Abstract

Purpose

Chemotherapy can cause hiccups but few randomized controlled trials have focused on hiccups. This trial examined the feasibility of such research.

Methods

This single-institution, multi-site trial used phone recruitment for patients: (1) 18 years or older, (2) able to speak/read English, (3) with a working e-mail address, (4) with hiccups 4 weeks prior to contact, and (5) with ongoing oxaliplatin or cisplatin chemotherapy. The primary outcome was feasibility. Patients were randomly assigned to one of two sets of educational materials, each of which discussed hiccups and palliative options. The experimental materials were almost identical to the standard materials but provided updated content based on the published medical literature. At 2 weeks, patients responded by phone to a 5-item verbally administered questionnaire.

Results

This trial achieved its primary endpoint of recruiting 20 eligible patients within 5 months; 50 patients were recruited in 3 months. Among the 40 patients who completed the follow-up questionnaire, no statistically significant differences between arms were observed in hiccup incidence since initial contact, time spent reviewing the educational materials, and the troubling nature of hiccups. Twenty-five patients tried palliative interventions (13 in the experimental arm and 12 in the standard arm), most commonly drinking water or holding one’s breath. Eleven and 10 patients, respectively, described hiccup relief after such an intervention.

Conclusions

Clinical trials for chemotherapy-induced hiccups are feasible and could address an unmet need.

Keywords: Trial, Hiccups, Education, Randomized, Feasibility

Introduction

Commonly prescribed chemotherapy drugs, such as oxaliplatin and cisplatin, appear to cause hiccups, particularly when administered with dexamethasone [1–3]. Chemotherapy-induced hiccups are estimated to occur in 15–40% of patients [2, 4]. Although typically self-limited, hiccups can recur and thereby generate a cumulative burden of symptomatology [5]. These recurrent episodes of hiccups can be particularly concerning because each bout puts patients at risk for sleep deprivation, fatigue, aspiration, and other related complications [5].

Despite their problematic nature, hiccups are understudied. To our knowledge, only 3 published randomized, controlled trials—the gold standard for testing the efficacy of an intervention—have focused on hiccup palliation specifically [6–8]. First, Zhang and others conducted a randomized, 30-patient placebo-controlled trial in stroke patients and reported that baclofen resulted in a statistically significant reduction in hiccups [6]. Similar favorable findings from Ramirez and others were reported in a 4-patient, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover study with baclofen [7]. Finally, Wang and Wang conducted a placebo-controlled trial with metoclopramide in 36 patients who had intractable hiccups, reporting that this agent resulted in a statistically significant reduction in hiccups [8].

Although the above three trials are clinically important, they underscore the limitations of research on hiccups. First, with respective sample sizes of 30, 4, and 36 patients, these randomized trials are perhaps too small to provide definitive conclusions. Second, these trials point to a paucity of research specifically related to chemotherapy-induced hiccups, as none of these trials addressed this cyclical cause of hiccups. Third, to our knowledge, these are the only randomized trials to have been conducted for hiccups over the span of decades. Lastly, although recent observational studies have suggested that interventions, such as a forced inspiratory suction tool and a novel sour-tasting oral lollipop formulation might palliate hiccups, these other remedies have yet to be tested within the context of the gold standard of a randomized, double-blinded trial [9, 10].

The trial reported here was conducted to assess the feasibility of a randomized, double-blinded trial for hiccups in chemotherapy-treated patients with cancer. This trial tested a standard set of educational materials (control arm) versus an updated set of educational materials (experimental arm) [9, 10]. The demonstration of feasibility of conducting clinical trials for hiccups could conceivably lead to more research, the rigorous testing of newer novel interventions, and palliation for cancer patients who suffer from recurrent chemotherapy-induced hiccups.

Methods

Trial design and oversight

The Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) approved this trial (#21–012,057), which relied on the Mayo Clinic’s multi-site catchment area of Minnesota, Arizona, Florida, Wisconsin, and Iowa. This trial was registered on www.clinicatrials.gov (NCT05313685). The trial used patient phone contact and electronic communication for recruitment and capture of endpoint data.

Eligibility criteria

Patient eligibility criteria were comprised of the following: (1) 18 years or older, (2) able to speak and read in English, (3) has an e-mail address, (4) patient-reported hiccups 4 weeks prior to patient contact, and (5) planned ongoing chemotherapy with either oxaliplatin or cisplatin. The rationale for this last criterion is the assumption that chemotherapy-induced hiccups would recur with ongoing chemotherapy (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Consort diagram. The consort diagram shows how eligibility criteria gave rise to the cohorts and shows dropouts per arm

Recruitment

The electronic medical record was searched every weekday to identify potentially eligible patients, who were then contacted by phone with a caller identification that showed Mayo Clinic as the caller. Upon phone contact, an IRB-approved script was used to describe the trial to each potential enrollee. If the patient expressed interest, a study team member confirmed eligibility, including patient-reported hiccups within the required interval, obtained oral consent, and then acquired the patient’s signature on a Health Insurance Portability Accountability Act (HIPAA) form either electronically or via regular mail.

Educational intervention, arm assignment, double-blinding, and acquisition of patient-reported data

The interventions were two different sets of educational materials that consisted of 5–6 pages of double-spaced content that explained hiccup pathophysiology, causes, risk factors, complications, and palliation (prescribed medical and interventional therapy as well home remedies) [11]. Each educational intervention was provided to patients electronically as a Portable Document Format (PDF) document. Patients were assigned one of two versions: a publically available, Mayo Clinic-written document which was considered the standard intervention versus the same document, which was considered the experimental intervention and included the following wording of updated information on more recent interventions for hiccups [9–11]:

Just about everyone has had hiccups, but some people get them more often and are more troubled by them. If you feel hiccups have been difficult for you, it would be important for you to contact your team of healthcare providers to let them know. This document provides educational information on hiccups. A few recent updates that you could try at home include the following. A recent large study suggested that interventions, such as drinking from a straw may help with hiccups. This has not been proven for sure. Some smaller studies and reports suggest that trying a sour food, such as sucking on a piece of lemon, might help hiccups. This has not been proven for sure.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of these two interventions. A computer-generated list of random numbers was used to determine arm allocation. Based on the randomization code, each PDF file was assigned a number, which, in turn, was assigned consecutively to each enrolled patient. Each PDF file was constructed and labeled to make it impossible to discern arm allocation; the study team member, who recruited patients, who e-mailed the PDF file to patients, and who acquired secondary outcome measures, remained blinded throughout all patient interactions. Similarly, in view of the nature of the intervention, each patient was unable to discern arm allocation throughout the trial.

Patients were then called by phone within 14 days of receipt of their allocated educational materials. This interval was mandated per protocol based on previous data that suggest optimal patient recall of symptoms within this time frame [12]. Patients were then asked to complete a verbally administered questionnaire to assess the secondary endpoints, as described in further detail below. The study team attempted to contact patients shortly after they had received chemotherapy, as chemotherapy was presumed to be the cause of the hiccups.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was feasibility. Based on review of the published literature and institutional patient volumes, the study team defined enrollment of 20 eligible patients within 5 months of trial initiation as success and thereafter allowed for enrollment of up to 50 total patients [6–8]. Enrollment was defined as the acquisition of oral consent and a patient signature on a submitted HIPAA document.

Secondary endpoints were derived from a 5-item questionnaire, which had undergone multiple iterations for face validity by study team members and others and which relied, in part, on a numeric rating scale [13–15]: 1) “Have you had hiccups since you signed up for this study?,” which required a “yes” or “no” response; (2) “How much time did you spend reviewing the educational materials on hiccups?,” with 5 response options (1 = little to no time to 5 = a lot of time), as per a numeric rating scale; (3) “How troubling were your hiccups since you signed up for this study?,” with 5 response options (1 = little to no trouble to 5 = severe hiccups); (4) “Since you signed up for this study, what did you try to stop or prevent hiccups?” with choices of “nothing,” “drinking from a straw,” “tasting something sour,” “medication from a healthcare provider” (to be specified), and “other” (to be specified); and (5) “Since you signed up for the study, what helped stop or prevent your hiccups the most?” (choices were the same as question 4).

Patients provided phone responses, which an investigator recorded on case report forms. Descriptive patient demographics were also acquired during phone encounters and during medical record review.

Analyses

The primary endpoint was feasibility, as defined above. Because 30% of patients are likely to report symptoms as less troubling based on a placebo effect, report of less troubling symptoms in 70% of patients was considered clinically meaningful in the experimental arm and therefore worthy of further testing of these educational materials in a larger trial [16, 17]. Fifty patients enabled detection of a type 1 error of < 0.05 with 80% power. Questionnaire numeric response categories 1–2 and 3–5 were combined for questions 2 and 3, and a 2-tailed Fisher’s exact test was used to assess differences between arms. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Demographics

A total of 50 patients were enrolled. The median age was 63 years (range: 24, 85 years). Thirty-eight patients (76%) were men. All received concomitant dexamethasone. Demographics as per arm appear in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics; n = 50

| DEMOGRAPHIC | Number of patients with EXPERIMENTAL educational materials n = 25 (%) |

Number of patients with REGULAR educational materials n = 25 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Median age in years (range) | 68 (24, 85) | 61 (36, 80) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 17 (68) | 21 (84) |

| Female | 8 (32) | 4 (16) |

| Cancer type | ||

| Colorectal | 7 (28) | 6 (24) |

| Genitourinary | 6 (24) | 2 (8) |

| Pancreatic | 1 (4) | 6 (24) |

| Gastroesophageal | 2 (8) | 4 (16) |

| Head and neck | 2 (8) | 3 (12) |

| Cholangiocarcinoma | 3 (12) | 2 (8) |

| Lung | 2 (8) | 1 (4) |

| Gynecological | 1 (4) | 1 (4) |

| Other | 1 (4) | 0 |

| Chemotherapy** | ||

| Oxaliplatin + other chemotherapy agents | 12 (48) | 16 (64) |

| Cisplatin + other chemotherapy agents | 11 (44) | 5 (20) |

| Cisplatin (single agent) | 2 (8) | 4 (16) |

*Numbers in parentheses refer to percentages unless otherwise specified

**All patients received concomitant dexamethasone

Primary endpoint

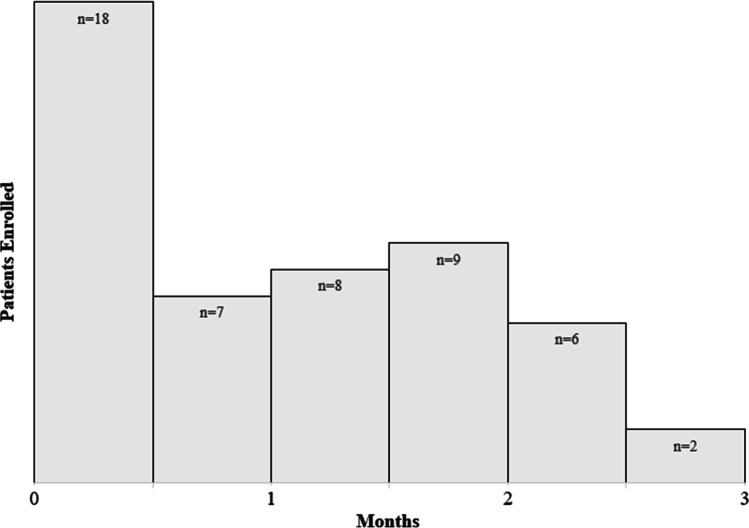

The first 20 patients were enrolled within 24 days. All 50 patients were enrolled within 3 months (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Patient recruitment over time. The first 20 eligible patients were recruited within the first month of the trial. All 50 eligible patients were recruited within 3 months

Secondary endpoints

Among the 40 patients who completed the follow-up questionnaire, per the study protocol, no statistically significant differences in hiccup incidence were observed between arms. Similarly, no statistically significant differences were observed between arms in time spent reviewing the educational materials and in the troubling nature of hiccups (Table 2).

Table 2.

Secondary patient-reported outcomes

| QUESTION | EXPERIMENTAL educational materials n = 19 (%) |

REGULAR educational materials n = 21 (%) |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Have you had hiccups since you signed up for this study? | |||

| Yes | 16 (84) | 17 (81) | 0.79 |

| No | 3 (16) | 4 (19) | |

| How much time did you spend reviewing the educational materials on hiccups? | |||

| Little to no time (categories 1 and 2) | 13 (68) | 9 (42) | 0.10 |

| A lot of time (categories 3, 4, and 5) | 6 (32) | 12 (57) | |

| How troubling were your hiccups since you signed up for this study? | |||

| Little to no trouble (categories 1 and 2) | 15 (79) | 17 (81) | 0.94 |

| Severe hiccups (categories 3, 4, and 5) | 4 (21) | 4 (19) |

A subgroup of patients reported their hiccups as severe. Among patients assigned to the experimental arm, one patient rated his hiccup severity with a 5, or “severe hiccups.” Three in the experimental arm provided a rating of 3 for hiccup trouble/severity. In the standard arm, 2 patients rated their hiccup trouble/severity with a 5, one with a 4, and one with a 3.

For hiccup palliation, 25 patients tried various interventions, (namely, 13 in the experimental arm and 12 in the standard arm). Some of these interventions had been described in the educational materials (Table 3). Eleven and 10 patients, respectively, described hiccup relief with the tried interventions.

Table 3.

Patient-attempted interventions for hiccup palliation

| Trial arm 1 = experimental 2 = regular* |

Interventions attempted | Did the intervention(s) help? |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Small sips of water with no straw | Yes |

| 1 | Breathing exercises | Yes |

| 1 | Standing upright, eating ice, drinking water with no straw | No |

| 1 | Slow eating | Yes |

| 1 | Eating slowly | Yes |

| 1 | Holding one’s breath, taking a deep breath, walking | Yes, walking |

| 1 | Holding one’s breath | Yes |

| 1 | Breathing exercises | Yes |

| 1 | Gabapentin, olanzapine, holding breath | Yes, to olanzapine |

| 1 | sips of water | No |

| 1 | Baclofen, eating peanut butter, drinking water with one’s head back | Yes, to baclofen |

| 1 | Tasting something sour, baclofen, chlorpromazine, positional drinking, exercising (pushups), holding one’s breath, breathing into a bag | Yes, to exercise (pushups) |

| 1 | Drinking water without a straw | Yes |

| 2 | Drinking water with no straw and holding breath | No |

| 2 | Drinking water with no straw and taking peppermint | Yes |

| 2 | Sipping water with no straw, placing head between legs | No |

| 2 | Limiting carbonated beverages, eating more slowly | Yes, to limiting carbonated beverages |

| 2 | Drinking from a straw | Yes |

| 2 | Ondansetron, prochlorperazine | Yes |

| 2 | Holding one’s breath, focusing on something else | Yes |

| 2 | Drinking from a straw, holding one’s breath | Yes, to drinking from a straw |

| 2 | Drinking from a straw, holding one’s breath | Yes, to holding one’s breath |

| 2 | Holding one’s breath | yes |

| 2 | Prilosec, prochlorperazine, positional changes, drinking water | Yes, to prochlorperazine, and positional changes |

| 2 | Drinking from a straw, chewing gum | Yes, to chewing gum |

*Each row denotes the response from a specific patient; the other 15 patients responded with “nothing” with respect to trying an intervention

Discussion

This 50-patient clinical trial is perhaps the largest, completed randomized double-blinded trial that focuses on hiccup palliation [6–8]. Of note, Go and others conducted a 65-patient trial on rotational corticosteroids, but that 14-site trial appeared to be aimed more at understanding whether dexamethasone was truly a cause of hiccups (“to prove the inequality of hiccup intensity”) as opposed to testing palliative interventions for hiccups [18]. The current single-institution trial did in fact achieve its primary endpoint of feasibility, thereby demonstrating that clinical trials for hiccup palliation can be conducted expeditiously, particularly in patients with cancer. Although the secondary trial results did not suggest that the experimental educational materials for hiccups are more effective at palliation than the standard educational materials and therefore not worthy of further testing, some patients did resort to the interventions in their assigned educational materials, albeit with mixed palliative success. Nonetheless, the important lessons gleaned from the current trial are that chemotherapy-treated patients experience hiccups, most appear to develop recurrent hiccups after further chemotherapy, some report their hiccups to be severe, and a notable proportion are willing to participate in a clinical trial that focuses on hiccup palliation. Taken together, these findings underscore the feasibility—as well as perhaps the need—for further research to palliate hiccups in chemotherapy-treated patients with cancer.

One can only speculate on reasons for this paucity of research on hiccups. The assumption that everyone—including babies in utero—experience hiccups makes this symptomatology less likely to be viewed as pathologic or notably troubling both by patients and healthcare providers. Additionally, the cyclical nature of hiccups, which seem to occur shortly after chemotherapy, might result in patients’ forgetting to discuss their hiccups 2–4 weeks later at an upcoming clinic visit, particularly if other more pressing matters, such as cancer status, are to be discussed. Although hiccups might not be patients’ gravest issue in the setting of cancer, this trial does suggest hiccups are bothersome—particularly for some—to the point that patients are willing to enroll in research aimed at their palliation.

This feasibility trial provides at least six lessons that might guide future research. First, it is noteworthy that patients with less troubling hiccups (graded as 1–2 of 5) were interested in enrolling in this trial. Although these patients’ hiccups might not be as distressing, perhaps the inconvenience of hiccups might sway patients with even milder symptoms to consider trial participation. Thus, future trials might consider the implementation of broad eligibility criteria. Second, this apparent trivialization of hiccups on the part of both patients and healthcare providers suggests a need to contact patients, ask about hiccups, and, if present, offer trial enrollment. This direct approach, which did not rely on referral from healthcare providers or on medical record review for hiccup documentation, likely accounts for the success of the current trial and should be considered for future hiccup trials. Third, importantly, most patients—over 80%—who reported hiccups at baseline and were therefore eligible for the trial, did in fact experience recurrent hiccups. This finding suggests that, in patients who are receiving chemotherapy, prior hiccups are a predictor of future hiccups and should be considered an eligibility criterion for future trials. Fourth, despite a short follow-up of 2 weeks, the dropout rate in this trial is high at 20%. The fact that these patients have cancer and are therefore at risk for other emerging issues—such as being diagnosed with symptomatic COVID-19, as occurred in one patient—speaks to the challenges of conducting this research in ill patients. In this context, future clinical trials should plan for high dropout rates of 20% of greater. Fifth, if such educational materials are used in future research, it might be important to gain a better sense of whether patients are actually reading the materials and implementing what they have learned from such materials. Assessment materials that acquire such patient-reported information would be important. Furthermore, researchers might focus on the burden-related aspects of such materials—their word count and complexity of content—to make sure that such materials are truly easy for patients to read and understand. Finally, timing is important. In view of the episodic nature of hiccups after chemotherapy, future interventions should be readily available to patients, in the same manner as antiemetics. The success of an intervention would need to enable expeditious access to the intervention at the time hiccups start. Similarly, the transient nature of hiccups is such that the success of an intervention should be assessed within the context of a control arm, as tested here, as otherwise the fleeing nature of hiccups might be erroneously attributed to the success of an intervention. Importantly, it should be noted that future hiccup interventions, which are particularly complicated, difficult to access, or medications fraught with severe side effects, might not accrue patients as readily as the trial reported here.

In summary, this trial demonstrates the feasibility of conducting clinical trials in chemotherapy-treated patients with hiccups or at risk for hiccups. This trial provides an important platform to facilitate further research of an understudied adverse event with the goal of lessening the suffering and morbidity of patients with cancer.

Acknowledgements

Dr. Jatoi is the Betty J. Foust, M.D. and Parents’ Professor; this endowment helped fund this research.

Author contribution

All the authors contributed equally to this research, helped formulate the study design, gather the data, analyze the data, and write the manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by institutional funds.

Data availability

The data and material associated with this work will not be available due to confidentiality.

Code availability

N/A.

Declarations

Ethics approval

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Consent to participate

All patients provided appropriate consent prior to participating in this research.

Consent for publication

All patients were aware of the intention to publish this research.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Jatoi had served as a consultant for Meterhealth.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hosoya R, Uesawa Y, Ishii-Nozawa R, Kagaya H. Analysis of factors associated with hiccups based on the Japanese Adverse Drug Event Report database. PLoS One. 2017;12(2):e0172057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0172057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liaw CC, Wang CH, Chang HK, Wang HM, Huang JS, Lin YC, Chen JS. Cisplatin-related hiccups: male predominance, induction by dexamethasone, and protection against nausea and vomiting. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30(4):359–366. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ehret CJ, Le-Rademacher JG, Martin N, Jatoi A (2021) Dexamethasone and hiccups: a 2000-patient, telephone-based study. BMJ Support Palliat Care bmjspcare-2021–003474. 10.1136/bmjspcare-2021-003474 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Ehret C, Young C, Ellefson CJ, Aase LA, Jatoi A. Frequency and symptomatology of hiccups in patients with cancer: using an on-line medical community to better understand the patient experience. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2022;39(2):147–151. doi: 10.1177/10499091211006923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hendrix K, Wilson D, Kievman MJ, Jatoi A. Perspectives on the medical, uality of life, and economic consequences of hiccups. Curr Oncol Rep. 2019;21(12):113. doi: 10.1007/s11912-019-0857-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang C, Zhang R, Zhang S, Xu M, Zhang S. Baclofen for stroke patients with persistent hiccups: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Trials. 2014;22(15):295. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ramírez FC, Graham DY. Treatment of intractable hiccup with baclofen: results of a double-blind randomized, controlled, cross-over study. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87(12):1789–1791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang T, Wang D. Metoclopramide for patients with intractable hiccups: a multicentre, randomised, controlled pilot study. Intern Med J. 2014;44(12a):1205–1209. doi: 10.1111/imj.12542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alvarez J, Anderson JM, Snyder PL, Mirahmadizadeh A, Godoy DA, Fox M, Seifi A. Evaluation of the forced inspiratory suction and swallow tool to stop hiccups. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(6):e2113933. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.13933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ehret CJ, Jatoi A (2022) Establishing the groundwork for clinical trials with Hiccupops® for hiccup palliation. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 39(10):1210–1214. 10.1177/10499091211063821 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/hiccups/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20352618. Accessed 18 Apr 2022

- 12.Lawson A, Tan AC, Naylor J, Harris IA. Is retrospective assessment of health-related quality of life valid? BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;21(1):415. doi: 10.1186/s12891-020-03434-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yesilyurt M, Faydali S. Evaluation of patients using numeric pain-rating scales. Int J Caring Sci. 2021;14:890–897. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hjermstad MJ, Fayers PM, Haugen DF, et al. Studies comparing numerical rating scales, verbal rating scales, and visual analogue scales for assessment of pain intensity in adults: a systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;41:1073–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee MK, Schalet BD, Cella D, et al. Establishing a common metric for patient-reported outcomes in cancer patients: linking patient reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS), numerical rating scale, and patient-reported outcomes version of the common terminology criteria for adverse events (PRO-CTCAE) J Patient Rep Outcomes. 2020;4:106. doi: 10.1186/s41687-020-00271-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Junior PNA, Barreto CMN, Cubero DIG, del Giglio A. The efficacy of placebo for the treatment of cancer-related fatigue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2020;28:1755–1764. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-04977-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chvetozoff G, Tannock IF. Placebo effects in oncology. J National Cancer Inst. 2003;95:19–29. doi: 10.1093/jnci/95.1.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Go SI, Koo DH, Kim ST, Song HN, Kim RB, Jang JS, Oh SY, Lee KH, Lee SI, Kim SG, Park LC, Lee SC, Park BB, Ji JH, Yi SY, Lee YG, Yun J, Bruera E, Hwang IG, Kang JH. Antiemetic corticosteroid rotation from dexamethasone to methylprednisolone to prevent dexamethasone-induced hiccup in cancer patients treated with chemotherapy a randomized, single-blind, crossover phase III trial. Oncologist. 2017;22(11):1354–1361. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2017-0129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data and material associated with this work will not be available due to confidentiality.

N/A.