Abstract

Objective

The objective of this study was to evaluate the acceptance and uptake of COVID-19 vaccines in rural Bangladesh.

Design

This was a cross-sectional study conducted between June and November 2021.

Setting

This study was conducted in rural Bangladesh.

Participants

People older than 18 years of age, not pregnant and no history of surgery for the last 3 months were eligible to participate.

Primary and secondary outcomes

The primary outcomes were proportions of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and roll-out participation among the rural population. The secondary outcome was identification of correlates which contributed to COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and roll-out participation. Χ2 tests and multivariable logistic regression analyses were performed to identify relevant correlates such as sociodemographic factors, clinical conditions and COVID-19-related factors.

Results

A total of 1603 participants were enrolled. The overall COVID-19 vaccine acceptance was very high (1521/1601, 95%), and half of the participants received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine. Majority of participants wanted to keep others safe (89%) and agreed to the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines (88%). To fulfil the requirement of online registration for the vaccine at the time, 62% of participants had to visit an internet café and only 31% downloaded the app. Over half (54%) of participants were unaware of countries they knew and trust to produce the COVID-19 vaccine. Increased age, being housewives, underweight and undergraduate education level were associated with vaccine acceptance, while being female, increased age and being overweight/obese were associated with vaccine uptake. Trust in the health department and practical knowledge regarding COVID-19 vaccines were positively associated with both vaccine acceptance and uptake.

Conclusion

This study found a very high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in rural Bangladesh. Policymakers should support interventions aimed at increasing vaccine and general health literacy and ensure ongoing vaccine supply and improvement of infrastructure in rural areas.

Keywords: COVID-19, epidemiology, health policy, public health

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Despite numerous publications measuring vaccine acceptance in Bangladesh, there remains significant under-representation of rural communities in the COVID-19 vaccine literature. This study addresses this important population gap. We found a very high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in rural Bangladesh, despite evident barriers such as low health literacy and poor access to digital resources.

The strengths of this study include the large sample of community-level data and use of offline data collection methods suitable for the assessment of rural population.

The limitations include inability to make inference and calculate incidence due to the cross-sectional nature of the study. We also did not collect income-related data.

Introduction

Mass vaccinations have been demonstrated to effectively curb the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic in many countries, allowing livelihoods to return to a new normal.1 However, vaccine hesitancy has resulted in delay of acceptance or complete refusal of safe and efficacious COVID-19 vaccines across the globe.2 3 In early 2021, a study of low to middle-income countries (LMICs) across Asia, Africa and South America reported an overall COVID-19 vaccine acceptance rate of 80%.4 Acceptance rates in Bangladesh, India, Pakistan and Nepal were lower at the time, at 65%, 66%, 72% and 74%, respectively.5 In many countries, including LMICs, the risk of potential vaccine hesitancy remains significant due to complex political, geographical, social and other determinants.6

As of 29 August 2022, 71% of the entire Bangladeshi population have received two doses of the COVID-19 vaccines and 6% have received the boosters.7 Prior to reaching the WHO global double-dose vaccination target of 70%,8 Bangladesh was among the slowest in Asia and globally to reach this target. The primary reasons were due to vaccine inequity and a lack of supply, as also seen in other LMICs.9 10 In contrast, most high-income countries had already vaccinated a majority of their population by late 2020 or early 2021, including significant population vaccinated with boosters as of August 2022.11 While currently available COVID-19 vaccines do not necessarily prevent COVID-19 infection, it is highly effective at preventing hospital systems from being overwhelmed by patients with COVID-19 (due to reduced hospitalisation).12 The World Health Organization (WHO) further emphasised the need to ensure high level of vaccine coverage in all countries due to ongoing threat posed by COVID-19 pandemic, such as the emergence of new variants.13

To date, there are no vaccine acceptance studies which solely address the rural population in Bangladesh. The majority of previous studies, except for one study,14 also used online data collection methods5 15–18, and included mostly young to middle-aged people living in urban areas. Crucially, most Bangladeshis living in rural or remote areas do not have access to online resources and are more likely to be excluded from internet-based studies.19 Therefore, despite the numerous publications which measured vaccine acceptance in Bangladesh, there remains significant under-representation of rural communities in the COVID-19 vaccine literature. Rural Bangladeshis also represent 62% of the entire population,20 are more likely to have lower socioeconomic status and have poorer access to healthcare facilities.21 It is imperative that their perspectives are not left behind in policy decisions. Additionally, the data collection period of these prior studies was before or during the initial phase of the vaccine roll-out programme.5 9 15–17 It is of interest to appraise whether vaccine acceptance has changed over time with changing circumstances, such as improved knowledge of the COVID-19 vaccine. The effects of other potentially critical determinants on COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in the rural population, such as the effect of misinformation of vaccine safety and efficacy, social media and previous COVID-19 diagnosis, and barriers to receiving vaccines, are also unknown. Therefore, using offline data collection methods, this cross-sectional study aimed to evaluate COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and participation rates in rural Bangladesh between June and November 2021.

Methods

Study design and population

We conducted a cross-sectional study in rural Bangladesh from June to November 2021. For sampling, a multistage cluster random approach was used. Households were selected from 17 villages in rural Bangladesh and data were collected from an eligible member in the selected household using the ‘Kish Grid’ method.22 Sample size calculation is provided in online supplemental appendix 1.

bmjopen-2022-064468supp001.pdf (240.8KB, pdf)

Patient and public involvement

Patients or the public were not involved in the design, reporting or dissemination plans of our research.

Sampling method

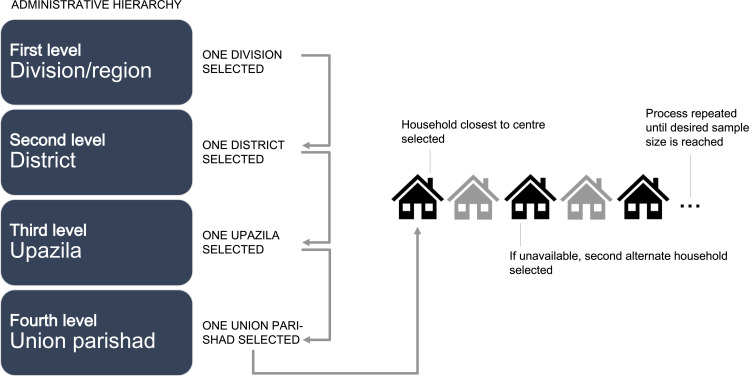

A multistage cluster random sampling method was used. Randomness was maintained throughout the selection process. Geographically, Bangladesh is divided into eight divisions/regions, the first level of administrative hierarchy (figure 1). One division was randomly selected from these eight divisions, followed by a random selection of one district from all the districts (the second level of administrative hierarchy) of the selected division. Thereafter, an upazila (third level of administrative hierarchy) was selected from the selected district. Finally, a union parishad (the fourth and final level of administrative hierarchy) was selected from this upazila.

Figure 1.

Sampling method. For data sampling, one of eight divisions/regions in Bangladesh (the first level of administrative hierarchy) was randomly selected. Subsequently, one district (the second level of administrative hierarchy) was randomly selected, followed by random selection of an upazila (third level of administrative hierarchy) from the selected district. Finally, a union parishad (the fourth and final level of administrative hierarchy) was selected from this upazila. A household closest to the centre point of the union parishad was identified as the first household for enrolment. Then, a household member was selected according to the ‘Kish Grid’ method. If the selected household member was unavailable, the next eligible household was approached. The second eligible household was selected by skipping the next household and choosing the subsequent household (ie, every alternate household).

The interviewers first identified a household closest to the centre point of the union parishad as the first household for enrolment. Then, using predefined inclusion criteria, a household member was interviewed.23 The selection criteria included adults aged ≥18 years who provided consent, not pregnant, without history of surgery in the last 3 months and reside in the recruited household within the targeted villages. People residing in urban Bangladesh were excluded.

The ‘Kish Grid’ method was used to collect data from an eligible member in the selected household.22 This method required interviewing only a single eligible member of the selected household. If the selected household member was unavailable (eg, household shutdown or decline to participate), the next eligible household was approached (figure 1). The second eligible household was selected by skipping the next household, and choosing the subsequent household (ie, every alternate household). This process was repeated until the required sample size of at least 1553 participants was reached (see online supplemental appendix 1 for sample size calculations). A total of 17 villages were covered in this survey.

Throughout the data collection period, sex and age group proportion were maintained. Training was provided for data collectors, including COVID-19 safe practice (see online supplemental appendix 2 for more information).

Participants’ consent

Prior to commencement of the interview, the data collector informed every potential participants regarding the details of the study, including freedom to participate and how the information will be used. If they agreed to participate, an explanatory statement was provided and any queries were addressed. The participants were asked to sign a consent form after which they were interviewed.

Data collection

A structured questionnaire was developed for this study based on published literature and validated questionnaires. The questions were written in plain and simple English, which was translated into Bengali, the local language. To ensure consistency, the Bengali version was again converted to English. The questionnaire took approximately 40 min to complete per participant. Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), a secure web-based application, was used to create the survey, pool and manage data. REDCap ensures validated data entry, helps track data manipulation and enables easy and automated data export into common statistical software packages. Online supplemental appendices 3 and 4 provide details on quality control of data collection and data access and storage, respectively.

We collected participants’ sociodemographic information (age, sex, marital status, education level and employment status), lifestyle factors (smoking status and consumption of chewing tobacco alone or with betel leaf), anthropometric measures (height, weight, waist and hip size) and clinical conditions (hypertension, coronary artery disease (CAD), kidney disease, cancer, asthma, stroke, anxiety and depressive symptom). Vaccine acceptance was determined using a close-ended question inquiring participants’ willingness to get vaccinated as the main outcome variable. It has two categorical responses: yes (indicating acceptance) and maybe/no (hesitance). Vaccine hesitancy was defined as a delay in acceptance or downright refusal of vaccines although readiness of vaccine services, as per WHO’s definition.24 Vaccine roll-out participation was determined using a close-ended question inquiring whether participants have received at least the first dose of COVID-19 vaccine. The question had two categorical responses (yes and no). Non-demographic correlates which may have contributed to vaccine acceptance and roll-out participation were determined. This included participants’ general knowledge regarding vaccinations prior to the pandemic, knowledge and/or experience regarding the COVID-19 vaccine (including availability, accessibility, perceptions of risk and benefits, scheduling and compliance) and factors which may contribute to hesitancy such as political and religious factors, previous COVID-19 status, trust (or a lack thereof) in health systems or pharmaceutical industries, and potential source of vaccine misinformation such as use of social media. We also explored willingness-to-pay perceptions if the COVID-19 vaccine was no longer available for free in Bangladesh.

Measures of anthropometric and clinical variables

Participants’ heights and weights were collected. Blood pressure measurements were taken three times in 5 min intervals. Any history of chronic disease including coronary artery disease (CAD), kidney disease, diabetes, asthma, cancer, arthritis and stroke was validated through documented diagnosis or medication history (verified by a medical doctor) or any past clinical procedures. Anxiety and depressive symptom were assessed using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 Scale25 and Patient Health Questionnaire-9,26 respectively, both of which have been validated for use in the Bangladeshi context.27 28 Operational definitions used in this study are provided in online supplemental appendix 5.

Outcome measures

The main outcomes of interest were prevalence of vaccine acceptance and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine. Vaccine acceptance was defined as the individual decision to accept or refuse vaccines when presented with the opportunity to vaccinate.29 Vaccine uptake was defined as having received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics of demographic, lifestyle and clinical variables of vaccine acceptance and roll-out participation were presented as frequencies and percentages for categorical variables and means and SDs for continuous variables. Χ2 test was performed to assess the association between vaccine acceptance and roll-out participation with all potential correlates. Multivariable logistic regression analyses along with stepwise variable selection were performed for two main outcome variables: COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (yes/no) and if one has received at least one dose of COVID-19 vaccine (yes/no). Adjusted odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported. A two-tailed p value of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All the statistical analyses were performed in Stata V.17.0.

Results

Characteristics of study participants

Table 1 details the characteristics of the study participants. The total number of participants in this study was 1603, wherein 51% were male. The mean age of participants was 42.3±14.2 years. The majority of participants were married (88%) and attended secondary school as their highest level of education (42.2%). The proportion of participants who were married or employed was identical (44.5%). Of all participants, nearly a fifth (20%) were active smokers and 24% were regular users of chewing tobacco. The mean body mass index (BMI) of participants was 24.2±6.2 kg/m2. Almost a third (31%) of study participants presented with a chronic disease.

Table 1.

Distribution of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and roll-out in rural Bangladesh according to sociodemographic, lifestyle and clinical factors (n=1603)

| Variables | Vaccine acceptance | Received COVID-19 vaccine | ||||

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P value | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | P value | |

| All participants | 1521 (95.0) | 82 (5.0) | 801 (50.0) | 802 (50.0) | ||

| Sociodemographic factors | ||||||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 761 (93.1) | 57 (6.9) | 0.001 | 411 (50.2) | 407 (49.8) | 0.822 |

| Female | 760 (96.8) | 25 (3.2) | 390 (49.7) | 395 (50.3) | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| <30 | 333 (88.3) | 44 (11.7) | <0.001 | 99 (26.3) | 278 (73.7) | <0.001 |

| 30–50 | 777 (97.3) | 22 (2.8) | 430 (53.8) | 369 (46.2) | ||

| >50 | 411 (96.3) | 16 (3.8) | 272 (63.7) | 155 (36.3) | ||

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 1347 (95.6) | 61 (4.3) | <0.001 | 725 (51.5) | 683 (48.5) | <0.001 |

| Not married | 76 (81.7) | 17 (18.3) | 17 (18.3) | 76 (81.7) | ||

| Others | 98 (96.1) | 4 (3.9) | 59 (57.8) | 43 (42.2) | ||

| Education level | ||||||

| Illiterate/never went to school | 422 (96.1) | 17 (3.9) | 0.181 | 234 (53.3) | 205 (46.7) | 0.026 |

| Primary school | 392 (95.8) | 17 (4.2) | 217 (53.1) | 192 (46.9) | ||

| Secondary | 632 (93.5) | 44 (6.5) | 319 (47.2) | 357 (52.8) | ||

| Undergraduate and above | 75 (94.9) | 4 (5.1) | 31 (39.2) | 48 (60.8) | ||

| Employment status | ||||||

| Unemployed | 100 (93.5) | 7 (7.5) | <0.001 | 72 (67.3) | 35 (32.7) | <0.001 |

| Employed/self-employed | 673 (94.3) | 41 (5.7) | 367 (51.4) | 347 (48.6) | ||

| Housewife | 692 (97.1) | 21 (2.9) | 352 (49.4) | 361 (50.6) | ||

| Students or retirees | 56 (81.2) | 13 (18.8) | 10 (14.5) | 59 (85.5) | ||

| Lifestyle-related factors | ||||||

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Normal (18.5–22.9) | 511 (91.9) | 45 (8.1) | 0.001 | 247 (44.4) | 309 (55.6) | 0.002 |

| Underweight (<18.5) | 129 (96.2) | 5 (3.7) | 60 (44.8) | 74 (55.2) | ||

| Overweight (23.0–27.5) | 569 (96.2) | 22 (3.7) | 317 (53.6) | 274 (46.4) | ||

| Obese (>27.5) | 312 (96.8) | 10 (3.1) | 177 (54.9) | 145 (45.1) | ||

| Smoking history | ||||||

| Current smoker | 288 (91.1) | 28 (8.9) | 0.001 | 150 (47.5) | 166 (52.5) | 0.076 |

| Ex-smoker | 85 (92.4) | 7 (7.6) | 56 (60.9) | 36 (39.2) | ||

| Non-smoker | 1140 (96.0) | 47 (3.9) | 593 (49.9) | 594 (50.1) | ||

| Chewing tobacco or betel leaf users | ||||||

| Current user | 362 (94.0) | 23 (6.0) | 0.318 | 212 (55.1) | 173 (44.9) | 0.053 |

| Former user | 28 (90.3) | 3 (9.7) | 17 (54.8) | 14 (45.2) | ||

| Non-user | 1130 (95.3) | 56 (4.7) | 571 (48.2) | 615 (51.8) | ||

| Use of social media | ||||||

| Yes | 267 (89.6) | 31 (10.4) | <0.001 | 108 (36.2) | 190 (63.8) | <0.001 |

| No | 1254 (96.1) | 51 (3.91) | 693 (53.1) | 612 (46.9) | ||

| Clinical factors | ||||||

| Chronic disease | ||||||

| No conditions | 965 (93.8) | 64 (6.2) | 0.124 | 483 (46.9) | 546 (53.1) | 0.022 |

| Hypertension | 134 (95.1) | 7 (4.9) | 77 (54.6) | 64 (45.4) | ||

| Diabetes | 204 (97.1) | 6 (2.9) | 123 (58.6) | 87 (41.4) | ||

| Heart disease | 51 (98.1) | 1 (1.9) | 25 (48.1) | 27 (51.9) | ||

| Asthma | 72 (97.3) | 2 (2.7) | 38 (51.4) | 36 (48.6) | ||

| Others* | 95 (97.9) | 2 (2.1) | 55 (56.7) | 42 (43.3) | ||

| Anxiety | ||||||

| Have anxiety | 239 (92.3) | 20 (7.7) | 0.038 | 677 (50.4) | 667 (49.6) | 0.462 |

| Do not have anxiety | 1282 (95.4) | 62 (4.6) | 124 (47.8) | 135 (52.1) | ||

| Depressive symptom | ||||||

| Have depressive symptom | 285 (95.6) | 13 (4.4) | 0.513 | 650 (49.8) | 655 (50.2) | 0.788 |

| Do not have depressive symptom | 1236 (94.7) | 69 (5.3) | 151 (50.6) | 147 (49.3) | ||

*Stroke, arthritis, cancer, kidney disease and others.

Table 2 provides a summary finding of key practical and behavioural questions. Among our study participants, only 21% had a smartphone and 19% were social media users. Television and relatives/friends were the main source of information. Participants had a good understanding of vaccine benefits and side effects in general, but only 50% have been previously vaccinated with other vaccines prior to COVID-19 (eg, influenza vaccine). Only 31% of participants who had registered for the vaccine used the registration app; most participants have not tried it (68%). Nearly all participants responded positively to questions related to trust in the government and health department. Regarding trust in pharmaceutical companies, the responses were divided. Over half (54%) of participants did not know which country they were aware of and trusted to produce the COVID-19 vaccine.

Table 2.

Key practical and behavioural questions regarding COVID-19 vaccination in rural Bangladesh

| Questions | Response | ||

| Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Unsure/others, n (%) | |

| Attitude towards vaccination (in general terms) prior to COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Are you aware of the benefits of vaccines? | 1451 (90.6) | 151 (9.4) | N/A |

| Are you aware of potential side effects of vaccines? | 1178 (73.5) | 424 (26.5) | N/A |

| Have you been vaccinated previously, for example, for influenza? | 794 (49.9) | 796 (50.1) | N/A |

| Previous experience with vaccination prior to COVID-19 pandemic | |||

| Was the place you had your vaccination clean? | 773 (97.7) | 18 (2.3) | N/A |

| Did you consider the delivery of the vaccine safe? | 655 (82.9) | 135 (17.1) | N/A |

| Did you experience any side effects after getting vaccinated? | 125 (15.9) | 659 (84.1) | N/A |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| Have you heard about the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1597 (99.7) | 5 (0.3) | N/A |

| Do you understand the dosage? | 1525 (95.2) | 77 (4.8) | N/A |

| Are you familiar with the brands? | 1484 (92.9) | 113 (7.1) | N/A |

| Are you aware of the potential side effects? | 1341 (83.7) | 261 (16.3) | 1 (0.1) |

| Source of information for COVID-19 vaccination | |||

| What is your main source of COVID-19 information? | – | – | – |

| Television | 895 (55.8) | N/A | N/A |

| Social media | 166 (10.4) | N/A | N/A |

| Relatives or friends | 534 (33.3) | N/A | N/A |

| Others | 8 (0.5) | N/A | N/A |

| Do you trust your main source of information? | 1253 (78.2) | 6 (0.4) | 343 (21.4) |

| Do you use social media? | 298 (18.6) | 1305 (81.4) | N/A |

| If yes, which platform do you use? | – | – | – |

| Facebook messenger | 288 (96.6) | N/A | N/A |

| Instagram or others | 10 (3.4) | N/A | N/A |

| If yes, do you always believe everything you find there? | 22 (7.4) | 12 (4.0) | 264 (88.6) |

| If yes, do you think all the information is from a trusted source? | 21 (7.1) | 18 (6.0) | 259 (86.9) |

| Availability and potential barriers of getting the COVID-19 vaccine | |||

| Do you have smartphones? | 338 (21.1) | 1265 (78.9) | N/A |

| Do you understand how to register for the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1439 (89.8) | 164 (10.2) | N/A |

| Have you registered for the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1242 (77.9) | 353 (22.1) | N/A |

| If yes, did you find the overall registration process easy? | 1016 (87.2) | 149 (12.8) | N/A |

| If yes, was the app easy to download and use? | 73 (31.2) | 1 (0.4) | 160 (68.4)* |

| Any out-of-pocket costs associated with the registration? | 1019 (71.4) | 241 (16.9) | 167 (11.7) |

| Do you know where to get the COVID-19 vaccine? | 1587 (99.1) | 15 (0.9) | N/A |

| Is it easy to travel there? | 1518 (95.7) | 37 (2.3) | 31 (2.0) |

| Influence of previous COVID-19 status | |||

| Have you been tested for COVID-19 before? | 25 (1.6) | 1578 (98.4) | N/A |

| Have you been diagnosed with COVID-19 before? | 6 (0.4) | 1597 (99.6) | N/A |

| Has a close relative or friend been previously diagnosed with COVID-19? | 31 (1.9) | 1571 (98.1) | N/A |

| Influence of personal beliefs | |||

| Do you trust the government information related to COVID-19 vaccine? | 1550 (96.8) | 11 (0.7) | 41 (2.6) |

| Should the government make the COVID-19 vaccine compulsory? | 1541 (96.1) | 32 (2.0) | 30 (1.9) |

| Is the government doing a good job with the roll-out? | 1452 (90.6) | 77 (4.8) | 73 (4.6) |

| Do you trust the health department related to COVID-19 vaccine? | 1566 (97.8) | 15 (0.9) | 20 (1.3) |

| Is the health department doing a good job with the roll-out? | 1479 (92.6) | 56 (3.5) | 63 (3.9) |

| Do you think pharmaceutical companies developed the vaccine to help the society? | 626 (39.1) | 827 (51.8)† | 146 (9.1) |

| Does your religion have any restrictions on getting vaccinated? | 3 (0.2) | 1513 (94.4) | 87 (5.4) |

| Which country were you aware of and trust to produce the COVID-19 vaccine? | – | – | – |

| India | 45 (2.8) | N/A | N/A |

| China | 461 (28.8) | N/A | N/A |

| Russia | 15 (0.9) | N/A | N/A |

| UK | 19 (1.2) | N/A | N/A |

| USA | 135 (8.4) | N/A | N/A |

| Non-vaccine-producing countries | 59 (3.6) | N/A | N/A |

| I do not know | 865 (54.1) | N/A | N/A |

| If you had to pay for the vaccine (ie, no longer free), would you pay for it? | 911 (56.9) | 514 (32.1) | 176 (11.0) |

*Neither easy nor difficult or have not tried yet.

†To help the society and for profit, or only for profit.

N/A, not applicable.

Vaccine acceptance in rural Bangladesh

Overall vaccine acceptance among study participants was very high (1521/1601, 95%) (table 1). Acceptance was higher in female compared with male (97% vs 93%, respectively, p=0.001), but lowest in the youngest age group (<30 years, 88%) compared with older age groups (30–50 years and >50 years, 97% and 96%, respectively) (p<0.001). Vaccine acceptance appeared to be lowest in those who were not married (82%, p<0.001). The prevalence of acceptance was similar across different education levels. In terms of employment status, acceptance was lowest in students or retirees (81%) compared with unemployed (94%) and employed/self-employed (94%) participants, and highest among housewives (97%). Higher BMI was positively associated with higher proportion of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance (normal: 92% vs obese: 97%, p=0.001). Non-smokers had the highest proportion of acceptance compared with former or current smokers (96%, 92% and 91%, respectively, p=0.001), while the prevalence was not significantly different among chewing tobacco users and non-users. In terms of clinical conditions, acceptance was lower among those with anxiety compared with those without (92% vs 95%, p=0.038), and similar trends were observed across different types of chronic diseases or presence of depressive symptom.

The reasons for acceptance among participants were primarily due to wanting to keep others safe (89%), followed by feeling socially pressured to get vaccinated (8%). The reasons for not wanting to get vaccinated among those who are hesitant included falling into an ineligible age category (28%), confident that their bodies could fight the virus naturally (24%) and wanting to see others take the vaccine first (20%). In terms of personal beliefs/attitude, 88% believed that there are benefits associated with being vaccinated from COVID-19. These included being protected from catching COVID-19 (82%), reaching herd immunity for the community to be safe (10%) and ability to travel domestically (5%).

The results from the stepwise multivariable logistic regression analysis (table 3) revealed that increased age (OR 4.4, 95% CI 2.4 to 8.2, p<0.001 to OR 5.2, 95% CI 2.5 to 10.7, p<0.001), being a housewife (OR 2.9, 95% CI 1.6 to 5.2, p=0.001) and underweight (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.0 to 9.7, p=0.043) were associated with higher COVID-19 vaccine acceptance. Participants with at least undergraduate qualifications were more likely to accept the vaccine (OR 3.6, 95% CI 1.0 to 12.7, p=0.045), while being a student or retiree reduced the likelihood by 60% (95% CI 0.1 to 0.9, p=0.029). The presence of anxiety or depressive symptom was associated with 50% reduced likelihood of vaccine acceptance. In terms of COVID-19-related factors, knowledge of the dosage (OR 3.2, 95% CI 1.5 to 6.9, p=0.003), where to register for the vaccine (OR 3.4, 95% CI 1.7 to 6.7, p=0.001) and where to get the vaccine (OR 5.0, 95% CI 1.2 to 20.5, p=0.026), as well as willingness to pay if the vaccine was no longer free (OR 3.1, 95% CI 1.8 to 5.4, p<0.001), were strongly correlated with vaccine acceptance. For personal belief, trust in the health department was important (OR 4.9, 95% CI 2.0 to 12.0, p=0.001). The results of simple logistic regression of vaccine acceptance are presented in online supplemental appendix 5, table S1.

Table 3.

Stepwise multivariable logistic regression of demographic, lifestyle, clinical and COVID-19-related correlates and COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and uptake in rural Bangladesh

| Variable | Vaccine acceptance | Received COVID-19 vaccine | ||

| OR (95% CI) | P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Demographics | ||||

| Sex (Ref: Male) | ||||

| Female | – | – | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.7) | 0.027 |

| Age group (Ref: <30 years) | ||||

| 30–50 years | 4.4 (2.4 to 8.2) | <0.001 | 2.7 (2.1 to 3.8) | <0.001 |

| >50 years | 5.2 (2.5 to 10.7) | <0.001 | 4.7 (3.3 to 6.7) | <0.001 |

| Education level (Ref: Illiterate) | ||||

| Primary | – | – | – | – |

| Secondary | – | – | – | – |

| Undergraduate and above | 3.6 (1.0 to 12.7) | 0.045 | – | – |

| Employment status (Ref: Unemployed) | ||||

| Employed | – | – | – | – |

| Housewife | 2.9 (1.6 to 5.2) | 0.001 | – | – |

| Students or retirees | 0.4 (0.1 to 0.9) | 0.029 | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.040 |

| Anthropometric and lifestyle behaviour | ||||

| BMI (kg/m²) (Ref: Normal) | ||||

| Underweight | 3.2 (1.0 to 9.7) | 0.043 | – | – |

| Overweight | – | – | 1.3 (1.0 to 1.7) | 0.021 |

| Obese | – | – | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.8) | 0.037 |

| Clinical conditions | ||||

| Have anxiety or depressive symptom (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 0.5 (0.3 to 0.9) | 0.003 | – | – |

| Attitude towards vaccination (in general terms) prior to COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

| Have been vaccinated previously, for example, for influenza (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | – | – | 0.7 (0.5 to 0.9) | 0.007 |

| Knowledge of COVID-19 vaccination | ||||

| Understood COVID-19 dosage (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 3.2 (1.5 to 6.9) | 0.003 | 17.0 (6.1 to 47.9) | <0.001 |

| Availability and potential barriers of getting COVID-19 vaccine | ||||

| Understood how to register for COVID-19 vaccine (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 3.4 (1.7 to 6.7) | 0.001 | 3.7 (2.4 to 5.6) | <0.001 |

| Understood where to get the vaccine (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 5.0 (1.2 to 20.5) | 0.026 | – | – |

| Would you take the vaccine if it is no longer free? (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 3.1 (1.8 to 5.4) | <0.001 | – | – |

| Influence of personal beliefs | ||||

| Do you trust the health department regarding information related to COVID-19 vaccine? (Ref: No) | ||||

| Yes | 4.9 (2.0 to 12.0) | 0.001 | – | – |

The following covariates were introduced into the model but were not statistically significant for both vaccine acceptance and uptake: marital status, smoking history, use of chewing tobacco, chronic disease, aware of benefits of vaccines, familiar with COVID-19 vaccine brands, trust in government.

BMI, body mass index.

Vaccine roll-out participation in rural Bangladesh

Half of the study participants have had at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine (table 1). The roll-out participation rate (ie, proportion of those who have received the vaccine) was similar across sex, but there was a clear upward trend in roll-out participation when stratified by age groups (26.3%–63.7%, p<0.001). Just over half (51.5%) of those who were married had received the vaccine, while 76.1% of unmarried participants had received it. Participation rate appeared to have decreased as education level increases (illiterate: 53.3% vs undergraduate and above: 39.2%, p=0.026). The proportion of those who have received the vaccine was similar according to smoking status, including among users/non-users of chewing tobacco or betel leaf. The prevalence of those who have been vaccinated was generally higher in those with comorbid conditions (48.1%–58.6%) than without (46.9%, p=0.022), but not significantly different when stratified by mental health conditions.

Out of 803 participants who have taken the first dose, 79.2% reported no side effects. Among these first-dose takers, 99.8% were planning to or already took their second vaccination dose. Of those who have taken the second dose (n=263), 99.6% were compliant (ie, were vaccinated according to the scheduled time), and 88.1% reported having no side effects. Most participants received the vaccines in district hospitals (76.3%) or government-registered clinics (22.5%).

Most common reasons of those who have not received the vaccine were a lack of interest (25.1%) and not within the eligible age category (18.9%). For those who have registered (or were intending to register) for the vaccine, participants either visited (or will be visiting) an internet café (61.6%), used their own or someone else’s smartphone (15.8%) or directly visited a government hospital (12.8%).

According to the stepwise multivariable logistic regression analysis (table 3), sociodemographic correlates of roll-out participation were female (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.7, p=0.027), increased age (OR 2.7, 95% CI 2.1 to 3.8, p<0.001 to OR 4.7, 95% CI 3.3 to 6.7, p<0.001) and being overweight or obese (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.7 and OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0 to 1.8, respectively). Students and retirees were 50% less likely to have been vaccinated than unemployed participants (95% CI 0.2 to 0.9, p=0.040). Interestingly, previous vaccination (prior to COVID-19) was associated with reduced likelihood of having received the vaccine (OR 0.7, 95% CI 0.5 to 0.9, p=0.007), while knowledge of the dosage (OR 17.0, 95% CI 6.1 to 47.9, p<0.001) and how to register for the vaccine (OR 3.7, 95% CI 2.4 to 5.6, p<0.001) were related to vaccine uptake. The results of simple logistic regression of vaccine uptake are presented in online supplemental appendix 5, table S1.

Discussion

This study assessed vaccine acceptance among people living in rural Bangladesh. Offline data collection methods were employed to account for the likelihood of lower digital literacy and/or access to online resources in the rural population. We found a high COVID-19 acceptance rate of 95% in rural Bangladesh 11 months since start of the roll-out programme in January 2021. This acceptance rate is substantially higher than findings from the general Bangladeshi population (51%–68%) at the initial phase of the roll-out5 15–18 and in a study conducted prior to the roll-out, which included 52% rural participants and reported 75% willingness rate.14 Our observed acceptance rate is further supported by a higher rate of COVID-19 vaccine uptake for at least one dose in rural Bangladesh compared with national data at the end of the data collection period (50% vs 36% in November 2021). Therefore, our findings suggest there has been an improvement in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance over time.

Our finding of an exceptionally high COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in rural Bangladesh contrasts a previous subanalysis of the general Bangladeshi population14 and countries with similar demographic profile such as India,30 where rural residents were more likely to mistrust vaccines. However, vaccine decisions are highly multifactorial and can change over time.31 32 A recent publication found that over 90% of the general Bangladeshi population had a positive change in attitude towards COVID-19 vaccines after receiving their vaccination.33 Importantly, Bangladesh recently met the 70% double-dose target supported by the WHO-led COVAX programme.34 Health campaigns conducted by the Bangladeshi government, non-profit organisations as well as local community champions have strongly contributed to improving vaccine literacy and diminishing the social stigma surrounding vaccination.35 Indeed, 11 months into the roll-out programme, we found that 89% of rural participants wanted to keep others safe and 88% agreed to the benefits of COVID-19 vaccines.

The main source of information among people in rural Bangladesh was the television and their relatives, and only 11% have used social media. This is again likely due to poor internet coverage and lower digital literacy among people residing in rural areas.19 Ironically, this may have been the very reason which prevented people from misinformation,36 thus explaining a slightly higher acceptance rate among social media non-users compared with users, and to the overall higher acceptance rate (table 2). Indeed, studies in sub-Saharan African countries31 and developed countries37 suggest COVID-19 vaccine-resistant individuals were more likely to obtain information from non-traditional and non-authoritative sources, such as social media or unofficial websites. Notably, a lack of internet access may have contributed to the slower start of vaccine uptake in Bangladesh during the initial roll-out period.7 This was mainly due to the requirement for online registration for the vaccines,9 which would have been difficult for those living in rural areas.

Trust in health department and practical knowledge (such as COVID-19 vaccine dosage, how to register for the vaccine and where to get vaccinated) were correlates of acceptance and/or uptake. The importance of knowledge in COVID-19 vaccine acceptance has been observed previously from studies in the general Bangladeshi population38 39 and is echoed globally.32 While previous data suggest substantial hesitancy due to knowledge of side effects from the COVID-19 vaccines,4 most participants who were hesitant or have not had their vaccines yet cited practical reasons (eg, not within the eligible age category or want to see others take it first).

A previous study demonstrated that people in rural Bangladesh have significantly lower levels of knowledge about COVID-19 and pandemic-appropriate behaviour.40 This is further reflected by significant proportion (54%) of rural residents who responded ‘I do not know’ when asked which country they were aware of and trust to produce the vaccine (table 2). In comparison, 70% of the general Bangladeshi population were aware of their vaccine source and manufacturer.39 Interestingly, in France, hesitancy was highest for vaccines manufactured in China and lowest for a vaccine manufactured in Europe.41 On the contrary, Chinese-made vaccines were well accepted among our participants (24%) compared with UK-made or US-made vaccines (1% and 8%, respectively). These findings highlight that population dynamics regarding vaccinations may vary depending on the levels of health literacy, societal norms, political climate as well as traditional culture.

Strengths and limitations

The strength of this study is the use of well-validated sampling methodologies, the large sample size, and the use of offline data collection methods. While online data collection methods are more efficient,42 people in rural areas lack access to online resources. Therefore, we strongly recommend future studies assessing the rural population in Bangladesh and other LMICs to conduct data collection methods in person.

This study is not without limitation. A cross-sectional design means we were unable to measure incidence and suggest causal inference. We also did not collect participant income data, thus were unable to assess its association with vaccine acceptance. Nonetheless, the methods and findings of this study are relevant in informing the development of diagnostic tools to assess vaccine acceptance or similar outcomes in rural areas. The results are also pertinent to inform policy in other low-income and low-resource countries.

Policy recommendations

We have identified a number of considerations for policymakers. Firstly, to further increase the vaccination rates (including boosters), policymakers must identify hard-to-reach population. Approximately 60% of older people have yet to be vaccinated in Bangladesh, mostly citing a lack of awareness of where to obtain the vaccine.35 Mobilising special teams to reach hard-to-reach communities directly may be crucial avenue to increase vaccination rates in these population groups.35 Secondly, our study showed that, rural Bangladeshis, despite faced with lower resource and access to healthcare information and infrastructure, recognised the need to be protected from COVID-19. Therefore, to ensure vaccine acceptance remains high in rural Bangladesh, health authorities should continue to support interventions aimed at increasing vaccine and general health literacy in rural areas. Thirdly, Bangladesh must ensure ongoing vaccine supply. This is currently well supported by the COVAX programme.34 However, there may be merit in expanding the funding and resource allocations for alternative avenues to guarantee procurement,43 such as by having locally produced vaccines. This would reduce the reliance on and defuse political issues with supplier countries (such as India, China and Russia) in relation to vaccine supply,44 and empower local pharmaceutical companies to invest in vaccine development. Finally, to prepare for future health emergencies, there remains a need to promote LMICs to be on top of priority list for vaccine and other healthcare supply distribution, and a wider acknowledgement and implementation of mitigation strategies to combat ‘resource hoarding’ by developed countries, as observed with the COVID-19 vaccines.45

Conclusions

In conclusion, COVID-19 vaccine acceptance is very high in rural Bangladesh, and COVID-19 vaccine literacy is associated with both its acceptance and uptake. Measures undertaken at the national, divisional, district and local levels in Bangladesh should be directed to increase vaccine literacy and ensure ongoing vaccine supply and improvement in healthcare infrastructure, particularly for those living in rural areas.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @Md. Shariful Islam

Contributors: FS, BB, BNS, AS and OB designed the survey. MRKC, MSI, LA and HAC collected and managed the data. SMA, FS and AA analysed the data under BB’s supervision. FS drafted the manuscript. BB, BNS, AS, OB, MRKC, MSI, HAC, AA, LA and SMA revised the manuscript and provided intellectual input. BB led this study and accepts full responsibility for the work and/or the conduct of the study, had access to the data, and controlled the decision to publish.

Funding: FS is supported by an Alfred Deakin Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (Deakin University).

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

This study involves human participants and was approved by Monash University Human Research Ethics Committee (Project ID: 29358). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

References

- 1.How COVID vaccines shaped 2021 in eight powerful charts. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-03686-x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Dror AA, Eisenbach N, Taiber S, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: the next challenge in the fight against COVID-19. Eur J Epidemiol 2020;35:775–9. 10.1007/s10654-020-00671-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Salmon DA, Dudley MZ, Glanz JM, et al. Vaccine hesitancy: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Vaccine 2015;33 Suppl 4:D66–71. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.09.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Solís Arce JS, Warren SS, Meriggi NF, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance and hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries. Nat Med 2021;27:1385–94. 10.1038/s41591-021-01454-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawlader MDH, Rahman ML, Nazir A, et al. COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in South Asia: a multi-country study. Int J Infect Dis 2022;114:1–10. 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.09.056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhopal S, Nielsen M. Vaccine hesitancy in low- and middle-income countries: potential implications for the COVID-19 response. Arch Dis Child 2021;106:113–4. 10.1136/archdischild-2020-318988 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations: Bangladesh. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 8.Achieving 70% COVID-19 Immunization Coverage by Mid-2022. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-12-2021-achieving-70-covid-19-immunization-coverage-by-mid-2022

- 9.Khatun F. The Covid-19 vaccination agenda in Bangladesh: Increase supply, reduce hesitancy. In: ORF special report. Bangladesh, 2021: 18. [Google Scholar]

- 10.COVID vaccines to reach poorest countries in 2023 — despite recent pledges. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-01762-w [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Coronavirus (COVID-19) vaccinations. Available: https://ourworldindata.org/covid-vaccinations

- 12.Tangcharoensathien V, Bassett MT, Meng Q, et al. Are overwhelmed health systems an inevitable consequence of covid-19? experiences from China, Thailand, and new York state. BMJ 2021;372:n83. 10.1136/bmj.n83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tracking SARS-CoV-2 variants. Available: https://www.who.int/activities/tracking-SARS-CoV-2-variants

- 14.Abedin M, Islam MA, Rahman FN, et al. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 among Bangladeshi adults: understanding the strategies to optimize vaccination coverage. PLoS One 2021;16:e0250495. 10.1371/journal.pone.0250495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ali M, Hossain A. What is the extent of COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Bangladesh? A cross-sectional rapid national survey. BMJ Open 2021;11:e050303. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-050303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Khan IA, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccine and its determinants in Bangladesh. arXiv 2021:2103.15206. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hossain E, Rana J, Islam S, et al. COVID-19 vaccine-taking hesitancy among Bangladeshi people: knowledge, perceptions and attitude perspective. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2021;17:4028–37. 10.1080/21645515.2021.1968215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bari MS, Hossain MJ, Ahmmed F, et al. Knowledge, perception, and willingness towards immunization among Bangladeshi population during COVID-19 vaccine rolling period. Vaccines 2021;9:1449. 10.3390/vaccines9121449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.54% Bangladeshi rural households lack internet access: survey. Available: https://www.thedailystar.net/country/news/54-bangladeshi-rural-households-lack-internet-access-survey-1960661

- 20.Share of rural population in Bangladesh from 2010 to 2019. Available: https://www.statista.com/statistics/760934/bangladesh-share-of-rural-population/#:~:text=In%202019%2C%20approximately%2062.6%20percent,in%20rural%20areas%20in%202010

- 21.Joarder T, Rawal LB, Ahmed SM, et al. Retaining doctors in rural Bangladesh: a policy analysis. Int J Health Policy Manag 2018;7:847–58. 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kish L. A procedure for objective Respondent selection within the household. J Am Stat Assoc 1949;44:380–7. 10.1080/01621459.1949.10483314 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Khalequzzaman M, Chiang C, Choudhury SR, et al. Prevalence of non-communicable disease risk factors among poor shantytown residents in Dhaka, Bangladesh: a community-based cross-sectional survey. BMJ Open 2017;7:e014710. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.MacDonald NE, SAGE Working Group on Vaccine Hesitancy . Vaccine hesitancy: definition, scope and determinants. Vaccine 2015;33:4161–4. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.04.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16:606–13. 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dhira TA, Rahman MA, Sarker AR, et al. Validity and reliability of the generalized anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among university students of Bangladesh. PLoS One 2021;16:e0261590. 10.1371/journal.pone.0261590 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chowdhury AN, Ghosh S, Sanyal D. Bengali adaptation of brief patient health questionnaire for screening depression at primary care. J Indian Med Assoc 2004;102:544–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dubé Ève, Ward JK, Verger P, et al. Vaccine Hesitancy, acceptance, and Anti-Vaccination: trends and future prospects for public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2021;42:175–91. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-102240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Danabal KGM, Magesh SS, Saravanan S, et al. Attitude towards COVID 19 vaccines and vaccine hesitancy in urban and rural communities in Tamil Nadu, India - a community based survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21:994. 10.1186/s12913-021-07037-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kanyanda S, Markhof Y, Wollburg P, et al. Acceptance of COVID-19 vaccines in sub-Saharan Africa: evidence from six national phone surveys. World Bank Group, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lazarus JV, Ratzan SC, Palayew A, et al. A global survey of potential acceptance of a COVID-19 vaccine. Nat Med 2021;27:225–8. 10.1038/s41591-020-1124-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hossain ME, Islam MS, Rana MJ, et al. Scaling the changes in lifestyle, attitude, and behavioral patterns among COVID-19 vaccinated people: insights from Bangladesh. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2022;18:2022920. 10.1080/21645515.2021.2022920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNICEF . 190 million COVID-19 vaccines delivered under COVAX. Available: https://www.unicef.org/bangladesh/en/press-releases/unicef-190-million-covid-19-vaccines-delivered-under-covax

- 35.UNICEF . Bangladesh’s COVID-19 vaccination rate has soared in a year 2022.

- 36.Swire-Thompson B, Lazer D. Public health and online misinformation: challenges and recommendations. Annu Rev Public Health 2020;41:433–51. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-040119-094127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murphy J, Vallières F, Bentall RP, et al. Psychological characteristics associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and resistance in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Nat Commun 2021;12:29. 10.1038/s41467-020-20226-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mahmud S, Mohsin M, Khan IA, et al. Knowledge, beliefs, attitudes and perceived risk about COVID-19 vaccine and determinants of COVID-19 vaccine acceptance in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2021;16:e0257096. 10.1371/journal.pone.0257096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Islam MR, Hasan M, Nasreen W, et al. The COVID-19 vaccination experience in Bangladesh: findings from a cross-sectional study. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol 2021;35:20587384211065628. 10.1177/20587384211065628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rahman MS, Karamehic-Muratovic A, Amrin M, et al. COVID-19 epidemic in Bangladesh among rural and urban residents: an online cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitudes, and practices. Epidemiologia 2021;2:1–13. 10.3390/epidemiologia2010001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwarzinger M, Watson V, Arwidson P, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in a representative working-age population in France: a survey experiment based on vaccine characteristics. Lancet Public Health 2021;6:e210–21. 10.1016/S2468-2667(21)00012-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lefever S, Dal M, Matthíasdóttir Ásrún. Online data collection in academic research: advantages and limitations. British Journal of Educational Technology 2007;38:574–82. 10.1111/j.1467-8535.2006.00638.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tagoe ET, Sheikh N, Morton A, et al. COVID-19 vaccination in lower-middle income countries: National stakeholder views on challenges, barriers, and potential solutions. Front Public Health 2021;9:709127. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.709127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stupor in vaccine production: Bangladesh inhibited? Available: https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/stupor-in-vaccine-production/

- 45.The fight to manufacture COVID vaccines in lower-income countries. Available: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-021-02383-z [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-064468supp001.pdf (240.8KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

All data relevant to the study are included in the article or uploaded as supplementary information.