Abstract

In brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), white matter hyperintensity (WMH) is a commonly encountered finding and is known to reflect cerebral small vessel disease. The aim of our study was to investigate the association of coronary artery calcium (CAC) with WMH and elucidate the relationship between WMH and atherosclerotic risk factors in a large-scale healthy population. This retrospective study included 1337 individuals who underwent brain MRI and CAC scoring computed tomography at healthcare centers affiliated with a tertiary hospital. Cerebral WMH was defined as Fazekas score greater than 2 on brain MRI. Intracranial artery stenosis (ICAS) was also assessed and determined to be present when stenosis was more than 50% on angiography. The associations of risk factors, CAC score, and ICAS with cerebral WMH were assessed by multivariable regression analysis. In multivariable analysis, categories of higher CAC scores showed increased associations with both periventricular and deep WMHs in a dose-dependent relationship. The presence of ICAS was also significantly related to cerebral WMH, and among the clinical variables, age and hypertension were independent risk factors. In conclusion, CAC showed a significant association with cerebral WMH in a healthy population, which might provide evidence for referring to the CAC score to identify individuals with risk of cerebral WMH.

Subject terms: Biomarkers, Diseases, Health care, Medical research, Neurology, Risk factors

Introduction

White matter hyperintensity (WMH) is a commonly encountered finding on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences of brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)1,2. Although the exact pathophysiologic mechanisms of WMH are unclear, it has been shown to be associated with atherosclerotic risk factors such as aging, hypertension, diabetes, smoking and obesity, supporting the contribution of vascular mechanisms to the development of WMH3–10. Pathological studies also revealed that WMH is caused by impaired vascular integrity, thus supporting that WMH is a reflection of small vessel disease in the brain11. In addition, WMH is clinically important as it has been shown to affect the incidence and prognosis of various neurologic disorders including cognitive decline, dementia, depression, gait disturbance, and stroke12–23.

The coronary artery calcium (CAC) score is regarded as a convenient and reliable indicator of atherosclerosis that measures an individual’s cumulative exposure, and it has been shown to be associated with ischemic stroke and cranial artery stenosis as well as coronary heart disease24,25. Cerebral small vessel disease is prone to coexist with atherosclerosis of large intracranial arteries, as small perforator vessels supplying white matter arise from the large basal arteries26–28. Many studies have revealed a relationship between WMH and atherosclerotic risk factors or carotid artery atherosclerosis; however, only a few studies have focused on the relationship between CAC burden and WMH, and these studies were performed exclusively in elderly or male individuals29–32.

With the improved accessibility to neuroimaging in recent years, the high prevalence and clinical importance of WMHs have been increasingly recognized as a predictor of cognitive decline and stroke outcomes19–23. This study was motivated by the idea that if the CAC score can be used in clinical practice for predicting the risk of WMH, which is a prognostic factor for various neurologic disorders, it can be a convenient and useful tool for identifying individuals who might benefit from additional studies such as brain MRI19–23. We hypothesized that WMH would show strong association with CAC burden, an indicator of atherosclerosis, in a large cohort of healthy individuals from the general population. In addition, we sought to contribute to understanding the mechanism of WMH development by identifying relevant clinical risk factors. Thus, the primary aim of this study was to investigate the association of CAC with WMH in a healthy population. Second, the purpose of this study was to elucidate the relationship between WMH and risk factors for atherosclerosis.

Methods

Study population

This study was a general population-based, cross-sectional, retrospective study. We searched the electronic database of participants who underwent health check-ups, including brain MRI and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA), at the Total Healthcare Center of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital in Seoul and Suwon between January 2016 and December 2019 and identified 3983 consecutive adult participants. The study population consisted of examinees who underwent computed tomography (CT) for CAC scoring and brain imaging as a part of comprehensive health check-ups, which are common health screening methods in Korea. For reference, all employees in Korea are required by law to undergo regular annual or biennial health examinations, so many of the participants were employees of various companies or local governmental organizations or family members of employees.

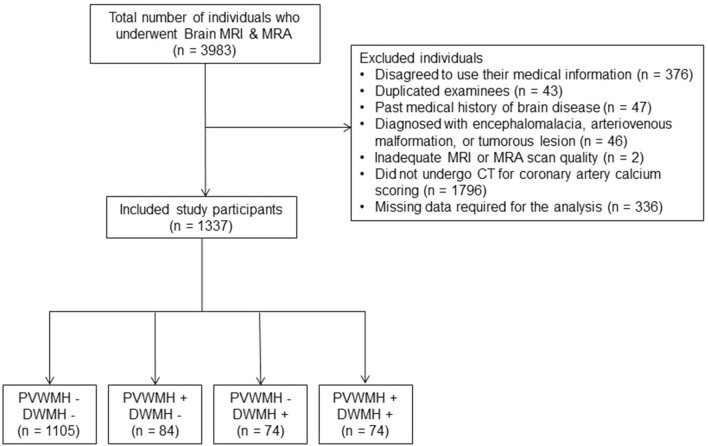

Of the 3983 individuals, 2646 were excluded for the following reasons: (a) individuals who did not consent to the use of medical information for any research purpose in the self-administered questionnaires conducted before the examination (n = 376); (b) individuals with duplicated tests were excluded if they underwent repeated examinations during the study period (n = 43), and CAC scoring CT and brain imaging performed on the same day or at the nearest time interval were selected for the study; (c) individuals with a known medical history of dementia, Parkinson’s disease, hydrocephalus, previous brain surgery, brain tumor, Moyamoya disease, stroke or hemorrhage (n = 47); (d) individuals detected with significant cerebral pathology during the image analysis, such as encephalomalacia resulting from a previous stroke (measuring larger than 15 mm in diameter) or an old traumatic hemorrhage, an arteriovenous malformation, or a tumorous lesion (n = 46); (e) individuals with MRI or MRA scans with inadequate quality for image analysis (n = 2); (f) individuals who did not undergo CAC scoring CT (n = 1796); and (g) individuals with missing numeric data required for the analysis, including body mass index (BMI) and homocysteine level (n = 336). A flow diagram of the included study participants is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the included participants. MRI Magnetic resonance imaging, MRA Magnetic resonance angiography, PVWMH Periventricular white matter hyperintensity, DWMH Deep white matter hyperintensity.

Therefore, 1337 consecutive individuals (mean age, 51.63 ± 9.20 years old; age range, 20–89 years; 1157 [86.54%] male patients) were included in the study. The clinical and imaging findings of all participants were retrospectively assessed. This study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital (IRB No. 2020-12-036-006). The requirement to obtain informed consent was waived by the IRB of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital due to the use of deidentified data and the retrospective study design. All study methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

Clinical assessment

We collected the clinical data of the individuals, including sex, age, BMI, systolic and diastolic blood pressure, smoking history, physical activity, and diagnosis and treatment of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease. From the standardized, self-administered questionnaires, we collected data on each individual’s medical and smoking histories and whether they regularly engaged in more than 10 min of vigorous exercise at least 3 times per week.

Since all the participants’ examinations were conducted by appointment at the Total Healthcare Center of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, laboratory tests were conducted after 12 h of fasting on the same day as brain MRI and MRA and data including glucose, glyco hemoglobin (HbA1c), total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, triglyceride and homocysteine levels were collected.

Hypertension was defined as current use of antihypertensive drugs, systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 mmHg33. Diabetes was defined as current use of antidiabetic medication, a fasting glucose level ≥ 126 mg/dL or an HbA1c level ≥ 6.5%34. Dyslipidemia was defined as current use of lipid-lowering agents, total cholesterol ≥ 240 mg/dL, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol ≥ 160 mg/dL, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol < 40 mg/dL or triglycerides ≥ 200 mg/dL35.

Brain MRI & MRA assessments

All individuals underwent brain MRI and MRA using a 1.5-T MRI scanner (Optima MR360, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI or Signa HDxt, GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI) using an eight-channel head coil. The imaging protocol included axial T1-weighted images (repetition time [TR]/echo time [TE] = 417–450/9 ms or 400–450/10 ms), T2-weighted images (TR/TE = 4343–4694/100–110 ms or 4084–4494/95–104 ms), FLAIR images (TR/TE = 11,000/127–138 ms or 8800/128–130 ms), and three-dimensional time-of-flight (TOF) MRA images (TR/TE = 28/7 ms or 27/3 ms, slice thickness = 1.2 mm). The slice thickness of all imaging protocols, except TOF MRA, was 5 mm.

The degree of periventricular and deep WMHs were rated separately according to the Fazekas scale1 for each subject, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1 online. PVWMH was scored as follows: 0 = absence, 1 = caps or pencil-thin lining, 2 = smooth halo, and 3 = irregular periventricular hyperintensities extending into the deep white matter. DWMH was classified as follows: 0 = absence, 1 = punctate foci, 2 = beginning confluence of foci, and 3 = large confluent areas. Since cerebral WMH grade 2 or higher is known to be clinically relevant as it is prone to be symptomatic and progressive, we categorized subjects with Fazekas scores of 2 and 3 into the PVWMH and DWMH groups36,37.

Intracranial artery stenosis (ICAS) was defined as more than 50% stenosis of the intracranial arteries by TOF MRA analysis based on the Warfarin-Aspirin Symptomatic Intracranial Disease (WASID) method38. The included analyzed vessels were the internal carotid artery from the cavernous segment, up to the M2 segment of the middle cerebral artery, the A2 segment of the anterior cerebral artery, the P2 segment of the posterior cerebral artery, the basilar artery, and intracranial segments of the vertebral arteries.

All radiological assessments were performed by a neuroradiologist (J.Y. K.) who was blinded to all clinical and laboratory data. The interobserver reliability of the visual scales was evaluated with the assessment of 700 randomly selected subjects by a second trained radiologist (J.Y. C.), and the intraobserver reliability was assessed with more than a 2-month interval after the first reading. The visual assessment of PVWMH, DWMH, and ICAS showed good interrater (Cohen’s weighted kappa: 0.7, 0.81, and 0.67, respectively; n = 700) and intrarater (Cohen’s weighted kappa: 0.92, 0.88, and 0.65, respectively; n = 1339) agreement.

Coronary calcium score assessment

The CAC score was evaluated for individuals who underwent CT for CAC scoring within 5 years from the time that brain MRI and MRA were performed39. Of the 1337 individuals, 686 underwent brain imaging on the same day, and 651 underwent brain imaging on another day within 5 years.

CAC was detected with a LightSpeed VCT XTe-64-slice multidetector CT (GE Healthcare, Tokyo, Japan) at both the Seoul and Suwon Centers using the same scanning protocol of 2.5 mm thickness, 400 ms rotation time, 120 kV tube voltage and 124 mAs (310 mA × 0.4 s) tube current under electrocardiogram-gated dose modulation. The CAC score was calculated from the 4 major epicardial coronary arteries (left main, left anterior descending, left circumflex and right coronary arteries) according to Agatston et al.40. The technicians who performed CT were blinded to any subject information, and the CAC score was automatically determined using HEARTBEAT-CS software (Philips, Cleveland, Ohio, USA). The CAC scores were categorized into three groups: 0, 1–100, and > 100.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics between subjects with and without cerebral WMH were compared using the χ2 test for categorical variables and Student’s t test or the Mann‒Whitney test for continuous variables, as appropriate. Variables with a normal distribution are presented as the mean ± standard deviation, while nonnormally distributed variables are presented as the median and interquartile range. Dummy variables were introduced for missing values for the categorical variables.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses were conducted, and odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated to evaluate the relationship between cerebral WMH and CAC scores and atherosclerotic risk factors. Since the prevalence of WMH increases with age and varies with sex, adjustment for age and sex was applied in all performed multivariable analyses to evaluate the association between other variables and WMH18. Different multivariable logistic regression models were used to assess whether the CAC score has an independent relationship with cerebral WMH even after adjustment for atherosclerotic risk factors and the presence of ICAS as confounders, which were reported to be related to WMH in previous reports10,26,27,41. Model 1 adjusted for age and sex; model 2 adjusted for age, sex, and atherosclerotic risk factors (BMI, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current or former smoker, regular exercise, history of coronary artery disease, and homocysteine level); and model 3 adjusted for age, sex, atherosclerotic risk factors, and presence of ICAS. The presence of cerebral WMH according to the CAC score category was evaluated using a CAC score of 0 as a reference.

Statistical analyses were performed by using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA) and R studio version 3.6.3 (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA). A two-tailed p value < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

Results

The baseline characteristics of the 1337 individuals are shown in Table 1. The mean age of the participants was evaluated based on brain MRI scan time and was 51.63 ± 9.20 years, and 86.54% of the study population was male. The leading atherosclerotic risk factor in the cohort was current or former smoking history (57.82%), followed by dyslipidemia (51.76%) and hypertension (28.65%). Regarding the radiological variables, 158 subjects (11.82%) had PVWMH, 148 (11.07%) had DWMH, and 21 (1.57%) had ICAS. Regarding the CAC scores, 849 subjects (63.5%) had a CAC score of 0, 332 (24.83%) had a score between 0‒100, and 156 (11.67%) had a score above 100.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (n = 1337).

| Missing data, n | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age, years [SD] | 0 | 51.63 ± 9.20 |

| Male, n (%) | 0 | 1,157 (86.54) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 [SD] | 0 | 24.88 ± 3.04 |

| Biochemical variables | ||

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg [SD] | 0 | 115.95 ± 12.45 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg [SD] | 0 | 75.73 ± 9.52 |

| Glucose, mg/dL [SD] | 0 | 101.57 ± 18.01 |

| HbA1c, % [SD] | 1 | 5.73 ± 0.68 |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dL [SD] | 0 | 192.74 ± 38.65 |

| LDL cholesterol, mg/dL [SD] | 0 | 130.98 ± 37.58 |

| HDL cholesterol, mg/dL [SD] | 0 | 54.53 ± 14.13 |

| Triglycerides, mg/dL [SD] | 0 | 138.66 ± 102.11 |

| Homocysteine, μmol/L [SD] | 0 | 10.52 ± 4.51 |

| Medications | ||

| Antihypertensive agents, n (%) | 0 | 286 (21.39) |

| Antidiabetic agents, n (%) | 0 | 103 (7.7) |

| Lipid-lowering agents, n (%) | 0 | 222 (16.6) |

| Risk factors | ||

| Hypertension, n (%) | 0 | 383 (28.65) |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 0 | 157 (11.74) |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 0 | 692 (51.76) |

| Current or former smoker, n (%) | 43 | 773 (57.82) |

| Regular exercisea, n (%) | 25 | 455 (34.03) |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 0 | 45 (3.37) |

| CAC score, median [IQR] | 0 | 0 [0–18] |

| CAC 0 | 849 (63.5) | |

| CAC 0‒100 | 332 (24.83) | |

| CAC > 100 | 156 (11.67) | |

| Radiological variables | ||

| PVWMH, n (%) | 0 | 158 (11.82) |

| DWMH, n (%) | 0 | 148 (11.07) |

| ICAS, n (%) | 0 | 21 (1.57) |

PVWMH Periventricular white matter hyperintensity, DWMH Deep white matter hyperintensity, LDL Low-density lipoprotein, HDL High-density lipoprotein, HbA1c Glycohemoglobin, CAD Coronary artery disease, CAC Coronary artery calcium, ICAS Intracranial artery stenosis, SD Standard deviation, IQR Interquartile range.

aRegular engagement in vigorous exercise for more than 10 min at least 3 times per week.

In univariate analysis, age, sex, and the majority of the atherosclerotic risk factors except BMI, dyslipidemia and current or former history of smoking were significantly associated with the presence of cerebral WMH (p < 0.05) (Table 2). Individuals with PVWMH and DWMH were older than those without and had a greater burden of hypertension, diabetes, history of coronary artery disease, CAC, and ICAS. In univariate analysis, the percentage of females and subjects who responded that they performed regular exercise was higher in the groups with WMH. The median (interquartile range; IQR) CAC score was 62 (IQR 0‒269.5) in the PVWMH group and 46.5 (IQR 0‒192) in the DWMH group. The distribution of CAC categories according to the presence of PVWMH and DWMH is shown in Fig. 2. The proportion of categories with higher CAC scores increased as the degree of accompanying WMH increased.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the groups with or without PVWMH and DWMH.

| PVWMH | p | DWMH | p | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absent (n = 1179) | Present (n = 158) | Absent (n = 1189) | Present (n = 148) | |||

| Clinical variables | ||||||

| Age, years [SD] | 50.22 ± 8.35 | 62.1 ± 8.47 | < 0.001 | 50.41 ± 8.44 | 61.39 ± 9.26 | < 0.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 1037 (87.96) | 120 (75.95) | < 0.001 | 1048 (88.14) | 109 (73.65) | < 0.001 |

| BMI, kg/m2 [SD] | 24.85 ± 3.04 | 25.09 ± 2.99 | 0.350 | 24.84 ± 3.07 | 25.17 ± 2.77 | 0.945 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 293 (24.85) | 90 (56.96) | < 0.001 | 302 (25.4) | 81 (54.73) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 114 (9.67) | 43 (27.22) | < 0.001 | 121 (10.18) | 36 (24.32) | < 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 615 (52.16) | 77 (48.73) | 0.418 | 615 (51.72) | 77 (52.03) | 0.945 |

| Current or former smoker, n (%) | 691 (58.61) | 82 (51.9) | 0.080 | 688 (57.86) | 85 (57.43) | 0.015 |

| Regular exercisea, n (%) | 385 (32.65) | 70 (44.3) | 0.003 | 398 (33.47) | 57 (38.51) | 0.003 |

| History of CAD, n (%) | 34 (2.88) | 11 (6.96) | 0.008 | 33 (2.78) | 12 (8.11) | 0.002 |

| CAC score, median [IQR] | 0 [0‒7] | 62 [0‒269.5] | < 0.001 | 0 [0‒9] | 46.5 [0‒192] | < 0.001 |

| Radiological variables | ||||||

| PVWMH, n (%) | – | – | 84 (7.06) | 74 (50) | < 0.001 | |

| DWMH, n (%) | 74 (6.28) | 74 (46.84) | < 0.001 | – | – | |

| ICAS, n (%) | 8 (0.68) | 13 (8.23) | < 0.001 | 7 (0.59) | 14 (9.46) | < 0.001 |

PVWMH Periventricular white matter hyperintensity, DWMH Deep white matter hyperintensity, BMI Body mass index, LDL Low-density lipoprotein, HDL High-density lipoprotein, HbA1c Glycohemoglobin, CAD Coronary artery disease, CAC Coronary artery calcium, ICAS Intracranial artery stenosis, SD Standard deviation, IQR Interquartile range.

aRegular engagement in vigorous exercise for more than 10 min at least 3 times per week.

Figure 2.

Percentages of CAC score categories according to the presence of PVMWH (a), DWMH (b) and PVWMH or DWMH (c). CAC Coronary artery calcium, WMH White matter hyperintensity, PVWMH Periventricular white matter hyperintensity, DWMH Deep white matter hyperintensity.

In multivariable regression analysis, age (OR 1.13; 95% CI 1.10‒1.16, OR 1.11; 95% CI 1.08‒1.14, respectively) and hypertension (OR 2.29; 95% CI 1.50‒3.50, OR 1.98; 95% CI 1.30‒3.02, respectively) were independent significant clinical predictors of PVWMH and DWMH after adjustment for age, sex, atherosclerotic risk factors (BMI, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current or former smoker, exercise, history of coronary artery disease, and homocysteine level), and ICAS (all p < 0.05) (Table 3). There were no significant associations between WMH and sex, BMI, presence of diabetes or dyslipidemia, history of cigarette smoking or regular exercise after adjustment.

Table 3.

Multivariable analysis for PVWMH and DWMH after adjusting for confounders.

| Model 1b | Model 2c | Model 3d | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PVWMH | DWMH | PVWMH | DWMH | PVWMH | DWMH | |||||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

| CAC score | ||||||||||||

| 0 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | ||||||

| 0–99 | 2.31 (1.45–3.73) | < 0.001 | 1.83 (1.15–2.92) | 0.011 | 2.23 (1.37–3.62) | 0.001 | 1.60 (0.99–2.58) | 0.057 | 2.22 (1.36–3.61) | 0.001 | 1.59 (0.98–2.58) | 0.061 |

| > 100 | 6.28 (3.76–10.49) | < 0.001 | 4.56 (2.74–7.59) | < 0.001 | 5.76 (3.31–10.05) | < 0.001 | 3.96 (2.29–6.84) | < 0.001 | 5.45 (3.11–9.54) | < 0.001 | 3.66 (2.10–6.38) | < 0.001 |

| Age | 1.13 (1.11–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.09–1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.10–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | < 0.001 | 1.13 (1.10–1.16) | < 0.001 | 1.11 (1.08–1.14) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.86 (0.52–1.42) | 0.55 | 0.69 (0.42–1.13) | 0.142 | 0.88 (0.47–1.63) | 0.679 | 0.60 (0.32–1.13) | 0.114 | 0.84 (0.45–1.56) | 0.578 | 0.55 (0.29–1.04) | 0.066 |

| Hypertension | 2.34 (1.54–3.57) | < 0.001 | 2.04 (1.35–3.10) | 0.001 | 2.29 (1.50–3.50) | < 0.001 | 1.98 (1.30–3.02) | 0.001 | ||||

| BMI | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 0.303 | 1.06 (0.98–1.13) | 0.134 | 1.03 (0.96–1.11) | 0.362 | 1.05 (0.98–1.13) | 0.173 | ||||

| Diabetes | 1.43 (0.86–2.39) | 0.168 | 1.18 (0.71–1.98) | 0.52 | 1.30 (0.77–2.19) | 0.328 | 1.04 (0.61–1.77) | 0.897 | ||||

| Dyslipidemia | 0.69 (0.46–1.04) | 0.075 | 0.88 (0.59–1.31) | 0.52 | 0.68 (0.45–1.03) | 0.071 | 0.86 (0.57–1.30) | 0.477 | ||||

| Current or former smoker | 0.74 (0.46–1.20) | 0.225 | 1.56 (0.93–2.62) | 0.09 | 0.76 (0.47–1.24) | 0.269 | 1.65 (0.97–2.81) | 0.062 | ||||

| Regular exercisea | 0.97 (0.85–1.11) | 0.646 | 1.04 (0.93–1.16) | 0.526 | 0.98 (0.86–1.11) | 0.723 | 1.05 (0.94–1.17) | 0.419 | ||||

| History of CAD | 0.52 (0.21–1.28) | 0.154 | 0.88 (0.38–2.02) | 0.759 | 0.45 (0.17–1.16) | 0.099 | 0.76 (0.32–1.85) | 0.551 | ||||

| Homocysteine | 1.01 (0.96–1.07) | 0.666 | 0.92 (0.84–1.10) | 0.04 | 1.02 (0.96–1.07) | 0.589 | 0.92 (0.85–1.00) | 0.056 | ||||

| ICAS | 3.97 (1.31–12.06) | 0.015 | 7.11 (2.33–21.77) | 0.001 | ||||||||

PVWMH Periventricular white matter hyperintensity, DWMH Deep white matter hyperintensity, ICAS Intracranial artery stenosis, CAC Coronary artery calcium, CAD Coronary artery disease, CI Confidence interval, OR Odds ratio.

aRegular engagement in vigorous exercise for more than 10 min at least 3 times per week.

bAdjusted for age and sex.

cAdjusted for Model 1 + atherosclerotic risk factors (BMI, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia, current or former smoker, regular exercise, history of CAD, and homocysteine level).

dAdjusted for Model 2 + ICAS.

The categories of higher CAC scores showed an increased association with cerebral WMH in a dose-dependent relationship compared to the reference category with a CAC score of 0 even after adjusting for the confounding factors. For both PVWMH and DWMH, the category with a CAC score of more than 100 (OR 5.45; 95% CI 3.11‒9.54, OR 3.66; 95% CI 2.10‒6.38, respectively) showed a greater association than the category with a CAC score between 0 and 100 (OR 2.22; 95% CI 1.36‒3.61, OR 1.59; 95% CI 0.98‒2.58, respectively). In comparing the association with CAC between the PVWMH and DWMH groups, all three models of the multivariable analysis revealed a higher correlation with PVWMH in both CAC score categories. The presence of ICAS also showed significant associations with both PVWMH (OR 3.97; 95% CI 1.31‒12.06) and DWMH (OR 7.11; 95% CI 2.33‒21.77).

The variance inflation factor was calculated for all regression models to evaluate potential multicollinearity, and no problematic multicollinearity was found (Supplementary Table 1 online).

Discussion

In this study, the risk of cerebral WMH increased with higher CAC scores in a dose-dependent relationship, and the results were statistically significant after adjusting for confounding atherosclerotic risk factors. Our findings are in agreement with those of previous studies showing an association between CAC and brain MRI abnormalities, further supporting the association of CAC with small vessels of the brain as well as atherosclerosis of large vessels29–32.

Interestingly, the ORs of the CAC scores were slightly higher for the PVWMH group than for the DWMH group in all three models of the multivariable analysis. This difference might be related to the fact that it is presumed that dissimilarity exists among the pathophysiological processes and risk factors between PVWMHs and DWMHs11,42,43. PVWMHs are typically symmetrically present in both cerebral hemispheres, which is suggestive of diffuse perfusion disturbances, whereas DWMHs often have an asymmetric distribution, suggesting that they are caused by local perfusion disturbances44. Since the periventricular region is supplied by end arteries of long medullary and perforating branches45, it is particularly vulnerable to hypoperfusion and ischemia when the autoregulatory mechanism that maintains constant brain perfusion is impaired by arteriosclerosis or lipohyalinosis46–49. In particular, several studies have demonstrated that reflections of systemic atherosclerosis, such as hypertension, diabetes and the presence of aortic atherosclerosis, are preferentially associated with PVWMH50–53, which supports our study results that the CAC score, age, and hypertension have higher ORs for PVWMH than for DWMH in all models.

In this study, the presence of ICAS was strongly associated with cerebral WMH, and this result can be explained by the fact that significant stenosis of the major intracranial artery reduces local or territorial brain perfusion, and this chronic hypoperfusion promotes lipohyalinosis, which is the mechanism underlying WMH development26,54.

In line with many previous studies conducted on different ethnicities3,27,28,55, our study also showed that age and hypertension have independent significant associations with cerebral WMH in the multivariable analysis. However, associations between WMH and other atherosclerotic risk factors have shown varying results among previous reports27,28,37,56. The reasons for these varying results are likely due to differences in the study population, the criteria for defining the risk factors, or the method used to analyze WMH, which necessitates further studies.

There are several limitations of this study that should be noted. First, this is a retrospective study from an Asian population in single-brand healthcare centers. The risk of selection bias is possible as a significant number of study participants were of working age and more than half were male, which is due to the unique characteristics of Korea that the country requires companies to provide regular health examinations to their employees. To reduce bias in cohort studies, long-term, longitudinal and prospective studies such as the Rotterdam study57 or the Framingham study58 should be pursued, and there have been many previous reports focusing on the relationship between cerebral WMH and various atherosclerotic risk factors using the Rotterdam and Framingham study cohorts4,59–63. However, since none of the existing studies have focused on the association between WMH and CAC in the normal general population, our study results have clinical significance. Second, since the MRI analysis was performed visually by radiologists, the objectivity might be insufficient. However, we sought to overcome this limitation by including a large number of participants and defining subjects with at least moderate or higher WMH as a positive group. In addition, we conducted inter- and intraobserver reliability tests, which showed good agreement. There are also previous reports showing a high correlation between the visual scoring method using the Fazekas scale and volumetry analysis for evaluation of the extent of WMH64,65. Third, individuals with brain pathologies were excluded through a self-administered questionnaire regarding past medical history and image analysis in individuals with obvious disease, and it may not have been possible to filter out individuals with subclinical disease. In addition, the brain MRI protocol in our institution for health screening does not include enhanced images, so there is a possibility of missed cases with brain pathology that enhances which is not conspicuous in T1-, T2-weighted and FLAIR images, and accuracy in judging the presence of ICAS would have been relatively low compared to enhanced MRA. Fourth, as the participants of this study were from a healthy general population mostly without any disease, the proportion of subjects with ICAS was relatively small.

Nonetheless, the present study included a larger number of healthy individuals than previous studies aiming to elucidate the association between WMH and CAC, and to our knowledge, this is the first study to include adults from a healthy population without any sex or age restrictions31,32.

Since the accessibility of brain imaging and the average life expectancy have significantly increased, the importance of cerebral WMH and various related neurologic diseases such as dementia and stroke is being emphasized, but these diseases remain unconquered. The presence of cerebral WMH lesions is associated with steeper cognitive decline, dementia, depression, and stroke, and there is accumulating evidence that controlling certain atherosclerotic risk factors can prevent the occurrence and progression of WMH12–23,66–69. Therefore, the results of our study might provide evidence for referring to the CAC score in screening individuals at risk of cerebral WMH, which is an important risk and prognostic factor for various neurologic diseases, thus identifying patients who can benefit from active diagnostic and therapeutic measures. Future research is warranted to evaluate whether CAC plays a significant and independent role in the development of WMH in longitudinal and prospective studies from various regions, age groups, and ethnicities, and other MRI markers of cerebral small vessel disease should also be incorporated for integrated insight.

In conclusion, the CAC score as well as age and hypertension showed a significant association with cerebral WMH in a large-scale healthy population. The CAC score, an indicator of atherosclerotic burden, has a potential role in predicting individuals with a risk of cerebral WMH in clinical practice.

Supplementary Information

Author contributions

J.C. and J.Y.K. conceptualized and designed the study and conducted M.R.I. analysis. J.Y.K. wrote the original manuscript, tables and illustrated all figures. J.C., J.Y.K., and H.K. contributed to the data acquisition and study implementation. J.Y.K. and S.K. contributed to the statistical analysis of the collected data. J.C., J.Y.K., H.J.C., S.H.K., J.L., and J.E.P. contributed to the data interpretation and provided comments. JEP reviewed the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Data availability

The dataset analyzed during this study is not publicly available as it consists of individuals’ sensitive personal information. The data are available from the Total Healthcare Center of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital upon reasonable request from qualified researchers trained in research with human subjects. Every request will be reviewed by the institutional review board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, and researchers can access the data according to the approval conditions.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-25654-9.

References

- 1.Fazekas F, et al. White matter signal abnormalities in normal individuals: Correlation with carotid ultrasonography, cerebral blood flow measurements, and cerebrovascular risk factors. Stroke. 1988;19:1285–1288. doi: 10.1161/01.str.19.10.1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wardlaw JM, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12:822–838. doi: 10.1016/s1474-4422(13)70124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liao D, et al. Presence and severity of cerebral white matter lesions and hypertension, its treatment, and its control. The ARIC study atherosclerosis risk in communities study. Stroke. 1996;27:2262–2270. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.12.2262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeerakathil T, et al. Stroke risk profile predicts white matter hyperintensity volume: The framingham study. Stroke. 2004;35:1857–1861. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.0000135226.53499.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murray AD, et al. Brain white matter hyperintensities: Relative importance of vascular risk factors in nondemented elderly people. Radiology. 2005;237:251–257. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2371041496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park K, et al. Significant association between leukoaraiosis and metabolic syndrome in healthy subjects. Neurology. 2007;69:974–978. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000266562.54684.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.DeCarli C, et al. Predictors of brain morphology for the men of the NHLBI twin study. Stroke. 1999;30:529–536. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.3.529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Longstreth WT, Jr, et al. Clinical correlates of white matter findings on cranial magnetic resonance imaging of 3301 elderly people. The cardiovascular health study. Stroke. 1996;27:1274–1282. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.de Leeuw FE, et al. A follow-up study of blood pressure and cerebral white matter lesions. Ann. Neurol. 1999;46:827–833. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(199912)46:6<827::aid-ana4>3.3.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lampe L, et al. Visceral obesity relates to deep white matter hyperintensities via inflammation. Ann. Neurol. 2019;85:194–203. doi: 10.1002/ana.25396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young VG, Halliday GM, Kril JJ. Neuropathologic correlates of white matter hyperintensities. Neurology. 2008;71:804–811. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319691.50117.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prins ND, Scheltens P. White matter hyperintensities, cognitive impairment and dementia: An update. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2015;11:157–165. doi: 10.1038/nrneurol.2015.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garde E, Mortensen EL, Krabbe K, Rostrup E, Larsson HB. Relation between age-related decline in intelligence and cerebral white-matter hyperintensities in healthy octogenarians: A longitudinal study. Lancet. 2000;356:628–634. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(00)02604-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baezner H, et al. Association of gait and balance disorders with age-related white matter changes: The LADIS study. Neurology. 2008;70:935–942. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000305959.46197.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van Sloten TT, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease and association with higher incidence of depressive symptoms in a general elderly population: The AGES-reykjavik study. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2015;172:570–578. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14050578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Debette S, Markus HS. The clinical importance of white matter hyperintensities on brain magnetic resonance imaging: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2010;341:c3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van der Flier WM, et al. Small vessel disease and general cognitive function in nondisabled elderly: The LADIS study. Stroke. 2005;36:2116–2120. doi: 10.1161/01.Str.0000179092.59909.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Groot JC, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and cognitive function: The rotterdam scan study. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:145–151. doi: 10.1002/1531-8249(200002)47:2<145::aid-ana3>3.3.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arsava EM, et al. Severity of leukoaraiosis correlates with clinical outcome after ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2009;72:1403–1410. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a18823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee SH, et al. White matter lesions and poor outcome after intracerebral hemorrhage: A nationwide cohort study. Neurology. 2010;74:1502–1510. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181dd425a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kloppenborg RP, Nederkoorn PJ, Geerlings MI, van den Berg E. Presence and progression of white matter hyperintensities and cognition: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2014;82:2127–2138. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0000000000000505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith EE, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging white matter hyperintensities and brain volume in the prediction of mild cognitive impairment and dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:94–100. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Román GC, et al. Vascular dementia: Diagnostic criteria for research studies. Report of the NINDS-AIREN international workshop. Neurology. 1993;43:250–260. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.2.250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hermann DM, et al. Coronary artery calcification is an independent stroke predictor in the general population. Stroke. 2013;44:1008–1013. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.111.678078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oh HG, Chung PW, Rhee EJ. Increased risk for intracranial arterial stenosis in subjects with coronary artery calcification. Stroke. 2015;46:151–156. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.114.006996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nam KW, et al. Cerebral white matter hyperintensity is associated with intracranial atherosclerosis in a healthy population. Atherosclerosis. 2017;265:179–183. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chutinet A, et al. Severity of leukoaraiosis in large vessel atherosclerotic disease. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2012;33:1591–1595. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee S-J, et al. The leukoaraiosis is more prevalent in the large artery atherosclerosis stroke subtype among Korean patients with ischemic stroke. BMC Neurol. 2008;8:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-8-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vidal JS, et al. Coronary artery calcium, brain function and structure: The AGES-reykjavik study. Stroke. 2010;41:891–897. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.110.579581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rosano C, Naydeck B, Kuller LH, Longstreth WT, Jr, Newman AB. Coronary artery calcium: Associations with brain magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities and cognitive status. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2005;53:609–615. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53208.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Khan MMH, et al. The association between coronary artery calcification and subclinical cerebrovascular diseases in men: An observational study. J. Atheroscler. Thromb. 2020;27:995–1009. doi: 10.5551/jat.51284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim BJ, et al. Advanced coronary artery calcification and cerebral small vessel diseases in the healthy elderly. Circ J. 2011;75:451–456. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-10-0762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Unger T, et al. International society of hypertension global hypertension practice guidelines. Hypertension. 2020;75:1334–1357. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.15026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Inzucchi SE. Clinical practice. Diagnosis of diabetes. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:542–550. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1103643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rhee EJ, et al. 2018 Guidelines for the management of dyslipidemia. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019;34:723–771. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2019.188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Neumann-Haefelin T, et al. Leukoaraiosis is a risk factor for symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage after thrombolysis for acute stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:2463–2466. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000239321.53203.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwon HM, et al. Frequency, risk factors, and outcome of coexistent small vessel disease and intracranial arterial stenosis: Results from the stenting and aggressive medical management for preventing recurrent stroke in intracranial stenosis (SAMMPRIS) trial. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:36–42. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samuels OB, Joseph GJ, Lynn MJ, Smith HA, Chimowitz MI. A standardized method for measuring intracranial arterial stenosis. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 2000;21:643–646. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greenland P, Blaha MJ, Budoff MJ, Erbel R, Watson KE. Coronary calcium score and cardiovascular risk. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;72:434–447. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.05.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Agatston AS, et al. Quantification of coronary artery calcium using ultrafast computed tomography. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1990;15:827–832. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(90)90282-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiszniewska M, Devuyst G, Bogousslavsky J, Ghika J, van Melle G. What is the significance of leukoaraiosis in patients with acute ischemic stroke? Arch. Neurol. 2000;57:967–973. doi: 10.1001/archneur.57.7.967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fazekas F, et al. Pathologic correlates of incidental MRI white matter signal hyperintensities. Neurology. 1993;43:1683–1689. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.9.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scarpelli M, et al. MRI and pathological examination of post-mortem brains: The problem of white matter high signal areas. Neuroradiology. 1994;36:393–398. doi: 10.1007/bf00612126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.ten Dam VH, et al. Decline in total cerebral blood flow is linked with increase in periventricular but not deep white matter hyperintensities. Radiology. 2007;243:198–203. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2431052111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.De Reuck J. The human periventricular arterial blood supply and the anatomy of cerebral infarctions. Eur. Neurol. 1971;5:321–334. doi: 10.1159/000114088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsushita K, et al. Periventricular white matter lucency and cerebral blood flow autoregulation in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1994;23:565–568. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.23.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc. Brain Metab. Rev. 1990;2:161–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pantoni L, Garcia JH. Pathogenesis of leukoaraiosis: A review. Stroke. 1997;28:652–659. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.3.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.O'Sullivan M, et al. Patterns of cerebral blood flow reduction in patients with ischemic leukoaraiosis. Neurology. 2002;59:321–326. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.3.321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.de Leeuw FE, et al. Aortic atherosclerosis at middle age predicts cerebral white matter lesions in the elderly. Stroke. 2000;31:425–429. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.2.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ylikoski A, et al. White matter hyperintensities on MRI in the neurologically nondiseased elderly. Analysis of cohorts of consecutive subjects aged 55 to 85 years living at home. Stroke. 1995;26:1171–1177. doi: 10.1161/01.str.26.7.1171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kozachuk WE, et al. White matter hyperintensities in dementia of Alzheimer's type and in healthy subjects without cerebrovascular risk factors. A magnetic resonance imaging study. Arch. Neurol. 1990;47:1306–1310. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1990.00530120050009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lindgren A, et al. Cerebral lesions on magnetic resonance imaging, heart disease, and vascular risk factors in subjects without stroke A population-based study. Stroke. 1994;25:929–934. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.5.929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hatazawa J, Shimosegawa E, Satoh T, Toyoshima H, Okudera T. Subcortical hypoperfusion associated with asymptomatic white matter lesions on magnetic resonance imaging. Stroke. 1997;28:1944–1947. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.10.1944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schmidt R, et al. The natural course of MRI white matter hyperintensities. J. Neurol. Sci. 2002;203–204:253–257. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(02)00300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lin Q, et al. Incidence and risk factors of leukoaraiosis from 4683 hospitalized patients: A cross-sectional study. Medicine. 2017;96:e7682. doi: 10.1097/md.0000000000007682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ikram MA, et al. Objectives, design and main findings until 2020 from the rotterdam study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020;35:483–517. doi: 10.1007/s10654-020-00640-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Andersson C, Johnson AD, Benjamin EJ, Levy D, Vasan RS. 70-year legacy of the framingham heart study. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2019;16:687–698. doi: 10.1038/s41569-019-0202-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bots ML, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions and atherosclerosis in the rotterdam study. Lancet. 1993;341:1232–1237. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91144-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breteler MM, et al. Cerebral white matter lesions, vascular risk factors, and cognitive function in a population-based study: The rotterdam study. Neurology. 1994;44:1246–1252. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.7.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.de Leeuw FE, et al. Prevalence of cerebral white matter lesions in elderly people: A population based magnetic resonance imaging study. The rotterdam scan study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2001;70:9–14. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.1.9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.van Dijk EJ, et al. Progression of cerebral small vessel disease in relation to risk factors and cognitive consequences: Rotterdam scan study. Stroke. 2008;39:2712–2719. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.107.513176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Petrea RE, et al. Mid to late life hypertension trends and cerebral small vessel disease in the framingham heart study. Hypertension. 2020;76:707–714. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.120.15073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sachdev P, Cathcart S, Shnier R, Wen W, Brodaty H. Reliability and validity of ratings of signal hyperintensities on MRI by visual inspection and computerised measurement. Psychiatry Res. 1999;92:103–115. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4927(99)00036-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zerna C, et al. Association of white matter hyperintensities with short-term outcomes in patients with minor cerebrovascular events. Stroke. 2018;49:919–923. doi: 10.1161/strokeaha.117.017429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.de Leeuw FE, et al. Hypertension and cerebral white matter lesions in a prospective cohort study. Brain J. Neurol. 2002;125:765–772. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lambert C, et al. Longitudinal patterns of leukoaraiosis and brain atrophy in symptomatic small vessel disease. Brain J. Neurol. 2016;139:1136–1151. doi: 10.1093/brain/aww009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Godin O, Tzourio C, Maillard P, Mazoyer B, Dufouil C. Antihypertensive treatment and change in blood pressure are associated with the progression of white matter lesion volumes: The three-city (3C)-dijon magnetic resonance imaging study. Circulation. 2011;123:266–273. doi: 10.1161/circulationaha.110.961052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.van Dijk EJ, et al. The association between blood pressure, hypertension, and cerebral white matter lesions: Cardiovascular determinants of dementia study. Hypertension. 2004;44:625–630. doi: 10.1161/01.Hyp.0000145857.98904.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analyzed during this study is not publicly available as it consists of individuals’ sensitive personal information. The data are available from the Total Healthcare Center of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital upon reasonable request from qualified researchers trained in research with human subjects. Every request will be reviewed by the institutional review board of Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, and researchers can access the data according to the approval conditions.