Abstract

Objective

The aim of this work is to explore patient’ unmet needs of rare and complex rheumatic tissue diseases (rCTDs) patients during pregnancy and its planning by means of the narrative-based medicine (NBM) approach.

Methods

A panel of nine rCTDs patients’ representatives was identified to codesign a survey aimed at collecting the stories of rCTD patients who had one or more pregnancies/miscarriages. The results of the survey and the stories collected were analysed and discussed with a panel of patients’ representatives to identify unmet needs, challenges and possible strategies to improve the care of rCTD patients.

Results

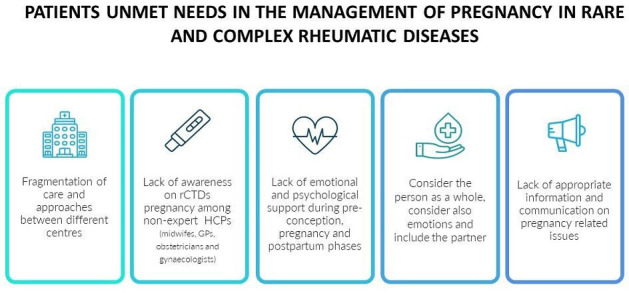

129 replies were collected, and 112 stories were analysed. Several unmet needs in the management of pregnancy in rCTDs were identified, such as fragmentation of care among different centres, lack of education and awareness on rCTD pregnancies among midwifes, obstetricians and gynaecologists. The lack of receiving appropriate information and education on rCTDs pregnancy was also highlighted by patients and their families. The need for a holistic approach and the availability specialised pregnancy clinics with a multidisciplinary organisation as well as the provision of psychological support during all the phases around pregnancy was considered also a priority.

Conclusion

The adoption of the NBM approach enabled a direct identification of unmet needs, and a list of possible actions was elaborated to improve the care of rCTD patients and their families in future initiatives.

Keywords: Autoimmune Diseases, Health services research, Patient Care Team

What is already known on this topic

Rare and complex rheumatic tissue diseases (rCTDs) are systemic conditions that can occur in women of fertile age and pregnancy and family planning can be considered a complex phase in the life of these patients, but no studies have explored the needs and the journey of rCTD patient during pregnancy and its planning.

What this study adds

Several unmet needs in the management of pregnancy in rCTDs were identified, such as fragmentation of care among different centres, lack of education and awareness on rCTD pregnancies among midwifes, obstetricians and gynaecologists. The lack of receiving appropriate information and education on rCTDs pregnancy was also highlighted by patients and their families. The need for a holistic approach and the availability specialised pregnancy clinics with a multidisciplinary organisation as well as the provision of psychological support during all the phases around pregnancy was considered also a priority.

How this study might affect research, practice or policy

The unmet needs and the possible solutions identified in this work can help to plan future initiatives and strategies aimed at improving the experience and the journey of rCTDs during pregnancy and family planning.

Background

Rare and complex rheumatic tissue diseases (rCTDs) are systemic conditions that can occur in women of fertile age, and for this reason, pregnancy and family planning can be considered a complex phase in the life of a patient living with rCTDs. rCTDs include systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) and antiphospholipid antibody (aPL) carriers, small-vessel vasculitides (SVV) and other similar conditions.

Thanks to the recent progresses made in the management of rCTDs, pregnancy is no longer considered critical in women living with rCTDs and, in fact, with the support of careful pregnancy planning care, including the evaluation of possible risk factors, successful pregnancies are definitely possible.1–7 Risk factors for adverse pregnancy outcomes include active disease at conception and severe organ involvement, and it is, therefore, necessary to monitor disease activity before and during pregnancy and achieve disease control with treatments that can be continued throughout pregnancy and lactation.8 rCTDs can have different courses during pregnancy, but adverse pregnancy outcome is increased with respect to the general population, especially in patients with SLE and/or APS and SS.8

Pregnancy can have a significant impact on the life of patients and of their families, however, in the past, only a few works have explored the perspectives of patients living with rheumatic diseases experiencing pregnancies.9–11 Understanding how rheumatic patients and families perceive their journey through pregnancy can provide useful insights to improve the care provided and highlight what is important to patients and what still needs to be done to improve their life during such a special time of their life.

So far, no studies have adopted the narrative-based medicine approach (NBM)12 to identify needs, challenges and the journey experienced by rheumatic patients during the different phases of pregnancy. NBM is an approach that allows the collection of information on the patient’s experience of illness and aims at integrating evidence-based medicine with the stories of illness to enrich clinical information with the experience of the patient and with practical knowledge that can be taken into account in clinical practice. NBM can also help to achieve humanisation of care and personalised medicine. The use of NBM was recently included in the RarERN Path,13 a methodology specifically designed to develop organisational patients’ pathway reference model within rare and complex diseases, which collects and elaborates patients’ stories in order to integrate patients’ needs in the framework of the different phases of care. Based on the previous positive experiences gathered by different members of the European Reference Network on connective tissue and musculoskeletal diseases—ERN ReCONNET14 15—, the international study group about Reproduction, Pregnancy and Rheumatic diseases (RheumaPreg)16 agreed to follow some principles of RarERN Path to collect the stories of patients living with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy. Thus, the aim of this work is to present the results of the adoption of the NBM approach foreseen in RarERN Path to explore the experiences, perspectives and unmet needs of patients living with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy.

Methods

This study included a blended methodology that incorporated different approaches. As illustrated in figure 1, The first step of the work was the identification of a panel of patients’ representatives involved in rheumatic diseases, the panel was formed by nine patients’ representatives from six different countries (France, Italy, Romania, Spain, Sweden and United Kingdom) that represented APS, relapsing polychondritis (RP), Sjögren’s syndrome (SS), SLE and systemic sclerosis (SSc). The panel of patients’ representatives was coordinated by an expert in NBM and in patient engagement who gathered the panel in virtual meetings and managed the whole project. The second step was the codesign of a dedicated survey aimed at collecting the stories of rCTDs patients who had one or more pregnancies/miscarriages. The diseases included were APS and aPL carriers, Behçet’s disease (BD), idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, IgG4-related diseases (IgG4), large vessel vasculitides, mixed connective tissue disease (MCTD), RP, SVV, SLE, SSc, SS, undifferentiated connective tissue disease (UCTD).

Figure 1.

Workflow of the study.

The survey was anonymous and was developed in English on the online platform ‘EU Survey’.17 It was composed of 14 questions (10 single choices, 2 multiple-choices and two open-ended questions) and one free space in which the patients could write their stories. The survey was launched across social media (Facebook and Twitter) as well as across different rCTD patients’ associations, also with the support of the panel of patients’ representatives. Since the survey was completely anonymous and no personal information was collected, an approval of the Institutional Board Review was not needed and patients consented to participate in the study by replying to the survey. The survey was open from 5 July to 8 August 2021.

After closing the data collection by means of the survey, the next step was performing the analysis of the stories by two experts in NBM, together with the patients’ panel.

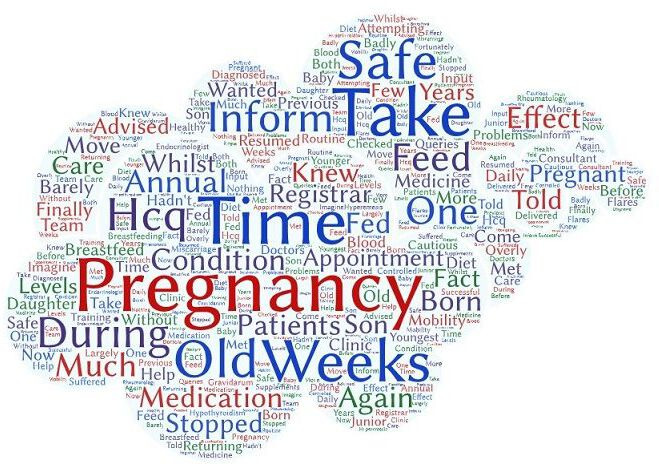

The stories collected were analysed by means of the online software Wordart, which identified the most frequent words used in the stories, and the result of this analysis was represented in dedicated word clouds, one describing the most frequently used words in all the stories and seven word clouds that included the most frequent words used based on the diseases selected in the survey by the respondents.

An additional analysis was performed to identify the transversal topics that were included in most stories as well as the main challenges, good practices and most representative experiences lived by patients during the different phases: prepregnancy, during pregnancy, after pregnancy and miscarriages. An additional analysis was also performed to identify the emotions reported in the stories.

The results of a preliminary analysis performed were shared with the patients’ panel and, afterwards, the panel was convened virtually to discuss the results collected and agree on the most important messages that were highlighted in the stories, also exploring the experience gathered by the patients’ representatives in their advocacy work within their patients’ organisations.

Results

After the launch of the survey, 129 replies were collected, and 112 stories were analysed since 17 stories were not eligible for the analysis as they were not in English (n. 8 stories were in Spanish n. 3 stories in Italian n. 1 story in French and n. 1 story in Slovak) or as they did not include any text (n. 4 stories).

The replies were collected from patients with APS/aPL carriers (n=50, 46 analysed), SLE (n=50, 44 analysed), SS (n=11, 6 analysed), MCTD (n=8, 7 analysed), SSc (n=5, 4 analysed), UCTD (n=2), BD (n=2) and RP (n=1).

Most patients were from the United Kingdom (52.71%), had an age between 31 and 40 years (42.64%), were married or in a relationship (86.05%) and had a Bachelor’s degree (43.41%); 93.80% of them lived with a family member(s) and 6.20% with a caregiver. Characteristics of the respondents are detailed in table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents

| Age | N. | % |

| 21–30 | 13 | 10.08 |

| 31–40 | 55 | 42.64 |

| 41–50 | 42 | 32.56 |

| 51–60 | 10 | 7.75 |

| 61–70 | 5 | 3.88 |

| 71–80 | 4 | 3.10 |

| Countries | ||

| Australia | 3 | 2.33 |

| Belgium | 4 | 3.10 |

| Denmark | 9 | 6.98 |

| Finland | 3 | 2.33 |

| Italy | 4 | 3.10 |

| Lithuania | 8 | 6.20 |

| Portugal | 3 | 2.33 |

| Spain | 12 | 9.30 |

| UK | 68 | 52.71 |

| USA | 3 | 2.33 |

| Other European contries | 8 | 6.20 |

| Other non-European countries | 4 | 3.10 |

| Level of education | ||

| Below high school diploma | 6 | 4.65 |

| High school diploma | 27 | 20.93 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 56 | 43.41 |

| Masters’ degree or higher | 40 | 31.01 |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed/self-employed | 94 | 72.87 |

| Other | 8 | 6.20 |

| Retired | 5 | 3.88 |

| Student | 1 | 0.78 |

| Unable to work due to my disease | 12 | 9.30 |

| Unemployed | 9 | 6.98 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married or in a relationship | 111 | 86.05 |

| Separated or divorced | 11 | 8.53 |

| Single | 6 | 4.65 |

| Widowed | 1 | 0.78 |

| Do you live with a caregiver? | ||

| Yes | 8 | 6.2 |

| No | 121 | 93.8 |

| Do you live with | ||

| Family member (partner, member of the family) | 122 | 94.57 |

| Other (friend, colleague, etc) | 0 | 0 |

| Alone | 8 | 6.2 |

At the time of starting/planning pregnancy, 50.39% of patients were already diagnosed with rCTDs, and 10.85% were diagnosed during pregnancy. Preconceptional counselling was received by 27.91% of patients, 48.06% had regularly seen their specialist (rheumatologist or immunologist) during pregnancy and 42.64% were followed by a multidisciplinary team; the outcome of pregnancy was on term birth in 49.61% of cases, and 35.66% of interviewed were very satisfied with the care provided during pregnancy (table 2).

Table 2.

Information about pregnancy

| At the time of starting/planning your pregnancy, where you… | N. | % |

| Already diagnosed with this disease | 65 | 50.39 |

| I have been diagnosed during my pregnancy | 14 | 10.85 |

| Not yet diagnosed with this disease | 50 | 38.76 |

| Before your pregnancy, did you receive a pre-conceptional counselling (any counselling before a planned pregnancy)? | ||

| I don't know | 4 | 3.10 |

| No | 89 | 68.99 |

| Yes | 36 | 27.91 |

| During your pregnancy, did you see your specialist (rheumatologist, immunologist, etc) regularly? | ||

| I don't know | 3 | 2.33 |

| No | 64 | 49.61 |

| Yes | 62 | 48.06 |

| During your pregnancy, were you followed by a multi-disciplinary team (different specialists)? | ||

| I don't know | 4 | 3.10 |

| No | 70 | 54.26 |

| Yes | 55 | 42.64 |

| How did your pregnancy end? What was the outcome of your pregnancy? | ||

| I prefer not to answer | 1 | 0.78 |

| Miscarriage | 20 | 15.50 |

| On term birth | 64 | 49.61 |

| Preterm birth | 40 | 31.01 |

| Other | 4 | 3.10 |

| How would you rate the care you were provided during your pregnancy? | ||

| Very Satisfied | 46 | 35.66 |

| Satisfied | 33 | 25.58 |

| Neutral | 25 | 19.38 |

| Dissatisfied | 15 | 11.63 |

| Very dissatisfied | 10 | 7.75 |

Analysis of the stories

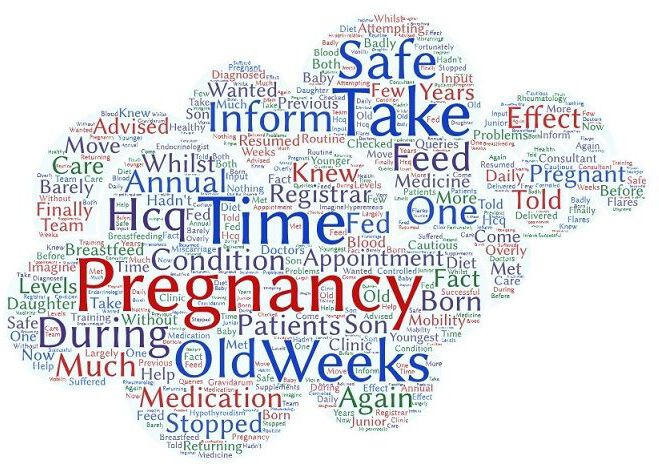

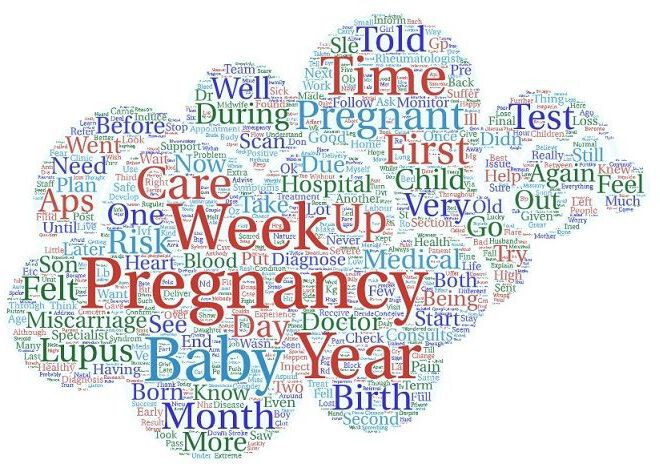

The frequency of the words used in the patient’s stories is reported in the wordcloud in figure 2, where the biggest words represent the words that were more frequently used in the stories. Similarly, the disease-specific most frequent words are reported in table 3 and represented in figures 3–9. The analysis related to the frequency of words was performed by means of the WordArt tool.

Figure 2.

Most frequent words used in the antiphospholipid syndrome and aPL carriers patients’ stories. aPL, antiphospholipid antibody.

Table 3.

Most frequent words used in the patient’s stories

| Diagnosis selected by the respondents | Frequency of the word | Total number of stories collected |

| Antiphospholipid syndrome and anti-phospholipid antibody carriers | Pregnancy (n. 113) | n.50 |

| Week (n. 93) | ||

| Baby (n. 61) | ||

| Miscarriage (n. 57) | ||

| Pregnant (n. 50) | ||

| Behçet’s disease | Pregnancy (n. 3) | n.2 |

| Pelvis (n. 2) | ||

| Son (n. 2) | ||

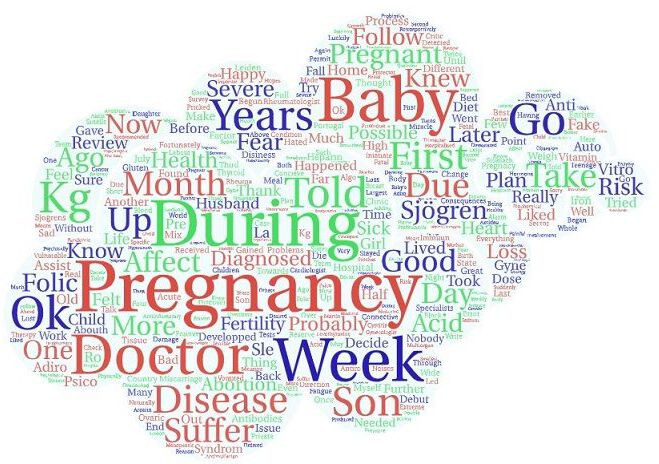

| Mixed connective tissue disease | Pregnancy (n. 14) | n.7 |

| Informed (n. 9) | ||

| Time (n.6) | ||

| Feel (n. 5) | ||

| Birth (n. 5) | ||

| Relapsing polychondritis | Developed (n. 3) | n.1 |

| Bed (n. 3) | ||

| Years (n. 2) | ||

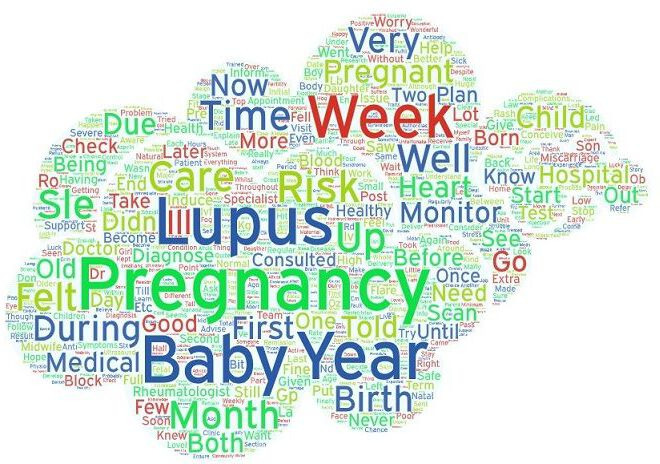

| Systemic lupus erythematosus | Pregnancy (n. 101) | n.44 |

| Lupus (n. 63) | ||

| Baby (n. 52) | ||

| Week (n. 42) | ||

| Year (n. 38) | ||

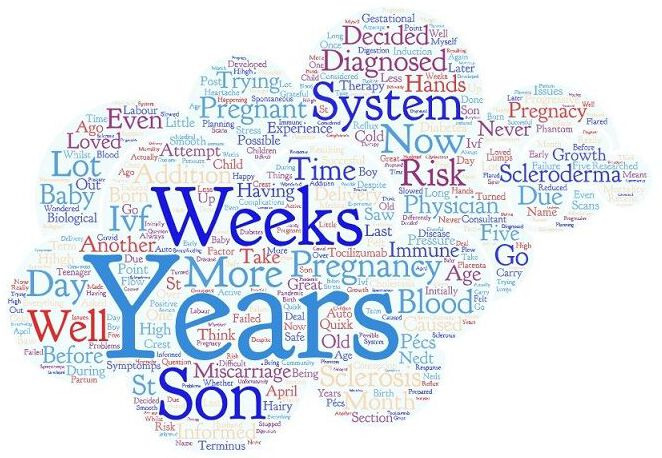

| Systemic sclerosis | Years (n. 7) | n.4 |

| Weeks (n. 5) | ||

| Pregnancy (n. 4) | ||

| System (n. 4) | ||

| Son (n. 4) | ||

| Sjogren’s syndrome | Pregnancy (n.18) | n.6 |

| Week (n.10) | ||

| Baby (n. 10) | ||

| Doctor (n.9) | ||

| Years (n.7) | ||

| Undifferentiated connective tissue disease | Pregnancy (n.5) | n.2 |

| Weeks (n. 4) | ||

| Time (n. 4) |

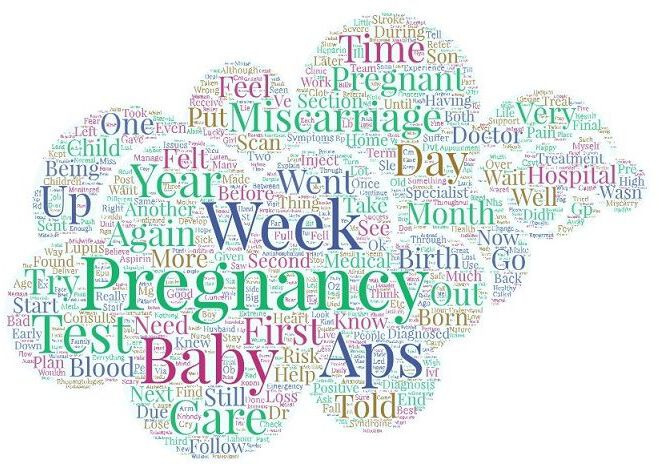

Figure 3.

Most frequent words used in the Behçet’s disease patients’ stories.

Figure 4.

Most frequent words used in the Mixed connective tissue disease patients’ stories.

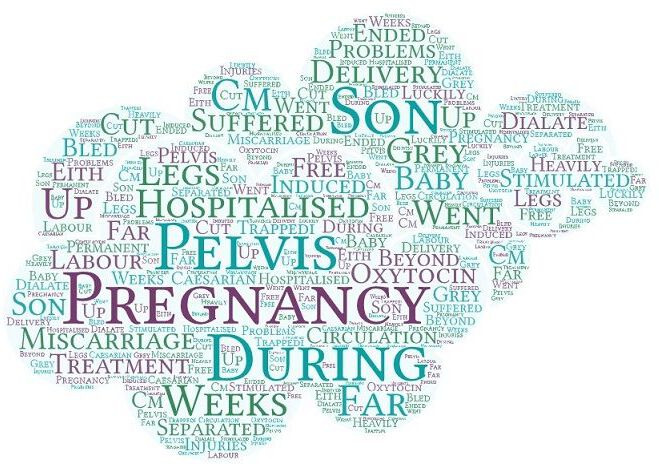

Figure 5.

Most frequent words used in the patients’ stories.

Figure 6.

Most frequent words used in the Sjögren syndrome patients’ stories.

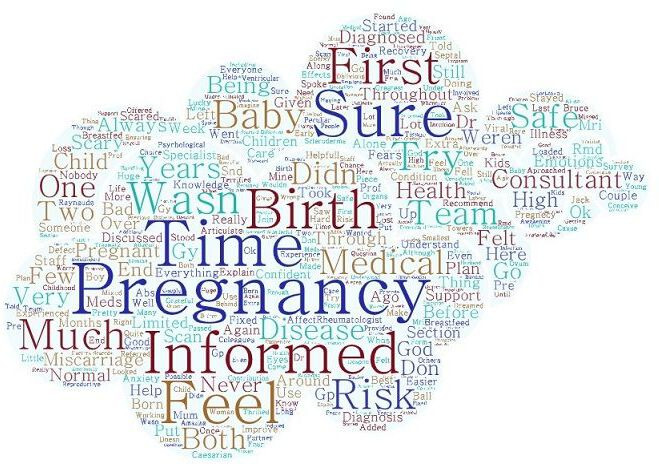

Figure 7.

Most frequent words used in the systemic lupus erythematosus patients’ stories.

Figure 8.

Most frequent words used in the systemic sclerosis patients’ stories.

Figure 9.

Most frequent words used in the Undifferentiated connective tissue disease patients’ stories.

After a deep reading of the stories performed by both the experts in NBM and by the patients’ panel, a list of transversal topics were identified from the most common mentioned in the stories, discussed together and agreed in a dedicated web meeting. The transversal topics identified together with the patients’ panel were communication, training and information, the need for an appropriate referral process and the importance of adopting a holistic approach, rather than just focusing on the disease activity.

In order to structure the analysis of the stories by means of the NBM approach, the results are reported based on the main phases related to pregnancy: prepregnancy, during pregnancy, after pregnancy. ‘Miscarriage’ was added as it was considered by the patients’ panel as a very relevant topic to be highlighted in a dedicated paragraph.

Prepregnancy

‘I’ve been there when your consultant says you won’t be able to ever have children because you are too ill and your disease is too aggressive.’ Only a few stories (n.2) mentioned prepregnancy counselling, and patients underlined that little information was provided on aspects such as how to plan the pregnancy, possible risks, possible treatments that could be taken during breast feeding, what to expect after pregnancy and the disease evolution during and after pregnancy. The main emotions reported for this phase included fear, worry, anxiety and uncertainty on the ability to take care of the baby, of losing the baby and of ‘passing the disease’ to the child.

During pregnancy

‘I just wish someone had cared enough to actually listen to me and to take the time to find out what was really going on. I wasn't even referred to a rheumatologist because my ana was negative’ Not many stories (n. 5) mentioned regular multidisciplinary monitoring for their disease during pregnancy. Patients who mentioned in their stories that they were treated in excellence centres also reported appropriate care and information, but often healthcare professionals (HCPs) were not perceived by the patients as being appropriately trained on the possible risks related to pregnancy in rCTDs. Stories suggested considering the possibility of having access to medical records for all HCPs involved in the care of the patient, especially the general practitioners (GPs) and the team that takes care of the pregnancy (gynaecologists, obstetricians, etc). Stories also described that dealing with daily treatments and lots of medical appointments during pregnancy can be really overwhelming and that this can cause a sense of being overtreated and/or lead to being less adherent to the treatments and to the prescriptions of the specialists. Many stories mentioned that patients were diagnosed during their pregnancy or after having had different miscarriages, and it was highlighted that care should be focused not only on the baby but also on the mother and where possible also on the partner. Since the stories were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic period, similarly to other previous works,18 patients described the interruption of care experienced while they were pregnant during the pandemic and have strongly requested that during these kinds of emergencies, care for fragile and complex patients should always be ensured, especially in case of pregnancy.

The main emotions reported in the stories during pregnancy were the constant fear of losing the baby, of becoming a parent and of not being able to care for the baby due to their disease.

After pregnancy

‘He is light on my life.’ Not many stories mentioned follow-up consultations or psychological support for the mother and the couple after pregnancy (n.6). The main topics mentioned by the patients included the uncertainty related to taking treatments during breastfeeding and the lack of appropriate information on the management of their treatment plan while breastfeeding. In fact, some patients spontaneously suspended treatments after pregnancy without asking the opinion of their clinician. Another frequent and crucial topic addressed in the stories is the difficulty of the patient in taking care of the babies once they are born and the need to receive support for the management of the new-born, especially emotional, psychological and practically. Happiness for the birth of the baby, a sense of relief and fear of not being able to care for the baby were the main emotions expressed in the stories when describing the post-delivery phase.

Miscarriage

‘No woman should have to give birth or discuss miscarriage in a maternity unit.’ Miscarriage was a frequent and painful experience reported in more than 40 stories. ‘As reported in table 2, the majority of the respondents were either diagnosed before starting or planning their pregnancy (50.39%) or during the pregnancy (10.85%). On the other hand, 38.76% of respondents were not yet diagnosed at the beginning or during of their pregnancy. These results were often discussed in the patient’s stories, that described how the problems experienced during their pregnancy/miscarriages lead them to see a doctor and to perform examinations in order to understand their cause. Different stories (n. 15) have in fact reported that their diagnosis was formulated after different miscarriages or difficult pregnancy/ies.’ Among the 40 stories that reported miscarriages, the majority of them also reported that they had to go through multiple miscarriages (up to 11) and that they often had to insist on being referred to high-risk pregnancy clinic. In some cases, the referral to a high-risk pregnancy clinic was denied, despite having a diagnosis of rCTD and having had previous miscarriages. Being recognised as one of the worst experiences of their lives, many patients mentioned in their stories the importance of working towards reducing or even of preventing miscarriages as much as possible among rCTDs patients. In some cases, it was specifically suggested to plan a systematic referral for women to high-risk pregnancy clinics before having two miscarriages and to work towards the improvement of how care is organised for pregnant rCTDs patients. The stories also underlined the complete lack of emotional and psychological support after losses and suggested to offer help either professional and/or peer support for the couple. The main emotions described were devastation, grief for the loss, sense of guilt and being terrified to have future pregnancies.

After an intense discussion held with the patient’s panel on these results, a number of unmet needs were identified and a list of possible actions were designed in order to plan future studies and projects aimed at improving the care provided to rCTDs patients related to pregnancy and family planning. The unmet needs identified are reported in figure 10.

Figure 10.

Patients’ unmet needs in the management of pregnancy in rare and complex rheumatic diseases. HCP, healthcare professional; GP, general practitioner; rCTD, rare and complex rheumatic tissue disease.

Discussion

This work aimed to explore the perception of patients regarding their care and their journey before, during and after pregnancy and/or miscarriages in order to plan further actions to improve the care provided to rCTDs patients and their family during all the phases around pregnancy and family planning.

Several unmet needs in the management of pregnancy in rCTDs emerged from the analysis of the stories and from the discussion held with the panel of patients’ representatives. In particular, the fragmentation of care and of approaches among different centres when managing pregnancy in rCTDs patients was a central topic, together with the lack of education and of awareness of rCTDs and pregnancy by midwifes, obstetricians and gynaecologists. A specific pathway that could guide the care provided to the patient was in fact lacking and patients felt that very often there was no coordination of care and no direct collaboration among their specialist (rheumatologist or immunologist) and the HCPs that were taking care of their pregnancy. The need for specialised pregnancy clinics and a multi-disciplinary organisation of care seems to be a relevant topic in rCTDs,19 20 excluding of course centres of excellence, which are, at the moment, a very limited number of in Europe, especially on pregnancy and its planning management.

One of the main needs is also the provision of systematic emotional and psychological support during all the phases around pregnancy, both by providing a professional service by a psychologist and by offering the opportunity of joining peer-support groups and by getting in touch with patients’ organisations that can help during these delicate phases. The need of having HCPs able to consider not only the baby while providing care but also the mother and the partner was raised, as they often feel left out of the therapeutic decision-making process, making them not feeling part of the whole parenting experience. Moreover, according to the stories, patients and their partners perceive a wide range of changes during the planning and the actual pregnancy. These changes do have a significant impact on their lives, so providing appropriate psychological support was mentioned in the discussions with the panel as something that could contribute to reducing the burden on patients and partners and improving the pregnancy experience.

Despite the fact that most respondents were based in the UK and that this might had an impact on the results, it seems to be clear that there is a need in the patient community to discuss the care they are provided around pregnancy, and this was demonstrated by the fact that despite the survey was published only in English, different stories were collected in other languages. Besides, as reported in other studies,21 22 many of the unmet needs identified in our work are strongly related to communication and information and, in particular, to the lack of appropriate information and education on rCTD pregnancy-related issues within the HCPs and also among patients and their families. The provision of appropriate information to patients and families living with rCTDs on pregnancy and its planning in the clinical setting is perceived as a game-changer in enabling and empowering them to have a better experience and in being more aware of the journey that they will encounter.

On the basis of these unmet needs (summarised in figure 10), some proposals were identified with the help of the patients’ panel in order to improve the patients’ care before, during and after pregnancy/miscarriage. The definition of a formal referral process to pregnancy clinics and the codesign (patients and clinicians) of an organisational reference pathway for rCTD patients could have a strong impact on the experience of patients and eventually also on the disease and pregnancy management. This strategy could also include the identification of referral centres for pregnancy in rCTDs and the establishment of strong collaborative links among these centres and the HCPs taking care of the pregnancy (gynaecologists, obstetricians, etc). This strategy could represent a great step towards the promotion of appropriate care pathways for pregnancy. Referral to excellence clinics means increased monitoring and being well taken care of before, during and after pregnancy, especially when a multidisciplinary approach is organised, as it is well known that working across medical fields ensures best care for patients.23

In addition, it is evident that the organisation of training and educational activities both for HCPs as well as for patients and families is crucial in providing a tangible contribution to improve the experience of patients and also to better support the patient–clinician relationship.

Conclusions

Exploring the experiences of patients and families during the different phases of pregnancy and its planning by means of the NBM approach enabled the identification of different unmet needs and to outline a strategy to improve care for rCTD patients and families. A strong collaboration among different stakeholders, such as the RheumaPreg group and ERN ReCONNET, is expected to unite in order to address these unmet needs and improve the experience and the care provided to rCTDs patients.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the RheumaPreg group.

Footnotes

Twitter: @DianaMarinello

Contributors: DM: conception of the work; design and direction of the project, drafting the work, acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published, agreement to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved, guarantor of the work. DZ: drafting the work, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. IP: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. SA: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. IG: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. MH: revision of the work and final approval of the version to be published. SS: revision of the work and final approval of the version to be published. LS: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. DT: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. CB: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, critical revision of the work for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. LC: analysis and interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published. AG: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published. ST: acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data for the work final approval of the version to be published. AB: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. MK: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. YS: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. AT: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. RT: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, analysis and interpretation of data for the work, final approval of the version to be published. CT: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published. MM: substantial contributions to the conception of the work; revising the work critically for important intellectual content, final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient and public involvement statement: A panel of patients’ representatives was identified to represent different diseases and different countries. Experts have supported the patients’ panel and gathered the representatives via online meetings and email communications. Patients’ representatives were involved since the co-design of the survey and co-designed the survey questions as well as replies. They also participated in the interpretation of the stories collected, in the identification of unmet needs and in the design of possible strategies aimed at addressing the unmet needs. Patients’ representatives also reviewed the manuscript to provide their input and contribution. Patients’ representatives also contributed to the dissemination of the survey in the patient communities by co-designing the launch of the survey and the related communications and also supporting the dissemination personally in their social media/channels.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Zucchi D, Tani C, Monacci F, et al. Pregnancy and undifferentiated connective tissue disease: outcome and risk of flare in 100 pregnancies. Rheumatology 2020;59:1335–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/kez440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tani C, Zucchi D, Haase I, et al. Are remission and low disease activity state ideal targets for pregnancy planning in systemic lupus erythematosus? A multicentre study. Rheumatology 2021;60:5610–9. 10.1093/rheumatology/keab155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gupta S, Gupta N, Syndrome S. And pregnancy: a literature review. Perm J 2017;21:16–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munira S, Christopher-Stine L. Pregnancy in myositis and scleroderma. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2020;64:59–67. 10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2019.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tardif M-L, Mahone M. Mixed connective tissue disease in pregnancy: a case series and systematic literature review. Obstet Med 2019;12:31–7. 10.1177/1753495X18793484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tincani A, Dall'Ara F, Lazzaroni MG, et al. Pregnancy in patients with autoimmune disease: a reality in 2016. Autoimmun Rev 2016;15:975–7. 10.1016/j.autrev.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.El Miedany Y, Palmer D. Rheumatology-led pregnancy clinic: enhancing the care of women with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy. Clin Rheumatol 2020;39:3593–601. 10.1007/s10067-020-05173-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andreoli L, García-Fernández A, Chiara Gerardi M, et al. The course of rheumatic diseases during pregnancy. Isr Med Assoc J 2019;21:464–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Förger F, Østensen M, Schumacher A, et al. Impact of pregnancy on health related quality of life evaluated prospectively in pregnant women with rheumatic diseases by the SF-36 health survey. Ann Rheum Dis 2005;64:1494–9. 10.1136/ard.2004.033019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ackerman IN, Jordan JE, Van Doornum S, et al. Understanding the information needs of women with rheumatoid arthritis concerning pregnancy, post-natal care and early parenting: a mixed-methods study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2015;16:194. 10.1186/s12891-015-0657-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Østensen M. Counselling women with rheumatic disease--how many children are desirable? Scand J Rheumatol 1991;20:121–6. 10.3109/03009749109165287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenhalgh T, Hurwitz B. Narrative based medicine: why study narrative? BMJ 1999;318:48–50. 10.1136/bmj.318.7175.48 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Talarico R, Cannizzo S, Lorenzoni V, et al. RarERN path: a methodology towards the optimisation of patients' care pathways in rare and complex diseases developed within the European reference networks. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2020;15:347. 10.1186/s13023-020-01631-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.. Available: https://reconnet.ern-net.eu/

- 15.Talarico R, Aguilera S, Alexander T, et al. The added value of a European reference network on rare and complex connective tissue and musculoskeletal diseases: insights after the first 5 years of the ERN ReCONNET. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2022;40 Suppl 134:3–11. 10.55563/clinexprheumatol/d2qz38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.. Available: https://www.rheumapreg2021.com/

- 17.. Available: https://ec.europa.eu/eusurvey/home/welcome

- 18.Talarico R, Aguilera S, Alexander T, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on rare and complex connective tissue diseases: the experience of ERN ReCONNET. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021;17:177–84. 10.1038/s41584-020-00565-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Emadi S, Abutiban F, El Zorkany B, et al. Enhancing the care of women with rheumatic diseases during pregnancy: challenges and unmet needs in the middle East. Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:25–31. 10.1007/s10067-015-3052-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andreoli L, Bazzani C, Taraborelli M, et al. Pregnancy in autoimmune rheumatic diseases: the importance of counselling for old and new challenges. Autoimmun Rev 2010;10:51–4. 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wolgemuth T, Stransky OM, Chodoff A, et al. Exploring the preferences of women regarding sexual and reproductive health care in the context of rheumatology: a qualitative study. Arthritis Care Res 2021;73:1194–200. 10.1002/acr.24249 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Phillips R, Pell B, Grant A, et al. Identifying the unmet information and support needs of women with autoimmune rheumatic diseases during pregnancy planning, pregnancy and early parenting: mixed-methods study. BMC Rheumatol 2018;2:21. 10.1186/s41927-018-0029-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Añón-Oñate I, Cáliz-Cáliz R, Rosa-Garrido C, et al. Multidisciplinary unit improves pregnancy outcomes in women with rheumatic diseases and hereditary Thrombophilias: an observational study. J Clin Med 2021;10. doi: 10.3390/jcm10071487. [Epub ahead of print: 03 04 2021]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.