Abstract

Black carbon (BC), an important indicator of traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) in urban environments, is receiving increased attention because of its adverse health effects. Personal exposure (PE) of adults to BC has been widely studied, but little is known about the exposure of young children (toddlers) to BC in cities. We carried out a pilot study to investigate the integrated daily PE of toddlers to BC in a city-state with a high population density (Singapore). We studied the impact of urban traffic on the PE of toddlers to BC by comparing and contrasting on-road traffic flow (i.e., volume and composition) in Singapore in 2019 (before the COVID-19 pandemic) and in 2020 (during the COVID-19 pandemic). Our observations indicate that the daily BC exposure levels and inhaled doses increased by about 25% in 2020 (2.9 ± 0.3 μg m−3 and 35.5 μg day−1) compared to that in 2019 (2.3 ± 0.4 μg m−3 and 28.5 μg day−1 for exposure concentration and inhaled dose, respectively). The increased BC levels were associated with the increased traffic volume on both weekdays and weekends in 2020 compared to the same time period in 2019. Specifically, we observed an increase in the number of trucks as well as cars/taxis and motorcycles (private transport) and a decline in the number of buses (public transport) in 2020. The implementation of lockdown measures in 2020 resulted in significant changes in the time, place and duration of PE of toddlers to BC. The recorded daily time-activity patterns indicated that toddlers spent almost all the time in indoor environments during the measurement period in 2020. When we compared different ventilation options (natural ventilation (NV), air conditioning (AC), and portable air cleaner (PAC)) for mitigation of PE to BC in the home environment, we found a significant decrease (>30%) in daily BC exposure levels while using the PAC compared to the NV scenario. Our case study shows that the PE of toddlers to BC is of health concern in indoor environments in 2020 because of the migration of the increased TRAP into naturally ventilated residential homes and more time spent indoors than outdoors. Since toddlers’ immune system is weak, technological intervention is necessary to protect their health against inhalation exposure to air pollutants.

Keywords: Black carbon, Personal exposure, Mitigation, Traffic, COVID-19

Abbreviations: BC, black carbon; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CB, circuit breaker; GM, geometric mean; PE, personal exposure; PM, particulate matter; ME, microenvironment; NV, natural ventilation; AC, air conditioning; PAC, portable air cleaner; TRAP, traffic-related air pollution; OD, outdoor; UFP, ultrafine particles

Graphical abstract

1. Introduction

Black carbon (BC), a major component of fine particulate matter (PM2.5, ≤ 2.5 μm in diameter), is primarily emitted from the incomplete combustion of biomass and oil/diesel (Bond et al., 2013; Vivanco-Hidalgo et al., 2018). BC concentrations are particularly pronounced in urban environments, leading to potentially elevated inhalation exposure to BC among urban dwellers (Dons et al., 2011; Li et al., 2015). A major source of BC in cities is vehicular traffic, especially from diesel engines (Targino et al., 2016; Tran et al., 2020a). Several studies have shown a strong association between pronounced exposure levels of BC (and related co-emissions of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons - PAHs) and adverse health impacts such as decreased cognitive function, respiratory ailments, cardiovascular diseases, and lung cancer (Grahame et al., 2014; Janssen et al., 2011; Lin et al., 2019; Niranjan and Thakur, 2017; Suglia et al., 2008). Among members of the public, young children, especially those less than 5 years old (comprising about 8.8% of the total of the world's population in 2019 (United Nations, 2019)) are particularly vulnerable to negative health effects of personal exposure (PE) to BC such as decreased cognitive function (Freire et al., 2010; Suglia et al., 2008) and neurodevelopment (Alemany et al., 2018; Perera, 2017). Furthermore, young children might experience chronic diseases later in their life because of higher inhaled doses relative to their lung size and body weight and immature immune system, lungs, tissues and brain compared to older children and adults (Buonanno et al., 2013; Sharma and Kumar, 2018; WHO, 2005; Yolton et al., 2019). It is, therefore, imperative to assess the PE levels of young children to BC in order to mitigate their exposure to BC and minimize potential health impacts.

Children in the age group of 7–14 years have been the focus of several air quality PE studies in recent years (e.g., Cunha-Lopes et al., 2019; Jeong and Park, 2018; Jung et al., 2017). The findings indicate that their inhalation dose of PM2.5 and BC is high (up to 83%) in indoor microenvironments (MEs) within schools and homes (Cunha-Lopes et al., 2019; Jeong and Park, 2017a, b; Paunescu et al., 2017; Rivas et al., 2016) as the children spend a substantial amount of their time in indoors. In addition, they are exposed to pronounced short-term peaks in BC in transport environments while commuting to schools from their home and back (Cunha-Lopes et al., 2019; Jeong and Park, 2018; Rivas et al., 2016). It has been reported that toddlers (1–3 years old) could receive up to ~ 60% higher PE to air pollutants (e.g., PM2.5) than adults (Sharma and Kumar, 2018). The breathing height of toddlers is lower, ranging between 0.55 m and 0.85 m above the ground level, compared to older children. The breathing height depends on whether toddlers sit in a stroller or walk around. The PE of toddlers to PM emissions of vehicular traffic origin (Kumar et al., 2017) at a lower height is of serious health concern (Goel and Kumar, 2016). Also, they have distinct time-activity patterns and hence their PE is different from that of older children (Conrad et al., 2013; Fees et al., 2015; Wu et al., 2011). Limited previous studies on toddlers mainly focused on their PE to PM of different sizes (ultrafine particles - UFP, PM1, PM2.5, PM10) of vehicular traffic origin while on commuting with short-term exposure to elevated concentrations of PM (Buzzard et al., 2009; Galea et al., 2014; Kumar et al., 2017; Sharma and Kumar, 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, no study has examined the integrated PE of toddlers to BC over 24 h and its spatio-temporal variations across outdoor and indoor microenvironments (MEs). Continuous measurement of toddlers’ PE to specific pollutants of emerging concern such as BC across different MEs will provide a basis for identifying where and how their exposure can be reduced (Assimakopoulos et al., 2018; Sharma and Kumar, 2018), so that appropriate mitigation strategies can be recommended to ensure their well-being.

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) global pandemic brought drastic changes in time-activity and lifestyle patterns on a day-to-day basis among city dwellers due to implementation of lockdown measures to contain the spread of the outbreak. These changes affected their integrated PE to air pollutants over 24 h because of reduction in the levels of outdoor air pollutants (Bao and Zhang, 2020; Bekbulat et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020b; Kumar et al., 2020; Sharma and Kumar, 2020; Venter et al., 2021) and increased presence of city dwellers in their home environments (Domínguez-Amarillo et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2020; Nwanaji-Enwerem et al., 2020). Primary (i.e., direct) emissions of UFP (PM with diameter < 100 nm) and BC of traffic origin also decreased significantly due to a reduction in the number of on-road vehicles, especially passenger cars, in cities (Hudda et al., 2020). However, there was a notable change in the composition of on-road vehicles in 2020 during the COVID-19 period. For example, Hudda et al. (2020) reported a higher fraction of diesel-powered vehicles such as pick-up trucks and cargo vans during the lockdown compared to pre-lockdown periods because of the supply of essential services such as consumer goods deliveries, which in turn resulted in a higher ratio of BC to particle counts. Another notable change is that the PE to indoor PM2.5 levels was reported to have increased during the COVID-19 period due to the increased time spent at home and more frequent and intense indoor activities such as cleaning and cooking (Domínguez-Amarillo et al., 2020). In view of these changes in time-activity and lifestyle patterns, it is important to study the influence of COVID-19 pandemic on the PE of toddlers to air pollutants, given that they cannot wear face masks unlike older children and adults.

This pilot study was conducted to assess and mitigate the PE of toddlers in general to BC, a pollutant of emerging health concern, in Singapore, a densely populated city-state with intense human activities. The study took place during July and August in 2019 (pre-COVID-19 period) and during the same time period in 2020 (during the COVID-19 period). The BC measurements were made using a microaethalometer over 24 h across diverse microenvironments (home, and non-home microenvironments) in 2019, but in mostly home environments in 2020. We estimated the contribution of each ME to the daily BC exposure. In addition, we assessed the effectiveness of BC exposure mitigation measures under different ventilation conditions in the home environment. The findings of this study provide insights into the role of COVID-19-induced air quality changes on the PE of toddlers to BC in dense cities and can be used to devise control strategies to protect toddlers’ health from the harmful effects of air pollution in cities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Site description and experimental design

The integrated PE to BC was carried out in the south-western region of Singapore from July to August in 2019 and 2020 (see Table 1 ). Singapore is one of the most highly urbanized and densely populated city-states in the world (7804 people km− 2 within 722.5 km2 territory) (Department of Statistics Singapore, 2019). Traffic emission is a major source of air pollutants on the island accounting for about 56% of PM2.5 emissions (Zhang et al., 2017), raising concerns about the exposure to traffic-related air pollution (TRAP) for the local residents living near streets or highways (Sharma and Balasubramanian, 2019; Tran et al., 2020b). Its urban traffic fleet is characterized by a relatively high rate of in-use diesel vehicles (about 18.8% of the total motor vehicle population of 949,053), which substantially contribute to high emissions of BC in urban areas (LTA, 2020). There is no significant change (about +1.1%) in the total motor vehicle population in Singapore between 2019 and 2020.

Table 1.

Summary of meteorological conditions during the field studya.

| Date | Ambient air temperature (oC) | Daily Total Rainfall (mm) | Mean Wind speed (km h−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24-7-2019 | 27.7 | 2.4 | 9.0 |

| 25-7-2019 | 28.5 | 0.0 | 9.0 |

| 26-7-2019 | 28.6 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| 27-7-2019 | 28.9 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| 28-7-2019 | 28.7 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| 29-7-2019 | 29.2 | 0.0 | 10.1 |

| 13-8-2019 | 29.0 | 0.0 | 9.7 |

| 14-8-2019 | 29.1 | 0.0 | 9.7 |

| 15-8-2019 | 28.8 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| 16-8-2019 | 29.2 | 0.0 | 10.8 |

| 16-7-2020 | 28.2 | 0.0 | 8.3 |

| 17-7-2020 | 29.0 | 0.0 | 8.3 |

| 18-7-2020 | 28.1 | 0.0 | 7.9 |

| 19-7-2020 | 28.4 | 0.0 | 9.4 |

| 22-8-2020 | 27.6 | 3.4 | 8.6 |

| 23-8-2020 | 27.8 | 3.0 | 7.6 |

| 24-8-2020 | 27.4 | 1.3 | 8.5 |

| 25-8-2020 | 26.6 | 7.6 | 8.7 |

| 26-8-2020 | 27.0 | 4.4 | 9.0 |

| 27-8-2020 | 27.9 | 0.0 | 10.6 |

| 28-8-2020 | 28.5 | 0.0 | 13.5 |

Data was obtained from http://www.weather.gov.sg/climate-historical-daily.

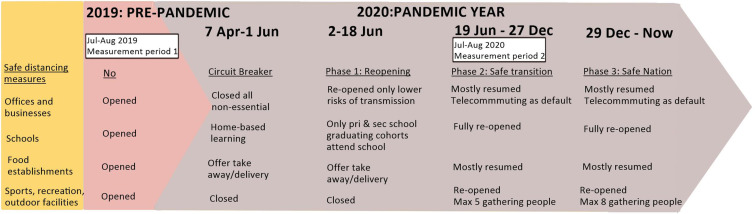

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Singapore implemented lockdown measures referred to as “circuit breaker” (CB), from 7 April to June 1, 2020, to curb the spread of the virus within the local community. During the CB period, all non-essential offices and businesses were closed, schools were transitioned to home-based learning, and food establishments were only allowed to offer take-away and delivery (Li and Tartarini, 2020; Lim et al., 2020). From June 1, 2020, Singapore migrated to the post-CB period with the resumption of routine activities, introduced cautiously in three phases (see Fig. 1 ). Our PE monitoring campaign was initially carried out from July to August 2019 (i.e., before the COVID-19 pandemic), which was then repeated in 2020 during the same time period (i.e., during the COVID-19 pandemic). Singapore was in phase 2 (safe transition) during the PE measurement campaign in 2020 when the entire local economy-related activities were almost resumed. However, telecommuting still continued to be the default option for the workforce. People were allowed to go out for limited outdoor activities such as physical exercise, shopping and recreation, but were restricted to a group size of no more than 5 persons at a time. Most of the public play areas designated for children were still kept closed. The overall aim of the PE assessment was to examine how the COVID-19 pandemic-related time-activity patterns influenced the PE to BC, compared to the pre-COVID-19 time period in 2019, especially when urban mobility restrictions were relaxed.

Fig. 1.

Overview of measurement timeline and safe distancing measures in Singapore.

A 2-year-old toddler was involved in this pilot study under the supervision of an adult. The child lived in a residential home (non-smoking household) on a low storey of a typical multi-storey naturally ventilated residential building situated near a major road that carries a large volume of vehicles in the south-western area of Singapore. During the first measurement period in 2019, the toddler's exposure to BC was monitored across several urban MEs (home and non-home MEs including restaurants, play areas, as well as transport-MEs). In contrast, the toddler mostly stayed at home in 2020. A detailed description of each ME is provided in Table 2 . The toddler was always seated in a stroller (a foldable 4-wheeler stroller with 103 cm height, 70 cm width and 5 kg weight) while commuting by different modes of transport (walking, bus, mass rapid transport - MRT) with the exception of being seated on an elevated platform (about 1 m) while co-riding an adult bicycle. To assess the effect of commonly maintained ventilation conditions in tropical residential apartments on the exposure of the toddler to BC, three exposure scenarios with different ventilation and intervention settings (natural ventilation – NV, air conditioning – AC and portable air cleaner + fan – PAC) were explored in a bedroom (3.5 m × 3.0 m × 2.4 m) in the home ME during the sleeping time (from 12:00 to 13:30, and from 21:30 to 8:00). Table 3 provides detailed characteristics and operation settings of the AC and PAC used.

Table 2.

Characteristics of micro-environments involved in the study.

| Micro-environment | Measuring period | Activity | Description and location | Ventilation and mitigation conditions | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home | Outdoor | 24 h | – | Balcony of the living room on the low storey of a multi-storey residential building, at ≈100 m distance from a major road | Ambient air conditions | |

| NV-SL | From 12:00 to 13:30 and from 21:30 to 8:00 | Sleeping | Bedroom | Windows opened | ||

| AC-SL | Windows closed, cooling by the air-conditioning system with recirculation mode | |||||

| PAC-SL | Windows closed, using a portable air cleaner + Fan | |||||

| NV-Others | Times other than sleeping at home and going out | Eating, playing, personal hygiene | Living room and bedroom | Windows opened | ||

| Non-home | Play areas | Rooftop 1 | 9:30–10:00 | Playing, running, climbing, etc. | Play area on a rooftop of a community centre at ≈ 50 m distance from a minor road | Ambient air conditions |

| Rooftop 2 | 9:30–10:00 | Play area on a rooftop of a shopping mall in ≈100 m from a major road | Ambient air conditions | |||

| 17:00–18:00 | ||||||

| Ground 1 | 9:00–9:30 | Playground at ≈100 m distance from a minor road | Ambient air conditions | |||

| 16:55–17:50 | ||||||

| Ground 2 | 9:00–9:30 | Playground at ≈100 m distance from a major road | Ambient air conditions | |||

| 17:00–18:00 | ||||||

| Indoor 1 | 17:00–18:00 | Indoor play area in a shopping mall | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |||

| Indoor 2 | 19:30–20:15 | Indoor play area in a shopping mall | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |||

| Bus stop | 1 | 12:30–12:45 | Sitting | Total of 11 bus services. Minor road. | Ambient air conditions | |

| 18:00–18:15 | ||||||

| 2 | 18:30–19:00 | Total of 15 bus services. Major road. | Ambient air conditions | |||

| Walking (seated on a stroller) | 10:00–11:00 | Sitting | Major, minor roads | Ambient air conditions | ||

| 18:00–19:00 | ||||||

| 20:15–21:00 | ||||||

| Bicycle (seated on a bike seat) | 8:00–8:30 | Sitting | Minor, major roads | Ambient air conditions | ||

| 10:00–10:30 | ||||||

| 18:00–19:00 | ||||||

| Bus (seated on a stroller) | 12:45–13:10 | Sitting | Stayed in the middle of single-deck buses | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system | ||

| 18:15–18:40 | ||||||

| 19:00–19:20 | ||||||

| MRT (seated on a stroller) | 17:00–17:15 | Sitting | Stayed in middle of trains | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system | ||

| 20:00–20:15 | ||||||

| Restaurant | Indoor 1 | 12:00–12:45 | Sitting and eating | Indoor restaurant in a commercial building at ≈100 m distance from a minor road; Western food dishes. | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |

| Indoor 2 | 12:30:13:30 | Indoor restaurant in a shopping mall at ≈100 m distance from a minor road; Asian food dishes. | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |||

| Indoor 3 | 19:15–20:05 | Indoor restaurant in a shopping mall at ≈100 m distance from a major road. A whole range of food dishes. | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |||

| Indoor 4 | 19:20–20:10 | Indoor restaurant in a shopping mall at ≈200 m distance from a major road. A whole range of food dishes. | Cooling by the central air-conditioning system; mechanical ventilation | |||

| Outdoor 1 | 18:45–19:15 | Open-air food court. A whole range of food dishes. About 30 food stalls. | Natural ventilation | |||

| 19:00–20:00 | ||||||

| Outdoor 2 | 18:45–19:15 | Open-air food court. A whole range of food dishes. About 20 food stalls. | Natural ventilation | |||

| 19:00–20:00 | ||||||

NV: national ventilation, AC: air conditioning, PAC: portable air cleaner, SL: sleeping.

Table 3.

Characteristics of the air conditioning unit and portable air cleaner used.

| Characteristics | Air conditioning | Portable air cleaner |

|---|---|---|

| Brand | Panasonic | Camfil |

| Model No. | ||

| Indoor | CS-S12TKZW | CamCleaner CITY M (WHITE) |

| Outdoor | CU-3S27KKZ | – |

| Power input (W) (min-max) | ||

| Indoor | 885 (260–1140) | 6 (4–55) |

| Outdoor (for 1 room) | 2060 (520–2830) | – |

| Air flow (m3 min−1) | 11.0 (maximum air circulation) | 1.56 (0.62–7.25) |

| Air filter | Polypropelene (material) | 2 HEPA H13 |

| One-touch (style) | 2 Molecular | |

| Cooling capacity (W) | ||

| (min-max) | ||

| Indoor | 3230 (920–4000) | – |

| Outdoor | 27,000 (10,080-32400) | – |

| Dimensions (m) | 0.295 (H) × 0.919 (W) × 0.199 (D) | 0.70 (H) × 0.33(W) × 0.34 (D) |

| Net Weight (kg) | 9 | 15 |

| Average service area (m2) | – | 75 |

| Particle Clean Air Delivery Rate CADR (m3 h−1) | – | 433 |

| Operation settings | Cooling mode with temperature: 26 °C, fan speed: “level 3” in the range of 1–5 | “Level 3” in the range of 1–6 |

A portable monitoring BC device (micro-Aethalometer AE51, Aethlabs, USA) with the air sampling inlet being placed within the breathing zone of the toddler was carried in the stroller and kept as closely as possible to the toddler throughout the day. This mode of BC monitoring allowed the PE assessment while the toddler was involved in different routine activities such as playing, eating and sleeping on a day-to-day basis under the supervision of an adult. Another micro-Aethalometer was located at the balcony of the home ME to simultaneously measure outdoor BC concentrations during the study periods. In addition, a mobile phone global positioning system (GPS) app (Sensor Play-IOS app) and time-activity diary were used to identify the specific time periods and the locations of the toddler across different MEs.

During the PE assessment campaigns, the local traffic volume was monitored simultaneously by counting the hourly number of vehicles during traffic peak (07:30–08:30 and 18:00–19:00) and non-peak hours (10:00–11:00 and 14:00–15:00) on weekdays and weekends on a road closest to the home ME. Traffic composition was determined by classifying on-road vehicles into four categories of urban transport including motorcycles, gasoline-driven passenger cars/diesel-powered or hybrid taxis, diesel-powered buses (i.e., short transit buses, long transit buses (tandem buses), and private coaches) and diesel-powered trucks (i.e., light commercial trucks, haul trucks). The local traffic volume and composition were determined for 40 h during the two study periods.

2.2. Instrumentation and quality control and assurance

The microAeth AE51 was used to assess the PM-bound BC mass concentration by measuring the attenuation of light transmitted at 880 nm through PM, which is continuously collected on a Teflon-coated borosilicate glass fiber filter. Filter strips of the two AE51 units were changed after every 12 h of exposure to outdoor or indoor air (observed attenuation coefficient (ATN) < 50) to prevent the filter loading effect (Virkkula et al., 2007). Negative or constant values in the recorded data, caused by instrumental noise at high logging intervals or very low BC values, were resolved by using the Optimized Noise reduction Averaging (ONA) algorithm tool (Hagler et al., 2011). To further test the performance of the two AE51 units, we collocated the two BC monitors with an Aethalometer AE33 (Magee Scientific, USA) over a period of 24 h and got a good agreement with R2 = 0.78 and 0.81, slopes = 1.029 and 1.002.

The two micro-Aethalometer AE51 units were operated at a pre-calibrated flow rate of 100 mL min− 1 and data recorded every 1 min. We performed clock synchronization, battery and memory checks before each use of the BC measurement devices. Important observations (such as low airflow of the devices) were noted as part of our measurement protocol so that such spurious measurement data could be removed during data analysis.

2.3. Data processing and statistical analysis

After each sampling section (24 h), the real-time BC measurements were immediately downloaded, inspected and archived to minimize data handling errors or recall bias. We used the R statistical software (R Studio, version 1.1.442) to import, synchronize, and combine datasets and to apply corrections, calibrations and perform statistical analysis. In this study, we consider the geometric mean (GM) rather than the arithmetic mean concentration to discuss the variations of BC concentration as the former fits the log-normal distribution of BC concentrations (Lee et al., 2015; Rivas et al., 2016; Targino et al., 2016), but all other descriptive statistics are also provided. A Pearson correlation test was used to examine relatedness between the traffic volume and the BC concentration. A non-parametric Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to test the difference in the PE to BC concentrations among different activities and MEs. The difference in the PE to BC levels and traffic volumes between 2019 and 2020 was checked based on the Mann-Whitney test.

2.4. Calculation of daily BC exposure contribution, inhaled dose and inhaled dose contribution

The relative contribution of different MEs to daily exposure to BC was calculated by Eq. (1).

| (1) |

where:

MEi is the microenvironment i visited by the toddler;

Ci (unit of μg m− 3) is the GM of exposure to BC concentration observed in MEi;

ti (unit of hour day− 1) is the time spent in;

n is the total number of MEs, .

There are three potential exposure pathways of PM, including inhalation, ingestion and dermal contact (Phalen and Phalen, 2011; USEPA). Out of the three possible routes of exposure, inhalation emerged as the route that would pose the greatest risk to human health as compared to ingestion and dermal contact (Phalen and Phalen, 2011). Therefore, in this study, besides the exposure level of BC, we estimated the daily integrated inhaled dose (unit of μg day− 1) by integrating the BC concentrations (Ci) observed in each ME over the time spent (ti) in the corresponding ME and the inhalation rate (IR) (Eq. (2)).

| (2) |

where: IR (unit of m3 h− 1) chosen for different activities were 0.277 m3 h− 1 for sleeping (in home-sleeping ME) and 0.72 m3 h− 1 for low-intensity activities (other activities apart from sleeping) for a child less than 3 years of age (USEPA, 2019).

The relative contribution of different MEs to the daily inhaled dose was calculated by Eq. (3).

| (3) |

3. Results and discussion

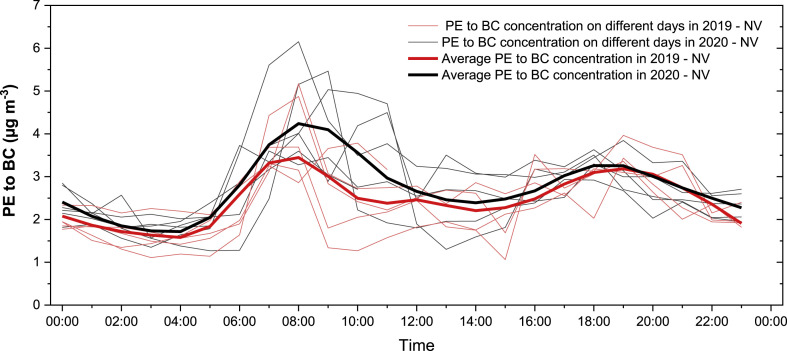

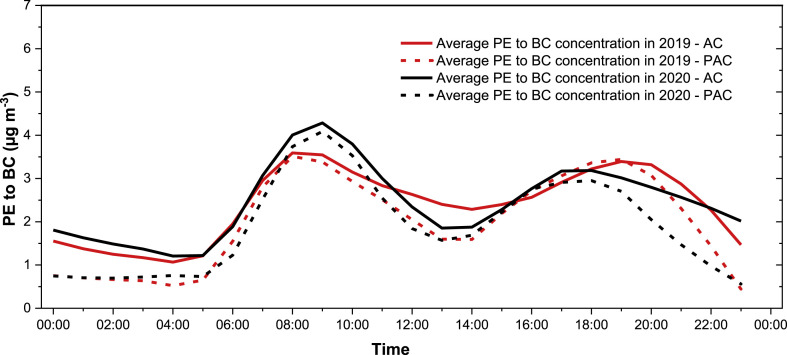

3.1. Diurnal variation of PE to BC concentrations

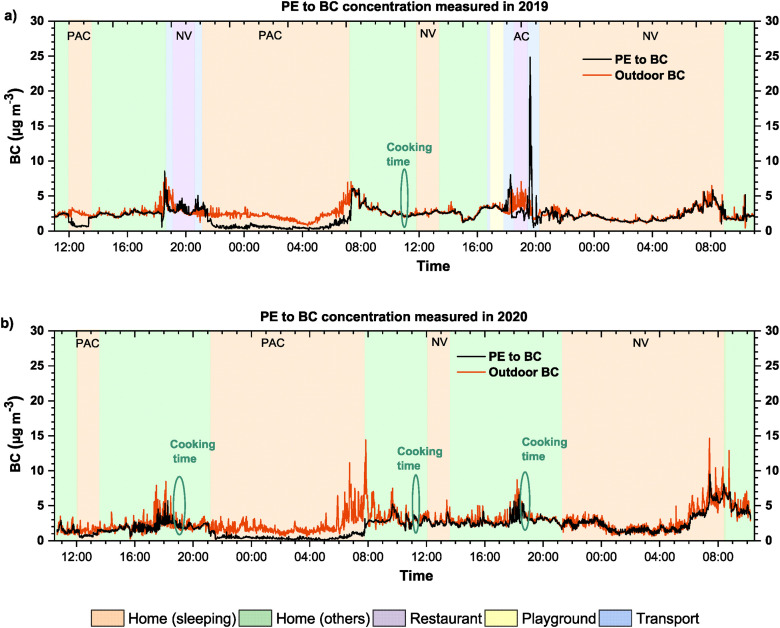

Fig. 2 shows the diurnal variation of PE to BC concentrations for all days while using NV in 2019 and 2020. NV is commonly used in Housing & Development Board (HDB) apartments which are home to over 80% of Singapore's resident population. The diurnal variation of PE to BC concentrations on days with AC and PAC is shown in Fig. 3 . It should be noted that the PE to BC measurement was mostly conducted during weekdays (81% of days). Peaks in the average daily trend for BC are evident around 07:00–09:00 and 17:30–19:30 corresponding to morning and evening traffic peak hours in both observational time periods, indicating the impacts of road traffic on PE to BC for the toddler. The evening peak in BC was less pronounced compared to the morning one. This observation can be attributed to better dispersion of traffic emissions during the evening, caused by unstable atmospheric conditions in the presence of daytime intense incoming solar radiation, lasting for a relatively long duration in the tropical environment (Adam et al., 2020). In general, the geometric means of PE to BC concentrations during morning and evening traffic peak hours were about 3.0 ± 1.7 μg m−3 and 3.7 ± 1.9 μg m−3 in 2019 and 2020, respectively. Apparently, the PE to BC during traffic peak hours increased by 23.3% for the toddler in 2020 compared to 2019. At the night-time (around 22:00–06:00) which was corresponding to the period of the day with the lowest traffic emissions, the BC PE decreased to 2.2 ± 0.3 μg m−3 in 2019 and to 1.8 ± 0.2 μg m−3 in 2020 (with NV scenario). Representative time series data on the temporal variation of BC concentrations are shown in Fig. 4 . More details about the impacts of COVID-19 pandemic on changes in the traffic characteristics and the toddler's PE to BC levels in 2020 compared to 2019 are discussed in the following sections.

Fig. 2.

Diurnal cycle of PE to BC in 2019 and 2020 (days with natural ventilation, NV).

Fig. 3.

Diurnal cycle of PE to BC in 2019 and 2020 (days with air conditioning, AC, and portable air cleaner, PAC).

Fig. 4.

Representative time series of PE to BC concentration measured in: (a) 2019 and (b) 2020.

3.2. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on PE of the toddler to BC concentration

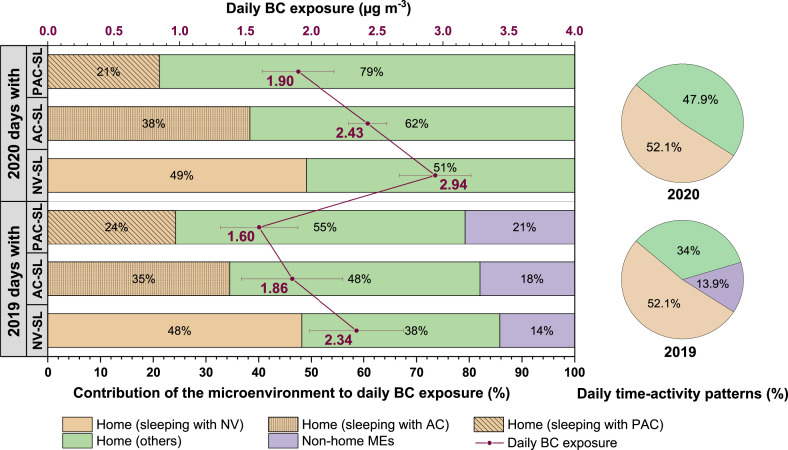

In general, during both measurement periods, the toddler spent the majority of time indoors, especially in the home ME (more than 86% in 2019 and almost 100% in 2020) (see Fig. 5 ), indicating the importance of health risk assessment at this ME. Due to the difference in the toddler's BC exposure levels and activity levels, the home ME was divided into two parts, considering whether the toddler was sleeping or involved in other general activities such as playing, eating, etc. The results show that the greatest amount of time was spent on sleeping (52.1% for both years), followed by being involved in other general activities at home (34.0% in 2019 and 47.9% in 2020), and 13.9% for non-home MEs in 2019 (including commuting, playing in play areas and eating in restaurants). Our results on time-activity are fairly similar to those found in Chen et al. (2019) and Chen et al. (2020a), who studied the physical activity and behavior among young children in Singapore.

Fig. 5.

Contributions of the home micro-environment to the BC exposure in the year 2019 and 2020 under different exposure scenarios. Different bars mean the average BC exposure in days with natural ventilation (NV), air conditioning (AC) and portable air cleaner (PAC) while the child was sleeping (SL).

The PE to BC measured in different MEs in 2019 and 2020 is shown in Table 4 . The BC GM concentrations in the home ME were 2.2 ± 1.6 μg m−3 and 2.8 ± 1.9 μg m−3 during the overall sleeping time (from 12:00 to 13:30, and from 21:30 to 8:00) with the NV scenario, and 2.6 ± 1.5 μg m−3 and 3.1 ± 1.9 μg m−3 during other general activities in 2019 and 2020, respectively. The toddler's BC exposure in 2019 in the non-home MEs was 2.4 ± 2.2 μg m−3. The PE to BC measured in the home ME in our study in both years is relatively higher than the results reported in several BC measurement studies in Spain, Portugal (≈ 0.9 μg m−3 (Cunha-Lopes et al., 2019; Rivas et al., 2016)) and Korea (≈ 1.2 μg m−3 (Jeong and Park, 2018)), but lower than those measured in India (5.4–34.9 μg m−3 (Ravindra, 2019)). The differences in the BC PE levels of the aforementioned studies are likely due the variation of indoor BC emission sources (e.g., cooking, smoking, candles and incense burning) and infiltration from outdoor sources of BC (i.e., the difference in nearby traffic volume related to the home location).

Table 4.

PE to BC (μg m−3) and ratio of PE and outdoor (OD) BC concentration (simultaneous measurement, the ratios are calculated pairwise) in different MEs.

| Year | Micro-environment | BC (μg m−3) |

PE/OD |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GM | GSD | AM | SD | Max | Min | AM | SD | Max | Min | |||

| 2019 | Home | NV-SL | 2.17 | 1.55 | 2.35 | 0.93 | 17.37 | 0.03 | 0.98 | 0.33 | 3.02 | 0.27 |

| AC-SL | 1.23 | 1.10 | 1.36 | 0.93 | 5.46 | 0.04 | 0.70 | 0.21 | 1.87 | 0.06 | ||

| PAC-SL | 0.75 | 1.04 | 0.76 | 0.19 | 1.70 | 0.52 | 0.25 | 0.13 | 0.66 | 0.19 | ||

| NV-Others | 2.59 | 1.48 | 2.78 | 1.07 | 21.50 | 0.15 | 1.08 | 0.46 | 3.50 | 0.06 | ||

| Non-home | 2.40 | 2.23 | 3.26 | 3.50 | 44.55 | 0.13 | 1.25 | 1.07 | 11.05 | 0.03 | ||

| 2020 | Home | NV-SL | 2.77 | 1.90 | 3.52 | 1.88 | 7.62 | 0.61 | 0.99 | 0.36 | 3.85 | 0.24 |

| AC-SL | 1.79 | 1.65 | 2.02 | 1.10 | 7.05 | 0.81 | 0.69 | 0.31 | 2.68 | 0.13 | ||

| PAC-SL | 0.77 | 1.00 | 0.93 | 0.40 | 3.13 | 0.20 | 0.26 | 0.16 | 1.44 | 0.03 | ||

| NV-Others | 3.13 | 1.85 | 3.76 | 1.69 | 29.86 | 0.66 | 1.17 | 0.52 | 7.42 | 0.29 | ||

GM: geometric mean, GSD: geometric standard deviation, AM: arithmetic mean, SD: standard deviation, NV: national ventilation, AC: air conditioning, PAC: portable air cleaner, SL: sleeping.

During the COVID-19 pandemic in the year 2020, family members mostly stayed at home and, therefore, generally spent more time on cooking leading to slightly higher exposure to BC (see in Fig. 4). Jeong and Park (2017a) had revealed that cooking with gas stoves and food rich in fat at a high temperature increased BC exposure. It was recently reported that an increase of 12% daily PM2.5 levels and 37–559% of total volatile organic compound (TVOC) concentrations were also observed in the home MEs during the lockdown period in Spain compared to the period before lockdown (Domínguez-Amarillo et al., 2020). This increase was attributed to more intense as well as frequent cooking and other indoor activities of building occupants than usual. However, BC emissions from indoor cooking in our study were likely to be low (Fig. 4) as cooking types involved only boiling, steaming and light-frying on a liquefied petroleum gas stove (See and Balasubramanian, 2008; Sharma and Balasubramanian, 2020). It should be noted that there were no other major sources of BC emission (e.g., candles or incense burning) during the two study periods.

The simultaneous measurement of PE to BC in different MEs and outdoor (OD) BC in the home ME also allowed us to calculate their ratios, i.e., PE/OD (see Table 4). The ratios were highest (mean of 1.3) for non-home MEs, implying that the toddler was exposed to higher BC concentrations in those MEs compared to the home ME. Moreover, the pairwise comparisons between PE and OD measurements when the toddler was at home in the NV scenario (≈1.0) indicated that the PE to BC was very similar to those measured outdoors. In addition to the NV scenario, we investigated BC levels for two other commonly maintained ventilation scenarios (AC and PAC) in the tropics during the sleeping time (the most prolonged and vulnerable exposure) in the home ME. The average PE/OD ratios were found to be approximately 0.70 and 0.25 for AC and PAC scenarios, respectively, for both years 2019 and 2020, showing the effectiveness of the PAC in mitigating the exposure to indoor BC levels (through the filtration of indoor air by high-efficiency particulate air - HEPA filters) (Tran et al., 2020b).

Fig. 5 and Table 5 presents the relative contributions of different activities/MEs to the toddler's daily exposure to BC concentration and inhaled dose, respectively. The overall daily PE to BC concentration of the toddler was 2.3 ± 0.4 μg m−3 in 2019 and was enhanced significantly by approximately 25.5% (p-value <0.05) to 2.9 ± 0.3 μg m−3 in 2020 with the NV scenario. Using PE mitigation measures such as AC and PAC during the sleeping time at home helped to reduce the daily exposure to BC to 1.9 ± 0.4 μg m−3 (≈ 20.8% reduction compared to the NV scenario) and 1.6 ± 0.3 μg m−3 (≈ 31.6% reduction) in 2019, and 2.4 ± 0.1 μg m−3 (≈ 17.4% reduction) and 1.9 ± 0.3 μg m−3 (≈ 35.0% reduction) in 2020, respectively. On the other hand, the daily BC inhaled dose was equal to 28.5 μg for NV scenario in 2019 and increased by 24.5% to 35.5 μg in 2020. The total daily inhaled doses recorded in 2019 were reduced to 25.2 μg and 23.6 μg, while the numbers were 32.1 μg and 28.6 μg in 2020 for AC and PAC scenarios, respectively.

Table 5.

Daily integrated inhaled dose in different MEs and for different activities.

| Scenario | Home - Sleeping |

Home - NV - Others |

Non-home |

Sum |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| μg day−1 | % | μg day−1 | % | μg day−1 | % | μg day−1 | % | ||

| 2019 | NV-SL | 7.48 | 26.28 | 15.24 | 53.51 | 5.76 | 20.22 | 28.48 | 100 |

| AC-SL | 4.24 | 16.81 | 15.24 | 60.38 | 5.76 | 22.81 | 25.24 | 100 | |

| PAC-SL | 2.57 | 10.92 | 15.24 | 64.65 | 5.76 | 24.43 | 23.57 | 100 | |

| 2020 | NV-SL | 9.56 | 26.97 | 25.89 | 73.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 35.45 | 100 |

| AC-SL | 6.17 | 19.24 | 25.89 | 80.76 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 32.06 | 100 | |

| PAC-SL | 2.67 | 9.34 | 25.89 | 90.66 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 28.56 | 100 | |

Due to the largest amount of time spent at home and high BC concentrations measured there, the home ME had the dominant contribution to the overall daily exposure and inhaled dose to BC (in total ≈ 80% in 2019 and almost 100% in 2020). The highest contribution to the daily exposure to BC was observed while the child was sleeping (in NV scenario) (48.2%), followed by the active time period in the home ME (37.6%) and non-home MEs (14.2%) in 2019, whereas relatively equal contributions (about 50%) were observed for sleep and active periods in 2020 when mobility restrictions prevented people from participating in outdoor activities. Nevertheless, the home ME while the child was active contributed mostly to the daily inhaled dose (about 15.2 μg ≈ 53.5% in 2019 and 25.9 μg ≈ 73.0% in 2020 (Table 5) due to the highest inhalation rate and high exposure concentration of the child while it was in this ME.

3.3. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on traffic volume/composition and PE to BC

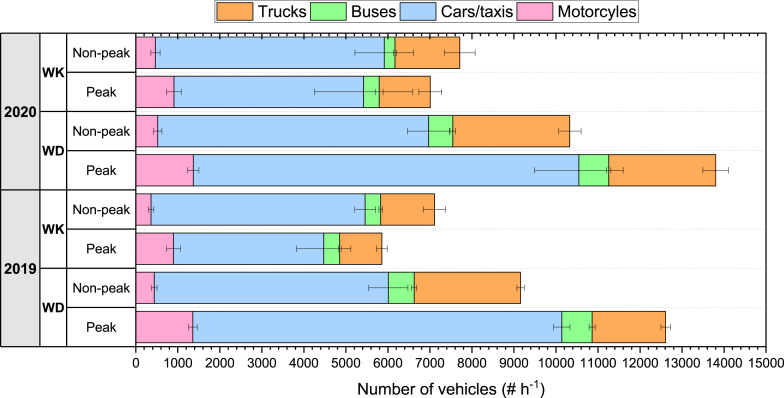

Vehicular traffic emissions have been shown to influence the ambient and PE exposure to BC levels in Singapore in several previous studies (Tran et al., 2020a, 2020b, 2020c, 2020d). In order to ascertain the impact of traffic emissions on the PE of the toddler to BC, we also simultaneously monitored the local traffic characteristics on the road closest to the home ME in addition to BC. Fig. 6 shows the traffic volume and composition during traffic peak and non-peak hours on weekdays and weekends prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic. In general, passenger cars/taxis accounted for a major fraction of on-road vehicles (about 66.0%), followed by trucks (20.0%), motorcycles (9.0%) and buses (5.0%) in both years, which is in agreement with the findings by Tran et al. (2020a). Interestingly, compared to the same period in 2019, the overall traffic volume was 11.1% (p-value = 0.13), and 14.1% (p-value < 0.05) higher in 2020, on weekdays and weekends, respectively. Specifically, there was an increase of the hourly numbers of trucks (27.7% and 14.1%, significantly with p-value < 0.05), cars/taxis (10.1%, p-value = 0.33 and 16.6%, p-value < 0.05), motorcycles (9.9%, p-value = 0.50 and 15.0%, p-value = 0.12) on weekdays and weekends, respectively. In contrast, the bus volume declined by 4.0% (p-value = 0.06) on weekdays and 17.1% (p-value = 0.09) on weekends.

Fig. 6.

Traffic volume and composition during peak and non-peak traffic hours on weekdays (WD) and weekends (WK) in 2019 and 2020.

The increase in private transport (cars/taxis and motorcycles) and the decline of public transport (buses) may be explained by the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the preferred mode of transport by city dwellers. The concern over the spread of the infection among travellers and the perceived health risk was believed to shift the mode of travel from public transport to private transport and non-motorized modes in many countries in the world (Abdullah et al., 2020; Orro et al., 2020). An online questionnaire survey conducted in June 2020 found that 39% of respondents in Singapore were more willing to commute by cars, and among those who used to drive before the health crisis, 61% of respondents were more willing to use a car (Tan, 2020). Conversely, people were less willing to take public transport (buses and trains) to “minimize contact with crowds” as there was a perceived higher risk of infection with COVID-19 in these modes of transport (Tan, 2020). Also, delivery services (e.g., delivery of food and consumer goods by motorcycles, cars, trucks) increased in sales in 2020 compared to the year 2019 as more people worked at home as part of business continuity plans or stayed indoors due to concerns over the coronavirus (Abdullah, 2020). Additionally, after lifting mobility restrictions in phase 2 after the CB period, Singapore moved toward the economic ramp-up with the resumption of economic activities including businesses in the retail, entertainment and leisure sectors apart from manufacturing and delivery of goods and services. Several other cities in Canada (Tian et al., 2021) and Spain (Orro et al., 2020) were also observed with the rapid recovery in traffic volume after the opening policy was announced. Moreover, we observed strong correlations between BC exposure measured in the home ME and total traffic volume (Pearson correlation r = 0.59, p-value < 0.05), in particular with the number of diesel vehicles (trucks: r = 0.68, p-value < 0.05) in both years. These results, together with the observed elevated PE to BC in the home ME, confirm the significance of the BC infiltration and impact of the traffic emissions on residential buildings in highly densified cities such as Singapore.

Overall, the results of our study clearly point to the dominant role of vehicular traffic emissions (especially from diesel vehicles) in the BC exposure experienced by the toddler. The COVID-19 pandemic led changes in the magnitude of traffic-related emissions and also the toddler's mobility pattern in the year 2020 when compared to the same time period in 2019, which significantly influenced the toddler's PE to BC. Therefore, proper air pollution exposure mitigation actions should be taken by urban dwellers to protect the vulnerable groups in societies. We do acknowledge that our pilot study has limitations: we performed the PE assessment to BC of a toddler living in Singapore. Therefore, the PE to BC could be different in other cities due to the difference in geographical and cultural backgrounds. Our main goal was to conduct a comparative investigation of the PE of young children to BC, a representative toxic air pollutant of combustion origin, before and during COVID-19 pandemic. The related goal was to quantify the direct impacts of changes in traffic emissions on neighbourhood-scale air quality with specific reference to the PE to traffic-related air pollutants, which is currently not captured by the fixed ambient air quality monitoring stations. Further investigations involving a larger sample size with toddlers of different ages (1–3 years old) at multiple locations with additional traffic information (e.g., on different street types, vehicle fleet age distributions) are warranted. Nevertheless, the practical implications of our study as stated above provide the impetus for conducting more research on PE to BC of vulnerable groups in societies in cities.

4. Conclusions

This pilot study describes a comparative investigation of the PE to BC of a toddler and traffic characteristics in Singapore before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The BC exposure measurements were conducted in July and August in 2019 (considered as before COVID 19 pandemic) and the same period in 2020 (during COVID-19 pandemic) during which Singapore had moved to the re-opening phase after a strict lockdown.

The daily PE to BC concentration and inhaled dose of the toddler was observed to be enhanced by approximately 25% in the year 2020 compared to that in 2019. This increase in BC exposure during the COVID-19 pandemic was accompanied by a simultaneous increase in traffic volume of 11.1% and 14.1% on weekdays and weekends, respectively, compared to the same period in the previous year. In particular, we observed an increase in the number of trucks as well as cars/taxis and motorcycles (private transport) and a decline in the number of buses (public transport) during the study periods. Strong correlations were also reported between PE to BC concentration measured in the home ME and total traffic volume, especially the number of diesel vehicles. This implies the significant influence of traffic-related emissions on the BC levels in ambient air.

Among the different MEs visited by the toddler, the home ME was the main contributor to the overall daily BC exposure and inhaled dose with a total of about 80% in 2019 and almost 100% in 2020. Therefore, this work highlights that measures to reduce toddlers’ exposure to BC should focus on urban planning to reduce the traffic around residential areas. In addition, the phasing out of diesel-driven vehicles, which are significant emitters of BC, would contribute towards improved overall air quality in urban environments. In the home environment, using a PAC equipped with high-grade air filters showed significant reductions in the exposure to BC compared to the NV and AC scenarios. Therefore, to protect the vulnerable populations, proper mitigation actions such as using PACs or centralized air conditioning systems with high-grade PM filters should be considered, in particular during severe air pollution instances such as severe traffic pollution during peak hours.

We observed the changes in traffic characteristics and the toddler's mobility patterns resulting in the differences in PE to BC before and during COVID-19 pandemic in this study. Currently, among the COVID-19 hotspot regions, several of them (e.g., certain countries in Europe) have still not eased lockdown measures, while some regions have shown progress in tackling the virus and recently lifted their lockdowns. As lockdown restrictions are eased and economic recovery sets in, air pollution levels, especially traffic-related air pollutants, are expected to return to pre-pandemic levels or even get worse (Ding et al., 2020; Tian et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2020), which may impact toddlers' PE to air pollutants. Therefore, the results of our study merit serious consideration in light of exposure to BC health impacts and mitigation strategies in other cities or such a pandemic in the future.

Author contributions

Phuong T.M. Tran: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing - original draft. Max G. Adam: Writing - original draft, review & editing. Rajasekhar Balasubramanian: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

This research was financially supported by the National University of Singapore (grant number R-302-000-236-114).

References

- Abdullah M., Dias C., Muley D., Shahin M. Exploring the impacts of Covid-19 on travel behavior and mode preferences. Trans. Res. Interdis. Perspect. 2020;8:100255. doi: 10.1016/j.trip.2020.100255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdullah Z. Channelnewsasia. 2020. Delivery services see spike in business because of Covid-19. [Google Scholar]

- Adam M.G., Chiang A.W.J., Balasubramanian R. Insights into characteristics of light absorbing carbonaceous aerosols over an urban location in Southeast Asia. Environ. Pollut. 2020;257:113425. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemany S., Vilor-Tejedor N., García-Esteban R., Bustamante M., Dadvand P., Esnaola M., Mortamais M., Forns J., Van Drooge B.L., Álvarez-Pedrerol M. Traffic-related air pollution, apoe Ε 4 status, and neurodevelopmental outcomes among school children enrolled in the breathe project (catalonia, Spain) Environ. Health Perspect. 2018;126 doi: 10.1289/EHP2246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assimakopoulos V., Bekiari T., Pateraki S., Maggos T., Stamatis P., Nicolopoulou P., Assimakopoulos M. Assessing personal exposure to Pm using data from an integrated indoor-outdoor experiment in Athens-Greece. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;636:1303–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao R., Zhang A. Does lockdown reduce air pollution? Evidence from 44 cities in northern China. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:139052. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.139052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekbulat B., Apte J.S., Millet D.B., Robinson A.L., Wells K.C., Presto A.A., Marshall J.D. Changes in criteria air pollution levels in the us before, during, and after Covid-19 stay-at-home orders: evidence from regulatory monitors. Sci. Total Environ. 2020:144693. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bond T.C., Doherty S.J., Fahey D.W., Forster P.M., Berntsen T., DeAngelo B.J., Flanner M.G., Ghan S., Kärcher B., Koch D. Bounding the role of black carbon in the climate system: a scientific assessment. J. Geophys. Res.: Atmosphere. 2013;118:5380–5552. [Google Scholar]

- Buonanno G., Stabile L., Morawska L., Russi A. Children exposure assessment to ultrafine particles and black carbon: the role of transport and cooking activities. Atmos. Environ. 2013;79:53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Buzzard N.A., Clark N.N., Guffey S.E. Investigation into pedestrian exposure to near-vehicle exhaust emissions. Environ. Health. 2009;8:1–13. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-8-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Bernard J.Y., Padmapriya N., Yao J., Goh C., Tan K.H., Yap F., Chong Y.-S., Shek L., Godfrey K.M. Socio-demographic and maternal predictors of adherence to 24-hour movement guidelines in Singaporean children. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Activ. 2019;16:70. doi: 10.1186/s12966-019-0834-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B., Waters C.N., Compier T., Uijtdewilligen L., Petrunoff N.A., Lim Y.W., Van Dam R., Müller-Riemenschneider F. Understanding physical activity and sedentary behaviour among preschool-aged children in Singapore: a mixed-methods approach. BMJ open. 2020;10 doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen K., Wang M., Huang C., Kinney P.L., Anastas P.T. Air pollution reduction and mortality benefit during the Covid-19 outbreak in China. The Lancet Planetary Health. 2020;4:e210–e212. doi: 10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30107-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conrad A., Seiwert M., Hünken A., Quarcoo D., Schlaud M., Groneberg D. The German environmental survey for children (geres iv): reference values and distributions for time-location patterns of German children. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2013;216:25–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha-Lopes I., Martins V., Faria T., Correia C., Almeida S.M. Children's exposure to sized-fractioned particulate matter and black carbon in an urban environment. Build. Environ. 2019;155:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Statistics Singapore . 2019. Yearbook of Statistics Singapore. [Google Scholar]

- Ding J., van der A R.J., Eskes H., Mijling B., Stavrakou T., Van Geffen J., Veefkind J. Nox emissions reduction and rebound in China due to the Covid‐19 crisis. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020;47 [Google Scholar]

- Domínguez-Amarillo S., Fernández-Agüera J., Cesteros-García S., González-Lezcano R.A. Bad air can also kill: residential indoor air quality and pollutant exposure risk during the Covid-19 crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Publ. Health. 2020;17:7183. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17197183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dons E., Panis L.I., Van Poppel M., Theunis J., Willems H., Torfs R., Wets G. Impact of time–activity patterns on personal exposure to black carbon. Atmos. Environ. 2011;45:3594–3602. [Google Scholar]

- Fees B.S., Fischer E., Haar S., Crowe L.K. Toddler activity intensity during indoor free-play: stand and watch. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015;47:170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.jneb.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire C., Ramos R., Puertas R., Lopez-Espinosa M.-J., Julvez J., Aguilera I., Cruz F., Fernandez M.-F., Sunyer J., Olea N. Association of traffic-related air pollution with cognitive development in children. J. Epidemiol. Community Health. 2010;64:223–228. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.084574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea K., MacCalman L., Amend-Straif M., Gorman-Ng M., Cherrie J. Are children in buggies exposed to higher PM2. 5 concentrations than adults. J. Eniron. Health Res. 2014;14:28–42. [Google Scholar]

- Goel A., Kumar P. Vertical and horizontal variability in airborne nanoparticles and their exposure around signalised traffic intersections. Environ. Pollut. 2016;214:54–69. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grahame T.J., Klemm R., Schlesinger R.B. Public health and components of particulate matter: the changing assessment of black carbon. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2014;64:620–660. doi: 10.1080/10962247.2014.912692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagler G.S., Yelverton T.L., Vedantham R., Hansen A.D., Turner J.R. Post-processing method to reduce noise while preserving high time resolution in aethalometer real-time black carbon data. Aerosol Air Q. REs. 2011;11:539–546. [Google Scholar]

- Hudda N., Simon M.C., Patton A.P., Durant J.L. Reductions in traffic-related black carbon and ultrafine particle number concentrations in an urban neighborhood during the Covid-19 pandemic. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;742:140931. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.140931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen N.A.H., Hoek G., Simic-Lawson M., Fischer P., Van Bree L., Ten Brink H., Keuken M., Atkinson R.W., Anderson H.R., Brunekreef B. Black carbon as an additional indicator of the adverse health effects of airborne particles compared with PM10 and PM2.5. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011;119:1691–1699. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1003369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Park D. Characteristics of elementary school children's daily exposure to black carbon (Bc) in Korea. Atmos. Environ. 2017;154:179–188. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Park D. Contribution of time-activity pattern and microenvironment to Black carbon (Bc) inhalation exposure and potential internal dose among elementary school children. Atmos. Environ. 2017;164:270–279. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong H., Park D. Characteristics of peak concentrations of Black carbon encountered by elementary school children. Sci. Total Environ. 2018;637:418–430. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.04.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung K.H., Lovinsky-Desir S., Yan B., Torrone D., Lawrence J., Jezioro J.R., Perzanowski M., Perera F.P., Chillrud S.N., Miller R.L. Effect of personal exposure to Black carbon on changes in allergic asthma gene methylation measured 5 Days later in urban children: importance of allergic sensitization. Clin. Epigenet. 2017;9:61. doi: 10.1186/s13148-017-0361-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H., Kang K., Kim T. Effect of occupant activity on indoor particle concentrations in Korean residential buildings. Sustainability. 2020;12:9201. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Rivas I., Sachdeva L. Exposure of in-pram Babies to airborne particles during morning drop-in and afternoon pick-up of school children. Environ. Pollut. 2017;224:407–420. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar P., Hama S., Omidvarborna H., Sharma A., Sahani J., Abhijith K., Debele S.E., Zavala-Reyes J.C., Barwise Y., Tiwari A. Temporary reduction in fine particulate matter due to ‘anthropogenic emissions switch-off’during Covid-19 lockdown in Indian cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;62:102382. doi: 10.1016/j.scs.2020.102382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K.-H., Jung H.-J., Park D.-U., Ryu S.-H., Kim B., Ha K.-C., Kim S., Yi G., Yoon C. Occupational exposure to diesel particulate matter in municipal household waste workers. PloS One. 2015;10 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0135229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Lei X.-n., Xiu G.-l., Gao C.-y., Gao S., Qian N.-s. Personal exposure to black carbon during commuting in peak and off-peak hours in shanghai. Sci. Total Environ. 2015;524:237–245. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2015.03.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Tartarini F. Changes in air quality during the Covid-19 lockdown in Singapore and associations with human mobility trends. Aerosol Air Q. REs. 2020;20:1748–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Lim L.W., Yip L.W., Tay H.W., Ang X.L., Lee L.K., Chin C.F., Yong V. Sustainable practice of ophthalmology during Covid-19: challenges and solutions. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2020:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00417-020-04682-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin W., Dai J., Liu R., Zhai Y., Yue D., Hu Q. Integrated assessment of health risk and climate effects of black carbon in the pearl river delta region, China. Environ. Res. 2019;176:108522. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LTA . 2020. Motor Vehicle Population by Type of Fuel Used. [Google Scholar]

- Niranjan R., Thakur A.K. The toxicological mechanisms of environmental soot (black carbon) and carbon black: focus on oxidative stress and inflammatory pathways. Front. Immunol. 2017;8 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwanaji-Enwerem J.C., Allen J.G., Beamer P.I. Another invisible enemy indoors: Covid-19, human health, the home, and United States indoor air policy. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2020;30:773–775. doi: 10.1038/s41370-020-0247-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orro A., Novales M., Monteagudo Á., Pérez-López J.-B., Bugarín M.R. Impact on city bus transit services of the Covid–19 lockdown and return to the new normal: the case of a coruña (Spain) Sustainability. 2020;12:7206. [Google Scholar]

- Paunescu A.C., Attoui M., Bouallala S., Sunyer J., Momas I. Personal measurement of exposure to black carbon and ultrafine particles in schoolchildren from Paris cohort (paris, France) Indoor Air. 2017;27:766–779. doi: 10.1111/ina.12358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perera F.P. Multiple threats to child health from fossil fuel combustion: impacts of air pollution and climate change. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017;125:141–148. doi: 10.1289/EHP299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phalen R.F., Phalen R.N. Jones & Bartlett Publishers; 2011. Introduction to Air Pollution Science: A Public Health Perspective. [Google Scholar]

- Ravindra K. Emission of black carbon from rural households kitchens and assessment of lifetime excess cancer risk in villages of north India. Environ. Int. 2019;122:201–212. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas I., Donaire‐Gonzalez D., Bouso L., Esnaola M., Pandolfi M., De Castro M., Viana M., Àlvarez‐Pedrerol M., Nieuwenhuijsen M., Alastuey A. Spatiotemporally resolved black carbon concentration, schoolchildren's exposure and dose in barcelona. Indoor Air. 2016;26:391–402. doi: 10.1111/ina.12214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- See S.W., Balasubramanian R. Chemical characteristics of fine particles emitted from different gas cooking methods. Atmos. Environ. 2008;42:8852–8862. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Kumar P. A review of factors surrounding the air pollution exposure to in-pram babies and mitigation strategies. Environ. Int. 2018;120:262–278. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma A., Kumar P. Quantification of air pollution exposure to in-pram babies and mitigation strategies. Environ. Int. 2020;139:105671. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2020.105671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Balasubramanian R. Assessment and mitigation of indoor human exposure to fine particulate matter (Pm2. 5) of outdoor origin in naturally ventilated residential apartments: a case study. Atmos. Environ. 2019;212:163–171. [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R., Balasubramanian R. Evaluation of the effectiveness of a portable Air cleaner in mitigating indoor human exposure to cooking-derived airborne particles. Environ. Res. 2020;183:109192. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.109192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suglia S.F., Gryparis A., Wright R.O., Schwartz J., Wright R.J. Association of black carbon with cognition among children in a prospective birth cohort study. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2008;167:280–286. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan C. The Straitstimes. 2020. More people steering towards private transport in Singapore amid Covid-19 pandemic: survey. [Google Scholar]

- Targino A.C., Gibson M.D., Krecl P., Rodrigues M.V.C., dos Santos M.M., de Paula Corrêa M. Hotspots of black carbon and PM2. 5 in an urban area and relationships to traffic characteristics. Environ. Pollut. 2016;218:475–486. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2016.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian X., An C., Chen Z., Tian Z. Assessing the impact of Covid-19 pandemic on urban transportation and air quality in Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;765:144270. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T., Nguyen T., Balasubramanian R. Personal exposure to airborne particles in transport micro-environments and potential health impacts: a tale of two cities. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020;63:102470. [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T., Adam M.G., Balasubramanian R. Mitigation of indoor human exposure to airborne particles of outdoor origin in an urban environment during haze and non-haze periods. J. Hazard Mater. 2020;403:123555. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T., Zhao M., Yamamoto K., Minet L., Nguyen T., Balasubramanian R. Cyclists' personal exposure to traffic-related air pollution and its influence on bikeability. Transport. Res. Transport Environ. 2020;88:102563. [Google Scholar]

- Tran P.T.M., Ngoh J.R., Balasubramanian R. Assessment of the integrated personal exposure to particulate emissions in urban micro-environments: a pilot study. Aerosol Air Q. REs. 2020;20:341–357. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations . 2019. Word Population Prospects 2019. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA . 2019. Guidelines for Human Exposure Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- USEPA. Exposure Assessment Tools by Routes, https://www.epa.gov/expobox/exposure-assessment-tools-routes, Last Access: 10 June 2021.

- Venter Z.S., Aunan K., Chowdhury S., Lelieveld J. Air pollution declines during Covid-19 lockdowns mitigate the global health burden. Environ. Res. 2021;192:110403. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2020.110403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virkkula A., Mäkelä T., Hillamo R., Yli-Tuomi T., Hirsikko A., Hämeri K., Koponen I.K. A simple procedure for correcting loading effects of aethalometer data. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2007;57:1214–1222. doi: 10.3155/1047-3289.57.10.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivanco-Hidalgo R.M., Wellenius G.A., Basagaña X., Cirach M., González A.G., de Ceballos P., Zabalza A., Jiménez-Conde J., Soriano-Tarraga C., Giralt-Steinhauer E. Short-term exposure to traffic-related air pollution and ischemic stroke onset in barcelona, Spain. Environ. Res. 2018;162:160–165. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2017.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO . 2005. World Health Organization: Effects of Air Pollution on Children's Health and Development: A Review of the Evidence. [Google Scholar]

- Wu X., Bennett D.H., Lee K., Cassady D.L., Ritz B., Hertz-Picciotto I. Longitudinal variability of time-location/activity patterns of population at different ages: a longitudinal study in California. Environ. Health. 2011;10:80. doi: 10.1186/1476-069X-10-80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yolton K., Khoury J.C., Burkle J., LeMasters G., Cecil K., Ryan P. Lifetime exposure to traffic-related air pollution and symptoms of depression and anxiety at age 12 years. Environ. Res. 2019;173:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Z.-H., Khlystov A., Norford L.K., Tan Z.-K., Balasubramanian R. Characterization of traffic-related ambient fine particulate matter (PM2. 5) in an Asian city: environmental and health implications. Atmos. Environ. 2017;161:132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng B., Geng G., Ciais P., Davis S.J., Martin R.V., Meng J., Wu N., Chevallier F., Broquet G., Boersma F. Satellite-based estimates of decline and rebound in China’s CO2 emissions during Covid-19 pandemic. Sci. Adv. 2020;6 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abd4998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]