Abstract

The human L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; SLC7A5) is a membrane transporter of amino acids, thyroid hormones, and drugs such as the Parkinson’s disease drug levodopa (L-Dopa). LAT1 is found in the blood-brain barrier, testis, bone marrow, and placenta, and its dysregulation has been associated with various neurological diseases, such as autism and epilepsy, as well as cancer. In this study, we combine metainference molecular dynamics simulations, molecular docking, and experimental testing, to characterize LAT1-inhibitor interactions. We first conducted a series of molecular docking experiments to identify the most relevant interactions between LAT1’s substrate-binding site and ligands, including both inhibitors and substrates. We then performed metainference molecular dynamics simulations using cryoelectron microscopy structures in different conformations of LAT1 with the electron density map as a spatial restraint, to explore the inherent heterogeneity in the structures. We analyzed the LAT1 substrate-binding site to map important LAT1-ligand interactions as well as newly described druggable pockets. Finally, this analysis guided the discovery of previously unknown LAT1 ligands using virtual screening and cellular uptake experiments. Our results improve our understanding of LAT1-inhibitor recognition, providing a framework for rational design of future lead compounds targeting this key drug target.

Significance

LAT1 is a membrane transporter of amino acids, thyroid hormones, and therapeutic drugs that is primarily found in the blood-brain barrier and placenta, as well as in tumor cells of several cancer types. We combine metainference molecular dynamics simulations, molecular docking, and experimental testing to characterize LAT1-inhibitor interactions. Our computational analysis predicts S66, G67, F252, G255, Y259, and W405 are critical residues for inhibitor binding and druggable sub-pockets in the outward-occluded conformation that are ideal for LAT1 inhibitor discovery. Using virtual screening and functional testing, we discovered multiple LAT1 inhibitors with diverse scaffolds and binding modes. Our results improve our understanding of LAT1’s structure and function, providing a framework for development of future therapeutics targeting LAT1 and other solute carrier transporters.

Introduction

The L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1; SLC7A5) mediates the import of large neutral amino acids such as phenylalanine and tyrosine in a 1:1 exchange for intracellular amino acids (e.g., histidine) (1). LAT1 is a member of the amino acid, polyamine, and organocation superfamily, which includes Na+ independent secondary transporters and plays an important role in a broad range of biological processes (2). LAT1 is among the most abundant transporters in the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), with 100-fold greater expression levels in BBB endothelial cells relative to other tissues (3). LAT1 can also be found in the placenta (4), where it delivers essential neutral amino acids and thyroid hormones, making it a key protein involved in cell growth and development. For example, leucine is imported by LAT1 to activate the mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1, a known regulator of cell growth and metabolism (5,6).

Genetic variations of LAT1 have been associated with multiple diseases and disorders. LAT1 has recently been associated with epileptic seizures due to its role in negatively regulating the ion channel Kv1.2 (7). Additionally, rare mutations in coding regions of the SLC7A5 gene (A246V and P375L) have been associated with autism spectrum disorder (8). These mutations decrease the activation of the amino acid response pathway with a corresponding reduction in mRNA translation, thereby leading to an adverse outcome of neuronal activity, microcephaly, and other neurobehavioral problems related to autism spectrum disorder (8). LAT1 overexpression has been linked to disease in numerous cancer types (9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19), particularly in prostate (10), gastric (11), and pancreatic (12) cancers. This upregulation of LAT1 increases the activation of the mTOR pathway, leading to the hyperproliferation of cells in the immune system and cancer (19).

In addition, LAT1 is highly important pharmacologically. It transports drug (20,21,22,23,24) and prodrug (25,26,27,28,29) substrates, which are delivered specifically into cells or tissues expressing this transporter. For example, LAT1 mediates the transport of the CNS drugs gabapentin (20), levodopa (L-Dopa) (15,27), pregabalin (21), and melphalan (22) across the BBB. LAT1 is also an emerging therapeutic target for cancer, where LAT1 inhibition deprives tumor cells of nutrients that fuel cancer cell proliferation. For instance, the LAT1 inhibitor JPH-203 is currently under clinical investigation for treating patients with advanced biliary tract cancers (30). Another inhibitor of undisclosed structure (OKY 034) is also currently being evaluated in a phase I/IIa clinical trial for advanced pancreatic cancer patients (31). Furthermore, due to its increased expression of LAT1 in T cells, it can also be targeted to augment cancer immunotherapy treatment as well as for treating autoimmune diseases (32). Other LAT1 inhibitors that have been reported are KMH-233 (33) (a phenylalanine derivative with half maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) = 18 μM), 3-iodo-L-tyrosine (34) (a tyrosine derivative with IC50 = 7.9 μM), and meta-substituted phenylalanine derivatives (35,36) (IC50 = 5–10 μM) that contain large lipophilic moieties.

Despite its biological importance, our understanding of LAT1 substrate and inhibitor specificity is still lacking (37). We have previously developed structure-activity relationship (SAR) models that allowed us to predict whether compounds are more likely to be a substrate or an inhibitor, which is highly relevant to drug delivery applications (34,35,36,37,38,39,40). For example, we discovered that LAT1 is considerably more tolerant of structural changes to its ligands than was previously thought (34). LAT1 does not require a carboxylic acid to be present in the substrate (39), and substitution with various polar functional groups that could be used in linking amino acids to drug molecules is viable (35). In contrast, substitution with larger groups led to potent inhibitors (36).

LAT1 forms a heterodimer complex with type-II membrane glycoprotein 4F2 cell-surface antigen heavy chain (4F2hc; SLC3A2) (42). Although SLC3A2 does not play a specific role in transport, it aids in localization to the plasma membrane and improves the stability of transport by LAT1. Recently, two independent groups determined complex LAT1/4F2hc structures in both outward-occluded and inward-open conformations (43,44,45). These structures revealed that LAT1 has 12 transmembrane helices (TMs), with 10 core TMs that follow a LeuT-like fold as seen in other amino acid, polyamine, and organocation members, where the TMs are arranged in a 5 + 5 inverted repeats topology. The structures also confirmed the putative substrate-binding site and modes of substrate recognition proposed by homology models based on prokaryotic homologs (46). Like related transporters (47), LAT1 uses a gated-pore mechanism, adopting different conformations during transport. Structures of homologs of LAT1, including the arginine/agmatine antiporter (48,49) from Escherichia coli and amino acid, polyamine, and organocation transporter (50,51) from Geobacillus kaustophilus have revealed potential conformations, providing templates to characterize LAT1 in various stages of the transport cycle.

In this study, we used various computational and experimental approaches to improve our understanding of the structural basis for LAT1 interaction with inhibitors. We first performed molecular docking to determine the most relevant interactions between the LAT1 and its inhibitors. Next, we conducted metainference molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, which allowed for evaluating the inherent heterogeneity in the recently published LAT1 cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) structures and potential ligand-binding modes. The proposed specificity determinants were then tested by the prediction of putative LAT1 inhibitors and experimental testing of top-scoring hits using a cell-based assay. Finally, we discuss these results and how they can be used to describe mechanisms of ligand binding and transport by LAT1, as well as the relevance of our approach to study other SLC transporters.

Materials and methods

Molecular docking

Molecular docking was performed using Glide (52) from the Schrödinger suite. All ligands were docked to the recently solved cryo-EM structures of LAT1 (PDB: 6IRT (43), 7DSL (45)). These structures were prepared for docking with the Glide Protein Preparation under default parameters (53). The ligand-binding site was defined based on the coordinates of the respective ligand in each published structure. The receptor grid for docking was generated via the Glide Receptor Grid Generation panel. The small molecules used in molecular docking were prepared for docking using LigPrep of the Schrödinger suite using default parameters. The docking results were visualized via PyMOL (54).

Enrichment analysis

The enrichment analysis was performed based on docking calculations using Glide, as described above. Nine known substrate site-binding ligands of LAT1 (phenylalanine, BCH, JX-078, L-Dopa, tryptophan, histidine, gabapentin, tyrosine, and baclofen; Fig. S1), were selected from the literature, using available IC50 data and the ability to dock into the inward-open conformation as selection criteria. Then 635 decoys were generated with the DUD-E server (55) using these ligands. This set of 643 molecules was then screened against both inward-open (6IRT) and outward-occluded (7DSL) structures at the substrate-binding site for LAT1. The results were evaluated by calculating the area under the curve and logarithmic area under the curve (logAUC), representing the ability of the virtual screening to discriminate known ligands among the set of decoys (56,57). The corresponding plots (Fig. 1) show the percentage of known ligands correctly predicted (y axis) within the top-ranked subset of all database compounds (x axis on logarithmic scale).

Figure 1.

Ligand enrichment for LAT1 structures. Key binding site residues are shown as sticks where oxygen, nitrogen, and carbon atoms are represented in red, blue, and white (A) or white (B and C), respectively. Hydrogen bonds are displayed as a dashed black line. (A) Docking pose of BCH to LAT1 guided by enrichment. BCH is predicted to form hydrogen bonds with G65, S66, and G67, key residues for LAT1 amino acid recognition. (B) The logarithmic area under the curve (logAUC) derived from constrained docking at residue G67 (red line; logAUC = 43.15), compared with random selection of ligands from a set of ligands and decoys (dashed blue line). (C) Table showing logAUC values for constrained docking to selected residues of LAT1 substrate-binding site in the inward-open conformation. (D) Binding pose of JX-078 to LAT1 found in published outward-occluded structure. (E) LogAUC values of constrained docking to residue G67. (F) LogAUC values for constrained docking to selected residues of LAT1 substrate-binding site in the outward-occluded conformation.

Virtual ligand screening

We used Glide to virtually screen the ZINC20 (58) lead-like library (“in stock”) and Enamine amino acid library against the two LAT1 conformations. We then selected compounds that contained an amino acid group from the 1000 top-scoring compounds of the lead-like library screen and did the same for the Enamine screen, as it contained many amino acid derivatives. We prioritized compounds predicted to interact with the binding site through hydrogen bonding with important residues (Fig. 1) and removed compounds with an unlikely pose or strained conformation (59,60,61).

Pocket volume measurement

Pocket Volume Measurer 3 (POVME3 (62)) was used to calculate binding-site volumes. We used default parameters for ligand-defined inclusion region, using BCH (PDB: 6IRT) and JX-078 (PDB: 7DSL) as the reference ligands, respectively.

Metainference MD simulations

The coordinates of LAT1 (chain B) were extracted from the PDB structures 6IRT and 7DSL including the respective ligands (BCH, JX-078). CHIMERA (63) was used to select the cryo-EM density within 5 Å of the structure (64), which was then used as input of the metainference simulation of LAT1-ligand binding. The starting model was prepared using CHARMM-GUI (65,66). Ninety-two POPC lipids were added to the system along with 13,297 water molecules in a triclinic periodic box of volume equal to 726 nm3. Thirty-one potassium and 30 chloride ions were added to ensure charge neutrality and a salt concentration of 0.15 M. The CHARMM36m force field (67) was used for the protein, lipids, and ions; the CHARMM General Force Field and the TIP3P model were used for the ligand and water molecules, respectively. A 30-ns-long equilibration was performed using GROMACS (68) following the standard CHARMM-GUI protocol consisting of multiple consecutive simulations in the NVT and NPT ensembles. During these equilibration steps, harmonic restraints on the positions of the lipids, ligand, and protein atoms were gradually switched off.

In the metainference simulation, a Gaussian noise model with one error parameter for each voxel of the cryo-EM map was used. Sixteen replicas of the system were used, and their initial configurations were randomly selected from the last 10-ns-long step of the equilibration protocol. We calculated the shortest periodic distance to be 1.0746 nm at time 30.614 ns. There were no detected periodic boundary effects on the protein dynamics. The metainference run was conducted for a total aggregated time of 10.8 μs for 6IRT, 30 μs for the 7DSL, and 20.5 μs for 7DSK. All simulations were carried out using GROMACS 2020.1 and the ISDB module (69) of the open-source, community-developed PLUMED library (70) (GitHub ISDB branch; https://github.com/plumed/plumed2/tree/isdb). For the analysis, the initial frames of the trajectory of each replica, corresponding to 20% of the total simulation time, were considered as additional equilibration steps under the cryo-EM restraint and discarded. The remaining conformations from all replicas were merged and clustered using 1) the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) calculated on all the heavy atoms of the ligand and of the protein residues within 5 Å of the ligand in at least one member of the ensemble, and 2) the gromos algorithm (71) with a cutoff equal to 1.0, 1.5, and 2.0 Å. The system dimension for concatenated simulation was 7.10148, 7.10148, and 11.79250, and the shortest periodic distance was 1.0746 nm at time 30.6 ns.

Metainference MD simulation trajectory analysis

RMSD and root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) were calculated using the fast QCP algorithm (72) in MDAnalysis (73). RMSD was calculated between the initial state of the system (first frame of the trajectory) and the corresponding time point of the simulation. RMSF was calculated using the initial frame as the reference frame, with all frames aligned to the receptor backbone. The time average of the RMSD of each residue was then calculated. The LAT1-JX-078 interaction map was generated using ProLif (74).

Cell culture preparation of hLAT1 stable cell line

TREx HEK-hLAT1 (XenoPort, Santa Clara, CA) (36,75) is an inducible cell line that is under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter for LAT1 and a secondary tetracycline-inducible plasmid for 4F2hc (SLC3A2). Both LAT1 and 4F2hc are important components for uptake activity, as they form a heterodimer to promote native transport of their substrates (41). Doxycycline and sodium butyrate, a histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitor, are supplied in the cell media to promote expression of LAT1 and 4F2hc 24 h before experimentation occurs. The creation of HEK-hLAT1 stable cells has previously been described in further detail (37). Cell culture preparation requires that they are grown and maintained in DMEM with 100 units/mL penicillin, 100 units/mL streptomycin, 2 mM L-glutamine, 1 μg/mL Fungizone, 10% fetal bovine serum, and 3 μg/mL blasticidin. Cells were grown in a humidified incubator with 5% CO2 at a stable 37°C.

cis-Inhibition assay and IC50 computations

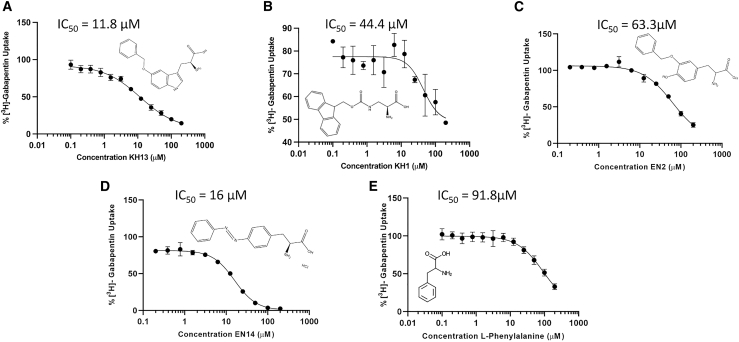

TREx HEK-hLAT1 cells were plated at a seeding density of 0.2 × 106 cells per well in poly-D-lysine-coated 24-well plates in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium as described above. Cells were grown to at least 90% confluency 48 h post seeding and, 24 h before the assay, the cells were induced with 2 mM sodium butyrate and 1 μg/mL doxycycline for proper LAT1 expression (41). On the day of the assay, cells are washed twice with warm sodium-free choline buffer (140 mM choline chloride, 2 mM potassium chloride, 1 mM magnesium chloride, 1 mM calcium chloride, 1 M Tris) and then incubated with the same solution for 10 min. We selected [3H]-gabapentin as a probe substrate due to its selectivity for LAT1 relative to other membrane transporters (20). For the cis-inhibition assay, the choline buffer was removed and replaced with radioactive uptake buffer (sodium-free choline buffer containing 6 nM [3H]-gabapentin) and each compound at a final concentration of 200 μM, and error bars represent ± SEM of 4 replicates. For the IC50 determinations, the choline buffer was replaced with a radioactive uptake buffer mixed with varying concentrations of each inhibitor ranging from 0.1 to 200 μM. For each assay, the uptake was performed in an incubator at 37°C for 3 min and the reaction was terminated by washing the cells twice with an ice-cold choline buffer. The cells were then lysed with 600 μL of lysis buffer (0.1 N NaOH, 0.1% SDS) at room temperature (RT) overnight or on a shaker for 1 h. Only 150 μL of lysis is used to measure intracellular radioactivity, which is determined by scintillation counting on an LS6500 scintillation counter (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA). IC50 determinations were calculated using GraphPad Prism version 9.3 (San Diego, CA) and percentage [3H]-gabapentin uptake was normalized relative to percentage inhibition by L-phenylalanine (89.0% ± 0.4%) at 200 μM (Fig. 6 E).

Figure 6.

IC50 values of new LAT1 inhibitors. 2D representation of (A) compound KH13, (B) compound KH1, (C) compound EN14, and (D) compound EN2 along with each representative dose-dependent curve shown as percentage [3H]-gabapentin uptake. For IC50 determination, varying concentrations of each compound were tested ranging from 0.1 to 200 μM, and error bars represent ± SEM of 4 replicates. GraphPad Prism version 9.3 was used to calculate IC50 values. The control (E) L-phenylalanine is shown with an IC50 of 91.8 μM.

Chemistry: General information

Flash chromatography purification was performed using a Teledyne ISCO flash chromatography system. Preparative high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed using a Gilson PLC 2020. The column was a Synergi 4μ Fusion-RP by Phenomenex, 150 × 21.2 mm. The following preparative HPLC method employed elution at 20-mL/min flow rate: A: gradient elution over 40 min of 5%–40% CH3CN with water, both of which contained 0.1% TFA. Liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) analysis was performed using an Agilent G6125 single quad ESI source and a 1260 Infinity HPLC system (G7112B Binary Pump and G7114A Dual λ Absorbance Detector). The column was a Synergi 4μ Fusion-RP by Phenomenex, 150 × 4.6 mm. The following LC-MS method was performed using a 1.0-mL/min flow rate: A: gradient elution over 10 min of 10%–80% CH3CN with water, both of which contained 0.1% formic acid. 1H NMR and 13C NMR were recorded on an Avance III HD Bruker instrument operating at 400 and 100 MHz, respectively.

Chemistry: Synthesis

Preparation of benzyloxy-substituted tryptophan analogs (AT182, AT183, AT184)

(±)-2-amino-3-(4-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid hydrochloride (AT182)

The title compound was synthesized in two steps using a modification of the procedure described by Blaser (76), as follows:

Step A: Preparation of (±)-acetamido-3-(4-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid

To a stirred mixture of acetic anhydride (1.3 mL, 13 mmol) in acetic acid (5 mL) was added 4-benzyloxyindole (1.0 g, 4.5 mmol) and L-serine (0.47 g, 4.5 mmol; note that the L isomer was used because it was on hand, but the D isomer or racemic serine would also give the same racemic product, as demonstrated by Blaser). The mixture was heated to 80°C and stirring continued overnight. The reaction was concentrated in vacuo at 80°C and carried forward into base-mediated acetyl deprotection without purification at this step.

Step B: Preparation of AT182

(±)-Acetamido-3-(4-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid from step A (0.50 g, 1.4 mmol) was heated with an aqueous 15% solution of NaOH (8.1 mL, 36 mmol) in a Teflon-capped glass pressure tube at 110°C for 2 days. After cooling to RT, concentrated HCl (3 mL) was carefully added and the resulting tan solids were filtered and rinsed with water (2 × 3 mL). Solids were heated with 1:1 CH3CN/water (20 mL) and the warm suspension was filtered to remove undissolved impurities. The mixture was chilled in a −10°C freezer and then the aqueous phase saturated with NaCl. The mixture was sonicated to dissolve the NaCl. The phases were separeated and the aqueous phase re-extracted with CH3CN (2 × 5 mL). The CH3CN phases were concentrated and the residue redissolved in 1:1 CH3CN/water (15 mL), and then syringe filtered through a 0.45-μm filter to remove smaller, undissolved particles. The crude product was prepared by preparative HPLC (method A). The product was converted to the HCl salt by adding 1 M aqueous HCl (2 mL) to the purified product and freeze drying to remove excess water and HCl. Yield was 81 mg (18%). Purity was >95% by LC-MS (254 nm, method A). 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 7.52 (d, J = 7 Hz, 2H), 7.38 (m, 2H), 7.32 (m, 1H), 7.04 (m, 3H), 6.64 (d, J = 7 Hz, 1H), 5.24 (s, 2H), 4.36 (dd, J = 4, 11 Hz, 1H), 3.79 (dd, J = 4, 14 Hz, 1H), 3.02 (dd, J = 11, 14 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 171.8, 154.4, 140.6, 138.6, 129.6, 129.0, 124.9, 123.9, 118.0, 108.4, 106.4, 101.8, 71.2, 55.2, 29.6. m/z (ESI-pos) M + 1 = 311.1.

(±)-2-amino-3-(6-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid hydrochloride (AT183)

This was prepared by the same two-step procedure as AT182, except for replacing 4-(benzyloxy)-1H-indole with 6-(benzyloxy)-1H-indole in step A. Purity was >95% by LC-MS (254 nm, method A). 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 7.49 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.44 (m, 2H), 7.35 (m, 2H), 7.29 (m, 1H), 7.10 (s, 1H), 6.99 (d, J = 2 Hz, 1H), 6.82 (dd, J = 2, 9 Hz, 1H), 5.08 (s, 2H), 4.22 (dd, J = 5, 8 Hz, 1H), 3.46 (dd, J = 5, 15 Hz, 1H), 3.29 (m, 1H, partially overlaps residual solvent peak). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 171.8, 156.9, 139.1, 139.0, 129.4, 128.7, 128.5, 124.5, 122.9, 119.7, 111.3, 107.9, 97.4, 71.5, 54.6, 27.7. m/z (ESI-pos) M + 1 = 311.1.

(±)-2-amino-3-(7-(benzyloxy)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid hydrochloride (AT184)

This was prepared by the same two-step procedure as AT182, except for replacing 4-(benzyloxy)-1H-indole with 7-(benzyloxy)-1H-indole in step A. Purity was >95% by LC-MS (254 nm, method A). 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO) δ 11.2 (s, 1H), 8.41 (br s, 2H), 7.55 (d, J = 8 Hz, 2H), 7.41 (m, 2H), 7.34, (m, 1H), 7.18, (m, 2H), 6.90 (m, 1H), 6.74 (d, J = 8 Hz, 1H), 5.25 (s, 2H), 4.07 (m, 1H), 3.27 (m, 2H). 13C NMR ((CD3)2SO) δ 170.6, 145.10, 145.05, 137.4, 128.8, 128.4, 127.7, 127.5, 126.5, 126.3, 124.7, 124.5, 119.1, 111.4, 107.3, 103.0, 69.1, 52.5, 26.1. m/z (ESI-pos) M + 1 = 311.1.

Preparation of benzylcarbamoyl-substituted tryptophan analogs (AT185, AT186)

(±)-2-Amino-3-(5-(benzylcarbamoyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid hydrochloride (AT185)

The title compound was prepared in five steps (A-E) as follows.

Step A: Preparation of (±)-3-(2-acetamido-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid

The compound was prepared from 1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid (3.0 g, 19 mmol) using the same procedure as in AT182, step A. Crude product was carried directly to the next step without purification.

Step B: Preparation of (±)-3-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid

With stirring, crude (±)-3-(2-acetamido-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid from step A was heated with 6M aqueous HCl (20 mL, 120 mmol) at 100°C overnight. It was concentrated in vacuo using CH3CN to azeotrope water (five cycles). Solids were dried under high vacuum overnight. Crude product was carried into step C without purification at this step.

Step C: Preparation of (±)-4'-((5-carboxy-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-5′-oxo-9L4-boraspiro[bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-9,2'-[1,3,2]oxazaborolidin]-3′-ium

Using a similar procedure as described by Venteicher (74), we protected crude (±)-3-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid from step B (1.0 g, 4.0 mmol) by stirring with pyridine (1.3 mL, 16 mmol) and 9-borabicyclo(3.3.1)nonane (9-BBN, 0.5 M in THF, 16 mL, 8.1 mmol) in DMF (5 mL) overnight at RT. The reaction mixture was partitioned between EtOAc (15 mL) and 1 M aqueous KHSO4 (35 mL). The phases were separated and the aqueous phase re-extracted with EtOAc (35 mL). Combined organic phases were washed with water (2 × 35 mL) and brine (50 mL), dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated in vacuo. Crude product was purified by trituration with hot EtOAc, followed by cooling to RT and filtration. Yield was 0.50 g (34%). 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO) δ 12.4 (br s, 1H), 11.3 (s, 1H), 8.27 (s, 1H), 7.74 (m, 1H), 7.43 (m, 2H), 6.52 (m, 1H), 5.68 (m, 1H), 3.84 (m, 1H), 3.29 (m, 1H), 3.17 (m, 1H), 1.30–1.81 (m, 12H), 0.45 (m, 2H).

Step D: Preparation of (±)-4'-((5-(benzylcarbamoyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-5′-oxo-9L4-boraspiro[bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-9,2'-[1,3,2]oxazaborolidin]-3′-ium

9-BBN-protected (±)-3-(2-amino-2-carboxyethyl)-1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid from step C (0.50 g, 1.4 mmol) was stirred overnight at RT with benzylamine (0.15 mL, 1.4 mmol), (i-Pr)2NEt (0.71 mL, 4.1 mmol), and 1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxide hexafluorophosphate (0.77 g, 2.0 mmol) in DMF (5 mL). The reaction mixture was partitioned between EtOAc (20 mL) and water (20 mL). The phases were separated and aqueous phase re-extracted with EtOAc (20 mL). Combined organic phases were washed with water (2 × 20 mL) and brine (20 mL), then dried (MgSO4), filtered, and concentrated. Crude product was purified by ISCO flash chromatography and eluted with a gradient of 30% EtOAc in hexanes to 100% EtOAc over 8 min. Yield was 0.40 g (64%). 1H NMR ((CD3)2SO) δ 11.2 (s, 1H), 8.91 (m, 1H), 8.23 (s, 1H), 8.02 (br s, 2H), 7.71 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.42 (m, 3H), 7.33 (m, 3H), 7.23 (m, 1H), 6.46 (m, 1H), 5.61 (m, 1H), 4.52 (m, 2H), 3.93 (m, 1H), 3.36 (m, 1H), 3.10 (dd, J = 9, 15 Hz, 1H), 1.29–1.81 (m, 12H), 0.48 (m, 2H).

Step E: Preparation of AT185

Using a modification of a method originally described by Poulie (77), the BBN protecting group was removed as follows: (±)-4'-((5-(benzylcarbamoyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)methyl)-5′-oxo-9L4-boraspiro[bicyclo[3.3.1]nonane-9,2'-[1,3,2]oxazaborolidin]-3′-ium from step D (0.40 g, 0.87 mmol) was stirred overnight at RT with TBAF (1 M in THF, 3.5 mL, 3.5 mmol) and THF (3 mL). Water (3 mL) was added and it was stirred for an additional 5 min. It was acidified with formic acid (1–2 mL) and concentrated in vacuo at 60°C to remove most of the THF. The resulting residue was dissolved in warmed 20% CH3CN in water containing 0.1% TFA (15 mL). The mixture was syringe filtered through a 0.45-μm filter to remove undissolved particles. The product was purified by two successive preparative HPLC runs (method A). The product was converted to the HCl salt by adding 1 M aqueous HCl (2 mL) to the purified product and freeze drying to remove excess water and HCl. Yield was 97 mg (30%). The purity was >95% by LC-MS (220 nm, method A). 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.26 (s, 1H), 7.69 (dd, J = 2, 9 Hz, 1H), 7.47 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (m, 2H), 7.33 (m, 3H), 7.24 (m, 1H), 4.62 (s, 2H), 4.33 (dd, J = 5, 8 Hz, 1H), 3.55 (dd, J = 5, 15 Hz, 1H), 3.41 (dd, J = 8, 15 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 171.6, 171.5, 140.4, 140.3, 129.5, 128.6, 128.1, 128.0, 127.5, 126.3, 122.1, 119.7, 113.6, 109.3, 54.4, 44.7, 27.4. m/z (ESI-pos) M + 1 = 338.2.

(±)-2-Amino-3-(6-(benzylcarbamoyl)-1H-indol-3-yl)propanoic acid hydrochloride (AT186)

The title compound was prepared according to the five-step procedure for AT185, except for replacing 1H-indole-5-carboxylic acid with 1H-indole-6-carboxylic acid in step A. The purity was >95% by LC-MS (220 nm, method A). 1H NMR (CD3OD) δ 8.00 (s, 1H), 7.69 (d, J = 9 Hz, 1H), 7.60 (dd, J = 1, 8 Hz, 1H), 7.41 (s, 1H), 7.37 (m, 2H), 7.32 (m, 2H), 7.23 (m, 1H), 4.60 (s, 2H), 4.28 (dd, J = 5, 7 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (dd, J = 5, 15 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (dd, J = 7, 15 Hz, 1H). 13C NMR (CD3OD) δ 171.5, 171.3, 140.4, 137.6, 131.0, 129.5, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5, 128.1, 119.3, 119.1, 112.7, 108.4, 54.5, 44.6, 27.3. m/z (ESI-pos) M + 1 = 338.2.

Results

Docking of known ligands to LAT1 structures

We applied molecular docking and ligand enrichment calculations to examine the pharmacological relevance of different conformations of LAT1’s binding site and ligands, as well as key interactions between them (Fig. 1). This analysis was also conducted to evaluate the optimal parameters for rational design of new LAT1 ligands. Specifically, we analyzed the ability of molecular docking and the cryo-EM structure to distinguish between known ligands of LAT1 and decoy compounds, which have similar physical properties to the known ligands but possess different topological properties, to reduce likelihood of binding (34). Compounds were docked against two different conformations of LAT1: an inward-open conformation bound to the inhibitor BCH (PDB: 6IRT) (43) and an outward-occluded conformation bound to the inhibitor JX-078 (PDB: 7DSL) (45).

We docked this set of known LAT1 ligands and decoy compounds against the inward-open conformation using default parameters and obtained a logAUC value of 13.88 (Fig. 1 C), which corresponds to a random selection of ligands. Conversely, similar docking parameters used for docking against the outward-occluded structure yielded a logAUC value of 76.06, suggesting that this conformation can capture LAT1-ligand complementarity and may yield productive virtual screening.

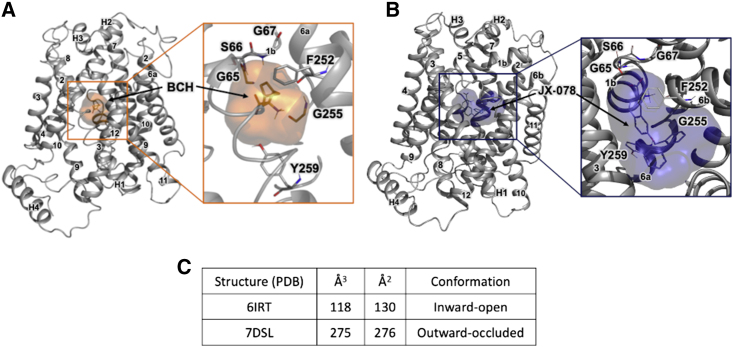

We then used different parameters enforcing different LAT1-ligand interactions to specific residues that have been shown (36,37,43,44,45) to be important for ligand binding and/or transport (i.e., S66, G67, F252, G255) (Fig. 1). Interestingly, for the inward-open conformation, constraining ligands to interact with F252, which is thought to serve as a gate for LAT1 ligands (38,43), yielded significantly improved enrichment scores, further validating the importance of this residue for LAT1 binding. For the outward-occluded structure, constrained docking to S66, G67, F252, and G255 yielded enrichment scores comparable with the scores derived from unconstrained docking. Notably, it is likely that the ability of the outward-occluded conformations to enrich for inhibitors is due to its increased size compared with the inward-open conformation (i.e., 275 Å3 versus 118 Å3, respectively; Fig. 2), which results from the movement of the sidechain of Y259. Taken together, these results suggest that the outward-occluded conformation better captures protein-ligand complementarity and is potentially more useful for the discovery of new ligands with structure-based virtual screening.

Figure 2.

LAT1-binding site in different conformations. Visualization of LAT1-binding site and accessible regions for the (A) inward-open (orange) and (B) outward-occluded conformation of LAT1 (blue). (C) Volume and surface area of the binding site in each conformation.

Dynamics of LAT1-binding site and inhibitor interaction

In parallel, we investigated the heterogeneity in the LAT1-inhibitor complex structure, using the metainference integrative approach (78). In metainference, the molecular mechanics force field used in standard MD simulations is augmented by spatial restraints that enforce the agreement of an ensemble of replicas of the system with the cryo-EM density map (79). Using a Bayesian inference framework, this approach accounts for the simultaneous presence of structural heterogeneity, data ensemble averaging, and variable level of noise in different areas of the experimental map. We performed metainference simulations on the outward-occluded structure of LAT1 bound to JX-078 (7DSL). In particular, we generated clusters of conformations of the protein-ligand complex and obtained a representative model for each cluster (Fig. 3 A). We assessed the stereochemical quality of each model using MolProbity (80), which considers the number of steric clashes, rotamer outliers, and percentage of backbone Ramachandran conformations outside favored regions. Notably, all models scored better (lower) than the cryo-EM structure, with model 1 scoring the best at 1.55 compared with the cryo-EM structure at 1.92 (Fig. S2). This suggests that the models generated from the simulation are of sufficient quality for further analysis.

Figure 3.

LAT1 structural heterogeneity. Ensemble conformations of LAT1 generated from outward-occluded metainference simulation are shown. (A) Superposition of six representative models (clusters) following ensemble metainference simulation of the outward-occluded state. The models display a mostly stable arrangement of the overall structure and ligand-binding site. (B) Superposition of the outward-occluded, JX-078-bound structure (PDB: 7DSL (gray)), and each labeled individual model (colored), focusing on the substrate-binding site.

We analyzed the differences and similarities among the models, focusing on the interactions between JX-078 and LAT1 (Fig. 3 B). The ligand showed some flexibility with RMSD changes of up to 5Å, particularly after 20 ns, suggesting the adoption of multiple conformations (Fig 4 C). Closer inspection of the representative models revealed that orientation of the amino and carboxy group of JX-078 remained consistent, making sustained hydrogen bonds with the same residues highlighted from our enrichment study (i.e., S66, G67, F252, G255), maintaining hydrogen bonding for over 90% of the simulation (Fig. S3). We noted that most of the variability seen with the RMSD analysis occurred at the hydrophobic tail of JX-078, which consistently binds deeper into the binding pocket (Fig. 3 B). Additionally, we observed that the hydrophobic tail of JX-078 explores different regions of the binding site, revealing two sub-pockets, C and D (Fig. 5 A). At sub-pocket D, JX-078-LAT1 interactions were stabilized by Y259, making π-stacking interactions with the biphenyl moiety (Fig. S3). Interestingly, we observed that the inhibitor showed some preference for sub-pocket C (Fig. 5 A), as seen in models 4, 5, and 6, with residue W405 playing a key role in inhibitor binding by making an additional π-stacking interaction with the inhibitor (Fig. S3). Most of the simulation displayed a binding pose targeting sub-pocket D, in the ensemble simulation, representing over 90% of all the conformations found (Fig. 3 B, models 1 and 6; Fig. S2). Additionally, we saw an increase in the size of the binding pocket of models 1–5, by as much as 33% (Fig. S2). We hypothesize that these sub-pockets and increase in pocket size can be exploited with rational ligand design from virtual screening and SAR studies.

Figure 4.

Quantitative analysis of binding site movements. (A) Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) analysis of metainference simulation focusing on the backbone α-carbon atoms of all residues. The x axis displays the duration of the simulation trajectory (in nanoseconds), and the y axis conveys the movement of atoms in angstroms compared with the initial frame of the trajectory. (B) Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis of individual residue sidechains. Binding site residues are broken down into four regions: I, II, II, and IV in yellow, green, purple, and red, respectively, with the indicators of helices above. The y axis represents the ensemble average of each residue sidechain (x axis). (C) RMSD analysis of JX-078’s atoms. (D) Fraction of contacts made between residues (I63, S65, S66, G67, F252, G255, Y259) in the LAT1 substrate-binding site and JX-078 throughout the simulation trajectory. (E) Binding site of 7DSL with each region (i.e., I, II, II, and IV) mapped onto the structure.

Figure 5.

Predicted binding mode of newly discovered LAT1 inhibitors. (A) Binding poses of JX-078 to LAT1 derived from metainference simulations using the cryo-EM structure (PDB: 7DSL). Predicted key residues from enrichment analysis (Fig. 1). The compound extends to druggable sub-pockets C and D. Docking pose of (B) KH-13 and (C) tryptophan, which is a known substrate of LAT1. (D) Docking pose of tryptophan analog AT183, which targets pocket C.

We also assessed the stability and movement of the LAT1-JX-078 structure throughout the simulation. We observed that the overall structure and binding site residues remained stable, which is reflected in the low RMSD of all backbone atoms throughout the simulation and particularly in the binding site residues (Fig. 4 A). Closer inspection of the individual residue sidechains of LAT1 by RMSF analysis revealed that most sidechain variability compared with the cryo-EM structure occurs away from the binding site, with movement less than 1 Å (Fig. 4 B). This analysis supports the notion that the size and shape of the LAT1-binding pocket in the outward-occluded conformation remains mostly stable, with most of the flexibility occurring at TM10. The inhibitor displayed some flexibility (Fig. 4 C), showing movement as great as 5 Å. Most of this flexibility stems from the hydrophobic tail of the inhibitor, which is captured by the representative models 1–6 (Fig. 3 B). Note that the stability of the ligand mirrors the increase in contacts between the residues: I63, S65, S66, G67, F252, G255, and Y259. We speculate that these residues are essential to JX-078 binding to LAT1. Although previous studies suggested that ATP and cholesterol play a synergistic role in modulating LAT1 allosterically (20,81) and may have an impact on the substrate-binding site, the current metainference analysis of the substrate binding is unlikely to be affected by these putative mechanisms.

Virtual screening and functional testing of novel compounds for LAT1

Next, guided by the metainference analysis, we computationally screened a library of purchasable compounds from the ZINC20 lead-like database (3.8 million compounds) and amino acid-like compounds from Enamine (8137 compounds), against the outward-occluded conformation. The top-scoring compounds from each screen were prioritized for further analysis (section “materials and methods”). Specifically, we prioritized compounds for experimental testing based on the following considerations:

-

1)

Compounds contain both carboxy and amino groups that make critical interactions with binding-site residues.

-

2)

Compounds are predicted to make hydrogen bonds with S66, G67, G255, and F255.

-

3)

Compounds have a hydrophobic tail that extends deeper into the binding site, preferably to sub-pocket C or D found from the metainference study (Fig. 5 A).

Overall, 23 compounds (Table S1) were initially selected for experimental testing using a cis-inhibition assay, which is based on an inhibitor’s capacity to reduce intracellular accumulation of the probe substrate [3H]-gabapentin using a stable TREx HEK-hLAT1 cell line (see section “materials and methods”). Eleven compounds were identified as LAT1 inhibitors by reducing cellular uptake by > 50% at inhibitor concentration of 200 μM (Table 1). The most potent compound in our study was KH13 (Fig. 5 B), which exhibited an IC50 value of 11.8 μM (Fig. 6 A), which was discovered in previous LAT1 inhibitor studies by Ecker and coworkers (82) and was also recently highlighted again by Altmann and colleagues (83), while this manuscript was in revision, at comparable levels of potency. KH13 is a benzyloxy-substituted tryptophan, and its predicted binding pose is nearly identical to that of tryptophan (Fig. 5 B and C). The benzyloxy group of KH13 interacts with the newly discovered sub-pocket C and W405 and likely contributes to its potency. We designed and tested analogs of KH13, three benzyloxy regioisomers and two benzyl amides (AT182-186), that were targeted to the same sub-pockets (e.g., AT183, Fig. 5 D). These analogs exhibited potency comparable with that of KH13 (Table 1). These results increased our confidence in the predicted binding mode of our initial inhibitors to sub-pocket C. Other new inhibitors included the phenylalanine analog EN14 (IC50 = 16 μM; Fig. 6 C) and tyrosine analog EN2 (IC50 = 63.3 μM; Fig. 6 D). EN14 contains a diazo linkage, and, like KH13, it places a hydrophobic phenyl ring into sub-pocket C and is also a potent inhibitor. Interestingly, the benzyloxy group in EN2 docks into sub-pocket D, and the decrease in potency relative to KH13 suggests this is a less optimal position for the benzyloxy group. Finally, KH1 (IC50 = 44.4 μM; Fig. 6 B) contains a bulky fluorenylmethoxycarbonyl (Fmoc) sidechain that interacts with both sub-pockets C and D. Taken together, these newly discovered LAT1 inhibitors represent diverse scaffolds and/or novel binding modes.

Table 1.

LAT1 Inhibitors

| Compound | Structure | Average Gabapentin Uptake (%) | IC50 (μM) | Sub-Pocket Target |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EN2 |  |

20.3 | 63.3 | D |

| EN5 |  |

16.4 | both | |

| EN9 |  |

1.5 | C | |

| EN14 |  |

2.6 | 16 | C |

| EN15 |  |

1.4 | both | |

| EN17 |  |

82.1 | C | |

| EN18 |  |

1.2 | D | |

| EN20 |  |

13.2 | both | |

| EN23 |  |

1.8 | both | |

| KH1 |  |

43.1 | 44.4 | both |

| KH13 |  |

6.8 | 11.8 | C |

| KH14 |  |

31.9 | C | |

| AT182 |  |

49.9 | C | |

| AT183 |  |

22.3 | D | |

| AT184 |  |

55.9 | D | |

| AT185 |  |

51.6 | C | |

| AT186 |  |

43.7 | D | |

| BCH |  |

12.5 | ||

| L-Phe |  |

22.2 | 91 | |

| DMSO |  |

100 |

Blank cells indicate no data available.

Results for cis-inhibition (percentage gabapentin uptake, n = 3), IC50 values, and sub-pocket compound targets. Compound represents the name of the compound. Structure corresponds to the 2D structure of the compound and its chemical formula. Percentage gabapentin uptake corresponds to the amount of intracellular accumulation of [3H]-gabapentin. Sub-pocket target corresponds to the sub-pocket the compound is predicted to bind, including sub-pocket C, D, or both.

Discussion

LAT1 is a physiologically important protein and a key drug target for a range of diseases and disorders. Despite significant improvement in our understanding of LAT1 structure and function over the past decade, the description of LAT1-ligand interactions at the molecular level is still inadequate. Structural description of LAT1 conformations and mode of binding with ligands is needed for understanding LAT1 transport, as well as for the development of novel small-molecule modulators of its function. The goal of this study was to characterize LAT1-inhibitor interactions by combining computational and experimental approaches. The following three key results emerge from this study.

Characterizing LAT1’s binding site and ligand binding

First, we identified key binding site residues and proposed the binding modes of known and newly discovered inhibitors. Ligand enrichment (Fig. 1) in combination with metainference analysis (Figs. 3 and 4) highlighted S66, G67, F252, and G255 as critical residues for inhibitor binding in agreement with previous studies (82,83,84). We also propose the importance of an additional two residues: Y259 and W405. The backbone atoms of S66 and G67 form hydrogen bonds with the JX-078 amino group, and those of F252 and G255 form hydrogen bonds with the inhibitor’s carboxy group (Figs. 1 and 3). Furthermore, analysis of cryo-EM structures of LAT1 in two different conformations (i.e., outward occluded and inward open) in complex with different inhibitors (i.e., BCH and JX-078, respectively) revealed that the interactions between the amino and carboxy moieties of the ligands and LAT1 remain mostly consistent, with only a subtle rearrangement of the backbone residues of the ligand-binding site (Fig. 3 A). Of note, the binding site in the outward-occluded structure is significantly larger (Fig. 2) and possesses potential sub-pockets that are not seen in the inward-open conformation (Figs. 3 and 5), in part due to the orientation of the Y259 sidechain (Fig. 2). Our metainference analysis revealed two potential druggable sub-pockets that the hydrophobic tail of JX-078 fits into (Figs. 3 and 5), with W405 playing a key role in sub-pocket C binding. We ruled out that these pockets could be an artifact of JX-078 having an alternative binding mode in the published cryo-EM structure by examining the map data (Fig. S4), which showed no unexplained density around the inhibitor. Overall, our results suggest that the outward-occluded structure is a more relevant conformation for rational drug design than the inward-open conformation.

Identifying unique LAT1 inhibitors

Second, we identified previously unknown pharmacophores of LAT1 inhibitors. Currently, there is a limited number of small-molecule tool compounds targeting LAT1, representing few chemical scaffolds (37,82,84). Structure-based virtual screening allows the exploration of novel scaffolds by predicting binding of large compound libraries with minimal bias. Although the newly experimentally validated inhibitors from the virtual screens, including those in this study, are not optimized, and are thus not sufficiently potent to be lead compounds, some of them possess chemical moieties that can serve as starting points for the exploration of unique chemical spaces. For example, KH14 contains a distinctive pyrrolidine-pyrazole moiety that offers opportunities to substitute with different groups off the pyrazole ring nitrogen, and KH1 shows that a carbamate moiety can be used to project a 9H-fluorene ring into both sub-pockets C and D. EN14 contains an uncommon aryl azo group, extends deep into sub-pocket C, and provides an opportunity for additional modification by replacing and/or functionalizing the phenyl ring.

Although other newly identified compounds are derived from known scaffolds, these compounds exhibited unique modes of binding. For example, substituted tryptophan KH13 and substituted tyrosine EN2 both extend deep into the previously uncharacterized sub-pockets C and D, respectively. Although extensive SAR work has been done on investigating phenylalanine (35,37,85) and tyrosine (35,43) derivatives, until recently (82,83), tryptophan had been largely overlooked as a starting point for inhibitor or prodrug design. Thus, this work provides a framework for developing future tryptophan analogs but also analogs of other proposed inhibitors found in this study (Table 1).

Demonstrating the utility of metainference MD simulations

Third, we demonstrated an application of an emerging integrative modeling approach to characterize the transporter binding site and rationally design small-molecule ligands. Cryo-EM is emerging as the primary method for structure determination of membrane proteins, including SLC transporters (84,85). However, cryo-EM structures are often not determined in a resolution sufficient for structure-based compound design (86). Further, this challenge is amplified by the inherent flexibility of membrane transporters, including LAT1 (87). Metainference can account for the heterogeneity in cryo-EM maps as a result of the intrinsic dynamics of these molecules, as well as the errors in the measurement (78,79). We have previously shown that metainference can identify pharmacologically relevant conformations of an unrelated amino acid transporter and guide the optimizations of inhibitors (88). Here, we apply metainference to identify putative sub-pockets in the binding site, as well as to estimate the biophysical features of the binding site such as flexibility and accessible volume for ligand binding. The metainference simulations enabled an improved prioritization of ligands predicted from virtual screening, in combination with visual analysis. Remarkably, metainference-generated representative models of the simulation exhibited more favorable stereochemical quality over the experimentally determined structure (Fig. S2), and were critical in guiding the identification of unique LAT1 inhibitors, mainly due to the revelation of sub-pockets C and D. As more structures of LAT1 and other SLCs are solved with cryo-EM, metainference and other computational approaches, such as the machine-learning-based approach AlphaFold2 (89,90), can be applied to identify novel ligands for effective therapy and study of human diseases.

Data availability

The GROMACS topology and input files as well as PLUMED input files are available on PLUMED-NEST (https://www.plumed-nest.org/) under accession ID plumID:22.018.

Scripts used for post metainference trajectory analysis are available at: https://github.com/schlessinger-lab/LAT1-metainference.

Author contributions

K.H., D.B.S., A.S., A.A.T., and M.B. conceptualized and designed the study. K.H. performed molecular docking and virtual screening, supervised by A.S. Metainference MD simulations were performed by K.H. and the results and analysis were reviewed and supervised by M.B. Compound design and synthesis were performed by A.A.T., J.B., and C.C. Experimental functional testing was performed by D.B.S. The manuscript was drafted by K.H. and A.S. A.A.T., M.B., D.B.S., J.B., and C.C. contributed to the writing of the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this work was provided by the following grants: R01 GM108911 (A.S.), T32 GM062754 (K.H.), and R15 NS099981 (A.A.T.)

This work was supported in part through the computational resources and staff expertise provided by Scientific Computing at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

M.B. acknowledges the support of the French Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR), under grant ANR-20-CE45-0002 (project EMMI).

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Editor: Philip Biggin.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.001.

Contributor Information

Massimiliano Bonomi, Email: massimiliano.bonomi@gmail.com.

Avner Schlessinger, Email: avner.schlessinger@mssm.edu.

Supporting material

Results for cis-inhibition (percentage gabapentin uptake, n = 3), IC50 values, and sub-pocket compound targets. Compound represents the name of the compound. Structure and formula correspond to the 2D structure of the compound and its chemical formula. Percentage gabapentin uptake corresponds to the amount of intracellular accumulation of [3H]-gabapentin. Sub-pocket target corresponds to the sub-pocket the compound is predicted to bind, including sub-pocket C, D, or both. Compound library corresponds to the small-molecule library where each candidate inhibitor was obtained. Blank cells indicate no data are available.

References

- 1.Kanai Y., Segawa H., et al. Endou H. Expression cloning and characterization of a transporter for large neutral amino acids activated by the heavy chain of 4F2 antigen (CD98) J. Biol. Chem. 1998;273:23629–23632. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.37.23629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong F.H., Chen J.S., et al. Saier M.H., Jr. The amino acid-polyamine-organocation superfamily. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2012;22:105–113. doi: 10.1159/000338542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ohtsuki S., Yamaguchi H., et al. Terasaki T. Reduction of L-type amino acid transporter 1 mRNA expression in brain capillaries in a mouse model of Parkinson's disease. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2010;33:1250–1252. doi: 10.1248/bpb.33.1250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boado R.J., Li J.Y., et al. Pardridge W.M. Selective expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter at the blood-brain barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1999;96:12079–12084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nicklin P., Bergman P., et al. Murphy L.O. Bidirectional transport of amino acids regulates mTOR and autophagy. Cell. 2009;136:521–534. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagamori S., Wiriyasermkul P., et al. Kanai Y. Structure-activity relations of leucine derivatives reveal critical moieties for cellular uptake and activation of mTORC1-mediated signaling. Amino Acids. 2016;48:1045–1058. doi: 10.1007/s00726-015-2158-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baronas V.A., Yang R.Y., et al. Kurata H.T. Slc7a5 regulates Kv1.2 channels and modifies functional outcomes of epilepsy-linked channel mutations. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:4417–4515. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-06859-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tărlungeanu D.C., Deliu E., et al. Novarino G. Impaired amino acid transport at the blood brain barrier is a cause of autism spectrum disorder. Cell. 2016;167:1481–1494.e18. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yanagida O., Kanai Y., et al. Endou H. Human L- type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1): characterization of function and expression in tumor cell lines. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1514:291–302. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00384-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagisawa N., Satoh T., et al. Murakumo Y. L-amino acid transporter 1 may be a prognostic marker for local progression of prostatic cancer under expectant management. Cancer Biomark. 2015;15:365–374. doi: 10.3233/CBM-150486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ichinoe M., Mikami T., et al. Okayasu I. High expression of L-type amino-acid transporter 1 (LAT1) in gastric carcinomas: comparison with non-cancerous lesions. Pathol. Int. 2011;61:281–289. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2011.02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ebara T., Kaira K., et al. Nakano T. L-type amino-acid transporter 1 expression predicts the response to preoperative hyperthermo-chemoradiotherapy for advanced rectal cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4223–4227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kobayashi H., Ishii Y., Takayama T. Expression of L-type amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) in esophageal carcinoma. J. Surg. Oncol. 2005;90:233–238. doi: 10.1002/jso.20257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takeuchi K., Ogata S., et al. Kawai T. LAT1 expression in non-small-cell lung carcinomas: analyses by semiquantitative reverse transcription-PCR (237 cases) and immunohistochemistry (295 cases) Lung Cancer. 2010;68:58–65. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soares-da-Silva P., Serrão M.P. High- and low-affinity transport of L-leucine and L-DOPA by the hetero amino acid exchangers LAT1 and LAT2 in LLC-PK1 renal cells. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2004;287:F252–F261. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00030.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Imai H., Kaira K., et al. Mori M. L- type amino acid transporter 1 expression is a prognostic marker in patients with surgically resected stage I non- small cell lung cancer. Histopathology. 2009;54:804–813. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.2009.03300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yanagisawa N., Hana K., et al. Murakumo Y. High expression of L- type amino acid transporter 1 as a prognostic marker in bile duct adenocarcinomas. Cancer Med. 2014;3:1246–1255. doi: 10.1002/cam4.272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hayashi K., Anzai N. Novel therapeutic approaches targeting L-type amino acid transporters for cancer treatment. World J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2017;9:21–29. doi: 10.4251/wjgo.v9.i1.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Häfliger P., Graff J., et al. Charles R.-P. The LAT1 inhibitor JPH203 reduces growth of thyroid carcinoma in a fully immunocompetent mouse model. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018;37:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s13046-018-0907-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dickens D., Webb S.D., et al. Pirmohamed M. Transport of gabapentin by LAT1 (SLC7A5) Biochem. Pharmacol. 2013;85:1672–1683. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi Y., Nishimura T., et al. Tomi M. Transport of pregabalin via L-type amino acid transporter 1 (SLC7A5) in human brain capillary endothelial cell line. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2018;35:246–249. doi: 10.1007/s11095-018-2532-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cornford E.M., Young D., et al. Pardridge W.M. Melphalan penetration of the blood-brain barrier via the neutral amino acid transporter in tumor-bearing brains. Cancer Res. 1992;52:138–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun D.W., Lee S.A., et al. Kim D.K. JPH203, an L-type amino acid transporter 1–selective compound, induces apoptosis of YD-38 human oral cancer cells. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2014;124:208–217. doi: 10.1254/jphs.13154FP. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Imai H., Kaira K., et al. Kanai Y. Inhibition of L-type amino acid transporter 1 has antitumor activity in non-small cell lung cancer. Anticancer Res. 2010;30:4819–4828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gynther M., Laine K., et al. Rautio J. Large neutral amino acid transporter enables brain drug delivery via prodrugs. J. Med. Chem. 2008;51:932–936. doi: 10.1021/jm701175d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Killian D.M., Hermeling S., Chikhale P.J. Targeting the cerebrovascular large neutral amino acid transporter (LAT1) isoform using a novel disulfide-based brain drug delivery system. Drug Deliv. 2007;14:25–31. doi: 10.1080/10717540600559510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peura L., Malmioja K., et al. Laine K. Design, synthesis and brain uptake of LAT1-targeted amino acid prodrugs of dopamine. Pharm. Res. (N. Y.) 2013;30:2523–2537. doi: 10.1007/s11095-012-0966-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puris E., Gynther M., et al. Huttunen K.M. L-type amino acid transporter 1 utilizing prodrugs: how to achieve effective brain delivery and low systemic exposure of drugs. J. Control. Release. 2017;261:93–104. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park K. Insight into brain-targeted drug delivery via LAT1-utilizing prodrugs. J. Control. Release. 2017;261:368. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2017.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Okano N., Naruge D., et al. Furuse J. First-in-human phase I study of JPH203, an L-type amino acid transporter 1 inhibitor, in patients with advanced solid tumors. Invest. New Drugs. 2020;38:1495–1506. doi: 10.1007/s10637-020-00924-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UMIN-CTR Clinical Trial (Japan) 2021. Phase I/IIa Trial of R-OKY-034F for Pancreatic Cancer Patients.https://center6.umin.ac.jp/cgi-open-bin/ctr_e/ctr_view.cgi?recptno=R000041465 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hayashi K., Anzai N. L-type amino acid transporter 1 as a target for inflammatory disease and cancer immunotherapy. J. Pharmacol. Sci. 2022;148:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jphs.2021.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huttunen K.M., Huttunen J., et al. Spicer J.A. L-Type amino acid transporter 1 (lat1)-mediated targeted delivery of perforin inhibitors. Int. J. Pharm. 2016;498:205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2015.12.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geier E.G., Schlessinger A., et al. Giacomini K.M. Structure-based ligand discovery for the large-neutral amino acid transporter 1, LAT-1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:5480–5485. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1218165110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Augustyn E., Finke K., et al. Thomas A.A. LAT-1 activity of meta-substituted phenylalanine and tyrosine analogs. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:2616–2621. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.04.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venteicher B., Merklin K., et al. Thomas A.A. The effects of prodrug size and a carbonyl linker on l-type Amino acid transporter 1-targeted cellular and brain uptake. ChemMedChem. 2021;16:869–880. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chien H.C., Colas C., et al. Thomas A.A. Reevaluating the substrate specificity of the L-type Amino acid transporter (LAT1) J. Med. Chem. 2018;61:7358–7373. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Napolitano L., Galluccio M., et al. Indiveri C. Novel insights into the transport mechanism of the human amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5). Probing critical residues for substrate translocation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Gen. Subj. 2017;1861:727–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zur A.A., Chien H.C., et al. Thomas A.A. LAT1 activity of carboxylic acid bioisosteres: evaluation of hydroxamic acids as substrates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2016;26:5000–5006. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2016.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Napolitano L., Scalise M., et al. Indiveri C. Potent inhibitors of human LAT1 (SLC7A5) transporter based on dithiazole and dithiazine compounds for development of anticancer drugs. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2017;143:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2017.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fotiadis D., Kanai Y., Palacín M. The SLC3 and SLC7 families of amino acid transporters. Mol. Aspects Med. 2013;34:139–158. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2012.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosell A., Meury M., et al. Fotiadis D. Structural bases for the interaction and stabilization of the human amino acid transporter LAT2 with its ancillary protein 4F2hc. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2014;111:2966–2971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323779111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yan R., Zhao X., et al. Zhou Q. Structure of the human LAT1-4F2hc heteromeric amino acid transporter complex. Nature. 2019;568:127–130. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1011-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee Y., Wiriyasermkul P., et al. Nureki O. Cryo-EM structure of the human L-type amino acid transporter 1 in complex with glycoprotein CD98hc. bioRxiv. 2019 doi: 10.1101/577551. Preprint at. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yan R., Li Y., et al. Zhou Q. Mechanism of substrate transport and inhibition of the human LAT1-4F2hc amino acid transporter. Cell Discov. 2021;7:16. doi: 10.1038/s41421-021-00247-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Colas C., Ung P.M.U., Schlessinger A. SLC transporters: structure, function, and drug discovery. Medchemcomm. 2016;7:1069–1081. doi: 10.1039/C6MD00005C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hediger M.A., Romero M.F., et al. Bruford E.A. The ABCs of solute carriers: physiological, pathological and therapeutic implications of human membrane transport proteinsIntroduction. Pflugers Arch. 2004;447:465–468. doi: 10.1007/s00424-003-1192-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ilgü H., Jeckelmann J.M., et al. Fotiadis D. Effects of mutations and ligands on the thermostability of the l-arginine/agmatine antiporter AdiC and deduced insights into ligand-binding of human l-type Amino acid transporters. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:E918. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ilgü H., Jeckelmann J.M., et al. Fotiadis D. Insights into the molecular basis for substrate binding and specificity of the wild-type L-arginine/agmatine antiporter AdiC. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2016;113:10358–10363. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1605442113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaffer P.L., Goehring A., et al. Gouaux E. Structure and mechanism of a Na+-independent amino acid transporter. Science. 2009;325:1010–1014. doi: 10.1126/science.1176088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Singh N., Ecker G.F. Insights into the structure, function, and ligand discovery of the large neutral amino acid transporter 1, LAT1. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;19:1278. doi: 10.3390/ijms19051278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Friesner R.A., Murphy R.B., et al. Mainz D.T. Extra precision glide: docking and scoring incorporating a model of hydrophobic enclosure for protein-ligand complexes. J. Med. Chem. 2006;49:6177–6196. doi: 10.1021/jm051256o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sastry G.M., Adzhigirey M., et al. Sherman W. Protein and ligand preparation: parameters, protocols, and influence on virtual screening enrichments. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2013;27:221–234. doi: 10.1007/s10822-013-9644-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schrödinger, LLC, The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5.0, Schrödinger, LLC.

- 55.Mysinger M.M., Carchia M., et al. Shoichet B.K. Directory of useful decoys, enhanced (DUD-E): better ligands and decoys for better benchmarking. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:6582–6594. doi: 10.1021/jm300687e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schlessinger A., Geier E., et al. Sali A. Structure-based discovery of prescription drugs that interact with the norepinephrine transporter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:15810–15815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1106030108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Evers A., Gohlke H., Klebe G. Ligand-supported homology modeling of protein binding-sites using knowledge-based potentials. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;334:327–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Irwin J.J., Tang K.G., et al. Sayle R.A. ZINC20—a free ultralarge-scale chemical database for ligand discovery. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020;60:6065–6073. doi: 10.1021/acs.jcim.0c00675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shoichet B.K. Virtual screening of chemical libraries. Nature. 2004;432:862–865. doi: 10.1038/nature03197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Carlsson J., Coleman R.G., et al. Shoichet B.K. Ligand discovery from a dopamine D3 receptor homology model and crystal structure. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2011;7:769–778. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ung P.M.U., Song W., et al. Schlessinger A. Inhibitor discovery for the human GLUT1 from homology modeling and virtual screening. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016;11:1908–1916. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wagner J.R., Sørensen J., et al. Amaro R.E. Povme 3.0: software for mapping binding pocket flexibility. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2017;13:4584–4592. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.7b00500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pettersen E.F., Goddard T.D., et al. Ferrin T.E. UCSF chimera - a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 2004;25:1605–1612. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goddard T.D., Huang C.C., Ferrin T.E. Visualizing density maps with UCSF Chimera. J. Struct. Biol. 2007;157:281–287. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jo S., Kim T., Iyer V.G., Im W. A web-based graphical user interface for CHARMM. J. Comput. Chem. 2008;29:1859–1865. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Brooks B.R., Brooks C.L., 3rd, et al. Karplus M. CHARMM: the biomolecular simulation program. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:1545–1614. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Huang J., Rauscher S., et al. MacKerell A.D., Jr. CHARMM36m: an improved force field for folded and intrinsically disordered proteins. Nat. Methods. 2017;14:71–73. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., et al. Lindahl E. High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1-2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Bonomi M., Camilloni C. Integrative structural and dynamical biology with PLUMED-ISDB. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:3999–4000. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bonomi M., Bussi G., et al. White A. Promoting transparency and reproducibility in enhanced molecular simulations. Nat. Methods. 2019;16:670–673. doi: 10.1038/s41592-019-0506-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Daura X., Gademann K., et al. Mark A.E. Peptide folding: when simulation meets experiment. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:236–240. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Theobald D.L. Rapid calculation of RMSDs using a quaternion-based characteristic polynomial. Acta Crystallogr. A. 2005;61:478–480. doi: 10.1107/S0108767305015266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gowers R.J., Linke M., et al. Beckstein O. In: Proceedings of the 15th Python in Science Conference. Benthall S., Rostrup S., editors. SciPy; 2019. MDAnalysis: a Python package for the rapid analysis of molecular dynamics simulations; pp. 98–105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bouysset C., Fiorucci S. A library to encode molecular interactions as fingerprints. J. Cheminform. 2021;13:72. doi: 10.1186/s13321-021-00548-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hall C., Wolfe H., et al. Thomas A.A. l-Type amino acid transporter 1 activity of 1, 2, 3-triazolyl analogs of l-histidine and l-tryptophan. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2019;29:2254–2258. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2019.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Blaser G., Sanderson J.M., et al. Howard J.A. The facile synthesis of a series of tryptophan derivatives. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:2795–2798. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Poulie C.B.M., Bunch L. Tetrabutylammonium fluoride as a mild and versatile reagent for cleaving boroxazolidones to their corresponding free α-amino acids. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017;2017:1475–1478. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bonomi M., Camilloni C., et al. Vendruscolo M. Metainference: a Bayesian inference method for heterogeneous systems. Sci. Adv. 2016;2 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1501177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Bonomi M., Pellarin R., Vendruscolo M. Simultaneous determination of protein structure and dynamics using cryo-electron microscopy. Biophys. J. 2018;114:1604–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2018.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Williams C.J., Headd J.J., et al. Richardson D.C. MolProbity: more and better reference data for improved all-atom structure validation. Protein Sci. 2018;27:293–315. doi: 10.1002/pro.3330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Cosco J., Scalise M., et al. Indiveri C. ATP modulates SLC7A5 (LAT1) synergistically with cholesterol. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:16738–16815. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-73757-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Singh N., Scalise M., et al. Ecker G.F. Discovery of potent inhibitors for the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) by structure-based methods. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018;20:27. doi: 10.3390/ijms20010027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Graff J., Müller J., et al. Altmann K.H. The evaluation of L-tryptophan derivatives as inhibitors of the LType Amino acid transporter LAT1 (SLC7A5) ChemMedChem. 2022;17 doi: 10.1002/cmdc.202200308. e202200308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Singh N., Villoutreix B.O., Ecker G.F. Rigorous sampling of docking poses unveils binding hypothesis for the halogenated ligands of L-type amino acid Transporter 1 (LAT1) Sci. Rep. 2019;9:15061–15120. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-51455-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ylikangas H., Peura L., et al. Rautio J. Structure-activity relationship study of compounds binding to large amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1) based on pharmacophore modeling and in situ rat brain perfusion. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013;48:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.ejps.2012.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bai X.C., McMullan G., Scheres S.H.W. How cryo-EM is revolutionizing structural biology. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2015;40:49–57. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2014.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Choy B.C., Cater R.J., et al. Pryor E.E., Jr. A 10-year meta-analysis of membrane protein structural biology: detergents, membrane mimetics, and structure determination techniques. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. Biomembr. 2021;1863 doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2020.183533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Garibsingh R.A.A., Ndaru E., et al. Schlessinger A. Rational design of ASCT2 inhibitors using an integrated experimental-computational approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2104093118. e2104093118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Del Alamo D., Sala D., et al. Meiler J. Sampling alternative conformational states of transporters and receptors with AlphaFold2. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.75751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Schlessinger A., Bonomi M. Artificial Intelligence: exploring the conformational diversity of proteins. Elife. 2022;11 doi: 10.7554/eLife.78549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Results for cis-inhibition (percentage gabapentin uptake, n = 3), IC50 values, and sub-pocket compound targets. Compound represents the name of the compound. Structure and formula correspond to the 2D structure of the compound and its chemical formula. Percentage gabapentin uptake corresponds to the amount of intracellular accumulation of [3H]-gabapentin. Sub-pocket target corresponds to the sub-pocket the compound is predicted to bind, including sub-pocket C, D, or both. Compound library corresponds to the small-molecule library where each candidate inhibitor was obtained. Blank cells indicate no data are available.

Data Availability Statement

The GROMACS topology and input files as well as PLUMED input files are available on PLUMED-NEST (https://www.plumed-nest.org/) under accession ID plumID:22.018.

Scripts used for post metainference trajectory analysis are available at: https://github.com/schlessinger-lab/LAT1-metainference.