Abstract

Metal ions or clusters that have been bonded with organic linkers to create one- or more-dimensional structures are referred to as metal–organic frameworks (MOFs). Reticular synthesis also forms MOFs with properly designated components that can result in crystals with high porosities and great chemical and thermal stability. Due to the wider surface area, huge pore size, crystalline nature, and tunability, numerous MOFs have been shown to be potential candidates in various fields like gas storage and delivery, energy storage, catalysis, and chemical/biosensing. This study provides a quick overview of the current MOF synthesis techniques in order to familiarize newcomers in the chemical sciences field with the fast-growing MOF research. Beginning with the classification and nomenclature of MOFs, synthesis approaches of MOFs have been demonstrated. We also emphasize the potential applications of MOFs in numerous fields such as gas storage, drug delivery, rechargeable batteries, supercapacitors, and separation membranes. Lastly, the future scope is discussed along with prospective opportunities for the synthesis and application of nano-MOFs, which will help promote their uses in multidisciplinary research.

1. Introduction

Metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) are produced by the formation of chemical bonds between organic ligands as linkers and metal ions as nodes, leading to generation of periodic network crystalline structures with high porosities and large surface areas, which promote their potential applications in various fields of science and technology.1 In recent years, absorbent materials, zeolites, and MOFs have earned significant consideration in chemical sciences for various applications including energy, sensing and gas storage. The fascinating aspect is the porous property of MOFs, which permits dispersion of recipient particles into a mass structure. The pattern and size of pores administer a choice of pattern and size to accommodate guests.2 MOFs have a flexible design, which offers vast structural variety and broad capabilities to form objects with customized properties.3 They offer an ultimate high porosity, a large internal surface area, structural tailorability, crystallinity, functional diversity, and versatility.4 MOFs exhibit a typically wide inner surface area (frequently 500–7000 m2/g), structural flexibility, tunable porosity, variable organic functionality, and physical/thermal stability, making MOFs a materializing contender to conventional permeable materials, such as activated carbons and zeolites.5 MOFs have remarkably large internal surface areas due to their hollow structure. The interactive effect of arrangements and structures is governed by the physicochemical properties of the constituents. MOFs are attractive illustrations of how the specific design of hollow-structured materials can give an entire raft of good elements. In the late 1990s, MOFs became a fast-growing research field, pioneered by Omar Yaghi at UC Berkeley. More than 90 000 MOF structures have been reported, and the number increases regularly.6 MOFs are absorbent structures designed by the coordination between metal ions and organic linkers.

MOFs are constructed through entrenching a metal ion with organic linkers by coordination (Figure 1), giving unfolded frameworks that exhibit the central vision of endless porosity, a reliable framework, a large pore volume and large surface area. The permeability is the outcome of an extended organic unit that offers an immense storage area and countless adsorption places. Also, MOFs withstand the potentiality to methodically diversify and functionalize their pore structure.7

Figure 1.

Formation of MOF structure by formation of chemical bonds between the metal ions as nodes and the organic molecule as a linker.

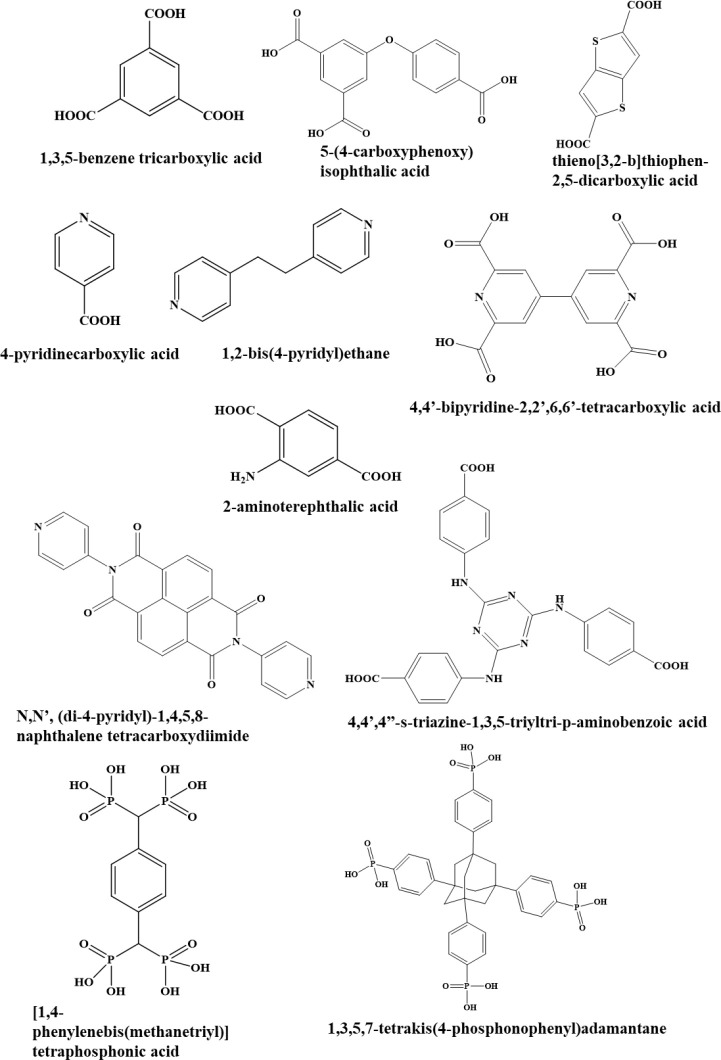

MOFs comprise both organic and inorganic components. The organic components (bridging ligands/linkers) include a conjugate base of a carboxylic acid or anions, such as organophosphorus compounds, salts of sulfonic acid, and heterocyclic compounds as shown in Figure 2. The inorganic elements are metal ions or clusters called secondary building units (SBUs).8 The geometry of the MOFs is considered through ligancy, the analytic geometry of the inorganic components (metal ions), and the organic functional group character. MOFs have been shown to include a variety of shapes, including triangles with three points, square paddle wheels with four points, trigonal prisms with six points, and octahedrons with six points as shown in Figure 3. On a basic level, the organic linker (ditopic, tritopic, tetratopic, or multitopic ligands) responds to the metal ion by means of more than one labile or vacant position. The ultimate framework is reigned over via both the metal ion and the primary building unit (PBU).2

Figure 2.

Organic molecules as linkers used for the preparation of MOFs.

Figure 3.

MOFs with various metal nodes and organic linkers.

The metal ion and bridging ligands might provide diverse outcomes in an assortment of MOFs, customized for typical applications.7 The enormous spaces of MOFs may bring about the improvement of interpenetrating structures. In this way, it is vital to prevent interpenetration by sensibly selecting the PBU. The pore’s size is ensured, and the arrangement of the spatial cavity can be managed by carefully selecting the metal center and organic linkers and via varying the synthesis conditions. MOFs are prepared by several approaches such as solvothermal, microwave-assisted, ultrasonication, mechanochemical, electrochemical, ionothermal, and sonochemical processing. The huge porosity permits their utilization in separation and adsorption of gaseous molecules, microelectronics, catalysis, optics, bioreactors, drug delivery, sensing applications, and so on. A fascinating and remarkable development in this field is MOFs combined with functional nanoparticles, resulting in novel nanocomposite materials with exceptional characteristics and applications. Nanoparticle composite MOFs have various chemical and structural diversities, excessive loading capacity, and high decomposability; thus, they are beneficial to traditional nanomedicines.2 In addition, MOFs and their composite materials have been used as electrocatalysts for the ORR,9−11 carbon dioxide reduction,12 the HER, and the OER.13,14 MOFs have so far attracted a lot of interest in several research fields, both with the aim of developing and synthesizing novel materials as well as for a wide range of applications. In recent years, numerous reviews of electrically conductive MOFs,15 2D MOFs,16 the history of activation and porosity,17 clean energy applications,18 and so on have been published. In this article, we provide a history of MOFs, their classification and the nomenclature of MOFs (i.e., how to classify newly synthesized MOFs from a historical point of view), synthetic approaches for MOFs, and various influencing factors for the synthesis of MOFs. Moreover, their potential applications in various fields such as gas storage, drug delivery, electrochemical energy conservation, and removal of water contaminants are discussed. In addition, the advantages and disadvantages of the synthesis approach for creating MOFs are emphasized. The review comes to a close by outlining several crucial future directions for the creation of nano-MOFs and their applications.

2. Classification and Nomenclature of Metal–Organic Frameworks

2.1. Classification of MOFs

When combined with specific materials, like metal oxides, quantum dots, carbon materials, molecules, polyoxometalates, polymers, and enzymes, one can prepare MOF nanocomposites that have functional diversity. Depending on their component unit, MOFs could be divided into a variety of groupings.19

2.1.1. Isoreticular MOFs

Isoreticular MOFs are synthesized by [Zn4O]6+ SBU and a series of aromatic carboxylates. They are octahedral microporous crystalline materials. In recent years, for the advancement of sensors, IRMOF-3 has been used abundantly. Zhu and co-workers synthesized nanosheets of IRMOF-3 with magnificent sensitivity and selectivity toward recognition of 2,4,6-trinitrophenol in wastewater.20,21

2.1.2. Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks (ZIFs)

Zeolitic imidazolate frameworks are synthesized using various elements that have valence electrons and imidazole derivatives. They are zeolite topological structured materials. ZIFs comprise ZIF-8, ZIF-90, ZIF-L, ZIF-71, ZIF-67, ZIF-7, etc.19 The ZIF-8 material is discussed beyond the diverse ZIF materials due to its dominant performance, such as the sensitivity of the acid, excessive surface area, lower cytotoxicity, immense pore size, etc.22 Pan and co-workers designed a ZIF-8 MOF for detection of the HIV-1 DNA.23 ZIFs have a huge pore size and superior chemical and thermal stability that is used as a network to develop novel MOF composites.24,25

2.1.3. Porous Coordination Networks (PCNs)

Porous coordination networks are stereo-octahedron materials, and they have a hole–cage–hole topology with a 3D structure. Some of the PCNs are PCN-333, PCN-224, PCN-222, and PCN-57.19 One of the PCN MOFs, PCN-222 MOF, is extensively applied in sensors. Ling et al. synthesized a susceptible electrochemical sensor to detect DNA by using PCN-222.26

2.1.4. Materials Institute Lavoisier (MIL) MOFs

Materials Institute Lavoisier MOFs are synthesized using various elements that have valence electrons and an organic compound containing two carboxylic functional groups. The pore size arrangement of MIL MOFs could be converted freely under outward incitement. MIL MOFs contain MIL-101, MIL-100, MIL-53, MIL-88, MIL-125, etc.19 Zhang and co-workers prepared MIL-101(Cr) through a hydrothermal approach to make resistive humidity sensors with elevated sensitivity.27 MIL composites are used as chemical sensors to immobilize proteins, QDs, and other constituents.28−30 Importantly, MILs exhibit several unique features such as ultrahigh surface area, uniform pores and permanent porosity, exploring them as ideal candidates for various applications in biomedical and environmental sciences. Transfer capacity is the structure that prolong between micropores and mesopores under impassion of the exterior influences.

2.1.5. Porous Coordination Polymers (PCPs)

Porous coordination polymer materials are synthesized by carboxylic acid, pyridine, and its derivative as the PBU and transition metal ions as the SBU.19 Ludi and co-workers first synthesized the 3D network assembly of Prussian blue—a PCP.31 Hirai and co-workers immobilized PCP Zn(NO2-ip)(bpy) on the surface of QCM to sense organic vapors.32 PCPs exhibit magnificent characteristics in biomacromolecule separation and heterogeneous catalysis.33,34

2.1.6. University of Oslo (UiO) MOFs

A University of Oslo MOF based on dicarboxylic acid as the PBU and Zr6(μ3-O)4(μ3-OH) as the SBU was first synthesized by Lillerud and co-workers.35 UiO-66(Zr) was constructed by a solvothermal method from ZrCl4 and BDC with octahedral and tetrahedral pore cages.35 UiO-66 had superior thermodynamic stability, and the experimental results showed that the framework is stable at pH = 14. UiO-66 has been successfully used as a supercapacitor electrode material.22

Furthermore, based on the aforementioned classification, numerous MOFs, such as, Northwestern University (NU),36 Pohang University of Science and Technology (POST-n),37 Dresden University of Technology (DUT-n family),38 University of Nottingham (NOTT-n),39 Hong Kong University of Science and Technology (HKUST-n),40 and Christian-Albrechts-University (CAU-n family),41 have emerged in recent years. Biological metal–organic frameworks (Bio-MOFs) are a novel class of permeable materials that has emerged recently.42

2.2. Nomenclature of MOFs

Recently, various constituents which consist of metal ions linked to organic linkers have been reported. These materials are known by various names: metal–organic frameworks, hybrid organic–inorganic materials, metal–organic polymers, coordination polymers, and organic zeolite analogues.3 The word MOF illuminates the presence of an absorbent structure as well as a strong bond responsible for the rigidity of the framework with a distinct geometry where secondary structural units can be replaced throughout the synthesis procedure.43 The MOF abbreviation is generally used as a common name of the class of compound; when it is followed by an ordinal number, it indicates a specific MOF.44−46 Exploring a wide number of structures and MOF properties facilitates formulation criteria for the design of framework structures with impulsive characteristics, for example, with similar symmetry IRMOF-1 and IRMOF-8.49,50 Many MOFs are named not as reported by the similarity of their structure but as reported by the place of their finding, like UiOs,47,48 MILs,53−55 HKUST,56 LICs,57 etc. Furthermore, a huge family of MOF is the zeolite imidazolate framework in which transition metals (Zn, Fe, Cu, Co, etc.) are bonded through N2 atoms and linked with imidazole rings.51,52 Several designations, such as CPL,59 F-MOF-1,60 and MOP-1,58 are used to categorize the research teams that created the MOFs. Table 1 provides examples of the MOFs and their abbreviations.

Table 1. Illustrations of MOF Terms.

| terms | abbreviation | ref |

|---|---|---|

| MOF-2 | MOF | (44) |

| MOF-5 | (45) | |

| MOF-74 | (46) | |

| UiO-66 | University of Oslo | (47) |

| UiO-67 | (48) | |

| IRMOF-1 | isoreticular metal–organic frameworks | (49) |

| IRMOF-8 | (50) | |

| ZIF-8 | zeolite imidazolate framework | (51) |

| ZIF-10 | (52) | |

| MIL-53 | Materials Institute Lavoisier | (53) |

| MIL-88 | (54) | |

| MIL-125 | (55) | |

| HKUST-1 (MOF-199) | Hong Kong University of Science and Technology | (56) |

| LIC-1 | Leiden Institute of Chemistry | (57) |

| MOP-1 | metal–organic polyhedra | (58) |

| CPL-2 | coordination polymer with pillared layer framework | (59) |

| F-MOF-1 | fluorinated metal–organic framework | (60) |

3. Synthesis of MOFs

As discussed before, MOFs are comprised of two significant components: the metal ion and the organic ligands or bridging linkers. Formally, MOFs are created by mildly mixing metal ions with organic linkers to create porous and crystalline materials. During the last couple of decades, different preparation schemes have evolved and been applied to prepare MOFs. These are classified as conventional solvothermal methods, unconventional methods, and alternative methods.61

3.1. Microwave-Assisted Method

Microwave-assisted approaches have been broadly applied for the rapid synthesis of MOFs under hydrothermal conditions. With the help of the microwave process, small metal and oxide particles are produced.62 It provides an efficient way of heating and is derived from the interactivity between the electromagnetic waves and the mobile solvent charges, like polar solvent ions or molecules. This approach is mainly used in organic chemistry and has been extensively used to prepare nanosized metal oxides.63 To design metal nanosized crystals, the temperature of the solution could be elevated through microwaving for 24 h or more (Scheme 1). In this approach, a substrate mixture with an appropriate solvent is put in Teflon vessel, and the vessel is sealed and positioned in the microwave for adequate temperature and time. The task of the microwave is to convert the electromagnetic energy into thermal energy, in which the permanent dipole moment of the molecules is connected with an applied electric field, which rapidly heats the liquid mixture.64 Polar molecules in a substrate mixture attempt to align themselves in an electromagnetic field and an oscillating field, changing their orientations permanently as a result. Applying the right frequency will cause molecules to collide, raising the temperature of the system and the system’s kinetic energy. Due to the radiation interacting directly with the solution or reactant, it is a particularly energy-efficient way of heating. Consideration should be paid to the choice of solvent and particular energy input,65 resulting from uniform size nanocrystals. Microwaves with frequencies between 300 and 300 000 MHz are a sort of electromagnetic radiation.63 Microwave-assisted MOF synthesis is mainly focused on rapid crystallization and formation of nanoscale products to enhance product purity for the particular synthesis of polymorphs.65

Scheme 1. Microwave-Assisted Synthesis of MOF Structures.

3.2. Electrochemical Method

The electrochemical method is used for the rational construction of a vast number of MOFs. HKUST-1 was first synthesized by BASF in 2005 through the electrochemical method.69 Their primary aim was to isolate anions like chloride, perchlorate or nitrate throughout the synthesis procedure, thereby avoiding the formation of corrosive anions (nitrate and chloride), which can be considered that electrochemical method is a green chemistry approach for MOFs preparation bother to extensive construction procedures. Since the synthesis is carried out in the absence of any metal salts, the formation of any corrosive anions like nitrate and by-products are avoided, making the deposition environment friendly. The key component of this technique for MOF synthesis is that metal ions are added through an electrochemical procedure rather than through a solution of the corresponding metal salt or by production of these ions following a metal’s reaction with acid.65 The electrochemical method of MOFs uses electrons as a source of metal ions that are passed through a reaction mixture, which contains dissolved organic linker molecules and an electrolyte via anodic dissolution as the metal source instead of metal salts.62 The electrode is placed in a solution that contains PBU and frequently contains an electrolyte. By giving a suitable voltage, the metal is dissolved and the metal particles essential for the development of MOFs are present exterior to the electrode’s surface. The metal ions instantly respond with the organic linker present in solution, and the MOF is designed near the electrode surface (Scheme 2). By using a protic solvent, the metal deposition on the cathode escapes; however, H2 is produced. The electrochemical route is too feasible to run a consistent procedure to acquire a higher solid content than the ordinary batch reaction.70

Scheme 2. Electrochemical Synthesis of MOF Structures.

3.3. Solvothermal Method

The solvothermal method has been widely used for the preparation of MOFs. This technique is employed due to its simplicity, convenience of usage, crystallinity, and high yield. In this approach, metal salts and organic ligands are stirred in protic or aprotic organic solvents which contain the formamide functionality.73 Aprotic solvents include DEF, DMF, NMP, DMSO, DMA, acetonitrile, and toluene. Protic solvents are methanol, ethanol, and mixed solvents. To keep away from the issues associated with the distinct solubility of the initial components, mixtures of solvents can be used. If water is used as a solvent in MOF synthesis, it is referred as the hydrothermal method.70 This mixture is poured into the closed vessel at elevated pressure and temperature for several hours or a day. Glass vials are used at low temperature, and a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave is used for high temperature (>400 K) in the reaction (Scheme 3). Then, the closed vessel is heated at a temperature greater than the aprotic or protic solvent’s boiling point to bring about higher pressure.73 The chief parameter of this reaction mixture is the temperature, and there are two temperature ranges, i.e., the reaction taking place in a closed vessel above the solvent’s boiling point under autogenous pressure referred to as a solvothermal reaction, and a nonsolvothermal reaction happens below or at the boiling point of the solvent under ambient pressure.74 Due to the high pressure, the solvent is heated above its boiling point and the salt will melt, which then aids the reaction. In addition, to acquire a large crystal with a high internal surface area, slow crystallization from a solution is required.

Scheme 3. Conventional Solvothermal Synthesis of MOF Structures.

3.4. Mechanochemical Method

Mechanochemistry concentrates on responses between solids usually for the most part started just using mechanical energy. A combination of a metal salt and an organic ligand is ground in a ball mill or with a mortar and pestle in the absence of solvent; then, the ground mixture is heated mildly to evaporate other volatile compounds and H2O, which formed as a byproduct in the reaction mixture.61 The mechanochemical approach for the preparation of MOFs is an easier method than the other methods (Scheme 4). In mechanochemical synthesis, chemical transformation takes place through mechanical breaking of intramolecular bonds.79 This reaction exists at room temperature, and organic solvents can be avoided. The first MOF synthesis through this approach was reported in 2006.80 Currently, this method is used on a large scale for the preparation of various kinds of MOFs.

Scheme 4. Mechanochemical Synthesis of MOF Structures.

3.5. Sonochemical Method

Recently, the sonochemical method has been used for rapid synthesis of MOFs as it decreases the time for crystallization through ultraradiation. In this method, a cyclic mechanical vibration (from 20 kHz to 10 MHz) is used for the synthesis of the MOF.83 In a horn-shaped Pyrex reactor with a sonicator bar and a variable power output, a mixture of the metal salt and organic linker is added without the use of external cooling62 (Scheme 5). The main factor for the cavitation’s impact on a liquid is ultrasonic. Cavitation is the name for the development and collapse of bubbles created in a solution after sonication. It produces very fine crystallites at very high temperatures of about 5000 or 4000 K and high pressures of 1000 bar. In 2008, sonication was used for the first time for the synthesis of MOFs.84Table 2 provides examples of MOFs prepared by various synthetic routes (microwave, electrochemical, solvothermal, hydrothermal, mechanochemical, and sonochemical methods).

Scheme 5. Sonochemical Synthesis of MOF Structures.

Table 2. Overview of Various Synthetic Routes (Microwave, Electrochemical, Solvothermal, Hydrothermal, Mechanochemical, and Sonochemical) for the Preparation of MOFs.

| method | MOFs | metal salt | organic ligand | reaction conditions | ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| microwave-assisted method | MIL-100(Fe) | FeCl3·6H2O | H3BTC | (66) | |

| Fe-MIL-53 | FeCl3·6H2O | H2BDC | 80 W, 5 min at 50 °C | (67) | |

| Hf-UiO-66 and Zr-UiO-66 | HfCl4 and ZrCl4 | H2BDC | 90 W, 3 min | (68) | |

| electrochemical method | MOF-199 | Cu electrode | H3BTC | electrolyte: TBATFB, 12 V for 1.5 h | (71) |

| Al-MIL-100 | Al(NO3)3·9H2O | H3BTC | electrolyte: KCl, 50 mA, 333.15 K | (72) | |

| solvothermal method | Eu–MOF | Eu (NO3)3 ·6H2O | H3TATAB | 72 h at 120 °C | (75) |

| MOF-5 | Zn(NO3)2·6H2O | H2BDC | 4 h at 120 °C | (76) | |

| hydrothermal method | NH2-UiO-66 | ZrCl4 | 2-amino terephthalic acid | 24 h at 120 °C | (77) |

| Cr-MIL-101 | Cr(NO3)3·9H2O | H2BDC | 8 h at 220 °C | (78) | |

| mechanochemical method | MOF-74 | Mg(NO3)2·6H2O | H4dobdc | 5 min | (81) |

| MIL-78 | yttrium hydride | trimesic acid | (82) | ||

| sonochemical method | MOF Zr–fum | ZrOCl2·8H2O | fumaric acid | 30 min | (85) |

| [Zn2(oba)2(bpy)] | Zn(NO3)2·6H2O | H2oba, bpy | 60 min | (86) |

Apart from these, other methods such as the diffusion method, spray-drying synthesis, ionothermal synthesis, and chemical vapor deposition have been used for the synthesis of MOFs.87 In the spray-drying method, atomization of a solution consisting of MOF precursors into a microdroplet spray is performed using a two-liquid nozzle. The process injects one or more solution in the inner nozzle at a definite speed (feed rate). The outer nozzle compresses air or nitrogen at another constant speed (discharging rate). Then, each atomized droplet is heated at a specific temperature through a gas and starts to evaporate. Solvent evaporation increases the precursor’s concentration at the surface until large particles of MOFs begin to form.88 The diffusion method is divided into two phases: (i) gas-phase and (ii) liquid/gel-phase diffusion. In this method, diffusion of one of the reagents has a controlled reaction rate. Gas-phase diffusion consists of an organic ligand solution with a low boiling point being used as the solvent. In liquid-phase diffusion, the metal ion and organic ligand are dissolved in immiscible solvents. In the gel-phase diffusion method, the metal ion and organic ligand are dispersed in a gel substance and crystallization begins. This method is often performed under moderate conditions but is a time-consuming reaction.70 In ionothermal synthesis, an ionic liquid acts as both the solvent and the structure-directing agent. Here, an ionic liquid is used as a charge balance group, structural template, or reaction medium. Thus, the ionothermal method provides a pure ionic environment. The physicochemical characteristics of MOFs can be measured by altering the composition of the ionic liquid. Some merits of this method are a lower melting point, good thermal stability, and varied liquid range.89 CVD is also known as a solvent-free method which is used to make crystalline materials in the semiconductor industry. This method has two steps: in the first step, atomic layer deposition via vaporized metal and oxygen or water precursors forms a metal oxide thin film, and in the second step, vaporized ligand sources are introduced to transform the metal oxide film and crystals begins to form.90 However, each MOF synthesis has some merits and demerits. The solvothermal method is a one-step synthetic approach that gives single crystallinity at a moderate temperature.91 On the other hand, this method takes a long period of time, requires more solvents, and produces acids as byproducts.92 In the microwave-assisted method, MOFs are generated with a uniform morphology by means of rapid crystallization in less time and also give a high yield in particular phase purity. It is challenging to change the reaction conditions by controlling the irradiation power. Reproducibility is eventually hindered by the inability of the many instruments to simulate the same variables; as a result, the temperature and reaction time are also limitations of the microwave-assisted method.93,94 The electrochemical method generates more solids compared to the batch process and can be applied as an industrial approach to form MOFs.95 It has been noted that the MOFs produced by the electrochemical method are of lower quality since the linker molecules and/or conducting salt were included in the pores during crystallization.96 There are numerous reasons to be interested in mechanically activated MOF synthesis. Environmental concerns are thus one of the important points. Reactions can be performed with solvent-free conditions at room temperature, which is particularly helpful in situations by avoiding organic solvents. It is possible to produce MOFs with few components and to achieve quantitative yields in a short amount of time.97 Moisture is the main challenge in the synthesis of MOFs via the mechanochemical method. Single crystallization and a lower pore size are limitations of the mechanochemical method.98 Sonochemical synthesis in MOF chemistry is developing a technique that is rapid, energy efficient, eco-friendly, simple to use, and operable at room temperature.99 Crystal decomposition happens during the long reaction time of the synthesis of the MOFs.100 Currently, particular attention is given to the synthesis of MOFs to step up the crystallization of MOFs by rapid reactions. Merits and demerits of various synthetic approaches for the preparation of MOFs are described in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Merits (in green) and demerits (in red) of various synthetic routes for preparation of MOFs.

4. Influencing Factors for Synthesis of MOFs

The synthesis of MOFs has been affected by several exterior factors, such as the selection of organic ligands, metal ion salts, molar ratio, pH, solvents, and temperature of the reaction media.101 Organic ligands can be categorized into a number of types based on their coordinating groups, including carboxylic acid-based linkers, nitrogen-containing heterocyclic, phosphoryl, and sulfonyl linkers, cyano linkers, etc. Carboxylic acid-based linkers are among the different organic linkers, and they are frequently chosen as multifunctional organic linkers as they have many coordination nodes to act as H-bond acceptors and donors to metal ions, which allow for a variety of structural topologies to assemble MOF structures.102 Heterocyclic linkers that contain an N atom have distinct coordination patterns, which increase the target compound’s capacity to be controlled structurally.103 For the fabrication of novel MOF structures, mixed linkers are another option for creating new MOFs that have novel structures.104 One of the typical methods to produce higher dimensional networks is to extend the metal carboxylate complexes with a second bridging ligand. Moreover, the structure of MOFs may be significantly impacted by the positional the isomerism of ligands with the same coordination groups but located in different places. For instance, the aromatic dicarboxylic acids H2IPA and H2TPA both have the tendency to bind and are engaged in controlling the MOFs’ structural assembly.105 The linker L combined with these two linkers to form {[Zn(L)(IPA)]}n and {[Zn(L)(TPA)]·DMF}n complexes with the Zn2+ metal ion, respectively, via the solvothermal method. The H2IPA linker combines with L and forms 1D chains of {[Zn(L)(IPA)]}n, and the H2IPA is replaced by H2TPA, which forms a 3D structure of {[Zn(L)(TPA)]·DMF}n. The selection of the metal salt plays a significant role in the synthesis of MOF structures. Salts utilized as metal sources can be divided into two categories: inorganic acid salts and organic acid salts. Most of the inorganic salts used are carbonates, sulfates, and nitrates, and the organic salts are mostly acetates and their derivatives.106 For instance, [Cu3(btc)2] was prepared by using two different metal salts Cu(OAc)2 and Cu(NO3)2 and H3BTC as the organic linker. The result revealed that Cu(OAc)2 was favorable for the preparation of [Cu3(btc)2] with a high surface area.107 In addition, by adjusting the metal ions and the coordination modes of the organic ligands, it is possible to predict the topology of the MOFs; also, the stability of the MOF is generally improved by the presence of numerous metal ions that are connected by various coordinating ligands. The metal ions serve as the MOF’s construction node and have a direct impact on the structures of MOFs through their coordination geometry. In the synthesis of MOFs, the concentration of the precursors (molar ratio) is also a significant factor. The topological patterns of MOFs are mostly dependent on the ratio of metal ions and organic linkers.101 Liu and co-workers explored the effect of the metal to linker molar ratio on the synthesized MOF structure by using CoCl2 and btze.108 The result showed that the initial materials with a molar ratio of Co(II)/btze of 1:1 or 1:1.5 form 2D [Co(btze)2(SCN)2]n MOFs. When they used a molar ratio of 1:2 or more btze linker, a 3D [Co(btze)2(SCN)2]n MOF structure resulted. Various coordination modes can be adopted by organic linkers at different pH ranges.109 Moreover, as the pH value rises, the linker deprotonates to a greater extent. For example, by raising the pH, the Al3+ ion coordinates with 4, 6, and 8 −COOH groups, yielding MIL-121 (at pH 1.4), MIL-118 (at pH 2), and MIL-120 (at pH 12.2), respectively.110 Spectroscopic data revealed that MOFs are formed with an interpenetrated network at higher pH and were uninterpenetrated at a lower pH.111 The color of the MOF compounds also depends on the pH of the reaction medium. Luo and co-workers, via their experimental work, analyzed three Co–MOF complexes, viz. [Co2(L′)(HBTC)2·(μ2-H2O)·(H2O)2]·3H2O (1), [Co3(L′)2·(BTC)2]·4H2O (2), and [Co2(L′)·(BTC)·(μ2-OH)·(H2O)2] ·2H2O (3), which different structures and colors upon varying the pH.112 These three MOFs also showed different adsorption capabilities. It is also known that materials of higher dimensions are formed at higher pH.113

The solvent plays a significant part in the synthesis of MOFs and also in morphology determination of the MOFs. Solvents are coordinated through metal ions as a structure-directing agent. In view of this, solvents with a polar nature and higher boiling points are widely used in MOF synthesis. Generally, solvents like DEF, DMF, DMSO, DMA, acetone, alcohol, acetonitrile, etc., are used.114 The MOF preparation process was affected by the reaction medium due to the solubility, solvent polarity, and protolysis behavior of the organic ligand. The different solvents in the same reaction conditions provide different morphologies.61 Banerjee and co-workers reported MOFs containing magnesium and PDC having various crystal structures prepared under the same conditions using different solvents115 (DMF, H2O, EtOH, and MeOH) (Figure 5). They found that the MOF network’s dimensionality is determined by the solvent’s capacity to coordinate with the metal. Among them, H2O has the highest attraction toward Mg, whereas other solvent mixtures (EtOH:H2O and DMF:MeOH) did not coordinate with the metal centers, signifying that the use of water as a solvent greatly influenced formation of covalent bonds with the metal ions.

Figure 5.

Influence of solvent systems on the morphology of the MOF. Reproduced with permission from ref (115). Copyright 2011 American Chemical Society.

The temperature is another critical factor which affects the characteristics of the synthesized MOFs. Due to the reactant’s good solubility and the production of large crystals with high superiority, the material exhibits a high crystallization nature at high temperatures. The temperature of the reaction mixture is affected by the nucleation and crystal growth rates. On varying the reaction temperature, the morphology of the MOF is significantly changed, which allows one to use them for different applications.61,116 To support this, monoclinic and triclinic morphological Tm–succinate MOFs have been successfully synthesized at diverse temperatures using the same empirical formula.117 Bernini and co-workers investigated the thermal stability of Ho–succinate MOFs prepared via the hydrothermal approach at higher temperature and at room temperature, illustrating that a Ho–succinate MOF prepared via the hydrothermal approach is more thermally stable than a Ho–succinate MOF prepared at room temperature.118

5. Application of MOFs

In MOFs, there are three properties acting simultaneously, namely, the crystalline nature, porosity, and presence of strong metal–ligand interaction. A rare combination of these properties makes MOFs an exceptional class of materials. The high surface area, small density, structural flexibility, and tunable pore functionality of MOFs makes them useful in a broad range of intending applications, such as in gas storage and delivery, drug delivery, rechargeable batteries, supercapacitors, separation membranes, catalysis, sensing, etc.119

5.1. Gas Storage and Delivery

Due to the unique structure of MOFs, the key application is gas storage because of their large surface area and absence of dead volume.120 This outcome could be noticeable and relies on the pressure, temperature, and type of gas used. The MOF material also plays an important role for this application. Energy-oriented smart applications of MOFs are hydrogen and methane storage, carbon dioxide capture, and nitrogen adsorption.121 Molecular hydrogen has more energy than any fuel. The storage and movement of hydrogen gas needs a large amount of energy compression and liquefaction processes due to the very low energy density. MOFs draw attention as a result of their high surface area, surface to volume ratios, and chemically tunable structures.122 A gas cylinder with a MOF material could store more hydrogen at a specified pressure in comparison to an empty gas cylinder because a molecule of hydrogen adsorbs on the MOF surface.

As MOFs have no dead volume, there is no loss of storage capacity as an outcome of space blocking by an inaccessible volume. When the hydrogen is in the gaseous state, MOFs provide optimum benefits of storage capacity, which is restricted in the liquid state.123 The magnitude of gas that can be adsorbed to the MOF surface relies on the pressure and temperature of the gas. Typically, the adsorption rises when the temperature decreases and the pressure increases (maximum 20–30 bar, after this the capacity of adsorption is reduced). Férey’s group reported a hydrogen capacity of 3.8 wt %, i.e., MIL-53, which is obtained by using aluminum salts and 1,4-benzene dicarboxylic acid.124 A 2.0 wt % hydrogen storage capacity was reported by Kim and Seki derived from pillaring with secondary amine linker (triethylenediamine) at 87 K and 1 bar. Similar values were attained by MOF-505 by Yaghi’s group in which Cu metal is bound by 3,3′,3,5′-biphenyl tetracarboxylic acid. A zinc MOF made with NTB linker may absorb 1.9 wt % of hydrogen at 77 K.125 Hydrogen storage data are recorded up to 7.5 wt %, i.e., MOF-177, at 90 bar.126 However, to date, it is uncertain whether high surface area MOFs like MOF-100, MIL-177, and MOF-5, compounds with a moderate surface area of between 1000 and 1500 m2 g–1, isoreticular compounds, or a uniform small pore size MOF will be the most favorable storage medium.121 However, a comparison with NaX-zeolites evidently shows the best nature of MOFs on conventional microporous inorganic media.127 MOF-177 shows maximum favorable results for the storage of hydrogen (7.5 wt % at 77 K up to 40 bar). The two main schemes directing the MOF’s design for hydrogen storage are (i) to expand the theoretical storage capability of the MOF materials and (ii) to carry out working situations nearer to the surrounding pressure and temperature.126

5.2. Biomedical Applications

In the key area of health there are many therapeutic disadvantages of APIs, i.e., unfavorable solubility and stability, less bioaccessibility, short-term half-life, and restricted bypassing of biological barriers; because of these reasons, their therapeutic uses are primarily finite. In drug delivery, promotion of an effective drug delivery system is one of the dominant areas of research which ensures a favorable result by using safe carrier materials.128 To date, numerous transit materials have been accounted for and structured in various forms, such as carbon dots,129 nanoemulsions,130 hydrogels,131 micelles,132 liposomes133 etc. Yet, a greater number of transit materials frequently have low drug loading capacities, intolerable toxicity, unbound release, and an unstable morphology. To overcome these difficulties, MOFs are investigated as carriers for conveying loaded cargoes to admired sites due to their plausible size, composition, and functionalized pore surface.134 MOFs as feasible drug delivery materials have the following unique advantages: (i) excessively adjustable properties and pore size, (ii) elevated drug loading capacity, and (iii) manageable multifunction.128 The MIL group is a favorable class of MOFs for drug delivery which is acquired from trivalent metal ions and carboxylate linkers, offering a huge pore size (24–25 Å) and applicable surface area (3100–5900 m2/g). For example, MIL-53(Fe) and MIL-53(Cr), two typical MOFs, have been reported to load ibuprofen (IBU) up to 17.4% and show an extended release time of 21 days in simulated body fluid (Figure 6).135 MIL-53(Cr) was prepared by using Cr(NO3)2 and benzene 1,4-dicarboxylic acid, whereas MIL-53(Fe) was synthesized from FeCl3 and benzene 1,4-dicarboxylic acid via a hydrothermal approach.

Figure 6.

Releasing study of IBU from MIL-53(Cr) and MIL-53(Fe). Reproduced with permission from ref (135). Copyright 2008 American Chemical Society.

In this survey study, MIL-53(Fe) had optimum loading capacities of 14 wt % for busulfan and 30 wt % for caffeine. MIL-100(Fe) is also used in drug delivery. Some drugs such as azidothymidine triphosphate (21.1%), DOX (9.1%), cidofovir (16.1%), caffeine (24.2%), and IBU (33%) can successfully load by MIL-100.

5.2.1. Strategies of Drug Loading

There are primarily 3 sorts of drug loading strategies: one-step encapsulation (in situ encapsulation), postsynthesis encapsulation (ex situ encapsulation), and acting as an active molecule in a linker process. Typically, the ex situ encapsulation method is too complicated and time consuming, as stirring the active MOFs and drug for a few days is essential while loading it. However, due to its reliable loading rate, it is still a frequently used method. The one-step encapsulation process has been used for few thermostable drugs and certain MOFs because of the deficient heat stability of the drug and in high concentration drug solution it is difficult to synthesize MOFs.128 Liedana and co-workers discovered two methods for encapsulating caffeine into ZIF-8.136 Here, ZIF-8 was prepared from Zn(NO3)2 ·6H2O and 2-methylimidazole and the CAF@ZIF-8 IN was prepared via the one-step encapsulation method. The caffeine was encapsulated inside the pore of ZIF-8. According to TGA (Figure 7a and 7b), in the ex situ process (CAF@ZIF-8 EX) the contact time was prolonged at 80 °C for 8 h (4.2 1.4%) and in the in situ process (CAF@ZIF-8 IN) the contact time was set at 25 °C for 2 h, resulting in a caffeine load of 28.1 ± 2.6%. Also, to reach a similar result, the contact time must be prolonged about 3 days as t the in situ process was 25 wt % at 80 °C. Furthermore, the crystallinity of the material could be damaged due to a longer encapsulation time.128,136 The UV absorption investigation exhibited only caffeine released from CAF@ZIF-8 EX (8 h) after 3 days; however, it was constantly released from CAF@ZIF-8 IN and CAF@ZIF-8 EX (3 days) for 27 days. Lijia and co-workers fabricated an iron-based MOF MIL-101-C4H4 for the encapsulation and release of DOX.137 First, they prepared MIL-101-C4H4 by using FeCl3 and 1,4-naphthalene dicarboxylic acid through a microwave-assisted method. Then, DOX was added dropwise into the MIL-101-C4H4 in an alkaline medium. The DOX was encapsulated in the pores of MIL-101-C4H4, and the loading capacity was 24.5 wt %, which was completed with a loading efficiency of up to 100% (Figure 7c and 7d).

Figure 7.

(a) TGA plot of one-step and ex situ encapsulation of caffeine in ZIF-8. (b) UV absorption of caffeine delivery from CAF@ZIF-8_EX (8 h), CAF@ZIF-8_EX (3 days), and CAF@ZIF-8_IN in water. Amount of encapsulated caffeine as measured by TGA and UV is shown in the inset table. Reproduced with permission from ref (136). Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society. (c) Schematic representation of DOX-MIL. (d) Loading capacity and loading efficiency of DOX to MIL-101. Reproduced with permission from ref (137). Copyright 2021 American Chemical Society.

In the third strategy, the MOF depends on the active molecular ligands having high loading capacities to avoid toxicity compared to inactive molecular ligands, and these MOFs could simply reach the combination with the drug by loading another drug.128 Zn–MOFs with ligand ferulic acid have been used as in vitro drug carriers for 5-FU.138 The maximum loading capacity of 0.388 g/g was achieved when desolvated MOF was immersed in a 5-FU ethanol solution at a weight ratio of 1:3 for 2 days. Ferulic acid was liberated when 5-FU was released due to the degradation of MOF. A pH-dependency phenomenon was shown by the release of ferulic acid and 5-FU at the same time, which showed that 5-FU was delivered with degradation of {[Zn2(fer)2]}n.

5.2.2. pH-Responsive Drug Delivery Systems

Conventional cancer treatment methods restrict the use of chemotherapy in clinics due to its high toxicity and poor absorption of anticancer medicines.139 The selectivity of an anticancer drug is responsible for the side effects of chemotherapy. Miserably, most of the conventional formulation cannot differentiate between healthy tissue and cancerous tissue in the body. The pH of the physiological nature in cancer tissues was minor compared to that in ordinary tissues.140 Therefore, a pH-responsive drug delivery system was preferred and suitable for cancer therapy. The pH range of this delivery system is from 4 to 6. By a pH-responsive DDS, the drug molecule can be released in the tumor region only. Such a system permits rapid and effective drug release inside the cancerous cells without harm to normal cells and hence decreases the systemic disadvantages of chemotherapy in the human body. Therefore, this pH-responsive DDS which has the controllable release features of MOFs has been identified as favorable in a therapeutic application.128 Adhikari et al. reported a feasible process to encapsulate DOX into ZIF-8 (highly stable at neutral medium) and analyzed its capacity for managed drug release at different pH levels.141 Chowdhuri and co-workers reported a rapid and simple method of an upconversion nanoparticle (i.e., multifunctional nanoparticle) UCNP@ZIF-8/FA to release 5-FU anticancer drug at different pH levels.142 Schnabel and co-workers recently reported Zn–MOF-74, containing Zn2+ ions and the 2,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,4-dicarboxylate ligand, as a drug nanocarrier of As2O3.143 A high amount of drug As(III) (153 mg of As2O3 in 1 g of drug-loaded material) was absorbed into Zn–MOF-74; eventually, the release process of As(III) shows an obvious pH-responsive mechanism. At a temperature of 37 °C, As(III) drug-loaded Zn–MOF-74 was dissolved in PBS, which has two different pH values of 6.0 and 7.4. It was shown that As(III) release was pH stimulated and occurred more quickly at a pH value of 6.0 than at a pH value of 7.4.

5.2.3. Magnetic Drug Delivery

Recently, magnetic nature MOFs have found to be potential candidates for biomedical applications due to high surface area and remarkable response to magnetic field, faovring to store and release of target drug molecules, which also to allows storing and releasing pharmaceuticals, while the magnetic particles provide sensitivity to a magnetic field. A magnetically responsive drug delivery system permits conceivable excellence in magnetic targeting, magnetic separation, magnetic hyperthermia, and MRI.144 Magnetic drug delivery is a classic tactic to improve drug-loaded therapeutic potency.145 MDD is the most promising targeted drug delivery system. With the help of external magnetic conditions, the preparation of magnetic drugs can be kept at a precise position.146 Magnetic properties of MOFs allow them to use as highly potential candidates for drug delivery and bioimaging applications developing contrast agents in MRI also permit the magnetic formulation to possess actual time observing because it can be used for bioimaging as a contrast agent.147 Fe3O4/Fe2O3 and bimetallic alloys have been extensively used as a conventional colloidal magnetic nanoparticle. However, there were some unavoidable drawbacks like poor loading efficiency, instability, and cytotoxicity which restricted the drug delivery application. The customized MOFs with an integrated magnetic component or coordination of magnetic nanoparticles were favorable substitutes in MDD. It has been proved that magnetic MOFs nanoparticles could precisely convey the drug molecules by physical encapsulation or chemical bonding and shows acceptable biocompatibility.148 Ke and co-workers discovered a Fe3O4@MOF-5 core–shell nanomaterial fabricated by Fe3O4 magnetite nanorods and a nanocrystal of MOF-MO-5.149 Then, nimesulide, an anticancer drug, was loaded into Fe3O4@MOF-5. A 20 wt % loading rate was obtained. Furthermore, it was revealed that within 11 days nimesulide was fully loaded into physiological saline from Fe3O4@MOF-5. Guan and co-workers150 discovered an in situ pyrolysis process for the preparation of γ-Fe2O3@MOFs; the ferric triacetylacetonate was encapsulated inside MIL-53(Al) and ZIF-8. Ibuprofen as a standard drug was loaded into γ-Fe2O3@MIL-53(Al) and released in three stages over the course of 7 days at 37 °C. In the first stage, about 30% of the drug was quickly released in the first 3 h; after that, during the next 2 days, 50% of the drug was released; last, 20% of the residual drug was released over 5 days. It was concluded that γ-Fe2O3@MIL-53(Al) was a favorable magnetic material for drug delivery.

5.3. Electrochemical Application

As a unit to form a substance of two different materials, MOF composites have a number of vivid execution and electrochemical applications that MOFs cannot accomplish independently, including batteries, sensing, supercapacitors, and catalysis. Due to the diversity of the MOFs, their composites could enhance the characteristics of the MOF and boost the development of electrochemical applications.151 This is important for the effective use of upright and sustainable energy as well as in the market of transportable electronic and electric vehicles, urging the expansion of energy storing materials, mainly electrochemical energy storage. In light of this, using nanomaterials to store electrochemical energy has proven to be a successful strategy. Nanosized active materials having mechanical and electrical properties and a wide surface area are most likely to imbue the space toward discernment of the forth coming generation of energy storage device. To serve different electrochemical energy storage purposes, many analyses have been executed to look for better methodologies for synthesis of the materials.152 Several functional materials with zero to two dimensions combined with MOFs have extensive applications in electrochemistry, while MOFs fabricated with 3D functional materials have hardly been examined and discussed.152

5.3.1. Lithium-Ion Batteries

Thus far, LIBs have been extensively engaged with a movable electrical apparatus, merged power grids, and electric vehicles because of their merits of eco-friendly performance, having high density, being weightless, and having an extended cycle life, giving them magnificent benefits as energy storage devices.151

Nowadays, aside from graphite (due to the theoretical limit of 372 mA h/g), viable negative electrode materials and several nanostructured materials like graphene composites, carbon nanotubes, transition metal oxides, etc., have been widely explored for applications of LIBs. MOFs have been studied as cathode, anode, and electrolyte materials for LIBs.153 Recent advancements in lithium metal-based anodic batteries have received great attention and suggested that these power sources have enormous potential for revolutionizing the electric vehicle and power grid industries.154 It has been widely reported that N-doped carbon nanomaterials effectively enhance the electrochemical characteristics of carbon materials. A NSPC material was reported for the high performance of Li-ion batteries using a facile and reliable approach.155 This material may function as an anode and provide high-rate cycle performance with a long cycle life. Simple grinding of a mixture of polyacrylonitrile and sublimed sulfur (1:1 mass ratio) leads to the N-rich S-doped porous carbon. The resulting NSPC had an optimum initial Coulombic efficiency of more than 67% and a notable high initial reversible capacity of 1096 mA h/g at a 0.1 A/g current density. A prolonged cycle life of over 1100 cycles with an exceptional cycle performance of 695 mA h/g was observed at a relatively high current flow of 5 A/g. The synergistic effect of heteroatom doping and many mesopores with a significant amount of edge defects, which facilitate extra lithium-ion storage, is responsible for the observed rapid lithium-ion storage. Moreover, porous films of Co3O4 bound with Ti nanowires were also reported for the anodic Li-ion battery.156 The Co3O4 film was synthesized by the pyrolysis of Co–MOFs, and further, it was anchored by the Ti nanowire that effectively supplies a notable rate capability as an anodic Li-ion battery. The homogeneous distribution of carbon in Co3O4 films aids in efficient electron transit, allowing the films to effectively discharge their capacitive potential. In addition, the carbon-containing Co3O4/Ti plate performs superior (400 mAh/g at 20 A/g) to the carbon-free Co3O4/Ti plate (100 mAh/g at 20 A/g) (Figure 8a and 8b). A zero-dimensional MOF composite SnO2@MIL-101(Cr) was reported to show speed capability and peak cyclability of around 510 mA h/g with a 0.1 C reversible capacity after 100 cycles.157 Here, high crystalline MIL-101(Cr) was formed by encapsulating with SnO2, thereby forming SnO2@MIL-101(Cr) that exhibit excellent cyclability and rate capability for Li-ion battery applications. A 2D MOF composite Fe–MOF/RGO was synthesized by Shen et al. for reversible Li+ storage.158 At a 500 mA h g–1 current density and a voltage range of 0.01–3 V, the composites Fe–MOF, Fe–MOF/RGO (5%), and Fe–MOF/RGO (10%) had primary discharge–charge capacities of 2213/786, 2055.9/891.1, and 1889.9/750 mA h/g, respectively, representing 35.5%, 43.3%, and 39.7% of the initial Coulombic efficiency, respectively. The primary Coulombic efficiency of Fe–MOF/RGO (5%) was maximal because RGO was coated on the Fe–MOF to escape instant interaction between the electrode and the electrolyte. Furthermore, the Fe–MOF/RGO (5%) composite was used as an anode that showed maximum Li storage after 200 cycles with a 1010.3 mAh/g reversible capacity. Among them, the Fe–MOF/RGO (5%) electrode exhibited the finest rate capability, showing RGO enhanced the rate performance and cycling stability. Feng and co-workers reported 3D composites Fe3O4@MOF core–shell in LIBs as the anode.159 Fe3O4@MOF showed an elevated discharge capacity of 1001.5 mA h/g in the 100th cycle, which was superior to pure Fe3O4 (696 mA h/g), a charge capacity of 993.7 mA h/g, indicating intense reversible capacity, and a good rate capacity of 492.2 mA h/g, showing prospect in LIBs.

Figure 8.

Cyclic performance of a (a) carbon-containing Co3O4/Ti plate and (b) carbon-free Co3O4/Ti plate at high-rate current. Reprinted with permission from ref (156). Copyright 2018 Elsevier.

5.3.2. Supercapacitor

Supercapacitors (SCs) are different types of ideal energy storing devices with a high power energy storage, longer cycle life, high power density, and excessive packaging flexibility compared to conventional energy storage devices.160 The formation of the supercapacitor is like that for a battery, in which two electrodes are separated by an ion-permeable membrane. Figure 9a shows a schematic illustration of the electron position and charging process in a supercapacitor.161 EDLCs and pseudocapacitors are the two different forms of SCs (can store charges through a reversible Faradaic reaction). The electrostatic adsorption between the surface of the conductive electrode and the electrolytes is what drives the capacitive process in EDLCs. The overall capacitance of pseudocapacitors is produced via redox reactions, intercalation processes, and electrosorption, which involves an electron charge transfer between the electrode and the electrolyte.162

Figure 9.

(a) Schematic representation of electron movement and method of charging, fully charged, and discharging in SCs. Reprinted with permission from ref (161). Copyright 2020 Elsevier. (b) Specific capacitance of NiCo–MOF, Ni–MOF, and Co–MOF at different current densities. Reprinted with permission from ref (165). Copyright 2019 American Chemical Society.

SCs have been broadly used in several research fields due to novel characteristics; thus, the general approval of the ultracapacitor has led to various methodologies to increase the performance. There have been new electrode materials synthesized, surface electrodes have been modified, and hybrid systems have been constructed.163 New types of MOFs with the capacity for structural customization, excess surface area, and absorbency to guest molecules have received boundless attention for use in SCs. One of the critical issues of the MOFs is their conductivity. Primarily, MOFs show less conductivity, which is not beneficial to electrochemical devices. However, when the MOFs are mixed with conducting materials like conductive graphene and polymer, the metal shows high potential as a leading electrode in SCs devices.161 Zhang and co-workers established the method of a SDS Zn–Co–S HC structure and inspected it as an electrode for SCs.164 The elevated surface area, suitable Zn/Co molar ratio of DS Zn–Co–S HC, and weight fraction of the active species resulted in better performance. The improved capacitance is in excess of 1266 F/g at 1 A/g and has a magnificent rate capability for hybrid SCs as battery-type electrode materials. The DS Zn–Co–S maintained a cycling stability of 91% after 10 000 cycles, and single-shelled Zn–Co–S had a 19% capacitance loss under a similar environment. Generally, the electrochemical capability of double-shelled Zn–Co–S was remarkably higher than reported Zn/Co–sulfide-based electrodes for hybrid supercapacitors. The tactics which are essential for the advancement of supercapacitive performance could be compiled as follows: good dispersion of nanoparticles, existence of a hollow shell porous framework, which allows it to detain nanoparticles, a huge channel for smooth movement of electrolyte ions, addition of N2 (nitrogen) or other compounds for optimum electrical conductivity, and availability of conductive networks so electrons can move easily.152 Ultrathin nanosheets of NiCo–MOFs were also used for a high-performance supercapacitor.165 The authors prepared NiCo–MOF nanosheets by an ultrasonication method using NiCl2 and CoCl2 as the metal salt and terephthalic acid as the organic linker. The effective molar ratio of Ni to Co ions in the synthesis of the MOF enhanced the electrochemical properties. The electrochemical reversibility and capacitive performance are shown by the nearly symmetric charge–discharge curves at all current densities. Figure 9b displays the specific capacitances computed from the discharge curves. At the same current density, the NiCo–MOF electrode clearly displays an optimum specific capacitance of 1202.1 F/g at 1 A/g compared to the Ni–MOF (840 F/g) and Co–MOF (650.6 F/g) electrodes. These results demonstrate the ultrathin NiCo–MOF nanosheets’ potential as high-performance supercapacitor electrode materials.

5.4. MOF Membrane for Wastewater Treatment and Water Revival

A MOF made by a metal ion and bridging ligands has been shown to display preferable membrane separation performance. It was noted that the MOF could increase the selectivity based on its accurately determined pore size, while pores could be controlled in a wide series of guest species shapes and sizes.166 Various types of MOFs are available, but the necessary condition for MOFs for use in wastewater treatment and water revival is the stability of MOFs in water. MOFs to be selected as fillers for membranes depend on the following factors: (i) the MOFs have higher selectivity and permeability, (ii) they have uniform and tunable pore structures, (iii) they have greater affinity, and (iv) they can be recycled and reused as fillers in some cases. MOF composite membranes refer to MOFs mixed with polymers as nano- or microparticles to design MOF composite membranes. Polymer-based MOFs overcome cooperation linking with the selectivity and permeability of the polymeric membrane and also increased the thermal stability and mechanical strength of the membrane.167,168 MOFs can act as filler TFN membranes and MMM to construct MOF-based composite membranes for wastewater treatment and water revival. The ideal MOF membranes were tested, but the structural defects in the MOF materials were unavoidable. Hence, how to design a defect to be an ideal MOF membrane is currently under debate. The MOF particles’ surface properties, MOF membrane, and MOF structure limitations have also been studied to be essential factors. Due to the versatile pore diameter of the MOF membranes, they have excellent application possibilities in water treatment. There are MOF membrane applications such as membrane distillation, membrane filtration, and membrane pervaporation, which are described below.169

5.4.1. Membrane Filtration

Membrane filtration is the standard method for separation that permits molecular scale filtration. The particular permeability of the membrane pores is used to separate contamination. Notably, the membrane acts as wall that allows movement of the solvent, inorganic ions, tiny molecules, etc., via a membrane and holds macromolecules and particles (Figure 10a). The MOF membrane can be further categorized to enhance the efficiency of filtration like UF, MF, NF, and RO.169

Figure 10.

(a) Performance of MOF membranes in filtering: membrane filtration theory. Reprinted with permission from ref (169). Copyright 2020 Elsevier. (b) Progesterone for MF adsorption at various starting concentrations. Reprinted with permission from ref (171). Copyright 2016 Elsevier. (c) Performance of the produced membranes for dye rejection. Reprinted with permission from ref (175). Copyright 2017 Elsevier. (d) Flux vs time for TFN and M-TFN2 NF membranes following KHI rejection. Reprinted with permission from ref (178). Copyright 2018 Elsevier. (e) Salt rejection of TFC RO membranes. Reprinted with permission from ref (182). Copyright 2017 Elsevier. (f) FO performance of membranes. Reprinted with permission from ref (183). Copyright 2019 Elsevier.

5.4.1.1. Microfiltration

Macromolecules, suspended particles, and colloids are purified, concentrated, or separated from solution using this pressure-driven separation technique.170 Microfiltration (MF) retains particles between 0.1 and 1 μm. The MOF composite MF membrane is widely used due to the membrane’s properties being enhanced by MOFs. Ragab and co-workers redesigned a ZIF-8-based PTFE double-layer MF membrane to get a ZIF-8/PTFE membrane for removal of micropollutants (progesterone) from wastewater.171 The outcome was that the adsorption capacity was enhanced about 40% and there was double water permeability (Figure 10b). This was due to the hydrophobic nature of ZIF-8, which minimizes the friction between the membrane surface and water; hence, there is an increase in the permeability and also the formation of a hydrogen bond between the MOFs and water to enhance the hydrophilicity, thereby increasing the permeability.

5.4.1.2. Ultrafiltration

In this membrane, filtration forces such as the concentration or pressure gradients lead to separation via a semipermeable membrane. Suspended particles and solutes with a high molecular weight were trapped, while water and solutes with a low molecular weight pass through the membrane.172 It has small pore size ranging from 0.001 to 0.1 mm and requires a high driving force for filtration. Ultrafiltration (UF) membranes have been widely applied and studied in industry due to the magnificent performance in eliminating suspended nanoparticles, macromolecules, bacteria, etc.173 Nowadays, MOFs are mixed with various materials like silica, graphene oxide, titania, etc., instead of existing materials to switch the compatible properties before compounding with polymeric ultrafiltration membranes. Attention can be moved to the eco-friendly MOF–base composite membrane with high permeability and stability with antifouling characteristics, making it even more eco-friendly in manufacture application.174 UiO-66 was functionalized by graphene oxide to fabricate UiO-66@GO; then, a UIO-66@GO/PES composite membrane was synthesized by PES.175 The outcome indicated that 3.0 wt % of UiO-66 upgraded the rejection rate, flux, hydrophilicity, and antifouling property, as shown in Figure 10c. The CA/MOF@GO MOFs composite membrane was prepared using cellulose acetate (CA) as the base membrane, while MOF@GO was used as a filler.176 The benefits of MOF@GO fillers mixed with hydrophilic GO and MOFs porous structures enhance the preferable membrane properties. The results exhibited the highest water flux of 183.51 L/m2 h of CA/MOF@GO and better antifouling performance. Ultrafiltration is one of the most frequently methods for water decontamination and is also used in reverse osmosis pretreatment.

5.4.1.3. Nanofiltration

Nanofiltration (NF) is a low pressure-driven membrane method which lies among UF and RO as far as its capacity to reject ionic or molecular species. The nanofilter may have a larger free space, small pores, or nanovoids available for transport.177 NF permits inorganic salts and solvent to go through the membrane to reach the separation. Due to its efficacy in environmental applications, the NF method is extensively used in water treatment. Golpour and co-workers prepared PA-MOF/PPSU-GO, a novel MOF membrane for nanofiltration for treatment of wastewater containing KHI.178 The outcome was that the as-prepared MOF composite membrane enhanced by 50% the hydrophilicity and antifouling properties of permeation flux, which is greater than the original polymeric membrane, and rejection persisted similarly at more than 96% (Figure 10d). Yuan et al. synthesized a novel ZIF-300 membrane to remove heavy metal ions from wastewater.179 This ZIF-300 membrane has a stable and high water permeability of 39.2 L/m2 h bar with a 99.21% rejection rate. Therefore, pure ZIF-300 membranes will be used for wastewater heavy metal ion nanofiltration.

5.4.1.4. Reverse Osmosis and Forward Osmosis

Reverse osmosis (RO) happens when a solution is pressed against a solvent-selective membrane and the applied pressure is greater than the difference in the osmotic pressure across the membrane.180 It is a preferable membrane-based method for water desalination. Conversely, forward osmosis (FO) happens when the osmotic pressure gradient is positive between the feed and the draw solution and the solution is at a similar hydrostatic pressure.169 Liu and co-workers produced a pure-phase Zr–MOF (UiO-66) polycrystalline membrane on an alumina hollow fiber for desalination via a one-step solvothermal synthesis.181 To assess the desalination efficacy of the membranes as feeds, five different aqueous brine solutions with 0.20 wt % concentrations of NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, CaCl2, and AlCl3 were used. The results showed that the membranes had exceptional multivalent ion repulsion for Mg2+ (98.0%), Ca2+ (86.3%), and Al3+ (99.3%) as well as fine permeability. Furthermore, Hee and co-workers synthesized a RO MOF composite membrane by combining a PSF membrane with HKUST-1[Cu3(BCT2)] MOF.182 The results showed a 33% increase in water flux and a small increase in salt rejection to 96% (Figure 10e). Recently, CuBDC-NS, a 2D MOF nanomaterial, was discovered as a filler in PA to design a suitable TFN membrane.183 The results showed a 50% increase in water flux through the TFN membrane and a 50% reduction in specific reverse solute flux using 1.0 M NaCl for AL-FS mode (Figure 10f). A novel area of interest in MOF repurposing of RO and FO membranes is the control of the MOF size to alter the performance of the membrane and increase the filter efficiency.

5.4.2. Membrane Distillation

Membrane distillation (MD) is an effective separation technique that can reduce water energy stress in an environmentally friendly manner. To drive desalination, separate nonvolatile pollutants, or extract other components, MD requires low-grade thermal energy. In MD, an aqueous solution’s vapor travels through a hydrophobic membrane and then condenses on the other side of the membrane to produce a high-quality distillate.184 The driving force behind the separation is the vapor pressure on the two sides of hydrophobic porous membrane.169 DCMD, AGMD, SGMD, and VMD are four forms of MD currently available.185,186 Thermostability, hydrophobicity, improved thermal conductivity on the feed side, and low mass transfer resistance are all characteristics of MD membranes.187 In order to create new MOF composite membranes for desalination, Zuo and co-workers discovered an alumina-based MOF membrane.188 Because of the MOF functionalization, hydrophobicity was increased. Fan and co-workers developed a superhydrophobic poly(vinylidene fluoride) nanofiber-based membrane with 5 wt % of MOF-loaded nanofiber for desalination.189 The outcome showed that the water contact angle increased to 138.06 ± 2.18°, the water vapor flux increased, and the was a 99.99% NaCl rejection rate (Figure 11). MD is utilized in the food industry and heavy metal removal in addition to desalination. The use of a photothermally enhanced material for membrane distillation could increase the energy efficiency of MD. The chemical stability, hydrophobicity, and thermal characteristics of the membrane could be improved with the addition of a MOF.

Figure 11.

PVDF and PV-1 flux and permeate conductivity in DCMD. Reprinted with permission from ref (189). Copyright 2018 American Chemical Society.

5.4.3. Membrane Pervaporation

Pervaporation (PV) uses a membrane-selective barrier between the feed liquid phase and the permeate vapor phase in order to separate the two phases. It enables the vaporization of the desired component(s) of the liquid supply to pass through it. On the basis of a difference in how quickly each component moves across the membrane, components can be separated.190 This is due to the fact that the driving force for the vapor pressure in PV is different from that for membrane distillation. Also, PV is less energy consuming and more energy effective than MD because of the feed solution and permeate vapor. Typically, the best permeate flux and separation factor are provided by the PV membrane. Organic solvents in water are primarily removed and recycled using a PV membrane. As the PV membrane can be either organophilic or hydrophilic depending on the application, it is also employed for recovery of organic solvents.191 A superhydrophobic MAF-6 into PDMS was reported to design MMM for the recovery of ethanol.192 MAF-6’s hydrophilicity and high porosity increased the membrane’s permeability, selectivity, and stability. When MAF-6 was loaded to MMM, the hydrophobicity reached 15 wt %. According to experimental findings, the MMM membrane shows remarkable hydrophobicity when MAF-6 loading was 15 wt %, resulting in the highest flow of 1200 g/m2 h and a separation factor of 14.9. For the purpose of developing an MMM for the recovery of 1-butanol, they also discovered a ZIF-8 particle that was reconstructed through silanization into PDMS.193 The results revealed that these particles increased the 1-butanol flow 85% and had a 34% separation factor (Figure 12a). Since recovering organic solvents is the main use of pervaporation, the stability, selectivity, hydrophobicity, and permeability of the PV membrane are crucial. Moreover, MOF-based MMM was also used for water decontamination. Worood and co-workers prepared a MMM that contained UiO-66-NH2 MOFs as the adsorbent and CA as the polymeric matrix to prepare MOF@CA MMM for the removal of water contamination.194 First, they prepared UiO-66-NH2 by using ZrCl2 as a metal salt and 2-aminoterephthalic acid as an organic linker. Then, freshly prepared UiO-66-NH2 crystals were added to the cellulose acetate solution via stirring for 3 h. The solution was transferred into a glass Petri dish and dried overnight at room temperature. The synthesized MOF@CA MMM showed excellent performance in the removal of organic dye (methyl orange and methylene blue) and dichromate ions in comparison to the control polymer cellulose acetate membrane (Figure 12b). Hence, MOF-based membranes proved the approachability of the MOF nanocage immobilized within the MMM. The effective application of such a strategy to develop novel membrane materials for wastewater treatment applications should be based on the optimum hybridization of the chosen polymer matrix and the MOF filler to address the required conditions in a given context.

Figure 12.

(a) Comparison of pure PDMS membrane and MMMs combined with unmodified and modified ZIF-8 particles in 1.5 wt % 1-butanol at 55 °C for PV. Reprinted with permission from ref (193). Copyright 2019 Elsevier. (b) Comparison between the capacity of control CA and the MOF@CA toward methylene blue cationic dye, methyl orange anionic dye, and dichromate ions. Reprinted with permission from ref (194). Copyright 2020 American Chemical Society.

Other applications include catalytic application, which have been extensively employed for various transformations such as Friedel–Crafts reactions,195,196 condensation reactions,197,198 oxidations,199,200 coupling reactions,201,202 carbon dioxide fixation,203 cyano silylation,204,205 etc. More could be learned about the potential uses of MOFs in sustainable green catalysis, including biocatalysis, solvent-free catalysis, designing catalysts for reactions in environmentally friendly solvents, and enhancing the recyclability of catalysts. The application of sensing has recently drawn some study interest. For sensing purposes, carbon nanoparticles and metal oxide nanocomposites are utilized.

6. Conclusion and Future Perspectives

This report has covered the classification, nomenclature, synthesis methods, influencing factors, potential applications, as well as the biomedical applications of the metal–organic framework. It has explained how MOFs can be classified and synthesized with interesting characterization. Although the conventional hydro/solvothermal synthesis method was adequately used in MOF synthesis, unconventional and new methods like electrochemical, mechanochemical, sonochemical, microwave-assisted, etc., methods are just materializing in this extent.206 These are crystalline porous materials in which the metal is fixed in place to fabricate a porous and rigid geometry and uses various bridging ligands.61 Alternative methods lead to the MOFs having various properties. Potential applications of MOFs have also been discussed within the energy industry, such as next-generation rechargeable batteries and novel supercapacitors. Due to their well-regulated morphology with a flexible structure, a relatively high surface area, accessible metal sites, and a huge pore volume, MOFs and their composites are interesting and potential electrode materials for energy storage devices. However, the stability of the MOF materials in air is one of the drawbacks of energy storage devices which restricts good electrochemical performance. Doping heteroatoms or introducing metal oxides will further enhance the electrochemical performance of the MOFs. In addition, it has been highlighted how the superior compatibility and incredibly adaptable pore structure of MOF membranes have led to its employment in a variety of applications (including wastewater treatment and water regeneration). The water stability of the MOF membrane limits this application in terms of how to maintain the long-term stability of the membrane in alkaline and acidic media, complexation of MOFs with organic solvents, temperature variations, and commercialization of MOFs in eco-friendly ways. Hence, there is a need to develop water-stable MOF membranes with a facile method. MOFs are widely applied in biomedical applications, specifically in drug delivery systems. Nevertheless, the solubility and toxicity of the chosen metal salts and organic linkers for synthesized MOFs as well as the problems with biocompatibility are key issues for drug delivery applications. Also, pore encapsulation and surface adsorption are also the main factors for strong interaction which limits the application. Thus, it is necessary to design MOF–drug conjugates with improved biostability, biocompatibility, and therapeutic efficiency. In addition, the pressure, temperature and composition play chief roles in the H2 adsorption in MOFs. The adsorption capacity of H2 has been observed to be very low at ambient temperature and pressure to date. Thus, improving the adsoption capacity of MOFs at high pressure with a stable structure is still a challenge. As there is a large amount of flexibility in tailoring the structural framework and functionalization, it is likely that MOFs will assume a substantially more significant role in the future to achieve an elevated level of application

Research in the field of MOFs is expanding quickly in both academia and industry. MOFs are a potential new type of material that has incredible adaptability and the ability to address a number of 21st century global concerns. Most of the effort in the future will be devoted to developing novel materials through green synthesis, conducting related fundamental research to increase the structural variety of MOFs, and using those materials in a variety of potential applications. Metal–organic frameworks (nano-MOFs) at the nanoscale have garnered a lot of attention recently due to the discovery of numerous features like structural diversity, high surface area, and tailorability. In addition, nano-MOFs offer some special benefits like rapid adsorption/desorption kinetics, physiological stability, and access to the interior active parts.207 Moreover, nano-MOFs have been extensively studied in biomedicine due to their small sizes and remarkable biocompatibility. A number of functional nano-MOFs have been developed for therapeutic activities, such as porphyrin and its derivative-based nano-MOFs which are competitive in various biomedical therapies.208,209 Hence, the development of nano-MOF treatments with high biological safety would be the focus of a futuristic approach to the synthesis of nano-MOFs, which is absolutely necessary. In addition, these materials offer excellent adaptability/compatibility with other components, which considerably helps the integration of their individual advantages and enhances the performance of the resulting composites with regard to membrane separation, energy, and catalysis. We assume there will be more logical and large-scale methods of the controlled synthesis of nanosized MOFs, which will help to serve for improved performance, with the continuous efforts of scientists and the development of the nano-MOFs field. We anticipate hearing about a lot of fascinating nano-MOF-related results in the near future.

Acknowledgments

Authors thank the Director, Sardar Vallabhbhai National Institute of Technology, Surat for providing necessary facilities for this work.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- 2D

two dimensional

- 3D

three dimensional

- 5-FU

5-fluorouracil

- AGMD

air gap membrane distillation

- AlCl3

aluminum chloride

- AL-FS

active layer-oriented feed solution

- APIs

active pharmaceutical ingredients

- AS2O3

arsenic trioxide

- BDC