Abstract

Heavy alcohol use among people with HIV in sub-Saharan Africa is driven by household economics such as poverty and unemployment and has negative impacts on couple relationships. Multilevel interventions have the potential to reduce alcohol use and improve relationship outcomes by addressing the web of co-occurring economic, social, and dyadic factors. This objective of this study was to develop an economic and relationship-strengthening intervention for couples in Malawi, consisting of matched savings accounts with financial literacy training and a couples counseling component to build relationship skills. Informed by the ADAPT-ITT framework, we collected multiple rounds of focus group data with key stakeholders and couples to gain input on the concept, session content, and procedures, held team meetings with field staff and an international team of researchers to tailor the intervention to couples in Malawi, and refined the intervention manual and components. The results describe a rigorous adaptation process based on the eight steps of ADAPT-ITT, insights gained from formative data and modifications made, and a description of the final intervention to be evaluated in a pilot randomized clinical trial. The economic and relationship-strengthening intervention shows great promise of being feasible, acceptable, and efficacious for couples affected by HIV and heavy alcohol use in Malawi.

Keywords: Economic strengthening, Couples, HIV/AIDS, Antiretroviral therapy, Sub-Saharan Africa

Introduction

Heavy alcohol use is a major health threat for people with HIV (PWH), described as “adding fuel to the fire” of the HIV epidemic [1]. Rates of heavy drinking are alarmingly high among PWH and may be almost twice that of the general population [2]. Alcohol use directly impacts ART adherence and HIV clinical outcomes, and contributes to malnutrition, liver disease, and HIV disease progression [3–7]. In sub-Saharan Africa, individuals who use alcohol report some of the highest per capita alcohol consumption rates in the world [8], despite that the majority of adults abstain from alcohol use.

Economic, Social, and Dyadic Correlates of Alcohol Use in Sub-Saharan Africa

The main drivers and consequences of heavy alcohol use in sub-Saharan Africa are economic, social, and dyadic. At the economic level, the daily stress of poverty is inextricably linked with heavy alcohol use [9, 10]. Population-based data from South Africa showed that people living in poverty with few assets have a higher odds of heavy alcohol use than those with some or many assets [11]. Unemployment, boredom, and coping with a stressful, low-wage job have been documented as reasons for heavy alcohol use [12]. At the social level, barriers to reducing alcohol use include peer pressure and the social benefits of drinking; alcohol use is an active part of social life in many African settings, allowing men to form social bonds and express masculinity [12–15]. On the other hand, positive forms of social pressure from relatives, peers, and healthcare providers is a strong motivator to reduce alcohol use [15, 16].

At the dyadic level, primary partners can influence each other’s drinking behaviors, and alcohol use can be both a cause and consequence of relationship distress [17]. In South Africa, heavy alcohol use was positively associated with poor communication and mistrust in couples [18]. In Malawi, a qualitative study found that men living with HIV who drink alcohol experienced challenges with ART adherence; however, a more striking finding was that women living with HIV, who often did not drink themselves, also faced adherence issues as a result of their husband’s drinking [16]. Women described how alcohol-related violence, food insecurity, and a lack of partner support played a role in missing doses of ART [16]. Moreover, alcohol use can indirectly affect ART adherence and overall health by damaging couple relationships needed for support, survival, and well-being [12, 16]. Alcohol use is a trigger of intimate partner violence (IPV), which is one of the strongest predictors of adherence [19]. While alcohol use can negatively impact the health of both partners, partners can also play an important health-promoting role. In South Africa, partners can mitigate the deleterious effects of alcohol use by helping PWH manage alcohol use and maintain adherence to ART even while drinking [20].

Interventions at the Economic, Dyadic, and Social Levels: Need for Multilevel Approach

Multilevel approaches are needed to address alcohol use among PWH in sub-Saharan Africa. The majority of behavioral interventions have focused on individuals who use alcohol, using approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy or motivational interviewing [21]. A recent meta-analysis based on 21 studies found that such interventions were successful at reducing alcohol use, and had additional benefits on adherence [22]. However, only four of the studies took place in sub-Saharan Africa and the results of these studies were mixed. One of the most promising interventions was a cognitive behavioral therapy intervention in Kenya, which showed significant reductions in alcohol use in a pilot study [23] and full efficacy trial [24]. The intervention used paraprofessionals to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy and emphasized locally-salient motivations for reducing drinking, including economic reasons [25]. To complement individual-level interventions, there is a strong need for approaches that modify the broader socio-economic and dyadic context of drinking.

Economic-strengthening interventions could have meaningful impacts on alcohol use, especially with couples. Savings-based interventions combined with financial literacy training (FLT) may provide a sustainable option by breaking the cycle of poverty through investments, liquid assets, and lifelong financial knowledge [26–28]. In Uganda, the Suubi intervention (also called Bridges) provided incentivized savings accounts combined with FLT to facilitate savings and investments. The intervention had positive impacts on mental health, family cohesion, and sexual risk-taking among adolescents at risk for HIV, and virologic suppression among adolescents living with HIV [29–31]. Given the economic determinants and consequences of alcohol use in sub-Saharan Africa, interventions like Suubi could adapted to target heavy alcohol use, such as by making the FLT curriculum more relevant to people who drink alcohol.

In addition, a focus on couples within saving-based interventions may be particularly effective and synergistic when intervening on the couple relationship and household economics together. Most economic strengthening interventions, including those with micro-savings, have focused solely on empowering women rather than couples [32–34]. By working with both partners together, men may be less likely to view women’s financial activities as a threat to their masculinity and provider roles [35, 36] and respond with control and dominance [32]. Moreover, providing both partners with FLT could reinforce material learned and encourage partners to engage in shared decision-making and take joint responsibility for financial goals. Relationship-strengthening interventions have been effective at reducing alcohol use and addressing HIV-related behaviors. In the US, behavioral couples therapy was more effective than an individual-based approach by addressing the relationship dynamics that intersect with alcohol use [37]. Other studies found that when comparing individuals who drink alcohol heavily, those in the behavioral couples therapy arm reported lower rates of IPV and higher relationship functioning than those in an individual-based arm [38, 39]. In South Africa, one of the few interventions that addressed alcohol use in couples was an HIV prevention intervention known as Couples Health Co-Op [40]. The intervention reinforced couples’ relationships with skill-building exercises around communication and sex. Men in the couples arm were less likely to report heavy alcohol use as compared to the control arm of male-only groups [41]. Another couple-based intervention developed in South Africa, called Uthando Lwethu, which consisted of activities to improve relationship dynamics and build problem-solving and communication skills, was effective at increasing uptake of couples HIV testing and counseling [42, 43].

Conceptual Framework: Integrating Dyadic, Economic, and Social Theory

We posit that gaining relationship skills will help couples work together on financial goals and reduce alcohol use, while increasing savings and financial stability will alleviate stress on couples, encourage planning for the future, and reduce drinking, thereby enhancing couple functioning. In this study, we developed a theoretically-based intervention called Mlambe, named after the mlambe (Baobab) tree in Malawi which is a symbol of strength and life, by adapting and integrating two efficacious interventions focused on strengthening household economics and relationship dynamics. Economic-strengthening activities were based on the Suubi intervention in Uganda, which consisted of incentivized savings accounts and FLT [30, 44, 45]. Relationship-strengthening activities were based on the Uthando Lwethu intervention in South Africa, which consisted of relationship education and skills [42, 43].

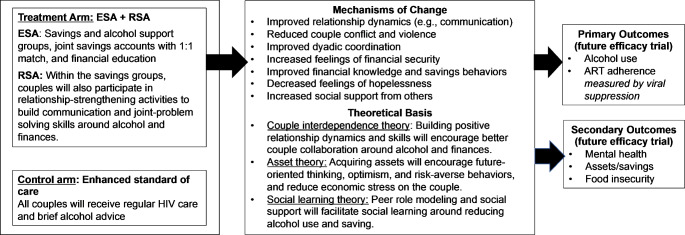

Mlambe will intervene at the dyadic, economic, and social levels of the social-ecological model [46] to impact alcohol use and HIV clinical outcomes (Fig. 1). At the dyadic level, improving relationship dynamics and communication patterns can help couples move from a self-centered to a relationship-centered orientation in which couples interpret health issues as having significance for the relationship. This in turn enables couples to support each other in positive ways to carry out their shared vision and work collaboratively around health issues. At the economic level, asset theory posits that assets such as education, savings accounts, and an income-generating activity (IGA) can change not only household economic status, but behaviors, attitudes, and hope for the future [47, 48]. Because alcohol use is often used to cope with economic stressors and feelings of hopelessness, asset-building could address some of the underlying reasons for drinking. The accumulation of assets may also reduce economic stressors and its negative impact on couple relationships [49–53], creating new opportunities for couples to engage in healthy behaviors together. At the social level, social learning theory argues that new behaviors can be acquired by observing and reproducing the behaviors of others and through social reinforcement [54]. Thus, by including individuals who use alcohol together in a health-promoting and supportive environment, there will be opportunities to learn the best strategies from others, to develop new friendships, and to receive peer support around alcohol use.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual Framework for the Mlambe Intervention

Study Purpose

The purpose of this study was to describe the process of adapting and synthesizing two interventions into a combined economic and relationship-strengthening intervention to reduce alcohol use by employing the ADAPT-ITT framework [55]. Specifically, we describe how we adapted the interventions to address heavy alcohol use, tailored the study procedures and content to the Malawi context, and made modifications to ensure the intervention was relevant for couples. We add to the literature by outlining how to combine interventions operating at different levels of the socio-ecological model. Relationship-focused research grounded in psychology does not typically intervene upon structural or economic factors driving poor couple relationships [52, 53]. Economic approaches, on the other hand, often ignore couple interactions, thereby missing opportunities to harness the power of relationships to overcome and cope with economic constraints at the household level.

The ADAPT-ITT framework was originally designed to adapt a single, evidence-based intervention (EBI) for a new purpose, target population, or setting [55], and has been successfully used to adapt HIV-focused behavioral interventions for adolescents, men who have sex with men, and other at-risk populations [56, 57]. A few more recent studies have used ADAPT-ITT to combine interventions based on two or more EBIs [58, 59], but this is a rare application of ADAPT-ITT and there is still little guidance of the process of integrating EBIs. We build on this work by considering additional adaptation elements for combining multiple EBIs such as spacing and length of sessions to accommodate a larger number of sessions from two interventions; cost considerations to counteract greater participant burden across many visits; the ordering of the two intervention components and how to blend intervention content; and skills and training of facilitators needed to deliver two different interventions.

Methods and Results

Process for Intervention Development

Similar to other intervention development studies for alcohol use [60], we carried out all 8 steps of the ADAPT-ITT 8 steps: Assessment, Decision, Administration, Production, Topic Experts, Integration, Training, and Testing [55]. Table 1 provides a description of each ADAPT-ITT step and a summary of how we implemented each step.

Table 1.

Development of the Mlambe Intervention using the ADAPT-ITT Framework

| ADAPT-ITT Step | Question Answered by Step | Methodology Used |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assessment | Who is the target population and why is alcohol a problem? | • Collected and evaluated mixed-methods data with target population of couples who drink alcohol in Malawi. |

| 2. Decision | What evidence-based intervention (EBI) is going to be selected and is it going to be adopted or adapted? |

• Identified need for combined economic and relationship-strengthening intervention. • Reviewed literature for EBIs, consulted experts, and held team meetings. • Made decision to adapt Suubi for economic component and Uthando Lwethu for relationship component. |

| 3. Administration | What in the EBI needs to be adapted and how should it be adapted? |

• Presented intervention concept to academic experts and key stakeholders for feedback. • Explored elements of the interventions to adapt. |

| 4. Production | How do you produce a draft of the intervention and document adaptations? | • Generated draft of Mlambe manual and curriculum for combined intervention based on existing manuals and materials. Tailored the content for contextual issues in Malawi (literacy issues, common words/phrases) and to specifically address alcohol use. |

| 5. Topic experts | Who can help to adapt the EBI? | • Conducted focus group discussions with couples and key stakeholders for input. |

| 6. Integration | What is going to be included in the adapted EBI that is to be piloted? | • Analyzed focus group discussion (FGD) data to further refine the manual and intervention design. |

| 7. Training | Who needs to be trained and how? | • Generated facilitator training manual and conduct trainings with facilitators. |

| 8. Testing | Was the adaptation successful and how did it improve alcohol outcomes? | • Developed study procedures and data collection instruments for pilot randomized controlled trial to follow. |

Assessment Step: Defining the Target Population and Intervention Needs

Evidence to support the need for Mlambe came from a four-year, mixed-methods investigation of couples living with HIV in Malawi called the Umodzi M’Banja (UMB) project. Couples were recruited from HIV clinics in the Zomba district and were eligible if married/cohabitating, over age 18, and had at least one partner living with HIV on ART who had disclosed their HIV status; the sample has been described elsewhere [61]. The UMB study showed a strong link between alcohol use, relationship dynamics, and ART adherence using survey data collected with 211 couples [16, 20, 62–64]. First, we found that participants who drank alcohol had a lower odds of self-reported ART adherence (AOR = 0.38; p < 0.05). Second, higher levels of relationship unity (AOR = 2.11), satisfaction (AOR = 3.80), and partner social support (AOR = 1.12) were associated with higher adherence (all p < 0.05). Third, participants who reported higher physical (AOR = 0.72; p < 0.05) and sexual IPV (AOR = 0.72; p < 0.05) had lower odds of adherence. Fourth, drinking alcohol was positively associated with higher levels of physical (β = 0.80; p < 0.001) and emotional IPV (β = 0.48; p < 0.01).

Within UMB, we enrolled 23 couples who had a positive Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) screen [65, 66] (score of ≥3 for men and ≥4 for women) in order to identify multilevel barriers and facilitators of alcohol use, and potential intervention options. The sample has been described elsewhere [67]. Men were the primary drinker with few women reporting alcohol use. Wives tried to persuade their partners to reduce their alcohol intake, but were often unsuccessful, citing issues with communication (e.g., not listening, arguing). Effective couple collaboration around alcohol use was constrained by negative peer influence and men’s desire for friendship to cope with economic stressors. Women were primarily concerned about the expense of alcohol and described how alcohol prevented families from meeting basic needs and investing in the future. A major theme among men was the desire for peer groups or an economic intervention to reduce alcohol use. Based on participants’ needs and preferences, we concluded that an intervention should include efforts to improve couple communication around alcohol, economic-strengthening activities for couples, and alcohol support groups [67].

Decision Step: Choosing an Intervention to Adapt

We decided to adapt two EBIs, Suubi and Uthando Lwethu, based on our review of the literature, consultation with experts, and formative work pointing to the need for an economic and relationship-strengthening intervention [16, 68]. Through this process, we learned of the drawbacks of microcredit or finance interventions in Africa (e.g., stress of repaying a loan; increased economic vulnerability when defaulting on a loan) [32, 35, 36], and decided to focus on savings instead of microloans or credit. This led us to choose Suubi, a savings-based intervention grounded in asset theory, for the economic component. For the relationship-strengthening component, we decided to adapt Uthando Lwethu. Although designed to address HIV testing rather than alcohol use, we chose this intervention because of its grounding in dyadic theory and personalized focus on couple communication and problem-solving skills—which were identified as intervention targets in our formative work [16, 67]. The combined intervention would consist of the following components: (1) an incentivized joint savings account at a national bank; (2) FLT covering topics such as banking, saving, budgeting, and debt management; (3) financial goal training and linkage with community-based extension workers to help support IGAs focused on agriculture and livestock raising; and (4) relationship skills education plus one-on-one counseling sessions to gain communication and problem-solving skills to help couples develop plans for reducing alcohol use and improving family finances.

Administration Step: Identifying Content to be Adapted

We held four focus group discussions (FGDs) with thirty key stakeholders to obtain reactions to the intervention concept and identify areas to adapt. Two FGDs were conducted with couples from urban and rural areas (N = 16) who participated in the UMB study. Similar to earlier stages, couples were married, aged 18 or older, had at least one partner with a positive AUDIT-C screen who was living with HIV and on ART. The study PI conducted an FGD with providers in English and a trained research assistant conducted the other FGDs in Chichewa. FGDs lasted between 1 and 2 h and were held in private rooms at clinics or community-based venues. Two FGDs were conducted with HIV care providers (e.g., nurses, clinical officers, clinic volunteers) and traditional leaders such as village chiefs (N = 14), identified through our professional networks. After summarizing the proposed activities based on Suubi and Uthando Lwethu, stakeholders were asked questions around the couple-based approach, whether session topics would be useful for couples and why, and what additional content should be included or modified. The investigative team also wanted feedback on whether the banking approach used in Suubi would work in rural Malawi given long distances to banks and whether alternatives like mobile money (i.e., mobile phone banking using airtime as a currency) would be more acceptable. Finally, the team wanted to explore whether the matched incentive should be done as a group, versus at the individual level, to capitalize on peer support to reduce alcohol use. See Table 2 for other topics. Audio files were transcribed, translated into English, and coded by the study PI using deductive codes derived from the interview guide and inductive codes that emerged from the data.

Table 2.

What Needs to be Adapted? Stakeholder Findings from Administration Step of ADAPT-ITT

| Key Questions Asked | Perceptions from Key Stakeholders | Conclusions and Modifications needed |

|---|---|---|

| What are the challenges around saving, banking, starting a business, and creating a budget? |

• People cannot save because of poverty. • People need a business to save. • People need capital (e.g., loans) to improve their households. • Villagers do not know how to make a budget. |

Address myths that people cannot save into financial literacy sessions. Retain sessions on savings, budgeting, and debts. |

| Will couples be able to work together on saving money and starting a business? | • Men and women often do not communicate around household purchases; men “waste” money because they do not know household needs but sometimes women use the money for frivolous purchases. This causes conflict. | Learning how to create a household budget as a couple will resolve conflict from one member making decisions independently. |

| What are the beliefs around banks, mobile money, microfinance, and loans that we need to address? |

• Banks are not trustworthy; money is taken out for fees that people do not understand. There is no point in saving with banks. • It is hard for the average person to open a bank account. • Banks are for wealthy people. • Village bank loans for businesses can help, but a husband could take the money and “spend it on concubines and beer”. • Mobile money banking makes money too accessible which could be used for alcohol versus depositing money in bank account. |

Address banking myths in financial sessions. Involve bank representatives. Retain focus on formal banking approach. |

| Should we offer the matched incentive as a group-based match or couple-based match? | • Match should be based on what each couple can save, not the group: “everyone should reap what they sow” | Use couple-based (not group-based) matched incentive |

| How to ensure sobriety at sessions? |

• If couples are informed about rules to attend sober, they will comply. • There could be penalties for coming drunk to sessions. |

Establish ground rules around sobriety. |

| Should men and women be separated or stay as a couple? |

• “There should be no secrets between husbands and wives” and thus they should attend sessions together. • Families should budget together so burden does not fall on women. • Couples should be educated together on alcohol and finances so that they are on the same page. |

Do not separate men and women; retain focus on couples. |

| Will couples be open to learning communication skills? |

• Arguments stem from couples not agreeing or respecting each other. • Counselling should be done with each couple one-on-one so couples’ privacy is respected and couples feel open to participate together. |

Retain couples counseling on communication skills. Should be one-on-one with each couple, not in a group. |

| How can we ensure privacy and that people feel comfortable with participating? |

• “HIV is no longer shameful as it was. There are worse diseases.” • People will feel free talking about alcohol in a group. |

Group format for other sessions is acceptable. |

Overall, there was strong support that the intervention would be feasible and acceptable for the target population (see Table 2). Most importantly, participants confirmed the appropriateness of a couple-based approach. When asked if partners should be together or separated for the intervention sessions, the consensus (across all FGDs) was that couples should be intervened upon together. The groups provided several reasons for why a couple-based approach is preferred: because the couple is married/family, to help them agree how to spend money, to prevent one partner from misusing financial resources, to reinforce financial lessons, and to reduce the burden on one partner for making financial decisions. For example, one healthcare provider described how women should be more involved in financial decision-making through a couple-based approach: “Men have the financial mastery in most families. But I believe that this way [the couple approach] can encourage the wife or partner to start taking part in the finances in the home. Because we are trying to make them work together.” All other focus groups had similar views about the importance of involving both partners together on finances. The sessions on relationship skills were deemed equally valuable by all groups, which were believed to help couples avoid disagreements, “enhance love in families by encouraging tolerance of each other”, and to communicate their opinions to one another. One female participant in an FGD with couples said: “This is helpful because if we say family, it means the two, being one flesh. It is also good to know what your spouse likes than to tell your husband what you would like them to do for you. You should agree as husband and wife. This suggestion [to include a session on relationship skills] is good and it may have good results.”

The FLT sessions on savings, budgeting, and debt management were also deemed valuable overall, and several suggestions were made to address local beliefs such as the belief that banks were only for rich people and to obtain buy-in from participants. Mobile money (i.e., storing money in the form of airtime instead of in a formal bank account) was viewed as more convenient, but also perceived as problematic for people who use alcohol since cash could be easily accessed. All four groups believed that the savings match should be at the couple/family level, not group level, so that couples individually benefit based on what they contribute. They agreed that most sessions could be group-based, while others such as the couple counseling sessions should be done individually with each couple for privacy reasons. Overall, the findings confirmed our broader approach and provided input on areas under debate with the design (see Table 2).

Production Step: Drafting the Intervention Manual

Through an iterative process led by the PI, the study team in the US created an outline of intervention sessions, compiled materials from the interventions to adapt, and generated a first draft of the Mlambe manual. The manual included a module on the control arm, which consisted of brief alcohol advice lasting 10–15 min modelled off WHO recommendations [69]. Brief alcohol advice would be delivered immediately following a randomization ceremony with each couple individually using alcohol messages personalized to their AUDIT-C score. For the intervention, we decided on a total of 10 monthly sessions to allow couples sufficient time to save for their IGA over 10 months. We included four sessions on FLT from Suubi (e.g., savings and banking, budgeting, debt management) with a fifth session to provide couples with goal-specific training with community-based extension workers on their selected IGA. We combined these five sessions with three sessions from Uthando Lwethu (i.e., one group session on general relationship dynamics and two couples counseling sessions on communication and problem-solving skills). In Uthando Lwethu, couples are asked to choose an HIV-related topic to practice their communication and relationship skills and we adapted the practice exercises to focus on issues related to alcohol use, savings, and ART adherence. We also added an introductory session to explain the Mlambe intervention and introduce couples to banking so that they had basic knowledge and skills to get started using their bank accounts immediately. Because we posited that couples could save by reducing spending on alcohol, we added a session to understand the harms of alcohol use on health (e.g., including HIV) and relationships, and develop strategies to reduce based on the Indashyikiwa intervention from Rwanda with couples [70]. See Table 3 for an outline of sessions. With the exception of two counseling sessions, all sessions were conducted in groups based on the recruitment block at randomization. Couples would attend sessions with the same cohort across the 10-month period, unless making up sessions in which case they could join another group.

Table 3.

Outline of Mlambe Intervention Sessions

| Number | Session Title | Adapted from | Main Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction to Mlambe, savings and banking, and mobile money | Suubi |

• Building group rapport • Introduction to Mlambe and matched savings • Introduction to bank services and mobile money • Establishing couple banking agreement |

| 2 | Understanding and reducing alcohol use | Indashyikirwa |

• Understanding alcohol harms and impacts on relationships • Strategies for reducing alcohol use |

| 3 | Relationship dynamics and power |

Uthando Lwethu Indashyikirwa |

• Positive aspects of relationships • Appreciating our partners • Expressing heartfelt support • Types of power, balancing economic power |

| 4 | Couples counseling session 1: Introduction to communication and problem-solving skills | Uthando Lwethu |

• Learning the Initiator-Receiver technique • Exploring expectations in the relationship • Introduction to problem-solving and goal setting |

| 5 | Couples counseling session 2: Working together on alcohol issues | Uthando Lwethu |

• Practicing Initiator-Receiver technique • Plan going forward • Goal setting |

| 6 | Bank services | Suubi |

• Perceptions of banks, dispelling myths • Benefits of using a bank • Planning financial goals |

| 7 | Budgeting and spending wisely | Suubi |

• Identifying expenses and sources of income • Developing a financial plan • Creating a budget • Identifying ways to cut spending • Planning financial goals |

| 8 | Savings, asset building, and asset accumulation | Suubi |

• Introduction to savings • Building skills to save • Planning financial goals |

| 9 | Debt management | Suubi |

• Steps in borrowing money • Managing debt and responsible borrowing • Planning financial goals |

| 10 | Goal-specific financial support | Suubi |

• Introduction of Mlambe to extension workers • Overview of extension workers areas of expertise • One-on-one meetings with couples and extension worker to plan for income-generating activity |

The ordering of sessions was determined as follows. We hypothesized that couple communication skills would be needed first so that couples could work collaboratively together on finances and alcohol reduction from the start. Couples would receive an overview of banking in session 1 and alcohol use in session 2, then worked on building their relationships in sessions 3–5 and received FLT in sessions 6–9. During the financial sessions, couples would start planning out the type of IGA that their family will invest in, such as raising cows, pigs, or growing produce to sell at the market. In the last session, community-based extension workers (i.e., government employees who work in communities with training on livestock raising and agriculture) would be invited to learn about the Mlambe study and provide an overview of their knowledge and services to the group. Couples would then be matched with extension workers based on where they live and the type of IGA chosen. Thereafter, the extension workers would meet with couples in their communities to provide further education and assistance on starting their IGA based on their financial goals and circumstances (e.g., advantages and disadvantages of a starting a piggery business over raising goats).

At the first session attended by bank representatives, couples open a joint bank account and then save money every month by making deposits into their bank account. Couples are eligible for a 1:1 match up to $10 per month for each Malawi Kwacha saved. The matched contribution is contingent upon authorized withdrawals for education, business, or medical expenses, which were verified with receipts. Otherwise, unauthorized expenses were deducted from a couple’s matched contribution for that month. To encourage attendance at sessions, couples would need to attend at least 7 out of 10 sessions to receive the matched component at the end of the study but could make up sessions if missed. At the end of each month, bank statements are requested and reviewed and the matched contribution is calculated, tracked in a ledger, and then allocated in separate project bank account containing the matched contribution for all participants. At the end of the 10-month intervention period, participants coordinate with the project staff to make purchases for their family IGA using their individual savings plus matched component. Couples continue working with their extension workers to learn about the most appropriate IGA for their circumstances and financial goals until they are ready to commit to an IGA and invest their savings, which can be done up until the 15-month follow-up visit.

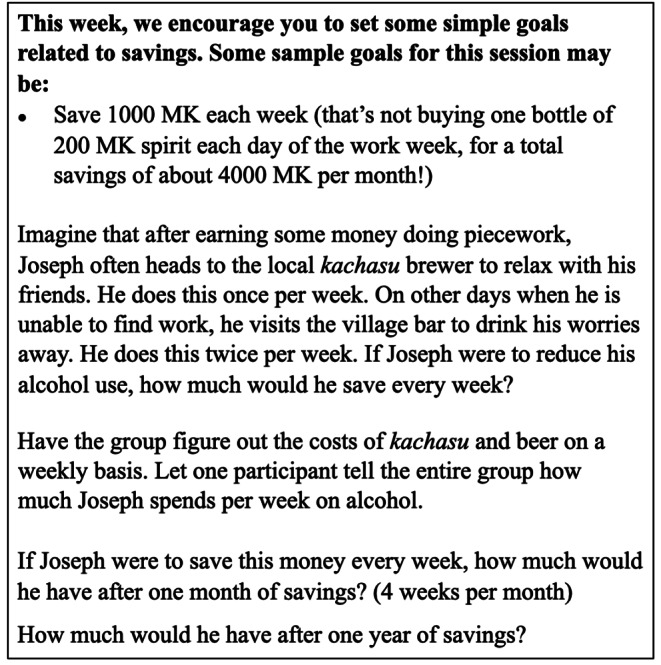

After outlining activities for each session and generating an initial draft of the manual, we tailored the content for couples and incorporated alcohol themes into the activities and examples. For example, in the counseling sessions, practice exercises were revised such that couples could apply their communication skills to issues either alcohol use, savings, or HIV. In the FLT sessions, illustrations and examples were tailored to couples who drink alcohol. For example, in the banking session, there is a story of a woman who instead of putting her money into a bank, kept it in a hiding place at home and then finds out her husband spent the money on alcohol. In the budgeting session, we added an exercise to calculate how much money would be saved per month if alcohol use was reduced (see Fig. 2). We focused adaptations on spurring change around alcohol use rather than HIV-related behaviors because other alcohol interventions have been less successful at addressing alcohol use when intervening on multiple behaviors at once [22] and we believed that improved HIV treatment behaviors would follow from reduced alcohol use. We also believed that addressing HIV behaviors in addition to alcohol use and savings could be overly burdensome and further lengthen an already long intervention. Moreover, in our prior work, participants, especially wives, expressed greater concerns around alcohol use than HIV [68].

Fig. 2.

Example of Adapted Financial Literacy Content to Address Alcohol Use in Malawi

Topic Experts Step: Obtaining Input on the Intervention

To gain further input on the intervention, we held six FGDs with six couples (2 FGDs) and 22 key stakeholders (4 FDGs) consisting of HIV care providers, religious and community leaders, bank, microfinance, and mobile money representatives, alcohol vendors, for a total of 34 participants. We included alcohol vendors who work in bars, bottle shops, brew beer, or make Kachasu (a locally made spirit) because they have important insight into whether the intervention concept would be acceptable, feasible, and appropriate given their direct observations of drinking patterns and behaviors, and the harms of drinking through their regular interactions with patrons. Couples were identified from the UMB study using the same eligibility criteria as above. Key stakeholders were recruited through our professional networks. A trained research assistant conducted the FGDs, which lasted 60–90 min and were conducted in private rooms at clinics or community-based venues. The FGD guide was divided into 12 sections on core features of the intervention (e.g., matched savings accounts), planned intervention sessions from Suubi (e.g., bank services, budgeting, savings, asset building, and asset accumulation) and Uthando Lwethu (e.g., relationship dynamics and power, one-on-one couples counseling sessions), and practical aspects of intervention delivery (e.g., how to tailor materials to low literacy, how to increase attendance and participation). Participants were presented with an overview of each session and then asked a series of questions about what they liked/disliked, what was confusing or unclear, and suggestions for improvements. FGDs were audio-recorded, translated from Chichewa into English, and transcribed into electronic format.

FGD transcripts were coded line-by-line by one of the study authors with qualitative expertise. Using an iterative process, themes were identified from the coded transcripts around the financial, relationship, and alcohol components of the intervention. Three patterns emerged within the themes around likes, concerns, and recommendations. Within these categories, the main themes were selected based on frequency in which they came up across and within the different groups and by their intensity (i.e., not necessarily common, but important or unexpected) [71]. We then looked for agreements and disagreements within and across the different types of stakeholders and weighted the significance of stakeholder recommendations based on their relevant experience of a topic (e.g., bankers would know more about banking than care providers).

Overall, FGD participants expressed many positive sentiments for the intervention. Similar to the first FGDs, and all groups highlighted their appreciation for the couple-based approach (e.g., doing activities together will reinforce the material and help them be more transparent around spending money) (see Table 4). One of the FGDs with couples noted that involving husbands in the FLT sessions could be a challenge since this usually falls within the women’s domain, but they believed it was very beneficial to work with both partners to help avoid quarrels over money. Most groups really liked the financial session on budgeting and found it to be highly relevant for most families, and also believed the session on loans and debt management was important given the many high-interest loans in these communities that could bring financial hardship. Participants were very supportive of the matched savings approach and thought this would be a strong incentive to save and reduce alcohol, although some worried about whether participants would borrow from family or friends to qualify for the match. There were differences in opinions regarding the acceptability of formal banks, with some groups mentioning that it was time-consuming, confusing/difficult to navigate, unexpected fees, and transport could be expensive; while others noted that banks were more secure than village savings and loan programs and other methods to save money in homes where it could be stolen or used to purchase beer. It was noted that with proper education and training, the challenges of using banks for rural families could be overcome.

Table 4.

Who Can Help to Adapt the Intervention? Stakeholder Findings from Topic Experts Step of ADAPT-ITT

| Stakeholder | Likes | Concerns | Recommendations | Modifications made |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol vendors |

• Sessions as a couple • Financial literacy and matched savings • Exercises to reduce drinking |

• Communication skills could be hard to learn • Privacy/safety of funds • Banks are time-consuming, challenges with deposits and withdrawals |

• Include protections for a joint bank account so that one partner cannot steal • Include advice not to bring much money to the beer halls to help curb drinking • Emphasize confidentiality in group sessions • Address issues around transport to bank |

1. Added couple financial agreement on bank withdrawals to first session 2. Tailored alcohol content to provide tips from alcohol vendors 3. Added confidential agreement to first session 4. Included mobile banking agents in rural areas to reduce transport costs 5. Mobile money providers are now invited to first session to provide education on services 6. Meal is provided at each group session 7. To address difficulties travelling to banks, we included village bank agents to assist couples in making deposits and withdrawals 8. Facilitators will have formal education and authority to build trust (e.g., teacher or counselor). 9. Included training on bank loans |

| HIV care providers |

• Teaching people how to save and bank independently • Exercises and vignettes around alcohol use • Counseling sessions and relationship activities |

• People will borrow to get the match • Difficulties accessing bank services in rural areas • Sessions could be too long |

• Include mobile money providers in financial education • Discourage borrowing from friends to get match • Address food insecurity • Address issues around transport to bank |

|

| Religious and community leaders |

• Match will be a strong incentive • Debt management and loan content • Understanding harms of alcohol • Focus on positive aspect of relationships • Working with couples and involve husbands as saving as often falls on wife |

• Concerns about whether people can save in rural areas • People will borrow to get match • Transport to banks is an issue • Banking fees are confusing, missing money from accounts • Mobile money may be preferred over banks |

• Recommend bank accounts require dual signatures for withdrawals • Include mobile money representatives • Facilitators should be experts on financial issues • Emphasize confidentiality in group sessions |

|

| Financial representatives |

• Saving as a couple promotes transparency • Financial skills will give partners tools to solve problems together • Will promote a savings culture • Budget session is important for identifying monthly expenses • Groups will help couples learn from each other |

• Concerns about whether people can save in rural areas • Confidentiality in group sessions • People may not be able to save and will borrow from friends |

• Mobile banking agents can help • Bank representations should do financial sessions • Divorce rates are high; protections are needed so one partner does not take all the savings and leave • Encourage people to save and not take out high interest loans or borrow from friends |

|

| Couples |

• Saving will bring couples closer • Difficult to navigate banking system so this will help • Match incentives • Exercises on alcohol reduction • Focus on positive aspects of relationship • Will help with school fees, a big challenge • Good to learn financial skills together (especially men) • People can learn from other in groups |

• Couple communication exercises should not focus on one partner’s wrongdoings • Financial literacy sessions could be difficult to understand • Men may struggle more, since budgeting often falls on wife • Some people fear the banks • Will need assistance with opening accounts and banking |

• Facilitators should be kind and non-judgmental • Include mobile money providers • Need to promote confidentiality groups • Include a meal at sessions |

Participants had several suggestions of ways to improve the intervention: (1) incorporating mobile money providers to round out the FLT; (2) ensuring group sessions were private and information was not shared outside the group; (3) putting protections in place so that one partner could not withdraw all the savings and divorce the other or spend the money on alcohol; (4) addressing the issue regarding transportation to town centers where banks are located; (5) ensuring that intervention facilitators were knowledgeable, respectful, and non-judgmental; and (6) providing a meal at sessions to increase attention and motivation for attendance (see Table 4 for more details).

Integration Step: Incorporating Input to Refine the Intervention

Based on the topic expert findings, we made the following modifications to the intervention. Rather than enforce strict rules around withdrawals, we empowered couples to negotiate the terms of banking and added a couple financial agreement on bank withdrawals that is negotiated between both partners at the first session to determine who can make bank withdrawals and under what conditions. We involved mobile money providers in the financial sessions as recommended by the FGD participants so that participants can learn about these services and could use mobile money as a channel (but not to replace the formal banking system) to make deposits and withdrawals into bank accounts. Our team’s prior work in Uganda with Suubi found that linking individuals into the formal banking system with bank accounts is important not only for ensuring the money is safe and can earn interest, but also is a step towards accessing a range of banking products that can benefit people. Thus, we maintained our original approach. We incorporated the use of local bank agents (employed by the formal bank) who could assist clients with banking in their villages to avoid transport to town banks.

We also added a confidentiality agreement for all participants to pledge at the first session to protect the information of other group members as much as possible, given that we could not guarantee confidentiality in a group format. Given the long distances traveled by couples to attend the sessions, high levels of food insecurity, and to encourage participation over multiple sessions, we provided a full meal at each group sessions with a lunch activity relevant to the session material on a given day. Finally, we hired facilitators with counseling and/or educational backgrounds who were able to explain complex information on FLT to participants with low education levels (see Table 4). Rather than employ community extension workers to deliver the intervention as done in Suubi, it was noted by FGD participants that facilitators should have the education and skills to gain the respect of participants and be viewed as models of financial success (i.e., community workers were often poor themselves). We also believed that higher education of the facilitators was important to be able to train facilitator to lead sessions requiring different skill sets (e.g., financial literacy and couples counselling).

Training Step: Training Staff to Deliver the Intervention

Intervention facilitators, data collectors, and the research manager were trained over a six-week period by the US study investigators and research coordinator on the research objectives, study procedures, delivery of the intervention sessions and control arm, general facilitation skills, and couples counseling skills. Because the training started in May 2021 when international travel was not possible due to COVID-19 pandemic, we developed a training curriculum that could be delivered remotely using a triad of complementary videos, independent readings, and practical activities to reinforce content. Instructional videos were created in Loom® for each session and could be re-watched as needed by clicking on a web link. Because we were adapting two interventions from Uganda and South Africa, we also held conference calls between the Mlambe investigators and the other study teams in both countries to better understand intervention delivery, challenges on the ground, and implementation procedures, which were recorded and stored, transferred into a link using Loom®, and then used to train the facilitators. Daily conference calls were held between the US research team and the Malawi team to reinforce training material, answer questions on content learned each day, and provide further guidance. Facilitators also conducted mock sessions and a mock randomization ceremony with other study staff to gain practical skills and recorded short videos for the investigators to review and provide further training. While the economic sessions were highly structured and more straightforward to deliver, the couples counseling sessions required more training, especially for the Initiator-Receiver technique, and thus it took several rounds of videos with feedback until the team agreed the facilitators were proficient in their couples counseling skills.

Audio recordings were taken of all intervention sessions; however, given the multiple hours of the sessions and cost and time associated with translation and transcription of large audio files, and because most sessions were highly scripted and structured, we opted to assess intervention fidelity using checklists after each session to confirm that all activities were completed. Weekly calls were also held between the facilitators, project managers, and investigative team in which facilitators presented on each session and explained how activities were received by participants, which helped to ensure the comprehension of the manual, spark conversations around field challenges, and ensure the intervention was being delivered as intended. The research manager attended most intervention sessions to further ensure fidelity to the intervention manual and to assist with session activities and help couples with literacy challenges. Once the investigative team was able to travel again, the study PI, co-investigator, and the Suubi team from Uganda provided additional training on the FLT components and attended intervention sessions to observe operations and provide additional feedback such as giving stretching breaks, encouraging couples to consume refreshments instead of saving for family members, arranging the chairs in the room to foster better participation, and encouraging more engagement among couples.

Pilot Study Step: Testing and Evaluating the Intervention

For the final ADAPT-ITT step, we developed the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for the pilot clinical trial to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention. SOPs covered all study procedures such as informed consent process, ethical procedures, adverse event reporting, monitoring for intimate partner violence, COVID-19 risk reduction, recruitment and enrollment, randomization process, survey data collection, use of REDCap, tracking bank savings and matched savings component, and blood collection and laboratory testing. SOPs were developed through an iterative process between the study investigators and research managers in the US and our implementing partner in Malawi, and were further refined as questions came up during the training in Malawi and during initial rollout of the study.

During the roll-out and pilot testing of the intervention, several implementation challenges came up. It was discovered that couples needed a national identification card to establish a bank account which some did not have. Thus, study procedures were modified such that upon enrollment, the facilitators helped couples obtain documentation needed to apply for ID cards in time for the first session. There were also some challenges with making deposits using village banking agents in which couples deposited the money into the wrong bank account, which led to mistrust and confusion when account balances did not reflect the deposits. The facilitators had to troubleshoot banking issues with couples and work with the bank to correct transaction errors and then re-train couples on entering their account information properly. In another scenario, a husband did not make the deposit as he told his wife and spent the money on other purchases that they did not agree on, which angered the wife when she discovered his lie. Thus, the husband had violated their financial agreement. The facilitators worked with the couple on the misunderstanding, reminding them to use the Initiator-Receiver technique to communicate collaboratively on how deposits should be made going forward. Thus, the communicate techniques became a tool that was used throughout the intervention when disagreements arose between partners, not just during the counselling sessions. In a few cases, the husband sold the phone provided by the study which angered the wife who was committed to the intervention. Couples were not given a second phone in this case and the facilitators counselled the couple to decide whether they wanted to continue in the study (which they ultimately did). Finally, while we had hoped that the group sessions would encourage social cohesion and social support, learning in Malawi is often very top-down and instructive and thus we had to re-train the facilitators to provide FLT in a more engaging way and by encouraging couples to participate in group exercises and encourage more active learning. We provided a lunch after the sessions which we had hoped could also be a time for couples to get to know each other, however, given the extreme poverty in this setting, couples often did not eat the meal and took it home with them to share with family members. Facilitators had to encourage couples to eat the meal so that they could be attentive and reap the full benefits of the FLT.

Discussion

With the growing number of intervention development and pilot studies conducted prior to a full-scale efficacy trial, the process of adapting an intervention is rarely documented and even less is known about how to adapt multiple EBIs into a combined intervention. Through an iterative process, we collected multiple rounds of key stakeholder data, as well as input from the investigative team and field team in Malawi, to obtain feedback on the initial concept, intervention components and sessions, and intervention procedures. This rigorous process produced a structured intervention manual, suite of SOPs, and training plan with videos and a format that can be delivered remotely, in preparation for a future trial of Mlambe to establish efficacy.

This research provides a practical illustration of the types of issues to consider when combining multiple interventions and intervening at multiple levels of the socio-ecological framework. Economic and relationship-strengthening interventions that have worked elsewhere, even within sub-Saharan Africa, must be carefully tailored to the local setting before scale-up. This was important given that Malawi is resource-poor country in sub-Saharan Africa, and even in comparison to other African settings. Our formative work required that we ensure that the same banking, savings, and income-generation elements used in the parent intervention from Uganda could be implemented in rural Malawi. We found that mobile phones and use of local banking agents in the rural areas were essential for couples to be able to make bank account deposits given that transport to the physical banks can be cost-prohibitive. There were additional contextual issues that had to be considered, particularly when working with couples, such as the high rates of divorce in this setting and concerns that one partner could withdraw savings from the joint banking account and exit the marriage or spend the money on alcohol. Thus, we incorporated a couple financial agreement and taught couples the skills to negotiate the terms of their bank accounts as a preventative measure. When developing multilevel interventions using approaches from different academic fields, in our case, economic development and relationship science, it is important to consider the synergies between the two approaches and additions that may be needed to offset the strengths and weakness of each. During the implementation phase, there were instances of couples who violated their financial agreements or made financial decisions without involving the other partner, or had other disagreements, and thus the facilitators needed to remind couples of how to resolve their issues using learned communication skills. This reinforced our decision to augment FLT with relationship skills and to have the couple communication sessions earlier on so that couples had the tools to communicate when financial disagreements transpired. Other lessons learned when combining EBIs include the importance of hiring facilitators with diverse skill sets that are trusted sources of information or with credentials that allow for training on multiple areas such as counseling and FLT.

The adaptation process demonstrated that while some modifications were necessary, the underlying interventions showed promise of being transferrable and implementable in an entirely different African setting and population, even in rural settings like Malawi where access for formal banks can be challenging. While we do not report on participants’ socio-economic status for our pilot study because it is currently ongoing, we expect based on our prior studies that couples will have lower education levels, high food insecurity, and low employment rates [16, 61, 68, 72]. Other modifications would be needed for populations with higher income and employment levels such as, increasing the matched contribution (i.e., higher than $10 USD per month) or changing the types of investments allowed at the end of the study if participants already have assets. Because our participants are underemployed, it was feasible to schedule and conduct group sessions; thus, couples who are formally employed, may not be able to attend sessions during business hours and may have less flexibility, which could require one-on-one sessions. Finally, we worked with married couples living together in the same household which made it more feasible for couples to support each other around alcohol, attend sessions together, and conduct banking and business activities together. Couples from settings with low marriage or cohabitation rates could face more difficulties with coordination of intervention activities and attending sessions and may require more support.

Strengths and Limitations

The strength of our approach was that we used an established adaptation framework and conducted a rigorous study that gathered local input at all stages of the process. While our data suggest that our initial approach may be feasible and acceptable, it was critical to conduct this formative research with a different study population, health behaviors (i.e., heavy alcohol use), and socio-cultural context, as compared to the original interventions. An advantage of using this process is that it maximizes the likelihood that the final intervention will be successful and will allow us to focus our attention on demonstrating efficacy versus implementation in the next steps.

No study is without weaknesses and our study is no exception. As with any method, there is the potential for social desirability bias in which respondents, and even field staff, provide more socially acceptable responses when asked for input on the intervention concept and details of the sessions. Couples and key stakeholders were generally supportive and optimistic of the approach to intervene with both members as a couple but could have been providing more favorable responses to the study investigators. This concern is mitigated, however, by multiple rounds of focus groups, both of which revealed the same theme: intervening with couples has many different benefits and would be well-received and beneficial for families. Our finding is consistent with reports from other studies that participants find couple-based approaches to be enjoyable and valuable experiences for couples to connect [40, 73, 74].

We were also limited by the COVID-19 pandemic in our ability to train staff in-person and oversee study implementation through more frequent field site visits, which could have established better rapport within the team. However, the PI and field staff in Malawi had a long history of collaboration through prior studies and the research manager in Malawi was highly skilled in overseeing study activities and maintained regular communication with the US-based team. The team was in constant communication with daily video calls followed by weekly or monthly calls as activities progressed. This learning experience also resulted in a training curriculum that could be delivered remotely during upcoming COVID-19 surges which may prohibit travel.

Conclusion

Using a proven adaptation model, we synthesized and adapted two efficacious interventions through a collaborative process that actively involved members of the target population, diverse key stakeholders, implementers, and our colleagues in the US, Malawi, Uganda, and South Africa. We learned that it takes a global village to deliver a behavioral intervention at multiple levels and to adapt what worked in other African countries to Malawi. Although the ultimate success of our adaptation will be determined after the trial, we believe this process resulted in a culturally-informed intervention that shows great promise of addressing important multilevel determinants of heavy alcohol use and reducing the harms of alcohol on people with HIV. Our approach is innovative by combining programming from the fields of economics and relationship science to strengthen couple relationships from the ground up, symbolic of the Mlambe tree in Malawi. The process described in this paper provides a practical example for global health researchers working in resource-poor settings around the world on how to develop and implement a complex, multi-component intervention that is feasible and acceptable for a target population.

Author Contributions

AC led the conceptualization and design of this study, led the analysis, and drafted this manuscript. LD, JH, TN, JM, and FS conceptualized the study and edited the manuscript. SM assisted with the analysis and edited the manuscript. ST, NM, and JM assisted with data collection and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the interpretation of findings and approved this manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health under grants R34-AA027983.

Data Availability

Not available due to the potential to identify participants.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There are no conflicts of interest for any of the study authors.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. This study was approved by the UCSF Human Research Protection Program (HRPP) and the National Health Sciences Research Committee (NHSRC) in Malawi.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Consent for publication

All authors approve the publication of this manuscript.

Footnotes

ESA = Economic Strengthening Activities; RSA = Relationship Strengthening Activities

Notes: Kachasu is a locally-made distilled spirit of high alcohol content. MK = Malawi Kwacha

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Hahn JA, Woolf-King SE, Muyindike W. Adding fuel to the fire: alcohol’s effect on the HIV epidemic in Sub-Saharan Africa. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2011;8(3):172. doi: 10.1007/s11904-011-0088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schneider M, Chersich M, Temmerman M, Degomme O, Parry CD. The impact of alcohol on HIV prevention and treatment for South Africans in primary healthcare. Curationis. 2014;37(1):1–8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v37i1.1137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn JA, Samet JH. Alcohol and HIV disease progression: weighing the evidence. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7(4):226–33. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0060-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Williams EC, Hahn JA, Saitz R, et al. Alcohol use and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: current knowledge, implications, and future directions. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016;40(10):2056-72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Hendershot CS, Stoner SA, Pantalone DW, Simoni JM. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Salmon-Ceron D, Lewden C, Morlat P, et al. Liver disease as a major cause of death among HIV infected patients: role of hepatitis C and B viruses and alcohol. J Hepatol. 2005;42(6):799–805. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braithwaite RS, Bryant KJ. Influence of alcohol consumption on adherence to and toxicity of antiretroviral therapy and survival. Alcohol Res Health. 2010;33(3):280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization . Global status report on alcohol and health. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Kagee A, et al. Associations of poverty, substance use, and HIV transmission risk behaviors in three south african communities. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(7):1641–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.08.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dunkle KL, Jewkes RK, Brown HC, et al. Transactional sex among women in Soweto, South Africa: prevalence, risk factors and association with HIV infection. Soc Sci Med. 2004;59:1581–92. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Parry CD, Plüddemann A, Steyn K, et al Alcohol use in South Africa: findings from the first Demographic and Health Survey (1998). J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(1):91 – 7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Setlalentoa B, Pisa P, Thekisho G, Ryke E, Loots Du T. The social aspects of alcohol misuse/abuse in South Africa. South Afr J Clin Nutr. 2010;23(sup2):11–5. doi: 10.1080/16070658.2010.11734296. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Morojele NK, Kachieng’a MA, Mokoko E, et al. Alcohol use and sexual behaviour among risky drinkers and bar and shebeen patrons in Gauteng province, South Africa. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62(1):217–27. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Woolf-King SE, Maisto SA. Alcohol use and high-risk sexual behavior in Sub-Saharan Africa: a narrative review. Arch Sex Behav. 2011;40(1):17–42. doi: 10.1007/s10508-009-9516-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundararajan R, Wyatt MA, Woolf-King S, et al. Qualitative study of changes in alcohol use among HIV-infected adults entering care and treatment for HIV/AIDS in rural southwest Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(4):732–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0918-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conroy AA, McKenna SA, Ruark A. Couple interdependence impacts alcohol use and adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(1):201–10. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2275-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez LM, Neighbors C, Knee CR. Problematic alcohol use and marital distress: an interdependence theory perspective. Addict Res Theory. 2014;22(4):294–312. doi: 10.3109/16066359.2013.841890. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Woolf-King SE, Conroy AA, Fritz K, et al. Alcohol use and relationship quality among south african couples. Subst Use Misuse. 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Hatcher AM, Smout EM, Turan JM, Christofides N, Stocki H. Intimate partner violence and engagement in HIV care and treatment among women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS. 2015;29(16):2183–94. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conroy AA, McKenna SA, Leddy A, et al. “If she is Drunk, I don’t want her to take it”: Partner Beliefs and Influence on Use of Alcohol and antiretroviral therapy in south african couples. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(7):1885–91. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1697-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brown JL, DeMartini KS, Sales JM, Swartzendruber AL, DiClemente RJ. Interventions to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected individuals: a review and critique of the literature. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2013;10(4):356–70. doi: 10.1007/s11904-013-0174-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scott-Sheldon LA, Carey KB, Johnson BT, Carey MP, Team MR. Behavioral interventions targeting alcohol use among people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):126–43. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1886-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Gakinya BN, et al. Treatment outcomes of a stage 1 cognitive–behavioral trial to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected out‐patients in western Kenya. Addiction. 2011;106(12):2156–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03518.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Papas RK, Gakinya BN, Mwaniki MM, et al. A randomized clinical trial of a group cognitive–behavioral therapy to reduce alcohol use among human immunodeficiency virus-infected outpatients in western Kenya. Addiction. 2021;116(2):305–18. doi: 10.1111/add.15112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papas RK, Sidle JE, Martino S, et al. Systematic cultural adaptation of cognitive-behavioral therapy to reduce alcohol use among HIV-infected outpatients in western Kenya. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(3):669–78. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9647-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Swann M. Economic strengthening for retention in HIV care and adherence to antiretroviral therapy: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup3):85–98. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1476665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Swann M. Economic strengthening for HIV prevention and risk reduction: a review of the evidence. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup3):37–84. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2018.1479029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Allen H, Panetta D. Savings groups: what are they. Washington DC: SEEP Network; 2010. p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ssewamala FM, Han C-K, Neilands TB. Asset ownership and health and mental health functioning among AIDS-orphaned adolescents: findings from a randomized clinical trial in rural Uganda. Soc Sci Med. 2009;69(2):191–8. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.05.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bermudez LG, Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, et al. Does economic strengthening improve viral suppression among adolescents living with HIV? Results from a Cluster Randomized Trial in Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2018:1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Ksoll C, Lilleør HB, Lønborg JH, Rasmussen OD. Impact of Village Savings and Loan Associations: evidence from a cluster randomized trial. J Dev Econ. 2016;120:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.12.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacPherson E, Sadalaki J, Nyongopa V, et al. Exploring the complexity of microfinance and HIV in fishing communities on the shores of Lake Malawi. Rev Afr Polit Econ. 2015;42(145):414–36. doi: 10.1080/03056244.2015.1064369. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leatherman S, Dunford C, Metcalfe M et al, editors. Integrating Microfinance and Health benefits, Challenges and reflections for moving Forward. Global Microcredit Summit commissioned Workshop paper; 2011.

- 34.Dworkin SL, Blankenship K. Microfinance and HIV/AIDS Prevention: assessing its Promise and Limitations. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:462–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9532-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slegh H, Barker G, Kimonyo A, Ndolimana P, Bannerman M. ‘I can do women’s work’: reflections on engaging men as allies in women’s economic empowerment in Rwanda. Gend Dev. 2013;21(1):15–30. doi: 10.1080/13552074.2013.767495. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dunbar MS, Maternowska MC, Kang M-SJ, et al. Findings from SHAZ!: a feasibility study of a microcredit and life-skills HIV prevention intervention to reduce risk among adolescent female orphans in Zimbabwe. J Prev Interv Community. 2010;38(2):147–61. doi: 10.1080/10852351003640849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Klostermann KC, Fals-Stewart W. Intimate partner violence and alcohol use: exploring the role of drinking in partner violence and its implications for intervention. Aggress Violent Beh. 2006;11(6):587–97. doi: 10.1016/j.avb.2005.08.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fals-Stewart W, Birchler GR, Kelley ML. Learning sobriety together: a randomized clinical trial examining behavioral couples therapy with alcoholic female patients. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74(3):579. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fals-Stewart W, Clinton-Sherrod M. Treating intimate partner violence among substance-abusing dyads: the effect of couples therapy. Prof Psychology: Res Pract. 2009;40(3):257. doi: 10.1037/a0012708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wechsberg WM, El-Bassel N, Carney T, et al. Adapting an evidence-based HIV behavioral intervention for South African couples. Substance abuse treatment, prevention, and policy. 2015;10(1):6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 41.Wechsberg WM, Zule WA, El-Bassel N, et al. The male factor: outcomes from a cluster randomized field experiment with a couples-based HIV prevention intervention in a south african township. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2016;161:307–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Darbes LA, McGrath NM, Hosegood V, et al. Results of a couples-based randomized controlled trial aimed to increase testing for HIV. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(4):404–13. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darbes LA, van Rooyen H, Hosegood V, et al. Uthando Lwethu (‘our love’): a protocol for a couples-based intervention to increase testing for HIV: a randomized controlled trial in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Trials. 2014;15(1):64. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ssewamala FM, Bermudez LG, Neilands TB, et al. Suubi4Her: a study protocol to examine the impact and cost associated with a combination intervention to prevent HIV risk behavior and improve mental health functioning among adolescent girls in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2018;18(1):693. doi: 10.1186/s12889-018-5604-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ssewamala FM, Neilands TB, Waldfogel J, Ismayilova L. The impact of a comprehensive microfinance intervention on depression levels of AIDS-orphaned children in Uganda. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(4):346–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brofenbrenner U. The Ecology of Human Development Cambridge. MA: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sherraden M, Stakeholding Notes on a theory of welfare based on assets. Soc Serv Rev. 1990;64(4):580–601. doi: 10.1086/603797. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sherraden M. Can the poor save?: saving and asset building in individual development accounts. Routledge; 2017.

- 49.Montgomery BE, Rompalo A, Hughes J, et al. Violence against women in selected areas of the United States. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(10):2156–66. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.302430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goodman LA, Smyth KF, Borges AM, Singer R. When crises collide how intimate Partner violence and poverty intersect to shape women’s Mental Health and Coping? Trauma. Violence & Abuse. 2009;10(4):306–29. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Cássia Ribeiro-Silva R, Fiaccone RL, Barreto ML, et al. The association between intimate partner domestic violence and the food security status of poor families in Brazil. Public Health Nutr. 2016;19(07):1305–11. doi: 10.1017/S1368980015002694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Diamond-Smith N, Conroy AA, Tsai AC, Nekkanti M, Weiser SD. Food insecurity and intimate partner violence among married women in Nepal. Journal of Global Health. 2018;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 53.Conroy AA, Cohen M, Frongillo E, et al. Food insecurity and violence in a prospective cohort of U.S. women at risk or living with HIV. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(3):e0213365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bandura A, Walters RH. Social learning theory:. Prentice-hall Englewood Cliffs, NJ; 1977.

- 55.Wingood G, DiClemente R, The ADAPT-ITT, Model A novel method of adapting evidence-based HIV interventions. JAIDS. 2008;47(S1):40-S6. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181605df1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Latham TP, Sales JM, Boyce LS, et al. Application of ADAPT-ITT: adapting an evidence-based HIV prevention intervention for incarcerated african american adolescent females. Health Promot Pract. 2010;11(3_suppl):53S–60S. doi: 10.1177/1524839910361433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sullivan PS, Stephenson R, Grazter B, et al. Adaptation of the african couples HIV testing and counseling model for men who have sex with men in the United States: an application of the ADAPT-ITT framework. Springerplus. 2014;3(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/2193-1801-3-249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Embleton L, Di Ruggiero E, Odep Okal E, et al. Adapting an evidence-based gender, livelihoods, and HIV prevention intervention with street-connected young people in Eldoret, Kenya. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(12):1703–17. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2019.1625940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Shrestha R, Altice F, Karki P, Copenhaver M. Developing an integrated, brief biobehavioral HIV prevention intervention for high-risk drug users in treatment: the process and outcome of formative research. Front Immunol. 2017;8:561. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]