Abstract

Faced with a series of COVID-19 related lockdowns in Australia across 2020 and 2021, and anxious about the safety of our research participants, we developed a novel approach to body mapping, an arts-based research method typically undertaken in-person. We produced a facilitated body mapping workshop hosted via an online videoconferencing platform. Workshops brought together 29 participants with disability, mental distress and/or refugee background who used body mapping to represent their embodied experiences of stigma and discrimination. These workshops generated rich data, and participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the process. In this paper we describe our novel approach to body mapping, and share practical tips for others who wish to undertake body mapping remotely. We outline strengths associated with this method: increased accessibility, enhanced connection between participants, the formation of a space to explore challenging subject matter, the production of rich data, and the creation of diverse body maps. We also discuss shortcomings and challenges which those considering the method should be aware of: increased logistical burden, demands related to space, IT difficulties, the danger of over-sharing, and diminished cohort sizes. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to report on body mapping facilitated via web-based workshops. Here, we seek to provide practical advice and useful insights for others hoping to utilise body mapping online.

Keywords: body mapping, arts-based research methods, online research, COVID-19, stigma, discrimination

Background: COVID-19 and the Move to Body Mapping Online

At the beginning of 2020, we commenced a research project investigating women’s1 experiences of marginalisation, stigma, and discrimination resulting from their lived experience of disability, mental distress, and/or refugee background (Boydell et al., 2020). We felt an embodied approach to this research was imperative as it would help us understand the lived, and felt, experiences of participants. In view of this, and given the potentially distressing subject matter, we sought a research method that would allow an embodied focus and give participants latitude to respond to research questions in ways that felt comfortable to them. We decided to use body mapping, an arts-based research method. Typically, body mapping involves tracing a participant’s body outline on to a large sheet of paper. This outline is then decorated with images, text, and collage. These maps are made during face-to-face workshops in which a facilitator guides the participants through a series of reflective exercises to assist them in the creation of their map (de Jager et al., 2016). Body mapping emerged from a community development and social justice context and is oriented towards participant empowerment (see for example, Solomon, 2007), as it gives participants freedom to represent their experiences as they see fit. Body mapping – like other art activities (Fancourt & Finn, 2019) – can also be associated with positive therapeutic outcomes that can mitigate distress or discomfort resulting from discussing difficult or traumatic events (Boydell et al., 2018).

Body mapping has been utilised in diverse research settings and is increasingly deployed in the context of health research (Boydell, 2021). Our research team have experience using body mapping with diverse cohorts (see for example, Dew et al., 2018; Malecki et al., 2022; Vaughan et al., 2021) We originally planned to invite participants to undertake three x two-hour in-person workshop sessions during which they would create a body map that visually represented their experiences of stigma, discrimination, and marginalisation. Workshops were to be followed by a one-on-one interview in which participants discussed their maps and the experiences that informed their creation (Boydell et al., 2020).

As we prepared our ethics protocol and our newly formed research team got to know each other, Australia went into an extended lockdown in response to the COVID-19 pandemic (Storen & Corrigan, 2020) meaning face-to-face data collection was off the table. In early 2021, pandemic restrictions began lifting and COVID-19 cases decreased. We felt hopeful that our body mapping workshops could finally commence. We started to recruit participants, purchase art-making supplies, and ready ourselves. Prior to our first round of workshops the Delta variant triggered further lockdowns, again preventing in-person data collection. We felt stuck – participants were recruited, our prep work was done, and there was no immediate end to lockdown in sight. We began to consider the possibility of body mapping online using videoconferencing software such as Zoom. We envisioned mailing art materials to participants and then meeting online for group workshops.2 While we were aware of several innovative digital body mapping approaches – e.g., a web-based application for body mapping (Ludlow, 2021), and virtual reality and wearable body mapping technologies (Edwards, 2021; Ticho, 2021) – we felt that, given the technical requirements and know-how associated with these approaches, the creation of physical maps via online workshops would be most accessible for a greater number of participants.

Initially, our team was trepidatious about the prospect of mapping online; would our participants feel supported working online, would they be bored during our extended workshops, and would we be able to collect rich data? After receiving constructive guidance and support from our lived experience Advisory Group and newly recruited lived experience workshop facilitators/researchers, we took an inclusive, trauma-informed approach to produce an online body mapping workshop. Over the course of late 2021 and early 2022 we conducted six workshops online (each made up of two x three-hour sessions) with 29 participants (≈five participants per workshop group). This research project was approved by the University of New South Wales Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) on 22 January 2021 (Ethics Protocol Number: HC200667). Participants provided written informed consent prior to participation in this research. They also re-affirmed their understanding of the research process, and their consent, during the first workshop by completing a brief web-survey.

Drawing on feedback collected from research participants during workshops, post-workshop interviews, and on our own reflections as workshop facilitators/researchers, this paper reports on the novel online body mapping facilitation method we developed and delivered. We share an overview of this method, discuss the process of its development, and outline methodological strengths and weaknesses for the consideration of others who might wish to undertake body mapping online. As far as we are aware, this is the first report to outline a methodology for body mapping online via videoconferencing technology. Our goal is to share our approach and key learnings with others who wish to undertake body mapping in this way. Further, we seek to contribute to an emerging body of literature that explores the process of conducting research during the pandemic (see for example, Hill et al., 2021; Leese et al., 2022; Self, 2021; Vaughan et al., 2022).

Preparing to Body Map Online

Central to our preparation for online mapping was the composition of a body mapping facilitation guide, which outlines the workshop process. To produce this guide, we set about modifying our original, in-person workshop protocol which was based on the work of Gastaldo et al. (2012). This face-to-face protocol outlined the content of three x two-hour workshops: workshop one introduced research aims to participants and supported them to produce a body-outline, workshop two supported participants to decorate this outline, and workshop three facilitated the completion of participants’ body maps.

In authoring the online body mapping guide, we sought to strike a balance between maintaining fidelity to the in-person body mapping approach (which we have previously validated), while making strategic changes to mitigate against the challenging aspects of web-based videoconferencing. We anticipated four core challenges: (1) fighting boredom and nurturing engagement, (2) fostering a sense of connection online, (3) ensuring participant safety and support, (4) logistics emerging from body mapping solo. These challenges and our response to them are outlined below.

Fighting Boredom and Nurturing Engagement

We were concerned that body mapping online might be tedious and could leave participants feeling disengaged. To mitigate against boredom and in an attempt to address participant attrition due to what’s been called ‘Zoom fatigue’ (Nesher Shoshan & Wehrt, 2022), we decided to condense the workshop process, providing two workshop sessions (each with a duration of 3 hours), rather than three workshops (with a two-hour duration) as originally planned. We did not want to include extended didactic speech from facilitators (e.g., delivering long swathes of instructional information to participants) and also wanted to make sure we were not prescribing extended stretches of solo map-making. Our solution was to create a far more structured, interactive workshop than had been planned for in-person mapping. In session one, we utilised a reflective mindfulness exercise to introduce the research aims in an interactive manner. We also introduced a series of preparatory drawing activities intended to help participants engage with research questions, explore approaches to visually representing their experiences, and overcome any anxiety about working creatively.3 Several participants commented that these activities helped them gain confidence and overcome anxiety about visually representing aspects of their lives. As participant P9 noted, ‘I really loved all those little exercises, I was looking [back] at my note-drawings…I actually came up with much more creative things… [in] just this short exercise’.

The second workshop session was intended to support participants to decorate their body map. During in-person mapping, this session is typically much less information-heavy, and less structured than session one. We felt it was important to bring structure into this session, in order to maintain a sense of connection between attendees. To this end we included a handful of creative activities across the session (e.g., working with objects to explore symbolic representation on maps, and a writing exercise to help participants determine if they’d like to include text on their maps). When it came time for participants to work solo on their own maps for an extended period of time, we used music to help maintain the sense of working in a shared space. With the permission of participants, we played gentle, unobtrusive classical music.4 We used the cessation of this music to signal to participants that we would be coming back together to chat, do a group activity, or bring something to their attention. Participants reported that they enjoyed creating to music and found working in a group setting enjoyable and productive. As participant P28 stated, when asked what self-care activity they would undertake after the close of session two, ‘I think I’m going to listen to some more music…It’s been like I’ve been in a relaxed state [working on my map]’. In this way the online workshops offered participants access to ‘body doubling’; a motivational way to work collectively and collaboratively, yet independently (Valentine, 2022).

Fostering a Sense of Connection

As we prepared to map online, we were concerned that it might be difficult to foster a sense of trust and connection in an online environment. In previous projects involving in-person mapping, we built-in time to chat, mingle and share food to facilitate rapport building, and to help foster a sense of psychological safety. Group videoconferencing is decidedly not conducive to organic mingling. So, to mitigate against participants feeling disconnected, or awkward about sharing their experiences or artworks, we included regular time for participants to share their thoughts, experiences, emotions, and artworks. We paired each creative exercise with a period of reflective group discussion to support respectful sharing and also regularly invited participants to hold up their artworks to the screen so others could see what they’d worked on (Figure 1). As outlined below, this reflective discussion largely had a positive impact. Many participants reported feeling a sense of connection with others taking part and noted that sharing their experiences of stigma and discrimination with people in the ‘same boat’ made them feel seen, supported, and understood. As participant P4 noted, ‘pretty much every other person in the workshop had also experienced something, so it made you feel a lot less alone’. Further, working alongside one another creatively enhanced this feeling of connection. As participant P8 reflected:

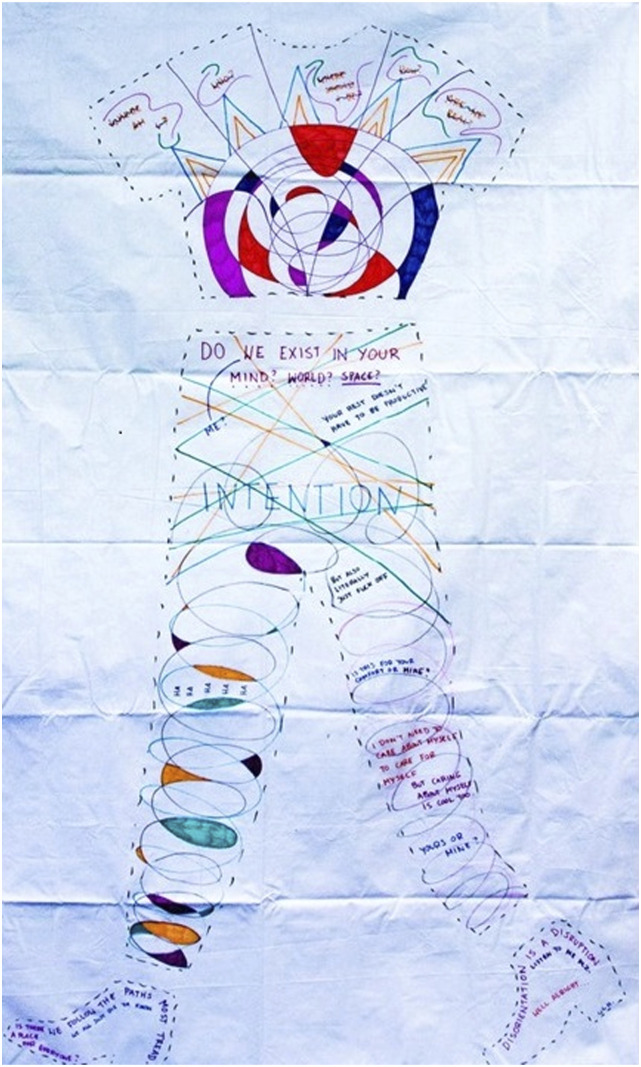

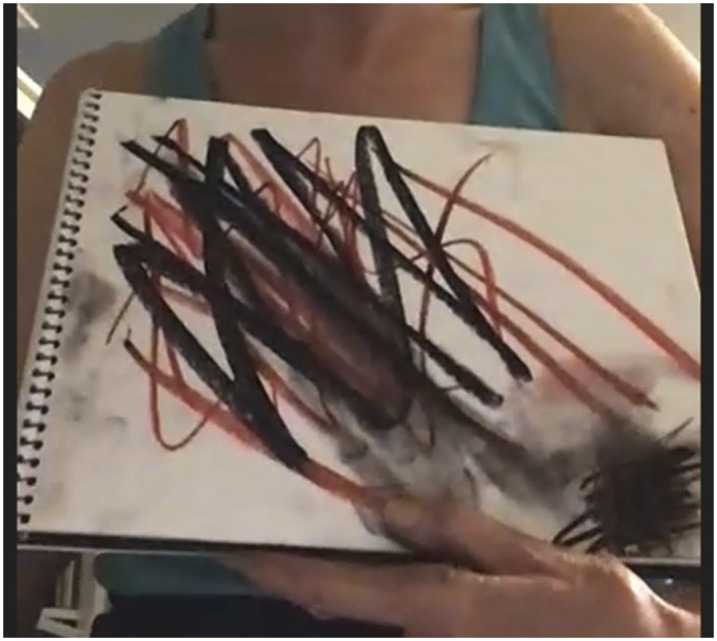

Figure 1.

Participant sharing a drawing created during a preparatory exercise exploring abstract mark making.

… being in a group of people that you don’t even know and having that time to do the activities that we did, and then share them, and connect with other people’s experiences and how they represented it in drawing and words and things like that, was just – it’s been an amazing experience…coming together with those people and having that ability to be open and to be prompted by questions that you guys had for us, it was just incredible. It was a really good experience.

Participant Support and Safety

As we prepared to take the workshops online some team-members felt nervous about providing support to participants if they experienced distress during the online workshops. If a participant experiences discomfort during an in-person workshop, there are certain immediate steps that can be taken to make the individual more comfortable while a referral is organised or a supporting psychologist is contacted (such as getting the participant a glass of water, or finding them a comfortable, quiet space to rest etc.). Working online using videoconferencing, we knew these small physical supports would not be possible, and we would need to rely on verbal comfort. We also knew we would have less of an opportunity to visually identify if an individual was experiencing distress and would need to rely on a participant informing us that they needed support (verbally or using the chat function). Recognising this, we set out to inculcate a supportive, informal tone across the workshops, so that participants would feel comfortable sharing their needs or asking for assistance. For example, we invited participants to interrupt us at any time during a session if they needed something or wanted to ask questions, we also regularly checked in with participants to see how they were feeling. We made sure safety and support procedures were clear to all participants. For example, procedures were circulated to participants prior to workshops taking place, and then re-circulated at the beginning of each workshop using the chat-function. We also requested that participants bring awareness to their emotional wellbeing across the sessions and asked them to let us know if they felt any discomfort as a result of the work we undertook. We affirmed their right to withdraw consent, or to leave the workshop at any time without having to explain. We also began the first workshop sessions by creating a Safety and Learning Agreement. This document was co-authored by all members of the workshop group and outlined how we would work together to ensure we all felt comfortable and safe (see Table 1). Finally, we emailed participants between workshop sessions, to check in on their wellbeing, and make sure they had the safety and support information in the form of an email. Fortunately, no one reported adverse effects during the workshops and many participants reflected on the positive impact of the sessions, explaining that they had found them pleasurable and interesting. For example, as P14 commented, ‘I so enjoyed it. More than I thought I would… it was a really nice experience’. However, as outlined below, some participants reported discomfort in the aftermath of the process (see discussion in Shortcomings section below).

Table 1.

Example of Safety and Learning Agreement Authored by Participants and Facilitators.

| Purpose | Safety and Learning Agreement |

|---|---|

| Participants and facilitators co-create an agreement that outlines how they will work together and what can be done to make all involved feel safe, comfortable, and supported [for more detail see Supplement Appendix 1] | 1. Respect other people’s sharing |

| 2. Don’t share what you’ve learnt in the workshop – respect privacy = what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas! | |

| 3. Don’t judge ourselves – these are our stories and there is no right or wrong way to tell and represent these | |

| 4. Be open minded about whatever comes up for ourselves and others | |

| 5. Be understanding and supportive of other people’s experience | |

| 6. Know that sharing your experiences can be hard but sharing will help others explore their experiences too. Be mindful of practising safe disclosure and purposeful storytelling in the group. Only share what you feel comfortable with and try to be mindful of potentially triggering yourself and others | |

| 7. Have respect for the diversity of lived experience in the room | |

| 8. Respect different learning styles in the room – be mindful and respectful about the different ways people learn | |

| 9. It’s okay to be vulnerable and authentic | |

| 10. Make sure we take care of ourselves, nurture ourselves, look after ourselves during and after the session |

Mapping Solo

For some, body mapping can be inaccessible, including for some people with disability or chronic pain. This is because to make a body map a person must lie down and/or work on the floor (to have their body traced to form the basis of the map, or to decorate their map). With the guidance of our advisory group, when writing both our face-to-face and online facilitation guide, we made a number of provisions to try and make the mapping process more accessible. For example, we devised some alternative mapping approaches that did not require working on the floor. These included taping a map to a wall or table, or inviting participants to work on an A4 piece of paper using a pre-drawn, or their own hand-drawn, body outline and then reproducing these on a large-scale for knowledge translation activities (see below). Those who felt uncomfortable tracing their body, or dissatisfied with working on a small-scale, would be invited to represent their bodies symbolically (e.g., a participant might draw a house to represent their body as the ‘home’ for their emotions and this house would be used as the basis for the map). During the online workshops, a number of participants produced A4-sized maps, drew their body outlines (rather than tracing them), or represented their bodies symbolically.

Taking this flexible approach to conceptualising what counts as a body map also helped us to address a central logistical hurdle of mapping online: how to trace someone’s body when they are mapping solo. When mapping in-person, participants pair up and trace each other’s bodies. When mapping online participants were often working alone in their homes without immediate (or indeed any) access to someone who could trace their bodies. To get around this, we made the act of creating a bodily outline an activity that participants undertook as ‘homework’ in between session one and session two (see Supplement Appendix 1 for details). If participants were not able to have someone trace their bodies, or felt uncomfortable with this approach, we suggested workarounds based on the alternative mapping approaches described above. Participants also devised their own ingenious alternatives to body tracing; for example, a participant who felt uncomfortable having their body traced, laid out clothes on their piece of fabric (shirt, pants, shoes) and traced these to create a bodily form (Figure 2).

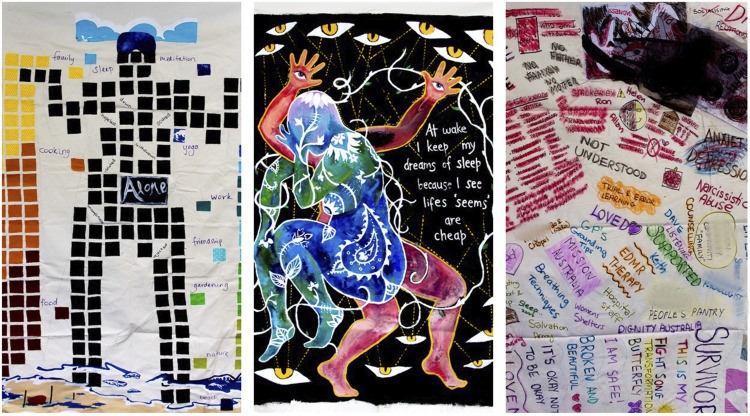

Figure 2.

Body map created by tracing clothing to produce a body-outline.

Workshop Structure

Tables 2 and 3 provide a summary of the online body mapping guide we produced. Appendix 1 provides a detailed overview of the guide, including examples of a script for facilitators. We invite anyone considering engaging in online mapping to utilise or adapt this guide to reflect their own research aims.

Table 2.

Brief overview of Session One.

| Activity | Aim of Activity |

|---|---|

| Welcome | To welcome participants and orient them regarding the research project and the process of body mapping. To introduce safety and support information and protocols. To ensure participants are comfortable using videoconferencing software |

| Introductions | To help participants/facilitators get to know each other and to ‘check-in’ by sharing any worries or hopes about the workshop process, or sharing anything about themselves they’d like the group to know (e.g., their pronouns, something about their lived experience, or their motivation for joining the research project) |

| Safety and learning agreement | To co-author a safety and learning agreement that outlines how participants and facilitators want to work together and what they need in order to feel safe and supported throughout the process [see Table 1] |

| Mindfulness activity | To help participants focus on embodiment and their embodied experiences (in preparation for representing these visually) |

| Three quick drawing activities with eyes closed | To help participants overcome any inhibitions or anxiety they have about drawing and to experiment with visually representing feelings and experiences associated with the research questions |

| Abstraction (four short drawing exercises) | To support participants to experiment with different approaches to visualising their experiences. In these exercises the focus is on abstract or non-figurative depictions |

| Representation and symbolism (three short drawing exercises) | To support experimentation with figurative/representational and symbolic approaches to visually representing experiences and feelings |

| Final creative exercise (extended drawing exercise utilising elements from previous exercises) | To consolidate learning from previous activities and to support participants to revisit drawings, or approaches to drawing that they previously found interesting or productive |

| Body shapes and outlines | To get participants thinking about how they want to represent their bodies on their maps and to work out the logistics of tracing their bodies on maps |

| Considerations for session two | To introduce session two and advise participants about homework between sessions (e.g., create your body outline. Bring an object to the next session that reflects you, your experiences, or something else relevant to the ideas you are exploring on your map). To allow participants to ask questions about either workshop session one or the forthcoming session two |

| Closing the session | To give participants an opportunity to share feelings, thoughts or feedback about the session. To ‘check-out’ by inviting participants to share one self-care activity they would like to commit to after the workshop (e.g., have a cup of tea, read a book, watch a favourite television show, have a walk etc) |

Table 3.

Brief Overview of Session Two.

| Activity | Aim of Activity |

|---|---|

| Welcome | To welcome participants and re-circulate safety and support resources, and their safety and learning agreement |

| Check-in | To provide participants with the opportunity to share anything they’d like the group to know about how they are feeling, or to share any reflections or thoughts about the previous workshop session |

| Body outline | To establish if participants had the opportunity to create a body outline prior to this workshop session. To assist participants who were not able to do this |

| Object reflection exercise | To invite participants to think reflectively about the experiences they’d like to represent on their map using an object of their choice. To invite participants to create an image related to these reflections, and to share this image with the group |

| Filling the map | To assist participants to begin the process of decorating their maps |

| Using text or a slogan | To guide participants through a reflective exercise to assist them in identifying text to add to their map |

| Further mapping | To invite participants to continue decorating their map, and to invite them to share their progress with the rest of the group |

| Wrap-up | To explain the next steps in the research process |

| Check-out | To check in with participants and to invite them to share any final reflections. To share self-care to be undertaken after the session closes |

After the workshops

At the close of the second workshop, we invited participants to continue to work on their maps if they needed more time to complete them. Some participants worked for a few more hours, others took several weeks. Once a map was complete (or as it was being finished, as per participant preference), we organised one-on-one interviews with participants via videoconference or phone. Prior to interviews, participants shared photographs of their maps so researchers could prepare appropriate interview questions. Participants mailed completed maps to the research team for analysis and knowledge translation activities.

Logistical and Other Considerations

Beyond the adaptations to the workshop process outlined above, body mapping online requires various logistical and other actions to ensure its smooth operation.

Materials and Postage

Prior to workshops mapping materials need to be delivered to participants. In the weeks prior to their workshop commencing, we posted our participants a ‘starter-pack’ of art materials: a large sheet of calico fabric (see below), some squares of coloured fabric (fat-quarters used by quilters), coloured ribbon, a needle and thread, a selection of coloured markers (approx. six), glue, some sheets of paper, and a pencil. We also mailed participants pre-paid self-addressed mail satchels so they could post their maps back to us for analysis. In addition to these materials participants often utilised other art supplies they had in their homes (such as paints, cut outs from magazines, charcoal and oil pastels). If budget allows, it is worth equipping participants with a larger selection of materials than we were able to provide (such as a set of acrylic paints, paint brushes, or a 36 pack of markers) so that those without art materials at home can experiment freely with colours and textures when mapping.

We chose to use calico fabric as the base for body maps, rather than the oft used paper. Calico is hard-wearing, can be drawn and painted on with a variety of materials without colour-bleeding, and can be easily manipulated by participants (e.g., cut, reshaped, sewn-on). Further, calico is cheaper than the heavy art paper (160 gsm) we have typically utilised in body mapping, and is significantly easier to cut, transport, store, and mail to participants. We sent each participant a segment of calico that was approximately 180 cm wide and 200 cm long to accommodate a full-length body outline.5

Accessibility

For some participants, online workshops were more accessible than face-to-face sessions (e.g., they were COVID-safe, could be accessed at home, didn’t require travel etc.). However, as Liz Bowen has observed, it is a mistake to suppose ‘that “online” automatically means “more accessible”’ (2021). Researchers considering mapping online should budget for accessibility costs to support participation online if required (e.g., the provision of sign language interpreters, or live-captioning to ensure accessibility during workshops). Once a participant had joined our study, we asked them to let us know if they had any access or support requirements which we could accommodate to make the workshop accessible. Our participants advised us of a number of simple actions we could take such as using the videoconferencing software’s chat function to share a written version of facilitators’ oral instructions, enabling the videoconferencing’s real-time auto-transcription function (which should be noted, is not always accurate), accommodating the attendance of support workers, building-in regular breaks, and accommodating alternative modes of body mapping (as described above).

Facilitators

While it might appear self-evident (at least in the context of mental health research (see for example, Black Dog Institute, 2020)), we believe it is important to acknowledge that a key element of the success of our online workshops was the participation of facilitators with personal, lived experience of disability, mental distress, and/or a refugee background. Several participants reflected that knowledge and insights provided by lived experience facilitators helped them feel safe and understood. For example, participant P25 recounted that after sharing an experience of discrimination with the group, lived experience facilitator AB was ‘very affirming and she actually said, I’m sorry you experienced that’. The participant felt this response helped her recognise that she should not have had to experience this discrimination, challenging self-stigma that she held.

When possible, we suggest sharing facilitation duties between several people. We found that having three facilitators for a moderately sized group (five to seven participants) worked well. Allowing different facilitators to take charge of specific sections of the workshops has the effect of varying the rhythm and breaking-up the session. Further, facilitators who are not presenting can then be on hand to provide ad-hoc, one-on-one support to participants (e.g., by meeting them in a break-out room, or phoning them at their request). This also allows any facilitator to rest as needed (e.g., for a toilet break, if they feel upset due to workshop discussion, as a result of IT troubles, or if they require some time-out for other reasons such as chronic pain or fatigue).

Other Considerations for Participants

To combat videoconference-fatigue we aimed to take at least a short break (e.g., three to 5 minutes) every 20 minutes. We also tried to be responsive to participant needs by taking unscheduled breaks if required.

To help maintain participant momentum and engagement, we recommend facilitating the workshop sessions across two consecutive weeks. Further, if multiple workshops are planned, as in our case, we advise having the same cohort of participants working together across both sessions (rather than participants randomly attending two sessions). This is important as it maintains rapport and a sense of safety within those corresponding groups.

If possible, we recommend taking an adaptive approach to workshops and inviting feedback from participants during each session. We found this useful as participants shared lots of helpful insights about what they felt worked and what didn’t. For example, the first workshop session begins with a mindful body-scan to relax participants and introduce the research aims and questions. During one of the early workshops, a participant told us they found the body-scan stressful because they live with chronic pain and the process made them hyper-aware of their discomfort. So, we developed an alternative reflective exercise not focused on the body which could also be offered to participants. This exercise continued to evolve, with one of our team-members, Bronwen Ifred, re-writing it substantially (see Supplement Appendix 1 for the script articulating this exercise).

Finally, to acknowledge the contribution participants make to a body mapping research project (by sharing their expertise, giving their time etc.) we strongly recommend renumerating workshop participation in some way (e.g., gift cards for participants after each session).

Conclusion: Methodological Strengths and Shortcomings

We consider the online workshops to have been successful because they enabled us to collect rich data, and participants reported a high level of satisfaction with the process. By way of conclusion, we share strengths and weaknesses associated with this body mapping approach, that we feel others seeking to use this method should be aware of.

Strengths

1. Accessibility: Body mapping online allows participants to work from their homes. For many, this helped them to feel safe and comfortable during the process. As participant P16 observed, ‘I really liked it because we were together but separate…it was kind of a bit safer in some ways’. Further, a number of participants with disability, or who lived in rural or remote geographic locations, explained that it would have been difficult, or impossible, for them to take part in the research, had it been facilitated in-person.

2. Connection: As a result of incorporating regular group discussions into the workshop process, participants reported a sense of connection and solidarity with others attending the sessions. As outlined above, many participants commented on the value of sharing creative and reflective time with others who have lived experience of mental distress/disability/refugee background. Others wished our workshop sessions could have continued regularly, as they afforded them a safe, creative space to visit weekly.

3. Space to explore difficult terrain: Reflecting on experiences of stigma and discrimination sometimes meant that workshop attendees were canvassing difficult emotional terrain during group discussions. Co-creating the Safety and Learning Agreement helped to foster an environment of compassionate, non-judgemental sharing and listening which supported these kinds of discussions. Across the workshops participants and facilitators discussed a wide gamut of experiences – sharing tears, laughter, and many emotions in-between. Some team members felt concerned when participants cried while sharing or listening, as they had not encountered this in previous research. These fears were allayed when participants reported that they felt safe, supported, or a sense of catharsis resulting from sharing in a supportive environment. As participant P15 stated, ‘having the opportunity to speak your truth a little bit …it’s a fantastic opportunity to do that. I have put so much of myself on your map that I never thought I would. I didn’t start the process thinking that I would do that…It’s been healing.’ However, as described above, it is important to make sure that comprehensive safety and support mechanisms are in place before, during and after workshops, and that these are clearly and repeatedly communicated and accessible to participants. Depending on the research aims and questions, it may also be advisable to make clear that workshop sessions are not therapy sessions, and that when sharing, participants need to be mindful of the potential impact their disclosures may have on others (see shortcomings below for more on this).

4. Capturing rich data: During in-person body mapping workshops, researchers often document the process via audio or video recording, photography or note taking. However, because in-person workshops tend to be quite diffuse; characterised by organic, ad-hoc discussions between small groups of participants, it can be hard to capture the process fully. With participant permission, we recorded our online workshops. This meant that the discussion emerging from workshops formed a rich corpus of data which has shaped the findings of our research. Further, researchers undertaking post-workshop interviews could revisit workshop recordings to prepare for interviews.

5. More mapping time and visual diversity: In the final session of in-person workshops participants are typically expected to complete their maps and leave them with the research team for analysis. However, participants of online workshops were invited to complete maps in their own time and then mail these to the research team. Participants were able to work on their maps iteratively, refining their approach until happy with the outcome. Participants often utilised materials they had in their home (instead of, or in addition to the materials we posted them), as a result the maps are amongst the most visually diverse and detailed we have ever collected (Figure 3). This serves to emphasize the unique biographical stories captured by each map.

Figure 3.

Details from three body maps created by participants – showcasing map diversity.

Shortcomings

1. Logistical burden: Online mapping is more resource intensive than in-person workshops. For example, rather than simply arriving at the body mapping venue with art materials, these must be posted to participants in advance. Further, there are higher costs associated with the purchase of individual art kits, as opposed to the provision of a single set of art materials participants can share. Mailing materials and financing the postage of completed body maps also adds an additional cost. Finally, pre-posting resources means that participant attrition results in resource loss.

2. Access and space: As mentioned above, while facilitating the workshops online extended opportunities for access for some participants, the internet (and IT required for videoconferencing) are not always accessible, comfortable or appealing for everyone (Saad et al., 2022; Sheldon et al., 2007; Wherton et al., 2020). Participants with a refugee background were the least represented in our online workshops, and we have speculated that this was due to their virtual delivery (we later held in-person sessions to address this). Another key barrier to joining the online workshops is related to physical space. Body maps are large, and participants require physical space and privacy to undertake the body mapping activities and to share their stories during the workshops. Some potential participants were concerned they wouldn’t have the physical or emotional room to complete maps comfortably at home, and as a result, did not join the study. Some participants purposefully joined workshops that were scheduled at times when their housemates, or family members were not at home, as they didn’t want them to hear about the personal experiences and stories they were exploring and sharing via map making.

3. Glitches, fatigue, and other web foibles: Although we did our best to mitigate against videoconferencing fatigue, it is important to acknowledge that for some, working online is draining and feels unnatural. Discomfort produced by working online can be greatly exacerbated by tech issues with which, due to COVID-19, many of us a wearingly familiar: freezing, glitching, dropping out, or microphone or video malfunctions. The prospect of these tech challenges caused ongoing anxiety amongst the researcher-facilitators, leading AB to coin the term PIA (Persistent Internet Anxiety). While participants told us they enjoyed the online workshops, some still bemoaned that they couldn’t move around and check out other people’s maps, or chat one-on-one informally with facilitators or participants.

4. Too much sharing: We noted above that the increased opportunity for group discussion and sharing was a positive characteristic of body mapping online. However, it is important to note that for some participants this sharing had a negative impact. For example, one participant withdrew from the research as they felt overwhelmed and upset by what had come up for them in the aftermath of the first workshop session. Another participant felt triggered by an experience recounted by another attendee during group discussion and did not join the second workshop session, instead preferring to complete their map by working offline in consultation with the research team. Another participant (P22), who completed the workshops and created a body map, noted that sometimes engaging with other participants could be exhausting: ‘…hearing a lot of new stories…it’s just been a little bit emotionally exhausting for me’. While safe disclosure and purposeful storytelling techniques were often raised during the authoring of the Safety and Learning Agreement, some participants were not familiar with these concepts, or were unaware of their own storytelling boundaries. We believe that the project’s safety and support protocol, and the Safety and Learning Agreement creation process largely mitigated distress during workshops. Despite this, we strongly believe everyone has a right to participate in research and to feel safe while doing so. Researchers undertaking body mapping online (especially those exploring potentially difficult issues or experiences) need to be aware of the double-edged quality of group sharing. While it can be associated with positive outcomes, there is always the potential that individuals will experience distress as a result. Therefore, it is vitally important to have robust safety and support mechanisms in place, and to support participants to be aware of their emotional wellbeing and psychological safety, even if it means they need to withdraw from the project or find an alternative way of participating.

5. Small cohorts: While it is not necessarily a methodological weakness, we think it important to note that, in our experience, online body mapping is ideally suited to small cohorts. Workshops involving more than six participants can get unwieldy (e.g., they can run far longer than scheduled). Smaller groups allow facilitators to give all participants an opportunity to regularly share their reflections, thoughts, or artworks.

Although digital conferencing platforms can feel disembodied and disorienting, we were excited to discover that with careful planning, and a flexible and responsive approach to the needs of research participants, we were able to create a safe, reflective online space for engagement with embodied, lived experiences. Although there are shortcomings and challenges associated with body mapping online with which facilitators/researchers should be aware, the novel method outlined here offers a productive means of collecting rich data, in a manner that can be fun, engaging and psychologically safe for participants.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental Material for Exploring Embodied Experience via Videoconferencing: A Method for Body Mapping Online by Priya Vaughan, Angela Dew, Akii Ngo and Katherine Boydell in International Journal of Qualitative Methods

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the “Women marginalised by mental health, disability, or refugee background” project team: Yamamah Agha, Jill Bennett, Ainslee Hooper, Bronwen Iferd, Julia Lappin, Caroline Lenette, Cindy Lui, Apuk Maror, Jacqui McKim, Jane Ussher, Ruth Wells, and Yassmen Yahya. Our thanks and gratitude to the participants who took part in the online workshops described in this paper, your feedback about, and engagement with, the process greatly enriched it. We acknowledge that this research took place on unceded Aboriginal land. We pay our respects to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples as the first custodians of the lands and waters where we live and work.

Notes

In this project we use ‘women’ as an inclusive, collective term. When recruiting participants, we welcomed participation from any individual – e.g. cisgender, transgender, non-binary, or feminine-identifying etc. – who identified with the designation of women.

A similar approach had been utilised by a member of our team for another arts-based project – involving painting, photography, and collage (Kirby Institute 2021).

PV, one of our researcher-facilitators, consulted with an artist-colleague who generously provided advice about the form and duration of these creative exercises (for a detailed overview see Supplement Appendix 1).

Another approach might be to ask participants to make suggestions about what kind of music they would like to listen to as they work.

We trialled calico as a body map base material during a for-fun body mapping workshop on COVID-19 experiences held for our colleagues at the Black Dog Institute in early 2021.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work was supported by the This research was funded by an Australian Research Council Discovery Project Grant. Grant number: DP200100597.

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

ORCID iD

Priya Vaughan https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1016-619X

References

- Black Dog Institute . (2020). What can be done to decrease suicidal behaviour in Australia? A call to action. White Paper. https://www.blackdoginstitute.org.au/suicide-prevention-white-paper/ [Google Scholar]

- Bowen L. (2021). Disability access and digital platforms. The Hastings Center Report, 51(5). 10.1002/hast.1278 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell K. (Ed.), (2021). Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Boydell K. M., Ball J., Curtis J., Jager A. d., Kalucy M., Lappin J., Rosenbaum S., Tewson A., Vaughan P., Ward P. B., Watkins A. (2018). A novel landscape for understanding physical and mental health: Body mapping research with youth experiencing psychosis. Art/Research International, 3(2), 237–261. 10.18432/ari29337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boydell K. M., Bennett J., Dew A., Lappin J., Lenette C., Ussher J., Vaughan P., Wells R. (2020). Women and stigma: A protocol for understanding intersections of experience through body mapping. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5432), 5432. 10.3390/ijerph17155432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jager A., Tewson A., Ludlow B., Boydell K. (2016). Embodied ways of storying the self: A systematic review of body-mapping. Qualitative Social Research, 17(2), 22. 10.17169/fqs-17.2.2526 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dew A., Smith L., Collings S., Dillon Savage I. (2018). Complexity embodied: Using body mapping to understand complex support needs. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 19(2). 10.17169/fqs-19.2.2929 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards G. (2021). Wearable technology and body mapping. In Boydell K. M., Dew A., Collings S., Senior K., Smith L. (Eds.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Fancourt D., Finn S. (2019). What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being? A scoping review. World Health Organization Regional Office for Europe. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastaldo D., Magalhães L., Carrasco C., Davy C. (2012). Body-map storytelling as research: Methodological considerations for telling the stories of undocumented workers through body mapping. Migration as a Social Determinant of Health. http://www.migrationhealth.ca/undocumented-workers-ontario/body-mapping [Google Scholar]

- Hill A. D., Le J. K., McKenny A. F., O’Kane P., Paroutis S., Smith A. (2021). Research in times of crisis: Research methods in the time of COVID-19. Emerald Publishing Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby Institute . (2021). Positively women. Kirby Insitute. December: https://positivelywomenproject.com.au/ [Google Scholar]

- Leese J., Garraway L., Li L., Oelke N., MacLeod M. (2022). Adapting patient and public involvement in patient-oriented methods research: Reflections in a Canadian setting during COVID-19. Health Expectations, 25(2), 477–481. 10.1111/hex.13387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludlow B. (2021). Development of a web-based body mapping application. In Boydell K. M., Dew A., Collings S., Senior K., Smith L. (Eds.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Malecki J. S., Rhodes P., Ussher J., Boydell K. (2022). Jun). 21). The embodiment of childhood abuse and anorexia nervosa: A body mapping study. Health Care for Women International, 1–26. 10.1080/07399332.2022.2087074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesher Shoshan H., Wehrt W. (2022). Understanding “zoom fatigue”: A mixed-method approach. Applied Psychology, 71(3), 827–852. 10.1111/apps.12360 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saad B., George S. A., Bazzi C., Gorski K., Abou-Rass N., Shoukfeh R., Javanbakht A. (2022). Research with refugees and vulnerable populations in a post-COVID world: Challenges and opportunities. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(11), 1322–1326. 10.1016/j.jaac.2022.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Self B. (2021). Conducting interviews during the covid-19 pandemic and beyond. Forum, Qualitative Social Research, 22(3). 10.17169/fqs-22.3.3741 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon H., Graham C., Pothecary N., Rasul F. (2007). Increasing response rates amongst black and minority ethnic and seldom heard groups: A review of literature relevant to the national acutre patients. Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J. (2007). Living with X”: A body mapping journey in the time of HIV and aids. Repssi. [Google Scholar]

- Storen R., Corrigan N. (2020). COVID-19: A chronology of state and territory government announcements (up until 30 june 2020). Research Paper Series 2020-2021. Parliament Of Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Ticho S. (2021). Body mapping and virtual reality. In Boydell K. M., Dew A., Collings S., Senior K., Smith L. (Eds.), Applying body mapping in research: An arts-based method. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Valentine M. (2022). Procrastination and low motivation make productivity difficult. Body-doubling might help. Australian Broadcasting Commission. 2nd August: https://www.abc.net.au/everyday/how-body-doubling-tackles-procrastination/100840316 [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan P., de Jager A., Boydell K. (2021). Body mapping and youth experiencing psychosis. In Liamputtong P. (Ed.), Handbook of social inclusion: Research and practices in health and social sciences. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan P., Lenette C., Boydell K. (2022). ‘This bloody rona!’: Using the digital story completion method and thematic analysis to explore the mental health impacts of COVID-19 in Australia. BMJ Open, 12(1), Article e057393. 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-057393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wherton J., Shaw S., Papoutsi C., Seuren L., Greenhalgh T. (2020). Guidance on the introduction and use of video consultations during COVID-19: Important lessons from qualitative research. BMJ Leader, 4(3), 120–123. 10.1136/leader-2020-000262 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Material for Exploring Embodied Experience via Videoconferencing: A Method for Body Mapping Online by Priya Vaughan, Angela Dew, Akii Ngo and Katherine Boydell in International Journal of Qualitative Methods