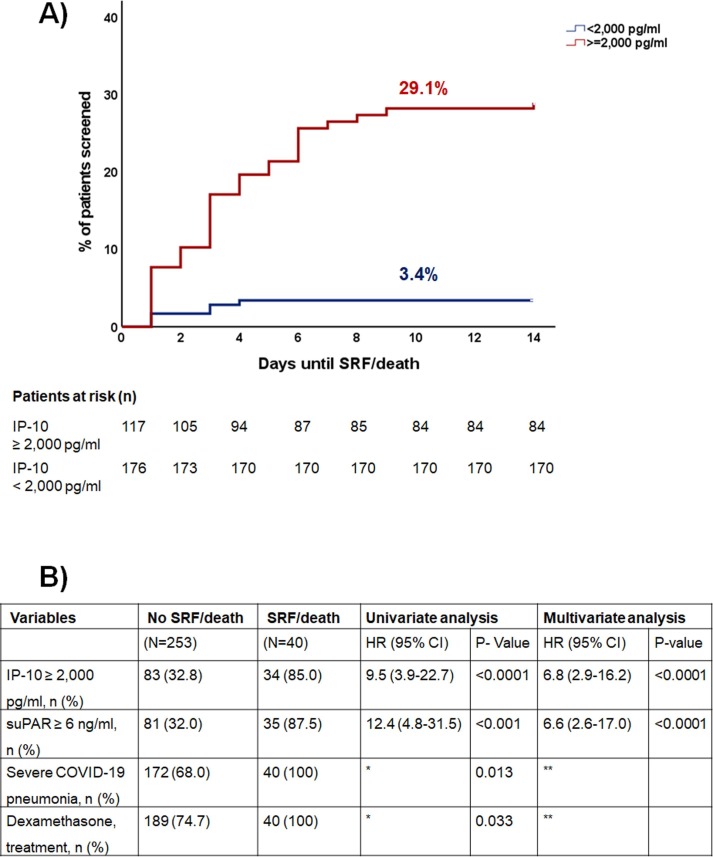

In the discovery cohort, 34 patients (29.1 %) with IP-10 concentrations ≥ 2,000 pg/ml developed SRF or died after 14 days, compared to only 6 patients (3.4 %) with IP-10 concentrations less than 2,000 pg/ml (Fig. 3 A). Multivariate Cox regression analysis among all variables associated with unfavorable prognosis revealed that IP-10 concentrations ≥ 2,000 pg/ml was an independent predictor of progression to SRF or death with adjusted HR 6.8 (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

IP-10 (interferon gamma- induced protein-10) as an independent variable for the early detection of risk of progression to severe respiratory failure (SRF) or death in the first 14 days The analysis includes 293 patients who were screened for eligibility of participation at the SAVE-MORE trial; 177 patients failed screening because they had circulatory concentrations of suPAR (soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor) less than 6 ng/ml; 116 patients had suPAR 6 ng/ml or more, were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial and were allocated to treatment with placebo and standard-of-care.A)Time to progression to SRF or death the first 14 days B) Univariate and multivariate (Cox Forward Conditional) models for the association of IP-10 with early progression to SRF or death the first 14 days *HR cannot be calculated because one value is zero **excluded after two steps of forward analysis Abbreviations CI: confidence intervals; HR: hazard ratio; n: number of patients, suPAR: soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor.

Concentrations of IP-10 ad CRP were positively correlated with the concentrations of suPAR (rs: +0.25; p less than 0.001 and rs: +0.313; p less than 0.0001, respectively); no significant correlation was found between TRAIL and suPAR (rs: −0.074; p: 0.084) (Supplementary Fig. 2).

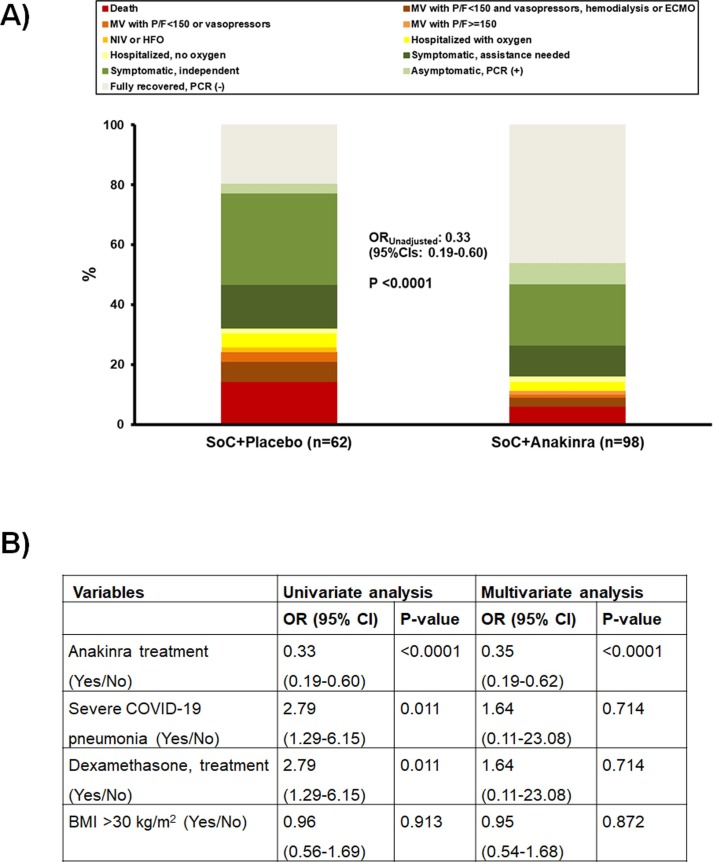

3.2. Discovery cohort: Efficacy of anakinra compared to placebo in patients with IP-10 concentrations higher than 2,000 pg/ml

The primary endpoint of the SAVE-MORE trial was the distribution of the patients to the 11-point WHO-CPS by day 28. Comparisons among the subgroup of patients with IP-10 concentrations ≥ 2.000 pg/ml revealed that randomization to anakinra treatment was associated with 0.35 odds for poor outcome compared to placebo treatment (Fig. 4 ). These patients were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial so as per inclusion requirements, all had suPAR levels of ≥ 6 ng/ml.

Fig. 4.

Efficacy of anakinra treatment among SAVE-MORE participants with IP-10 (interferon gamma- induced protein-10) 2,000 ng/ml or more This analysis involves 160 participants of the randomized SAVE-MORE trial with circulating concentrations of IP-10 2000 pg/ml or more. These patients were enrolled in the SAVE-MORE trial so as per inclusion requirements, all had suPAR levels of ≥ 6 ng/ml.A)Allocation of patients allocated to treatment with placebo and standard-of-care (SoC) and to treatment with anakinra and SoC in the 11-points of the WHO clinical progression scale (WHO-CPS) by day 28.B)Univariate and multivariate analysis of the WHO-CPS by day 28 Abbreviations CI: confidence interval; n: number of patients; OR: odds ratio.

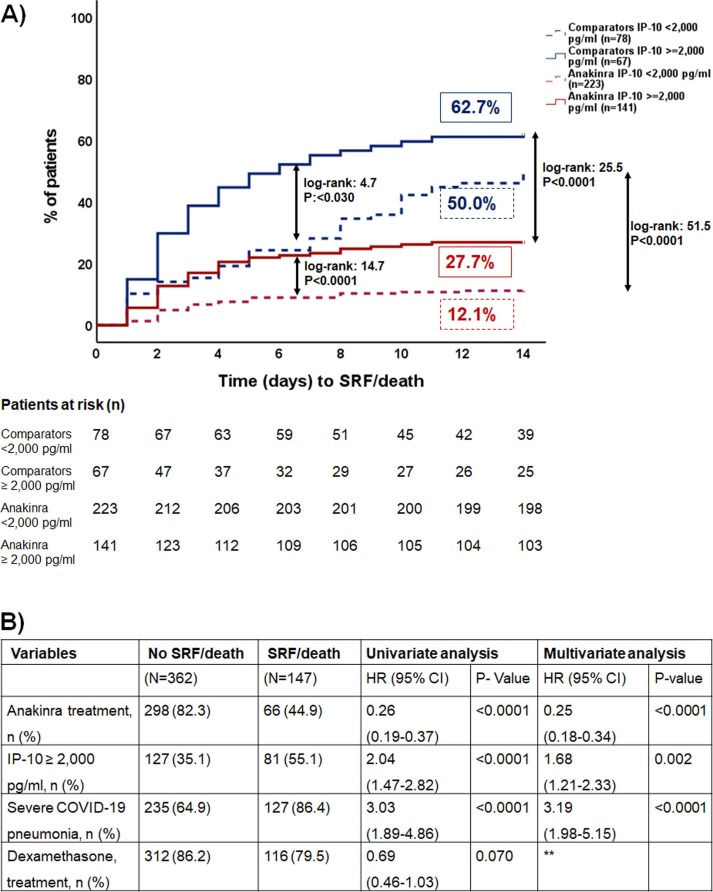

3.3. Validation in SAVE cohort

SAVE trial was open-label non-randomized, and all participants were treated with anakinra and SoC. Studied comparators had suPAR concentrations 6 ng/ml or more and received SoC treatment (Supplementary Table 1). Both comparators and trial participants could be divided into different strata of risk for progression into SRF or death the first 14 days according to the circulating IP-10 concentrations (less than 2,000 pg/ml; 2,000 pg/ml or more) (Fig. 5 A). Anakinra treatment was an independent variable with hazard ratio of 0.25 for risk after multivariate analysis in which concentrations of IP-10, severity and dexamethasone treatment were used as co-variates (Fig. 5B).

Fig. 5.

Validation of the role of IP-10 (interferon gamma- induced protein-10) as an independent variable for the early detection of risk of progression to severe respiratory failure (SRF) or death the first 14 days The analysis includes 364 patients who participated in the SAVE trial and 145 comparators treated with standard-of-care (SoC) therapy. A)Time to progression to SRF or death the first 14 days. Patients are stratified according to the circulating concentration of IP-10. Comparisons by the log-rank test and respective P-values are indicated by the arrows B) Univariate and multivariate (Cox Forward Conditional) models for the association of IP-10 with early progression to SRF or death the first 14 days **excluded after two steps of forward analysis Abbreviations CI: confidence intervals; HR: hazard ratio; n: number of patients.

4. Discussion

In the current study, we showed that IP-10 is a reliable biomarker, with similar performance to suPAR, to predict progression to SRF or death among patients hospitalized with COVID-19 pneumonia. suPAR concentrations ≥ 6 ng/ml have been shown to detect patients with COVID-19 pneumonia at great risk for progression to SRF or death and adequately guide immunomodulatory treatment with anakinra, a recombinant human anti-IL-1 receptor antagonist [3], [4], [5]. In health-care settings in which rapid suPAR concentration measurements may not be easily available, measurement of IP-10 concentrations on a point-of-care platform, such as MeMed Key®, may represent a good alternative. Concentrations of IP-10 ≥ 2,000 pg/ml have a sensitivity 85.0 %, and negative predictive value of 96.6 % for the early detection of progression risk in COVID-19 pneumonia.

IP-10 (also known as CXCL10) is a chemokine secreted from cells stimulated with type I and II interferons (IFNs) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS), behaving as a chemoattractant for activated T cells and monocytes/macrophages. IP-10 is secreted by several cell types, including monocytes, endothelial cells and fibroblasts. Expression of IP-10 is described for many Th1-type inflammatory diseases, where it is thought to play an important role in recruiting activated T cells into the site of tissue inflammation [18]. TRAIL is a transmembrane protein belonging to the TNF superfamily and is expressed on the surface of natural killer (NK) and T cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. TRAIL can be anchored in the membrane or can be released as a soluble protein. Both forms function as trimers and can induce apoptosis, making TRAIL important for the regulation of innate immunity and the homeostasis of memory T cells [19]. It becomes obvious that both IP-10 and TRAIL are viral-induced markers and recent studies have shown that like other viral illnesses, COVID-19 is mediated through interferon responses [20]. In this context, we hypothesized that both IP-10 and TRAIL may be involved in COVID-19 pathogenesis and progression to severe disease.

Our results are in alignment with previous studies reporting that low TRAIL concentrations are associated with severe disease [21]. Nonetheless due to the high baseline severity of this cohort, the biomarker was nonspecific, and therefore, was not associated with progression to SRF or death compared to recovered patients [22]. In contrast, we and others have shown that higher IP-10 concentrations are measured in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia who progress to severe disease or death [23], [24]. Tegethoff et al, supported the notion that concentrations of IP-10 more than 3,000 pg/ml was an independent predictor of ICU mortality. In a study of 132 patients in Germany, baseline values of IP-10 were able to predict unfavorable disease evolution [20]. High and persistent levels of IP-10 indicate uncontrolled viral replication in many viral infections such as influenza, SARS, MERS and possibly COVID-19 [25], [26]. Although such an investigation was not within the scope of the current study, our results suggest that markers of uncontrolled viral replication including but not limited to IP-10, could also serve as predictive enrichment tools to guide anakinra or other immunomodulatory treatment. This probably implies that patients who benefit most from anakinra treatment are those with the highest degree of viral replication.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study so far evaluating IP-10 performance in patients with COVID-19. The performance of IP-10 was tested in a discovery and validation cohort, both enrolling prospectively recruited patients. IP-10 serum concentrations may stratify patients into two strata of risk of unfavorable outcome. Even in the validation cohort of our study, in which all patients had suPAR levels of 6 ng/ml or more indicating that a certain degree of immunological dysregulation was already in place, IP-10 still remained a strong predictor of unfavorable outcome. Anakinra treatment could significantly reduce this risk in both strata. Apart from suPAR, all other prognostic scores developed so far require measurement of a large number of biomarkers and a combination with clinical and radiological parameters [7], [27], [28], approach which is difficult to implement in clinical practice. After high vaccination rates, epidemiology might have changed and other comorbidities than those already described may increase the risk for unfavorable outcome. Combination of biomarkers or radiological tests may rise the cost; in this context measurement of a low cost, easy to perform sole biomarker such as IP-10, with good predictive performance, which can be measured rapidly in a point-of-care setting may be cost-effective, but this remains to be shown in future trials. The main limitation of this study is the retrospective analysis of anakinra treatment efficacy when IP-10 is 2,000 pg/ml. This is subject to selection bias. Definite answers on the role of IP-10 as a tool to select patients who receive most of benefit from anakinra treatment may come only from a future prospective study.

In conclusion, when suPAR measurements are not available to predict progression, IP-10 concentrations of 2000 pg/ml or higher may be conceived as an alternative to predict the risk of progression to SRF or death and possibly guide anakinra treatment in COVID-19.

Funding

The SAVE study was funded in part by a kind donation by Technomar shipping company, in part by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis (HISS) and in part by Sobi AB (publ). The SAVE-MORE trial was funded in part by the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis (HISS) and in part by Sobi AB (publ). Measurements of CRP, IP-10 and TRAIL for the needs of this manuscript were supported by MeMed Diagnostics, Tirat Carmel, Israel.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Charilaos Samaras: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Evdoxia Kyriazopoulou: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Visualization. Garyfallia Poulakou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Eran Reiner: Software, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Maria Kosmidou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Ioanna Karanika: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Vasileios Petrakis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. George Adamis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Nikolaos K. Gatselis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Archontoula Fragkou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Aggeliki Rapti: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Eleonora Taddei: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Ioannis Kalomenidis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. George Chrysos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Giulia Bertoli: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Ilias Kainis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Zoi Alexiou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Francesco Castelli: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Francesco Saverio Serino: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Petros Bakakos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Emanuele Nicastri: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Vassiliki Tzavara: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Evangelos Kostis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Lorenzo Dagna: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Sofia Koukidou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Glykeria Tzatzagou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Maria Chini: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Matteo Bassetti: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Christina Trakatelli: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. George Tsoukalas: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Carlo Selmi: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Michael Samarkos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Athina Pyrpasopoulou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Aikaterini Masgala: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Emmanouil Antonakis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Aikaterini Argyraki: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Karolina Akinosoglou: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Styliani Sympardi: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Periklis Panagopoulos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Haralampos Milionis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Simeon Metallidis: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Konstantinos N. Syrigos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Alon Angel: Software, Methodology, Resources, Writing – review & editing. George N. Dalekos: Investigation, Validation, Methodology, Resources, Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Mihai G. Netea: Conceptualization, Supervision. Evangelos J. Giamarellos-Bourboulis: Conceptualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper: [ER, AA are employees at MeMed Diagnostics. GB’s work was partly funded by the Italian Ministry of Health ‘Fondi Ricerca Corrente’ to IRCCS Sacro Cuore Don Calabria Hospital. GND has acted as advisor/lecturer for Ipsen, Pfizer, Genkyotex, Novartis and Sobi; received research grants from Abbvie and Gilead; PI in studies for Abbvie, Novartis, Gilead, Novo Nordisk, Genkyotex, Regulus Therapeutics Inc., Tiziana Life Sciences, Bayer, Astellas, Pfizer, Amyndas Pharmaceuticals, CymaBay Therapeutics Inc., Sobi and Intercept Pharmaceuticals. MGN was supported by an ERC Advanced grant (833247) and a Spinoza grant of the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. EJGB has received honoraria from Abbott CH, bioMérieux, Brahms GmbH, GSK, InflaRx GmbH, Sobi and XBiotech Inc; independent educational grants from Abbott CH, AbbVie, bioMérieux Inc, InflaRx GmbH, Johnson & Johnson, MSD, Novartis, Sobi, UCB and XBiotech Inc.; and funding from the Horizon2020 Marie-Curie Project European Sepsis Academy (granted to the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens), the Horizon 2020 European Grants ImmunoSep and RISKinCOVID (granted to the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis) and from the Horizon Europe project EPIC-CROWN-2 (granted to the Hellenic Institute for the Study of Sepsis). The other authors do not have any competing interest to declare.].

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

None.

Access to data

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cyto.2022.156111.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

- 1.World health Organization (2022). WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) Dashboard. https://covid19.who.int/.

- 2.Karakike E., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Kyprianou M., Fleischmann-Struzek C., Pletz M.W., Netea M.G., et al. Coronavirus Disease 2019 as cause of viral sepsis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit. Care Med. 2021;49:2042–2057. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000005195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rovina N., Akinosoglou K., Eugen-Olsen J., Hayek S., Reiser J., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J. Soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) as an early predictor of severe respiratory failure in patients with COVID-19 pneumonia. Crit. Care. 2021;24:187. doi: 10.1186/s13054-020-02897-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kyriazopoulou E., Panagopoulos P., Metallidis S., Dalekos G.N., Poulakou G., Gatselis N., Karakike E., Saridaki M., Loli G., Stefos A., Prasianaki D., Georgiadou S., Tsachouridou O., Petrakis V., Tsiakos K., Kosmidou M., Lygoura V., Dareioti M., Milionis H., Papanikolaou I.C., Akinosoglou K., Myrodia D.-M., Gravvani A., Stamou A., Gkavogianni T., Katrini K., Marantos T., Trontzas I.P., Syrigos K., Chatzis L., Chatzis S., Vechlidis N., Avgoustou C., Chalvatzis S., Kyprianou M., van der Meer J.WM., Eugen-Olsen J., Netea M.G., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J. An open label trial of anakinra to prevent respiratory failure in COVID-19. Elife. 2021;10:e66125. doi: 10.7554/eLife.66125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kyriazopoulou E., Poulakou G., Milionis H., Metallidis S., Adamis G., Tsiakos K., Fragkou A., Rapti A., Damoulari C., Fantoni M., Kalomenidis I., Chrysos G., Angheben A., Kainis I., Alexiou Z., Castelli F., Serino F.S., Tsilika M., Bakakos P., Nicastri E., Tzavara V., Kostis E., Dagna L., Koufargyris P., Dimakou K., Savvanis S., Tzatzagou G., Chini M., Cavalli G., Bassetti M., Katrini K., Kotsis V., Tsoukalas G., Selmi C., Bliziotis I., Samarkos M., Doumas M., Ktena S., Masgala A., Papanikolaou I., Kosmidou M., Myrodia D.-M., Argyraki A., Cardellino C.S., Koliakou K., Katsigianni E.-I., Rapti V., Giannitsioti E., Cingolani A., Micha S., Akinosoglou K., Liatsis-Douvitsas O., Symbardi S., Gatselis N., Mouktaroudi M., Ippolito G., Florou E., Kotsaki A., Netea M.G., Eugen-Olsen J., Kyprianou M., Panagopoulos P., Dalekos G.N., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J. Early treatment of COVID-19 with anakinra guided by soluble urokinase plasminogen receptor plasma levels: a double-blind, randomized controlled phase 3 trial. Nat. Med. 2021;27(10):1752–1760. doi: 10.1038/s41591-021-01499-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.European Medicines Agency (2021). EMA recommends approval for use of Kineret in adults with COVID-19. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/news/ema-recommends-approval-use-kineret-adults-covid-19.

- 7.Fact sheet for healthcare providers: emergency use authorization for kineret https://www.fda.gov/media/163075/download.

- 8.Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Poulakou G., de Nooijer A., Milionis H., Metallidis S., Ploumidis M., Grigoropoulou P., Rapti A., Segala F.V., Balis E., Giannitsioti E., Rodari P., Kainis I., Alexiou Z., Focà E., Lucio B., Rovina N., Scorzolini L., Dafni M., Ioannou S., Tomelleri A., Dimakou K., Tzatzagou G., Chini M., Bassetti M., Trakatelli C., Tsoukalas G., Selmi C., Samaras C., Saridaki M., Pyrpasopoulou A., Kaldara E., Papanikolaou I., Argyraki A., Akinosoglou K., Koupetori M., Panagopoulos P., Dalekos G.N., Netea M.G. Development and validation of SCOPE score: A clinical score to predict COVID-19 pneumonia progression to severe respiratory failure. Cell Rep. Med. 2022;3(3):100560. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2022.100560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gatselis N.K., Lygoura V., Lyberopoulou A., Giannoulis G., Samakidou A., Vaiou A., Vatidis G., Antoniou K., Stefos A., Georgiadou S., Sagris D., Sveroni D., Stergioula D., Gabeta S., Ntaios G., Dalekos G.N. Soluble IL-2R Levels at baseline predict the development of severe respiratory failure and mortality in COVID-19 patients. Viruses. 2022;14(4):787. doi: 10.3390/v14040787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kassianidis G., Siampanos A., Poulakou G., Adamis G., Rapti A., Milionis H., Dalekos G.N., Petrakis V., Sympardi S., Metallidis S., Alexiou Z., Gkavogianni T., Giamarellos-Bourboulis E.J., Theoharides T.C. Calprotectin and imbalances between acute-phase mediators are associated with critical illness in COVID-19. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022;23(9):4894. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.M, Hainrichson, N, Avni, E, Eden, P, Feigin, A, Gelman, S, Halabi et al. A point-of-need platform for rapid measurement of a host-protein score that differentiates bacterial from viral infection: Analytical evaluation. Clin Biochem 2022: S0009-9120(22)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.van der Does Y., Rood P.P.M., Ramakers C., Schuit S.C.E., Patka P., van Gorp E.C.M., et al. Identifying patients with bacterial infections using a combination of C-reactive protein, procalcitonin, TRAIL, and IP-10 in the emergency department: a prospective observational cohort study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2018;24:1297–1304. doi: 10.1016/j.cmi.2018.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ashkenazi-Hoffnung L., Oved K., Navon R., Friedman T., Boico O., Paz M., et al. A host-protein signature is superior to other biomarkers for differentiating between bacterial and viral disease in patients with respiratory infection and fever without source: a prospective observational study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2018;37:1361–1371. doi: 10.1007/s10096-018-3261-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kesmez Can F., Özkurt Z., Öztürk N., Sezen S. Effect of IL-6, IL-8/CXCL8, IP-10/CXCL 10 levels on the severity in COVID 19 infection. Int. J. Clin. Pract. 2021;75:e14970. doi: 10.1111/ijcp.14970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haroun R.A., Osman W.H., Eessa A.M. Interferon-γ-induced protein 10 (IP-10) and serum amyloid A (SAA) are excellent biomarkers for the prediction of COVID-19 progression and severity. Life Sci. 2021;269 doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang Y., Shen C., Li J., Yuan J., Wei J., Huang F., et al. Plasma IP-10 and MCP-3 levels are highly associated with disease severity and predict the progression of COVID-19. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2020;146:119–127.e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.04.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley J.A., McNeil B.J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983;148:839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dufour J.H., Dziejman M., Liu M.T., Leung J.H., Lane T.E., Luster A.D. IFN-gamma-inducible protein 10 (IP-10; CXCL10)-deficient mice reveal a role for IP-10 in effector T cell generation and trafficking. J. Immunol. 2002;168:3195–3204. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.7.3195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thorburn A. Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) pathway signaling. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2007;2:461–465. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31805fea64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.van der Wijst M.G.P., Vazquez S.E., Hartoularos G.C., Bastard P., Grant T., Bueno R., et al. Type I interferon autoantibodies are associated with systemic immune alterations in patients with COVID-19. Sci. Transl. Med. 2021;13:eabh2624. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.abh2624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tegethoff S.A., Danziger G., Kühn D., Kimmer C., Adams T., Heintz L., et al. TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand, interferon gamma-induced protein 10, and C-reactive protein in predicting the progression of SARS-CoV-2 infection: a prospective cohort study. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2022;122:178–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2022.05.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schenck E.J., Ma K.C., Price D.R., Nicholson T., Oromendia C., Gantzler E.R., et al. Circulating cell death biomarker TRAIL is associated with increased organ dysfunction in sepsis. JCI Insight. 2019;4:e127143. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.127143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lev S., Gottesman T., Sahaf Levin G., Lederfein D., Berkov E., Diker D., et al. Observational cohort study of IP-10's potential as a biomarker to aid in inflammation regulation within a clinical decision support protocol for patients with severe COVID-19. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245296. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe H.S., Ling L.M., Elangovan E., Vasoo S., Abdad M.Y., Thong B.Y.H., et al. Plasma IP-10 could identify early lung disease in severe COVID-19 patients. Ann. Acad. Med. Singap. 2021;50:856–858. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chan R.W., Leung C.Y., Nicholls J.M., Peiris J.S., Chan M.C. Proinflammatory cytokine response and viral replication in mouse bone marrow derived macrophages infected with influenza H1N1 and H5N1 viruses. PLoS One. 2012;7:e51057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhou J., Chu H., Li C., Wong B.H., Cheng Z.S., Poon V.K., et al. Active replication of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and aberrant induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in human macrophages: implications for pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014;209:1331–1342. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liang W., Liang H., Ou L., Chen B., Chen A., Li C., et al. Development and validation of a clinical risk score to predict the occurrence of critical illness in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1081–1089. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wynants L., Van Calster B., Collins G.S., Riley R.D., Heinze G., Schuit E., et al. Prediction models for diagnosis and prognosis of Covid-19: systematic review and critical appraisal. BMJ. 2021;369 doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.