Abstract

This study reports the existence of phospholipase C and D enzymatic activities in Mycobacterium ulcerans cultures as determined by use of thin-layer chromatography to detect diglycerides in hydrolysates of radiolabeled phosphatidylcholine. M. ulcerans DNA sequences homologous to the genes encoding phospholipase C in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Pseudomonas aeruginosa were identified by sequence analysis and DNA-DNA hybridization. Whether or not the phospholipase C and D enzymes of M. ulcerans plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease needs further investigation.

Mycobacterium ulcerans causes the skin disease commonly known as Buruli ulcer (BU), which is characterized by necrosis and the absence of a cellular inflammatory response (12). The increase in the incidence of BU in some regions of the world (2), especially in rural West Africa, led the World Health Organization to recognize BU as an emerging disease (25). Some studies have attempted to define and characterize secreted toxins of M. ulcerans (10, 20). Recently George et al. (6) identified a polyketide toxin from M. ulcerans, which they named mycolactone. When injected into the skin of guinea pigs, this toxin caused lesions similar to those of BU in humans. This toxin may play a role in the pathogenesis of BU; however, we believe that the possible existence of other virulence factors merits investigation (12). Phospholiphase C (PLC) and phospholiphase D (PLD) enzymatic activities are associated with virulence in several other species of mycobacteria (11).

The genome of Mycobacterium tuberculosis, which is closely related to M. ulcerans (23), contains multiple copies of plc genes homologous to the Pseudomonas aeruginosa genes plcH and plcN, encoding the hemolytic and nonhemolytic PLC enzymes, respectively (11, 14). The aim of this study was to attempt to detect PLC and PLD activities in M. ulcerans in vitro and to detect putative genes responsible for the enzymatic activity of the phospholipases.

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

The mycobacterial strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Identification at the species level was done by conventional tests (24). Homogeneous suspensions of all strains of mycobacteria, at 1 mg (wet weight) per ml of phosphate-buffered saline, were prepared from organisms subcultured on Löwenstein-Jensen medium. Ten milliliters of this bacterial suspension was inoculated into 90 ml of Dubos broth (Difco, Detroit, Mich.).

TABLE 1.

Mycobacterial strains studieda

| ITM strain no. | Species | Origin | Growth conditions (wk/°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5142 | M. ulcerans | ATCC 19423 | 8/33 |

| 5146 | M. ulcerans | DRCb | 8/33 |

| 5147 | M. ulcerans | Australia | 8/33 |

| 5150 | M. ulcerans | DRC | 8/33 |

| 9146 | M. ulcerans | Benin | 8/33 |

| 9550 | M. ulcerans | DRC | 8/33 |

| 97-112 | M. ulcerans | Benin | 8/33 |

| 97-116 | M. ulcerans | Benin | 8/33 |

| 94-511 | M. ulcerans | Ivory Coast | 8/33 |

| 94-1317 | M. ulcerans | Australia | 8/33 |

| 94-1326 | M. ulcerans | Australia | 8/33 |

| 7732 | M. marinum | ATCC 927 | 2/33 |

| 8171 | M. tuberculosis | Rwanda | 6/37 |

| 96-319 | M. bovis | Belgium | 6/37 |

| 4995 | M. smegmatis | ATCC 607 | 1/37 |

| 97-461 | M. fortuitum | ATCC 12790 | 1/37 |

| 5077 | M. gordonae | Belgium | 3/37 |

All strains were isolated at the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM), except for the Australian isolates, which were kindly provided by David Dawson, and the American Type Culture Collection strains.

DRC, Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Preparation of WCE and CF.

Cultures were centrifuged for 15 min at 3,000 × g. Supernatants and pellets were processed separately. To obtain whole-cell extracts (WCE), 1 g (wet weight) of pellet was resuspended in 1 ml of buffer A (50 mM Tris [pH 7.4], 50 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol) and ultrasonicated with a Sonifier 250 (Branson Sonic Power Company, Danbury, Conn.). Extracts were centrifuged and stored at −70°C until phospholipase assays were performed. For preparation of culture filtrates (CF), supernatant obtained from culture centrifugation was sterilized with Sterivex-GP 0.22-μm-pore-size filters (Millipore Corporation, Bedford, Mass.) and concentrated 50-fold by ultrafiltration (PM10 membrane; Amicon, Beverly, Mass.) before dialysis against buffer A.

Detection of PLC and PLD activities.

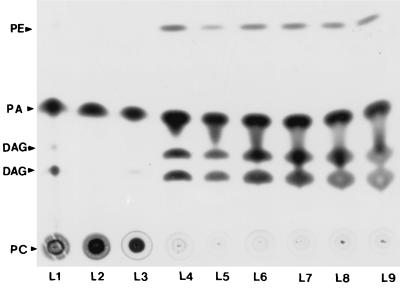

PLC and PLD activities were determined as previously described by Johansen et al. (11). Forty microliters of each sample was loaded in a silica gel glass plate (Merck, KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) and allowed to ascend in petroleum etherethyl etheracetic acid (50:50:1, vol/vol) until the solvent front was within 2 cm of the top of the plate. Plates were air dried and subjected to autoradiography for 1 week. All WCE from M. ulcerans produced phosphatidic acid (PA) and diacylglycerol (DAG) upon incubation with phosphatidylcholine (PC) with 14C labeling of the lipid moiety (Fig. 1). M. tuberculosis and Mycobacterium marinum seemed to be less efficient than M. ulcerans in converting PC into DAG (Fig. 1). The WCE from M. ulcerans, M. tuberculosis, Mycobacterium smegmatis, and M. marinum possessed PLD activity. Interestingly, PA and DAG were also detected in CF from all M. ulcerans strains, as well as those of M. tuberculosis and M. marinum. In contrast, CF from M. smegmatis produced only PA upon incubation with PC, showing that these organisms express functional PLD but probably not PLC protein. The presence of PLC enzymatic activity in M. ulcerans may be significant for several reasons. At the immunological level, PLC yields DAG and inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate, which in turn activates protein kinase C, causing malfunction of phagocytes and mobilizing intracellular Ca2+ (5, 17). Ceramides are key mediators in coordinating cellular responses and are generated via the sphingomyelinase pathway, which in turn is activated by the PLC product DAG (22). The PLD enzymatic activity in M. ulcerans may play a role in pathogenesis. PC hydrolysis by PLD leads to the production of PA, which may promote colonization of the tissues by the etiologic agent, induction of hemolytic activity, and apoptosis, as previously reported for Corynebacterium paratuberculosis (15, 16).

FIG. 1.

Autoradiograph of a thin-layer chromatography plate showing phospholipid hydrolysis products 1,2- and 1,3-DAG, PA, and phosphatidylethanol (PE) after incubation of WCE of the indicated mycobacterial strains with 14C-radiolabeled PC. Lane 1 (L1), M. tuberculosis 8171; lane 2, M. smegmatis 4995; lane 3, M. marinum 7732; lanes 4 to 9, M. ulcerans strains 94-511, 5150, 5146, 5142, 9146, and 94-1317, respectively.

Search for putative plc genes by PCR.

The design of degenerate primers was based on the comparison between sequences of the mpcA and mpcB genes from M. tuberculosis (GenBank accession no. U49511) (11) and genes encoding nonhemolytic (plcN) and hemolytic (plcH) PLC from P. aeruginosa (GenBank accession no. M59304 and M13047, respectively) (18, 19). The primers developed were PLC1 (5′-CGGACATTTGACNGAYAT-3′) (positions 135 to 152 of the sequence of mpcA) and PLC2 (5′-TGCTCGGGGTCGTTNACRCA-3′) (positions 355 to 374 of the sequence of mpcA), where N stands for A, G, C, or T; Y stands for C or T, and R stands for A or G.

One-microliter portions of mycobacterial crude lysates were subjected to PCR. PCRs were performed as previously described (8) for 35 amplification cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 1 min, annealing at 56°C for 45 s, and extension at 72°C for 1 min.

The PCR assay, using primers PLC1 and PLC2, amplified a DNA fragment of the expected size with all M. ulcerans strains, as well as with M. marinum, Mycobacterium bovis, and M. tuberculosis, for which plc genes are known (11). Although low annealing temperatures (56 to 46°C) were used, no specific amplification fragment was obtained with M. smegmatis, Mycobacterium fortuitum, and Mycobacterium gordonae.

DNA-DNA hybridization.

PCR products of 239 bp amplified with primers PLC1 and PLC2 from M. ulcerans 5150 were ligated into PCR II TOPO vector and cloned in Escherichia coli, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (InvitroGen, Leek, The Netherlands). The insert was isolated and purified from agarose gels after EcoRI restriction and electrophoresis, employing the GFX Gel Band Purification Kit (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech, Roosendael, The Netherlands), and used as a DNA probe for hybridization.

Genomic DNA extraction and PvuII digestion were performed as previously described by Hermans et al. (9). Probe labeling with horseradish peroxidase, hybridization, stringent washing, and development of the filters were performed with the ECL Direct Nucleic Acid Labeling and Detection kit, according to the instructions of the manufacturer (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech).

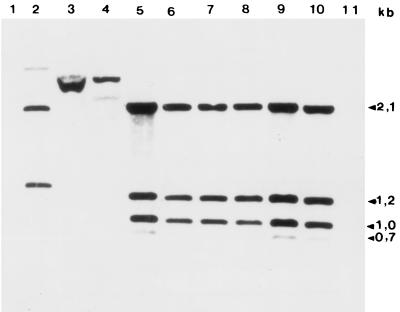

All M. ulcerans strains presented identical hybridization patterns, with four bands of 0.75, 1.0, 1.2, and 2.1 kbp (Fig. 2), (lanes 5 to 10). The DNAs of M. tuberculosis (Fig. 2, lane 4), M. bovis (lane 3), and M. marinum ATCC 927 (lane 2) hybridized with this probe. DNA from M. smegmatis did not hybridize with the probe (lane 1). Considering the size of the probe and the absence of a PvuII restriction site in the probe sequence, our hybridization pattern is compatible with the existence of at least two copies of plc genes in the M. ulcerans genome. This pattern is conserved in M. ulcerans strains from Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ivory Coast, and Australia.

FIG. 2.

Southern hybridization using the plc probe. Genomic DNA from each mycobacterial strain was digested with PvuII and probed with the plc probe. There is hybridization with M. marinum 7732 (lane 2), M. bovis 96-319 (lane 3), M. tuberculosis 8171 (lane 4), and M. ulcerans strains 5147, 94-1326, 5146, 94-511, 97-116, and 5150 (lanes 5 to 10, respectively). No hybridization is seen with M. smegmatis 4995 (lane 1). Lane 11, λ-HindIII DNA marker.

Partial sequencing of the putative M. ulcerans plc gene.

Sequencing of the insert was performed by the dideoxy-chain termination method of Sanger et al. (21), employing the ABI PRISM 377 DNA sequencer (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Comparison with published DNA sequences strongly suggests that the fragment amplified from M. ulcerans is part of a gene coding for the PLC enzyme. The highest level of identity, 75% in a 201-bp overlap, was obtained with a genomic sequence from M. bovis BCG Pasteur strain (accession no. BOY18606) (7). The M. tuberculosis H37Rv plcB, plcA, and plcC genes (accession no. Z83860) (1) and the genomic sequence from M. leprae (accession no. L78812) (3) have, respectively, 74, 72, 68, and 65% identity. The comparison also confirms homology with the plcN and plcH genes from P. aeruginosa (accession no. M59304 and M13047, respectively) (18, 19), with 56 and 47% identity, respectively. Amino acid sequence identity with the probe ranged between 74.6%, with the M. bovis BCG sequence, and 42.6%, with the sequence of the hemolytic PLC of P. aeruginosa.

This study demonstrates the presence of PLC and PLD enzymatic activities in both whole-cell cultures and CF of M. ulcerans. Whether or not PLC and PLD activities in CF represent secretion of the enzymes or spontaneous cell lysis needs further investigation. Detection of a PCR fragment from M. ulcerans genomic DNA that has a high degree of identity with the M. tuberculosis H37Rv plcB, plcA, and plcC genes provides the first evidence for putative genes coding for PLC in the necrotizing mycobacterium M. ulcerans. The function of putative M. ulcerans plc genes could be related to pathogenesis, as has been proposed for these plc genes in M. tuberculosis (4, 13). Whether or not PLC encoded by M. ulcerans genes plays a role in the pathogenesis of the disease is under study.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Colombian government grant COL/453 from Instituto Colombiano de la Ciencia y la Tecnologia-COLCIENCIAS and the Damien Foundation.

We thank Juan Carlos Palomino and Ivan Bastian for their helpful suggestions and Pim de Rijk for his technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cole S T, Brosch R, Parkhill J, et al. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dobos K M, Frederick D Q, Ashford D A, Horsburgh R C, King C H. Emergence of a unique group of necrotizing mycobacterial diseases. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999;5:367–378. doi: 10.3201/eid0503.990307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eiglmeier K, Honore N, Woods S A, Caudron B, Cole S T. Use of an ordered cosmid library to deduce the genomic organization of Mycobacterium leprae. Mol Microbiol. 1993;7:197–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1993.tb01111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fenton M J, Vermeulen W. Immunopathology of tuberculosis: roles of macrophages and monocytes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:683–690. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.3.683-690.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Firth J D, Putnins E E, Larjava H, Uitto V-J. Bacterial phospholipases C upregulates matrix metalloproteinase expression by cultured epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1998;65:4931–4936. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.4931-4936.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.George K M, Chatterjee D, Geewananda G, et al. Mycolactone: a polyketide toxin from Mycobacterium ulcerans required for virulence. Science. 1999;283:854–857. doi: 10.1126/science.283.5403.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gordon S V, Brosch R, Billault A, Garnier T, Eiglmeier K, Cole S T. Identification of variable regions in the genomes of tubercle bacilli using bacterial artificial chromosome arrays. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:643–655. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guimaraes-Peres A, Portaels F, Fonteyne P, et al. Comparison of two PCRs for detection of Mycobacterium ulcerans. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:206–208. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.1.206-208.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hermans P W M, Van Soolingen D, Dale J W, et al. Insertion elements IS986 from M. tuberculosis: a useful tool for diagnosis and epidemiology of tuberculosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:2051–2058. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.2051-2058.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hockmeyer W T, Krieg R E, Reich M, Johnson R D. Further characterization of Mycobacterium ulcerans toxin. Infect Immun. 1978;21:124–128. doi: 10.1128/iai.21.1.124-128.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Johansen K A, Ronald E G, Vasil L M. Biochemical and molecular analysis of phospholipase C and phospholipase D activity in mycobacteria. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3259–3266. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3259-3266.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson P D R, Stinear T P, Hayman H A. Mycobacterium ulcerans: a minireview. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:511–513. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-6-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King C H, Mundayoor S, Crawford J T, Shinnick T M. Expression of contact-dependent cytolytic activity by Mycobacterium tuberculosis and isolation of the genomic locus that encodes the activity. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2708–2712. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2708-2712.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leâo S C, Rocha C L, Murillo L A, Parra C A, Patarroyo M E. A species-specific nucleotide sequence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis encodes a protein that exhibits hemolytic activity when expressed in Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 1995;63:4301–4306. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.11.4301-4306.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McNamara P J, Bradley G A, Songer J G. Targeted mutagenesis of the phospholipase D gene results in decreased virulence of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:921–930. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McNamara P J, Cuevas W A, Songer J G. Toxic phospholipases D of Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis, C. ulcerans and Arcanobacterium haemolyticum: cloning and sequence homology. Gene. 1995;156:113–118. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00002-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monick M M, Carter A B, Gudmundsson G, Mallampalli R, Powers L S, Hunninghake G W. A phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C regulates activation of p42/44 mitogen-activated protein kinase in lipopolysaccharide-stimulated human alveolar macrophages. J Immunol. 1999;162:3005–3012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ostroff R M, Vasil A I, Vasil M L. Molecular comparison of a nonhemolytic and a hemolytic phospholipase C from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5915–5923. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.10.5915-5923.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pritchard A E, Vasil M L. Nucleotide sequence and expression of a phosphate-regulated gene encoding a secreted hemolysin of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:291–298. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.291-298.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Read J K, Heggie C M, Meyers W M, Connor D H. Cytotoxic activity of Mycobacterium ulcerans. Infect Immun. 1974;9:1114–1122. doi: 10.1128/iai.9.6.1114-1122.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanger F, Nicklen S, Coulson A R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1977;74:5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schwarzer N, Nöst R, Seybold J, et al. Two distinct phospholipases of Lysteria monocytogenes induce ceramide generation, nuclear factor-κB activation and E-selectin expression in human endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:3010–3018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tønjum T, Welty D B, Jatzen E, Small P L. Differentiation of Mycobacterium ulcerans, M. marinum and M. haemophilum: mapping of their relationships to M. tuberculosis by fatty acid profile analysis, DNA-DNA hybridization, and 16S RNA gene sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:918–925. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.4.918-925.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vincent Levy-Febrault V, Portaels F. Proposed minimal standards for the genus mycobacteria and for description of a new slowly growing Mycobacterium species. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:315–323. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-2-315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.World Health Organization. World Health Organization targets untreatable ulcer: report from the first International Conference on Buruli Ulcer Control and Research. Yamoussoukro, Ivory Coast: Inter Press Service; 1998. [Google Scholar]