Abstract

The underrepresentation of women in research is well-documented, in everything from participation and leadership to peer review and publication. Even so, in the first months of the COVID-19 pandemic, early reports indicated a precipitous decline in women's scholarly productivity (both in time devoted to research and in journal publications) compared to pre-pandemic times. None of these studies, mainly from the Global North, could provide detailed explanations for the scale of this decline in research outcomes. Using a mixed methods research design, we offer the first comprehensive study to shed light on the complex reasons for the decline in research during the pandemic-enforced lockdown among 2,029 women academics drawn from 26 public universities in South Africa. Our study finds that a dramatic increase in teaching and administrative workloads, and the traditional family roles assumed by women while “working from home,” were among the key factors behind the reported decline in research activity among female academics in public universities. In short, teaching and administration effectively displaced research and publication—with serious implications for an already elusive gender equality in research. Finally, the paper offers recommendations that leaders and policy makers can draw on to support women academics and families in higher education during and beyond pandemic times.

Keywords: Female academics, Gender in academia, Careers, Childcare, COVID-19, Gender gap

1. Introduction

It is well-documented that there is a gender gap within scientific research and publication (Beaudry and Larivière, 2016; Coe et al., 2019; Huang et al., 2020; Helmer et al., 2017; Holman et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2020; Lerback and Hanson, 2017; Lerchenmueller and Sorenson, 2018; Mason et al., 2013; Mills, 2014) and that the reasons for such inequality are systemic and institutionalized (Coe et al., 2019; Lundine et al., 2019). Studies within the life sciences and STEM fields further demonstrate a gender disparity in these fields (Beaudry and Larivière, 2016; Graddy-Reed et al., 2019; Lerchenmueller and Sorenson, 2018); this gap exists in South Africa as elsewhere (Beaudry et al., 2018; Coe et al., 2019). Emerging evidence suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated this inequality (Amano-Patino et al., 2020; Fazackerley, 2020; Myers et al., 2020; Viglione, 2020), as well as disrupted the research enterprise globally (Adams-Prassl et al., n.d.; Collins et al., 2020; Myers et al., 2020; Nash and Churchill, 2020). However, to date there has been no systematic research that provides a detailed account of, and explanations for, the decline in research activity and outcomes for women academics, particularly outside of the Global North. We believe it is important that the South African experience be represented in the literature, since studies from the United States, Europe (Adams-Prassl et al., n.d.; Amano-Patino et al., 2020; Myers et al., 2020), and Australia (Nash and Churchill, 2020) have dominated published research inside relatively well-resourced institutions.

For this study, we conducted a large-scale survey of all female academic staff across South Africa's 26 public universities during the period of the government-enforced lockdown, which began on 26 March 2020 (“Coronavirus: President Ramaphosa announces a 21-day lockdown,” n.d., “COVID-19 South African resource portal,” n.d.), and during which all non-essential businesses, schools, and public universities were closed, and academics were constrained to work from their homes. While the direct health implications of the lockdown have been profound, the disintegration of economic, work, and school structures and the closure of childcare facilities have altered the ways in which academics work. The COVID-19 pandemic and the response to it by female academic staff will affect the higher education sector and scientific establishment for years to come, exacerbating the preexisting dominance of males within scientific and medical fields. This study seeks to elucidate how working female academics are managing the tasks of work while negotiating childcare, homeschooling, cooking, cleaning, and other duties.

This study was completed over the period of the various stages of the lockdown, from the initial hard lockdown (“stage 5″) in March through August 2020 (under “stage 2″, since 18 August). During this period, the population of women academics in South Africa ranged between 24,332 and 25,857 people, depending on resignations, secondments, and recruitment of personnel. As of September 1st, a total of 2029 full responses were received from women at different career stages. Thus, an average of 8.3% of the women academics in the national higher education system responded to the survey. The largest numbers of responses per institution were from the University of South Africa (UNISA), with 287 responses; the University of Pretoria (UP), with 185; Stellenbosch University (SU), with 172; and the University of Cape Town (UCT), the continent's top university (“World University Rankings”, 2020), with 111. To protect privacy, respondents are not identifiable beyond their institution, and no response will be attributed to any particular university in this paper. The career stages of respondents were evenly spread, with the largest group of respondents (29.8%) in the 0–5 years range of academic appointment.

Although the South African higher education landscape has often been categorized by type of institution (e.g., by language of instruction or historical racial orientation) in order to shed light onto the spectrum of differentiation across universities, this study did not concern itself with the type of institution, but rather examined the sector as a whole; therefore, survey participants were not limited by nationality, race, rank, or terms of appointment. The survey questionnaire consisted of 12 Likert-scale questions, followed by an open-ended section that allowed for detailed, unlimited responses by the participants; this section provided a substantial volume of qualitative data, which were coded by theme and then analyzed. Ethical clearance was granted by the host institution (Stellenbosch University), followed by gatekeeper clearance from the other 25 universities; in one case, the research team was simply given permission by the university to contact its female academic staff directly, whereas in most cases each institution distributed the survey to their female academic staff, providing an introductory cover letter with an electronic link to the survey instrument. This study expands the understanding of how the pandemic is affecting scholarly output, as well as the career trajectory of women in university-based research. Since the South African sample is drawn from a diverse range of historically white and black universities with markedly different research capacities and outputs, it offers unique insights into the academic impacts of COVID-19 in a developing country context with a focus on women academics representing the full range of scholarly disciplines.

2. Results

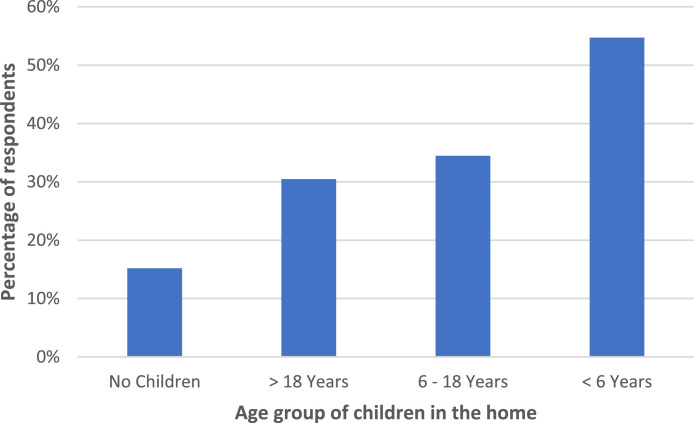

The single most important variable impacting the academic work of female academics appears to be having younger or multiple dependents in the home. Overall, the pandemic appears to have most affected academic work among women with children, with 54% of respondents having children living at home. Further analyses of the data suggests that those who found academic work extremely difficult were those with children under 6 years of age (see Fig. 1 ), as well as those who had children at school. It is evident from the qualitative data that the age and educational stage of children were significant factors in the decline in productivity among female academics. The demands of caring for toddlers, as well as schools’ expectations of homeschooling, took a toll on respondents. Academic mothers were caught up in the demands of competing roles, such as teaching online, nurturing vulnerable students, comforting anxious children, taking care of toddlers, and finding time to do research and writing. Doing academic work was extremely difficult for most.

Fig. 1.

Share of women who found academic work “extremely difficult” by ages of children in the home

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 564 of 2029.

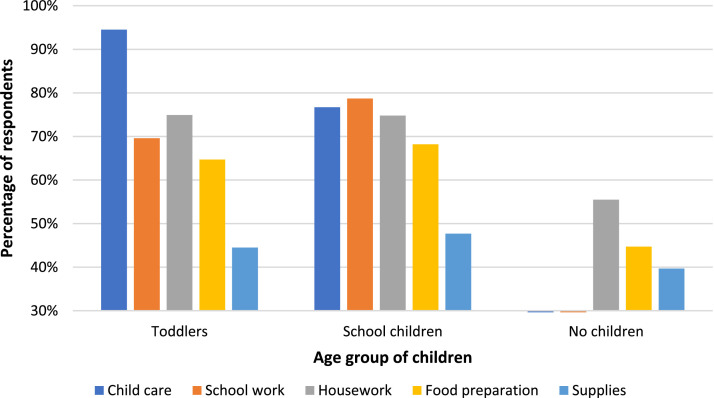

The two at-home responsibilities that had the highest impacts on women's academic work during lockdown were childcare (in the case of toddlers) and assisting with schoolwork (in the case of school-age children). While the pandemic seems to have affected women academics in various ways, when respondents were asked which responsibilities (food preparation, housework, etc.) impacted their academic work, it was clear that schoolwork and childcare were the dominant factors. Overall, 42.7% of respondents with children said that schoolwork had a very high impact, and 43.8% said childcare did. While housework and food preparation are significant factors, when the high- and very-high scores were examined closely, childcare was found to account for 74.6% of the responses, with schoolwork at 68.8%, housework at 66.8%, food preparation at 58.9%, and getting supplies at 44.8%. The contrast is starker when one analyses the subset of respondents who had toddlers: 94.5% of respondents with toddlers (children <6) indicated that childcare had a high to very high impact on academic work. Those with toddlers found that other responsibilities also affected their work significantly. On the other hand, respondents with no children felt the impact of other responsibilities to be much lower, as can be seen in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

Share of women who found that responsibilities had a high/very high impact on academic work by children's age

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. A total of 382 women had toddlers (< 6 years old), 798 had school children (between 6 and 18 years old), and 941 had no children. The sum of these respondents does not equal 2029, as some respondents had both toddlers and school children.

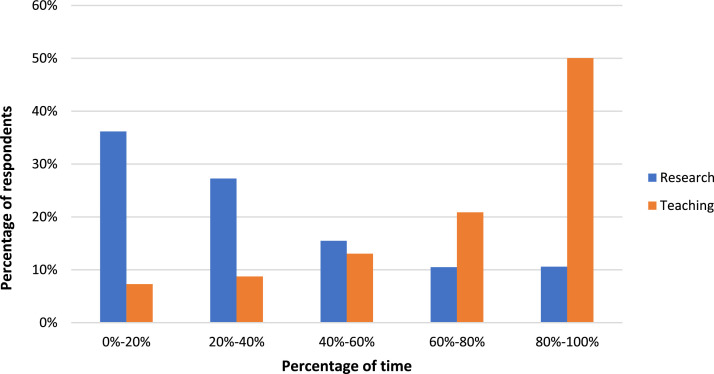

A key finding of the survey is that the sharp increase in the demands on teaching time during lockdown has effectively displaced the available research time among female academics. Academics perform many different roles, including teaching, research, grant-proposal writing, administrative duties, and other tasks, depending on their rank and discipline. In this survey, the data demonstrate that the distribution of teaching and research was not at all even. Fig. 3 demonstrates that academic time was mostly taken up by teaching online, rather than research. In the qualitative section of the survey, participants lamented the effort required to adjust to the new mode of teaching online. Just over half of the respondents (50.10%) indicated that they spent more than 80% of their total work time teaching online.

Fig. 3.

Share of women by percentage of time spent on research and teaching related activities

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of valid responses = 1878.

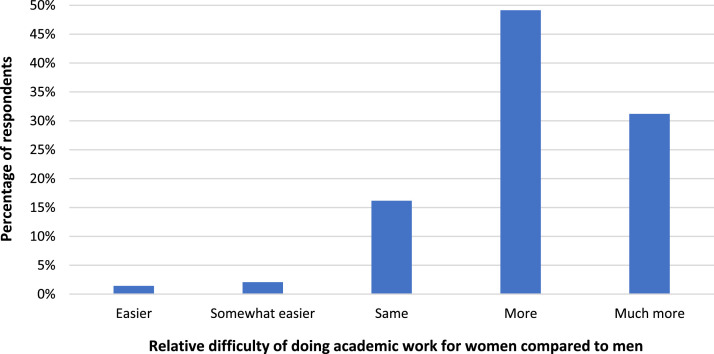

The overwhelming majority of women (80.3%) believe that it has been “more” to “much more” difficult for women than for men to do academic work during the lockdown period (see Fig. 4 ). The qualitative analyses suggest that the pandemic has affected researchers differently according to their disciplines. Those in the “bench sciences,” such as chemistry, biological sciences, and biochemistry, were explicit in stating that the closure of laboratories or facilities affected their research productivity. Disciplines that are less lab- and equipment-intensive were also affected; however, these cases were often related to individual circumstances, such as the ability to do fieldwork in particular social science fields.

Fig. 4.

Share of respondents by perceived relative difficulty of doing academic work for women compared to men

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

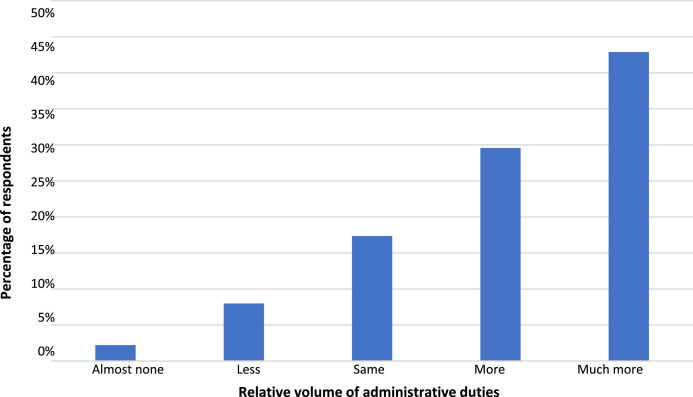

Fig. 5 shows that a large majority of women academics (72.5%) reported an increase (more/much more) in their administrative workloads during lockdown, with direct implications for available teaching and research time. Only 10.2% of respondents reported that the amount of such work was less (easier/somewhat easier) than before the pandemic lockdown, and 17.3% reported that it remained the same. This result may appear counterintuitive at first, as one might expect that the pause in various activities under lockdown would imply a lighter administrative burden. Our qualitative analysis sheds light on the factors related to this observed increase in administrative tasks. In particular, respondents reported an increase in (i) meetings; (ii) email correspondence; (iii) time devoted to transitioning courses and assessments online; and (iv) time spent cancelling some projects, pivoting others, and reporting requirements on COVID itself. These insights into the escalation of administrative workloads experienced by women are especially important for progress within the scientific enterprise.

Fig. 5.

Share of respondents by volume of administrative duties during the lockdown

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

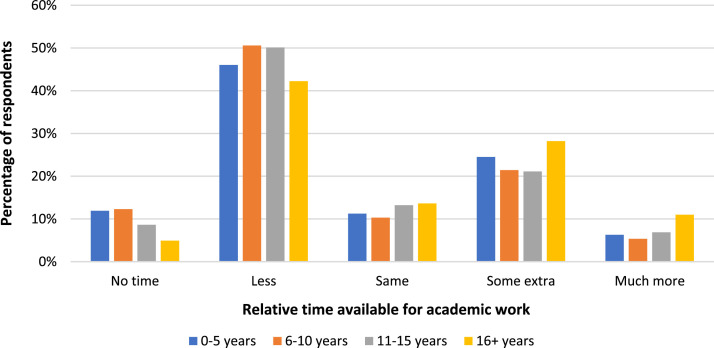

Most women (75.1%) indicated that doing their academic work (teaching and research) was “somewhat” to “extremely” difficult during the lockdown, while 16.6% reported that it was relatively easier. In further analyses of participants who indicated that work was relatively easier, it became evident that these perceptions were correlated to the following factors: having children and the children's ages; career stages; commuting conditions; and working arrangements prior to lockdown. Moreover, more than half of the women in this study (56.5%) reported having “less time” or “no time” available for academic work, while 31.4% indicated they had more time (some extra/much more) for their academic workload. It is noteworthy that the survey did not find any marked differences between the time available for academic work and the career stage (years of academic incumbency) of respondents, with more experienced academics having only a slight advantage in their available time (see Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Share of respondents grouped by career stages and amount of time available to do academic work

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

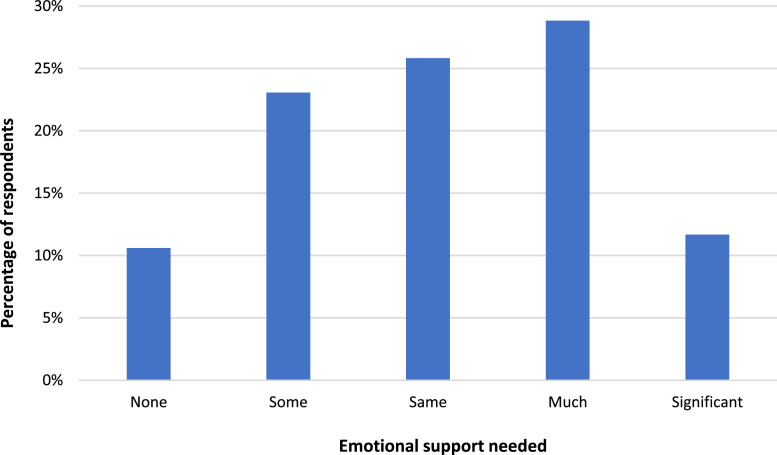

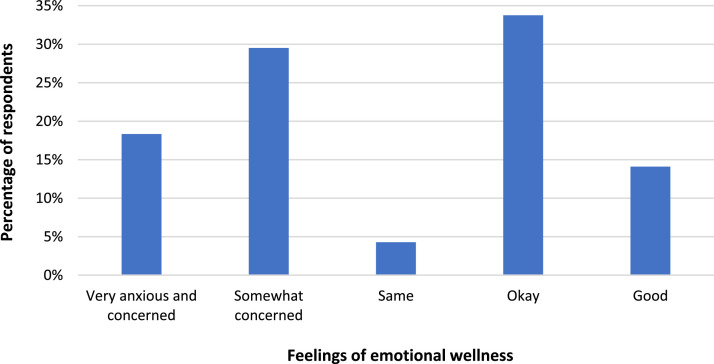

Overall, a total of 40.5% of participants indicated they required much more or significantly more emotional support as working academics to cope with the demands of the job, while 25.8% indicated they required the same amount of support as before (see Fig. 7 ). Several respondents expressed feelings of unending exhaustion, which reduced their ability to focus and to be productive. The feeling of despair and a sense of the unfairness of workload distribution was a key theme emerging from the data. As shown in Fig. 8 , about 48% of participants indicated that they felt “very anxious and concerned” or “somewhat concerned” in continuing with their academic work, given their personal concerns about the pandemic, while (perhaps surprisingly) an exactly equal number felt OK or good. Further analyses of the data make clear that it is the individual circumstances of the female academic that often explain the emotional toll of the enforced lockdown. Themes such as childcare and eldercare added additional and heightened stress levels. These findings are consistent with a recent study of 59 higher education institutions in the UK, which showed evidence of an escalation in poor mental health among university staff (Liz, 2019).

Fig. 7.

Share of respondents by amount of emotional support needed during the lockdown

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

Fig. 8.

Share of respondents by feelings of emotional wellness experienced during the lockdown

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

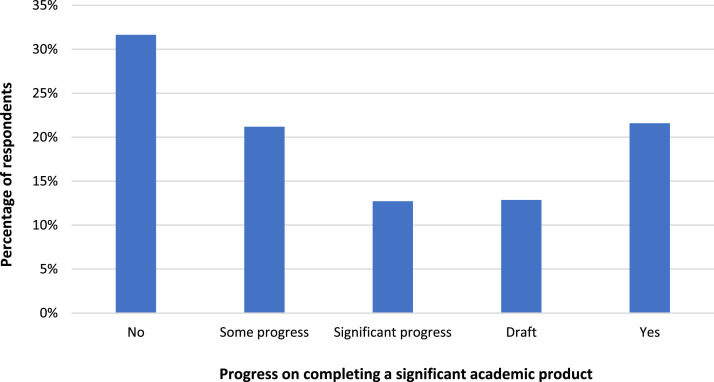

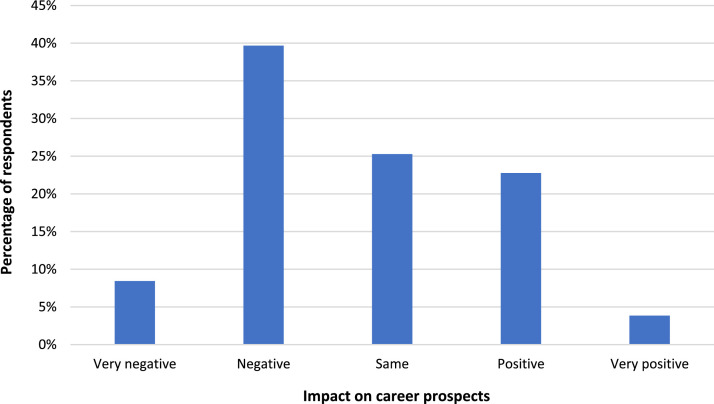

The key finding of the study is that the lockdown has had a profound effect on women's academic productivity, with 31.6% reporting having made “no progress” and 21.2% having made only “some progress” towards completing a significant academic product. This will likely affect the prospects of female academics for promotion and advancement. Institutions may need to track these effects and provide support through policies to protect and nurture the sustainability of women's careers in academia. Indeed, many women in the study (48.1%) indicated that the lockdown would impact negatively on their academic career prospects. Leaders in academic institutions need to be aware that female academic staff view the lockdown as yet another barrier to equity, and to consider the effects of the pandemic on career challenges in recruitment and promotion decisions (Fig. 9, Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 9.

Share of respondents by progress on completing a significant academic product during the lockdown

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

Fig. 10.

Share of respondents by perceived impact of the lockdown on their career prospects

Notes: Authors’ calculations from survey data. Total number of respondents = 2029.

As mentioned above, the questionnaire asked whether the respondents felt emotionally well enough to do their academic work, given their concerns about the pandemic. To further analyze the correlates of women's emotional wellness, we estimated a simple logit model, defining the composite variable Stress as being equal to 1 when a respondent reported being either “very anxious and concerned” or “somewhat concerned” emotionally.

Table 1 reports the estimated coefficients from a logit model of various factors explaining women's emotional stress. The results show that women who reported experiencing heightened difficulty doing their academic work from home during the lockdown were almost 20% more likely to report being emotionally unwell. In addition, women who experienced an increase in their administrative duties during the pandemic were 7% more likely to report being stressed. Positive and significant coefficients are also found on variables describing some of the principal factors impairing academic work. Women who considered doing housework and helping children with schoolwork as highly distracting were about 8% more likely to report stress. A smaller but also significant association is found between stress and having to procure groceries/supplies for the household. Other significant predictors of women's emotional wellbeing were having more time during lockdown to do academic work (8 percent negative association with stress) and dedicating additional time to research (where a 10% increase in research time is associated with a 1% increase in the likelihood of being stressed).

Table 1.

What explains women's stress?

| VARIABLES | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Academic work difficult | 0.196*** |

| (0.0285) | |

| Admin duties increase | 0.073*** |

| (0.0265) | |

| Time during lockdown | −0.0819*** |

| (0.0255) | |

| Research time | 0.00108** |

| (0.000416) | |

| Academic stage: 0–5 years | 0.0469 |

| (0.0306) | |

| Academic stage: 6–10 years | 0.0127 |

| (0.0338) | |

| Academic stage: 11–15 years | −0.0216 |

| (0.0338) | |

| No help at home | −0.0224 |

| (0.0225) | |

| Children | −0.0529 |

| (0.0354) | |

| Childcare | −0.004 |

| (0.0345) | |

| Housework | 0.0787*** |

| (0.027) | |

| Food preparation | 0.0261 |

| (0.0269) | |

| School work | 0.0775** |

| (0.0334) | |

| Grocery/supplies | 0.0474** |

| (0.0235) | |

| Observations | 1878 |

Logit model for binary variable: Stress. Standard errors in parentheses.

Reference category for academic stage: 16+ years.

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

Table 2 presents the estimates from an ordered logit model of various factors explaining academic productivity. Here, the dependent variable is the response to a question on the respondent's progress towards a significant “academic product” during the lockdown period; the answer could range from no progress at all to full completion, for a total of five categories. Unsurprisingly, women who experienced heightened difficulty in doing their academic work from home during the lockdown were significantly less likely to report being able to make progress on an academic product. The opposite is true for women who reported having had more time during the lockdown to do work; they were significantly more likely to have made progress. Time dedicated to research also has a positive and significant association with making progress on academic work. In addition, table 2 shows that more junior academics were less likely to make progress relative to their more senior colleagues. Finally, women who did not have any help at home also appear to have been penalized in terms of their academic productivity.

Table 2.

What explains women's academic productivity?

| VARIABLES | Acad_prod |

|---|---|

| Academic work difficult | −0.456*** |

| (0.110) | |

| Admin duties increase | −0.0438 |

| (0.101) | |

| Time during lockdown | 0.790*** |

| (0.0976) | |

| Research time | 0.0241*** |

| (0.00168) | |

| Academic stage: 0–5 years | −0.296** |

| (0.116) | |

| Academic stage: 6–10 years | −0.225* |

| (0.123) | |

| Academic stage: 11–15 years | −0.0399 |

| (0.129) | |

| No help at home | −0.166* |

| (0.0865) | |

| Children | −0.120 |

| (0.134) | |

| Childcare | −0.0817 |

| (0.133) | |

| Housework | −0.155 |

| (0.105) | |

| Food preparation | −0.0478 |

| (0.105) | |

| School work | 0.151 |

| (0.133) | |

| Grocery/supplies | −0.0992 |

| (0.0913) | |

| Observations | 1878 |

Ordered logit model of ordinal variable: academic productivity.

Standard errors in parentheses. Reference category for academic stage: 16+ years.

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1.

It should be stressed that the results from Tables 1 and 2 only reveal correlations, not causation. The logit models, however, show several statistically significant associations. These results provide further descriptive evidence of the challenges faced by female academics during the pandemic-enforced lockdown in South Africa.

3. Findings from the qualitative data

In the open-ended section of the survey, encoded words and phrases were analyzed using Atlas.ti software. A conventional content analysis was performed, in which codes were extracted from the text data. This form of analysis best suited the study, as it did not bind the researchers to a particular theory or confine them to the counting and comparison of keywords. Instead, the approach was illustrative of a commitment towards understanding the individual and subjective viewpoints of women academics (Flick, 2015). Several powerful themes emerged from the analysis; one particularly strong theme was that of “guilt.”

Collins et al. (2020) illustrates emphatically how policy affects the experience of “maternal guilt.” Similarly, many of our respondents struggled to balance employment, motherhood, domestic tasks, and caregiving. The following quotation sums up the overwhelming emotions of the respondents:

The lockdown magnified my experiences pre-lockdown as it relates to being a female academic … where most have used this opportunity to reconnect with their children, I have been overwhelmed by feelings of guilt, depression, and anxiety at not being able to juggle everything.

A large part of academic guilt described by the respondents related to academic mothers who are caught up in the demands of competing roles, such as teaching online, nurturing vulnerable students, comforting anxious children, taking care of toddlers, and trying to jumpstart research and writing. Several studies have emerged from the community of woman academics reporting patterns of struggle with the increased pressures of balancing parenthood and professional demands (Boncori, 2020; Gourlay, 2020; Guy and Arthur, 2020). The closure of public schools and the loss of formal childcare services during the pandemic is a major reason for the increased pressure on working mothers. Further, the dynamics of using technology and working online are adding to the stresses. For woman academics who are mothers, the threat to emotional wellbeing extends into the home.

While the intensity of childcare has been noted in the quantitative data, the open-ended survey indicated that there was an immediate impact on the home as an organized space to accommodate not only the individual woman academic's work, but also on how that contained environment had to be reorganized in relation to others, i.e., children, spouses, partners, parents, and, sometimes, extended family. The participants in this study reported struggling with how best to manage an externally enforced work “flexibility”: clearly, flexible arrangements bring their own challenges, and they are not suitable for everyone. The data indicates that the concepts of home and working from home were fundamentally unsettled by the pandemic-enforced lockdown. The enduring concept of home as a place of refuge from the outside world was replaced with a new and still-unsettled notion of home as a congested, competitive, and constrained place for women's academic work.

4. Discussion

Although the respondents in this study are based in South Africa, it is evident from this and prior research that the pandemic has had an effect on the academic enterprise globally. Indeed, circumstances will continue to evolve as the stages of lockdown change, and the full impacts of the pandemic on the scientific enterprise remain to be seen. Concerning the division between time spent teaching versus time spent on research, it is noteworthy that a recent report indicates that, across the African continent, teaching (including supervision of graduate students) takes up an average of 67.9% of academics’ time, while research amounts to 32.1% (Beaudry et al., 2018). There is a recurring complaint within the academy that the hours required for teaching are overwhelming, and that research is expected to be done in one's spare time. This seems to be a major constraint.

Respondents gave expression to the harsh reality of advancement in South African universities, as well as to the almost exclusive emphasis that is placed on “research outputs,” even if promotion policy documents pay lip service to the importance of teaching and service in the formal metrics. Even for those aiming for advancement at the senior levels, the prospects are still slim, given the massive increase in workloads during the pandemic lockdown, such as the time-consuming conversion of face-to-face lectures into online learning resources and the demands of caring for small children and managing a household. Anecdotal evidence indicates that there has been increased research productivity during the pandemic across some disciplines, but fewer submissions and publications by female academics (Amano-Patino et al., 2020; Viglione, 2020). It is important to note that the bibliometric data used for these studies cannot capture the career dynamics of teaching, which has had a profound impact on our respondents during the lockdown. Thus, in addressing and improving career prospects of female academics, institutions may need a durable and sustainable approach in alleviating the teaching load.

The collapsing of the academic workspace is a new phenomenon. Before the lockdown, some women academics worked from home because it was a comfortable workspace or because it allowed for some form of refuge. Now the situation is different, and this reorganization of space was unanticipated by many. In a recent article shared widely across academia, the social demographer Alessandra Minello (2020) aptly describes the additional social and emotional labor required by women in the academy and how those requirements can block academic advancement:

Academic work—in which career advancement is based on the number and quality of a person's scientific publications, and their ability to obtain funding for research projects—is basically incompatible with tending to children … [while] [t]hose with fewer care duties are aiming for the stars.

The data in our study correlate with Minello's observations and suggest that there will be consequences in advancement and promotion for South African female academic staff after the enforced lockdown. The findings in this research speak to the precarity of women's academic work as they experience and articulate a sense of instability, and even perilousness, in terms of their academic futures.

A major theme that emerges is how women academics’ role as nurturers comes to play a critical part in the intersecting functions of caring for both their students and their families through the period of the pandemic-enforced lockdown. What this study demonstrates is exactly how the emotional, psychological, and educational needs of students draw academic women into extensive nurturing roles, beyond caring for their families, that impact negatively on academic work. It also shows the workings of the symbiotic relationship of giving care (by women academics) and requiring care (by students) in a pandemic. Furthermore, the lockdown has put particular strain on female academics employed on soft funding, as well as those who are in academic appointments conditioned upon the continuation of postgraduate studies.

A key factor in maintaining and enhancing the quality of the higher education sector is the quality of the faculty members. We call on institutional leaders, science councils, academic societies, and funding bodies to implement policies to mitigate the career risks that female academics encountered during the enforced lockdown. Importantly, it is not only the introduction of new policies but also the attitudes towards those policies that needs attention. Given the challenge of the unequal effects of the pandemic on female academics, there is a critical need for not only universities but also scientific and medical councils to present a united voice for the support of women academics. Achieving gender equality within the academic enterprise requires a wide set of tools to be utilized and policies to be implemented. It requires institutional commitment, as well as knowledge and competency in effecting organizational change.

5. Potential policies and practices

In this section of our paper, we wish to suggest several voluntary policies and practices that could work towards change in achieving gender equality within the academic enterprise. These recommendations are not intended to be an exhaustive list, but rather some of the tools that might provide solutions to the effects of the pandemic on women academics. There is no doubt that institutional leaders and policy makers have a major role to play in shifting the norms, and they must respond to mitigate the impact of the pandemic on woman academics.

Acknowledge the problem in university-wide communication. Acknowledgement is an important driver for organizational change and is essential in driving appropriate behaviors in various contexts. It is critical that leadership and policy makers increase awareness of the impossible choices women academics have faced and are facing during the pandemic. Management expectations should be moderated, from the top down, in ways that recognize the exceptional circumstances imposed by the pandemic lockdown. In addition to acknowledging the problem, it is important that communications be clear, consistent, and empathetic throughout and beyond the lockdown crisis.

Adjust timelines for the appointment and advancement of women academics, e.g., probation, promotion, and contract renewals. In academia, productivity represents an important determinant in promotion and recruitment. Productivity, particularly in the sciences, means publications. Overall, our study suggests that productivity has declined, and this research makes clear that the pandemic has had a detrimental effect on the productivity of women. Thus, the already well-known “productivity paradox” (Lerchenmueller and Sorenson, 2018) has been exacerbated by the enforced lockdown. Providing for research assistantships to support women academics who are active in research and adjusting application and advancement forms to allow for explanations of lapses in productivity are mechanisms that could address and remove barriers for women academics.

A significant number of responses in the open-ended section of the survey expressed feelings of exhaustion and the sense of a reduction in the ability to focus due to childcare and eldercare issues. The lack of provision for childcare appears to be approaching crisis level. Leaders should invest in childcare support (e.g., in the form of salary supplements) for academic women working from home, as well as provide on-campus childcare facilities for women staff. The economist Betsy Stevenson (2020) recently noted of pregnant women and working mothers whose children are too young to manage on their own that “we could have an entire generation of women who are hurt … they may spend a significant amount of time out of the work force, or their careers could just peter out in terms of promotions.” Reflection by leaders of all genders in higher education is required to create a workplace that could prioritize women with children. Also required is a commitment to ongoing institutional research into the problem, so that relevant data can inform senior management deliberations on a regular basis.

Legislative approaches to addressing social inequities have been employed in South Africa since the fall of Apartheid. These type of social policy experiences in the Global South might provide insights into the efficacy of, for example, using quotas to bring about change. However, despite legislative prescriptions, in South Africa at this time even the limited gains made in the past decades are at risk of being rolled back, including the incomplete transition of women into truly equal roles in the labor market. Ultimately, what matters more than legislation and policy is the culture surrounding them. Leadership will need the capacity to alleviate anxiety and fear and to project messages of compassion and care. Over the long term, forced structural and cultural changes that could benefit women—a better child care system; more flexible work arrangements; an even deeper appreciation of the sometimes overwhelming demands of childcare and eldercare—could go a long way towards resolving the unequal effects of the enforced pandemic lockdown.

6. Conclusion

The pandemic poses a lasting threat to gender equality in academia. One of the earliest studies in the wake of COVID-19 pointed to the pandemic's “substantial impact on research worldwide, which we do not capture” (Myers et al., 2020). This study offers the first comprehensive account of the pandemic's impact in an African country, which not only confirms what we knew from existing research but extends our understanding of the effects of lockdown on women's academic work.

In summary, this study gives evidence that the single most important factor that negatively impacts on women's academic work during the pandemic lockdown is the presence of younger children in the home; that the escalating demands of remote teaching and administration effectively displaced time for research, writing and publication; and that most women perceive that doing academic work from home has been “more” to “much more” difficult than for men. What we now know from this study is that the burden of inequality during the pandemic lockdown has immediate consequences for women's emotional health and wellness, and longer-term implications for their academic career prospects, given the sharp decline in their research productivity in the COVID-19 period.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.respol.2021.104403.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- Amano-Patino, N., Faraglia, E., Giannitsarou, C., Hasna, Z., 2020. Who is doing new research in the time of COVID-19? Not the female economists [WWW Document]. URL https://voxeu.org/article/who-doing-new-research-time-covid-19-not-female-economists (accessed 9.19.20).

- Beaudry C., Larivière V. Which gender gap? Factors affecting researchers’ scientific impact in science and medicine. Res. Policy. 2016;45:1790–1817. [Google Scholar]

- Beaudry, C., Mouton, J., Prozesky, H., 2018. The next generation of scientists in Africa.

- Boncori I. The never-ending shift: a feminist reflection on living and organizing academic lives during the coronavirus pandemic. Gender Work Organ. 2020;27:677–682. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coe I.R., Wiley R., Bekker .L..-G. Organisational best practices towards gender equality in science and medicine. Lancet. 2019;393:587–593. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)33188-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins C., Landivar L.C., Ruppanner L., Scarborough W.J. COVID-19 and the gender gap in work hours. Gender, Work Organ. 2020 doi: 10.1111/gwao.12506. n/a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazackerley A. Women's research plummets over lockdown-but articles from men increase. Guard. 2020 May 12. [Google Scholar]

- Flick U. 2nd ed. Sage Publications; London: 2015. Introducing Research methodology: a Beginner's Guide to Doing a Research Project. [Google Scholar]

- Gourlay L. Quarantined, sequestered, closed: theorising academic bodies under Coronavirus lockdown. Postdigitakl Sci. Educ. 2020;2:791–811. [Google Scholar]

- Graddy-Reed A., Lanahan L., Eyer J. Gender discrepancies in publication productivity of high-performing life science graduate students. Res. Policy. 2019;48 [Google Scholar]

- Guy B., Arthur B. Academic motherhood during Covid-19. Navigating our dual roles as educators and mothers. Gender Work Organ. 2020;27:887–899. doi: 10.1111/gwao.12493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmer M., Schottdorf M., Neef A., Battaglia D. Gender bias in scholarly peer review. Elife. 2017;6:e21718. doi: 10.7554/eLife.21718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holman L., Stuart-Fox D., Hauser C.E. The gender gap in science: how long until women are equally represented? PLoS Biol. 2018;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.2004956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J., Gates A.J., Sinatra R., Barabási A.-.L. Historical comparison of gender inequality in scientific careers across countries and disciplines. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2020;117:4609–4616. doi: 10.1073/PNAS.1914221117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerback J., Hanson B. Journals invite too few women to referee. Nature. 2017;541:455–457. doi: 10.1038/541455a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerchenmueller M.J., Sorenson O. The gender gap in early career transitions in the life sciences. Res. Policy. 2018;47:1007–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Liz, M., 2019. Pressure vessels: the epidemic of poor mental health among higher education staff.

- Lundine J., Bourgeault I.L., Clark J., Heidari S., Balabanova D. Gender bias in academia. Lancet. 2019;393:741–743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30281-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mason M.A., Wolfinger N.H., Goulden M. Rutgers University Press; 2013. Do babies matter?: Gender and Family in the Ivory Tower. [Google Scholar]

- Mills M.J. 2015th ed. Springer International Publishing AG; Cham: 2014. Gender and the Work-Family experience: an Intersection of Two Domains. Cham. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minello A. The pandemic and the female academic. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01135-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers K.R., Tham W.Y., Yin Y., Cohodes N., Thursby J.G., Thursby M.C., Schiffer P., Walsh J.T., Lakhani K.R., Wang D. Unequal effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on scientists. Nat. Hum. Behav. 2020:1–4. doi: 10.1038/s41562-020-0921-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nash M., Churchill B. Gender, Work Organ; 2020. Caring During COVID-19: A gendered Analysis of Australian university Responses to Managing Remote Working and Caring Responsibilities. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, B. 2020. How the child care crisis will distort the economy for a generation.

- Viglione G. Are women publishing less during the pandemic? Here's what the data say. Nature. 2020;581:365–366. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World University Rankings 2020 | Times Higher Education (THE) [WWW Document], 2020. URL https://www.timeshighereducation.com/world-university-rankings/2020/world-ranking#!/page/0/length/25/sort_by/rank/sort_order/asc/cols/stats.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.