Abstract

We survey efforts that track food security in Africa using phone surveys during the COVID-19 pandemic. Phone surveys are concentrated in a few countries mostly focusing on a narrow theme. Only a few allow heterogeneous analyses across socioeconomic, spatial, and intertemporal dimensions across countries, leaving important issues inadequately enumerated. We recommend that the scientific community focuses on countries (and regions and groups within countries) where the evidence base is thin, and that policymakers in less researched areas attract more research by improving their statistical capacity, openness, and governance.

Keywords: Phone survey, COVID-19, Food security, Africa

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic and its countermeasures have shaped lives and livelihoods around the world, causing economic contractions (IFPRI, 2020), worsening poverty (Laborde et al., 2021) and food insecurity (Dasgupta & Robinson, 2022; Egger et al., 2021; Jaacks et al., 2021). Given their weak economic and health care systems and largely immunocompromised populations, African countries carry a particularly heavy burden in terms of COVID-19 induced welfare losses (Djankov & Panizza, 2020; IFPRI et al., 2020). At the same time, COVID-19 risks reinforcing pre-existing socioeconomic disparities within and across countries in the region (Nechifor et al., 2021; Poudel & Gopinath, 2021).

Empirical evidence on the scale and the nature of the impacts of the pandemic and its countermeasures, while growing, is quite limited, partly due to the lack of suitable, comparable, and timely micro-level data (Delius et al., 2020; Gourlay et al., 2021). This lack of data also stems from the way COVID-19 is transmitted person-to-person, which inhibits face-to-face survey data collection. To overcome this challenge, high-income countries have managed to rely on real-time economic data as well as web-based surveys. In low-income countries in Africa, these options were not widely available and may even have worsened as the National Statistical Offices (NSOs) in these countries were hit particularly hard by the pandemic (UNDESA and World Bank, 2020)1. Fortunately, the nascent expansion of mobile phone subscriptions as well as the learning experience from the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa and the 2017 drought- and conflict- related food insecurity crisis in West and East Africa helped to deploy phone surveys quickly at the beginning of the ongoing pandemic (Gourlay et al., 2021; Hoogeveen & Pape, 2020).

The application of the phone surveys involves several challenges. First, phone surveys involve constraints regarding the type and size of questions that could be included in the interviews. In order to limit respondent fatigue, interview questions need to be kept short and simplified and answer choices limited (e.g., yes or no). Furthermore, interlinked and complex questions such as consumption modules are difficult to include in phone surveys (Hirvonen et al., 2021). While such a concern about respondent fatigue is not uncommon in surveys in general (Ambler et al., 2021), it is more pronounced in phone surveys (Abate et al., 2021). Second, contrary to face-to-face surveys, phone surveys don’t allow enumerators to observe visual non-verbal cues from respondents. While rigorous training of enumerators and certain lead-in scripts and probes could help identify and reduce the problem, they don’t fully address it (Dillon, 2012). Relatedly, the absence of in-person communication during phone interviews might make it difficult to build trust with the respondents, introducing willful error by a respondent, especially if the questions are sensitive (Dabalen et al., 2016).

There are also certain limitations that are more relevant with respect to conducting phone surveys in Africa and low-income countries’ settings in general. First, sampling bias is a concern since the survey could only be administered to respondents with working phones and phone ownership varies systematically across and within countries based on sociodemographic characteristics (e.g. age, education and wealth status) and place of residence (rural vs. urban areas) (Dabalen et al., 2016; Dillon, 2012; Kühne et al., 2020). While the use of representative baseline survey data could reduce the bias, it does not fully eliminate it (Ambel et al., 2021). Another limitation of phone surveys in Africa relates to the availability and the systematic variation in infrastructure particularly electricity and mobile signal, which is rampant in the continent (World Bank, 2009). Such a disparity among locations effectively creates a sampling problem by introducing bias, since availability and quality of infrastructure is likely to be correlated with other important characteristics, such as urban proximity, availability and quality of public goods (e.g. road, health centers, water supply) and average wealth (Dillon, 2012).

Notwithstanding their shortcomings, phone surveys have proven useful and cost-effective in collecting data in remote and conflict areas and in circumstances where face-to-face data collection appears to be risky to the safety of the enumerators and the survey respondents (Dabalen et al., 2016; Delius et al., 2020; Hoogeveen & Pape, 2020; Sturges & Hanrahan, 2004). Due to this and following the onset of the ongoing pandemic, large number of phone-based interviews are being conducted throughout the continent. However, we currently lack an overview of efforts to trace food security in Africa using phone surveys, risking duplication or omission of data collection efforts. We address this knowledge gap by reviewing all phone surveys tracking food security in Africa since the beginning of the pandemic, including our own phone survey called Life with Corona-Africa (LwC-Africa). We concentrate our review on five key issues, namely the topical, temporal, and geographic dimensions as well as geospatial coding and open access of the data.

It is true that phone surveys came to prominence in Africa due to the COVID-19 pandemic. However, their use might continue into the future as a standalone data collection model or in combination with face-to-face interviewing (Gourlay et al., 2021). The experience during the pandemic highlights that data such as those obtained through phone surveys have the potential to strengthen and modernize core data collection programs and be a key component of the national data systems (UNDESA and World Bank, 2020). Therefore, our review is helpful to highlight the broader picture of the size, the content, and the spatial and temporal distribution of the phone surveys as well as identify evidence gaps to inform future designs.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. The next section first presents the data sources used in the paper and then describes the timeline, distribution and contents of the phone surveys. Section 3 discusses the implication of the results. Section 4 concludes.

Data and results

Data sources

For our review, we searched for phone-based surveys on COVID-19 and food security in Africa since the beginning of the pandemic in four steps2. First, we searched international repositories for registered COVID-19 and food security-related surveys and projects on Africa: the central registry of American Economic Association; the Economics Observatory (ECO) of European Economic Association (EEA), and the RECOVR research hub of Innovation for Poverty Action (IPA). Second, we searched for mentions of phone surveys in blogs, news articles, policy briefs, and academic literature on the websites of Google Scholar, IPA, and Relief Web, combining the terms (“COVID 19” OR “COVID-19” OR CORONA OR coronavirus), “food security”, (“phone survey” or “telephone survey”) for Africa, for the sub-regions and the individual countries. Third, and building on the findings of step two, we searched on the websites of African national statistical offices and several international organizations (World Bank, FAO, WHO, and WFP) using the same search terms. Finally, we evaluated all identified phone surveys to compile our final census of phone-based surveys on COVID-19 and food security in Africa since the beginning of the pandemic.

To examine the correlates of phone survey intensity, we used several indicators extracted from multiple data sources including the World Development Indicators (WDI) at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator, Fragile State Index (FSI) generated and made available by the Fund for Peace (FFP) at https://fragilestatesindex.org/ and COVID-19 caseloads and deaths from https://ourworldindata.org.

Results

Description of phone surveys

Our search yielded 234 completed or ongoing phone surveys on COVID-19 in Africa as of November 15, 2021 (Table 1)3. A large share of these (90, or 39%) are rapid surveillance surveys aimed at assessing knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus. Typically, these are cross-sectional and individual-level opinion surveys conducted at the onset of the pandemic across multiple countries in or including Africa. The major leading organizations of such surveys include Partnership for Evidence-based COVID-19 Response (PERC), 60 Decibels, GeoPoll, and FinMark Trust (Table 5 in the Appendix). The World Bank and WFP are two prominent organizations that have been collecting near real-time phone survey data across most of the countries in the continent. The World Bank capitalized on its pre-pandemic cooperation with national statistical offices (NSO) to collect High Frequency Phone Surveys (HFPS) or Household Monitoring Surveys (HMS) in a large number of countries, including most countries in Africa, to inform a wide range of knowledge products (Gourlay et al., 2021)4. To supplement inputs used in its global hunger monitoring system, the World Food Program (WFP) conducts continuous phone-based food security monitoring through call centers. At the end of 2021, the system was already set up in several developing countries, including 26 African countries, to collect data on a rolling basis over a three-month period5. Other surveys include rural household surveys implemented by CGIAR Research Centers (e.g. IFPRI), surveys conducted by academic intuitions (e.g., the university of Oxford, and ETH Zürich), and others (e.g., IGZ/ISDC, the hosts of our study, LwC-Africa). Table 9 in the Appendix presents the complete list of all the phone surveys including start time, sample size, number of survey rounds and internet links.

Table 1.

Major types of phone surveys

| Survey types | Number | % share |

|---|---|---|

| Rapid surveillance surveys | 90 | 38.6 |

| World Bank-High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | 20 | 8.6 |

| World Bank-Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | 14 | 6.0 |

| World Food Program-Hunger & COVID monitoring surveys | 26 | 11.2 |

| Rural HH surveys | 19 | 8.2 |

| University led surveys | 46 | 19.7 |

| Other surveys | 18 | 7.7 |

| Total | 234 | 100 |

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

Table 5.

Major lead organizations of the survey

| Leading organizations | Frequency | Survey rounds | Sample size | Survey duration* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Multinational agenciesa | 71 | 3.0 | 1,000 | 12 |

| Research & survey consultantsb | 50 | 2.0 | 632 | 6 |

| CGIAR Research Centersc | 12 | 1.5 | 522 | 5 |

| Consortiumsd | 51 | 2.0 | 1,057 | 6 |

| Universitiese | 46 | 1.0 | 1,004 | 4 |

| Country statistical offices | 4 | 2.5 | 2,180 | 9 |

| Total | 234 | 2 | 1,001 | 6 |

aThis includes the World Bank, the World Food Program (WFP), European commission, CDC Africa, and ActionAid

bThis includes 60 Decibels, BRAC international, GeoPoll, IDInsight, Innovation for Poverty Action (IPA) and FinMark Trust

cThis includes International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI) and The International Center for Agriculture Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA)

dThis includes Partnership for Evidence-based COVID-19 Response (PERC), Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC), and Leibniz Institute for Vegetable and Ornamental Crops (IGZ)/ International Security and Development Center (ISDC)

eThis includes international universities (e.g. UC Berkeley, MIT, University of Oxford)

*Survey duration is measured in months

Table 9.

Complete list of phone surveys on COVID-19 and food security in Africa

| No | Survey Description | Lead organization | Start time | country | Sample size | Food Security included? | Food security measures | Date updated | Internet link | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Access to food? | FIES? | Food gap? | FCS? | |||||||||

| 1 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Central African Republic | 600 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 2 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 8/1/2020 | Central African Republic | 1266 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 3 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Gabon | 1656 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 28-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 4 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Chad | 1748 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 29-Sep-21 | https://microdata.worldbank.org |

| 5 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 8/1/2020 | Gambia | 1437 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 6 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Liberia | 1920 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 7 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Mauritius | 924 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 8 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Tunisia | 1032 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 17-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 9 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank, LSMS | 4/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 3200 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 10 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank, LSMS | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 1950 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 16-Feb-20 | www.worldbank.org |

| 11 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank, LSMS | 4/1/2020 | Malawi | 2337 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 16-Feb-20 | www.worldbank.org |

| 12 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank, LSMS | 6/1/2020 | Uganda | 2226 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 31-Aug-21 | https://microdata.worldbank.org |

| 13 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Mali | 1700 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 14 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 7/1/2020 | Djibouti | 1486 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | https://microdata.worldbank.org |

| 15 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | South Sudan | 1213 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 2-Mar-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 16 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Zambia | 1602 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 18-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 17 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank | 6/1/2020 | Zimbabwe | 1747 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | March 30 2021 | www.worldbank.org |

| 18 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank | 6/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 1082 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 19 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Madagascar | 1240 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 18-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 20 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Senegal | 1220 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 17-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 21 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Kenya | 5389 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 8-Mar-21 | https://microdata.worldbank.org |

| 22 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Ghana | 3265 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 23 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 7/1/2020 | Guinea | 1968 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 24 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Libya | 521 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 25 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Mozambique | 1097 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 18-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 26 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 11/1/2020 | Rwanda | 1396 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 27 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 6/1/2020 | Sudan | 4032 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 18-Oct-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 28 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 7/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 6570 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 31-Mar-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 29 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 7/1/2020 | Somalia | 2811 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 30 | Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 7/1/2020 | Sao Tome and Principe | 1025 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 18-Oct-21 | https://microdata.worldbank.org |

| 31 | High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The World Bank | 9/1/2020 | Congo, Rep. | 1386 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 32 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Cameroon | 1043 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 33 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Cameroon | 1449 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 34 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 1036 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 35 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 1416 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 36 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 1009 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 37 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 1351 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 38 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Egypt, Arab Rep. | 1098 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 39 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Egypt, Arab Rep. | 1206 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 40 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 1021 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 41 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 1571 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 42 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Ghana | 1001 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 43 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Ghana | 1338 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 44 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Guinea | 1034 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 45 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Guinea | 1283 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 46 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Kenya | 1031 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 47 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Kenya | 1224 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 48 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Liberia | 1059 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 49 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Liberia | 1366 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 50 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Morocco | 1045 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 51 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Mozambique | 1057 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 52 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Mozambique | 1314 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 53 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Nigeria | 1068 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 54 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Nigeria | 1304 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 55 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Senegal | 1039 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 56 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Senegal | 1259 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 57 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | South Africa | 1099 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 58 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | South Africa | 1395 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 59 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Sudan | 1101 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 60 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Sudan | 1438 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 61 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Tanzania | 1103 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 62 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Tunisia | 1004 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 63 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Tunisia | 1218 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 64 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Uganda | 1073 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 65 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Uganda | 1286 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 66 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 3/1/2020 | Zambia | 1035 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 67 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Zambia | 1290 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 68 | PERC COVID-19 survey 1 | PERC | 4/1/2020 | Zimbabwe | 1034 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 69 | PERC COVID-19 survey 2 | PERC | 8/1/2020 | Zimbabwe | 1333 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://www.ipsos.com |

| 70 | Rural household phone survey | IFPRI | 6/1/2020 | Senegal | 750 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 71 | Rural household phone survey | IFPRI | 8/1/2020 | Ghana | 543 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 2-Nov-21 | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 72 | Rural household phone survey | IFPRI | 8/1/2020 | Malawi | 1020 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 2-Mar-21 | https://ebrary.ifpri.org/digital |

| 73 | Rural household Phone survey | IFPRI | 10/1/2020 | Niger | 403 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 74 | Rural household phone survey | IFPRI | 8/1/2020 | Nigeria | 1000 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 1-Mar-21 | https://www.ifpri.org/ |

| 75 | Phone survey of PSNP households | IFPRI | 6/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 1500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.ifpri.org/ |

| 76 | Lagos Trader Survey | Stanford University | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 765 | yes | no | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org/ |

| 77 | Life with Corona Africa survey | IGZ and ISDC | 1/1/2021 | Uganda | 500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 30-Sep-21 | https://www.igzev.de |

| 78 | Life with Corona Africa survey | IGZ and ISDC | 1/1/2021 | Tanzania | 500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 30-Sep-21 | https://www.igzev.de |

| 79 | Life with Corona Africa survey | IGZ and ISDC | 1/1/2021 | Sierra Leone | 500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 30-Sep-21 | https://www.igzev.de |

| 80 | Life with Corona Africa survey | IGZ and ISDC | 1/1/2021 | Mozambique | 500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 30-Sep-21 | https://www.igzev.de |

| 81 | Smallholder Farmer Perceptions about COVID-19 | Kansas State University | 6/1/2020 | Senegal | 872 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Mar-21 | https://www.sciencedirect.com |

| 82 | Survey of weekly Financial and Health Diaries | Vrije Universiteit & Tinbergen Institute | 2/1/2020 | Kenya | 328 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.aighd.org |

| 83 | Survey on COVID-19 Knowledge and Social Distancing | University of Massachusetts | 4/1/2020 | Ghana | 362 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 84 | Survey on COVID-19 Knowledge and Social Distancing | University of Massachusetts | 4/1/2020 | Malawi | 563 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 85 | Survey on COVID-19 Knowledge and Social Distancing | University of Massachusetts | 4/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 633 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 86 | Survey on COVID-19 Knowledge and Social Distancing | University of Massachusetts | 4/1/2020 | Tanzania | 557 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 87 | Survey on delivery of health & nutrition services | IFPRI | 12/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 233 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 1-Nov-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 88 | Survey on Economic Outcomes and Resilience to COVID-19 | UC Berkeley | 4/27/2020 | Kenya | 1500 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://kenyacovidtracker.org |

| 89 | Survey on impact of Covid-19 on economic outcomes | University of Oxford | 8/1/2020 | Uganda | 1250 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 90 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Benin | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 91 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 92 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Ghana | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 93 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 94 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 95 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Mozambique | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 96 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 97 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Rwanda | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 98 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | South Africa | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 99 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Uganda | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 100 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Zambia | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 101 | Survey on knowledge and perceptions of coronavirus | GeoPoll | 4/1/2020 | Tanzania | 400 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.geopoll.com |

| 102 | Survey on the effect of COVID-19 Across the Globe | BRAC International | 4/1/2020 | Tanzania | 241 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | http://www.brac.net |

| 103 | Survey on the effect of COVID-19 Across the Globe | BRAC International | 4/1/2020 | Uganda | 352 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | http://www.brac.net |

| 104 | Survey on the effect of COVID-19 Across the Globe | BRAC International | 4/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 219 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | http://www.brac.net |

| 105 | Survey on the effect of COVID-19 Across the Globe | BRAC International | 4/1/2020 | Liberia | 223 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | http://www.brac.net |

| 106 | Survey on the effect of COVID-19 Across the Globe | BRAC International | 4/1/2020 | Rwanda | 151 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | http://www.brac.net |

| 107 | Effect of the pandemic in poor urban neighborhoods | ETH Zurich | 5/1/2020 | Ghana | 993 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 12-Feb-21 | https://dec.ethz.ch |

| 108 | Effect of the pandemic in poor urban neighborhoods | ETH Zurich | 5/1/2020 | South Africa | 385 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 12-Feb-21 | https://dec.ethz.ch |

| 109 | Survey on the Impact of COVID-19 and Cash Transfers | University of California | 5/1/2020 | Liberia | 593 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 110 | Survey on the Impact of COVID-19 and Cash Transfers | University of California | 5/1/2020 | Malawi | 596 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 111 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 768 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 112 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 398 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 113 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Ghana | 419 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 114 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 2398 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 115 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Madagascar | 210 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 116 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 3432 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 117 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Rwanda | 1084 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 118 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Senegal | 252 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 119 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 1529 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 120 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | South Africa | 1009 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 121 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Tanzania | 2663 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 122 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Uganda | 2652 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 123 | COVID-19 on Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Zambia | 790 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 124 | Survey on the impacts of COVID-19 on Pastoralist communities | ILRI | 8/1/2020 | Kenya | 100 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 125 | Survey on the value of ICT during COVID-19 | Georgia State Universisty | 9/1/2020 | Ghana | 2019 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 2-Mar-21 | https://economicsobservatory.com |

| 126 | Covid-19 on the distribution of youth-led businesses | University of Exeter | 12/1/2020 | Kenya | 1000 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 127 | WB Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 5/1/2020 | Togo | 2189 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov-22 | https://www.worldbank.org |

| 128 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 6/1/2020 | Burkina Faso | 1356 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 129 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 6/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 1329 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 130 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 5/1/2020 | Ghana | 1633 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 131 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 6/1/2020 | Rwanda | 1482 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 132 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 5/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 1304 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 133 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 5/1/2020 | Uganda | 1250 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 134 | The RECOVR survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 6/1/2020 | Zambia | 1278 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 135 | Vegetable value chain survey | IFPRI | 5/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 433 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 16-Feb-21 | http://essp.ifpri.info |

| 136 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Angola | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 137 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Benin | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 138 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Burkina Faso | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 139 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Cameroon | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 140 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Central African Republic | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 141 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Chad | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 142 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 143 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Congo, Rep. | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 144 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 145 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 146 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Guinea | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 147 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 148 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Liberia | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 149 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Madagascar | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 150 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Malawi | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 151 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Mali | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 152 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Mauritania | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 153 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Mozambique | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 154 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Niger | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 155 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 156 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Sierra Leone | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 157 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Somalia | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 158 | COVID-19 follow-up phone survey | Uni-Bonn-ILR | 6/1/2020 | Namibia | 430 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | http://www.ilr.uni-bonn.de |

| 159 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Tanzania | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 160 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Zambia | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 161 | Hunger and COVID 19 tracking survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 4/1/2020 | Zimbabwe | 896 | yes | yes | no | yes | yes | 1-Nov-21 | https://hungermap.wfp.org |

| 162 | Young Lives phone survey Young | University of Oxford, Young Lives | 6/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 2500 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | https://beta.ukdataservice.ac.uk |

| 163 | Changes in Norms about Social Distancing | University of Michigan & IPA | 7/1/2020 | Mozambique | 2415 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 164 | Addis Ababa Covid19 phone survey | IFPRI | 5/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 600 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 01. Oct 21 | https://economicsobservatory.com |

| 165 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 107 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 166 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Ghana | 110 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 167 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Kenya | 100 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 168 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Malawi | 114 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 169 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Nigeria | 111 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 170 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Tanzania | 102 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 171 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 6/1/2020 | Zimbabwe | 107 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 172 | APRA COVID-19 Rapid Assessment | APRA, Future Agricultures Consortium (FAC) | 10/1/2020 | Zambia | 115 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 01. Oct 21 | https://opendocs.ids.ac.uk |

| 173 | Cash transfers and COVID-19 | IDInsight | 7/1/2020 | Uganda | 633 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 4-Oct-21 | https://www.idinsight.org |

| 174 | Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (CRAM) | University of Stellenbosch, UCT & Wits | 5/1/2020 | South Africa | 10,000 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 4-Oct-21 | https://cramsurvey.org/ |

| 175 | COVID-19 and food insecurity in Cameroon | University of Douala, Cameroon. | 3/1/2020 | Cameroon | 487 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 04. Oct 2021 | https://gsconlinepress.com |

| 176 | WB High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank | 4/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 3896 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 04. Oct 21 | https://osf.io/wvf7m/ |

| 177 | WB High Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS) | The world Bank | 6/1/2020 | Burkina Faso | 1968 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 30-Sep-21 | www.worldbank.org |

| 178 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Ghana | 1000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 179 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 1000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 180 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Nigeria | 1800 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 181 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Rwanda | 1000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 182 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | South Africa | 1000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 183 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Uganda | 1200 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 184 | COVID-19 Livelihoods Impact Tracking Survey | FinMark Trust & insight2impact facility | 4/1/2020 | Zambia | 1000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | March 20,2021 | https://covid19tracker.africa/ |

| 185 | COVID-19 Phone Survey in Senegal | Center for Global Development (CGD) | 4/1/2020 | Senegal | 1023 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 1-Nov-21 | http://crdes.sn/ |

| 186 | Escaping Poverty—COVID-19 Phone Survey | Northwestern University | 9/1/2020 | Ghana | 7330 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 16-Feb-21 | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 187 | WB Household Monitoring Survey (HMS) | The World Bank | 4/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 800 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://worldbank.org |

| 188 | Impacts of the COVID-19 crises on rural household | European Commission JRC | 5/1/2020 | Cote d’Ivoire | 1547 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | |

| 189 | Survey on knowledge and behaviors related to COVID-19 | NA | 4/1/2020 | Malawi | 619 | yes | yes | no | no | no | March 31 2021 | https://demographic-research.org |

| 190 | The effect of COVID on households | NA | 4/1/2020 | Morocco | 2350 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | March 31 2021 | https://www.hcp.ma |

| 191 | Survey of households and frims in Kenya | NA | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 2000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 192 | Survey on the impact of cash in a crisis | NA | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 800 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://economicsobservatory.com |

| 193 | Survey on the impact of cash in a crisis | NA | 4/1/2020 | Uganda | 600 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://pedl.cepr.org/ |

| 194 | community-led WASH Survey | NA | 6/1/2020 | Congo, Dem. Rep. | 1328 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://poverty-action.org/ |

| 195 | Survey of Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Benin | 515 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 196 | Survey of Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Cameroon | 366 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 197 | Rapid Multi-Country Survey on the Impact of the COVID-19 | PARG | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 973 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://precisiondev.org |

| 198 | Secondary Education and Coping with a Pandemic | NA | 5/1/2020 | Ghana | 682 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 199 | Survey on Cash and Compliance with Social Distancing | NA | 6/1/2020 | Ghana | 1500 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 200 | COVID-19, Gender, and Youth Employment in Kenya | NA | 12/1/2020 | Kenya | 2000 | yes | no | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 201 | Digital Credit Usage & Intra-household Bargaining Patterns | NA | 4/1/2021 | Kenya | 7836 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 202 | Parent-Child Preferences and Secondary School Choice | UC Berkele | 3/1/2020 | Kenya | 2973 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 203 | Resilience to economic shocks through continued electricity access | UC Berkele | 12/1/2020 | Kenya | 2000 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 204 | Understanding Effects and Resilience | UC Berkele | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 1008 | yes | yes | yes | no | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 205 | The Effects of a Universal Basic Income | MIT | 6/1/2020 | Kenya | 8605 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 206 | Cash Transfers During a Pandemic | Arizona State University | 4/1/2020 | Kenya | 753 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 207 | Kenya rapid phone-based surveys | Population counsil | 3/1/2020 | Kenya | 2009 | yes | no | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 208 | Kenya rapid phone-based surveys | Population counsil | 7/1/2020 | Kenya | 6853 | yes | no | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 209 | Resilience & Risk in the Informal Sector | Stanford University | 5/1/2020 | Nigeria | 868 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://www.poverty-action.org |

| 210 | Survey of Low-Income Customers of Social Enterprises | 60 Decibels | 4/1/2020 | Togo | 630 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 19-Oct-21 | https://app.60decibels.com |

| 211 | Entrepreneurship Education in Uganda | UC Berkeley & Educate | 9/1/2020 | Uganda | 1916 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 212 | COVID-19 Shock on the youth | Center for Effective Global Action (CEGA) | 5/1/2020 | Uganda | 1920 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://poverty-action.org |

| 213 | Collective Action of School Leaders during Coronavirus Pandemic | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) & Elevate | 5/1/2020 | Uganda | 88 | no | no | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://poverty-action.org |

| 214 | Community Health Care and COVID-19 Pandemic | Trinity College Dublin & Stockholm University | 6/1/2020 | Uganda | 2000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 215 | Vulnerability and Trust in the Aftermath of COVID-19 | Columbia University | 6/1/2020 | Uganda | 2700 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://wzb-ipi.github.io |

| 216 | Public Health, Trust, and Livelihoods | Brown University | 7/1/2020 | Uganda | 2587 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://cega.berkeley.edu |

| 217 | Randomized Impact Evaluation | Northwestern University & IPA | Uganda | 6631 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org | |

| 218 | Consumer Protection Survey | Innovation for poverty action (IPA) | 5/1/2020 | Uganda | 830 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 219 | Peer Messaging to Reduce Covid-19 Transmission | NA | 6/1/2020 | Zambia | 2000 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 220 | Household survey and COVID-19 follow-up phone survey | Uni-Bonn-ILR | 6/1/2020 | Kenya | 654 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | http://www.ilr.uni-bonn.de |

| 221 | Household survey and COVID-19 follow-up phone survey | Uni-Bonn-ILR | 6/1/2020 | Tanzania | 680 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | http://www.ilr.uni-bonn.de |

| 222 | Rural household phone survey | IFPRI | 8/1/2020 | Nigeria | 501 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 21-Nov | https://dataverse.harvard.edu |

| 223 | Phone farm survey about the impact of COVID-19 | ICARDA | 5/1/2020 | Tunisia | 100 | yes | yes | no | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://data.mel.cgiar.org |

| 224 | Stemming Learning Loss During the Pandemic | Columbia University & Young love | 5/1/2020 | Botswana | 4500 | no | no | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://socialscienceregistry.org |

| 225 | COVID-19 Household Impact Survey | World Food Program (WFP) | 5/1/2020 | Algeria | 517 | yes | yes | yes | yes | no | 21-Nov | https://docs.wfp.org |

| 226 | CDC-Africa public opionion survey | CDC Africa | 10/1/2020 | Ethiopia | 1001 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://africacdc.org |

| 227 | CDC-Africa public opionion survey | CDC Africa | 11/1/2020 | Kenya | 1000 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://africacdc.org |

| 228 | CDC-Africa public opionion survey | CDC Africa | 9/1/2020 | Morocco | 1000 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://africacdc.org |

| 229 | CDC-Africa public opionion survey | CDC Africa | 9/1/2020 | Tunisia | 1000 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://africacdc.org |

| 230 | Fever survey | Mauritious statistical office | 4/1/2020 | Mauritius | 1042 | no | no | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://reliefweb.int |

| 231 | COVID-19 on poverty and living standards | University of Cape Coast | 6/1/2020 | Ghana | 900 | yes | yes | yes | yes | yes | 21-Nov | https://www.tandfonline.com |

| 232 | IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON YOUNG WOMEN | ActionAid | 8/1/2020 | Ghana | 305 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://actionaid.org |

| 233 | IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON YOUNG WOMEN | ActionAid | 8/1/2020 | Kenya | 200 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://actionaid.org |

| 234 | IMPACT OF COVID-19 ON YOUNG WOMEN | ActionAid | 8/1/2020 | South Africa | 300 | yes | yes | no | no | no | 21-Nov | https://actionaid.org |

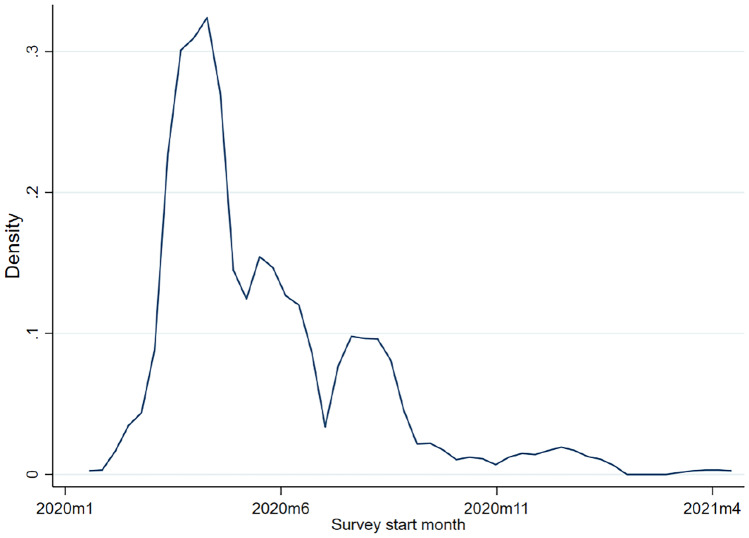

Panel A of Table 2 presents the main descriptive characteristics of the phone surveys. Typically, the surveys we identified are medium-sized (~ 1,000 respondents), cover both rural and urban areas (71%), run for 2 or 3 rounds, collect data for a short period of time (six months or less), focusing on a narrow theme. For a little more than half of the surveys, the unit of analysis are individuals (57%) and the same respondents were contacted repeatedly over time (i.e. panel) (53%). In the review, we included our own study, life with Corona Africa (LwC-A), collecting phone surveys in four African countries — Uganda, Tanzania, Sierra Leone, and Mozambique (see Table 6 in the Appendix for brief description of the survey). About three-quarters of the surveys had been started during the first four months of the beginning of the pandemic between March and June 2020. Over the subsequent periods, the number of ongoing surveys tailed off as existing surveys were phased out and few new surveys were started (Fig. 1).

Table 2.

Description of the phone surveys and the baseline data

| Panel A: Description of Phone surveys | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of surveys | 234 | ||

| Median number of respondents per survey | 1,001 | ||

| Average number of rounds per survey | 2.45 | ||

| survey covers a few thematic areas, yes = 1 | 0.55 | ||

| Survey is panel, yes = 1 | 0.53 | ||

| Unit of Analysis | |||

| Household, yes = 1 | 0.42 | ||

| Individuals, yes = 1 | 0.57 | ||

| Others, yes = 1 | 0.01 | ||

| Geographical coverage of surveys | |||

| Urban areas only, yes = 1 | 0.15 | ||

| Rural area only, yes = 1 | 0.13 | ||

| Both urban and rural, yes = 1 | 0.71 | ||

| Survey available for public use, yes = 1 | 0.24 | ||

| Duration of surveys | |||

| 6 months or less | 0.63 | ||

| 6–12 months | 0.25 | ||

| more than a year | 0.12 | ||

| Panel B: Description of baseline data used in phone surveys | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-COVID-19 baseline used, yes = 1 | 0.38 | ||

| Type of baseline used | |||

| One-off specialized surveys, yes = 1 | 0.32 | ||

| Long running panel surveys | |||

| Specialized panel surveys, yes = 1 | 0.27 | ||

| Integrated household panel surveys, yes = 1 | 0.41 | ||

| If no baseline data, underlying sampling frame | |||

| Administrative data, yes = 1 | 0.43 | ||

| Random Digit Dial (RDD), yes = 1 | 0.57 | ||

| Is the underlying sampling frame nationally representative, yes = 1 | 0.29 | ||

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

Table 6.

Description of Life with Corona Africa (LwC-Africa) Survey

| LwC-Africa builds on and complements the global LwC online survey (https://lifewithcorona.org/). The survey is based on country representative samples and allows statistically meaningful and valid comparisons between and within countries across different socio-demographic groups (e.g., age, gender, and place of residence). The survey follows a stratified random sampling method to interview 500 respondents per month per country over 12 months. The questionnaire contains modules on COVID exposure and experiences on a wide range of topics, including economic, health, social, psychological, and political issues. Specifically, the questionnaire contains the following six modules: (i) household demographic characteristics; (ii) Coronavirus exposure; (iii) Economic well-being, financial insecurity, coping mechanisms, and external support; (iv) Social capital; (v) Food and nutrition security; and (vi) Mental health and wellbeing. It also allows geospatial matching with secondary data sources. |

Fig. 1.

Distribution of phone surveys by starting time (month).

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

Panel B of Table 2 presents a description of baseline data used for COVID-19 related phone surveys in Africa. Three major types of baseline survey data are distinguishable. The first type is one-off specialized surveys, typically undertaken before the pandemic for other studies (e.g. rural household surveys conducted by IFPRI) and later adapted to assess the impact of the pandemic. The second type is long-term specialized panel surveys. These are long-running panel surveys specialized by their thematic area or spatial focuses (e.g. the Feed the Future (FtF); the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP); the Young Lives surveys; Integrated Household Budget Survey). The third type is general-themed, long-running, and integrated household panel surveys. Living Standard Measurement Studies (LSMS); Household Integrated Panel Surveys (HIPS); Life Panel Surveys and the National Income Dynamics Study (NIDS) are the most popular in this category.

When relevant baseline data is not available, two other types of sampling frames are commonly used for phone surveys in lower-income settings. The first is the use of lists of phone numbers, for example from a mobile network operator or contact details of beneficiaries of a program. Another option is to use phone numbers created through random digit dialing (RDD). These two methods jointly account for about 60% of the sampling frame used in phone surveys. Between the two, RDD is slightly more used (Table 2, Panel B).

Review of phone surveys

In this part, we concentrate our review on five key dimensions, namely the topical, temporal, and geographic dimensions as well as geospatial coding and open access of the data. These are dimensions that a survey should accommodate to adequately inform the pattern in the evolution and the socio-economic impacts of and responses to the pandemic (Gourlay et al., 2021; Kühne et al., 2020; Stojetz et al., 2022).

-

(A)

Topical dimension

The identified phone surveys vary widely in terms of the topical areas covered. Table 3 shows that survey modules related to COVID-19 exposure and food (in)security are the two most common ones. COVID-19 exposure is typically assessed based on simple yes/no answers to such questions as “whether the respondents think they or somebody they know had COVID-19”. Another related module common among the phone surveys is on adherence to public health and social measures (PHSMs). Many of these involve data collections that elicit information on how much respondents followed hygiene and social distance measures such as hand washing, avoiding large gatherings and wearing face masks.

Table 3.

Contents of phone surveys

| Survey includes COVID exposure indicator, yes = 1 | 0.97 |

| Survey includes Public Health & Social distancing measures, yes = 1 | 0.71 |

| Survey allows merging with external data, yes = 1 | 0.39 |

| Survey includes food security indicator, yes = 1 | 0.99 |

| Food security standardized, yes = 1 | 0.66 |

| Included food security measures | |

| Food Consumption Score (FCS), yes = 1 | 0.18 |

| Food gap, yes = 1 | 0.60 |

| Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), yes = 1 | 0.28 |

| Access to food, yes = 1 | 0.97 |

| Multiple Food security measures included, yes = 1 | 0.34 |

| Other welfare measures included | |

| Employment status, yes = 1 | 0.66 |

| Income change, yes = 1 | 0.79 |

| Access to services, yes = 1 | 0.59 |

| Mental health, yes = 1 | 0.22 |

| Coping mechanisms, yes = 1 | 0.74 |

| Survey includes all the above welfare measures, yes = 1 | 0.06 |

| Survey includes half or less of the welfare measures, yes = 1 | 0.45 |

| Observations | 234 |

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

From among the 234 phone surveys included in the review, 231 (or 98.7%) of them include some indicators of food security, such as changes in income or access to the food market due to the pandemic.6 While most of these questions provide useful insight, not all of them reflect real changes in food security (Cafiero et al., 2018). Table 3 shows that only 66% of all surveys contain standardized modules on food security such as the Food Insecurity Experience Scale (FIES), Food Consumption Score (FCS), or the number of months of food shortage (food gap). Access to food, or the lack thereof, is the most commonly used food security module (97%) followed by food gap (60%). FCS and FIES are less frequently used perhaps because they require adding a relatively large number of questions (cf. FCS) or they involve questions that are less straightforward or require extensive enumerator training or monitoring (cf. FIES). The number of surveys that include multiple food security measures is even lower (34%).

Other commonly surveyed welfare measures include changes in employment status (66%), income changes (79%), access to services such as drinking water and health services (59%) and coping mechanisms (74%). Less than a quarter of surveys included mental health questions. This is despite the significant increase in mental health issues since the onset of the pandemic (Abreu et al., 2021; Brülhart et al., 2021). Furthermore, Table 3 shows that the surveys are limited in terms of comprehensiveness. While a clearer understanding of the pandemic requires survey data that cover multiple welfare and behavioral dimensions, more than half of the phone surveys we reviewed mostly focus on a narrow theme (e.g. only one dimension of food security or only the health impact of COVID-19 exposure).

-

(B)

Temporal dimension

Given its comprehensive nature, the full impact of the pandemic might not be apparent in the short term based on one-shot surveys (IFPRI, 2020). To be more useful for research, phone surveys need to be collected throughout the pandemic, covering periods of lockdowns and infection peaks and allow comparison before, during and after. However, Table 2 indicates that about half of the phone surveys are cross-sectional and hence are less useful to assess the evolution, the responses to, and the socioeconomic impacts of the pandemic over time. Even when the surveys are repeated, they typically do not last more than 3 rounds. The average number of survey rounds is 2.5. For about 63% of the surveys, the duration of the surveys – the number of months between the start and end of the survey – is less than 6 months. Only 12% of the surveys cover more than a year (Table 2).

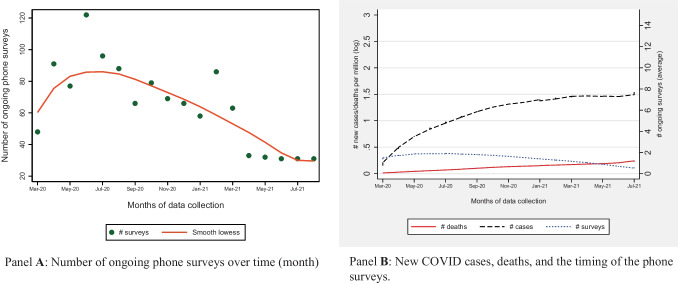

Furthermore, Panel A of Fig. 2 shows that the number of ongoing surveys has continuously been declining. Between March and June 2020, the number of surveys was growing and in June 2020, 120 different surveys were in progress in the continent. Since June, the size has been declining persistently to reach about 30 by the end of the year. Panel B further shows that the number of ongoing surveys has continuously been declining regardless of the progression of the pandemic.

-

(III)

Geographic dimension

Fig. 2.

Patterns in new COVID cases, deaths, and number of ongoing phone surveys over time.

Sources: Data on new COVID cases and deaths are extracted from ourworldindata.org; the total and average number of ongoing phone surveys is computed from data compiled by the authors

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent lockdowns and social distancing measures have largely halted in-person surveys. As a result, following the onset of the pandemic, phone-based surveys became the main, often the only, alternative source of data in most countries in Africa (Gourlay et al., 2021). Given the uncertainty that accompanied the pandemic, phone surveys appeared critical to fully understand, manage and mitigate the human, social and economic effects of the shock. However, the distribution of the phone surveys is highly uneven. Kenya is the most surveyed country in the continent accounting for 11.5% of all phone surveys, amounting to more than 15.3% of all interviews (Table 4). The top five surveyed countries — Kenya, Ghana, Uganda, Ethiopia, and South Africa — account for more than 35% of all surveys and more than 40% of interviews, while accounting for only about 20% of the continent’s population. Other frequently surveyed countries include Nigeria, Malawi, Zambia, and Tanzania. These nine countries account for more than half of the phone surveys related to COVID-19 and food security. The picture remains the same regardless of the measure of survey intensity used – number of surveys, survey rounds, number of respondents, or number of interviews conducted (Table 4).

Table 4.

The distribution of phone surveys across countries

| Surveys | Surveys rounds | Respondents | Interviews | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Countries | Number | Share (%) | Number | Share (%) |

Number | Share (%) |

Number | Share (%) |

| Kenya | 27 | 11.5 | 68 | 11.9 | 61,622 | 15.1 | 121,247 | 15.3 |

| Uganda | 20 | 8.5 | 49 | 8.6 | 41,146 | 10.1 | 67,078 | 8.5 |

| Ghana | 17 | 7.3 | 30 | 5.2 | 28,200 | 6.9 | 36,901 | 4.6 |

| Ethiopia | 12 | 5.1 | 41 | 7.2 | 18,750 | 4.6 | 91,432 | 11.5 |

| South Africa | 8 | 3.4 | 19 | 3.3 | 20,388 | 5.0 | 61,783 | 7.8 |

| Nigeria | 12 | 5.1 | 37 | 6.5 | 23,887 | 5.9 | 47,181 | 5.9 |

| Malawi | 7 | 3.0 | 24 | 4.2 | 7,937 | 1.9 | 29,841 | 3.8 |

| Tanzania | 9 | 3.8 | 22 | 3.8 | 13,075 | 3.2 | 13,279 | 1.7 |

| Zambia | 10 | 4.3 | 20 | 3.5 | 16,598 | 4.1 | 19,281 | 2.4 |

| Others | 112 | 47.9 | 263 | 45.9 | 175,974 | 43.2 | 305,706 | 38.5 |

| Total | 234 | 100 | 573 | 100 | 407,577 | 100 | 793,729 | 100 |

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

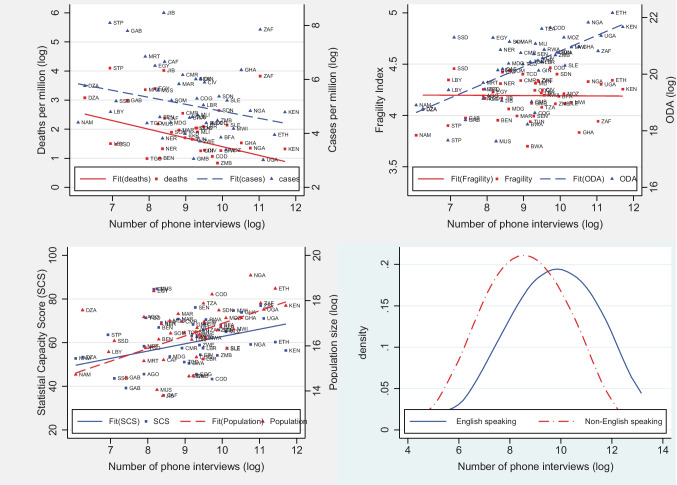

What may explain the uneven distribution of phone surveys across African countries? To answer this, we investigated the simple bivariate correlations between survey intensity and factors that are broad indicators of the perceived costs or ease of conducting research. These factors include population size, statistical capacity score (SCS), official development assistance (ODA), Fragile State Index (FSI), COVID-19 caseloads and deaths, and the use of English as an official language. We identified these factors from previous literature that looked at the distribution of research across African countries and beyond (Das et al., 2013; Porteous, 2020; Robinson et al., 2006).

We derived data on these indicators from multiple sources. Data on population size, SCS, and ODA are extracted from the World Development Indicators at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator. SCS is a composite score on a scale of 0-100 assessing the capacity of a country’s statistical system on methodology, data sources, and periodicity and timeliness7. ODA consists of disbursements of loans made on concessional terms and grants by official agencies of the members of the Development Assistance Committee (DAC), multilateral institutions, and non-DAC countries. FSI is generated and made available by the Fund for Peace (FFP). It summarizes the economic and political instability of countries based on 12 conflict risk indicators8. COVID-19 caseloads and deaths refer to the number of COVID-related cases/deaths corresponding to the first three months of the pandemic, and are extracted from: https://ourworldindata.org.

Generally, one might expect differences in resources or COVID cases and deaths to drive survey locations. However, a pairwise correlation result presented in Table 8 in the appendix indicates that this is not the case (also see Fig. 3, top left panel)9. Instead, survey location choices are related to the size of the country (population size) and the availability of pre-existing data or indeed statistical capacity (SCS) (bottom left panel). Figure 3 also shows that phone surveys are less (more) correlated with fragility index (net official development assistance (ODA) (top right panel). Finally, the bottom right panel shows that phone surveys are more prevalent in countries with English as an official language, which is consistent with other studies (Porteous, 2020).

Table 8.

Pairwise correlation between survey intensity indicators and sociodemographic characteristics in Africa

| COVID cases per million | COVID deaths per million | GDP per capita | Access to electricity | Mobile subscription | Statistical Capacity Score | Fragility Index | Population | ODA | # surveys | # surveys rounds | # respondents | # interviews | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| COVID cases per million | 1 | ||||||||||||

| COVID deaths per million | 0.90 | 1 | |||||||||||

| GDP per capita | 0.20 | 0.24 | 1 | ||||||||||

| Access to electricity | 0.40 | 0.42 | 0.72 | 1 | |||||||||

| Mobile subscription | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.63 | 0.71 | 1 | ||||||||

| Statistical Capacity Score | 0.01 | 0.13 | -0.06 | 0.19 | 0.31 | 1 | |||||||

| Fragility Index | -0.22 | -0.21 | -0.68 | -0.58 | -0.64 | -0.41 | 1 | ||||||

| Population size | -0.14 | -0.06 | -0.06 | 0.08 | -0.06 | 0.15 | 0.22 | 1 | |||||

| ODA | -0.27 | -0.27 | -0.34 | -0.18 | -0.25 | 0.13 | 0.38 | 0.76 | 1 | ||||

| # surveys | -0.17 | -0.23 | -0.22 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.23 | 0.05 | 0.42 | 0.62 | 1 | |||

| # surveys rounds | -0.20 | -0.26 | -0.28 | -0.09 | -0.02 | 0.21 | 0.13 | 0.50 | 0.70 | 0.96 | 1 | ||

| # respondents | -0.13 | -0.16 | -0.17 | 0.03 | 0.09 | 0.16 | 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.56 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 1 | |

| # interviews | -0.08 | -0.09 | -0.15 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.18 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.67 | 0.87 | 0.93 | 0.90 | 1 |

Sources: data on COVID caseloads and deaths are extracted from ourworldindata.org; data on GDP, ODA, population size, access to electricity, and mobile subscription are from World Development Indicators, World Bank (2022); Fragility index is from Fund for Peace (FFP); total and average number of ongoing phone is computed from data compiled by the authors

Fig. 3.

Correlates of phone survey intensity in Africa.

Notes: The fit line is from a linear regression of the number of interviews (log) on population (log), statistical capacity score (SCS), net official development assistance (ODA) (log), fragile state index (FSI), and number of COVID related cases/deaths.

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

The use of representative and up-to-date pre-pandemic baseline data as a sampling frame in phone surveys is vital to correct the biases associated with the sample selection process (Ambel et al., 2021). In line with this, 39% of all phone surveys and 73% of panel surveys in our review used pre-pandemic face-to-face survey datasets as a baseline. When used, the preferred baseline data are large-scale, representative, long-running, and integrated panel surveys (Panel B, Table 2). However, since the pre-pandemic distribution of large-scale datasets across African countries is highly uneven (Porteous, 2020), this has led to a significant disparity in data collected during the pandemic as shown above.

-

(D)

Geospatial coding

One of the downsides of using a phone survey, compared to alternative ways of data collection, is that it allows for limited sets of questions to be included. Fortunately, there is large useful and open access information (e.g. diseases statistics, government measures, public goods, price trends, conflicts, weather data, etc.) that can be extracted and spatially and temporally matched with survey data. To take advantage of this, a few phone surveys include either location information or use baseline data that already collected GPS information. However, this is not widespread. In our review, only 39% of the surveys include such information (Table 3).

-

(E)

Open access of the data

Another desirable, yet largely missing, quality of phone surveys is the availability of the resulting data as open access for public use. While this enables widespread use of the data, it would also allow pooling across surveys in cross-country analyses. Regardless, only 24% of the phone surveys are currently available for public use (Table 2). Eight (~ 3.42%) other surveys are not yet open access but indicated that the corresponding data will become open access in the future. For the remaining others, we are unable to find information to determine if they will become open access or not. The most popular of the open access data is from the World Bank data portal, based on which the Bank creates harmonized indicators and disseminates through High-Frequency Monitoring Dashboard.10

To summarize and further elaborate on the above five dimensions, we generated an index representing the pooling potential of the reviewed phone surveys based on 14 selected survey and questionnaire features, each of which is coded as a binary variable that takes a value of 1 if desirable, 0 otherwise. The index, thus, ranges from zero to 14. The selected 14 survey and questionnaire features include, (i) survey is panel; (ii) survey involves continuous data collection; (iii) survey data available for public use; (iv) survey sample is large (greater than 1000 respondents); (v) questionnaire includes standardized food security questions; (vi) questionnaire include change in employment; (vii) questionnaire includes change in income; (viii) questionnaire includes access to services; (ix) questionnaire includes mental health questions; (x) questionnaire includes coping mechanisms; (xi) survey allows merging with external data; (xii) survey uses pre-crisis baseline data; (xiii) pre-crisis baseline is representative and (xiv) survey covers both urban and rural areas.

In our study, this indicator takes an average overall value of 6.8 (out of the possible 14 points), suggesting that many studies do not fulfill the requirements which would allow pooling across surveys (Fig. 4). Furthermore, the right-hand side graph indicates that this quality of phone surveys is positively correlated with the number of interviews suggesting that less studied countries are disadvantaged not only in terms of survey intensity but also in terms of pooling potential to study cross-regional and cross-country issues.

Fig. 4.

Pooling potential of phone survey (right) and correlation with survey intensity in Africa (right).

Source: Computed from data compiled by the authors

Discussion

Our review of phone surveys in Africa during the COVID-19 pandemic provides several interesting insights. First, we find that the distribution of phone surveys in the continent is highly uneven - and systematically so. The variation across countries is strongly related to factors that are broad indicators of the perceived costs or ease of research (population size, inflow of aid, statistical capacity, and fragility of economies) rather than the potential benefits to the communities (e.g. Coronavirus incidence). Since the distribution of data was already uneven before the pandemic, and that design of quality phone surveys benefits from the availability of representative and up-to-date pre-pandemic data (Ambel et al., 2021), COVID-19 may have perpetuated (or even exacerbated) the existing uneven distribution of data between countries in Africa. Since the uneven distribution of data implies an uneven distribution of research (Brück et al., 2014), which in turn translates into an uneven evidence base for policy-makers (Porteous, 2020), we call on the scientific community to focus further research on locations where the evidence base is thin. Policymakers in less researched areas could also help attract more research by improving their statistical capacity, openness, and governance.

Our review indicates that the current intensity of data collection is strongly influenced by past scores of statistical capacity. Indeed, countries that were able to rapidly launch phone surveys at the beginning of the pandemic were those with long-term and representative pre-pandemic data that serves as a sampling frame as well as with up-to-date information and communication technology (ICT) infrastructure for the implementation of longitudinal household surveys (Gourlay et al., 2021; UNDESA and World Bank, 2020). This suggests that countries should invest in ICT infrastructure, particularly on National Statistical Offices (NSOs) to provide them with reliable internet access and computer hardware and software for data collection, storage, and processing.

Second, our results demonstrate that the existing surveys mostly focus on a narrow theme and only some of them allow for heterogeneous analysis across socioeconomic, spatial, and intertemporal dimensions. Most surveys focus on food security (even if not measured consistently), employment, and income losses. Non-economic aspects such as the interaction with or the impact of the pandemic on mental health, social capital, trust, governance, and intra-household relationships are not fully accommodated. As these are important correlates of household welfare and are significantly affected by the pandemic (Brooks et al., 2020; Ravens-Sieberer et al., 2021), their exclusion from surveys could lead to an underestimation of the impact of the pandemic.

Third, most of the surveys were designed as short-term projects. While it has so far been natural to focus on the pandemic’s short-term impact, it is also critical to monitor how the pandemic unfolds and assess its implications for medium- and long-term food security to inform policy decisions. For instance, the large-scale countermeasures implemented in most countries have changed patterns in education attendance, consumption, and household labor allocation (IFPRI, 2020). While the short-term effects of these changes are profound, they are also likely to determine the speed of recovery and the long-term growth trajectory of affected households and countries. Furthermore, it is not yet clear whether and how these COVID-shaped trajectories may interact with existing vulnerabilities such as old age, household size, income sources, or poverty.

Fourth, only 24% of the phone surveys are available for public use. This constraints widespread distribution and use of the data to support research-based policy solutions. Even when the data are available, the idiosyncratic nature of many surveys prevents meaningful pooling of surveys across Africa, closing an avenue of learning open to standardized surveys like DHS, LSMS, or MICS. Furthermore, it is relatively less common for researchers and statistical offices in Africa to register their surveys and projects in international registries. This reduces the potential synergies among different projects from harmonization of survey instruments. A widespread registry of surveys also helps to identify and draw attention to relatively understudied areas and topics.

Finally, due to a lack of geospatial information or alternative location information, most surveys are not suitable for matching with secondary sources of information on, inter alia, diseases statistics, government measures, price trends, conflicts, or weather data, reducing the scope for multidisciplinary research around the pandemic.