Abstract

Background

The common cold is a spontaneously remitting infection of the upper respiratory tract, characterised by a runny nose, nasal congestion, sneezing, cough, malaise, sore throat, and fever (usually < 37.8 ºC). Whilst the common cold is generally not harmful, it is a cause of economic burden due to school and work absenteeism. In the United States, economic loss due to the common cold is estimated at more than USD 40 billion per year, including an estimate of 70 million workdays missed by employees, 189 million school days missed by children, and 126 million workdays missed by parents caring for children with a cold. Additionally, data from Europe show that the total cost per episode may be up to EUR 1102. There is also a large expenditure due to inappropriate antimicrobial prescription. Vaccine development for the common cold has been difficult due to antigenic variability of the common cold viruses; even bacteria can act as infective agents. Uncertainty remains regarding the efficacy and safety of interventions for preventing the common cold in healthy people, thus we performed an update of this Cochrane Review, which was first published in 2011 and updated in 2013 and 2017.

Objectives

To assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of vaccines for preventing the common cold in healthy people.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (April 2022), MEDLINE (1948 to April 2022), Embase (1974 to April 2022), CINAHL (1981 to April 2022), and LILACS (1982 to April 2022). We also searched three trials registers for ongoing studies, and four websites for additional trials (April 2022). We did not impose any language or date restrictions.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of any virus vaccine compared with placebo to prevent the common cold in healthy people.

Data collection and analysis

We used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to assess the initial search results. Four review authors independently performed title and abstract screening to identify potentially relevant studies. We retrieved the full‐text articles for those studies deemed potentially relevant, and the review authors independently screened the full‐text reports for inclusion in the review, recording reasons for exclusion of the excluded studies. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by consulting a third review author when needed. Two review authors independently collected data on a data extraction form, resolving any disagreements by consensus or by involving a third review author. We double‐checked data transferred into Review Manager 5 software. Three review authors independently assessed risk of bias using RoB 1 tool as outlined in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5. We did not conduct a meta‐analysis, and we did not assess publication bias. We used GRADEpro GDT software to assess the certainty of the evidence and to create a summary of findings table.

Main results

We did not identify any new RCTs for inclusion in this update. This review includes one RCT conducted in 1965 with an overall high risk of bias. The RCT included 2307 healthy young men in a military facility, all of whom were included in the analyses, and compared the effect of three adenovirus vaccines (live, inactivated type 4, and inactivated type 4 and 7) against a placebo (injection of physiological saline or gelatin capsule). There were 13 (1.14%) events in 1139 participants in the vaccine group, and 14 (1.19%) events in 1168 participants in the placebo group. Overall, we do not know if there is a difference between the adenovirus vaccine and placebo in reducing the incidence of the common cold (risk ratio 0.95, 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 2.02; very low‐certainty evidence). Furthermore, no difference in adverse events when comparing live vaccine preparation with placebo was reported. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to very low due to unclear risk of bias, indirectness because the population of this study was only young men, and imprecision because confidence intervals were wide and the number of events was low. The included study did not assess vaccine‐related or all‐cause mortality.

Authors' conclusions

This Cochrane Review was based on one study with very low‐certainty evidence, which showed that there may be no difference between the adenovirus vaccine and placebo in reducing the incidence of the common cold. We identified a need for well‐designed, adequately powered RCTs to investigate vaccines for the common cold in healthy people. Future trials on interventions for preventing the common cold should assess a variety of virus vaccines for this condition, and should measure such outcomes as common cold incidence, vaccine safety, and mortality (all‐cause and related to the vaccine).

Keywords: Child; Humans; Male; Adenovirus Vaccines; Adenovirus Vaccines/adverse effects; Common Cold; Common Cold/prevention & control; Incidence; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Systematic Reviews as Topic; Vaccines, Attenuated; Vaccines, Attenuated/adverse effects

Plain language summary

Vaccines for preventing the common cold

Review question

Can vaccines help prevent the common cold?

Background

The common cold is mainly caused by a viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. People with the common cold feel unwell, have a runny nose, nasal congestion, sneezing, cough with or without sore throat, and have slightly elevated temperatures. However, people usually recover when their immune system controls the impact of the viral infection. Treatment for this condition is aimed at relieving symptoms. Globally, the common cold causes widespread illness and large economic loss. In the United States, economic loss due to the common cold is estimated at more than USD 40 billion per year, including millions of workdays and school days missed. In Europe, the total cost per episode may be up to EUR 1102. There is also a large expenditure on inappropriate antimicrobial prescriptions. It has been difficult to manufacture vaccines to prevent the common cold because it is caused by several viruses. The effect of vaccines for preventing the common cold in healthy people is still unknown.

Search date

The evidence is current to 26 April 2022.

Study characteristics

We did not identify any new trials for inclusion in this update. This review includes one previously identified randomised controlled trial (a type of study where participants are randomly assigned to one of two or more treatment groups) performed in 1965. This study involved 2307 young, healthy military men at a training facility in the United States Navy, and evaluated the effects of a live attenuated (weakened) adenovirus vaccine, an inactivated type 4, and an inactivated type 4 and 7 vaccines compared to a placebo (fake vaccine).

Study funding sources

The included trial was funded by a government institution.

Key results

There were no differences in the frequency of occurrence of the common cold between those who received a live attenuated adenovirus vaccine compared to those who received a placebo. There were no differences between groups in adverse events. However, as the trial participants were not representative of the general population and there were flaws in the study design, our confidence in the results is very low. Further research is needed to find out if vaccines can prevent the common cold, as the current evidence does not support the use of the adenovirus vaccine to prevent the common cold in healthy people.

Certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of the evidence as very low due to high risk of bias; because the study population was only young men; and due to the small number of people included in the study and low numbers of colds.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings 1. Virus vaccines compared to placebo for preventing the common cold in healthy people.

| Virus vaccines compared to placebo for preventing the common cold in healthy people | ||||||

| Patient or population: young, healthy men in a military facility Settings: navy training centre Intervention: adenovirus vaccines (live, inactivated type 4, and inactivated type 4 and 7) Comparison: placebo | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No. of participants (studies) | Certainty of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Placebo | Virus vaccines for preventing the common cold | |||||

|

Incidence of the common cold Number of participants with common cold by group Follow‐up: mean 9 weeks |

Study population | RR 0.95 (0.45 to 2.02) | 2307 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | ||

| 12 per 1000 | 11 per 1000 (5 to 24) | |||||

|

Vaccine safety Follow‐up: mean 9 weeks |

The study reported that there were no differences between groups in vaccine‐related adverse events. | 2307 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ Very lowa,b,c | |||

|

Mortality: vaccine related and all cause ‐ not reported Follow‐up: mean 9 weeks |

See comments | The included study did not report this outcome. | ||||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; RR: risk ratio | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High certainty: we are very confident that the true effect lies close to that of the estimate of the effect. Moderate certainty: we are moderately confident in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different. Low certainty: our confidence in the effect estimate is limited: the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect. Very low certainty: we have very little confidence in the effect estimate: the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect. | ||||||

aDowngraded one level due to unclear risk of bias. bDowngraded one level due to indirectness as the study population is only young men. cDowngraded one level due to imprecision as confidence intervals are wide, and the number of events is low.

Background

Description of the condition

Although there is no standard definition for the common cold (see Appendix 1), it is generally defined as a spontaneously remitting infection of the upper respiratory tract (URT), characterised by a runny nose, nasal congestion, and sneezing. Other symptoms associated with the common cold include cough, malaise, sore throat, and fever (usually < 100 ºF/37.8 ºC) (Eccles 2009). A temperature of 100 ºF/37.8 ºC or higher for three to four days is typically associated with influenza and other respiratory diseases (see Appendix 2) (DDCP 2010). Despite the fact that the common cold is not considered to be a deadly disease, bacterial complications can lead to high morbidity and mortality (Giraud‐Gatineau 2020; Veiga 2021).

The common cold is a disease of diverse aetiology (see Appendix 3) (Heikkinen 2003). Premature babies, children, the elderly, and other populations with comorbidities such as chronic lung diseases (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), congenital heart disease, and asthma are more prone to viral infections that cause the common cold, including respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human rhinovirus (HRV), parainfluenza, coronavirus, and adenovirus (non‐polio) (Johnston 2017; Lu 2020; Rubner 2017; Shibata 2018). Additionally, in humans, coronavirus such as the HCoV‐229E, HCoV‐OC43, HCoV‐NL63, and HCoV‐HKU1 strains are responsible for URT infections (URTI) associated with the common cold (Zumla 2016). It has been shown that 1% to 10% of the population is infected with the HCoV‐NL63 coronavirus annually (Szelazek 2017). Even the infectious agent SARS‐CoV‐2 can be associated with the common cold (Zimmermann 2020). The transmission of the common cold occurs through aerosols, direct contact with infected nasal secretions, or fomites (DeGeorge 2019; L'Huillier 2015; Reynolds 2016); the primary factors that contribute to the spread of this disease include poor hand hygiene, overcrowding, and interactions in places such as schools, day‐care centres, and between households (Adler 2018; Alexandrino 2016).

The common cold is one of the most frequent illnesses experienced by humans. Children may experience up to 11 URTIs annually (Lambert 2007; Tang 2019), whilst adults experience an average of two episodes per year (Tomita 2012; Visseaux 2017). For instance, HRV is responsible for 50% to 80% of common colds, and it is an important cause of morbidity, reduced productivity, and inappropriate use of antibiotics (Kardos 2017; Warner 2019). Although there are few studies on the socioeconomic costs of the common cold, and most existing studies are problematic in terms of methodology (e.g. recall bias) for mainly being cross‐sectional studies on self‐reported surveys performed in a small or specific population, the impact on school and work absenteeism caused by common cold and the economic burden it causes cannot be overlooked (Dicpinigaitis 2015; Jaume 2020; Jaume 2021). In the United States, economic loss due to the common cold is estimated at more than USD 40 billion per year, including an estimate of 70 million workdays missed by employees suffering from a cold, 189 million school days missed by children, and 126 million work days missed by parents caring for children with a cold (Kardos 2017), all of which have an impact on productivity (Dicpinigaitis 2015). In Europe, the total cost per episode may be up to EUR 1102, of which 75% are indirect costs (Stjärne 2012). Additionally, there is a large expenditure due to inappropriate antimicrobial prescription and use for URTI (Tsuzuki 2020).

Description of the intervention

There is no specific treatment for the common cold. Treatment is focused on easing the symptoms. Prevention is therefore essential to stop the spread of viruses that cause the common cold. In terms of preventive measures, studies have shown that simple measures such as handwashing and maintaining physical distance are relevant to all respiratory infections, but difficult to apply or enforce because, as time passes, motivation and compliance may decrease (Allan 2014; Jefferson 2020). Consequently, another method of prevention is vaccination. The development of vaccines for the common cold has been challenging because of the aetiological diversity of the disease and the antigenic variability of the common cold viruses (Glanville 2013; To 2017). The case of HRV remains a challenge for the public health and scientific communities due to technical, logistical, and fundamental biological difficulties (Stobart 2017). Unlike several human viruses, HRV vaccine must be able to elicit protective neutralising antibodies to potentially over 150 serologically distinct types spanning three different species (Ren 2017; Stobart 2017). For this reason, it is difficult to develop a vaccine that provides full protection (Stepanova 2019). Despite these challenges, recent attempts using rhinovirus‐derived VP1, a surface protein that is critically involved in the infection of respiratory cells, has demonstrated that with enough exposure and recombinant VP1 as an immunogen, cross‐serotype reactive antibodies can be generated (Edlmayr 2011; McLean 2012). The future of vaccine development for the common cold seems promising, considering that studies on virus genotyping such as HRV genotype are being published more frequently (Luka 2020; Ren 2017), and there is a rapid technological development of vaccines that include micro‐/nanoparticle material and recombinant technologies (Papadopoulos 2017).

Adenovirus is a recognised pathogen of the URT (Biserni 2020). Adenovirus serotype 4 (Ad4) and serotype 7 (Ad7) vaccines were used during immunisation programmes beginning in 1971. Unfortunately, their interruption triggered the re‐emergence of adenovirus‐produced diseases in crowded locations. An example of this reappearance was documented in US military training sites, where Ad4 accounted for 98% of all diagnoses (Russell 2006). The development and deployment of AdV‐4 and AdV‐7 vaccines is essential in controlling AdV‐4‐ and AdV‐7‐related URTI (Collins 2020). Adenoviral vaccines delivered orally have been used for decades to prevent respiratory illnesses. New studies have concluded that these vaccines are safe and have brought about a large immune response in the studied populations. For instance, a study examining the duration of the neutralising antibody response generated from a live oral AdV‐4 and AdV‐7 vaccine showed that, regardless of pre‐vaccination serostatus, participants developed a significant antibody response which persisted for at least six years after vaccination (Collins 2020).

RSV is an important cause of respiratory infection in older adults, and almost all children have been infected with RSV by the age of two; due to incomplete and short‐lived natural immunity, repeated RSV infections occur throughout life (Williams 2020). The development of an RSV vaccine has been difficult due to antigenic variability, especially in proteins F and G. However, a first‐in‐human phase 1 trial has been reported to evaluate the safety and immunogenicity of an experimental RSV vaccine of Ad26.RSV.preF (a replication‐incompetent adenovirus‐26 vector encoding the F protein), which is administered intramuscularly 12 months apart in healthy adults aged ≥ 60 years old (Williams 2020). There have also been concerns of enhanced respiratory disease (ERD) after vaccination with the formalin‐inactivated RSV vaccines in the 1960s, in which patients showed X‐ray evidence of severe pneumonia and bronchiolitis, in addition to immunopotentiation induced by a T helper (Th)‐2 and Th17 T cell responses with the enrolment of T cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils causing inflammation and tissue damage (Rey‐Jurado 2017). Current vaccine candidates, especially those designed for infants and children, whose immune systems are still immature, must therefore be safe and avoid these immunologic features of ERD (Mazur 2018).

One RSV immunisation approach is the development of a vaccine for pregnant women, since it has been demonstrated that RSV‐neutralising antibodies are transferred from the pregnant woman to the foetus through the placenta (Chu 2014). A clinical trial in which healthy pregnant women received either an intramuscular dose of RSV fusion (F) protein nanoparticle vaccine or placebo, showed that during the first 90 days of life, infants with RSV had a significantly lower number of respiratory tract infections (1.5%) compared to the placebo group (2.4%). However, to tag the vaccine as successful in terms of efficacy, its possible benefits with respect to other endpoint events have to be demonstrated (Madhi 2020). Another phase II clinical trial evaluated the tolerability and safety of RSV fusion (F) protein nanoparticle vaccine compared to placebo in 50 healthy third‐trimester pregnant women and their infants (Muňoz 2019). The trial demonstrated that the vaccine was well tolerated with no differences on safety outcomes other than expected short‐term reactogenicity in women who received the active vaccine. In addition, transplacental antibody transfer ranged between 90% and 120% across assays for infants of the vaccinated group of women (Muňoz 2019).

Regarding parainfluenza, there is still no approved vaccine available. However, the intranasal administration of two doses of a live‐attenuated human parainfluenza virus type 3 HPIV3‐cp45 vaccine seems promising, as it has been shown to be well tolerated and immunogenic in seronegative children over six months of age (Karron 2011).

How the intervention might work

Vaccines work by inducing an immune response, such as an antibody response that interferes with a pathogenic invasion and prevents their adherence to epithelial cells through opsonisation, phagocytosis, and other mechanisms (Pichichero 2009; Wooden 2018). A correlate of protection to a pathogen is a measurable sign that a person is immune after vaccination, and can either be absolute or relative (Plotkin 2020). There may also be more than one correlate of protection for a disease, known as 'co‐correlates' (Plotkin 2020). The immune memory is a critical correlate (effector memory for short‐incubation and central memory for long‐incubation diseases), and cell‐mediated immunity can operate as a correlate or co‐correlate of protection against a disease (Plotkin 2010). However, some vaccines only have surrogates for an unknown protective response, which are easy measurements but not functional (Plotkin 2010). For instance, as there is no correlate of protection for the development of HRV vaccines, serum IgA is used as a surrogate marker for studies on all live attenuated HRV vaccines to demonstrate vaccine take (Armah 2016).

Studies suggest that vaccines that mimic natural infection and take into account the structure of pathogens seem to be effective in inducing long‐term protective immunity (Kang 2009). Different types of vaccines against respiratory viruses already exist, but all have been focused on decreasing the incidence of lower respiratory infections. Traditionally inactivated or live attenuated viruses are used. However, there are promising approaches that use micro‐/nanoparticles material and recombinant technologies that produce a broad immunogenic, reproducible, safe, and often self‐adjuvating response (Gomes 2017; Papadopoulos 2017).

Why it is important to do this review

Although the common cold is self‐limiting with symptoms often lasting up to 10 days, it is the most common acute illness in industrialised countries with a very high incidence, presenting several episodes per person a year, as well as being one of the main causes of primary care consultations (DeGeorge 2019; Jaume 2020). Despite being generally mild, the common cold can occur with other respiratory illnesses, which can predispose susceptible individuals to potentially serious complications. Vaccines could therefore be used to reduce the prevalence of the disease around the world and decrease primary care consultations that might saturate healthcare systems.

The socioeconomic burden from the common cold has not been fully studied, and the few studies published in this area mainly have methodological limitations. However, it has been demonstrated that the common cold can lead to work and school absenteeism as well as having an impact on productivity and healthcare costs (Dicpinigaitis 2015; Jaume 2021; Kardos 2017), which could also be reduced by preventing the illness through vaccine use, if effective.

Furthermore, if randomised controlled trials demonstrate that there is an effective and safe vaccine to prevent the common cold, scientists could continue researching this field.

Objectives

To assess the clinical effectiveness and safety of vaccines for preventing the common cold in healthy people.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Randomised controlled trials (RCTs). We did not apply limits with respect to follow‐up periods. In future updates, we will consider at least 60 days of follow‐up. We only included RCTs that reported data about the incidence of the common cold.

Types of participants

Healthy people aged between 6 months and 90 years.

Types of interventions

Any vaccine that prevents the common cold, which protects against RSV, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, or adenovirus (non‐polio), irrespective of dose, schedule, or administration route, versus placebo. We excluded trials on the prevention of influenza A and B because influenza and the common cold are two different diseases (Jefferson 2012). See Appendix 3 for details.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Incidence of the common cold after vaccination, regardless of the causal agent determined by laboratory or clinical examination. In future updates, we will consider the incidence of the common cold as one of the primary outcomes, measured 60 days after the last dose of the vaccine.

Vaccine safety, i.e. adverse events ("any untoward medical occurrence that may present during treatment with a pharmaceutical product but which does not necessarily have a causal relationship with this treatment") and adverse drug reactions ("a response to a drug which is noxious, uninitiated and which occurs at doses normally used in men for prophylaxis, diagnosis, or therapy of disease, or for the modification of physiologic functions") (Nebeker 2004).

Mortality: vaccine related and all cause.

Secondary outcomes

We did not consider any secondary outcomes. In future updates, we will consider mortality as a secondary outcome.

Search methods for identification of studies

Electronic searches

We updated the search strategies in the following databases:

the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL; Issue 4, 2022), which contains the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Specialised Register, searched 26 April 2022, in the Cochrane Library (Appendix 4);

MEDLINE via Ovid (September 2016 to 22 April 2022) (Appendix 5);

Embase via Elsevier (September 2016 to 22 April 2022) (Appendix 6);

CINAHL via EBSCO (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (September 2016 to 22 April 2022) (Appendix 7); and

LILACS via BIREME (Latin American and Caribbean Health Science Information database) (September 2016 to 22 April 2022) (Appendix 8).

We used the Cochrane Highly Sensitive Search Strategy to identify randomised trials in MEDLINE: sensitivity‐ and precision‐maximising version (2008 revision); Ovid format (Lefebvre 2021). We adapted the search strategy to search Embase, CINAHL, and LILACS.

We searched the following trial registries on 26 April 2022:

ISRCTN registry (www.isrctn.com);

ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/); and

World Health Organization International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (WHO ICTRP) (www.who.int/ictrp/search/en/).

We did not restrict the results by language, search dates, or publication status (published, unpublished, in press, or in progress).

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of all relevant trials and identified reviews. We searched the following websites for trials on 29 April 2022:

US Food and Drug Administration (www.fda.gov);

European Medicines Agency (www.emea.europa.eu);

Medicines & Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (www.mhra.gov.uk/index.htm); and

Evidence in Health and Social Care (www.evidence.nhs.uk/).

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

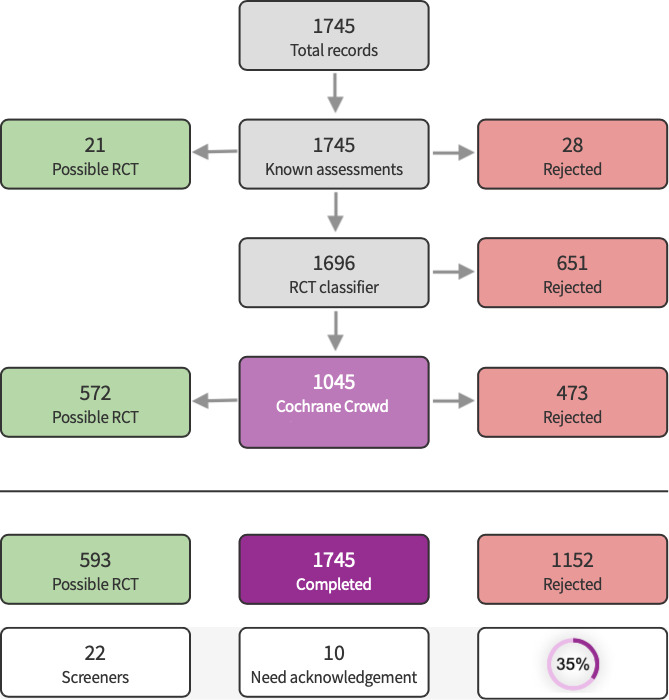

We used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to help assess the search results. Screen4Me comprises three components: known assessments – a service that matches records in the search results to records that have already been screened in Cochrane Crowd and been labelled as an RCT or as non‐RCT; the RCT classifier – a machine learning model that distinguishes RCTs from non‐RCTs; and if appropriate, Cochrane Crowd – Cochrane’s citizen science platform where the Crowd help to identify and describe health evidence. For more information about Screen4Me and the evaluations that have been done, visit the Screen4Me web page on the Cochrane Information Specialist’s portal. More detailed information regarding evaluations of the Screen4Me components can be found in the following publications: Marshall 2018, Noel‐Storr 2020, Noel‐Storr 2021, Thomas 2021.

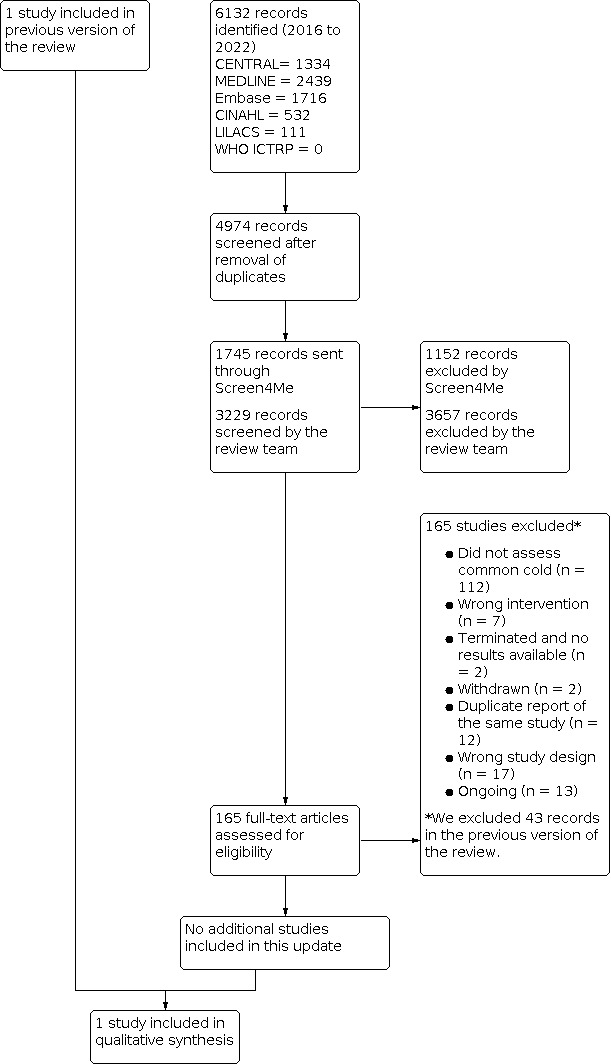

Following Screen4Me assessment, four review authors (CM, DB, MLF, MJMZ) independently screened the titles and abstracts of studies identified as a result of the search for potential relevance. We retrieved the full‐text reports of those studies deemed potentially relevant, and four review authors (MJMZ, CM, DB, MLF) independently screened the full texts to identify studies for inclusion in the review, and identified and recorded the reasons for exclusion of excluded studies. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by consulting a third review author (DSR) when needed. We identified and excluded duplicates and collated multiple reports of the same study so that each study, rather than each report, was the unit of interest in the review. We recorded the selection process in sufficient detail to complete a PRISMA flow diagram (Figure 1) and Characteristics of included studies table (Moher 2009). We imposed no language restrictions.

1.

PRISMA flowchart

Data extraction and management

We used a data collection form for study characteristics and outcome data that had been piloted on at least one study in the review. Two review authors (DSR, CVG) extracted the following study characteristics from the included studies.

Methods: study design, total duration of the study, details of any 'run in' period, number of study centres and location, study setting, withdrawals, and date of the study.

Participants: N, mean age, age range, gender, severity of the condition, diagnostic criteria, baseline lung function, smoking history, inclusion criteria, and exclusion criteria.

Interventions: intervention, comparison, concomitant medications, and excluded medications.

Outcomes: primary and secondary outcomes specified and collected, and time points reported.

Notes: funding for the trial, and notable conflicts of interest of trial authors.

Two review authors (DSR, CVG) independently extracted outcome data from the included studies. We described in the Characteristics of included studies table if outcome data were not reported in a usable way. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by involving a third review author (RH). One review author (DSR) transferred data into the Review Manager 5 file (Review Manager 2020). We double‐checked that the data had been entered correctly by comparing the data presented in the systematic review with the study report. A second review author (MJMZ) spot‐checked study characteristics for accuracy against the trial report.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Three review authors (DSR, CVG, RH) independently assessed risk of bias of the included studies using Cochrane's risk of bias tool RoB 1, according to the criteria in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022). Any disagreements were resolved by discussion or by involving another review author (MJMZ). We assessed the risk of bias based on the following domains.

Random sequence generation.

Allocation concealment.

Blinding of participants and personnel.

Blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data.

Selective outcome reporting.

Other bias.

We graded each potential source of bias as low, high, or unclear and provided quotes from the study report together with a justification for our judgement in the risk of bias table. Where necessary, we considered blinding separately for different key outcomes.

Measures of treatment effect

We calculated the risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for incidence of the common cold. We added outcome data for the included study into a data table in Review Manager 5 to calculate treatment effects (Review Manager 2020). We used RR for dichotomous outcomes.

Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis was the participant. We collected and analysed a single measurement for each outcome from each participant.

Dealing with missing data

We had planned to contact investigators or study sponsors to verify key study characteristics and to obtain missing numerical outcome data where possible (e.g. when a study was identified only as an abstract); however, this was not needed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We had planned to use the I² statistic to measure heterogeneity amongst trials in each analysis; however, we did not conduct a meta‐analysis because only one trial satisfied the inclusion criteria.

Assessment of reporting biases

We did not assess publication bias using a funnel plot because we included only one trial. In future updates, we will attempt to assess whether the review is subject to publication bias by using a funnel plot if 10 or more trials are included.

Data synthesis

We carried out statistical analysis using Review Manager 5 software (Review Manager 2020). In future updates, we will summarise findings using a fixed‐effect model following the guidance in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022).

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We did not perform a subgroup analysis. In subsequent updates of this review, when sufficient data are available, we will carry out the following subgroup analyses:

children and adults;

country of study; and

different responses in relation to different viral agents.

We will explore sources of heterogeneity in the assessment of the primary outcomes by subgroup analyses. Additionally, due to the limited number of included studies, we do not plan on performing a meta‐regression in the future.

Sensitivity analysis

We did not perform a sensitivity analysis. In future updates, we plan to conduct sensitivity analyses comparing the results using all trials as follows.

Trials with high methodological quality (studies classified as having a 'low risk of bias' versus those identified as having a 'high risk of bias') (Higgins 2022).

Trials that performed intention‐to‐treat versus per‐protocol analyses.

Parallel randomised clinical trials versus cluster‐randomised clinical trials.

We will also evaluate the risk of attrition bias, as estimated by the percentage of participants lost. We will exclude trials with a total attrition of more than 30% or where differences between the groups exceeded 10%, or both, from meta‐analysis, but will include these studies in the review.

Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We created a summary of findings table using the following outcomes: incidence of the common cold, vaccine safety, and mortality (all cause and vaccine related) (Table 1). We used the five GRADE considerations (study limitations, consistency of effect, imprecision, indirectness, and publication bias) to assess the certainty of the evidence as it relates to the study that contributed data (Atkins 2004). We used the methods and recommendations described in Section 8.5 and Chapter 12 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (Higgins 2022), employing GRADEpro GDT software (GRADEpro GDT). We justified all decisions to down‐ or upgrade the certainty of the evidence using footnotes, and made comments to aid the reader's understanding of the review where necessary.

Results

Description of studies

See Characteristics of included studies, Characteristics of excluded studies, and Characteristics of ongoing studies tables.

Results of the search

In the current update we identified a total of 4974 search results (Figure 1). We used Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow to help identify potential reports of randomised trials. The results of the Screen4Me assessment process are shown in Figure 2. We assessed 6132 records and excluded 3657 records based on title and abstract screening. We assessed the full texts of 165 studies, and did not include any new studies in this update. We included only one trial in the review (Griffin 1970).

2.

Screen4Me summary diagram.

Included studies

We included one RCT involving 2307 healthy young men (Griffin 1970). Griffin 1970 compared the effect of three adenovirus vaccines (live, inactivated type 4, and inactivated type 4 and 7) to placebo (an injection of physiological saline for the parenterally administered vaccines, and an identical‐appearing inert gelatin capsule for the orally administered vaccines). See Characteristics of included studies.

Excluded studies

We excluded 43 studies in the previous publication of this review (Belshe 1982; Belshe 1992; Belshe 2004a; Belshe 2004b; Clements 1991; DeVincenzo 2010; Doggett 1963; Dudding 1972; Falsey 1996; Falsey 2008; Fulginiti 1969; Glenn 2016; Gomez 2009; Gonzalez 2000; Greenberg 2005; Hamory 1975; Karron 1995a; Karron 1995b; Karron 1997; Karron 2003; Karron 2005; Karron 2015; Kumpu 2015; Langley 2009; Lee 2001; Lee 2004; Lyons 2008; Madhi 2006; Munoz 2003; Murphy 1994; Paradiso 1994; Piedra 1995; Pierce 1968; Power 2001; Ritchie 1958; Simoes 2001; Tang 2008; Top 1971; Tristram 1993; Watt 1990; Welliver 1994; Wilson 1960; Wright 1976).

We excluded 109 new studies in this update (Abarca 2020; Ahmad 2022; Aliprantis 2018; Aliprantis 2020; Ascough 2019; August 2017; Beran 2018; Bourne 1946; Cicconi 2020; Cunningham 2019; DeVincenzo 2019; Domachowske 2017; Domachowske 2018; Esposito 2019; EUCTR2008‐001714‐24‐GB; EUCTR2012‐001107‐20‐GB; EUCTR2013‐004036‐30‐GB; EUCTR2014‐005041‐41‐GB; EUCTR2015‐004296‐77‐GB; EUCTR2016‐000117‐76‐ES; EUCTR2016‐000117‐76‐PL; EUCTR2016‐001135‐12‐FR; EUCTR2016‐002733‐30‐ES; EUCTR2018‐001340‐62‐FI; Falloon 2017a; Falloon 2017b; Fries 2019; Israel 2016; Karppinen 2019; Karron 2020a; Karron 2020b; Langley 2016; Langley 2017; Langley 2018; Leroux‐Roels 2019; Madhi 2020; McFarland 2018; McFarland 2020a; McFarland 2020b; Munoz 2019; NCT00139347; NCT00308412; NCT00345670; NCT00345956; NCT00363545; NCT00366782; NCT00383903; NCT00420316; NCT00496821; NCT00641017; NCT00686075; NCT00767416; NCT01021397; NCT01139437; NCT01254175; NCT01290419; NCT01475305; NCT01709019; NCT01852266; NCT01905215; NCT02115815; NCT02266628; NCT02296463; NCT02419391; NCT02440035; NCT02472548; NCT02479750; NCT02491463; NCT02561871; NCT02593071; NCT02601612; NCT02624947; NCT02794870; NCT02830932; NCT02864628; NCT02873286; NCT02890381; NCT02926430; NCT02952339; NCT03026348; NCT03049488; NCT03191383; NCT03303625; NCT03334695; NCT03392389; NCT03403348; NCT03473002; NCT03572062; NCT03674177; NCT03814590; NCT04071158; NCT04086472; NCT04752644; NTR7173; Philpott 2016; Philpott 2017; Ruckwardt 2021; Sadoff 2021a; Sadoff 2021b; Samy 2020; Scaggs Huang 2021; Schwarz 2019; Shakib 2019; Shaw 2019; Swamy 2019; Van Der Plas 2020; Verdijk 2020; Williams 2020; Yu 2020). We identified 13 ongoing studies (NCT01893554; NCT03387137; NCT03422237; NCT03596801; NCT03916185; NCT04032093; NCT04126213; NCT04138056; NCT04681833; NCT04732871; NCT04980391; NCT05127434; NCT05238025). We contacted the authors of the ongoing trials; however, no preliminary results have been shared with us.

Risk of bias in included studies

Griffin 1970 had overall low methodological quality. See Figure 3 and Figure 4.

3.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages.

4.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for the included study.

Allocation

We assessed Griffin 1970 as at unclear risk of bias for random sequence generation and allocation concealment as inadequate information prevented a judgement for this domain.

Blinding

We assessed Griffin 1970 as at low risk of bias for blinding of participants and personnel and blinding of outcome assessment.

Incomplete outcome data

We assessed Griffin 1970 as at low risk of attrition bias as there were no losses.

Selective reporting

We assessed Griffin 1970 as at unclear risk of reporting bias. The study protocol was not available, but it was clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. However, some of the outcomes were described in a narrative fashion and did not specify incidence for each group.

Other potential sources of bias

We assessed Griffin 1970 as at unclear risk of other bias. The baseline characteristics of participants were not described, and there was no detailed information relating to assessment of selection bias, preventing an evaluation of whether both groups were comparable.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1

Our results are based on one RCT with 2307 healthy people, which we assessed as providing very low‐certainty evidence (Griffin 1970). See Table 1.

Primary outcomes

1. Incidence of the common cold

We do not know if there is a difference between the adenovirus vaccine and placebo in reducing the incidence of the common cold (risk ratio 0.95, 95% confidence interval 0.45 to 2.02; 1 RCT, 2307 participants, 27 events; Analysis 1.1) (Griffin 1970). We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to very low due to unclear risk of bias; indirectness because the population of this study was only young and healthy men; and imprecision because confidence intervals were wide, and the number of events was low.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1: Adenovirus vaccines versus placebo, Outcome 1: Incidence of the common cold

2. Vaccine safety

Griffin 1970 reported that there were no differences in adverse events between live vaccine preparation and placebo. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence to very low due to unclear risk of bias; indirectness because the population of this study was only young men; and imprecision because confidence intervals were wide, and the number of events was low.

3. Mortality

Griffin 1970 did not assess either vaccine‐related or all‐cause mortality.

Discussion

Summary of main results

One RCT met our inclusion criteria (Griffin 1970). The incidence of the common cold in Griffin 1970 was very low, probably due to the fact that only cases resulting in admission to the medical dispensary or hospital were included. Furthermore, the trial authors stated that more common cold cases were diagnosed incidentally when people were hospitalised for other causes, therefore mild cases of illness were not included.

Critical appraisal of Griffin 1970 did not support the use of any vaccine for preventing the common cold in healthy people. We did not find significant differences in the incidence of the common cold in people treated with adenovirus vaccines compared with placebo. Griffin 1970 did not evaluate main clinical outcomes such as mortality related to the vaccine. No differences in adverse events were reported. The relative effect of any of the vaccines for viruses that cause the common cold remains unclear.

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

The included trial did not detect statistically significant differences between treatment groups (Griffin 1970).

When considering such neutral results, it is important to keep in mind that 'absence of evidence' is not 'evidence of absence' (Alderson 2004; Altman 1995; Westerterp 2020). The fact that this review did not detect any differences between intervention groups does not imply that placebo and adenovirus vaccine have the same effect on preventing the common cold.

The first possible explanation for not detecting any differences between intervention groups could be the lack of an appropriate sample size (Green 2002; Schulz 1995), which resulted in small differences in the incidence of the common cold and few events in the comparison groups. A remarkable paper from Freiman 1978 suggested that "many of the therapies labelled as 'no different from control' in trials using inadequate samples, have not received a fair test" and that "concern for the probability of missing an important therapeutic improvement because of small sample sizes deserves more attention in the planning of clinical trials". Moreover, most trials with negative results usually have insufficiently large sample sizes to detect at least 50% relative difference (Moher 1998; Sully 2014). It has also been suggested that the most important therapies adopted in clinical practice have only shown modest benefits (Kirby 2002).

Certainty of the evidence

The results for the primary outcomes of incidence of the common cold and vaccine safety were based on very low‐certainty evidence due to imprecision because confidence intervals were wide and the number of events was low; indirectness (the RCT considered in our review included only young, healthy men); and methodological limitations. Random sequence generation, allocation, sample size, and baseline characteristics of participants were not reported. Adverse events were not reported individually for each group. Overall, due to a lack of evidence, the balance between the benefits and harms of cold vaccines is uncertain.

Potential biases in the review process

Whilst performing a systematic review, several biases can emerge, such as 'significance‐chasing' biases (Ioannidis 2010). This group of biases include publication bias, selective outcome reporting bias, selective analysis reporting bias, and fabrication bias (Ioannidis 2010). Publication bias represents a major threat to the validity of systematic reviews, particularly those reviews that include small trials. However, in this systematic review we performed an exhaustive search and attempted to locate all studies to include new RCTs. The current evidence does not evaluate common cold outcomes.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

Most studies on vaccines for the common cold evaluate respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccines, followed by studies on adenovirus vaccines; only a few published studies evaluate human rhinovirus (HRV) and parainfluenza vaccines. In addition, these studies mainly aim to reduce lower respiratory tract infections or focus on immunological outcomes. For instance, Buchholz 2018 and McFarland 2020b are two RCTs of live‐attenuated RSV vaccines that focus on upper respiratory tract infections; however, these studies assessed immunological outcomes such as vaccine shedding, serum RSV antibodies, anti‐RSV F immunoglobulin G, surveillance period, adverse events, and reactogenicity. There is no general consensus on the outcomes to be considered in evaluating the efficacy of a vaccine. In this review we assessed the following outcomes: incidence of common cold after vaccination, vaccine safety, and mortality (all cause and vaccine related), which were not considered in most RCTs assessed for inclusion by full text. We focused on these outcomes due to the impact that the common cold has at the population level, with a high estimated economic loss due to missed working days (Kardos 2017; Tsuzuki 2020). Other systematic reviews on vaccines for preventing upper respiratory tract infection have assessed outcomes similar to those included in this review (Hao 2015; Thomas 2013).

We excluded 11 non‐RCTs that evaluated vaccines for upper respiratory tract infections (Belshe 1982; Clements 1991; Doggett 1963; Dudding 1972; Fulginiti 1969; Hamory 1975; Karron 1997; Ritchie 1958; Watt 1990; Wilson 1960; Wright 1976). Only one study evaluated the incidence of the common cold (Ritchie 1958), whilst the others focused on immunologic outcomes. The study conducted by Ritchie 1958 prepared an "autologous vaccine" developed from the nasal secretions of 125 healthy volunteers, who were then inoculated with this product, whilst 75 healthy volunteers served as a control. The results showed a lower incidence of common cold in the vaccine group than in the control group. This study was not an RCT and was thus excluded from our review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

This Cochrane Review update found very limited evidence on the effects of vaccines for the common cold in healthy people. We included only one randomised controlled trial, which did not report differences between comparison groups. Our findings were based on only one trial with very low‐certainty evidence with an unclear risk of bias, indirectness, and imprecision. Griffin 1970 involved 2307 participants and assessed adenovirus vaccines compared with placebo, and showed that there may be no difference between the adenovirus vaccine and placebo in reducing the incidence of the common cold.

Implications for research.

This 2022 update highlights the need for well‐designed, high‐quality randomised clinical trials to assess the effectiveness and safety of vaccines to prevent the common cold in healthy people. Future trials should include outcomes such as common cold incidence, vaccine safety, mortality, and adverse events related to vaccine administration. Inert placebo use would also be beneficial to avoid dampening adverse events following immunisation. Future trials should be conducted by independent researchers and reported according to CONSORT guidelines (Moher 2012; PCORI 2012), and should adhere to the Foundation of Patient‐Centered Outcomes Research recommendations (Gabriel 2012).

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 26 April 2022 | New search has been performed | We did not identify any new trials for inclusion in this update. We excluded 109 new studies and identified 13 ongoing studies. We recruited two new authors to update this review, and one of the previous review authors did not take part in this update. |

| 26 April 2022 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | Our conclusions remain unchanged. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 3, 2000 Review first published: Issue 6, 2013

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 2 September 2016 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We recruited three new authors to update this review. |

| 2 September 2016 | New search has been performed | We updated our searches and excluded three new trials (Glenn 2016; Karron 2015; Kumpu 2015). |

| 22 January 2015 | New search has been performed | Searches conducted. |

| 16 March 2011 | New citation required and major changes | Protocol taken over by a new team of review authors. |

| 26 February 2009 | Amended | Protocol withdrawn (Issue 3, 2009). |

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Tom Jefferson and David Tyrell, who co‐authored the first published version of this review; Anne Lyddiatt, Gulam Khandaker, Lisa Jackson, Mark Griffin, and Meenu Singh for commenting on the draft protocol; and Theresa Wrangham, John Jordan, Viviana Rodriguez, and Meenu Singh for commenting on the first draft review. The authors wish to express their thanks to Liz Dooley, Managing Editor of the Cochrane Acute Respiratory Infections Group, for her comments, which improved the quality of this review.

For this 2022 update, we would like to acknowledge and thank the following people for their help in assessing the search results for this review via Cochrane’s Screen4Me workflow: Nikolaos Sideris, Anna Noel‐Storr, Shammas Mohammed, Sarah Moore, Yuan Chi, Mohammad Aloulou, Ana‐Marija Ljubenković, Vighnesh Devulapalli, Jens Bredbjerg Brock Thorsen, and Mykhailo Havrylets.

The following people conducted the editorial process for this 2022 update.

Sign‐off Editors (final editorial decision): Mark Jones (Bond University, Australia); Mieke van Driel (The University of Queensland, Australia).

Managing Editors (provided editorial guidance to authors, edited the review, selected peer reviewers, and collated peer‐reviewer comments): Liz Dooley (Bond University, Australia); Fiona Russell (Bond University, Australia).

Contact Editor (provided comments and recommended an editorial decision): Meenu Singh (Post Graduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India).

Statistical Editor (provided comments): Menelaos Konstantinidis (University of Toronto, Canada)

Copy Editor (copy‐editing and production): Lisa Winer, Cochrane Copy Edit Support

Peer reviewers (provided comments and recommended an editorial decision):

Clinical/content review: Roger E Thomas (University of Calgary, Canada).

Consumer review: Theresa Wrangham (USA).

Methods review: Rachel Richardson (Associate Editor, Cochrane, UK).

Search review: Justin Clark (Institute for Evidence‐Based Healthcare, Bond University, Australia).

One peer reviewer preferred to remain anonymous.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Glossary

| Term | Definition | Reference |

| Common cold | The common cold is a self‐limiting acute upper respiratory tract infection characterised by rhinorrhoea, nasal congestion, sneezing, cough, sore throat, fever, and malaise. | Heikkinen 2003 |

| Vaccination | Inoculation with a vaccine, i.e. a preparation of microbial antigen often combined with adjuvants administered to an individual in order to induce protective immunity against microbial infections. The antigen may be in the form of live, avirulent micro‐organisms or purified macromolecular components of micro‐organisms. | Abbas 2001 |

| Immune system | The collection of cells, tissues, and molecules that mediate resistance to infections | Abbas 2001 |

| Cell‐mediated immunity | The arm of the adaptative immune response whose role is to combat infections by intracellular microbes. This type of immunity is mediated by T lymphocytes. | Abbas 2001 |

| Antigenical variability | Microbes have evolved mechanisms to evade immunity. Many bacteria and viruses mutate their antigenic surface molecules and can no longer be recognised by antibodies produced in response to previous infection. | Abbas 2001 |

| Serotypes | An antigenically distinct subset of a species of an infectious organism that is distinguished from other subsets by serologic (i.e. serum antibody) tests. Humoral immune response to one serotype of microbes, e.g. influenza virus, may not be protective against another serotypes. | Abbas 2001 |

| Immune responses | Once a foreign organism has been recognised, the immune system enlists the participation of a variety of cells and molecules to mount an appropriate response in order to eliminate or neutralise the organism. | Goldsby 2000 |

| Antigenic molecules | Any molecule capable of being recognised by an antibody or T‐cell receptor. Any substance that elicits an immune response | Goldsby 2000; Roitt 2004 |

| Allergens | An antigen that elicits an immediate hypersensitivity (allergic) reaction. Allergens are proteins, or chemicals bound to proteins, that induce immunoglobulin E antibody production in atopic individuals. | Abbas 2001 |

| Immunopotentiation | Non‐specific immunostimulation given by various agents that can stimulate the immune response. It is believed that the mechanism of action is through some modification of local cytokines or growth of innate immune mechanisms. An increase in the functional capacity of the immune response |

Gorczynski 2007 |

| Opsonisation | The process by which particulate antigens are rendered more susceptible to phagocytosis The process of attaching opsonins, such as immunoglobulin G or complement fragments, to microbial surfaces to target microbes for phagocytosis |

Abbas 2001; Goldsby 2000 |

| Phagocytosis | Macrophages are capable of ingesting and digesting exogenous antigens, such as whole micro‐organisms and insoluble particles, and endogenous matter, such as injured or dead host cells, cellular debris, and activated clotting factors. The process by which certain cells of the innate immune system, including macrophages and neutrophils, engulf large particles (> 0.5‐micrometre diameter), such as intact microbes. The cell surrounds the particle by a cytoskeleton‐dependent process, leading to formation of an intracellular vesicle called a phagosome, which contains the ingested particle. |

Abbas 2001; Goldsby 2000 |

Appendix 2. Differences between clinical characteristics of the common cold and influenza

| Feature | Common cold | Influenza | References |

| Aetiological agent | > 100 viral strains; rhinovirus most common | 3 strains of influenza virus: influenza A, B, C |

Czubak 2021; DDCP 2010; Gwaltney 1967; Gwaltney 2000; Heikkinen 2003; Roxas 2007; Thompson 2003 |

| Site of infection | Upper respiratory tract | Entire respiratory system | |

| Symptom onset | Gradual: 1 to 3 days | Sudden: within a few hours | |

| Fever, chills | Occasional, low grade (< 100 ºF) | Fever is usually present with the flu (up to 80% of all flu cases). A temperature of 100 ºF or higher for 3 to 4 days is typically associated with the flu. | |

| Headache | Frequent, usually mild | Characteristic, more severe | |

| General aches, pains | Mild, if any | Characteristic, often severe and affecting the entire body | |

| Cough, chest congestion | Mild to moderate, with hacking cough | Common, may become severe | |

| Sore throat | Common, usually mild | Sometimes present | |

| Runny, stuffy nose | Very common, accompanied by bouts of sneezing | Sometimes present | |

| Fatigue, weakness | Mild, if any | Usual, may be severe and last 2 to 3 weeks | |

| Extreme exhaustion | Never | Frequent, usually in early stages of illness | |

| Season | Year around, peaks in winter months | Most cases between November and February | |

| Antibiotics helpful | No, unless secondary bacterial infection develops | No, unless secondary bacterial infection develops |

Appendix 3. Viral causes of the common cold

| Virus | Estimated annual proportion of cases | References |

| Rhinoviruses | 30% to 50%; during autumn 80%. Once considered to be limited to the upper airway, now recognised as an important cause of lower respiratory infections | Arruda 1997; Gwaltney 1985; Heikkinen 2003; Lemanske 2005; Mäkelä 1998; Monto 1993; Regamey 2008 |

| Coronaviruses | 7% to 18% in adults with upper respiratory infections. Responsible for 2.1% of hospital admissions for acute respiratory tract infections in all age groups | Larson 1980; Lau 2006; Mäkelä 1998; Nicholson 1997 |

| Influenza viruses | 5% to 15% | Heikkinen 2003 |

| Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) | In low‐income countries, 15% to 20% In hospital the proportion of children aged between birth and 5 months with RSV acute lower respiratory tract infections ranged between 9% and 87%. Amongst children up to at least 5 years of age reported with RSV, on average 39% (range 20% to 62%) were < 6 months old; on average 24% of cases (range 14% to 38%) were children aged 6 to 11 months, thus an average of 63% of children were under 1 year of age. On average 20% (range 13% to 29%) of children were between 1 and 2 years of age. RSV accounts for approximately 10,000 deaths annually in people over the age of 65 years in the USA. RSV in adults, 5% infection annually |

Berman 1991; Falsey 2005; Thompson 2003 |

| Parainfluenza viruses | Acute respiratory infections cause 3% to 18% of all admissions to paediatric hospitals; however, this might vary at different times of the year. Parainfluenza viruses account for 17% of hospitalised illness‐associated virus isolation. In low‐income countries, 7% to 10% Parainfluenza viruses cause 50% to 74.2% of croup cases. |

Berman 1991; Denny 1983; Henrickson 2003 |

| Adenoviruses | In low‐income countries, 2% to 4% | Berman 1991 |

| Metapneumovirus | 10% short epidemic | Esper 2003; Kahn 2003; Nissen 2002; Risnes 2005 |

| Unknown | 20% to 30% | Mäkelä 1998; Monto 1993 |

Appendix 4. CENTRAL search strategy

#1 mh "Common Cold"

#2 "common cold*":ti,ab

#3 "coryza":ti,ab

#4 (acute near/5 ("upper respiratory infection*" or "upper respiratory tract infection*" or urti or uri)):ti,ab

#5 mh "Picornaviridae Infections"

#6 mh Rhinovirus

#7 rhinovir*

#8 "hrv":ti,ab

#9 mh "Paramyxoviridae Infections"

#10 mh "parainfluenza virus 1, human" or mh "parainfluenza virus 3, human"

#11 mh "parainfluenza virus 2, human" or mh "parainfluenza virus 4, human"

#12 "parainfluenza*":ti,ab

#13 mh coronavirus or mh "coronavirus 229e, human" or mh "coronavirus oc43, human"

#14 mh "Coronavirus Infections"

#15 coronavir*

#16 mh adenoviridae or mh "adenoviruses, human"

#17 mh adenoviridae or mh "adenoviruses, human"

#18 adenovir*

#19 mh "respiratory syncytial viruses" or mh "respiratory syncytial virus, human"

#20 mh "Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections"

#21 ("respiratory syncytial virus*" or rsv):ti,ab

#22 #1 or #2 or #3 or #4 or #5 or #6 or #7 or #8 or #9 or #10 or #11 or #12 or #13 or #14 or #15 or #16 or #17 or #18 or #19 or #20 or #21

#23 mh Vaccines

#24 mh Vaccination

#25 (vaccin* or inocul* or immuni*):ti,ab

#26 #23 or #24 or #25

#27 #22 and #26 with Cochrane Library publication date Between Sep 2016 and April 2022

Appendix 5. MEDLINE (Ovid) search strategy

1 Common Cold/

2 common cold*.tw.

3 coryza.tw.

4 (acute adj5 (upper respiratory infection* or upper respiratory tract infection* or urti or uri)).tw.

5 Picornaviridae Infections/

6 Rhinovirus/

7 rhinovir*.tw.

8 hrv.tw.

9 Paramyxoviridae Infections/

10 parainfluenza virus 1, human/ or parainfluenza virus 3, human/

11 parainfluenza virus 2, human/ or parainfluenza virus 4, human/

12 parainfluenza*.tw.

13 coronavirus/ or coronavirus 229e, human/ or coronavirus oc43, human/

14 Coronavirus Infections/

15 coronavir*.tw.

16 exp adenoviridae/ or adenoviruses, human/

17 Adenovirus Infections, Human/

18 adenovir*.tw.

19 respiratory syncytial viruses/ or respiratory syncytial virus, human/

20 Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections/

21 (respiratory syncytial virus* or rsv).tw.

22 or/1‐21

23 exp Vaccines/

24 exp Vaccination/

25 (vaccin* or inocul* or immuni*).tw.

26 or/23‐25 (724637)

27 randomized controlled trial.pt.

28 controlled clinical trial.pt.

29 randomi?ed.ab.

30 placebo.ab.

31 drug therapy.fs.

32 randomly.ab.

33 trial.ab.

34 groups.ab.

35 27 or 28 or 29 or 30 or 31 or 32 or 33 or 34

36 exp animals/ not humans.sh.

37 35 not 36

38 22 and 26 and 37

39 limit 38 to dt=20160901‐20220426

Appendix 6. Embase (Elsevier) search strategy

#28 #27 AND (2016:py OR 2017:py OR 2018:py OR 2019:py OR 2020:py OR 2021:py OR 2022:py)

#27 #23 AND #26

#26 #24 OR #25

#25 random*:ab,ti OR placebo*:ab,ti OR factorial*:ab,ti OR crossover*:ab,ti OR 'cross over':ab,ti OR 'cross‐over':ab,ti OR volunteer*:ab,ti OR assign*:ab,ti OR allocat*:ab,ti OR (((singl* OR doubl*) NEAR/1 blind*):ab,ti)

#24 'randomized controlled trial'/exp OR 'single blind procedure'/exp OR 'double blind procedure'/exp OR 'crossover procedure'/exp

#23 #18 AND #22

#22 #19 OR #20 OR #21

#21 'vaccination'/de

#20 vaccin*:ab,ti OR immuni*:ab,ti OR inocul*:ab,ti

#19 'vaccine'/exp

#18 #1 OR #2 OR #3 OR #4 OR #5 OR #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 OR #13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17

#17 'respiratory syncytial virus':ab,ti OR 'respiratory syncytial viruses':ab,ti OR rsv:ab,ti

#16 'respiratory syncytial pneumovirus'/de OR 'respiratory syncytial virus infection'/de

#15 adenovir*:ab,ti

#14 'adenovirus'/exp OR 'human adenovirus infection'/de

#13 coronavir*:ab,ti

#12 'coronavirus'/de OR 'coronavirus infection'/de

#11 parainfluenza*:ab,ti

#10 'parainfluenza virus 1'/de OR 'parainfluenza virus 2'/de OR 'parainfluenza virus 3'/de OR 'parainfluenza virus4'/exp

#9 'parainfluenza virus'/exp

#8 'paramyxovirus infection'/de

#7 rhinovir*:ab,ti OR hrv:ab,ti

#6 'rhinovirus infection'/de OR 'human rhinovirus'/de

#5 coryza:ab,ti

#4 'acute upper respiratory infection':ab,ti OR 'acute upper respiratory infections':ab,ti OR 'acute upper respiratory tract infection':ab,ti OR 'acute upper respiratory tract infections':ab,ti OR ((acute NEAR/5 (urti OR uri)):ab,ti)

#3 'viral upper respiratory tract infection'/de OR 'upper respiratory tract infection'/de

#2 'common cold':ab,ti OR 'common colds':ab,ti

#1 'common cold'/de OR 'common cold symptom'/de

Appendix 7. CINAHL (EBSCO) search strategy

S34 S23 AND S33 Limiters ‐ Published Date: 20160101‐20220426

S33 S24 OR S25 OR S26 OR S27 OR S28 OR S29 OR S30 OR S31 OR S32

S32 (MH "Quantitative Studies")

S31 TI placebo* or AB placebo*

S30 (MH "Placebos")

S29 TI random* or AB random*

S28 TI (singl* mask* or doubl* mask* or tripl* mask* or trebl* mask*) or AB (singl* mask* or doubl* mask* or tripl* mask* or trebl* mask*)

S27 TI (singl* blind* or doubl* blind* or trebl* blind* or tripl* blind*) or AB (singl* blind* or doubl* blind* or trebl* blind* or tripl* blind*)

S26 TI clinic* w1 trial* or AB clinic* w1 trial*

S25 PT clinical trial

S24 (MH "Clinical Trials+")

S23 S18 AND S22

S22 S19 OR S20 OR S21

S21 TI (vaccin* or immuni* or inocula*) or AB (vaccin* or immuni* or inocula*)

S20 (MH "Immunization")

S19 (MH "Vaccines+")

S18 S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 OR S5 OR S6 OR S7 OR S8 OR S9 OR S10 OR S11 OR S12 OR S13 OR S14 OR S15 OR S16 OR S17

S17 TI (respiratory syncytial virus* or rsv ) or AB (respiratory syncytial virus* or rsv)

S16 (MH "Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections")

S15 (MH "Respiratory Syncytial Viruses")

S14 TI adenovir* or AB adenovir*

S13 TI coronavir* or AB coronavir*

S12 (MH "Coronavirus+")

S11 (MH "Coronavirus Infections")

S10 TI parainfluenza* or AB parainfluenza*

S9 (MH "Paramyxovirus Infections")

S8 (MH "Paramyxoviruses")

S7 TI hrv or AB hrv

S6 TI rhinovir* or AB rhinovir*

S5 (MH "Picornavirus Infections")

S4 TI (upper respiratory tract infection* or upper respiratory infection*) or AB (upper respiratory tract infection* or upper respiratory infection*)

S3 TI coryza or AB coryza

S2 TI common cold* or AB common cold*

S1 (MH "Common Cold")

Appendix 8. LILACS (BIREME) search strategy

((mh:"Common Cold" OR "common cold" OR "common colds" OR coryza OR "Resfriado Común" OR "Resfriado Comum" OR "Coriza Aguda" OR "Upper Respiratory Tract Infections" OR "upper respiratory tract infection" OR "Infecciones del Tracto Respiratorio Superior" OR "Infecciones de las Vías Respiratorias Superiores" OR "Infecções do Trato Respiratório Superior" OR "Infecções das Vias Respiratórias Superiores" OR "Infecções das Vias Aéreas Superiores" OR "Infecções do Sistema Respiratório Superior" OR mh:"Picornaviridae Infections" OR "Infecciones por Picornaviridae" OR "Infecções por Picornaviridae" OR "Picornavirus Infections" OR mh:rhinovirus OR rhinovir* OR "Virus de la Coriza" OR "Virus del Resfriado Común" OR "Vírus da Coriza" OR "Vírus do Resfriado Comum" OR hrv OR mh:"Paramyxoviridae Infections" OR parainfluenza* OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 1, Human" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 2, Human" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 3, Human" OR mh:"Parainfluenza Virus 4, Human" OR mh:"Coronavirus Infections" OR coronavir* OR mh:coronavirus OR mh:"Coronavirus 229E, Human" OR mh:"Coronavirus OC43, Human" OR mh:"Coronavirus NL63, Human" OR mh:adenoviridae OR mh:"Adenoviruses, Human" OR mh:"Adenovirus Infections, Human" OR adenovir* OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Viruses" OR "Virus Sincitiales Respiratorios" OR "Vírus Sinciciais Respiratórios" OR "Virus Sincitial Respiratorio" OR "Vírus Sincicial Respiratório" OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Virus, Human" OR "respiratory syncytial virus" OR "Virus Humano Respiratorio Sincitial" OR mh:"Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infections" OR "Infecciones por Virus Sincitial Respiratorio" OR "Infecções por Vírus Respiratório Sincicial" OR rsv) AND (mh:vaccines OR vaccin* OR vacunas OR vacinas OR mh:d20.215.894* OR mh:vaccination OR vacunación OR vacinação OR mh:"Mass Vaccination" OR mh:immunization OR inmunización OR imunização OR mh:e02.095.465.425.400* OR mh:e05.478.550* OR mh:n02.421.726.758.310* OR mh:n06.850.780.200.425* OR mh:n06.850.780.680.310* OR mh:sp2.026.182.113* OR mh:sp8.946.819.838* OR immuni* OR inmuni* OR imuni*) ) AND ( db:("LILACS") AND type_of_study:("clinical_trials")) AND (year_cluster:[2016 TO 2022])

Data and analyses

Comparison 1. Adenovirus vaccines versus placebo.

| Outcome or subgroup title | No. of studies | No. of participants | Statistical method | Effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1.1 Incidence of the common cold | 1 | Risk Ratio (M‐H, Fixed, 95% CI) | Subtotals only |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Griffin 1970.

| Study characteristics | ||

| Methods |

Design: double‐blind RCT (2 arms) Country: USA (1 site) Clinical setting: Great Lakes Naval Training Center Follow‐up: 9 weeks' basic‐training period Intention‐to‐treat: yes Randomisation unit: participant Analysis unit: participant |

|

| Participants | Great Lakes Naval Training Center, new recruits Randomised: 2307 participants Vaccines group: 1139 (49.3%) Placebo group: 1168 (50.7%) Participants receiving intervention: 1139 Vaccines group: 1139 (49.3%) Placebo group: 1168 (50.7%) Lost postrandomisation: 0% Analysed participants: Vaccines group: 1139 (49.3%) Placebo group: 1168 (50.7%) Age median (mean (SD)): did not report Gender (number of men): 2307 Inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria: not reported |

|

| Interventions | Experimental group: the vaccines used were composed of orally administered live adenovirus 4, parenterally administered inactivated adenovirus 4, and parenterally administered inactivated adenovirus 4 and 7 preparations Control group: placebo Co‐interventions:

|

|

| Outcomes | This RCT did not specify primary or secondary outcomes. Incidence of admissions of participants with respiratory illness (not only hospitalised participants):

Toxic effects |

|

| Notes |

|

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Random sequence generation (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Quote: "Epidemiologic design of this study consisted of the random assignment of one half of the recruits ..." (p 982) Insufficient information to permit a judgement |

| Allocation concealment (selection bias) | Unclear risk | Insufficient information to permit a judgement |

| Blinding of participants and personnel (performance bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Quote: "Double‐blind procedure was followed with paramedical personnel administering the appropriate vaccine or placebo to recruits on their third day after arrival at Great Lakes, just prior to initiation of basic training" (p 982) Quote: "Placebo for the parenterally administered vaccines consisted of an injection of physiological saline, and that for the orally administered vaccine consisted of an identical appearing inert gelatin capsule" (p 982) Comment: blinding of participants and key study personnel ensured, and it is unlikely that the blinding could have been broken |

| Blinding of outcome assessment (detection bias) All outcomes | Low risk | Comment: blinding of outcome assessment was performed with the use of placebo |

| Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias) All outcomes | Low risk | No losses to follow‐up |

| Selective reporting (reporting bias) | Unclear risk | Comment: the study protocol is not available, but it is clear that the published reports include all expected outcomes. However, some outcomes are described in a narrative fashion and not per group. Quote: "... there was no observable toxic reaction to this new live vaccine preparation within the study design." (p 985) |

| Other bias | Unclear risk | The sample size was not reported. There is no table with baseline characteristics of the participants. |

RCT: randomised controlled trial SD: standard deviation

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Abarca 2020 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Ahmad 2022 | Phase 2a ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold |

| Aliprantis 2018 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Aliprantis 2020 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Ascough 2019 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| August 2017 | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Belshe 1982 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Belshe 1992 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Belshe 2004a | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Belshe 2004b | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Beran 2018 | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Bourne 1946 | Assessed common cold symptoms caused by bacterial infections |

| Cicconi 2020 | Phase I ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold |

| Clements 1991 | Wrong design, not RCT |

| Cunningham 2019 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| DeVincenzo 2010 | Wrong design, experimental infection |

| DeVincenzo 2019 | Duplicate record ‐ conference abstract of Sadoff 2021a |

| Doggett 1963 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Domachowske 2017 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Domachowske 2018 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Dudding 1972 | Wrong design, not RCT |

| Esposito 2019 | Assessed common cold symptoms caused by bacterial infections |

| EUCTR2008‐001714‐24‐GB | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold |

| EUCTR2012‐001107‐20‐GB | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2013‐004036‐30‐GB | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2014‐005041‐41‐GB | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2015‐004296‐77‐GB | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2016‐000117‐76‐ES | Phase I/II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2016‐000117‐76‐PL | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| EUCTR2016‐001135‐12‐FR | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2016‐002733‐30‐ES | Phase I/II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| EUCTR2018‐001340‐62‐FI | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Falloon 2017a | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Falloon 2017b | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Falsey 1996 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Falsey 2008 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Fries 2019 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Fulginiti 1969 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Glenn 2016 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Gomez 2009 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Gonzalez 2000 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Greenberg 2005 | Phase II study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Hamory 1975 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Israel 2016 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Karppinen 2019 | Assessed respiratory symptoms caused by bacterial infections |

| Karron 1995a | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Karron 1995b | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Karron 1997 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Karron 2003 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Karron 2005 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Karron 2015 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Karron 2020a | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Karron 2020b | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Kumpu 2015 | Assessed respiratory symptoms caused by bacterial infections |

| Langley 2009 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Langley 2016 | Duplicate record ‐ clinical trial register of Langley 2018 |

| Langley 2017 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Langley 2018 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Lee 2001 | Did not assess incidence of common cold or vaccine safety |

| Lee 2004 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| Leroux‐Roels 2019 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| Lyons 2008 | Phase I study ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Madhi 2006 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Madhi 2020 | Phase III ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| McFarland 2018 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| McFarland 2020a | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| McFarland 2020b | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Munoz 2003 | Unknown phase ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Munoz 2019 | Phase II ‐ did not assess incidence of common cold, did not define common cold |

| Murphy 1994 | Wrong study design, not RCT |

| NCT00139347 | Wrong intervention, this study assessed human rotavirus associated with gastroenteritis |

| NCT00308412 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| NCT00345670 | Assessed lower respiratory tract infection |

| NCT00345956 | Wrong intervention, this study assessed human rotavirus associated with gastroenteritis |