Abstract

We recently determined that passive transfer of serum directed against a synthetic peptide called LB1 or a recombinant fusion protein immunogen [LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3] could prevent otitis media after challenge with a homologous nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) isolate. NTHI residing in the nasopharynx was rapidly cleared from this site, thus preventing it from ascending the eustachian tube and inducing otitis media in chinchillas compromised by an ongoing viral upper respiratory tract infection. While LB1 is based solely on one NTHI adhesin, the latter immunogen, LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3, was designed to incorporate two NTHI antigens shown to play a role in the pathogenesis of otitis media; lipoprotein D (LPD) and the P5-homologous fimbrin adhesin. The design of LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 also accommodated for the recently demonstrated existence of three major groupings, based on amino acid sequence diversity, in the third surface-exposed region of P5-fimbrin. LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 was thus designed to potentially confer broader protection against challenge by diverse strains of NTHI. Chinchillas were passively immunized here with serum specific for either LB1 or for LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 prior to challenge with a member of all three groups of NTHI relative to diversity in region 3. The transferred serum pools were also analyzed for titer, specificity, and several functional activities. We found that both serum pools had equivalent ability to mediate C′-dependent killing and to inhibit adherence of NTHI strains to human oropharyngeal cells. When passively transferred, both serum pools significantly inhibited the signs and incidence of otitis media (P ≤ 0.01) induced by any of the three challenge isolates. Despite providing protection against disease, the ability of these antisera to induce total eradication of NTHI from the nasopharynx was not equivalent among NTHI groups. These data thus suggested that while early, complete eradication of NTHI from the nasopharynx was highly protective, reduction of the bacterial load to below a critical threshold level appeared to be similarly effective.

Our laboratory has focused on a specific 19-mer portion of the outer membrane protein (OMP) P5-homologous fimbrin adhesin (P5-fimbrin) of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) as a potential protective antigen. This region of the adhesin protein resides in the third of four predicted surface exposed areas of the mature 36.4-kDa protein and served as the basis for the design of a synthetic chimeric 40-mer peptide immunogen known as LB1 (5). LB1 proved to be highly efficacious as an immunogen in chinchilla models, inducing antibody that (i) significantly augmented the clearance of NTHI from the colonized nasopharynx (NP), (ii) significantly augmented the clearance of NTHI from a directly challenged middle ear, and (iii) (when passively transferred) also protected against ascension of the eustachian tube and development of otitis media (OM) by a homologous challenge isolate in adenovirus-compromised chinchillas (4). Despite the demonstrated efficacy of LB1, however, we were concerned that sequence diversity within this 19-mer region of the adhesin protein [called LB1(f) to distinguish it from the MVF epitope also included in LB1] might limit the protection conferred to homologous challenge isolates.

To that end, 99 clinical isolates of NTHI were subjected to PCR amplification and nucleotide sequencing of the region encoding the 19-mer peptide of the P5-fimbrin protein (4). When the resulting sequencing data were translated and aligned, we found that the strains segregated into three major groups. The N-terminal half of this moiety is highly conserved, while there is increased diversity in the C-terminal half. Of the isolates, 76% belonged to group 1, while 14 to 21% and 3 to 10% belonged to groups 2 and 3, respectively. Group 2 isolates have been further divided into subgroups 2a (10 to 14% of isolates tested) and 2b (4 to 7% of isolates) based on limited but consistent sequence differences. Since organisms expressing these diverse structures were likely to be antigenically distinct, we concluded that peptides representative of this region from each group could perhaps be combined to create a more broadly protective immunogen. Moreover, we were interested in including another “natural,” immunogenic, and potentially protective NTHI OMP in the vaccine design. We thereby incorporated LPD into the vaccinogen since it is an OMP with an innate adjuvant effect (1), it has been shown to be a virulence factor in rat models (14), and it also has been shown to confer some protection in the chinchilla model (4). LPD was thus used as the carrier for three unique sequential LB1(f) fragments, creating the recombinant fusion protein LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3.

We recently tested LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 in a chinchilla passive-transfer model designed to assess the ability of antibodies directed against this immunogen to protect against ascension of the eustachian tube and establishment of OM by NTHI residing in the NP of an adenovirus-compromised host. We found that passive transfer of serum specific for either LB1 or LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 prior to intranasal (i.n.) challenge with a group 1 NTHI strain significantly reduced the severity of signs and incidence of OM that developed. Whereas in the sham-immunized cohort, 80% of the ears developed OM by day 12, with effusions persisting for an additional 12 days; in the cohort that received diluted anti-LB1 serum, the incidence of OM was 15% of the ears, with effusions observed for 1 day only. In the cohort that received diluted anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum, the peak incidence of OM occurred in 23% of the ears, with effusions persisting for an additional 4 days. Antiserum transferred to this latter cohort has subsequently been shown to be more immunoreactive than was anti-LB1 in several in vitro assays against whole OMP preparations from multiple NTHI isolates and against a panel of synthetic peptides derived from all three NTHI groups (18). However, we did not know if this greater reactivity translated into greater protective capability as well. The present study was thereby designed to test the relative breadth of protective efficacy of these immunogens against challenge by prototype NTHI strains representative of each of the three major groupings relative to the diversity noted in the third surface-exposed region of this adhesin.

(These findings were presented in part at the Seventh International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media, June 1–5, 1999, Ft. Lauderdale, Fla.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

We used 172 healthy adult (ca. 450 to 500 g) or juvenile (ca. 300 g) chinchillas (Chinchilla lanigera) with no evidence of middle ear infection by either otoscopy or tympanometry for antibody production or for passive transfer and challenge studies, respectively. The mean weights of the juvenile chinchillas for each of the two passive transfer studies detailed below were 296 ± 38 or 298 ± 42 g, respectively. Animals were rested 10 days upon arrival, and blood was obtained for collection of preimmune serum that was stored at −70°C until use.

NTHI and adenovirus isolates.

All NTHI strains used were limited-passage clinical isolates cultured from children who underwent tympanostomy and tube insertion for chronic OM with effusion at Columbus Children's Hospital. These isolates and their grouping relative to the described sequence diversity in region 3 of P5-fimbrin that is incorporated into LB1 [and referred to as peptide LB1(f)] (4) were strain 86-028NP (group 1), strain 1885MEE (group 2a), and strain 1728MEE (group 3). These isolates have been characterized in chinchilla models of OM (4, 5, 8, 11, 17, 21, 22) and have been maintained frozen in skim milk plus 20% (vol/vol) glycerol. Due to the propensity for strains 86-028NP and 1885MEE to autoagglutinate when used in adherence and bactericidal assays in vitro, to obtain more consistent interassay results, we substituted strain 86-028L, isolated from the left ear of the same child, or strain 266NP, respectively, in these assays. Both strains 86-028L and 266NP share identical LB1(f) amino acid sequences with the strains they are replacing (4). Adenovirus serotype 1 was also recovered from a pediatric patient at Columbus Children's Hospital and has been used in chinchilla models (2, 3, 6, 22).

Immunogens used.

LB1 is a 40-mer synthetic chimeric peptide comprised of a 19-mer B-cell epitope of P5-fimbrin [LB1(f)], a small linker peptide and a C-terminal T-cell promiscuous epitope from measles virus fusion protein. It has been described elsewhere (4, 5). LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 is a recombinant fusion protein comprised of an N-terminal LPD moiety followed by three sequential LB1(f) peptides, each separated by a short linker peptide, and a C-terminal polyhistidine purification tag. The three LB1(f) peptides represent (in order) group 2a, group 1, and group 3 sequences. This immunogen and the rationale for its design have been reported (4).

Production of antisera for passive transfer.

Two cohorts of 20 chinchillas each were used to generate antisera. One cohort was immunized with LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 (10 μg/dose) delivered in a combined adjuvant formulation of AlPO4 plus monophosphoryl lipid A (MPL) (Ribi ImmunoChem Research, Inc., Hamilton, Mont.) (200 μg of AlPO4 and 20 μg of MPL per dose), followed by two identical boosts at monthly intervals. The second cohort received LB1 (10 μg/dose) delivered in complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA; Sigma), followed by two monthly boosts in incomplete Freund's adjuvant (IFA; Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.). All doses were delivered subcutaneously in a 200-μl total volume. Animals were bled 10 days after receiving the final boost, and sera were then pooled by cohort for passive transfer to juvenile animals.

Passive transfer study.

Due to the large cohort sizes, we divided these studies into two parts (A and B) with sham-treated controls repeated in each study to ensure the accuracy of statistical comparison between sham and immune cohorts within a given study. Sixty-six juvenile chinchillas were thereby used in each study to establish six cohorts of eleven chinchillas each. Naive sera, collected from each of these animals, were screened individually by Western blotting to detect the presence of any significant preexisting reactivity with NTHI OMPs prior to enrollment of each chinchilla into the study. Seven days before NTHI challenge, chinchillas received 6 × 106 50% tissue culture infective doses of adenovirus serotype 1 i.n. One day prior to bacterial challenge, chinchillas were injected intracardially (5 ml/kg) (9, 21) with one of the two undiluted antiserum pools or with pyrogen-free sterile saline. Two cohorts of 11 animals each thus received the LB1 antiserum pool, two cohorts received the LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 antiserum pool, and two cohorts received pyrogen-free sterile saline. Observers knew neither the antiserum received nor which animals formed a cohort group throughout the 35-day observation period after NTHI challenge.

In study A, three cohorts of chinchillas [one that received saline, one that received anti-LB1, and one that received anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3] were then challenged i.n. by passive inhalation of approximately 108 CFU of NTHI 86-028NP (group 1) per animal. Three identically treated cohorts were challenged with NTHI 1885MEE (group 2a). In study B, similar sham-treated or immune-serum-receiving cohorts were challenged with either strain 86-028NP or strain 1728MEE (group 3). Cohort nomenclature was defined by the immune-serum pool received, followed by the NTHI challenge strain, e.g., LB1/86-028NP for animals receiving anti-LB1 serum by passive transfer followed by i.n. challenge with NTHI strain 86-028NP.

Clinical assessment of experimental disease.

For both studies, animals were blindly evaluated by otoscopy and tympanometry (EarScan, South Daytona, Fla.) daily or every 2 days from the time of adenovirus inoculation until 35 days after NTHI challenge. Signs of tympanic membrane inflammation were rated on a scale of 0 to 4+ (21, 22), and tympanometry plots were used to monitor changes in middle ear pressure, tympanic width, and tympanic membrane compliance (13, 16, 25). Tympanometry results indicated an abnormal ear if (i) a type B tympanogram was obtained, (ii) compliance was ≤0.5 or ≥1.2 ml, (iii) tympanic width was greater than 150 daPa, (iv) or middle ear underpressure was greater than −100 daPa. Clinical signs of viral respiratory tract infection (ruffling of fur, conjunctivitis, altered character of nasal/ocular secretions, wheezing, labyrinthitis, and cornering behavior) were recorded.

An NP lavage was performed on all animals on days 1, 4, 7, 10, 14, 18, 21, 28, and 35 after NTHI challenge by passive inhalation of 500 μl of pyrogen-free sterile saline in 5- to 10-μl droplets through one nare, with collection of this fluid from the contralateral nare as it was exhaled, as previously described (5, 11). Recovered NP lavage fluids were maintained on ice until serially diluted and plated onto chocolate agar containing bacitracin (BBL). Plates were incubated at 37°C for up to 48 h to semiquantitate the CFU of NTHI per milliliter of lavage fluid. Animals were also tabulated as having a “colonized” or “cleared” status based on culture results. If NTHI was cultured, the animal was considered colonized. If a culture-negative status was both achieved and substantiated for an additional 7 to 10 days by plate count, an animal was considered cleared as of the first day it became culture negative. Finally, blood was obtained for serum from all chinchillas 35 days after NTHI challenge.

Assessment of serum titer and/or specificity by ELISA and Western blotting.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed using dilutions of pooled chinchilla serum from each cohort and were assayed against LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3, LB1, or recombinant LPD (rLPD) (0.2 μg/well) in 96-well microtiter plates (Dynatech, Horsham, Pa.) as previously described (4, 5). The titer of a serum pool was defined as the reciprocal of the dilution consistently yielding an optical density at 490 nm value showing a twofold increase over that of wells containing all of the components but immune serum. Median values based on three replicate assays are reported. For determination of specificity of serum reactivity, Western blotting was performed, also as described previously (4, 7), against NTHI whole OMP preparations, LB1, LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3, and rLPD using pooled immune serum diluted 1:100 as the primary antibody and HRP-Protein A (Zymed) diluted 1:200 as the secondary antibody. Color was developed with 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma).

Assessment of functional activities of the induced antibodies. (i) Ability to inhibit adherence of NTHI to human OP cells.

The assay system used has been previously described (21). Briefly, human oropharyngeal (OP) cells collected from healthy adults were washed, diluted to ca. 2.5 × 105 cells/ml, and affixed into each well of a 96-well plate that had been treated with l-lysine and glutaraldehyde. Overnight cultures of NTHI were biotinylated, adjusted to 109 CFU/ml, as confirmed by plate count, and then incubated with serial dilutions of antisera (1:25 to 1:800) or with naive serum (for positive control wells). Bacteria mixed with antisera were visually inspected for agglutination prior to adding to OP cells, and an aliquot from the mixture that included the 1:25 dilution of sera was also plated to confirm that the desired number of CFU of NTHI per milliliter was maintained. Wells were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and NTHI was added prior to incubation for 1 h at 37°C. The plates were washed, and ExtrAvidin (Sigma) was added to each well. ABTS [2,2′-azinobis(3-ethylbenzthiazolinesulfonic acid), 1:100; Zymed] was used as the substrate, and the reaction was stopped with 1.5 N hydrofluoric acid. The absorbancy was read at 405 nm (Bio-Tek Instruments). The percent inhibition of adherence was calculated by subtracting the mean value of the test wells from the mean value of the positive control wells, dividing by the latter value, and then multiplying the result by 100. Both serum pools were assayed against each of the three NTHI isolates a minimum of three times. Mean percent adherence inhibition values ± the standard deviation are presented.

(ii) Bactericidal activity.

NTHI were grown to mid-exponential phase at 37°C in 10 ml of brain heart infusion broth supplemented with 4% Fildes (Difco). The bacteria were then washed and resuspended to 5.0 × 104 CFU/ml PCM buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.15 M CaCl2, 0.5 M MgCl, and 0.5% BSA) before mixing them 1:5 with complement (57 mg/ml, guinea pig whole complement; Calbiochem, La Jolla, Calif.). This NTHI-complement mixture was then added to heat-inactivated serum pools [either anti-LB1 or anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3] that had been serially diluted in 2× PCM buffer followed by incubation for 1 h at 37°C in a shaking water bath. Control mixtures of bacteria without complement or bacteria without serum but with all other components were also prepared. A 50-μl aliquot of each dilution and control preparation was plated in duplicate onto chocolate agar and incubated overnight at 37°C. Colonies were counted, and the reciprocal titer was determined to be that dilution of antiserum that killed ≥50% of the bacteria compared to the appropriate no-serum control.

Statistical methods.

The Biometrics Laboratory of The Ohio State University's College of Medicine and Public Health conducted all statistical analyses on data prior to deblinding the chinchilla cohorts. To confirm that each NTHI strain inoculated had indeed colonized the chinchilla NPs, we tested for a difference among cohorts in CFU of NTHI per milliliter of nasopharyngeal lavage fluid that was collected the day after challenge, using a Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

For analysis of otoscopy data, a repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare the pattern of responses over time (days) for the cohorts. Due to the large number of repeat observations for each animal, the analysis was divided into five sections: days 1 to 7, 8 to 14, 15 to 21, 22 to 28, and 29 to 35. Tukey's test was used for all post-hoc multiple comparisons. Significance was assessed using an alpha level of 0.05.

To test for significant inhibition of development of middle ear effusion, a Z test comparison of proportions was performed on each day the percentage of abnormal ears exceeded 50% in sham-treated animals. Significance was accepted at a P ≤0.01.

A log-rank test was used to compare cohorts for relative time to bacterial clearance of the NP, as determined by culture-negative status, and illustrated with Kaplan-Meier survival analysis curves. Cox proportional hazards regression analysis was additionally performed to further elaborate the differences between the cohorts. An alpha level of 0.01 was accepted as significant.

To test for a correlation between time to clearance and OM versus no OM, a chi-square analysis was performed with the phi coefficient reported as a measure of association (correlation coefficient).

A Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the percent inhibition of adherence for both antiserum pools versus the three NTHI strains. This statistical test was also used to determine if there was a significant difference between these two antiserum pools in their ability to kill NTHI strain 86-028NP.

RESULTS

Characterization of immunogens.

Both immunogens were characterized by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis with silver stain and assessed for purity by laser based densitometry (Bio-Rad) as previously described (4). Purity was 97% for LB1 and 96% for LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 (predominant band) (data not shown). Both immunogens contained less than 0.1% endotoxin content by weight as determined by chromogenic Limulus assay (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.).

Characterization of antisera.

Antisera generated by immunization with LB1 or LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 that were later delivered to chinchillas by passive transfer were characterized by ELISA and Western blotting. Reciprocal serum antibody titers against the immunogens delivered were determined in triplicate for each serum pool (Table 1) and showed that a high-titer and specific response had been elicited against both immunogens. Immunization with LB1 yielded equivalent titers when assayed against both itself and LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 but demonstrated a low titer to rLPD. Immunization with LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 resulted in strong reciprocal titers against both itself and rLPD but demonstrated a low titer to LB1 in this system.

TABLE 1.

Median reciprocal titer of serum passively transferred to chinchillas

| Cohort | Mean reciprocal titer versus:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| LB1 | LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 | rLPD | |

| Anti-LB1 | 5 × 104 | 5 × 104 | 1 × 103 |

| Anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 | 1 × 102 | 5 × 104 | 2 × 104 |

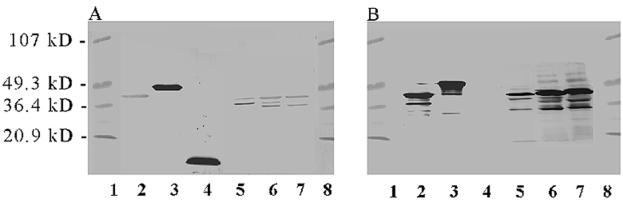

By Western blotting (Fig. 1A), anti-LB1 recognized itself (lane 4), LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 (lane 3), and both the fully and partially denatured species of P5-fimbrin at approximately 37 and 25 kDa, respectively, in whole OMP preparations from all three NTHI challenge isolates (lanes 5 to 7), as we have reported previously (5). Faint recognition of rLPD by anti-LB1 serum (lane 2) and also of a third band migrating between the two P5-fimbrin species in the lane containing whole OMP of strain 1885MEE (lane 6) was likely due to the strong adjuvant (CFA or IFA) enhancing a preexisting immune recognition in these non-specific-pathogen-free animals. In the case of the third band that occurs between the fully and partially denatured P5-fimbrin species in the whole OMP prep of strain 1885MEE, this may also represent a second partially denatured species of P5-fimbrin since we have previously noted similar reactivity when using serum from chinchillas immunized with isolated P5-fimbrin (21).

FIG. 1.

Western blot of serum used for passive transfer. (A) Anti-LB1 serum pool. (B) Anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum pool. Lanes: 1, molecular mass standards; 2, rLPD; 3, LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3; 4, LB1; 5, NTHI 86-028NP whole OMP preparation; 6, NTHI 1885MEE whole OMP; 7, NTHI 1728MEE whole OMP; and 8, molecular mass standards.

Anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 (Fig. 1B) also recognized itself (lane 3) and recombinant LPD (lane 2), as well as a 42-kDa protein (presumed to be LPD) and both species of P5-fimbrin within the whole OMP preparation of all three NTHI strains (lanes 5 to 7), also as we have reported previously (4). While anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 did not recognize the 40-mer chimeric peptide LB1 in the composite blot shown (lane 4), it does recognize LB1 when assayed singly against this peptide by Western blotting (not shown). This phenomenon is likely due to the lower relative concentration or avidity of the anti-group 1 LB1(f) peptide-specific antibodies available in the anti LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum pool, as we have reported previously (4) and also as reflected in the ELISA-determined titers reported above.

Protective activity of passive antiserum delivery versus development of middle ear fluids (effusion).

Of 64 animals enrolled in study A, 59 (92%) completed the study as scheduled (two died prior to inception of the study). In study B, 62 of the 66 enrolled animals (94%) completed the study. All animals in all cohorts of both studies exhibited characteristic signs of adenovirus infection prior to bacterial challenge, including conjunctivitis, tympanic membrane retraction with underpressured middle ears, cornering behavior, and ruffling of fur.

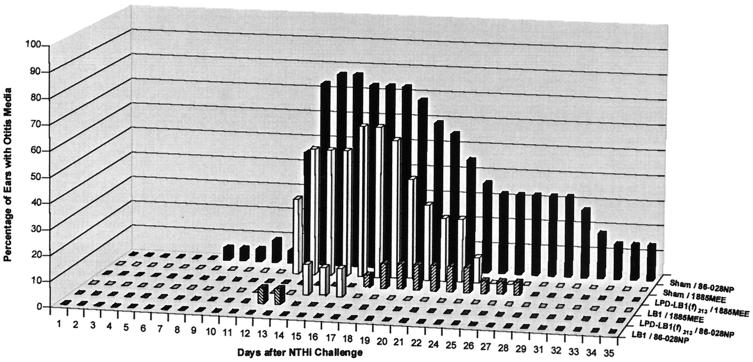

In study A, 5% of the ears (1 of 22) of sham-treated animals were abnormal, beginning 7 days after challenge with strain 86-028NP (Fig. 2). The incidence of OM reached a maximum on days 14 and 15, with 77% of the ears (17 of 22) containing an effusion. Conversely, none of the animals that received anti-LB1 serum developed an effusion after challenge with strain 86-028NP. In the animals that received anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3, only 1 of 17 ears (6%) developed an effusion on days 12 and 13 when they were similarly challenged with 86-028NP.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of ears with OM within each cohort (study A).

Also in study A, in the sham-treated cohort challenged with strain 1885MEE (Fig. 2), 33% (6 of 18) of the ears developed an effusion on day 12, with a peak incidence of OM occurring in 67% (12 of 18) of the ears on days 16 and 17. Effusions had resolved in this cohort 26 days after challenge demonstrating the slightly less “virulent” phenotype of strain 1885MEE relative to strain 86-028NP in this model. In the LB1-1885MEE cohort, the only OM noted occurred in 2 of 15 or in 2 of 16 ears (13%) on days 14 and days 15 and 16, respectively. Only one ear (5%) in the LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–1885MEE cohort contained an effusion on day 17, whereas on days 18 to 24 a maximum incidence of effusion occurred in 2 of 20 ears (10%). Effusions had completely resolved in this latter cohort by day 28.

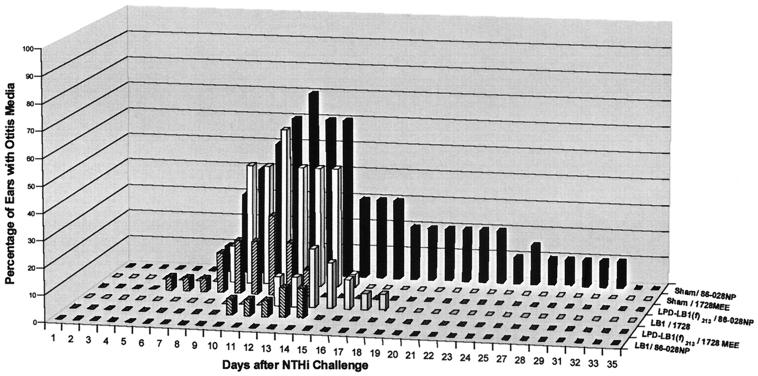

In study B, 10% of the ears (2 of 20) in the sham-treated cohort challenged with 86-028NP, demonstrated an effusion on day 7, and peak incidence of OM occurred on day 12 with 70% of the ears (14 of 20) containing middle ear fluids (Fig. 3). Conversely, as also shown in study A, there were no effusions in any ear of chinchillas immunized with anti-LB1 serum and challenged with strain 86-028NP. In the cohort that received anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum, 1 of 20 ears (5%) had an effusion on day 5, with a maximum incidence of ears containing an effusion occurring 11 days after challenge with 86-028NP in 30% of the ears (6 of 20).

FIG. 3.

Percentage of ears with OM within each cohort (study B).

Also in study B, the sham-treated cohort that was challenged with strain 1728MEE showed 14% (3 of 22) of the ears with an effusion on day 8, reaching a maximum of 59% abnormal ears (13 of 22) on day 11. Effusions were cleared in the sham-1728MEE cohort 16 days after challenge; thus, strain 1728MEE was noted to be the least virulent of the three NTHI isolates tested in this model. In the cohort that received anti-LB1, 11% of the ears (2 of 18) began to demonstrate OM on day 12, with the greatest incidence of OM occurring on day 14 in 4 of 18 ears (22%). Animals receiving anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 showed one ear with an effusion on days 10 to 12 after challenge with 1728MEE. The maximum incidence of OM in this cohort was 11% (2 of 18 ears) and occurred on days 13 and 14.

Comparing the two studies, the three cohorts in study A (sham–86-028NP, LB1–86-028NP, and LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–86-028NP) were immunized and challenged in a manner identical to that of the three cohorts in study B. In both studies, effusions began to develop in sham-treated animals 7 days after challenge with strain 86-028NP. In study A, effusions persisted in 9% of the ears (2 of 22) to the end of the study, 35 days after bacterial challenge. Similarly, in study B effusions persisted in 10% of the ears (2 of 20) for 32 days after bacterial challenge. The peak incidences of effusions were 77 and 70% of the ears in studies A and B, respectively. None of the ears of any animal that received anti-LB1 serum in either study A or study B before being challenged with strain 86-028NP developed an effusion. There was somewhat less consistency between studies A and B in the LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–86-028NP cohorts, however. In study A 6% (1 of 17) of ears developed an effusion that lasted for only 2 days, whereas in study B the identically immunized and challenged cohort demonstrated a peak incidence of 30% of the ears (6 of 20) with OM. These effusions persisted for 9 days. The reasons for the differences observed in this latter cohort between studies A and B, but not in the other cohorts, are not known at this time.

To summarize these data and to indicate the days on which the passive transfer of either serum pool provided significant protection from development of an effusion on each day that 50% or more of the ears in identically challenged sham cohorts contained an effusion, we have compiled the findings for both studies in Table 2. Both antiserum pools provided significant protection against OM induced by NTHI strains 86-028NP, 1885MEE, and 1728MEE.

TABLE 2.

Percent reduction in the presence of middle ear effusions compared to identically challenged controls

| Day postchallengea | % Reductionb

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study A

|

Study B

|

|||||||

| LB1– 86-028NP | LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3– 86-028NP | LB1- 1885MEE | LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3– 1885MEE | LB1– 86-028NP | LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3– 86-028NP | LB1- 1728MEE | LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3– 1728MEE | |

| 9 | 100∗ | 100∗ | ||||||

| 10 | 100∗ | 60 | 100∗ | 87∗ | ||||

| 11 | 100∗ | 50 | 100∗ | 90∗ | ||||

| 12 | 100∗ | 71 | 76 | 87∗ | ||||

| 13 | 100∗ | 92∗ | 100∗ | 100∗ | 100∗ | 83∗ | 76 | 76 |

| 14 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 77 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 100∗ | 51 | 76 |

| 15 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 77 | 100∗ | ||||

| 16 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 81 | 100∗ | ||||

| 17 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 100∗ | 93∗ | ||||

| 18 | 100∗ | 100∗ | 100∗ | 84∗ | ||||

| 19 | 100∗ | 100∗ | ||||||

| 20 | 100∗ | 100∗ | ||||||

| 21 | 100∗ | 100∗ | ||||||

Day after bacterial challenge when >50% of the ears in the sham cohort had effusions.

∗, Significance set at P ≤0.01.

Protective activity of passively delivered antiserum against signs of tympanic membrane inflammation.

Scoring of mean tympanic membrane inflammation alone as an outcome measure for all cohorts in both studies (not shown) corroborated the protection data presented above. The two sham-treated cohorts in both study A (sham–86-028NP and sham-1885MEE) and study B (sham–86-028NP and sham-1728MEE) were the only cohorts in which mean tympanic membrane inflammation scores increased above a value of 1.5 on a 0-to-4 rating scale (a score of 1.5 is the level of inflammation one can attribute to adenovirus alone). The mean inflammation for anti-LB1 and -LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3-treated cohorts was significantly less (P ≤0.05) than that recorded for sham-treated animals challenged with the same NTHI isolate as follows. In study A, there was significantly less inflammation in all ears of the LB1–86-028NP cohort on 18 days of observation (days 9, 11, 13 to 21, and 29 to 35). In animals from the LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–86-028NP cohort, inflammation was significantly less on 23 days of observation (days 13 to 35). For cohorts in study A that were challenged with NTHI strain 1885MEE, significantly reduced inflammation was recorded on 12 days after bacterial challenge (days 8, 9, and 12 to 21) for animals receiving anti-LB1, whereas animals receiving anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 were similarly protected on 11 days (days 8 and 12 to 21). In study B, there was significantly less inflammation on 7 days (days 8 to 14) for both cohorts that had received anti-LB1 or -LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 before challenge with strain 86-028NP. Protection was also seen on day 23 in the latter cohort. Chinchillas that received either of the two immune serum pools were significantly protected from signs of tympanic membrane inflammation on 7 days (days 8 to 14) following challenge with strain 1728MEE.

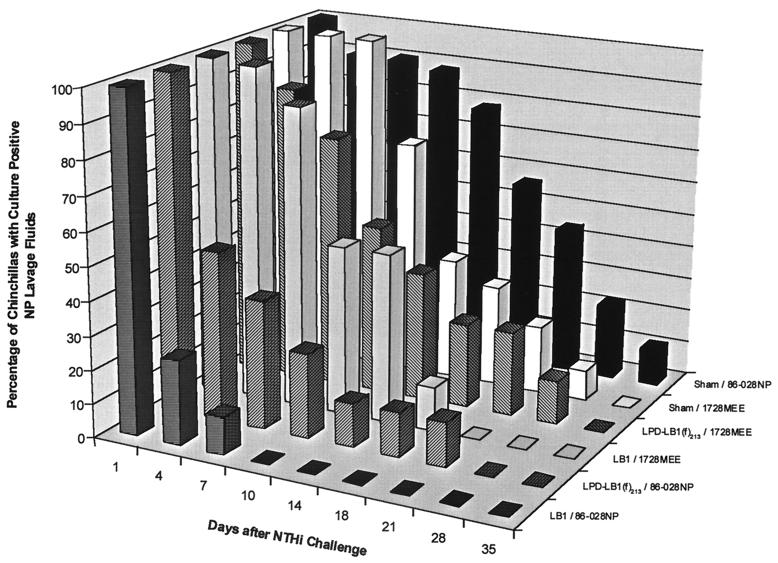

Protective activity of passive antiserum delivery versus NP colonization.

Plate counts confirmed that chinchillas were inoculated i.n. with approximately 108 CFU of NTHI per animal for each of the three NTHI challenge isolates in both studies (1.1 × 108 and 1.2 × 108 strain 86-028NP for studies A and B, respectively, 1.5 × 108 strain 1885MEE, and 9.0 × 107 strain 1728MEE). All cohorts in both studies were colonized, with 89 and 92% of the chinchillas in studies A and B, respectively, demonstrating cultureable NTHI in NP lavage fluids the day after i.n. challenge. The mean concentrations of NTHI per milliliter of lavage fluid were 1.4 × 104 ± 3.3 × 104 CFU in study A and 1.1 × 105 ± 5.7 × 105 CFU in study B. There was no significant difference among cohorts in mean CFU per milliliter of lavage fluid in either study at this point in time.

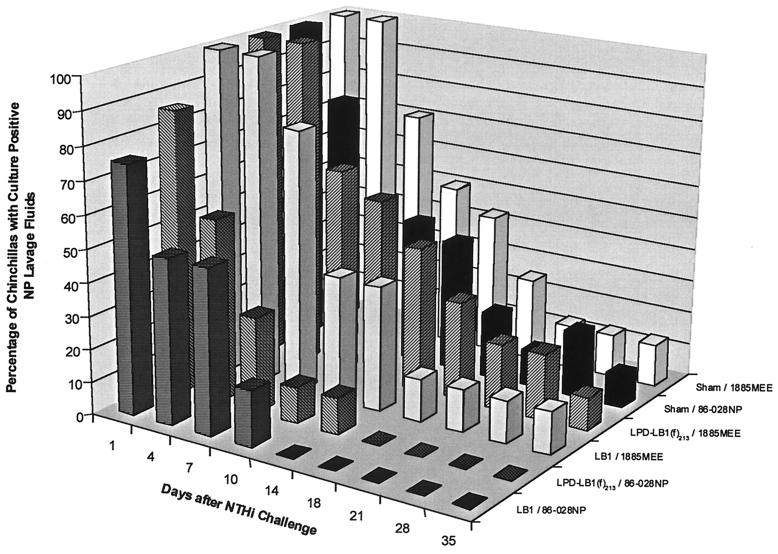

NP lavages for sham–86-028NP cohorts in both study A (Fig. 4) and study B (Fig. 5) remained culture positive for 35 days after challenge. The LB1–86-028NP cohort was the first group to become culture negative for NTHI on day 14 or day 10 after bacterial challenge in studies A and B, respectively. All animals in each LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–86-028NP cohort, in both studies, were cleared of NTHI on day 18 or 28 after challenge. While analysis of data from study A for differences among cohorts in relative time to clearance did show some differences for both the LB1–86-028NP and the LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3–86-028NP cohorts versus the sham–86-028NP cohort, these differences were not statistically significant. Nonetheless, clearance of NTHI from the NP 17 to 21 days earlier by those in the cohort receiving anti-LB1 serum than was observed in sham-treated animals was probably biologically significant. The lack of statistical significance in study A was attributed, in part, to a greater loss of animals than was experienced in study B, where similar findings were found to be statistically significant, as detailed below.

FIG. 4.

Percentage of nasal lavages that were culture positive for NTHI for each cohort in study A.

FIG. 5.

Percentage of nasal lavages that were culture positive for NTHI for each cohort in study B.

In study B (Fig. 5), animals that received anti-LB1 serum were shown to be nearly eight times more likely to clear NTHI from their NPs than the sham-treated and identically challenged animals (P ≤0.001). Similarly, chinchillas that received anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum were 3.5 times more likely to clear NTHI than the sham-treated animals when challenged with NTHI strain 86-028NP (P ≤0.001). There was no statistically significant difference between animals receiving anti-LB1 or anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 in terms of clearance of strain 86-028NP (P ≤0.14) in study B.

In study A (Fig. 4), all three cohorts challenged with strain 1885MEE included animals that remained colonized in the NP for the duration of the 35-day study. Similarly, in study B (Fig. 5), animals that were sham treated or had received anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 prior to challenge with strain 1728MEE remained culture positive for NTHI for 28 days after challenge. The LB1-1728MEE cohort was cleared of NTHI on day 21. There was thus no significant difference between any of these cohorts in terms of the relative percentage of animals that had totally eradicated either NTHI 1728MEE or 1885MEE from the nasopharynx by a given day. Despite a lack of statistical significance in time to clearance of NTHI from the NP, these cohorts were clearly afforded protection from induction of OM, and the source of OM in this model is exclusively from NTHI that was residing in the NP and subsequently ascended the eustachian tube from this site. Furthermore, we found in both studies that clearance of NTHI on or before day 21 occurred in 91% of those animals that never developed OM versus 66% of those that did (P = 0.001). Thus, there was a positive correlation (phi coefficient = 0.31) between earlier clearance and absence of disease.

Thereby, in addition to evaluating the percentage of animals with total eradication of NTHI from this site, as shown in Fig. 4 and 5, we also looked at relative bacterial load in the NP of these animals (not shown). When we compared the animals that remained colonized in each cohort for relative CFU of NTHI per milliliter of NP lavage fluid, two trends were noted. First, we found that for the majority of those animals that did remain colonized, these were the few animals in each cohort that had also developed OM. Second, we noted that animals that were indeed still colonized but had not developed OM had a bacterial load that was 101 to 103 CFU/ml less than equivalent sham-treated and identically challenged animals. A few exceptions did occur, however, there were six immunized animals that cleared NTHI before day 21 but still developed OM; thus, it was evident that early and complete eradication of NTHI from the NP was the desired outcome. In support of this assertion, in the two cohorts in which there was absolutely no evidence of OM (the LB1–86-028NP cohorts in both studies), there was no culturable NTHI in the NP of any animal 7 or 10 days after challenge, respectively.

Functional activities of anti-LB1 and anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum pools. (i) Antiadherence activity.

Both antiserum pools demonstrated the ability to inhibit adherence of NTHI strains belonging to group 1 (86-028L), group 2a (266NP), and group 3 (1728MEE). The mean percent inhibition of adherence of any of the three isolates, at a 1:25 dilution of either antiserum pool, ranged from 25 to 30% relative to naive serum. This observation is consistent with the percent inhibition values that we have reported previously for antiserum directed against isolated P5-fimbrin (21). There were no statistical differences noted for either of these sera against any of the three strains tested in terms of greater ability to inhibit adherence to human OP cells (P ≥0.09 at all dilutions) (not shown).

(ii) Bactericidal activity.

Both anti-LB1 and anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 demonstrated the ability to mediate C′-dependent killing of NTHI strain 86-028L. The median reciprocal titers (n = 6) of these serum pools were 16 and 24, respectively. There was no significant difference between the two serum pools (P = 0.79). Unfortunately, bactericidal activity could not be determined versus strains 1885MEE and 1728MEE due to the extreme sensitivity of these isolates to killing by guinea pig complement alone.

DISCUSSION

We have recently relied upon a chinchilla model wherein adenovirus acts synergistically with NTHI, originating from the colonized NP, to induce OM (11, 22) to enable us to better assess the relative efficacy of several NTHI antigens for their ability to augment bacterial clearance from the NP or from the middle ears. One of the notable strengths of this model is that it more closely mimics the human disease course wherein concurrent or preceding viral infection occurs prior to diagnosis of bacterial OM (10). More recently, we have used this model to test for the ability to prevent the development of bacterial OM as well (4).

In a recent passive-transfer study (4), delivery of diluted anti-LB1 or anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum to adenovirus-compromised chinchillas prior to i.n. challenge with a homologous NTHI isolate (relative to the adhesin the immunogens were designed after) significantly reduced the severity of signs and incidence of OM that developed in each of these cohorts. These data supported the further development of both LB1 and LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 as potential vaccine components; however, they did not address the potential for protective efficacy provided against heterologous NTHI challenge nor did they address the issue of mechanism(s) of protection. Our goal for the present study was thus to further test these immunogens for the breadth of efficacy provided by passive immunization with sera specific for each. We wanted to determine if delivery of these sera would augment clearance of NTHI from the NP and thus also reduce the incidence of OM that developed in chinchillas when challenged with heterologous NTHI strains. In addition, we wanted to determine how these induced antibodies might mediate the protection they conferred to the chinchilla host.

We found that, as in previous studies utilizing this model (4), sham-treated animals followed a predictable disease course for the development and resolution of OM. These animals showed gradually increasing tympanic membrane inflammation and retraction after the inoculation of adenovirus. Middle ear effusions developed in the majority of the ears beginning approximately 1 week after bacterial challenge and persisted for an additional 10 to 12 days. Signs of OM had largely resolved in all ears by approximately 5 weeks after challenge.

Passive transfer of antiserum directed against either immunogen was found to be highly protective against induction of OM upon i.n. challenge with any of the three NTHI isolates selected, although there were similar group-specific differences noted in the ability to totally eradicate NTHI from the NP among cohorts receiving either anti-LB1 or anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3. While a group 1-specific clearance response in the NP could have perhaps been anticipated in animals that received anti-LB1, the immunogen LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 was designed to overcome this limitation. Surprisingly, delivery of anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum was also selectively more effective at inducing clearance of a group 1 isolate from the NP of all animals. Passive transfer of either serum pool allowed more animals to remain colonized for a longer period of time when challenged with a group 2a or 3 isolate compared to the group 1 strain. It is not yet clear why the group 1 isolate was preferentially cleared from the NP after passive transfer of anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 serum. In fact, the group 1 sequence occurs between the group 2a and 3 sequences in the recombinant protein, thus potentially limiting its accessibility to immune effector cells. It is possible, however, that the orientation of the group 1 sequence in the middle position may have actually induced the physical constraints needed in an aqueous environment to optimize its accessibility within this large recombinant fusion protein immunogen.

Nevertheless, both immunogens induced antibodies that provided significant protection against OM upon heterologous NTHI challenge. Passive immunization with undiluted anti-LB1 serum followed by challenge with a group 1 NTHI was extremely efficacious. None of the animals in these cohorts, in either of the two studies, developed OM. Thus, greater efficacy was shown here using undiluted anti-LB1 than was shown previously when a similar antiserum pool was used at a 1:5 dilution (4). In the earlier study, 15% of the ears developed an effusion. Importantly, the protection conferred by passive transfer of anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 generated with alum plus MPL was equivalent to that conferred by anti-LB1 serum against a group 1 challenge. Delivery of either serum pool also significantly reduced the percentage of effusions that developed in animals challenged with strain 1885MEE (a group 2a isolate) or with strain 1728MEE (a group 3 isolate) compared to sham-immunized cohorts on the majority of days during which the sham cohorts had greater than 50% of the ears containing an effusion.

It had been anticipated that anti-LB1 serum would be shown to be effective at preventing OM induced by a group 1 strain, since this immunogen was derived from the translated amino acid sequence of the P5-fimbrin protein of another group 1 isolate (strain 1128) and had already shown great protective efficacy in previous studies against homologous challenge (4, 22). What was more interesting, however, was its ability to also confer heterologous protection, particularly in light of the described sequence diversity in the third surface-exposed region of mature P5-fimbrin from which it is derived (4). These data thus suggest that the approximately nine-residue N-terminal portion of the 19-mer sequence that is shared among all three NTHI groups and is incorporated into LB1 [RSDYKF(L)YE(N,D)D(K,N)] is potentially an immunodominant region that includes a protective epitope. It is also possible that the T-cell promiscuous epitope incorporated into LB1 had a significant influence on the cross-protection observed here, as did the use of the strong adjuvant CFA. Nevertheless, due to the noted diversity, primarily in the C-terminal portions of this focused region, and yet the broad protection conferred by immunization with LB1, it is not likely that the highly conserved N-terminal sequence of the epitope included in LB1 (RSDYKFYED) is largely inaccessible, as has been predicted (12). Our data thus are more in keeping with the model of this surface protein proposed by Webb and Cripps (23) in which the N-terminal sequence of loop (or region) 3 (LVRSDYKFYEDANGT) is surface accessible.

In a recent effort to map the immunodominant epitopes of P5-fimbrin, however (18), we showed that immunization with LB1 induced antibodies that strongly recognized a peptide representing the C-terminal one-half of the majority group 1 sequence but not a peptide representing the common N-terminal half in a biosensor assay. This serum pool also strongly reacted with a peptide representing the majority group 1 sequence from which it was derived. When reacted with peptides representing the group 2a, 2b, or 3 consensus sequences, the greatest reactivity was shown against the more-diverse group 3 peptide, followed by reactivity with the 2b peptide and virtually no reactivity was shown with a similar group 2a peptide. Recognizing that there are some conformational restraints innate to this biosensor system, we also analyzed this serum pool by Western blotting and ELISA (unpublished observations). By both assays, the anti-LB1 serum pool recognized only a group 1 and not a group 2a, 2b, or 3 peptide. However, by ELISA, anti-LB1 preferentially recognized an N-terminal peptide from the majority group 1 sequence over an overlapping middle or C-terminal sequence (18). Thereby, while few of the mapping data obtained in vitro with linear peptides and anti-LB1 serum predicted immunodominance of the N terminus of this 19-mer, the protection data obtained in situ strongly supported this assertion.

Another goal of this study was to determine how the protection we observed was mediated. Thus, the antiserum pools that were passively transferred were assessed for titer, specificity, ability to mediate C′-dependent killing, and ability to inhibit adherence of NTHI to a human airway epithelial target cell. We found that both serum pools were high titered, specific for the immunogen delivered, and able to mediate C′-dependent killing of a group 1 isolate. While all of these qualities are desirable to achieve after immunization, these parameters alone have not allowed us to predict protective efficacy in the chinchilla model in the past (4). High-titer and specific sera directed against LPD or a recombinant deacylated form of LPD (PDm), which also mediated equivalent or greater C′-dependent killing of NTHI than the serum pools described here, did not confer protection against induction of OM after passive transfer in an earlier study (4), although they did augment recovery from disease. While bactericidal activity likely did contribute to the protection afforded here, our inability to show a direct correlation between relative bactericidal titer and protection in the chinchilla model is consistent with that reported by others using recombinant NTHI OMP D15 in an infant rat model (15), isolated OMP P6 in a rat lung clearance model (14a), as well as in other human diseases (19, 20). A lack of correlation between titer and bactericidal activity for murine antisera directed against NTHI OMP and lipooligosaccharide conjugate vaccines, as well as between rabbit anti-OMP immunoglobulin G (IgG) or IgM levels and bactericidal titer, has been reported as well (24).

The serum pools transferred to juvenile animals in the studies reported here were also found to be inhibitory to NTHI adherence to a human epithelial target cell, and this mechanism also likely contributed to the NP clearance effect and the protection against OM shown. Both serum pools were additionally found to label native structures on whole unfixed NTHI of all three LB1(f) groups in a pattern similar to that reported earlier (4, 5; unpublished observations). Thus, concerns over the ability of tandem linear peptides to induce antibody that could recognize diverse native proteins were at least partially alleviated. However, the ability of the anti-LB1 serum pool to also immunolabel members of NTHI groups 1, 2a, and 3 supports the protection data obtained herein with LB1, which suggests that the conserved N-terminal portion of the third predicted surface exposed region of P5-fimbrin [containing the shared sequence RSDYKF(L)YE(N,D)D(K,N)] is immunoaccessible.

In summary, passive immunization with anti-LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 or anti-LB1 serum has been shown to be broadly protective against OM induced following i.n. challenge with heterologous NTHI strains. Despite conferring significant and broad protection against ascension of the eustachian tube and induction of OM, passive transfer of serum specific for either immunogen did not induce total and early eradication of heterologous NTHI isolates from the NP in an equivalent manner. Both immunogens induced significant preferential clearance of a group 1 NTHI isolate over a group 2a or group 3 strain. However, all cohorts were nonetheless protected from NTHI-induced middle ear infection, which in our animal model must originate from the colonized NP. Analysis of the bacterial load in the NP of those animals that were still colonized, but had no signs of OM, indicated that there were typically 101 to 103 fewer CFU of NTHI per ml of lavage fluid in these animals than was found in equivalently challenged but sham-treated animals. Thereby, these data suggested that, whereas complete and early eradication of NTHI from the NP should be the desired outcome and, in fact, proved to be completely protective when achieved (as in LB1–86-028NP cohorts in both studies), it was not absolutely required to prevent the development of OM in some individuals. Rather, a reduction of the bacterial load to a level below a critical threshold may be sufficient. However, in the few immunized animals that did develop OM in immunized cohorts, the longer period of NP colonization was the likely reason for vaccinogen failure. The modest but positive correlation found between total eradication of NTHI from the NP on or before day 21 after challenge and absence of OM supported this assertion.

Thereby, while the findings obtained in terms of preferential clearance of group 1 NTHI isolates from the NP could have been anticipated for the immunogen LB1, similar data obtained with LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 indicated that the configuration of this immunogen may not yet be fully optimal. Modification of LPD-LB1(f)2,1,3 to further improve the ability to induce antibody with the capability of inducing early and complete eradication of heterologous NTHI from the nasopharynx is our current goal. Both immunogens remain very strong vaccine candidates.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by a grant from SmithKline Beecham Biologicals and, in part, by National Institutes of Health grant R01 DC02830-03.

We thank Jolene DeFiore-Hyrmer, Marilyn Kennedy, and Shani Thompson for expert technical assistance, Jim Rauscher for chinchillas, Lynn Mitchell and John Hayes for biostatistical analyses, and Carrie Schreiner for preparation of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akkoyunlu M, Melhus A, Capiau C, van Opstal O, Forsgren A. The acylated form of protein D of Haemophilus influenzae is more immunogenic than the nonacylated form and elicits an adjuvant effect when it is used as a carrier conjugated to polyribosyl ribitol phosphate. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5010–5016. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5010-5016.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bakaletz L O, Daniels R L, Lim D J. Modeling adenovirus type 1-induced otitis media in the chinchilla: effect on ciliary activity and fluid transport function of eustachian tube mucosal epithelium. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:865–872. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.865. . (Erratum, 168:1605.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bakaletz L O, Holmes K A. Evidence for transudation of specific antibody into the middle ears of parenterally immunized chinchillas after an upper respiratory tract infection with adenovirus. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1997;4:223–225. doi: 10.1128/cdli.4.2.223-225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bakaletz L O, Kennedy B J, Novotny L A, Dequesne G, Cohen J, Lobet Y. Protection against development of otitis media induced by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae by both active and passive immunization in a chinchilla model of virus-bacterium superinfection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2746–2762. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2746-2762.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bakaletz L O, Leake E R, Billy J M, Kaumaya P T. Relative immunogenicity and efficacy of two synthetic chimeric peptides of fimbrin as vaccinogens against nasopharyngeal colonization by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in the chinchilla. Vaccine. 1997;15:955–961. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00298-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bakaletz L O, Murwin D M, Billy J M. Adenovirus serotype 1 does not act synergistically with Moraxella Branhamella) catarrhalis to induce otitis media in the chinchilla. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4188–4190. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.4188-4190.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bakaletz L O, Tallan B M, Andrzejewski W J, DeMaria T F, Lim D J. Immunological responsiveness of chinchillas to outer membrane and isolated fimbrial proteins of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1989;57:3226–3229. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.10.3226-3229.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bakaletz L O, Tallan B M, Hoepf T, DeMaria T F, Birck H G, Lim D J. Frequency of fimbriation of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae and its ability to adhere to chinchilla and human respiratory epithelium. Infect Immun. 1988;56:331–335. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.2.331-335.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barenkamp S J. Protection by serum antibodies in experimental nontypable Haemophilus influenzae otitis media. Infect Immun. 1986;52:572–578. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.572-578.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Clements D A, Henderson F W, Neebe E C. Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on Recent Advances in Otitis Media. Hamilton, Ontario, Canada: Decker Periodicals; 1993. Relationship of viral isolation to otitis media in a research day-care center 1978–1988; pp. 27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeMaria T F, Murwin D M, Leake E R. Immunization with outer membrane protein P6 from nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae induces bactericidal antibody and affords protection in the chinchilla model of otitis media. Infect Immun. 1996;64:5187–5192. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.12.5187-5192.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duim B, Bowler L D, Eijk P P, Jansen H M, Dankert J, van Alphen L. Molecular variation in the major outer membrane protein P5 gene of nonencapsulated Haemophilus influenzae during chronic infections. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1351–1356. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.4.1351-1356.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giebink G S, Heller K A, Harford E R. Tympanometric configurations and middle ear findings in experimental otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:20–24. doi: 10.1177/000348948209100106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Janson H, Melhus A, Hermansson A, Forsgren A. Protein D, the glycerophosphodiester phosphodiesterase from Haemophilus influenzae with affinity for human immunoglobulin D, influences virulence in a rat otitis model. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4848–4854. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4848-4854.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14a.Kyd J M, Dunkley M L, Cripps A W. Enhanced respiratory clearance of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae following mucosal immunization with P6 in a rat model. Infect Immun. 1995;63:2931–2940. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.2931-2940.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loosmore S M, Yang Y P, Coleman D C, Shortreed J M, England D M, Klein M H. Outer membrane protein D15 is conserved among Haemophilus influenzae species and may represent a universal protective antigen against invasive disease. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3701–3707. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3701-3707.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Margolis R H, Hunter L L, Giebink G S. Tympanometric evaluation of middle ear function in children with otitis media. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl. 1994;163:34–38. doi: 10.1177/00034894941030s510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miyamoto N, Bakaletz L O. Selective adherence of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHi) to mucus or epithelial cells in the chinchilla eustachian tube and middle ear. Microb Pathog. 1996;21:343–356. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1996.0067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Novotny L A, Jurcisek J A, Bakaletz L O. Epitope mapping of the OMP P5-homologous fimbrin protein of nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1590–1599. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2119-2128.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perkins B A, Jonsdottir K, Briem H, Griffiths E, Plikaytis B D, Hoiby E A, Rosenqvist E, Holst J, Nokleby H, Sotolongo F, Sierra G, Campa H C, Carlone G M, Williams D, Dykes J, Kapczynski D, Tikhomirov E, Wenger J D, Broome C V. Immunogenicity of two efficacious outer membrane protein-based serogroup B meningococcal vaccines among young adults in Iceland. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:683–691. doi: 10.1086/514232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosenqvist E, Musacchio A, Aase A, Hoiby E A, Namork E, Kolberg J, Wedege E, Delvig A, Dalseg R, Michaelsen T E, Tommassen J. Functional activities and epitope specificity of human and murine antibodies against the class 4 outer membrane protein (Rmp) of Neisseria meningitidis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:1267–1276. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.3.1267-1276.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sirakova T, Kolattukudy P E, Murwin D, Billy J, Leake E, Lim D, DeMaria T, Bakaletz L. Role of fimbriae expressed by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in pathogenesis of and protection against otitis media and relatedness of the fimbrin subunit to outer membrane protein A. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2002–2020. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.2002-2020.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Suzuki K, Bakaletz L O. Synergistic effect of adenovirus type 1 and nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in a chinchilla model of experimental otitis media. Infect Immun. 1994;62:1710–1718. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.5.1710-1718.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webb D C, Cripps A W. Secondary structure and molecular analysis of interstrain variability in the P5 outer-membrane protein of non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae isolated from diverse anatomical sites. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:1059–1067. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-12-1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu T, Gu X. Outer membrane proteins as a carrier for detoxified lipooligosaccharide conjugate vaccines for nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5508–5513. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5508-5513.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y P, Loosmore S M, Underdown B J, Klein M H. Nasopharyngeal colonization with nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae in chinchillas. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1973–1980. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.1973-1980.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]