Abstract

A novel Mn(II) complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) of a ditopic ligand 1,5-bis(2-benzoylpyridine) thiocarbohydrazone (H2L) was synthesized and characterised physico-chemically. A part of the mother solution of the complex 1 and THF yielded single crystals in a triclinic space group and are found same from the crystals obtained from another mixture of the mother solution and ethyl acetate. Single crystal XRD studies have confirmed the mononuclear complex formation and absence of any interactions between the Mn(II) centers. A solution of the complex 1 in chloroform, conversely, yielded a crystallographically different complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) in monoclinic and is also characterised with single crystal XRD. The ligand is coordinated through thione sulfur atom to form a square pyramidal geometry around Mn(II) center in both the complexes. The molecular packing of the complexes is found influenced by the nature of solvent inclusion, and are stabilized by different non-covalent interactions in the lattice. The intermolecular interactions are quantified by Hirshfeld surface analyses, which reveal that H•••Cl interactions has maximum contribution to the total Hirshfeld surface in the complex 1a. This is the first crystal structure study of a manganese(II) complex of a bisthiocarbohydrazone ligand. The molecular and electronic structures of the complexes are studied by DFT quantum chemical calculations. The band gap (Eg) of the complex 1 was estimated as 2.45 eV using Kubelka-Munk model and is in agreement with the electronic spectral calculations of the complex at TD-DFT level. Molecular docking studies of both the ligand and the complex reveal their greater propensity towards SARS-CoV-2 main protease compared to B-DNA dodecamer. Also, the binding potential of the ligand and the complex with SARS-CoV-2 main protease is found higher than that with chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine.

Keywords: Thiocarbohydrazone, DFT, X-ray diffraction, Hirshfeld surface analysis, Molecular Docking, SARS-CoV-2

Graphical abstract

Two crystallographically different complexes of a novel Mn(II) bisthiocarbohydrazone complex are investigated with a comparative structural and intermolecular interaction study. The experimental results are supported by theoretical DFT study. Both the thiocarbohydrazone ligand and the Mn(II) complex are subjected to the molecular docking studies with the crystal structure of B-DNA dodecamer and SARS-CoV-2 main protease. The Mn(II) complex exhibit excellent docking score and greater propensity towards SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

1. Introduction

The coordination chemistry of thiocarbohydrazones, the higher homologues of the well-known thiosemicarbazones, and their biological potentials are very little known and yet to be explored. The extra hydrazine moiety provides the ligands variable metal binding modes, structural diversity and promising biological implications including antiviral and anticancer applications [1]. Thiosemicarbazones and their complexes are known for their various antiviral properties and transition metal complexes have recently been identified as potential tools against SARS-CoV-2 [2]. The molecular docking study of a platinum based thiosemicarbazone complex with SARS-CoV-2 have revealed its potentials for the inhibition of RNA dependent RNA polymerase RdRp, which is comparably higher with respect to WHO recommended repurposed drugs like chloroquine, Remdesivir, Galidesivir, Tenofovir, Sofosbuvir, Ribavirin, etc. [2]. Similarly, Pd-thiosemicarbazone complexes have also been reported as having better binding potentials with SARS-CoV-2 main protease 6Y2F compared with chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine [3]. Also, Mn(II) thiosemicarbazone complexes are known for their versatile biological implications [4]. As various studies are progressing in several directions to develop novel medicines for the treatment of dangerous COVID-19 disease that is spreading all over the world [5–8], the nature of the interaction between a bisthiocarbohydrazone and its Mn(II) complex with a main protease of SARS-CoV-2 would be worthwhile to study.

Besides the biological potentials [1,9], the coordination chemistry of ditopic bisthiocarbohydrazones and their oxygen analogue carbohydrazones are getting increasing attention as they are considered as potential building blocks for controlled self-assembly of metallosupramolecular squares [[10], [11], [12], [13]–18] of high-tech applications. Conformationally rigid tetranuclear [2 × 2] square grid complexes remain a popular research area in synthetic coordination chemistry and the products are very stable by non-covalent interactions. The inclusion of magnetic metal ions and formation of nanometer-sized magnetic clusters like single molecule magnets added another dimension to carbohydrazone based complexes [17]. There are only few reports on the Mn(II) complexes of biscarbohydrazones [[14], [15]–16] and are all molecular squares. The structural aspects and the chemistry of Mn(II) complexes of thiocarbohydrazones are yet to be explored, which might be due to susceptibility of the resultant species to decompose or difficulty in yielding single crystals. There are no reports of crystal structure study of Mn(II) bisthiocarbohydrazone complex so far, to the best of our knowledge. Mn(II) ions are considered as hard and show maximal stability with hard oxygen donors, which is reflected in their self-assembled oxygen bridged carbohydrazone square grid formation. Thiocarbohydrazones, however, have soft sulfur atom in place of oxygen, which may be less favourable for bridging Mn(II) centres compared to their carbohydrazone counterparts. Here, we have successfully isolated single crystals of two crystallographically different Mn(II) complexes from three different sources of solutions of a novel Mn(II) complex. As a continuation of our study on (thio)carbohydrazone complexes and their anticancer potentials, we report the structural aspects of the Mn(II) complexes derived from a ditopic bisthiocarbohydrazone ligand. The density functional theory calculations of both the ligand and the complexes are performed to support the experimental study. Moreover, in silico molecular docking studies of the ligand and the complex with B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2 and SARS-CoV-2 main protease are investigated.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

2-Benzoylpyridine (Aldrich), thiocarbohydrazide (Aldrich), MnCl2• 4H2O (Fluka), HCl (Rankem), methanol (Merck), DCM (S.D. Fine), chloroform (S.D. fine), etc. were used as received.

2.2. Synthesis

The ligand H2L was synthesized by the condensation between thiocarbohydrazide with 2-benzoylpyridine in 1:2 molar ratio as reported previously [18–20]. The synthesis of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1) was done by the reaction between an equimolar ratio of ligand and metal salt in neutral medium. A solution of MnCl2• 4H2O (0.99 g, 0.5 mmol) in 10 ml of methanol was added to a solution of H2L (0.218 g, 0.5 mmol) in 10 ml chloroform and refluxed for 2 h and allowed to stand at room temperature. Orange coloured product separated out after two days was filtered, washed with ether and dried. Recrystallized in ethyl acetate and dried over P4O10 in vacuo. Yield: ~ 64%. Elemental Anal. Found (Calc.): C, 51.64 (51.74); H, 3.16 (3.82); N, 14.55 (14.48); S, 6.12 (5.52)%. FT-IR: 1233 (ν(C=S)), 3560 (ν(H2O)), 3280, 3450 (ν(N–H)), 1630, 1595, 1515, 1468, 1440 (ν(C=N)+ ν(C=C)), 1350, 1392 (ν(C–N)/ νheterocyclic), 1148, 1072 (ν(N–N)), etc. The crystals of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) were formed from a solution of the complex 1 in chloroform on slow evaporation. FT-IR spectra of the complexes 1 and 1a are given in the supporting file as Fig. S1.

2.3. Methods and instrumentation

CHNS analysis of the compound was carried out using an Elementar Vario EL III CHNS analyzer at SAIF, Kochi, India. Electronic spectra (200–900 nm) were recorded on a UV-Thermo scientific evolution 220 spectrometer. Infrared spectra in the range 4000–400 cm−1 were recorded on a JASCO FT-IR 4100 spectrometer with KBr pellets at the Department of Applied Chemistry, CUSAT, Kochi.

2.4. X-ray crystallography

The single crystal X-ray diffraction data of the complexes 1 and 1a were collected at 296(2) K using Bruker SMART APEXII CCD diffractometer, equipped with graphite-crystal incident beam monochromator, and a fine focus sealed tube with Mo Kα (λ = 0.71073 Å) and the X-ray source at the SAIF, Kochi, India. The Bruker SMART software and Bruker SAINT software were used for data acquisition and data reduction, respectively. The structures were solved by direct methods and refined by full-matrix least-square calculations with the SHELXL-2018/3 software package [21]. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically, and all hydrogen atoms on carbon were placed in calculated positions, guided by difference maps and refined isotropically. One of the Cl atoms of the complex 1 is disordered with occupancies 64 and 36% and the disorder was resolved using PART instruction. Also, we could not locate the hydrogen atoms of the water molecule. The molecular and crystal structures were plotted using ORTEP [22], PLATON [23], Mercury [24] and Diamond 3.2 k [25] programs. The crystallographic data along with details of structure refinement parameters of both the complexes are given in the Table 1 . Selected bond lengths and bond angles are listed in the Table 2 .

Table 1.

Crystal refinement parameters of the complexes [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) and [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a).

| Parameters | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) |

|---|---|---|

| CCDC number Empirical Formula |

2086573 C25H20Cl2MnN6OS |

2044372 C26H21Cl5MnN6S |

| Formula weight (M) | 578.37 | 681.74 |

| Temperature (T) | 296(2) K | 296(2) K |

| Wavelength (Mo Kα) | 0.71073 Å | 0.71073 Å |

| Crystal system | triclinic | monoclinic |

| Space group | P | P21/n |

| Unit cell dimensions |

a = 9.2111(7) Å α = 63.927(3)° b = 12.3698(8) Å β = 70.802(3)° c = 13.6122(10) Å γ = 87.115(3)° |

a = 14.2205(11) Å α = 90° b = 14.0542(9) Å β = 100.466(3)° c = 15.4581(13) Å γ = 90° |

| Volume V, Z | 1307.52(17) Å3, 2 | 3038.0(4) Å3, 4 |

| Calculated density (ρ) | 1.469 g/cm3 | 1.491 g/cm3 |

| Absorption coefficient, μ | 0.820 mm−1 | 0.971 mm−1 |

| F(000) | 590 | 1380 |

| Crystal size | 0.30 × 0.20 × 0.15 mm | 0.35 × 0.30 × 0.20 mm |

| Limiting Indices | -12 ≤ h ≤ 12, -12 ≤ k < = 16, -16 ≤ l < = 18 |

-18 ≤ h ≤ 18, -18 ≤ k < = 16, -20 ≤ l < = 19 |

| Reflections collected | 16128 | 24880 |

| Independent Reflections | 6480[R(int) = 0.0273] | 7532[R(int) = 0.0280] |

| Refinement method | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 | Full-matrix least-squares on F2 |

| Data / restraints / parameters | 6481/2/343 | 7532/2/360 |

| Goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.027 | 1.000 |

| Final R indices [I > 2σ (I)] | R1 = 0.0437, wR2 = 0.1181 | R1 = 0.0430, wR2 = 0.1091 |

| R indices (all data) | R1 = 0.0713, wR2 = 0.1363 | R1 = 0.0842, wR2 = 0.1323 |

| Largest difference peak and hole | 0.506 and -0.551 e Å−3 | 0.621 and -0.428 e Å−3 |

R1 = Σ||Fo| - |Fc|| / Σ|Fo| wR2 = [Σw(Fo2-Fc2)2 / Σw(Fo2)2]1/2

Table 2.

Selected bond lengths (Å) and bond angles (˚) of [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) (bond parameters involving minor component of atom Cl2 is ignored) and [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a).

| Bond lengths (Å) | Bond angles (˚) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) | ||

| S1–C7 | 1.679(2) | 1.683(2) | N1–Mn1–N2 | 70.83(7) | 70.41(8) |

| N2–C6 | 1.282(3) | 1.287(3) | N1–Mn1–Cl1 | 98.33(6) | 97.56(6) |

| N5–C8 | 1.283(3) | 1.294(3) | N1–Mn1–Cl2 | 100.68(14) | 101.78(6) |

| N2– N3 | 1.355(3) | 1.363(3) | N1–Mn1–S1 | 141.02(6) | 140.26(6) |

| N4–N5 | 1.373(3) | 1.367(3) | N2–Mn1–Cl1 | 147.54(6) | 145.63(6) |

| N3–C7 | 1.335(3) | 1.339(3) | N2–Mn1–Cl2 | 96.4(4) | 101.25(5) |

| N4–C7 | 1.339(3) | 1.341(3) | N2–Mn1–S1 | 74.51(5) | 74.61(6) |

| Mn1–S1 | 2.6115(7) | 2.6311(9) | S1–Mn1–Cl1 | 101.42(3) | 100.80(3) |

| Mn1–N1 | 2.244(2) | 2.259(3) | S1–Mn1–Cl2 | 100.35(16) | 102.99(3) |

| Mn1–N2 | 2.246(2) | 2.2489(19) | Cl1–Mn1–Cl2 | 115.9(4) | 112.85(3) |

| Mn1–Cl1 | 2.3350(7) | 2.3325(8) | |||

| Mn1–Cl2 | 2.306(4) | 2.3445(8) | |||

2.5. Theoretical study

The DFT calculations were performed using Gaussian 09 program package [26] and GaussView 5.09 molecular visualization programs [27] at computational chemistry facility lab, DAC, CUSAT, Kochi, India. Geometry optimizations and frequency calculations of the ligand and the complex were performed at B3LYP/6-311G (d,P) and LanL2DZ level of theories, respectively using Becke's three-parameter hybrid functional [28] with the Lee et al. correlation functional [29], a combination that gives rise to the well-known B3LYP method. The electronic absorption wavelengths were calculated by time-dependent density functional theory (TD-DFT) [30] in chloroform/methanol media for the first hundred singlet states and was modelled by conductor-like polarizable continuum model (CPCM) [31].

2.6. Molecular docking study

The molecular docking studies were performed using AutoDock Tool (ADT) version 1.5.6 software [32]. The cif format files were converted to pdb files using mercury software. The receptor binding sites of B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2 (Protein Data Bank (PDB) ID: 1BNA) [33], and SARS-CoV-2 main protease (PDB ID: 6LU7) [34] were obtained from the Protein Data Bank [35]. Visualization of docked poses were done by using Discovery Studio and Pymol softwares.

3. Results and discussion

An equimolar ratio of the ligand 1,5-bis(2-benzoylpyridine) thiocarbohydrazone and the metal salt resulted into the formation of the mononuclear complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1), which was confirmed by single crystal X-ray diffraction studies and supported by elemental analysis, infrared and electronic spectral studies. As the possible sulfur bridged Mn(II) thiocarbohydrazones are not very stable like their oxygen counterparts, we tried to get single crystals from the mother solution itself. However, the single crystals obtained from mother solutions of the complex 1 layered with THF or ethyl acetate were found triclinic and same and confirms the mononuclear complex formation only. Though, a solution of the complex 1 in chloroform yielded crystals in monoclinic, single crystal XRD studies reveal a crystallographically different, but mononuclear complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a).

FT-IR spectra of the complexes 1and 1aexhibited a band at 1233 cm−1 attributed to ν(C=S) frequency (calculated 1272 cm−1) indicating thione coordination and absence of bands at ~ 2600 cm−1 is indicative of absence of thiol tautomer in free or coordinated forms [20]. The complex 1ashows additional bands at 2985 (calculated 3128), 1070 cm−1 (calculated 1280 cm−1) indicating ν(C–H) and δ(C–H) of chloroform. For the complex 1, an additional band at 3560 cm−1 (calculated 3658 cm−1) is observed in the broadened region and is attributed due to lattice water. The DFT calculated vibrational frequencies are as expected, since they are normally higher than that of experimental solid state IR spectrum and the optimization is done in gas phase and not involving hydrogen bonding and other intermolecular interactions in the crystal lattice. The comparatively large variation for the vibrational bands of chloroform is because of the C26–H26···Cl2 hydrogen bonding, as evidenced by the crystal structure results. The solution phase electronic spectra of the complex 1 as methanol, chloroform and dichloromethane solutions (0.25 × 10−5 M) were recorded (Fig. 1 ). The free ligand H2L as a methanol solution exhibit λmax at 346 nm, assigned as intraligand n→π* transition mainly due to thiocarbonyl group. This band is slightly shifted to 350 nm for complex 1 in methanol solution, and have suffered more red shift (to 358 nm) in chloroform and dichloromethane solutions. The UV-Vis spectrum of 1 as methanol solution shows bands, λmax (ε) at 250sh (262400), 275sh (214800), 350 (342400) and 425 nm (196800 M−1 cm−1). The intensity of the band at 425 nm is indicative of possible charge transfer transition in the complex. The ground state for an Mn(II) ion having d5 configuration is 6 A 1g and the transitions from this state is doubly forbidden. The crystal field of any symmetry is unable to split this ground state. The molar absorptivity of the band at 425 nm is higher compared to possible 4 T 2g←6 A 1g transition [36], characteristic of Mn(II) complexes. The band is not obscured by intraligand transition [37] also. The band is thus assigned due to metal to ligand charge transfer transition, most probably, to thione sulfur atom of the ligand. This band is absent in the dichloromethane and chloroform solution spectra of the complex 1, probably indicating weakening of Mn(II)–S coordinate bond of the complex 1 in these solutions.

Fig. 1.

Electronic spectra of the complex 1 (0.25 × 10−5 M in methanol, chloroform, and dichloromethane solutions) and that of the free ligand in methanol solution.

Solid state UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectrum of the complex 1 is plotted with Kubelka-Munk model (Fig. 2 ), which shows a very high intense band at ca 320 nm. Intraligand transition is expected in this region, but the enhanced intensity may be due to charge transfer transition most probably originating from chloride to the coordinated ligand H2L. The band at ca 420 nm may be attributed to the charge transfer originating from Mn(II) ion to thione sulfur atom. This is in agreement with the methanol solution electronic spectrum of the complex 1. The direct band gap (Eg) of the complex was estimated as 2.45 eV using the graph plotted with (hνF(R))1/2 versus photon energy (hν), where F(R) is Kubelka-Munk function [F(R) = (1-R)2/2R]. This low band gap of the complex is indicative of semi-conductor characteristics and probably the material would be useful for photovoltaic applications.

Fig. 2.

UV-Vis diffuse reflectance spectrum of the complex 1. The inset shows the band gap from Kubelka-Munk as a function of energy (eV).

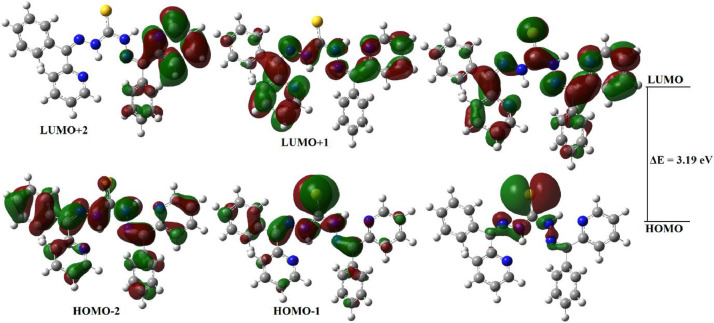

3.1. Crystal structures of [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) and [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a)

Single crystals of the complex 1 were isolated by slow evaporation from a mixture of the mother solution layered with THF or ethyl acetate. Suitable crystals of complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) was obtained from a solution of the complex 1 in chloroform on slow evaporation. Both the complexes adopt a five coordinated geometry around the Mn(II) ion center. The molecular structure of the complex 1a and the relevant atom numbering scheme used for both the complexes is given in Fig. 3 . Though one of the chlorido ligand in complex 1 is disordered, the inner coordination sphere of both the complexes are similar. The Mn(II) centre is coordinated by the neutral ligand using cis pyridyl nitrogen N1, trans azomethine nitrogen N2 and cis thione sulfur S1 atoms. The thiocarbohydrazone moiety shows a E, Z configuration about the C6–N2 and C8–N5 double bonds with the two pyridine rings, which is different from the Z, Z form of the free ligand [18], [19]. This change in conformation of the ligand facilitates the NNS coordination to the Mn(II) center.

Fig. 3.

ORTEP diagram of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) in 50% probability ellipsoids, showing intramolecular hydrogen bonding interactions also.

The geometry index values calculated for the complex 1 (τ = 0.1080) and 1a (τ = 0.0895) indicate square pyramidal geometry around Mn(II) ions [38]. The coordination of thione form of sulfur was confirmed by the double bond nature of the C7–S1 (1.679(2) Å for the complex 1 and 1.683(2) Å for 1a) [39,40] and single bond nature of N3–C7 (1.335(3) Å and 1.339(3) Å for the complexes 1 and 1a, respectively) and N4–C7 (1.339(3) Å and 1.341(3) Å for complexes 1 and 1a, respectively) bonds. The C–S bond distance is not much varied from the C=S distance (1.649(4) Å) of the free ligand [18] also. The Mn–Nazo and Mn–Npy lengths are comparable with previously reported Mn(II) thiosemicarbazone complexes [40–42]. The Mn–S distances (2.6115(7) Å and 2.6311(9) Å for the complexes 1 and 1a, respectively) are in agreement with thione coordination with Mn(II) ions [40] and longer than the Mn–S bonds observed in the Mn(II) thiosemicarbazones with deprotonated thiolate form of sulfur [41–43]. The N1, N2 and S1 atoms along with a chlorine atom Cl1 constitute the square base, while the chlorine atom Cl2 occupies the axial site in both the complexes. The basal plane shows a very slight distortion and is more in complex 1a as Mn1 is -0.5023(4) Å out of the same plane towards the chlorine Cl2 atom. The metal centre is shared by two fused five membered chelate rings in both the complexes. The planes comprising Mn1, S1, C7, N3, N2 and Mn1, N1, C5, C6, N2, with a maximum deviation from the mean plane of 0.1501(19) Å for N2 and 0.030(2) Å for N1, respectively, make an angle of 15.81(8) in the complex 1a. In the complex 1, these deviations are maximum for N2 (0.178(2) Å) and C6 (-0.045(3) Å), respectively as the same planes make an angle of 15.35(10).

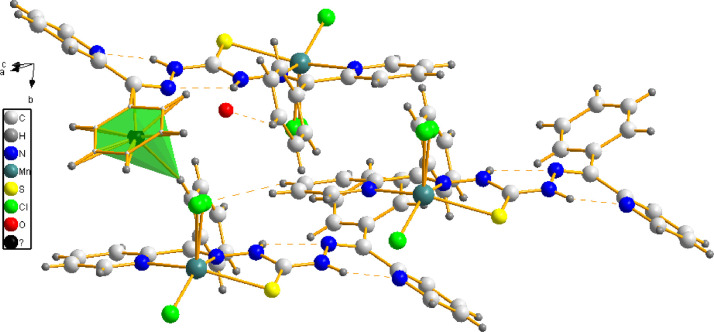

Two intramolecular hydrogen bonds N3–H3A···N5 and N4–H4A···N6 are seen in both the complexes, which provide additional stability to the complex molecules. Relevant hydrogen bonding interactions and the significant C–H···π interaction (Fig. 4 ) in the packing of the crystal lattice of the complex 1 are listed in Table S1. In the complex 1a, the Cl2 atom is engaged in hydrogen bonding with the hydrogen atom H26 of the solvent chloroform with H···Cl distance of 2.54 Å and C26–H26···Cl2 angle 161. The complex 1a molecules are connected in the crystal lattice through intermolecular hydrogen bonds C11–H11···Cl2 (symmetry code: 3/2-x, 1/2+y,-1/2- z; with a H···Cl distance of 2.78 Å and angle 153°) and C12–H12···Cl1 (symmetry code: -1+x, y, z; with a H···Cl distance of 2.80 Å and angle 136°) and leading to three dimensional network (Fig. S2). The hydrogen bonds and significant C–H···π and C–Cl···π interactions found in complex 1a (Fig. S3) are listed in Table S2. Here, both the chlorido ligands and the chlorine atoms of the solvent chloroform play a significant role in the crystal structure cohesion. For the complex 1, however, only one intermolecucular C–H···Cl interaction (C3–H3···Cl2 (symmetry code: 1+x, y, z; with a H···Cl distance of 2.76 Å and angle 144°) is present along with a C23–H23···O1S (with a H···O distance of 2.49 Å and angle 143°) interaction involving lattice water. The π···π interactions observed are all weak in the lattice of both the complexes, also reinforces the crystal structure cohesion in their packing.

Fig. 4.

The C–H···π and relevant inter and intra molecular hydrogen bonding interactions in the crystal lattice of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1).

3.2. Hirshfeld surface analysis of [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) and [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a)

The Hirshfeld surface characteristics of both the complexes are analyzed and the intermolecular interactions in the crystal packing are quantified using the Crystal Explorer 17.5 [44] software. Hirshfeld surface of [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) was generated after modelling the structure by manually removing the disordered component of Cl2 and putting full occupation for the major Cl2A component in the CIF. Hirshfeld dnorm, shape index and curvedness surfaces of the complexes 1 and 1a are given in Figs. 5 and 6 , which provide an insight about the electron density distribution among the molecular fragments. In the dnorm Hirshfeld surface, contacts with distances equal to the sum of the van der Waals radii are represented as white regions and the contacts with distances shorter than and longer than van der Waals radii are shown as red circles and blue areas, respectively. The dnorm surface is used to identify very close intermolecular interactions and are observed as red coloured spots [45,46]. The blue region around H19 on the bottom middle and the red regions near phenylene rings over the mapped Hirshfeld shape index properties of 1a (marked regions in Fig. 6) indicate C–H···π interactions in the crystal lattice. Similarly, for the complex 1 the blue region around H25 and red region on the phenylene ring as marked in Fig. 5 indicate strong C–H···π interactions. Hirshfeld surfaces with high curvedness, which is highlighted as dark-blue edges, reveals absence of significant π···π stacking in the lattice of both the complexes. However, very weak π···π stacking interactions present may be seen as red and blue triangles on the same region of the shape index surface and flat regions on the curvedness surfaces. Fig. 7 illustrates the dominant interacting surfaces observed for the complexes, which are due to isotropic van der Waals forces (H···H interactions) for the complex 1 and H···Cl/Cl···H intermolecular hydrogen bonding interactions for the complex 1a. These measures of curvature provide clear insight on molecular packing in the crystal lattice [46] of both the complexes.

Fig. 5.

dnorm surface view, shape index and curvedness of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2].H2O (1).

Fig. 6.

dnorm surface view, shape index and curvedness of complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2].CHCl3 (1a).

Fig. 7.

The dominant interacting Hirshfeld surfaces observed for the complexes due to (a) H···Cl/Cl···H intermolecular connections for the complex 1a and (b) isotropic H···H van der Waals forces for the complex 1.

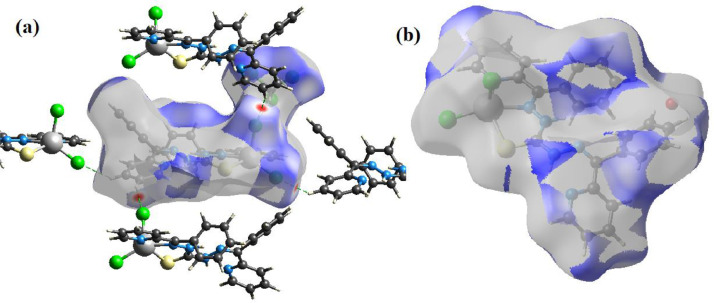

To analyse and to quantify the nature of different intermolecular interactions inside the crystal the 2D fingerprint plots are mapped for both the complexes and are given in Figs. 8 and 9 . The plots reveal the percentage of contacts contributed to the total Hirshfeld surface area of that complex. For complex 1a, it is found that H···Cl/Cl···H contacts are the main intermolecular interaction (33.1%) and is reflected on both sides of the scattered point of the 2D finger print plot. The isotropic van der Waals forces (H···H interactions, 27.9%) in the middle of the scattered point of the 2D fingerprint plot are one of the most significant contacts, which is followed by C···H/H···C interactions (15.2%). The relative contribution of other significant interactions observed are C···Cl/Cl···C (5.0%), S···H/H···S (4.0%), N···H/H···N (3.8%), N···Cl/Cl···N (3.2%), etc. C···C interactions are not significant and indicate lack of π···π stacking interactions. However, the significant C···H/H···C interactions can be considered as a measure of C–H···π interactions and is found very strong, reinforces the crystal structure cohesion. For the complex 1, however, the van der Waals forces play the dominant role as evidenced by greater H···H interactions (31.3%) contribution to the total Hirshfeld surface. The relative contributions from C···H/H···C (20.1%) and Cl···H/H···Cl (16.6%) interactions are found very significant among other contributions like N···H/H···N (6.8%), O···H/H···O (6.3%), S···H/H···S (4.7%), Cl···O/O···Cl (2.7%), C···C (2.6%), etc. in the crystal packing. The role of H⋯H interactions in the stabilization of crystal structure is, however, quite small in importance because these interactions are between the same species. The C···H/H···C interactions, a measure of C–H•••π interactions, are found very strong in the complex 1 and reinforces the crystal structure cohesion, though the weak C···C interactions indicating that the π•••π stacking is not very significant. Also, the analyses reveal the absence of any kind of intermolecular contacts involving the central metal atom in both the complexes.

Fig. 8.

2D finger print plots of compound 1a showing the percentage of significant contacts contributed to the total Hirshfeld surface area.

Fig. 9.

2D finger print plots of the complex 1 showing the percentage of significant contacts contributed to the total Hirshfeld surface area.

3.3. Theoretical study of the ligand and the complexes [Mn(H2L)Cl2]

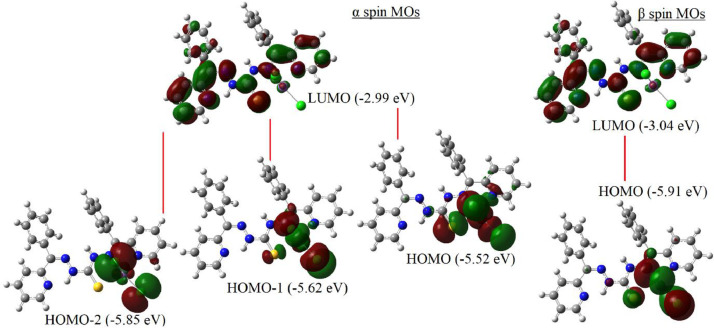

3.3.1. Frontier molecular orbital (FMO) analysis

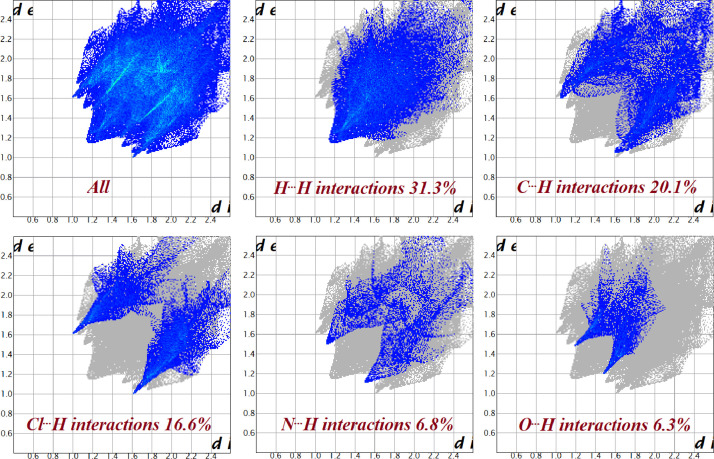

The geometry optimisation of the ligand H2L and its Mn(II) complexes was performed by B3LYP/6-311G(d,p) and B3LYP/LanL2DZ levels of DFT using the geometric coordinates of the crystal structures. The FMO energies and the FMO energy gap (EHOMO–ELUMO: ΔE) are the important parameters of molecular electronic structure. Relevant frontier molecular orbital energies and the calculated band gap of the compounds along with the chemical reactivity parameters [47] like electron affinity, electronegativity, ionization energy, chemical hardness, softness, chemical potential, electrophilicity and nucleophilicity are listed in Table 3 . Also, the relevant occupied and unoccupied MO electron densities calculated for the ligand and the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2] are given in Fig. 10, Fig. 11 .

Table 3.

The Frontier molecular orbital energies and calculated chemical reactivity parameters for the compounds.

| Energy parameters (eV) | H2L | [Mn(H2L)Cl2] | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) | [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1) in chloroform |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HOMO | -5.43 | -5.52 (α) | -5.47 (α) | -5.70 (α) | -7.81(α) |

| HOMO-1 | -5.57 | -5.62 (α) | -5.54 (α) | -5.81 (α) | -7.89(β) |

| LUMO | -2.24 | -3.04 (β) | -3.06 (β) | -3.16 (β) | -1.93(β) |

| LUMO+1 | -1.73 | -2.99 (α) | -3.03 (α) | -3.11 (α) | -1.87(α) |

| EHOMO–ELUMO: ΔE | 3.19 | 2.48 | 2.41 | 2.54 | 5.88 |

| Ionization Energy, I | 5.43 | 5.52 | 5.47 | 5.70 | 7.81 |

| Electron Affinity, A | 2.24 | 3.04 | 3.06 | 3.16 | 1.93 |

| Chemical hardness, η | 1.60 | 1.24 | 1.21 | 1.27 | 2.94 |

| Electronegativity, χ | 3.84 | 4.28 | 4.27 | 4.43 | 4.87 |

| Chemical potential, μ | -3.84 | -4.28 | -4.27 | -4.43 | -4.87 |

| Electrophilicity, ω | 4.60 | 7.38 | 7.55 | 7.73 | 4.03 |

| Total Energy | -1691.69 | -1437.08 | -1513.49 | -1520.59 | -1512.60 |

| Global softness, σ (eV−1) | 0.63 | 0.81 | 0.83 | 0.79 | 0.34 |

| Nucleophilicity, ε (eV−1) | 0.22 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.25 |

| Dipole moment (Debye) | 7.80 | 18.37 | 19.47 | 18.54 | 23.86 |

Fig. 10.

Relevant frontier molecular orbitals of the thiocarbohydrazone H2L.

Fig. 11.

Relevant frontier molecular orbitals of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2] in gas phase.

The HOMO electron densities of H2L are distributed mainly over the sulfur atom and partially over the nitrogen atoms of the thiocarbohydrazide moiety, while the LUMO electron densities are distributed over the entire thiocarbohydrazone including the thiocarbonyl carbon. The relatively higher HOMO energy characterizes the electron giving ability of H2L and energy gap of 3.19 eV between HOMO and LUMO indicates the molecular chemical stability. Also, the chemical hardness (η = 1.60 eV) and small HOMO-LUMO gap indicate that the molecule is soft. The total energy of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2] in gas phase is only -1437.08 eV and is not very favorable compared to that of the free ligand (-1691.69 eV). Also, the HOMO energy of the Mn(II) complex is calculated as -5.52 eV and the LUMO energy is calculated as -3.04 eV. The small energy gap between HOMO and LUMO (2.48 eV) indicates that charge transfer may occurs within the Mn(II) complex, and Mn(II) complex can easily be polarized (global softness, σ = 0.81 eV−1). Also, TD-B3LYP/CPCM calculations indicate that the Mn(II) complex is more stable (chemically hard) in methanol or chloroform solutions than the complex in gas phase, which may attributed due to solvation.

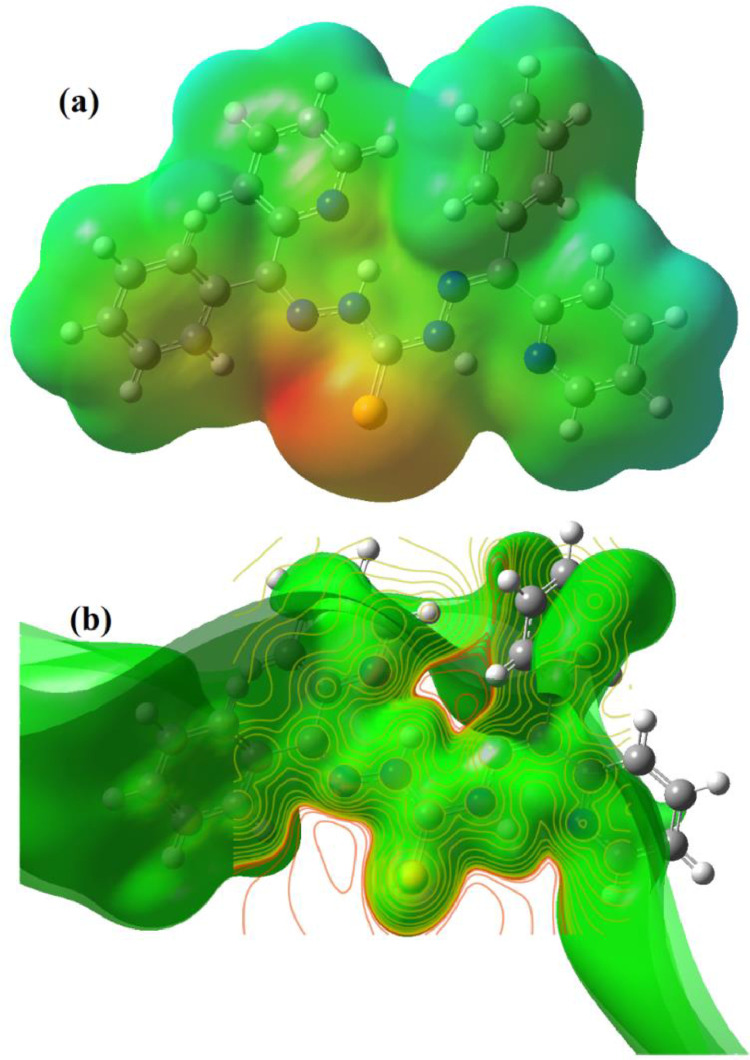

3.3.2. Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) surfaces

The calculated molecular electrostatic potential surfaces of the ligand H2L and the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2] are given in Fig. 12, Fig. 13 , which illustrates the three-dimensional charge distributions within the molecules [48]. The positive and negative charged electrostatic potential regions in the molecule provide an insight about the various interactions between the molecules. Also, these electrostatic potential mapping onto the iso-electron density surface displays molecular size and shape and is a very useful tool in the correlation study of molecular structure of bio molecules or drugs and their physiochemical properties [49]. A high electrostatic potential or the blue coloured region indicates the relative absence of electrons or partially positive charge, light blue region indicates slight electron deficiency, green shows neutral (zero potential), yellow shows slight electron richness, and a low electrostatic potential or red coloured region indicates an abundance of electrons [50,51].

Fig. 12.

(a) Molecular electrostatic potential (MEP) and (b) the contour over the electrostatic potential map of the ligand H2L.

Fig. 13.

(a) The MEP surface and (b) spin density distribution of the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2].

The red and yellow coloured negative region of the MEP surface of the ligand H2L is associated with the lone pair of electronegative atoms, indicate the Lewis base region and is prone to electrophilic attack or coordination to metal centers. The positive slight blue region is seen near the NH protons and is indicative of relative absence of electrons there. The ESP surfaces also indicate the soft nature of the ligand as well as a preference for NNS coordination. For the Mn(II) complex the most negative potential are over the electronegative chloride ligands, then on sulfur atoms as evidenced by yellow coloured region. The most positive regions are over the hydrogen atoms, while the carbon atoms are seem to have zero potential. The spin density distribution plot of the complex demonstrates that the central Mn(II) atom carries the main spin density along with the donor atoms, which are directly bonded to it. The spin density delocalisation occurs through the metal- ligand bonds, as expected, to the nearby region of the complex. However, most of the regions around the carbon atoms carry a negative spin density and only the coordinating atoms play a significant part in the propagation of spin density.

3.3.3. Theoretical UV-Vis spectral study

The theoretical calculation of UV-Vis spectra of both the ligand and the complex were carried out and are found to exhibit the main characters of the experimental spectra. An interesting aspect in the simulated gas phase UV-Vis spectrum for the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2] observed is that the electronic transition corresponding to 443.25 nm (2.79 eV) is found to have a significant oscillator strength and α contributions only (with major transition types (HOMO)α→(LUMO)α and (HOMO)α→(LUMO+1)α). This may be attributed to the band observed at λmax ~ 420 nm for the solid state and methanol solution experimental electronic spectra. The disappearance of this transition with CPCM modelling may be indicative of weakening of coordinate bond, mainly Mn(II)–S, due to solvation. The calculated major electronic transitions, oscillator strength (f), major type of transition and their coefficient for both the ligand H2L and the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1) in solutions are listed in Table 4 . The theoretical λmax values are found corroborating with the experimental results.

Table 4.

The calculated major electronic transitions, oscillator strength (f), major type of transition and their coefficient for the ligand H2L (in methanol) and the complex (in chloroform) calculated at UCAM -B3LYP TD FC (6-311G (d,P) and LanL2DZ basis sets for H2L and the complexes, respectively).

| Compound | E(eV)/ λ(nm) | f | Major Type | Coefficient | Theoretical λmax (nm) | Experimental λmax (nm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H2L |

3.61/ 343.04 | 0.80 | (HOMO)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO-1)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-1)β→(LUMO)β |

0.52 0.52 0.32 0.32 |

337 | 346 |

| 3.67/ 337.99 | 0.18 | (HOMO-2)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-2)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO)β→(LUMO)β |

0.54 0.54 0.33 0.33 |

|||

| 3.91/ 316.73 | 0.33 | (HOMO-1)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-1)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO-2)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-2)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO)β→(LUMO)β |

0.53 0.53 0.26 0.26 0.25 0.25 |

270 | ||

| 5.12/ 242.12 | 0.23 | (HOMO-2)α→(LUMO+1)α (HOMO-2)β→(LUMO+1)β (HOMO-6)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-6)β→(LUMO)β |

0.35 0.35 0.25 0.25 |

235 | 242 | |

| 5.50/ 225.39 | 0.15 | (HOMO)α→(LUMO+4)α (HOMO)β→(LUMO+4)β (HOMO-1)α→(LUMO+4)α (HOMO-1)β→(LUMO+4)β |

0.37 0.37 0.34 0.34 |

|||

| [Mn(H2L)Cl2]• H2O (1) | 3.67/ 338.18 | 0.76 | (HOMO)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO-1)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO)α→(LUMO)α |

0.58 0.38 0.34 |

335 | 350 |

| 3.69/ 335.95 | 0.29 | (HOMO-2)α→(LUMO)α (HOMO-18)α→(LUMO)α |

0.47 0.20 |

|||

| 3.79/ 327.45 | 0.22 | (HOMO-1)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO-2)α→(LUMO)α |

0.57 0.41 |

247 | 275 | |

| 5.00/ 247.73 | 0.17 | (HOMO-10)β→(LUMO)β (HOMO-11)α→(LUMO)α |

0.36 0.36 |

250 |

3.4. Molecular docking study of H2L and the complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]

Molecular docking is generally considered for sensible design of drug entities that recognise the preferred binding sites of nucleic acids and proteins, which anticipates the presence of various noncovalent interactions. A comparative study of the docking of the ligand and the Mn(II) complex are investigated here for knowing their biological potentials.

3.4.1. Interaction with B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2

As DNA is the primary intracellular target of an anticancer drug [52], the docking studies were conducted to predict the binding efficiency of the H2L and Mn(II) complex with the active site residues of B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2. The crystal structure of 1BNA [33] obtained from protein data bank at a resolution of 1.9 Å is taken and the receptor was prepared by deleting all the heteroatoms including water and by adding polar hydrogen atoms. The Mn(II) complex shows better binding capability with docking energy (-9.31 kcal/mol) than the ligand H2L (-8.87 kcal/mol) and probably a useful candidate for therapeutic purposes. Docking study suggest that the DNA is efficiently binds with H2L mainly through various hydrogen bonding interactions, of which one of the hydrogen bonds is very strong (d = 1.86 Å) with 153.3o donor-hydrogen-acceptor (D–H··· A) angle. For Mn(II) complex, however, various electrostatic interactions play the crucial role in DNA binding. The docking studies reveal that both the compounds fit comfortably in the curved shape of the DNA target and exhibit a minor groove mode of binding (Fig. 14 ). Many of the anticancer candidates bind with grooves of DNA double-strand, which leads to interrupt DNA function and alter the cell division by interfering with replication and transcription [53]. Relevant hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions are listed in the Table 5 .

Fig. 14.

Molecular docking interactions of (a) Mn(II) complex and (b) H2L with 1BNA.

Table 5.

Docking energy and interactions of the compounds with 1BNA.

| Compound | Docking energy (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding interactions | Hydrophobic/electrostatic interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

H2L |

-8.87 |

DG4(N2): N2 DG22(N2): N5 DC23(O4′): H4(N4) DG22(C4′): N1 | DC23(C4′): Py2 (C-H‧‧‧π) DC21: Phe1 (π‧‧‧π) |

|

[Mn(H2L)Cl2] |

-9.31 |

DA17(O3): S1 |

DC11(OP1): N4 DC11(O4’): H4(N4) DA17(OP1): Py1 DA18(OP2): Cl1 DG12(OP2): Cl2 |

Py1 = Pyridyl ring 1, Py2 = Pyridyl ring 2, Phe1 = Phenyl ring 1

3.4.2. Interaction with SARS-CoV-2 main protease

The main protease of coronaviruses is an essential enzyme Mpro or 3CLpro , which has a pivotal role in the replication and transcription of virus, and constitutes one of the best characterised drug targets for SARS-CoV-2 [34]. Studies are progressing in the development of new drug candidates other than chloroquine (CQ) and its hydroxyl analog hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) [3,5,6] in several directions for different type of patients [7]. Here, the in silico molecular docking computational tool identifies the binding potentials of H2L and its Mn(II) complex with the main protease of SARS-CoV-2. The ligand binding efficiency of the enzyme-H2L (-9.76 kcal/mol) is found comparable with that of inhibitor cocrystal ligand (-9.48 kcal/mol) and better than those of CQ and HCQ (-7.04 kcal/mol and -7.58 kcal/mol, respectively). Mn(II) complex showed, however, excellent binding energy (-10.46 kcal/mol) by exhibiting a hydrogen bonding (GLU166(O): H4(N4)) and other nonbonding interactions with active site residues HIS-41, MET-49, CYS-145, MET-165, LEU-167, PRO-168 and GLN-189 (Table 6 ). Interactions of cocrystal ligand, HCQ, CQ, thiocarbohydrazone H2L and the Mn(II) complex at the active site of the protein are displayed in Fig. 15 . Also, the 2D diagram for the interaction of H2L and the Mn(II) complex with SARS-CoV-2 main protease are presented in Fig 16 . The study reveals that the novel Mn(II) bisthiocarbohydrazone complex may be considered as a useful drug candidate against SARS-CoV-2.

Table 6.

Docking energy and interactions of the compounds with 6LU7.

| Compound | Docking energy (kcal/mol) | Hydrogen bonding interactions | Groups involving hydrophobic/ electrostatic interactions |

|---|---|---|---|

|

H2L |

-9.76 |

CYS145(SG): N1 HIS164(O): H3(N3) GLN189(OE1): H4(N4) | MET-49, CYS-145, HIS-163, MET-165, GLU-166, PRO-168. |

|

[Mn(H2L)Cl2] |

-10.46 |

GLU166(O): H4(N4) |

HIS-41, MET-49, CYS-145, MET-165, LEU-167, PRO-168, GLN-189. |

Fig. 15.

Binding mode of (a) co-crystal ligand, (b) HCQ, (c) CQ, (d) H2L and (e) Mn(II) complex at the active site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

Fig. 16.

2D representation of (a) H2L and (b) Mn(II) complex at the active site of SARS-CoV-2 main protease.

4. Conclusion

A novel Mn(II) bisthiocarbohydrazone complex [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•H2O (1) is synthesized and characterised. Crystallization of the complex yielded crystals of [Mn(H2L)Cl2]•CHCl3 (1a) in monoclinic form and is found different from the triclinic crystal system of the complex 1 obtained from mother solution. This is the first crystal structure report of a manganese(II) complex of a bisthiocarbohydrazone ligand. The intermolecular interactions are studied and quantified using Hirshfeld surface analysis. It is found that the nature of the solvent inclusion plays a major role in the supramolecular assembly in the crystal lattice. To support the experimental data, quantum-chemical DFT studies of the bisthiocarbohydrazone ligand and the complexes are carried out. The ligand is found more stable than the Mn(II) complex in the gas phase, though the complex is more stable and chemically hard in solution phase through solvation. The electronic spectra of the ligand and the complex in solutions are also calculated using CPCM modelling at RTD-B3LYP-FC level of theory and is found corroborating with the experimental results. The solution phase and solid state electronic spectral results are indicative of weakening of Mn(II)–S coordinate bond in solutions, which is in accordance with DFT and single crystal XRD studies. Moreover, the thiocarbohydrazone H2L and the Mn(II) complex are subjected to molecular docking studies with the crystal structures of B-DNA dodecamer d(CGCGAATTCGCG)2 and SARS-CoV-2 main protease. The docking energy of the SARS-CoV-2 main protease with the novel Mn(II) complex (-10.46 kcal/mol) is found much better than that of chloroquine (-7.04 kcal/mol) and hydroxychloroquine (-7.58 kcal/mol) and the study offers a new drug candidate against COVID-19.

Supplementary material:

CCDC 2086573 and 2044372 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for the complexes 1 and 1a, which can be accessed free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via http://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures.

Declaration of Competing Interest

There are no conflicts to declare.

Acknowledgements

We thank Sophisticated Test and Instrumentation Centre (STIC), Cochin University of Science and Technology (CUSAT) for analysis. EM is thankful to CUSAT for SMNRI Grant (No.CUSAT/PL(UGC).A1/1112/2021) and MHKK is thankful to CSIR-India (CSIR File No.09/239(0565)/2020-EMR-I) for the award of JRF.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2021.131125.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Bonaccorso C., Marzo T., La Mendola D. Biological Applications of thiocarbohydrazones and their metal complexes: a perspective review. Pharmaceuticals. 2020;13:4. doi: 10.3390/ph13010004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pal M., Musib D., Roy M. Transition metal complexes as potential tools against SARS-CoV-2: an in silico approach. New J. Chem. 2021;45:1924–1933. doi: 10.1039/d0nj04578k. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haribabu J., Srividya S., Mahendiran D., Gayathri D., Venkatramu V., Bhuvanesh N., Karvembu R. Synthesis of palladium(II) complexes via michael addition: antiproliferative effects through ROS-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis and docking with SARS-CoV-2. Inorg. Chem. 2020;59:17109–17122. doi: 10.1021/acs.inorgchem.0c02373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Amritha B., Manaf O., Nethaji M., Sujith A., Kurup M.R.P., Vasudevan S. Mn(II) complex of a di-2-pyridyl ketone-N(4)-substituted thiosemicarbazone: versatile biological properties and naked-eye detection of Fe2+ and Ru3+ ions. Polyhedron. 2020;178 doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2019.114333. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aktas A., Tuzun B., Aslan R., Sayin K., Ataseven H. New anti-viral drugs for the treatment of COVID-19 instead of favipiravir. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2020 doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1806112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keretsu S., Bhujbal S.P., Cho S.J. Rational approach toward COVID-19 main protease inhibitors via molecular docking, molecular dynamics simulation and free energy calculation. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:17716. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-74468-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh A.K., Singh A., Shaikh A., Singh R., Misra A. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine in the treatment of COVID-19 with or without diabetes: a systematic search and a narrative review with a special reference to India and other developing countries. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Clin. Res. Rev. 2020;14:241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu J., Cao R., Xu M., Wang X., Zhang H., Hu H., Li Y., Hu Z., Zhong W., Wang M. Hydroxychloroquine, a less toxic derivative of chloroquine, is effective in inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 infection in vitro. Cell Discov. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-0156-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nair R.S., Manoj E., Thankappan R., Chandrika S.K., Kurup M.R.P., Srinivas P. Molecular trail for the anticancer behavior of a novel copper carbohydrazone complex in BRCA1 mutated breast cancer. Mol. Carcinog. 2017;56:1501–1514. doi: 10.1002/10.1002/mc.22610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manoj E., Kurup M.R.P., Fun H.K. Macrocyclic molecular square complex of zinc(II) self-assembled with a carbohydrazone ligand. Inorg. Chem. Commun. 2007;10:324–328. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2006.11.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manoj E., Kurup M.R.P., Fun H.K., Punnoose A. Self-assembled macrocyclic molecular squares of Ni(II) derived from carbohydrazones and thiocarbohydrazones: structural and magnetic studies. Polyhedron. 2007;26:4451–4462. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2007.05.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nicholas F., Randell M., Anwar M.U., Drover M.W., Dawe L.N., Thompson L.K. Self-assembled Ln(III)4 (Ln = Eu, Gd, Dy, Ho, Yb) [2 × 2] square grids: a new class of lanthanide cluster. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:6731–6742. doi: 10.1021/ic4008813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J., Xu G.C., Yu W.X., Jia D.Z. A carbohydrazone based tetranuclear Co(II) complex: self-assembly and magnetic property. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2014;45:40–43. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2014.03.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Drover M.W., Tandon S.S., Anwar M.U., Shuvaev K.V., Dawe L.N., Collins J.L., Thompson L.K. Polynuclear complexes of a series of hydrazone and hydrazone–oxime ligands – M2 (Fe), M4 (Mn, Ni, Cu), and Mn (Cu) examples. Polyhedron. 2014;68:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2013.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang L., Wang J.J., Xu G.C. The [2 × 2] grid tetranuclear Fe(II) and Mn(II) complexes: structure and magnetic properties. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2014;39:66–69. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2013.10.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bikas R., Hosseini-Monfared H., Siczek M., Demeshko Serhiy, Soltani B., Lis T. Synthesis, structure and magnetic properties of a tetranuclear Mn(II) complex with carbohydrazone based ligand. Inorg. Chem. Comm. 2015;62:60–63. doi: 10.1016/j.inoche.2015.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anwar M.U., Thompson L.K., Dawe L.N., Habib F., Murugesu M. Predictable self-assembled [2 × 2] Ln(III)4 square grids (Ln = Dy,Tb)—SMM behaviour in a new lanthanide cluster motif. Chem. Comm. 2012;48:4576–4578. doi: 10.1039/C2CC17546K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.He C., Duan C.Y., Fang C.J., Liu Y.J., Meng Q.J. Self-assembled macrocyclic tetranuclear molecular square [Ni(HL)]4+4 and molecular rectangle [Cu2Cl2L]2 {H2L _ bis[phenyl(2-pyridyl)methanone] thiocarbazone} J. Chem. Soc.Dalton Trans. 2000:1207–1212. doi: 10.1039/A909604C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacchi A., Carcelli M., Pelagatti P., Pelizzi C., Pelizzi G., Zani F. Antimicrobial and mutagenic activity of some carbono- and thiocarbonohydrazone ligands and their copper(II), iron(II) and zinc(II) complexes. J. Inorg. Biochem. 1999;75:123–133. doi: 10.1016/S0162-0134(99)00045-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Manoj E., Kurup M.R.P., Punnoose A. Preparation, magnetic and EPR spectral studies of copper(II) complexes of an anticancer drug analogue. Spectrochim. Acta Part A. 2009;72:474–483. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2008.10.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sheldrick G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C. 2015;71:3–8. doi: 10.1107/S2053229614024218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Farrugia L.J. WinGX and ORTEP for windows: an update. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2012;45:849–854. doi: 10.1107/S0021889812029111. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Spek A.L. Single-crystal structure validation with the program PLATON. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2003;36:7–13. doi: 10.1107/S0021889802022112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macrae C.F., Edgington P.R., McCabe P., Pidcock E., Shields G.P., Taylor R., Towler M., van de Streek J. Mercury: visualization and analysis of crystal structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 2006;39:453–457. doi: 10.1107/S002188980600731X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.K. Brandenburg, Diamond version 3.2k, Crystal Impact GbR, Bonn, Germany (2014), http://www.crystalimpact.com/diamond.

- 26.Frisch M.J., Trucks G.W., Schlegel H.B., Scuseria G.E., Robb M.A., Cheeseman J.R., Scalmani G., Barone V., Mennucci B., Petersson G.A., Nakatsuji H., Caricato M., Li X., Hratchian H.P., Izmaylov A.F., Bloino J., Zheng G., Sonnenberg J.L., Hada M., Ehara M., Toyota K., Fukuda R., Hasegawa J., Ishida M., Nakajima T., Honda Y., Kitao O., Nakai H., Vreven T., Montgomery J.A., Peralta J.E., Ogliaro F., Bearpark M., Heyd J.J., Brothers E., Kudin K.N., Staroverov V.N., Kobayashi R., Normand J., Raghavachari K., Rendell A., Burant J.C., Iyengar S.S., Tomasi J., Cossi M., Rega N., Millam J.M., Klene M., Knox J.E., Cross J.B., Bakken V., Adamo C., Jaramillo J., Gomperts R., Stratmann R.E., Yazyev O., Austin A.J., Cammi R., Pomelli C., Ochterski J.W., Martin R.L., Morokuma K., Zakrzewski V.G., Voth G.A., Salvador P., Dannenberg J.J., Dapprich S., Daniels A.D., Farkas O., Foresman J.B., Ortiz J.V., Cioslowski J., Fox D.J. Gaussian, Inc.; Wallingford CT: 2009. Gaussian 09, Revision A.1. [Google Scholar]

- 27.R. Dennington, T. Keith, J. Millam, GaussView, Version 5, Semichem Inc., Shawnee Mission, KS, (2009).

- 28.Becke A.D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:5648–5652. doi: 10.1063/1.464913. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee C., Yang W., Parr R.G. Development of the Colle-Salvetti correlation-energy formula into a functional of the electron density. Phys. Rev. B. 1988;37:785–789. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevB.37.785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scalmani G., Frisch M.J., Mennucci B., Tomasi J., Cammi R., Barone V. Geometries and properties of excited states in the gas phase and in solution: theory and application of a time-dependent density functional theory polarizable continuum model. J. Chem. Phys. 2006;124 doi: 10.1063/1.2173258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cossi M., Rega N., Scalmani G., Barone V. Energies, structures, and electronic properties of molecules in solution with the C-PCM solvation model. J. Comp. Chem. 2003;24:669–681. doi: 10.1002/jcc.10189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morris G.M., Huey R., Lindstrom W., Sanner M.F., Belew R.K., Goodsell D.S., Olson A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: automated docking with selective receptor flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009;30:2785–2791. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Drewt H.R., Wingtt R.M., Takanot T., Brokat C., Tanakat S., Itakuraii K., Dickersont R.E. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA. 1981;78:2179–2183. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jin Z., Du X., Xu Y., Deng Y., Liu M., Zhao Y., Zhang B., Li X., Zhang L., Peng C., Duan Y., Yu J., Wang L., Yang K., Liu F., Jiang R., Yang X., You T., Liu X., Yang X., Bai F., Liu H., Liu X., Guddat L.W., Xu W., Xiao G., Qin C., Shi Z., Jiang H., Rao Z., Yang H. Structure of Mpro from SARS-CoV-2 and discovery of its inhibitors. Nature. 2020;582:289–293. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2223-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Berman H.M., Westbrook J., Feng Z., Gilliland G., Bhat T.N., Weissig H., Shindyalov I.N., Bourne P.E. The protein data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:235–242. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. https://www.rcsb.org/pdb [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mangalam N.A., Sheeja S.R., Kurup M.R.P. Mn(II) complexes of some acylhydrazones with NNO donor sites: syntheses, a spectroscopic view on their coordination possibilities and crystal structures. Polyhedron. 2010;29:3318–3323. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2010.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krishnan S., Laly K., Kurup M.R.P. Synthesis and spectral investigations of Mn(II) complexes of pentadentate bis(thiosemicarbazones) Spectrochim. Acta A. 2010;75:585–588. doi: 10.1016/j.saa.2009.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Addison A.W., Rao N.T., Reedijk J., van Rijin J., Verschoor G.C. Synthesis, structure, and spectroscopic properties of copper(II) compounds containing nitrogen–sulphur donor ligands; the crystal and molecular structure of aqua[1,7-bis(N-methylbenzimidazol-2′-yl)-2,6-dithiaheptane]copper(II) perchlorate. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1984:1349–1356. doi: 10.1039/DT9840001349. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manoj E., Kurup M.R.P., E Suresh. Synthesis and spectral studies of bisthiocarbohydrazone and biscarbohydrazone of quinoline-2-carbaldehyde: crystal structure of bis(quinoline-2-aldehyde) thiocarbohydrazone. J. Chem. Crystallogr. 2008;38:157–161. doi: 10.1007/s10870-007-9267-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renjusha S., Kurup M.R.P. Structural and spectral studies on manganese(II) complexes of di-2-pyridyl ketone N(4)-methyl and N(4)-ethyl thiosemicarbazones. Polyhedron. 2008;27:3294–3298. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2008.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sreekanth A., Joseph M., Fun H.-K., Kurup M.R.P. Formation of manganese(II) complexes of substituted thiosemicarbazones derived from 2-benzoylpyridine: structural and spectroscopic studies. Polyhedron. 2006;25:1408–1414. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2005.10.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rapheal P.F., Manoj E., Kurup M.R.P. Syntheses and EPR spectral studies of manganese(II) complexes derived from pyridine-2-carbaldehyde based N(4)-substituted thiosemicarbazones: crystal structure of one complex. Polyhedron. 2007;26:5088–5094. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2007.07.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Singh N.K., Tripathi P., Bharty M.K., Srivastava A.K., Singh Sanjay, Butcher R.J. Ni(II) and Mn(II) complexes of NNS tridentate ligand N0-[(2-methoxyphenyl)carbonothioyl]pyridine-2-carbohydrazide (H2mcph): synthesis, spectral and structural characterization. Polyhedron. 2010;29:1939–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.poly.2010.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Turner M.J., Mckinnon J.J., Wolff S.K., Grimwood D.J., Spackman P.R., Jayatilaka D., Spackman M.A. Vol. 17. The University of Western Australia; 2017. https://hirshfeldsurface.net (Crystal Explorer). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spackman M.A., McKinnon J.J. Fingerprinting intermolecular interactions in molecular crystals. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2002;4:378–392. doi: 10.1039/B203191B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Spackman M.A., Jayatilaka D. Hirshfeld surface analysis. Cryst. Eng. Comm. 2009;11:19–32. doi: 10.1039/B818330A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Koopmans T. Über die zuordnung von wellenfunktionen und eigenwerten zu den einzelnen elektronen eines atoms. Physica. 1934;1:104–113. doi: 10.1016/S0031-8914(34)90011-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Murray J.S., Politzer P. The electrostatic potential: an overview. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011;1:153–322. doi: 10.1002/wcms.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sponer J., Hobza P. DNA base amino groups and their role in molecular interactions: ab initio and preliminary density functional theory calculations. Int. J. Quantum Chem. 1996;57:959–970. 10.1002/(SICI)1097-461X(1996)57:5<959::AID-QUA16>3.0.CO;2-S. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Politzer P., Murray J.S. The fundamental nature and role of the electrostatic potential in atoms and molecules. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2002;108:134–142. doi: 10.1007/s00214-002-0363-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray J.S., Politzer P. The electrostatic potential: an overview. WIREs Comput. Mol. Sci. 2011;1:153–322. doi: 10.1002/wcms.19. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mathews N.A., Kurup M.R.P. In vitro biomolecular interaction studies and cytotoxic activities of copper(II) and zinc(II) complexes bearing ONS donor thiosemicarbazones. Appl. Organometal. Chem. 2020;35:e6056. doi: 10.1002/aoc.6056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Singh I., Luxami V., Paul K. Synthesis, cytotoxicity, pharmacokinetic profile, binding with DNA and BSA of new imidazo[1,2-a]pyrazine-benzo[dmidazole-5-yl hybrids. Sci. Rep. 2020;10:6534. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63605-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.