ABSTRACT

The cellular protein SAMHD1 is important for DNA repair, suppressing LINE elements, controlling deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) concentrations, maintaining HIV-1 latency, and preventing excessive type I interferon responses. SAMHD1 is also a potent inhibitor of HIV-1 and other significant viral pathogens. Infection restriction is due in part to the deoxynucleoside triphosphatase (dNTPase) activity of SAMHD1 but is also mediated through a dNTPase-independent mechanism that has been described but not explored. The phosphorylation of SAMHD1 at threonine 592 (T592) controls many of its functions. Retroviral restriction, irrespective of dNTPase activity, is linked to unphosphorylated T592. Sulforaphane (SFN), an isothiocyanate, protects macrophages from HIV infection by mobilizing the transcription factor and antioxidant response regulator Nrf2. Here, we show that SFN and other clinically relevant Nrf2 mobilizers reduce SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation to protect macrophages from HIV-1. We further show that SFN, through Nrf2, triggers the upregulation of the cell cycle control protein p21 in human monocyte-derived macrophages to contribute to SAMHD1 activation. We additionally present data that support another, potentially redox-dependent mechanism employed by SFN to contribute to SAMHD1 activation through reduced phosphorylation. This work establishes the use of exogenous Nrf2 mobilizers as a novel way to study virus restriction by SAMHD1 and highlights the Nrf2 pathway as a potential target for the therapeutic control of SAMHD1 cellular and antiviral functions.

IMPORTANCE Here, we show, for the first time, that the treatment of macrophages with Nrf2 mobilizers, known activators of antioxidant responses, increases the fraction of SAMHD1 without a regulatory phosphate at position 592. We demonstrate that this decreases infection of macrophages by HIV-1. Phosphorylated SAMHD1 is important for DNA repair, the suppression of LINE elements, the maintenance of HIV-1 in a latent state, and the prevention of excessive type I interferon responses, while unphosphorylated SAMHD1 blocks HIV infection. SAMHD1 impacts many viruses and is involved in various cancers, so knowledge of how it works and how it is regulated has broad implications for the development of therapeutics. Redox-modulating therapeutics are already in clinical use or under investigation for the treatment of many conditions. Thus, understanding the impact of redox modifiers on controlling SAMHD1 phosphorylation is important for many areas of research in microbiology and beyond.

KEYWORDS: 4-octyl itaconate, HIV-1, Nrf2, SAMHD1, sulforaphane, T592, THP-1, dimethyl fumarate, macrophages

INTRODUCTION

Sulforaphane (SFN), a well-established mobilizer of Nrf2, the master transcriptional regulator of the cellular antioxidant response (1), blocks human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection of macrophages. Restriction of infection occurs after the viral genome has been reverse transcribed but before viral DNA enters the nucleus (2). Curiously, RNA expression arrays probing for transcriptional changes in response to SFN treatment showed no increases in mRNAs encoding known anti-HIV factors and no decreases in mRNAs encoding known HIV infection cofactors. The transcription of interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) was also reduced in response to Nrf2 mobilization (3), a finding consistent with the observations of others (4, 5).

SAM and HD domain-containing protein 1 (SAMHD1) is a multifunctional cellular protein that potently inhibits HIV-1 infection (6–8). The ability of SAMHD1 to protect against HIV-1 is linked to its phosphorylation status at threonine 592 (T592) (9, 10). SAMHD1 is a deoxynucleoside triphosphohydrolase capable of reducing the cellular deoxynucleoside triphosphate (dNTP) pool to inhibit HIV reverse transcription (11). Interestingly, there are discordant reports as to whether the deoxynucleoside triphosphatase (dNTPase) activity of SAMHD1 is required to block HIV infection (9, 12). Further complicating the role of SAMHD1 in HIV biology are other conflicting reports as to whether phosphorylation influences dNTPase activity. For example, T592 phosphorylation can reduce SAMHD1 dNTPase activity to ensure sufficient dNTPs for DNA replication in cycling cells (13, 14). Other work, however, found that phosphomimetic versions of SAMHD1 carrying T592E and T592D changes failed to inhibit HIV-1 despite demonstrating dNTPase activity like that of wild-type SAMHD1 (9). Nonetheless, most published work shows that T592 phosphorylation abolishes SAMHD1 restriction of HIV infection.

T592 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 is influenced by several cellular proteins, mostly in the context of cell cycle progression. These proteins include kinases, phosphatases, cyclins, and cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors. For example, cyclin A2/CDK1/2 has been shown to phosphorylate T592 during S phase (15), and the PP2A-B55α phosphatase complex has been shown to dephosphorylate T592 during mitotic exit (16). p21, an inhibitor of CDKs, has been shown to protect myeloid lineage cells from HIV-1 by blocking T592 phosphorylation (17–20).

In addition to the regulation of SAMHD1 activity through T592 phosphorylation, several laboratories have recognized that SAMHD1 is also redox sensitive. SAMHD1 multimerization and dNTPase function were found to be inhibited under oxidizing conditions. Additionally, SAMHD1 can be oxidized in response to proliferative signals, and this can relocalize the protein out of the nucleus (21). Subsequent work by Wang et al. found that the alteration of redox-sensitive cysteines, specifically C341S and C522S, abolished HIV restriction by SAMHD1 (22). Interestingly, they found that multimerization and dNTPase activity were not sufficient to establish the antiviral state and that restriction depended on redox transformations (22). Furthermore, work that focused on the modeling of the SAMHD1 structure concluded that the glutathionylation of C522 could cause structural disruptions far from the residue itself and that there may be transient interactions between C522 and C341 (23). Whether or not the cellular antioxidant response can capitalize on the SAMHD1 redox sensitivity to influence T592 phosphorylation is unclear.

Here, we show that, rather than altering the abundance of a restriction factor or an infection cofactor, Nrf2 mobilization causes a decrease in the T592 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 and that SAMHD1 is required for SFN to protect macrophages from HIV-1. These findings are particularly interesting given that SFN blocks infection after reverse transcription (2). We further demonstrate that SFN upregulates p21 and that this is correlated with reduced SAMHD1 phosphorylation in human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs). We go on to exclude other possible contributions of SFN to SAMHD1 anti-HIV activity by demonstrating that neither SAMHD1 multimerization nor nuclear trafficking is altered by SFN treatment of macrophages. In total, the findings presented here are the first to unite the SAMHD1 phosphorylation status with the Nrf2 pathway and highlight the use of Nrf2 mobilizers as tools for understanding the enigmatic nature of retroviral restriction by SAMHD1.

RESULTS

SFN treatment reduces SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation in macrophages.

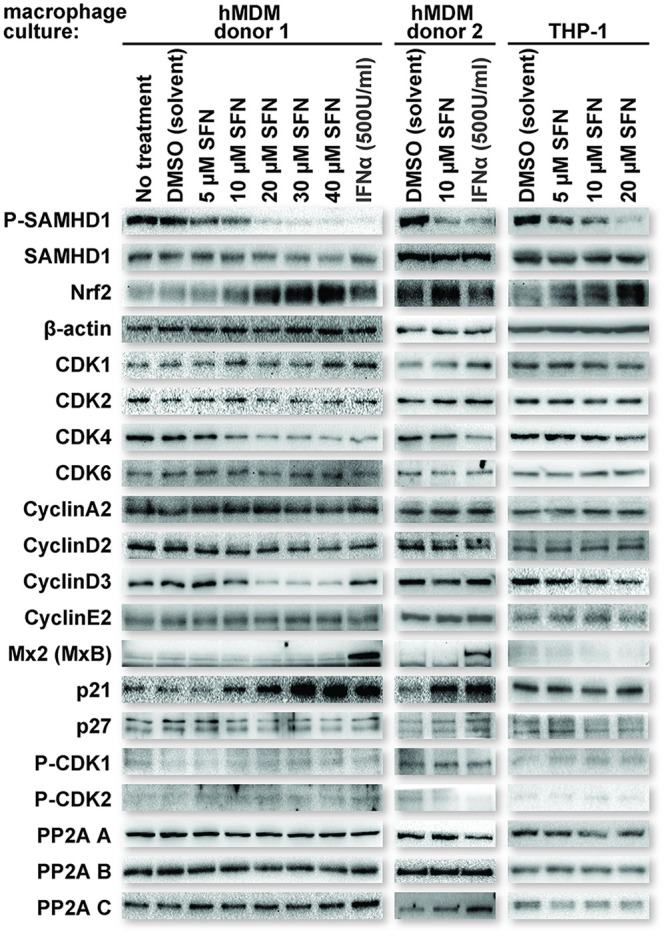

Previous work investigating SFN/Nrf2 and HIV infection of macrophages did not detect changes in the total levels of SAMHD1 in response to SFN (2). However, the antiretroviral activation status of SAMHD1, through T592 phosphorylation, was not assessed. We therefore sought to test this. Here, we treated hMDMs and THP-1 macrophages with different concentrations of SFN for 24 h and then assessed the levels of T592-phosphorylated SAMHD1 (P-SAMHD1) and total SAMHD1 by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and Western blot analysis. β-Actin levels served as loading controls, while Nrf2 levels served as controls for SFN function. Untreated cells, solvent (dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO])-treated cells, and interferon alpha (IFN-α)-treated cells were used as negative and positive controls for SAMHD1 dephosphorylation, respectively. SFN-treated macrophages demonstrated decreases in P-SAMHD1 in a dose-dependent manner in both macrophage cell types. Total SAMHD1 and β-actin levels remained constant, while Nrf2 levels increased, as expected, with SFN treatment (Fig. 1). IFN-α is known to promote SAMHD1 dephosphorylation (10). IFN-α treatment also upregulated Mx2, as expected (24–26). Of note, we recognize that the term “dephosphorylation” technically refers to the actions of a phosphatase. However, here, we use the terms “dephosphorylate” and “dephosphorylation” to specifically describe an overall decrease in T592 phosphorylation of the SAMHD1 population as a whole.

FIG 1.

SFN treatment reduces SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation in macrophages. Cultures of human monocyte-derived macrophages (hMDMs) from two separate donors (left and middle columns) and cultures of phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-differentiated THP-1 macrophages (right column) were either untreated or treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h prior to collection for Western blot analysis. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. IFN-α, interferon alpha.

SFN fails to protect SAMHD1-deficient macrophages from HIV-1 transduction.

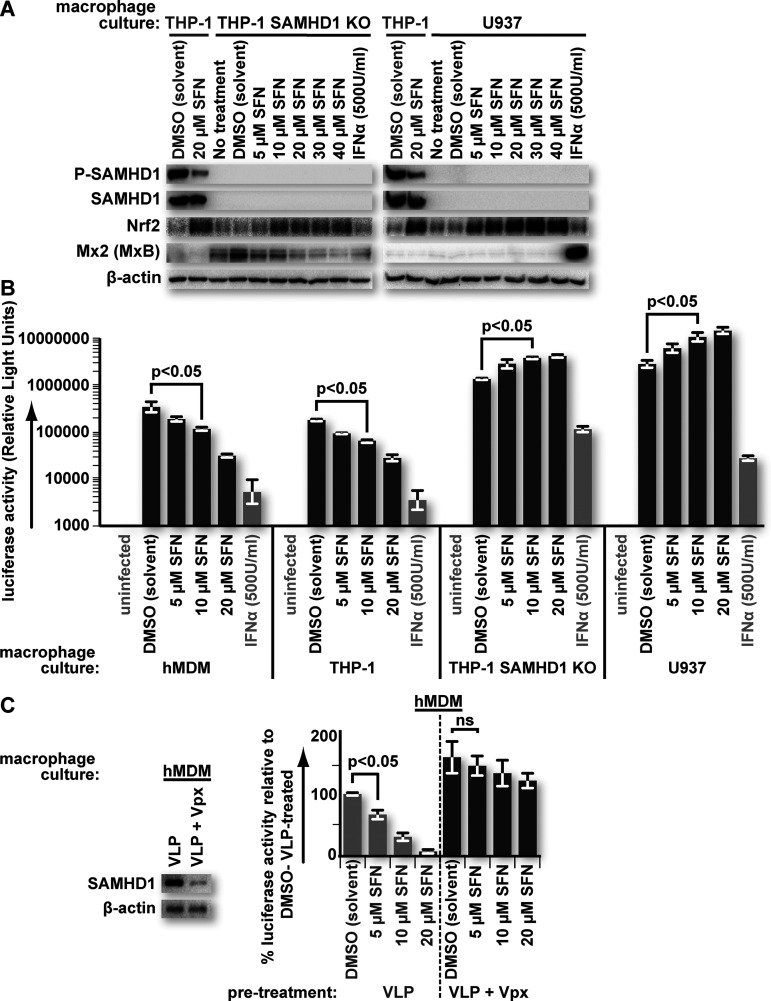

To determine whether SAMHD1 is important for SFN/Nrf2-mediated restriction, we tested whether SAMHD1-deficient macrophages would restrict HIV-1 infection in response to SFN. U937 cells are a monocytic cell line that does not produce SAMHD1. THP-1 SAMHD1 knockout (THP-1SAMHD1KO) cells were derived from the THP-1 monocytic cell line in which the samhd1 gene had been disrupted by CRISPR-Cas9 editing (27). Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA)-differentiated THP-1SAMHD1KO and U937 macrophages were treated with DMSO or concentrations of SFN from 5 μM to 40 μM. As expected, SAMHD1 was not detectable by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis in either THP-1SAMHD1KO cells or U937 macrophages. However, we saw that the levels of Nrf2 increased with SFN in these cells, indicating that SFN function was maintained. Wild-type THP-1 (THP-1WildType) macrophages served as controls (Fig. 2A).

FIG 2.

SFN fails to protect SAMHD1-deficient macrophages from HIV-1 transduction. (A) Cultures of PMA-differentiated THP-1, THP-1 SAMHD1 knockout (KO), and U937 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h prior to collection for Western blot analysis. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. (B) Cultures of hMDMs and PMA-differentiated THP-1, THP-1 SAMHD1 KO, or U937 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h. After 24 h, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing equivalent titers of a vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped HIV-1 luciferase-encoding reporter virus, except for the “uninfected” samples. Forty-eight hours after virus transduction, the cells were lysed, and a luciferase assay was performed. Error bars represent the standard deviations from replicates (n = 3). (C) Cultures of hMDMs were transduced with either “empty” VSV-G-pseudotyped SIV-based virus-like particles (VLPs) or VLPs in which SIV Vpx was packaged. Twenty-four hours after VLP treatment, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the indicated reagents. Twenty-four hours after treatment with the indicated reagents, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing equivalent titers of the VSV-G-pseudotyped HIV-1 luciferase-encoding reporter virus. Twenty-four hours after virus transduction, the cells were lysed, and a luciferase assay was performed. Data are represented as percentages relative to empty VLP-transduced, solvent (DMSO)-treated cultures. Error bars represent the standard deviations from replicates (n = 3). A parallel set of VLP-treated cultures was lysed after 24 h, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins to assess SAMHD1 levels. Parametric Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance. ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

Cultures of SAMHD1-deficient macrophages were treated for 24 h, as described in the legend of Fig. 2A. After 24 h, the cells were transduced with vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein (VSV-G)-pseudotyped HIV-1 luciferase reporter virus. Forty-eight hours after transduction, the cells were harvested, and luciferase assays were performed on the lysates to assess the impact of SFN on HIV-1 transduction. SFN failed to induce protection of SAMHD1-deficient macrophages against HIV-1 transduction. Similarly treated hMDMs and THP-1WildType macrophages served as controls and exhibited a dose-dependent decrease in luciferase activity after SFN pretreatment (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, we observed an increase in luciferase activity in the absence of SAMHD1. This may reflect the anti-inflammatory properties of SFN and Nrf2, particularly regarding type I interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) (3–5, 28). In support of this, THP-1SAMHD1KO macrophages exhibited higher steady-state levels of the ISG product Mx2 than did THP-1WildType macrophages. This is likely due to the autonomous production of type I interferon (29). Indeed, SFN treatment led to a dose-dependent decrease in Mx2 levels in these cells (Fig. 2A).

We also tested whether SAMHD1 is important for SFN-mediated protection from HIV-1 in primary hMDMs. Here, cultures were pretreated with simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV)-derived genome-free virus-like particles (VLPs) loaded with Vpx to deplete SAMHD1 prior to incubation in SFN-containing medium. Cells pretreated with VLPs lacking Vpx served as controls. SIV/HIV-2 Vpx is an established antagonist of SAMHD1, triggering proteosome-dependent SAMHD1 degradation through the CRL4 ubiquitin ligase complex (6, 7, 30). SAMHD1 depletion was confirmed by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Concordant with our results in SAMDH1-deficient macrophage cell lines, SFN failed to significantly protect hMDMs from HIV-1 transduction when SAMHD1 levels were predepleted (Fig. 2C).

p21 upregulation correlates with SFN treatment and SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in hMDMs.

To assess the levels of candidate proteins influencing the phosphorylation status of SAMHD1, lysates of hMDMs used to generate the data in Fig. 1 were further screened for the following proteins: p21 and p27 (cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor proteins) (17–20); cyclin A2, cyclin E2, cyclin D2, and cyclin D3 (proteins required for the activation of kinases known to phosphorylate SAMHD1); CDK1, P-CDK1, CDK2, P-CDK2, CDK4, and CDK6 (kinases shown to phosphorylate SAMHD1) (10, 13, 15, 31–33); and PP2A subunit A/B/C (a protein phosphatase complex shown to dephosphorylate SAMHD1) (16). There were no detectable changes in the levels of most proteins tested, except for p21, which was increased with increasing SFN concentrations in hMDMs. Of note, both cyclin D3 and CDK4 showed decreases at higher SFN concentrations, suggesting that they may contribute to the SFN-mediated reduction of SAMHD1 phosphorylation in hMDMs (Fig. 1, left and middle columns).

SFN relies on Nrf2 for SAMHD1 dephosphorylation and p21 upregulation in hMDMs.

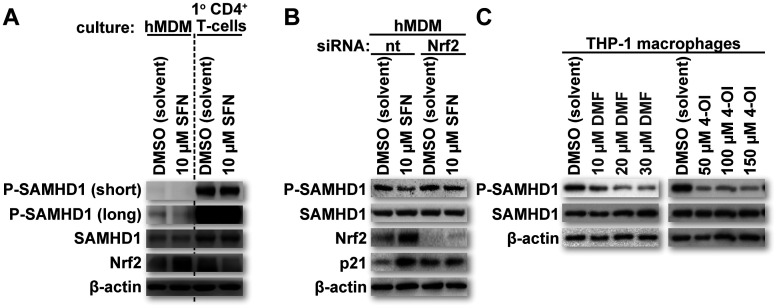

SFN treatment inhibits HIV-1 transduction in hMDMs but not in primary activated CD4+ T cells or cell lines such as HeLa or HEK293T (2). Interestingly, these other cell types have reduced steady-state levels of Nrf2 relative to those in macrophages (3). Lower Nrf2 levels may, in part, explain why these cells fail to be protected by SFN treatment despite producing SAMHD1. To test whether steady-state Nrf2 levels correlate with SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation, we treated primary activated CD4+ T cells with either DMSO or 10 μM SFN for 24 h. The cultures were then collected, and Western blot analysis was performed to assess the levels of P-SAMHD1, SAMHD1, and Nrf2. β-Actin levels served as loading controls. Similarly treated hMDMs served as additional controls. Consistent with the observations of others, the proportion of P-SAMHD1 was higher in primary activated CD4+ T cells than in hMDMs (10). Importantly, SFN-mediated Nrf2 upregulation and SAMHD1 dephosphorylation occurred only in hMDMs (Fig. 3A). These data further support reduced SAMHD1 phosphorylation as the major mechanism by which SFN protects against HIV-1 transduction and point toward a role for Nrf2 in this effect.

FIG 3.

SFN relies on Nrf2 for SAMHD1 dephosphorylation and p21 upregulation in hMDMs. (A) Cultures of primary activated CD4+ T cells and hMDMs were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. “short” refers to a shorter exposure, whereas “long” refers to a longer exposure. (B) Cultures of hMDMs were transfected with either a nontargeting (nt) short interfering RNA (siRNA) or an siRNA targeting the mRNA of Nrf2. Forty-eight hours after siRNA transfection, the culture medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the indicated reagents. Twenty-four hours after treatment with the indicated reagents, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. (C) Cultures of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h. “DMF” and “4-OI” represent the Nrf2 activators dimethyl fumarate and 4-octyl itaconate, respectively. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins.

Several studies have linked both SFN and Nrf2 to increased levels of p21 in multiple cell types through multiple mechanisms (34–38). Furthermore, SFN/Nrf2 has been shown to direct macrophage polarization toward M2 or M2-like phenotypes (39–41), and other work has shown that p21 can contribute to M2 polarization (42). Our findings demonstrating that SFN promotes a dose-dependent increase in p21 levels in hMDMs are therefore consistent with the findings of these other studies. In combination with work demonstrating the ability of p21 to promote unphosphorylated SAMHD1 in myeloid lineage cells (17–19), the data presented here suggest at least one mechanism by which SFN can support reduced SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation in macrophages. To test the role of SFN-mediated Nrf2 upregulation in influencing SAMHD1 phosphorylation in hMDMs, we transfected hMDMs with either a nontargeting control short interfering RNA (siRNA) or one targeting the mRNA of Nrf2. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the hMDM cultures were treated with either DMSO or 10 μM SFN for 24 h. The hMDM cultures were then collected, and SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis were performed to assess the levels of P-SAMHD1, SAMHD1, Nrf2, and p21. β-Actin levels served as loading controls. In agreement with the observations of others and in alignment with our observations thus far, Nrf2 depletion negated both SFN-mediated p21 upregulation and SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in hMDMs (Fig. 3B). Additionally, other established Nrf2 mobilizers, namely, dimethyl fumarate (DMF) (43) and 4-octyl itaconate (4-OI) (44, 45), also reduced SAMHD1 phosphorylation (Fig. 3C) in THP-1 macrophages. Of note, DMF, a compound used for the treatment of psoriasis and multiple sclerosis, was previously shown to block HIV replication in macrophages through an unclear mechanism (2, 46). These data strongly implicate SFN-mediated Nrf2 upregulation as a mechanism contributing to SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in macrophages and p21 upregulation in hMDMs.

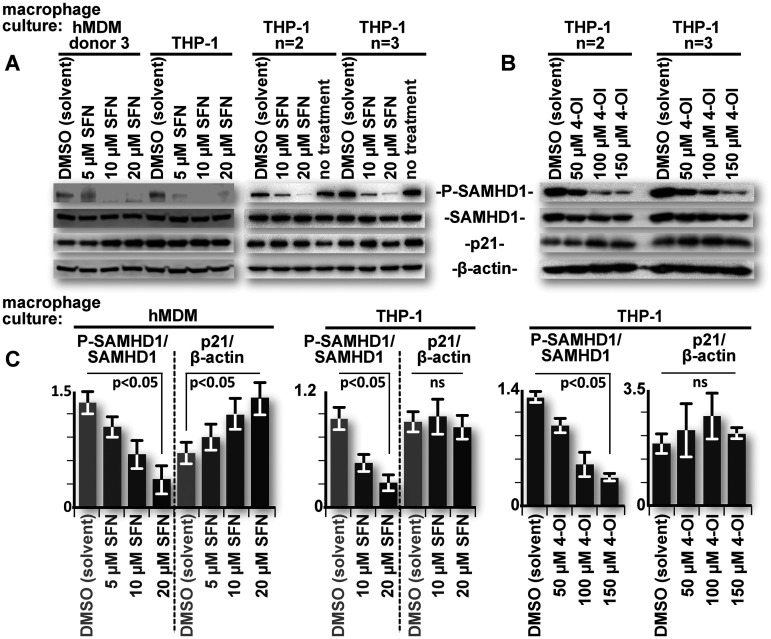

p21 levels do not correlate with SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in THP-1 cell line-derived macrophages.

p21 upregulation can, in part, explain the lack of SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation in SFN-treated hMDMs. However, THP-1 macrophages exhibited a similar dose-dependent decrease in SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation without a detectable change in p21 levels (Fig. 1, right column). Indeed, unlike hMDMs, no consistent correlation of p21 levels with SAMHD1 phosphorylation was observed in THP-1 macrophages treated with either SFN or the other Nrf2 mobilizer, 4-OI, over multiple replicates (Fig. 4A and B, respectively; quantified in Fig. 4C). These data suggest that SFN employs an additional mechanism to promote SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in macrophages that is independent of p21 levels.

FIG 4.

p21 levels do not correlate with SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in THP-1 cell line-derived macrophages. (A) hMDMs and replicate cultures of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were either untreated or treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. (B) Duplicate cultures of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h. “4-OI” represents the Nrf2 activator 4-octyl itaconate. After 24 h, the cells were lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. (C) Densitometric analysis of band intensities was performed on relevant data from all donor and replicate THP-1 macrophage cultures. Relevant ratios of P-SAMHD1 to total SAMHD1 and p21 to β-actin were pooled and graphed. Error bars represent the standard deviations from replicates (n > 3 [SFN], and n = 2 [4-OI]) for THP-1 macrophages and the standard errors among hMDM donors (n > 5). Parametric Student’s t test was used to determine statistical significance. ns, not significant (P > 0.05).

SFN does not influence SAMHD1 multimerization or nuclear trafficking in macrophages.

For the THP-1 macrophages, there were similarities to the hMDM data, most notably for the decrease in P-SAMHD1 and the increase in Nrf2 levels after treatment with SFN (Fig. 1). Interestingly, p21 (Fig. 4), cyclin D3, and CDK4 levels did not appreciably change in THP-1 macrophages treated with SFN at concentrations where SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation was reduced (Fig. 1, right column). These results suggest that while the differential regulation of these proteins may contribute to SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in hMDMs, they are not the only drivers of this effect.

SAMHD1 has been shown to be sensitive to changes in the redox state of the cell owing to at least three redox-sensitive cysteines within the protein, C341, C350, and C522 (21–23). The formation of a higher-molecular-weight SAMHD1 tetramer is necessary for dNTPase activity (47). Accordingly, multimerization and dNTPase function were found to be inhibited under oxidizing conditions. Additionally, the oxidation of SAMHD1 can relocalize the protein out of the nucleus (21). Interestingly, other work found that alterations of redox-sensitive cysteines, specifically C341S and C522S, abolished HIV restriction by SAMHD1 independent of multimerization and dNTPase activity (22). Furthermore, the glutathionylation of C522 has been shown to cause structural disruptions in SAMHD1 (23). SFN mobilizes Nrf2 to activate an antioxidant response, thereby creating reducing conditions in the cell (1). These findings led us to hypothesize that SFN may influence conformational changes in SAMHD1 to enhance multimerization and/or favor nuclear localization. These changes may further stimulate HIV restriction by SAMHD1 or influence T592 phosphorylation.

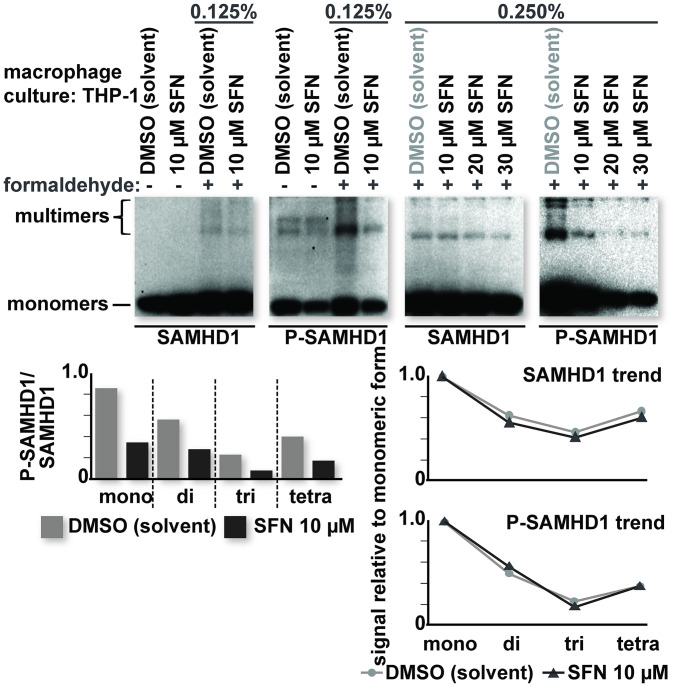

To test these possibilities, we first assessed whether SFN influences endogenous SAMHD1 multimerization. THP-1 macrophages were treated with either DMSO or SFN for 24 h. The cultures were then treated with formaldehyde for 10 min prior to quenching with 0.125 M glycine. THP-1 macrophages that were not treated with formaldehyde served as controls. Formaldehyde causes the covalent cross-linking of proteins, enabling the detection of multimeric forms of SAMHD1 under otherwise denaturing conditions (47). The levels of SAMHD1 and P-SAMHD1 were determined by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Presumably, differentiated macrophages have lower levels of multimeric SAMHD1 than cycling cells, possibly due to reduced dGTP concentrations (48). We were, however, able to detect higher-molecular-weight bands with both the SAMHD1- and P-SAMHD1-specific antibodies. Importantly, these higher-molecular-weight bands were present predominantly in formaldehyde-treated samples. No appreciable change in the abundance of higher-molecular-weight bands versus lower-molecular-weight bands was observed in 10 μM SFN-treated samples relative to those treated with DMSO. A dose-dependent loss of SAMHD1 phosphorylation was observed in all molecular weight species of SAMHD1 in THP-1 macrophages treated with SFN (Fig. 5). These results indicate that SFN does not influence the multimeric state of SAMHD1 and that all forms of SAMHD1 are susceptible to SFN-mediated dephosphorylation.

FIG 5.

SFN does not influence SAMHD1 multimerization in macrophages. Cultures of PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h prior to formaldehyde treatment. After 24 h, the culture medium was removed and replaced with either phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) or PBS containing the indicated percentage of formaldehyde. Ten minutes after incubation in PBS or PBS plus formaldehyde, the reaction was quenched by replacing the PBS or PBS plus formaldehyde with PBS containing 0.125 M glycine. The cells were then lysed, and proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. Densitometric analysis of the band intensities was performed for all molecular weight species detected. The ratio of P-SAMHD1 to total SAMHD1 (bottom left) and the ratio of multimeric (di-, tri-, and tetrameric) to monomeric forms (bottom right) were calculated and graphed. The data shown are representative of a trend observed over multiple replicates (n > 3).

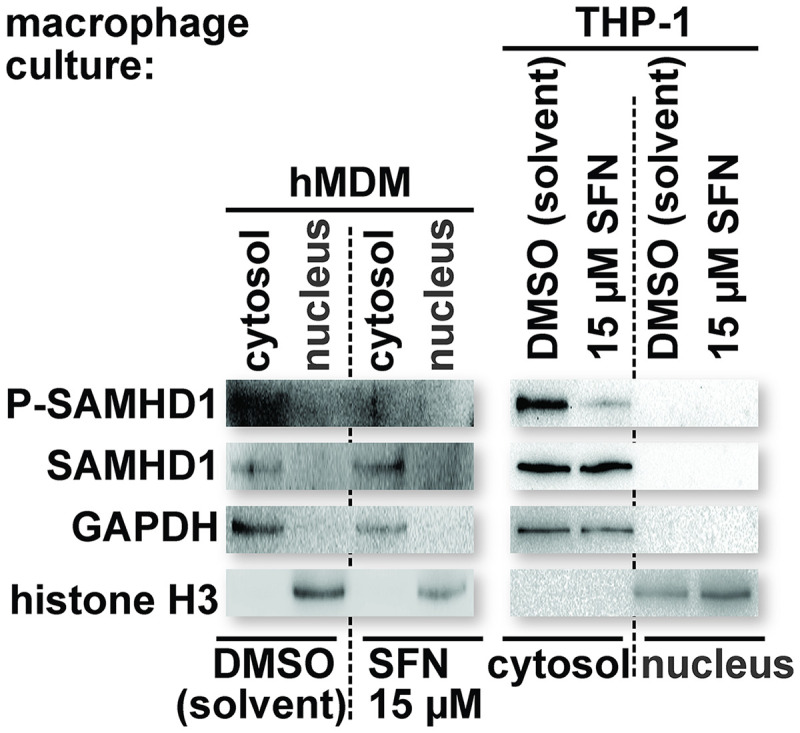

We next treated hMDMs and THP-1 macrophages with DMSO or 15 μM SFN for 24 h and then performed fractionations to separate the nuclear and cytosolic compartments of the cell. Lysates were collected under each condition and probed for P-SAMHD1 and SAMHD1 by SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. The lysates were additionally probed for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) and histone H3 to assess the purity of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively. Although SAMHD1 contains a nuclear localization signal (49, 50), the location of SAMHD1 varies by cell type and cell cycle status (50–52), and it can also be found in the cytosolic compartment of primary macrophages and CD4+ T cells (8, 53). Additionally, nuclear localization is not required for retroviral restriction by SAMHD1 (50, 54). We observed SAMHD1 to be predominantly cytosolic in both hMDMs and THP-1 macrophages. Importantly, treatment with SFN did not lead to a shift of the SAMHD1 localization from one cellular compartment to another; however, SAMHD1 dephosphorylation was still observed in macrophages treated with SFN (Fig. 6). Together, these data indicate that SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation and HIV-1 restriction are unlikely to be due to changes in the oligomerization state or nuclear localization of SAMHD1 in macrophages.

FIG 6.

SFN does not influence SAMHD1 nuclear trafficking in macrophages. Cultures of hMDMs and PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were treated with the indicated reagents for 24 h prior to collection for fractionation. After 24 h, the cells were lysed in a manner to disrupt the plasma membrane but maintain the integrity of the nuclear membrane (see Materials and Methods). Nuclei were separated from the cytosolic contents by centrifugation through a sucrose cushion. The supernatant containing the cytosolic contents was collected, and an equal volume of 2× Laemmli buffer was added. Nuclei were washed 4 times in fractionation buffer (buffer B), and an equal volume of 2× Laemmli buffer was added. Cytosolic and nuclear fraction proteins were resolved by SDS-PAGE. Western blot analysis was performed on the resolved lysate proteins using antibodies specific for the indicated proteins. The levels of GAPDH and histone H3 were used to confirm the purity of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The key findings of this work have demonstrated that SFN promotes the dephosphorylation of SAMHD1 to protect macrophages from HIV-1 infection (Fig. 1 and 2). The observations of others (17–19, 34–42) in combination with our observations support a role for p21 in SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in hMDMs (Fig. 1 and 3). The lack of responsiveness regarding p21 levels in SFN-treated THP-1 macrophages is not entirely surprising given that this leukemia-derived cell line lacks certain cell cycle controls, such as functional p53. However, the findings that THP-1 macrophages still exhibit SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in response to SFN (Fig. 1 and 4) suggest that while p21 likely contributes to this effect in primary macrophages, another mechanism may also be involved. This other effect may be due, at least in part, to changes in the oxidation state of the cell as SFN/Nrf2 is known to promote reducing conditions (1). It may also be mediated by one or more proteins that are mobilized by SFN/Nrf2 and influence SAMHD1 phosphorylation regardless of the oxidation state of the cell. While SFN does not impact redox-sensitive multimerization or nuclear trafficking in macrophages (Fig. 5 and 6), given the increasing body of work highlighting the redox sensitivity of SAMHD1 (21–23), it is possible that the reducing conditions initiated by SFN/Nrf2 cause conformational changes in SAMHD1 that alter the accessibility of T592 to a kinase, a phosphatase, or both. Future work assessing the impact of C341, C350, and/or C522 alterations on SFN-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation will provide additional insights. It is also possible that the environment promoted by SFN alters the activity of kinases and phosphatases that control SAMHD1 activity. For example, the PP2A-B55α phosphatase complex exhibits intricate and differential regulation depending on which reactive oxygen species are abundant in the cell (55). The latter possibility may not be reflected by an overall change in protein levels and would therefore not be detected by our analysis.

Initially, SAMHD1 restriction of retroviral infection could be explained by dNTPase impairment of reverse transcription (11, 47, 56, 57). However, a growing body of literature is revealing another dNTPase-independent mechanism by which SAMHD1 may protect against HIV (9, 12, 58–60). The latter sets of observations are consistent with early work wherein Vpx was shown to overcome a pronounced block to the nuclear import of viral DNA relative to the modest block at reverse transcription. HIV-2/SIV lacking Vpx exhibited a substantial two-long-terminal-repeat (2-LTR) circle deficit, indicative of failed nuclear import, relative to the wild-type virus (61–63). This defect mirrors the one encountered by HIV-1 in SFN-pretreated macrophages (2). Here, we have linked the antiviral activity of SFN to SAMHD1 (Fig. 1 and 2). Thus, SFN and other Nrf2 mobilizers may be useful tools for understanding dNTPase-independent retroviral restriction by SAMHD1. Moreover, the Nrf2-mediated suppression of interferon-stimulated genes (4, 5) may help to isolate this restriction from the background of other antiviral mechanisms.

SAMHD1 is revealing itself to be a versatile protein with both pro- and antiretroviral functions that extend beyond its dNTPase and uncharacterized dNTPase-independent antiviral functions. For example, P-SAMHD1 binds to DNA, which is important for DNA repair and the suppression of LINE elements (64, 65), functions that are likely to reduce type I interferon. Work by Antonucci et al. has shown that SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 gene expression and negatively modulates the reactivation of viral latency (66). The suppression of LTR-driven gene expression was somewhat specific in that it hindered the function of HIV-1 and human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) LTRs but not that of the murine leukemia virus (MLV) LTR. Importantly, in that work, Antonucci et al. showed that purified recombinant wild-type SAMHD1 bound the HIV-1 LTR specifically. Notably, T592 must maintain the capacity to be phosphorylated for suppression to occur (66). Finally, Yu et al., examining nucleic acid binding by SAMHD1, found that mutations impairing the formation of oligonucleotide-bound tetramers abolished the capacity to block infection while retaining the ability to deplete dNTPs (67). It would therefore be of interest to determine whether SFN/Nrf2-mediated SAMHD1 dephosphorylation can enable immune detection and, thus, the clearance of latently infected cells.

Recent work showed that SAMHD1 promotes an antiretroviral immune response in Friend retrovirus-infected mice exposed to lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (68). This could be related, at least in part, to a decrease in SAMHD1 T592 phosphorylation. In macrophages, LPS brings about a dramatic reduction in P-SAMHD1 (69). In macrophages and B cells, LPS triggers the production of interferons (70) that promote SAMHD1 dephosphorylation in macrophages (33) (Fig. 1 and 2) and could act similarly on other infection targets. Whether interferon can mediate a reduction in phosphorylated SAMHD1 in other cell types has not been tested. LPS, in addition to increasing interferon production, also mobilizes Nrf2 (71), which we have shown is involved in decreasing P-SAMHD1. This pathway is not available in all cell types (Fig. 3A). SFN and similar Nrf2 mobilizers may allow the contributions of these pathways to be studied individually.

Finally, the findings presented here establish a novel way to manipulate SAMHD1 function using exogenous Nrf2 mobilizers. The Nrf2 pathway may therefore provide points of experimental approaches and/or therapeutic interventions that extend beyond macrophages, possibly to other targets of HIV and/or to other viruses wherein SAMHD1 activity can influence infection outcomes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Sulforaphane (SFN) (catalog no. S8044; LKT Laboratories), dimethyl fumarate (DMF) (catalog no. 242926; Sigma-Aldrich), or 4-octyl itaconate (4-OI) (catalog no. SML2338; Sigma-Aldrich) was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (catalog no. J66650K2; Thermo Fisher Scientific) to make a 50 mM stock. IFN-α (catalog no. 11200; PBL Assay Science), 16% formaldehyde (catalog no. 18814; Polysciences, Inc.), recombinant human interleukin-2 (IL-2) (catalog no. 200-02; Peprotech), and phytohemagglutinin (PHA) (catalog no. L1668-5MG; Sigma-Aldrich) were also used.

Cell culture.

HEK293T cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Elutriated human monocytes and lymphocytes were obtained from healthy donors at the University of Nebraska Medical Center (Omaha, NE). The monocytes were differentiated into macrophages by incubation in serum-free DMEM for 2 h, followed by a 12-day incubation in DMEM supplemented with 10% human AB serum. CD4+ lymphocytes were isolated using an immunomagnetic negative-selection kit (catalog no. 17952; Stemcell Technologies). Isolated CD4+ lymphocytes were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% human AB serum, 2.5 μg/mL PHA, and 10 U/mL IL-2 for 1 week to favor T-cell activation and expansion. The Albany Medical College Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects and the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Institutional Review Board approved our protocol for the use of primary human leukocytes. A category 4 exemption from consent procedures was granted for the use of deidentified samples. All cultures were maintained at 37°C in the presence of 5% CO2. Monocytic THP-1 (ATCC) and U937 (ATCC) cell lines were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% FBS. These cells were differentiated into a macrophage-like state by incubation in medium containing 5 ng/mL phorbol myristate acetate (PMA) for 5 days at 37°C with 5% CO2. THP-1 SAMHD1 knockout (THP-1SAMHD1KO) cells were derived from the THP-1 monocytic cell line in which the samhd1 gene had been deleted through CRISPR-Cas9 editing (27) and were a gift from Baek Kim.

Immunoblotting and densitometric analysis.

Cells were lysed with Laemmli buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% SDS, 10% glycerol, and 0.1% bromophenol blue) and resolved by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). Proteins were transferred onto a polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membrane (catalog no. IPVH00010; Millipore Sigma), blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA), and dissolved in wash buffer (0.1% Tween 20 in 1× phosphate-buffered saline [PBS] or 1× Tris-buffered saline) before three washes in wash buffer. The membranes were then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. The primary antibodies used in this study were anti-β-actin (catalog no. 3700), anti-CDK1 (cdc2) (catalog no. 77055), anti-CDK2 (catalog no. 2546), anti-CDK4 (catalog no. 12790), anti-CDK6 (catalog no. 3136), anti-cyclin A2 (catalog no. 4656), anti-cyclin D2 (catalog no. 3741), anti-cyclin D3 (catalog no. 2936), anti-cyclin E2 (catalog no. 4132), anti-Nrf2 (catalog no. 12721), anti-p21 Waf1/Cip1 (catalog no. 2947), anti-p27 Kip1 (catalog no. 3698), anti-P-CDK1 (phospho-cdc2 at Tyr15) (catalog no. 9111), anti-P-CDK2 (phospho-CDK2 at Thr160) (catalog no. 25615), anti-PP2A subunit A (catalog no. 2039), anti-PP2A subunit B (catalog no. 4953), anti-PP2A subunit C (catalog no. 2259), anti-P-SAMHD1 (phosphorylation at Thr592) (catalog no. 89930), and anti-SAMHD1 (catalog no. 49158) from Cell Signaling Technology and anti-Mx2/B (catalog no. sc-47197) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Following incubation, primary antibody was removed, and membranes were washed three times with wash buffer before incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody. Secondary antibodies were diluted 1:10,000 in wash buffer containing either 5% milk or 5% BSA. The membranes were then incubated overnight at 4°C on a rocking platform. The secondary antibodies used in this study were anti-mouse (catalog no. G21040), anti-rabbit (catalog no. G21234), and anti-goat (catalog no. 81-1620) from Thermo Fisher Scientific. Following incubation, primary antibody was removed, and the membranes were washed three times with wash buffer before the addition of a chemiluminescent substrate and exposure. Blot imaging was done with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc XRS+ imaging system. Densitometric analyses were done using ImageJ image analysis software from the NIH (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/).

Virus preparation and transduction analysis.

Five million HEK293T cells were cotransfected with expression vectors for the HIV-1 luciferase reporter clone, pNL4-3 env(−) nef(−) luc(+), a gift from Nathaniel Landau, together with pCLVSV-G for pseudotyping HIV with the envelope glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus. Transfections were done using a standard calcium phosphate protocol with a total of 20 μg of DNA at an equimolar ratio of the viral expression vector to the VSV-G expression vector. Twenty-four hours after transfection, the supernatant from transfected cells was cleared of producer cells by centrifugation and then transferred to experimental cell cultures. Aliquots of the supernatants obtained from viral producer cells were tested for the generation of equivalent viral titers by serial dilution and subsequent transduction of the GHOST X4/R5 indicator cell line (from Vineet N. KewalRamani and Dan R. Littman through the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH). Cells transduced with luciferase reporter virus were harvested at 24 to 48 h posttransduction and prepared for luciferase assays by using the Promega luciferase assay kit (catalog no. E501). The culture medium was removed, and cells were washed with PBS. Samples were lysed, and cellular debris was cleared by centrifugation at 18,000 × g for 1 min. Fifty microliters of each sample was mixed with 50 μL of the luciferase assay reagent. Luciferase activity, in relative light units (RLU), was measured by photon emission using a Promega GloMax 20/20 luminometer. The simian immunodeficiency virus packaging construct ARP-13456 (SIV3+) was obtained from Tom Hope through the NIH HIV Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH. Virus-like particles (VLPs) were generated by transfection, as described above, with a total of 20 μg of DNA at an equimolar ratio of the SIV3+ expression vector to the VSV-G expression vector to the pCMV4 SIVmac239Vpx expression vector, a gift from Nathaniel Landau. VLPs lacking Vpx were made similarly, with the exception that the pCMV4 SIVmac239Vpx expression vector was replaced with the empty pcDNA3.1(−) vector.

siRNA transfection.

Short interfering RNAs (siRNAs) were obtained from Horizon Discovery, including a nontargeting siRNA (catalog no. D-001810-01) and an Nrf2-specific siRNA (catalog no. J-003755-09). siRNA was transfected into cell cultures by using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (catalog no. 13778075; Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Formaldehyde cross-linking.

A total of 500,000 PMA-differentiated THP-1 macrophages were incubated in 1× PBS containing either 0.125% or 0.250% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After 10 min, the reaction was quenched by the removal of formaldehyde-containing PBS and the addition of PBS containing 0.125 M glycine. The cells were then harvested for immunoblotting as described above.

Cell fractionation.

Five million cells were collected and washed twice with 1× phosphate-buffered saline. The cells were incubated in 1 mL buffer B (10 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 1.5 mM MgCl2, 10 mM KCl, and a protease inhibitor cocktail [Roche]) on ice for 20 min. According to methods described previously (72), 100 μL of 1% NP-40 was added as the samples were agitated by vortexing. NP-40-treated samples were overlaid onto 1 mL of 1 M sucrose dissolved in buffer B. After centrifugation at 3,100 × g at 4°C for 10 min, 200 μL of the supernatant was collected as the cytosolic fraction. The remaining supernatant was removed, and the pellet of nuclei was washed with buffer B four times and then resuspended in 1 mL of buffer B. Two hundred microliters of the resuspended nuclei was collected as the nuclear fraction. An equal volume of 2× Laemmli buffer was added to the cytosolic and nuclear fractions. The cytosolic and nuclear lysates were heated to 94°C for 30 min prior to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis. Samples were probed for GAPDH (anti-GAPDH, catalog no. 5174; Cell Signaling Technology) and histone H3 (anti-histone H3, catalog no. 9715; Cell Signaling Technology) to confirm the purity of the cytosolic and nuclear fractions, respectively.

Statistics.

Two-sample, two-tailed, parametric Student’s t test was used for all statistical analyses. Student’s t test was used to determine whether differences between a data set for DMSO (solvent)-treated samples and a data set for samples treated with a specific micromolar concentration of SFN were statistically significant. Student’s t tests were performed using Microsoft Excel.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Binshan Shi, Vir Singh, Timothy LaRocca, and Robert Bautz at the Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences for sharing reagents and insight and for laboratory assistance.

We declare that we have no competing interests.

H.J.S. wrote the manuscript. H.J.S., D.N.P., V.A.F., and C.M.C.D.N. conceived and performed experiments. A.F.T. and E.P. performed experiments.

This work was funded by NIH grant AI140993 to C.M.C.D.N.

Contributor Information

Carlos M. C. de Noronha, Email: denoroc@amc.edu.

Guido Silvestri, Emory University.

REFERENCES

- 1.Dinkova-Kostova AT, Fahey JW, Kostov RV, Kensler TW. 2017. KEAP1 and done? Targeting the NRF2 pathway with sulforaphane. Trends Food Sci Technol 69:257–269. 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Furuya AKM, Sharifi HJ, Jellinger RM, Cristofano P, Shi B, de Noronha CMC. 2016. Sulforaphane inhibits HIV infection of macrophages through Nrf2. PLoS Pathog 12:e1005581. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rabinowitz J, Sharifi HJ, Martin H, Marchese A, Robek M, Shi B, Mongin AA, de Noronha CMC. 2021. xCT/SLC7A11 antiporter function inhibits HIV-1 infection. Virology 556:149–160. 10.1016/j.virol.2021.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olagnier D, Farahani E, Thyrsted J, Blay-Cadanet J, Herengt A, Idorn M, Hait A, Hernaez B, Knudsen A, Iversen MB, Schilling M, Jørgensen SE, Thomsen M, Reinert LS, Lappe M, Hoang H-D, Gilchrist VH, Hansen AL, Ottosen R, Nielsen CG, Møller C, van der Horst D, Peri S, Balachandran S, Huang J, Jakobsen M, Svenningsen EB, Poulsen TB, Bartsch L, Thielke AL, Luo Y, Alain T, Rehwinkel J, Alcamí A, Hiscott J, Mogensen TH, Paludan SR, Holm CK. 2020. SARS-CoV2-mediated suppression of NRF2-signaling reveals potent antiviral and anti-inflammatory activity of 4-octyl-itaconate and dimethyl fumarate. Nat Commun 11:4938. 10.1038/s41467-020-18764-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gunderstofte C, Iversen MB, Peri S, Thielke A, Balachandran S, Holm CK, Olagnier D. 2019. Nrf2 negatively regulates type I interferon responses and increases susceptibility to herpes genital infection in mice. Front Immunol 10:2101. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hrecka K, Hao C, Gierszewska M, Swanson SK, Kesik-Brodacka M, Srivastava S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Skowronski J. 2011. Vpx relieves inhibition of HIV-1 infection of macrophages mediated by the SAMHD1 protein. Nature 474:658–661. 10.1038/nature10195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Laguette N, Sobhian B, Casartelli N, Ringeard M, Chable-Bessia C, Ségéral E, Yatim A, Emiliani S, Schwartz O, Benkirane M. 2011. SAMHD1 is the dendritic- and myeloid-cell-specific HIV-1 restriction factor counteracted by Vpx. Nature 474:654–657. 10.1038/nature10117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baldauf H-M, Pan X, Erikson E, Schmidt S, Daddacha W, Burggraf M, Schenkova K, Ambiel I, Wabnitz G, Gramberg T, Panitz S, Flory E, Landau NR, Sertel S, Rutsch F, Lasitschka F, Kim B, König R, Fackler OT, Keppler OT. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in resting CD4(+) T cells. Nat Med 18:1682–1687. 10.1038/nm.2964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.White TE, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, Amie S, Nguyen LA, Kim B, Tuzova M, Diaz-Griffero F. 2013. The retroviral restriction ability of SAMHD1, but not its deoxynucleotide triphosphohydrolase activity, is regulated by phosphorylation. Cell Host Microbe 13:441–451. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cribier A, Descours B, Valadao AL, Laguette N, Benkirane M. 2013. Phosphorylation of SAMHD1 by cyclin A2/CDK1 regulates its restriction activity toward HIV-1. Cell Rep 3:1036–1043. 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahouassa H, Daddacha W, Hofmann H, Ayinde D, Logue EC, Dragin L, Bloch N, Maudet C, Bertrand M, Gramberg T, Pancino G, Priet S, Canard B, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Transy C, Landau NR, Kim B, Margottin-Goguet F. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts the replication of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by depleting the intracellular pool of deoxynucleoside triphosphates. Nat Immunol 13:223–228. 10.1038/ni.2236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Welbourn S, Strebel K. 2016. Low dNTP levels are necessary but may not be sufficient for lentiviral restriction by SAMHD1. Virology 488:271–277. 10.1016/j.virol.2015.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pauls E, Ruiz A, Badia R, Permanyer M, Gubern A, Riveira-Muñoz E, Torres-Torronteras J, Alvarez M, Mothe B, Brander C, Crespo M, Menéndez-Arias L, Clotet B, Keppler OT, Martí R, Posas F, Ballana E, Esté JA. 2014. Cell cycle control and HIV-1 susceptibility are linked by CDK6-dependent CDK2 phosphorylation of SAMHD1 in myeloid and lymphoid cells. J Immunol 193:1988–1997. 10.4049/jimmunol.1400873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tang C, Ji X, Wu L, Xiong Y. 2015. Impaired dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 by phosphomimetic mutation of Thr-592. J Biol Chem 290:26352–26359. 10.1074/jbc.M115.677435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan J, Hao C, DeLucia M, Swanson S, Florens L, Washburn MP, Ahn J, Skowronski J. 2015. CyclinA2-cyclin-dependent kinase regulates SAMHD1 protein phosphohydrolase domain. J Biol Chem 290:13279–13292. 10.1074/jbc.M115.646588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schott K, Fuchs NV, Derua R, Mahboubi B, Schnellbächer E, Seifried J, Tondera C, Schmitz H, Shepard C, Brandariz-Nuñez A, Diaz-Griffero F, Reuter A, Kim B, Janssens V, König R. 2018. Dephosphorylation of the HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1 is mediated by PP2A-B55α holoenzymes during mitotic exit. Nat Commun 9:2227. 10.1038/s41467-018-04671-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pauls E, Ruiz A, Riveira-Muñoz E, Permanyer M, Badia R, Clotet B, Keppler OT, Ballana E, Este JA. 2014. p21 regulates the HIV-1 restriction factor SAMHD1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111:E1322–E1324. 10.1073/pnas.1322059111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Valle-Casuso JC, Allouch A, David A, Lenzi GM, Studdard L, Barré-Sinoussi F, Müller-Trutwin M, Kim B, Pancino G, Sáez-Cirión A. 2017. p21 restricts HIV-1 in monocyte-derived dendritic cells through the reduction of deoxynucleoside triphosphate biosynthesis and regulation of SAMHD1 antiviral activity. J Virol 91:e01324-17. 10.1128/JVI.01324-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Osei Kuffour E, Schott K, Jaguva Vasudevan AA, Holler J, Schulz WA, Lang PA, Lang KS, Kim B, Häussinger D, König R, Münk C. 2018. USP18 (UBP43) abrogates p21-mediated inhibition of HIV-1. J Virol 92:e00592-18. 10.1128/JVI.00592-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi B, Sharifi HJ, DiGrigoli S, Kinnetz M, Mellon K, Hu W, de Noronha CMC. 2018. Inhibition of HIV early replication by the p53 and its downstream gene p21. Virol J 15:53. 10.1186/s12985-018-0959-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mauney CH, Rogers LC, Harris RS, Daniel LW, Devarie-Baez NO, Wu H, Furdui CM, Poole LB, Perrino FW, Hollis T. 2017. The SAMHD1 dNTP triphosphohydrolase is controlled by a redox switch. Antioxid Redox Signal 27:1317–1331. 10.1089/ars.2016.6888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang Z, Bhattacharya A, White T, Buffone C, McCabe A, Nguyen LA, Shepard CN, Pardo S, Kim B, Weintraub ST, Demeler B, Diaz-Griffero F, Ivanov DN. 2018. Functionality of redox-active cysteines is required for restriction of retroviral replication by SAMHD1. Cell Rep 24:815–823. 10.1016/j.celrep.2018.06.090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patra KK, Bhattacharya A, Bhattacharya S. 2019. Molecular dynamics investigation of a redox switch in the anti-HIV protein SAMHD1. Proteins 87:748–759. 10.1002/prot.25701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kane M, Yadav SS, Bitzegeio J, Kutluay SB, Zang T, Wilson SJ, Schoggins JW, Rice CM, Yamashita M, Hatziioannou T, Bieniasz PD. 2013. MX2 is an interferon-induced inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature 502:563–566. 10.1038/nature12653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu Z, Pan Q, Ding S, Qian J, Xu F, Zhou J, Cen S, Guo F, Liang C. 2013. The interferon-inducible MxB protein inhibits HIV-1 infection. Cell Host Microbe 14:398–410. 10.1016/j.chom.2013.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goujon C, Moncorgé O, Bauby H, Doyle T, Ward CC, Schaller T, Hué S, Barclay WS, Schulz R, Malim MH. 2013. Human MX2 is an interferon-induced post-entry inhibitor of HIV-1 infection. Nature 502:559–562. 10.1038/nature12542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bonifati S, Daly MB, St Gelais C, Kim SH, Hollenbaugh JA, Shepard C, Kennedy EM, Kim D-H, Schinazi RF, Kim B, Wu L. 2016. SAMHD1 controls cell cycle status, apoptosis and HIV-1 infection in monocytic THP-1 cells. Virology 495:92–100. 10.1016/j.virol.2016.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruhee RT, Suzuki K. 2020. The integrative role of sulforaphane in preventing inflammation, oxidative stress and fatigue: a review of a potential protective phytochemical. Antioxidants (Basel) 9:521. 10.3390/antiox9060521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martinez-Lopez A, Martin-Fernandez M, Buta S, Kim B, Bogunovic D, Diaz-Griffero F. 2018. SAMHD1 deficient human monocytes autonomously trigger type I interferon. Mol Immunol 101:450–460. 10.1016/j.molimm.2018.08.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahn J, Hao C, Yan J, DeLucia M, Mehrens J, Wang C, Gronenborn AM, Skowronski J. 2012. HIV/simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) accessory virulence factor Vpx loads the host cell restriction factor SAMHD1 onto the E3 ubiquitin ligase complex CRL4DCAF1. J Biol Chem 287:12550–12558. 10.1074/jbc.M112.340711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.St Gelais C, de Silva S, Hach JC, White TE, Diaz-Griffero F, Yount JS, Wu L. 2014. Identification of cellular proteins interacting with the retroviral restriction factor SAMHD1. J Virol 88:5834–5844. 10.1128/JVI.00155-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu J, Qiao M, Chen Y, Tang H, Zhang W, Tang D, Pi S, Dai J, Tang N, Huang A, Hu Y. 2018. Cyclin E2-CDK2 mediates SAMHD1 phosphorylation to abrogate its restriction of HBV replication in hepatoma cells. FEBS Lett 592:1893–1904. 10.1002/1873-3468.13105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Szaniawski MA, Spivak AM, Cox JE, Catrow JL, Hanley T, Williams ESCP, Tremblay MJ, Bosque A, Planelles V. 2018. SAMHD1 phosphorylation coordinates the anti-HIV-1 response by diverse interferons and tyrosine kinase inhibition. mBio 9(3):e00819-18. 10.1128/mBio.00819-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Han D, Gu X, Gao J, Wang Z, Liu G, Barkema HW, Han B. 2019. Chlorogenic acid promotes the Nrf2/HO-1 anti-oxidative pathway by activating p21(Waf1/Cip1) to resist dexamethasone-induced apoptosis in osteoblastic cells. Free Radic Biol Med 137:1–12. 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2019.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nakano-Kobayashi A, Fukumoto A, Morizane A, Nguyen DT, Le TM, Hashida K, Hosoya T, Takahashi R, Takahashi J, Hori O, Hagiwara M. 2020. Therapeutics potentiating microglial p21-Nrf2 axis can rescue neurodegeneration caused by neuroinflammation. Sci Adv 6:eabc1428. 10.1126/sciadv.abc1428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Silva-Islas CA, Maldonado PD. 2018. Canonical and non-canonical mechanisms of Nrf2 activation. Pharmacol Res 134:92–99. 10.1016/j.phrs.2018.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Villeneuve NF, Sun Z, Chen W, Zhang DD. 2009. Nrf2 and p21 regulate the fine balance between life and death by controlling ROS levels. Cell Cycle 8:3255–3256. 10.4161/cc.8.20.9565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen W, Sun Z, Wang X-J, Jiang T, Huang Z, Fang D, Zhang DD. 2009. Direct interaction between Nrf2 and p21(Cip1/WAF1) upregulates the Nrf2-mediated antioxidant response. Mol Cell 34:663–673. 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.04.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hernández-Rabaza V, Cabrera-Pastor A, Taoro-González L, Malaguarnera M, Agustí A, Llansola M, Felipo V. 2016. Hyperammonemia induces glial activation, neuroinflammation and alters neurotransmitter receptors in hippocampus, impairing spatial learning: reversal by sulforaphane. J Neuroinflammation 13:41. 10.1186/s12974-016-0505-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pal S, Konkimalla VB. 2016. Sulforaphane regulates phenotypic and functional switching of both induced and spontaneously differentiating human monocytes. Int Immunopharmacol 35:85–98. 10.1016/j.intimp.2016.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadl A, Meher AK, Sharma PR, Lee MY, Doran AC, Johnstone SR, Elliott MR, Gruber F, Han J, Chen W, Kensler T, Ravichandran KS, Isakson BE, Wamhoff BR, Leitinger N. 2010. Identification of a novel macrophage phenotype that develops in response to atherogenic phospholipids via Nrf2. Circ Res 107:737–746. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.215715. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rackov G, Hernández-Jiménez E, Shokri R, Carmona-Rodríguez L, Mañes S, Álvarez-Mon M, López-Collazo E, Martínez-A C, Balomenos D. 2016. p21 mediates macrophage reprogramming through regulation of p50-p50 NF-κB and IFN-β. J Clin Invest 126:3089–3103. 10.1172/JCI83404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lu M-C, Ji J-A, Jiang Z-Y, You Q-D. 2016. The Keap1-Nrf2-ARE pathway as a potential preventive and therapeutic target: an update. Med Res Rev 36:924–963. 10.1002/med.21396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mills EL, Ryan DG, Prag HA, Dikovskaya D, Menon D, Zaslona Z, Jedrychowski MP, Costa ASH, Higgins M, Hams E, Szpyt J, Runtsch MC, King MS, McGouran JF, Fischer R, Kessler BM, McGettrick AF, Hughes MM, Carroll RG, Booty LM, Knatko EV, Meakin PJ, Ashford MLJ, Modis LK, Brunori G, Sévin DC, Fallon PG, Caldwell ST, Kunji ERS, Chouchani ET, Frezza C, Dinkova-Kostova AT, Hartley RC, Murphy MP, O’Neill LA. 2018. Itaconate is an anti-inflammatory metabolite that activates Nrf2 via alkylation of KEAP1. Nature 556:113–117. 10.1038/nature25986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tang C, Wang X, Xie Y, Cai X, Yu N, Hu Y, Zheng Z. 2018. 4-Octyl itaconate activates Nrf2 signaling to inhibit pro-inflammatory cytokine production in peripheral blood mononuclear cells of systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Cell Physiol Biochem 51:979–990. 10.1159/000495400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cross SA, Cook DR, Chi AWS, Vance PJ, Kolson LL, Wong BJ, Jordan-Sciutto KL, Kolson DL. 2011. Dimethyl fumarate, an immune modulator and inducer of the antioxidant response, suppresses HIV replication and macrophage-mediated neurotoxicity: a novel candidate for HIV neuroprotection. J Immunol 187:5015–5025. 10.4049/jimmunol.1101868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yan J, Kaur S, DeLucia M, Hao C, Mehrens J, Wang C, Golczak M, Palczewski K, Gronenborn AM, Ahn J, Skowronski J. 2013. Tetramerization of SAMHD1 is required for biological activity and inhibition of HIV infection. J Biol Chem 288:10406–10417. 10.1074/jbc.M112.443796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Z, Bhattacharya A, Villacorta J, Diaz-Griffero F, Ivanov DN. 2016. Allosteric activation of SAMHD1 protein by deoxynucleotide triphosphate (dNTP)-dependent tetramerization requires dNTP concentrations that are similar to dNTP concentrations observed in cycling T cells. J Biol Chem 291:21407–21413. 10.1074/jbc.C116.751446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hofmann H, Logue EC, Bloch N, Daddacha W, Polsky SB, Schultz ML, Kim B, Landau NR. 2012. The Vpx lentiviral accessory protein targets SAMHD1 for degradation in the nucleus. J Virol 86:12552–12560. 10.1128/JVI.01657-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brandariz-Nuñez A, Valle-Casuso JC, White TE, Laguette N, Benkirane M, Brojatsch J, Diaz-Griffero F. 2012. Role of SAMHD1 nuclear localization in restriction of HIV-1 and SIVmac. Retrovirology 9:49. 10.1186/1742-4690-9-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Qin Z, Bonifati S, St Gelais C, Li T-W, Kim S-H, Antonucci JM, Mahboubi B, Yount JS, Xiong Y, Kim B, Wu L. 2020. The dNTPase activity of SAMHD1 is important for its suppression of innate immune responses in differentiated monocytic cells. J Biol Chem 295:1575–1586. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.010360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Batalis S, Rogers LC, Hemphill WO, Mauney CH, Ornelles DA, Hollis T. 2021. SAMHD1 phosphorylation at T592 regulates cellular localization and S-phase progression. Front Mol Biosci 8:724870. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.724870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sharifi HJ, Furuya AKM, Jellinger RM, Nekorchuk MD, de Noronha CMC. 2014. Cullin4A and cullin4B are interchangeable for HIV Vpr and Vpx action through the CRL4 ubiquitin ligase complex. J Virol 88:6944–6958. 10.1128/JVI.00241-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang C, Meng L, Wang J, Zhang K, Duan S, Ren P, Wei Y, Fu X, Yu B, Wu J, Yu X. 2021. Role of intracellular distribution of feline and bovine SAMHD1 proteins in lentiviral restriction. Virol Sin 36:981–996. 10.1007/s12250-021-00351-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Raman D, Pervaiz S. 2019. Redox inhibition of protein phosphatase PP2A: potential implications in oncogenesis and its progression. Redox Biol 27:101105. 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.St Gelais C, de Silva S, Amie SM, Coleman CM, Hoy H, Hollenbaugh JA, Kim B, Wu L. 2012. SAMHD1 restricts HIV-1 infection in dendritic cells (DCs) by dNTP depletion, but its expression in DCs and primary CD4+ T-lymphocytes cannot be upregulated by interferons. Retrovirology 9:105. 10.1186/1742-4690-9-105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ruiz A, Pauls E, Badia R, Torres-Torronteras J, Riveira-Muñoz E, Clotet B, Martí R, Ballana E, Esté JA. 2015. Cyclin D3-dependent control of the dNTP pool and HIV-1 replication in human macrophages. Cell Cycle 14:1657–1665. 10.1080/15384101.2015.1030558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Opp S, Vieira DASA, Schulte B, Chanda SK, Diaz-Griffero F. 2016. MxB is not responsible for the blocking of HIV-1 infection observed in alpha interferon-treated cells. J Virol 90:3056–3064. 10.1128/JVI.03146-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Reinhard C, Bottinelli D, Kim B, Luban J. 2014. Vpx rescue of HIV-1 from the antiviral state in mature dendritic cells is independent of the intracellular deoxynucleotide concentration. Retrovirology 11:12. 10.1186/1742-4690-11-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bloch N, O’Brien M, Norton TD, Polsky SB, Bhardwaj N, Landau NR. 2014. HIV type 1 infection of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells is restricted by high levels of SAMHD1 and cannot be counteracted by Vpx. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses 30:195–203. 10.1089/AID.2013.0119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fletcher TM, III, Brichacek B, Sharova N, Newman MA, Stivahtis G, Sharp PM, Emerman M, Hahn BH, Stevenson M. 1996. Nuclear import and cell cycle arrest functions of the HIV-1 Vpr protein are encoded by two separate genes in HIV-2/SIV(SM). EMBO J 15:6155–6165. 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1996.tb01003.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cheng X, Belshan M, Ratner L. 2008. Hsp40 facilitates nuclear import of the human immunodeficiency virus type 2 Vpx-mediated preintegration complex. J Virol 82:1229–1237. 10.1128/JVI.00540-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Sharova N, Wu Y, Zhu X, Stranska R, Kaushik R, Sharkey M, Stevenson M. 2008. Primate lentiviral Vpx commandeers DDB1 to counteract a macrophage restriction. PLoS Pathog 4:e1000057. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Coquel F, Silva M-J, Técher H, Zadorozhny K, Sharma S, Nieminuszczy J, Mettling C, Dardillac E, Barthe A, Schmitz A-L, Promonet A, Cribier A, Sarrazin A, Niedzwiedz W, Lopez B, Costanzo V, Krejci L, Chabes A, Benkirane M, Lin Y-L, Pasero P. 2018. SAMHD1 acts at stalled replication forks to prevent interferon induction. Nature 557:57–61. 10.1038/s41586-018-0050-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Herrmann A, Wittmann S, Thomas D, Shepard CN, Kim B, Ferreirós N, Gramberg T. 2018. The SAMHD1-mediated block of LINE-1 retroelements is regulated by phosphorylation. Mob DNA 9:11. 10.1186/s13100-018-0116-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Antonucci JM, Kim SH, St Gelais C, Bonifati S, Li T-W, Buzovetsky O, Knecht KM, Duchon AA, Xiong Y, Musier-Forsyth K, Wu L. 2018. SAMHD1 impairs HIV-1 gene expression and negatively modulates reactivation of viral latency in CD4+ T cells. J Virol 92:e00292-18. 10.1128/JVI.00292-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yu CH, Bhattacharya A, Persaud M, Taylor AB, Wang Z, Bulnes-Ramos A, Xu J, Selyutina A, Martinez-Lopez A, Cano K, Demeler B, Kim B, Hardies SC, Diaz-Griffero F, Ivanov DN. 2021. Nucleic acid binding by SAMHD1 contributes to the antiretroviral activity and is enhanced by the GpsN modification. Nat Commun 12:731. 10.1038/s41467-021-21023-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barrett B, Nguyen DH, Xu J, Guo K, Shetty S, Jones ST, Mickens KL, Shepard C, Roers A, Behrendt R, Wu L, Kim B, Santiago ML. 2022. SAMHD1 promotes the antiretroviral adaptive immune response in mice exposed to lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol 208:444–453. 10.4049/jimmunol.2001389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mlcochova P, Winstone H, Zuliani-Alvarez L, Gupta RK. 2020. TLR4-mediated pathway triggers interferon-independent G0 arrest and antiviral SAMHD1 activity in macrophages. Cell Rep 30:3972–3980.e5. 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Maehara N, Ho M. 1977. Cellular origin of interferon induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun 15:78–83. 10.1128/iai.15.1.78-83.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Ryan DG, Knatko EV, Casey AM, Hukelmann JL, Dayalan Naidu S, Brenes AJ, Ekkunagul T, Baker C, Higgins M, Tronci L, Nikitopolou E, Honda T, Hartley RC, O’Neill LAJ, Frezza C, Lamond AI, Abramov AY, Arthur JSC, Cantrell DA, Murphy MP, Dinkova-Kostova AT. 2022. Nrf2 activation reprograms macrophage intermediary metabolism and suppresses the type I interferon response. iScience 25:103827. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schreiber E, Matthias P, Müller MM, Schaffner W. 1989. Rapid detection of octamer binding proteins with ‘mini-extracts’, prepared from a small number of cells. Nucleic Acids Res 17:6419. 10.1093/nar/17.15.6419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]