PURPOSE:

Traditional oncology care models have not effectively identified and managed at-risk patients to prevent acute care. A next step is to harness advances in technology to enable patients to report symptoms any time, enabling digital hovering—intensive symptom monitoring and management. Our objective was to evaluate a digital platform that identifies and remotely monitors high-risk patients initiating antineoplastic therapy with the goal of preventing acute care visits.

METHODS:

This was a single-institution matched cohort quality improvement study conducted at a National Cancer Institute–designated cancer center between January 1, 2019, and March 31, 2020. Eligible patients were those initiating intravenous antineoplastic therapy who were identified as high risk for seeking acute care. Enrolled patients' symptoms were monitored using a digital platform. A dedicated team of clinicians managed reported symptoms. The primary outcomes of emergency department visits and hospitalizations within 6 months of treatment initiation were analyzed using cumulative incidence analyses with a competing risk of death.

RESULTS:

Eighty-one patients from the intervention arm were matched by stage and disease with contemporaneous high-risk control patients. The matched cohort had similar baseline characteristics. The cumulative incidence of an emergency department visit for the intervention cohort was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.37) at six months compared with 0.47 (95% CI, 0.36 to 0.58) in the control (P = .01) and of an inpatient admission was 0.23 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.33) in the intervention cohort versus 0.41 (95% CI, 0.30 to 0.51) in the control (P = .02).

CONCLUSION:

The narrow employment of technology solutions to complex care delivery challenges in oncology can improve outcomes and innovate care. This program was a first step in using a digital platform and a remote team to improve symptom care for high-risk patients.

INTRODUCTION

Acute care visits (emergency department [ED] or inpatient admissions) account for 48% of cancer care expenditures, and some are potentially preventable through more innovative outpatient care approaches.1,2 Predictive analytics and risk stratification models could focus time and effort on those most in need.3 Proactive symptom reporting has reduced ED visits and increased overall survival for patients with advanced cancer on treatment.4 The next step is to harness advances in technology and mobile applications to enable patients to report symptoms any time, enabling digital hovering—intensive monitoring and management of high-risk patients.3 This manuscript evaluates a technology-enabled remote patient monitoring (RPM) intervention, which identifies patients at high risk for an acute care visit, monitors symptoms daily, and intervenes as necessary.

METHODS

Study Population

Eligible patients were age 18 years or older, had a diagnosis of a solid tumor or lymphoma, and were determined to be high risk for an acute care encounter within 6 months of initiation of intravenous antineoplastic therapy (a cytotoxic, immunologic, or biologic agent). Patients were enrolled at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center's (MSK's) Westchester location between January 1, 2019, and March 31, 2020, when the program was suspended because of the COVID-19 pandemic. A waiver of informed consent from the MSK Institutional Review Board was granted for this quality improvement project. Patients were determined to be high risk by their medical oncologist using a web-based machine learning risk model for decision support, as well as prespecified clinical criteria, and were enrolled in the intervention at therapy initiation. Briefly, the decision-support risk model was a time-weighted least absolute shrinkage and selection operator framework refined to prospectively estimate the risk of a preventable ED visit within 6 months of treatment start on the basis of 270 clinically relevant data features from the electronic medical record (EMR).5 The model C-statistic was 0.65, which compares favorably with other models seeking to predict acute care in oncology patients.6-8 The model accessed the richness of the data in the EMR including common elements used in other risk models (eg, laboratory values like albumin) and more unique features that were found to be predictive, including referrals (eg, social work) and home medications (eg, opioids).5 The top quartile of patients identified by this model were considered high-risk and recommended for enrollment in the intervention. Patients in the other three quartiles could be enrolled at their medical oncologist's discretion if they possessed one or more of the following prespecified clinical criteria for high risk: (1) comorbidities that increased the risk of a treatment complication; (2) provider-identified barriers to care; (3) non-MSK ED visits or hospitalizations before treatment start; (4) inability to aliment sufficiently; (5) high tumor burden or site of metastasis concerning for symptom elicitation; (6) high psychosocial distress or multiple symptomatic complaints; (7) dose reduction with initial antineoplastic treatment; or (8) combined modality therapy. These criteria were developed on the basis of discussions with clinicians about relevant risk factors and were features missed by the predictive model because representative EMR data were lacking at treatment start.9 Patients were excluded if they did not have access to a smartphone, tablet, or computer; were in a therapeutic clinical trial; or if they could not speak English. Patients exited the program when they were no longer on active treatment.

Intervention

The technology-enabled platform that supports remote symptom monitoring and management of high-risk patients has been described elsewhere.9 The platform is integrated into the EMR and includes (1) a secure patient portal enabling communication and daily delivery of patient symptom assessments; (2) clinical alerts for concerning symptoms; and (3) a symptom trending application. Symptom assessments were based on the Patient-Reported Outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events and the ongoing Electronic Patient Reporting of Symptoms During Cancer Treatment trial.10,11 Assessments focused on symptoms driving acute care visits for patients on antineoplastic therapy and included pain, functional status, anorexia/dehydration, nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhea, and dyspnea.12 A dedicated team of oncology registered nurses (RNs) and nurse practitioners (NPs) monitored and managed reported symptoms. These clinicians acted as an extension of the primary oncology team, assisting with patient management exclusively through the platform. The scope of these clinicians management included symptom education, specialty referrals, the ordering of diagnostic tests, and the prescribing of supportive medications. If symptoms required in-person evaluation, patients were appropriately referred.9 If the patient's oncologist was not available to see the patient in clinic, the patient could be evaluated the same day at one of MSK's symptom care clinics that provide same-day appointments for medical problems related to cancer or cancer treatment.13

A prior feasibility and acceptability study of 100 patients enrolled in this intervention met its end points demonstrating that enrolled patients completed 56% of daily electronic patient‐reported outcome symptoms assessments (the number of completed daily electronic patient‐reported outcome symptom assessments divided by the number of assessments that were expected to be completed) and that 93% of patients report a severe (red) alert symptom during their monitoring period.9 In addition, we demonstrated that a patient reporting a severe (red) alert symptom had a three-fold greater rate of an acute care encounter within the next 7 days than a patient submitting an assessment without a severe symptom.14

Outcome

The primary outcome was acute care use defined as unanticipated ED visits and hospitalizations within six months of treatment initiation. Acute care data were available for MSK and surrounding partner hospitals throughout the study.

Matching

The machine learning model was run on a cohort of control patients from MSK Bergen, a regional location with similar patient demographics, and a site that shares oncologists and is roughly equidistant from MSK's main campus as MSK Westchester. A contemporaneous cohort of high-risk patients from MSK Bergen matched to RPM intervention enrollees on the basis of stage and disease site served as a control group. Because of sample size limitations, additional variables were not able to be used for the purposes of matching; however, comparisons of relevant covariates were made across the matched cohorts.

Statistical Analysis

Patient demographics and clinical variables were described using frequency (percent) for categorical variables, and median (interquartile range) for continuous variables. ED visits and hospitalizations within 6 months of treatment initiation were analyzed using cumulative incidence analyses with a competing risk of death. RPM intervention patients who did not experience an acute care event or death were censored at the end of program enrollment. Between-cohort comparisons were conducted using Gray's test. Analyses were performed in R v4.0.0.

Return on Investment

Two RNs and one NP actively monitored and managed enrolled patients' symptoms from 7 am to 7:30 pm, Monday to Friday. Weekend hours were the same, and patients were managed by one RN and one NP. The RPM intervention employed three full-time RNs (median annual salary: $107,700 US dollars [USD], total annual nursing cost including fringe: $413,568 USD), two full-time NPs, and two part-time NPs (median salary: $134,175 USD, total annual NP cost including fringe: $515,232 USD). Therefore, the total annual program cost was $928,800 USD. We did not include technology development costs in the return on investment (ROI) calculation as there were no ongoing informatics costs associated with the intervention once the platform was developed. To estimate savings from the program, facility services used by program participants were priced at local Medicare rates to align with salary expenses. Median Medicare payments were estimated at $994 USD for an ED visit and $13,148 USD for an inpatient admission. The median commercial payer payments for these services were $2,799 USD and $42,095 USD, respectively, on the basis of facility estimates from the RAND corporation for New York state.15 Savings resulting from ED visits were calculated only when there was no subsequent inpatient admission in accordance with standard payment policy. The ROI was calculated on the basis of a steady-state caseload per six months of 160 patients (80 patients per RN) multiplied by the mean savings in acute care payments in the intervention versus the control cohort.

RESULTS

Patient Demographics

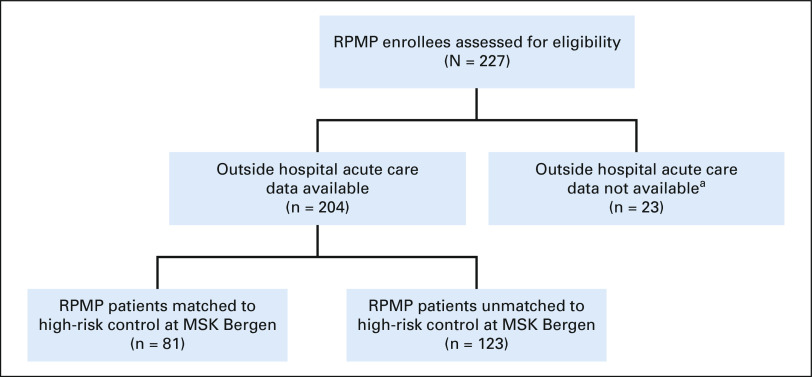

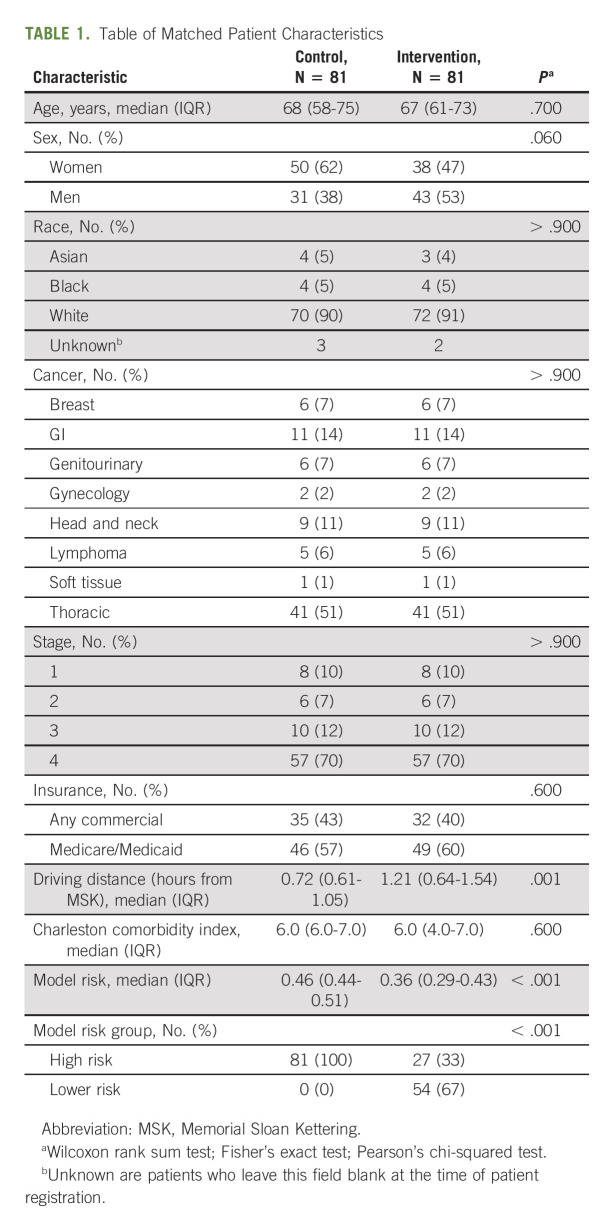

Between January 1, 2019, and March 31, 2020, 204 patients enrolled in the intervention, and 81 were matched to a control patient (Fig 1). Matched cohorts had similar baseline characteristics, including age, sex, race, comorbidities, and treatment (Table 1).

FIG 1.

Flow diagram. aOutside hospital data were not available for patients enrolled in the program before January 1, 2019, because of data sharing agreements with outside hospitals. MSK, Memorial Sloan Kettering; RPMP, remote patient monitoring program.

TABLE 1.

Table of Matched Patient Characteristics

Acute Care Use

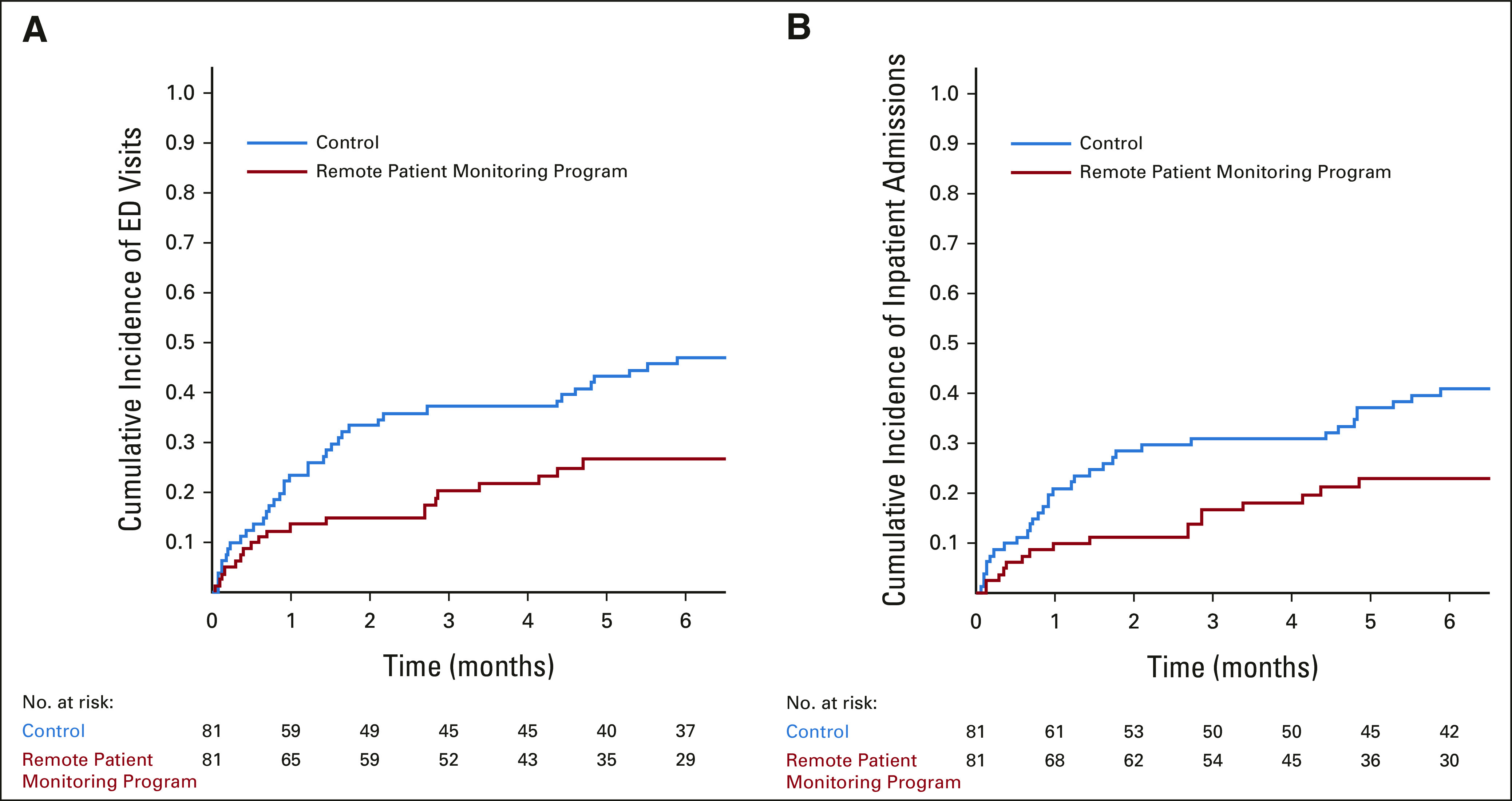

The cumulative incidence of an ED visit for the intervention cohort was 0.27 (95% CI, 0.17 to 0.37) at 6 months compared with 0.47 (95% CI, 0.36 to 0.58) in the control (P = .01). The cumulative incidence of an inpatient admission was 0.23 (95% CI, 0.14 to 0.33) in the intervention cohort versus 0.41 (95% CI, 0.30 to 0.51) in the control (P = .02; Fig 2).

FIG 2.

Cumulative incidence of acute care visits. (A) The cumulative incidence of ED visits visits by cohort. (B) The cumulative incidence of inpatient admissions by cohort. The number of patients at risk at each time point is shown below the graph. ED, emergency department.

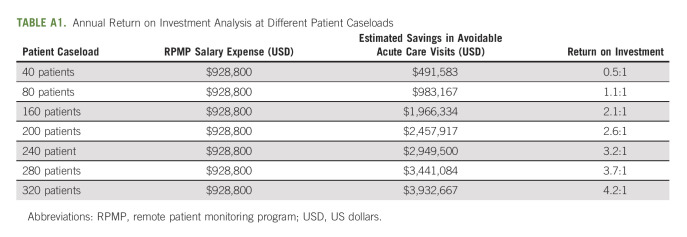

Return on Investment

The intervention was associated with a 20% absolute reduction in ED visits and an 18% absolute reduction in inpatient admissions. The payer mix for this population was 60% commercial/40% Medicare, and the mean annual savings from the program was estimated at $1,966,334 USD, whereas the annual salary cost was $928,800 USD. Therefore, the estimated program ROI was 2:1. Analysis was conducted to estimate ROI at various nurse-to-patient ratios (Appendix Table A1, online only).

DISCUSSION

This study investigates the effect of a digital platform and remote clinical team to identify, monitor, and manage high-risk patients at treatment initiation and adds to the literature on how technological advances can improve cancer care.16,17 Digital hovering reduced acute care visits, which tax patients and their caregivers physically, emotionally, and financially.

There are several limitations to our study. First, our comparator group was a matched cohort and we had to exclude 123 patients as we were unable to match them on stage and disease with a contemporaneous control. We planned to perform a randomized trial but our resources were redirected during the pandemic to remotely monitor patients with COVID-19 disease.18,19 The patients also were predominantly White and the practice settings drew from affluent neighborhoods, which could limit the generalizability of the findings. Second, a centralized team for remote monitoring might be cost-prohibitive to some practices. ROI was lower than cancer care interventions that employ other staffing models, such as lay navigators for symptom management.20 We are developing a care model that uses the primary team instead of a dedicated team, thus reducing investment costs. In addition, the benefits of reducing acute care visits are clear when one takes a macroeconomic view of medical expenditures, but to an individual practice or institution, the benefits may not be as apparent. Under fee-for-service arrangements, it is conceivable that an institution could be worse off financially by missing out on the revenue generated by providing care to hospitalized patients. We would argue, however, that there are increasing tailwinds to value-based care in oncology including the increased use of at-risk contracts and bundled payments. These changes are likely here to stay as demonstrated in the recent Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services announcement of a new oncology payment model, the Enhancing Oncology Model, which will require participating practices to be responsible for the total cost of care during a 6-month episode and participate in financial risk arrangements.21 Finally, the intervention consisted of multiple technology components: a machine learning model, daily symptom assessments, symptom alerts, and a symptom trending application. The value of each component needs to be better understood.

In summary, the narrow employment of technology solutions to complex care delivery challenges in oncology can improve outcomes and innovate care. The RPM intervention was a first step in using a digital platform to improve symptom care in the home for high-risk patients. This technology has applications during other high-risk periods of a patients' cancer journey, such as patients receiving treatments that place them at increased risk for toxicities,22 patients with partial small bowel obstructions, neutropenic fevers, or other conditions that require intensive monitoring, or after hospital discharge during the transition to home; thus, we are only starting to realize the potential benefits digital hovering could provide to our patients.

APPENDIX

TABLE A1.

Annual Return on Investment Analysis at Different Patient Caseloads

Bobby Daly

Leadership: Quadrant Holdings

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Quadrant Holdings (I), CVS Health, Walgreens Boots Alliance, Lilly (I), IBM, Pfizer (I), Cigna (I), Baxter (I), Zoetis (I)

Other Relationship: AstraZeneca

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/2785286

Katherine S. Panageas

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals

Aaron Begue

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer, Beam Therapeutics, Viatris

Isaac Wagner

Consulting or Advisory Role: Nan Fung Life Sciences

Brett A. Simon

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: patent application US2015/0290418, patent application US13/118109

Diane L. Reidy‐Lagunes

Honoraria: Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Lexicon, Advanced Accelerator Applications, ITM Oncologics, Chiasma

Research Funding: Novartis, Ipsen, Merck

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

PRIOR PRESENTATION

Presented at the 2022 annual ASCO meeting, June.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Bobby Daly, Kevin J. Nicholas, Alice Zervoudakis, Jessie Holland, Rori Salvaggio, Aaron Begue, Melissa Zablocki, Yeneat O. Chiu, Brett A. Simon, Wendy Perchick, Diane L. Reidy‐Lagunes

Financial support: Bobby Daly, Wendy Perchick

Administrative support: Bobby Daly, Nicholas Silva, Isaac Wagner, Yeneat O. Chiu, Wendy Perchick

Provision of study materials or patients: Bobby Daly, Alice Zervoudakis

Collection and assembly of data: Bobby Daly, Kevin J. Nicholas, Nicholas Silva, Elaine Duck, Alice Zervoudakis, Jessie Holland, Rori Salvaggio, Stefania Sokolowski, Diane L. Reidy-Lagunes

Data analysis and interpretation: Bobby Daly, Jessica Flynn, Katherine S. Panageas, Elaine Duck, Jessie Holland, Rori Salvaggio, Isaac Wagner, Stefania Sokolowski, Gilead J. Kuperman, Brett A. Simon, Diane L. Reidy‐Lagunes

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Association Between Remote Monitoring and Acute Care Visits in High-Risk Patients Initiating Intravenous Antineoplastic Therapy

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Bobby Daly

Leadership: Quadrant Holdings

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Quadrant Holdings (I), CVS Health, Walgreens Boots Alliance, Lilly (I), IBM, Pfizer (I), Cigna (I), Baxter (I), Zoetis (I)

Other Relationship: AstraZeneca

Open Payments Link: https://openpaymentsdata.cms.gov/physician/2785286

Katherine S. Panageas

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: AstraZeneca, Pfizer, Sunesis Pharmaceuticals

Aaron Begue

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: Pfizer, Beam Therapeutics, Viatris

Isaac Wagner

Consulting or Advisory Role: Nan Fung Life Sciences

Brett A. Simon

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: patent application US2015/0290418, patent application US13/118109

Diane L. Reidy‐Lagunes

Honoraria: Novartis

Consulting or Advisory Role: Lexicon, Advanced Accelerator Applications, ITM Oncologics, Chiasma

Research Funding: Novartis, Ipsen, Merck

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1. Brooks GA, Li L, Uno H, et al. Acute hospital care is the chief driver of regional spending variation in Medicare patients with advanced cancer. Health Aff. 2014;33:1793–1800. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Panattoni L, Fedorenko C, Greenwood-Hickman MA, et al. Characterizing potentially preventable cancer- and chronic disease-related emergency department use in the year after treatment initiation: A regional study. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e176–e185. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.028191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Handley NR, Schuchter LM, Bekelman JE. Best practices for reducing unplanned acute care for patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:306–313. doi: 10.1200/JOP.17.00081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom monitoring with patient-reported outcomes during routine cancer treatment: A randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–565. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Daly B, Gorenshteyn D, Nicholas KJ, et al. Building a clinically relevant risk model: Predicting risk of a potentially preventable acute care visit for patients starting antineoplastic treatment. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2020;4:275–289. doi: 10.1200/CCI.19.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Brooks GA, Kansagra AJ, Rao SR, et al. A clinical prediction model to assess risk for chemotherapy-related hospitalization in patients initiating palliative chemotherapy. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:441–447. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brooks GA, Uno H, Aiello Bowles EJ, et al. Hospitalization risk during chemotherapy for advanced cancer: Development and validation of risk stratification models using real-world data. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2019;3:1–10. doi: 10.1200/CCI.18.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Grant RC, Moineddin R, Yao Z, et al. Development and validation of a score to predict acute care use after initiation of systemic therapy for cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1912823. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.12823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Daly B, Kuperman G, Zervoudakis A, et al. InSight care pilot program: Redefining seeing a patient. JCO Oncol Pract. 2020;16:e1050–e1059. doi: 10.1200/OP.20.00214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences Patient-reported outcomes version of the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (PRO-CTCAE) 2019. https://healthcaredelivery.cancer.gov/pro-ctcae/

- 11.Clinicaltrials.gov Electronic Patient Reporting of Symptoms During Cancer Treatment (PRO-TECT) https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03249090

- 12. Daly B, Nicholas K, Gorenshteyn D, et al. Misery loves company: Presenting symptom clusters to urgent care by patients receiving antineoplastic therapy. J Oncol Pract. 2018;14:e484–e495. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.About the Symptomatic Care Clinic at MSK Westchester. https://www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/patient-education/about-symptomatic-care-clinic-msk-westchester [Google Scholar]

- 14. Daly B, Nicholas K, Flynn J, et al. Analysis of a remote monitoring program for symptoms among adults with cancer receiving antineoplastic therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5:e221078. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu JL, White C, Nowak SA, et al. An Assessment of the New York Health Act. RAND Corporation; 2018. p. 125.https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2424.html [Google Scholar]

- 16. Hong JC, Eclov NCW, Dalal NH, et al. System for high-intensity evaluation during radiation therapy (SHIELD-RT): A prospective randomized study of machine learning-directed clinical evaluations during radiation and chemoradiation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3652–3661. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kann BH, Thompson R, Thomas CR, Jr, et al. Artificial intelligence in oncology: Current applications and future directions. Oncology (Williston Park) 2019;33:46–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Daly B, Lauria TS, Holland JC, et al. Oncology patients' perspectives on remote patient monitoring for COVID-19. JCO Oncol Pract. 2021;17:e1278–e1285. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Majeed J, Garcia J, Holland J, et al. When a cancer patient tests positive for Covid-19 Harvard Business Review July 16, 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rocque GB, Pisu M, Jackson BE, et al. Resource use and Medicare costs during lay navigation for geriatric patients with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:817–825. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chong A, Witherspoon E, Honig B, et al. Reflections on the oncology care model and looking ahead to the enhancing oncology model. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022;18:685–690. doi: 10.1200/OP.22.00329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kirtane KS, Jim HS, Gonzalez BD, et al. Promise of patient-reported outcomes, biometric data, and remote monitoring for adoptive cellular therapy. JCO Clin Cancer Inform. 2022;6:e2200013. doi: 10.1200/CCI.22.00013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]