Abstract

The health and care sector plays a valuable role in improving population health and societal wellbeing, protecting people from the financial consequences of illness, reducing health and income inequalities, and supporting economic growth. However, there is much debate regarding the appropriate level of funding for health and care in the UK. In this Health Policy paper, we look at the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and historical spending in the UK and comparable countries, assess the role of private spending, and review spending projections to estimate future needs. Public spending on health has increased by 3·7% a year on average since the National Health Service (NHS) was founded in 1948 and, since then, has continued to assume a larger share of both the economy and government expenditure. In the decade before the ongoing pandemic started, the rate of growth of government spending for the health and care sector slowed. We argue that without average growth in public spending on health of at least 4% per year in real terms, there is a real risk of degradation of the NHS, reductions in coverage of benefits, increased inequalities, and increased reliance on private financing. A similar, if not higher, level of growth in public spending on social care is needed to provide high standards of care and decent terms and conditions for social care staff, alongside an immediate uplift in public spending to implement long-overdue reforms recommended by the Dilnot Commission to improve financial protection. COVID-19 has highlighted major issues in the capacity and resilience of the health and care system. We recommend an independent review to examine the precise amount of additional funds that are required to better equip the UK to withstand further acute shocks and major threats to health.

Introduction

Since the National Health Service (NHS) was founded in the UK in 1948, public spending on health has more than doubled from 3·5% of gross domestic product (GDP) then to 7·2% in 2018–19.1, 2 In real terms, spending is more than 10 times the amount it was 70 years ago.1 Despite the scale of growth in health and care spending, there have been repeated crises, as funding increases have not kept pace with rising demand, expectations, or technological needs.3

In the decade preceding the COVID-19 pandemic, measures to cope with the gap between demand and funding for health care in the UK have included raiding funds intended for capital investment to boost revenue spending and restricting growth in staff pay, alongside announcements to increase public funding, such as the 2018 pledge to increase funding for the NHS in England by £20·5 billion per year in real terms by 2023–24,4 and the 2019 pledge to increase capital investment in the NHS in England by £1·8 billion.5

We argue that instead of short-term and reactive funding measures, a longer-term solution for both NHS and social care funding is necessary for a sustainable health and care service, which we define as a service that provides, as a minimum, similar levels of quality and access as are currently enjoyed, taking into account future trends in demography, morbidity, and technology. Increased investment is also needed to improve the preparedness and resilience of the health and care system to withstand acute shocks and major threats to health. Survey data indicate that, if funding for the NHS were to increase, the majority of the public would support tax increases.6 Public views on who should pay for social care are more nuanced, but more than half of people surveyed believe the government should pay, although perhaps only for individuals on low incomes.7

However, there needs to be increased clarity about the level of funding necessary for a sustainable health and care service. This Health Policy paper attempts to provide such clarity, while also being conscious of the considerable economic uncertainty created by the COVID-19 pandemic. Consequently, we begin with a discussion on the state of the economy and the potential economic impact of the recent COVID-19 pandemic. We then discuss the contribution of the health and care sector to wider society, health spending in the UK in comparison to other countries, trends in spending over time and across the UK, and the role of private spending on health. Finally, we assess the level of spending that is needed for a sustainable health and care service. All these topics are linked to the fiscal sustainability challenges identified by the Office for Budget Responsibility,8 and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).9

The economy and the COVID-19 pandemic

The social distancing measures implemented in response to the pandemic were necessary to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2 and limit excess mortality, but they have also closed down business activity in many sectors and had a striking impact on the UK's economic output. The Office for Budget Responsibility estimates that GDP in the UK fell by 9·9% in 2020, the largest decline out of all G7 countries.10 While the UK's rapid roll-out of vaccination creates the potential for the its economy to rebound quicker than those of many other nations, future growth is still highly dependent upon the effectiveness of vaccination in preventing any further waves of infections and associated lockdowns. However, at the time of writing, there is consensus among projections from the Office for Budget Responsibility, the OECD, and the Institute for Fiscal Studies, that GDP is expected to recover to pre-pandemic levels at some point in 2022.10, 11, 12 Future economic growth is also uncertain because of the UK leaving the EU. Most projections indicate that the growth of the UK economy will be smaller after leaving the EU than it would have been with continuing membership.13

Key messages.

-

•

According to estimates by the Office for Budget Responsibility, gross domestic product in the UK fell by 9·9% in 2020, the largest decline out of all G7 countries, while future growth is highly uncertain and dependent upon the effectiveness of vaccination in preventing any further waves of infections and associated lockdowns

-

•

Achieving increased health spending against this economic backdrop requires a combination of increased government borrowing in the short term and taxation in the medium-to-long term

-

•

There is a strong economic rationale to invest in the health and care sector, to improve health and societal wellbeing, and reduce health and income inequalities

-

•

In common with countries across the OECD, health spending in the UK has grown faster than the overall economy; however, growth in health and care spending has been highly volatile, with periods of relative plenty followed by periods of relative austerity

-

•

Spending volatility is not conducive to long-term planning and efficiency; to secure the long-term future of the National Health Service (NHS), there is a need for increased consensus regarding the right level of spending for health and care in the UK

-

•

Although responsibility for health and care delivery is devolved to the four nations, spending decisions in England affect Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland through proportional allocations set by the Barnett formula

-

•

Private spending on health plays a small role in the UK, and a major strength of the NHS is in providing protection against the financial consequences of ill health

-

•

For the NHS, to meet cost and demand pressures over the next 15 years, spending needs to grow on average by at least 3·3% per year in real terms; however, to improve the quality of services, reduce waiting times, increase staffing numbers, and invest in capital, spending will need to grow on average by at least 4% per year in real terms

-

•

For social care, to meet cost and demand pressures over the next 15 years, spending needs to grow on average by 3·9% per year in real terms; improving financial protection by introducing a means-tested threshold of £100 000 and a maximum contribution of £75 000 in England would require even more in social care spending

-

•

In the short term, a further uplift in public spending is needed to address the growing unmet need for health-care services caused by postponing or cancelling elective procedures and diagnostic tests during the pandemic

-

•

We also recommend an independent review to examine what additional funds are required to improve the preparedness and resilience of the health and care system to withstand further acute shocks and major threats to health

Combined with the impact of a weaker economy, the Office for Budget Responsibility's estimates that government borrowing reached £355 billion in 202010 represent the highest deficit since World War 2. However, there is consensus among economists that immediate reductions in public spending or acute rises in taxation would make the long-term situation worse.14, 15 Increased public spending is needed to support individuals and businesses through, for example, furlough pay, grants, and loans, and to mitigate against potential long-term effects on the economy from otherwise viable businesses failing and high and sustained unemployment. Moreover, the period of austerity preceding the pandemic left the health and care system under-resourced and vulnerable to an acute shock and major threats to health. This state of affairs ultimately exacerbated the economic impact of the pandemic itself and has reinforced the economic case for developing a resilient health and care system. Such a system will require the UK Government to place improving health and societal wellbeing at the heart of policy making and commit to sustained increases in health and care spending. While we acknowledge it will be challenging to achieve this shift in the current economic climate, we argue that it could be achieved through a combination of increased government borrowing in the short term and taxation in the medium-to-long term.

What is the contribution of the health and care sector to wider society?

The health and care sector is valuable: it improves the health and wellbeing of the population, reduces inequalities, and improves societal welfare. The sector also improves productivity and output through the associated increases in population health, which is especially important as the retirement age is increasing. Furthermore, the health and care sector is a large part of the economy, accounting for 4·5 million jobs in 2018 (approximately one in eight jobs in the UK and nearly one in six jobs in Wales).

Health spending and health outcomes

The contribution that health spending makes towards improving health outcomes has been difficult to establish because outcomes are influenced by a range of environmental, social, and economic factors beyond the health and care system. Moreover, analysis of historical trends is not necessarily a predictor of future trends. Nevertheless, some studies attempt to quantify the link between health system spending and health outcomes.16 Research using the concept of amenable mortality,17 now incorporated in the Health Access and Quality Index, has shown that effective and timely health care makes a substantial contribution to population health.18 Several analyses of NHS programme budgeting data show a clear link between increased health spending and improved health outcomes in the NHS, with the cost of securing an extra quality-adjusted life year ranging between £5000 and £15 000.19, 20, 21 At the macro level, an analysis of OECD countries concluded that increased health and care expenditure was associated with better health outcomes.22 The return on expenditure varies across countries, being lowest in the USA, partly because high prices mean that expenditure buys a lower volume of health care.23, 24 Research by the OECD in 2017 found that, across 35 member countries between 1995 and 2015, a 10% increase in health spending was associated with a life expectancy gain of 3·5 months,25 although no measures of uncertainty were included in the analysis. Some of these macro-level analyses overlook the fact that the effect of health spending on health outcomes is also dependent on how resources are allocated throughout the system. For example, investments in prevention might increase life expectancy more than those in end-of-life care, and investments in front-line services might improve health outcomes more than those in expensive drugs or medical devices. Therefore, as health systems continue to manage resources in a climate of resource scarcity, optimising allocative efficiency will be an essential strategy to maximise the health gains from health spending.

Health outcomes and economic growth

There is a growing literature focusing on the effect of improving health outcomes on macroeconomic growth and the mechanisms through which this occurs, although this is a challenging area in which to find causal evidence. Nevertheless, better health has been shown to increase labour market participation and worker productivity, which can increase economic growth.26 There is also evidence that increased life expectancy increases incentives to invest in education,27, 28 which in turn can improve productivity. Poor health during childhood has also been shown to be a predictor of worsened health in later life.29, 30 Therefore, as improved health can increase overall labour force participation, especially near to and after retirement age,31, 32 childhood health can have long-lasting effects on economic growth. Furthermore, illness and disability increase the likelihood of being unemployed in the UK,33 and being unwell at work (so-called presenteeism) is responsible for a considerable cost to the UK economy.34 The International Monetary Fund has also found evidence that providing increased access to health services can reduce the decline in total factor productivity and thus enhance economic growth from an ageing workforce.35 The COVID-19 pandemic has also shown the extreme effect that a health crisis can have on the economy.

Health spending, societal welfare, and inequality

Beyond the potential benefits for macroeconomic growth, well directed health and care expenditure improves overall societal welfare. For example, improved health in old age can reduce isolation and facilitate greater participation in society. The reverse is also true: care expenditure to reduce social isolation has health benefits.36, 37 People also derive utility from the knowledge that other people can access health care—a so-called caring externality.38 A key founding motivation for the NHS was that the sick deserve care, irrespective of their financial circumstances or contributions to the economy.39 While the NHS has been largely successful in providing care on the basis of clinical need and not ability to pay, there remain substantial inequalities in health outcomes. There is estimated to be a 7·4-year difference in life expectancy and an 18·9-year difference in healthy life expectancy between people in the highest and lowest deprivation deciles (appendix p 1). Although the UK has seen considerable increases in life expectancy, the rate of increase has slowed markedly since 2010 and, at some ages, reversed,40 an issue discussed further within the Health Policy paper on changing health needs linked to the main LSE–Lancet Commission report.41 However, it is important to emphasise the restricted influence of the health and care sector on health and wellbeing inequalities, which are strongly driven by a range of social determinants.42, 43 Nevertheless, it has been argued that the NHS often compensates when other parts of the social safety net fail.44

The NHS is funded through general taxation, which is largely progressive. Resources are also distributed using a needs-based resource allocation formula that reflects deprivation.45 Broadly, people on higher incomes subsidise people on lower incomes, and employed people subsidise unemployed people; in addition, because of the positive association between health and income, healthier individuals subsidise less healthy individuals,46 further reducing inequality.47, 48 The redistributive effect also depends on the utilisation of health care. Evidence from the NHS in England49 suggests that lifetime hospital costs are substantially higher in more deprived populations, thereby increasing the redistributive effect.

How does health spending in the UK compare with other countries?

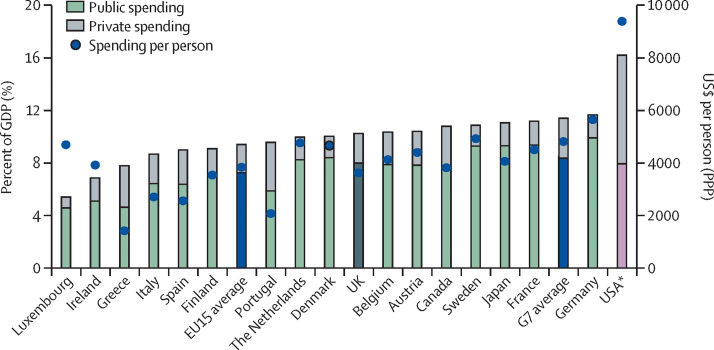

The UK spent 10·3% of GDP on health in 2019 (including both public and private spending), similar to the average of the EU15 group of countries (9·4% of GDP; figure 1 ). The highest-spending countries in the EU are Germany (11·7%), France (11·2%), and Sweden (10·9%). The UK spent less than the average of the G7 group of countries (11·5%), which includes the USA (17·0%). In 2018, 78% of health spending in the UK came from public funds—similar to the share in the EU15 (77%), but slightly above that in the G7 (73%). Public spending includes government spending or compulsory health insurance, whereas private spending includes any voluntary health insurance or out-of-pocket payments.50 The OECD definition of health spending includes aspects of long-term care that are conventionally understood as social care spending in the UK context.50

Figure 1.

Spending on health in G7 and EU15 countries (2019)

Source: Organisation for Economic Co-operation. GDP=gross domestic product. PPP=purchasing power parity. *Public–private split data for the USA is for 2013; although there are more recent data available, older data are used to provide comparable split with data from other countries.

Although total spending on health as a proportion of GDP in the UK is above the EU15 average, it is around 6% lower than the EU15 average in terms of $US per person ($3620 vs $3837; figure 1). Furthermore, the UK generally has relatively little capital, such as the number of hospital beds and diagnostic equipment, and a small workforce (eg, nurses and physicians; appendix p 2). Possible explanations for the low number of resources but similar spending levels to other comparable high-income countries could be differences in input prices (eg, physician wages),23 differences in skill mix (eg, greater reliance on non-clinical staff),51 or an ongoing shift towards moving care delivery from hospitals to the community.

International comparisons of health spending, capital, and workforce should be interpreted with caution. Data might not be comparable and contextual factors contribute to variations. For example, low numbers of hospital beds could reflect either a scarcity of capital investment or successful efforts to move care away from the hospital to community settings. Similarly, low numbers of physicians and nurses might reflect an understaffed workforce or different approaches to skill mix across health and care workers. It should be noted that, although the UK has comparatively lower numbers of clinical staff per person, such as nurses and physicians, the number of staff per person in the total health and care workforce is just above the average of EU15 and G7 countries (appendix p 2), which suggests that the UK makes greater use of skill mix (eg, non-clinical staff and allied health-care professionals).

How has health and care spending changed over time?

Public spending on health

Since the NHS was founded, spending has increased by more than inflation and GDP, rising by an average of 3·7% a year in real terms (appendix p 3).1 Three major factors determine the path of health spending over the long term: demographic factors, income effects, and other cost pressures.52 Demographic factors include the age structure of the population, health status at given ages, and death-related costs. Income effects reflect the fact that people generally demand more health care as their income rises. Other cost pressures include the effect of technological advancements and the increasing relative cost of health care. Over time, these factors have led health spending in the UK to increase at a faster rate than national income, which is consistent with the pattern seen across OECD countries.53

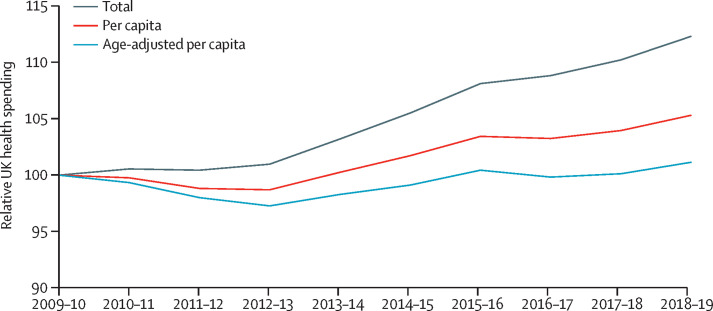

On only three occasions have there been notable spending reductions: twice in the early 1950s and in 1977–78 when the International Monetary Fund was called upon to support the UK economy. However, year-on-year spending growth has been highly volatile, with periods of relative plenty followed by periods of relative austerity. Between 1948 and 1978, spending increased on average by 3·5% a year. During the Conservative Governments of 1979 to 1997, spending growth was slightly lower, at 3·3% a year. Spending growth increased substantially under the Labour Governments between 1997 and 2009, averaging an increase of 6% a year.54 Between 2010 and 2018, health spending has grown at a markedly slower rate of just 1·2% a year (figure 2 ).54 The UK population has been increasing in size, so per-capita spending has been increasing at a slower rate than NHS expenditure. Moreover, the composition of the population has been changing and becoming older, meaning growth in age-adjusted spending is lower than growth in per-capita spending because older people tend to make greater use of health care. However, it is important not to overemphasise the contribution of population ageing, as individuals generally still see most health expenditure in their last year of life even as the population ages. It has been estimated that, independent of population ageing, cost growth and technological advancements will be the main drivers of future growth in health spending.56

Figure 2.

Index of real UK health spending after 2009–10

Total, per-capita, and age-adjusted per-capita spending in 2009–10 each take the value 100. Data are from the UK Government Public Expenditure Statistics Analyses,2 Office for Budget Responsibility,55 and Office for National Statistics.

Public spending on social care

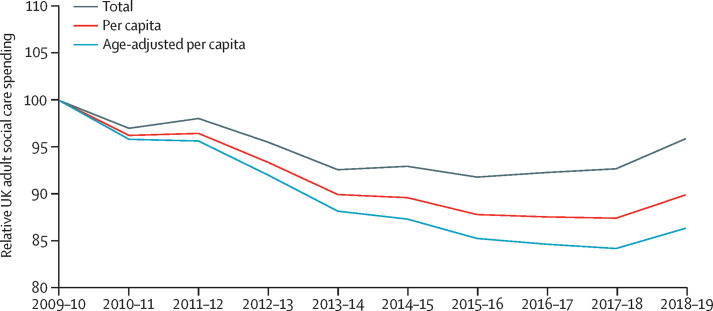

The health and care sectors are linked, and many ill people require support from both. If health and care services are complementary, reduced spending on social care might put greater pressure on the health sector, and vice versa. While spending on adult social care has been reduced in real terms during the past decade, the reduction is significantly larger when adjusted for per-capita and age-adjusted per-capita spending (figure 3 ).

Figure 3.

Index of real UK adult social care spending after 2009–10

Total, per-capita, and age-adjusted per-capita spending in 2009–10 each take the value 100. Data are from the UK Government Public Expenditure Statistics Analyses,2 Office for Budget Responsibility,55 and Office for National Statistics.

How does health and care spending vary across the UK?

Public spending on health across the UK

The funding systems in each of the four countries of the UK remain tax-based and free at the point of use, with divergence in the use of prescription charges (see the role of private spending below). Publicly funded health spending per person varies across the four UK countries (appendix p 4). Total funding allocations to each UK country for government spending are based on a combination of historical spending and the Barnett formula, which proportionally adjusts any uplift in government spending in England according to population size to Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland.57 Each UK nation then decides how to allocate its resources during annual spending reviews. Within England, around two-thirds of the NHS budget is allocated via weighted capitation payments (ie, predefined payments per head of the population calculated to reflect expected need for health care) to local commissioning bodies, taking account of population factors such as age, gender, and deprivation.45 Public spending on health per person is highest in Scotland and lowest in England (appendix p 4). However, there are regions in England, such as the northeast and London, with higher spending per person than that in Scotland. Differences across the UK in spending per person have narrowed, ranging from £1598–£2471 in 2010–11 to £1915–£2665 in 2017–18 (appendix p 4). This trend warrants further investigation, as it is not clear if demographic changes in relative need between regions are responsible or if other contributory factors exist.

Once allocated to local commissioning bodies in England, an internal market exists whereby both the NHS and independent-sector hospitals are eligible to provide treatment for NHS patients. In 2017–18, independent-sector hospitals provided over 600 000 publicly funded elective procedures—6% of all NHS elective activity—growing from less than 2000 elective procedures in 2003–04.58 For some procedures such as hip replacements, independent-sector hospitals now provide 30% of all NHS-funded procedures.58 Analyses indicate that such reforms, despite less complex patients being treated in the independent care sector, might have improved access and outcomes.59, 60 However, concerns have been raised regarding a relative absence of transparency in independent-sector hospitals61 and the potential impact on the sustainability of NHS services.62 During the pandemic, independent-sector hospitals have been used to allow the continuation of NHS cancer treatment and elective procedures in facilities that have low exposure to COVID-19.63

Public spending on social care across the UK

The constituent countries of the UK are responsible for social care within their jurisdictions, leading to variation in eligibility criteria and differences in patterns of both funding and delivery. For example, in Scotland, personal and nursing care are free, whereas, in England, all social care is means-tested (appendix p 5). Means-testing can lead to substantial costs incurred by older people needing social care support—the 2011 Dilnot Commission on social care in England found that one in ten people, at age 65, would face future lifetime care costs of £100 000.64

Social care spending per adult is 31% lower in England than in Scotland, where there is a system of free personal care for older people (appendix p 5). Although differences between the four UK nations might reflect differences in eligibility criteria and needs, they also reflect the larger cuts to social care in England since 2011 (appendix p 5). The Institute for Fiscal Studies estimated that between 2009–10 and 2017–18, councils in the most deprived areas made cuts to adult social care of 17% per person, compared with cuts of 3% per person in councils in the least deprived areas.65 These differences in social care eligibility and funding across the UK do not appear to have influenced preparedness against COVID-19, as all constituent countries experienced significantly increased excess mortality in care homes during the pandemic.66, 67, 68

What is the role of private spending on health in the UK?

There is no developed country in which private spending is the predominant financing mechanism for health-care services (figure 1). Even in the USA, which has a more extensively privatised financing model, there is still a significant public system to provide coverage for low-income, older, and veteran populations. Indeed, despite substantial private financing, public spending in the USA still accounts for a higher percentage of GDP than it does in the UK (figure 1). Notably, countries with more privatised models have higher inequalities in access to health-care services,69 a lower redistributive effect between income groups,46 and a higher incidence of catastrophic health expenditure.70

In the UK, private spending on health is a little more than a fifth of all spending.54 However, most of the private spending on health is concentrated among individuals in the highest income quintile,71 with those in the lowest income quintile typically exempt from out-of-pocket payments to access NHS services.72, 73 Generally, a major strength of the NHS compared with health-care systems in other high-income countries is financial protection, evidenced by a comparatively low incidence of catastrophic health expenditure, which is defined as out-of-pocket payments for health-care services exceeding a certain proportion of household income (appendix p 3). Factors that influence the level of financial protection in any country include gaps in coverage, the frequency and size of out-of-pocket payments, and whether coverage policy is designed in a manner that minimises out-of-pocket payments for people on low-incomes and regular users of health-care services.74

Household health expenditure accounts for a little less than 70% of private spending in the UK and includes both direct purchases of medical goods and services by households and treatment funded through voluntary health insurance.75 Overall, payments for pharmaceuticals (copayments and over-the-counter payments) make up 34% of household health expenditure, followed by therapeutic appliances and equipment (20%), hospital services (18%), dental services (12%), and outpatient medical services (10%).75 Prescription charges apply only in England (although about 90% of prescriptions are exempt from charges), having been abolished in Wales in 2007, Northern Ireland in 2010, and Scotland in 2011.76 Inequality in unmet need follows income patterns and is greater for dental care than it is for medical care, with people in the lowest income quintile consistently more likely to report unmet need for dental care due to cost, distance, or waiting times than people in the highest income quintile.77

In addition to out-of-pocket expenditure, there is voluntary health insurance for both dental and general health plans. In 2016, 10·5% of the UK population had some form of voluntary health insurance; 8% through employer-paid schemes and 2·5% through individually paid schemes.78 The numbers insured fell slightly following the recession in 2008 but have now stabilised, although there has been a gradual decrease in the number of individually paid subscribers.78 The share of households with voluntary health insurance varies substantially by income quintile, with more than 20% of those in the highest income quintile and less than 5% of those in the lowest income quintile having voluntary health insurance.77 There is also considerable variation regionally, with nearly half of the share of UK spending on voluntary health insurance concentrated in London and the southeast (appendix p 6).

What level of spending is needed in the future for a sustainable health and care service?

Projections of health spending

Projections of health spending are essential to understand the level of spending needed in the future for a sustainable health and care service. These projections need to take into account the goals of the health system, such as maintaining quality and access to a range of services in line with public expectations. Several bodies, such as the Office for Budget Responsibility and the OECD, produce top-down projections of health spending for the UK and other countries (table ). Such projections involve focusing on the three main drivers of health spending, categorised as demographic factors, income effects, and other cost pressures.80 The Institute for Fiscal Studies with the Health Foundation and the Institute for Public Policy Research both have produced bottom-up projections of health, which are populated with component-based data, such as drug costs, provider activity, and salaries (table). These projections were all made before the COVID-19 pandemic and thus do not factor in the consequences of the pandemic or additional funding required for preparedness to withstand further acute shocks and major threats to health. Arguably, the bottom-up projections better capture factors relevant to the UK than the top-down projections and consequently provide more robust forecasts. This approach does, however, require significantly more country-specific data than the top-down approach, making it less feasible if projecting expenditure for many different countries. However, synergies can be identified between the top-down and bottom-up approaches, and both approaches take account of long-term projections of GDP growth, produced by organisations such as the Office for Budget Responsibility81 and the OECD.82

Table.

Selected projections of public spending on health in the UK

| Baseline expenditure (% of GDP) | Annual real growth | Projected expenditure (% of GDP) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-down projections | |||

| OECD (cost-containment) | 6·5% (2010) | Not calculated | 7·9% (2030; 1·4% increase) |

| OECD (constant cost-pressure) | 6·5% (2010) | Not calculated | 8·4% (2030; 1·9% increase) |

| Office for Budget Responsibility | 7·1% (2017–18) | Not calculated | 9·9% (2037–38; 2·8% increase) |

| Bottom-up projections | |||

| Health Foundation with the Institute for Fiscal Studies (status quo) | 7·3% (2018–19) | 3·3% (2033–34) | 8·9% (2033–34; 1·6% increase) |

| Health Foundation with the Institute for Fiscal Studies (modernised scenario) | 7·3% (2018–19) | 4·0% (2033–34) | 9·9% (2033–34; 2·6% increase) |

| Institute for Public Policy Research (England) | Not calculated (2016–17) | 3·8% (2029–30) | Not calculated |

Alongside demographic and income effects, top-down projections are particularly affected by alternative cost pressure scenarios, which take account of assumptions related to input prices (ie, labour, goods and services, and fixed capital), technological advances, and policy changes. The Office for Budget Responsibility and OECD projections assume that health-care sector productivity is lower than that of the rest of the economy. This difference is partially due to the Baumol effect,83 which suggests that wages in labour-intensive industries such as the health-care sector must keep pace with wages in sectors with higher productivity potential. The significance of the Baumol effect is debated,84 although both the OECD and the Office for Budget Responsibility assume there is a Baumol effect for health care, with pay increasing faster than productivity growth. The Baumol effect is often cited as contributing to rising health spending, although Baumol himself reflected that such increased spending on health is neither necessarily unsustainable nor problematic as long as that spending is seen to be valued by society.85 The relationship between technological advances and health spending is also complex and often conflicting:86 in different cases, technology can increase costs, be cost-neutral, or even save costs. However, even if a technology is cost-saving, overall health expenditure might increase as the new technology allows expansion of treatment, increasing treatment volume, and therefore increasing overall expenditure. Therefore, there is considerable uncertainty regarding to what degree technology will increase costs in the future.

The effect of cost pressures is challenging to forecast and, not surprisingly, results in large variability in projections.52 The OECD produces a cost-containment scenario, which assumes that changes in policy act more strongly than in the past to rein in some of the expenditure growth, and an alternative scenario (the cost-pressure scenario), which assumes that cost pressures continue at 1·7% a year, the average historical growth across all countries in the OECD. The cost-containment scenario projects spending for the UK to increase by 1·4% of GDP, whereas the cost-pressure scenario projects an increase of 1·9% of GDP by 2030. The Office for Budget Responsibility's projection draws upon a 2015–16 NHS England estimate of non-demographic cost pressures of 2·7% per year for primary care and 1·2% per year for secondary care.56 The projections assume these pressures will decline over time to 1% per year from 2036–37 onwards. The rationale for this assumption is that this decline might be expected as health spending takes up an even larger share of national income. This approach projects an increase of 2·6% of GDP in health spending by 2037–38.

The Institute for Fiscal Studies and Health Foundation bottom-up projections use two alternative scenarios. The status-quo scenario takes account of core demand and cost pressures but does not provide sufficient funding to return waiting times to their target levels, support improvements to quality and outcomes, or modernise the physical infrastructure of the health service. This scenario projects an annual real growth rate of 3·3% for the UK and public spending of 8·9% of GDP by 2033–34. The alternative scenario by the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Health Foundation returns the NHS to previous levels of care quality and allows improvement in key priority areas of unmet need, including Accident and Emergency performance, waiting times for elective care, outpatient appointments, mental health, capital spending, and public health. This scenario projects an annual average real growth rate of 4% and public spending of 9·9% of GDP by 2033–34.1 Further areas of unmet need are identified in other accompanying LSE–Lancet Commission background papers, such as those on the health and care workforce51 and health information technology.87 The 4% growth rate is also broadly consistent with the other bottom-up projections from the Institute for Public Policy Research, which also uses a bottom-up methodology and projects a real annual growth rate of around 3·8%.82

When analysing these approaches together, some conclusions can be made. Top-down projections show that assumptions related to input prices, technological advances, and policy changes significantly affect future estimates of health spending. From bottom-up projections, there is a broad consensus that health spending needs to increase by 3·3–4% per year in real terms. However, if we are to seek improvements in the quality of NHS care rather than oversee gradual reductions in quality of care, increases need to average at least 4% per year in real terms. Further evidence to support such increases in health spending is contained in our background paper on the health and care workforce,51 which estimates that increases in health spending of 4% per year in real terms are necessary to sustain growth in the workforce at 2·3% per year. However, it is important to note that these top-down projections were done before the COVID-19 pandemic and assume that GDP growth will increase on average by 1·9% per year until 2033–34.1 Therefore, these projections give an indication of the level of spending required for a long-term funding settlement for the NHS, assuming GDP growth in the long term returns to pre-pandemic projections. In the short term, further increases in public spending will continue to be needed for the NHS to respond to the pandemic and address the growing unmet need for health-care services caused by postponing or cancelling elective procedures and diagnostic tests. We also recommend an independent review to examine what additional funds are required to improve the preparedness and resilience of the health and care system to withstand further acute shocks and major threats to health.

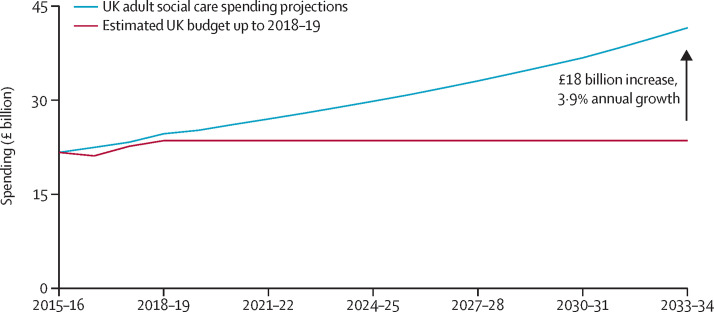

Projections of social care spending

With current eligibility criteria maintained, projections from the Personal Social Services Research Unit (now known as the Care Policy and Evaluation Centre), adapted by the Institute for Fiscal Studies and Health Foundation, conclude that public funding for social care needs to increase by 3·9% per year until at least 2033 to meet demand (figure 4 ). These projections estimate future demand for adult social care by including projections of population size, age, gender, prevalence of disability, and future expenditure by projecting the rising cost of providing social care services. Included in the expenditure projections is the assumption that health and social care costs rise in real terms in line with productivity, with an uplift to take account of the planned rises in the national living wage.88

Figure 4.

UK social care spending projections

Source: Institute for Fiscal Studies and Health Foundation,1 and the Personal Social Services Research Unit.1, 88

It is also important to note that reform of the social care model is long overdue. In England and Northern Ireland, current eligibility criteria and thresholds have remained unchanged since 2010–11, which has contributed to more than 400 000 fewer people accessing publicly funded social care in England in 2016−17 than in 2009−10, despite growing needs associated with population ageing.89 Future public social care spending will be dependent upon whether and how social care funding is reformed. Different options have been explored to reach a long-term funding settlement for social care. The Dilnot Commission on Fairer Care Funding suggested a lifetime cap of individual contributions of £35 000 and a means-tested threshold of £100 000.64 The government responded by initially suggesting the introduction of a lifetime cap for individual contributions of £75 000, although this cap has been postponed indefinitely.90 The 2017 Conservative election manifesto proposed implementing a means-tested threshold of £100 000, as suggested by the Dilnot Commission.91 The 2019 Conservative manifesto recommitted to the concept of improved financial protection,92 but no reform has taken place to date. No matter what reform is introduced for social care, a guiding principle should be to increase financial protection, so a substantial increase in public funding is likely to be required. For example, it has been estimated that implementing a means-tested threshold of £100 000 and a lifetime cap of £75 000 on individual contributions in England alone would cost an additional £3·2 billion, according to 2018–19 prices.93

Productivity and health spending

Any claims made for increased spending on health or social care will need to come with the assurance that these funds will be put to good use. Such an assessment is most commonly established by measuring productivity, which compares the amount of output produced against the inputs used by any particular sector of the economy. In the health-care sector, outputs are measured by taking account of factors such as the number of hospital patients treated as elective cases, day cases, or emergency admissions, and the number of outpatient contacts in primary care, mental health, and community trusts.94 These outputs are cost-weighted and quality-adjusted using indicators such as patient-reported outcome measures, waiting times, survival in hospital settings, and the quality and outcomes framework in primary care.94 Health outcomes such as life expectancy are not considered as outputs, as these are not wholly attributable to the health-care sector. Health-care inputs include the number of doctors, nurses, and support staff providing care, the equipment and clinical supplies used, and the hospitals and other premises where care is provided.94 If growth in output exceeds growth in input, health-care productivity increases. However, productivity might increase if inputs are cut.

The rate of productivity growth in the health-care sector since the early 2000s compares favourably with that achieved by other public sectors and the economy as a whole.95 However, the NHS, like the economy as a whole, faces challenges in continuing to make productivity gains.96 There are concerns that positive past productivity growth will not persist into the future. Past productivity gains might have been achieved by restricting growth in staffing levels, implying that existing staff have been working harder at a time when wage growth up to 2018–19 was limited to 1% per year—such a position is not sustainable. To retain staff and keep them motivated, especially in a situation of reduced immigration, wages will have to increase in line with economy-wide average earnings. For social care, reductions in productivity might be due to the high turnover of low-paid staff employed in a sector characterised by weak employment conditions, which itself reflects an increasing mismatch between funding and current demand. Low wages and reduced bed availability have negatively affected morale and left providers not capable of improving productivity.

Staff also need the right equipment and technology to do their jobs. It has long been recognised that many of the more productive companies are those that have invested more heavily in capital and technology,97 a process termed capital deepening.98 But in recent years, the NHS has experienced the reverse; capital funds have been raided to fund hospital deficits, leading to a backlog in maintenance and poor investment in technology.99 Capital investment per NHS worker has fallen in real terms by 17% between 2010–11 and 2017–18.100 This decline will need to be rectified to secure future productivity growth. Looking forward, working existing inputs harder will not be enough. It will be essential that the NHS becomes better at reducing inefficiency and unwarranted variations in practice.

Conclusion

This Health Policy paper has covered a series of policy questions, and several conclusions can be drawn. The health and care sectors undeniably play a valuable role in improving population health and societal wellbeing, reducing health and income inequalities, and supporting economic growth. The UK has witnessed a large increase in health spending since the NHS was established, but growth in spending has slowed significantly in recent years. The UK spends around the average of the EU15, but still less than many other comparable high-income nations. Real-term funding for social care has decreased in recent years, which has implications for the NHS because the two sectors are inextricably linked. Within the UK, there is variation in health and care spending, with Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland all spending more per person than England does. The role of private spending also varies considerably and is concentrated in high-income groups, particularly in London and the southeast. We conclude that, for a sustainable health and care service, public spending on the NHS and social care will need to increase on average by at least 4% per year in real terms. An independent review is needed to estimate the additional funds required to improve the preparedness and resilience of the health and care system to withstand acute shocks and major threats to health. The pandemic will be responsible for a substantial recession that creates challenges to sustaining increases in health and care spending. It must be remembered that the NHS was established shortly after World War 2, during one of the most economically challenging times the UK has endured. The foundations for today's social care system were also laid at that time. As then, the NHS and social care will be integral to the recovery of the economy and society in general.

Declaration of interests

We declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

Funding for the LSE–Lancet Commission on the future of the NHS was granted by the LSE Knowledge and Exchange Impact (KEI) fund, which was created using funds from the Higher Education Innovation Fund (HEIF). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report.

Contributors

AC led the working group that prepared the paper. AC, MA, and MW drafted the paper. MA and MW managed the processes of the working group, compiled the data and graphics, and contributed to editing. All other authors provided critical input into the content and revisions to the text.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Charlesworth A, Johnson P. Securing the future: funding health and social care to the 2030s. May 24, 2018. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/12994

- 2.HM Treasury Public expenditure statistical analyses 2019. July 18, 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/public-expenditure-statistical-analyses-2019

- 3.Mossialos E, McGuire A, Anderson M, Pitchforth E, James A, Horton R. The future of the NHS: no longer the envy of the world? Lancet. 2018;391:1001–1003. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30574-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UK Government Prime Minister sets out 5-year NHS funding plan. June 18, 2018. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/prime-minister-sets-out-5-year-nhs-funding-plan

- 5.UK Government PM announces extra £1.8 billion for NHS frontline services. Aug 5, 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/news/pm-announces-extra-18-billion-for-nhs-frontline-services

- 6.The King's Fund Does the public see tax rises as the answer to NHS funding pressures? April 12, 2018. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/does-public-see-tax-rises-answer-nhs-funding-pressures

- 7.Wood C, Vibert S. A good retirement: public attitudes to the role of the state and the individual in achieving financial security in later life. December, 2017. https://www.demos.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/A-Good-Retirement.pdf

- 8.Office for Budget Responsibility Fiscal risks report. July, 2019. https://obr.uk/docs/dlm_uploads/Fiscalrisksreport2019.pdf

- 9.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Fiscal sustainability of health systems. Sept 24, 2015. https://www.oecd.org/publications/fiscal-sustainability-of-health-systems-9789264233386-en.htm

- 10.Office for Budget Responsibility Economic and fiscal outlook: March 2021. March 3, 2021. https://obr.uk/efo/economic-and-fiscal-outlook-march-2021/

- 11.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development OECD economic outlook, volume 2020, issue 1: preliminary version. June 10, 2020. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/oecd-economic-outlook/volume-2020/issue-1_0d1d1e2e-en

- 12.Emerson C, Nabarro B, Stockton I. The outlook for the public finances under the long shadow of COVID-19. June 4, 2020. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/BN295-The-outlook-for-the-public-finances-under-the-long-shadow-of-COVID-19-2.pdf

- 13.Tetlow G, Stojanovic A. Understanding the economic impact of Brexit. October, 2018. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/2018%20IfG%20%20Brexit%20impact%20%5Bfinal%20for%20web%5D.pdf

- 14.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Tax and fiscal policy in response to the coronavirus crisis: strengthening confidence and resilience. May 19, 2020. https://www.oecd.org/ctp/tax-policy/tax-and-fiscal-policy-in-response-to-the-coronavirus-crisis-strengthening-confidence-and-resilience.htm

- 15.International Monetary Fund Policies for the Recovery. Oct 14, 2020. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2020/09/30/october-2020-fiscal-monitor

- 16.Figueras J, Mckee M. Open University Press; Berkshire, UK: 2012. Health systems, health, wealth and societal well-being: assessing the case for investing in health systems. European Observatory on Health Systems and Policies. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nolte E, McKee M. Variations in amenable mortality—trends in 16 high-income nations. Health Policy. 2011;103:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2011.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fullman N, Yearwood J, Abay SM, et al. Measuring performance on the Healthcare Access and Quality Index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;391:2236–2271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin S, Rice N, Smith PC. Does health care spending improve health outcomes? Evidence from English programme budgeting data. J Health Econ. 2008;27:826–842. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2007.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Claxton K, Martin S, Soares M, et al. Methods for the estimation of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence cost-effectiveness threshold. Health Technol Assess. 2015;19:1–503. doi: 10.3310/hta19140. v–vi. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lomas J, Martin S, Claxton K. Estimating the marginal productivity of the English National Health Service From 2003 to 2012. Value Health. 2019;22:995–1002. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2019.04.1926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bradley EH, Elkins BR, Herrin J, Elbel B. Health and social services expenditures: associations with health outcomes. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20:826–831. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs.2010.048363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papanicolas I, Woskie LR, Jha AK. Health care spending in the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:1024–1039. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baicker K, Chandra A. Challenges in understanding differences in health care spending between the United States and other high-income countries. JAMA. 2018;319:986–987. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.James C, Devaux M, Sassi F. Inclusive growth and health. Dec 19, 2017. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/paper/93d52bcd-en

- 26.Bloom DE, Canning D, Kotschy R, Prettner K, Schünemann JJ. Health and economic growth: reconciling the micro and macro evidence. June, 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w26003.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Bloom DE, Canning D, Sevilla J. RAND Corporation; Santa Monica, CA: 2003. The demographic dividend: a new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cervellati M, Sunde U. Life expectancy, schooling, and lifetime labor supply: theory and evidence revisited. Econometrica. 2013;81:2055–2086. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Palloni A, Milesi C, White RG, Turner A. Early childhood health, reproduction of economic inequalities and the persistence of health and mortality differentials. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1574–1582. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Case A, Fertig A, Paxson C. The lasting impact of childhood health and circumstance. J Health Econ. 2005;24:365–389. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2004.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Blundell RW, Britton J, Costa Dias M, French E. The impact of health on labor supply near retirement. August, 2017. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/wps/WP201718.pdf

- 32.Kanabar R. Post-retirement labour supply in England. J Econ Ageing. 2015;6:123–132. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Office for National Statistics Adult health in Great Britain, 2013. March 19, 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthandlifeexpectancies/compendium/opinionsandlifestylesurvey/2015-03-19/adulthealthingreatbritain2013

- 34.Garrow V. Presenteeism: a review of current thinking. February, 2016. https://www.employment-studies.co.uk/system/files/resources/files/507_0.pdf

- 35.Aiyar MS, Ebeke C, Shao X. The impact of workforce aging on European productivity. December, 2016. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16238.pdf

- 36.Valtorta NK, Kanaan M, Gilbody S, Ronzi S, Hanratty B. Loneliness and social isolation as risk factors for coronary heart disease and stroke: systematic review and meta-analysis of longitudinal observational studies. Heart. 2016;102:1009–1016. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2015-308790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Courtin E, Knapp M. Social isolation, loneliness and health in old age: a scoping review. Health Soc Care Community. 2017;25:799–812. doi: 10.1111/hsc.12311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Culyer AJ. The nature of the commodity ‘health care’ and its efficient allocation. Oxf Econ Pap. 1971;23:189–211. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan M, Shackley P. Assessing the benefits of health care: how far should we go? Qual Health Care. 1995;4:207–213. doi: 10.1136/qshc.4.3.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leon DA, Jdanov DA, Shkolnikov VM. Trends in life expectancy and age-specific mortality in England and Wales, 1970–2016, in comparison with a set of 22 high-income countries: an analysis of vital statistics data. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e575–e582. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30177-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McKee M, Dunnell K, Anderson M, et al. The changing health needs of the UK population. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00229-4. published online May 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Whitehead M, Dahlgren G. What can be done about inequalities in health? Lancet. 1991;338:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(91)91911-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair society healthy lives (the Marmot review) February, 2010. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review

- 44.Rajan S, McKee M. NHS is picking up the pieces as social safety nets fail. BMJ. 2019;365 doi: 10.1136/bmj.l2360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.NHS England Technical guide to allocation formulae and pace of change: for 2019/20 to 2023/24 revenue allocations. May 30, 2019. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/allocations-2019-20-technical-guide-to-formulae-v1.1.pdf

- 46.van Doorslaer E, Wagstaff A, van der Burg H, et al. The redistributive effect of health care finance in twelve OECD countries. J Health Econ. 1999;18:291–313. doi: 10.1016/s0167-6296(98)00043-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.HM Revenues and Customs HMRC tax receipts and national insurance contributions for the UK. 2019. https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/hmrc-tax-and-nics-receipts-for-the-uk

- 48.Miller H, Pope T. The changing composition of UK tax revenues. April, 2016. https://www.ifs.org.uk/uploads/publications/bns/BN_182.pdf

- 49.Asaria M, Doran T, Cookson R. The costs of inequality: whole-population modelling study of lifetime inpatient hospital costs in the English National Health Service by level of neighbourhood deprivation. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70:990–996. doi: 10.1136/jech-2016-207447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Eurostat. WHO A system of health accounts 2011. 2017. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/9789264270985-en

- 51.Anderson M, O'Neill C, Macleod Clark J, et al. Securing a sustainable and fit-for-purpose UK health and care workforce. Lancet. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00231-2. published online May 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Office for Budget Responsibility Fiscal sustainability and public spending on health. Sept 21, 2016. http://obr.uk/fsr/fiscal-sustainability-analytical-papers-july-2016/

- 53.Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Public spending on health and long-term care: a new set of projections. June, 2013. https://www.oecd.org/eco/growth/Health%20FINAL.pdf

- 54.Office for National Statistics Healthcare expenditure, UK Health Accounts: 2018. April 28, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/bulletins/ukhealthaccounts/2018

- 55.Office for Budget Responsibility Fiscal sustainability report: July 2018. July 17, 2018. https://obr.uk/fsr/fiscal-sustainability-report-july-2018/

- 56.Jayawardana S, Cylus J, Mossialos E. It's not ageing, stupid: why population ageing won't bankrupt health systems. Eur Heart J Qual Care Clin Outcomes. 2019;5:195–201. doi: 10.1093/ehjqcco/qcz022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Keep M. The Barnett formula. Jan 23, 2020. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7386

- 58.Stoye G. Recent trends in independent sector provision of NHS-funded elective hospital care in England. Nov 22, 2019. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/14593

- 59.Kelly E, Stoye G. The impacts of private hospital entry on the public market for elective care in England. J Health Econ. 2020;73 doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2020.102353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gutacker N, Street A. Multidimensional performance assessment of public sector organisations using dominance criteria. Health Econ. 2018;27:e13–e27. doi: 10.1002/hec.3554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson M, Cherla A, Wharton G, Mossialos E. Improving transparency and performance of private hospitals. BMJ. 2020;368:m577. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.British Medical Association Independent sector provision in the NHS revisited. January, 2019. https://www.bma.org.uk/media/1984/bma-privatisation-of-the-nhs-in-england-jan-2019.pdf

- 63.Richards M, Anderson M, Carter P, Ebert BL, Mossialos E. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on cancer care. Nat Cancer. 2020;1:565–567. doi: 10.1038/s43018-020-0074-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dilnot A. Fairer care funding: the report of the commission on funding of care and support. July, 2011. https://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20130221121529/https://www.wp.dh.gov.uk/carecommission/files/2011/07/Fairer-Care-Funding-Report.pdf

- 65.Phillips D, Simpson P. Changes in councils' adult social care and overall service spending in England, 2009–10 to 2017–18. June 13, 2018. https://www.ifs.org.uk/publications/13066

- 66.Office for National Statistics Deaths involving COVID-19 in the care sector, England and Wales. July 3, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/articles/deathsinvolvingcovid19inthecaresectorenglandandwales/deathsoccurringupto12june2020andregisteredupto20june2020provisional

- 67.National Records of Scotland Deaths involving coronavirus (COVID-19) in Scotland. https://www.nrscotland.gov.uk/statistics-and-data/statistics/statistics-by-theme/vital-events/general-publications/weekly-and-monthly-data-on-births-and-deaths/deaths-involving-coronavirus-covid-19-in-scotland

- 68.Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency Weekly deaths. https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/weekly-deaths

- 69.van Doorslaer E, Masseria C, Koolman X. Inequalities in access to medical care by income in developed countries. CMAJ. 2006;174:177–183. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wagstaff A, Flores G, Hsu J, et al. Progress on catastrophic health spending in 133 countries: a retrospective observational study. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6:e169–e179. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30429-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Office for National Statistics Detailed household expenditure by gross income quintile group, UK, financial year ending 2015 to financial year ending 2017. July 24, 2018. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/personalandhouseholdfinances/expenditure/adhocs/008735detailedhouseholdexpenditurebygrossincomequintilegroupukfinancialyearending2015tofinancialyearending2017

- 72.King D, Mossialos E. The determinants of private medical insurance prevalence in England, 1997–2000. Health Serv Res. 2005;40:195–212. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00349.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Foubister T, Thomson S, Mossialos E, McGuire A. Cromwell Press; Trowbridge, UK: 2006. Private medical insurance in the United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thomson S, Cylus J, Evetovits T. Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in Europe. 2019. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/311654/9789289054058-eng.pdf

- 75.Office for National Statistics Expenditure on Healthcare in the UK: 2013. March 26, 2015. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/healthandsocialcare/healthcaresystem/articles/expenditureonhealthcareintheuk/2015-03-26

- 76.Parkin E, Bate A, Loft P. NHS charges. March 26, 2020. https://researchbriefings.parliament.uk/ResearchBriefing/Summary/CBP-7227

- 77.O'Dowd NC, Kumpunen S, Holder H. Can people afford to pay for health care? New evidence on financial protection in the United Kingdom. 2018. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0010/373690/uk-fp-report-eng.pdf?ua=1

- 78.Blackburn P. 13th edition. LaingBuisson; London, UK: 2017. Health cover UK market report. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Darzi A. The Lord Darzi review of health and care: interim report. April 25, 2018. https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/darzi-review-interim-report

- 80.Office for Budget Responsibility Drivers of rising health spending. Sept 11, 2017. http://obr.uk/box/drivers-of-rising-health-spending/

- 81.Office for Budget Responsibility Economic and fiscal outlook: March 2019. March 13, 2019. https://obr.uk/efo/economic-fiscal-outlook-march-2019/

- 82.Johansson Å, Guillemette Y, Murtin F, et al. Long-term growth scenarios. Jan 28, 2013. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/economics/long-term-growth-scenarios_5k4ddxpr2fmr-en

- 83.Baumol WJ, Bowen WG. MIT Press; Cambridge, MA: 1968. Performing arts: the economic dilemma—a study of problems common to theater, opera, music and dance. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Colombier C. Drivers of health care expenditure: does Baumol's cost disease loom large? FiFo Discussion Paper No. 12–5. Oct 17, 2013. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=2341054

- 85.Baumol WJ. Social wants and dismal science: the curious case of the climbing costs of health and teaching. Proc Am Philos Soc. 1993;137:612–637. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Sorenson C, Drummond M, Bhuiyan Khan B. Medical technology as a key driver of rising health expenditure: disentangling the relationship. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res. 2013;5:223–234. doi: 10.2147/CEOR.S39634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Sheikh A, Anderson M, Albala S, et al. Health information technology and digital innovation for national learning health and care systems. Lancet Digit Health. 2021 doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(21)00005-4. published online May 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wittenberg R, Hu B, Hancock R. Projections of demand and expenditure on adult social care 2015 to 2040. June 19, 2018. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/88376/

- 89.Nuffield Trust. The Health Foundation. The King's Fund The Autumn Budget: Joint statement on health and social care. November, 2017. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/the-autumn-budget

- 90.UK Government Care Act 2014: cap on care costs and appeals. Feb 4, 2015. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/care-act-2014-cap-on-care-costs-and-appeals

- 91.Mckenna H. The parties' pledges on health and social care. May 24, 2017. https://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/general-election-manifesto-pledges

- 92.The Conservative and Unionist Party Our plan: Conservative manifesto 2019. 2019. https://vote.conservatives.com/our-plan

- 93.Watt T, Varrow M, Charlesworth A, et al. Social care funding options. May, 2018. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/social-care-funding-options

- 94.Castelli A, Chalkley MJ, Gaughan JM, et al. Productivity of the English National Health Service: 2016/17 update. April 15, 2019. http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/145037/

- 95.Office for National Statistics Public service productivity: total, UK, 2017. Jan 8, 2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/economicoutputandproductivity/publicservicesproductivity/articles/publicservicesproductivityestimatestotalpublicservices/totaluk2017

- 96.Dixon J, Street A, Allwood D. Productivity in the NHS: why it matters and what to do next. BMJ. 2018;363 doi: 10.1136/bmj.k4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Bloom N, Sadun R, Van Reenen J. Americans do IT better: US multinationals and the productivity miracle. Am Econ Rev. 2012;102:167–201. [Google Scholar]

- 98.Kumar S, Russell RR. Technological Change, technological catch-up, and capital deepening: relative contributions to growth and convergence. Am Econ Rev. 2002;92:527–548. [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kraindley J, Firth Z, Charlesworth A. False economy: an analysis of NHS funding pressures. May, 2018. https://www.health.org.uk/sites/default/files/False-economy-NHS-funding-pressures-May-2018.pdf

- 100.Kraindler J, Gershlick B, Charlesworth A. Failing to capitalise: capital spending in the NHS. March, 2019. https://www.health.org.uk/publications/reports/failing-to-capitalise

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.