Abstract

Objective

To investigate inequalities of health insurance coverage (outcome) at subnational level, and the effects of education and poverty on the outcome.

Design

Secondary analysis of Demographic and Health Surveys. The outcome variable was health insurance ownership.

Setting

The Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Subjects

Women aged 15–49 years (n=18 827).

Results

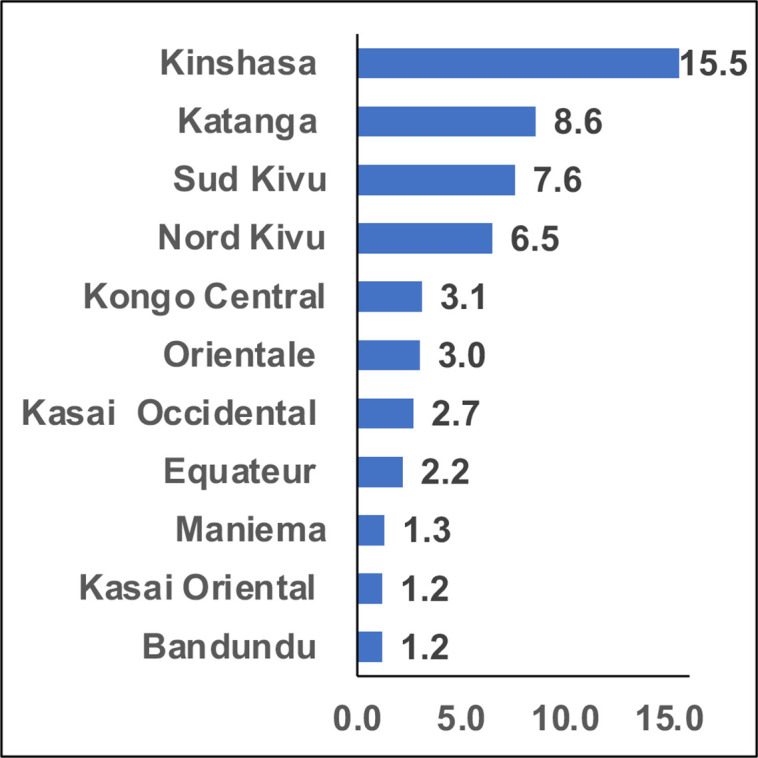

Findings indicated significant spatial variations of the health insurance ownership which ranged from 1.2% in Bandundu and Kasaï Oriental to 15.5% in Kinshasa the Capital City. Furthermore, findings showed that an additional year of women education increased by 10% the chance of health insurance ownership (adjusted OR, AOR 1.098; 95% CI 1.065 to 1.132). Finally, living in better-off households increased by 150% the chance of owing a health insurance (AOR 2.501; 95% CI 1.620 to 3.860) compared with women living in poor households.

Conclusions

Given the low levels of health insurance coverage, the Democratic Republic of the Congo will not reach the Sustainable Development Goal 3, aimed at improving maternal and child health unless a serious programmatic health shift is undertaken in the country to tackle inequalities among poor and uneducated women via universal health coverage.

Keywords: PUBLIC HEALTH, Community child health, Maternal medicine

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

This paper used nationally representative data to disentangle inequalities of access to health insurance at subnational level.

The cross-sectional nature of the data in the Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) limits the over-generalisation of the findings, making it impossible to infer causation between poverty, education and health insurance ownership.

To better capture inequalities of health insurance coverage in the country, oversampling of women of reproductive ages in other provinces is necessary.

Data collected in the DHSs may suffer from recall bias given the retrospective nature of self-reported health insurance coverage among women.

Introduction

Health insurance serves as a protective mechanism in pooling financial resources of participants to reduce the burden of out-of-pockets expenditures, which usually result in massive financial barriers and impoverished life in the households.1 2 Previous studies pinpointed the financial hardship of individuals and households resulting from a suboptimal health insurance coverage. They showed that direct healthcare spending in sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) is high and accounted for 27% in Ghana,3 4 37% in Ethiopia5 and 42% in Kenya.6 Yet health insurance is pivotal for SSA countries to achieve universal healthcare and the reduction of maternal mortality.7 8 For instance, studies from India found that health insurance promotes access to healthcare utilisation and promotes equity.9 10 Furthermore, the inpatient rates of poor insured persons were 16.4% higher than poor uninsured persons.

In SSA, previous research found significant variations across countries in terms of health insurance coverage.7 Indeed, health insurance coverage ranged from less than 1% in Chad to 62.4% in Ghana. This calls for context-specific or country-specific analyses to better understand individual-level and community-level characteristics associated with health insurance coverage. Ironically, while Japan is celebrating its 50th anniversary of UHC11 12 and countries such as Thailand and South Korea celebrate 30 years of UHC,13 14 alarmingly a marginal 8.5% of women of reproductive ages in SSA have access to health insurance.7 As a result, most SSA countries did not achieve Millennium Development Goals.15 16 Very likely, most SSA countries will not achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).17 Yet the United Nations (UN) sought to promote ‘Health for all at all ages’ by 2030, as reflected in the SDG 3.

Recent experiences in SSA countries showed promising results in expanding health insurance to community members.3 18–22 Evidence suggests that political involvement, good governance and specifically strong and dynamic leadership are crucial to ensure the expansion of health insurance in SSA countries, and especially in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) where health insurance coverage is extremely low at 5% among women of reproductive ages.7 23 There is currently no publicly owned insurer,2 24 25 making it more difficult to own health insurance given the high unemployment rates in the country since most health insurance schemes are offered through the employer’s plan.

Social determinants of health as a conceptual framework to analyse optimal health insurance coverage

This paper draws from the social determinants of health (SDoH) to better understand the effects of poverty and education on health insurance coverage in the DRC. The first generation of studies on population health emphasised medical conditions to understand how the health of populations are shaped over time.26 These studies showed significant drawbacks because they have neglected social forces driving health of populations. Against this background, the second generation included, in their inquiries to better understand the evolution of health over time, social forces that interplay in shaping population health.26–28 This is referred to as the ‘SDoH’.29 The SDoH are a set of conditions in which people are born, grow up, work, live and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of their daily life.30 Studies by Braveman and Gottlieb26 27 provide sound discussions about the influences of social factors on health. In its initial format, the SDoH encompasses factors of multiple layers, including individual, community, national and global level factors. Indeed, besides structural determinants (eg, social system, socioeconomic position), previous studies showed that material circumstances, behaviours, biological and psychological factors derived from the structural factors also affect the health of populations.26 27 At the global level, there is an increasing debate on the effects of climate change on health hazards.31

This paper devotes a special attention to education and socioeconomic status (SES) proxied by Household Wealth Index (HWI), and their relationships with health insurance that is considered one’s behaviours. It is hypothesised that health insurance coverage is contingent on education and HWI. Amid the scarcity of resources and rampant poverty, people might not consider health insurance as a priority. Yet, out-of-pocket expenses are among the barriers that limit access to affordable healthcare, and therefore, exposing people to illnesses and deaths. The next two sections focus on the interlinkages between education, poverty, and the ownership of health insurance.

Education and health insurance

There are consistent findings across studies that education is positively and significantly associated with good health.32 33 According to these studies, linkages between education and health can be understood via (1) work and economic conditions; (2) socialpsychological resources and (3) health lifestyle. Regarding health insurance, it is posited that the effects of education are mediated through work and economic conditions. Indeed, more educated people are more likely to be working and therefore benefit from employer’s funded health insurance scheme. Empirically, studies conducted in SSA countries confirmed this assumption. For instance, a study in Burkina Faso showed that education level of head of household was positively and significantly associated with knowledge and enrolment in health insurance scheme.34 In contrast, a study in Ghana showed that education was not significantly associated with ownership of health insurance among women of reproductive ages even though the association went in the expected direction.35 In a multicountry study including Kenya, Tanzania, Ghana and Nigeria, Amu et al36 found that education had a significant and positive association with health insurance ownership for both females and males, even though the associations were stronger in Kenya compared with other countries. For instance, females and males with higher education were 15 times and 17 times more likely to own health insurance compared with their counterparts with no education, respectively. Similar findings were reported in Kenya with comparable datasets.37

SES and health insurance

There is abundant literature on the linkages between SES or position (hereafter, SES) and health. Previous research has established that SES is a fundamental cause of inequalities.31–33 On a theoretical point of view, and to be a ‘fundamental case of inequalities’, four criteria should be met. First, the cause influences multiple health problems. It is important to stress out that the cause is not limited to one disease or health problem. Second, the cause affects the disease through multiple risk factors. Third, the cause determines access to other resources to avoid risks or mitigate the consequences of the disease might it appears. Fourth, the effect of the cause on the disease should be reproduced over time via the replacement of intervening mechanisms.38 This theory emphasised the role of SES on health. As with health insurance, it is posited that SES affects ownership of health insurance through lifestyles and behaviours. People with higher SES are more likely to be employed and therefore they have more chances to own health insurance. Furthermore, people from higher SES are more likely to be educated and better understand the importance of health insurance. Indeed, resources of knowledge, power, money, prestige and beneficial social connections are among others, factors that explain why people from a specific social class might benefit from good health.38 39 In fact, previous research emphasised the role of health behaviours to better understand the effect of education on health.32

Empirically, findings showed that poverty was a leading cause of economic loss and it increased the vulnerability of the poor in Burkina Faso, Niger and Togo.40 Likewise, Barasa et al23 showed that SES was critical to further our understanding of inequalities of health insurance coverage in SSA. The study showed that health insurance coverage is inequitable in SSA, and it needs to be adequately addressed if SSA countries want to reach SDG 3 by 2030. A study conducted in Five Francophone Africa countries (Benin, Madagascar, Mali, Niger and Togo) using Demographic and Health Surveys (DHSs) found that health insurance coverage was very low, ranging from 1.1% in Benin to 3.3% in Togo.41 Not only the study found significant variations between urban and rural areas, it also reported that health insurance ownership was positively and significantly associated with HWI. Overall, the likelihood of health insurance ownership was higher among women living in better-off households compared with their counterparts in poor households.

Although findings suggested a positive and significant relationship between SES and health insurance ownership, one might be cautious to an over-generalisation. Indeed, a systematic review aimed at identifying barriers and facilitators to implementation, uptake and sustainability of community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes in low-income and middle-income countries reported mixed effects of SES on CBHI schemes.42 The pitfalls of this conclusion rely on variable measurement in the studies included in the systematic review.43–45 These studies used different settings and various approaches to conceptualise and operationalise SES, which might explain the mixed results observed in the papers included in the systematic review; therefore, the conclusion is debatable.

Methods

Data

The data used come from the 2013-2014 DHS conducted in the DRC (DRC-DHS 2013–2014). This is a nationally representative survey, using a two-stage sampling design.46 The first stage involved the selection of sample points or clusters from an updated master sampling frame constructed in accordance with DRC’s administrative division in 26 provinces or domains. These domains were further stratified into urban and rural areas. Urban areas neighbourhoods were sampled from cities and towns whereas for rural areas villages and chiefdoms were sampled. The clusters were selected using systematic sampling with probability proportional to size. Household listing was then conducted in all the selected clusters to provide a sampling frame for the second stage selection of households. The second stage of selection involved the systematic sampling of the households listed in each cluster, and households to be included in the survey were randomly selected from the list. The rationale for the second stage selection was to ensure adequate numbers of completed individual interviews to provide reliable estimates for key outcomes. Between November 2013 and February 2014, DHSs collect information on households, women (15—49 years) and men (15—59 years) of reproductive ages, including anthropometric measures, contraception and family planning among others. This paper reports on findings from women individual record file to construct the outcome and independent variables.

Variable measurement and operationalisation

Dependent variable

The outcome variable of this study was health insurance ownership. Women of reproductive ages were asked a single question: ‘Are you covered by any health insurance’? The dependent variable is coded 1 if the woman owned health insurance, 0 otherwise. Information about the type of insurance was also collected (public vs private). However, the low percentage of women owing a health insurance did not allow an in-depth investigation to distinguish between public vs private insurance.

Independent variables

The existing body of literature on health insurance and universal health coverage (UHC)42 47 48 guided the selection of independent variables included in the analyses, which were grouped into two broad categories: individual-level and household/community-level variables. Individual-level variables included current women’s age (in years), education (in years completed), marital status, religion, working status, index of media exposure, parity, antenatal care attendance and husband/partner’s education. The index of media exposure is a sum of three questions related to medias: watching television (TV); listening radio; and reading newspapers. Respondents were asked how often the watch TV, listen to radio, or read newspapers. Responses included 0 ‘not at all’; 1 ‘less than once a week’; 2 ‘at least once a week’. Responses to these three questions were summed up to get the index of media exposure. The higher the index of media exposure, the more the woman was exposed to media influences. At household/community level, the following variables were included: sex of the head of household; HWI; community literacy level; community SES (CSES); place of residence and province of residence. HWI was built using principal component analysis; details have been described elsewhere.46 In this paper, a new grouping was made to include poor households (40%), middle households (20%) and better-off households (40%). Community literacy measures the ability of women in the clusters to read effectively through the literacy from the variable v155 in the original dataset. Women in the cluster who can read were coded 1 and 0 otherwise. Thereafter, the average was computed, and three terciles were defined as ‘low’, ‘medium’ and ‘higher’. CSES was defined using HWI. All better-off households in the cluster were coded 1, and the mean was computed. Two quantiles were defined to get two categories of CSES: ‘low’ and ‘high’.

Analytical strategy

Descriptive statistics

The paper begins with bivariate analyses between the dependent variable and the set of putative covariates using the χ2 statistic to test significance associations. Given the nature of the dependent variable (ownership of health insurance: 1=yes; 0=no), only categorical variables were included at this stage. There is a debate in the statistical literature on which variables to include in the multivariable modelling based on the significance tests in bivariate analyses. In this paper, all independent variables reached statistical significance and there was no need to further discuss this issue.

Modelling strategy

For multivariate analyses, this paper uses multilevel modelling to investigate the effects of context and to quantify the influences of women’s education and poverty on the ownership of health insurance, controlling for variables at individual and household/community levels. The hierarchical nature of the data guided this choice. Since women from the same group are assumably alike because they share a common set of characteristics, this violates the standard assumption of independence of observations, which could produce biased variance estimates when failing to account for the clustering of observations. Furthermore, multilevel modelling allows to disentangle contextual from compositional effects by simultaneously modelling the effects of community-level and individual-level predictors, with woman as units of analysis.7 49 Two-level logistic regression models were performed as follows, in which i and j refer to individual-level and community-level variables, respectively:

| (1.a) |

| (1.b) |

The quantity is the probability that a sampled woman referenced (i, j) owns a health insurance; and are the kth individual-level covariate and lth community-level covariate, respectively; represents the interpret modelled to randomly vary across clusters; the estimates βk and δl represent the regression coefficients of individual- and community-level covariates respectively; and u0j is the random cluster residuals distributed as N(0, σu2).50 Analyses were performed using STATA SE V.15 for macOS, accounting for the complex survey design of DHS data to ensure that findings are generalised to the entire population of women of reproductive ages in the country. Besides the null model allowing for a theoretical justification of multilevel modelling, three models were estimated. The first model included individual-level covariates to obtain adjusted OR (AOR). The second model included household/community-level covariates. Finally, a full model including individual-level and household/community-level covariates was performed.

Model selection

Model selection is discussed in the statistical literature.51–54 First, statistical literature suggests that p values and tests based on them can be less efficient, especially with large samples.53 Second, the goodness-of-fit used to assess the performance of model to fit the data can be of limited utility in the presence of several candidate models.55 In this paper, Akaike information criterion (AIC) and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) are used to evaluate and choose the best models.52

Patient and public involvement

Patients/public were not involved in the design or implementation of this study.

Results

Descriptive results

Overall, 5% of women of reproductive ages in the DRC owns a health insurance (table 1). Most women owing a health insurance had an employer’s plan (76%), while a sizeable percentage (20%) of them subscribed in a mutual/community health insurance scheme. The paper was also interested in spatial variations of health insurance ownership. Findings indicated significant geographical variations of health insurance coverage in the DRC (figure 1). While 15.5% of women of reproductive ages own a health insurance in Kinshasa the Capital City, a marginal percentage of 1.2% of women are insured in Bandundu, Kasai Occidental and Maniema. Put differently, health insurance coverage is a ‘new reality’ in these provinces. From table 1, findings showed that women owing a health insurance lived in better-off households (10.4%), advantaged neighbourhoods (10.1%) and communities with high literacy level (10.6%); are urban residents (10.4%); and they are married to high-educated men (18.4%). Background characteristics of the sample and household/community-level factors are listed in online supplemental table A1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographics and health insurance among women of reproductive ages in the Democratic Republic of the Congo*

| Variables | Dependent variable: owns a health insurance | P value | ||||

| No | Yes | |||||

| Individual-level characteristics | N (weighted) | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Single | 4545 | 91.5 | (89.5,93.1) | 8.5 | (6.9,10.5) | <0.001 |

| Married or cohabiting | 12 448 | 95.9 | (94.9,96.7) | 4.1 | (3.3,5.1) | |

| Formerly married or cohabiting | 1834 | 97.8 | (96.7,98.5) | 2.2 | (1.5,3.3) | |

| Religion | ||||||

| Catholic | 5434 | 94.9 | (93.1,96.2) | 5.1 | (3.8,6.9) | NS |

| Protestant | 5243 | 96 | (94.5,97.1) | 4.0 | (2.9,5.5) | |

| Other Christians | 7377 | 94.2 | (93.0,95.2) | 5.8 | (4.8,7.0) | |

| Other religions | 773 | 96.2 | (91.7,98.3) | 3.8 | (1.7,8.3) | |

| Working status | ||||||

| No | 6979 | 93.5 | (91.8,94.9) | 6.5 | (5.1,8.2) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 11 848 | 95.9 | (95.0,96.6) | 4.1 | (3.4,5.0) | |

| Antenatal care (ANC) attendance | ||||||

| None | 1512 | 98.4 | (97.2,99.1) | 1.6 | (0.9,2.8) | <0.001 |

| 1–3 ANC visits | 12 230 | 94.6 | (93.6,95.5) | 5.4 | (4.5,6.4) | |

| 4+ ANC visits | 5085 | 95.0 | (93.3,96.2) | 5.0 | (3.8,6.7) | |

| Husband/partner’s education | ||||||

| No education | 6030 | 93.0 | (91.3,94.4) | 7.0 | (5.6,8.7) | <0.001 |

| Primary | 3375 | 99.1 | (98.5,99.5) | 0.9 | (0.5,1.5) | |

| Secondary | 8294 | 97.1 | (96.1,97.9) | 2.9 | (2.1,3.9) | |

| University or higher | 1128 | 81.6 | (78.1,84.6) | 18.4 | (15.4,21.9) | |

| Household-level and community-levelcharacteristics | ||||||

| Sex of household head | ||||||

| Male | 14 391 | 94.7 | (93.5,95.6) | 5.3 | (4.4,6.5) | <0.05 |

| Female | 4436 | 95.9 | (94.6,96.9) | 4.1 | (3.1,5.4) | |

| Household Wealth Index | ||||||

| Poor (40%) | 8106 | 99.3 | (98.9,99.6) | 0.7 | (0.4,1.1) | <0.001 |

| Middle (20%) | 3655 | 98.6 | (97.7,99.1) | 1.4 | (0.9,2.3) | |

| Rich (40%) | 7066 | 89.6 | (87.9,91.2) | 10.4 | (8.8,12.1) | |

| Community literacy level | ||||||

| Low (33%) | 6342 | 98.7 | (97.9,99.2) | 1.3 | (0.8,2.1) | <0.001 |

| Medium (33%) | 6214 | 98.5 | (97.3,99.2) | 1.5 | (0.8,2.7) | |

| High (34%) | 6271 | 89.4 | (87.4,91.2) | 10.6 | (8.8,12.6) | |

| Community socioeconomic status | ||||||

| Low (50%) | 11 868 | 98.7 | (97.5,99.4) | 1.3 | (0.6,2.5) | <0.001 |

| High (50%) | 6959 | 89.9 | (87.9,91.6) | 10.1 | (8.4,12.1) | |

| Place of residence | ||||||

| Rural | 12 157 | 98.2 | (97.0,98.9) | 1.8 | (1.1,3.0) | <0.001 |

| Urban | 6670 | 89.6 | (87.7,91.3) | 10.4 | (8.7,12.3) | |

| Province of residence | ||||||

| Kinshasa | 1804 | 84.5 | (81.2,87.3) | 15.5 | (12.7,18.8) | <0.001 |

| Bandundu | 2473 | 98.8 | (98.1,99.3) | 1.2 | (0.7,1.9) | |

| Kongo Central | 945 | 96.9 | (94.6,98.3) | 3.1 | (1.7,5.4) | |

| Equateur | 2696 | 97.8 | (95.5,98.9) | 2.2 | (1.1,4.5) | |

| Kasai Occidental | 1461 | 97.3 | (90.9,99.2) | 2.7 | (0.8,9.1) | |

| Kasai Oriental | 2073 | 98.8 | (96.4,99.6) | 1.2 | (0.4,3.6) | |

| Katanga | 2196 | 91.4 | (87.8,94.0) | 8.6 | (6.0,12.2) | |

| Maniema | 855 | 98.7 | (96.3,99.5) | 1.3 | (0.5,3.7) | |

| Nord Kivu | 1154 | 93.5 | (84.9,97.3) | 6.5 | (2.7,15.1) | |

| Orientale | 2137 | 97.0 | (94.6,98.4) | 3.0 | (1.6,5.4) | |

| Sud Kivu | 1033 | 92.4 | (85.5,96.1) | 7.6 | (3.9,14.5) | |

| Total | 18 827 | 95.0 | (93.9,95.8) | 5.0 | (4.2,6.1) | |

Source: DHS—2013–2014.

*Table 1 includes only categorical variables. Continuous variables (age, education, index of media exposure and number of children ever born) are not included here for practical reasons.

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey; NS, not significant.

Figure 1.

Percentage of women of reproductive ages owning health insurance in the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

bmjopen-2022-064834supp001.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)

Multivariate findings

As mentioned in the analytical strategy, three models were performed. Using AIC and BIC to choose the best model among a set of candidate models, findings (table 2) showed that the full model including both individual-level and household/community-level variables better fit the data. This conclusion was confirmed in table 2 with both AIC (AIC=4717.962) and BIC (BIC=4984.625). Therefore, this section focuses on findings of model 3 in table 3.

Table 2.

Model selection of health insurance coverage among women in Democratic Republic of the Congo

| Model | Akaike information criterion | Bayesian information criterion |

| 0 | 5171.725 | 5187.411 |

| 1 | 4841.876 | 4975.208 |

| 2 | 4909.624 | 5058.641 |

| 3 | 4717.962 | 4984.625 |

Source: DHS—2013–2014.

DHS, Demographic and Health Survey.

Table 3.

Multilevel logistic regression of individual and contextual factors associated with health insurance coverage among women in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

| Variables | Model 0 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 |

| Individual-level characteristics | ||||

| Women current age | 1.010 (0.994–1.025) | 1.008 (0.993–1.023) | ||

| Woman’s education (in completed years) | 1.128*** (1.095–1.162) | 1.098*** (1.065–1.132) | ||

| Marital status (Ref.: single) | ||||

| Married or cohabiting | 0.489*** (0.286–0.836) | 0.587* (0.343–1.006) | ||

| Formerly married or cohabiting | 0.300*** (0.164–0.549) | 0.364*** (0.198–0.666) | ||

| Religion (Ref.: catholic) | ||||

| Protestant | 0.859 (0.668–1.105) | 0.863 (0.672–1.109) | ||

| Other Christians | 0.861 (0.694–1.069) | 0.830* (0.668–1.032) | ||

| Other religions | 0.879 (0.500–1.544) | 0.877 (0.499–1.541) | ||

| Working status (Ref.: no) | 0.990 (0.824–1.188) | 1.054 (0.877–1.265) | ||

| Index of media exposure | 1.810*** (1.515–2.163) | 1.488*** (1.245–1.778) | ||

| Children ever born | 1.062** (1.010–1.117) | 1.054** (1.003–1.108) | ||

| Antenatal care attendance (Ref.: no ANC) | ||||

| 1–3 ANC visits | 1.167 (0.708–1.925) | 1.035 (0.624–1.718) | ||

| 4+ ANC visits | 1.071 (0.641–1.788) | 0.926 (0.551–1.555) | ||

| Husband or partner’s education (Ref.: no education) | ||||

| Primary | 0.668 (0.372–1.198) | 0.705 (0.393–1.264) | ||

| Secondary | 1.033 (0.630–1.693) | 0.959 (0.585–1.573) | ||

| University or higher | 3.072*** (1.816–5.197) | 2.564*** (1.516–4.335) | ||

| Household-level and community-level characteristics | ||||

| Household head is female (Ref.: male) | 0.777** (0.636–0.948) | 0.829* (0.668–1.029) | ||

| Household Wealth Index (Ref.: 40% poor) | ||||

| Middle (20%) | 1.691** (1.095–2.612) | 1.375 (0.887–2.130) | ||

| Rich (40%) | 3.949*** (2.593–6.015) | 2.501*** (1.620–3.860) | ||

| Community literacy level (Ref.: low 33%) | ||||

| Medium (33%) | 0.822 (0.467–1.446) | 0.649 (0.370–1.139) | ||

| High (33%) | 2.209** (1.087–4.488) | 1.173 (0.573–2.403) | ||

| Community socioeconomic status—high (Ref.: 50% low) |

3.546*** (1.912–6.577) | 3.232*** (1.746–5.983) | ||

| Urban residence (Ref.: rural) | 0.942 (0.623–1.425) | 0.866 (0.570–1.314) | ||

| Province of residence (Ref.: Kinshasa) | ||||

| Bandundu | 0.363*** (0.168–0.784) | 0.408** (0.190–0.877) | ||

| Kongo Central | 0.202*** (0.076–0.541) | 0.308** (0.116–0.817) | ||

| Equateur | 0.651 (0.295–1.435) | 0.790 (0.361–1.729) | ||

| Kasai occidental | 0.259*** (0.097–0.687) | 0.350** (0.133–0.919) | ||

| Kasai oriental | 0.096*** (0.038–0.241) | 0.135*** (0.054–0.336) | ||

| Katanga | 0.870 (0.423–1.791) | 1.156 (0.564–2.371) | ||

| Maniema | 0.174*** (0.053–0.568) | 0.225** (0.069–0.726) | ||

| Nord Kivu | 0.941 (0.406–2.181) | 1.162 (0.502–2.689) | ||

| Orientale | 0.684 (0.318–1.473) | 0.874 (0.408–1.874) | ||

| Sud Kivu | 0.864 (0.346–2.159) | 1.167 (0.467–2.916) | ||

| Intraclass correlation | 0.613 (0.534–0.679) | 0.429 (0.359–0.504) | 0.352 (0.268–0.425) | 0.341 (0.275–0.415) |

| Observations | 18 827 | 18 827 | 18 827 | 18 827 |

| No of groups | 536 | 536 | 536 | 536 |

Source: DHS—2013–2014.

*p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001.

AOR, adjusted OR; DHS, Demographic and Health Survey.

Before moving to estimates reported in model 3, let’s investigate model 0 to see if the multilevel modelling is relevant for this study. The intraclass correlation was 0.613 (61.3%). This is quite large, and it justifies the utilisation of multilevel modelling. The interpretation of findings in model 3 starts with the association between health insurance ownership and the two key independent variables: women’s education (in completed years) and HWI. First, findings indicated that each additional year of women education increased by 10% the chance of owing a health insurance (AOR 1.098; 95% CI 1.065 to 1.132). Second, living in better-off households increased by 150% the chance of owing a health insurance (AOR 2.501; 95% CI 1.620 to 3.860) compared with women living in poor households (referred to as 40% bottom HWI). This confirmed the assumptions that HWI and women’s education are key covariates to better understand health insurance ownership in the DRC.

Model 3 in table 3 also reported interesting results both at individual and household/community level. At individual level, model 3 indicated that husband/partner’s education is of chief importance. Specifically, husbands/partners with university or higher are pivotal to explain women’s ownership of health insurance. Being married to husband/partner with a university degree or higher increased by 156% the chance of owing a health insurance (AOR 2.564; 95% CI 1.516 to 4.335). The index of media exposure is also significantly associated with the ownership of health insurance. An increase of 1 unit of the index of media exposure increased by almost 50% the chance of owing a health insurance among women of reproductive ages (AOR 1.488; 95% CI 1.245 to 1.778). In contrast, marital status showed counter-intuitive results: ever married women were less likely to be covered by health insurance compared with never married women.

At household/community level, CSES was positively and significantly associated with the ownership of health insurance. Indeed, living in advantaged neighbourhoods increased by 223% the chance of owing a health insurance (AOR 3.232; 95% CI 1.746 to 5.983).

Discussion

From a policy perspective, most countries in SSA should align with SDGs to ensure that all people have access to affordable healthcare. However, less efforts have been done to improve the progress of SDG 3 aimed at improving maternal and child health at national and subnational levels. This paper contributes to the existing literature in examining subnational disparities of health insurance coverage using SDoH as a conceptual framework with an emphasis on education and SES to better understand these disparities in the DRC. Main findings of the paper are discussed below.

First, health insurance coverage among women of reproductive ages in the DRC was quite low at national level as reported in previous studies with a marginal percentage (5%) having a health insurance.7 Similar studies reported extremely low percentage (2.8%) of health insurance ownership among women of reproductive ages in the DRC using same datasets.56 These findings have policy and programmatic implications in the DRC given the low coverage in health insurance, and they might explain the poor quality of maternal and child health indicators in the DRC. Indeed, previous studies reported that maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in the DRC was very high, and it was estimated at 473 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births.57 This is alarming because it also means that the country won’t reach the SDG 3.1 aimed at reducing, by 2030, the MMR at 70 maternal deaths per 100 000 live births. Yet, obstetrical complications such as bleeding, eclampsia, sepsis and unsafe abortions, accounting for nearly 80% of the MMR cases require urgent and appropriate care through health insurance coverage as a pathway to access affordable healthcare. Second, there were important geographical variations regarding health insurance coverage ranging from 1.2% in Bandundu and Kasai Oriental to 15.5% in Kinshasa the Capital City. With these figures, the DRC is lagging very behind regarding the SDG 3.

Turning to the main hypothesis of the study, regarding the associations between education, SES, and health insurance coverage in the DRC, findings can be summarised as follows. An additional year of completed education increased by 10% the likelihood of owning health insurance among women of reproductive ages. This finding is consistent with previous studies.18 22 23 42 However, plausible explanations from previous studies are insufficient in the context of the DRC. Indeed, previous research stated that educated women may be exposed to much more health information, which increases their likelihood to subscribe to health insurance coverage. In the context of higher unemployment rates, education per se might not suffice to explain why educated women are more likely to own health insurance coverage. This study suggested another explanation given that health insurance coverage was higher in Kinshasa the Capital City compared with other provinces. Educated women were more likely to work, and therefore, increasing their chances to own health insurance coverage. In fact, preliminary findings showed that 62% of surveyed women were working at the time of the survey. Surprisingly, the likelihood to own health insurance was higher among not-working women compared with their working counterparts. DHSs do not capture the sector (public vs private) where women work. The high unemployment rates in the country and the widespread of informal sector can explain this finding. If most women work in informal sector, it is likely that they will not have health insurance coverage. Therefore, more research is needed to unpack this intriguing finding, and to suggest other paths of influence. The fact that less educated women have lesser likelihood to own health insurance also means that policymakers and stakeholders working to improve health conditions in the DRC need to pay more attention to women’s education as a precondition to increase access to health insurance. This finding also held at community level because women of reproductive ages living in communities with high literacy level were more likely to own health insurance.

With regard to SES, findings indicated that women of reproductive ages living in better-off households and advantaged neighbourhoods had higher chances to own health insurance compared with their counterparts in poor households and disadvantaged neighbourhoods. This finding was in lines with previous research.23 In the DRC, there are fewer initiatives of spreading health insurance at individual and community levels. Yet, this is crucial for the country to achieve by 2030 the SDG 3. Previous studies posited that unequal exposure to media might explain such differences in health insurance coverage.23 Overall, there are no clear policies in the DRC aimed at reducing the inequalities to media exposure, doubled with higher unemployment rates in the country which together limit the ability to seek correct health information among women of reproductive ages.

The study has a few strengths and limitations. Using a nationally representative sample to analyse the disparities in health insurance at provincial level is an important strength, thereby providing robust estimates of observed associations between poverty, education and ownership of health insurance. The use of multilevel modelling allowed to identify the potential factors of influence that policymakers can target to improve access to health insurance, to increase UHC, and ultimately to reach the SDG 3 in the DRC and other SSA countries. Finally, looking into health insurance at provincial level reinforce the importance of context-specific interventions. Indeed, findings showed significant variations across provinces and that to be accounted for to reduce health inequalities. The cross-sectional nature of data used in the paper is a limitation which does not allow determining causality between our main independent variables (HWI and education) and health insurance ownership. Therefore, findings in this paper should be interpreted in terms of associations and no definite conclusions can be drawn regarding the potential influences of poverty and education on health insurance coverage. Further research is needed to better understand these potential influences.

Conclusion

This cross-sectional study examined the associations between two key SDoH (poverty and education) and health insurance coverage in the DRC. Findings showed that UHC is alarmingly low in the DRC like in other SSA countries. The study also found significant disparities across provinces, and between poor and rich. Programmatically, that means the RDC will not reach SDG 3 aimed at improving maternal and child health. Yet UHC is pivotal to achieve SDG 3 in SSA countries. To improve maternal and child health in the country, policy makers and stakeholders should tackle inequalities between poor and rich and devise interventions to equip poor to better understand the importance of health insurance coverage given the existing rampant and secular poverty. Unlike countries such as Ghana with a sustainable national health insurance scheme,3 19 58 59 the DRC has not yet developed and implemented a strong health insurance scheme to help people, especially poor, to freely access healthcare or at affordable cost. The fact that out-of-pocket expenditures are the major mode of payments for healthcare in the DRC constitutes a serious threat to UHC and the achievement of SDG 3. It was shown that out-of-pocket expenses is a strong barrier to access good healthcare services with the immediate consequence of maintaining or increasing MMR in the country, therefore putting in jeopardy mothers and their children.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their profound gratitude to The DHS Program, USA, for providing free access to the data. They also wish to acknowledge institutions of the Democratic Republic of the Congo that played critical roles in the data collection process.

Footnotes

Contributors: ZTD, P-DNK and RMN conceived and designed the study. ZTD and RMN conducted the data analysis, interpreted the results, and drafted the manuscript. P-DNK contributed to study design, data analysis, interpretation, policy implications and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors took responsibility of any issues that might arise from the publication of this manuscript. ZTD is the guarantor and accepts full responsibility of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data can be obtained from the DHS program (https://dhsprogram.com/data/).

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

The DHS obtained ethical clearance from the Government recognised Ethical Review Committees/Institutional Review Boards of the Democratic Republic of the Congo as well as the Institutional Review Board of ICF International (USA), before the surveys were conducted. Written informed consent was obtained from the women before participation. The authors of this paper sought and obtained permission from the DHS programme to use the data. The data were completely anonymised, and therefore, the authors did not seek further ethical clearance before their use.

References

- 1.Atnafu DD, Tilahun H, Alemu YM. Community-Based health insurance and healthcare service utilisation, north-west, Ethiopia: a comparative, cross-sectional study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019613. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nyamugira AB, Richter A, Furaha G, et al. Towards the achievement of universal health coverage in the Democratic Republic of Congo: does the country walk its talk? BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:860. 10.1186/s12913-022-08228-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kipo-Sunyehzi DD, Ayanore MA, Dzidzonu DK. Ghana’s Journey towards Universal Health Coverage: The Role of the National Health Insurance Scheme. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ 2020;10:94–109. 10.3390/ejihpe10010009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nyonator F, Kutzin J. Health for some? the effects of user fees in the Volta region of Ghana. Health Policy Plan 1999;14:329–41. 10.1093/heapol/14.4.329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ethiopian Health Insurance Agency . Evaluation of community-based health insurance pilot schemes in Ethiopia: final report. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: Ethiopian Health Insurance, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mwaura JW, Pongpanich S. Access to health care: the role of a community based health insurance in Kenya. Pan Afr Med J 2012;12:35. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amu H, Seidu A-A, Agbaglo E, et al. Mixed effects analysis of factors associated with health insurance coverage among women in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 2021;16:e0248411. 10.1371/journal.pone.0248411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.United Nations . Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development U. N. Popul. fund, 2015. Available: https://www.unfpa.org/resources/transforming-our-world-2030-agenda-sustainable-development [Accessed 05 Mar 2022].

- 9.Kumar S. 036: does health insurance promote healthcare access and provide financial protection: empirical evidences from India does health insurance promote healthcare access and provide financial protection: empirical evidences from India. BMJ Open 2015. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-forum2015abstracts.36 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sriram S, Khan MM. Effect of health insurance program for the poor on out-of-pocket inpatient care cost in India: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res 2020;20:839. 10.1186/s12913-020-05692-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ikegami N, Yoo B-K, Hashimoto H, et al. Japanese universal health coverage: evolution, achievements, and challenges. Lancet 2011;378:1106–15. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60828-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reich MR, Ikegami N, Shibuya K, et al. 50 years of pursuing a healthy society in Japan. Lancet 2011;378:1051–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60274-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kwon S. Thirty years of national health insurance in South Korea: lessons for achieving universal health care coverage. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:63–71. 10.1093/heapol/czn037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reich MR, Harris J, Ikegami N, et al. Moving towards universal health coverage: lessons from 11 country studies. Lancet 2016;387:811–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60002-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmed A, Cleeve E. Tracking the millennium development goals in sub‐Saharan Africa. Int J Soc Econ 2004;31:12–29. 10.1108/03068290410515394 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Easterly W. How the millennium development goals are unfair to Africa. World Dev 2009;37:26–35. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2008.02.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juju D, Baffoe G, Dam Lam R. Sustainability Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa in the Context of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). In: Gasparatos A, Ahmed A, Naidoo M, eds. Sustainability Challenges in Sub-Saharan Africa I: Continental Perspectives and Insights from Western and Central Africa. Singapore: Springer, 2020: 3–50. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aku KM, Mensah KA, Twum P, et al. Factors influencing Nonrenewal of health insurance membership in Ejisu-Juaben Municipality of Ashanti region, Ghana. Adv Public Health 2021;2021:1–8. 10.1155/2021/5575822 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Carapinha JL, Ross-Degnan D, Desta AT, et al. Health insurance systems in five sub-Saharan African countries: medicine benefits and data for decision making. Health Policy 2011;99:193–202. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2010.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cashin C, Dossou J-P. Can National health insurance pave the way to universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa? Health Syst Reform 2021;7:e2006122. 10.1080/23288604.2021.2006122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chemouni B. The political path to universal health coverage: power, ideas and community-based health insurance in Rwanda. World Dev 2018;106:87–98. 10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.01.023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ifeagwu SC, Yang JC, Parkes-Ratanshi R, et al. Health financing for universal health coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Glob Health Res Policy 2021;6:8. 10.1186/s41256-021-00190-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barasa E, Kazungu J, Nguhiu P, et al. Examining the level and inequality in health insurance coverage in 36 sub-Saharan African countries. BMJ Glob Health 2021;6:e004712. 10.1136/bmjgh-2020-004712 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laokri S, Soelaeman R, Hotchkiss DR. Assessing out-of-pocket expenditures for primary health care: how responsive is the Democratic Republic of Congo health system to providing financial risk protection? BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:451. 10.1186/s12913-018-3211-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Criel B, Waelkens M-P, Kwilu Nappa F, et al. Can mutual health organisations influence the quality and the affordability of healthcare provision? the case of the Democratic Republic of Congo. PLoS One 2020;15:e0231660. 10.1371/journal.pone.0231660 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it's time to consider the causes of the causes. Public Health Rep 2014;129 Suppl 2:19–31. 10.1177/00333549141291S206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annu Rev Public Health 2011;32:381–98. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031210-101218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marmot M, Allen JJ. Social determinants of health equity. Am J Public Health 2014;104 Suppl 4:S517–9. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.World Health Organization (WHO) . A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Geneva, Switzerland, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Misawa J, Ichikawa R, Shibuya A, et al. Social determinants affecting the use of complementary and alternative medicine in Japan: an analysis using the conceptual framework of social determinants of health. PLoS One 2018;13:e0200578. 10.1371/journal.pone.0200578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Einheuser MD, Nejadhashemi AP, Wang L, et al. Linking biological integrity and watershed models to assess the impacts of historical land use and climate changes on stream health. Environ Manage 2013;51:1147–63. 10.1007/s00267-013-0043-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brunello G, Fort M, Schneeweis N, et al. The causal effect of education on health: what is the role of health behaviors? Health Econ 2016;25:314–36. 10.1002/hec.3141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ross CE, Wu C-ling, Wu C. The links between education and health. Am Sociol Rev 1995;60:719–45. 10.2307/2096319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cofie P, De Allegri M, Kouyaté B, et al. Effects of information, education, and communication campaign on a community-based health insurance scheme in Burkina Faso. Glob Health Action 2013;6:20791. 10.3402/gha.v6i0.20791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amu H, Dickson KS. Health insurance subscription among women in reproductive age in Ghana: do socio-demographics matter? Health Econ Rev 2016;6:24. 10.1186/s13561-016-0102-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Amu H, Dickson KS, Kumi-Kyereme A, et al. Understanding variations in health insurance coverage in Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, and Tanzania: evidence from demographic and health surveys. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201833. 10.1371/journal.pone.0201833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kimani JK, Ettarh R, Warren C, et al. Determinants of health insurance ownership among women in Kenya: evidence from the 2008-09 Kenya demographic and health survey. Int J Equity Health 2014;13:27. 10.1186/1475-9276-13-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Phelan JC, Link BG, Tehranifar P. Social conditions as fundamental causes of health inequalities: theory, evidence, and policy implications. J Health Soc Behav 2010;51 Suppl:S28–40. 10.1177/0022146510383498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Link BG, Phelan JC. Understanding sociodemographic differences in health--the role of fundamental social causes. Am J Public Health 1996;86:471–3. 10.2105/AJPH.86.4.471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Atake E-H. Health shocks in sub-Saharan Africa: are the poor and uninsured households more vulnerable? Health Econ Rev 2018;8:26. 10.1186/s13561-018-0210-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang Y, Wang X, Ji L. Sociodemographic inequalities in health insurance ownership among women in selected Francophone countries in sub-Saharan Africa. BioMed Res Int 2021;2021:e6516202. 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-064834 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fadlallah R, El-Jardali F, Hemadi N, et al. Barriers and facilitators to implementation, uptake and sustainability of community-based health insurance schemes in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Equity Health 2018;17:13. 10.1186/s12939-018-0721-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gnawali DP, Pokhrel S, Sié A, et al. The effect of community-based health insurance on the utilization of modern health care services: evidence from Burkina Faso. Health Policy 2009;90:214–22. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.09.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mladovsky P. Why do people drop out of community-based health insurance? findings from an exploratory household survey in Senegal. Soc Sci Med 2014;107:78–88. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parmar D, Souares A, de Allegri M, et al. Adverse selection in a community-based health insurance scheme in rural Africa: implications for introducing targeted subsidies. BMC Health Serv Res 2012;12:181. 10.1186/1472-6963-12-181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ministère du Plan et Suivi de la Mise en oeuvre de la Révolution de la Modernité (MPSMRM) . Ministère de la Santé Publique (MSP), ICF international. Enquête Démographique et de Santé en République Démocratique Du Congo 2013-2014. Rockville, Maryland, USA: MPSMRM, MSP et ICF International, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Degroote S, Ridde V, De Allegri M. Health insurance in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of the methods used to evaluate its impact. Appl Health Econ Health Policy 2020;18:825–40. 10.1007/s40258-019-00499-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Miti JJ, Perkio M, Metteri A, et al. Factors associated with willingness to pay for health insurance and pension scheme among informal economy workers in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Int J Soc Econ 2020;48:17–37. 10.1108/IJSE-03-2020-0165 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sommet N, Morselli D. Keep calm and learn multilevel logistic modeling: a simplified three-step procedure using Stata, R, mPLUS, and SPSS. Int Rev Soc Psychol 2017;30:203–18. 10.5334/irsp.90 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Snijders T, Bosker R. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Applied Multilevel Analysis. In: Publications S, ed. 2 nd, 2012.

- 51.Burnham KP, Anderson DR. Multimodel inference: understanding AIc and Bic in model selection. Sociol Methods Res 2004;33:261–304. 10.1177/0049124104268644 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.AIC KJ. And Bic: comparisons of assumptions and performance. Sociol Methods Res 2004;33:188–229. 10.1177/0049124103262065 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Raftery AE. Bayesian model selection in social research. Sociol Methodol 1995;25:111–63. 10.2307/271063 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Susko E, Roger AJ. On the use of information criteria for model selection in phylogenetics. Mol Biol Evol 2020;37:549–62. 10.1093/molbev/msz228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bierens HJ. Information criteria and model selection, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shao L, Wang Y, Wang X, et al. Factors associated with health insurance ownership among women of reproductive age: a multicountry study in sub-Saharan Africa. PLoS One 2022;17:e0264377. 10.1371/journal.pone.0264377 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo F, Qi X, Xiong H, et al. Trends of maternal health service coverage in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a pooled cross-sectional study of MICs 2010 to 2018. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2021;21:748. 10.1186/s12884-021-04220-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Alhassan RK, Nketiah-Amponsah E, Arhinful DK. A review of the National health insurance scheme in Ghana: what are the sustainability threats and prospects? PLoS One 2016;11:e0165151. 10.1371/journal.pone.0165151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Blanchet NJ, Fink G, Osei-Akoto I. The effect of Ghana's National health insurance scheme on health care utilisation. Ghana Med J 2012;46:76–84. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2022-064834supp001.pdf (38.7KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Data can be obtained from the DHS program (https://dhsprogram.com/data/).