Abstract

Proteosynthesis on ribosomes is regulated at many levels. Conformational changes of the ribosome, possibly induced by external factors, may transfer over large distances and contribute to the regulation. The molecular principles of this long-distance allostery within the ribosome remain poorly understood. Here, we use structural analysis and atomistic molecular dynamics simulations to investigate peptide deformylase (PDF), an enzyme that binds to the ribosome surface near the ribosomal protein uL22 during translation and chemically modifies the emerging nascent peptide. Our simulations of the entire ribosome-PDF complex reveal that the PDF undergoes a swaying motion on the ribosome surface at the submicrosecond timescale. We show that the PDF affects the conformational dynamics of parts of the ribosome over distances of more than 5 nm. Using a supervised-learning algorithm, we demonstrate that the exit tunnel is influenced by the presence or absence of PDF. Our findings suggest a possible effect of the PDF on the nascent peptide translocation through the ribosome exit tunnel.

Significance

All proteins in organisms are synthesized on biomachines called ribosomes. The ribosome is a hub for various biomolecules, which act together in a concerted manner. The complexity of proteosynthesis requires tight regulation at multiple levels. For instance, various parts of the ribosome need to be precisely coordinated, but how the coordination is achieved at the molecular level remains unclear. We use computer simulations of over 2 million atoms to study a signal transduction through the ribosome. We focus on a signal triggered by a protein that binds to the ribosome surface. Using a machine-learning algorithm, we identify ribosome motions that are coupled to the binding event. We show how the signal reaches the ribosome interior and suggest possible physiological consequences.

Introduction

During translation, the amino acids are delivered on tRNAs to the peptidyl transferase center (PTC) deep in the large ribosomal subunit, where they are added one by one to the elongating nascent chain (NC). A 10-nm-long tunnel accommodates the NC before it exits on the ribosome surface into the cytosol. The tunnel is mostly composed of rRNA, but several ribosomal proteins contribute to the tunnel walls as well. In bacteria, the loop extensions of uL4 and uL22 create a tunnel constriction. Closer to the tunnel exit, proteins uL23 and uL24 may affect the cotranslational folding of small protein domains (1).

Altogether, the tunnel walls form an active environment (2). Some NC sequences specifically interact with the walls or low-molecular factors in the exit tunnel. Often, these interactions have profound physiological consequences. For instance, translational stalling caused by the SecM peptide affects expression of a downstream gene (3) and regulates protein transmembrane export. The TnaC sequence interacts with free tryptophan and regulates its catabolism (4,5). Erythromycin and other macrolide antibiotics stall the ribosome and, through interactions with certain NCs, they regulate the expression of macrolide-resistance genes (6,7). The exit tunnel may also induce or facilitate folding of secondary structure motives (8) or small protein domains (9).

Several studies have reported signal transfer throughout the tunnel walls. The translational arrest caused by SecM involves an allosteric signaling from the constriction site through the rRNA nucleotide A2062 to the PTC (10,11). Likewise, another arresting peptide—VemP—switches off the PTC through a series of NCwall and NCNC interactions (8,12). In the presence of the ErmBL peptide, the binding of erythromycin was proposed to induce an allosteric change in rRNA nucleotides U2504–U2506 that modulates the PTC and contributes to the stalling (6). A number of potential allosteric sites have been recently reviewed in the Thermus thermophilus and Escherichia coli ribosomes (13).

The ribosome surface contains binding sites for protein-biogenesis translation factors like the trigger factor, signal recognition particle (SRP), or enzymes ensuring the NC modifications (14). A question arises of whether the information about surface status spreads deeper into the ribosome interior or, vice versa, the functional state of the ribosome or NC presence affects the recruitment of translation factors.

Indeed, an allosteric signal has been proposed to modulate SRP-mediated membrane targeting on the bacterial ribosome. The SRP binding affinity to the ribosomal protein uL23 was about 100 times higher when a short NC was present in the tunnel compared with a vacant ribosome (15). Strikingly, no sequence effect was observed, suggesting a universal conformational change of uL23. A coupling between a loop of uL23 and exit-tunnel nucleotides observed in coarse-grained molecular dynamics (MD) simulations was proposed as a possible mechanism of allosteric signal transfer (13).

The constriction site proteins uL4 and uL22 are highly conserved across all three domains of life. uL4 and uL22 were initially postulated as a discrimination gate (16), but this idea has not been verified. Still, due to a number of charged residues and its vicinity to the PTC, the constriction site likely interacts with many NCs (17).

The globular part of uL22 is exposed to the ribosome surface and contributes to the binding site of the peptide deformylase (PDF). PDF removes the formyl group from the N-terminal formylmethionine and initiates cotranslational maturation of NCs. PDF is essential for eubacteria (18); therefore, it was proposed as a potential drug target for antibiotics (19). A PDF binder actinonin and its analogs were also identified as potential anticancer agents (20) targeting mitochondrial PDF.

The PDF class I present in E. coli binds to the ribosome surface through its C-terminal α-helix (21). The binding interface was described by cryoelectron microscopy (cryo-EM) at 3.7 Å resolution using a model 16-residue peptide from the PDF C-terminus. The full PDF was studied by cryo-EM at lower resolutions (10–15 Å) (22), and it was shown that PDF can interfere with other protein biogenesis factors. The effect of PDF on the ribosome structure and dynamics has not been the center of focus.

Here, we study the interaction of the complete PDF with the ribosome and test the anticipated allostery between the ribosome surface and its interior triggered by the PDF binding. We use all-atom MD simulations, which have proven useful in studying conformational dynamics of the ribosome (23). We simulate the entire E. coli ribosome in explicit water to compare dynamics of the ribosome in the presence and absence of PDF. We apply a classification supervised-learning algorithm to predict the presence or absence from the conformations of various ribosome parts. Our results suggest that the PDF is highly flexible when bound to the ribosome and that the tunnel walls are modulated by the PDF.

Materials and methods

Simulated systems

The initial structural model of the ribosome-PDF complex was derived from the cryo-EM structure of the E. coli ribosome (PDB: 5AFI (24), average resolution of 2.9 Å). The model is one of the most complete for E. coli and includes noncanonical rRNA residues and flexible regions of bL9 and bL31. The PDF C-terminal helix was added from the available ribosome-helix complex (PDB: 4V5B (21), average resolution of 3.7 Å) by superimposing the large ribosomal subunits. Finally, the PDF was completed using an X-ray structure of an E. coli PDF-ligand complex (PDB: 2AI8 (25), average resolution of 1.7 Å). The ligand was removed, and the C-terminal helices were superimposed. Apart from the ribosome-PDF complex (PDF+), we also simulated the bare ribosome (PDF–).

Each model was placed in a rhombic dodecahedron periodic box of water ensuring a minimal distance of 0.9 nm between the solute and box faces. Structural Mg2+ ions were used as found in the cryo-EM ribosome model (PDB: 5AFI), and the catalytic Ni2+ ion was used as in the X-ray (PDB: 2AI8). The box was neutralized by randomly replacing a sufficient number of water molecules with K+ ions. To mimic physiological conditions, excess amounts of MgCl2 and KCl were added in order to reach concentrations of 10 and 100 mmol dm−3, respectively.

We used the Amber family of force fields, namely ff12SB (26) for proteins, ff99 with bsc0 and corrections for canonical RNA nucleotides (27,28,29), and Aduri et al. parameters for noncanonical nucleotides (30). The extended simple point charge water model SPC/E (31), which yields a more realistic description of bulk water in terms of diffusivity and dielectric constant than another popular 3-site model, TIP3P, was used together with Joung and Cheatham ion parameters (32). The force field choice for ribosome simulations is not trivial, and alternative options certainly exist. Here, we followed a strategy that proved reliable in previous simulation studies of the bacterial ribosome with respect to structural and/or biochemical experiments (6,12,33,34). The catalytic Ni2+ ion of PDF was kept in the X-ray conformation using harmonic distance restraints to the four nearest interacting residues (Gln50, Cys90, His132, and His136) using a force constant of 10,000 kJ mol−1 nm−2.

MD simulations

Each system was equilibrated in a series of short simulations. First, the energy of the solvent was minimized in 50,000 steps using the steepest-descent algorithm, keeping all solute atoms restrained by a harmonic potential with a force constant of 1,000 kJ mol−1 nm−2. Second, the solvent was heated over the course of a 500-ps MD simulation to 300 K using the v-rescale thermostat (35), while the solute was kept at 10 K and position restrained. The initial velocities were selected randomly from the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution at 10 K. The pressure was equilibrated to 1 bar in a 2-ns-long MD simulation using the Berendsen barostat (36). The position restraints were gradually released, and the solute was heated to 300 K during a 10-ns simulation. Finally, the production simulations were carried out at a constant temperature of 300 K and a pressure of 1 bar using the v-rescale thermostat and the Parrinello-Rahman barostat (37). For each system, we generated four independent trajectories, 1,040 ns each, differing in the initial velocities. For the analyses, the trajectory frames were saved every 200 ps.

In all simulations, the leap-frog algorithm was used to integrate Newton’s equations of motion. All bond lengths were constrained by P-LINCS (38) of expansion order of six, and the hydrogen atoms were treated as virtual sites (39). This allowed for a time step of 4 fs for the production runs, as previously validated in an MD simulation of lysozyme in extended simple point charge model water (40) (see Fig. S1 for a validation of the time step on a small model RNA system). The long-range electrostatic interactions were treated by the particle-mesh Ewald algorithm (41) with the direct-space cutoff of 1 nm, an interpolation order of four, and a grid spacing of 0.12 nm. Lennard-Jones interactions were truncated beyond 1 nm. All simulations were carried out in the GROMACS 2019 simulation package (42).

Analyses

To find the dominant conformational motion of PDF, principal-component analysis (PCA) of the Cartesian coordinates (43) of the PDF backbone was performed. The independent trajectories were superimposed using Cα and P atoms of the large subunit with respect to the experimental structure of the bare ribosome (PDB: 5AFI (24)). From the concatenated trajectories, frames of every 500 ps were used to construct the covariance matrix.

To study the presumed allostery, principal-component regression (PCR) was done for several ribosome parts. PCR is a supervised machine-learning algorithm that was previously proposed in the context of biomolecular simulations as functional mode analysis (44). Here, a functional quantity is defined to reflect the presence or absence of PDF, and a statistical model is built to predict from the trajectory projections onto selected principal components (PCs), i.e., the eigenvectors of the covariance matrix. The predicted values are denoted .

| (1) |

where denotes an ensemble average, is the coefficient determined by the training process, is a projection of the trajectory onto (the PC vector), and the sum runs over the selected PCs.

The model was trained by minimizing the mean-square error:

| (2) |

where the sum runs over the N frames of the training set. In practice, the problem is solved by maximizing the Pearson correlation coefficient (justified in (44)) using the training set.

| (3) |

where and are standard deviations of and (the projection of the trajectories onto ; see Eq. 4), respectively, and cov is the covariance.

The model was trained using two PDF+ and two PDF– trajectories, and the validation set consisted of the remaining pairs of trajectories. The last 500 ns of each trajectory were used to allow for system relaxation from the initial conditions. The model was built using the highest-eigenvalue PCs covering 95% of the total variance, thus the number of dimensions was vastly reduced. The PCA space was constructed only from the training data. Each frame from the validation set was classified to belong to the PDF+ or PDF– subset based on whether fm was greater than or lower than 0.5, respectively.

The PCs were calculated for various atomic selections (summarized in Table S1). We assumed that the atomic selections important for a good prediction of are those that change due to presence of the PDF. Since it was not a priori known which pairs of trajectories should be used for training and validation, we performed cross-validation. All six possible combinations for training and validation sets available for the four PDF+ and four PDF– trajectories were examined. Then, the quality of the atom selections was assessed using averaged over the six validation sets. The histograms of were calculated for each validation set separately as well as for data aggregated from all validation sets.

In PCR, a vector is defined as a linear combination of input PCA eigenvectors

| (4) |

which represents a conformational change best correlated with . According to functional mode analysis (44), the vector is called maximally correlated motion (MCM). The MCM was calculated for each validation set, and a consensus view was obtained as an intersection of the 20% of atoms with the highest MCM contribution.

The ensemble-weighted MCM (ewMCM) vector was defined as

| (5) |

where is the variance of the i-th PC and the sums run over selected PCs. ewMCM represents the most probable motion along as observed in simulations (44).

The analyses were done with custom python scripts using the MDAnalysis library (45,46).

Results

PDF is highly flexible when bound to the ribosome

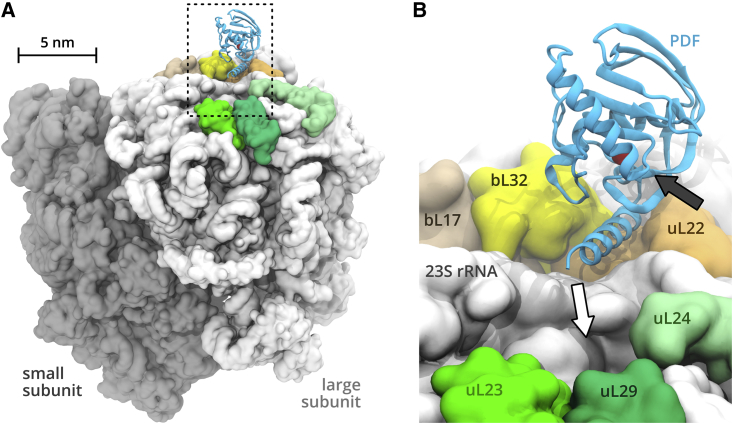

We carried out four independent unbiased MD simulations of PDF+ and PDF– and analyzed the last 1 s of each trajectory. As expected, the PDF remained bound to the ribosome surface throughout the course of all PDF+ simulations. The structural context of PDF is shown in Fig. 1. The PDF binds through its C-terminal α-helix to a groove formed by ribosomal proteins uL22, bL32, and rRNA. The C-terminus of PDF points to the exit of the ribosomal tunnel. The catalytic site of PDF is accessible from the right-hand side, as indicated by the black arrow in Fig. 1 B.

Figure 1.

Simulated ribosome-PDF complex. (A) A global view with the small and large ribosomal subunits in darker and lighter gray, respectively. (B) Structural context of PDF with labeled ribosome components represented by the dashed rectangle in (A). The white arrow points to the exit of the ribosomal tunnel, and the black arrow shows the access to the catalytic site. The catalytic Ni2+ ion is shown as a red sphere buried in the PDF. To see this figure in color, go online.

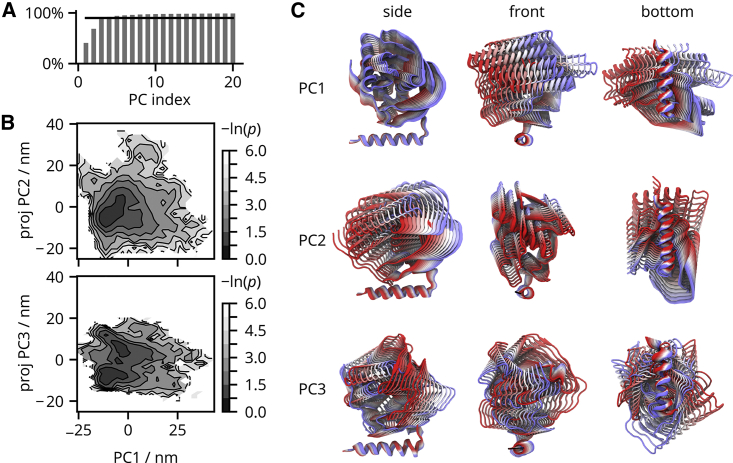

Fig. 2 shows the PCA of the PDF backbone. Because the large subunit was used for alignment, the obtained PCs reflect the PDF motion relative to the large subunit. From the percentage of explained variance plotted in Fig. 2 A, we can see that the first three PCs cover 90% of the total variance. The conformational modes described by the PCs are shown in Fig. 2 C. PC1 is a side-to-side swaying motion of the N-terminal catalytic domain about the C-terminal helix that is best visible from the front when looking along the helical axis. The C-terminal helix remains well localized on the ribosome surface and forms the axis of rotation. The last two C-terminal amino acids fluctuate more than the rest of the α-helix. PC2 is a front-to-back swaying best visible from a side view. PC3 is a rotational motion about a vertical axis perpendicular to the ribosome surface. Given the trajectory lengths of 1 s, the swaying of PDF is fast, on the order of hundreds of nanoseconds (time traces of PCs are given in Fig. S2).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the PDF motion on the ribosome surface. (A) Percentage of explained total variance as a function of number of PCs. (B) Projections of the trajectories onto eigenvectors PC1, PC2, and PC3 are shown as the negative natural logarithm of a probability density . (C) Structural representations of PC1, PC2, and PC3. The color scale goes from negative values (red) through white to positive (blue). The extremes represent values observed in MD simulations. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 2B shows two-dimensional projections of the trajectories onto the first three PCs. At the qualitative level, projections onto PC1 and PC2 show a single broad minimum. The PC3 has two minima that represent left- or right-rotated substates of the C-terminal helix. The motion along PC3 is less extensive than along PC1 or PC2. The independent trajectories sample different parts of the conformational space of PDF, so quantitative results such as differences in Gibbs energies are hard to obtain. Still, the projections of the independent trajectories onto the first three PCs overlap reasonably, so the PCA results support a fast and extensive conformational motion of the PDF on the ribosome.

To check how the alignment affects the apparent motion of PDF, we did a PCA for trajectories aligned with respect to the PDF C-terminal α-helix, namely residues 150–167 (Fig. S3). The PCA confirms that the catalytic domain undergoes a large-scale motion around a rather fixed C-terminal helix. The fluctuations of the helix within the binding site on the ribosome are below 1 Å, so the binding pose is rather stable. The large conformational flexibility of the bound PDF is also clearly visible on the overlay of trajectory snapshots (Fig. S4).

PDF modulates structure of uL22 inside the ribosomal tunnel

To characterize the structural effect of PDF on the uL22, we calculated the residue-wise root-mean-square deviation (rwRMSD) between the PDF+ and PDF– models (Fig. 3). First, we compared the PDF+ model of the ribosome with the C-terminal helix of the PDF previously determined by X-ray crystallography (PDB: 4V5B (21)) with the PDF– cryo-EM model (PDB: 5AFI (24)). Next, we calculated the rwRMSD between MD-based models obtained by averaging each trajectory over the last 1 s.

Figure 3.

Residue-wise root-mean-square deviation (rwRMSD) of uL22 with and without PDF bound. (A) Simulation-based rwRMSDs were calculated for average structures from all pairs of PDF+ and PDF– trajectories and averaged (black line). The standard deviations over the pairs are shown as a gray area. Experiment-based rwRMSD represents a single pair of PDF+ (PDB: 4V5B (21)) and PDF– (PDB: 5AFI (24)). Other E. coli PDF– models are shown in Fig. S6. The surface and tunnel loops are highlighted in blue and green, respectively. (B) rwRMSD projected onto the uL22 structure without PDF. (C) Selected residues with a high experiment-based rwRMSD. To see this figure in color, go online.

According to the rwRMSD, the PDF affects two regions of uL22, which are highlighted in blue and green in Fig. 3, A and B. A surface loop between N61 and D67 is part of the PDF-binding site. On the contrary, the uL22 extension of residues around R92, which protrudes into the exit tunnel, is located at a distance of about 5 nm from the PDF-binding site. In this regard, the experimental and simulation-based rwRMSDs agree well. The independent simulations provide consistent structural models (Fig. S5), which is also reflected by the low rwRMSD standard deviations (Fig. 3 A). These results are independent of the PDF– model used for the rwRMSD as tested for several E. coli ribosome models (Fig. S6).

The experiment-based models further yield high rwRMSDs for residues R11, R18, and K28 (Fig. 3 C), which reflects their highly rotated side chains. Inspection of the PDF+ model revealed that the conformation of K28 is likely incorrect and thus not relevant to the PDF binding. The conformations of R11 and R18 are related to the presence/absence of Mg2+ in their vicinity (Fig. S7). High rwRMSDs of R11, R18, and K28 were not observed in the simulations. We attribute this to the fact that all the simulations were started from the PDF– conformation of the ribosomes. The side-chain rotations in the folded ribosome might be slower than the simulation time, especially should the conformational change be connected to the binding/unbinding event of the nearby Mg2+ ions.

Classification model of the ribosome surface status

From the structural analysis, it appears that the tip of uL22 is sensitive to the presence of PDF and thus that the PDF binding has a nonlocal structural effect. To investigate possible allosteric pathways, which could transfer the information between the ribosome surface and its interior, we carried out PCR of several ribosome parts.

Indeed, some ribosome parts (their PCs) can predict the presence or absence of PDF better than others (Fig. 4 A). Of the ribosomal proteins near the PDF-binding site, only uL22 yielded a good model with Pearson correlation coefficient (standard deviation over validation sets; see materials and methods). The model constructed from uL22 PCs classified 98% of frames from the validation set correctly. As a control, we selected all 20th residues of ribosomal proteins of the large subunit. They are spread around the whole subunit, so their conformations should not correlate with the presence of PDF on the surface. Indeed, poor correlation between and was observed for this selection , and only 55% of PDF+ and 64% of PDF– frames were correctly classified, confirming no predictive power of the PDF presence by this selection of atoms.

Figure 4.

Principal-component regression of several ribosomal parts. (A) Pearson correlation coefficients obtained as mean values over six validation sets. Error bars correspond to standard deviations. (B) Percentage of correctly classified frames represented by mean values over six validation datasets. Error bars correspond to standard deviations. (C) Probability density functions of calculated for the PDF+ and PDF– components of the validation sets. Light areas represent individual validation sets, and the lines stand for aggregated probability densities of all validation sets. To see this figure in color, go online.

Fig. 4C shows the probability densities of for validation sets. A good model should have the histograms well separated, meaning that PDF+ and PDF– cases are correctly classified by the model. Here, uL22 yielded reasonable predictions. The PCR of the uL22 backbone yielded densities that overlapped more than densities calculated for uL22, including side chains. The model based on the uL22 backbone correctly classified only 78% of PDF+ frames of the validation set. This implies that the uL22 side chains are important for a successful prediction of the ribosome surface status.

To check the trivial case that the good prediction is just due to local conformational changes of the PDF-binding site on the ribosome surface, we tested nonlocal atoms’ selections, excluding the binding site. For instance, the predictions calculated from the uL22 tip alone, which is 4- to 5-nm-far away from the binding site, showed a good correlation but with overlapping probability densities. In the validation set, 94% and 85% of frames were classified correctly for the PDF+ and PDF– cases, respectively. Including the nucleotides around the tip (denoted uL22tip+surr. in Fig. 4) improved the model considerably; 99% of frames were correctly classified, and the correlation coefficient increased to . This means that the PDF binding is correlated with nonlocal conformational changes of the ribosome.

The best model was obtained from a selection of uL22 with a portion of rRNA below the PDF C-terminus , which included the PDF-binding site. This selection is denoted uL22+below. This model was investigated further to clarify presumed allostery.

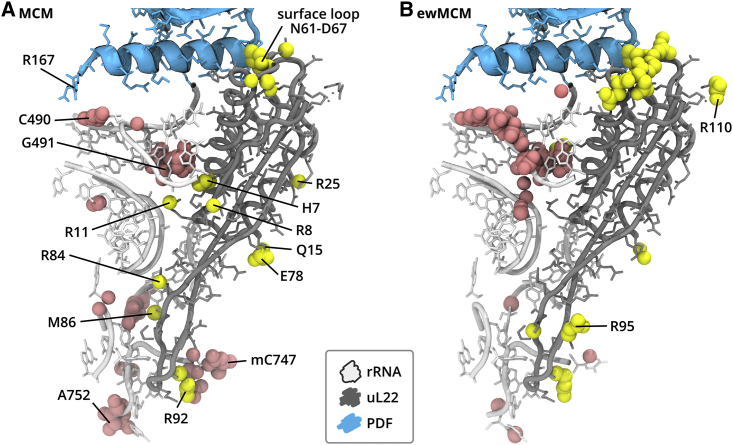

MCM explains the allostery

The vector components of MCM were projected onto the structure, revealing sites important for good prediction of PDF presence. Fig. 5 A shows the selection uL22+below. The atoms with the highest MCM components are highlighted (see materials and methods). The results for individual trajectories are shown in Fig. S8.

Figure 5.

PCR results projected onto the ribosome structure. PDF is shown in cyan, uL22 in gray, and a portion of 23S rRNA in white. A consensus selection of atoms contributing the most to the maximally correlated motion (MCM; A), or ensemble-weighted MCM (ewMCM; B) of the uL22+below selection are shown as pink and yellow spheres for rRNA and uL22, respectively. To see this figure in color, go online.

First, the presence or absence of the PDF is connected with a motion of the uL22 surface loop near N61, as indicated by numerous atoms contributing substantially to the MCM. This observation is consistent with the rwRMSD of both experiment- and simulation-based structural models (Fig. 3), and it represents a local conformational effect of the PDF. Second, the PDF binding is correlated with a motion of a 23S rRNA loop of residues C487 to G493, with the most affected nucleotide being C490. In the bare ribosome, C490 frames the tunnel exit on the side opposite to the tip of uL24. When PDF binds, its C-terminal R167 directly affects the conformation of C490, which likely propagates downwards through the tunnel walls. Apart from the walls, the signal propagates via the interface between uL22 and 23S rRNA, where positive side chains of R8, R11, R25, and R84 and neutral H7, Q15, and M86 possess a high MCM component. Finally, the PDF presence and absence is correlated with the nonlocal motion near the tunnel constriction, namely R92 of uL22 and mC747 and A752 of rRNA. It seems likely that the conformational motion of the R11 side chain facilitates the communication between the rRNA loop near the tunnel exit and the tunnel constriction. Other residues on the boundary of the globular and loop-extension domains of uL22 (R8, Q15, E78) may also contribute.

The Gibbs energy landscape governs the conformational motion of a system of interest and may restrict the MCM determined by PCR. Thus, the MCM may cover motions that are unavailable for the system at the given temperature. To better understand allostery represented by the MCM, we calculated the ewMCM (44), which represents “the most probable collective motion that accomplishes a specific displacement along the MCM” (44). Therefore, here, the ewMCM vector shows the motion most correlated with the presence or absence of PDF and observed in the MD simulations.

Fig. 5B reveals that the ewMCM overlaps with the MCM in several regions, most notably in the surface loop of uL22, and the rRNA loop below the PDF C-terminal helix. The residues in the exit tunnel like R92 of uL22 or A752 of rRNA contribute, too, but the number of atoms picked by consensus (see materials and methods) with a high ewMCM contribution is lower in this region than for the MCM. Interestingly, the residues on the boundary between the uL22 globular and loop-extension domains (R11, Q15, etc., in Fig. 5) are missing in ewMCM. It means that on one hand, in MD simulations, the motion of H7, R11, or E78 possesses a low variance, so it does not appear in the ewMCM. On the other hand, due to including low-variance PCs for the PCR, the motion of these residues appears in the MCM. Consequently, the allostery triggered by PDF, as identified by PCR, does not fully occur within the timescale of the simulations and remains latent in certain ribosome parts.

Discussion

We used atomistic MD simulations and a supervised-learning statistical model to understand the effect of PDF binding to the ribosome surface. We based our simulations on several experimental structures. The cryo-EM structure of the ribosome-PDF complex was only partial because the PDF-binding mode was represented by the PDF’s C-terminal α-helix (21). Our simulations confirmed the binding mode for the full PDF. Unlike cryo-EM, our simulations revealed that due to the extensive conformational flexibility of PDF, the ribosome surface may occasionally interact not only with the C-terminal helix but also with the PDF’s main catalytic domain. Therefore, the structural effect of PDF on the uL22 surface loop was larger in simulations than in experiments. The role of Mg2+ ions in ribosome-NC interactions was recently emphasized (47,48). A brief inspection of the simulations revealed a redistribution of Mg2+ ions near uL22 on the ribosome surface. The differences were, however, modest, and due to the limited sampling, no quantitative conclusions could be drawn. On the other hand, two Mg2+ binding sites on the interface between rRNA and uL22 could explain different conformational states of uL22 residues R11 and R18 in the experimental models.

Recently, the kinetic mechanism of the formylmethionine deformylation was described in detail (49). The PDF binding to the ribosome is a rapid process. The conditions in vivo allow each PDF molecule to sample about 60 ribosomes per second. The docking of the NC N-terminus to the PDF is so fast that it was not identified as an additional kinetic step in the mechanism (49). Our simulations showed a fast and extensive conformational motion of the PDF with respect to the ribosome on the submicrosecond timescale. Within a single PDF-binding event, the PDF conformational mobility may facilitate the NC recruitment to the PDF catalytic cavity, explaining the fast rate of the NC-PDF binding.

The extensive conformational motion of PDF may also contribute to the experimentally observed interference of PDF with other protein-biogenesis factors like trigger factor (TF) and methionine aminopeptidase (MAP). A low-resolution cryo-EM structure suggested (22) that PDF and MAP share a common binding site. When PDF is bound, however, MAP is able to bind on an alternative site so that the N-terminal excision may be accomplished faster. Bornemann et al. argued that the PDF changes the mode of TF binding (50) on translating ribosomes. The cryo-EM structure of the ribosome-PDF-TF ternary complex confirmed a simultaneous binding of the two factors (22). The motion of PDF bound to the ribosome suggests that the PDF may also influence more distant locations on the ribosome surface other than just the PDF-binding site.

A major finding of this study was the identification of allostery triggered by the PDF binding to the ribosome. Our simulations and statistical modeling revealed a path propagated from the PDF through the tunnel walls deeper into the tunnel. The cross-validation pointed out that MCM vectors differed: a typical scalar product of MCM vectors from two different validation sets was about 0.6 (Fig. S9). Consequently, the selections of atoms contributing the most to the MCM were different for various validation sets (Fig. S8). Still, these conclusions are independent on the training/validation set: 1) uL22 side chains, not the backbone, are correlated with the ribosome surface status, 2) the tunnel constriction including uL22 amino acid residues and 23S rRNA is correlated with the ribosome surface status, and 3) rRNA surrounding the 23S residue C490 transfers the allosteric signal deeper into the tunnel. The MCM sites overlap with allosteric regions identified by an analysis of multiple sequence alignment of 23S RNAs (51). This is true especially about 23S residues between mC747 and A752 located next to the uL22 tip, which were shown to be involved in a long-distance coupling (51).

The equilibrium constant of PDF-ribosome association is independent—within the experimental uncertainty—of the translation status of the ribosome (49,52). Hence, PDF binds equally strongly whether the NC is present in the tunnel or not, suggesting that the information about the tunnel status does not propagate to the ribosome surface. Assuming that the allostery from the tunnel to the surface would affect the PDF-binding affinity, our observations imply that the allosteric signal is likely unidirectional from the surface to the interior.

Conclusion

Using atomistic computer simulations and analysis of structural models, we showed that PDF modulates the structure and dynamics of distant parts of the empty exit tunnel, most notably the tunnel constriction. The constriction contains multiple side chains with a positive charge, some of which were identified as being coupled to the PDF binding (R92 of uL22, for instance). Previously, it has been shown that the electrostatics of the exit tunnel affect the rate of NC translocation (53). Also, the tunnel near the constriction encourages NC compaction (17). The delicate equilibrium of the constriction may affect how nascent peptides translocate through the tunnel. We speculated that this may be especially important early during translation, when the N-terminus of the NC diffuses through the tunnel toward the exit. The pulling force later generated by the cotranslational folding (54) is likely missing at this stage, so even small variances of the tunnel walls may support the translocation. PDF may thus ease, through the allosteric modulation of tunnel walls, the N-terminus ejection.

Author contributions

H.M. performed MD simulations and analyses, M.Č. built the structural models and helped with the analyses, and M.H.K. performed MD simulations and analyses and, with the help of all other authors, wrote the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lars V. Bock for invaluable discussions and commenting the manuscript and Lucie Kubíčková for her help with the simulation system preparation. The research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (project 19-06479Y). M.Č. acknowledges the support of the Internal Grant Agency of UCT Prague (project 403-88-2091).

Declaration of interests

None declared.

Editor: Frauke Graeter.

Footnotes

Supporting material can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpj.2022.11.004.

Supporting material

References

- 1.Kudva R., Tian P., et al. von Heijne G. The shape of the bacterial ribosome exit tunnel affects cotranslational protein folding. Elife. 2018;7 doi: 10.7554/eLife.36326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berisio R., Schluenzen F., et al. Yonath A. Structural insight into the role of the ribosomal tunnel in cellular regulation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2003;10:366–370. doi: 10.1038/nsb915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Seidelt B., Innis C.A., et al. Beckmann R. Structural insight into nascent polypeptide chain–mediated translational stalling. Science. 2009;326:1412–1415. doi: 10.1126/science.1177662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bischoff L., Berninghausen O., Beckmann R. Molecular basis for the ribosome functioning as an L-tryptophan sensor. Cell Rep. 2014;9:469–475. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van der Stel A.-X., Gordon E.R., et al. Innis C.A. Structural basis for the tryptophan sensitivity of TnaC-mediated ribosome stalling. bioRxiv. 2021 doi: 10.1101/2022.05.23.493104. 2021.03.31.437805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arenz S., Bock L.V., et al. Wilson D.N. A combined cryo-EM and molecular dynamics approach reveals the mechanism of ErmBL-mediated translation arrest. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:12026. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beckert B., Leroy E.C., et al. Wilson D.N. Structural and mechanistic basis for translation inhibition by macrolide and ketolide antibiotics. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:4466. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24674-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Su T., Cheng J., et al. Beckmann R. The force-sensing peptide VemP employs extreme compaction and secondary structure formation to induce ribosomal stalling. Elife. 2017;6 doi: 10.7554/eLife.25642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsson O.B., Hedman R., et al. von Heijne G. Cotranslational protein folding inside the ribosome exit tunnel. Cell Rep. 2015;12:1533–1540. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.07.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gumbart J., Schreiner E., et al. Schulten K. Mechanisms of SecM-mediated stalling in the ribosome. Biophys. J. 2012;103:331–341. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2012.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Makarova T.M., Bogdanov A.A. The ribosome as an allosterically regulated molecular machine. Biochem. Mosc. 2017;82:1557–1571. doi: 10.1134/S0006297917130016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolář M.H., Nagy G., et al. Grubmüller H. Folding of VemP into translation-arresting secondary structure is driven by the ribosome exit tunnel. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50:2258–2269. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guzel P., Yildirim H.Z., et al. Kurkcuoglu O. Exploring allosteric signaling in the exit tunnel of the bacterial ribosome by molecular dynamics simulations and residue network model. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2020;7 doi: 10.3389/fmolb.2020.586075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kramer G., Boehringer D., et al. Bukau B. The ribosome as a platform for Co-translational processing, folding and targeting of newly synthesized proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:589–597. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bornemann T., Jöckel J., et al. Wintermeyer W. Signal sequence–independent membrane targeting of ribosomes containing short nascent peptides within the exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2008;15:494–499. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nakatogawa H., Ito K. The ribosomal exit tunnel functions as a discriminating gate. Cell. 2002;108:629–636. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00649-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu J., Deutsch C. Folding zones inside the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2005;12:1123–1129. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giglione C., Fieulaine S., Meinnel T. N-terminal protein modifications: bringing back into play the ribosome. Biochimie. 2015;114:134–146. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2014.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giglione C., Pierre M., Meinnel T. Peptide deformylase as a target for new generation, broad spectrum antimicrobial agents. Mol. Microbiol. 2000;36:1197–1205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee M.D., She Y., et al. Scheinberg D.A. Human mitochondrial peptide deformylase, a new anticancer target of actinonin-based antibiotics. J. Clin. Investig. 2004;114:1107–1116. doi: 10.1172/JCI22269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bingel-Erlenmeyer R., Kohler R., et al. Ban N. A peptide deformylase–ribosome complex reveals mechanism of nascent chain processing. Nature. 2008;452:108–111. doi: 10.1038/nature06683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhakta S., Akbar S., Sengupta J. Cryo-EM structures reveal relocalization of MetAP in the presence of other protein biogenesis factors at the ribosomal tunnel exit. J. Mol. Biol. 2019;431:1426–1439. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2019.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bock L.V., Kolář M.H., Grubmüller H. Molecular simulations of the ribosome and associated translation factors. Curr. Opin. Struc. Biol. 2018;49:27–35. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fischer N., Neumann P., et al. Stark H. Structure of the E. Coli ribosome-EF-Tu complex at <3 A resolution by Cs-corrected cryo-EM. Nature. 2015;520:567–570. doi: 10.1038/nature14275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith K.J., Petit C.M., et al. Christensen S.B. Structural variation and inhibitor binding in polypeptide deformylase from four different bacterial species. Protein Sci. 2003;12:349–360. doi: 10.1110/ps.0229303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maier J.A., Martinez C., et al. Simmerling C. ff14SB: improving the accuracy of protein side chain and backbone parameters from ff99SB. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2015;11:3696–3713. doi: 10.1021/acs.jctc.5b00255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cornell W.D., Cieplak P., et al. Kollman P.A. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1995;117:5179–5197. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pérez A., Marchán I., et al. Orozco M. Refinement of the AMBER force field for nucleic acids: improving the description of α/γ conformers. Biophys. J. 2007;92:3817–3829. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.097782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zgarbová M., Otyepka M., et al. Jurečka P. Refinement of the Cornell et al. Nucleic acids force field based on reference quantum chemical calculations of glycosidic torsion profiles. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2011;7:2886–2902. doi: 10.1021/ct200162x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aduri R., Psciuk B.T., et al. SantaLucia J. AMBER force field parameters for the naturally occurring modified nucleosides in RNA. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2007;3:1464–1475. doi: 10.1021/ct600329w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., et al. Hermans J. In: Intermolecular Forces: Proceedings of the Fourteenth Jerusalem Symposium on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry Held in Jerusalem, Israel, April 13–16, 1981. Pullman B., editor. Springer Netherlands; 1981. Interaction models for water in relation to protein hydration; pp. 331–342. The Jerusalem Symposia on Quantum Chemistry and Biochemistry. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Joung I.S., Cheatham T.E. Determination of alkali and halide monovalent ion parameters for use in explicitly solvated biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2008;112:9020–9041. doi: 10.1021/jp8001614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huter P., Arenz S., et al. Wilson D.N. Structural basis for polyproline-mediated ribosome stalling and rescue by the translation elongation factor EF-P. Mol. Cell. 2017;68:515–527.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Warias M., Grubmüller H., Bock L.V. tRNA dissociation from EF-Tu after GTP hydrolysis: primary steps and antibiotic inhibition. Biophys. J. 2020;118:151–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2019.10.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bussi G., Donadio D., Parrinello M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126 doi: 10.1063/1.2408420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Berendsen H.J.C., Postma J.P.M., et al. Haak J.R. Molecular dynamics with coupling to an external bath. J. Chem. Phys. 1984;81:3684–3690. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parrinello M., Rahman A. Polymorphic Transitions in single crystals: a new molecular dynamics method. J. Appl. Phys. 1981;52:7182–7190. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hess B. P-LINCS: a parallel linear constraint solver for molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:116–122. doi: 10.1021/ct700200b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feenstra K.A., Hess B., Berendsen H.J.C. Improving efficiency of large time-scale molecular dynamics simulations of hydrogen-rich systems. J. Comput. Chem. 1999;20:786–798. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-987X(199906)20:8<786::AID-JCC5>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hess B., Kutzner C., et al. Lindahl E. Gromacs 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008;4:435–447. doi: 10.1021/ct700301q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Darden T., York D., Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: an n·log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abraham M.J., Murtola T., et al. Lindahl E. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX. 2015;1–2:19–25. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amadei A., Linssen A.B.M., Berendsen H.J.C. Essential dynamics of proteins. Proteins. 1993;17:412–425. doi: 10.1002/prot.340170408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hub J.S., de Groot B.L. Detection of functional modes in protein dynamics. PLoS Comp. Biol. 2009;5 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1000480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gowers R.J., Linke M., et al. Beckstein O. Proceedings of the 15th Python in Science Conference. 2016. MDAnalysis: a Python package for the rapid analysis of molecular dynamics simulations; pp. 98–105. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Michaud-Agrawal N., Denning E.J., et al. Beckstein O. MDAnalysis: a Toolkit for the analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:2319–2327. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guzman-Luna V., Fuchs A.M., et al. Cavagnero S. An intrinsically disordered nascent protein interacts with specific regions of the ribosomal surface near the exit tunnel. Communications Biology. 2021;4:1–17. doi: 10.1038/s42003-021-02752-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cassaignau A.M.E., Włodarski T., et al. Christodoulou J. Interactions between nascent proteins and the ribosome surface inhibit Co-translational folding. Nat. Chem. 2021;13:1214–1220. doi: 10.1038/s41557-021-00796-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bögeholz L.A.K., Mercier E., et al. Rodnina M.V. Kinetic control of nascent protein biogenesis by peptide deformylase. Sci. Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-03969-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bornemann T., Holtkamp W., Wintermeyer W. Interplay between trigger factor and other protein biogenesis factors on the ribosome. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:4180. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Walker A.S., Russ W.P., et al. Schepartz A. RNA sectors and allosteric function within the ribosome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:19879–19887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1909634117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandikci A., Gloge F., et al. Kramer G. Dynamic enzyme docking to the ribosome coordinates N-terminal processing with polypeptide folding. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2013;20:843–850. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lu J., Deutsch C. Electrostatics in the ribosomal tunnel modulate chain elongation rates. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;384:73–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.08.089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Goldman D.H., Kaiser C.M., et al. Bustamante C. Mechanical force releases nascent chain–mediated ribosome arrest in vitro and in vivo. Science. 2015;348:457–460. doi: 10.1126/science.1261909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.