Abstract

Background

Obesity is associated with left atrial (LA) remodeling (ie, dilatation and dysfunction) which is an independent determinant of future cardiovascular events. We aimed to assess whether LA remodeling is present in obesity even in individuals without established cardiovascular disease and whether it can be improved by intentional weight loss.

Methods and Results

Forty‐five individuals with severe obesity without established cardiovascular disease (age, 45±11 years; body mass index; 39.1±6.7 kg/m2; excess body weight, 51±18 kg) underwent cardiac magnetic resonance for quantification of LA and left ventricular size and function before and at a median of 373 days following either a low glycemic index diet (n=28) or bariatric surgery (n=17). Results were compared with those obtained in 27 normal‐weight controls with similar age and sex. At baseline, individuals with obesity displayed reduced LA reservoir function (a marker of atrial distensibility), and a higher mass and LA maximum volume (all P<0.05 controls) but normal LA emptying fraction. On average, weight loss led to a significant reduction of LA maximum volume and left ventricular mass (both P<0.01); however, significant improvement of the LA reservoir function was only observed in those at the upper tertile of weight loss (≥47% excess body weight loss). Following weight loss, we found an average residual increase in left ventricular mass compared with controls but no residual significant differences in LA maximum volume and strain function (all P>0.05).

Conclusions

Obesity is linked to subtle LA myopathy in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease. Only larger volumes of weight loss can completely reverse the LA myopathic phenotype.

Keywords: left atrial myopathy, obesity, reservoir strain, weight loss

Subject Categories: Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), Obesity

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- %EBW

excess body weight percentage

- LAEF

left atrial emptying fraction

- LAVmax

left atrial maximum volume

Clinical Perspective.

What Is New?

A subtle left atrial dysfunction can be found in individuals affected by obesity even in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease and risk factors.

Such left atrial myopathic phenotype can be completely reverted with large volumes of weight loss.

What Are the Clinical Implications?

When managing individuals with obesity, efforts to obtain large volumes of weight loss may be considered to reverse the early subtle left atrial dysfunction even in the absence of overt cardiovascular disease and risk factors.

Obesity is independently associated with increased risk of heart failure, 1 , 2 atrial fibrillation (AF), 3 and thromboembolic events. 1 , 4 , 5 , 6

Typically, obesity is associated with cardiac remodeling characterized by left ventricular (LV) hypertrophy. 7 Recent evidence suggests that obesity appears to be linked to left atrial (LA) myopathic changes (in terms of LA dilatation 8 and dysfunction 9 ). This is relevant as convincing evidence now shows that LA dilatation and dysfunction (eg, lower LA reservoir function, a marker of reduced LA compliance) are associated with worse cardiovascular outcomes. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13

To date, it is unclear whether LA myopathy in obesity may be a downstream phenotype reflecting the higher burden of cardiovascular risk factors caused by obesity (eg, type 2 diabetes and hypertension) 1 or whether there are early LA myopathic changes (ie, onsetting before the cardiovascular complications of obesity occur) likely reflecting the systemic inflammation 14 and hemodynamic strain 15 associated with this condition.

Although Mendelian randomization studies 16 have confirmed that an elevated body mass index (BMI) is causally linked to AF (sometimes regarded as an extreme form of atrial myopathy), it is unclear whether a weight loss intervention (through either a dietary intervention or bariatric surgery) would be sufficient to reverse the LA myopathic phenotype.

Here, we used advanced cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) imaging to assess (a) whether obesity is associated with LA dilatation and dysfunction in individuals without established cardiovascular disease, and (b) whether any degree of weight loss improves the LA dilatation and function in these subjects.

METHODS

Reasonable requests to access the data set may be sent to the corresponding author.

Study Population

We prospectively recruited individuals with elevated BMI (≥30 kg/m2) scheduled for elective bariatric surgery or willing to undertake a low energy diet without established cardiovascular disease nor cardiovascular risk factors. Individuals with obesity scheduled for bariatric surgery underwent Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass or a laparoscopic or surgical adjustable gastric band, whereas others adopted a low glycemic index diet supervised by a clinician.

Lean controls (BMI <27 kg/m2) without cardiovascular risk factors were selected from other research magnetic resonance imaging studies within our department to match the study cohort with obesity for age and sex.

Formulas

Height and weight were measured at the time of the scan. Body surface area was calculated using the Mosteller formula (body surface area [m2]=√[height×weight]/3600). BMI (kg/m2) was calculated dividing weight by height. 2 Different levels of weight loss were calculated based on the tertiles of the distribution of the excess body weight percentage (%EBW) lost at the follow‐up CMR scan compared with baseline. Percentage excess weight loss was calculated according to the formula: percent excess weight loss=(weight before−weight after [kg]/excess body weight before) where excess body weight=total body weight–ideal body weight.

MRI Protocol

All participants underwent CMR scanning before and after weight loss intervention (median, 373 [72–452] days). The study flowchart is reported as Figure S1.

Control participants underwent the CMR study protocol once. All participants underwent CMR imaging at the Oxford Centre for Clinical Magnetic Resonance Research (OCMR), University of Oxford. Scans were obtained using Siemens 1.5T (Sonata) or 3T (Trio, Verio, and MAGNETOM Prisma) MRI scanners depending on availability. The research protocols had local ethical approval in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. All patients signed an informed consent form.

MRI Postprocessing Analysis

Cardiac

Steady‐state free precession MRI cine in the 2‐chamber and 4‐chamber orientation were used to assess LA maximum volume (LAVmax), LA emptying fraction (LAEF), LV ejection fraction (LVEF), end‐diastolic and end‐systolic volume (LVEDV and LV end‐systolic volume, respectively), and to allow derivation of LV and LA longitudinal strain parameters by feature tracking, as described previously. 17 , 18 Briefly, LV global longitudinal strain was calculated as the peak global LV longitudinal strain 19 ; LA maximal and minimal volumes were determined with the biplane area‐length method 17 and used to calculate LAEF. LA strain values were used to assess atrial function in the 3 phases of the atrial cycle (LA reservoir, LA conduit, LA booster strain) as previously described. 18

Two masked observers appropriately trained and not involved in scanning procedures contoured the cine images and performed postprocessing analysis using the CVI42 software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., version 5.10.1). Reproducibility of LA reservoir strain is reported in Data S1.

Fat

A single breath‐hold, 5‐slice, water‐suppressed T1‐weighted turbo spin echo sequence centered around L5 was acquired. 20 Images were manually contoured for visceral fat volume included in the 5‐slice volume by masked operators using CVI42 software (Circle Cardiovascular Imaging Inc., version 5.10.1).

Statistical Analysis

To assess whether obesity is associated with LA dilatation and dysfunction in individuals without established cardiovascular disease, we compared baseline MRI parameters between individuals with obesity and controls. Further, to assess whether any degree of weight loss improves the LA dilatation and function in these subjects, we used correlations between changes in MRI parameters and %EBW loss as well as paired analysis (baseline versus follow‐up MRI parameters) within each level of weight loss (ie, each tertile of the distribution of the %EBW loss).

Continuous data are shown as mean±SD if normally distributed or median (Q1‐Q3) if non‐normally distributed. The unpaired Student t‐test was used to compare normally distributed data with homogeneous variances between individuals with obesity and controls whereas the Welch test was used to compare normal data with unequal variance. Categorical data were compared by using the χ2 test, or the Fisher exact method if cell size <5. Paired data (baseline versus follow‐up) were compared with paired t‐test.

Paired analysis of changes in cardiac parameters were performed within different levels of weight loss (ie, within each tertile of the distribution of the %EBW lost at the follow‐up CMR scan compared with baseline).

Differences in cardiac parameters changes across different levels of weight loss (Table S1) were assessed using 1‐way ANOVA with adjustment for pairwise multiple comparisons (via Bonferroni correction).

Pearson correlation coefficient was calculated for analysis of linear correlations. The relationship between LA reservoir change and %EBV loss has been analyzed with the “curve fit” function in SPSS using a quadratic model.

To assess whether the effect of weight loss on LA reservoir function was independent of changes in blood pressure measurements, a linear regression analysis was performed using change in LA reservoir strain (between follow‐up and baseline scan) as a dependent variable and %EWB and change in systolic blood pressure as covariates of interest. In addition, to assess whether the effect of weight loss was mediated by reduction of blood pressure, a mediated regression analysis using Preacher and Hayes method 21 (Process 4.1 macro).

All tests were 2‐tailed, and values of P<0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Graphs were produced using GraphPad Prism version 6.01 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA) and IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Power calculations were performed using G*Power version 3.1.9.2.

Sample Size Determination

Assuming that in the study population LAVmax has an SD of 12 mL (based on pilot data), we calculated that recruitment of at least 44 individuals with obesity and 22 lean controls would provide >90% power (2‐tailed alpha=0.05) to detect a 10‐mL difference in LAVmax between groups.

We calculated that recruitment of a total of 45 subjects with obesity (n=15 within each tertile of weight loss) would give 90% power (2‐tailed alpha=0.05) to detect paired 10‐mL changes in LAVmax after the interventions.

RESULTS

A total of 45 individuals with severe obesity (BMI, 39.1±6.7 kg/m2; 51±18 kg of excess body weight [EBW]; age, 45±11 years; 67% women) were recruited. Of these, 28 (62%) underwent a low glycemic diet and 17 (38%) had bariatric surgery as follows: Roux‐en‐Y gastric bypass (n=9), laparoscopic adjustable gastric band (n=5), laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (n=3). A total of 27 normal‐weight controls (BMI, 22.3±2.4 kg/m2) were recruited to match for age and sex (age, 41±12 years; 75% women; P=0.147 and P=0.424, respectively, for comparisons between participants with obesity and controls).

Features of Obesity‐Related Cardiomyopathy

Baseline characteristics of all subjects are summarized in Table 1. Compared with normal‐weight controls, individuals with obesity displayed significantly higher LV end‐diastolic volume, LV ejection fraction, and LV mass (P=0.015, P=0.008, P<0.001, respectively), significantly reduced global longitudinal strain (P<0.001) but not clinically relevant difference in LV ejection fraction albeit statistical significance (P=0.008), hence implying only a subtle LV dysfunction. Despite displaying blood pressure readings within the normal range, participants with obesity had significantly higher systolic and diastolic blood pressure compared with controls (P=0.001 and P<0.001, respectively).

Table 1.

Baseline Clinical Characteristics

| Obesity | Controls | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. total | 45 | 27 | |

| Age, y | 45±11 | 41±12 | 0.147 |

| Women, % | 30 (67) | 21 (75) | 0.424 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 39.2±6.8 | 22.3±2.4 | <0.001* |

| Weight, kg | 110±19 | 63±8 | <0.001* |

| Height, cm | 167±9 | 168±8 | 0.717 |

| Heart rate, bpm | 68±23 | 65±9 | 0.448 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 127±17 | 114±7 | 0.001* |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 79±11 | 67±7 | <0.001* |

| LV EDV, mL | 158±27 | 141±31 | 0.015* |

| LV EDVi, mL/m2 | 71±12 | 82±13 | 0.001* |

| LV EF, % | 67±6 | 63±5 | 0.008* |

| LV mass, g | 151±31 | 106±22 | <0.001* |

| LV massi, g/m2 | 67±11 | 61±9 | 0.039* |

| LV GLS, % | −15.6±2.7 | −18.8±2.8 | <0.001* |

| LAVmax, mL | 89±16 | 74±20 | 0.001* |

| LAVmaxi, mL/m2 | 40±7 | 43±11 | 0.091 |

| LA EF, % | 61±6 | 58±7 | 0.075 |

| LA reservoir, % | 36.3±8.4 | 41.3±12.9 | 0.048* |

| LA conduit, % | 24.8±6.8 | 28.0±10.5 | 0.116 |

| LA booster, % | 12.3±3.9 | 13.3±4.9 | 0.351 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD or n (%). BMI indicates body mass index; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction or emptying fraction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; i, indexed. LA, left atrium; LAVmax, left atrial maximum volume; and LV, left ventricle.

Significant P values (<0.05).

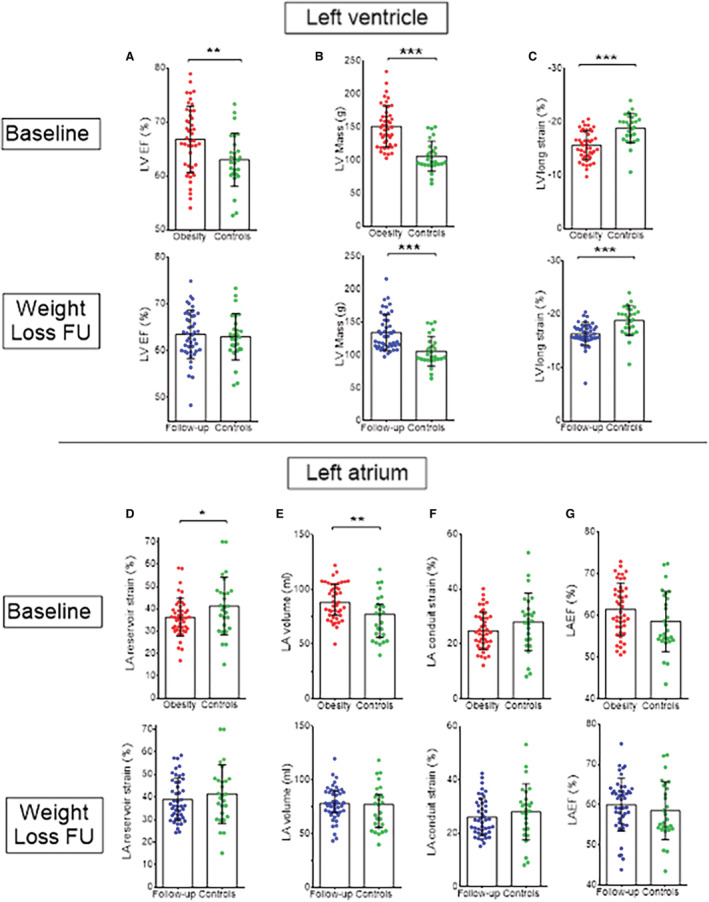

Obesity was also associated with a higher LAVmax (P=0.001) and a significantly reduced LA reservoir function (P=0.048) with a non‐significant trend towards reduced conduit function, as compared with controls (Figure 1). Notably, individuals with obesity had normal global LA function (by LAEF) and normal LA booster function when compared with controls.

Figure 1. Relationship between obesity and cardiac parameters.

Baseline (in red) and follow‐up (in blue) measurements of left ventricular (A through C) and atrial (D through G) parameters assessed by cardiac magnetic resonance are reported in individuals with obesity. EF indicates ejection fraction or emptying fraction; FU, follow‐up; LA, left atrium; LVlong, left ventricle longitudinal; and LV, left ventricle. These measurements were compared with lean controls (in green), and significant differences are reported as * or ** corresponding to P<0.05 or P<0.01, respectively.

Effects of Weight Loss on Cardiac Parameters

Overall, the weight loss interventions led to a median weight loss of 15.2 kg (corresponding to median %EBW of 36.2%). As expected, bariatric surgery was associated with a higher weight loss compared with low glycemic diet (%EBW 50.6±18.2 versus 30.4±15.5, respectively; P<0.001). For the whole group, weight loss led to a significant reduction of LAVmax and LV mass (both paired P<0.01). On average, there was no significant change in LAEF or LA strain phasic parameters, although there appears to be an average trend towards improvement of LA reservoir function (from 36.3±8.4% to 39.0±9.4%, paired P=0.071).

Analysis of the effect of different levels of weight loss (ie, tertiles of weight loss in terms of percentage of excess body weight lost, Figure 2, Table 2, Table S1) on cardiac parameters revealed that any degree of weight loss led to a reduction in LV mass (paired P<0.001 for upper/middle tertiles and paired P=0.015 for lower tertile, Table 2) and LAVmax (P=0.033/0.015 within both middle/lower tertiles and nonsignificant trend within the upper tertile with P=0.135, Table 2). However, only within the upper tertile of weight loss (corresponding to >47% loss of EBW) was a significant improvement in LA reservoir and conduit function observed (paired P=0.036 and P=0.024, respectively). By contrast, middle and lower tertiles of weight loss had no significant effect on LA function parameters (all paired P>0.05, Table 2). There was no material effect of weight loss on the LAEF across tertiles of weight loss (P>0.999 for upper, P=0.132 for middle, P=0.762 for lower, Table 2). Furthermore, the increase in LA reservoir strain within the upper tertile of weight loss was significantly larger than the change recorded within the middle and lower tertiles (P=0.045 and P=0.030, respectively; Table S1, Figure 2).

Figure 2. Effects of levels of intentional weight loss on cardiac parameters.

Levels of weight loss were calculated as tertiles of excess body weight percentage loss with a color‐coded legend also reported. Changes in left ventricular mass (A), left atrial maximum volume (B), and left atrial reservoir strain (C) stratified for different levels of weight loss (ie, tertiles of excess body weight percentage loss) are also shown as well as the correlation between excess body weight percentage loss and cardiac parameters. Comparisons for changes in cardiac parameters between tertiles of weight loss are reported in Table S1. Left ventricular mass changes linearly with changes in excess body weight percentage loss (A, ) while left atrial reservoir strain changes quadratically (C, ). The overall population of 45 participants is stratified per tertile of weight loss with 15 individuals within each tertile. LA indicates left atrium; and LV, left ventricle.

Table 2.

Effects of Weight Loss on Cardiac Parameters Within Each Tertile of Weight Loss

| Upper (>47% EBW) | Middle (27%–46% EBW) | Lower (<26% EBW) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Total=45 Tertiles of weight loss | Baseline | Follow‐up | P value | Baseline | Follow‐up | P value | Baseline | Follow‐up | P value |

| Weight, kg | 111±18 | 78±10 | <0.001* | 107±19 | 90±12 | <0.001* | 112±22 | 102±18 | <0.001* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 41.3±6.7 | 28.6±3.7 | <0.001* | 37.8±7.0 | 31.5±4.5 | <0.001* | 38.4 ± 6.7 | 35.8±5.5 | <0.001* |

| Heart rate, bpm | 62±16 | 59±11 | >0.999 | 65±17 | 62±18 | >0.999 | 77±30 | 65±15 | 0.522 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 127±15 | 115±10 | <0.001* | 128±19 | 118±12 | 0.213 | 125±18 | 124±11 | >0.999 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 79±12 | 70±6 | 0.072 | 81±11 | 74±9 | 0.024* | 79±12 | 82±9 | >0.999 |

| LV EDV, mL | 154±22 | 156±22 | >0.999 | 160±34 | 154±26 | 0.870 | 162±26 | 162±30 | >0.999 |

| LV EF, % | 66±7 | 66±5 | >0.999 | 66±6 | 64±5 | 0.114 | 68±6 | 61±5 | 0.015* |

| LV mass, g | 155±20 | 129±21 | <0.001* | 151±32 | 141±32 | <0.001* | 147±40 | 133±28 | 0.015* |

| LV GLS, % | −14.9±2.3 | −16.7±1.3 | 0.102 | −15.8±3.0 | −16.8±2.2 | 0.438 | −16.2±2.7 | −15.6±2.6 | >0.999 |

| LA volume max, mL | 88 ± 17 | 77±18 | 0.135 | 89±19 | 78±16 | 0.033* | 91±14 | 79±13 | 0.015* |

| LA EF, % | 60±6 | 62±8 | >0.999 | 63±7 | 59±6 | 0.132 | 61±7 | 59±6 | 0.762 |

| LA reservoir, % | 33.7±8.7 | 42.1±10.9 | 0.036* | 38.7±8.7 | 38.3±10.3 | >0.999 | 36.3±7.6 | 36.4±5.9 | >0.999 |

| LA conduit, % | 23.0±6.7 | 27.9±7.5 | 0.024* | 27.9±7.1 | 25.4±7.2 | 0.345 | 23.4±5.8 | 25.0±6.0 | 0.969 |

| LA booster, % | 10.7±4.0 | 14.3±6.0 | 0.150 | 13.6±3.2 | 12.7±4.5 | >0.999 | 12.9±4.1 | 13.2±4.2 | >0.999 |

Values are expressed as mean±SD. %EBW indicates excess body weight percentage; BMI, body mass index; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction or emptying fraction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; n=15 within each tertile of weight loss.

Significant P values (<0.05) after Bonferroni correction for multiple pairwise comparisons.

As expected, within the upper tertile of weight loss we recorded a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure alongside improvement in LA reservoir strain (P<0.001 and P=0.036). A linear regression analysis shows that the association between change in EBW and LA reservoir strain remains significant even after adjustment for change in systolic blood pressure (P=0.037). In addition, on mediation regression analysis, the relationship between change in BMI and change in LA reservoir strain was not mediated through change in systolic blood pressure.

While LV mass decreased linearly with weight loss (Pearson coefficient=−0.34, P=0.021, Figure 2), we found a quadratic relationship between weight loss and LA reservoir changes (R2=0.181, P=0.014) with the majority of the improvement observed with weight loss targets of >40% EBW (Figure 2). No significant relationship was found for LAVmax change (P=0.440) where a similar reduction in LAVmax was observed for any degree of weight loss (Figure 2).

Finally, we observed a moderate correlation between weight loss and loss of visceral body fat (Pearson coefficient=0.57, P<0.001). Exploratory analysis to investigate the interplay between loss of visceral fat and cardiac parameters is reported in Figure 3. Notably, we found a significant moderate linear correlation between visceral fat loss and LA reservoir function (Pearson coefficient=0.40, P=0.017), as well as between visceral fat loss and LV mass (Pearson coefficient=−0.51, P=0.002) but, again, no significant correlation for LAVmax change.

Figure 3. Correlation between loss of visceral fat and cardiac parameters.

Correlation between loss of visceral fat and left ventricular mass, left atrial volume, and left atrial reservoir strain. There is also a color‐coded stratification according to tertiles of excess body weight percentage loss. LA indicates left atrium; and LV, left ventricle.

Among the 15 patients with >47% %EBW loss, there were significantly more patients who underwent bariatric surgery compared with those who had a diet program (10 [67%] versus 5 [33%], P=0.005). However, we observed no significant difference in LA function change between participants with obesity who underwent bariatric surgery versus those on a diet (LA reservoir strain rise of 3.9±13% versus 2±7%, respectively [P=0.546], and LAEF reduction of −1.8±8% versus 1.2±6%, respectively [P=0.788]).

Comparison After Weight Loss Against Controls

After weight loss intervention, body weight and BMI remained higher on average when compared with controls (both P<0.001, Table 3). Despite beneficial effects on cardiac parameters following weight loss, we found a residual LV dysfunction (by global longitudinal strain) associated with higher LV mass absolute measures (albeit not significantly different when considering indexed values). By contrast, all LA parameters were no longer meaningfully different from those of normal weight controls (all P>0.05, Figure 1 and Table 3).

Table 3.

Differences in Cardiac Parameters Between Individuals With Obesity After Weight Loss Versus Controls

| After weight loss | Controls | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. total | 45 | 27 | … |

| Weight, kg | 90±17 | 63±8 | <0.001* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 32.0±5.4 | 22.3±2.4 | <0.001* |

| LV EDV, mL | 157±25 | 141±31 | 0.017* |

| LV EDV, mL/m2 | 77±12 | 82±13 | 0.153 |

| LV EF, % | 63±5 | 63±5 | 0.694 |

| LV mass, g | 134±27 | 106±22 | <0.001* |

| LV mass, g/m2 | 66±11 | 61±9 | 0.103 |

| LV GLS, % | −16.4±2.1 | −18.8±2.8 | <0.001* |

| LA volume maximum, mL | 78±16 | 74±20 | 0.380 |

| LA volume maximum indexed, mL/m2 | 38±8 | 43±11 | 0.032* |

| LA EF, % | 60±7 | 58±7 | 0.370 |

| LA reservoir, % | 39.0±9.4 | 41.3±12.9 | 0.322 |

| LA conduit, % | 26.1±6.9 | 28.0±10.5 | 0.351 |

| LA booster, % | 13.5±4.8 | 13.3±4.9 | 0.887 |

BMI indicates body mass index; EDV, end‐diastolic volume; EF, ejection fraction or emptying fraction; GLS, global longitudinal strain; LA, left atrium; LAVmax, left atrial maximum volume; and LV, left ventricle.

Significant P values (<0.05).

Exploratory analyses showed that individuals who achieved the highest tertile of weight loss displayed normalization of all LA parameters (all P>0.05 versus controls, Table S2) whereas the LV parameters (albeit improved) showed residual subtle LV dysfunction by global longitudinal strain (P=0.001 versus controls, Table S2).

DISCUSSION

We evaluated the effect of obesity on cardiac parameters in individuals with obesity but without overt cardiovascular disease or risk factors. Alongside LV hypertrophy and longitudinal dysfunction, we found signs of LA myopathy, including not only LA dilatation but also a subtle LA dysfunction characterized by impaired LA reservoir function (ie, LA compliance and distensibility during LV systole) rather than LA global emptying fraction or active contractile function (ie, "atrial kick"). We therefore demonstrated for the first time that LA myopathy is already present in individuals with obesity before overt cardiovascular disease or cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes develop. This is relevant because LA dysfunction (and in particular LA reservoir dysfunction by magnetic resonance imaging feature tracking) is an important prognostic factor implicated in the pathophysiology leading to incident cardiovascular events 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22 including HF admission, premature death, and stroke, although these findings were recorded in different populations. 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 22

Our study also investigated whether early LA myopathy is reversible after intentional weight loss. We found that only substantial weight loss was associated with normalization of LA function. Further, from our preliminary analysis using visceral fat volumes, it appears that LA function improves linearly with the reduction in visceral fat. Notably, we also recorded an overall reduction of blood pressure with weight loss despite it being within normal range to start with (no participant with obesity had a diagnosis of hypertension). Together, these findings suggest that effective weight loss options achieving substantial reductions in visceral fat mass should be prioritized in individuals with obesity, even in the apparent absence of comorbidity or additional cardiovascular risk factors.

Obesity and LA Myopathy

Although obesity also increases the risk of diabetes, hypertension, atherosclerosis, and AF, 3 the excess risk of stroke and heart failure in individuals with obesity does not seem to be fully explained by these conditions. 4 , 23 , 24 , 25 , 26 Indeed, obesity is associated with increased cardiovascular risk even after adjusting for traditional risk factors 4 and is an independent risk factor for heart failure with preserved EF 23 (which in turn increases the risk of systemic thromboembolic events 27 ). The mechanisms behind the link between obesity and cardiovascular risk are incompletely understood.

Our study shows that LA myopathic changes are present in obesity in the absence of comorbidity or a history of cardiovascular events, suggesting that increased cardiovascular risk observed with increased BMI may be explained, at least in part, by the presence of an LA myopathy. 1

A previous study using 2‐dimensional speckle‐tracking echocardiography demonstrated that in patients with diabetes, obesity appears to exacerbate deterioration of atrial function. 28 However, no studies to date have assessed whether obesity on its own is sufficient to determine LA dysfunction. Our results imply not only that obesity by itself (ie, without concomitant cardiovascular risk factors) is associated with LA dilatation and dysfunction, but also that it is possible to revert these adverse myopathic changes by means of effective weight loss regimens. Previous studies have demonstrated that, in patients with AF (an extreme form of atrial myopathy) and elevated BMI, weight loss combined with intensive risk factor management can reduce AF symptoms and bring about beneficial cardiac remodeling including reduction in LV mass and LA size. 29 Our results are in keeping with these observations and add that the link between weight loss and LA reverse remodeling seems apparent even in individuals with obesity but without cardiovascular risk factors. This implies that weight loss not only acts via improving cardiovascular risk factors profile (eg, reducing blood pressure and improving diabetes control) but also via other direct mechanisms (eg, improving inflammatory profile 29 and epicardial fat 30 ).

Intriguingly, our study shows that the LA myopathic phenotype observed in obesity without cardiovascular risk factors seem to differ from the overt LA myopathy in patients with comorbidities. 31 In fact, our results show that obesity without cardiovascular risk factors is linked to LA dilatation and reduced LA reservoir but not with global LA emptying function (ie, LAEF), a feature which is usually present in more advanced atrial myopathy together with fibrotic degeneration. 31 In fact, it appears that a reduction in LA reservoir function (specifically during the cardiac phase when the mitral valve is closed) may be the first apparent abnormality without an impact on the overall LAEF despite being a volumetric surrogate of LA reservoir function.

Overall, the fact that LA reservoir function, a marker of LA distensibility, can be improved (or even normalized with large volumes of weight loss) implies that the pathological decrease in LA distensibility is likely functional (possibly because of abnormal calcium handling 32 or inflammatory/metabolic profile 31 or other factors) rather than because of fibrotic (or irreversible) changes, at least at this early pathophysiological state. Although LA reservoir function can be improved, our results suggest that only large targets of weight loss (ie, >40% EBW) are associated with such changes while smaller targets seem not sufficient to translate into a tangible improvement. By contrast, in participants with obesity we recorded no material effect of weight loss on the LAEF across tertiles of weight loss.

Obesity and LV Myopathy

Building on previous findings showing that obesity is linked to worse LV function (by echo‐derived global longitudinal strain, s' velocity, and e' velocity) even after adjusting for cardiovascular risk factors, 33 our study confirms the hypothesis that a subtle LV dysfunction is present in obesity before onset of cardiovascular complications. Irrespective of method (ie, surgery versus diet), our data confirm the evidence that weight loss leads to a regression of cardiac hypertrophy. 20 , 34

Limitations

In principle, using different field strengths (1.5T versus 3T MRI) may generate bias in the analysis from cine data and thus be regarded as a limitation. However, previous data demonstrated that the reproducibility of cine imaging using CMR is independent of field strength, 35 , 36 and all paired scans (ie, before and after intervention) were performed on the same magnetic resonance system.

Controls were selected from other research MRI studies by an investigator not involved in the MRI postprocessing analyses. However, the comparisons with the control group are limited by a potential selection bias.

Cardiac indices normalized to body surface area can be misleading relative to the underlying raw values as a result of distortion by widely used body surface area formulae. 37

Although relevant from a pathophysiological perspective, 38 caution should be used before considering LA reservoir by feature tracking a biomarker ready to be adopted in the clinical practice. A standardization of the technique (including across vendors) is much needed to bring this biomarker forward towards clinical applicability.

CONCLUSIONS

We found evidence of early LA myopathy in individuals with obesity without overt cardiovascular disease. Weight loss can completely revert the early LA myopathic phenotype in such individuals. However, this can be achieved only with larger weight loss targets.

Sources of Funding

The study was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre and by the British Heart Foundation. O. Rider is funded by the British Heart Foundation. J. Rayner, Dr Spartera, and R. Wijesurendra acknowledge support from the Oxford British Heart Foundation Centre of Research Excellence. Dr Spartera acknowledges funding from the National Institute for Health Research Oxford Biomedical Research Centre, the National Health Service, and support from a competitive scholarship for young cardiologists awarded by the Italian Society of Cardiology funded by MSD ITALIA – MERCK SHARP & DOHME CORPORATION.

Disclosures

R. Wijesurendra has received honoraria and/or travel assistance from Biosense Webster, Bayer, Boston Scientific, and Abbott. The remaining authors have no disclosures to report.

Supporting information

Data S1

Tables S1–S2

Figure S1

O. Rider and M. Spartera are co‐senior authors.

For Sources of Funding and Disclosures, see page 10.

References

- 1. Packer M. HFpEF is the substrate for stroke in obesity and diabetes independent of atrial fibrillation. JACC Heart Fail. 2020;8:35–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jchf.2019.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Eaton CB, Pettinger M, Rossouw J, Martin LW, Foraker R, Quddus A, Liu S, Wampler NS, Hank Wu WC, Manson JE, et al. Risk factors for incident hospitalized heart failure with preserved versus reduced ejection fraction in a multiracial cohort of postmenopausal women. Circ Heart Fail. 2016;9:e002883. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kernan WN, Inzucchi SE, Sawan C, Macko RF, Furie KL. Obesity: a stubbornly obvious target for stroke prevention. Stroke. 2013;44:278–286. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.639922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kurth T, Gaziano JM, Berger K, Kase CS, Rexrode KM, Cook NR, Buring JE, Manson JE. Body mass index and the risk of stroke in men. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2557–2562. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.22.2557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Strazzullo P, D'Elia L, Cairella G, Garbagnati F, Cappuccio FP, Scalfi L. Excess body weight and incidence of stroke: meta‐analysis of prospective studies with 2 million participants. Stroke. 2010;41:e418–e426. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.109.576967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bodenant M, Kuulasmaa K, Wagner A, Kee F, Palmieri L, Ferrario MM, Montaye M, Amouyel P, Dallongeville J; MORGAM Project . Measures of abdominal adiposity and the risk of stroke: the MOnica risk, genetics, archiving and monograph (MORGAM) study. Stroke. 2011;42:2872–2877. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.614099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Alpert MA. Obesity cardiomyopathy: pathophysiology and evolution of the clinical syndrome. Am J Med Sci. 2001;321:225–236. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200104000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stritzke J, Markus MR, Duderstadt S, Lieb W, Luchner A, Doring A, Keil U, Hense HW, Schunkert H, Investigators MK. The aging process of the heart: obesity is the main risk factor for left atrial enlargement during aging the MONICA/KORA (monitoring of trends and determinations in cardiovascular disease/cooperative research in the region of Augsburg) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1982–1989. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.07.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chirinos JA, Sardana M, Satija V, Gillebert TC, De Buyzere ML, Chahwala J, De Bacquer D, Segers P, Rietzschel ER; Asklepios investigators . Effect of obesity on left atrial strain in persons aged 35‐55 years (the Asklepios study). Am J Cardiol. 2019;123:854–861. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2018.11.035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Habibi M, Chahal H, Opdahl A, Gjesdal O, Helle‐Valle TM, Heckbert SR, McClelland R, Wu C, Shea S, Hundley G, et al. Association of CMR‐measured LA function with heart failure development: results from the MESA study. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;7:570–579. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.01.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carluccio E, Biagioli P, Mengoni A, Francesca Cerasa M, Lauciello R, Zuchi C, Bardelli G, Alunni G, Coiro S, Gronda EG, et al. Left atrial reservoir function and outcome in heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:e007696. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.118.007696 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Leung M, van Rosendael PJ, Abou R, Ajmone Marsan N, Leung DY, Delgado V, Bax JJ. Left atrial function to identify patients with atrial fibrillation at high risk of stroke: new insights from a large registry. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:1416–1425. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weerts J, Barandiaran Aizpurua A, Henkens M, Lyon A, van Mourik MJW, van Gemert M, Raafs A, Sanders‐van Wijk S, Bayes‐Genis A, Heymans SRB, et al. The prognostic impact of mechanical atrial dysfunction and atrial fibrillation in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2021;23:74–84. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeab222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Shen MJ, Arora R, Jalife J. Atrial myopathy. JACC Basic Transl Sci. 2019;4:640–654. doi: 10.1016/j.jacbts.2019.05.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Rider OJ, Francis JM, Ali MK, Byrne J, Clarke K, Neubauer S, Petersen SE. Determinants of left ventricular mass in obesity; a cardiovascular magnetic resonance study. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson. 2009;11:9. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-11-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chatterjee NA, Giulianini F, Geelhoed B, Lunetta KL, Misialek JR, Niemeijer MN, Rienstra M, Rose LM, Smith AV, Arking DE et al. Genetic obesity and the risk of atrial fibrillation: causal estimates from mendelian randomization. Circulation. 2017;135:741–754, doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wijesurendra RS, Liu A, Eichhorn C, Ariga R, Levelt E, Clarke WT, Rodgers CT, Karamitsos TD, Bashir Y, Ginks M, et al. Lone atrial fibrillation is associated with impaired left ventricular energetics that persists despite successful catheter ablation. Circulation. 2016;134:1068–1081. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.022931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Truong VT, Palmer C, Wolking S, Sheets B, Young M, Ngo TNM, Taylor M, Nagueh SF, Zareba KM, Raman S, et al. Normal left atrial strain and strain rate using cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking in healthy volunteers. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2019;21:446–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Biering‐Sorensen T, Biering‐Sorensen SR, Olsen FJ, Sengelov M, Jorgensen PG, Mogelvang R, Shah AM, Jensen JS. Global longitudinal strain by echocardiography predicts long‐term risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in a low‐risk general population: the Copenhagen City heart study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10:e005521. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005521 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rider OJ, Francis JM, Ali MK, Petersen SE, Robinson M, Robson MD, Byrne JP, Clarke K, Neubauer S. Beneficial cardiovascular effects of bariatric surgical and dietary weight loss in obesity. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:718–726. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav Res Methods. 2008;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chirinos JA, Sardana M, Ansari B, Satija V, Kuriakose D, Edelstein I, Oldland G, Miller R, Gaddam S, Lee J, et al. Left atrial phasic function by cardiac magnetic resonance feature tracking is a strong predictor of incident cardiovascular events. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2018;11:e007512. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.117.007512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gong FF, Jelinek MV, Castro JM, Coller JM, McGrady M, Boffa U, Shiel L, Liew D, Wolfe R, Stewart S, et al. Risk factors for incident heart failure with preserved or reduced ejection fraction, and valvular heart failure, in a community‐based cohort. Open Heart. 2018;5:e000782. doi: 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Baena‐Diez JM, Byram AO, Grau M, Gomez‐Fernandez C, Vidal‐Solsona M, Ledesma‐Ulloa G, Gonzalez‐Casafont I, Vasquez‐Lazo J, Subirana I, Schroder H. Obesity is an independent risk factor for heart failure: Zona Franca cohort study. Clin Cardiol. 2010;33:760–764. doi: 10.1002/clc.20837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Abbott RD, Behrens GR, Sharp DS, Rodriguez BL, Burchfiel CM, Ross GW, Yano K, Curb JD. Body mass index and thromboembolic stroke in nonsmoking men in older middle age. The Honolulu Heart Program. Stroke. 1994;25:2370–2376. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.25.12.2370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chinali M, Joffe SW, Aurigemma GP, Makam R, Meyer TE, Goldberg RJ. Risk factors and comorbidities in a community‐wide sample of patients hospitalized with acute systolic or diastolic heart failure: the Worcester heart failure study. Coron Artery Dis. 2010;21:137–143. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0b013e328334eb46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Patel RB, Alenezi F, Sun JL, Alhanti B, Vaduganathan M, Oh JK, Redfield MM, Butler J, Hernandez AF, Velazquez EJ, et al. Biomarker profile of left atrial myopathy in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: insights from the RELAX trial. J Card Fail. 2020;26:270–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2019.12.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Mohseni‐Badalabadi R, Mehrabi‐Pari S, Hosseinsabet A. Evaluation of the left atrial function by two‐dimensional speckle‐tracking echocardiography in diabetic patients with obesity. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2020;36:643–652. doi: 10.1007/s10554-020-01768-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Abed HS, Wittert GA, Leong DP, Shirazi MG, Bahrami B, Middeldorp ME, Lorimer MF, Lau DH, Antic NA, Brooks AG, et al. Effect of weight reduction and cardiometabolic risk factor management on symptom burden and severity in patients with atrial fibrillation: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310:2050–2060. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.280521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Abed HS, Nelson AJ, Richardson JD, Worthley SG, Vincent A, Wittert GA, Leong DP. Impact of weight reduction on pericardial adipose tissue and cardiac structure in patients with atrial fibrillation. Am Heart J. 2015;169:655–662.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2015.02.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Packer M. Characterization, pathogenesis, and clinical implications of inflammation‐related atrial myopathy as an important cause of atrial fibrillation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9:e015343. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.015343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Denham NC, Pearman CM, Caldwell JL, Madders GWP, Eisner DA, Trafford AW, Dibb KM. Calcium in the pathophysiology of atrial fibrillation and heart failure. Front Physiol. 2018;9:1380. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Selvaraj S, Martinez EE, Aguilar FG, Kim KY, Peng J, Sha J, Irvin MR, Lewis CE, Hunt SC, Arnett DK, et al. Association of central adiposity with adverse cardiac mechanics: findings from the hypertension genetic epidemiology network study. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mahajan R, Stokes M, Elliott A, Munawar DA, Khokhar KB, Thiyagarajah A, Hendriks J, Linz D, Gallagher C, Kaye D, et al. Complex interaction of obesity, intentional weight loss and heart failure: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Heart. 2020;106:58–68. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2019-314770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Schuster A, Morton G, Hussain ST, Jogiya R, Kutty S, Asrress KN, Makowski MR, Bigalke B, Perera D, Beerbaum P, et al. The intra‐observer reproducibility of cardiovascular magnetic resonance myocardial feature tracking strain assessment is independent of field strength. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1036–1038. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wintersperger BJ, Bauner K, Reeder SB, Friedrich D, Dietrich O, Sprung KC, Picciolo M, Nikolaou K, Reiser MF, Schoenberg SO. Cardiac steady‐state free precession CINE magnetic resonance imaging at 3.0 tesla: impact of parallel imaging acceleration on volumetric accuracy and signal parameters. Invest Radiol. 2006;41:141–147. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000192419.08733.37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Adler AC, Nathanson BH, Raghunathan K, McGee WT. Effects of body surface area‐indexed calculations in the morbidly obese: a mathematical analysis. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2013;27:1140–1144. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2013.06.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Malaescu GG, Mirea O, Capota R, Petrescu AM, Duchenne J, Voigt JU. Left atrial strain determinants during the cardiac phases. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2022;15:381–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2021.09.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data S1

Tables S1–S2

Figure S1