Abstract

We examined how demographic factors (gender, sexual orientation, racial group, age, body mass) were linked to measures of sociocultural appearance concerns derived from objectification theory and the tripartite influence model (McKinley & Hyde, 1996; Schaefer et al., 2015) among 11,620 adults. Men were less likely than women to report high body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, appearance-related media pressures, and family pressures; did not differ in peer pressures; and reported greater muscle/athletic internalization. Both men and women expressed greater desire for their bodies to look “very lean” than to look “very thin”. Compared to gay men, heterosexual men reported lower body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, peer pressures, and media pressures. Black women reported lower thin-ideal internalization than White, Hispanic, and Asian women, whereas Asian women reported greater family pressures. Being younger and having higher BMIs were associated with greater sociocultural appearance concerns across most measures. The variation in prevalence of sociocultural appearance concerns across these demographic groups highlights the need for interventions.

Keywords: Objectification theory, Tripartite influence model, Gender, Sexual orientation, Body image

1. Introduction

Body image refers to body-related self-perceptions and attitudes, including negative affect in the form of feeling dissatisfaction with one’s appearance and body overall (Cash & Pruzinsky, 1990). Body dissatisfaction is widespread and is implicated in the development of disordered eating patterns (Thompson & Stice, 2001), interest in cosmetic surgery (Frederick, Lever, & Peplau, 2007), avoidance of seeking routine healthcare (Mensinger, Tylka, & Calamari, 2018), psychological distress (Griffiths et al., 2016; Mitchison et al., 2017), lower sexual well-being (Gillen & Markey, 2018), and dissatisfaction with life (Frederick, Sandhu, Morse, & Swami, 2016). These negative outcomes linked to poor body image makes it critical to identify the risk factors that relate to poor body image, and the prevalence of these risk factors across different demographic groups.

In explicating factors underpinning body dissatisfaction, several theoretical models have been put forward to identify the sociocultural factors promoting poor body image, including objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997) and the tripartite influence model (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999). As a brief heuristic, we refer to these factors throughout the manuscript as sociocultural appearance concerns, which include body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, muscle/athletic internalization, and perceived media, peer, and family pressures. The current paper provides the rare opportunity to use a national dataset to examine how demographic factors, such as gender, sexual orientation, age, racial group, and body mass, are linked to these sociocultural appearance concerns.

1.1. Objectification theory and the tripartite influence model

Objectification theory highlights the role of sociocultural factors, positing that women in Western societies are routinely sexually objectified based on their physical appearance and internalize an observer’s perspective of their body (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). This sexual objectification occurs in everyday interactions and is also widespread in popular media (Graff, Murnen, & Krause, 2013; Hatton & Trautner, 2011; Murnen & Seabrook, 2012). The widespread nature of sexual objectification leads women to define their identity and worth through greater emphasis on their appearances, a process referred to as self-objectification. Self-objectification leads women to become more focused on how others judge their appearances, which results in greater vigilance and appearance checking behaviors pertaining to their physical characteristics, a process known as body surveillance.

Body surveillance is theorized to cause women to feel shame about their appearance when they believe they do not live up to sociocultural beauty ideals. Women attempt to ameliorate this shame by carefully managing how their appearance is presented to others. These appearance-management concerns and behaviors, which are linked to body surveillance, include dieting (Grabe & Hyde, 2006), disordered eating patterns (Tylka & Hill, 2004), self-weighing (Mercurio & Rima, 2011), wearing make-up (Smith et al., 2017), modifying appearance in order to look “sexy” (Smolak, Murnen, & Myers, 2014), and seeking or considering cosmetic surgery (Vaughan-Turnbull & Lewis, 2015). To date, objectification theory has amassed much supporting evidence relating body surveillance and objectification experiences to body dissatisfaction in women (Moradi & Huang, 2008).

Although both men and women find aspects of physical appearance desirable (Gallup & Frederick, 2010; Salska et al., 2008) and value “good looks” in a romantic partner (Buss, 1989; Fales et al., 2016), women, qualitatively, tend to have different experiences with sexual objectification than men. Women systematically encounter greater sexual harassment and sexual objectification and are more likely to be viewed as sexual conquests with little regard for their thoughts, feelings, or pleasure. Nearly every aspect of women’s appearance is evaluated, sexualized, and marked for potential modification or enhancement, from eyebrows to fingernails to lips and so on (Roberts, Calogero, & Gervais, 2018). Despite these qualitative differences in experiences, some processes identified by objectification theory, such as body surveillance, relate to body dissatisfaction in men (Frederick, Forbes, Grigorian, & Jarcho, 2007). Objectification theory constructs have been applied to understand the body image experiences of subgroups of men who experience increased sexual objectification, particularly gay men (Engeln-Maddox, Miller, & Doyle, 2011; Kozak, Frankenhauser, & Roberts, 2009; Martins, Tiggemann, & Kirkbride, 2007; Moradi & Huang, 2008; Wiseman & Moradi, 2010).

In addition to objectification theory, the tripartite influence model is one of the most widely accepted approaches for understanding body image. The model posits that perceived pressures from media, family, and peers to adhere to socially prestigious – and often phenotypically rare – body ideals results in unfavorable social comparisons and dissatisfaction with one’s own body (Thompson et al., 1999; Thompson, Schaefer, & Menzel, 2012). These social pressures lead to the internalization of appearance ideals, which facilitate the development of body dissatisfaction, maladaptive appearance management practices, and disordered eating (Rodgers & Chabrol, 2009; Rodgers, Chabrol, & Paxton, 2011; Rodgers, Paxton, & Chabrol, 2009; Thompson et al., 2012; Tylka, 2011; Tylka & Andorka, 2012).

1.2. Gender differences in sociocultural appearance concerns

Consistent with objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), studies of college students find that women engage in more body surveillance than men (Manago, Ward, Lemm, Reed, & Seabrook, 2015). More college women (43%) than men (25%) reported high levels of body surveillance, as defined by systematically scoring on the “agree” side of the scale across items (d = 0.48; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007). Popular media routinely features muscular, lean, and toned men as prestigious (Frederick, Fessler, & Haselton, 2005) and some conceptions of masculinity and male role norms are connected to the belief that men should be tough and muscular (Frederick, Buchanan, et al., 2007; Griffiths, Murray, & Touyz, 2015; McCreary, Saucier, & Courtenay, 2005). In contrast, the body types most often prized in popular media for women are slender (Spitzer, Henderson, & Zivian, 1999), toned, and/or with an hour-glass body shape (Sypeck et al., 2006). These differences in idealized body types for men and women are dramatically apparent when examining the popular dolls and action figures children play with (Boyd & Murnen, 2017), including Marvel superheroes (Burch & Johnsen, 2020). Women express attraction towards men who are relatively toned and muscular (Frederick & Haselton, 2007; Gray & Frederick, 2012; Sell, Lukazsweski, & Townsley, 2017), whereas men in industrialized countries tend to express the strongest preference for relatively slender women (Swami et al., 2010).

Given the discrepancies in pressures, it is not surprising that more women than men are dissatisfied with their weight (Peplau et al., 2009; Frederick et al., 2020; Karazsia, Murnen, & Tylka, 2017), show greater overweight preoccupation (Fallon, Harris, & Johnson, 2014), and report greater internalization of the thin-ideal (Cashel, Cunningham, Landeros, Cokley, & Muhammad, 2003). Conversely, men report greater dissatisfaction with their degree of muscularity and drive to engage in muscle building behaviors than women (d = 0.88; McCreary et al., 2005), a pattern seen across many studies (Karazsia et al., 2017; McCreary & Sasse, 2000; McCreary, Sasse, Saucier, & Dorsch, 2004; McCreary & Saucier, 2009).

Many men want to be simultaneously lean and muscular (Gray & Frederick, 2012). This greater internalization of a muscle/athletic ideal among men, however, comes with a caveat. In several studies, when questions include an emphasis on satisfaction with “muscle tone” or “muscle tone/size,” women were more likely than men to report dissatisfaction (Fallon et al., 2014; Frederick, Garcia, et al., 2020), or they did not differ from men (Kyrejto, Mosewich, Kowalski, Mack, & Crocker, 2008). These findings suggest that more men than women are concerned about their size, bulk, and/or strength, but concerns with tone are similar among men and women.

1.3. Sexual orientation differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

There are clear reasons to expect greater social appearance concerns among gay men than heterosexual men, and to expect greater concerns among heterosexual women and lesbian women. Gay men and heterosexual women likely face more objectification experiences because they are typically attracting men as partners. Men care more than women, on average, about having a long-term partner who is good-looking (Bailey, Gaulin, Agyei, & Gladue, 1994; Buss, 1989; Fales et al., 2016). Furthermore, media marketed to gay men often includes objectifying images (Saucier & Caron, 2008). This is not to imply that men and women face no objectification or judgments of their appearance from women. Some women do engage in some level of objectification (Lindner, Tantleff-Dunn, & Jentsch, 2012; Strelan & Hargreaves, 2005), and women do consider physical attractiveness when choosing a short-term or long-term mate (Bailey et al., 1994; Buss, 1989; Fales et al., 2016). The more extensive objectification exhibited by men, however, likely more dramatically shapes the body image of people objectified by men than by women.

Gay men are more likely than heterosexual men to reported disordered eating patterns (Murray et al., 2017). Meta-analyses repeatedly find that gay men report greater affective body dissatisfaction than heterosexual men (Morrison, Morrison, & Sager, 2004) and the same is typically true in large-scale national studies, although the effect sizes are usually small or small-to-moderate (Frederick & Essayli, 2016; Frederick, Garcia, et al., 2020; Frederick, Sandhu, et al., 2016; Peplau et al., 2009). In particular, gay men report more dissatisfaction with muscle tone and size than heterosexual men (Frederick & Essayli, 2016). In other research, gay men reported greater effects than heterosexual men of media on their body image (Austin et al., 2004; Carper, Negy, & Tantleff-Dunn, 2010; McArdle & Hill, 2009).

Turning to women, lesbian women reported less body surveillance than heterosexual women in one study (d = 0.76; Engeln-Maddox et al., 2011) but the reverse was found in another study (d = 0.45; Kozee & Tylka, 2006). Some research has found that lesbian women are less likely to internalize appearance norms (Bergeron & Senn, 1998; Share & Mintz, 2002). In another study, however, lesbian women did not differ from heterosexual women (Huxley, Halliwell, & Clarke, 2015).

1.4. Racial differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

People are often fetishized and objectified based on their racial group, which could further contribute to their body image concerns. Prejudice and discrimination experienced by racial minorities is theorized to heighten awareness of how their hair, skin color, and physical features are judged (Neal & Wilson, 1989). Examinations of how these experiences lead to group differences in body surveillance, internalization of ideals, or perceived sociocultural pressures is rarely examined. Many of the existing studies do not have sufficient sample sizes of minority participants to make these comparisons, and little is known about how the experiences of men differ across racial groups. Below we highlight some of the few studies that have made these comparisons.

One relatively consistent finding has been that Black women report lower body surveillance than White women (Breitkopf, Littleton, & Berenson, 2007; Claudat, Warren, & Durette, 2012; Hebl, King, & Lin, 2004). But, in one longitudinal study, Black women differed from White women at one wave of the study but not the other (Fitzsimmons & Bardone-Cone, 2011). In a study of college students, there were no significant differences in body surveillance between White, Asian, and Hispanic racial groups (Frederick & Forbes et al., 2007). In contrast, other research found that Asian and Latina women reported lower body surveillance than White women (Claudat et al., 2012) and that Asian women reported lower body surveillance than White women (Frederick, Kelly, Latner, Sandhu, & Tsong, 2016).

Similarly, to the findings for body surveillance, Black women report less internalization of media ideals than White women (Cashel et al., 2003; Quick & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2014; Rakhkovskaya & Warren, 2014; Warren, Gleaves, Cepeda‐Benito, Fernandez, & Rodriguez‐Ruiz, 2005; Warren, Gleaves, & Rakhkovskaya, 2013). The existing research finds lower internalization of the thin-ideal among Latinas than among Whites (Rakhkovskaya & Warren, 2016; Warren et al., 2005; Warren et al., 2013). Mixed evidence has been found for comparisons among other groups, with some studies finding no differences between Whites and Asians (Frederick, Kelly et al., 2016; Warren et al., 2013) and one study finding higher internalization by Asians (Hermes & Keel, 2003). In one study, Asian women reported greater family pressure than Whites, but no difference in peer or media pressure (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), which is consistent with qualitative research identifying family criticism of weight as a notable factor shaping body image among Asian women (Smart & Tsong, 2014).

Turning to muscularity, one study found that drive for muscularity was higher among British Black and South Asian men, who reported greater drive for muscularity than White men (Swami, 2016). Somewhat relatedly, another study found that Black boys were slightly more likely than White or Hispanic boys to participate in at least one sport, whereas there are no differences among girls (Turner, Perrin, Coyne-Beasley, Peterson, & Skinner, 2015). However, any clear conclusions about racial differences, beyond the consistent finding that Black women are less likely to internalize the thin-ideal than White women, are difficult to draw given the limited research directly comparing objectification and sociocultural theory constructs among men and women.

1.5. Age differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

Body image satisfaction is fairly similar across age groups (Tiggemann, 2004). As people age, they depart further from the youthful ideal featured as attractive and prestigious. As these changes in appearance are occurring, however, people take on new social roles, such as parenthood and employment, that become incorporated into their identities (Tiggemann, 2004; Greenleaf, 2005). Furthermore, at higher ages, individuals are more likely to be married. Having a stable fulfilling relationship reduces intrasexual competition for a mate with peers on the mating market, and appearance becomes a less critical criterion when seeking a mate (Fales et al., 2016), potentially reducing one’s sociocultural appearance concerns. Consistent with these perspectives, older women report lower body surveillance than younger women (Greenleaf, 2005; McKinley, 2006a; 2006b; Tiggemann & Lynch, 2001).

Similarly, for some men, concerns with muscularity and athleticism will decrease as they transition into older adulthood and take on additional social roles. Past research, however, has found only weak associations between age and concerns with muscle tone and size, with older men reporting slightly higher satisfaction than younger men (Frederick & Essayli, 2016).

1.6. Body mass differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

Men and women with higher body masses deviate more so from the slender body ideals represented as prestigious in many industrialized countries (Spitzer et al., 1999). It is well established that men and women with higher body masses are much more likely to report high levels of body dissatisfaction, particularly among people classified as overweight to obese (Fallon et al., 2014; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Frederick, Tomiyama, Bold, & Saguy, 2020; Frederick, Peplau, & Lever, 2006; Frederick, Sandhu, et al., 2016; Kruger, Lee, Ainsworth, & Macera, 2008; Peplau et al., 2009; Swami, Tran, Stieger, & Voracek, 2015). Some research suggests these associations are curvilinear, particularly for men, for whom very thin bodies and very high levels of body fat depart from the muscular ideal (Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Frederick, Garcia, et al., 2020; Frederick et al., 2006; Frederick, Sandhu, et al., 2016).

This link between BMI and body satisfaction is likely driven, in part, by people higher in BMI receiving greater stigma from others. For example, weight-based teasing from peers and parents is linked to weight gain, poor body image, dieting, and disordered eating (Puhl et al., 2017), and this weight-based stigma might increase sociocultural appearance concerns as well. This study enabled us to provide one of the few existing examinations of how BMI is linked to experiences of appearance-related pressures from peers, parents, and peers, and people’s internalizations of these messages.

1.7. Summary of goals and hypotheses

The current study examined how sociocultural appearance concerns vary according to demographic factors, specifically gender, sexual orientation, racial group, age, and body mass. Due to the rare opportunity afforded by this large national dataset, we provide a detailed and comprehensive summary of the prevalence and predictors of these concerns across demographic groups.

Furthermore, we also took this opportunity to examine some individual items from scales that might make unique contributions to the literature. For example, we investigated group differences in how concerns over body fat are revealed differently by the wording of an item. We believed that there might be gender differences in desires to be “thin” vs. “lean”, which is consistent with past research showing that drive for “leanness” is separable from drive for “thinness” or “muscularity” (Smolak & Murnen, 2008). Additionally, we examined differences in cognitive internalization vs. behavior. For example, we examined the importance of being athletic to participants vs. their actually engaging in behaviors to become more athletic, along with other individual items of interest. Many large-scale studies are only able to include one or two items measuring a construct rather than full psychometrically-tested scales, so conducting additional analyses based on single items provides a potential comparison point for future studies conducted with that constraint.

1.7.1. Hypothesis 1: gender comparisons

We hypothesized that more women than men would report body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, and pressures from peers, media, and family. In contrast, more men than women would report muscularity and athletic internalization.

1.7.2. Hypothesis 2: sexual orientation comparisons

We hypothesized that gay men and bisexual men would experience greater sociocultural appearance concerns than heterosexual men. The past literature on differences in sociocultural appearance concerns across sexual orientation groups among women is more mixed. Based on the existing theories and evidence, however, we tentatively hypothesized that heterosexual women would experience greater concerns than lesbian women.

1.7.3. Hypothesis 3: racial group comparisons

We hypothesized that Black women experience fewer sociocultural appearance concerns than other women and that Black men experience greater muscle/athletic internalization than other men. We expected that Hispanic women might report lower thin-ideal internalization that White women. Asian men and women were hypothesized to experience greater perceived family pressures. The remaining comparisons were exploratory.

1.7.4. Hypothesis 4: age comparisons

We hypothesized that older men and women experience relatively fewer sociocultural appearance concerns.

1.7.5. Hypothesis 5: BMI comparisons

We hypothesized that men and women with higher BMIs experience greater sociocultural appearance concerns, and that there would be a curvilinear association for men.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Data were drawn from the U.S. Body Project I, which is described in detail in the Procedures section. The sample was restricted to include only participants who completed the full survey and who fit the following criteria: (a) reported currently living in the United States; (b) completed all key body image items; (c) were aged 18–65; (d) had body mass indexes (BMI) ranging from 14.50 to 50.50 based on self-reported height and weight. Age and BMI restrictions were placed on the sample to prevent outliers or mis-entered values from having undue influence on the effect size estimates. A total of 13,518 people clicked on the survey, 12,571 answered the first question, and 12,151 completed the full survey. After applying the inclusion criteria, the analyzed sample included 11,620 participants. Key demographics are shown in Table 1. The current study relies on a national sample drawn from all 50 states, but it not a nationally representative sample. For example, Whites, women, and people with college degrees are overrepresented in the sample compared to national U.S. population. For more detailed demographics and a discussion of how the current sample compares to nationally representative datasets, please see Frederick and Crerand et al. (2022).

Table 1.

Demographics.

| Demographics | Overall | Men | Women | Demographics | Overall | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (M, SD) | 34.1 (10.7) | 33.0 (10.0) | 34.1 (10.7) | Hours Worked (M, SD) | 33.1 (15.6) | 36.1 (14.4) | 33.1 (15.6) |

| Years in U.S. (M, SD) | 33.1 (11.3) | 32.0 (10.5) | 33.1 (11.3) | BMI (M, SD) | 27.6 (6.3) | 27.5 (5.6) | 27.6 (6.3) |

| Gender (%, N) | Education (%, N) | ||||||

| Men | 45.6 (5293) | – | – | Some High School or Less | 0.6 (74) | 0.5 (28) | 0.7 (46) |

| Women | 54.4 (6327) | – | – | High School Degree | 9.1 (1052) | 9.8 (518) | 8.4 (534) |

| Racial group (%, N) | Some College | 32.3 (3749) | 32.5 (1718) | 32.1 (2031) | |||

| White | 75.2 (8742) | 74.5 (3945) | 75.8 (4797) | College Degree | 44.2 (5131) | 43.7 (2311) | 44.6 (2820) |

| Hispanic | 4.0 (470) | 5.0 (265) | 3.2 (205) | Advanced Degree | 13.9 (1614) | 13.6 (718) | 14.2 (896) |

| Black | 6.7 (774) | 5.6 (297) | 7.5 (477) | Orientation (%, N) | |||

| Asian | 6.1 (714) | 7.0 (370) | 5.4 (344) | Heterosexual | 88.3 (10,264) | 92.0 (4869) | 85.3 (5395) |

| Indian | 0.3 (34) | 0.3 (16) | 0.3 (18) | Gay or Lesbian | 3.5 (407) | 3.7 (194) | 3.4 (213) |

| Native American | 0.5 (55) | 0.5 (26) | 0.5 (29) | Bisexual | 6.8 (792) | 3.7 (194) | 9.5 (598) |

| Pacific Islander | 0.1 (16) | 0.1 (6) | 0.2 (10) | Asexual | 0.5 (56) | 0.2 (9) | 0.7 (47) |

| White-Hispanic | 1.9 (225) | 2.0 (108) | 1.8 (117) | Other | 0.9 (101) | 0.5 (27) | 1.2 (74) |

| White-Black | 0.8 (90) | 0.5 (29) | 1.0 (61) | BMI (%, N) | |||

| White-Asian | 1.0 (119) | 1.0 (54) | 1.0 (65) | Lowest BMI (Underweight) | 1.6 (190) | 1.2 (64) | 2.0 (126) |

| White-Middle Eastern | 0.9 (110) | 0.9 (45) | 1.0 (65) | Low BMI (Normal Weight) | 39.0 (4535) | 36.2 (1918) | 41.4 (2617) |

| Other | 2.3 (271) | 2.3 (132) | 2.2 (139) | Medium BMI (Overweight) | 31.3 (3632) | 36.8 (1947) | 26.6 (1685) |

| High I BMI (Obese I) | 15.1 (1755) | 15.4 (815) | 14.9 (940) | ||||

| In College (%, N) | 17.4 (2021) | 18.7 (988) | 16.3 (1033) | High II BMI (Obese II) | 7.2 (840) | 6.5 (343) | 7.9 (497) |

| High III BMI (Obese III) | 5.7 (668) | 3.9 (206) | 7.3 (462) | ||||

| Born In U.S. (%, N) | 94.0 (10,923) | 94.1 (4981) | 93.9 (5942) |

Note. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for each group are presented.

2.2. Procedure and overview of The U.S. Body Project I

The first author’s university institutional review board approved the study. Adult participants were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk, a widely used online panel system used by researchers to access adult populations (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, 2012, Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011, Kees, Berry, Burton, & Sheehan, 2017; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010; Robinson, Rosenzweig, Moss, & Litman, 2019). Participants were paid 51 cents for taking the survey. The survey was advertised with the title “Personal Attitudes Survey” and the description explained that “We are measuring personal attitudes and beliefs. The survey will take roughly 10–15 min to complete.” The general wording of the advertisement was used to avoid selectively recruiting people particularly interested in body image. After clicking on the advertisement, the participants read a consent form providing more details about the content of the study, including that it would contain items related to sex, love, work, and appearance. They were then given the option to continue with the survey or exit.

After providing informed consent, participants completed the numerical textbox questions (e.g., hours per week worked, number of times in love, sex frequency per week, longest relationship). These were followed by appearance evaluation (Cash, 2000), the SATAQ-4 (Schaefer et al., 2015), face satisfaction (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), overweight preoccupation (Cash, 2000), body image quality of life (Cash & Fleming, 2002), body surveillance (McKinley & Hyde, 1996), and finally demographics.

This manuscript is part of a series of papers emerging from The U.S. Body Project I. This project invited over 20 body image and eating disorder researchers, four sexuality researchers, and six computational scientists to apply their content and data-analytic expertize to the dataset. This project resulted in the following set of 11 papers for this special issue.

The first two papers examine how demographic factors are related to body satisfaction and overweight preoccupation (Frederick, Crerand, et al., 2022) and to measures derived from objectification theory and the tripartite influence model, including body surveillance, thin-ideal and muscular/athletic ideal internalization, and perceived peer, family, and media pressures (current paper). The second set of papers examine how these measures and demographic factors predict sexuality-related body image (Frederick, Gordon, et al., 2022) and face satisfaction (Frederick, Reynolds, et al., 2022).

The third set of papers use structural equation modeling to examine the links between sociocultural appearance concerns and body satisfaction among women and across BMI groups (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Pennesi, et al., 2022), among men and across different BMI groups (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Convertino, et al., 2022), and across racial groups (Frederick, Schaefer, et al., 2022) and sexual orientations (Frederick, Hazzard, Schaefer, Rodgers, et al., 2022).

The fourth set of papers focus on measurement issues by examining measurement invariance of the scales across different demographic groups (Hazzard, Schaefer, Thompson, Rodgers, & Frederick, 2022) and conducting a psychometric evaluation of an abbreviated version of the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory (Hazzard, Schaefer, Thompson, Murray, & Frederick, 2022). Finally, the last paper uses machine learning modeling to compare the effectiveness of nonlinear models vs. linear regression for predicting body image outcomes (Liang et al., 2022).

2.3. Measures

We describe the measures analyzed below. We include the Cronbach’s alpha for the overall sample, then the men, and then women in the sample for each measure.

2.3.1. Objectified body consciousness scale – body surveillance subscale

Participants completed the Body Surveillance scale, which assesses the extent to which people monitor how they appear to others (McKinley & Hyde, 1996). The scale contains eight items. In terms of operationalization, the scale includes items assessing social comparison (e.g., “I rarely compare how I look with how other people look”), focus on one’s own appearance (e.g., “During the day, I think about how I look many times”), monitoring and worry about how one appears to outside observers (e.g., “I rarely worry about how I look to other people”), and rejection of self-objectification (“I am more concerned about what my body can do than how it looks”). Two of the items refer explicitly to the body, two refer to feelings about clothing, and four refer to the overall looks which could apply to face, body, or both. Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree; 7 = Strongly Agree). Five of the items are reverse coded.

Items were averaged into a scale, with higher scores indicating greater body surveillance (α = 0.86;0.84;0.86). Due to the rare opportunity to examine body image concerns in a national sample using full validated scales (Table 2a), we also examined some of the individual items on these scales (Table 2b), which allows comparisons to existing and future national studies using only these items and not the full scale. We analyze all of these items in their original, non-reverse coded form. For example, on Table 2b, items marked with an (“H”) indicate that higher scores represent greater body surveillance, and items marked “(L)” indicate that lower scores represent high body surveillance.

Table 2a.

Multiple regression analyses predicting body surveillance and SATAQ-4 subscales.

| Body Surveillance | Thin-Ideal Internalization | Muscular/Athleticism Internalization | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Gender | .41*** | – | – | .29*** | – | – | −0.60*** | – | – |

| Gay/Lesbian | .01 | .53*** | −0.43*** | .03 | .33*** | −0.20** | −0.01 | −0.23** | .18** |

| Bisexual | −0.04 | −0.02 | −0.06 | −0.10** | .10 | −0.18*** | .14*** | −0.32*** | −0.06 |

| Other Orientation | −0.39*** | −0.18 | −0.46*** | −0.35*** | −0.23 | −0.40*** | −0.39*** | −0.89*** | −0.24** |

| Hispanic | .01 | −0.03 | 08 | −0.04 | −0.01 | −0.07 | .09* | .07 | .12 |

| Black | −0.12** | −0.11 | −0.14** | −0.39*** | −0.25*** | −0.48*** | .00 | .33*** | −0.19*** |

| Asian | −0.06 | −0.01 | −0.11* | .02 | .10 | −0.04 | −0.01 | .12* | −0.14* |

| Other Racial group | −.02 | .00 | −0.04 | −0.11** | −0.02 | −0.17*** | .04 | .16** | −0.04 |

| Age | −0.23*** | −0.24*** | −0.24*** | −0.17*** | −0.14*** | −0.20*** | −0.19*** | −0.23*** | −0.18*** |

| BMI | .13*** | .11*** | .15*** | .13*** | .17*** | .12*** | −0.03** | .04* | −0.09*** |

| BMI2 | −0.02** | −0.01 | −0.03** | −0.03*** | −0.05*** | −0.03** | −0.04*** | −0.07*** | −0.01 |

| Education | .03** | .05*** | .02 | .01 | .03* | −0.01 | .09*** | .08*** | .10*** |

| Adjusted. R2 | .09*** | .07*** | .07*** | .06*** | .04*** | .06*** | .16*** | .08*** | .06*** |

| F | 97.2 | 36.0 | 42.3 | 57.0 | 20.6 | 32.4 | 179.5 | 44.3 | 35.0 |

| df | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 |

| Peer Pressures | Media Pressures | Family Pressures | |||||||

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Gender | .05** | – | – | .53*** | – | – | .23*** | – | – |

| Gay/Lesbian | .06 | .19** | −0.05 | .18*** | .57*** | −0.17* | −0.03 | −0.01 | −0.06 |

| Bisexual | −0.04 | −0.07 | −0.03 | .14*** | .16* | .12** | .02 | −0.01 | .03 |

| Other Orientation | −0.27*** | −0.44** | −0.21* | −0.02 | .10 | −0.08 | −0.05 | .05 | −0.08 |

| Hispanic | −0.07 | −0.06 | −0.08 | −0.08 | −0.12 | −0.02 | .13** | .13* | .14* |

| Black | −0.11** | −0.01 | −0.17*** | −0.37*** | −0.28*** | −0.45*** | −0.09** | −0.07 | −0.12** |

| Asian | .18*** | .18** | .18** | −0.10** | −0.10 | −0.08 | .45*** | .33*** | .59*** |

| Other Racial group | −.03 | −0.04 | −0.02 | .02 | .03 | .00 | .09** | .07 | .10* |

| Age | −0.20*** | −0.21*** | −0.19*** | −0.11*** | −0.08*** | −0.15*** | −0.16*** | −0.15*** | −0.17*** |

| BMI | .29*** | .24*** | .33*** | .27*** | .23*** | .34*** | .38*** | .29*** | .45*** |

| BMI2 | −0.01* | −0.01 | −0.03** | −0.05*** | −0.02 | −0.10*** | −0.02*** | .01 | −0.06*** |

| Education | .00 | .00 | .01 | .06*** | .05** | .07*** | .04*** | .02 | .06*** |

| Adjusted. R2 | .10*** | .08*** | .11*** | .14*** | .06*** | .10*** | .15*** | .10*** | .17*** |

| F | 104.6 | 44.7 | 71.3 | 155.9 | 33.1 | 65.3 | 171.5 | 54.0 | 121.3 |

| df | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,619 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,619 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

The reference categories were men for gender, White for racial group, and heterosexual for sexual orientation.

Table 2b.

Multiple regression analyses predicting selected body surveillance and SATAQ-4 items.

| Low Social Comparison: I Rarely Compare How I Look With How Other People Look (L) | Low Self-Objectification: I Am More Concerned About What Body Can Do Than How It Looks (L) | Low Appearance Monitoring: I Rarely Worry About How I Look To Other People (L) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Gender | −0.34*** | – | – | −0.28*** | – | – | −0.30*** | – | – |

| Gay/Lesbian | .02 | −0.42*** | .41*** | .02 | −0.36*** | .33*** | −0.04 | −0.36*** | .25*** |

| Bisexual | .02 | .02 | .03 | .03 | −0.02 | .06 | .03 | −0.04 | .06 |

| Other Orientation | .19* | .07 | .23** | .40*** | .12 | .49*** | .12 | −0.11 | .20* |

| Hispanic | .09* | .13* | .04 | .04 | .04 | .02 | .05 | .03 | .05 |

| Black | .28*** | .23*** | .32*** | .10** | .12* | .09* | .19*** | .18** | .20*** |

| Asian | .11** | .10 | .03* | .06 | .00 | .10 | .03 | −0.02 | .07 |

| Other Race | .08* | .08 | .09 | .04 | .04 | .06 | .01 | −0.05 | .06 |

| Age | .18*** | .17*** | .19*** | .17*** | .16*** | .19*** | .12*** | .11*** | .14*** |

| BMI | −0.13*** | −0.10*** | −0.16*** | −0.10*** | −0.09*** | −0.11*** | −0.11*** | −0.08*** | −0.13*** |

| BMI2 | .01 | .00 | .02* | .01 | .00 | .02 | .00 | −0.01 | .02* |

| Education | −0.05*** | −0.05*** | −0.05*** | −0.01 | −0.03* | .01 | −0.03** | −0.04** | −0.02 |

| Adjusted. R 2 | .05*** | .04*** | .06*** | .05*** | .03*** | .04*** | .04*** | .03*** | .03*** |

| F | 70.3 | 22.6 | 35.2 | 49.1 | 17.7 | 25.1 | 43.0 | 13.4 | 17.2 |

| df | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11 6315 |

| Leanness Cognitions: I Want My Body To Look Very Lean | Athletic Cognitions: It Is Important For Me To Look Athletic | Athletic Behaviors: I Spend Lot Time Doing Things To Look Athletic | |||||||

| All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | All | Men | Women | |

| β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | β | |

| Gender | .14*** | – | – | −0.43*** | – | – | −0.44*** | – | – |

| Gay/Lesbian | .04 | .21** | −0.11 | −0.02 | −0.24*** | .15* | −0.10* | −0.06 | .04 |

| Bisexual | −0.14*** | −0.04 | −0.19*** | −0.17*** | −0.29*** | −0.12** | −0.12** | −0.21** | −0.07 |

| Other Orientation | −0.32*** | −0.36* | −0.31** | −0.35*** | −0.68*** | −0.25** | −0.37*** | −0.81*** | −0.24** |

| Hispanic | −0.03 | −0.03 | −0.03 | .08 | .08 | .09 | .10* | .05 | .12 |

| Black | −0.28*** | −0.17** | −0.36*** | −0.07 | .17** | −0.21*** | .02 | .27*** | −0.17*** |

| Asian | −0.01 | .03 | −0.04 | −0.10* | −0.01 | −0.18** | .03 | .13* | −0.11 |

| Other Racial group | −.06 | .03 | −0.13** | .07* | .15** | .02 | .03 | .12* | −0.04 |

| Age | −0.15*** | −0.13*** | −0.17*** | −0.15*** | −0.15*** | −0.15*** | −0.15*** | −0.22*** | −0.14*** |

| BMI | .06*** | .12*** | .04* | −0.07*** | −0.01 | −0.12*** | −0.08*** | .10*** | −0.14*** |

| BMI2 | −.03*** | −0.05*** | −0.02* | −0.03*** | −0.06*** | .00 | −0.04*** | −0.06*** | −0.01 |

| Education | .02* | .02 | .02 | .12*** | .11*** | .13*** | .07*** | .06*** | .08*** |

| Adjusted. R 2 | .03*** | .02*** | .03*** | .10*** | .06*** | .06*** | .11*** | .06*** | .05*** |

| F | 29.4 | 12.6 | 21.2 | 114.0 | 29.4 | 37.2 | 118.9 | 31.8 | 32.9 |

| df | 12 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,619 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 | 12, 11,607 | 11, 5281 | 11, 6315 |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

The dummy coded reference categories were men for gender, White for racial group, and heterosexual for sexual orientation.

2.3.2. Sociocultural attitudes towards appearance questionnaire-4

The Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4; Schaefer et al., 2015) contains subscales with four items assessing appearance-related pressures from family (α = 0.91;0.89;0.92), peers (α = 0.93;0.92;0.94), and media (e.g., “I feel pressure from the media to look in better shape;” α = 0.97;0.95;0.97). Responses were recorded on the previously described 5-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely Disagree; 5 = Definitely Agree). The items were averaged for each subscale with higher scores indicating greater pressures.

The thin-ideal internalization subscale consists of five items, but one item was inadvertently omitted (“I want my body to look like it has little fat”), leading us to average the remaining four items (e.g., “I want my body to look very thin;” α = 0.84;0.79;0.87). These four items were connected by one underlying factor (Frederick, Hazzard, Schaefer, Thompson, et al., 2022). As described below, we also performed some analyzes on the individual items comprising the scale.

The muscular/athletic internalization measure included five items (e.g., “It is important for me to look athletic;” “I spend a lot of time doing things to look more muscular;” α = 0.92;0.90;0.91). Recent research raised two concerns with this subscale. First, in contrast to the thin ideal subscale which focuses only on cognitive aspects of internalization, this muscular/athleticism subscale includes items on behaviors as well. The second concern is that three items focus on athleticism and two on muscularity. These two forms of muscularity internalizations might be highly correlated with each other, but factor analyses also show they can be distinct (Schaefer, Harriger, Heinberg, Soderberg, & Thompson, 2017). Therefore, in addition to averaging the items as part of the five-item scale, we also analyzed each item separately.

2.3.3. Body Mass Index (BMI)

Using the self-reported height and weight data we calculated BMI. We then divided participants into the traditional BMI categories used by the CDC: Underweight (14.5–18.49), Normal or Healthy (18.5–24.9), Overweight (25–29.9), Obese I (30–34.9), Obese II (35–39.9), and Obese III (40 and above). We hasten to add that these widely-used categories were chosen as a heuristic so that the BMI results could be compared to existing studies, and do not represent uniform endorsement of the categories by the entire authorship team in terms of semantic accuracy or as clear indicators of a person’s health status (e.g., see Tomiyama, Hunger, Nguyen-Cuu, & Wells, 2016). To avoid any stigmatizing effects of these labels, we instead label these BMI groups as Lowest (Underweight), Low (Normal), Medium (Overweight), and High (Obese) Weight groups from this point forward.

2.4. Overview of data analytic approach

2.4.1. Effect sizes

What is considered a small, moderate, or large effect size can vary dramatically based on the research question of interest. As a very rough guide, Cohen (1988) suggests that effect size d can be interpreted as small (0.20), moderate (0.50), or large (0.80). These values correspond to Pearson’s r correlations of .10, .24, and .37. Ferguson (2009, p. 533) suggested somewhat higher thresholds for what should be considered the “recommended minimum effect size representing a ‘practically’ significant effect for social science data” (d = 0.41; β or r = .20).

With very large sample sizes, it is possible for even miniscule effects to be statistically significant at traditional thresholds (p < .05). Therefore, we note in the tables whether effects were significant at the p < .05 .01, or .001 levels, and emphasize effect sizes when presenting and discussing the results with an emphasis on the results significant at the p < .001 level due to the large sample size and multiple statistical comparisons.

For this paper, we elected to highlight statistically significant findings with Cohen’s d values greater than |0.19|, β values greater than |.09|, and percentage differences greater than eight percentage points. We draw particular attention to Cohen’s d values greater than |0.29| and β values greater than |.19|.

2.4.2. Frequency distributions and percentages

Consistent with past research, we present frequency distributions showing the percentage of participants falling on different points on the Likert scale to highlight the distribution of low and high body satisfaction across different groups (e.g., Cash & Henry, 1995; Fallon et al., 2014; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016; Peplau et al., 2009). For example, we present the percentage of people who systematically are on the “agree” end of the Likert scale when asked if they want their body to look very thin. This strategy of reporting the percentage of people in each group who embrace this attitude maximizes the accessibility of the findings to the lay public, clinicians, and scientists, in conjunction with the more advanced statistical analyses. It also encourages thinking about differences across groups in terms of not just the central tendencies, but also to the variations of experiences with groups and the overlaps in experiences across groups.

For each of the measures with 5-point scales, we calculated the percentage of people who systematically fell below the midpoint of the Likert scale, Low with mean scores of 1–2.74, at the midpoint, Neutral with mean scores 2.75–3.25, or systematically above the midpoint, High with mean scores 3.26–5.0. For example, the “high thin-ideal internalization” category included the participants who tended to agree that they wanted to be thin, whereas the “low thin-ideal internalization” category included the participants who tended to disagree that they wanted to be thin.

For the 7-point scales, consistent with past research (e.g., Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007), we used the categories Low (1–3.49), Neutral (3.5–4.5), and High (4.51–7.0). For the standard body surveillance measure containing all of the averaged items, high body surveillance indicates they systematically engage in body surveillance, whereas low body surveillance indicates they did not engage in routine body surveillance.

For the individual items on the body surveillance scale, categories were created based on the original, non-reverse coded, items. For five of these items, low scores actually indicate high body surveillance. These individual body surveillance items where disagreement is indicative of engaging in body surveillance are marked in Table 2b–4 with an “(L)” and individual items where agreement with items is indicative of body surveillance are marked with an “(H).” For example, scoring high on the “(H)” items such as “During the day, I think about how I look many times” indicates greater body surveillance. In contrast, scoring low on the “(L)” items such as “I rarely compare how I look with how other people look” is a sign of engaging in greater body surveillance.

Table 4.

Prevalence of high body surveillance, internalization, and perceived appearance pressures among men and women.

| White | Hispanic | Black | Asian | Under-weight | Normal | Over-weight | Obese I | Obese II | Obese III | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | M (W) | |

| % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | |

| High Body Surveillance | 26 (42) | 25 (45) | 21 (35) | 23 (38) | 14 (35) | 24 (38) | 24 (41) | 27 (47) | 34 (47) | 30 (47) |

| High Thin-Ideal Internalization | 28 (43) | 32 (45) | 20 (28) | 31 (44) | 22 (35) | 23 (41) | 29 (40) | 32 (46) | 40 (50) | 35 (44) |

| High Muscle/Athletic Internalization | 44 (22) | 53 (29) | 63 (18) | 58 (26) | 36 (29) | 49 (27) | 52 (20) | 43 (18) | 37 (18) | 33 (12) |

| High Peer Pressure | 11 (12) | 12 (12) | 12 (11) | 14 (12) | 08 (09) | 07 (07) | 11 (11) | 15 (16) | 22 (22) | 23 (27) |

| High Media Pressure | 36 (61) | 34 (61) | 24 (45) | 27 (53) | 08 (36) | 26 (50) | 35 (63) | 46 (70) | 53 (75) | 53 (72) |

| High Family Pressure | 11 (19) | 15 (25) | 11 (18) | 15 (32) | 06 (10) | 06 (10) | 10 (21) | 18 (30) | 26 (40) | 29 (43) |

| Agree: I want body to look very lean | 59 (67) | 62 (65) | 51 (56) | 60 (67) | 39 (49) | 55 (67) | 61 (64) | 61 (67) | 67 (65) | 58 (61) |

| Agree: I want my body to look very thin | 25 (41) | 26 (37) | 15 (24) | 25 (39) | 30 (37) | 23 (41) | 23 (36) | 26 (40) | 28 (41) | 29 (41) |

| Agree: Important for me look athletic | 20 (37) | 16 (32) | 15 (44) | 12 (35) | 28 (40) | 16 (30) | 16 (39) | 22 (42) | 23 (43) | 33 (50) |

| Agree: Spend lot time doing things athletic | 35 (20) | 40 (28) | 48 (16) | 47 (23) | 30 (26) | 39 (26) | 41 (19) | 31 (14) | 26 (14) | 21 (10) |

| Agree: Spend lot time doing things muscular | 33 (15) | 37 (20) | 50 (13) | 43 (17) | 28 (18) | 36 (19) | 39 (13) | 31 (10) | 24 (10) | 24 (08) |

| Disagree: Rarely compare looks to others (L) | 47 (63) | 43 (59) | 39 (51) | 44 (58) | 47 (57) | 44 (59) | 45 (61) | 48 (65) | 54 (68) | 54 (69) |

| Disagree: More concern what body can do (L) | 25 (37) | 21 (33) | 22 (35) | 20 (32) | 22 (35) | 22 (33) | 23 (36) | 26 (41) | 32 (41) | 33 (44) |

| Disagree: Rarely worry how look to others (L) | 44 (59) | 40 (54) | 35 (52) | 40 (55) | 42 (59) | 42 (54) | 40 (57) | 45 (62) | 52 (66) | 55 (65) |

| Hetero. | Gay/Les. | Bisexual | Other | 18–24 | 25–29 | 30–39 | 40–49 | 50–65 | ||

| % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | % (%) | ||

| High Body surveillance | 24 (41) | 49 (27) | 31 (49) | − (34) | 31 (48) | 27 (45) | 26 (44) | 22 (38) | 12 (25) | |

| High Thin-Ideal Internalization | 28 (43) | 41 (37) | 34 (43) | − (30) | 31 (52) | 32 (44) | 26 (42) | 27 (36) | 20 (33) | |

| High Muscle/Athletic Internalization | 48 (22) | 40 (30) | 38 (24) | − (20) | 59 (30) | 54 (25) | 45 (23) | 41 (17) | 25 (11) | |

| High Peer Pressure | 11 (12) | 19 (11) | 13 (16) | − (12) | 16 (19) | 16 (14) | 09 (11) | 07 (08) | 03 (07) | |

| High Media Pressure | 34 (59) | 58 (52) | 43 (69) | − (60) | 34 (63) | 37 (62) | 33 (61) | 38 (54) | 32 (54) | |

| High Family Pressure | 11 (20) | 15 (20) | 13 (27) | − (25) | 14 (26) | 14 (23) | 11 (20) | 08 (17) | 05 (14) | |

| Agree: I want body to look very lean | 59 (66) | 68 (61) | 60 (61) | − (53) | 61 (72) | 62 (68) | 59 (67) | 58 (59) | 48 (56) | |

| Agree: I want my body to look very thin | 23 (40) | 37 (35) | 33 (37) | − (31) | 25 (48) | 27 (39) | 22 (39) | 22 (34) | 24 (33) | |

| Agree: Important for me look athletic | 17 (37) | 27 (30) | 30 (41) | − (42) | 15 (32) | 17 (34) | 18 (34) | 19 (41) | 31 (51) | |

| Agree: Spend lot time doing things athletic | 38 (20) | 29 (21) | 30 (22) | − (21) | 45 (26) | 41 (24) | 36 (22) | 29 (15) | 21 (11) | |

| Agree: Spend lot time doing things muscular | 36 (15) | 26 (17) | 26 (17) | − (13) | 45 (21) | 41 (17) | 33 (16) | 27 (09) | 16 (08) | |

| Disagree: Rarely compare looks to others (L) | 45 (62) | 64 (42) | 44 (65) | − (57) | 50 (65) | 48 (65) | 47 (65) | 46 (58) | 29 (48) | |

| Disagree: More concern what body can do (L) | 23 (36) | 40 (26) | 24 (41) | − (21) | 25 (38) | 25 (39) | 26 (40) | 24 (34) | 13 (24) | |

| Disagree: Rarely worry how look to others (L) | 42 (58) | 58 (47) | 48 (61) | − (52) | 38 (61) | 45 (61) | 43 (59) | 40 (56) | 35 (48) |

Note. In each cell, the first number represents the percentage of men who fell into the categories generally associated with poor body image (e.g., “high” body surveillance, 4.51–7.00; “high” family pressures 3.51–5.00; or disagreeing that they rarely compare their looks to others, (“low”) 1.00–3.49). The second number (in parentheses) represents the percentage of women. For example, 26% of White men (and 42% of White women) reported high body surveillance. Only data for cells with at least 40 participants are shown.

2.4.3. Regression analyses examining demographic predictors of body surveillance and appearance pressures

We first conducted multiple regression analyses with each of the demographic predictors entered: gender, sexual orientation, racial group, age, BMI, BMI-squared for the curvilinear effect, and education (Table 2). For dummy codes, men were coded as 0 vs. women, heterosexuals were coded as 0 vs. gay/lesbian, bisexual, and then also an “other” category collapsing all other respondents, and Whites were coded as 0 vs. Black, Hispanic, Asian, and then also an “other” category collapsing all other respondents. The “other” categories were created because each individual response for sexual orientation, such as asexual, pansexual, demisexual, and racial group, such as Indian, Pacific Islander, Biracial: White-Black, contained small sample sizes. Collapsing them into one category was done only to ensure they were not excluded from the analyzes via listwise deletion and is not meant to indicate that the “other” category represents a shared overarching psychological construct or identity. Across all regression analyses, collinearity diagnostics did not identify high degrees of multicollinearity. Most VIF values fell below 2.0, all were below 4.5.

The regression analyses were conducted first for the whole sample and then separately by gender. All continuous predictor and outcome measures were z-scored prior to the regressions, both for the full sample and then separately within each gender for the gender-specific analyses. We focused on the following outcome measures: body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, muscular/athletic ideal internalization, peer pressure, media pressure, and parental pressure (Table 2a). We also examined individual items from these scales, including three from the body surveillance scale – social comparison, self-objectification, worry/monitoring appearance – and three from the thin and muscular/athletic internalization scales – wanting to be very lean, wanting to be athletic, engaging in behaviors to increase athleticism – shown in Table 2b.

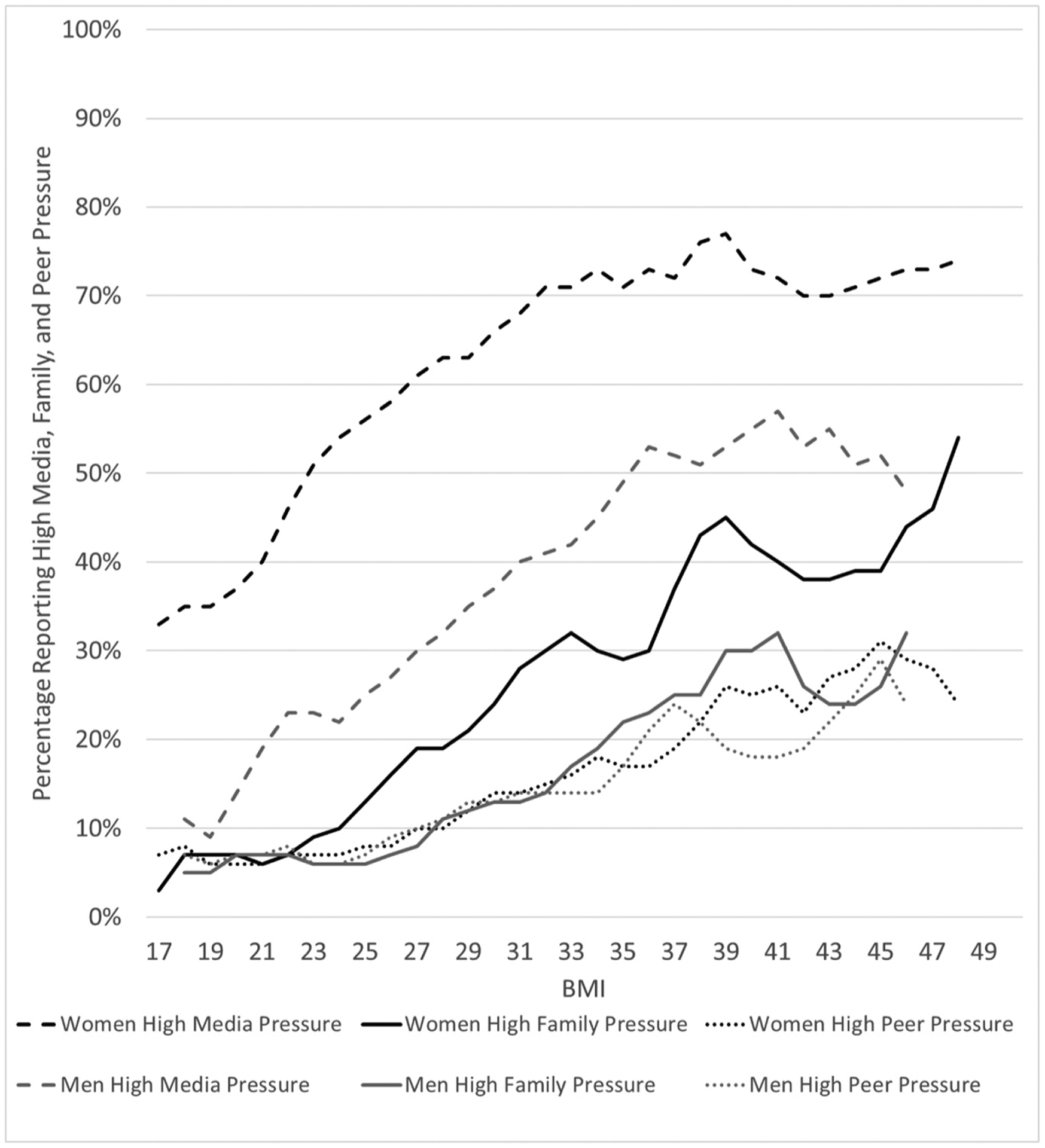

We then present gender differences in the overall prevalence of low, neutral, and high body image for all scale scores and individual items of interest, along with t-tests and Cohen’s d comparing men and women (Table 3). We then focus our attention on sexual orientation, racial group, age, and body mass differences in the prevalence of poor body image, such as high body surveillance and high perceived peer pressure, among each gender for selected measures and items (Table 4) along with t-tests and Cohen’s d comparing examining the size of the sexual orientation differences (Table 5a) and racial group differences (Table 5b). Finally, we draw attention to the powerful associations of body mass and gender to high perceived peer, media, and family appearance pressures (Fig. 1). The details of these findings are addressed in the following sections, along with follow-up t-tests, ANOVAs, and/or Chi-Square analyses to further investigate the patterns.

Table 3.

Prevalence of low (disagree), neutral, and high (agree) scores on body image measures.

| Men | Women | Vs. | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low % | Neutral % | High % | M | SD | Low % | Neutral % | High % | M | SD | d | |

| Body Surveillance | |||||||||||

| Overall scale (H) | 36 | 38 | 26 | 3.77 | 1.22 | 25 | 34 | 41 | 4.24 | 1.31 | −0.37*** |

| I often worry if clothes I wear make me look good (H) | 39 | 17 | 44 | 4.06 | 1.76 | 29 | 12 | 59 | 4.62 | 1.84 | −0.31*** |

| During the day, I think about how I look many times (H) | 43 | 17 | 40 | 3.94 | 1.77 | 39 | 13 | 48 | 4.27 | 1.90 | −0.18*** |

| Rarely think about looks (L) | 62 | 11 | 28 | 3.50 | 1.76 | 77 | 06 | 17 | 2.85 | 1.60 | 0.39*** |

| I rarely worry about how I look to other people (L) | 43 | 17 | 40 | 4.11 | 1.83 | 58 | 12 | 30 | 3.59 | 1.88 | 0.28*** |

| More concerned about what body can do than how look (L) | 24 | 24 | 52 | 4.70 | 1.73 | 36 | 20 | 44 | 4.26 | 1.85 | 0.24*** |

| More important clothes comfortable than look good (L) | 27 | 16 | 57 | 4.75 | 1.75 | 36 | 14 | 50 | 4.36 | 1.83 | 0.22*** |

| I think more about how my body feels than body looks (L) | 24 | 20 | 56 | 4.71 | 1.67 | 35 | 14 | 51 | 4.42 | 1.85 | 0.16*** |

| I rarely compare how I look with how other people look (L) | 46 | 15 | 39 | 4.05 | 1.88 | 62 | 09 | 29 | 3.46 | 1.97 | 0.31*** |

| SATAQ-4 | |||||||||||

| Thin-Ideal Internalization | 41 | 31 | 28 | 2.85 | 0.89 | 34 | 24 | 42 | 3.09 | 1.05 | −0.24*** |

| Muscle/Athletic Internalization | 30 | 23 | 47 | 3.18 | 0.99 | 59 | 19 | 22 | 2.49 | 1.01 | 0.69*** |

| Peer Pressure | 78 | 11 | 11 | 1.92 | 0.98 | 77 | 11 | 12 | 1.93 | 1.02 | −0.01 |

| Media Pressure | 49 | 16 | 35 | 2.67 | 1.29 | 29 | 11 | 60 | 3.38 | 1.34 | −0.54*** |

| Family Pressure | 75 | 14 | 11 | 2.00 | 1.29 | 68 | 12 | 20 | 2.23 | 1.17 | −0.19*** |

| Thin-Ideal Specific Items | |||||||||||

| Want body to look very lean | 22 | 19 | 59 | 3.42 | 1.09 | 21 | 13 | 66 | 3.53 | 1.15 | −0.10*** |

| Want body to look very thin | 53 | 23 | 24 | 2.57 | 1.10 | 43 | 18 | 39 | 2.92 | 1.23 | −0.30*** |

| Muscle/Athletic Specific Items | |||||||||||

| Important for me look athletic | 19 | 19 | 63 | 3.57 | 1.06 | 37 | 21 | 42 | 3.02 | 1.19 | 0.49*** |

| I spend a lot time doing things to look more athletic | 42 | 21 | 37 | 2.90 | 1.22 | 64 | 15 | 21 | 2.31 | 1.17 | 0.49*** |

| I think a lot looking athletic | 31 | 20 | 49 | 3.19 | 1.18 | 54 | 16 | 30 | 2.57 | 1.24 | 0.51*** |

| I think a lot looking muscular | 26 | 20 | 54 | 3.37 | 1.16 | 59 | 18 | 23 | 2.43 | 1.17 | 0.81*** |

| I spend a lot of time doing things to look more muscular | 44 | 21 | 35 | 2.86 | 1.23 | 71 | 14 | 15 | 2.12 | 1.10 | 0.64*** |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Frequency distributions are provided to show the percentage of men and women who scored on the low, neutral, or high end of each body image measure. For example, 30% of men reported low body surveillance, systematically below the midpoint of the Likert scale (1–3.49 out of 7.0). Means and standard deviations for each sex are presented. Effect size d and statistical significance for differences between men and women are shown in the last column. A positive effect size indicates that men scored higher on the measure than women (e.g., men reported higher appearance evaluation, d = 0.15). A negative effect size indicates that men scored lower on the measure than women (e.g., men reported lower preoccupation with weight, d = − 0.47). For the body surveillance items, (H) denotes that high scores indicate high body surveillance (e.g., agreeing that “I often worry if the clothes I wear make me look good,” and (L) denotes that low scores indicate high body surveillance (e.g., disagreeing that “I rarely think about my looks”).

Table 5a.

Sexual orientation differences in body surveillance, internalization, and perceived appearance pressures.

| Body Surveillance | Thin-Ideal Internalization | Muscular/Athleticism Internalization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual M (SD) | 3.75 (1.20) | 4.25 (1.30) | 2.83 (0.88) | 3.10 (1.03) | 3.20 (0.98) | 2.48 (1.00) |

| Gay/Lesbian M (SD) | 4.42 (1.29) | 3.77 (1.38) | 3.13 (0.94) | 2.95 (1.04) | 2.97 (1.08) | 2.70 (1.04) |

| Bisexual M (SD) | 3.79 (1.43) | 4.40 (1.37) | 2.95 (1.01) | 3.05 (1.14) | 2.90 (1.11) | 2.49 (1.07) |

| Comparisons | ||||||

| Hetero. vs. Gay/Lesbian d | −0.56*** | 0.37*** | −0.34*** | 0.15* | 0.23** | −0.22** |

| Hetero. vs. Bisexual d | −0.03 | −0.11* | −0.14 | 0.05 | 0.30*** | −0.01 |

| Gay/Lesbian vs. Bisexual d | 0.46*** | −0.46*** | 0.18 | −0.09 | 0.06 | 0.20** |

| Perceived Peer Pressures | Perceived Media Pressures | Perceived Family Pressures | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Sexual Orientation | ||||||

| Heterosexual M (SD) | 1.92 (0.97) | 1.92 (1.01) | 2.63 (1.28) | 3.35 (1.33) | 2.00 (0.98) | 2.21 (1.15) |

| Gay/Lesbian M (SD) | 2.12 (1.09) | 1.93 (1.08) | 3.37 (1.21) | 3.21 (1.41) | 1.99 (1.06) | 2.20 (1.20) |

| Bisexual M (SD) | 1.91 (1.01) | 2.07 (1.10) | 2.89 (1.38) | 3.68 (1.33) | 2.05 (1.04) | 2.42 (1.25) |

| Comparisons | ||||||

| Hetero. vs. Gay/Lesbian d | −0.21** | −0.01 | −0.58*** | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.01 |

| Hetero. vs. Bisexual d | 0.01 | −0.15** | −0.20** | −0.25*** | −0.05 | −0.18*** |

| Gay/Lesbian vs. Bisexual d | 0.20* | −0.13 | 0.37*** | −0.35*** | −0.06 | −0.18* |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for each group are presented. Effect size d and statistical significance for differences between each group are shown. A positive effect size indicates that the first group listed scored higher than the second group (e.g., gay men reported greater body surveillance than bisexual men, d = 0.46). A negative effect size indicates that the first group listed scored lower than the second group (e.g., heterosexual men reported lower overall body surveillance than gay men, d = − 0.56).

Table 5b.

Racial differences in body surveillance, internalization, and perceived appearance pressures.

| Body Surveillance | Thin-Ideal Internalization | Muscular/Athleticism Internalization | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Racial group | ||||||

| White M (SD) | 3.77 (1.25) | 4.24 (1.32) | 2.85 (0.89) | 3.13 (1.03) | 3.12 (0.99) | 2.49 (1.01) |

| Hispanic M (SD) | 3.81 (1.11) | 4.47 (1.27) | 2.88 (0.94) | 3.15 (1.08) | 3.27 (0.98) | 2.69 (1.09) |

| Black M (SD) | 3.64 (1.13) | 4.16 (1.28) | 2.63 (0.88) | 2.69 (1.08) | 3.45 (1.01) | 2.32 (1.01) |

| Asian M (SD) | 3.82 (1.09) | 4.17 (1.23) | 2.93 (0.85) | 3.14 (1.01) | 3.38 (0.88) | 2.54 (1.02) |

| Comparisons | ||||||

| White vs. Hispanic d | −0.03 | −0.17* | −0.03 | −0.02 | −0.15* | −0.20** |

| White vs. Black d | 0.10 | 0.06 | 0.25*** | 0.43*** | −0.33*** | 0.17** |

| White vs. Asian d | −0.04 | 0.05 | −0.09 | −0.01 | −0.27*** | −0.05 |

| Hispanic vs. Black d | 0.15 | 0.24** | 0.28** | 0.43*** | −0.18* | 0.36*** |

| Hispanic vs. Asian d | −0.01 | 0.24* | −0.06 | 0.01 | −0.12 | 0.14** |

| Black vs. Asian d | −0.16 | −0.01 | −0.35*** | −0.43*** | 0.07 | −0.22** |

| Perceived Peer Pressures | Perceived Media Pressures | Perceived Family Pressures | ||||

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| Racial group | ||||||

| White M (SD) | 1.91 (0.97) | 1.93 (1.02) | 2.71 (1.29) | 3.43 (1.33) | 1.98 (0.97) | 2.19 (1.15) |

| Hispanic M (SD) | 1.91 (1.01) | 1.91 (1.05) | 2.56 (1.30) | 3.44 (1.34) | 2.13 (1.03) | 2.38 (1.25) |

| Black M (SD) | 1.90 (1.02) | 1.85 (1.00) | 2.34 (1.27) | 2.93 (1.42) | 1.91 (0.98) | 2.17 (1.14) |

| Asian M (SD) | 2.06 (0.97) | 2.02 (1.00) | 2.47 (1.17) | 3.16 (1.27) | 2.21 (1.01) | 2.67 (1.25) |

| Comparisons | ||||||

| White vs. Hispanic d | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.12 | −0.01 | −0.15* | −0.16* |

| White vs. Black d | 0.00 | 0.08 | 0.29*** | 0.37*** | 0.07 | 0.02 |

| White vs. Asian d | −0.15** | −0.09 | 0.19*** | 0.20*** | −0.24*** | −0.41*** |

| Hispanic vs. Black d | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.17* | 0.37*** | 0.22** | 0.18* |

| Hispanic vs. Asian d | −0.15 | −0.11 | 0.07 | 0.22* | −0.08 | −0.23** |

| Black vs. Asian d | −0.16* | −0.17* | −0.11 | −0.17* | −0.30*** | −0.42*** |

Note.

p < .001,

p < .01,

p < .05.

Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) for each group are presented. Effect size d and statistical significance for differences between each group are shown. A positive effect size indicates that the first group listed scored higher than the second group (e.g., Hispanic women reported higher body surveillance than Black women, d = 0.24). A negative effect size indicates that the first group listed scored lower than the second group (e.g., White women reported lower overall body surveillance than Hispanic women, d = − 0.17).

Fig. 1.

The percentage of men and women reporting high sociocultural appearance pressures by BMI, Note. The darker lines represent women and the lighter lines represent men. Only cells with at least 20 participants are plotted. BMI was strongly associated with likelihood of reporting high pressures (3.26–5.00 on Likert scale).

3. Results

3.1. Goal 1: gender differences in sociocultural appearance concerns

We hypothesized that more women than men would report body surveillance, thin-ideal internalization, and pressures from peers, media, and family. In contrast, more men than women would report muscularity and athletic internalization.

Consistent with the hypothesis, in regression analyses comparing men and women, women reported higher body surveillance (β = .41), higher thin ideal internalization (β = 0.29), lower muscular/athleticism internalization (β = −.60), and higher perceived pressures from media (β = .53) and family (β = .23), when other predictor variables were in the model (Table 2a).

Looking at the gender differences without demographic controls, women reported higher body surveillance (d = − 0.37), thin-ideal internalization (d = − 0.24), media and parental pressures (d = − 0.54 and − 0.19, respectively), and lower muscle/athletic internalization (d = 0.69; Table 3). Fewer men than women reported high body surveillance (26% vs. 41%) and thin-ideal internalization (28% vs. 41%), whereas more men than women reported high muscle/athletic internalization (47% vs. 22%). Regarding appearance pressures, the most common form of pressure reported by men and women were media pressures (35% vs. 60%), followed by parental pressures (11% vs. 20%) and peer pressures (11% vs. 12%).

Individual items of interest also showed notable differences between men and women. In the regression analyses, gender differences in all examined items were greater than βs = 0.20, except for “I want my body to look very lean” item (β = .14; Table 2b). As shown on Table 3, the mean sex difference for seven out of nine items on the body surveillance scale exceeded d = |0.20|. Every item on the thin-ideal specific items was in the direction of women endorsing an the thin ideal more strongly than men, but only one comparison exceeded d = |0.20|: “I want body to look very thin” (d = − 0.30).

In direct contrast to the findings for thinness, men showed greater internalization of muscle/athletic ideals. Every item on the muscle/athletic specific items was in the direction of men reporting a more negative effect on body image than women, with the effect sizes moderate-to-large in size (ds = 0.49–0.81).

3.2. Goal 2: sexual orientation differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

We hypothesized that gay men and bisexual men would experience greater sociocultural appearance concerns than heterosexual men. We tentatively hypothesized that heterosexual women would experience greater concerns than lesbian women.

Consistent with the hypothesis, gay men systematically reported heightened sociocultural appearance pressures compared to heterosexual men on most variables (Tables 2a and 2b). In regression analyses, gay men reported higher body surveillance (β = 0.53) and thin-ideal internalization (β = 0.33), peer pressures (β = 0.19), media pressures (β = 0.57), and leanness cognitions (β = 0.21). Compared to gay men, heterosexual men engaged in fewer social comparisons (β = − 0.42), less self-objectification (β = − 0.36), and less monitoring (β = − 0.36).

Gay men did not differ from heterosexual men in perceived family pressures (β = 0.01) or athletic behaviors (β = − 0.06). Additionally, the one area where gay men reported less internalization than heterosexual men was in muscle/athletic internalization (β = − 0.23). Looking at specific items (Table 2b), gay men reported fewer including athletic cognitions (β = − 0.24) but did not differ from heterosexual men in athletic behaviors (β = − 0.06). Differences between heterosexual and bisexual men were less consistent: the only difference exceeding β = |.19| was that bisexual men reported lower muscle/athletic internalization.

Consistent with the hypothesis, lesbian women reported lower body surveillance (β = − 0.43), thin-ideal internalization (β = − 0.20), perceived media pressures (β = − 0.17), less social comparison (β = 0.41), less self-objectification (β = 0.33), and less monitoring (β = 0.25). Lesbian women, however, did report greater muscle internalization (β = 0.18) and athletic cognition (β = 0.15). They did not differ in peer pressures (β = − 0.05), family pressures (β = − 0.06), leanness cognitions (β = − 0.11), or athletic behaviors (β = 0.04). Differences between heterosexual and bisexual women were less consistent, with no differences exceeding β = |.20|.

The links between sexual orientation and body surveillance, internalization, and pressures are shown in Table 4. Compared to other men (heterosexual, bisexual, other), gay men were more likely to be high in body surveillance (49% vs. 24–31%), thin-ideal internalization (41% vs. 28–34%), media pressures (58% vs. 34–43%), social comparison (64% vs. 44–45%), self-objectification (40% vs. 23–24%), and monitoring (58% vs. 42–48% in other groups).

Compared to other women, lesbian women were least likely to be high in body surveillance (27% vs. 34–49%), social comparison (42% vs. 57–65%), and monitoring (47% vs. 52–61%). On self-objectification, lesbian women were less likely to report high levels (26%) than heterosexual (36%) and bisexual women (41%), but not other orientation women (21%). Lesbian women were somewhat more likely to be higher in muscle/athletic internalization (30% vs. 20–24%).

3.3. Goal 3: racial group differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

We hypothesized that Black women experience fewer sociocultural appearance concerns than other women and that Black men experience greater muscle/athletic internalization than other men. We expected that Hispanic women might report lower thin-ideal internalization that White women. Asian men and women were hypothesized to experience greater perceived family pressures. The remaining comparisons were exploratory.

Consistent with the hypothesis, compared to White women in regression analyses, Black women reported lower body surveillance (β = − 0.14), thin-ideal internalization (β = − 0.48), muscle/athletic internalization (β = − 0.19), peer pressures (β = − 0.17), media pressures (β = − 0.33), and family pressures (β = − 0.12), although not all effect sizes exceeded (β = |.20|). Also consistent with the hypothesis, greater family pressures were reported more so by Asian women than White women (β = 0.59) and by Asian men than White men (β = 0.33).

Looking across all of the other results, the only other associations exceeding β = 0.19 were that Black men were less likely than White men to report thin-ideal internalization (β = − 0.25) and media pressures (β = − 0.28), but were more likely to report muscle/athletic internalization (β = 0.33).

Comparing all racial groups without controls, almost all effect sizes were less than d = |0.30| (Table 5a). All instances of larger effect sizes tended to included comparisons of Black women with other groups, except that White women reported fewer family pressures than Asian women (d = − 0.41). Looking at men, the only effects meeting or exceeding d = |0.30| were that Black men reported fewer family pressures than Asian men, fewer media pressures than Hispanic men, less muscle/athletic internalization than White men, and less thin-ideal internalization than Asian men.

These patterns can be seen in the frequency of high sociocultural appearance concerns across the groups. Fewer Black women were high in thin-ideal internalization (28%) compared to women in other racial groups (43–45%). Black women (45%) were less likely to report high media pressures than other groups (53–61%). Also notable was the fact that more Asian women (32%) reported high family pressures compared to the other groups (18–25%). Fewer Black men (20%) were high in thin-ideal internalization, compared to men in other racial groups (28–32%), and Black men (50%) were more likely to report sending time doing things to become more muscular than other groups (33–43%).

3.4. Goal 4: age differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

We hypothesized that older men and women experience relatively fewer sociocultural appearance concerns than younger men and women. Consistent with the hypothesis, in regression analyses, older men and women reported lower body surveillance, thin ideal internalization, muscular/athleticism internalization, and perceived pressures from peers, media, and family, with most effect sizes around β = |.20|(βs = − 0.15 to − 0.24; Table 2a). The exception was for media pressures, which was only weakly associated to age for men (β = − 0.08).

These age differences could also be seen on individual items. Looking at the specific individual items of interest on the body surveillance and internalization scales, older men and women reported these cognitions less often (β = − 0.11 to − 0.22), although associations were generally below β = |.20| (Table 2b).

These links between age categories and sociocultural appearance pressures are shown in Table 4. Younger adults were much more likely to report these concerns than older adults. For example, 18–24 year old men than 50–65 year old men to report high body surveillance (31% vs. 12%), thin-ideal internalization (31% vs. 20%), muscle/athletic internalization (59% vs. 25%), peer pressure (16% vs. 3%), and family pressure (14% vs. 5%). These patterns can also be seen among women, where 18–24 year old women were more likely than 50–65 year old women to report high body surveillance (48% vs. 25%), thin-ideal internalization (52% vs. 33%), muscle/athletic internalization (30% vs. 11%), peer pressure (19% vs. 7%), and family pressure (26% vs. 14%).

Consistent with the weaker associations between age and media pressures in the regression analyses, 32% of 50–65 year old men and 34% of 18–24 year old reported high media pressure, as did 54% of 50–65 year old women and 63% of 18–24 year old women.

3.5. Goal 5: body mass differences in sociocultural appearance concerns among men and women

We hypothesized that men and women with higher BMIs experience greater sociocultural appearance concerns, and that there would be a curvilinear association for men.

Consistent with the hypothesis, for both men and women, having higher body masses was linked to greater peer, media, and family pressures. All of these associations had βs > |.20| for men (0.23–0.29) and women (0.33–0.45). For both men and women, associations were weaker for the links between BMI and body surveillance (β = .11 men vs. .15 women), thin-ideal internalization (β = .17 vs. .12), and muscle/athletic internalization (β = .03, − 0.09). No associations among BMI2 to any of the outcome measures exceeded β = |.10| (Table 2a and 2b).

The associations between BMI and high media, peer, and family pressures are visually represented in Fig. 1. BMI was associated with likelihood of reporting high (3.26–5.00) media, family, and peer appearance pressures. High media pressure was reported by over one-third of women with BMIs greater than 17 and men with BMIs greater 27. Higher BMI was associated with higher media pressure until BMI of 40, when the association plateaus, indicating a curvilinear relationship in both men and women. In contrast, fewer than one-third of men and women reported high peer pressures across the entire BMI range. High family pressure was reported by over one-third of women with BMIs over 36, whereas high family pressure never exceeded one-third for men.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of key findings

The current study provided the rare opportunity to examine demographic differences in sociocultural appearance concerns in a large national sample. The findings point to important results on groups at greater risk for developing these concerns. The study provides evidence resonant with distinct theoretical claims and debates in the literature. Furthermore, the findings highlight the value of examining individual items in addition to overall scale means for generating new knowledge. We address these findings below.

4.1.1. Body surveillance and thin-ideal internalization

Consistent with the proposal that women are presented with stronger social pressures to be slender and to emphasize their appearance (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997), women were more likely than men to report body surveillance and thin-ideal internalization. These differences also emerged on items assessing social comparison, body surveillance, appearance monitoring, and leanness cognitions. Looking across sexual orientations, these pressures were felt more acutely by gay men than heterosexual men, and more so by heterosexual women than by lesbian women. These findings are consistent with the view that people who seek men as long-term partners are more likely to face pressures to be good-looking (Buss, 1989; Fales et al., 2016), and as a result experience increased objectification and pressure to be slender.

Some researchers have proposed that as people age, they face less societal objectification and less pressure to meet appearance ideals (Tiggemann & Lynch, 2001). As people age, they draw on a broader range of social roles to determine their self-worth (Greenleaf, 2005). Consistent with this view, older men and women were generally less likely to report body surveillance, and also reported lower thin-ideal internalization, although all effect sizes were not large. It is important to note that appearance-related concerns linked to objectification vs. function can change in ways that were not measured in the current study. For example, some older women envy the ability of younger women to do more with their bodies physically as well as their appearance, and express concerns about how much attention or respect they receive because of their appearance (Runfola et al., 2013).

Many people in our study, regardless of their current weight, endorsed the thin-ideal. This finding is consistent with research showing thinness in women is widely valued across industrialized countries and locales (Swami et al., 2010). Across BMI groups, many women and men wanted their body to look “very lean.” It is notable that men and women with higher BMIs were most likely to report these cognitions. This means that many heavier men and women are facing a situation where the body type they idealize is markedly discrepant from their current appearance, which likely fosters greater body dissatisfaction. The combination of body surveillance and thin-ideal body surveillance could also promote increased stress and awareness of weight stigma for heavier men and women. This, in turn, may portend greater weight gain, which gives way to greater stress, body surveillance, and stigma, leading to further weight gain (Tomiyama, 2014).

4.1.2. Muscle/athletic internalization

A great deal of emphasis has been placed on the cultural models promoting muscularity for men (Frederick et al., 2005), including the fact that many women find muscular and toned male body types attractive (Frederick & Haselton, 2007; Gray & Frederick, 2012; Sell et al., 2017). Consistent with these pressures, men reported greater muscle/athletic internalization than women and the effect size was large. Looking across each of the individual cognition and behavior items for athleticism and muscularity, all effect sizes for gender differences were moderate to large. Looking at how the effect sizes vary by item in this measures, it strikes us that additional work is needed to effectively theorize and measure (a) internalization of different types of athletic/muscular ideals, such as athletic appearance vs. muscle tone vs. muscle size vs. muscle function vs. athleticism ideals; (b) satisfaction with each of these ideals; (c) behaviors related to each ideal; and (d) how these concerns likely vary according to body area (e.g., chest vs. stomach vs. legs vs. arms) differently across individuals and across the sexes.