Abstract

Resistance to Toxoplasma gondii has been shown to be mediated by gamma interferon (IFN-γ) produced by NK, CD4+, and CD8+ T cells. While studies of SCID mice have implicated NK cells as the source of the cytokine in acute infection, several lines of evidence suggest that IFN-γ production by CD4+ T lymphocytes also plays an important role in controlling early parasite growth. To evaluate whether this function is due to nonspecific as opposed to T-cell receptor (TCR)-dependent stimulation by the parasite, we have examined the resistance to T. gondii infection of pigeon cytochrome c transgenic (PCC-Tg) Rag-2−/− mice in which all CD4+ T lymphocytes are unreactive with the protozoan. When inoculated with the ME49 strain, PCC-Tg animals exhibited only temporary control of acute infection and succumbed by day 17. Intracellular cytokine staining by flow cytometry revealed that, in contrast to infected nontransgenic controls, infected PCC-Tg animals failed to develop IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells. Moreover, the CD4+ lymphocytes from these mice showed no evidence of activation as judged by lack of upregulated expression of CD44 or CD69. Nevertheless, when acutely infected transgenic mice were primed by PCC injection, the lymphokine responses measured after in vitro antigen restimulation displayed a strong Th1 bias which was shown to be dependent on endogenous interleukin 12 (IL-12). The above findings argue that, while T. gondii-induced IL-12 cannot trigger IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells in the absence of TCR ligation, the pathogen is able to nonspecifically promote Th1 responses against nonparasite antigens, an effect that may explain the immunostimulatory properties of T. gondii infection.

Toxoplasma gondii is an intracellular protozoan that is readily controlled by the host cell-mediated immune response resulting in a chronic infection maintained by dormant parasite cysts. Host resistance to the parasite occurs in two major phases. In the initial acute phase, growth of the replicative tachyzoite stage is curbed by an interleukin 12 (IL-12)-dependent gamma interferon (IFN-γ) response that appears to involve elements of the innate immune system. In the second, adaptive phase, IFN-γ produced by sensitized CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes completes the clearance of tachyzoites from host tissues and prevents reactivation of chronic infection from the resulting cysts (reviewed in references 3 and 10).

It is generally assumed that NK cells are the major source of the IFN-γ that controls initial parasite replication during the first week of acute infection. Thus, T-lymphocyte-deficient SCID mice survive for 14 to 16 days following infection with the avirulent ME49 strain but succumb after only 8 to 9 days when simultaneously treated with neutralizing anti-IFN-γ monoclonal antibody (MAb) (5, 9). Nevertheless, evidence also exists suggesting that CD4+ and, to a lesser extent, CD8+ T cells contribute to IFN-γ-mediated host resistance during this early acute phase of the infection. Thus, infected T- and B-cell-deficient Rag mice produce only 20% of the level of serum IFN-γ displayed by infected T-cell-sufficient control animals at the same 5-day (d) time point (G. Yap, unpublished observations). In addition, in vitro CD4+ T-cell depletion partially ablates IFN-γ production by spleen cells from 5-d infected mice, and sorted CD4+ T lymphocytes from the same animals synthesized high levels of the cytokine while much lower amounts were secreted by sorted CD8+ T cells (6). Finally, common cytokine receptor γ-chain (γc) knockout (KO) mice, which lack functional NK and CD8+ T cells, have been shown to develop IFN-γ-dependent, CD4+ T-cell-mediated control of acute infection and survive into the chronic phase (17).

Although these observations support a role for CD4+ T lymphocytes in early resistance to T. gondii, the mechanism by which a major IFN-γ response is induced in these cells so rapidly (i.e., within 5 d) after host infection is unclear. One possibility is that the IL-12 burst occurring soon after host invasion nonspecifically triggers IFN-γ production from naive CD4+ T cells in a manner analogous to its induction of the latter cytokine from NK cells. Such a direct effect of IL-12 on IFN-γ production by human CD4+ T cells has previously been reported (25). That T. gondii nonspecifically promotes CD4+ T-cell function is also suggested by numerous studies demonstrating immunopotentiating effects of the parasite on the induction of cell-mediated immunity to unrelated pathogens and tumors (8, 13, 16).

In the present report, we have studied the influence of T. gondii infection on CD4+ T-cell activation and effector function in an attempt to better define the role played by these cells in the clearance of acute infection as well as the mechanisms underlying the induction of nonspecific immunity by the parasite. Our approach was to analyze host resistance and CD4+ T-cell responses in T-cell receptor (TCR) transgenic mice that recognize pigeon cytochrome c (PCC) peptide 81-104 in association with the I-Ea class II molecule (14, 20). All of the CD4+ T cells in these animals are specific for PCC since the mice were backcrossed onto a Rag-2−/− background which prevents new TCR species from being generated by endogenous V gene rearrangement. Furthermore, as shown below, this receptor does not cross-react with tachyzoite antigen (Ag). Therefore, any CD4+ T-cell responses elicited by T. gondii infection must arise nonspecifically rather than as a result of Ag-mediated TCR ligation. The results of our experiments in this model argue against a nonspecific mechanism of IFN-γ induction from CD4+ T lymphocytes during acute infection while formally demonstrating a role for the parasite in biasing bystander CD4+ T-cell responses toward a Th1 phenotype.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental animals.

C57BL/6 TCR-Cyt-5C.C7-1 transgenic mice (14, 20) were cesarean rederived and backcrossed for multiple generations with B10.A/SgSnAi animals in the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) contract facility at Taconic Farms, Inc. (Germantown, N.Y.). They were then bred with B10.D2 Rag-2−/− mice to introduce the Rag-2−/− mutation and made homozygous for B10.A, Rag-2−/−, and the TCR transgene. This strain is referred to as B10.A/SgSnAi TCR Cyt-5C.C7-1, Rag-2−/−, and was supplied by the NIAID-Taconic exchange contract. Control B10.A/SgSnAi and B10.A/Ai Rag-2−/− mice were also obtained from the NIAID-Taconic contract facility. B10.A/SgSnJ mice purchased from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, Maine) were used in some studies. Animals were sex and age matched for each experiment.

T. gondii infections, parasites, and parasite Ag preparation.

A cyst suspension of the avirulent ME49 strain of T. gondii was prepared from brains of infected C57BL/6 mice as described previously (18). For experimental infections, mice received 20 cysts in 0.5 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) intraperitoneally (i.p.). The RH strain of T. gondii was maintained by culturing the parasites at 37°C in human foreskin fibroblast monolayers. Soluble tachyzoite Ag (STAg) was prepared from sonicated RH parasites as previously described (7).

In vitro T-cell response assays.

Single-cell suspensions were prepared from homogenized spleens, and erythrocytes were removed using ACK lysing buffer (Bio Whittaker, Walkersville, Md.). Spleen cells were cultured at 3 × 105 or 1 × 105 cells per well (see figure legends for specific details) in flat-bottomed 96-well plates in 200 μl of RPMI 1640 medium (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 100 U of penicillin per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, 2 mM l-glutamine, 10 mM HEPES, and 5 × 10−5 M 2-mercaptoethanol. When 105 spleen cells per well were used, they were cultured with 5 × 105 irradiated (3,000-R) T-cell-depleted B10.A spleen cells as antigen-presenting cells (APC) (11). Spleen cell cultures were stimulated in vitro with 10 μg of STAg per ml, 10 μg of plate-bound anti-CD3 (PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.) per ml, 1 μM PCC peptide (amino acids 81 to 104, synthesized in the peptide synthesis facility, NIAID, National Institutes of Health), or live irradiated (15,000-R) tachyzoites (cell/tachyzoite ratio = 10:1). Culture supernatants were collected at 48 h for determination of IFN-γ using a previously published enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) protocol (19). IL-4 levels were measured in the same supernatants using a commercial ELISA kit (Endogen, Woburn, Mass.). For T-cell proliferation assays, cells were pulsed with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine (ICN Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Costa Mesa, Calif.) after 48 h in culture and harvested 18 h later onto glass-fiber filters using a 96-well cell harvester (Brandel, Gaithersburg, Md.). Incorporated [3H]thymidine was measured by scintillation counting in a Betaplate 1205 detector (Wallac, Gaithersburg, Md.).

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis of lymphoid cell populations.

Total spleen cells (106) were stained using anti-CD4 phycoerythrin (PE)- or Cy-Chrome-labeled rat MAb RM4-5, anti-CD8α fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated rat MAb 53-6.7, anti-NK1.1 PE-labeled mouse MAb PK136, anti-CD44 FITC-conjugated rat MAb IM7, or anti-CD69 FITC-conjugated hamster MAb H1.2F3, all purchased from PharMingen. Prior to specific labeling with antibodies, Fc receptors were blocked with anti-CD16/32 (clone 2.4G2; PharMingen). Flow cytometric analysis was performed on a FACScalibur instrument (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) using CellQuest software. Cells were gated on CD4+ for measurement of CD44 and CD69 expression.

In vivo CD4, IFN-γ, and IL-12 depletion.

For IFN-γ depletion, mice were injected i.p. with 1 mg of anti-IFN-γ MAb XMG6 (rat immunoglobulin G1 [IgG1]; cell line provided by R. Coffman, DNAX, Palo Alto, Calif.) 1 day before as well as on the day of infection with ME49. Depletion of CD4+ T cells was achieved by treating mice i.p. with 1 mg of GK1.5 MAb (4) 2 days before and on the day of parasite challenge. Injection of animals with MAb was continued on every third day, and survival was monitored. In some experiments involving PCC immunization, animals received an i.p. injection of 1 mg of anti-IL-12 p40 MAb C17.8 (rat IgG2a; cell line was a gift from G. Trinchieri, Wistar Institute, Philadelphia, Pa.) 1 day before, on the day of, and 3 days after Ag administration. Control mice were given the same dosage of a rat IgG1 MAb (GL113 MAb) specific for β-galactosidase.

Quantitation of IFN-γ-producing cells by intracellular staining.

Intracellular IFN-γ staining was performed as described previously (21) with minor modifications. Briefly, spleen cells from uninfected and ME49-infected wild-type (WT) and TCR transgenic animals were cultured in complete RPMI medium and stimulated with plate-bound anti-mouse CD3ɛ MAb (clone 145-2C11; PharMingen) at 10 μg/ml for 2.5 h. Brefeldin A (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) was added at this time at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml to prevent protein secretion, and the cultures were incubated for an additional 3.5 h. Cells were harvested and stained using anti-CD4 FITC-labeled rat MAb RM4-5 (PharMingen). After fixation in 2% paraformaldehyde, cells were permeabilized in buffer containing 0.1% saponin and restained using PE-conjugated rat anti-mouse IFN-γ (clone XMG1.2; PharMingen) or PE-conjugated rat IgG1 isotype control (clone R3-34; PharMingen). At least 100,000 events were acquired on a FACScalibur, and the data were analyzed using CellQuest software.

Measurement of in vivo responses to PCC in T. gondii-infected transgenic mice.

TCR transgenic mice were infected with 20 cysts of the avirulent ME49 strain of T. gondii via the i.p. route as described above. Five days after infection, mice were injected i.p. with 100 μl of a PBS suspension containing 50 μg of PCC (Sigma Chemical Co.) precipitated in alum or with 100 μl of PBS alone. Animals were sacrificed 5 d after PCC injection, and spleen cells were analyzed for surface markers by FACS and for in vitro production of IFN-γ and IL-4 after restimulation with Ag.

Statistical analyses.

Student's t test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of differences between data points.

RESULTS

T lymphocytes from PCC TCR transgenic mice fail to cross-react with tachyzoite Ag.

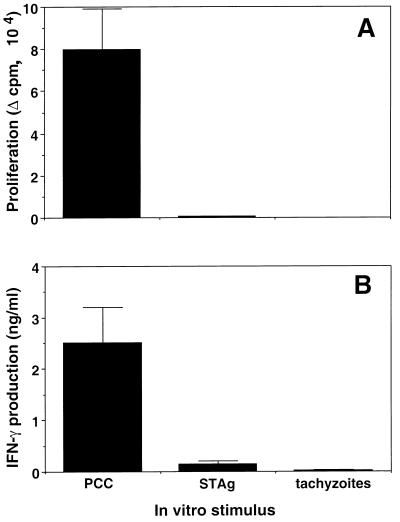

To make certain that the CD4+ T cells in PCC TCR transgenic mice fail to react with T. gondii and therefore should not respond specifically during parasite infection, spleen cells from uninfected transgenic mice were exposed in vitro to live irradiated tachyzoites, a soluble tachyzoite extract (STAg), or PCC as a positive control. As expected, these cell populations responded vigorously to PCC as assessed by both in vitro thymidine incorporation and IFN-γ production while failing to react significantly by either assay with live parasites or STAg (Fig. 1). On the basis of the above findings, we concluded that any CD4+ T-cell responses observed during infection of transgenic mice with T. gondii are unlikely to result from conventional activation through TCR ligation.

FIG. 1.

T cells from TCR transgenic mice do not proliferate (A) or produce IFN-γ (B) in response to T. gondii antigens. Spleen cells from uninfected TCR transgenic mice were cultured in duplicate at 3 × 105 cells/well in the presence of PCC peptide (1 μM; amino acids 81 to 104), STAg (10 μg/ml), or live irradiated RH (3 × 104 tachyzoites/well). An aliquot of each culture supernatant was taken to analyze IFN-γ production by ELISA after 48 h of incubation, and proliferation was determined by measuring incorporation of [3H]thymidine (1 μCi/well) added to the cultures for another 18 h. Change in counts per minute (Δ cpm) was then calculated by subtracting the incorporation obtained with unstimulated cultures (320 ± 15 cpm). Results are expressed as the means ± standard deviations of the averaged duplicate values determined for two mice per group. The modest IFN-γ response to STAg was not observed in three repeat experiments and is likely to reflect low-level IL-12-induced production of the cytokine from splenic NK cells (6) since similar levels were occasionally seen with nontransgenic B10.A control animals and FACS-sorted CD4+ T cells (99% pure) gave no response to STAg in the presence of irradiated B10.A APC (data not shown). Infection of the mice with T. gondii failed to increase these background responses to parasite Ag (data not shown).

FACS analysis of spleen cells was performed to compare the levels of cells (CD4+, CD8+, and NK1.1+) potentially responsive to T. gondii in transgenic compared with WT hosts. As shown in Fig. 2, comparable numbers of splenic CD4+ T cells were observed in the transgenic and WT mice both before and 5 d after infection with the ME49 strain of T. gondii despite the difference in TCR specificity. In contrast, as expected from the major histocompatibility complex class II restriction of the PCC-specific TCR, the spleens from the transgenic mice were deficient in CD8+ T cells both before and after infection. NK1.1+ cells, on the other hand, were present in spleens from both types of animals, although in somewhat lower numbers in the transgenic population after infection.

FIG. 2.

TCR transgenic and control B10.A mice have similar numbers of splenic CD4+ and NK1.1+ cells pre- and postinfection. Spleen cells from uninfected (A) and 5-d ME49-infected (B) WT control animals (gray bars) or TCR transgenic mice (black bars) were stained for CD4, CD8, and NK1.1 expression using directly conjugated antibodies. The total numbers of CD4+, CD8+, and NK1.1+ cells were determined by multiplying the percentages of these cell populations by the total number of spleen cells. Values represent the means ± standard errors of the means of five mice per group.

Transgenic mice exhibit partial control of acute but not chronic T. gondii infection.

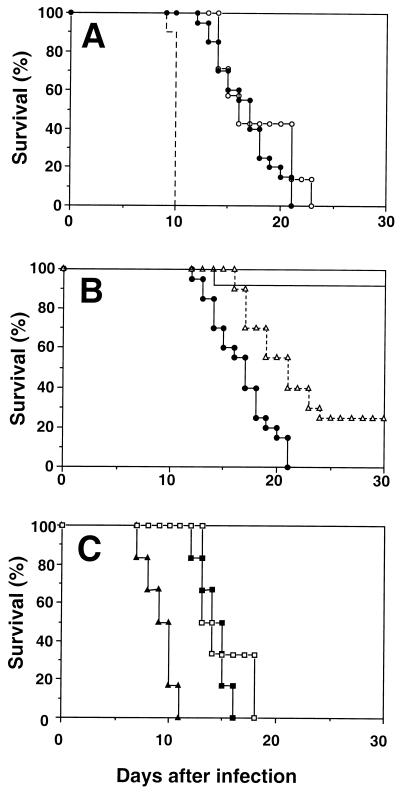

In order to assess their resistance to T. gondii, transgenic mice as well as B10.A Rag-2−/− and B10.A WT control animals were infected i.p. with 20 cysts of the ME49 strain and survival was monitored for a period of 30 days. As shown in Fig. 3, the transgenic mice succumbed to the infection between 12 and 21 d postinoculation. This survival pattern was identical to that displayed by the simultaneously infected B10.A Rag-2−/− control animals and yet clearly distinct from the mortality curve previously described for IFN-γ KO mice (18), which are highly susceptible to acute infection (Fig. 3A). Priming the TCR transgenic mice with PCC (50 μg) in alum 5 d before infection failed to increase the survival time of the animals (data not shown). The latter observation further argues against the ability of T. gondii to nonspecifically activate PCC-specific T cells into effectors.

FIG. 3.

Survival of TCR transgenic versus control mice following T. gondii infection. Mice were infected i.p. with 20 cysts of the ME49 strain, and survival was monitored over a period of 30 d. (A) Survival of infected TCR transgenic animals (closed circles) and B10.A Rag-2−/− mice (open circles) compared with literature values (18) for ME49-infected IFN-γ KO animals (dashed line). (B) Mortality of infected B10.A control mice obtained from either the Jackson Laboratory (straight line) or Taconic Farms (dashed line with triangles) and TCR transgenic animals (closed circles; same data as shown in panel A). (C) Survival of infected TCR transgenic mice treated with neutralizing MAb to IFN-γ (closed triangles), anti-CD4 MAb (open squares), or control (GL113) MAb (closed squares). Effective depletion of the CD4+ cell population was assessed by flow cytometric analysis of whole blood using a PE-conjugated anti-CD4 MAb. Experimental groups consisted of 6 to 20 mice each. Each of the three experiments shown was repeated at least once with similar results.

B10.A WT mice have been reported to be resistant to ME49 infection as judged by both survival and the low numbers of brain cysts recovered during the chronic phase (1). Surprisingly, most of the B10.A mice used as controls for our mortality experiments succumbed, dying 4 to 5 d later than the TCR transgenic animals constructed on the same background. This enhanced susceptibility proved to be a feature of B10.A mice derived from the NIAID contract at Taconic Farms (the source of both the WT and transgenic animals), since B10.A mice obtained from the Jackson Laboratory, as predicted from the previous studies, were highly resistant to the same infection (Fig. 3B). Interestingly, the unexpected early death of the Taconic B10.A WT mice was not the result of impaired control of infection, since these animals showed the same low level of cyst burden (56 ± 25 cysts/brain) at day 15 as did the corresponding B10.A animals from the Jackson Laboratory (70 ± 18). Nonetheless, the Taconic-derived TCR transgenic mice were clearly defective in host resistance as judged by their elevated cyst counts (1,617 ± 416; P = 0.002 versus recovery from B10.A mice from Taconic), which were comparable to those determined (1,844 ± 305) for simultaneously infected B10.A Rag-2−/− mice (also purchased from Taconic Farms).

Since the TCR transgenic mice were found to be more resistant than IFN-γ KO animals but equivalent to, if not more susceptible than, T-cell-deficient Rag-2−/− mice, these observations suggested that the PCC-specific T cells in the former animals are unable to nonspecifically mediate IFN-γ-dependent control of infection. In support of this conclusion, transgenic mice depleted of CD4+ T lymphocytes by MAb treatment displayed the same susceptibility to infection as did transgenic animals treated with control MAb (Fig. 3C). Nevertheless, the transgenic mice were clearly partially resistant to infection since they succumbed earlier when treated with anti-IFN-γ MAb (Fig. 3C). This partial resistance is presumably mediated by the IFN-γ produced by the significant although reduced numbers of NK cells in the transgenic animals.

CD4+ T cells in transgenic mice are not nonspecifically triggered by T. gondii to produce IFN-γ.

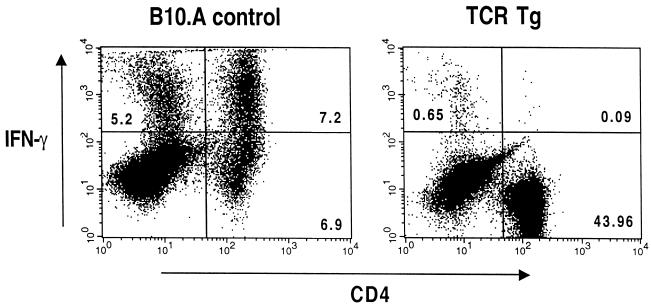

While the transgenic CD4+ T cells clearly do not contribute to host resistance, it remained possible that they are nonspecifically triggered to produce IFN-γ. In order to examine this issue directly, intracellular staining for the cytokine was performed on spleen cells obtained from WT and transgenic animals 7 d after ME49 infection. As shown in Fig. 4, 51% (7.2 of 14.1) of the CD4+ cells in the infected B10.A control mice stained positively for IFN-γ, while only 0.2% of the corresponding CD4+ cells from the PCC transgenic animals reacted positively with the same antibody. Nevertheless, the infected transgenic animals did develop significant levels of serum IFN-γ (1.8 ± 0.25 versus 0 ng/ml in uninfected mice), reflecting their early control of acute infection. Importantly, this early IFN-γ response was not reduced as a result of in vivo anti-CD4 depletion, arguing against the transgenic T cells as the source of the cytokine (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Intracellular flow cytometric analysis of IFN-γ production by CD4+ T cells. Spleen cells from 7-d infected B10.A control and TCR transgenic (TCR Tg) mice were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 for 6 h and treated with brefeldin A added for the last 2.5 h of the incubation. The splenocytes were then stained with anti-CD4 MAb, fixed, permeabilized, and subsequently restained with anti-IFN-γ MAb as described in Materials and Methods. Splenocytes from uninfected mice and cells stained with isotype control MAb failed to give significant staining in this assay (data not shown). Similar results were obtained in a second experiment.

T. gondii infection fails to alter the activation status of CD4+ T cells in PCC-immunized transgenic mice.

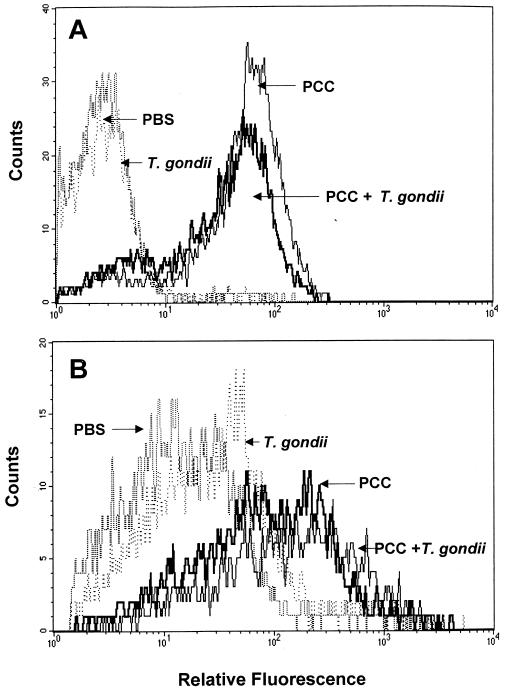

Although the above findings clearly indicate that T. gondii cannot nonspecifically trigger IFN-γ production in CD4+ T cells, it was still possible that infection with the protozoan enhances or biases T-cell responses initiated against nonparasite Ag consistent with its previously reported adjuvant effects. As a first step in investigating this hypothesis, we examined the effect of T. gondii infection on the activation status of transgenic CD4+ cells primed in vivo with PCC. In this experiment, mice were given 50 μg of PCC i.p. 5 d after ME49 infection and spleen cells were recovered 2 d later for analysis of CD69 and 5 d later for measurement of CD44. As shown in Fig. 5, in control animals not given PCC, T. gondii infection failed to elevate the expression of either activation marker on CD4+ T cells. This observation provides further evidence against nonspecific triggering of the transgenic cells by the parasite. Similarly, in PCC-primed mice, where activation was clearly visible, the presence of T. gondii infection did not result in altered CD69 or CD44 expression. Thus, Toxoplasma does not appear to nonspecifically augment or suppress CD4+ T-cell activation as judged by these markers.

FIG. 5.

T. gondii infection fails to result in upregulated expression of CD69 and CD44 on CD4+ T cells from PCC transgenic mice. PCC protein was administered i.p. 5 d after ME49 infection of TCR transgenic mice. Splenocytes were analyzed by FACS 2 d later for CD69 expression (A) and 5 d later for CD44 expression (B). The analysis was performed after gating on CD4+ cells. Control PCC transgenic animals received PBS, T. gondii, or PCC alone as indicated in the histograms. The experiment shown is representative of three performed.

T. gondii infection results in Th1-biased PCC-induced cytokine production in transgenic mice.

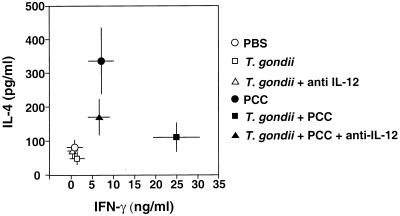

One possible explanation of the adjuvant effects of T. gondii infection on cell-mediated immune responses is that the parasite promotes, by a bystander effect, the differentiation of Th1 cells. To test this hypothesis, we analyzed the influence of ME49 infection on PCC-induced cytokine production in transgenic mice primed with the Ag in alum 5 d after parasite inoculation and sacrificed 5 d later. Spleen cells were then stimulated with PCC in vitro, and the levels of the signature cytokines IL-4 and IFN-γ were measured in culture supernatants by ELISA 48 h later. As shown in Fig. 6, uninfected transgenic mice primed with PCC developed Ag-induced cytokine responses characterized by elevated IL-4 as well as IFN-γ compared with control mice injected with PBS alone. In striking contrast, when the same PCC transgenic mice were infected with T. gondii, the PCC-induced cytokine production profile was markedly skewed toward Th1 as judged by a greater than threefold increase in IFN-γ levels and no increase in IL-4 above background levels. As expected, T. gondii infection alone failed to trigger significant IL-4 and IFN-γ responses in the transgenic animals.

FIG. 6.

IL-4 and IFN-γ production by spleen cells from PCC-immunized TCR transgenic mice infected with T. gondii. ME49-infected TCR transgenic mice were injected i.p. with PCC protein (50 μg) in alum 5 d after parasite inoculation. One group of animals received neutralizing anti-IL-12 MAb on d −1, d 0, and d 3 after PCC administration. Mice were sacrificed on d 5 following PCC injection, and spleen cells (105 cells/well) were incubated in duplicate with T-cell-depleted irradiated spleen cells as APC (5 × 105 cells/well) in the presence of 1 μM PCC peptide (amino acids 81 to 104). Supernatants were harvested 48 h later for determination of IL-4 and IFN-γ levels by ELISA, and the average value for each mouse was calculated from the duplicate cultures. Data shown indicate the means ± standard errors of the means of pooled values from three experiments each involving three to five animals. The effect of T. gondii infection on PCC-induced IFN-γ and IL-4 responses was highly significant as calculated by Student's t test (IL-4, P = 0.01; IFN-γ, P = 0.00005), as was the effect of anti-IL-12 treatment on the PCC-induced IFN-γ response in T. gondii-infected mice (P = 0.0003).

T. gondii is known to induce high levels of IL-12 during early infection. In order to analyze whether the production of this proinflammatory cytokine plays a significant role in biasing the PCC-stimulated lymphokine pattern toward a Th1 response, infected transgenic mice were given neutralizing anti-IL-12 MAb on d −1, 0, and d +3 following PCC priming. As shown in Fig. 6, this treatment completely blocked the enhancement of the PCC-induced IFN-γ production triggered by T. gondii infection. Although anti-IL-12 treatment also appeared to increase the PCC-induced IL-4 production, this effect was not statistically significant.

DISCUSSION

T. gondii is an unusual protozoan in its ability to potentiate strong cell-mediated immune responses. This property, which protects the host against mortality while promoting dormant cyst formation, may have evolved as a mechanism for ensuring parasite persistence. Indeed, the activation of the cellular immune system induced by T. gondii is so potent that it can lead to nonspecific resistance against other pathogens (13, 16) as well as both autochthonous and transplantable tumors (8). Although the nature of the host-parasite interactions that determine the immunopotentiating properties of the protozoan are not yet defined, they are likely to relate to its ability to stimulate high levels of host protective cytokines such as IFN-γ (3). The induction of IL-12 by tachyzoite products appears to be an important upstream event in this process and may promote IFN-γ-dependent resistance by both the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system (23).

At a different level, the strong cell-mediated immunity induced by T. gondii might result from a direct effect of the parasite on T-cell responses. For example, tachyzoites as well as tachyzoite extract have been shown to nonspecifically induce in vitro proliferation of murine CD8+ as well as human CD4+ cells from uninfected hosts. In the case of the murine cells, this appears to be due to a superantigen-like activity in the parasite which preferentially expands CD8+ cells expressing Vβ5 (2), while with human cells the relevant activity requires Ag processing and does not appear to involve preferential TCR usage (22).

In the present study, we have used an in vivo approach to examine possible nonspecific effects of T. gondii infection on T lymphocytes and, in particular, CD4+ T-cell function. Since previous studies in γc KO animals had suggested that CD4+ lymphocytes can mediate early resistance to ME49 infection in the absence of NK and CD8+ T cells (17), we initially focused on the question of whether or not transgenic T cells expressing an unrelated TCR could be triggered to act as IFN-γ-producing effectors. Our results clearly indicate that these CD4+ cells neither secrete IFN-γ in response to in vivo T. gondii infection nor function as effectors of acute resistance against the parasite. This finding argues that the IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T lymphocytes previously detected during early infection (6) arise as a result of conventional TCR ligation. A further implication of our results is that the early control of parasite growth by CD4+ T lymphocytes observed previously in γc KO mice is likely to result from an Ag-specific encounter and may be particularly effective because the cells have an activated memory phenotype (15).

Although B10.A PCC TCR transgenic mice were similar to B10.A Rag-2−/− animals in their resistance to infection, surprisingly, WT B10.A mice from the same Taconic colony failed to display the long-term survival predicted from their H-2a haplotype. Nevertheless, it was clear from the cyst counts performed on the same animals that they completely controlled parasite growth and in that sense were comparable to B10.A mice from the Jackson Laboratory which exhibited the predicted phenotype of prolonged survival (Fig. 3). Thus, despite this unexpected complication, one can be confident that the PCC transgenic mice indeed fail to display the parasite control shown by their WT B10.A counterparts. Although the basis of the premature mortality of the Taconic-derived B10.A mice is presently unclear, a preliminary analysis (C. M. Collazo and C. Anderson, unpublished findings) suggests that it is not the result of a detectable major or minor histocompatibility difference as determined by skin grafting. Other possible explanations include non-histocompatibility-related genetic changes or differences in the intestinal flora between the two mouse colonies.

While the results of the first part of this study indicated that T. gondii infection fails to nonspecifically activate CD4+ T lymphocytes to become IFN-γ-dependent effectors, it was still possible that the parasite influences the development and phenotype of CD4+ T cells responding as a result of TCR ligation. This possibility was tested by assaying the effect of ME49 infection on PCC-induced T-cell responses in transgenic mice. Using a protocol in which mice were exposed to T. gondii for 5 d before PCC injection, we failed to detect any effect of the infection on CD69 and CD44 expression by transgenic CD4+ T cells either in the presence or in the absence of in vivo Ag priming (Fig. 5). Thus, at least in terms of these prototypic markers, the parasite does not appear to dramatically affect the initial activation status of the T cells. Therefore, the immunostimulatory activity of T. gondii cannot be readily attributed to a nonspecific effect on CD4+ T-cell activation per se. An alternative explanation of this immunostimulatory function, for which we know of no precedent, is that lymphokines or other products of T. gondii-specific T lymphocytes nonspecifically activate bystander CD4+ T cells.

One striking immunological feature of Toxoplasma infection is the Th1-biased cytokine expression pattern that it induces (reviewed in reference 3). Although not as yet formally defined at the single-cell level, this pattern is likely to result from the skewing of lymphokine production by CD4+ as well as CD8+ and NK cells. The results presented here establish that T. gondii infection strongly biases PCC- and alum-stimulated CD4+ T-cell responses, which normally display a Th0 pattern, toward a Th1-dominated profile (Fig. 6). This potent effect on the development of CD4 type 1 cytokine expression suggests that the ability of the parasite to nonspecifically promote Th1 responses is central to its immunostimulatory influence on host resistance to other agents. In turn, since in vivo anti-IL-12 treatment prevented the development of an IFN-γ-dominated lymphokine response profile, it would appear that the induction of IL-12 is a critical event that influences Th1 biasing and could be the basis for the augmentation of resistance to unrelated pathogens and tumors seen in T. gondii-infected animals. Because IL-12 itself is essential for control of parasite growth, it is difficult to design depletion experiments in which the role of the cytokine in the generation of this nonspecific resistance can be readily tested. Nevertheless, in a number of the experimental models in which T. gondii induces nonspecific immunity (e.g., Listeria monocytogenes [24], Schistosoma mansoni [26], and Salmonella sp. [12]) recombinant IL-12 confers or enhances host control of the secondary infection.

While the above observations argue that IL-12 induction is a critical factor responsible for the immunopotentiating activity of T. gondii infection, they do not formally rule out the involvement of other stimulatory effects of the parasite on the immune system. The TCR transgenic model described here should provide a useful tool for assessing these additional determinants as well as for studying the influence of T. gondii on Ag presentation. As a second and related approach for analyzing the effects of the protozoan on processing and presentation, we have recently developed transgenic parasites expressing the model Ags ovalbumin and hen egg lysozyme. We hope that this strategy involving the combined study of transgenic parasites and TCR transgenic mice will allow us to identify the unique characteristics of the T. gondii-host interaction responsible for the potent induction of cell-mediated immunity by this pathogen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank David Stephany and Kevin L. Holmes for their invaluable advice and assistance in flow cytometry and Dragana Jankovic and Marika Kullberg for their helpful discussions and criticism.

REFERENCES

- 1.Brown C R, Mcleod R. Class I MHC genes and CD8+ T Cells determine cyst number in Toxoplasma gondii infection. J Immunol. 1990;145:3438–3441. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Denkers E Y, Caspar P, Sher A. Toxoplasma gondii possesses a superantigen activity that selectively expands murine T cell receptor V β5-bearing CD8+ lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1994;180:985–994. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denkers E Y, Gazzinelli R T. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:569–588. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dialynas D P, Wilde D B, Marrack P, Pierres A, Wall K A, Havran W, Otten G, Loken M R, Pierres M, Kappler J, et al. Characterization of the murine antigenic determinant, designated L3T4a, recognized by monoclonal antibody GK1.5: expression of L3T4a by functional T cell clones appears to correlate primarily with class II MHC antigen-reactivity. Immunol Rev. 1983;74:29–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1983.tb01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gazzinelli R T, Hieny S, Wynn T A, Wolf S, Sher A. Interleukin-12 is required for the T-lymphocyte-independent induction of interferon-γ by an intracellular parasite and induces resistance in T-cell-deficient hosts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:6115–6119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gazzinelli R T, Wysocka M, Hayashi S, Denkers E Y, Hieny S, Caspar P, Trinchieri G, Sher A. Parasite-induced IL-12 stimulates early IFN-γ synthesis and resistance during acute infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1994;153:2533–2543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grunvald E, Chiaramonte M, Hieny S, Wysocka M, Trinchieri G, Vogel S N, Gazzinelli R T, Sher A. Biochemical characterization and protein kinase C dependency of monokine-inducing activities of Toxoplasma gondii. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2010–2018. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2010-2018.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hibbs J B J, Lambert L H, Remington J S. Resistance to murine tumours conferred by chronic infection with intracellular protozoa, Toxoplasma gondii and Besnoitia jellisoni. J Infect Dis. 1971;124:587–592. doi: 10.1093/infdis/124.6.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter C A, Subauste C S, Van Cleave V H, Remington J S. Production of gamma interferon by natural killer cells from Toxoplasma gondii-infected SCID mice: regulation by interleukin-10, interleukin-12, and tumor necrosis factor alpha. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2818–2824. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.7.2818-2824.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunter C A, Suzuki Y, Subauste C S, Remington J S. Cells and cytokines in resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;219:113–125. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-51014-4_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jenkins M K, Chen C A, Jung G, Mueller D L, Schwartz R H. Inhibition of antigen-specific proliferation of type 1 murine T cell clones after stimulation with immobilized anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 1990;144:16–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kincy-Cain T, Clements J D, Bost K L. Endogenous and exogenous interleukin-12 augment the protective immune response in mice orally challenged with Salmonella dublin. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1437–1440. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.4.1437-1440.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahmoud A A F, Warren K S, Strickland G T. Acquired resistance to infection with Schistosoma mansoni induced by Toxoplasma gondii. Nature. 1976;263:56–57. doi: 10.1038/263056a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miller C, Ragheb J A, Schwartz R H. Anergy and cytokine-mediated suppression as distinct superantigen-induced tolerance mechanisms in vivo. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1–12. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nakajima H, Shores E W, Noguchi M, Leonard W J. The common cytokine receptor γ chain plays an essential role in regulating lymphoid homeostasis. J Exp Med. 1997;185:189–195. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.2.189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ruskin J, Remington J S. Immunity and intracellular infection: resistance to bacteria in mice infected with a protozoan. Science. 1968;160:72–74. doi: 10.1126/science.160.3823.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scharton-Kersten T, Nakajima H, Yap G, Sher A, Leonard W J. Infection of mice lacking the common cytokine receptor gamma-chain (γc) reveals an unexpected role for CD4+ T lymphocytes in early IFN-γ-dependent resistance to Toxoplasma gondii. J Immunol. 1998;160:2565–2569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scharton-Kersten T M, Wynn T A, Denkers E Y, Bala S, Grunvald E, Hieny S, Gazzinelli R T, Sher A. In the absence of endogenous IFN-γ, mice develop unimpaired IL-12 responses to Toxoplasma gondii while failing to control acute infection. J Immunol. 1996;157:4045–4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scott P, Natovitz P, Coffman R L, Pearce E, Sher A. Immunoregulation of cutaneous leishmaniasis. T cell lines that transfer protective immunity or exacerbation belong to different T helper subsets and respond to distinct parasite antigens. J Exp Med. 1988;168:1675–1684. doi: 10.1084/jem.168.5.1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seder R A, Paul W E, Davis M M, Fazekas De St. Groth B. The presence of interleukin-4 during in vitro priming determines the lymphokine-producing potential of CD4+ T cells from T cell receptor transgenic mice. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1091–1098. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.4.1091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Su H C, Cousens L P, Fast L D, Slifka M K, Bungiro R D, Ahmed R, Biron C A. CD4+ and CD8+ T cell interactions in IFN-γ and IL-4 responses to viral infections: requirements for IL-2. J Immunol. 1998;160:5007–5017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Subauste C S, Fuh F, De Waal Malefyt R, Remington J S. Alpha beta T cell response to Toxoplasma gondii in previously unexposed individuals. J Immunol. 1998;160:3403–3411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trinchieri G. Interleukin-12: a proinflammatory cytokine with immunoregulatory functions that bridge innate resistance and antigen-specific adaptive immunity. Annu Rev Immunol. 1995;13:251–276. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.13.040195.001343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wagner R D, Steinberg H, Brown J F, Czuprynski C J. Recombinant interleukin-12 enhances resistance of mice to Listeria monocytogenes infection. Microb Pathog. 1994;17:175–186. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1994.1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu C Y, Demeure C, Kiniwa M, Gately M, Delespesse G. IL-12 induces the production of IFN-γ by neonatal human CD4 T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:1938–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wynn T A, Reynolds A, James S, Cheever A W, Caspar P, Hieny S, Jankovic D, Strand M, Sher A. IL-12 enhances vaccine-induced immunity to schistosomes by augmenting both humoral and cell-mediated immune responses against the parasite. J Immunol. 1996;157:4068–4078. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]