Abstract

Uterine contraction is crucial for a successful labor and the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. It is enhanced by hypoxia; however, its underlying mechanisms are yet to be elucidated. In this study, transcriptomes revealed that hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha was upregulated in laboring myometrial biopsies, while blockade of hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha decreased the contractility of the myometrium and myocytes in vitro via small interfering RNA and the inhibitor, 2-methoxyestradiol. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing revealed that hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha directly binds to the genome of contraction-associated proteins: the promoter of Gja1 and Ptgs2, and the intron of Oxtr. Silencing the hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha reduced the expression of Ptgs2, Gja1, and Oxtr. Furthermore, blockade of Gja1 or Ptgs2 led to a significant decrease in myometrial contractions in the hypoxic tissue model, whereas atosiban did not remarkably influence contractility. Our study demonstrates that hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha is essential for promoting myometrial contractility under hypoxia by directly targeting Gja1 and Ptgs2, but not Oxtr. These findings help us to better understand the regulation of myometrial contractions under hypoxia and provide a promising strategy for labor management and postpartum hemorrhage treatment.

Keywords: HIF-1α, myometrial contractility, labor, GJA1, PTGS2

Introduction

Uterine contraction, running through the whole process of delivery, is a fundamental element of successful labor. Abnormal uterine contractility usually causes adverse events to both the mother and fetus. For example, hyperactive contractility may induce uterine rupture and fetal distress. However, weak contractions lead to failure in the continuation of labor, an increased risk for cesarean section, and postpartum hemorrhage [1–4]. Uterine contractions are modulated by many factors, such as inflammation, hypoxic stress, mechanical tension, and hormones [5–7]. Similar to other smooth muscle cells, various stimuli trigger membrane excitation and voltage-dependent L-type calcium channel opening, which elicit the interactions of myosin and actin, thus promoting cell contraction [8, 9]. Studies have found that uterine contraction-associated proteins (CAPs) such as connexin43 (Gap junction protein alpha 1, Gja1), COX-2 (Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2, Ptgs2), and oxytocin receptors (Oxtr) are considered to be related to enhanced labor contractions [10–13]. CAPs function by promoting signal transduction or synthesizing pro-contractile substances. Among them, Oxtr is the main target molecule for the regulation of uterine contractions in obstetrics, although there are still many cases of labor induction failure. Therefore, elucidating the regulatory mechanism of uterine contractions is of great significance to reduce labor complications.

A physiological decrease in oxygen during the normal process of labor has confirmed that compression to blood vessels following every myometrial contraction results in a reduction in blood flow [14, 15]. The evidence implies that the myometrium suffers from hypoxic stress during labor. A series of studies on myometrial metabolites have shown that sufficient glycogen and fatty acid droplets are stored in the myometrium at term, as well as the moderate increased content of ATP and phosphocreatine [16]. These changes provide the material basis for the myometrium to withstand hypoxic stress caused by myometrial contractions in labor. A recent study by Alotaibi et al. revealed that hypoxia increases human myometrial contractility, which is termed hypoxia-induced force increase [17]. Alotaibi discussed the effects of ATP, pH, and lactate on hypoxia-enhanced myometrial contractions from the perspective of metabolism. Except for the metabolism, hypoxic stress can also elicit changes in multiple molecular pathways to cells [18], which may be regulated by certain transcription factors.

Hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF), including HIF-1, HIF-2, and HIF-3, was first discovered in the 1990s [19]. Both HIF-1α and HIF-2α are considered to function as master regulators of adaptive response to hypoxia, contributing to oxygen homeostasis [20]. The HIF-1α is ubiquitously expressed in various cells, while HIF-2α is selectively expressed in specific cell populations. Functioning as two important transcription factors in cells, they both have overlapping and different target genes. Target genes induced by HIF can promote angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, and metabolic remodeling [21–23]. Notably, HIF-1α has been reported to have protective effects on cells under hypoxic stress [24–26]. Moreover, recent studies have noted that high mRNA levels of HIF-1α are detected in the laboring myometrium [27–29], which suggest that HIF-1α might be a key molecule involved in the regulation of myometriul contractions during labor. Thus, there are questions as to whether HIF-1α is involved in the regulation of hypoxia-induced myometrial contractions, and how HIF-1α mediates the effects of hypoxia on myometrial contractility.

In this study, HIF-1α was blocked to demonstrate its roles in the contractility and the expression of CAPs (Gja1, Ptgs2, and Oxtr) in the myometrium. In addition, chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) analysis was used to localize HIF-1α to the Gja1, Ptgs2, and Oxtr loci in human myometrial smooth muscle cells (hMSMCs). Finally, CAPs were inhibited under hypoxic conditions to show how HIF-1α mediates hypoxia-driven myometrial contractions.

Materials and methods

Reagents

ON-TARGETplus Human Hif1a (Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 Subunit Alpha) small interfering RNA (siRNA) smartpool (L-004018-00-0005), ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Control Pool (D-001810-10-05) (Thermo, USA). Transfection reagent for uterine smooth muscle (INTERFERin, 409-10) was bought from polyplus (Polyplus Transferion SA, France). 2-Methoxyestradiol (2-MeOE2, HY-12033), oxytocin acetate (HY-17571A), atosiban acetate (HY-17572A), valdecoxib (HY-15762), and TAT-Gap19-TFA (HY-P1136C) were purchased from MCE (MedChemExpress, USA).

Study populations and tissue collection

Myometrial biopsies were obtained from women undergoing cesarean delivery who reached the following criteria: 18–40 years old, term, singleton, and nulliparous in Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center. For the nonlabor group (n = 10), the indication for cesarean delivery was a breech presentation or maternal request without any medical complications. For the in-labor group (n = 10), biopsies from women in spontaneous labor were obtained during emergency cesarean section due to cephalopelvic disproportion and fetal distress. All samples were collected from the upper edge of the lower segment uterine incision. Women with any of the following conditions were excluded: (1) complications, including hypertension, eclampsia, cholestasis, gestational diabetes, and other diseases; (2) abnormal labor, including uterine atony or prolonged labor; (3) placenta abnormality, including placental abruption, placenta previa, or infection. The tissue specimens were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and then stored at −80°C. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou Women and Children Medical Center (No. 201915401). All women provided written informed consent.

Isometric tension recordings of uterine smooth muscle in vitro

Tissue samples were collected from nonlaboring women who underwent cesarean section at term, meeting the criteria above. The samples were placed into pre-cold Kreb’s solution (119 mM NaCl, 25 mM NaHCO3, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 4.7 mM KCl, 1.2 mM MgSO4·H2O, 0.026 mM Na2·EDTA·2H2O, 11.5 mM glucose, and 2.5 mM CaCl2·H2O) immediately after they were removed from the womb. The myometrium of each patient was divided longitudinally into at least four strips (each with an approximate size of 10 mm × 2 mm × 2 mm), parallel to the direction of the muscle fibers. The strips were then randomly assigned into different groups. Each strip was mounted into a single organ bath chamber filled with Kreb’s solution at 37°C and a pH of 7.4. The organ bath solution was aerated continuously with a mixture of 95% oxygen (O2) and 5% carbon dioxide (CO2). The strips were allowed to equilibrate in the Kreb’s solution at 2 g as initial tension for at least 2 h, and whichever did not spontaneously contract was discarded.

To first determine the effect of HIF-1α on myometrial contractility in vitro, the inhibitor, 2-methoxyestradiol (2-MeOE2), was applied to the chambers of the 2-MeOE2 group at a concentration of 10 μM. Meanwhile, dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was added into the chambers of the hypoxia group to provide the same amount (0.1% v/v) of the vehicle. After 30 min, the hypoxia-reoxygenation treatment cycles began. Based on the method used in Alotaibi’s work [17], the aforementioned chambers were treated with 100% nitrogen (N2) to create the hypoxic condition for 15 min, and then reoxygenated with the mixed gas for 45 min. Parallel to this, strips from the normoxia group were only aerated continuously with the oxygen-enriched gas mixture throughout the process. TAT-GAP19-TFA, valdecoxib, and atosiban were used in the next step to block GJA1, PTGS2, and OXTR in the myometrium, respectively [17, 30–32].

Contractile parameters, such as the area under the curve (AUC or integral, g·s) and amplitude (g), were normalized to the value at which equilibrium was completed, and the data were presented as percentages. In every experiment, a portion of the strips from each group was taken out from the chambers at the end of the last hypoxic condition (before T3 started), wiped dry, fast-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C.

Primary culture and characterization of hMSMCs

Myometrial tissues from nonlaboring pregnant women were collected and washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline until there was no obvious bloodstain. Endometrial tissues and vessels, if present, were also weeded out. The samples were cut into small pieces (5 mm × 5 mm × 5 mm) and inoculated onto several culture dishes. After a 14-day culture with DMEM (Dulbecco’s modified eagle medium) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (#10099-141, Gibco) and 1% penicillin–streptomycin (10 000 U/mL, #15140122, Gibco), cells were harvested and further subcultured. To characterize the cells, the two markers, caldesmon and α-smooth muscle actin, for myometrial smooth muscle cells were detected via immunofluorescence.

Immunostaining

Myometrial tissue specimens were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 48 h. The tissues were embedded in paraffin and sliced into 5 μm. The tissue sections were dewaxed and hydrated, followed by antigen retrieval in sodium citrate buffer. When the sections had cooled down, they were placed into 3% hydrogen peroxide for blocking the activity of endogenous peroxidase for 25 min protected from light. After blocking with 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h, the sections or cells were incubated with anti-HIF-1α (1:100, ab51608, Abcam) overnight at 4°C. The tissues were covered with goat anti-rabbit HRP-labeled secondary antibody (1:2000, ab205718, Abcam) at room temperature for 1 h. DAB chromogenic reaction was performed using an Immunohistochemical kit DAB chromogenic agent (G1211, Servicebio, Wuhan, China). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin stain solution for 3 min, washed with tap water, differentiated with 1% hydrochloric acid in ethanol for several seconds, and washed with running water. The sections were dehydrated with ethanol and xylene and then were mounted with neutral gum.

The hMSMCs were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 30 min, followed by permeabilization with PBST (0.3% TritonX in phosphate-buffered saline) for 15 min. After blocking with 10% goat serum at room temperature for 1 h, the cells were incubated with anti-α-SMA (1:500, ab7817, Abcam), anti-HIF-1α (1:500, ab2185, Abcam), and Caldesmon (1:100, ab32330, Abcam) overnight at 4°C, followed by a 1-h incubation with Alexa 594 goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (1:250, ab150116, Abcam) or goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488-IgG (1:500, ab150077, Abcam) protected from light. The cells were mounted with Vectashield (ZH0309, Vector laboratories).

All images were visualized and acquired via Leica DMi8 microscopy.

Cell transfection

The HIF-1α in hMSMCs was silenced with siRNA using RFect reagent (INTERFERin, 409-10, polypus) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The sense sequence is as follows: siRNA J-004018-07, Hif1a (sense, GAACAAAUACAUGGGAUUA); siRNA J-004018-08, Hif1a (sense, AGAAUGAAGUGUACCCUAA); siRNA J-004018-09, Hif1a (sense, GAUGGAAGCACUAGACAAA); siRNA J-004018-10, Hif1a (sense, CAAGUAGCCUCUUUGACAA); siRNA J-019376-12, Hif1a (sense, GAGACAGGCAGCUCGGAUU). Nontargeting sequences were used as control (negative control, NC). The fourth to fifth passage of hMSMCs (P4–P5) was infected using a final siRNA concentration of 10 nM for 24–96 h. Gene silencing is usually measured between 24 and 72 h for mRNA levels and 48 and 96 h for proteins.

Establishment of the hypoxic hMSMCs model

Once the degree of cellular confluency reached >90%, hMSMCs were divided into the hypoxia and control groups (treated for 2, 4, and 6 h to find the appropriate time). Human MSMCs from the hypoxia group were transferred into the hypoxic workstation (H35, Don Whitley Scientific, UK) under the set condition: 3% O2, 5% CO2, and 92% N2.

hMSMCs-gel contraction assay

A cell contraction assay kit (#CBA-201, Cell Biolabs Inc. San Diego, CA, USA) was used to evaluate the contractility of hMSMCs. Collagen mixture solution was prepared with 9.54 mL collagen solution, 2.46 mL DMEM (5×), and 340 μL neutralization solution according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Based on the protocol from Anamthathmakula’s research [33], primary hMSMCs were trypsinized and seeded into a collagen gel, and the contraction assay was carried out following the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly explained, a collagen lattice was prepared by mixing one part of cell suspension from each group with four parts of cold collagen mixture solution to achieve 1.5 × 105 cells per 0.5 mL/well. A cell-collagen mixture of 0.5 mL was added per well in a 24-well plate and incubated for 1 h at 37°C to allow gelling. DMEM (1.0 mL) containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin–streptomycin was added over the cell-collagen matrix. After a 24-h culture, the cells were treated with either hypoxia (for 2, 4, and 6 h) or normoxia to determine the appropriate hypoxic time for increasing the cellular contractility. The determined hypoxic time was then used for subsequent cellular mechanism validation experiments.

After the treatments, the medium of each well was replaced with fresh medium. To initiate the contraction, the gels from all groups were gently released. The area of the floated gel was measured periodically from 1–4 h after released. Images of the gels were captured and digitized using a ChemiDoc XRS+ (Bio-Rad), and the mean gel area (mm2) was measured using Image Lab software.

Quantitative polymerase chain reaction

Total RNA was extracted and purified from myometrial cells using RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (#74136, QIAGEN). RNA concentration was measured by Multiskan GO. The total RNA (1.5 μg) was used in the Bestar quantitative polymerase chain reaction (Q-PCR) reverse transcription kit (#2220; DBI, Ludwigshafen, Germany) under the following conditions: initial denaturation at 95°C for 10 min, followed by 40 Q-PCR cycles (95°C for 15 s, then 60°C for 30 s), and resolution melting (from 65°C to 95°C, rise of 0.3°C every 15 s). Experiments were performed in triplicates and repeated three times. The primer sequences for each gene are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Actin beta (Actb) was used as an endogenous control for gene expression analysis. Changes in mRNA expression were calculated based on the 2-ΔΔCT method (cycle threshold) [34]. The reference data for biopsies and hMSMCs were grouped into nonlabor and control groups.

Western blot

Protein was extracted from myometrial tissues and cells using the RIPA lysis buffer. It is noteworthy that cell lysis ought to occur within 5 min of being removed from a hypoxic environment. Protein concentration was measured using a BCA assay kit (#23227, Thermo Scientific, USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Western blot protein samples were loaded in SDS-PAGE gel, separated by electrophoresis, and transferred onto PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride) membranes (IPVH00010, Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany). Protein levels were quantified by a ChemiDoc XRS+. β-Actin was used as a loading control. The western blotting antibodies used were anti-oxytocin receptor (1:5000, ab181077, Abcam), anti-Connexin43 (1:2000, #3512, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-HIF-1α (1:1000, ab2185, Abcam), anti-HIF-2α (1:1000, ab199, Abcam), COX-2 (1:2000, ab179800, Abcam), and anti-β-actin (1:1000, ab8226, Abcam). Every experiment was replicated at least three times.

ChIP sequencing

Library preparation and sequencing

Amounts of 2 × 107 hMSMCs (passage 4–5) were placed under the hypoxic condition (3% O2) for 2 h or under normoxic condition. After treatment, the cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature, followed by the addition of glycine to 0.125 M final concentration for terminating the crosslinking reaction. Following 5 min of formaldehyde quenching, plates were placed on ice and washed three times with ice-cold PBS and the cells were then collected and frozen in liquid nitrogen. ChIP-seq for H3K27ac was detected in both normoxia and hypoxia groups, while HIF-1α was detected only in hypoxia group.

ChIP assay was performed by SeqHealth (Wuhan, China). The cells were treated with nucleus lysis buffer and sonicated to fragment chromatin DNA of ~200–1000 bp. The 10% lysis sonicated chromatin was stored and named “input,” and 80% was used in immunoprecipitation reactions with anti-HIF-1α antibody (#36169S, Cell Signaling Technology, MA, USA) or H3K27ac (#8173, Cell Signaling Technology) and named “IP,” and 10% was incubated with rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology) as a negative control and named “IgG,” respectively. The DNA of input and IP was extracted by the phenol-chloroform method. The high-throughput DNA sequencing libraries were prepared by using VAHTS Universal DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina V3 (Catalog NO. ND607, Vazyme). The library products corresponding to 200–500 bp were enriched, quantified, and finally sequenced on Novaseq 6000 sequencer (Illumina) with the PE150 (paired-end 150 bp sequencing) model.

ChIP-seq data analysis

Raw sequencing data (~22–96 × 106 raw reads per sample) were first filtered by Trimmomatic (version 0.36), low-quality reads were discarded, and the reads contaminated with adaptor sequences were trimmed. The clean reads (~21–94 × 106 clean reads per sample) were used for protein binding site analysis. They were mapped to the reference genome of human from GRCh38/hg38 from ftp://ftp.ensembl.org/pub/release-87/fasta/homo_sapiens/dna/using STAR software (version 2.5.3a) with default parameters, ~19–90 × 106 final mapped reads per sample. The RSeQC (version 2.6) was used for reads distribution analysis. The MACS2 software (version 2.1.1) was used for peak calling. The bedtools (version 2.25.0) was used for peaks annotation and peak distribution analysis. The data presented in the study were deposited in the GEO repository, accession number GSE197160 for HIF-1α. And the data for H3K27ac were deposited in the GSA repository, accession number HRI266643.

Data analysis

Data for continuous variables are presented as mean ± SEM. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 13.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) and GraphPad Prism 8.4.0 software (San Diego, CA, USA). Two-way ANOVA was used to test the difference in the contraction of the myometrium and hMSMCs over time, and Tukey’s test was used for multiple comparisons. The statistical significance of the results was evaluated by one-way ANOVA or the Welch test if variances were not similar. The normality of the data was tested by Shapiro–Wilk test. Student’s t-test analysis was used for the changes of mRNA and proteins when comparing the difference between two independent groups of tissue or cells. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

High expression of HIF-1α in uterine myometrium is associated with labor

A total of 20 full-term pregnant women were enrolled. A total of 10 women were in the nonlabor group and the other 10 were in the in-labor group. Both groups were similar in regards to patient age, body mass index (BMI), gestational week, neonatal weight, and volume of operative and postpartum bleeding (Supplementary Table 2).

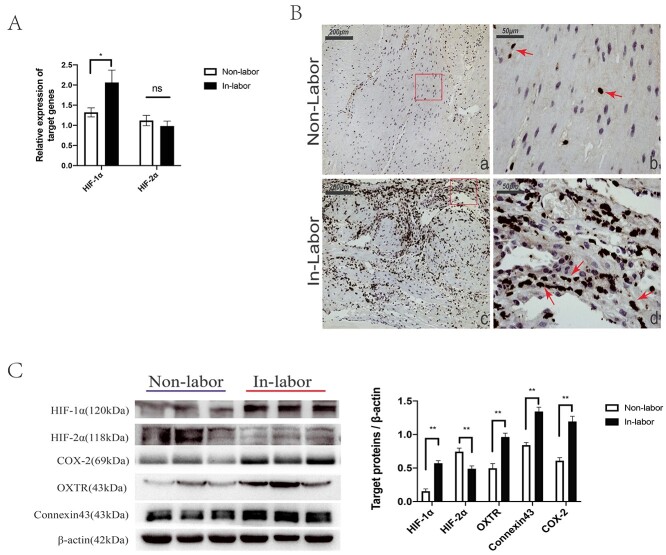

Our previous transcriptomics research on human laboring and nonlaboring myometriun myometrium revealed that HIF-1 signaling pathway was significantly enriched by the differentially expressed genes, and the enriched mRNAs were upregulated in laboring myometrium [29] (Supplementary Figures S1 and S2). The high levels of HIF-1α in laboring myometrium were verified by Q-PCR and western blot (Figure 1A and 1C). Immunohistochemistry showed that HIF-1α was located in the nucleus (Figure 1B). In addition, CAPs (oxytocin receptor, COX-2, and connexin43) were detected and they were consistently higher in laboring myometrium (Figure 1B). Considering that HIF-2α also functions as another regulator responding to hypoxia, the expression was detected as well, and the mRNA level was no significant difference but the protein level significantly decreased in laboring myometrium (Figure 1A and 1C).

Figure 1.

Comparison of the expression levels of mRNA and protein detected in myometrium between groups. (A) Q-PCR analysis of mRNA levels of HIF-1α (Hif1a) and HIF-2α (Endothelial PAS Domain Protein 1, Esap1) (10 nonlaboring vs. 10 laboring samples). (B) Western blot analysis of indicated protein expression (10 nonlaboring vs. 10 laboring samples). (C) Detection of HIF-1α in myometrium sections was visualized by immunohistochemistry. The HIF-1α (+) staining signal was shown in the nuclei, pointed out with arrows. Images (a) and (c) represent nonlaboring and laboring myometrium, respectively; scale bar: 200 μm. Images (b) and (d) are the enlarged view of image (a) and (c), respectively; scale bar: 50 μm. Compared to nonlabor, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns for no significance.

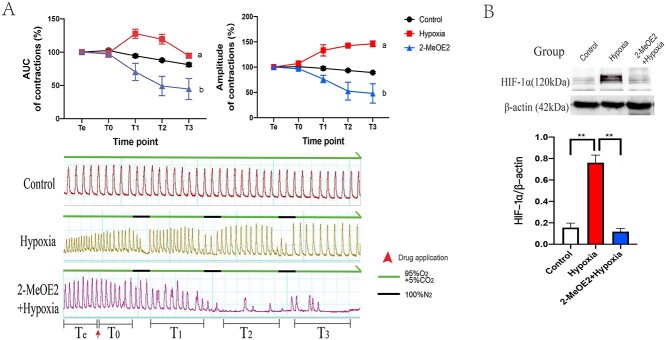

HIF-1α is Involved in the augmentation of uterine myometrial contractility in vitro

Although hypoxia has been demonstrated as a promoting factor of myometrial contraction [17], the mechanism of specific molecular regulation is ambiguous. Therefore, the myometrial model of “hypoxia-induced force increase” was developed. The AUC and amplitude of the hypoxia group after a transient hypoxic treatment gradually increased significantly compared with that of the control group. To confirm the effect of HIF-1α in this phenomenon, 2-MeOE2, the HIF-1α inhibitor [35], was added 30 min before the first hypoxia treatment. Data showed that in the 2-MeOE2 group, both the AUC and amplitude dramatically decreased after the transient hypoxic treatment, which suggested that HIF-1α might have participated in the augmentation (Figure 2A). Additionally, to test our hypothesis, three uterine strips were collected from each group right at the end of the third hypoxic treatment. The highest amount of HIF-1α in the strips from the hypoxia group was detected by western blot. Compared to the hypoxia group, 2-MeOE2 caused a significant reduction of HIF-1α expression (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Isometric tension measurement of uterine strips in vitro (n = 6). The process was divided into five periods: (1) Te for observing spontaneous contraction and baseline setting; (2) T0 for the period after reagents added; (3) T1, T2, and T3 representing periods of contractile changes following corresponding hypoxic treatment. (A) Changes of AUC and amplitude among the group from Te to T3 and the information of waves and experiment settings. During the normoxic period, the chambers were bubbled with mixed gas (95% O2 + 5% CO2), whereas 100% N2 was bubbling for 15 mins into the chambers to create hypoxic condition. (a) Compared group hypoxia to control, the AUC in T1 (P < 0.05) and T2 (P < 0.01) was significantly higher, and the amplitude in group hypoxia gradually improved from T1 to T3 (P < 0.01). (b) Compared group hypoxia to control, both the AUC and amplitude were dramatically reduced following each hypoxic treatment, especially in T2 (P < 0.01) and T3 (P < 0.01). (B) Expression of HIF-1α in isolated uterine strips from groups. **P < 0.01.

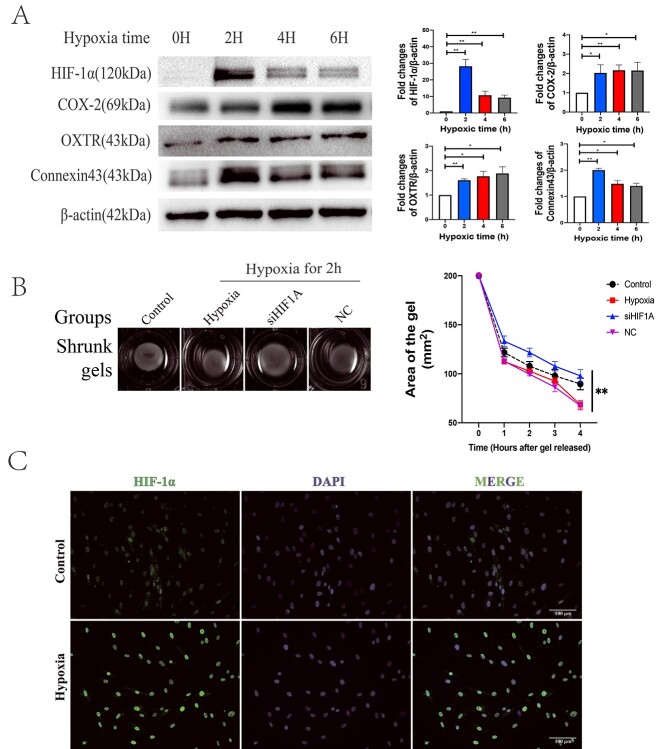

HIF-1α promotes the contractility of hMSMCs under hypoxia

Immunofluorescence revealed that both the caldesmon and α-SMA were detected on the cells, indicating that the high-purity primary hMSMCs were successfully isolated and were suitable for the subsequent cell experiments (Supplementary Figure S3). Interestingly, under 2 h of hypoxia, HIF-1α expression was the highest and gradually decreased with prolonged time. The expression levels of CAPs in hMSMCs were also higher in all hypoxia groups than in the normoxia group (Figure 3A). In addition, a cell-gel contraction assay was performed to investigate the contractility of hMSMCs. The cell gels that received a 2-h hypoxia treatment shrank into smaller size compared to the ones treated with normoxia, as well as the ones that received the 4- or 6-h hypoxia (Supplementary Figure S4). Meanwhile, knockdown of HIF-1α caused larger size to the cell gels compared to group NC (Figure 3B). Moreover, hypoxia elicited high expression and accumulation of HIF-1α in the nuclei (Figure 3C). The results combined suggested that the 2-h hypoxic treatment induced the expression of HIF-1a and enhanced the contractility of hMSMCs most significantly. Therefore, this condition of 2-h hypoxia was used for the following experiments.

Figure 3.

Evaluation of hypoxia hMSMCs model. (A) Western blot analysis of indicated protein expression under 3% O2 for different time (h) (n = 3). (B) The shrunk gels of different groups in hMSMCs-gel contraction assay (n = 3). Images of gel area were captured from the first hour to the fourth hour after gels released; group control was treated under normoxia; group hypoxia, siHIF1A, and NC (negative control for siHIF1A) were treated with hypoxia for 2 h before released. (C) Location of HIF-1α in hMSMCs was visualized by immunoflourescence. Scale bar: 100 μm. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

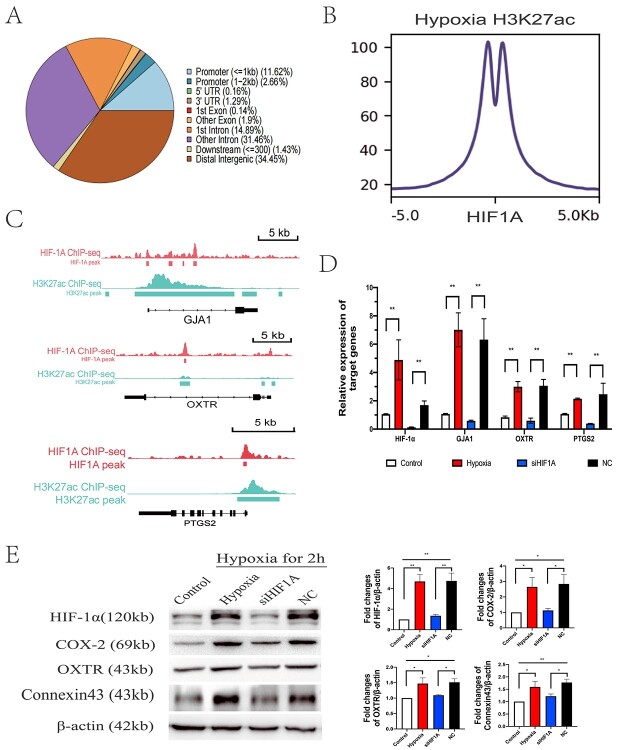

ChIP-seq analysis showed that the HIF-1α in the nuclei could bind to the promoters of genes, approximately up to 14.26% of the genome (Figure 4A). In addition, hypoxia caused acetylation of the indicated histone H3 lysine 27, which reflects the activation of corresponding genes. The intensity of HIF-1α ChIP-seq signals was centered at the H3K27ac peak in hypoxic hMSMCs, suggesting that HIF-1α was involved in the activation of the genome (Figure 4B). To investigate how hypoxia influenced myometrial contractility, we merged the tracks for HIF-1α and H3K27ac at the genomic regions of GJA1, PTGS2, and OXTR. Under hypoxia, H3K27ac signals were detected on and near the transcription initiation region of GJA1, PTGS2, and OXTR. The HIF1A signals overlapped H3K27ac signals in the promoter of GJA1 and PTGS2 and in the coding region of both GJA1 and OXTR (Figure 4C). The results of Q-PCR and western blot showed that the upregulation of GJA1, OXTR, and PTGS2 induced by hypoxia was reversed after knockdown of HIF-1α in hMSMCs (Figure 4D and E).

Figure 4.

ChIP-seq analysis on hypoxic hMSMCs (A–C) and verification of effects of HIF-1α on hMSMCs contractility (D–F). (A) Pie charts depicting the proportion of ChIP-seq peaks of HIF1A that cover each genomic region annotation. Annotations are derived from ChIPseeker. (B) The line plot and heatmap show the intensity of HIF1A ChIP-seq signals centered at the H3K27ac peak in hypoxic hMSMCs. (C) ChIP-seq tracks for HIF1A and H3K27ac at the genome regions of Gja1, Ptgs2 and Oxtr in hMSMCs. (D) Expressed mRNA levels of indicated genes by q-PCR (n = 4). (E) Expressed levels of indicated proteins by Western blot (n = 4). Control: cells under normoxia; hypoxia: cells under hypoxia for 2 h; siHIF1A: cells with HIF1A knocked down, treated with hypoxia for 2 h; NC: cells with siRNA negative control, treated with hypoxia for 2 h. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

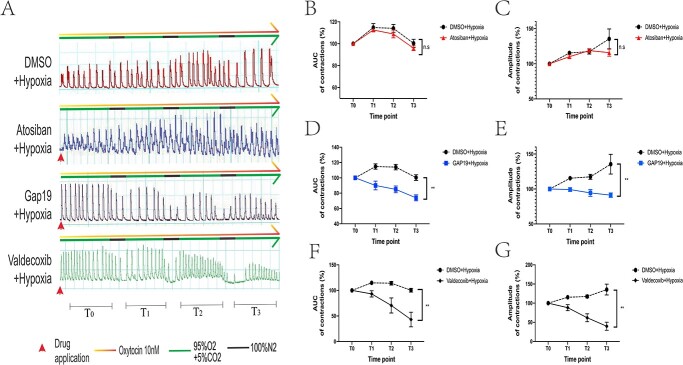

Hypoxia-driven contractility increase is more dependent on GJA1 and PTGS2 than on OXTR

Based on the fact that GJA1 and OXTR were screened out to be regulated by HIF-1α, TAT-Gap19-TFA (100 μM), valdecoxib (50 nM), and atosiban (100 nM) were applied in an attempt to block the connexin 43, COX-2, and oxytocin recepter, respectively, in myometrial strips. Labor was mimicked using hypoxia and 10 nM oxytocin. We observed that both the application of TAT-Gap19-TAF and valdecoxib led to the decrease of contractile AUC (at T3, DMSO vs. Gap-19 vs. valdecoxib: 100.36 ± 3.31% vs. 73.91 ± 3.46% vs. 43.08 ± 11.6%) and amplitude (at T3, DMSO vs. Gap-19 vs. valdecoxib: 135.45 ± 12.61% vs. 91.19 ± 2.86% vs. 39.77 ± 8.55%) during the experiment, whereas atosiban failed to cause a statistically significant decrease in contractions (AUC and amplitude at T3 were 95.89 ± 1.93% and 115.83 ± 4.45, respectively) (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In vitro myometrial contractility measurement about the blockade of connexin43 (n = 5), oxytocin recepter (n = 5), and COX-2 (n = 3). Oxytocin and hypoxia were utilized to mimic the condition of the uterine muscle in the state of labor. The applied reagents, atosiban, Gap 19, and valdecoxib, are the antagonists of oxytocin recepter, connexin 43, and COX-2, respectively. DMSO was added as the vehicle in this experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ns for no significance.

Discussion

An appropriate intensity of uterine contractions does not only contribute to the advancement of labor, but also to the prevention of postpartum hemorrhage. Normally, the periodic contractions during labor cause hypoxia in the myometrium. In recent years, Alotaibi et al. investigated the underlying mechanism of hypoxia induced contractility via evaluating the effects of different reagents on the contractile function of rat myometrium [17]. Wray also reported that hypoxia regulates uterine contraction and relaxation by altering pH, ATP production, and ion channels [16]. However, few studies on the molecular regulatory mechanisms of hypoxia enhancing the contractility of myometrium have been conducted.

In this study, we demonstrated that HIF-1α is significantly elevated and enhances myometrial contractility under hypoxia. Both the inhibition and knockdown of HIF-1α caused a reduction of contractile function in the myometrium and hMSMCs. Utilizing ChIP-seq intuitively indicated that HIF-1α directly regulates the expression of CAPs (Gja1, Ptgs2, and Oxtr). Moreover, blockade of Gja1 or Ptgs2, but not Oxtr, led to a remarkable decrease in myometrial contractions after hypoxia.

HIF-1α and HIF-2α are the main factors transcribed under hypoxia. In well-studied systems, such as the nervous and cardiovascular systems, HIF-1α exerts protective effects and promotes cellular function recovery in hypoxia. Niemi’s study has shown that HIF-1α and HIF-2α regulate ischemic muscle recovery to preserve left ventricular function [36]. Our results showed that HIF-1α protein expression is increased strongly after 2 h of hypoxic treatment, and then decreases during the 4- and 6-h timepoints, while HIF-2α protein expression is increased after 4 h of treatment (nonpublic), suggesting the expression of HIF-1α and HIF-2α were hypoxic time dependent. Research conducted by Nanduri et al. indicates that intermittent hypoxia induces a decreased level of HIF-2α in rat pheochromocytoma 12 (PC12) cells, whereas HIF-1α is remarkably upregulated [37]. It is also revealed that HIF-1α and HIF-2α switch according to the hypoxia lasting in cells [38–40]. Most of the findings on HIF-2α suggest that HIF-2α is responsible for chronic hypoxia and long-term stress [37, 38, 41, 42].

Extensive research on hMSMCs during parturition has revealed that upregulated mRNA levels of HIF-1α are detected in the myometrium; however, specific functions of HIF-1α during parturition have not been investigated [27–29]. It is noteworthy that in this study, both mRNA and protein levels of HIF-1α, but not of HIF-2α, were elevated in the laboring myometrium, suggesting that HIF-1α is the more influencing mediator in the myometrium during parturition.

The increased expression of HIF-1α has been reported to be involved with cell proliferation, glucose metabolism, energy metabolism, angiogenesis, and other processes in several cells and tissues [43–45]. In addition, researchers have also demonstrated that HIF-1α improves the contractility of cardiomyocytes by mediating Ca2+ transients [46, 47]. Research on HIF-1α mediating contractions of smooth muscle cells has led to the study of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells (PASMCs), as hypoxia can elicit pulmonary hypertension. However, the effect of HIF-1α on the contractile function of PASMCs remains controversial. Wang illustrated that HIF-1α regulates the expression of transient receptor potential cation channels and the facilitation of capacitative Ca2+ entry induced by hypoxia, which explains the increased contraction of PASMCs in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension [48]. In contrast, Barnes gave evidence that loss of HIF-1α occurred in patients with idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension [49]. However, in the human uterus, there is no investigation of myometrial contractions related to HIF-1α. A study by Ishikawa showed that an increase of HIF-1α in hMSMCs was only detected by CoCl2, but not by hypoxia, at 1% O2 from 2 to 12 h [50]. Our work shows a remarkably high level of HIF-1α protein among groups of hypoxic hMSMCs, especially when the hMSMCs undergo hypoxia for 2 h. For the first time, we confirmed that knockdown of HIF-1α can remarkably influence myometrial contractility, suggesting that HIF-1α is required for the physiological phenomenon of hypoxia-promoting uterine contractions.

ChIP-seq is a powerful tool for studying protein–DNA interactions in vivo. It is usually used to study transcription factor binding sites or histone-specific modification sites [51]. Our findings revealed that HIF-1α binds to CAP genes under hypoxic conditions, verifying that HIF-1α is directly involved in the regulation of myometrial contraction under hypoxia. The Oxtr, Gja1, and Ptgs2 are well-recognized CAPs in the field of obstetrics research [52–55]. The Oxtr, bound by oxytocin, increases intracellular Ca2+ concentration to promote myometrial contraction [56]. Gja1 can not only act as a hemi-channel to allow molecules to pass into cells but also can form gap junction channels to couple intercellular electrical signals to facilitate the propagation of contractile signals [53]. Ptgs2 induces myometrial contraction by promoting the synthesis of prostaglandin [57]. Oxytocin is a commonly used drug for increasing myometrial contractions. However, the longer the use of oxytocin for labor induction, the higher the probability of postpartum hemorrhage, neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) admission rate, and other complications, not to mention the failure of labor induction. Research by Takayanagi et al. revealed that Oxtr-deficient mice are still able to perform normal parturition [58]. Interestingly, a delayed delivery occurred in connexin43-deficient mice in the study of Döring et al [59]. Coincidentally, the results here also illustrate that blockade of Gja1 and Ptgs2 suppresses the enhanced myometrial contractility under hypoxia more than the inhibition of Oxtr. Moreover, the phenomenon that atosiban fails to suppress the myometrial contractions induced by hypoxia is consistent with Alotaibi’s theory that the hypoxia-induced force increase in myometrium is not dependent on oxytocin. The upregulated Gja1 under hypoxia can be considered to distribute stress signals from cell to cell throughout the myometrium via gap junctions, and Ptgs2 might induce inflammation and promote lipid metabolism, resulting in augmentation of myometrial contractility. Gja1 and Ptgs2 are the dominant CAPs in response to hypoxic stress during labor. Although cell experiments have demonstrated that HIF-1α can regulate the expression of Oxtr, antagonizing oxytocin can not inhibit the effect of hypoxia in promoting uterine contractions, suggesting that it is not adequate to only focus on regulating uterine contractions by oxytocin. However, due to the hypercoagulable state of maternal blood, inhibitors of COX-2 have the potential to increase the risk of thrombosis. Therefore, the development of myometrial drugs targeting Gja1 should be considered in the future.

In summary, HIF-1α is essential for the physiological phenomenon of hypoxia-enhanced myometrial contractions via direct regulation of CAPs, and the absence of oxytocin does not inhibit the increased contractility caused by hypoxia. These findings reveal a novel molecular mechanism of enhanced uterine contractions during labor. The HIF-1α will be an important molecule for future investigation on regulating cellular function of hMSMCs during labor. In-depth research may provide new targets for the management of parturition and prevention of postpartum hemorrhage.

Data availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgment

We thank Dr Xiuyu Pan and Dr Wen Ding for providing cases in the hospital. The authors are grateful for the help of analysis of biological information from Dr Lina Chen. Mr Matthew Thomas Parker from Guangzhou Medical University, Dr Qirong Wen and Dr Chao Liu in Guangzhou women and children’s medical center are appreciated for the revision suggestion.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81871181), Guangzhou Municipal Science and Technology Bureau (No. 202102010016, No. 202201020592), High-tech Major Featured Technology Program of Guangzhou Municipal Health Commission (No. 2019GX07), and Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province (No. 2020A1515110077), Guangzhou Women and Children's Medical Center Pilot Program (YIP-2019-045).

Contributor Information

Bolun Wen, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Zheng Zheng, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Lele Wang, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Xueya Qian, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Xiaodi Wang, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Yunshan Chen, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Junjie Bao, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Yanmin Jiang, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Kaiyuan Ji, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Huishu Liu, Guangzhou Key Laboratory of Maternal-Fetal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center, Guangzhou Medical University, Guangzhou, China.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Authors’ contributions

All authors approved the final version of the manuscript. B.W. and Z.Z. contributed equally to this article, including planning of the research, running of the experiments, analysis of data and the writing of the manuscript. L.W. and X.Q. contributed to acquisition and verification of the data. X.W. and Y.C. contributed to running of the experiments and acquisition of biopsies. J.B. and Y.J. contributed to analysis and interpretation of data and revised the article critically. K.J. contributed to the analysis of ChIP-seq. H.L. was the PI of the project and responsible for designing the study and contributed to the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data and the writing of the article.

References

- 1. Meniru GI, Brister E, Nemunaitis-Keller J, Gill P, Krew M, Hopkins MP. Spontaneous prolonged hypertonic uterine contractions (essential uterine hypertonus) and a possible infective etiology. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2002; 266:238–240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kramer MS, Rouleau J, Baskett TF, Joseph KS, Maternal Health Study Group of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System . Amniotic-fluid embolism and medical induction of labour: a retrospective, population-based cohort study. Lancet 2006; 368:1444–1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Thisted DL, Mortensen LH, Krebs L. Uterine rupture without previous caesarean delivery: a population-based cohort study. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015; 195:151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weisman O, Agerbo E, Carter CS, Harris JC, Uldbjerg N, Henriksen TB, Thygesen M, Mortensen PB, Leckman JF, Dalsgaard S. Oxytocin-augmented labor and risk for autism in males. Behav Brain Res 2015; 284:207–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Shynlova O, Lee YH, Srikhajon K, Lye SJ. Physiologic uterine inflammation and labor onset: integration of endocrine and mechanical signals. Reprod Sci 2013; 20:154–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pařízek A, Koucký M, Dušková M. Progesterone, inflammation and preterm labor. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 139:159–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Madaan A, Nadeau-Vallée M, Rivera JC, Obari D, Hou X, Sierra EM, Girard S, Olson DM, Chemtob S. Lactate produced during labor modulates uterine inflammation via GPR81 (HCA(1)). Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017; 216:60.e1–60.e17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shmigol AV, Eisner DA, Wray S. Properties of voltage-activated [Ca2+]i transients in single smooth muscle cells isolated from pregnant rat uterus. J Physiol 1998; 511:803–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wray S, Prendergast C. The myometrium: from excitation to contractions and labour. Adv Exp Med Biol 2019; 1124:233–263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Li Y, Li H, Xie N, Chen R, Lee AR, Slater D, Lye S, Dong X. HoxA10 and HoxA11 regulate the expression of contraction-associated proteins and contribute to regionalized myometrium phenotypes in women. Reprod Sci 2018; 25:44–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chow L, Lye SJ. Expression of the gap junction protein connexin-43 is increased in the human myometrium toward term and with the onset of labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1994; 170:788–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Slater DM, Dennes WJ, Campa JS, Poston L, Bennett PR. Expression of cyclo-oxygenase types-1 and -2 in human myometrium throughout pregnancy. Mol Hum Reprod 1999; 5:880–884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arrowsmith S, Wray S. Oxytocin: its mechanism of action and receptor signalling in the myometrium. J Neuroendocrinol 2014; 26:356–369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Brar HS, Platt LD, DeVore GR, Horenstein J, Medearis AL. Qualitative assessment of maternal uterine and fetal umbilical artery blood flow and resistance in laboring patients by Doppler velocimetry. Am J Obstet Gynecol 1988; 158:952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Larcombe-McDouall J, Buttell N, Harrison N, Wray S. In vivo pH and metabolite changes during a single contraction in rat uterine smooth muscle. J Physiol 1999; 518:783–790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wray S, Alruwaili M, Prendergast C. Hypoxia and reproductive health: hypoxia and labour. Reproduction 2021; 161:F67–F80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alotaibi M, Arrowsmith S, Wray S. Hypoxia-induced force increase (HIFI) is a novel mechanism underlying the strengthening of labor contractions, produced by hypoxic stresses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2015; 112:9763–9768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Loboda A, Jozkowicz A, Dulak J. HIF-1 and HIF-2 transcription factors--similar but not identical. Mol Cells 2010; 29:435–442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Semenza GL, Koury ST, Nejfelt MK, Gearhart JD, Antonarakis SE. Cell-type-specific and hypoxia-inducible expression of the human erythropoietin gene in transgenic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1991; 88:8725–8729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Schönenberger MJ, Kovacs WJ. Hypoxia signaling pathways: modulators of oxygen-related organelles. Front Cell Dev Biol 2015; 3:42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Huss JM, Levy FH, Kelly DP. Hypoxia inhibits the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/retinoid X receptor gene regulatory pathway in cardiac myocytes: a mechanism for O2-dependent modulation of mitochondrial fatty acid oxidation. J Biol Chem 2001; 276:27605–27612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Rankin EB, Rha J, Selak MA, Unger TL, Keith B, Liu Q, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol 2009; 29:4527–4538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Qu A, Taylor M, Xue X, Matsubara T, Metzger D, Chambon P, Gonzalez FJ, Shah YM. Hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 2α promotes steatohepatitis through augmenting lipid accumulation, inflammation, and fibrosis. Hepatology 2011; 54:472–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Grange RW, Meeson A, Chin E, Lau KS, Stull JT, Shelton JM, Williams RS, Garry DJ. Functional and molecular adaptations in skeletal muscle of myoglobin-mutant mice. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2001; 281:C1487–C1494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Keränen MA, Nykänen AI, Krebs R, Pajusola K, Tuuminen R, Alitalo K, Lemström KB. Cardiomyocyte-targeted HIF-1alpha gene therapy inhibits cardiomyocyte apoptosis and cardiac allograft vasculopathy in the rat. J Heart Lung Transplant 2010; 29:1058–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guo H, Zheng H, Wu J, Ma HP, Yu J, Yiliyaer M. The key role of microtubules in hypoxia preconditioning-induced nuclear translocation of HIF-1α in rat cardiomyocytes. PeerJ 2017; 5:e3662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mittal P, Romero R, Tarca AL, Draghici S, Nhan-Chang CL, Chaiworapongsa T, Hotra J, Gomez R, Kusanovic JP, Lee DC, Kim CJ, Hassan SS. A molecular signature of an arrest of descent in human parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2011; 204:177.e15–177.e33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chaemsaithong P, Madan I, Romero R, Than NG, Tarca AL, Draghici S, Bhatti G, Yeo L, Mazor M, Kim CJ, Hassan SS, Chaiworapongsa T. Characterization of the myometrial transcriptome in women with an arrest of dilatation during labor. J Perinat Med 2013; 41:665–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chen L, Wang L, Luo Y, Huang Q, Ji K, Bao J, Liu H. Integrated proteotranscriptomics of human myometrium in labor landscape reveals the increased molecular associated with inflammation under hypoxia stress. Front Immunol 2021; 12:722816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Talley JJ, Brown DL, Carter JS, Graneto MJ, Koboldt CM, Masferrer JL, Perkins WE, Rogers RS, Shaffer AF, Zhang YY, Zweifel BS, Seibert K. 4-[5-Methyl-3-phenylisoxazol-4-yl]- benzenesulfonamide, valdecoxib: a potent and selective inhibitor of COX-2. J Med Chem 2000; 43:775–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Sanu O, Lamont RF. Critical appraisal and clinical utility of atosiban in the management of preterm labor. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2010; 6:191–199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Walrave L, Pierre A, Albertini G, Aourz N, De Bundel D, Van Eeckhaut A, Vinken M, Giaume C, Leybaert L, Smolders I. Inhibition of astroglial connexin43 hemichannels with TAT-Gap19 exerts anticonvulsant effects in rodents. Glia 2018; 66:1788–1804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Anamthathmakula P, Kyathanahalli C, Ingles J, Hassan SS, Condon JC, Jeyasuria P. Estrogen receptor alpha isoform ERdelta7 in myometrium modulates uterine quiescence during pregnancy. EBioMedicine 2019; 39:520–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Yu L, Ji KY, Zhang J, Xu Y, Ying Y, Mai T, Xu S, Zhang QB, Yao KT, Xu Y. Core pluripotency factors promote glycolysis of human embryonic stem cells by activating GLUT1 enhancer. Protein Cell 2019; 10:668–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Namekawa T, Kitayama S, Ikeda K, Horie-Inoue K, Suzuki T, Okamoto K, Ichikawa T, Yano A, Kawakami S, Inoue S. HIF1α inhibitor 2-methoxyestradiol decreases NRN1 expression and represses in vivo and in vitro growth of patient-derived testicular germ cell tumor spheroids. Cancer Lett 2020; 489:79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Niemi H, Honkonen K, Korpisalo P, Huusko J, Kansanen E, Merentie M, Rissanen TT, André H, Pereira T, Poellinger L, Alitalo K, Ylä-Herttuala S. HIF-1α and HIF-2α induce angiogenesis and improve muscle energy recovery. Eur J Clin Invest 2014; 44:989–999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Pang Y, Ucuzian AA, Matsumura A, Brey EM, Gassman AA, Husak VA, Greisler HP. The temporal and spatial dynamics of microscale collagen scaffold remodeling by smooth muscle cells. Biomaterials 2009; 30:2023–2031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ayob AZ, Ramasamy TS. Prolonged hypoxia switched on cancer stem cell-like plasticity in HepG2 tumourspheres cultured in serum-free media. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol Anim 2021; 57:896–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Serocki M, Bartoszewska S, Janaszak-Jasiecka A, Ochocka RJ, Collawn JF, Bartoszewski R. miRNAs regulate the HIF switch during hypoxia: a novel therapeutic target. Angiogenesis 2018; 21:183–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Koh MY, Powis G. Passing the baton: the HIF switch. Trends Biochem Sci 2012; 37:364–372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Lee G, Auffinger B, Guo D, Hasan T, Deheeger M, Tobias AL, Kim JY, Atashi F, Zhang L, Lesniak MS, James CD, Ahmed AU. Dedifferentiation of glioma cells to glioma stem-like cells by therapeutic stress-induced HIF signaling in the recurrent GBM model. Mol Cancer Ther 2016; 15:3064–3076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Torres-Capelli M, Marsboom G, Li QO, Tello D, Rodriguez FM, Alonso T, Sanchez-Madrid F, García-Rio F, Ancochea J, Aragonés J. Role OF Hif2α oxygen sensing pathway in bronchial epithelial club cell proliferation. Sci Rep 2016; 6:25357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Semenza GL. HIF-1 and tumor progression: pathophysiology and therapeutics. Trends Mol Med 2002; 8:S62–S67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wenger RH. Cellular adaptation to hypoxia: O2-sensing protein hydroxylases, hypoxia-inducible transcription factors, and O2-regulated gene expression. FASEB J 2002; 16:1151–1162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Masoud GN, Li W. HIF-1α pathway: role, regulation and intervention for cancer therapy. Acta Pharm Sin B 2015; 5:378–389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tan T, Luciano JA, Scholz PM, Weiss HR. Hypoxia inducible factor-1 improves the actions of positive inotropic agents in stunned cardiac myocytes. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2009; 36:904–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tan T, Marín-García J, Damle S, Weiss HR. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 improves inotropic responses of cardiac myocytes in ageing heart without affecting mitochondrial activity. Exp Physiol 2010; 95:712–722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang J, Weigand L, Lu W, Sylvester JT, L. Semenza G, Shimoda LA. Hypoxia inducible factor 1 mediates hypoxia-induced TRPC expression and elevated intracellular Ca2+ in pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells. Circ Res 2006; 98:1528–1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Barnes EA, Chen CH, Sedan O, Cornfield DN. Loss of smooth muscle cell hypoxia inducible factor-1α underlies increased vascular contractility in pulmonary hypertension. FASEB J 2017; 31:650–662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ishikawa H, Xu L, Sone K, Kobayashi T, Wang G, Shozu M. Hypoxia induces hypoxia-inducible factor 1α and potential HIF-responsive gene expression in uterine leiomyoma. Reprod Sci 2019; 26:428–435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Saini A, Sundberg CJ. Chromatin immunoprecipitation of skeletal muscle tissue. Methods Mol Biol 2018; 1689:127–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shchuka VM, Abatti LE, Hou H, Khader N, Dorogin A, Wilson MD, Shynlova O, Mitchell JA. The pregnant myometrium is epigenetically activated at contractility-driving gene loci prior to the onset of labor in mice. PLoS Biol 2020; 18:e3000710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Barnett SD, Asif H, Anderson M, Buxton I. Novel tocolytic strategy: modulating Cx43 activity by S-nitrosation. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2021; 376:444–453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kim SH, Riaposova L, Ahmed H, Pohl O, Chollet A, Gotteland JP, Hanyaloglu A, Bennett PR, Terzidou V. Oxytocin receptor antagonists, atosiban and nolasiban, inhibit prostaglandin F(2α)-induced contractions and inflammatory responses in human myometrium. Sci Rep 2019; 9:5792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Tanaka K, Osaka M, Takemori S, Watanabe M, Tanigaki S, Kobayashi Y. Contraction-associated proteins expression by human uterine smooth muscle cells depends on maternal serum and progranulin associated with gestational weight gain. Endocr J 2020; 67:819–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wray S, Arrowsmith S. Uterine excitability and ion channels and their changes with gestation and hormonal environment. Annu Rev Physiol 2021; 83:331–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Hudson CA, McArdle CA, López BA. Steroid receptor co-activator interacting protein (SIP) mediates EGF-stimulated expression of the prostaglandin synthase COX2 and prostaglandin release in human myometrium. Mol Hum Reprod 2016; 22:512–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005; 102:16096–16101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Döring B, Shynlova O, Tsui P, Eckardt D, Janssen-Bienhold U, Hofmann F, Feil S, Feil R, Lye Stephen J, Willecke K. Ablation of connexin43 in uterine smooth muscle cells of the mouse causes delayed parturition. J Cell Sci 2006; 119:1715–1722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.