Abstract

Creeping fat (CrF), also known as fat wrapping, is a significant disease characteristic of Crohn's disease (CD). The transmural inflammation impairs intestinal integrity and facilitates bacteria translocation, aggravating immune response. CrF is a rich source of pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrotic cytokines with complex immune microenvironment. The inflamed and stricturing intestine is often wrapped by CrF, and CrF is associated with greater severity of CD. The large amount of innate and adaptive immune cells as well as adipocytes in CrF promote fibrosis in the affected intestine by secreting large amount of pro‐fibrotic cytokines, adipokines, growth factors and fatty acids. CrF is a potential therapeutic target for CD treatment and a promising bio‐marker for predicting response to drug therapy. This review aims to summarize and update the clinical manifestation and application of CrF and the underlying molecular mechanism involved in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation and fibrosis in CD.

Keywords: bacteria translocation, creeping fat, Crohn's disease, free fatty acids metabolism, intestinal fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Mesenteric adipose tissue (MAT) hypertrophy, also known as fat wrapping or creeping fat (CrF), is a hall‐marker of Crohn's disease and was firstly reported by Dr. Burrill B. Crohn himself to be a unique feature of the disease. 1 The relationship between mesentery and intestine derives from embryological development. The mesenteric mesoderm surrounded by the intestinal endoderm promotes development of the intestine with cellular and connective tissue contributions. 2 , 3 This pathobiological relationship is retained until adulthood and this is now accepted to be implicated in the pathological alteration in Crohn's disease. The inflamed and stricturing intestine is often wrapped by CrF, and CrF is associated with the clinical activity of CD and inflammation severity. 4 , 5 The pre‐inflammatory, fibrotic nature of CrF and the protective effect from transmural inflammation expansion endow CrF “dual role” in the pathogenesis of Crohn's disease. Of note, CrF is primarily seen in the small bowel, and most often the ileum, but not in ulcerative colitis, the other form of inflammatory intestinal diseases. 6 CrF has now been recognized as an anatomical marker for surgeons to determine the margin of resection during surgery. 7 It has also been found that mesentery‐based surgery for CD is associated with improved postoperative long‐term outcome. 8

The adipose tissue is composed of a large variety of cell types, including mature adipocytes, endothelial cells, fibroblasts, pre‐adipocytes, stem cells and immune cells. Remarkably, the adipocytes only make up 20%~40% of the cellular content, and the number of the stromal vascular cells are 2~3 times over adipocytes. 9 In circumstance of CD, both non‐immune and immune cellular lineages are notably increased in CrF. 10 , 11

CrF has been proved as a rich source of TNF, IL‐6, IL‐10 and other pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrotic cytokines. 12 In CD, the integrity of intestinal barrier is impaired and this facilitates bacteria antigen translocation, resulting in subsequent Th17 and Th1 responses. 13 Th1 response is a hallmark of CD, with downstream secretion of IL‐22, IL‐1, IFN‐γ, IL‐2 and other soluble cytokines. 14 As a matter of fact, Th1 cells predominate in CrF as compared to which in mucosa, whereas the mucosa demonstrates higher infiltration of Th17 cells against bacterial infection. Notably, it contains higher amount of M2 than M1 cells in CrF, in contrast to the lamina propria where M1 are more common. 15 , 16 The M2 preferential polarization might promote fibrosis in the affected intestine by secreting large amount of pro‐fibrotic cytokines. The complex immune microenvironment in CrF and the crosstalk with inflamed intestine play an important role in the pathogenesis and disease progression of CD.

Moreover, adipocytes themselves are capable of exerting an important effect on neighboring cells and regulating immune response via fat‐derived autocrine, paracrine and endocrine molecules. 17 Adipokines secreted by adipocytes, such as adiponectin, leptin and apelin, are demonstrated to be immune modulators in CD. 18 In addition to adipokines, free fatty acids (FFAs), which are secreted by adipocytes and the relevant fatty acid metabolism pathways, have aroused great interest among researchers. However, the role of FFAs in the pathogenesis and the underlying mechanism have not been fully investigated in the status of CD. Our recent study has found that impaired fatty acid desaturation exists in CrF. The relevant lipid mediator FADS2 in mesenteric adipocytes orchestrates local immune response and contributes to the chronic inflammation in CD. 19

In this narrative review, we will discuss the crosstalk between bacteria and CrF formation and their impact on the disease behavior of CD. Imaging and clinical implication of CrF are summarized to investigate the interaction between CrF and disease prognosis. Recent studies and progress on this topic will also be reviewed to investigate the underlying molecular mechanism and potential therapeutic target.

BACTERIA AND CrF FORMATION

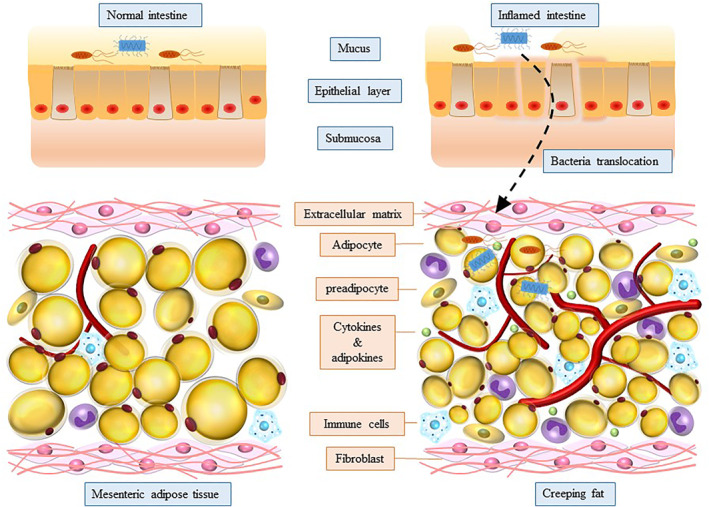

Damaged integrity of intestinal barrier facilitates gut‐derived bacteria translocation (Figure 1). It has been demonstrated that up to 27% CD patients (vs. 13% healthy controls) had bacteria translocation to mesenteric fat and this has been also observed in experimental colitis and ileitis. 20 CrF presents microbiome signature enriched in Proteobacteria 21 and C. innocuum, 22 and the relative abundance of bacteria in CrF can be altered with the clinical status of CD. Additionally, lymph flow plays an important role in transporting bacteria antigens and immune cells. 23 One possibility related to the discussion of lymphatic vessels is that CrF is driven by the spillage into the mesentery of the fatty chylomicrons carried in lymph by highly permeable or leaky lymphatic vessels. 24 , 25 Indeed, our study confirmed that the hypertrophy of MAT may result from mispatterned and ruptured lymphatic system. 26 Enhancing integrity and pumping function of lymphatics could alter inflammation of MAT which further verified that leaky antigens activated inflammatory response and adipogenesis of MAT. 27 Actually, single cell RNA sequence characterized CrF as both pro‐fibrotic and pro‐adipogenic with a rich milieu of activated immune cells responding to microbial stimuli. 22 Pattern recognition receptor, such as Toll‐like receptors, 28 and nucleotide‐oligomerization domain‐containing proteins (NOD) 29 mediates inflammatory response and adipogenesis in adipocytes and pre‐adipocytes, which are key to IBD. All TLRs except TLR5, TLR7 30 , 31 and two NODs (NOD1 and NOD2) 32 are expressed by adipocytes and preadipocytes which make them respond to microbial molecules. NOD1 activation significantly suppressed 3T3‐L1 adipocyte differentiation and lipid accumulation. 29 PRR‐mediated secretion of TNF‐α and IL‐6 also impair cell differentiation in preadipocytes. 33 , 34 Meanwhile, LPS, which derived from Gram‐negative bacteria, directly participates in the inflammatory reaction in the adipose tissue through TLR‐4 signaling pathway activation. 35 Large adipocytes are more metabolically active and more likely stimulated to cell death by processes that involve LPS from the gut microbiota. 36 The factors aforementioned explained why there are large amounts of immature, small‐size adipocytes with poor lipid accumulation in the MAT, which is a critical character of CrF in CD. Interestingly, it has been demonstrated that there is a strong correlation between adipocyte size and extent of macrophage infiltration in white adipose tissue (WAT). 37

FIGURE 1.

Bacteria translocation and components in creeping fat (CrF)

Adipose tissue expansion with the presence of smaller adipocytes have been confirmed in several transgenic mouse models of metabolically healthy obesity. Our cohort study revealed that mesenteric adipocyte dysfunction was associated with hypoxia in CD. 38 As we know, hypoxia induces cellular mitochondrial dysfunction. 39 Mitochondrial dysfunction subsequently enables preadipocytes adopt a macrophage‐like inflammatory phenotype with increased expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokines and decreased adipogenic capacity in response to inflammatory stimuli. 40 Reprograming of mitochondrial metabolism drives preadipocytes preferentially differentiate to fibro‐inflammatory progenitors and induces impaired adipogenesis and adipose tissue fibrosis. 41 Meanwhile, WNT and TGF‐β/SMAD3 signaling pathway are significantly elevated in CrF in CD, and both of which are most established examples for suppression of adipogenesis. 42 , 43 The paradox is the pathologic adipose tissue expansion of CrF. The key molecule for activation of adipogenesis is peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor‐γ (PPARγ) and CCAAT/enhancer‐binding protein‐α (C/EBPα), and the PPARγ‐C/EBPα complex formation facilitates preadipocytes differentiation. 44 , 45 As we have aforementioned, Th1 cells predominate in CrF with upregulated secretion of IL‐22, IL‐1, IFN‐γ, IL‐2 and other soluble cytokines, and these pro‐inflammatory cytokines were suppressed by PPARγ. 46 Overexpression of PPARγ has been demonstrated in CrF, 12 which supports the fact that PPARγ actively participates in the lipogenesis and adipogenesis process in CrF. Interestingly, PPARγ also involves in adipokines secretion by increasing adiponectin and suppressing resistin. 47 Adiponectin in turn promotes the nuclear receptor expression involved in PPARγ signaling pathway. 48 , 49 The complex regulation mechanism of CrF formation involves multiple factors and needs further investigation.

CrF AND INTESTINAL INFLAMMATION

CrF is composed of immune cells and non‐immune cells, and both of which are markedly increased in CrF compared to healthy controls. 10 , 50 CrF is a rich source of pro‐inflammatory and anti‐inflammatory cytokines and adipokines, as well as chemokines, which actively participate in the onset of intestinal inflammation. The transformed CrF contains large amount of macrophages, NK cells and T‐cells. 51 Among these immune cells, Th1 cells predominate in CrF as compared to which in mucosa, whereas the mucosa demonstrates higher infiltration of Th17 cells against bacterial infection. 15 , 51 Notably, it contains higher amount of M2 than M1 cells in CrF, in contrast to the lamina propria where M1 are more common. 15 , 16 Interestingly, anti‐TNF treatment notably decreased the infiltration of immune cells and the gene expression of antigen‐presenting markers of adipose tissue macrophages, as well as the gene expression of pro‐inflammatory cytokine (IL1β, IL‐6, TNF‐α). 52 T‐cell subpopulations differed between CrF and the corresponding mucosa. Comparing fat and mucosa, the total percentage of Th1, Th17 and Treg populations were significantly higher within CrF than in the mucosa in ileal CD patients. 53 Meanwhile, CD8+ central memory cells (TCM), normally representing the memory population in lymph nodes, were demonstrated having a higher tendency in the fat tissue than mucosa. Of note, the proportion of Th17 cells infiltration in CrF had a negative correlation with disease activity. 53 These results suggest that there is unique immune cell signature in CrF, which is a potential bio‐marker for CD diagnosis and disease activity prediction. Furthermore, innate lymphoid cells (ILCs, including ILC1, ILC2 and ILC3) are innate counterparts of CD4+ T‐cells (Th1, Th2, Th17) by secreting a range of cytokines favouring effector T‐cell responses. 54 Among which, ILC2s are distributed in visceral adipose tissue and orchestrate the eosinophil and M2 macrophage recruitment in adipose tissue by secretion of IL‐4, IL‐5 and IL‐13. 55 , 56 The interaction between ILCs and other immune cells in CrF need to be addressed with further investigation.

CrF has its own cytokine and adipokine signature, which shapes immune cells compartment and polarization in CrF and exerts further influence on intestinal inflammatory profiles. It has been proved that CrF is an important source of pro‐inflammatory cytokines, such as TNF‐α, IL‐1β, and IL‐6, and approximately 30% circulating IL‐6 is secreted by WAT. 57 CrF‐related IL‐6 levels reflected the clinical response during steroid therapy and could predict clinical relapse after steroid‐induced remission. 58 The overexpression of IL‐10 contradicts the pro‐inflammatory profile of CrF, which orchestrates Treg response and plays an essential role in IFN‐γ‐secreting CD4+ T‐cells. 11 , 59 Meanwhile, adipokines stem from the MAT also actively participate in the gut immune response. Leptin (an adipokine with pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrotic nature) is mainly secreted by WAT and regulates the differentiation, function and metabolism of a variety of immune cells' subpopulations and intestinal epithelial cells. 60 , 61 , 62 On the contrary, the overexpression of adiponectin in CrF presents anti‐inflammatory effect based on the antagonistic effect of TNF‐α 63 and inhibits the expression of adhesion molecules, metalloproteinases, and proinflammatory mediators. 64 Other adipokines, such as chemerin, ghrelin, resistin and visfatin, also play an important role in regulating immune homeostasis in mesentery and the adjacent intestine. 65 The complex immune microenvironment in CrF and the crosstalk with inflamed intestine play an important role in the pathogenesis and disease progression of CD.

CrF AND INTESTINAL STRICTURE

Intestinal stricture is challenging in the management of CD. More than one‐third CD patients develop stenotic disease phenotype and need at least one surgical intervention. 66 However, there are no specific anti‐fibrogenic agents to reverse the process. Although the molecular mechanism of the intestinal stricture formation remains unclear, it is well recognized that strictures are resulted from transmural inflammation and tissue repairing. The abnormal deposition of extracellular matrix (ECM) induced by immune cells, non‐immune cells and microenvironmental factors leads to hyperplasia of connective tissue, tissue remodeling, and ultimately intestinal fibrosis. 67 The presence of fat wrapping surrounding the inflamed intestine is closely associated with muscularis propria hyperplasia and stricture formation. It has been shown that the extent of serosal fat wrapping correlates significantly with the degree of acute and chronic inflammation, especially the transmural inflammation. 68 In a consecutive and unselected group of 27 performed on 25 patients with CD, fat wrapping was identified in 12 of 16 ileal resections and in 7 of 11 colon resections. Fat wrapping was found to be associated with connective tissue changes including fibrosis, muscularization and stricture formation. 69 A recent study developed a novel mesenteric creeping fat index (MCFI) using computed tomography (CT) in CD patients, MCFI showed an excellent correlation with extent of fat wrapping and could accurately differentiate the degree of intestinal fibrosis. 70 The current accumulated results suggest that CrF is a potential bio‐marker for prediction of stenotic phenotype disease extent in CD.

Basic character for intestinal fibrogenesis is excessive ECM deposition, which is comparable to fibrogenesis in other organs. Multiple soluble factors produced by immune cells and non‐immune cells during an inflammatory response promote fibrogenesis. For instance, the M2 preferential polarization in CrF might promote fibrosis in the affected intestine by secreting large amount of pro‐fibrotic cytokines such as TGF‐β. TGF‐β is an important mediator of fibrogenesis through activating mesenchymal cells, which is also capable of regulating immune response by inducing regulatory T cells (T‐reg). Other fibrogenic‐related molecules include connective tissue growth factor, activins, insulin‐like growth factors 1 and 2, platelet‐derived growth factors, and others. The activation of the downstream signaling pathway of these molecules directly results in fibrogenesis. In addition to the classic molecules, CrF‐derived FFAs has aroused great interest among researchers in recent years. The CrF‐derived FFAs induce specific proliferative response by human intestinal fibroblast and human intestinal muscle cells. Our study demonstrated that the metabolism of lysophospholipids was mispatterned in MAT from CD patients. 19 Impaired desaturation fluxes towards the n−6 and n−3 pathways was observed in the levels of metabolites involved in the synthesis of long‐chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs). The metabolic dysfunction was shown to be regulated by fatty acid desaturase‐2 (FADS2). The disturbance of fatty acid desaturation with decreased FADS2 expression contributes to chronic inflammation in CD. We further confirmed that the disturbed expression of the enzymes which are involved in the lipid metabolism, in CrF from CD. Among which, the activation of autotaxin (ATX) and lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) axis promoted proliferation and differentiation of fibroblasts and aggravated intestinal fibrosis. 71 Although the mechanism of fibrogenesis is still unclear in IBD, the reversibility of stricturing seems promising. Clinical observations suggest that intestinal fibrosis is not a one‐way street. The intestinal wall thickness was significantly reduced with strictureplasty for CD patients. Additionally, a large pipeline of anti‐fibrotic drugs is stepping into clinical trials for organ fibrosis, such as for the kidney, lung, liver, heart and skin.

CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF CrF

Surgeons harness CrF as an anatomical marker to determine the surgical margin of intestinal resection. 7 In a cohort study, Coffey et.al showed that the surgical recurrence rate was significantly lower in the group which underwent intestinal resection with excision of the mesentery, compare to the control group undergoing conventional ileocolic resection where mesentery was divided flush with the intestine (2.9% vs. 40%). 8 These results demonstrate that inclusion of mesentery in ileocolic resection for CD is associated with reduced recurrence requiring reoperation, which further suggests the pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrotic profile of CrF in the pathogenesis of gut inflammation. Meanwhile, advanced mesenteric disease correlated with increased surgical recurrence, and the mesenteric disease activity was closely associated with the mucosal disease activity index. Our recent report indicated that, in patients with Crohn's colitis, extensive mesenteric excision is associated with similar short‐term outcomes and improved long‐term outcomes compared to limited mesenteric excision. 72 However, some old data showed the radical operation with excised mesentery for CD led to early relapse compared to more restricted procedure. 73 Taken the fact that CrF is a protective factor against transmural inflammation and bacterial translocation, more randomized clinical trials are needed to find out whether CrF is a friend or foe for CD treatment.

On the meantime, clinical manifestation of CrF can predict the intestinal disease activity to some extent. A recent research established a novel CrF index (MCFI) based on vascular finding on CT, and validated the efficiency of MCFI in a prospective cohort. 70 The results found that MCFI could accurately differentiate intestinal fibrosis severity, while neither visceral to subcutaneous fat area ratio nor fibrofatty proliferation score correlated well with the degree of gut fibrosis. This is interesting and has clinical implication as identifying CrF or fat wrapping on imaging is of great significance and this method could be used as a non‐invasive method to evaluate the severity and extent of gut inflammation and fibrogenic alteration. Of note, the mesenteric fat alteration or lymphadenopathies may be of great value to evaluate the response to drug therapy. The existing research has already used these two parameters to assess the early and long‐term therapeutic efficiency in patients starting treatment with anti‐TNF agents. 74 Based on MRE data, another prospective longitudinal study showed that the presence of CrF was an independent negative predictor of long‐term healing of severe inflammation in clinically active CD patients requiring anti‐TNF drugs. 75 These results suggest CrF as valuable predictor for assessing therapeutic effect with biological treatment in CD patients.

Targeting CrF is an interesting and promising research going. We have discussed that CrF formation and pathological alteration are associated with lymph leakage. Our preliminary study demonstrated that targeting mesenteric lymphatics with chylomicrons‐simulating nanoparticles could restore the microstructure of leaky mesenteric lymphatic vessels and notable alter pathologic inflammatory cells infiltration in the mesenteric fat. 27 This study contributed the firsthand reliable pharmacokinetics data in the mesentery in experimental colitis. In fact, intraperitoneal administration with anti‐TNF increased the production of IL‐10 and resistin in mesenteric fat and significantly restored the morphology of adipocytes and upregulated PPAR‐γ expression. 76 These results suggest that targeting CrF and exploring more therapeutic targets will shed light on developing alternative treating method for CD patients.

CONCLUSION

CrF as a hallmark of CD actively participates in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation. Given its protective nature, CrF formation is responsive to the transmural inflammation and microorganism stimuli translocation. However, the pro‐inflammatory and pro‐fibrogenic profiles of CrF promote ECM deposition and intestinal fibrogenesis. Therefore, it is suggested that CrF determines the surgical margin for intestinal resection and is used to predict the severity of gut fibrosis on imaging. Despite the clinical manifestations, the underlying mechanism for CrF formation and the molecule interaction between CrF and pathological alteration of the inflamed intestine are not fully clarified and worth further investigation. We do believe that with deeper understanding on the immune microenvironment, endocrine function and metabolism characterization of CrF, more and more potential therapeutic target and agents will be mined out which will shed light on the alternative choice for CD treatment.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Yi Yin, and Ying Xie, were involved in drafting of the manuscript; Wei Ge, and Yi Li, were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors agree the final approval of the version to be published.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The authors declare no conflict of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

No funding was obtained for this study.

Yin Y, Xie Y, Ge W, Li Y. Creeping fat formation and interaction with intestinal disease in Crohn's disease. United European Gastroenterol J. 2022;10(10):1077–84. 10.1002/ueg2.12349

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Crohn BB, Ginzburg L, Oppenheimer GD. Regional ileitis; a pathologic and clinical entity. Am J Med. 1952;13(5):583–90. 10.1016/0002-9343(52)90025-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Coffey JC, O'Leary DP. The mesentery: structure, function, and role in disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;1(3):238–47. 10.1016/s2468-1253(16)30026-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Byrnes KG, Walsh D, Dockery P, McDermott K, Coffey JC. Anatomy of the mesentery: current understanding and mechanisms of attachment. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2019;92:12–7. 10.1016/j.semcdb.2018.10.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li Y, Zhu W, Gong J, Shen B. The role of the mesentery in crohn's disease. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(4):244–5. 10.1016/s2468-1253(17)30036-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Feng Q, Xu XT, Zhou Y, Yan YQ, Ran ZH, Zhu J. Creeping fat in patients with ileo‐colonic crohn's disease correlates with disease activity and severity of inflammation: a preliminary study using energy spectral computed tomography. J Dig Dis. 2018;19(8):475–84. 10.1111/1751-2980.12652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kredel LI, Siegmund B. Adipose‐tissue and intestinal inflammation – visceral obesity and creeping fat. Front Immunol. 2014;5:462. 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00462 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Althoff P, Schmiegel W, Lang G, Nicolas V, Brechmann T. Creeping fat assessed by small bowel MRI is linked to bowel damage and abdominal surgery in crohn's disease. Dig Dis Sci. 2019;64(1):204–12. 10.1007/s10620-018-5303-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Coffey CJ, Kiernan MG, Sahebally SM, Jarrar A, Burke JP, Kiely PA, et al. Inclusion of the mesentery in ileocolic resection for crohn's disease is associated with reduced surgical recurrence. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(10):1139–50. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kanneganti TD, Dixit VD. Immunological complications of obesity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13(8):707–12. 10.1038/ni.2343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gonçalves P, Magro F, Martel F. Metabolic inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease: crosstalk between adipose tissue and bowel. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(2):453–67. 10.1097/mib.0000000000000209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Schäffler A, Fürst A, Büchler C, Paul G, Rogler G, Scholmerich J, et al. Secretion of rantes (ccl5) and interleukin‐10 from mesenteric adipose tissue and from creeping fat in crohn's disease: regulation by steroid treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;21(0):1412–8. 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04300.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Desreumaux P, Ernst O, Geboes K, Gambiez L, Berrebi D, Muller‐Alouf H, et al. Inflammatory alterations in mesenteric adipose tissue in crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1999;117(1):73–81. 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70552-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cobrin GM, Abreu MT. Defects in mucosal immunity leading to crohn's disease. Immunol Rev. 2005;206(1):277–95. 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00293.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Li N, Shi RH. Updated review on immune factors in pathogenesis of crohn's disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24(1):15–22. 10.3748/wjg.v24.i1.15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kredel LI, Jödicke LJ, Scheffold A, Grone J, Glauben R, Erben U, et al. T‐cell composition in ileal and colonic creeping fat – separating ileal from colonic crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2019;13(1):79–91. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lissner D, Schumann M, Batra A, et al. Monocyte and m1 macrophage‐induced barrier defect contributes to chronic intestinal inflammation in ibd. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1297–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. What we talk about when we talk about fat. Cell. 2014;156(1‐2):20–44. 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Batra A, Zeitz M, Siegmund B. Adipokine signaling in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15(12):1897–905. 10.1002/ibd.20937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Liu R, Qiao S, Shen W, Liu Y, Lu Y, Liangyu H, et al. Disturbance of fatty acid desaturation mediated by fads2 in mesenteric adipocytes contributes to chronic inflammation of crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(11):1581–99. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Peyrin‐Biroulet L, Gonzalez F, Dubuquoy L, Rousseaux C, Dubuquoy C, Decourcelle C, et al. Mesenteric fat as a source of c reactive protein and as a target for bacterial translocation in crohn's disease. Gut. 2012;61(1):78–85. 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Serena C, Queipo‐Ortuño M, Millan M, Sanchez‐Alcoholado L, Caro A, Espina B, et al. Microbial signature in adipose tissue of crohn's disease patients. J Clin Med. 2020;9(8):2448. 10.3390/jcm9082448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ha CWY, Martin A, Sepich‐Poore GD, Shi B, Wang Y, Gouin K, et al. Translocation of viable gut microbiota to mesenteric adipose drives formation of creeping fat in humans. Cell. 2020;183(3):666–83.e17. 10.1016/j.cell.2020.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dongaonkar RM, Nguyen TL, Quick CM, Hardy J, Laine GA, Wilson E, et al. Adaptation of mesenteric lymphatic vessels to prolonged changes in transmural pressure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2013;305(2):H203–10. 10.1152/ajpheart.00677.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Randolph GJ, Miller NE. Lymphatic transport of high‐density lipoproteins and chylomicrons. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(3):929–35. 10.1172/jci71610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Randolph GJ, Bala S, Rahier JF, Johnson MW, Wang PL, Nalbantoglu I, et al. Lymphoid aggregates remodel lymphatic collecting vessels that serve mesenteric lymph nodes in crohn disease. Am J Pathol. 2016;186(12):3066–73. 10.1016/j.ajpath.2016.07.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shen W, Li Y, Zou Y, Cao L, Cai X, Gong J, et al. Mesenteric adipose tissue alterations in crohn's disease are associated with the lymphatic system. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2019;25(2):283–93. 10.1093/ibd/izy306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Yin Y, Yang J, Pan Y, Guo Z, Gao Y, Huang L, et al. Chylomicrons‐simulating sustained drug release in mesenteric lymphatics for the treatment of crohn's‐like colitis. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(4):631–46. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjaa200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cario E. Toll‐like receptors in inflammatory bowel diseases: a decade later. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16(9):1583–97. 10.1002/ibd.21282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Purohit JP, Hu P, Burke SJ, Collier JJ, Chen J, Zhao L. The effects of nod activation on adipocyte differentiation. Obesity. 2013;21(4):737–47. 10.1002/oby.20275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cario E, Podolsky DK. Differential alteration in intestinal epithelial cell expression of toll‐like receptor 3 (tlr3) and tlr4 in inflammatory bowel disease. Infect Immun. 2000;68(12):7010–7. 10.1128/iai.68.12.7010-7017.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kopp A, Buechler C, Neumeier M, Weigert J, Aslanidis C, Scholmerich J, et al. Innate immunity and adipocyte function: ligand‐specific activation of multiple toll‐like receptors modulates cytokine, adipokine, and chemokine secretion in adipocytes. Obesity. 2009;17(4):648–56. 10.1038/oby.2008.607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Stroh T, Batra A, Glauben R, Fedke I, Erben U, Kroesen A, et al. Nucleotide oligomerization domains 1 and 2: regulation of expression and function in preadipocytes. J Immunol. 2008;181(5):3620–7. 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3620 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yu L, Liu G, Yang C, Song X, Wang H. Polyinosinic‐polycytidylic acid inhibits the differentiation of mouse preadipocytes through pattern recognition receptor‐mediated secretion of tumor necrosis factor‐α. Immunol Cell Biol. 2016;94(9):875–85. 10.1038/icb.2016.57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gustafson B, Smith U. Cytokines promote wnt signaling and inflammation and impair the normal differentiation and lipid accumulation in 3t3‐l1 preadipocytes. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(14):9507–16. 10.1074/jbc.m512077200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hoch M, Eberle AN, Peterli R, Peters T, Seboek D, Keller U, et al. Lps induces interleukin‐6 and interleukin‐8 but not tumor necrosis factor‐alpha in human adipocytes. Cytokine. 2008;41(1):29–37. 10.1016/j.cyto.2007.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Hersoug LG, Møller P, Loft S. Role of microbiota‐derived lipopolysaccharide in adipose tissue inflammation, adipocyte size and pyroptosis during obesity. Nutr Res Rev. 2018;31(2):153–63. 10.1017/s0954422417000269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Weisberg SP, McCann D, Desai M, Rosenbaum M, Leibel RL, Ferrante AW. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112(12):1796–808. 10.1172/jci200319246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zuo L, Li Y, Zhu W, Shen B, Gong J, Guo Z, et al. Mesenteric adipocyte dysfunction in crohn's disease is associated with hypoxia. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2016;22(1):114–26. 10.1097/mib.0000000000000571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Fearon U, Canavan M, Biniecka M, Veale DJ. Hypoxia, mitochondrial dysfunction and synovial invasiveness in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2016;12(7):385–97. 10.1038/nrrheum.2016.69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Isakson P, Hammarstedt A, Gustafson B, Smith U. Impaired preadipocyte differentiation in human abdominal obesity: role of wnt, tumor necrosis factor‐alpha, and inflammation. Diabetes. 2009;58:1550–7. 10.2337/db08-1770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Joffin N, Paschoal VA, Gliniak CM, Crewe C, Elnwasany A, Szweda LI, et al. Mitochondrial metabolism is a key regulator of the fibro‐inflammatory and adipogenic stromal subpopulations in white adipose tissue. Cell Stem Cell. 2021;28(4):702–17.e8. 10.1016/j.stem.2021.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ross SE, Hemati N, Longo KA, Bennett CN, Lucas PC, Erickson RL, et al. Inhibition of adipogenesis by wnt signaling. Science. 2000;289(5481):950–3. 10.1126/science.289.5481.950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Clouthier DE, Comerford SA, Hammer RE. Hepatic fibrosis, glomerulosclerosis, and a lipodystrophy‐like syndrome in pepck‐tgf‐beta1 transgenic mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(11):2697–713. 10.1172/jci119815 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Tontonoz P, Hu E, Spiegelman BM. Stimulation of adipogenesis in fibroblasts by ppar gamma 2, a lipid‐activated transcription factor. Cell. 1994;79(7):1147–56. 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90006-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wu Z, Rosen ED, Brun R, Hauser S, Adelmant G, Troy AE, et al. Cross‐regulation of C/EBP alpha and PPAR gamma controls the transcriptional pathway of adipogenesis and insulin sensitivity. Mol Cell. 1999;3(2):151–8. 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80306-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cunard R, Eto Y, Muljadi JT, Glass CK, Kelly CJ, Ricote M. Repression of IFN‐gamma expression by peroxisome proliferator‐activated receptor gamma. J Immunol. 2004;172(12):7530–6. 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tontonoz P, Spiegelman BM. Fat and beyond: the diverse biology of ppargamma. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77(1):289–312. 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061307.091829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Yang W, Yang C, Luo J, et al. Adiponectin promotes preadipocyte differentiation via the pparγ pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2018;17:428–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Yang W, Yuan W, Peng X, Wang M, Xiao J, Wu C, et al. Ppar γ/nnat/nf‐κb axis involved in promoting effects of adiponectin on preadipocyte differentiation. Mediators Inflamm. 2019;2019:5618023–9. 10.1155/2019/5618023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kruis T, Batra A, Siegmund B. Bacterial translocation ‐ impact on the adipocyte compartment. Front Immunol. 2014;4:510. 10.3389/fimmu.2013.00510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Weidinger C, Hegazy AN, Siegmund B. The role of adipose tissue in inflammatory bowel diseases. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2018;34(4):183–6. 10.1097/mog.0000000000000445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Montfort‐Ferré D, Serena C, Millan M, Boronat‐Toscano A, Maymo‐Masip E, Caro A, et al. P050 effect of biological treatments (anti‐tnfs) in the creeping fat of crohn’s disease patients. J Crohn's Colitis. 2021;15(1):S158–S9. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab076.179 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Kredel LI, Jödicke LJ, Scheffold A, Grone J, Glauben R, Erben U, et al. T‐cell composition in ileal and colonic creeping fat – separating ileal from colonic crohn’s disease. J Crohn's Colitis. 2018;13(1):79–91. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjy146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Saez A, Gomez‐Bris R, Herrero‐Fernandez B, Mingorance C, Rius C, Gonzalez‐Granado JM. Innate lymphoid cells in intestinal homeostasis and inflammatory bowel disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(14):7618. 10.3390/ijms22147618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Bénézech C, Jackson‐Jones LH. ILC2 orchestration of local immune function in adipose tissue. Front Immunol. 2019;10:171. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.00171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Molofsky AB, Nussbaum JC, Liang HE, Van Dyken SJ, Cheng LE, Mohapatra A, et al. Innate lymphoid type 2 cells sustain visceral adipose tissue eosinophils and alternatively activated macrophages. J Exp Med. 2013;210(3):535–49. 10.1084/jem.20121964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Park HS, Park JY, Yu R. Relationship of obesity and visceral adiposity with serum concentrations of crp, tnf‐alpha and il‐6. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2005;69(1):29–35. 10.1016/j.diabres.2004.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Reinisch W, Gasché C, Tillinger W, Wyatt J, Lichtenberger C, Willheim M, et al. Clinical relevance of serum interleukin‐6 in crohn's disease: single point measurements, therapy monitoring, and prediction of clinical relapse. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(8):2156–64. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01288.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Veenbergen S, Li P, Raatgeep HC, Lindenbergh‐Kortleve DJ, Simons‐Oosterhuis Y, Farrel A, et al. Il‐10 signaling in dendritic cells controls il‐1β‐mediated ifnγ secretion by human cd4(+) t cells: relevance to inflammatory bowel disease. Mucosal Immunol. 2019;12(5):1201–11. 10.1038/s41385-019-0194-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang Y, Proenca R, Maffei M, Barone M, Leopold L, Friedman JM. Positional cloning of the mouse obese gene and its human homologue. Nature. 1994;372(6505):425–32. 10.1038/372425a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Fazolini NP, Cruz AL, Werneck MB, Viola JP, Maya‐Monteiro CM, Bozza PT. Leptin activation of mtor pathway in intestinal epithelial cell triggers lipid droplet formation, cytokine production and increased cell proliferation. Cell Cycle. 2015;14(16):2667–76. 10.1080/15384101.2015.1041684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Lord GM, Matarese G, Howard JK, Baker RJ, Bloom SR, Lechler RI. Leptin modulates the t‐cell immune response and reverses starvation‐induced immunosuppression. Nature. 1998;394(6696):897–901. 10.1038/29795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Kern PA, Di Gregorio GB, Lu T, Rassouli N, Ranganathan G. Adiponectin expression from human adipose tissue: relation to obesity, insulin resistance, and tumor necrosis factor‐alpha expression. Diabetes. 2003;52(7):1779–85. 10.2337/diabetes.52.7.1779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Bilski J, Mazur‐Bialy A, Wojcik D, Surmiak M, Magierowski M, Sliwowski Z, et al. Role of obesity, mesenteric adipose tissue, and adipokines in inflammatory bowel diseases. Biomolecules. 2019;9(12):780. 10.3390/biom9120780 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Suau R, Pardina E, Domènech E, Lorén V, Manyé J. The complex relationship between microbiota, immune response and creeping fat in crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(3):472–89. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Burke JP, Mulsow JJ, O'Keane C, Docherty NG, Watson RWG, O'Connell PR. Fibrogenesis in crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102(2):439–48. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.01010.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Rieder F, Fiocchi C, Rogler G. Mechanisms, management, and treatment of fibrosis in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Gastroenterology. 2017;152(2):340–50.e6. 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.09.047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Borley NR, Mortensen NJ, Jewell DP, Warren BF. The relationship between inflammatory and serosal connective tissue changes in ileal crohn's disease: evidence for a possible causative link. J Pathol. 2000;190(2):196–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Sheehan AL, Warren BF, Gear MW, Shepherd NA. Fat‐wrapping in crohn's disease: pathological basis and relevance to surgical practice. Br J Surg. 1992;79(9):955–8. 10.1002/bjs.1800790934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Li XH, Feng ST, Cao QH, Coffey JC, Baker ME, Huang L, et al. Degree of creeping fat assessed by computed tomography enterography is associated with intestinal fibrotic stricture in patients with crohn's disease: a potentially novel mesenteric creeping fat index. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(7):1161–73. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Huang L, Qian W, Xu Y, Guo Z, Yin Y, Guo F, et al. Mesenteric adipose tissue contributes to intestinal fibrosis in crohn's disease through the atx‐lpa axis. J Crohns Colitis. 2022;16(7):1124–39. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjac017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Zhu Y, Qian W, Huang L, Xu Y, Guo Z, Cao L, et al. Role of extended mesenteric excision in postoperative recurrence of crohn's colitis: a single‐center study. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2021;12(10):e00407. 10.14309/ctg.0000000000000407 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Ewe K, Malchow H, Herfarth C. Radical operation and recurrence prevention with azulfidine in crohn disease: a prospective multicenter study—initial results. Langenbecks Arch Chir. 1984;364(1):427–30. 10.1007/bf01823251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Eder P, Katulska K, Krela‐Kaźmierczak I, Stawczyk‐Eder K, Klimczak K, Szymczak A, et al. The influence of anti‐tnf therapy on the magnetic resonance enterographic parameters of crohn's disease activity. Abdom Imag. 2015;40(7):2210–8. 10.1007/s00261-015-0466-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Rimola J, Fernàndez‐Clotet A, Capozzi N, Rojas‐Farreras S, Alfaro I, Rodriguez S, et al. Pre‐treatment magnetic resonance enterography findings predict the response to tnf‐alpha inhibitors in crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;52:1563–73. 10.1111/apt.16069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Clemente TR, Dos Santos AN, Sturaro JN, Gotardo EMF, de Oliveira CC, Acedo SC, et al. Infliximab modifies mesenteric adipose tissue alterations and intestinal inflammation in rats with tnbs‐induced colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2012;47(8‐9):943–50. 10.3109/00365521.2012.688213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.