Abstract

Harmful behavior against out-group members often rises during periods of economic hardship and health pandemics. Here, we test the widespread concern that the Covid-19 crisis may fuel hostility against people from other nations. Using a controlled money-burning task, we elicited hostile behavior among a nationally representative sample (n = 2,186) in the Czech Republic during the first wave of the pandemic. We provide evidence that exogenously elevating the salience of the Covid-19 crisis increases hostility against foreigners from the EU, USA and Asia. This behavioral response is similar across various demographic sub-groups. Further, we observe zero to small negative effects for both domestic out-groups and in-groups, suggesting that the salience of Covid-19 might negatively affect behavior not only towards foreigners but to other people more generally, though these findings are not conclusive. The results underscore the importance of not inflaming anti-foreigner sentiments and suggest the need to monitor impacts of the crisis on behavior in the social domain.

Keywords: COVID-19 pandemic, Hostility, Inter-group conflict, Experiment

1. Introduction

Intergroup conflicts are among the most pressing problems facing human society (Bowles, 2009; Fiske, 2002; Blattman and Miguel, 2010). Social scientists have long argued that difficult life conditions imposed upon individuals by external forces that threaten physical wellbeing and safety, such as economic and political upheavals or widespread disease, may create a fertile environment for xenophobia and out-group hostility. Evidence suggests that hostile behaviors and conflicts increase during periods of economic problems (Anderson et al., 2017; Grosfeld et al., 2020; Miguel et al., 2004). In the context of a crisis caused by a contagious disease, a particularly plausible mechanism is that people may form hostile attitudes to members of the groups that are associated with transmission of the disease (Murray and Schaller, 2016; O'Shea et al., 2020).

In light of this reasoning, the Covid-19 crisis, arguably the most severe health and economic shock since WWII (Baldwin and Weder di Mauro, 2020; New York Times, 2020), has created an unfortunate but suitable testing ground for exploring whether an important, naturally-occurring shock in the health and economic domains spills over to the social domain and magnifies inter-group animosity. Since Covid-19 originally surfaced in China and spreads across borders via interactions with people from other countries, contemporary commentators have suggested that it may foster prejudice against foreigners, particularly against people from Asia (CNN 2020). For example, Fernand de Varennes, the UN Special Rapporteur, warns that “COVID-19 is not just a health issue; it can also be a virus that exacerbates xenophobia, hate and exclusion.” (United Nations, 2020). Rigorously identifying the causal effects of Covid-19 on inter-national and domestic group divisions is fundamental for understanding the current and future social and political landscape. Such divisions may reduce support for global initiatives to tackle the pandemic, create barriers to re-establishing international trade, strengthen support for extreme right-wing political parties and increase the risk of conflicts.

Despite the importance of this issue, causal evidence on how fears associated with major health and economic shocks shape hostility against particular groups is lacking. This is not surprising because of several empirical challenges. First, hostility denotes aggressive harmful behavior motivated by positive utility from reduced welfare of certain individuals or groups, in contrast to harmful behavior motivated by personal material gain. Using naturally occurring data to uncover hostility, such as the prevalence of robbery or violence, is problematic because hardship often goes hand in hand with greater financial needs. Similarly, avoidance of out-group members or support for border closures can be a rational protective strategy. Thus, using these measures does not allow us to separate selfish motivations, based on a rational calculus of potential (material) benefits to ones’ self, from hostility. Second, a clean measurement requires an exogenous variation in the identity of the victim of the hostile behavior, in order to distinguish whether hardship fuels hostility towards particular groups, rather than towards people in general. The third challenge is identification of causal impacts. For understanding impacts of a shock that hits the whole country at a similar point in time, a key issue is finding a ceteris paribus variation in fears that is not correlated with time trends or unobserved confounders between individuals. Simply comparing individuals from localities with lower versus higher prevalence of disease during a health pandemic can be misleading. More pro-social and tolerant individuals can self-select into residing in localities that have a greater capacity to cope with the crisis. Moreover, individuals vary along many unobserved dimensions. For example, out-group hostility can be related to economic vulnerability and personal characteristics that affect people's ability to cope with economic or health shocks. Further, individuals who are more strongly inclined to socialize and hence are more likely to contract the virus may show greater tolerance of out-group members, possibly due to more frequent inter-group contact.

Here we provide evidence that a health pandemic accompanied by a severe economic shock increases prevalence of harmful behavior towards people living in other countries. Our evidence is based on a large-scale experiment implemented in midst of the Covid-19 crisis. We elicited hostile behavior among a nationally representative sample (n = 2,186) in the Czech Republic, a medium-sized country in Central Europe, while the pandemic was on the rise during its first wave, and the entire population lived under lockdown and border closure; see Supplementary Information (SI) for more details about the background.

Several features of our experimental design help us to overcome the empirical challenges described above. First, we directly elicit willingness to cause financial harm in a controlled money-allocation task. Subjects make anonymous, one-shot allocation decisions, in which they can decide to decrease a monetary reward for another person. Since reducing the reward does not result in pecuniary benefits for the decision-maker (or for anyone else), the choice reveals individual willingness to engage in hostile behavior. Second, we exogenously manipulate information about the identity of the recipient of the reward, in order to identify discrimination against foreigners. Third, we randomly assign the participants either to a treatment condition that increased the salience of Covid-related problems and fears, or to the control condition in which Covid-related challenges were not made salient. Random allocation ensures that participants in the treatment and control conditions are comparable in terms of observable and unobservable characteristics, helping to overcome selection issues and concerns about spurious correlation. Finally, an attractive feature of our empirical approach is that it can be easily employed on large representative samples in virtually any country with well-developed data collection infrastructure.

The paper is related to several literatures. In terms of measuring discrimination, we build on economic experiments designed to uncover biases in social preferences towards people with specific real-life group attributes (e.g., ethnicity), using incentivized allocation tasks (e.g., Bernhard et al., 2006; Fershtman and Gneezy 2001; Angerer et al., 2016; Berge et al., 2020).1 A noteworthy aspect of our work is the focus on multiple dimensions of group identity, since most of the earlier work studies only a single group attribute, for an exception see Kranton et al., (2020). The paper also adds to an emerging empirical literature which tests the role of environmental factors that may influence behavior to out-group members. The focus has been mostly on the effects of inter-group contacts (Rao, 2019; Mousa, 2020), social environment (Bauer et al., 2018), exposure to violent elections (Hjort, 2014) or violent inter-group conflict (Shayo and Zussman, 2011; Bauer et al., 2014).

Finally, the paper is related to work on “Behavioral immune system” in social psychology which has documented a correlation between greater exposure to (real or perceived) health threats and measures of group biases in explicit and implicit attitudes. For example, in US states with higher rates of infectious diseases, people exhibited greater racial prejudice (O'Shea et al., 2020). A representative survey from the US shows that citizens who felt more vulnerable to contracting Ebola displayed greater prejudice against immigrants in survey questions (Kim et al., 2016). Moving beyond correlations, showing a disease-related picture primes increased prejudice among subjects in the lab (Duncan and Schaller, 2009) and among a sample of M-Turk workers (O'Shea et al., 2020). We contribute by providing causal evidence of the impacts of a naturally occurring health pandemic on incentivized behavior among a representative sample.

2. Experimental design

2.1. Sample

We collected experimental data on a large, nationally-representative sample, using an approach inspired by Almas et al. (2020) and Falk et al. (2018) and took advantage of the online infrastructure of a leading data-collection agency in the Czech Republic (NMS Market Research and PAQ Research). The data were collected via the agency from a sample of 2,186 adults from March 30 to April 1, 2020. The sample is nationally representative in terms of age, sex, education, employment status before the Covid-19 pandemic, municipality size, and regional distribution, with a higher share of people living in large cities (Table S.1).

2.2. Measuring hostility

We developed a detailed experimental module, designed to uncover the shape of hostile preferences towards people with different group attributes. We administered a series of decisions in an allocation task that we label a Help-or-Harm task (HHT), which combines features of the well-established Dictator game and the Joy of Destruction game (Abbink and Sadrieh, 2009). The participants were asked to increase or decrease rewards to a set of people with different characteristics. The default allocation was CZK 100 (USD 4). Participants could allocate any amount between CZK 0 and CZK 200 (USD 0–8), using a slider located in the middle of the 0–200 scale (see Fig. S.1). The participants had to make an active choice - even if they decided to keep the reward at the default allocation, they had to click on the slider.

The advantage of implementing a salient reference point is that we can identify (i) changes in basic pro-social behavior and (ii) changes in the prevalence of hostile behavior. We denote behavior as pro-social when subjects choose to increase rewards above CZK 100, revealing that a participant cares positively about the recipient. Next, we refer to behavior as being hostile when subjects allocate less than CZK 100 to the recipient, since in order to do so they have to actively cause financial harm with no pecuniary benefit to themselves. Thus, such behavior cannot be explained by selfish motivations. In the analysis, we also consider the most extreme manifestations of such behavior, when subjects destroy all recipient's earnings, by allocating CZK 0.

There were no pecuniary costs for the decision-maker when choosing to engage in pro-social or hostile behavior (there were costs only in terms of effort). Note that although it is common in economic experiments to impose monetary costs on a decision-maker, the advantage of this design is that behavior should not be affected by pure income effects.2 This is useful because our goal is to isolate the psychological effects of economic and health shocks on preferences and decision heuristics from the mechanical income effects caused by the crisis. Because the increased salience of Covid-related problems in the treatment condition may also trigger individual financial concerns, introducing monetary costs might lead to a biased estimate of the psychological effects. Further, because it was costless to behave in a hostile way, the task identifies individuals with even a relatively weak preference to harm. It is possible that introducing monetary costs would result in a lower prevalence of hostile (or generous) behavior, as in experiments documenting that individuals respond to manipulations in the costs of giving (Andreoni and Miller, 2002).

Note that since the previous literature documents that a non-negligible fraction of people tend to act in hostile ways even towards in-group members (Bauer et al., 2018; Abbink and Sadrieh, 2009), hostile behavior towards out-group members does not necessarily reflect anti-outgroup bias. A clear measurement of such bias requires a comparison of the prevalence of hostility towards in-group members and towards out-group members.

2.3. Manipulating identity of a recipient

Each participant made seventeen decisions in the HHT, where each choice affected a recipient with different pre-specified characteristics. In order to measure nationality-based divisions and hostile behavior towards foreigners, the participants made five decisions on whether to increase or decrease money sent to a person living in each of the following regions: the Czech Republic, the EU, the USA, Asia, and Africa. We chose not to mention specific countries, such as Italy or China (the countries most saliently linked to the Covid-19 pandemic during our data collection period), in order to avoid inducing an experimenter demand effect. In the analysis, we focus on average behavior towards a foreigner (from the EU, the USA, Asia or Africa), and compare it to behavior towards a person from the Czech Republic. This choice aims to uncover “generalized” social behavior: no information was provided about the recipient except that the person lives in the respondent's home country (the Czech Republic).

Further, in order to measure domestic divisions and hostility to out-group members from one's own country, in the second set of decisions participants allocated money to people who all live in the Czech Republic but who either share a group attribute with them (in-group) or not (out-group). We focused on the following dimensions: region of residence (3 decisions), political orientation (2 decisions), ethnicity (3 decisions), and religion (4 decisions). In the analysis, we study average behavior towards domestic in-group members and towards domestic out-group members. Supplementary Information section 1.2 presents the specific wording of all decisions.

The choices were consequential—the subjects knew that thirty participants would be randomly selected and one of their choices would be implemented. The instructions made it clear that the decision makers could not also be receivers, in order to avoid the potential role of indirect reciprocity. After the experiment was completed, “a person living in your region” was selected as the payoff-relevant category of recipients. Thirty participants were randomly selected and their decisions for this category were implemented. The money was allocated to individuals from the database of the survey company who lived in corresponding regions and who did not participate in our experiment.

2.4. Manipulating salience of Covid-19

In order to exogenously manipulate the intensity of Covid-19-related concerns when subjects made decisions, we used a priming technique. Each participant was randomly allocated either to the COVID-19 (n = 1,142) or to the CONTROL condition (n = 1,044). In the COVID-19 condition, before making decisions in the Help-or-Harm tasks, the subjects answered a series of survey questions focusing on the coronavirus crisis, specifically on their preventive health behavior, social distancing, economic situation, and psychological wellbeing. The prime is designed to activate or intensify a complex set of thoughts and concerns that characterize people's lives during the coronavirus crisis. The median time the respondents spent answering this set of questions was 13 minutes. In the CONTROL condition, the participants made the decisions in the Help-or-Harm tasks at the beginning of the survey, and answered the coronavirus-related questions only later. This is a relatively unobtrusive way of introducing priming into an online experiment, since given that the data were collected during the first wave of the pandemic, it was natural to ask questions about this issue. Thus, we believe experimenter demand effects are unlikely to drive the observed differences in behavior across the COVID-19 and CONTROL conditions. Table S.1 shows that randomization was successful, since participants do not exhibit systematic differences across conditions in terms of observable characteristics. See Supplementary Information for more details about the sample, experimental design, definition of variables, and complete experimental protocol.

The priming technique allows us to measure purely psychological impacts of a greater intensity of Covid-related concerns on hostility. Priming is a well-established technique in social science (Bargh and Chartrand, 2000; Cohn and Maréchal, 2016) and has been successfully used to shed light on a range of other important issues (Cohn et al., 2014; Mani et al., 2013; Cohn et al., 2015). Also note that this technique identifies impacts of greater intensity of Covid-related thoughts, rather than the overall effects of Covid-19. Thus, to the extent that people in the CONTROL condition also have Covid-19 concerns very much at top of mind, this technique may underestimate the actual effects of the pandemic.

3. Results

3.1. Behavior towards foreigners

We find that, on average, participants allocate less money to foreigners (CZK 92) than to a person from their own country (CZK 133; Table 1 ; Somer's D test, P < 0.001). In order to test whether thinking about Covid-19 magnifies such nation-based discrimination by increasing hostility towards foreigners, we compare choices in the COVID-19 condition with choices in the CONTROL condition.

Table 1.

Mean allocations in the Help-or-Harm task by the identity of the recipient, across CONTROL and COVID-19 conditions.

| Mean allocations [95% confidence intervals] | Effect [z-statistic, p-value] | N | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Control | COVID-19 | |||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Panel A: Indexes | |||||

| Domestic (Czech) | 132.8 | 133.5 | 132.2 | -1 [p=0.390] | 2,186 |

| Foreign | 91.6 | 94.1 | 89.3 | -5 [p=0.013] | 8,743 (2,186 clusters) |

| (vs. Domestic) | -41 [p<0.001] | -39 [p<0.001] | -43 [p<0.001] | ||

| Domestic in-group | 125.1 | 127.3 | 123.0 | -4 [p=0.026] | 9,297 (2,186 clusters) |

| Domestic out-group | 95.0 | 96.5 | 93.5 | -3 [p=0.043] | 16,935 (2,186 clusters) |

| (vs. in-group) | -30 [p<0.001] | -31 [p<0.001] | -30 [p<0.001] | ||

| Panel B: Foreign | |||||

| Asian | 89.0 | 91.4 | 86.9 | -4 [p=0.044] | 2,186 |

| (vs. Domestic) | -44 [p<0.001] | -42 [p<0.001] | -45 [p<0.001] | ||

| European Union | 103.4 | 107.1 | 100.0 | -7 [p=0.003] | 2,186 |

| (vs. Domestic) | -29 [p<0.001] | -26 [p<0.001] | -32 [p<0.001] | ||

| US | 76.2 | 78.9 | 73.8 | -5 [p=0.013] | 2,186 |

| (vs. Domestic) | -57 [p<0.001] | -55 [p<0.001] | -58 [p<0.001] | ||

| African | 97.8 | 99.2 | 96.6 | -3 [p=0.296] | 2,185 |

| (vs. Domestic) | -35 [p<0.001] | -34 [p<0.001] | -36 [p<0.001] | ||

| Panel C: Domestic in-group/out-group | |||||

| Region in-group | 129.7 | 133.0 | 126.7 | -6 [p=0.015] | 2,783 (2,186 clusters) |

| Region out-group | 111.0 | 112.6 | 109.6 | -3 [p=0.053] | 3,775 (2,186 clusters) |

| (vs. in-group) | -19 [p<0.001] | -20 [p<0.001] | -17 [p<0.001] | ||

| Political in-group | 119.5 | 120.5 | 118.6 | -2 [p=0.207] | 2,186 |

| Political out-group | 92.3 | 94.3 | 90.5 | -4 [p=0.080] | 2,186 |

| (vs. in-group) | -27 [p<0.001] | -26 [p<0.001] | -28 [p<0.001] | ||

| Majority in-group | 123.4 | 125.6 | 121.4 | -4 [p=0.045] | 2,186 |

| Roma ethnicity out-group | 74.6 | 76.4 | 73.0 | -3 [p=0.058] | 2,186 |

| (vs. Majority in-group) | -49 [p<0.001] | -49 [p<0.001] | -48 [p<0.001] | ||

| Immigrant out-group | 94.6 | 95.5 | 93.8 | -2 [p=0.550] | 2,186 |

| (vs. Majority in-group) | -29 [p<0.001] | -30 [p<0.001] | -28 [p<0.001] | ||

| Religion in-group | 126.4 | 128.4 | 124.5 | -4 [p=0.142] | 2,142 (2,142 clusters) |

| Religion out-group | 93.5 | 95.1 | 92.0 | -3 [p=0.070] | 6,602 (2,186 clusters) |

| (vs. in-group) | -33 [p<0.001] | -33 [p<0.001] | -32 [p<0.001] | ||

Notes: Mean allocations in the Help-or-Harm task. "In-group" indicates that the respondent and the recipient share the group attribute. Differences reported in column 4 and on respective rows indicate a comparison group (e.g., vs. Domestic). We report p-values from the Wilcoxon rank-sum equality test whenever the number of observations is the same as the number of clusters, and Somer's D p-values clustered at individual level whenever we have more observations than clusters. The number of observations equals the number of individual decisions considered for each group of recipients (See Supplementary Information 1.2 for detailed descriptions of recipient group construction)

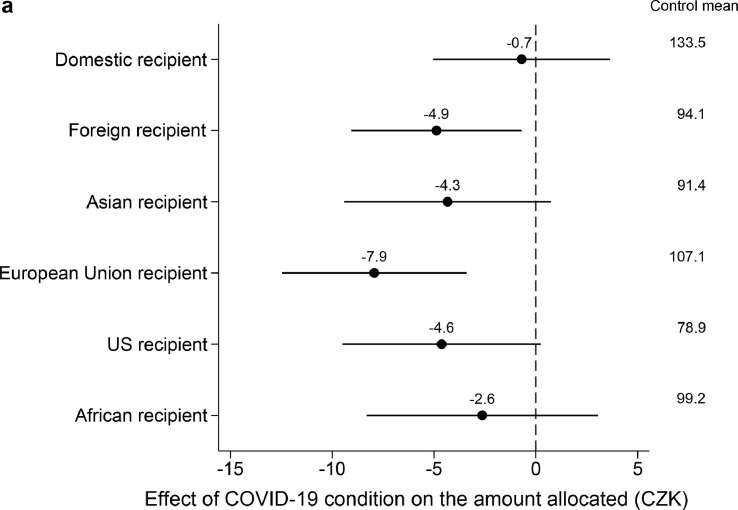

Thinking about Covid-19 has negative impacts on behavior towards foreigners (Fig. 1 a and Table 2 ). While in the CONTROL condition, participants on average allocated CZK 94 to foreigners, in the COVID-19 condition they allocated CZK 89 (OLS, P = 0.022). In contrast, the effect on behavior towards a domestic recipient is small in magnitude and not statistically significant (P = 0.753). In a regression analysis, we find a negative interaction effect between COVID-19 and an indicator variable for ‘foreigner’ (as compared to a domestic person), but it does not reach statistical significance at conventional levels (Table S.2, P = 0.140).

Fig. 1.

Effect of the COVID-19 condition on allocations in the Help-or-Harm task, by the identity of the recipients.

Notes: Coefficient plots. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals. In a, the dependent variable is the amount allocated. In b, the dependent variable is a binary variable indicating hostile behavior, equal to 1 if allocation is strictly lower than the default allocation (100 CZK). Both panels present estimated coefficients of the COVID-19 condition relative to the CONTROL condition (corresponding regression models including numbers of observations appear in Panel A of Table 2 and Panel A of Table S.4). Data for all 2,186 participants used.

Table 2.

Effect of the COVID-19 condition on the amount allocated in the Help-or-Harm task, by the identity of the recipient (domestic vs. foreign).

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity of the recipient: | Domestic | Foreign | Asian | European Union | US | African |

| Panel A: Baseline controls | ||||||

| COVID-19 | -0.698 | -4.882 | -4.332 | -7.933 | -4.625 | -2.628 |

| p-value | [0.753] | [0.022] | [0.094] | [0.001] | [0.063] | [0.364] |

| p-value (MHT; 2 hypotheses) | [0.045] | |||||

| p-value (MHT; 17 hypotheses) | [0.755] | [0.202] | [0.459] | [0.008] | [0.398] | [0.797] |

| Panel B: No controls | ||||||

| COVID-19 | -1.277 | -4.842 | -4.478 | -7.144 | -5.110 | -2.628 |

| p-value | [0.558] | [0.025] | [0.076] | [0.002] | [0.039] | [0.349] |

| p-value (MHT; 2 hypotheses) | [0.044] | |||||

| p-value (MHT; 17 hypotheses) | [0.559] | [0.178] | [0.369] | [0.025] | [0.249] | [0.775] |

| Panel C: Additional controls | ||||||

| COVID-19 | -0.284 | -5.473 | -4.969 | -8.094 | -5.440 | -3.386 |

| p-value | [0.898] | [0.011] | [0.059] | [0.001] | [0.031] | [0.247] |

| p-value (MHT; 2 hypotheses) | [0.024] | |||||

| p-value (MHT; 17 hypotheses) | [0.889] | [0.118] | [0.348] | [0.004] | [0.217] | [0.623] |

| Panel D: Probability weights | ||||||

| COVID-19 | -2.740 | -5.726 | -6.131 | -6.127 | -8.298 | -2.344 |

| p-value | [0.337] | [0.049] | [0.071] | [0.039] | [0.011] | [0.536] |

| CONTROL mean | 133.5 | 94.1 | 91.4 | 107.1 | 78.9 | 99.2 |

| # Clusters | 2,186 | |||||

| Observations | 2,186 | 8,743 | 2,186 | 2,186 | 2,186 | 2,185 |

Notes: OLS. P-values reported in square brackets (robust standard errors clustered at an individual level in column 2 where multiple observations are used per individual). The dependent variable is the amount allocated in the Help-or-Harm task. In Panel A, each regression controls for gender, age category (6 categories), household size, number of children, region (14 regions), town size (7 categories), education (4 categories), economic status (7 categories), household income (11 categories) and task order. Panel B reports results from regressions without control variables. In Panel C, each regression controls for baseline controls (as in Panel A) and further controls for the variables approximating economic situation, mental health, Covid-19 symptoms and activities during the lockdown (see Supplementary Information 1.4 for the list and definition of variables). Panel D reports results of weighted OLS regressions with no controls, using probability weights to correct for the oversampling of respondents from large municipalities. We also report multiple hypothesis testing corrected p-values using a method developed by Barsbai et al. (2020). See Supplementary Information 1.6 for details on the procedure and the hypotheses tested.

Next, we take a more granular approach and explore the effects on behavior towards foreigners from different parts of the world separately. We find a negative impact of COVID-19 on behavior towards people from the EU, the USA and Asia, but not from Africa (Fig. 1a and Table 2). The effect is largest for behavior towards people living in the EU—as compared to CONTROL, participants in COVID-19 allocated on average CZK 8 less to them (OLS, P = 0.001). The drop in COVID-19 as compared to CONTROL is CZK 5 for a person from the USA (P = 0.063) and CZK 4 for a person from Asia (P = 0.094). Although the negative effects on behavior towards people from the EU, the USA and Asia are statistically significant, the magnitude of the effects is not large. This is not surprising for two reasons. First, the prime employed in the COVID-19 condition was quite subtle (answering a set of survey questions related to Covid-19 before making choices in the Help-or-Harm task). Second, the priming technique we used allows us to identify a marginal effect of greater salience of Covid-19 related thoughts, rather than the overall effects of Covid-19.

As a baseline specification, we report unweighted results for all 2,186 participants (Fig. 1a and Panel A of Table 2, Fig. 3 and Panel A of Table S.3). Baseline models control for gender, age, household size, number of children, region, town size, education, economic status, household income and task order. Precise definitions of all variables are provided in the Supplementary Information. As a robustness check, we report results of 1) OLS models with no controls, 2) OLS models with additional controls for the variables approximating economic situation, mental health, Covid-19 symptoms and activities during the lockdown, and 3) weighted OLS regressions, using probability weights to correct for the oversampling of respondents from large municipalities (Panels B-D of Table 2 and Table S.3). The results are robust.

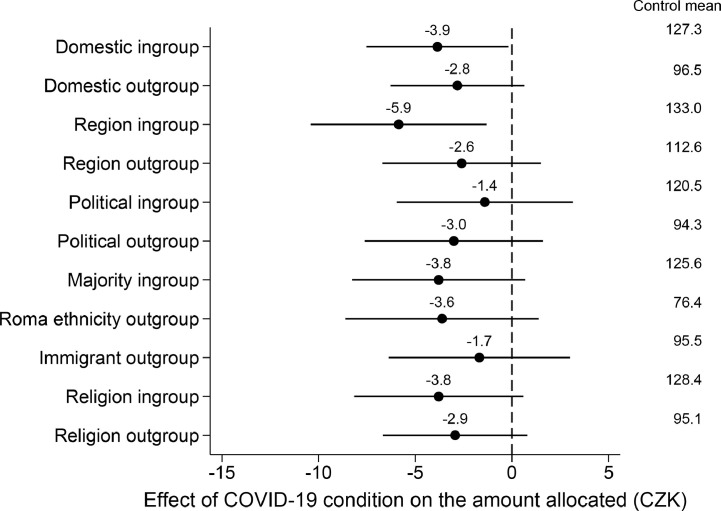

Fig. 3.

Effect of the COVID-19 condition on allocations in the Help-or-Harm task, by the group identity of domestic recipients.

Notes: Coefficient plots. Estimated coefficients of the COVID-19 condition relative to the CONTROL condition, the dependent variable is the amount allocated. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals. Corresponding regression models including numbers of observations appear in Panel A of Table S.3. Data for all 2,186 participants used.

Further, we show that the COVID-19 condition reduces money allocations to foreigners not only due to reduced pro-social behavior, but primarily due to increased prevalence of hostile behavior (Fig. 1b and Table S.4). We define an indicator variable equal to one if the participant actively destroyed the money allocated to the other person, i.e. reduced the reward to an amount below 100. The effect on prevalence of hostility is again largest for behavior towards a person living in the EU. In CONTROL, 20% decided to act in a hostile way towards a person from the EU, while in COVID-19 the prevalence of this behavior increased by 6 percentage points (OLS, P = 0.002). The difference is 5 percentage points (P = 0.035) and 4 percentage points (P = 0.049) for recipients living in the USA and Asia, respectively.

Interestingly, the observed increase in the prevalence of hostility towards these groups of foreigners is driven by the extreme manifestation of hostility, namely the prevalence of decisions to reduce the rewards to CZK 0 (Panel B of Table S.4). Again, the magnitude of these effects is largest for the recipient from the EU— while in the CONTROL condition, 6.2% of participants destroyed all the earning of a recipient from the EU, the proportion increases to 9.3% in the COVID-19 condition (OLS, P = 0.007). The prevalence of extreme hostility is very low towards domestic recipients, 2.3% in CONTROL and 2.5% in COVID-19 (P = 0.797). Our conclusion that the COVID-19 condition magnifies the extreme form of hostility towards foreigners is further supported by a difference-in-differences estimation comparing the foreign recipients to the domestic recipient (Panel A of Table S.5). We provide further support for these conclusions in Fig. S.2, which shows full distributions of choices across both COVID-19 and CONTROL conditions. As expected, we also observe that COVID-19 reduces the prevalence of basic pro-sociality, defined as a willingness to increase rewards above the default allocation (Panel C of Table S.4), but the effects are relatively small and mostly not significant statistically.

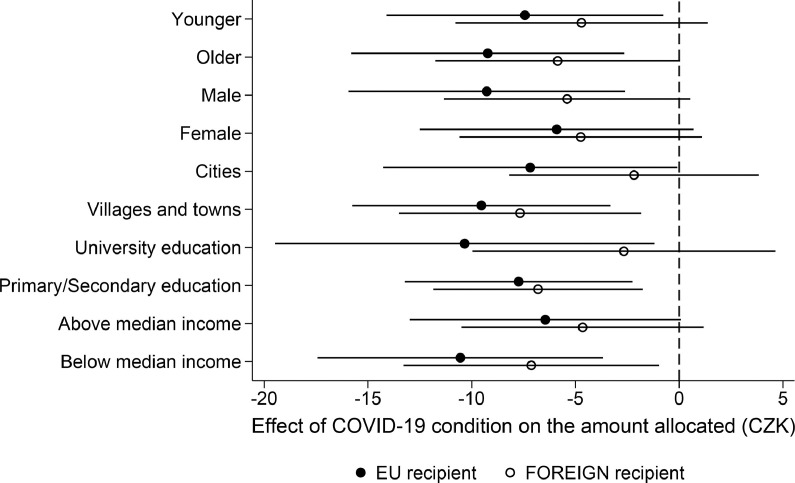

The size and diversity of our sample allows us to explore whether the observed effects of COVID-19 on hostility against foreigners is a broad response spanning across demographics, or behavior that characterizes certain demographic sub-groups of the population. Fig. 2 and Table S.6 displays the effect of the COVID-19 condition on the mean amount of money allocated (i) to all foreigners on average, and (ii) to recipients from the EU, for whom we observe the largest effects, across age groups, gender, education level, income level, and size of municipality. Overall, the results are similar across demographics.

Fig. 2.

Sub-group analysis of the effect of the COVID-19 condition on the amount allocated in the Help-or-Harm task, by the identity of the recipients.

Notes: Coefficient plots. Bars represent 95 percent confidence intervals. The dependent variable is the amount allocated. The Fig. presents estimated coefficients of the COVID-19 condition relative to the CONTROL condition (corresponding regression models including numbers of observations are in Table S.6). Age and net monthly household income are divided by the median (50 years and CZK 35,000). Municipalities are divided into cities with more than 100,000 inhabitants, and smaller villages and towns. Data for all 2,186 participants used.

3.2. Behavior towards domestic in-group and out-group members

Next, we explore how thinking about Covid-19 affects behavior towards domestic in-group and out-group members. To study this, we measure the average amount allocated to (i) domestic in-group members who share selected group attributes with the decision-maker (region of residence, ethnicity, political party preference, or religious beliefs) and (ii) domestic out-group members who do not share a given group attribute.

To start, we study mean allocations to each type of domestic in-group and out-group in the CONTROL condition (Table 1 and the right-hand side of Fig. 3 ). We observe an intuitive pattern. On average, the participants allocated larger rewards to in-group than to out-group recipients (CZK 127.3 vs. CZK 96.5, P < 0.001). This pattern holds for different domains, based on which in-group and out-group are defined. Recipients from a respondent's region, with similar political preferences, of the same ethnicity, or with the same religious affiliation as the respondent were allocated higher amounts than recipients with different characteristics. Consistent with previous research, which documented high levels of discrimination against the Roma ethnic minority in the Czech Republic (Bartoš et al., 2016), the difference is largest for ethnic divisions (a member of Roma ethnicity received, on average, CZK 76.4, while a member of the majority ethnic group received, on average, CZK 125.6, P < 0.001).

Interestingly, the random person living in the Czech Republic received a larger allocation not only compared to domestic out-group members (by CZK 37.0, P < 0.001), but also compared to domestic in-group members (by CZK 6.2, P < 0.001). This result indicates that participants consider the random person living in the Czech Republic a member of their in-group. At the same time, the result that a random Czech person received higher allocations than Czech recipients who also shared another group attribute with the respondent is somewhat surprising. Since we use behavior towards a random Czech person as a neutral benchmark category to assess whether the effects of Covid-19 salience on behavior are specific for foreigners, we conduct a series of robustness tests presented in Section 4, in which we use a set of alternative benchmark groups.

When analyzing the effects of the COVID-19 condition, we find an indication of negative effects on behavior towards both in-group and out-group members living in the same country as the respondent (Fig. 3 and Table S.3). However, most of the effects do not reach statistical significance and they are generally smaller in magnitude than the effects on behavior towards foreigners. Further, the effects of the COVID-19 condition on hostile behavior are not stronger for domestic out-groups than for domestic in-groups in a difference-in-difference estimation (Tables S.7 and S.8).

Together, the results about the effects on behavior towards domestic recipients need to be interpreted with caution. On one hand, we find virtually no effects on behavior towards a random person from the Czech Republic (Fig. 1). At the same time, the estimated coefficients on behavior towards specific groups within the Czech Republic are negative, although most of them are not statistically significant. While it remains an open question whether Covid-19 has null or mildly negative effects on behavior towards people from own country, in any case, our results do not support the optimistic view that the Covid-19 crisis may create stronger social bonds, as we do not see more favorable behavior towards in-group members in COVID-19 compared to CONTROL.

4. Additional results and robustness checks

In order to study in greater detail whether the COVID-19 condition increased hostility more towards foreigners than towards members of other groups, in Tables S.5 and S.9-S.10 we present the results of additional difference-in-difference estimations. This is useful for two reasons. First, because subjects allocated relatively large amounts to a random person living in the Czech Republic (as compared to what they allocated to more narrowly defined in-group members), we use an alternative benchmark group to proxy behavior towards a person living in the Czech Republic. Because the Czech Republic is a relatively homogenous country in terms of ethnicity, we use a person of the majority ethnicity living in the Czech Republic as such a proxy (Panel B). Second, we are interested in whether the effects on foreigners are larger than those on domestic out-group members. To study this, we use two benchmark groups: (i) allocations to members of any type of domestic out-group (Panel C), which should capture overall behavior towards a broad spectrum of out-group members, and (ii) a person living in a different region of the Czech Republic than the respondent (Panel D), which allows us to study differences in effects on behavior to recipients who all live in a different location than the respondent, in one case in a different country and in the other case in a different region within the same country.

The increase in hostility in the COVID-19 condition is stronger against foreigners from the European Union relative to most comparison groups, independently of whether we examine the amounts allocated in the HHT (Table S.9), the prevalence of hostile behavior (Table S.10), or the prevalence of extreme manifestations of hostility—reducing the reward to zero (Table S.5). As for foreigners overall, the estimated effects of the COVID-19 condition are always stronger than the effects on domestic comparison groups, but the differences do not reach statistical significance except when we focus on the prevalence of extreme hostility (Table S.5).

Based on this, we conclude that the results suggest that negative effects on behavior are greater for foreign recipients, as compared to other groups, but we acknowledge that this finding is not robust in all specifications.

Next, we address the potential concern of false discovery of significant effects in one of our seventeen outcomes of interest. In Table 2 and Table S.3 we present three types of p-values. The first is standard “per comparison” p-values. These are appropriate for researchers with an a priori interest in a specific outcome. For instance, researchers interested in the impact of Covid-19 on behavior specifically towards foreigners, or specifically towards people living in Asia, should focus on these p-values. In addition, the analysis also presents additional p-values that account for multiple hypothesis testing, using the method developed by Barsbai et al., (2020), since a potential concern might be that our results are susceptible to false discovery of significant results that arise simply by chance when testing the impacts on multiple outcome variables. Since the paper is motivated by concerns about Covid-19 fostering out-group hostility, we consider the two main outcome variables capturing behavior towards out-group members: (i) behavior towards foreigners and (ii) behavior towards domestic out-group members. Thus, researchers with a priori interest in behavior towards out-group members should focus on these p-values. The effect on foreigners remains statistically significant (P = 0.045). Finally, we take the most conservative approach, relevant for the question whether Covid-19 affects social behavior in general, towards any type of recipient. Consequently, we adjust for the seventeen hypotheses corresponding to all dependent variables for which we estimate the effects. Even under this approach, the effect on the recipients from the EU is statistically significant (P = 0.008). Nevertheless, the effects on behavior towards foreigners, people living in the USA and in Asia do not reach statistical significance after this correction.

The use of “within-subject” design, as compared to “between-subject” design, when eliciting behavior towards individuals with different group attributes has the advantage of providing a rich picture of individual discriminatory preferences, but can potentially affect the size of the estimated discrimination if subjects realized the purpose of the study. In principle, social desirability biases could reduce the estimated levels of discrimination if subjects choose to hide their true preferences, while experimenter demand effects may induce subjects towards greater differentiation in behavior towards individuals with different group attributes. We took several steps to address this issue. First, the seventeen HHT decisions were organized in six blocks, which were presented in a randomized order (96 different orderings), and we control for order effects in the regression analysis. Second, our main focus is on estimating the effects of greater Covid-19 salience on behavior. Thus, even if subjects were to some extent induced to differentiate their behavior towards individuals with different group attributes by the “within-subject” design, this is a concern only to the extent to which this confound interacts with the COVID-19 condition. Our results suggest this is unlikely. We show that the main effects hold when we focus on decisions made early in the experimental module, and thus mimic a “between-subject” design (Table S.11). Specifically, when we restrict the sample to choices made in the first block, the estimated negative effects of the COVID-19 condition on behavior towards foreigners are at least as strong as in the baseline specification where we use all decisions. We arrive at similar conclusions when we restrict the sample even further and consider only the very first decision made by each participant.3

Another potential concern is that thinking and answering questions in the COVID-19 condition may have caused fatigue and led to less attention to allocation decisions, and thus may have affected choices without activating Covid-related concerns and fears. This explanation is not supported by our data. Subjects in COVID-19 are neither more prone to stick to the default allocation, nor less likely to correctly answer attention check questions (Table S.13). Both of these patterns would be expected if subjects were less attentive. In fact, the effects of COVID-19 on behavior towards foreigners is caused by reduced likelihood of sticking to the default allocation, and an increased tendency to actively reduce recipients’ income (Fig. S.2). Subjects’ response time is somewhat lower in COVID-19, but all results are robust to controlling for response time (Table S.14).

5. Discussion and open questions

The evidence presented in this paper illuminates that Covid-19 can cause damage in the social domain, but it should be seen as only an initial step. Below we discuss several limitations and directions for future research.

First, although the effects of the prime on behavior towards various groups of foreigners are statistically significant, the magnitude of these effects is not large. This is not surprising given that we identify marginal effects of greater salience of Covid-19 concerns, and not their overall effects. While the priming technique is a useful tool to uncover qualitative effects, it is less informative about the magnitude of the impact of real-life experiences.

The second open question concerns the underlying mechanisms. Overall, the results are consistent with the idea that people form more negative attitudes towards people with group attributes associated with the transmission of the disease. First, at the time of the data collection, infection rates in the Czech Republic were relatively low, as compared to most of the EU countries, such as Italy, Germany, and Spain. The first reported cases of Covid-19 in the Czech Republic got infected in Italy. The Czech government quickly responded, by closing borders, in addition to other measures. These aspects may have fostered the perception of the coronavirus pandemic as an external threat, spreading mainly from other EU countries. Further, at the time of the data collection, Africa had been much less associated with the virus compared to EU, the US and Asia, thanks to relatively low infection rates, helping to explain why we observe negligible effects on behavior towards people from Africa. In this context, it may seem surprising that we do not see greater effect on behavior towards individuals from Asia, as compared to behavior towards people from the EU or the US. While China was mentioned regularly by Czech public officials and the media, it mainly concerned positive remarks about medical supplies delivery.4

Further, the Covid-19 crisis has entered people's lives in complex ways. It has created fears about people's own health, and that of friends and family members. To many, it has imposed economic hardships and uncertainty about future material well-being. It has also forced people to isolate themselves socially. The prime used in this paper may have activated all these concerns, and we cannot separate their roles in triggering the observed increase in hostility towards foreigners. A fruitful avenue for future research would be to try to more sharply disentangle these aspects, perhaps by designing a set of Covid-related primes, each aiming to activate a different dimension of concerns.

Further, the mechanisms above consider direct effects of the pandemic on individual preferences. Another possibility is that the observed increase in anti-foreigner sentiments may have been created by the behavior of politicians who may have incentives to blame foreigners for spreading the virus, in order to redirect attention from their own internal problems fighting the pandemic. Specifically, the increase in hostility towards recipients from the European Union could potentially be driven by Czech politicians blaming the EU for slow responses at the beginning of the pandemic. Eurobarometer 93 reports worsening attitudes towards the EU between Fall 2019 and Summer 2020—the share of Czech people trusting the EU dropped by 4 p.p. (Eurobarometer, 2020), while the share of Czechs with a negative view of the EU increased by 5 p.p., although other surveys provide more mixed evidence5 . We provide the following test of this explanation. If these indirect effects were driving the increase in anti-foreigner sentiments, we would expect the effects to be more pronounced among people who were more exposed to social media or media in general. The results do not provide support for this explanation, since we do not observe such heterogeneous effects (Table S.15). Nevertheless, we cannot fully rule out this mechanism and future work could study this further by, for example, comparing the effects of Covid-19 in countries in which politicians did and did not incite anti-foreigner sentiments or did and did not try to place blame on the European Union.

Finally, this paper focused on the immediate effects of the first coronavirus wave, but it will be important to study how the attitudes towards out-groups develop during the later stages of the pandemic and post-pandemic recovery. Also, the evidence comes from a single country and more research is needed to explore how generalizable the effects are across settings.

6. Conclusions

This paper provides initial evidence documenting how concerns triggered by a global health pandemic, Covid-19, shape hostility towards people with different group attributes. The main result is that thinking about Covid-19 increases anti-foreigner sentiments, making people more prone to financially harm people from the EU, the USA and Asia. We show that this is a relatively general response, present across various demographic groups.

Some of our results also indicate that the salience of Covid-19 negatively affects behavior towards other people more generally, since we find zero to small negative effects for domestic out-groups as well as in-groups. Thus, the negative effects may not be limited to behavior towards foreigners, but this evidence should be viewed only as suggestive.

Our results underscore the importance of making sure political and other opinion-leaders avoid associating or blaming foreigners and other countries for the crisis. Placing blame as a political strategy can either create or tap into elevated anti-foreigner sentiments, and consequently increase the risk that the health and economic crises will become compounded by unravelling of international collaborations.

Footnotes

We thank PAQ Research and NMS Market Research for implementing the data collection. Bauer and Chytilová thank ERC-CZ/AV-B (ERC300851901) for support and funding of the data collection. Bartoš thanks the German Science Foundation for their support through CRC TRR 190. The research was approved by the Commission for Ethics in Research of the Faculty of Social Sciences of Charles University. Participation was voluntary and all respondents provided consent with participation in the survey. The datasets and do-file replication files are available in the Harvard Dataverse repository (doi: 10.7910/DVN/XD8OOL). Declarations of interest: none.

Note that the dataset which we used in the earlier version of this paper (version: May 2020) contained a coding error, which impacted some of the estimates (please see the Supplementary Information for more details). This version presents the results after the correction. The main finding of the paper – that greater salience of the Covid-19 crisis increases hostility to foreigners – still holds.

In-group favoritism and out-group discrimination have also been measured using a minimal-group experimental paradigm, by creating artificial group boundaries in the laboratory (based on, for example, having T-shirts of the same color or sharing preferences for art). The most prominent examples are Tajfel (1981), Chen and Li (2009), and Charness, Rigotti, and Rustichini (2007).

Earlier research has used costless redistribution tasks to measure fairness preferences and found that similar fairness views are observed for monetarily uninterested individuals (“spectators”) and for individuals whose payoffs were affected by own decisions (Cappelen et al. 2013). Such spectator designs have been successfully employed in recent large-scale experiments, see, for example (Cappelen et al. 2020; Almas, Cappelen, and Tungodden 2020).

In addition, Table S.12 presents the results from the first block of choices for domestic in-groups and out-groups, where we find a negative effect of the COVID-19 condition on behavior towards domestic in-groups (-5.9 CZK, p=0.047) and smaller and insignificant effect towards domestic out-groups (-3.2 CZK, p=0.232), in line with the patterns observed with full data.

We performed a text analysis of all governmental Covid-19 related press conferences held before the end of our data collection, and the twitter feeds of the governmental officials most involved in the management of the Covid-19 crisis in the Czech Republic. We did not find a single case of labeling Covid-19 as “Chinese virus” or similar. A sole critical tweet pointed to the dependency of the EU on Chinese medical production.

The survey agency CVVM did not find many changes in attitudes towards the EU between April 2019 and July 2020 (CVVM 2020). The survey agency STEM finds a drop in satisfaction with the EU membership between Fall 2019 and May 2020, but the opinions are volatile, with May 2020 being very similar to Summer 2019 (STEM 2020).

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2021.103818.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Abbink Klaus, Sadrieh Abdolkarim. The Pleasure of Being Nasty. Economics Letters. 2009;105(3):306–308. [Google Scholar]

- Almas Ingvild, Cappelen Alexander, Tungodden Bertil. Cutthroat capitalism versus cuddly socialism : are americans more meritocratic and efficiency-seeking than scandinavians? J. Polit. Econ. 2020;128(5):1753–1788. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson Robert Warren, Johnson Noel D., Koyama Mark. Jewish Persecutions and Weather Shocks: 1100–1800. Economic Journal. 2017;127(602):924–958. [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni James, Miller John. Giving According to GARP: An Experimental Test of the Consistency of Preferences for Altruism. Econometrica. 2002;70(2):737–753. [Google Scholar]

- Angerer Silvia, Glätzle-Rützler Daniela, Lergetporer Philipp, Sutter Matthias. Cooperation and Discrimination within and across Language Borders: Evidence from Children in a Bilingual City. European Economic Review. 2016;90:254–264. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin Robert, Mauro Beatrice Weder di. CEPR Press; 2020. Mitigating the COVID Economic Crisis: Act Fast and Do Whatever It Takes. VoxEU.org eBook. [Google Scholar]

- Bargh John A, Chartrand Tanya L. Handbook of Research Methods in Social and Personality Psy- Chology. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2000. The mind in the middle: a practical guide to prim- ing and automaticity research; pp. 253–285. edited by Harry T. Reis and Charles M. Judd. [Google Scholar]

- Barsbai T, Licuanan V, Steinmayr A, Tiongson E, Yang D. NBER Working Paper No. 27346. 2020. Information and the Acquisition of Social Network Connections. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoš V., Bauer M., Chytilová J., Matějka F. Attention discrimination: theory and field experiments with monitoring information acquisition. Am. Econ. Rev. 2016;106(6):1437–1475. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer Michal, Cahlíková Jana, Chytilová Julie, Želinský Tomáš. Social contagion of ethnic hostility. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2018;115(19):4881–4886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1720317115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer Michal, Cassar Alessandra, Chytilová Julie, Henrich Joseph. War's enduring effects on the development of egalitarian motivations and in-group biases. Psychol. Sci. 2014;25(1):47–57. doi: 10.1177/0956797613493444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge Lars Ivar Oppedal, Bjorvatn Kjetil, Galle Simon, Miguel Edward, Posner Daniel, Tungodden Bertil, Zhang Kelly. Ethnically biased? Experimental evidence from Kenya. J. European Economic Association. 2020;18(1):134–164. [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard Helen, Fischbacher Urs, Fehr Ernst. Parochial Altruism in Humans. Nature. 2006;442(7105):912–915. doi: 10.1038/nature04981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blattman C., Miguel E. Civil War. J. Econ. Lit. 2010;48(1):3–57. [Google Scholar]

- Bowles Samuel. Did Warfare among Ancestral Hunter-Gatherers Affect the Evolution of Human Social Behaviors? Science. 2009;324(5932):1293–1298. doi: 10.1126/science.1168112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen Alexander W., Konow James, Sorensen Erik, Tungodden Bertil. Just Luck: An Experimental Study of Risk-Taking and Fairness. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013;103(4):1398–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Cappelen Alexander W., List John A., Samek Anya, Tungodden Bertil. The Effect of Early-Childhood Education on Social Preferences. J. Polit. Econ. 2020;128(7):2739–2758. doi: 10.1086/706858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charness Gary, Rigotti Luca, Rustichini Aldo. Individual Behavior and Group Membership. Am. Econ. Rev. 2007;97(4):1340–1352. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y., Li S.X. Group Identity and Social Preferences. Am. Econ. Rev. 2009;99(1):431–457. [Google Scholar]

- CNN. 2020. “A New Virus Stirs up Ancient Hatred.” Https://Edition.Cnn.Com/2020/01/30/Opinions/Wuhan-Coronavirus-Is-Fueling-Racism-Xenophobia-Yang/Index.Html.

- Cohn Alain, Engelmann Jan, Fehr Ernst, Maréchal Michel André. Evidence for countercyclical risk aversion: an experiment with financial professionals. Am. Econ. Rev. 2015;105(2):860–885. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn Alain, Fehr Ernst, Maréchal Michel André. Business culture and dishonesty in the banking industry. Nature. 2014;516(4):86–89. doi: 10.1038/nature13977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohn Alain, Maréchal Michel André. Priming in economics. Curr. Opinion Psychology. 2016;12:17–21. [Google Scholar]

- CVVM. 2020. “Důvěra v Evropské a Mezinárodní Instituce – Červenec 2020.” Https://Cvvm.Soc.Cas.Cz/Media/Com_form2content/Documents/C2/A5265/F9/Pm200831.Pdf.

- Duncan Lesley A, Schaller Mark. Prejudicial attitudes toward older adults may be exaggerated when people feel vulnerable to infectious disease : evidence and implications. Anal. Soc. Issues Public Policy. 2009;9(1):97–115. [Google Scholar]

- Eurobarometer. 2020. “Eurobarometer 93, Factsheet in English for the Czech Republic.” Https://Ec.Europa.Eu/Commfrontoffice/Publicopinion/Index.Cfm/Survey/Getsurveydetail/Instruments/Standard/Surveyky/2262.

- Falk Armin, Becker Anke, Dohmen Thomas, Enke Benjamin, Huffman David, Sunde Uwe. Global Evidence on Economic Preferences. Q. J. Econ. 2018;133(4):1645–1692. [Google Scholar]

- Fershtman Chaim, Gneezy Uri. Discrimination in a segmented society: an experimental approach. Q. J. Econ. 2001;116(1):351–377. [Google Scholar]

- Fiske Susan T. What we know now about bias and inter-group conflict, the problem of the century. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 2002;11(4):123–128. [Google Scholar]

- Grosfeld Irena, Sakalli Seyhun Orcan, Zhuravskaya Ekaterina. Middleman minorities and ethnic violence: anti-jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire. Rev. Economic Studies. 2020;87(1):289–342. [Google Scholar]

- Hjort Jonas. Ethnic Divisions and Production in Firms. Q. J. Econ. 2014;129(4):1899–1946. [Google Scholar]

- Kim Heejung S, Sherman David K, Updegraff John A. Fear of Ebola : The Influence of Collectivism on Xenophobic Threat Responses. Psychol. Sci. 2016;27(7):935–944. doi: 10.1177/0956797616642596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kranton Rachel, Pease Matthew, Sanders Seth, Huettel Scott. Deconstructing Bias in Social Preferences Reveals Groupy and Not-Groupy Behavior. PNAS. 2020;117(35):21185–21193. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1918952117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mani Anandi, Mullainathan Sendhil, Shafir Eldar, Zhao Jiaying. Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function. Science. 2013;341(6149):976–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1238041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel Edward, Shanker Satyanath, Sergenti Ernest. Economic Shocks and Civil Conflict : An Instrumental Variables Approach. J. Polit. Econ. 2004;112(4):725–755. [Google Scholar]

- Mousa Salma. Building Social Cohesion between Christians and Muslims through Soccer in Post-ISIS Iraq. Science. 2020;369(6505):866–870. doi: 10.1126/science.abb3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray Damian R., Schaller Mark. The Behavioral Immune System. Adv. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 2016;53:75–129. [Google Scholar]

- New York Times. 2020. “Why the Global Recession Could Last a Long Time.” Https://Www.Nytimes.Com/2020/04/01/Business/Economy/Coronavirus-Recession.Html.

- O'Shea Brian A, Watson Derrick G, Brown Gordon D A, Fincher Corey L. Infectious disease prevalence, not race exposure, predicts both implicit and explicit racial prejudice across the United States. Social Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2020;11(3):345–355. [Google Scholar]

- Rao Gautam. Familiarity does not breed contempt : generosity, discrimination, and diversity in delhi schools. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019;109(3):774–809. [Google Scholar]

- Shayo Moses, Zussman Asaf. Judicial ingroup bias in the shadow of terrorism. Q. J. Econ. 2011;126(3):1447–1484. [Google Scholar]

- STEM. 2020. “Klíčové Slovo: Evropská Unie.” Https://Www.Stem.Cz/Tag/Evropska-Unie/.

- Tajfel Henry. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1981. Human Groups and Social Categories: Studies in Social Psychology. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. 2020. “COVID-19 Stoking Xenophobia, Hate and Exclusion, Minority Rights Expert Warns.” Https://News.Un.Org/En/Story/2020/03/1060602.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.