Abstract

Squamous cell carcinomas are triggered by marked elevation of RAS–MAPK signalling and progression from benign papilloma to invasive malignancy1–4. At tumour–stromal interfaces, a subset of tumour-initiating progenitors, the cancer stem cells, obtain increased resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy along this pathway5,6. The distribution and changes in cancer stem cells during progression from a benign state to invasive squamous cell carcinoma remain unclear. Here we show in mice that, after oncogenic RAS activation, cancer stem cells rewire their gene expression program and trigger self-propelling, aberrant signalling crosstalk with their tissue microenvironment that drives their malignant progression. The non-genetic, dynamic cascade of intercellular exchanges involves downstream pathways that are often mutated in advanced metastatic squamous cell carcinomas with high mutational burden7. Coupling our clonal skin HRASG12V mouse model with single-cell transcriptomics, chromatin landscaping, lentiviral reporters and lineage tracing, we show that aberrant crosstalk between cancer stem cells and their microenvironment triggers angiogenesis and TGFβ signalling, creating conditions that are conducive for hijacking leptin and leptin receptor signalling, which in turn launches downstream phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K)–AKT–mTOR signalling during the benign-to-malignant transition. By functionally examining each step in this pathway, we reveal how dynamic temporal crosstalk with the microenvironment orchestrated by the stem cells profoundly fuels this path to malignancy. These insights suggest broad implications for cancer therapeutics.

Subject terms: Cancer microenvironment, Tumour angiogenesis, Cancer stem cells, Squamous cell carcinoma, Cell signalling

Aberrant crosstalk between cancer stem cells and their microenvironment triggers angiogenesis and TGFβ signalling, creating conditions that are conducive for hijacking leptin and leptin receptor signalling, which in turn launches downstream PI3K–AKT–mTOR signalling during the benign-to-malignant transition.

Main

Squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are common life-threatening cancers of the stratified epithelia of skin, oral cavity, oesophagus and lungs1,8,9. Even for skin, where SCCs are often caught early, their frequency of occurrence and ever-rising metastatic incidences pose major health concerns10. Chemical carcinogenesis studies expose elevated RAS–MAPK signalling, often involving oncogenic Ras mutations, as critical in the path to invasive SCCs2–4. The lengthy delay and sporadic nature of mutagen-mediated SCCs has led to the view that additional oncogenic mutations are needed3,11–13, further supported by the high mutational burden associated with human metastatic SCCs7. However, genetically induced SCCs display many fewer mutations than mutagen-driven SCCs3,14, and skin tumours exhibiting a heterogeneous benign/SCC phenotype can be initiated even with HRASG12V alone6. These observations raise the possibility that non-genetic alterations may be potent cancer drivers.

Increasing evidence has highlighted extrinsic perturbations—for example, inflammation, metabolism and wounding—in preconditioning tissues to heightened cancer vulnerabilities6,14–19. It is less clear whether and how in healthy tissues an oncogenic mutation in a stem cell can intrinsically stimulate environmental changes that may lessen the need for multi-step mutagenesis. Here we address this issue using a single HRASG12V oncogene model that clonally activates a reliable path to aggressive, invasive cutaneous SCCs. After performing deep single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) to gain insights into the SCC cancer stem cell (CSC) signature, we trace its temporal origins and physiological importance. We show that, after oncogenic RAS initiation, tissue stem cells begin an aberrant molecular dialogue with their surroundings, culminating in a considerable remodelling of the tumour microenvironment at the benign-to-malignant transition. This provides fertile ground for stromal TGFβ-mediated induction of leptin receptor (Lepr) and vasculature-mediated elevation of tissue leptin, leading to LEPR–leptin signalling and PI3K–AKT–mTOR in CSCs to drive the invasive switch. Triggered by oncogenic RAS, each step of this stem cell–microenvironment crosstalk cascade is essential for malignant progression, and it involves pathways that are often mutated in advanced SCCs with a high mutational burden.

Newfound heterogeneity in CSCs

Skin stem cells that acquire HRAS mutations go through a benign papilloma state before progressing to malignant, invasive SCCs20,21. On the basis of serial transplantations, tumour-initiating CSCs from mouse SCCs are enriched for integrins and reside at tumour-stromal interfaces22,23. In tumours displaying a mixed phenotype, basal progenitors undergoing TGFβ signalling are enriched for CSCs with increased resistance to chemotherapy and immunotherapy, and the loss of TGFβ signalling reverts tumours to a benign state5,6,19.

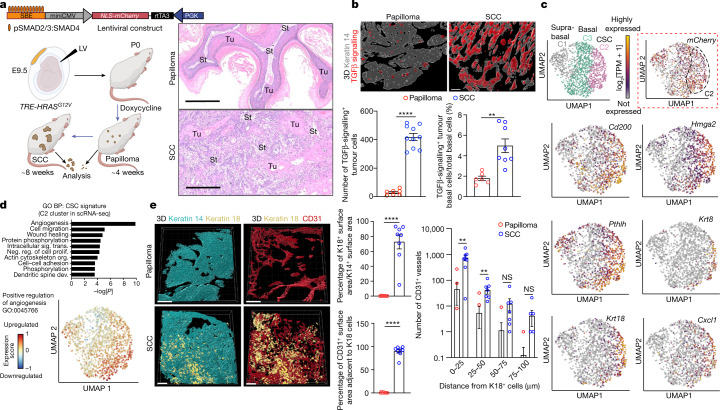

To control tumorigenesis, we took embryonic day 9.5 (E9.5) FVB mouse embryos with a tetracycline-inducible RAS oncogene (TRE-HRASG12V) and performed low-titre in utero lentiviral delivery to selectively transduce a small number of skin basal progenitors with an rtTA3 transactivator and TGFβ reporter under the control of pSMAD2/3–SMAD4-complex-binding elements (SBE) (Fig. 1a). Postnatal doxycycline resulted in clonally transduced skin patches of activated HRAS(G12V). By around 4 weeks, hyperplastic, well-differentiated benign papillomas with smooth undulating epithelial–mesenchymal borders had formed, of which most advanced to undifferentiated, uniformly invasive SCCs by about 8 weeks (Fig. 1a). SCCs displayed only sparse differentiated keratin pearls, while most epithelial–stromal borders were poorly defined. As judged by immunofluorescence imaging and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), TGFβ signalling and the phosphorylation of its downstream target transcriptional cofactor SMAD2 (pSMAD2) were rare in papillomas but increased substantially in invasive SCC progenitors (Fig. 1b and Extended Data Fig. 1a,b). Taken together with our previous analysis of mixed papilloma–SCC tumours6, this result provided an important temporal layer by linking TGFβ signalling to the progression of CSCs from benign to malignant states.

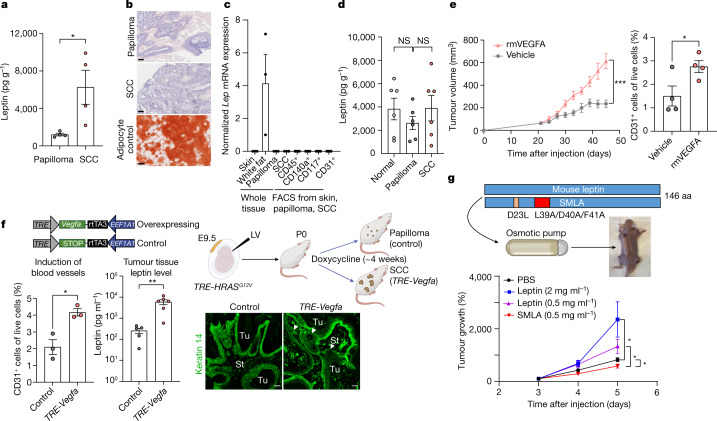

Fig. 1. Benign-to-invasive rewiring of the tumour-initiating CSC transcriptome fuels angiogenesis.

a, The tumour model. Lentivirus containing a TGFβ mCherry reporter and transactivator rtTA3 was injected at a low titre in utero into the amniotic sacs of E9.5 TRE-HRASG12V mouse embryos to sparsely transduce individual skin progenitors. Postnatally, doxycycline activates rtTA3 and induces HRASG12V in these stem cells. Haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining reveals temporally distinct pathologies of benign and malignant SCCs. Tu, tumour; St, stroma. Scale bars, 300 µm. b, Quantification of a collapsed z-stack of 3D whole-mount immunofluorescence images and FACS-purified mCherry+ITGA6high basal progenitors reveals increased TGFβ signalling as tumours progress to invasive SCCs (Extended Data Fig. 1b). Bottom left: n = 7 (papilloma) and n = 10 (SCC); bottom right: n = 6 (papilloma) and n = 8 (SCC) tumours per stage. P < 0.0001 (left) and P = 0.0018 (right). Scale bars, 50 µm. c, UMAP representations and unsupervised k-nearest-neighbour-based clustering of single-cell transcriptomes performed on pooled FACS-isolated integrinlow (spiked, 159 total suprabasal) and integrinhigh (bulk, 1,346 total basal) cells from invasive SCC tumours. Clusters C2 and C3, basal progenitors; C1, suprabasal cells. Note that mCherry (TGFβ reporter, dotted box) is enriched in, but not exclusive to, C2 (35.8% of all basal cell progenitors). C2 is enriched for markers of SCC-CSCs with tumour-initiating and invasive properties. The UMAP plots show the relative expression levels (log2[TPM + 1]) of these genes across single cells. See also Extended Data Fig. 1g. d, Angiogenesis is the top GO biological process (BP) term of C2 CSC transcripts (UMAP displays clustering). P values were calculated using DAVID bioinformatic analysis. See also Extended Data Fig. 3. Dev., development; neg. reg., negative regulation; org., organization; prolif., proliferation; sig. trans., signal transduction. e, 3D collapsed whole-mount immunofluorescence images of the invasive fronts of tissue sections. Keratin 18 (K18) identifies CSCs; CD31 identifies vasculature. Scale bars, 150 µm. Quantifications are of keratin 18+ cell abundance, proximity to vessels and distances with vessels. n = 8 (top middle), n = 8 (bottom middle) and n = 8 (right) tumours per condition per stage. P < 0.0001 (top and bottom middle); and P0–25 = 0.0020, P25–50 = 0.0176, P50–75 = 0.1337, P75–100 = 0.1358. For b and e, statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests; NS, P ≥ 0.05; *P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01, ***P ≤ 0.001, ****P ≤ 0.0001. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (b and e). See also Supplementary Tables 1–3. The diagram in a was created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 1. Benign papillomas and invasive SCCs exhibit distinct molecular signatures for angiogenesis and TGFβ responsiveness.

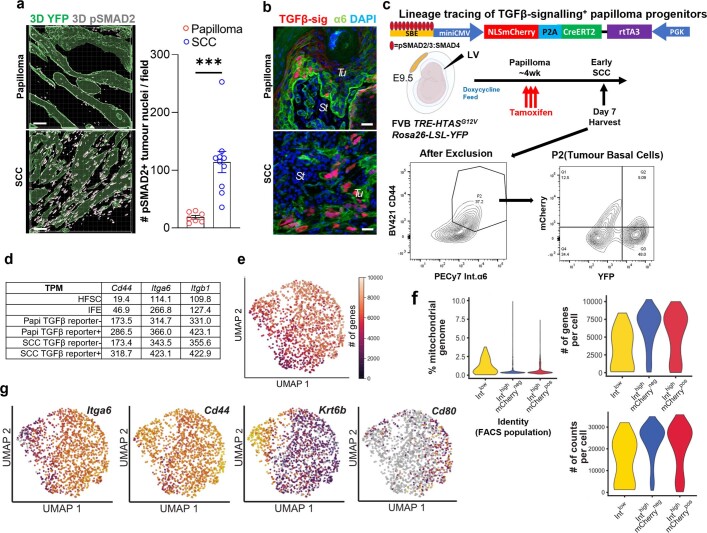

a, Collapsed z-stack rendering of 3D whole mount immunofluorescence for nuclear pSMAD2. Scale bars, 50 µm. (n = 8 tumours per stage, p = 0.0007). b, Immunofluorescence of sagittal tumour sections for TGFβ reporter (mCherry) signalling, α6 integrin to demarcate the tumour-stromal border and DAPI (nuclei). Note elevated mCherry at invasive fronts of the SCC (see Fig. 1b for quantifications). c, Lineage tracing of TGFβ-signalling tumour cells marked at the papilloma stage, traced to the SCC and analysed by FACS shows that TGFβ-responding papilloma cells contribute significantly to SCC tumour progression. d, Transcript levels of Itga6, Itgb1 and Cd44 are increased from normal skin to papilloma and SCC. e, UMAP of the number of genes per cell. f, Violin plots showing that the quality of samples (with FACS labelled cell identities) in the scRNAseq was high as judged by the number of counts per cell, the number of genes per cell, and the low percentage of the mitochondrial genome captured. g, UMAPs of control genes for basal SCC cells (Itga6, Cd44), suprabasal tumour cells (Krt6b) and SCC-CSCs (Cd80) (see Fig. 1c for additional details). All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. The diagram in c was created using BioRender.

Investigating deeper into the physiological relevance of this temporal change, we added a creERT2 transgene under the control of the SBE-driven reporter and, on the basis of tamoxifen-activated lineage-tracing, we found that, even though the TGFβ-reporter-positive cells were infrequent in papillomas, they contributed substantially to SCCs (Extended Data Fig. 1c). To further dissect the differences, we performed scRNA-seq Smart-seq2 analysis of histologically prevalidated, uniformly invasive SCCs of which the progenitors had been enriched by FACS (Extended Data Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 3). Quality controls revealed sufficient transcriptome detection rates, with ~7,500 genes per cell and low mitochondrial gene contamination (Extended Data Fig. 1e,f).

Transcriptomes fell into three clusters: C1, Itga6lowItgb1lowCd44+ suprabasal cells that had been added as a reference and displayed SCC differentiation markers such as Krt6b; and C2 and C3 basal cells, both of which were Itga6highItgb1highCd44+ and were expressed at higher levels than normal skin stem cells (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1g). Despite morphological uniformity, transcriptional heterogeneity emerged within the basal population of advanced SCCs that had not been previously recognized. This was exemplified by TGFβ-reporter-positive (nuclear mCherry) progenitors that, although found at invasive fronts of mixed tumours6, still showed heterogeneity among invasive SCCs, with 57% of C2 cells positive for mCherry transcript compared with 35% of C3 cells (Fig. 1c, dotted box). Thus, although enriched for TGFβ signalling, C2 cells were not defined solely by this marker.

Shifting stem cell–microenvironment crosstalk

Cluster C2 was enriched for Cd200, Hmga2 and Pthlh, which were previously shown to typify SCC progenitors enriched for tumour-initiating CSCs6. However, this cluster also displayed many other transcripts that are not clearly aligned with previous SCC-CSC signatures (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig. 1g). Of 1,894 transcripts enriched in basal SCC cells relative to differentiated tumour cells, 732 were specific to C2 (Supplementary Table 1).

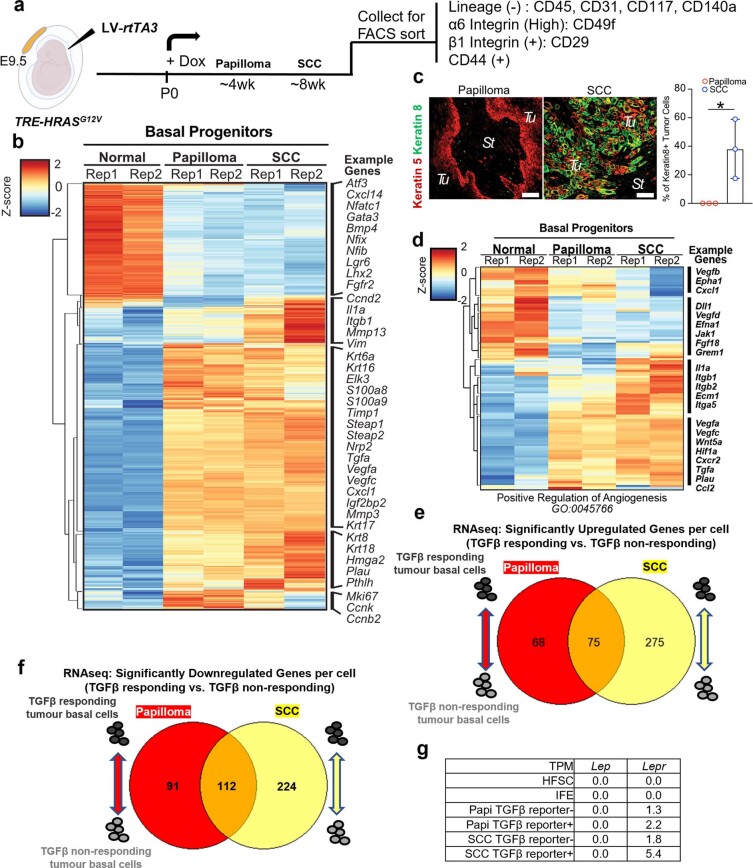

To place our CSC signature in the context of tumour progression, we performed bulk RNA-seq analysis of FACS-purified basal progenitors from normal skin, papillomas and SCCs, each staged temporally and histologically before processing (Extended Data Fig. 2a,b and Supplementary Fig. 4). Relative to their normal skin counterparts, pan-tumour basal cells upregulated 886 transcripts by at least twofold (adjusted P ≤ 0.05; Supplementary Table 2), whereas 562 transcripts were upregulated specifically during the transition from benign to malignant states (Supplementary Table 3). Although a number of C2 transcripts were found in papillomas, many were induced in SCCs, as exemplified by Krt8 and Krt18 transcripts and substantiated by immunofluorescence analysis (Extended Data Fig. 2b,c).

Extended Data Fig. 2. FACS-isolation and transcriptomic analysis of basal progenitors from normal skin, benign papilloma and SCC.

a, Experimental design for the tumour model as in Fig. 1a, used to purify basal progenitors from papillomas and SCCs. Basal cells (n = 2 mice per condition) are isolated by FACS using tumour basal cell markers (ITGA6, ITGB1, and CD44) with non-epithelial cell types (CD31, endothelial cells; CD45 pan-immune cells; CD117, melanocytes; CD140a, mesenchymal cells) excluded. b, Heatmap representation of bulk RNAseq of FACS-isolated basal progenitors from normal skin epithelia, papilloma, and SCC (in replicate) show significant molecular changes and stage-specific signatures during tumour progression. c, Immunofluorescence images show that keratin 8 positive tumour cells, as a proxy for the C2 SCC cancer-stem cell signature, are rare in the papilloma stage and much enriched in the invasive SCC stage. (n = 3 tumours per stage, p = 0.0334). Tu, tumour; St, stroma. Scale bars,50 µm. d, Heat map of the angiogenesis GO-Term. Note: RNAseq in Extended Data Fig. 2b and d, Rep1 SCC displayed mixed SCC-papilloma features. e, For high throughput RNA sequencing, two independent replicates of four FACS isolated populations were used. Venn diagram shows the differential expression of genes (DEG) analysis of RNAseq data from TGFβ responding tumour basal cells over their non-responding neighbours and compared between papilloma and SCC. DEG analysis yielded 68 TGFβ responding upregulated genes unique to the papilloma stage, 275 TGFβ responding upregulated genes unique to the SCC stage, and 75 upregulated genes shared by both stages. f, DEG analysis yielded 91 TGFβ responding downregulated genes unique to the papilloma stage, 224 TGFβ responding downregulated genes unique to the SCC stage, and 112 downregulated genes shared by both stages. g, Transcript levels of Lep are below the limits of detection in papillomas and SCCs. And Lepr are also not expressed in normal skin SCs. All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test: ns, p ≥ 0.05; *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

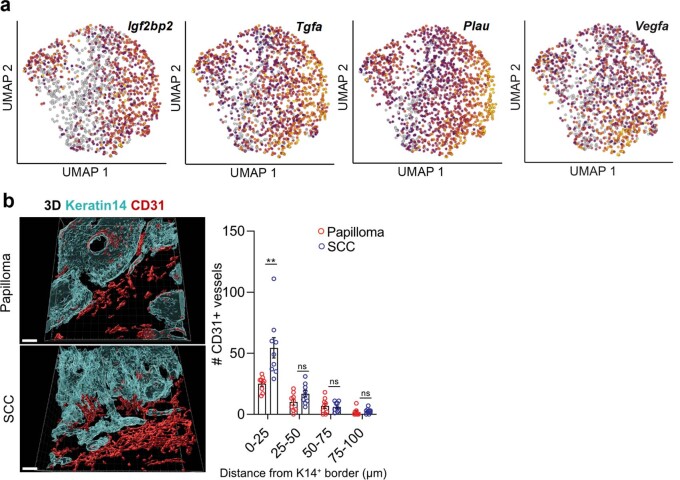

Further insights into the unique features of tumour-initiating CSCs were revealed by the Gene Ontology (GO) terms of the C2 cluster. Angiogenesis appeared at the top of this list, along with cell migration, wound healing, protein phosphorylation and intracellular signalling (Fig. 1d). Uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plots highlighted the enrichment of angiogenesis genes in this cluster, many of which were upregulated during the benign–malignant transition (Extended Data Fig. 2d). Consistent with the preponderance of secreted angiogenic factors, reconstructed 3D immunofluorescence images revealed a significant influx in CD31+ vasculature specifically at the benign-to-invasive SCC transition (Extended Data Fig. 3a,b). This correlation between C2 cells, invasive SCC fronts and enrichment in angiogenesis was further validated by co-immunolabelling for C2 marker keratin 18 and quantification of CD31+ vascular cells (Fig. 1e).

Extended Data Fig. 3. Increased angiogenesis during progression from papilloma to SCC.

a, UMAP of the examples of angiogenesis-associated mRNAs from scRNA analyses of SCCs that show enrichment in the C2 signature (see Fig. 1c for annotation of clusters). b, Collapsed z-stack rendering of clearing and whole-mount immunofluorescence of tissue sections (n > 8 tumours per stage). Keratin 14 labels the tumour epithelium; CD31 labels the vasculature. Quantifications are at right. Note that the blood vessel proximity is closer in invasive SCC than papilloma. Scale bars, 40 µm. (n = 8 tumours per condition per stage, p(0–25) = 0.0034, p(25–50) = 0.0801, p(50–75) = 0.7548, p(75–100) = 0.4734). All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Overall, whereas previous studies reported an increase in vasculature during the transition from normal skin stem cells to papillomas24, here we found a notable further increase in the vasculature specifically during the progression to SCCs. This elevation appeared concomitantly with SCC-CSCs and TGFβ signalling, suggesting that these features were functionally intertwined. Further support came from RNA-seq and differential gene expression analysis of FACS-purified papilloma versus SCC progenitors fractionated according to TGFβ reporter activity. Despite their temporal lineage relationship, TGFβ-responding basal SCC cells differed from those of papillomas (Extended Data Fig. 2e,f). These data suggest that progenitors that progress to SCC are influenced by shifting crosstalk with their tumour microenvironment.

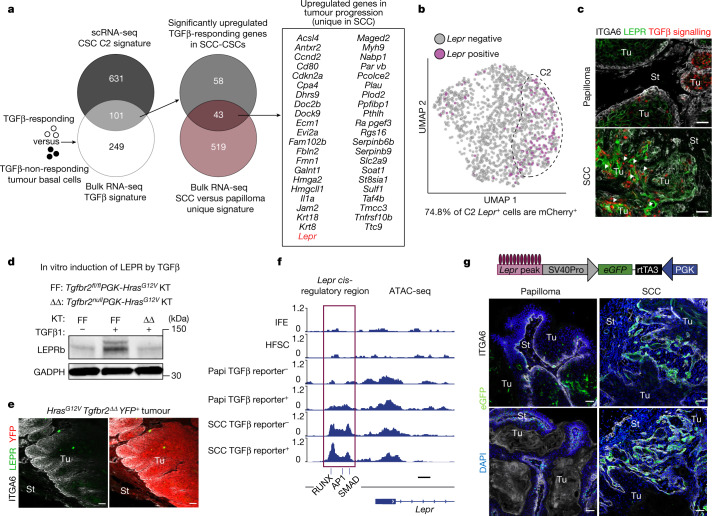

When C2 cells were specifically scored for elevated TGFβ signalling, 101 associated transcripts were also upregulated (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 4). In addition to Cd80—a factor in resisting immunotherapy5—this shortlist included Ccnd1 and Ccnd2, Hmga2, Pcolce2, Rgs16, St8sia1, Tnfaip2 and Pthlh, which are known to correlate with stem cell self-renewal/survival, proliferation and/or poor prognosis in SCCs. The list also included Krt8, Krt18, Mmp14 and Mmp1a, which are implicated in basement membrane remodelling, cytoskeletal dynamics and/or migration/metastasis. Genes encoding angiogenic factors also remained on this list, consistent with active TGFβ emanating from perivascular immune and other stromal cells near invasive fronts6,19.

Fig. 2. Leptin receptor is a TGFβ-regulated gene induced in tumour-initiating CSCs and localized to invasive SCC fronts.

a, Venn diagram showing that 101 genes constitute a refined CSC signature shared by single-cell C2 and TGFβ-responsive transcriptomes in SCC basal progenitors (Extended Data Fig. 2). Of the 101 genes, the 43 listed overlap and are upregulated in the papilloma-to-SCC transition. b, Lepr-expressing cells reside within the C2 basal SCC population and overlap around 75% with TGFβ-reporter+ cells. c, Immunofluorescence analysis of primary mouse skin SCC confirms that LEPR is rarely expressed in papillomas but is enriched in TGFβ-reporter+ SCC cells (arrowheads). Scale bars, 50 µm. d, LEPR immunoblot analysis. Cultured HrasG12V keratinocytes (KT) that are wild type (FF) but not mutant (ΔΔ) for the TGFβ receptor gene (Tgfbr2) elevate LEPR substantially in response to active recombinant TGFβ1. GAPDH was used as the loading control. Gel source data are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1a. e, Immunofluorescence analysis of tumour tissue from FR-LSL-HrasG12V;Tgfbr2fl/fl;R26-LSL-YFP mice transduced at a low titre with PGK-creERT2 lentivirus, and treated with tamoxifen to induce YFP(pseudoRed)+ HrasG12VTgfbr2ΔΔ tumorigenesis. The loss of TGFβ signalling results in non-invasive tumours that do not express LEPR. Scale bars, 50 µm. f, ATAC-seq was performed on FACS-purified ITGA6highITGB1high basal populations of interfollicular epidermis (IFE, SCA1+), bulge hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs, CD34+) and tumour cells (CD44high) either positive or negative for TGFβ responsiveness (mCherry). ATAC peaks associated with the Lepr locus opened during tumorigenesis, with the encased cluster 6 peak (containing RUNX, AP1 and SMAD motifs) opening predominantly during SCC progression. Scale bar, 500 bp. Papi, papilloma. See also Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5. g, Schematic of the in vivo Lepr ATAC-peak eGFP reporter assay. Reporter activity is greatly enriched at the benign-to-invasive SCC transition. Scale bars, 50 µm. See also Supplementary Tables 4 and 5.

Notably, 43 out of these 101 genes in the TGFβ-signalling SCC-CSC signature were specifically induced/elevated during the transition to SCC (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 5). As TGFβ-signalling papilloma progenitors lineage traced to SCC-CSCs, these data implied that CSC gene expression is affected by changes in the tumour microenvironment.

Lepr is an unexpected component of the CSC signature

In considering CSC signature proteins that might be able to sense, respond to and take advantage of the notable changes in the tumour microenvironment at the benign–malignant transition, Lepr caught our attention. Traditionally studied in the context of energy balance, LEPR signalling is triggered by its ligand leptin, which is primarily produced by white adipose tissue, but can enter the circulation to reach distal LEPR+ target tissues, such as the hypothalamus25.

Lepr was not expressed in homeostatic skin epithelium and was expressed only rarely in papilloma. Within SCC progenitors, Lepr was specifically transcribed in mCherry+ TGFβ-signalling C2 CSCs (Fig. 2a,b and Extended Data Fig. 2g). LEPR immunofluorescence corroborated its location in invasive mouse SCCs, and was also found human SCC tumours and xenografts (Fig. 2c and Extended Data Fig. 4a).

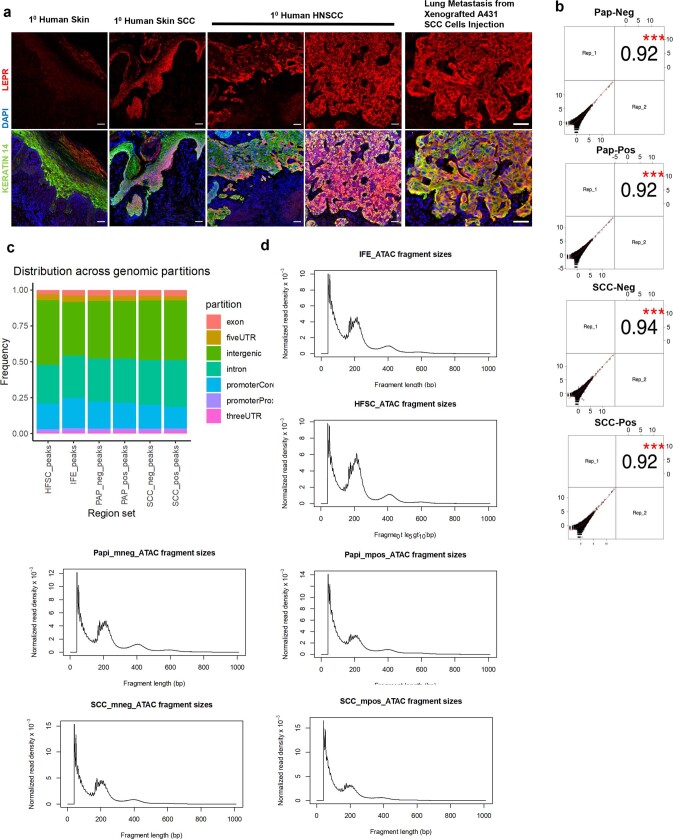

Extended Data Fig. 4. LEPR expression in skin and SCCs from human and quality control for ATAC Sequencing.

a, LEPR immunofluorescence of human normal skin, head and neck SCC (HNSCC), and lung metastases from human SCC A431 epidermal cells following tail-vein injections in immunocompromised mice. Top row: LEPR labelling alone; bottom row: LEPR, Keratin 14 and DAPI. Scale bars,50 µm. b, Correlation plot between ATAC replicates of TGFβ-responding and non-responding SCC and papilloma. All replicates have a correlation coefficiency > 0.92 and p < 0.001 (denoted as ***). The test statistic is based on Pearson’s product moment correlation coefficient and follows a t distribution with n-2 degrees of freedom. c, ATAC peak distribution of all 6 samples according to gene features. All samples display comparable distributions. d, Distribution of tagmented fragments in all ATAC-seq samples. Nucleosome laddering is clear in all samples. All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

To understand the specificity of Lepr to C2 TGFβ-signalling cells, we first exposed cultured isogenic TGFβ receptor floxed and null HrasG12V keratinocytes to recombinant TGFβ1 or vehicle control. Immunoblot analysis underscored the sensitivity of LEPR to TGFβ signalling (Fig. 2d). We further documented this dependency by transducing FR-LSL-HrasG12V;Tgfbr2fl/fl;R26-LSL-YFP mice with a PGK-creERT2 lentivirus, and then administering tamoxifen to simultaneously ablate the TGFβ receptor, induce tumorigenesis and activate lineage tracing. Without TGFβ receptor signalling, which is known to be essential for EMT-mediated invasion6, only a few rare LEPR+ cells were detected by immunofluorescence (Fig. 2e).

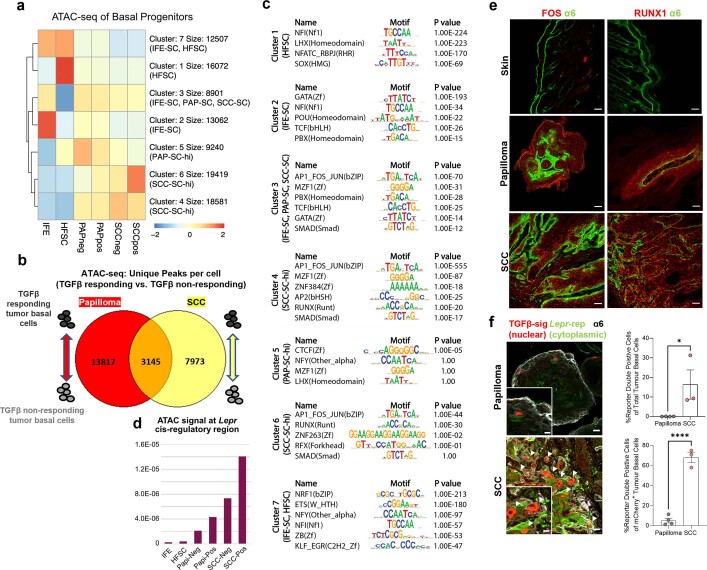

To address whether Lepr is a direct transcriptional target of TGFβ receptor signalling in vivo, we performed an assay for transposase-accessible chromatin with high-throughput sequencing (ATAC-seq) analysis of FACS-purified TGFβ-reporter positive versus negative basal tumour populations (Extended Data Fig. 4b–d). Unsupervised clustering of ATAC profiles from purified progenitors of normal skin (interfollicular epidermis; hair follicle), papilloma and SCC revealed seven clusters (Extended Data Fig. 5a).

Extended Data Fig. 5. Benign papilloma and invasive SCC display distinct epigenetic signatures.

a, ATAC sequencing is performed on FACS-purified α6hiβ1hi basal populations of interfollicular epidermis (IFE, Sca1+), bulge hair follicle stem cells (HFSCs, CD34+), and tumour cells (CD44hi) either positive or negative for TGFβ-responsiveness (mCherry). Peaks are clustered according to their openness in each population by k-mean clustering. b, Venn diagram showing marked divergence of ATAC peaks from TGFβ-responding tumour basal cells and their non-responding neighbours between papilloma and SCC stages (n = 2 for each condition, each stage). c, Motif enrichment analysis of the 7 ATAC peak clusters. d, Quantifications of the Lepr cis-regulatory region boxed in Fig. 2f. e, Immunofluorescence images reveal that transcription factors RUNX1 and FOS are not detected in normal homeostatic skin but are enriched progressively during tumorigenesis. Scale bars, 50 µm. See also pSMAD2 immunofluorescence quantifications in Extended Data Fig. 1a. f, Lepr EGFP reporter and TGFβ mCherry reporter show minimal activity in papillomas but co-localize at the invasive fronts of SCC. Note numerous SCC cells marked by EGFP cytoplasm and mCherry nucleus. Integrin (white) denotes invasive fronts. For the original images, scale bars, 20 μm. For the magnified insets, scale bar, 10 μm. The percentages of reporter double-positive (DP) cells in these invasive regions are significantly higher in SCC than in papilloma. Majority of the TGFβ mCherry reporter+ cells are these DP cells in SCC compared to the ones in papilloma. (n = 4 for papilloma, n = 3 for SCC; top right: p = 0.0477; bottom right: p < 0.0001). All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t -test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Peaks in the proximity of Lepr mostly fell into clusters 4 and 6, of which the chromatin state displayed marked opening during tumorigenesis, particularly in association with TGFβ-signalling CSCs (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 5b,c). Within these two peak clusters, AP1 (FOS–JUN) and RUNX1 motifs were enriched, along with canonical pSMAD2/3-binding motifs (21% of C4; 17% of C6). Notably, Lepr was among the genes bearing such ATAC peaks and of which the accessibility was sensitive to TGFβ signalling and malignant progression (Fig. 2f and Extended Data Fig. 5d).

Notably, RUNX1 has been shown to be critical for tumour initiation26, whereas elevated AP1 (FOS) has been shown to drive basal cell carcinoma to more aggressive SCCs27. Similar to pSMAD2, both RUNX1 and FOS showed marked nuclear localization in SCC basal cells at invasive fronts (Extended Data Figs. 1a,b and 5e). pSMAD2/3, the essential co-partner of active TGFβ signalling, best distinguished invasive SCCs from papillomas, suggesting that RUNX1 and AP1 may prime these chromatin peaks while TGFβ signalling drives their activation.

To directly test whether tumour-stage-specific changes in TGFβ signalling govern the chromatin accessibility and expression of Lepr, we examined the ability of the C6 cis-regulatory element (Fig. 2f, magenta box) to drive temporal activation of an eGFP reporter during tumorigenesis. Interestingly, the Lepr reporter was highly active at invasive SCC fronts where TGFβ signalling is high6, while much lower in papillomas (Fig. 2g). Consistent with this correlation, in utero co-injection of a TGFβ-signalling mCherrynuclear reporter and a Lepr-eGFPcytoplasmic reporter revealed that the highest double-fluorescence positivity was among invasive SCC, and the majority of total TGFβ-signalling cells in these regions were positive for the Lepr-eGFPcytoplasmic reporter in SCC in contrast to papilloma (Extended Data Fig. 5f). These data further underscore the physiological relevance of TGFβ signalling in fuelling the epigenetic dynamics that lead to Lepr promoter activation during the transition from the benign to malignant states.

LEPR functions in malignant progression

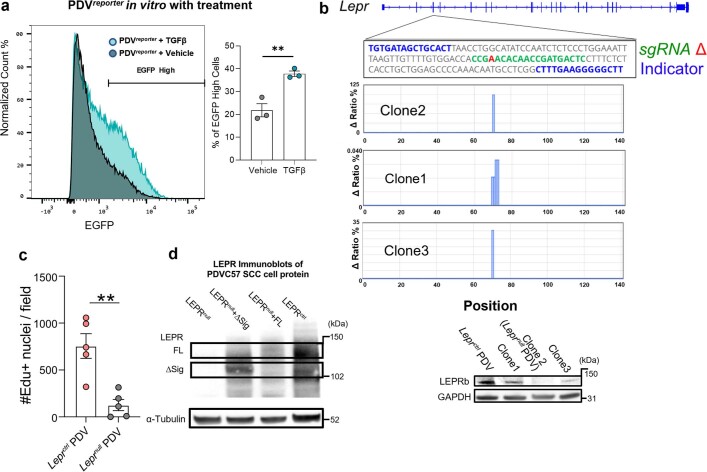

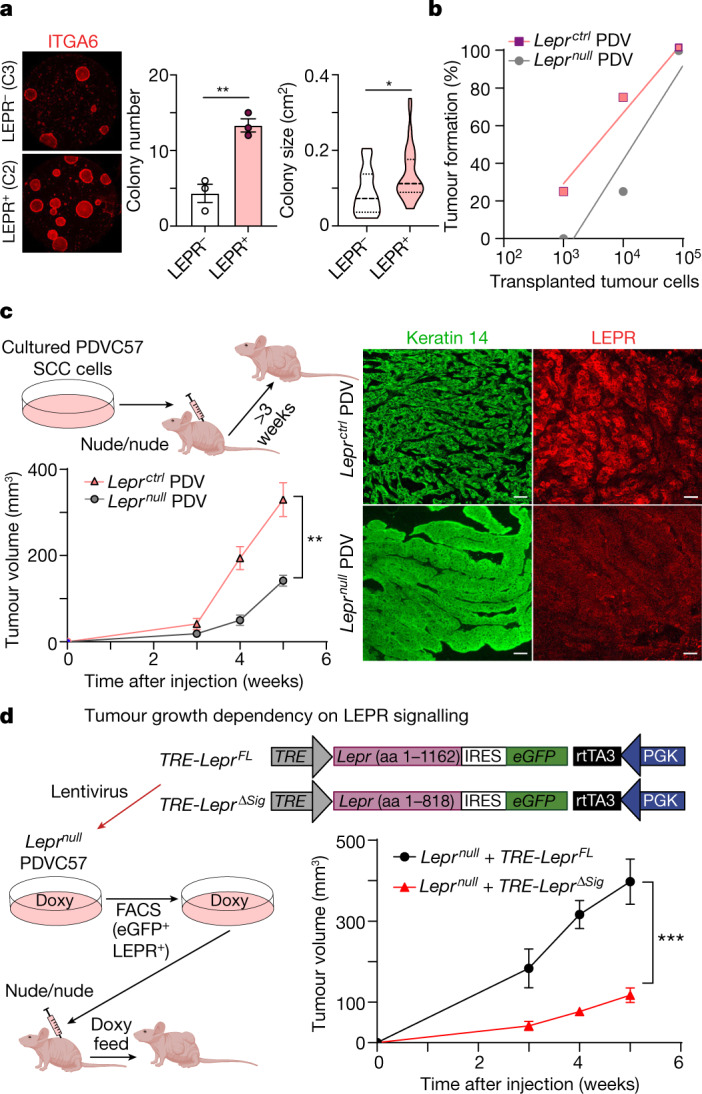

Given the association between Lepr and C2 SCC-CSCs, we next performed colony-forming assays to test for stemness and found that LEPR+ C2 cells showed nearly a threefold higher colony-forming efficiency and formed larger colonies compared with LEPR− C3 cells (Fig. 3a). To functionally test LEPR’s tumour-initiating ability in vivo, we turned to a highly aggressive mouse SCC cell line containing mutations in Hras and Trp5328 (hereafter referred to as PDV). After verifying the TGFβ sensitivity with the Lepr reporter in these cells, we used CRISPR–Cas9 editing to generate a Lepr-null mutation (Extended Data Fig. 6a,b). Serial-dilution orthotopic transplantation assays on Leprnull and Leprctrl PDV cells intradermally injected into immunocompromised Nude mice revealed an approximately 10× higher tumour-initiating ability if LEPR was intact (Fig. 3b). Overall, these results suggested that LEPR identifies a subpopulation of TGFβ-signalling, oncogenic-RAS-driven SCC progenitors endowed with heightened stemness and tumour-initiating ability.

Fig. 3. Leptin receptor promotes superior tumour-initiating ability and is an essential regulator of SCC progression.

a, Stem cell colony assay. When placed in culture, FACS-isolated, LEPR-expressing basal SCC progenitors exhibit higher colony-forming efficiency (n = 3, P = 0.0069) and form larger colonies (n = 13 (LEPR−), n = 39 (LEPR+), P = 0.0106) compared with non-expressing counterparts. Dish diameter, 10 cm. b, Limiting dilution assay. Leprnull PDVC57 (PDV) SCC cells were generated by CRISPR–Cas9 gene editing (Extended Data Fig. 6b). Serial orthotopic transplantation assays reveal that Leprctrl SCC cells possess higher tumour-initiating ability compared with Leprnull SCC cells. n = 4 (105 and 104 cells) and n = 8 (103 cells). c, Leptin receptor deficiency impairs SCC progression. Allografted PDV SCC cells were injected intradermally into immunocompromised Nude mice. Leprnull PDV tumours display reduced growth compared with their control counterparts (n = 4, P = 0.0039 for the end timepoint). Immunofluorescence shows papilloma-like morphology in Leprnull PDV tumours and SCC morphology in Leprctrl PDV tumours. Scale bars, 50 µm. d, LEPR signalling functions in SCC progression. Lentiviruses containing doxycycline (doxy)-inducible versions of either full-length (FL) Lepr or LeprΔsig were transduced into Leprnull PDV SCC cells expressing rtTA3 (required for doxycycline-induced activation of the TRE) (Extended Data Fig. 6d). Leprnull PDV tumour growth is robust only when full-length Lepr but not LeprΔsig is reintroduced into tumour cells (n = 6, P = 0.0008 for the end timepoint), underscoring the need for active LEPR signalling, and not merely LEPR, in tumour growth. For a, c and d, statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. For a, c and d, data are mean ± s.e.m. aa, amino acids. The diagrams in c and d were created using BioRender.

Extended Data Fig. 6. Lepr ATAC peak activity is sensitive to TGFβ and to Lepr knockout or overexpression.

a, Lepr cis-regulatory region reporter (see Fig. 2g and Extended Data Fig. 5f) was transduced into PDV SCC cells and tested for its sensitivity to TGFβ in vitro. Flow cytometry quantifications show that Lepr reporter-fluorescence is strongly accentuated in the presence of active recombinant TGFβ1 (n = 3, p = 0.0068). b, Leprnull PDVC57 SCC cells were generated by targeted CRISPR/CAS9 technology and validated by iSeq. Blue denotes sequence comparison region; green sgRNA; red, Lepr frameshift mutation in Clone 2. MiSeq analysis of Lepr targeted Clone 1 (which did not alter LEPR expression), and Clone 3 (which did reduce LEPR expression but not to the extent of Clone 2). Immunoblot (right) shows complete loss of LEPR protein in this clone, which was selected for further study. GAPDH is used as loading control. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 2a. c, Quantifications showing reduced proliferation in Leprnull compared to LeprCtrl PDV tumours, as judged by EdU-labelling 2 h prior to harvesting. (n = 5 tumours per condition, p = 0.0024). d, Transduced cells are validated by pan-LEPR immunoblot analysis. Brackets denote expected sizes of full-length (FL) LEPR and Δsig LEPR, which lacks the LEPR-signalling domain. α-Tubulin is used as loading control. For gel source data, see Supplementary Fig. 2b. All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Intradermal grafting of our PDV lines in Nude mice revealed Leprctrl tumours displaying features of SCCs by 3 weeks and, by 5 weeks, they reached the maximum allowable size (AALAC regulations). By contrast, Leprnull PDV tumours were considerably smaller and exhibited papilloma-like morphology (Fig. 3c). As judged by labelling of S-phase cells with thymidine analogue 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), Lepr loss reduced, although did not abrogate, proliferation within the tumour (Extended Data Fig. 6c).

LEPR signalling mediates malignancy

To test whether active LEPR-signalling is required to drive SCC progression, we asked whether we could rescue the inhibitory effects of Lepr ablation with an inducible Lepr transgene that lacked the encoded cytoplasmic signalling domain of LEPR (ΔSig). Allografts on non-obese host mice revealed that even though transduced full-length LEPR was expressed at lower levels than the control, it restored aggressive SCC tumour growth to PDV Leprnull cells. By contrast, the expression of LEPR(ΔSig) had little if any effect (Fig. 3d and Extended Data Fig. 6d). Thus, LEPR signalling, and not merely the presence of LEPR, was critical in driving SCC progression of RAS-driven oncogenic stem cells.

Angiogenesis increases tumour leptin

As judged by tumour lysate ELISAs, leptin levels were greater than 5× higher in total tumour tissue of SCC relative to papilloma (Fig. 4a). This rise emanated from the tumour microenvironment, as neither the epithelial papilloma nor SCC cells expressed the ligand (Extended Data Fig. 2g). Turning to the source of elevated leptin, we first considered direct delivery from local fat, but saw no overt signs of increased adipogenesis in the tumour microenvironment as judged by Oil red O staining (Fig. 4b). Analogously, neither stroma nor FACS-purified stromal populations displayed appreciable Lep mRNA that might account for the rise in leptin protein within the SCC microenvironment (Fig. 4c).

Fig. 4. Leptin levels increase in the malignant tumour microenvironment and are caused by elevated angiogenesis.

a, ELISAs. Leptin in tumour tissue lysates is elevated as papillomas progress to SCC. n = 4 tumours per stage. P = 0.0322. b, Oil red O staining shows no overt signs of mature adipocytes (red) within the stroma surrounding SCCs versus papillomas. Scale bars, 250 µm. c, Quantitative PCR reveals no significant Lep transcriptional differences in the tumour microenvironments of SCCs versus papillomas. The positive control is Lep mRNA from white adipose tissue beneath the normal trunk skin. n = 3 (each whole tissue condition), n = 5–9 (each FACS-isolated population). d, The levels of blood plasma leptin in normal, papilloma and SCC-bearing mice are appreciable, but do not significantly differ. n = 6 for each condition. e, Tumour growth and angiogenesis are enhanced by intradermal recombinant mouse VEGFA (rmVEGFA), injected every 3 days into PDV SCC tumours and assayed beginning at day 21 after grafting. VEGFA increases the CD31+ tumour vasculature, as judged by flow cytometry. n = 8 (left) and n = 4 (right) tumours per condition. P = 0.0002 for the end timepoint (left); P = 0.0440 (right). The vehicle control was PBS without mouse VEGFA. f, Elevated expression of SCC stem cell C2 signature gene Vegfa is sufficient to enhance local angiogenesis and elevate leptin levels in the tumour microenvironment. TRE-HRASG12V mice were transduced in utero with low-titre lentivirus containing EEF1A1-rtTA3 with TRE-Vegfa or TRE-STOP (schematic). The quantification shows that, after 4 weeks of doxycycline induction, CD31+ vasculature (n = 3 tumours per stage, P = 0.0133) and tissue leptin levels (n = 5, control tissues, n = 6, TRE-Vegfa tissues; P = 0.0093) are increased in tumours with CSCs that express elevated Vegfa. On the basis of the immunofluorescence analysis, VEGFA over-expressing tumours advance to invasive (arrowhead) SCCs when the controls are still papillomas. Scale bars, 50 µm. g, SCC tumour growth is sensitive to plasma leptin levels. Recombinant leptin or mutant SMLA leptin agonist (doses indicated) was delivered to the circulation by an osmotic pump and the effects on PDV SCC tumour growth were monitored for 5 weeks. n = 12 (PBS control), n = 8, (each LEP or SMLA condition). From top to bottom, P = 0.0121, P = 0.0194, P = 0.0392. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests (a and d–g). Data are mean ± s.e.m. (a and c–g). aa, amino acids.The diagrams in f and g were created using BioRender.

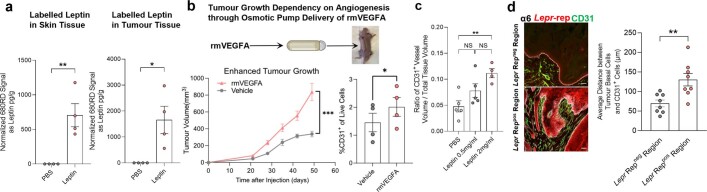

As circulating leptin crosses the blood–brain barrier25, we next considered the circulation as a possible source of tumour tissue leptin. We first used an osmotic pump to deliver fluorescently labelled leptin to the circulation and verified leptin’s ability to enter both normal skin dermis and tumour stroma from circulation (Extended Data Fig. 7a). Leptin normally circulates through the bloodstream, which we corroborated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) of blood plasma from non-tumour bearing control mice. However, in contrast to obese animals, in which serum leptin is elevated25,29, our tumour-bearing mice were not obese, and we did not detect a significant increase in serum leptin during tumour progression (Fig. 4d).

Extended Data Fig. 7. Increased angiogenesis elevates local leptin levels and promotes Lepr-mediated tumour progression.

a, Fluorescently labelled leptin placed in the circulation can elevate local tissue levels of leptin in the skin and skin tumours. ELISA-like assays show that by delivery of 680RD labelled recombinant leptin through osmotic pump for 1W, fluorescence can be detected in skin and tumour tissue lysatesin a dose-depend manner. (n = 4 for each condition; Left: p = 0.0055; Right: p = 0.0199). b, Tumour growth and angiogenesis are enhanced by systemic recombinant mouse mVEGFA, delivered to the circulation by an osmotic pump distant from PDV SCC tumour sites, which are monitored for about 5W. CD31+ tumour vasculature is evaluated by flow cytometry (Left: n = 8 tumour per condition, p = 0.0004 for the end time point; Right: n = 4 per condition, p = 0.0461, paired due to the nature of angiogeneiss and relative location of pump). Vehicle control is PBS lacking mVEGFA. c, Osmotic pump delivery of recombinant protein to elevate circulating leptin levels does not appreciably induce angiogenesis in normal skin. Leptin was administered at two different doses and PBS was used as a control (n = 5 for each condition, p(PBS-Lep0.5) = 0.1133, p(Lep0.5-Lep2) = 0.0865, p(PBS-Lep2) = 0.0029). When taken with Fig. 4g, this finding indicates that elevated levels of plasma leptin on its own is sufficient to enhance tumour growth, independent of possible secondary consequences arising from enhanced angiogenesis that might otherwise bring other hormones or growth factors to the surrounding tumour tissue. d, Immunofluorescence of tissue sections for Lepr reporter and CD31. EGFP labels the CSCs; CD31 labels the vasculature. Quantifications are based on the average distance from the CD31+ vasculature to tumour basal cells with or without reporter signalling. (n = 8 regions per condition, p = 0.0049). All statistics were using unpaired (unless noted) two-tailed Student’s t-test: NS, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Scale bars, 50 µm. The diagram in b was created using BioRender.

Given these collective results, we examined whether the rise in local vasculature might be at the root of the elevated tissue leptin associated with SCCs. To test this possibility, we first intradermally injected recombinant VEGFA and verified that both angiogenesis and tumour growth were markedly increased (Fig. 4e). To guard against wound-induced effects due to injections, we also validated these effects by osmotic pump implantation to deliver VEGFA systemically (Extended Data Fig. 7b).

As Vegfa is an early-activated, C2-enriched CSC gene, we pursued its physiological importance by expressing a doxycycline-inducible Vegfa transgene in our TRE-HRASG12V tumorigenesis model. Notably, Vegfa induction in the CSCs directly increased local angiogenesis and invasive tumour behaviour. Most importantly, the ensuing elevated angiogenesis directly elevated leptin levels in the tumour microenvironment (Fig. 4f).

As increasing capillary density might elevate additional hormones and growth factors within the tissue, we used an osmotic pump to directly manipulate leptin levels in the circulation. Using different doses of recombinant leptin as well as a superactive mouse leptin antagonist (SMLA) that abrogates leptin’s signalling activity even when bound to LEPR30, we further found that circulating leptin accelerated tumour growth in a dose-dependent manner, whereas SMLA had a slightly repressive effect (Fig. 4g). These findings underscored the ability of circulating leptin on its own to affect tumour progression.

Finally, we did not observe a substantial change in angiogenesis in the skin when we elevated circulating leptin in non-tumour-bearing mice, consistent with the view that, in SCCs, leptin is not the driver but rather the consequence of the elevated angiogenesis that occurs during malignant progression. That said, there was a measurable modest difference, raising the possibility that a feed-forward loop may be operating during malignant progression (Extended Data Fig. 7c). Overall, when coupled with the enhanced proximity of Lepr reporter activity to blood vessels in SCC-CSCs (Extended Data Fig. 7d), our results provide compelling support for a model in which increased angiogenesis at the invasive SCC front endows the tumour microenvironment with an ample supply of leptin, while perivascular-associated immune and other stromal cells6,19 provide the TGFβ necessary to induce Lepr expression in CSCs.

A LEPR–PI3K–AKT–mTOR path to malignancy

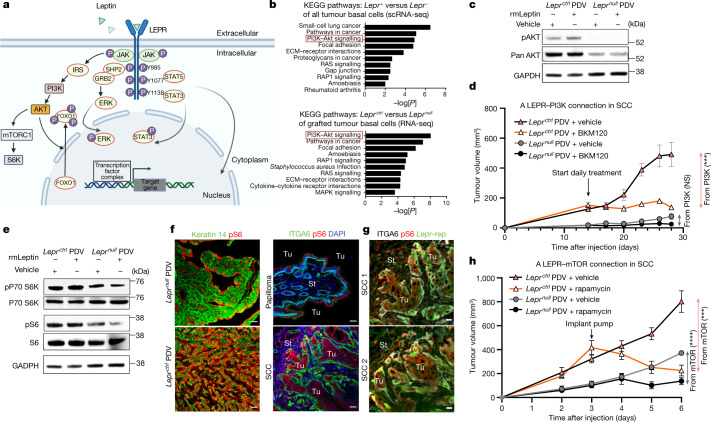

In other cellular contexts, LEPR signalling relies on its association with the Janus kinase (JAK2), which, after leptin-LEPR binding, phosphorylates LEPR’s intracellular domain. Once phosphorylated, LEPR has been implicated in activating various downstream pathways, including signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) and PI3K31,32 (Fig. 5a).

Fig. 5. Leptin receptor signalling promotes SCC progression through the PI3K–AKT and mTOR pathways.

a, Schematic illustrating the complexities of leptin receptor signalling. b, The top ten KEGG pathways of genes significantly upregulated in progenitors of Lepr-expressing HRAS(G12V) SCCs (data from Fig. 1) (top) and Leprctrl versus Leprnull PDV tumours (bottom). P values were calculated using DAVID bioinformatic analysis. c, Immunoblots of protein lysates from Leprnull and Leprctrl SCC cells treated with recombinant leptin or vehicle control for 48 h before analysis. Note the leptin-dependent activation of pAKT exclusively in LEPR+ cells, along with higher AKT levels (Extended Data Fig. 8e). Gel source data are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1b. d, Immunocompromised mice with Leprctrl and Leprnull PDV tumours on opposite sides of their backs were administered the PI3K inhibitor BKM120 or vehicle control daily through oral gavage beginning at 14 days after PDVC57 cell injections. As judged by this assay, most tumour growth attributable to PI3K signalling operates through LEPR. n = 6 for each condition. P = 0.0576 (Leprnull) and P = 0.0007 (Leprctrl) at the end timepoint. e, Immunoblotting reveals signs of mTORC1 pathway elevation (pS6 and pS6-kinase) after leptin–LEPR signalling in vitro. An identical GAPDH image from Fig. 5c is displayed here as a reference, as they are from the same experiment. Gel source data and experiment details are provided in Supplementary Fig. 1b. f, The importance of leptin–LEPR signalling in activating mTORC1 signalling is accentuated in vivo, where the background from other growth factors in enriched medium is eliminated. pS6 immunofluorescence reveals LEPR dependency on mTORC1 activity in PDV-engrafted tumours and particularly pronounced activity at the invading fronts of LEPR+ HRASG12V SCCs. Scale bars, 50 µm. g, pS6 immunofluorescence (mTORC1 activity) and Lepr eGFP reporter (rep) activity co-localize in cells at invading HRASG12V SCC fronts. Scale bars, 20 µm. h, Immunocompromised mice with Leprctrl and Leprnull PDV tumours on opposite sides of their backs were continuously administered rapamycin or vehicle control at t = 3 weeks and then monitored for tumour progression. As judged by this assay, most tumour growth attributable to mTOR signalling operates through LEPR. n = 6 (each condition). P < 0.0001 (Leprnull) and P = 0.0002 (Leprctrl) at the end timepoint. For d and h, statistical analysis was performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests. Data are mean ± s.e.m. (d and h). The diagram in a was created using BioRender.

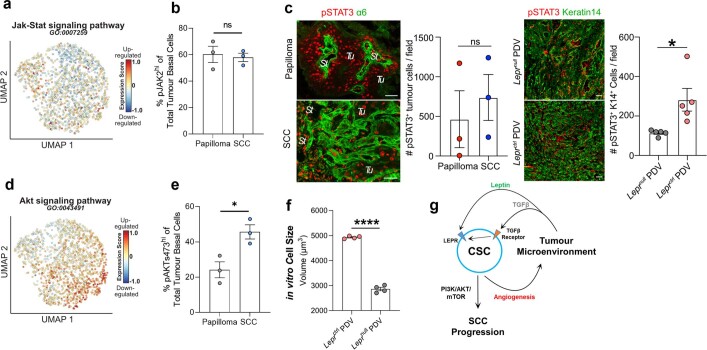

At the transcriptional level, the JAK–STAT signature showed no enrichment in our SCC-CSCs and, although flow cytometry verified JAK2 phosphorylation, the differences between papilloma and SCC, while variable, were not significant (Extended Data Fig. 8a,b). STAT3 was also phosphorylated and present in the nucleus in papillomas and, although pSTAT3 was diminished in Leprnull PDV tumours, it was not abrogated (Extended Data Fig. 8c). Thus, LEPR–leptin signalling appeared to act as a catalyst to enhance, not induce, JAK–STAT signalling to a level that facilitated progression from the benign to invasive state in SCCs.

Extended Data Fig. 8. Akt but not Jak/Stat pathway signature is enriched in SCC CSCs.

a, The Jak-Stat pathway mRNA signature is not enriched in any of the three scRNAseq SCC clusters. b, Flow cytometry for pJAK2 reveals that JAK-signalling is activated in skin tumours, but is not significantly changed between papillomas and SCCs. (n = 3 for independent tumours per stage. p = 0.7565 with two-sided unpaired Student’s t-test.). c, pSTAT3 immunofluorescence shows that although not detected in homeostatic skin, STAT3 is activated similarly in both papilloma and SCC (left). pSTAT3 is reduced but not abolished in Leprnull compared to LeprCtrl PDV tumours (right), suggesting that LEPR’s main role in SCC tumour progression is not to activate STAT3. Scale bars, 50 µm. Quantifications accompany each analysis. (Left: n = 3 for tumours per stage, p = 0.5835; Right: n = 5 for tumours per condition, p = 0.0195. All are independent samples.). d, Lepr downstream signalling Akt pathway mRNA signature is enriched in C2 cluster of scRNAseq of SCC. e, Flow cytometry reveals that the percentage of pAKTs473 cells is higher in SCC than papilloma. (n = 3 for independent tumours per stage, p = 0.0237). f, Leprctrl PDV cells are significantly larger in size compared to Leprnull PDV cells (n = 4 for each condition, p < 0.0001). g, Schematic summarizing our findings. During tumour progression, dynamic crosstalk between HRASG12V oncogenic epithelial SCs and their tumour microenvironment promotes an increase in the production of angiogenesis factors by emerging SCC-CSCs, which in turn fuels angiogenesis, elevating the levels of circulating factors, such as leptin by increasing vasculature density. The perivasculature also raises local immune cells that elevate local TGFβ levels. Enhanced TGFβ-signalling in the CSCs not only promotes an EMT-like invasion6, but also activates Lepr transcription. This triggers a leptin-LEPR signalling cascade, elevating PI3K-AKT-mTORC signalling and fuelling SCC progression. The genes in this cascade are often found mutated in cancers, but as shown here, can be driven by interactions between CSCs and their tumour microenvironment. See also Fig. 5a. All statistics were using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-test: ns, p ≥ 0.05); *, p ≤ 0.05); **, p ≤ 0.01; ***, p ≤ 0.001; ****, p ≤ 0.0001. Data are presented as mean ± s.e.m.

Turning to an unbiased approach to delve further into mechanism, we analysed our transcriptomes of individual SCC basal cells according to their level of Lepr expression. On the basis of Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis, the top three pathways distinguishing Lepr+ versus Lepr− basal SCC cells were small-cell lung cancer (oncogenic RAS-associated), pathways in cancer and the PI3K–AKT signalling pathway (Fig. 5b, top). Indeed, comprehensive gene signature expression scores for the AKT signalling pathway showed significant upregulation in C2 SCC-CSCs, with a marked elevation between papilloma and SCC states (Extended Data Fig. 8d,e).

To examine the PI3K–AKT connection further, we performed bulk RNA-seq analysis of FACS-purified basal cells from tumours that developed from our engrafted PDVC57 cells. KEGG analysis placed the PI3K–AKT signalling pathway at the top of molecular features that distinguished Leprctrl versus Leprnull tumours (Fig. 5b, bottom). Taken together, LEPR-PI3K–AKT surfaced as a top candidate for a signalling pathway that could account for the heterogeneity in our basal progenitor population of invasive SCCs.

In vitro, Leprctrl but not Leprnull SCC cells were sensitive to AKT–PI3K signalling in the presence of recombinant leptin. As judged by immunoblot analyses, both AKT stability and activation (phosphorylation) were enhanced by leptin, but only if SCC cells expressed LEPR (Fig. 5c). Moreover, when we blocked PI3K signalling directly in vivo, the oral PI3K inhibitor BKM12033 reduced tumour growth in only Leprctrl SCC and not in Leprnull SCC (Fig. 5d). Considering the many routes through which PI3K–AKT can be activated, its robust link to LEPR signalling in driving oncogenic RAS tumours to an invasive SCC state was surprising and suggested that, in this context, LEPR–leptin signalling has a profound role in orchestrating the PI3K–AKT cascade and fuelling SCC tumour growth.

Through mechanisms that vary depending on cellular circumstances, PI3K–AKT signalling can lead to the activation of mTOR—a central metabolic mediator in some cancers34–36. In agreement, Leprctrl PDV cells in vitro were larger in size compared with Leprnull PDV cells (Extended Data Fig. 8f). Moreover, both mTOR target, the serine/threonine kinase p70-S6K, and ribosomal protein S6 (a proxy for active p70-S6K and enhanced protein synthesis at the ribosome)37 displayed phosphorylation in a Lepr-sensitive manner (Fig. 5e).

The importance of LEPR in regulating PI3K–AKT–mTOR in SCC-CSCs extended to in vivo tumours. Thus, tumours arising from engrafted Leprnull PDV cells displayed reduced pS6 immunofluorescence compared with aggressive SCCs derived from Leprctrl PDV engraftments (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, in the HRAS(G12V)-mediated transition from papilloma to SCC, pS6 was elevated at invasive SCC fronts and, when imaged with our Lepr reporter, pS6 and eGFP showed considerable overlap in these regions (Fig. 5g).

Finally, continuous delivery of the potent mTOR inhibitor rapamycin resulted in reduced growth of tumours derived from engrafted Leprctrl PDV cells (Fig. 5h). By contrast, rapamycin had less effect on Leprnull tumours, the growth of which was already restricted by LEPR loss of function. Notably, although the GO terms for LEPR sensitivity pointed to the PI3K–AKT pathway, AKT can also be phosphorylated by mTORC1, leaving open the possibility of feedback mechanisms arising downstream of LEPR signalling.

Discussion

Human studies on SCCs have centred largely around invasive metastatic cancers, which often contain a myriad of oncogenic mutations. However, the tumour microenvironment can be equally impactful in driving malignant progression, as exemplified by the effects of obesity on cancer14,38,39. In the attempt to identify obesity-driven tumour susceptibility pathways that might alter energy balance, leptin–LEPR signalling has been a focus of cancers of which the normal stem cells express LEPR and exist in a fatty tissue microenvironment in which local leptin is high35,40,41. For cancers such as SCCs that originate from native tissues that do not express LEPR, reports of LEPR expression have relied mostly on immunolabelling with antibodies of unclear specificity42–44.

How alterations in LEPR signalling contribute to tumour progression and metastasis has remained unclear. Mechanistic insights have relied on cultured cancer cell lines, in which different possible routes have been proposed35,43,45 (Fig. 5a). Moreover, it was recently demonstrated that obesity generated by leptin deficiency in mice can affect KRAS-induced pancreatic cancer progression not through impaired LEPR-signalling but, rather, through an obesity-specific mechanism involving aberrant endocrine–exocrine signalling in the adapting pancreatic beta cells14.

In our in vivo studies, we did not use an obesity model, nor did we focus on a naturally adipose-rich tissue microenvironment. Rather, we uncovered a cancer link to the leptin–LEPR signalling pathway that becomes activated de novo downstream of an oncogenic HRAS(G12V)-induced change within otherwise normal skin stem cells. In marked contrast to oncogenic KRAS-induced pancreatic cancers, which are influenced heavily by obesity but not leptin14, or to pathogen infections that can elicit transient changes in local adipose tissue/leptin levels that affect wound repair46, malignant progression in HRAS-induced cutaneous cancers requires the induction of LEPR signalling by the stem cells, but neither obesity nor adipogenesis in the local tissue environment.

LEPR signalling during SCC progression appears to be rooted in two events: first, a CSC-mediated influx of vasculature within the tumour microenvironment that increases blood vessel density at the invasive front and in turn causes local leptin levels to rise within the tumour stroma; and second, a corresponding rise in perivascular TGFβ that enhances TGFβ signalling and Lepr gene expression within neighbouring SCC-CSCs. Thus, through the ability of oncogenic RAS to reroute the stem cell’s communication circuitry with its surrounding microenvironment, and the ability of the microenvironment in turn to induce a membrane receptor on the stem cells, CSCs exploit this dynamic crosstalk, fuelling non-genetic circuitries that drive malignant progression (Extended Data Fig. 8g). How leptin transits across the vasculature remains unclear25,29, although it is intriguing to speculate that, for solid tumours such as SCCs, mechanical pressures might alter the vascular integrity and facilitate entry of circulating factors such as leptin into the tumour microenvironment.

In summary, the acquisition of an oncogenic RAS mutation sparks the perfect crosstalk between tumour-initiating cells and their microenvironment, enabling them to hijack the LEPR-signalling pathway and fuel cancer progression. In this regard, the downstream consequences of LEPR signalling, namely sustained activation of the PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway, become all the more important because, among human cancers, PI3KCA is among the most commonly mutated genes and a target of emerging anti-cancer therapeutics7,36. Our findings raise the tantalizing possibility that PIK3CA mutations may not be essential to sustain the PI3K pathway at a level required for malignancy, even though mutational burden may help to bolster it. Similarly, although polymorphisms in Lep and Lepr have been associated with oral SCCs47, our data clearly show that, even if a causal link emerges in the future, such genetic alterations are not required to initiate signalling. Rather, an oncogenic RAS mutation has the ability to launch an aberrant dialogue between the SCs and their normal tissue microenvironment. Furthermore, as SCC-CSCs emerge, they co-opt many of the same signalling pathways achieved by a high mutational burden—a feature with profound implications for our understanding of cancer.

Methods

Animals

TRE-HRASG12V mice have been described previously48. The original TRE-HRASG12V C57Bl/6 mice have been backcrossed 10 generations to an FVB/N background. FVB/N TRE-HRASG12V mice were bred to FVB/N R26-LSL-YFP mice to create the TGFβ-reporter lineage-tracing model. For the Tgfbr2-cKO experiment, FR-LSL-HrasG12V;Tgfbr2fl/fl;R26-LSL-YFP mice were crossed in-house. For tumour transplantation experiments, 7–9-week-old female NU/NU Nude mice from Charles River were used. All other studies used a mix of male and female mice, which for the assays used here, behaved similarly. The animals were maintained and bred under specific-pathogen-free conditions at the Comparative Bioscience Center (CBC) at The Rockefeller University, an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care (AALAC)—an accredited facility. Adult animals were housed in a cage with a maximum of five mice unless specific requirements were needed. The light cycle was from 07:00 to 19:00. The temperature of the animal rooms was 20–26 °C, and the humidity of the animal rooms was 30–70%. All mouse protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at The Rockefeller University.

As tumours began to progress to the malignant stage (size > 10 mm), mice were housed individually and antibiotic cream was applied to the surface of the ulcerated tumour. When tumour sizes approached 15 mm, intraperitoneal injection of Bup was used every 8 h to minimize pain. Mice were euthanized once the tumour size exceeded 20 mm or if mice showed any signs of distress, for example, difficulty in breathing.

Cell lines

The mouse cutaneous SCC cell line PDVC57 was cultured in the E-low medium (E.F.’s laboratory)5. Mouse keratinocyte cell line FF (Tgfbr2f/fPGK-HrasG12V) and ΔΔ (Tgfbr2nullPGK-HrasG12V) were cultured with the E-low medium as previously discribed6. The HNSCC cell line A431 was cultured in DMEM medium (Gibco) with 10% FCS, 100 U ml−1 streptomycin and 100 mg ml−1 penicillin. The HEK 293TN cell line for lentiviral production was cultured in DMEM medium supplemented with 10% FCS (Gibco), 1 mM sodium pyruvate, 2 mM glutamine, 100 U ml−1 streptomycin and 100 mg ml−1 penicillin. The 3T3J2 fibroblast feeder cell line was expanded in DMEM/F12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) with 10% CFS (Gibco), 100 U ml−1 streptomycin and 100 mg ml−1 penicillin. It was then treated with 10 µg ml−1 mitomycin C (Sigma-Aldrich) for 2 h to achieve growth inhibition.

The human skin SCC line A431 was from ATCC; mouse skin SCC PDVC57 was a gift from the original laboratory that created it (Balmain lab); mouse keratinocyte cell lines FF (Tgfbr2f/fPGK-HrasG12V) and ΔΔ (Tgfbr2null PGK-HrasG12V) were generated in E.F.’s laboratory; mouse fibroblast 3T3/J2 has been passaged in the laboratory as feeder cells and originated from the laboratory of H. Green; HEK 293TN cells were purchased from SBI directly as low passage (P2) for lentiviral packaging. PDVC57 was validated by karyotyping and grafting tests. Mouse keratinocyte cell lines were validated previously in E.F.’s laboratory. 3T3/J2 has been functionally and morphologically validated as feeder cells. HEK 293TN cells were functionally tested as packaging cells producing lentivirus. A431 was not authenticated.

Human tumour samples

Human skin and SCC tumour samples were acquired as frozen tissue from B. Singh at Weill Cornell Medical College. All of the samples were de-identified according to National Institutes of Health and Federal/State regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all human research participants at Weill Cornell Medical College, and in accordance with approved Institutional Review Broad (IRB) protocols from The Rockefeller University, Weill Cornell Medical College and Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

Lentiviral in utero transduction

Lentiviral constructs were previously described (SBE-NLSmCherry-P2A-CreERT2 PGK-rtTA3)6 or cloned in E.F.’s laboratory (SBE-NLSmCherry PGK-rtTA3, Lepr peak reporter-eGFP PGK-rtTA3, TRE-Lepr-IRES-eGFP, PGK-rtTA3, TRE-Vegfa EEF1A1-rtTA3, TRE-STOP EEF1A1-rtTA3). The lentiviral production and in utero injection were performed as previously described6,23. In brief, pregnant female mice with a doxycycline-inducible HRASG12V transgene were anaesthetized with isoflurane (Hospira) when their embryos were at E9.5. Lentivirus (500 nl to 1 µl) was injected into the amniotic sacs of the embryos to selectively transduce a small number of individual epidermal progenitors within the surface monolayer that gives rise to the skin epithelium49. Postnatal induction of tumorigenesis in clonal patches was achieved by doxycycline administration (2 mg per g) through the feed.

Tumour formation and grafting

To induce spontaneous tumour formation, transduced TRE-HRASG12V or TRE-HRASG12V R26-LSL-YFP mice were continuously fed doxycycline-containing chow (2 mg per g) from postnatal day 0 to 4 to activate the rtTA3 transcription factor and induce tumorigenesis. Papillomas appeared by around 4 weeks and progressed to SCCs by about 8 weeks. To activate the creERT2 in lineage-tracing experiments, 100 μg tamoxifen (Sigma-Aldrich) was injected intraperitoneally into tumour-bearing mice daily for 3 consecutive days. For tumour allograft studies, 1 × 105 mouse PDVC57 SCC cells were mixed with growth-factor-reduced Matrigel (Corning) and intradermally injected into NU/NU Nude immunocompromised mice. Visible tumours appeared after 3 weeks. For metastatic tumour xenografts, 1 × 105 human SCC A431 cells were resuspended in sterile PBS and tail-vein injected into immunocompromised Nude mice. Mouse lung tissue with metastatic lesions was collected after 3 weeks. The volume of the tumour was calculated using the following formula: , where x, y and z are three-dimensional diameters measured using digital callipers (FST).

Immunofluorescence and histology

For both histology and immunofluorescence analysis, tumour tissues were fixed in 4% PFA at room temperature for 15 min, and then washed three times with PBS at 4 °C. For histology, samples were dehydrated in 70% ethanol overnight, and were sent to Histowiz for Oil Red O and H&E staining. For immunofluorescence, after PBS washes, the samples were dehydrated in 30% sucrose in PBS solution overnight at 4 °C. The dehydrated tissues were embedded in OCT medium (VWR). Cryosections (10 µm) were blocked in PBS blocking buffer with 0.3% Triton X-100, 2.5% normal donkey serum, 1% BSA, 1% gelatin. After blocking, the sections were stained with primary antibodies: ITGA6 (rat, 1:2,000, BD), RFP/mCherry (guinea pig, 1:5,000, E.F.’s laboratory), K14 (chicken, 1:1,000, BioLegend), CD31 (rat, 1:100, BD Biosciences), K5 (guinea pig, 1:2,000, E.F.’s laboratory), K8 (rabbit, 1:1,000, E.F.’s laboratory), mLEPR (goat, 1:200, R&D Systems), hLEPR (rabbit, 1:100, Sigma-Aldrich), RUNX1 (rabbit, 1:100, Abcam), FOS (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signalling), GFP (chicken, 1:500, BioLegend), pSTAT3-Y705 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signalling), pSMAS2-S465/467 (rabbit, 1:1,000, Cell Signalling) or pS6-S240/244 (rabbit, 1:100, Cell Signalling). For pSTAT3 immunolabelling, sections were pretreated with ice-cold 100% methanol for 30 min before blocking. After primary antibody staining, all sections were washed three times with PBS wash buffer containing 0.1% Triton X-100 for 5 min at room temperature. For pSMAD2 immunolabelling, sections were pretreated with 3% H2O2 for 1 h before blocking, stained using the appropriate HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch) and amplified using the TSA plus Cy3 kit (Akoya Biosciences) in combination with other regular co-stains. The sections were then labelled with the appropriate Alexa 488-, 546- and 647-conjugated secondary antibodies (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and imaged using the Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 with Apotome 2 microscope. Images were collected and analysed using Zeiss Zen software.

For immunofluorescence microscopy of thick tumour sections, all collected tumours were fixed with 1% (v/v) paraformaldehyde/PBS overnight at 4 °C and washed three times with PBS. After an overnight incubation with 30% (w/v) sucrose/PBS at 4 °C and embedding in OCT, 100 μm cryosections were washed with PBS and transferred to a 24-well dish. After overnight permeabilization with 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS at room temperature with rotation, tissue was blocked for 4–6 h with 5% donkey serum and 1% bovine serum albumin in 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS (blocking buffer). Tissue was then incubated with the following primary antibodies for 2 days at room temperature: mCherry (Abcam, 1:1,000), CD31 (Sigma-Aldrich, 1:300), keratin 14 (E.F.’s laboratory, 1:400), Keratin 18 (rabbit, 1:300, E.F.’s laboratory), GFP (chicken, 1:300, E.F.’s laboratory) and ITGA6 (Rat, 1:300, BD Biosciences) before several washes with 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS. The tissue sections were incubated with secondary antibodies (Alexa Fluor-RRX, -488 or -647 hamster, rat, chicken and rabbit at 1:1,000) diluted in blocking buffer overnight (16–20 h) together with DAPI at room temperature and washed with 0.3% Triton X-100/PBS with several exchanges. Immunolabelled tissue sections were then dehydrated with a graded ethanol series by incubation in 30% ethanol, 50% ethanol and 70% ethanol, each set to pH 9.0 as described previously50 for 1 h per solution, before a 2 h incubation with 100% ethanol, and cleared to optimize optical sectioning and imaging penetration by overnight incubation with ethyl cinnamate (Sigma-Aldrich). Cleared tumour samples were imaged in 35 mm glass-bottom dishes (Ibidi) with an inverted LSM Zeiss 780 laser-scanning confocal microscope and/or Andor dragonfly spinning disk. Images were then analysed using Imaris imaging software (Bitplane). The shortest distance and volume measurements were performed by the creation of individual objects of CD31+ blood vessels, K14+ tumour mass, K18+ tumour cells or Lepr reporter+ tumour cells.

Cell sorting and flow cytometry

To sort the target tumour cell populations by FACS, tumours were first dissected from the skin and finely minced in 0.25% collagenase (Sigma-Aldrich) in HBSS (Gibco) solution. The tissue pieces were incubated at 37 °C for 20 min with rotation. After a wash with ice-cold PBS, the samples were further digested into a single-cell suspension in 10 ml 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco) for 10 min at 37 °C. The trypsin was then quenched with 10 ml FACS buffer (5% FCS, 10 mM EDTA, 1 mM HEPES in PBS). The single-cell suspension was centrifuged at 700 rcf. The pellet was resuspended in 20 ml FACS buffer and strained through a 70 μm cell strainer (BD Biosciences). The filtered samples were centrifuged at 700 rcf to pellet cells, and the supernatant was discarded. The cell pellet was then resuspended in primary antibodies. A cocktail of antibodies against surface markers at the predetermined concentrations (CD31–APC, 1:100, BioLegend; CD45–APC, 1:200, BioLegend, CD117–APC, 1:100, BioLegend; CD140a–APC, 1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific; CD29–APCe780, 1:250, Thermo Fisher Scientific; CD49f–PerCPCy5.5, 1:250, BioLegend; CD44–PECy7, 1:100, BD Biosciences) was prepared in the FACS buffer with 100 ng ml−1 DAPI. Furthermore, CD44–BV421 (1:100, BD Biosciences), CD49f–PECy7 (1:250, BioLegend) and CD29–APCCy7 (1:250, BioLegend) were also used as interchangeable staining in the panels for the same purpose. The samples were incubated on ice for 30 min, washed with FACS buffer twice and resuspended in FACS buffer with 100 ng ml−1 DAPI before FACS and analysis.

To sort the skin stem cell populations (IFE and HFSCs), whole back skins were first dissected from the mouse. After scraping off the fat tissues from the dermal side, the tissues were incubated in 0.25% trypsin/EDTA (Gibco) for 45–60 min at 37 °C. After quenching the trypsin with cold FACS buffer, the epidermal layer and hair follicles were scraped off the epidermal side of the skin. The tissues were mechanically separated/strained into a single-cell suspension for staining. A cocktail of antibodies for surface markers at the predetermined concentrations (CD31–APC, 1:100, BioLegend; CD45–APC, 1:200, BioLegend; CD117–APC, 1:100, BioLegend; CD140a–APC, 1:100, Thermo Fisher Scientific; CD29–APCe780, 1:250, Thermo Fisher Scientific; CD49f–PerCPCy5.5, 1:250, BioLegend; CD34–BV421, 1:100, BD Biosciences; CD200–PE, 1:100, BioLegend; SCA1–PECy7, 1:100, BioLegend) was prepared in the FACS buffer with 20 ng ml−1 DAPI when using an ultraviolet laser. The sorting was performed on BD FACS Aria equipped with FACSDiva software.

For the in vivo Lepr reporter SCC cell experiment, reporter PDVC57 cells were treated with TGFβ1 (10 ng ml−1) for 7 days. The treated reporter PDVC57 cells were stained with 100 ng ml−1 DAPI in FACS buffer and analysed on the BD Biosciences LSR Fortessa system together with the control treatment (BSA only).

For the phosphorylated protein flow cytometry experiment, single-cell suspensions were obtained from papilloma or SCC tumour tissues as described above. After washes with cold PBS, cells were stained with Live/Dead Blue (1:200, Thermo Fisher Scientific) on ice for 30 min, and then washed with FACS buffer and blocked with FACS buffer with 5% normal mouse serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific), 5% normal rat serum (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1× Fc Block (BioLegend) for 15 min on ice. The live cells were then stained with FITC-conjugated surface marker (DUMP) antibodies (CD31, CD45, CD117, CD140a) (Thermo Fisher Scientific and BioLegend) for 30 min. After washing with FACS buffer, cells were fixed with 1× Phosflow Lyse/Fix Buffer (BD Biosciences) at 37 °C for 10 min. After centrifuging and another wash with FACS buffer, the fixed cells were permeabilized with −20 °C prechilled Phosflow Perm Buffer III (BD Biosciences) for 30 min on ice. The samples were then washed twice with 1× Phosflow Perm/Wahs Buffer I (BD Biosciences), and stained with CD49f–BV510 (BD Biosciences), CD29–APCe780 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), CD44–BB700 (BD Biosciences), pAKTs473–BV421 (BD Biosciences) and pJAK2y1007/1008–Alexa647 (Abcam) antibodies for 2 h on ice. The samples were then washed and analysed on the BD Biosciences LSR Fortessa system. The flow cytometry data were analysed using FlowJo (BD Biosciences).

RNA purification and ATAC-seq library preparation

For bulk RNA-seq, targeted cell populations from 2 (SCC) to 15 (papilloma) tumours per population were directly sorted into TRI Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and the total RNA was purified using the Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep Kit (Zymo Research) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The integrity of purified RNA was determined using the Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer. Library preparation, using the Illumina TrueSeq mRNA sample preparation kit (non-stranded, poly(A) selection), and sequencing were performed at the Genomic Core Facility at Weill Cornell Medical College on the Illumina HiSeq 4000 system with the 50 bp single-end setting or the NovaSeq with the 100 bp paired-end setting.

For accessible chromatin profiling, target cell populations from 2 (SCC) to 15 (papilloma) tumours per population were sorted into FACS buffer, and ATAC-seq sample preparation was performed as described previously51. In brief, a minimum of 2 × 104 cells were lysed with ATAC lysis buffer on ice for 1 min. Lysed cells were then tagmented with Tn5 transposase (Illumina) at 37 °C for 30 min. Cleaned-up fragments were PCR-amplified (NEB) and size-selected with 1.8× SPRI beads (Beckman Coulter). Libraries were sequenced at the Genome Resource Center at The Rockefeller University on the Illumina NextSeq system with the 40 bp paired-end setting.

For scRNA-seq, target cell populations were sorted from 3–5 SCC tumours per mouse, for a total of 3 biological replicates (2 male and 1 female mice). Single-cell libraries were prepared according to a slightly modified Smart-seq2 protocol52. In brief, cells were sorted into 96-well plates containing hypotonic lysis buffer, snap-frozen with liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. To semi-quantitatively assess technical variation between cells, ERCC spike-ins (1:2 × 106 dilution, Thermo Fisher Scientific) were added with the lysis buffer. After thawing, cells were lysed at 72 °C for 3 min. Released RNA was reverse-transcribed using dT30 oligos, template switching oligos and Maxima H- reverse transcriptase. cDNA was amplified by 15 cycles of whole-transcriptome amplification using KAPA HiFi DNA polymerase (Roche) and then size-selected using 0.6× AmpPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter). To exclude wells containing multiple cells, as well as low-quality and empty wells, quantitative PCR with reverse transcription (RT–qPCR) for Gapdh was performed before proceeding. Illumina sequencing libraries were then prepared using the Nextera XT DNA library preparation kit (Illumina) and indexed with unique 5′ and 3′ barcode combinations. After barcoding, the samples were pooled and size-selected with 0.9× AmpPure XP beads. The integrity of the pooled library was assessed using the TapeStation (Agilent) before sequencing on two lanes of the Illumina NovaSeq S1 system using 100 bp paired-end read output (Illumina). For optimal sequencing depth, each sequencing library was sequenced twice, once in each lane of the Illumina NovaSeq system. Sequencing reads per cell from each lane were combined during alignment to the reference genome.

CRISPR-mediated Lepr knockout

Our Leprnull PDVC57 cell line was generated using the Alt-R CRISPR–Cas9 system (IDT). In brief, a recombinant Cas9 protein, validated sgRNA (GAGUCAUCGGUUGUGUUCGG) targeting exon 3 of the mouse Lepr gene or a negative control sgRNA (IDT), and an ATTO-550-conjugated tracer RNA were used to form a ribonucleoprotein (RNP) were mixed with RNAiMax reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific). PDVC57 cells were then transfected with the mixture overnight and FACS-purified into 96-well plates to produce clonal cell lines. The Leprnull PDVC57 cell line was selected after validating by immunoblot analysis of LEPR as well as sequencing of the target region for indel efficiency using the MiSeq system. The Leprnull PDVC57 cell line and Leprctrl PDVC57 cell line were intradermally injected into the immunocompromised Nude mice, and the tumours were analysed for growth and progression.

Rescue of LEPR in Leprnull PDVC57 SCC cells

Leprnull PDVC57 cells were transduced in vitro with 1:1 ratio of PGK-rtTA3 lentivirus and TRE-FL-Lepr-IRES-eGFP or TRE-LeprΔSig-IRES-eGFP lentivirus. After culturing in 1 μg ml−1 of doxycycline (Sigma-Aldrich) containing E-Low medium, eGFPhigh cells expressing Lepr were isolated by FACS and expanded in vitro. These two different cell lines were later intradermally grafted onto immunocompromised Nude mice, and the tumours were analysed for growth and progression.

Limiting dilution assay

To compare the tumour-initiating ability between Leprnull PDVC57 and Leprctrl PDVC57 cell lines, a preset number of cells were intradermally grafted onto Nude mice, and the tumour growth was tracked for 5 weeks to calculate the tumorigenicity of cells. As previously described23, SCC cells were diluted serially from 104 to 106 cells per ml and 100 µl cell mixtures in 1:1 PBS:Matrigel were injected. Four injections per mouse were performed under the animal facility regulations (for 105 and 104 per injection, n = 4; for 103 per injection, n = 8). Photos of mice were recorded, and tumours were counted at the end point 5 weeks after injection.

Osmotic pump for systemic delivery

To achieve continuous systemic delivery of compounds, Alzet osmotic pumps were implanted as previously described53 into the back skins of Nude mice. Three weeks after the initial intradermal tumour grafts, tumour-bearing Nude mice were anaesthetized and sterilized for surgical procedures. A small cut was created with scissors and the osmotic pump containing a predetermined concentration of compounds or vehicle was inserted underneath the back skin and the opening was clipped. For the leptin experiment, 4-week-long delivery pumps were used with 2 mg ml−1 leptin (R&D Systems), 0.5 mg ml−1 leptin, 0.5 mg ml−1 SMLA (BioSources) and PBS vehicle. Where indicated, fluorescently labelled (680RD) leptin as previously discribed54 was used to detect the ability of circulating leptin to reach the skin stroma. For the VEGFA experiment, 4-week-long delivery pumps were used with 50 μg ml−1 VEGFA (R&D Systems) and PBS vehicle. For the rapamycin experiment, 2-week-long delivery pumps were used with 10 mM rapamycin (SelleckChem) in PBS solution with 10% DMSO or with the respective vehicle control. Tumour sizes were then monitored for tumour growth and progression.

To achieve local delivery of compound, intradermal injections were performed into the skin adjacent to or underneath the grafted tumours of Nude mice. 50 μg ml−1 VEGFA (R&D Systems) and PBS vehicle were injected in a 50 μl volume every 3 days with a 1 ml syringe and a 26G needle (BD Biosciences).

RT–qPCR