Abstract

Many coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-recovered patients report signs and symptoms and are experiencing neurological, psychiatric, and cognitive problems. However, the exact prevalence and outcome of cognitive sequelae is unclear. Even though the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 has target brain cells through binding to angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor in acute infection, several studies indicate the absence of the virus in the brain of many COVID-19 patients who developed neurological disorders. Thus, the COVID-19 mechanisms for stimulating cognitive dysfunction may include neuroinflammation, which is mediated by a sustained systemic inflammation, a disrupted brain barrier, and severe glial reactiveness, especially within the limbic system. This review explores the interplay of infected lungs and brain in COVID-19 and its impact on the cognitive function.

Key Words: COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Neuroinflammation, Cognitive dysfunction

Introduction

In December 2019, the world began to face a pandemic caused by the new coronavirus, discovered in the city of Wuhan, China [1, 2], called severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), being the etiologic agent of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) [2]. Since its discovery, the virus has had a rapid evolution reaching almost all countries in the world [3]. In March 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the SARS-CoV-2 virus as a pandemic [2, 4, 5].

Currently, COVID-19 represents a major challenge to public health and economy, as the host's immune response is not completely understood [6]. SARS-CoV-2 infection can also affect the CNS. The number of patients with respiratory infection and neurological damage is increasing [7, 8]. Thus, there is a great need for understanding the immune responses to this virus and how it can compromise the brain [9].

During an innate immune response to a viral infection, pattern recognition receptors, such as Toll-like receptors (TLR) and NOD-like receptors, recognize different molecular structures that are characteristic of the invading virus [10, 11]. These molecular structures are known as pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The interaction between PAMPs and pattern recognition receptors triggers the onset of the inflammatory response against the invading virus leading to a signal transduction that involves the activation of the nuclear factor kappa B (NF-kB) [12, 13]. As a consequence, pro-inflammatory mediators are produced like tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin-1β, and interleukin-6 (IL-6), which favor an intense cellular response with the release of secondary mediators [14, 15, 16]. This results in the influx of several immune cells, such as macrophages, neutrophils, and T cells from the circulation to the site of infection [10].

Therefore, when the attempt to limit the infection is augmented and sustained, nonspecific oxidative and inflammatory effects will result in cellular damage [10]. SARS-CoV-2 infection leads to low levels of oxygen saturation, being one of the main causes of mortality; although these mechanisms are not fully understood, the excessive synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines is considered one of the main contributing factors [17, 18], and a study points the association of a cytokine profile with the severity of COVID-19 disease [19]. Fatality predictors from a recent retrospective multicenter study of 150 confirmed COVID-19 cases in Wuhan, China, included elevated ferritin [20], suggesting that the mortality may be due to hyperinflammation [21].

Patients with severe disease are more likely to develop neurological symptoms, including loss of taste and smell, as well as encephalitis and cerebrovascular disorders [22]. However, whether neurological complications are actually due to direct viral infection of the nervous system or arise as a result of the immune reaction against the virus in patients who had preexisting deficits or had a certain harmful immune response is still a question to be properly addressed [22]. Thus, this review aimed to provide an overview of the current neurological symptoms associated with COVID-19 as well as to present a perspective between infected lungs and the brain in COVID-19, including the impact on cognitive function.

Neurological Manifestations after COVID-19 Infection

The potential of SARS-CoV-2 in causing neuroinflammatory and neurodegenerative manifestations in short- and long term have become a target of great interest in scientific research [23, 24, 25]. Given that neurological dysfunction due to inflammation increases the burden of cognitive impairment [25, 26, 27] and the mortality rate [28], our search strategy focused on listing studies concerning the manifestations of cognitive impairment in COVID-19 patients, and the articles are shown in the Table 1.

Table 1.

Cognitive impairment manifestation of COVID-19 patients

| Study type | Location | n | Manifestation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retrospective cohort | France | 58 | Dysexecutive syndrome: 14/39 (36%) Agitation: 40/58 (69%) Confusiona: 26/40 (65%) |

[35] |

|

| ||||

| Case-control | India | 93 COVID-19 versus 102 controls | COVID-19 patients presented lower scores in the domainsb of visuoperception (2.4±0.7 vs. 2.8±0.7); naming (3.6±0.5 vs. 3.9±0.2); fluency (0.9±0.6 vs. 1.6±0.7). Correlated with age | [34] |

|

| ||||

| Case-control | China | 29 COVID-19 versus 29 controls | COVID-19 patients exhibited deficits in attention domainc | [125] |

|

| ||||

| Cross-sectional | USA | 57 | Cognitive deficitsd varied in severity: mild (27; 47%), moderate (14; 25%), severe (5; 9%); delirium during acute hospitalization (37; 66%) | [30] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Italy | 87 | Patients divided into four groups according to the respiratory assistance. MoCAb/MMSEe: group 1: 74.2% deficits/12.9% mild to severe deficit; group 2: 94.4% deficits/55.6% mild to moderate deficits; group 3: 89.6% deficits/48.3% mild to severe deficits; group 4: 77.8% deficits/44.4% moderate deficits. Correlated with age | [29] |

|

| ||||

| Case series | Italy | 9 | Low scorese in the domains of attention, calculation, short-term memory, constructional praxia, and written language (3; 33.3%) | [126] |

|

| ||||

| Case-control | Italy | 12 COVID-19 versus 12 controls | COVID-19 patients showed a significantly poorer cognitive performanceb and smaller scores in different tests (p < 0.001) | [127] |

|

| ||||

| Retrospective and prospective cohort | Italy | 185 | Evaluations performed at 23 [20–29] days post discharge. Cognitive impaired patientsb: 47 (25.4%). Of these: required hospitalization: 36; were discharged from emergency department: 11 | [128] |

|

| ||||

| Retrospective cohort | USA | 1,409 | Cognitive dysfunctiong in different domains: requires prompting (327; 23%), requires assistance, and direction (92; 7%). Confusion: in new and complex situations only (575; 41%), on awakening or at night, during the day/evening, or constantly (85; 6%) | [37] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Germany | 29 | Cognitive impairmentb in executive abilities, visuoconstruction, memory, and attention: 29 patients. Severity: mild to moderate (14; 54%); severe (4; 15%). Alterations in different domainsh: memory (7/14); executive functions (6/15) | [129] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective case series | Germany | 8 | Subacute stage: 37±19 days post COVID-19 onset; chronic stages: 6 months post COVID-19 onset. Global cognitive functionb improved over time (from subacute to chronic stages), but the mean score was still indicative of cognitive impairment. Persistent deficits cognitive: 5 patients (visuoconstruction, executive functions, memory) | [130] |

|

| ||||

| Cross-sectional | Italy | 56 | Patients with delirium (14; 25%): higher scores in different testsa,i (p < 0.001) and were older than patients without delirium (p = 0.002) | [36] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Denmark | 29 COVID-19 versus 100 controls | Global cognitive impairments (11; 38%) or selective impairment (7; 24%). Deficits in domains of verbal learning and working memoryj,k | [33] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | UK | 58 COVID-19 versus 30 controls | Global cognitive impairmentb (16; 28%) and deficits in the domain of executive/visuospatial (40% vs. 16% in controls) | [31] |

|

| ||||

| Case report | USA | 1 | Delirium during acute phase of infection. Delirium and cognitive status did not improve at more than 3 months after diagnosing | [38] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Italy | 266 (130 had cognitive assessment) | Poor performance in different functions of a cognitive testl: at least one function (21; 16%), two (22; 17%), three (18; 14%), four (14; 11%), five (7; 5%), and 2 patients (1.5%) showed no good performance at all. Patients with psychopathology at 1-month after discharge performed worse on verbal fluency, information processing, and executive functions at the 3 months assessment, whereas psychopathology at 3 months associated with worse information processing | [131] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Germany | 53 (13 had cognitive assessment) | Cognitive deficitsb in executive function, attention, language, and delayed recall (8; 61.5%) | [132] |

|

| ||||

| Case-control | Italy | 12 COVID-19 versus 10 controls | Evaluations performed at 9–13 weeks post COVID-19. Diminished executive functions (dysexecutive syndrome)f | [32] |

|

| ||||

| Randomized clinical trial | Germany | 1,030 (1,026 had cognitive assessment) | Cognitive impairmentb: 622 (60.6%) | [133] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | USA | 50 COVID-19 versus 50 controls | Cognitive deficitsm in short-term memory (15; 30%) and attention (12; 24%) | [134] |

|

| ||||

| Prospective cohort | Austria | 23 (14 had cognitive assessment) | Cognitive deficitsn in concentration, memory, and/or executive functions (4; 29%) | [135] |

The Confusion Assessment Method for the ICU [intensive care unit] (CAM-ICU).

Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) test.

Continuous Performance Test (CPT).

Brief Memory and Executive Test (BMET).

Mini Mental State Evaluation (MMSE).

Frontal Assessment Battery (FAB).

Outcome and Assessment Information Set version D-1 (OASIS D-1).

Neuropsychological Test Battery (NTB).

The 4 ‘A's Test (4AT).

Psychiatry Danish Version (SCIP-D).

Trail Making Test-Part B (TMT-B).

Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia (BACS).

NIH Toolbox for the Assessment of Neurological and Behavioral Function.

Tests of Attentional Performance (TAP).

Studies suggest that patients infected by SARS-CoV-2 may present neurological damage and impaired cognitive functions during different phases of recovery. Alemanno et al. [29] evaluated 87 patients at 5–20 days after COVID-19 symptoms onset, and they detected cognitive dysfunctions that included deficits in memory, executive functions, language, orientation, and abstraction; also, patients who received invasive ventilation and sedation presented better cognitive functions, especially the younger individuals.

Jaywant et al. [30] analyzed 57 individuals undergoing inpatient rehabilitation after hospitalization for 43.2 days (±19.2) due to COVID-19. They observed that 81% presented some cognitive deficits (47% had mild impairment while 25% showed moderate impairment), and the main alterations were seeing in the domains of attention and executive functions, e.g., rapid visual attention, immediate recall, and information processing speed.

The medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on cognition were assessed by Raman et al. [31]. The evaluations performed at 2–3 months post COVID-19 in 58 patients and 30 healthy controls indicated that 28% of the patients presented global cognitive impairment, but the most pronounced deficit was found in the domain of executive/visuospatial. Diminished executive functions (dysexecutive syndrome) were also found by Versace et al. [32] in 12 patients at 9–13 weeks post COVID-19 onset.

Similar results were demonstrated by Miskowiak et al. [33] at 3–4 months after disease onset, denoting global cognitive impairment in 38% of the COVID-19-positive individuals (n = 29), while 24% of the patients presented selective impairment, and the main deficits were found in the domains of verbal learning and working memory. Blazhenets et al. [34] evaluated eight COVID-19 patients at the subacute stage of the disease (37 ± 19 days) and at approximately 6 months post disease onset, demonstrating that although there was an improvement in global cognitive function, 5 patients remained below the cut-off value for detection of cognitive impairment.

These cognitive impairments are not limited to symptomatic patients, as found by Amalakanti et al. [35] in a case-control study involving 93 COVID-19 patients and 102 controls, showing that asymptomatic individuals presented an impaired function in the visuoperception, naming, and fluency domains of cognition, and the impairment was worse in older participants.

Confusion and delirium were also observed in several COVID-19 patients. Helms et al. [36] found that 26 of 40 participants (65%) presented confusion during the course of the disease and hospitalization in the ICU. D'Ardes et al. [37] noted that 14 patients (25%) presented delirium and had test results indicative of cognitive impairment. In addition, Bowles et al. [38] demonstrated that in their retrospective cohort confusion was observed in different domains, e.g., in new and complex situations only (575; 41%), and on awakening or at night, during the day/evening, or constantly (85; 6%); cognitive impairments were also detected. In a case report, Payne et al. [39] pointed a case of an 85-year-old patient who experienced confusion and functional decline in the acute phase of the disease, but after more than 3 months from diagnose, the cognitive status and delirium did not return to the baseline.

Cross Talk between Infected Lungs and the Brain in COVID-19

Lung Infection by SARS-CoV-2

A summary of a report of over 70,000 cases of SARS-CoV-2 infection pointed that most cases (81%) were classified as mild (without pneumonia or mild pneumonia), whereas 14% of the cases were considered severe: presence of dyspnea, respiratory frequency ≥30/min, blood oxygen saturation ≤93%, partial pressure of arterial oxygen to a fraction of inspired oxygen ratio <300, and lung infiltrates >50% within 24–48 h, and 5% were critical (with respiratory failure, septic shock, and multiple organ dysfunction or failure). The overall case fatality rate was 2.3%; however, patients with comorbidities or those over 70 years old were more susceptible to complications and death [40].

The airborne and persistence of the virus on surfaces explain the rapid spread of COVID-19 infection [41]. The acute clinical features of COVID-19 are fever, cough, myalgia, headache, and sore throat. The following clinical stage was characterized by high fever, shortness of breath, hypoxemia, and atypical pneumonia [42].

SARS-CoV-2 spreads through droplets and secretions from the respiratory tract of an infected person [43]. The SARS-CoV-2 is an enveloped positive-stranded RNA virus. This virus replicates in the cytoplasm of host cells and the viral RNA genome merges with the plasma membrane, releasing viral replicates into the extracellular space [44].

It was recently predicted that SARS-CoV-2 directly attacks type 2 pneumocytes by binding to the human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) receptor [45], a membrane carboxypeptidase enzyme present in distal airways and alveoli, especially type 2 pneumocytes which have the highest expression of ACE2, along with alveolar macrophages and dendritic cells. For this reason, the surface area of the lung serves as a reservoir for viral binding and replication [46]. ACE2 is also expressed on the vascular endothelium, nasal, oral, nasopharyngeal, and oropharyngeal epithelia, gut epithelia, cardiac pericytes, renal proximal tubular cells and in the skin, reticuloendothelial, and the CNS [47].

Dendritic cells and alveolar macrophages phagocytose the virus-infected epithelial cells and induce alveolar injury and interstitial inflammation [48]. In addition, recruited macrophages release chemokines, increasing capillary permeability, and allowing neutrophils to migrate into the space alveolar. The migration of neutrophils results in the rupture of the alveolar-capillary barrier and the formation of edema due to the migration of blood proteins [49]. In the alveolar space, monocytes are recruited and secrete pro-inflammatory cytokines that induce pneumocyte apoptosis [44]. Also, interstitial edema contributes to alveolar dysfunction [50] and severe impairment of alveolar gas exchange and oxygenation [51]. The massive production of cytokines is involved in this process and is called “cytokine storm.” Cytokine storm results from an inflammatory overreaction that ultimately leads to endothelial cell dysfunction, damage of the vascular barrier, capillary leak, and diffuse alveolar damage [10].

Cytokine Storm after SARS-CoV-2 Infection

Cytokine storm is an umbrella term encompassing several disorders of immune dysregulation characterized by constitutional symptoms, systemic inflammation, and multiorgan dysfunction that can lead to multiorgan failure if inadequately treated [52]. The mortality of hospitalized individuals with pneumonia due to COVID-19 has been attributed mainly to the cytokine storm syndrome [10].

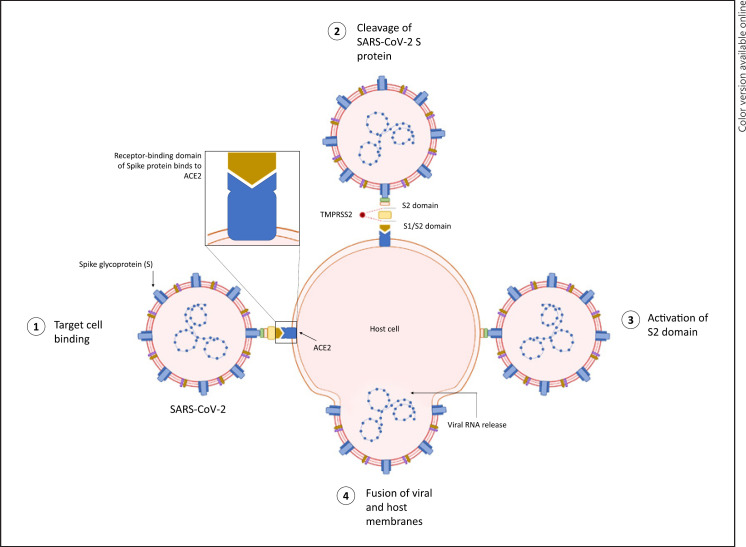

The spike surface glycoprotein S on the SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2, and cell entry requires priming of the spike protein by the cellular serine protease TMPRSS2 or other proteases. The alveolar epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and vascular endothelial cells are the primary targets of the virions (Fig. 1). The virus inhibits the production of interferons that are part of cellular defense mechanisms. The viral replication releases a large number of virions, leading to infection of neighboring target cells and viremia, which then cause an exaggerated pulmonary and systemic inflammatory response, respectively [53, 54]. This explains the clinical presentation of severe COVID-19 that is predominated by acute respiratory distress syndrome, shock, and coagulopathy [53].

Fig. 1.

Schematic of the SARS-CoV-2 infection. (1) The S protein binds to the receptor ACE2. (2) Cleavage of SARS-COV-2 S protein. (3) Activation of S2 domain. (4) The virus-cell fusion process.

Renin cleaves angiotensinogen to produce angiotensin I, which is further cleaved by ACE to produce angiotensin II, having a dual role. By acting through angiotensin II type 1 receptor, it facilitates vasoconstriction, fibrotic remodeling, and inflammation, whereas through angiotensin II type 2 receptor, it leads to vasodilation and growth inhibition. Angiotensin II is cleaved by ACE2 to Ang 1–7, which counteracts the harmful effects of the ACE/Ang II/AT1 axis. Thus, ACE2 primarily plays a key role to physiologically counterbalance ACE and regulate angiotensin II. The internalization of ACE2 after viral interaction leads to its downregulation and consequent upregulation of angiotensin II. The latter, by acting through angiotensin II type 1 receptor, activates the downstream inflammatory pathways, leading to the cytokine storm that adversely affects multiple organs [55].

Specifically, cytokine storm evolves through several pathways, like the NF-κB, janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription (JAK/STAT), and the macrophage activation pathway, triggering the release of interleukin-1β, IL-6, C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 10 (CXCL10), TNF-α, interferon-γ (IFN-γ), macrophage inflammatory protein-1α and -1β, and the vascular endothelial cell growth factor [56]. IL-6 is a key player in the cytokine storm, stimulating several cell types and forming a positive feedback loop [19, 57], and higher IL-6 levels are strongly associated with shorter survival [58]. The large-scale unregulated production of interleukins, particularly IL-6, further stimulates several downstream pathways, increasing the production of acute-phase reactants, like C-reactive protein [59].

Hematological alterations are also related with the cytokine storm. Peripheral blood leukocyte and lymphocyte counts are normal or slightly reduced in early disease, when symptoms tend to be nonspecific [60]. Approximately 7–14 days from the onset of symptoms, the appearance of significant lymphopenia coincides with a decline in clinical status, enhanced levels of inflammatory mediators, and cytokine storm [61].

TNF-α can promote T-cell apoptosis and IL-6 may suppress normal T-cell activation [62]. Additionally, reduced lymphocyte turnover due to the cytokine storm induces atrophy of lymphoid organs. Thus, the SARS-CoV-2 infection may cause lymphopenia resulting in reduced CD4+, CD8+ T-cell counts, and suppressed IFN-γ production [63]. Type 1 IFNs are important in inhibiting the early stage of COVID-19 infection, so a failure in the immune response of type 1 IFNs excessively enhances the activity of the immune system, increasing pro-inflammatory cytokine production [64]. In the CNS, the expression of ACE2 in neurons and glial cells makes the brain vulnerable to COVID-19 infection [65], but the peripheral cytokine storm can be an important factor to the brain alterations.

Brain Barriers and SARS-CoV-2 Infection

The CNS has long been described as immunologically privileged due to its natural barriers that separate it from peripheral organs, but this dogma has undergone modifications [66]. Macroscopic examples are the brain meninges [67], but there are also microscopic brain barriers formed by different cells that assist in controlling the influx of substances from the blood into the brain parenchyma [68]. The blood-brain barrier (BBB) and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier form these brain barriers [69]. The BBB is located at the level of the endothelial cells within CNS microvessels, while the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barrier is established by the choroid plexus epithelial cells [70].

The cells that compose brain barriers can be stimulated by microorganisms, such as bacteria, or by PAMPs, e.g., gram-negative lipopolysaccharide [71], and by immune or toxic molecules present in peripheral blood, such as interleukins [72] or reactive oxygen species [73]. However, viruses can also activate brain barrier cells [74], as emerging data indicate that neurological complications occur as a consequence of SARS-CoV-2 infection [75] and it could be caused by BBB activation [76]. The activation of endothelial cells from the BBB occurs due to the high expression of ACE2 receptors [77], but it is also known that BBB cells can be infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus, and after viral replication, virions can be released into the brain parenchyma [78].

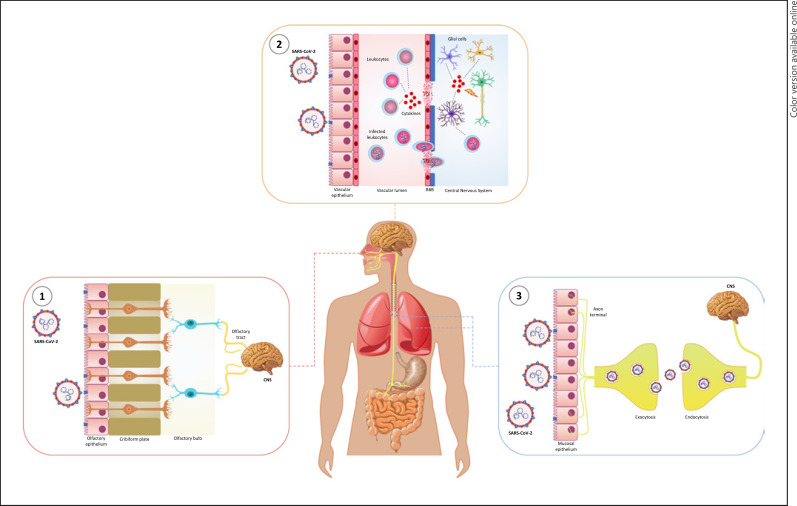

Recent studies show different routes of entry for the COVID-19 virus into the CNS [79, 80] (Fig. 2). The first route of entry would be through the olfactory epithelium, crossing the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and reaching the olfactory bulb from which it could spread to different areas of the brain [81]. The second route would be through the activation of brain barriers, as already mentioned, which allows the action of a third route. In this third route, infected leukocytes could enter through dysfunctional brain barriers, acting as a vehicle for dissemination within the CNS [82, 83]. And the fourth mechanism would be through the neuronal pathway, in the lower respiratory tract through the vagus nerve, where viruses are transported by endocytosis and exocytosis through neuronal cell bodies [84]. Evidently, viruses can also damage neurons directly or indirectly by stimulating the reaction of microglial cells and astrocytes [85].

Fig. 2.

Routes of entry for the COVID-19 virus in the CNS. (1) The first route of entry would be through the olfactory epithelium, crossing the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone and reaching the olfactory bulb from which it could spread to different areas of the brain. (2) The second route would be through the activation and permeability of BBB. The virus in the bloodstream may infect the peripheral immune cells and cause the cytokine storm. Cytokines can signal and alter the structure of BBB, and infected leukocytes could enter the CNS through dysfunctional brain barriers, acting as a vehicle for dissemination within the CNS or aggravate cytokine production within the CNS. (3) Another mechanism would be through the neuronal pathway in the lower respiratory tract through thevagus nerve, where viruses are transported by endocytosis and exocytosis through neuronal cell bodies.

However, we intend to show the neuronal damage due to neuroinflammation occurring as a response to peripheral inflammation, independently of brain infection with SARS-CoV-2. A previous study identified that COVID-19 patients presented enhanced levels of inflammatory markers in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid, being the encephalopathy the neurological condition mainly influenced by peripheral inflammation[86]. The SARS-CoV-2 infection can be classified as acute, that is, there is no persistence of the virus in the human body for long periods, indicating that only a section of the neurological changes seen in COVID-19 patients is caused directly by the presence of the virus [87, 88]. In fact, postmortem studies show that a significant rate of individuals diagnosed with COVID-19 who presented neurological disorders tested negative for the presence of the virus in the CNS [89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94].

For a long time, many peripheral infectious diseases were not associated to the changes in the CNS [68], but this concept is rapidly changing due to the COVID-19 pandemic, where many surviving patients show cognitive and functional changes [89]. We support the idea that the cytokine storm may be intrinsically involved in early and long-term neurological damage, during SARS-CoV-2 infection and after COVID-19 recovery [95, 96]. In addition, the activation of brain barriers is possibly the most accurate mechanism for enhancing neurological damage in COVID-19 individuals [75, 97] since in response to stressful events, such as infections or release of inflammatory mediators, the characteristics of these barriers can be altered, leading to edema and recruitment of inflammatory cells and the release of toxics metabolites into the brain parenchyma [70].

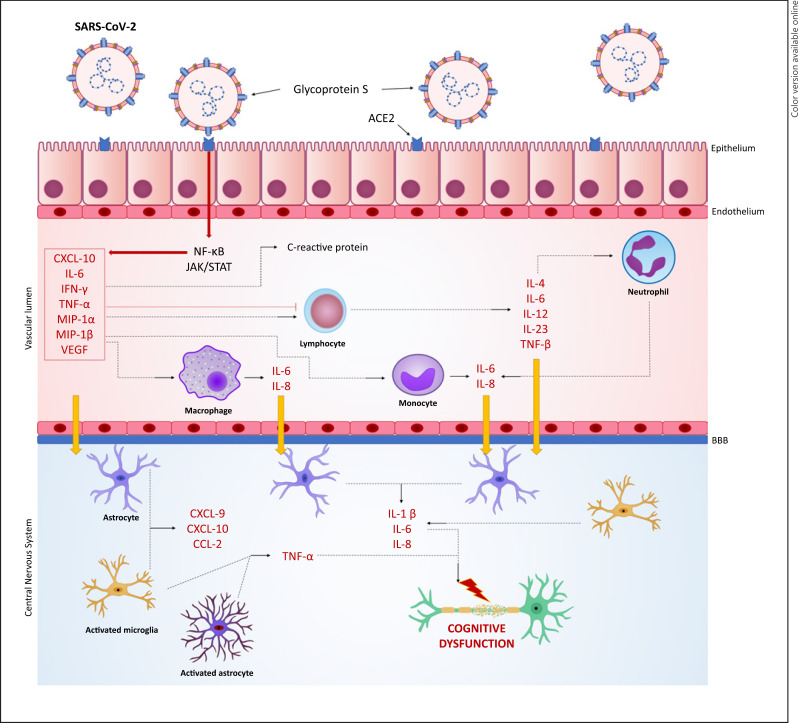

Abdominal sepsis is an example that illustrates what is been proposed to happen in COVID-19: peripheral pro-inflammatory cytokines, along with oxidative stress, stimulate the expression of extracellular matrix metalloproteinases that degrade the tight junctions of the BBB and impair its functioning [98, 99]. Increased expression of the type 1 adhesion molecule, responsible for the scrolling and infiltration of leukocytes in the cerebral microvasculature, was verified in experimental sepsis [100]. In addition, an increasing permeability of BBB can lead to the activation of glial cells and the production of cytotoxic mediators which in turn act on the brain barriers, propagating the damage. Thus, brain barriers permeability is not only a cause but a consequence of brain injury in sepsis [68]. In summary, neurological damage can arise regardless of the presence of the virus, considering that peripheral mediators can access glial cells and induce their reactiveness, and these in turn initiate and maintain neuroinflammation, which in excess causes more cellular damage (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

SARS-CoV-2-mediated cognitive impairment. After entry into the epithelial cells, the virus activates NF-κB and JAK/STAT pathway by TLR binding and leads to the production of TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IFN-γ, CXCL10, MIP-1α and -1β, and VEGF. The cytokines stimulate the production of C-reactive protein and promote T-cell apoptosis, suppress T-cell activation, and IFN-γ production. The cytokines and chemokines attract immune cells from the circulation, like the monocytes, macrophages, T cells, and neutrophils, to the site of infection. Additionally, TNF-α, IL-4, IL-6, IL-12, and IL-23 further recruit the immune cells, establishing a pro-inflammatory feedback loop that leads to BBB permeability and stimulates microglia and astrocyte responsiveness. Consequently, these cells produce more inflammatory mediators that exert neurotoxic effects, promoting neuronal dysfunction and cognitive impairment.

Glial Involvement in Neurodegeneration Caused by COVID-19

Microglia and astrocytes constitute two important glial cells. Microglia are the CNS-resident immune cells, responsible for the immune surveillance of CNS, regulation of neuronal activity, synaptic maintenance, and plasticity [101]. Microglia are dynamic cells that continuously promote self-remodeling and can attack stressed neurons [102]. Along with microglia, the astrocytes are involved in physiological and pathological activities within the CNS [103]. These activities include not only the formation and maturation of synapses [104] but also the maintenance, pruning and remodeling of synaptic transmission, and plasticity [105]. Astrocytes are capable of releasing several neurotrophic factors that assist in neuron differentiation and survival [106].

Microglia and astrocytes become reactive to inflammatory processes mainly because of vascular alterations in the brain that may lead to hypoxia and cytokine storm, and these alterations can arise from a direct CNS viral infection or a systemic inflammation due to a peripheral organ dysfunction (Fig. 3) [7]. As seen in sepsis [107], COVID-19 patients can experience cognitive impairment, since the systemic inflammation and the acute respiratory distress syndrome together produce a wide range of insults that favors glial cells activation, BBB disruption, and neurodegeneration, being the hippocampus highly susceptible [108].

In the brain, ACE2 receptors are present on neurons and glial cells [109], but it has been also discovered in substantia nigra, ventricles, middle temporal gyrus, the posterior cingulate cortex, and the olfactory bulb. Such widespread expression in the brain has reinforced that SARS-CoV-2 can infect neurons and glial cells in the CNS [109, 110].

A case report of a SARS-CoV-2 patient with cerebellar hemorrhage showed microglial nodules and neuronophagia bilaterally and in the cerebellar dentate nuclei, as highlighted by CD68 immunostains, and also CD8+ cells in microglial nodules [111]. COVID-19 infection induces severe hypoxia conditions, which potentiate and exacerbate microglia responsiveness and delays its shift to a surveillant state important for tissue repair. This is a possible pathway for the pathogenicity of COVID-19 and the complications in tissues sensible of oxygenation variation, such as the brain, and tissue damage as observed in severe patients of COVID-19 [112].

Moreover, pathogens are able to directly induce astrocytes to become reactive, such as herpes simplex virus type 2 [113], Japanese encephalitis virus [74], and more recently, SARS-CoV-2 [89], since astrocytes express ACE2 receptors, though in a lower concentration than in neurons [114]. In August 2020, the first preclinical evidence emerged indicating that coronaviruses can stimulate the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines in type I astrocytes. Evidences of astrocyte activation have been identified in the plasma, brain, and cerebrospinal fluid of patients with COVID-19 [115, 116, 117].

Another important evidence emerged when a postmortem study found similar histopathological alterations among COVID-19 patients and sepsis patients [118], supporting the hypothesis that not only the presence of the virus [119] but also the cytokine storm contributes to neurological damage after COVID-19, in the same way that occurs during sepsis [68]: peripheral COVID-19 infection induces an expressive release of cytokines, which can subsequently compromise the BBB and cause the reactiveness of microglia- and astrocyte-borne TLR, stimulating these cells to release toxic substances and inflammatory mediators, thus leading to neuronal tissue damage without the presence of the virus in situ [77]. In fact, some works show that most of the patients with neurological alterations due to COVID-19 did not present the virus in the CNS [89, 118, 120, 121].

Independently of the reason, COVID-19 survivors are at a high risk of developing long-term neurological alterations either because of an aggravated pre-existing disorder or by triggering a new one [36]. Researchers pointed that SARS-CoV-2 infection, by causing several cellular imbalances, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial and lysosomal dysfunctions, would prone the cells to be less infection-resistant, thus in the long-term it may accelerate aging of the immune system and disturbed tissues [122], and this would explain the reason COVID-19 survivors are susceptible to the development or worsening of Parkinson's disease [123], especially because the cortex and substantia nigra are the two brain regions with higher SARS-CoV-2 penetration and the most frequently associated with neurodegenerative diseases [124].

As seen in other infections, like sepsis [68], reactive microglia and astrocytes are a part of the neuroinflammation cascade, a process that can be beneficial in eliminating pathogens; however, when exacerbated or sustained, it tends to be detrimental, which generates imbalances in neurotransmitters and causes short- and long-term clinical manifestations, and these pathophysiological mechanisms may also be involved in the neurological manifestations of COVID-19 survivors.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings discussed in this review indicate that the systemic inflammatory response induced by SARS-CoV-2 seems enough to set off the alarms on its potential association with neuroinflammation, regardless of the presence of the virus in the brain. This interplay between periphery and brain is controlled by brain barriers, and the exposure to SARS-CoV-2 virus can disrupt this control, damaging this important protection against the deleterious consequences of systemic inflammation and favoring the entry of pro-inflammatory cytokines and peripheral immune cells into the CNS. Therefore, glial responsiveness displays an exaggerated release of pro-inflammatory mediators that induces synaptic loss and demyelination, reinforcing the evidence that neuroinflammation associated with COVID-19 is involved in subsequent neurodegeneration and cognitive decline.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

Fabricia Petronilho is a National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) research fellow. The funding sources were not involved in the conduction of the research, preparation of the article, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

Author Contributions

Amanda Della Giustina and Fabricia Petronilho conceived and coordinated the manuscript preparation. Kiuanne Lobo Metzker and Sandra Bonfante prepared the table. Richard Simon Machado and Mariana Pereira de Souza Goldim revised the table. Larissa Joaquim and Lucineia Gaisnki Danielski wrote the manuscript. Fabricia Petronilho revised and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Santa Catarina State Foundation for Research Support (FAPESC) and National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq).

Funding Statement

Fabricia Petronilho is a National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) research fellow. The funding sources were not involved in the conduction of the research, preparation of the article, or the decision to submit the article for publication.

References

- 1.Xie J, Ding C, Li J, Wang Y, Guo H, Lu Z, et al. Characteristics of patients with coronavirus disease (COVID-19) confirmed using an IgM-IgG antibody test. J Med Virol. 2020 Oct;92((10)):2004–2010. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu H, Stratton CW, Tang YW. Outbreak of pneumonia of unknown etiology in Wuhan, China: the mystery and the miracle. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr;92((4)):401–402. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee A, Morling J. COVID19: the need for public health in a time of emergency. Public Health. 2020 May;182:188–189. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silva CMd S, Andrade ADN, Nepomuceno B, Xavier DS, Lima E, Gonzalez I, et al. Evidence-based physiotherapy and functionality in adult and pediatric patients with COVID-19. J Hum Growth Dev. 2021;30((1)):148–155. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williamson EJ, Walker AJ, Bhaskaran K, Bacon S, Bates C, Morton CE, et al. Factors associated with COVID-19-related death using OpenSAFELY. Nature. 2020;584((7821)):430–436. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schnitzer M, Schöttl SE, Kopp M, Barth M. COVID-19 stay-at-home order in Tyrol, Austria: sports and exercise behaviour in change? Public Health. 2020 Aug;185:218–220. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2020.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heneka MT, Golenbock D, Latz E, Morgan D, Brown R. Immediate and long-term consequences of COVID-19 infections for the development of neurological disease. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2020;12((1)):69. doi: 10.1186/s13195-020-00640-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hascup ER, Hascup KN. Does SARS-CoV-2 infection cause chronic neurological complications? Geroscience. 2020;42((4)):1083–1087. doi: 10.1007/s11357-020-00207-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grifoni A, Weiskopf D, Ramirez SI, Mateus J, Dan JM, Moderbacher CR, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181((7)):1489–501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ragab D, Salah Eldin H, Taeimah M, Khattab R, Salem R. The COVID-19 cytokine storm; What we know so far. Front Immunol. 2020 Jun;11:1446. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thompson MR, Kaminski JJ, Kurt-Jones EA, Fitzgerald KA. Pattern recognition receptors and the innate immune response to viral infection. Viruses. 2011;3((6)):920–940. doi: 10.3390/v3060920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li X, Geng M, Peng Y, Meng L, Lu S. Molecular immune pathogenesis and diagnosis of COVID-19. J Pharm Anal. 2020;10((2)):102–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2020.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li G, Fan Y, Lai Y, Han T, Li Z, Zhou P, et al. Coronavirus infections and immune responses. J Med Virol. 2020 Apr;92((4)):424–432. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang F, Kream RM, Stefano GB. Long-term respiratory and neurological sequelae of COVID-19. Med Sci Monit. 2020 Nov;26:1–10. doi: 10.12659/MSM.928996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singal CMS, Jaiswal P, Seth P. SARS-CoV-2, More than a respiratory virus: its potential role in neuropathogenesis. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11((13)):1887–1899. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Azkur AK, Akdis M, Azkur D, Sokolowska M, van de Veen W, Brüggen MC, et al. Immune response to SARS-CoV-2 and mechanisms of immunopathological changes in COVID-19. Allergy Eur J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;75((7)):1564–1581. doi: 10.1111/all.14364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, Qu J, Gong F, Han Y, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395((10223)):507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lai CC, Shih TP, Ko WC, Tang HJ, Hsueh PR. Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) and coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): the epidemic and the challenges. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020 Mar;55((3)):105924. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, Ren L, Zhao J, Hu Y, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020 Feb;395((10223)):497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ruan Q, Yang K, Wang W, Jiang L, Song J. Clinical predictors of mortality due to COVID-19 based on an analysis of data of 150 patients from Wuhan, China. Intensive Care Med. 2020 May;46((5)):846–848. doi: 10.1007/s00134-020-05991-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mehta P, McAuley DF, Brown M, Sanchez E, Tattersall RS, Manson JJ, et al. COVID-19: consider cytokine storm syndromes and immunosuppression. Lancet. 2020 Mar;395((10229)):1033–1034. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30628-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alonso-Bellido IM, Bachiller S, Vázquez G, Cruz-Hernández L, Martínez E, Ruiz-Mateos E, et al. The other side of SARS-CoV-2 infection: neurological sequelae in patients. Front Aging Neurosci. 2021 Apr;13:632673. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.632673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nalleballe K, Reddy Onteddu S, Sharma R, Dandu V, Brown A, Jasti M, et al. Spectrum of neuropsychiatric manifestations in COVID-19. Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Aug;88:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schirinzi T, Landi D, Liguori C. COVID-19: dealing with a potential risk factor for chronic neurological disorders. J Neurol. 2021;268((4)):1171–1178. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10131-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ong W-Y, Go M-L, Wang D-Y, Cheah IK-M, Halliwell B. Effects of antimalarial drugs on neuroinflammation-potential use for treatment of COVID-19-related neurologic complications. Mol Neurobiol. 2021;58((1)):106–117. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02093-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baker HA, Safavynia SA, Evered LA. The “third wave”: impending cognitive and functional decline in COVID-19 survivors. Br J Anaesth. 2021;126((1)):44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2020.09.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pandharipande PP, Girard TD, Ely EW. Long-term cognitive impairment after critical illness. N Engl J Med. 2014;370((2)):185–186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Amruta N, Chastain WH, Paz M, Solch RJ, Murray-Brown IC, Befeler JB, et al. SARS-CoV-2 mediated neuroinflammation and the impact of COVID-19 in neurological disorders. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2021;58:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2021.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alemanno F, Houdayer E, Parma A, Spina A, Del Forno A, Scatolini A, et al. COVID-19 cognitive deficits after respiratory assistance in the subacute phase: a COVID-rehabilitation unit experience. PLoS One. 2021;16((2)):e0246590. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0246590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaywant A, Vanderlind WM, Alexopoulos GS, Fridman CB, Perlis RH, Gunning FM. Frequency and profile of objective cognitive deficits in hospitalized patients recovering from COVID-19. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2021 Dec;46((13)):2235–2240. doi: 10.1038/s41386-021-00978-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raman B, Cassar MP, Tunnicliffe EM, Filippini N, Griffanti L, Alfaro-Almagro F, et al. Medium-term effects of SARS-CoV-2 infection on multiple vital organs, exercise capacity, cognition, quality of life and mental health, post-hospital discharge. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;31:100683. doi: 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Versace V, Sebastianelli L, Ferrazzoli D, Romanello R, Ortelli P, Saltuari L, et al. Intracortical GABAergic dysfunction in patients with fatigue and dysexecutive syndrome after COVID-19. Clin Neurophysiol. 2021;132((5)):1138–1143. doi: 10.1016/j.clinph.2021.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miskowiak KW, Johnsen S, Sattler SM, Nielsen S, Kunalan K, Rungby J, et al. Cognitive impairments four months after COVID-19 hospital discharge: pattern, severity and association with illness variables. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2021;46:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2021.03.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blazhenets G, Schroeter N, Bormann T, Thurow J, Wagner D, Frings L, et al. Slow but evident recovery from neocortical dysfunction and cognitive impairment in a series of chronic COVID-19 patients. J Nucl Med. 2021;62((7)):910–915. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.121.262128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amalakanti S, Arepalli KVR, Jillella JP. Cognitive assessment in asymptomatic COVID-19 subjects. Virusdisease. 2021;32((1)):146–149. doi: 10.1007/s13337-021-00663-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helms J, Kremer S, Merdji H, Clere-Jehl R, Schenck M, Kummerlen C, et al. Neurologic features in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. N Engl J Med. 2020;382((23)):2268–2270. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2008597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.D'Ardes D, Carrarini C, Russo M, Dono F, Speranza R, Digiovanni A, et al. Low molecular weight heparin in COVID-19 patients prevents delirium and shortens hospitalization. Neurol Sci. 2021;42((4)):1527–1530. doi: 10.1007/s10072-020-04887-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowles KH, McDonald M, Barrón Y, Kennedy E, O'Connor M, Mikkelsen M. Surviving COVID-19 after hospital discharge: symptom, functional, and adverse outcomes of home health recipients. Ann Intern Med. 2021;174((3)):316–325. doi: 10.7326/M20-5206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Payne S, Jankowski A, Shutes-David A, Ritchey K, Tsuang DW. Mild COVID-19 disease course with protracted delirium in a cognitively impaired patient over the age of 85 years. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2020;22((4)):20l02721. doi: 10.4088/PCC.20l02721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu Z, McGoogan JM. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72314 cases from the Chinese center for disease control and prevention. JAMA. 2020 Apr;323((13)):1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Oldfield E, Malwal SR. COVID-19 and other pandemics: how might they be prevented? ACS Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;6((7)):1563–1566. doi: 10.1021/acsinfecdis.0c00291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Quan C, Li C, Ma H, Li Y, Zhang H. Immunopathogenesis of coronavirus-induced acute respiratory distress syndrome (Ards): potential infection-associated hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2020;34((1)):e00074–20. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00074-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paules CI, Marston HD, Fauci AS. Coronavirus infections-more than just the common cold. JAMA. 2020 Feb;323((8)):707–708. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.0757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Batah SS, Fabro AT. Pulmonary pathology of ARDS in COVID-19: a pathological review for clinicians. Respir Med. 2021 Jan;176:106239. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by the Novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS coronavirus. J Virol. 2020 Jan;94((7)):e00127–20. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shang J, Ye G, Shi K, Wan Y, Luo C, Aihara H, et al. Structural basis of receptor recognition by SARS-CoV-2. Nature. 2020 May;581((7807)):221–224. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2179-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dong M, Zhang J, Ma X, Tan J, Chen L, Liu S, et al. ACE2, TMPRSS2 distribution and extrapulmonary organ injury in patients with COVID-19. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020 Nov;131:110678. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Channappanavar R, Zhao J, Perlman S. T cell-mediated immune response to respiratory coronaviruses. Immunol Res. 2014;59((1–3)):118–128. doi: 10.1007/s12026-014-8534-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Matthay MA, Zemans RL, Zimmerman GA, Arabi YM, Beitler JR, Mercat A, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Prim. 2019;5((1)):18. doi: 10.1038/s41572-019-0069-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tian S, Xiong Y, Liu H, Niu L, Guo J, Liao M, et al. Pathological study of the 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) through postmortem core biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2020 Jun;33((6)):1007–1014. doi: 10.1038/s41379-020-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Battaglini D, Brunetti I, Anania P, Fiaschi P, Zona G, Ball L, et al. Neurological manifestations of severe SARS-CoV-2 infection: potential mechanisms and implications of individualized mechanical ventilation settings. Front Neurol. 2020 Aug;11:845. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.00845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fajgenbaum DC, June CH. Cytokine storm. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec;383((23)):2255–2273. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra2026131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hu B, Huang S, Yin L. The cytokine storm and COVID-19. J Med Virol. 2021 Jan;93((1)):250–256. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bal A, Agrawal R, Vaideeswar P, Arava S, Jain A. COVID-19: an up-to-date review − From morphology to pathogenesis. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2020 Jul;63((3)):358–366. doi: 10.4103/IJPM.IJPM_779_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.D'ardes D, Boccatonda A, Rossi I, Guagnano MT, Santilli F, Cipollone F, et al. COVID-19 and RAS: unravelling an unclear relationship. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Apr;21((8)):E3003. doi: 10.3390/ijms21083003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Catanzaro M, Fagiani F, Racchi M, Corsini E, Govoni S, Lanni C. Immune response in COVID-19: addressing a pharmacological challenge by targeting pathways triggered by SARS-CoV-2. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020 Dec;5((1)):84. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0191-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhu Z, Cai T, Fan L, Lou K, Hua X, Huang Z, et al. Clinical value of immune-inflammatory parameters to assess the severity of coronavirus disease 2019. Int J Infect Dis. 2020 Jun;95:332–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Del Valle DM, Kim-Schulze S, Huang HH, Beckmann ND, Nirenberg S, Wang B, et al. An inflammatory cytokine signature predicts COVID-19 severity and survival. Nat Med. 2020 Oct;26((10)):1636–1643. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lippi G, Plebani M. Procalcitonin in patients with severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): a meta-analysis. Clin Chim Acta. 2020 Jun;505:190–191. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Terpos E, Ntanasis-Stathopoulos I, Elalamy I, Kastritis E, Sergentanis TN, Politou M, et al. Hematological findings and complications of COVID-19. Am J Hematol. 2020 Jul;95((7)):834–847. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Huang I, Pranata R. Lymphopenia in severe coronavirus disease-2019 (COVID-19): systematic review and meta-analysis. J Intensive Care. 2020 May;8((1)):36. doi: 10.1186/s40560-020-00453-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Iannaccone G, Scacciavillani R, Del Buono MG, Camilli M, Ronco C, Lavie CJ, et al. Weathering the cytokine storm in COVID-19: therapeutic implications. CardioRenal Med. 2020 Sep;10((5)):277–287. doi: 10.1159/000509483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen G, Wu D, Guo W, Cao Y, Huang D, Wang H, et al. Clinical and immunological features of severe and moderate coronavirus disease 2019. J Clin Invest. 2020 May;130((5)):2620–2629. doi: 10.1172/JCI137244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim JS, Lee JY, Yang JW, Lee KH, Effenberger M, Szpirt W, et al. Immunopathogenesis and treatment of cytokine storm in COVID-19. Theranostics. 2021;11((1)):316–329. doi: 10.7150/thno.49713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kempuraj D, Selvakumar GP, Ahmed ME, Raikwar SP, Thangavel R, Khan A, et al. COVID-19, Mast cells, cytokine storm, psychological stress, and neuroinflammation. Neuroscientist. 2020 Oct;26((5–6)):402–414. doi: 10.1177/1073858420941476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ayub M, Jin HK, Bae J-S. The blood cerebrospinal fluid barrier orchestrates immunosurveillance, immunoprotection, and immunopathology in the central nervous system. BMB Rep. 2021;54((4)):196–202. doi: 10.5483/BMBRep.2021.54.4.205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Disano KD, Linzey MR, Welsh NC, Meier JS, Pachner AR, Gilli F. Isolating central nervous system tissues and associated meninges for the downstream analysis of immune cells. J Vis Exp. 2020 May;2020((159)) doi: 10.3791/61166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Danielski LG, Giustina AD, Badawy M, Barichello T, Quevedo J, Dal-Pizzol F, et al. Brain barrier breakdown as a cause and consequence of neuroinflammation in sepsis. Mol Neurobiol. 2018;55((2)):1045–1053. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-0356-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keaney J, Campbell M. The dynamic blood-brain barrier. FEBS J. 2015;282((21)):4067–4079. doi: 10.1111/febs.13412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Engelhardt B, Sorokin L. The blood-brain and the blood-cerebrospinal fluid barriers: function and dysfunction. Semin Immunopathol. 2009;31((4)):497–511. doi: 10.1007/s00281-009-0177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Liu Y, Wang L, Du N, Yin X, Shao H, Yang L. Ramelteon ameliorates LPS-induced hyperpermeability of the Blood-Brain Barrier (BBB) by activating Nrf2. Inflammation. 2021 Apr;44((5)):1750–1761. doi: 10.1007/s10753-021-01451-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hauptmann J, Johann L, Marini F, Kitic M, Colombo E, Mufazalov IA, et al. Interleukin-1 promotes autoimmune neuroinflammation by suppressing endothelial heme oxygenase-1 at the blood–brain barrier. Acta Neuropathol. 2020 Oct;140((4)):549–567. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02187-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yao Z, Bai Q, Wang G. Mechanisms of oxidative stress and therapeutic targets following intracerebral hemorrhage. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:8815441. doi: 10.1155/2021/8815441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ashraf U, Ding Z, Deng S, Ye J, Cao S, Chen Z. Pathogenicity and virulence of Japanese encephalitis virus: neuroinflammation and neuronal cell damage. Virulence. 2021;12((1)):968–980. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1899674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Erickson MA, Rhea EM, Knopp RC, Banks WA. Interactions of sars-cov-2 with the blood–brain barrier. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Mar;22((5)):2681–2628. doi: 10.3390/ijms22052681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hewitt KC, Marra DE, Block C, Cysique LA, Drane DL, Haddad MM, et al. Central nervous system manifestations of COVID-19: a critical review and proposed research agenda. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. 2022;28((3)):311–325. doi: 10.1017/S1355617721000345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Guadarrama-Ortiz P, Choreño-Parra JA, Sánchez-Martínez CM, Pacheco-Sánchez FJ, Rodríguez-Nava AI, García-Quintero G. Neurological aspects of SARS-CoV-2 infection: mechanisms and manifestations. Front Neurol. 2020 Sep;11:1039. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.01039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hamming I, Timens W, Bulthuis MLC, Lely AT, Navis GJ, van Goor H. Tissue distribution of ACE2 protein, the functional receptor for SARS coronavirus. A first step in understanding SARS pathogenesis. J Pathol. 2004 Jun;203((2)):631–637. doi: 10.1002/path.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Generoso JS, Barichello de Quevedo JL, Cattani M, Lodetti BF, Sousa L, Collodel A, et al. Neurobiology of COVID-19: how can the virus affect the brain? Braz J Psychiatry. 2021;43((6)):650–664. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2020-1488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Welcome MO, Mastorakis NE. Neuropathophysiology of coronavirus disease 2019: neuroinflammation and blood brain barrier disruption are critical pathophysiological processes that contribute to the clinical symptoms of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Inflammopharmacology. 2021;29((4)):939–963. doi: 10.1007/s10787-021-00806-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pipolo C, Bulfamante AM, Schillaci A, Banchetti J, Castellani L, Saibene AM, et al. Through the back door: expiratory accumulation of SARS-Cov-2 in the olfactory mucosa as mechanism for CNS penetration. Int J Med Sci. 2021 Apr;18((10)):2102–2108. doi: 10.7150/ijms.56324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Desforges M, Le Coupanec A, Dubeau P, Bourgouin A, Lajoie L, Dubé M, et al. Human coronaviruses and other respiratory viruses: underestimated opportunistic pathogens of the central nervous system? Viruses. 2019 Dec;12((1)):14. doi: 10.3390/v12010014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Postolache TT, Benros ME, Brenner LA. Targetable biological mechanisms implicated in emergent psychiatric conditions associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021 Apr;78((4)):353–354. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.2795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zubair AS, McAlpine LS, Gardin T, Farhadian S, Kuruvilla DE, Spudich S. Neuropathogenesis and neurologic manifestations of the coronaviruses in the age of coronavirus disease 2019: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2020 Aug;77((8)):1018–1027. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Mahalaxmi I, Kaavya J, Mohana Devi S, Balachandar V. COVID-19 and olfactory dysfunction: a possible associative approach towards neurodegenerative diseases. J Cell Physiol. 2021 Feb;236((2)):763–770. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Espíndola OM, Gomes YCP, Brandão CO, Torres RC, Siqueira M, Soares CN, et al. Inflammatory cytokine patterns associated with neurological diseases in coronavirus disease 2019. Ann Neurol. 2021;89((5)):1041–1045. doi: 10.1002/ana.26041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dinnes J, Deeks JJ, Berhane S, Taylor M, Adriano A, Davenport C, et al. Rapid, point-of-care antigen and molecular-based tests for diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021 Mar;3((3)):CD013705. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD013705.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kenyeres B, Ánosi N, Bányai K, Mátyus M, Orosz L, Kiss A, et al. Comparison of four PCR and two point of care assays used in the laboratory detection of SARS-CoV-2. J Virol Methods. 2021 Apr;293:114165. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2021.114165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Pajo AT, Espiritu AI, Apor ADAO, Jamora RDG. Neuropathologic findings of patients with COVID-19: a systematic review. Neurol Sci. 2021;42((4)):1255–1266. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05068-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kurushina OV, Barulin AE. Effects of COVID-19 on the central nervous system. Zh Nevrol Psihiatr Im SS Korsakova. 2021;121((1)):92–97. doi: 10.17116/jnevro202112101192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fisicaro F, Di Napoli M, Liberto A, Fanella M, Di Stasio F, Pennisi M, et al. Neurological sequelae in patients with COVID-19: a histopathological perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Feb;18((4)):1415. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18041415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Østergaard L. SARS CoV-2 related microvascular damage and symptoms during and after COVID-19: consequences of capillary transit-time changes, tissue hypoxia and inflammation. Physiol Rep. 2021 Feb;9((3)):e14726. doi: 10.14814/phy2.14726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Marshall M. How COVID-19 can damage the brain. Nature. 2020 Sep;585((7825)):342–343. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02599-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Conklin J, Frosch MP, Mukerji SS, Rapalino O, Maher MD, Schaefer PW, et al. Susceptibility-weighted imaging reveals cerebral microvascular injury in severe COVID-19. J Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb;421:117308. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2021.117308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Douedi S, Chaudhri M, Miskoff J. Anti-interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody for cytokine storm in COVID-19. Ann Thorac Med. 2020 Jul;15((3)):171–173. doi: 10.4103/atm.ATM_286_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Soy M, Keser G, Atagündüz P, Tabak F, Atagündüz I, Kayhan S. Cytokine storm in COVID-19: pathogenesis and overview of anti-inflammatory agents used in treatment. Clin Rheumatol. 2020 Jul;39((7)):2085–2094. doi: 10.1007/s10067-020-05190-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Pellegrini L, Albecka A, Mallery DL, Kellner MJ, Paul D, Carter AP, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infects the brain choroid plexus and disrupts the blood-CSF barrier in human brain organoids. Cell Stem Cell. 2020 Dec;27((6)):951–61.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Dal-Pizzol F, Rojas HA, Dos Santos EM, Vuolo F, Constantino L, Feier G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 and metalloproteinase-9 activities are associated with blood-brain barrier dysfunction in an animal model of severe sepsis. Mol Neurobiol. 2013;48((1)):62–70. doi: 10.1007/s12035-013-8433-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zhang Q, Zheng M, Betancourt CE, Liu L, Sitikov A, Sladojevic N, et al. Increase in blood-brain barrier (BBB) permeability is regulated by MMP3 via the ERK signaling pathway. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021 Mar;2021:6655122. doi: 10.1155/2021/6655122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Comim CM, Vilela MC, Constantino LS, Petronilho F, Vuolo F, Lacerda-Queiroz N, et al. Traffic of leukocytes and cytokine up-regulation in the central nervous system in sepsis. Intensive Care Med. 2011;37((4)):711–718. doi: 10.1007/s00134-011-2151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Tay TL, Savage JC, Hui CW, Bisht K, Tremblay MÈ. Microglia across the lifespan: from origin to function in brain development, plasticity and cognition. J Physiol. 2017;595((6)):1929–1945. doi: 10.1113/JP272134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Tremblay ME, Madore C, Bordeleau M, Tian L, Verkhratsky A. Neuropathobiology of COVID-19: the role for glia. Front Cell Neurosci. 2020 Nov;14:592214. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2020.592214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Han RT, Kim RD, Molofsky AV, Liddelow SA. Astrocyte-immune cell interactions in physiology and pathology. Immunity. 2021 Feb;54((2)):211–224. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Wang Y, Fu AKY, Ip NY. Instructive roles of astrocytes in hippocampal synaptic plasticity: neuronal activity-dependent regulatory mechanisms. FEBS J. 2021 Apr;289((8)):2202–2218. doi: 10.1111/febs.15878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wang Y, Fu WY, Cheung K, Hung KW, Chen C, Geng H, et al. Astrocyte-secreted IL-33 mediates homeostatic synaptic plasticity in the adult hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2021 Jan;118((1)):e2020810118. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2020810118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Escartin C, Galea E, Lakatos A, O'Callaghan JP, Petzold GC, Serrano-Pozo A, et al. Reactive astrocyte nomenclature, definitions, and future directions. Nat Neurosci. 2021;24((3)):312–325. doi: 10.1038/s41593-020-00783-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Sonneville R, Verdonk F, Rauturier C, Klein IF, Wolff M, Annane D, et al. Understanding brain dysfunction in sepsis. Ann Intensive Care. 2013;3((1)):15–11. doi: 10.1186/2110-5820-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Sasannejad C, Ely EW, Lahiri S. Long-term cognitive impairment after acute respiratory distress syndrome: a review of clinical impact and pathophysiological mechanisms. Crit Care. 2019;23((1)):352. doi: 10.1186/s13054-019-2626-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Baig AM, Khaleeq A, Ali U, Syeda H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: tissue distribution, host-virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2020;11((7)):995–998. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.0c00122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Divani AA, Andalib S, Biller J, Di Napoli M, Moghimi N, Rubinos CA, et al. Central nervous system manifestations associated with COVID-19. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2020;20((12)):60. doi: 10.1007/s11910-020-01079-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Al-Dalahmah O, Thakur KT, Nordvig AS, Prust ML, Roth W, Lignelli A, et al. Neuronophagia and microglial nodules in a SARS-CoV-2 patient with cerebellar hemorrhage. Acta Neuropathol Commun. 2020;8((1)):147–147. doi: 10.1186/s40478-020-01024-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lang M, Buch K, Li MD, Mehan WA, Lang AL, Leslie-Mazwi TM, et al. Leukoencephalopathy associated with severe COVID-19 Infection: sequela of hypoxemia? Am J Neuroradiol. 2020 Jun;41((9)):1641–1645. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Słońska A, Cymerys J, Chodkowski M, Bąska P, Krzyżowska M, Bańbura MW. Human herpesvirus type 2 infection of primary murine astrocytes causes disruption of the mitochondrial network and remodeling of the actin cytoskeleton: an in vitro morphological study. Arch Virol. 2021;166((5)):1371–1383. doi: 10.1007/s00705-021-05025-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen R, Wang K, Yu J, Howard D, French L, Chen Z, et al. The spatial and cell-type distribution of SARS-CoV-2 receptor ACE2 in the human and mouse brains. Front Neurol. 2020 Jan;11:573095. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.573095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Matschke J, Lütgehetmann M, Hagel C, Sperhake JP, Schröder AS, Edler C, et al. Neuropathology of patients with COVID-19 in Germany: a post-mortem case series. Lancet Neurol. 2020 Nov;19((11)):919–929. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30308-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Kanberg N, Ashton NJ, Andersson LM, Yilmaz A, Lindh M, Nilsson S, et al. Neurochemical evidence of astrocytic and neuronal injury commonly found in COVID-19. Neurology. 2020 Sep;95((12)):e1754–9. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Virhammar J, Kumlien E, Fällmar D, Frithiof R, Jackmann S, Sköld MK, et al. Acute necrotizing encephalopathy with SARS-CoV-2 RNA confirmed in cerebrospinal fluid. Neurology. 2020 Sep;95((10)):445–449. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Deigendesch N, Sironi L, Kutza M, Wischnewski S, Fuchs V, Hench J, et al. Correlates of critical illness-related encephalopathy predominate postmortem COVID-19 neuropathology. Acta Neuropathol. 2020 Oct;140((4)):583–586. doi: 10.1007/s00401-020-02213-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Franke C, Ferse C, Kreye J, Reincke SM, Sanchez-Sendin E, Rocco A, et al. High frequency of cerebrospinal fluid autoantibodies in COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms. Brain Behav Immun. 2021;93:415–419. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.12.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.El-Sayed A, Aleya L, Kamel M. COVID-19: a new emerging respiratory disease from the neurological perspective. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28((30)):40445–59. doi: 10.1007/s11356-021-12969-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Paniz-Mondolfi A, Bryce C, Grimes Z, Gordon RE, Reidy J, Lednicky J, et al. Central nervous system involvement by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) J Med Virol. 2020 Jul;92((7)):699–702. doi: 10.1002/jmv.25915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Lippi A, Domingues R, Setz C, Outeiro TF, Krisko A. SARS-CoV-2: at the crossroad between aging and neurodegeneration. Mov Disord. 2020;35((5)):716–720. doi: 10.1002/mds.28084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Ferini-Strambi L, Salsone M. COVID-19 and neurological disorders: are neurodegenerative or neuroimmunological diseases more vulnerable? J Neurol. 2021;268((2)):409–419. doi: 10.1007/s00415-020-10070-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Gomez-Pinedo U, Matias-Guiu J, Sanclemente-Alaman I, Moreno-Jimenez L, Montero-Escribano P, Matias-Guiu JA. Is the brain a reservoir organ for SARS-CoV2? J Med Virol. 2020 Nov;92((11)):2354–2355. doi: 10.1002/jmv.26046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]