Abstract

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) increased US unemployment benefits by $600 a week. Theory predicts that FPUC should decrease job applications, while the effect on vacancy creation is ambiguous. We estimate the effect of FPUC on job applications and vacancy creation week by week, from March to July 2020, using granular data from the online jobs platform Glassdoor. We exploit variation in the proportional increase in benefits across local labor markets. To isolate the effect of FPUC, we flexibly allow for different trends in local labor markets differentially exposed to the COVID-19 crisis. We verify that trends in outcomes prior to the FPUC do not correlate with future increases in benefits, which supports our identification assumption. First, we find that a 10% increase in unemployment benefits caused a 3.6% decline in applications, but did not decrease vacancy creation; hence, FPUC increased labor market tightness (vacancies/applications). Second, we document that tightness was unusually depressed during the FPUC period. Altogether, our results imply that the positive effect of FPUC on tightness was likely welfare improving: FPUC decreased competition among applicants at a time when jobs were unusually scarce. Our results also help explain prior findings that FPUC did not decrease employment.

Keywords: Unemployment insurance, Job vacancies, Job applications, COVID-19

1. Introduction

In March 2020, the coronavirus COVID-19 led to a dramatic surge in business closures and job losses. To address this crisis, the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC) was voted on March 27 as part of the CARES Act. FPUC provided unemployed workers with an additional $600 a week in unemployment benefits, until the end of July 2020. This represented an unprecedented increase in unemployment insurance generosity: 76% of unemployed workers had a replacement rate above 100%, i.e. collected higher unemployment benefits than their prior wage (Ganong et al., 2020). Economic theory predicts that more generous benefits decrease job search effort and could decrease vacancy creation (Landais et al., 2018b). Therefore, FPUC might have increased unemployment and dampened economic activity, in particular during the summer of 2020, when many lockdown measures were lifted. Yet, the early evidence suggests that FPUC had at most limited effects on employment (Bartik et al., 2020, Altonji et al., 2020, Dube, 2020). Why? We show that the FPUC did indeed have a negative effect on search effort. However, we provide two pieces of evidence that can explain why FPUC did not decrease employment. First, FPUC did not decrease vacancy creation—not even during the re-opening phase in June-July 2020. Second, labor market tightness was unusually low in March-July 2020: since jobs were already receiving an unusually high number of applications, a decrease in applications likely had limited effects on the number of workers hired.

Identifying the effect of FPUC on local labor markets is challenging. One can exploit the large disparities in the proportional increase in unemployment benefits: for workers who were eligible to lower regular weekly benefits levels before the CARES Act, the additional $600 per week represents a larger relative increase. However, the passage of the FPUC coincided with exceptionally large and brutal changes in the labor market: just before the implementation of FPUC, the number of job listings collapsed (Forsythe et al., 2020a), while the number of unemployed workers skyrocketed. What is more, low-wage workers were most likely to lose their jobs, and these workers are precisely the ones who experienced the largest increase in benefits with the FPUC. Our empirical analysis aims at addressing these potential confounding factors, exploiting very granular data on labor market outcomes.

We collect detailed data on job applications and job postings from Glassdoor.com, for January 2018 to July 2020. We measure search effort and vacancy creation by counting the number of applications and new job vacancy postings each week, in each local labor market —defined as the interaction of state, occupations and industries and wage deciles. We compute potential replacement rates using the calculator in Ganong et al. (2020). To strengthen the external validity of our analysis, we re-weigh observations such that each Stateindustryoccupation reflects the proportion of the US labor force in that labor market in the Current Population Survey (CPS) for 2018–2020.

In the first part of the paper, we estimate the impact of FPUC on search effort, job vacancies and labor market tightness in March-July 2020. We exploit differences in proportional increases in benefits across local labor markets. We include several control variables to flexibly account for changes in the local labor market that were unrelated to the FPUC. We allow for market-specific seasonal variation, using week-of-year by local labor market fixed effects. We include state by week fixed effects to control for differential COVID-19 related policies across states, and other factors that change at the state level. We control for industry by week fixed effects, which accounts for the differential impact of the crisis by industry. Additionally, we allow for different trends in local labor markets that were differentially exposed to unemployment during the COVID-19 crisis prior to the CARES Act. Our identifying assumption is that, in the absence of policy change, the outcome variables would have evolved similarly in local labor markets with different increases in UI, conditional on controls. To support the credibility of our identification assumption, we show that future increases in FPUC do not correlate with trends in job applications, job vacancies or labor market tightness in the weeks prior to the enactment of the FPUC. We also confirm in robustness checks that our main results hold in the construction sector, where job loss before FPUC was not systematically correlated with earnings (and thus the increase in the replacement rate), and hence identification might be less challenging.

We find that a 10% increase in the benefit replacement rate due to the FPUC leads to a 3.6% decline in job applications. At the same time, FPUC had no effect on job vacancies. The absence of an effect on vacancy creation indicates that employers’ recruiting was not limited by workers’ lower search effort or potentially higher wage demands, but rather by other factors, consistent with job rationing models (Michaillat, 2012). Taking the effect on applications and vacancies together, a 10% increase in the benefit replacement rate increased labor market tightness by 3.3%. We then analyze the timing of the effect. One could have expected to see a larger impact of FPUC during the reopening phase when most lockdowns were lifted (June-July 2020) and economic activity was picking up. However, FPUC still had no effect on vacancy creation. Further, the effect of FPUC on job applications decreased from May until the end of FPUC in July 2020, suggesting that job seekers might have increased their search effort in anticipation of FPUC expiration.

Our results are similar when we exclude periods of lockdown, or when we focus on teleworkable occupations, which are less affected by social distancing measures. In markets where workers are more likely to be on temporary layoffs, the effects of FPUC on search effort are significantly smaller. This is consistent with the idea that workers are less likely to search when they expect to be recalled, and suggests that the prevalence of temporary layoffs during the COVID-19 crisis might have attenuated the effect of unemployment insurance on job search.

In the second part of the paper, we describe the context in which FPUC was implemented, as it is crucial to assess the impact of FPUC on unemployment and welfare. We document the evolution of seasonally adjusted applications, vacancies, and labor market tightness, relative to their levels in January-February 2020. The number of applications increased by 4.4% during the FPUC period, despite the negative effect of FPUC on search effort. This probably reflected in part the drastic increase in the number of unemployed workers. At the same time, job vacancies declined by 26%. As a result, labor market tightness decreased by 31%. This implies that, on average, employers got more applicants for their vacancies. Even in the markets most affected by FPUC (4th quartile of the increase in replacement rate due to FPUC), tightness during the FPUC period of March-July 2020 was 19% lower than in January-February 2020. During the re-opening period (June-July 2020), tightness was back to its pre-pandemic level, even though many unemployed workers were receiving FPUC.

We finally discuss how our results contribute to understanding the welfare impact of the FPUC. Landais et al. (2018b) formalize that increases in unemployment insurance improve welfare when unemployment insurance increases tightness and tightness is inefficiently low. We demonstrate that this is likely the case for FPUC. First, we show that FPUC did not affect vacancy creation, and hence increased tightness by decreasing applications. Second, we document that labor market tightness was particularly low during the FPUC period of March-July 2020 relative to January-February 2020: this suggests that tightness in the absence of FPUC may have been inefficiently low. Importantly, these results hold for the reopening phase (June-July 2020). Taken together, our results hence indicate that the effect of FPUC on labor market tightness was likely welfare improving, during the whole period of FPUC. Our paper focuses on welfare considerations that are related to labor market tightness. For a comprehensive welfare analysis of FPUC, one should also consider the gains associated with consumption smoothing for UI recipients and the costs associated with their longer unemployment spell. Moreover, beyond the framework of Landais et al. (2018b), the FPUC was potentially also valuable to society by keeping some workers outside of the labor force and limiting the transmission of the virus (Fang et al., 2020), and by boosting consumption and employment through a stimulus effect (Ganong et al., 2021). These additional welfare considerations would likely reinforce our conclusion regarding the desirability of high unemployment insurance in March-July 2020.

Our article contributes to the literature on the impact of unemployment benefit levels on job search, and vacancy creation. The increase in the level of benefits with FPUC was exceptionally large (Schmieder and von Wachter, 2016). Yet, our findings are consistent with the estimated effect of unemployment insurance on search effort in prior literature (Krueger and Mueller, 2010, Fradkin and Baker, 2017, Lichter and Schiprowski, 2020). Although most models predict that more generous unemployment insurance should decrease search, one important question in general equilibrium models is how unemployment benefits affect vacancy creation, and hence labor market tightness (Landais et al., 2018b). In standard models, higher unemployment benefits diminish job search and exert upward pressure on wages by raising the outside option of unemployed workers, thereby discouraging vacancy creation (Pissarides, 2000). In “job rationing” models, vacancy creation primarily depends on the marginal product of labor, and is hence unaffected by unemployment insurance (Michaillat, 2012). Our finding that FPUC did not affect vacancy creation is consistent with job rationing. What is the economic intuition? In the context of the COVID-19 crisis, social distancing measures may have decreased labor productivity. Other factors less specific to the COVID-19 crisis might have also contributed to job rationing, since we detect no effect on vacancy creation even after lockdown measures were lifted, and even for teleworkable occupations. Our evidence of job rationing is consistent with what was found in other contexts (Lalive et al., 2015, Marinescu, 2017, Landais et al., 2018a).

Second, we contribute to the body of work analyzing the effects the FPUC on employment. Several empirical studies found no association between FPUC and employment (Bartik et al., 2020, Altonji et al., 2020, Finamor and Scott, 2021, Dube, 2020). We provide a potential explanation for the limited effect of FPUC on employment: FPUC did not affect vacancy creation, and its large negative effect on search effort happened at a time when returns to search were low. This complements other explanations for the limited employment effect in the literature. In their models, Boar and Mongey, 2020, Petrosky-Nadeau, 2020, Mitman and Rabinovich, 2021 emphasize that the effect of FPUC on search behavior should be attenuated because unemployed workers anticipated its expiration. Although we find a substantial effect of FPUC on search effort, our finding that it decreased between May and July is consistent with the idea that workers reacted less when they anticipated the expiration. Ganong et al. (2021) show that the FPUC had a positive stimulus effect on employment through increased consumption, which could offset the negative effect on job search effort.

Last, our analysis contributes to the study of the labor market during COVID-19 (Bartik et al., 2020, Gupta et al., 2020, Cheng et al., 2020, Fairlie et al., 2020, Montenovo et al., 2020). We add to work investigating trends in the applications and job postings during COVID in Sweden (Hensvik et al., 2020), and job postings in the US (Forsythe et al., 2020a, Campello et al., 2020, Forsythe et al., 2020a, Forsythe et al., 2020b).

2. Data

We combine several datasets from Glassdoor, one of the world’s largest jobs and career sites. We use job vacancy listings and job applications from Glassdoor’s online jobs platform in January 2018 to July 2020 for the U.S. We also exploit information on users’ self-reported salaries to measure replacement rates.

2.1. Data on job listings and job applications

Glassdoor contains job openings that companies post directly to the site, or that are collected on company career sites or third-party job boards. Glassdoor then ties job listings data to specific industries and canonical occupations that can be mapped into O*NET-SOC codes. We focus on new job listings posted each week rather than the total stock of active job listings. The flow is more responsive to sharp changes in policy and labor market conditions, and captures a disproportionate share of application activity. To measure search effort, we take the count of applications, defined as a user starting an application by clicking on the “Apply Now” button.1 Applications provide a proxy of search effort, under the assumption that the probability of applying on Glassdoor’s website rather than using other search channels is relatively stable over time. We allocate applications into an industry and occupation category based on jobs characteristics, and into a state based on applicants’ address. Applications on Glassdoor don’t come exclusively from unemployment benefits recipients, therefore our estimates at the local labor market level also capture the search effort of job seekers who do not receive UI. This is the right measure for the purpose of investigating overall labor market tightness.2 Note that these market level estimates could be smaller than estimates of the microeconomic impact on the search of UI recipients, as job seekers who do not receive UI should react less to changes in unemployment insurance.

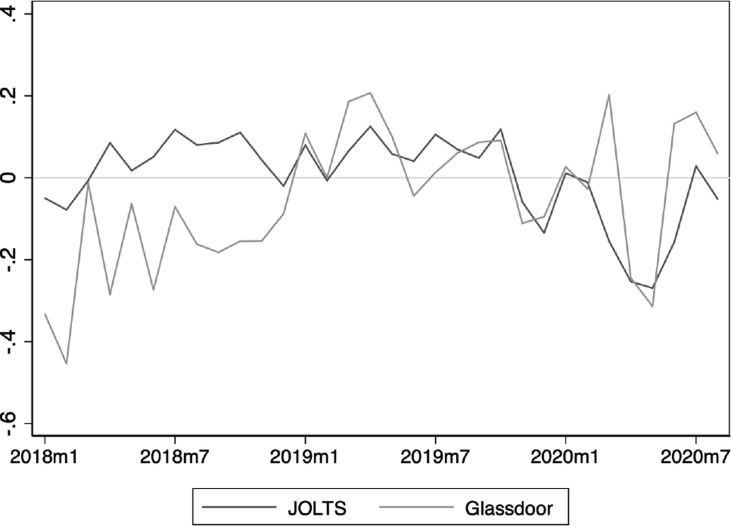

Glassdoor’s job listings capture a large portion of online U.S. job listings, which themselves comprise a substantial percentage of all job openings.3 Job listings at very small businesses or managed by unions may be underrepresented (Chamberlain and Zhao, 2019). As a result, compared to the Current Population Survey (CPS) labor force by industry in 2018–2020, some sectors like Construction are underrepresented, while other sectors like Information Technology are overrepresented (Table A.1). We hence use weights in all our analysis, based on the average number of workers in the labor force in the industry, occupation and state from the CPS for January 2018 - July 2020. We confirm that weighted job listings evolve very similarly — the correlation is 0.6 for 2019–2020 — to vacancies in the representative Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) (Fig. A.2). In particular, the magnitude of the decrease in job listings in April and May 2020 is the same in the two data sources.

Fig. A.2.

Comparison of the measure of new vacancies from JOLTS and Glassdoor. Notes: The Figure presents the variation in the count of new job listing at the monthly level, relative to the average level in January-February 2020. We compare the measure of new vacancies from JOLTS, to the measure from Glassdoor data—which we use in the rest of the paper. For the measure from Glassdoor, we present the weighted sum of job listings, using weights reflecting the size of each Stateindustryoccupation in the labor force in the CPS.

2.2. Data on earnings and unemployment benefits

We determine the level of prior earnings for all jobseekers in our sample, using information self-reported by Glassdoor users. Although it is not required to search for jobs on the platform, some Glassdoor users report information on their wage, including base salary and additional compensation like tips and cash bonuses.4 We take the average earnings for each state-occupation, using a very disaggregated occupation definition (O*Net 6-digit codes, 416 categories). Then, we determine the replacement rate that jobseekers eligible for unemployment insurance should receive, with and without the FPUC. We use the calculator created by Ganong et al. (2020), which gives unemployment benefits based on individuals’ state of residence and pre-displacement quarterly earnings, according to UI guidance provided by the Department of Labor: it allows us to compute replacement rates without FPUC, based on jobseekers’ state, imputed prior earnings, and assuming that they worked continuously during the four quarters preceding unemployment.5 Finally, we add $600 to standard weekly benefits to compute the replacement rate with the FPUC.

2.3. Panel at the week and local labor market level

We define a local labor market as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations (76 categories in our sample), 2-digit industries (12 categories in our sample) and wage deciles. We take a narrow definition to be able to capture a lot of the variation in replacement rates and add granular fixed effects to our regressions. We keep local labor markets with at least 1000 applications in 2018–2020, such that we can detect variation in weekly applications count (our results are robust to using alternative thresholds). We arrange our data as a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level: we track the count of applications, of vacancies, labor market tightness, and the average replacement rates, each week in each local labor market. We present descriptive statistics in Table A.2.

3. Institutional background and empirical strategy

3.1. Institutional background

The CARES Act was signed into law on March 27 2020. It enacted the Federal Pandemic Unemployment Compensation (FPUC), a $600 supplement to weekly unemployment benefits for all workers eligible for unemployment insurance.6 The $600 FPUC amount was chosen to raise the UI replacement rate to 100% for the average U.S. worker. Because of technical issues in state unemployment insurance systems, it was not possible to tailor FPUC to each worker’s prior earnings. Once the CARES Act was voted, unemployed workers could anticipate their upcoming replacement rate, and potentially adjust their behavior accordingly. But it took a few weeks, until the end of April, for all states to start paying out benefits (Bartik et al., 2020). The last FPUC payment was the week of July 20, 2020; after this, eligible workers could still receive the regular amount of unemployment benefits.

3.2. Empirical strategy

Variation in replacement rate increase For identification, we exploit differences in relative increases in replacement rate across local labor markets. It is easy to see that a fixed $600 increase in weekly benefits B generates a relative increase in replacement rate (or in benefits ) that is negatively correlated with pre-displacement earnings w:

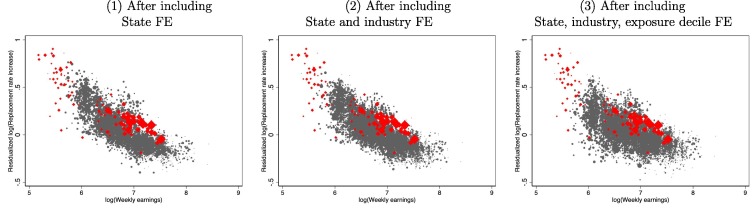

For each local labor market, we compute the logged ratio , representing the relative increase in replacement rate. There is substantial variation in this measure, and the measure is negatively correlated with earnings levels (Fig. A.3).

Fig. A.3.

Variation in the residualized increase in replacement rate in our data. Notes: This Figure illustrates the variation in the residualized increase in replacement rate in our data, which serves to identify the effect of FPUC. The Figure shows that increases in replacement rates are negatively correlated with pre-displacement weekly earnings, and that substantial variation in increase in replacement rate remains even once we take out the portion explained by state, industry, and exposure decile. They are obtained in the cross section of all the local labor market (state by occupation by industry by wage decile) in our study sample. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS, like in the rest of the analysis. As an example, we show in red the observations corresponding to local labor markets for the occupation “salesmen”.

Identification strategy: Our empirical strategy consists in analyzing the changes in logged labor market outcomes that are associated with this logged replacement rate ratio around the time when the FPUC was voted: in the absence of confounding factors, larger changes in local labor markets that experience a larger increase in replacement rate measure the effect of the FPUC.7 Note that our strategy is not designed to capture the indirect effects of FPUC going through consumption: such stimulus effects primarily affect jobs producing goods and services that see the largest increase in consumption, not necessarily jobs where workers experience the largest increase in replacement rates.

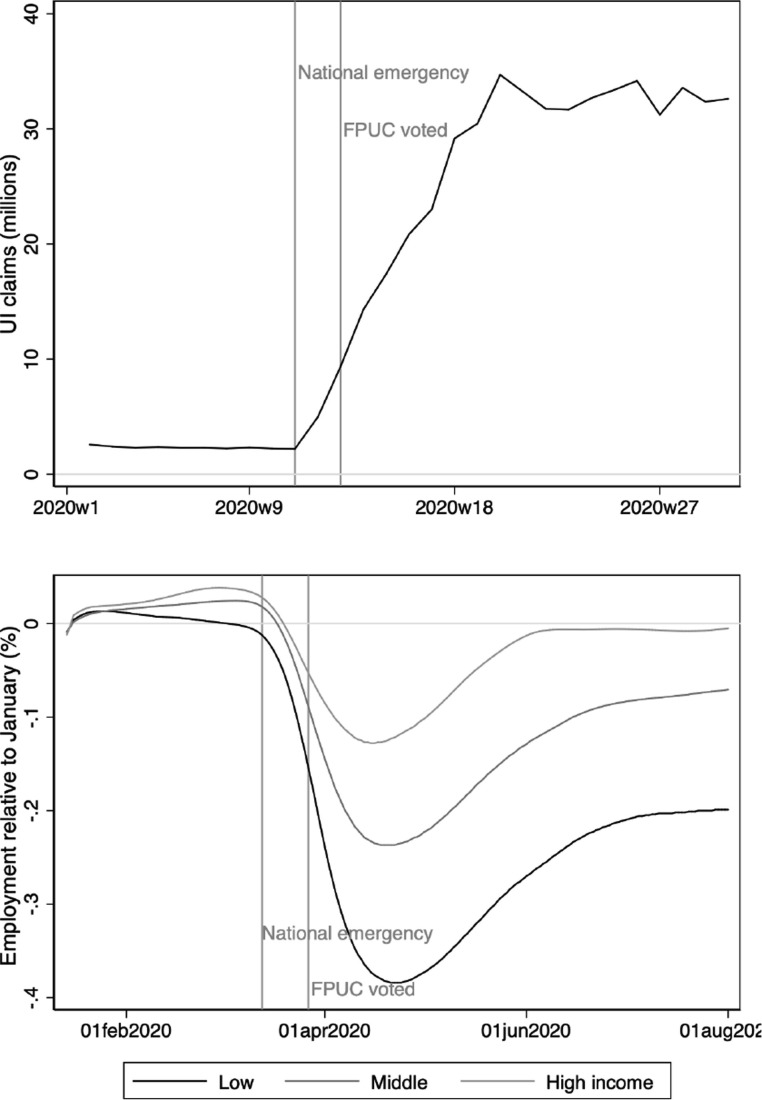

The identification of the effect of FPUC is threatened by any factor that affects the outcomes around the CARES Act and correlates with the increase in replacement rate. The enactment of FPUC coincided with an exceptionally large and abrupt negative labor market shock due to COVID-19 (Fig. A.1). This shock disproportionately hit low-paying jobs, and hence workers who could experience the largest increase in replacement rates with FPUC. Therefore, failing to account for this shock would likely bias estimates of the effect of FPUC. We address this challenge in several ways.

Fig. A.1.

Descriptive statistics on the state of the labor market when FPUC was voted. Notes: This Figure shows the evolution of the number of UI claims (new and continuing) in the upper panel. In the lower panel, it shows the evolution of employment rates among workers at different parts of the wage distribution (low wage, middle wage or high wage), relative to their levels in January 2020. The data for the lower panel are described in Chetty et al. (2020), and made publicly available on the website https://tracktherecovery.org.

First, we include for several controls to absorb the effect of the COVID-19 crisis, or other potential confounders. We include week-of-yearlocal labor market fixed effects, to flexibly allow for seasonal variation in each local labor market. As the COVID-19 crisis hit different states and industries in different ways, we include timestate fixed effects, and timeindustry fixed effects. We also directly quantify the exposure to the COVID-19 crisis in each local labor market: we estimate the risk of unemployment immediately prior to the CARES Act. Using the monthly CPS for January to March 2020 matched with the Outgoing Rotation Group 2019 (ORG) (Flood et al., 2020), we predict the probability of being unemployed for individuals in the labor force, in a logit model including industry, occupation, wage decile, and state fixed effects (see Table A.3). We use the estimated coefficients to predict the risk of unemployment in our sample, i.e the “exposure”. We allow for different trends in markets differentially exposed to the COVID-19 crisis in our estimation model, by including exposure decilecalendar week fixed effects.8 We identify the effect of FPUC on labor market outcomes under the assumption that, in the absence of a change in unemployment insurance, the outcome variables would have evolved similarly in local labor markets with different replacement rate increases, but in the same state, industry, and exposure category.9 If this condition is not satisfied, our estimates may also capture, for example, the differential response of low-wage local labor markets to the COVID-19 shock.

Second, we test the plausibility of our identifying assumption by analyzing the correlation between the evolution of outcomes before the CARES Act, and the magnitude of the benefits increase induced by FPUC. If our identification strategy is valid, our pre-CARES Act estimates should not be significant. This is equivalent to the test of the parallel trend assumption in a differences-in-differences setup.

Third, we conduct a robustness check where we focus on a segment of the economy where identification problems appear less severe. Specifically, we analyze the correlation of prior earnings with the probability of becoming unemployed at the onset of the COVID-19 crisis, by sector, using the CPS for January-March 2020, matched with ORG 2019. Consistent with descriptive statistics presented in Fig. A.1, there is a strong negative relationship between prior earnings and the risk of unemployment (Table A.4), but this correlation is small and insignificant in the Construction sector (in the Mining sector as well, but there are virtually no applications for this sector on Glassdoor). We hence re-estimate the effect of FPUC for Construction, using the same empirical model without including week by state, week by industry and week by exposure fixed effects.10 The estimates give the causal effect of FPUC, without imposing any functional form to the confounding effect of the COVID-19 crisis on outcomes, under the alternative identifying assumption that there is no substantial confounding factor in this sector.

One might want to analyze changes in labor market outcomes around the time of the expiration of the FPUC, rather than at the beginning, to have a more stable economic environment. However, identifying the effect of the FPUC around its expiration is difficult, as there should be no sharp change in outcomes then. Indeed, finite duration unemployment insurance should generate large changes in the search behavior of UI recipients at the start of the UI spell, but the effect should gradually decrease until exhaustion (van den Berg, 1990, Marinescu and Skandalis, 2021, DellaVigna et al., 2020). Moreover, if the impact of FPUC on jobseekers includes liquidity effects rather than only moral hazard effects (Chetty (2008)), it should persist after FPUC expiration, until savings are exhausted.

Estimation models: We estimate the following model:

| (1) |

gives the relative increase in the replacement rate associated with FPUC in each local labor market, defined as the intersection of a state s, an occupation o, an industry i and a wage decile w. denotes the logged outcome variable in calendar week t (to avoid missing values, we add 1 to each outcome before taking the log). indicates that the calendar week t is weeks before the start of FPUC (for ), or after (for ). We take as reference period , the week before the vote of FPUC (the FPUC was voted on the week of March 23, 2020). The are the coefficients of interest. We include week-of-yearlocal labor market fixed effect, ; we let time t fixed effects vary by state (), industry () and Exposure decile (). is the error term. We cluster standard errors at the state level, and observations are weighted by the average number of workers in the labor force in the industry, occupation and state from the CPS for January 2018- July 2020.

4. The impact of FPUC on the labor market

4.1. Main results

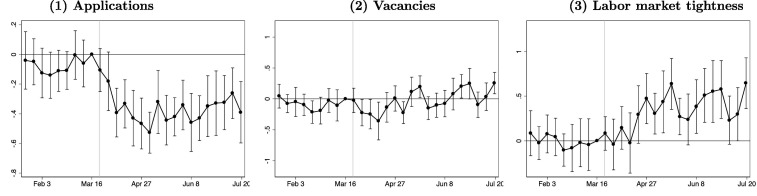

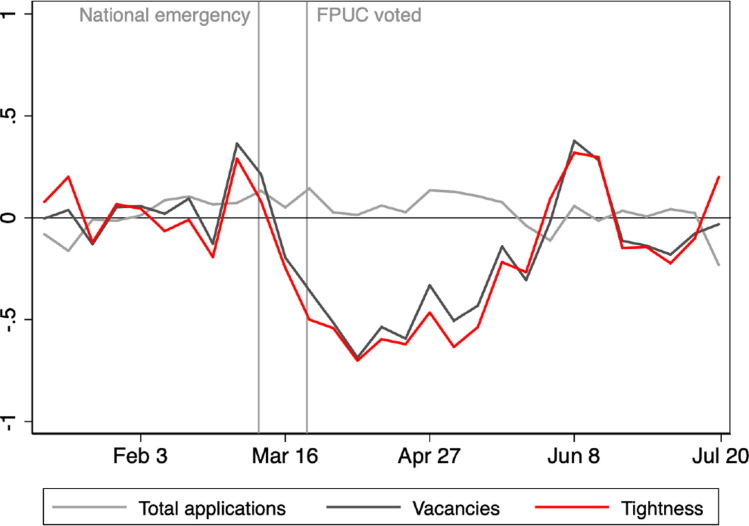

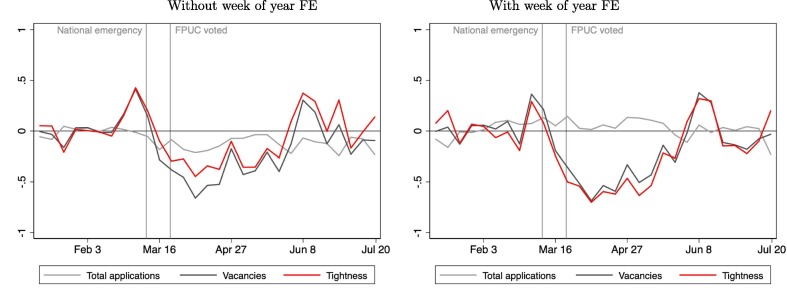

Pre-FPUC trends: Fig. 1 presents the correlation between labor market outcomes and the increase in UI generosity induced by FPUC, week by week. There is no significant correlation between applications and future benefits increases in weeks prior to the adoption of FPUC. This supports the credibility of our identifying assumption that, in the absence of FPUC, the evolution of outcomes would be similar in markets that experienced different benefits increases, conditional on the controls included. Under this assumption, the coefficients for the period after the adoption of FPUC can be interpreted as the causal effect of FPUC.

Fig. 1.

The impact of FPUC on applications, vacancies and tightness, week by week. Notes: This Figure reports the estimates from regressions of the logged count of applications, the logged count of vacancies, and the logged labor market tightness on the interaction of each week around the enactment of the FPUC and the potential increase in UI generosity . The coefficients before the enactment of the FPUC help test our identification assumption. The coefficients after represent the elasticity of the outcome with respect to benefits levels. We use a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level. We include week-of-yearlocal labor market, timestate, timeindustry and timeExposure deciles fixed effects. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Thin lines deNote 95% confidence intervals, based on robust SE clustered at the state level.

The effect of FPUC: The increase in unemployment insurance generosity leads to a decrease in applications immediately after the CARES Act, which remains visible until FPUC expires (Fig. 1, (1)). Quantitatively, Table 1 shows that the corresponding elasticity of applications with respect to the benefit replacement rate is −0.36 (col. (1)): a 10% increase in the replacement rate leads to a 3.6% decline in job applications, consistent with the theoretical prediction that a higher benefit replacement rate decreases search effort. In contrast, FPUC had no clear effect on job vacancies (Fig. 1, (2)). While there is a decrease in the number of vacancies immediately after FPUC was voted and until mid-April, it is only transitory and imprecisely estimated. Since FPUC decreased applications and had no effect on vacancies, it increased labor market tightness (Fig. 1, (3)). Consistently, we see in column (2) of Table 1 that the elasticity of vacancies with respect to the replacement rate is close to zero and statistically insignificant. Column (3) shows that the elasticity of tightness is therefore close to the opposite of the elasticity of applications: a 10% increase in the benefit replacement rate leads to a 3.34% increase in labor market tightness.

Table 1.

Elasticity of search with respect to benefits levels.

| Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| FPUC period | −0.361*** | −0.027 | 0.334*** |

| (0.071) | (0.069) | (0.106) | |

| Exposure decileTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IndustryTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| StateTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labor marketWeek of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimated elasticity of job applications, vacancy creation and labor market tightness with respect to unemployment benefits levels. The estimates are obtained from the regression of logged labor market outcomes on the logged increase in benefits interacted with a dummy for the period between the vote of FPUC and its expiration, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

4.2. Additional results

We first analyze the timing of the effect of FPUC on search effort. In Fig. 1 (panel (1)), we see that the negative effect on search strongly increased in the first 3 weeks, possibly due to delays in initial benefit receipt. The effect then remained roughly constant until June, and decreased until the end of FPUC. The estimated elasticity is −0.44 in May, at its largest; in July, as the extra benefits are about to expire, the elasticity is significantly smaller (in absolute value) at −0.33 (Table 2 , col. 1).11 Our results are consistent with theory predicting that job seekers increase their search effort as benefits expiration approaches (Marinescu and Skandalis, 2021), and therefore that temporary increases in benefits have smaller effects on job search when workers anticipate their expiration (Boar and Mongey, 2020, Petrosky-Nadeau, 2020, Mitman and Rabinovich, 2021).

Table 2.

Additional results on the impact of FPUC on applications.

| Applications (ln) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | |

| FPUC period, March | −0.144* | |||

| (0.079) | ||||

| FPUC period, April | −0.385*** | |||

| (0.075) | ||||

| FPUC period, May | −0.436*** | |||

| (0.065) | ||||

| FPUC period, June | −0.395*** | |||

| (0.080) | ||||

| FPUC period, July | −0.326*** | |||

| (0.085) | ||||

| FPUC periodLockdown | −0.356*** | |||

| (0.070) | ||||

| FPUC periodOpen | −0.368*** | |||

| (0.075) | ||||

| FPUC period, Telework | −0.382*** | |||

| (0.100) | ||||

| FPUC period, Not telework | −0.311*** | |||

| (0.086) | ||||

| FPUC period Telework | 0.131 | |||

| (0.141) | ||||

| FPUC period, High temp layoff | −0.173** | |||

| (0.080) | ||||

| FPUC period, Low temp layoff | −0.414*** | |||

| (0.075) | ||||

| FPUC period High temp layoff | −0.361*** | |||

| (0.107) | ||||

| P-Value Test May = July | .013 | |||

| P-Value Test Lockdown = Open | .702 | |||

| P-Value Test Telework = Not telework | .554 | |||

| P-Value Test High temp layoff = Low temp layoff | .009 | |||

| Exposure decileTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IndustryTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| StateTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labor marketWeek of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,496,988 | 1,523,252 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimates from the regression of logged search effort on various independent variables, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Over time, the economic environment also changed with many states adopting lockdown measures in March 2020 that were later relaxed. As these measures could hinder economic activity, one could expect the impact of unemployment insurance on the labor market to be attenuated during lockdowns. The elasticity of search with respect to unemployment insurance was slightly smaller when states implemented a lockdown, but the difference is small and insignificant (Table 2 col. (2)). This suggests that the difference in the effect of unemployment insurance on search over time is not explained by lockdown measures.

One could expect that the reaction of job seekers to the increase in unemployment insurance was smaller than in normal times, because the risk of contamination with COVID-19 imposed constraints on search and on work. Yet, we find little evidence for this: in Table 2 (col. 3), we show that the effect of FPUC on search effort is similar in “teleworkable” and non-“teleworkable” occupations (defined as in Dingel and Neiman (2020)).

The situation of unemployed workers during the COVID-19 crisis was also atypical in that a large fraction of them were on temporary layoff (Birinci et al., 2021). We estimate the chance to be on temporary layoff in the CPS for January to July 2020 conditional on being unemployed, in a logit model with two-digit occupation, two-digit industry, state and wage decile fixed effects. We predict the probability of temporary layoff among unemployed workers in each local labor market based on the estimated coefficients. In Table 2 (col. (4)), we show that the effect of FPUC on search effort is significantly smaller in markets with a high (above median) chance of temporary layoff (elasticity of −0.17) than in the others (elasticity of −0.41). This suggests that workers who expect to be recalled search less irrespective of their unemployment insurance. When estimating the FPUC effect by quartile of the probability of temporary layoff (Table A.6), we find the same overall pattern, and detect a negative effect of FPUC on vacancies in labor markets with the lowest prevalence of temporary layoffs. This suggests that the prevalence of temporary layoffs has contributed to attenuating the effect of FPUC on job search and vacancy creation.

4.3. Robustness checks

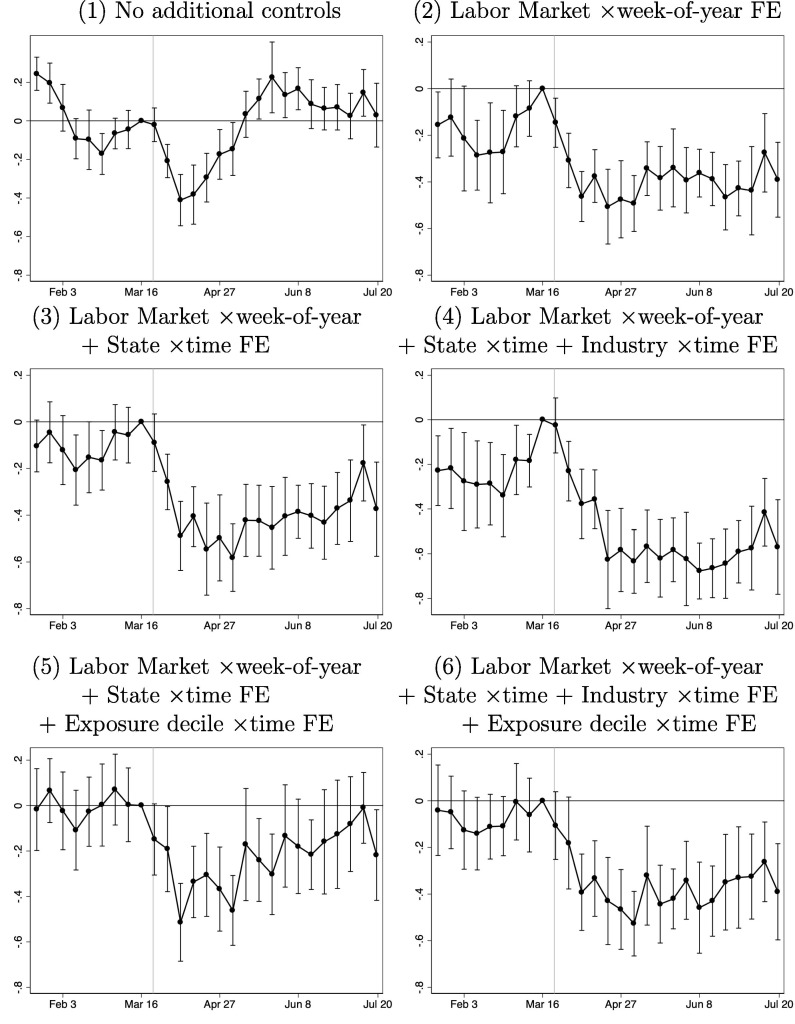

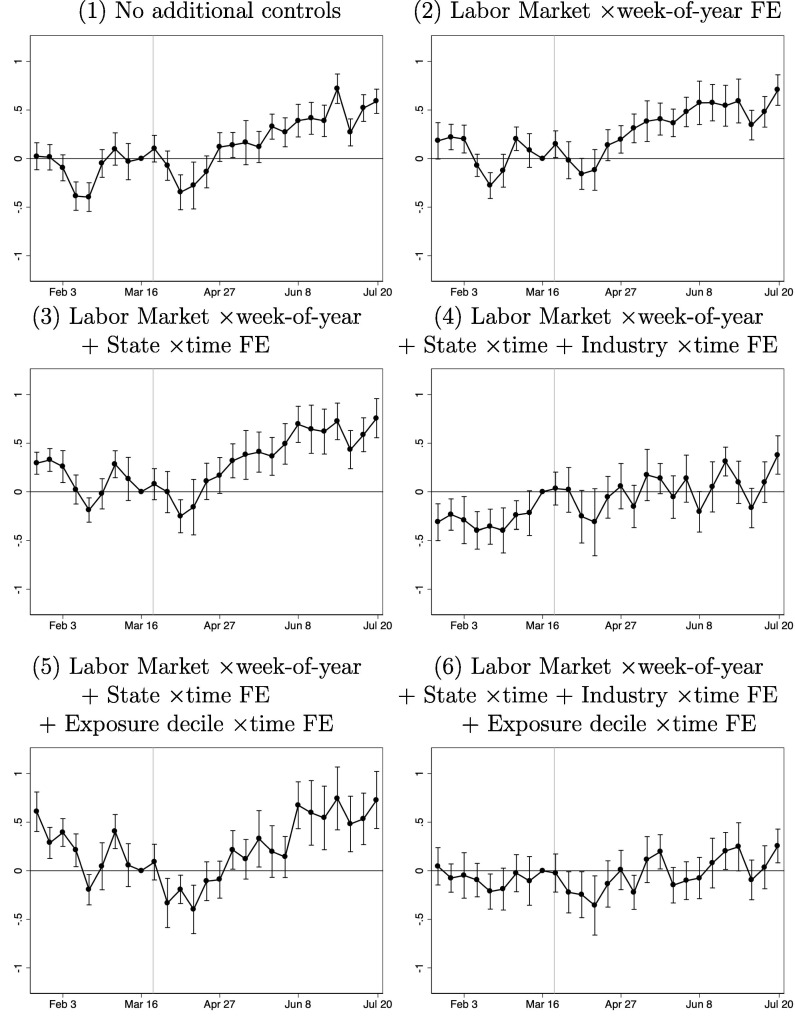

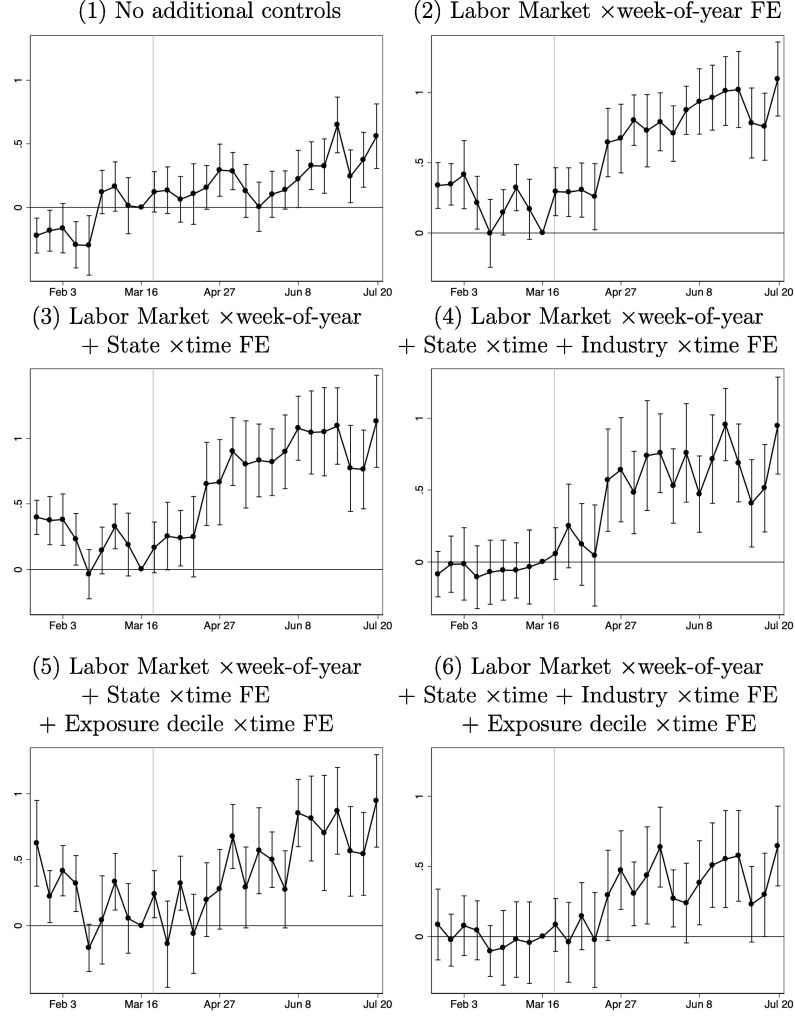

We present the estimates obtained when we add, one by one, the controls included in our preferred specification, in Fig. A.4, Fig. A.5 and Fig. A.6. All control variables contribute to making the pre-trends disappear, in line with the economic intuitions behind our estimation strategy. For instance, when we only control for seasonality, the coefficients in panel (2) of Fig. A.4 exhibit a steep increase in the weeks before the CARES Act, which might reflect the abrupt surge in unemployment among low-wage workers. Although the different controls seem to improve our identification of the effect of FPUC, it is reassuring to note that our qualitative conclusions do not crucially depend on one particular specification. The estimates obtained in all the specifications in Fig. A.4 are suggestive of a negative effect of FPUC on job search. We don’t find negative coefficients for vacancy creation in any of the specifications in Fig. A.5; we sometimes obtain positive coefficients, which could capture a stimulus effect. Finally, all specifications in Fig. A.6 are suggestive of a positive effect of FPUC on tightness.

Fig. A.4.

The impact of FPUC on applications week by week. Notes: This Figure reports the estimates from regressions of logged count of applications on the interaction of each week around the enactment of the FPUC and the potential increase in UI generosity . We use a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level —where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. All models include calendar week and local labor market fixed effects. We also add various controls in different panels. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Thin lines deNote 95% confidence intervals, based on robust SE clustered at the state level.

Fig. A.5.

The impact of FPUC on new vacancies week by week. Notes: This Figure reports the estimates from regressions of logged count of new vacancies on the interaction of each week around the enactment of the FPUC and the potential increase in UI generosity . We use a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level —where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. All models include calendar week and local labor market fixed effects. We also add various controls in different panels. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Thin lines deNote 95% confidence intervals, based on robust SE clustered at the state level.

Fig. A.6.

The impact of FPUC on labor market tightness, week by week. Notes: This Figure reports the estimates from regressions of logged labor market tightness (vacancies/applications) on the interaction of each week around the enactment of the FPUC and the potential increase in UI generosity . We use a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level —where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. All models include calendar week and local labor market fixed effects. We also add various controls in different panels. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Thin lines deNote 95% confidence intervals, based on robust SE clustered at the state level.

We then analyze more flexibly the relationship between labor market outcomes and the increase in unemployment benefits induced by FPUC in Table A.7. We look separately at the evolution of outcomes in local labor markets at different quartiles of the distribution of relative increase in benefits in columns (1)-(3). As expected, the largest increase in unemployment benefits was associated with the largest decrease in applications. The effect for the third and fourth quartile is essentially the same, suggesting there is no additional decrease in applications for very high increases in the replacement rate. In columns (4)-(6) we estimate the effect of the absolute increase in replacement rates. The results are qualitatively similar. We also show that our results are robust to using alternative samples of local labor markets in Table A.8.

Finally, to confirm our main results, we focus on the construction sector, where job loss before FPUC was not systematically correlated with earnings. While the estimates are naturally less precise than in the full sample, we see similar qualitative patterns: FPUC decreased applications, had no effect on vacancies, and therefore ultimately increased labor market tightness (Fig. A.7). These results are reassuring: our conclusions hold in a segment of the economy where there are no substantial factors confounding the identification of the effect of FPUC.

Fig. A.7.

The impact of FPUC on applications, vacancies and tightness in the construction sector, week by week. Notes: This Figure reports the estimates from regressions of the logged count of applications, the logged count of vacancies, and the logged labor market tightness (i.e. ratio of vacancies over applications) in the construction sector on the interaction of each week around the enactment of the FPUC and the potential increase in UI generosity . The coefficients before the enactment of the FPUC help test our identification assumption. The coefficients after represent the elasticity of the outcome with respect to benefits levels. We use a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. We include calendar week and local labor market fixed effects. We control for seasonality using week-of-yearlocal labor market fixed effects. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Thin lines deNote 95% confidence intervals, based on robust SE clustered at the state level.

5. Labor market tightness during the FPUC

5.1. The evolution of labor market tightness

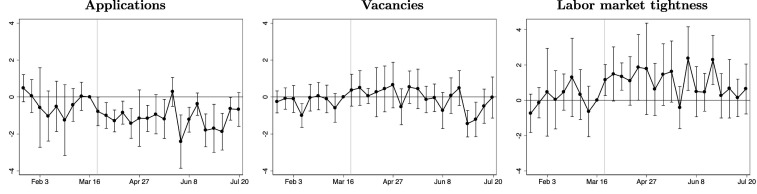

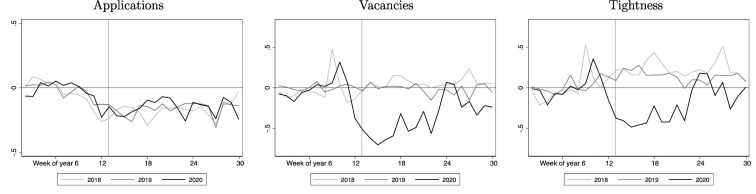

We present the evolution of seasonally adjusted applications, new vacancy postings, and labor market tightness relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020 in Fig. 2 . The number of vacancies strongly declined both before and right after FPUC. In contrast, the number of job applications exhibited limited change. This suggests that the various factors that could influence search in that period (the increase in unemployment, FPUC, the infection risk, uncertainty, etc.) largely compensated each other.12 Therefore, the evolution of vacancies drove the evolution of labor market tightness: between March and May 2020, both dropped way below their baseline level (Fig. A.9 shows that tightness was always above the May 2020 level in the preceding year).

Fig. 2.

Changes in applications, vacancies, and labor market tightness relative to Jan-Feb 2020 (seasonally adjusted). Notes: The Figure presents the seasonally adjusted changes in the total weekly count of applications, the weekly count of new posted vacancies, and labor market tightness, relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. The Figure is obtained by regressing the logged variables on the calendar week coefficients and week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation, and then subtracting to each calendar week coefficient the average of estimates for Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Fig. A.9.

Changes in applications, vacancies, and labor market tightness relative to Jan-Feb 2020, for a longer time window. Notes: The Figure presents the seasonally adjusted changes in the 3-weeks moving averages of count of applications, the weekly count of new posted vacancies, and labor market tightness, relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. The Figure is obtained by regressing the logged variables on the calendar week coefficients and week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation, and then subtracting to each calendar week coefficient the average of estimates for Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Quantitatively, seasonally adjusted labor market tightness declined by 30.6% during the FPUC period of March-July 2020 relative to January-February 2020 (Table 3 , col. 3, upper panel), reflecting a labor market more favorable to recruiting firms, despite the large increase in unemployment benefits13 . During the whole FPUC period, applications slightly increased by 4.4% (col. 1, upper panel), while vacancies declined by 26.2% (col. 2). During the reopening phase, in June-July 2020, seasonally adjusted applications, vacancies, and labor market tightness were similar to their level in Jan.-Feb. 2020 (col. 1–3, lower panel). Overall, the evidence is not consistent with significant hiring difficulties during the reopening phase.

Table 3.

Changes in labor market tightness during the period of the FPUC, relative to Jan-Feb 2020.

| Potential increase in UI |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample: | All |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

||

| Outcome: | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| FPUC period | 0.044** | −0.262*** | −0.306*** | −0.413*** | −0.334*** | −0.287*** | −0.190*** |

| (0.018) | (0.022) | (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.046) | (0.032) | |

| Week of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 613,586 | 412,050 | 297,346 | 217,616 |

| FPUC, Mar-May | 0.076*** | −0.448*** | −0.524*** | −0.547*** | −0.558*** | −0.547*** | −0.444*** |

| (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.023) | (0.021) | (0.048) | (0.035) | |

| FPUC, Jun-Jul | 0.004 | −0.030 | −0.034 | −0.246*** | −0.055 | 0.039 | 0.126*** |

| (0.019) | (0.022) | (0.025) | (0.028) | (0.040) | (0.054) | (0.037) | |

| Week of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 613,586 | 412,050 | 297,346 | 217,616 |

Notes: This Table reports changes in the count of job applications, the count of vacancies, and labor market tightness during the period of the FPUC, relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. In the upper panel, we present estimates for the total period of FPUC, and for two sub-periods in the lower panel. The estimates are obtained by regressing each logged outcome on dummy variables for the FPUC period and for all calendar weeks outside of Jan-Feb 2020, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level. We include week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation. The estimates are obtained in the full sample in col. (1)-(3), and for local labor markets in each quartile of the distribution of potential UI increase in col. (4)-(7). We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

5.2. Heterogeneity

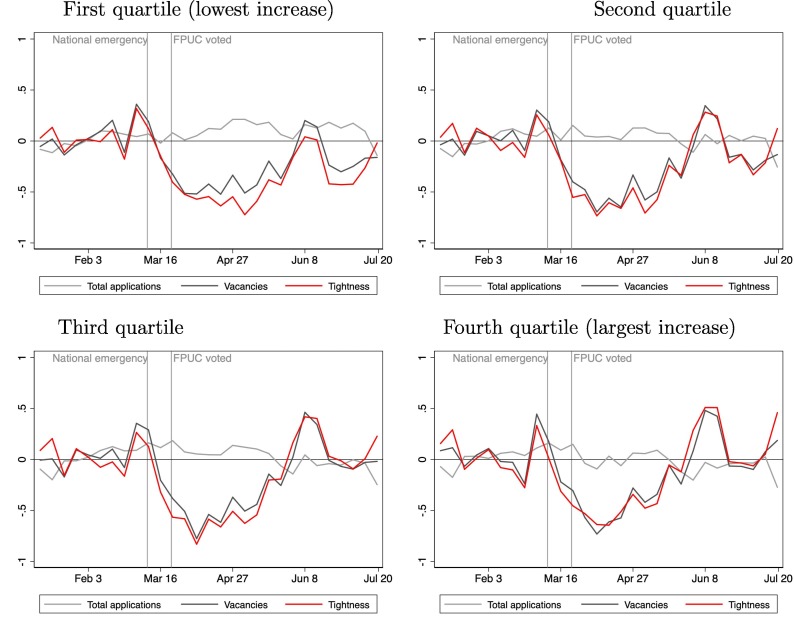

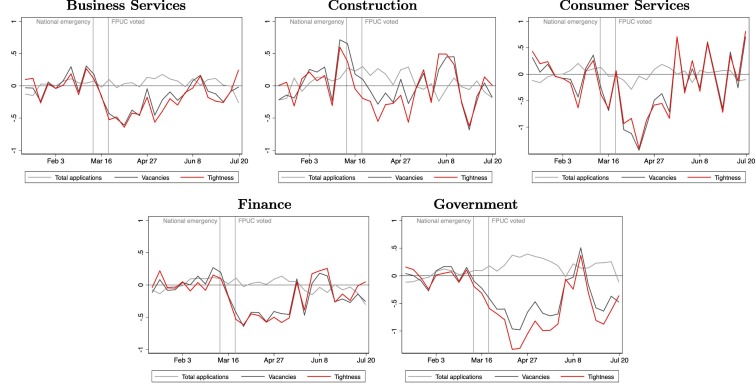

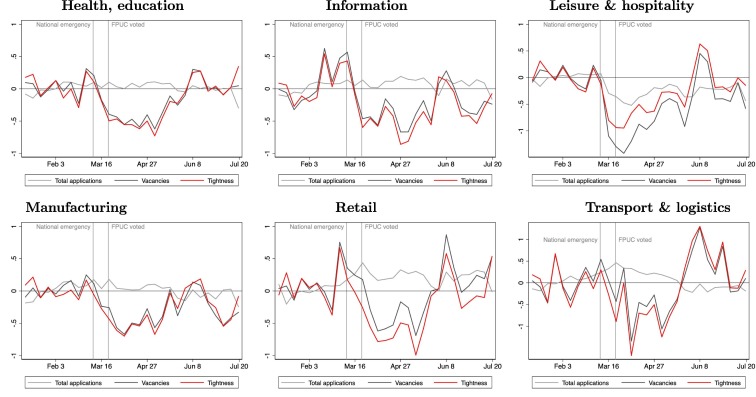

One could be concerned that recruitment difficulties increased in the local labor markets most affected by FPUC. We present the evolution of tightness by quartile of the increase in replacement rate due to FPUC, in columns 4–7 of Table 3 and graphically in Fig. A.11. We show that even in the markets most affected by FPUC, seasonally adjusted tightness was 19% lower during the FPUC period than at baseline (Table 3, col. 7). During the re-opening phase, tightness for the fourth quartile was slightly higher (12.6%) than at baseline. For the three lower quartiles (col. 4–6), tightness during reopening remained below or at baseline. Finally, Fig. A.12 and Fig. A.13 show that the evolution of applications, vacancies and labor market tightness are qualitatively similar across sectors. The magnitudes of the fluctuations differ by sector in expected ways: for example, during the lockdown, vacancies in sectors that were directly affected like leisure & hospitality and transport & logistics understandably decreased more than in other sectors. In leisure & hospitality, applications also declined during the FPUC period, suggesting that workers might have decreased their search due to infection risks. In construction, which we analyzed above, the evolution of tightness is similar to that in other sectors.

Fig. A.11.

Changes in applications, vacancies and labor market tightness relative to Jan-Feb 2020, by UI increase quartile. Notes: The Figure presents, for each quartile of the increase in the replacement rate of UI, the seasonally adjusted changes in the total weekly count of applications, the weekly count of new posted vacancies, and labor market tightness (ratio of vacancies over total applications), relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. The Figure is obtained by regressing the logged variables on the calendar week coefficients and week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation, and then subtracting to each calendar week coefficient the average of estimates for Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Fig. A.12.

The evolution of job applications & job postings in specific sectors: Notes: The Figure presents, fr each industry, the seasonally adjusted changes in the total weekly count of applications, the weekly count of new posted vacancies, and labor market tightness (ratio of vacancies over total applications), relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. The Figure is obtained by regressing the logged variables on the calendar week coefficients and week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation, and then subtracting to each calendar week coefficient the average of estimates for Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Fig. A.13.

The evolution of job applications & job postings in specific sectors: Notes: The Figure presents, for each industry, the seasonally adjusted changes in the total weekly count of applications, the weekly count of new posted vacancies, and labor market tightness (ratio of vacancies over total applications), relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. The Figure is obtained by regressing the logged variables on the calendar week coefficients and week-of-year fixed effects to control for seasonal variation, and then subtracting to each calendar week coefficient the average of estimates for Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

6. Discussion

6.1. Model of the labor market

One important question in general equilibrium models is how unemployment benefits affect vacancy creation (Landais et al., 2018b). Our finding that FPUC did not affect vacancy creation is consistent with job rationing, where vacancy creation primarily depends on the marginal product of labor—rather than wages, or recruiting costs (Michaillat, 2012). In job rationing models, unemployment insurance has more limited effects on employment: because of the limited vacancy response, UI increases labor market tightness, i.e. decreases the competition among job seekers and raises the returns to each unit of search effort. Additionally, labor market tightness was particularly low when FPUC was implemented, such that decreasing search effort likely had limited effects on unemployment. Our findings hence help explain why prior studies have found no effect of FPUC on unemployment (Bartik et al., 2020, Altonji et al., 2020, Finamor and Scott, 2021, Dube, 2020).

6.2. The impact of FPUC on welfare

Our results speak to aspects of the impact of FPUC on welfare that have to do with labor market tightness. Landais et al. (2018b) formalize that the welfare impact of unemployment insurance depends on three elements: first, its impact on labor market tightness; second, the impact of tightness on welfare, and third, the trade-off between consumption smoothing and moral hazard. Our paper provides evidence on the first two. We show that FPUC increased tightness. And we document that tightness at that time was very low relative to January-February 2020, hence likely sub-optimal. Note that the level of tightness in January-February 2020 provides a natural benchmark — as the labor market immediately before the crisis was considered healthy — but it may not have been exactly optimal (see Landais et al. (2018a) for an empirical assessment of the optimal tightness level, and Forsythe et al. (2020b) for a discussion of the evolution of tightness up to the COVID-19 crisis). Our results together suggest that FPUC increased welfare by bringing labor market tightness back towards a more efficient level. Intuitively, it strongly decreased the cost of unemployment for job seekers without a commensurate increase in recruitment difficulties for employers. Importantly, this conclusion also holds for the reopening phase (June-July 2020). During this period, one could have expected a clearer negative impact of FPUC on vacancy creation, since economic activity was no longer hindered by lockdown measures. However, we find no evidence of this. One could also have feared labor market tightness to be particularly high during this period, since firms’ recruiting was picking up while many unemployed workers were receiving FPUC. We show that labor market tightness was just back to its pre-pandemic level, despite the positive effect of FPUC on tightness. In the absence of FPUC, the counterfactual level of tightness would likely have remained lower than at baseline. While the positive effects of UI extensions on tightness were likely welfare-improving in March-July 2020, they could be detrimental if tightness were far above its optimal level.

Our analysis focuses on labor market tightness. Fully assessing the welfare impact of unemployment insurance in the framework of Landais et al. (2018b) would also require accounting for the classical trade-off between the positive effect on the consumption of UI recipients and the negative effect on their re-employment. The findings by Ganong et al. (2021) suggest important gains from consumption smoothing in the case of FPUC. Moreover, FPUC potentially had other spillover effects, beyond the labor market externalities modeled in Landais et al. (2018b). First, FPUC likely boosted employment through a stimulus effect (Ganong et al., 2021). Second, the sanitary situation might have made it desirable to have workers temporarily outside of the labor force, to the extent that they were less likely to get infected with COVID-19 (Fang et al., 2020). Overall, these additional considerations also point towards the desirability of high unemployment insurance in March-July 2020.

7. Conclusion

During the COVID-19 crisis, a 10% increase in unemployment benefits due to the Federal Unemployment Pandemic Assistance (FPUC) led to a 3.6% decline in Glassdoor job applications. Since the FPUC had no effect on vacancies, its effect on applications led to a commensurate 3.3% increase in labor market tightness (vacancies/applications). However, despite the negative effect of FPUC on applications, seasonally adjusted aggregate job applications remained fairly stable during the FPUC period of March-July 2020. With a 4% increase in aggregate applications and a steep 26% decline in job vacancies relative to January-February 2020, seasonally adjusted labor market tightness declined by 31%. Even in the top 25% of labor markets with the highest increase in the level of unemployment benefits, tightness still declined by 19% during the FPUC period. By decreasing applications, FPUC has thus contributed to lifting up a depressed labor market tightness, likely increasing welfare. In a context of excessive competition for jobs among workers, more generous unemployment insurance reduces wasteful applications and has little effect on employment. Our results can help explain why higher unemployment benefits had no effect on employment after the CARES Act (Bartik et al., 2020, Altonji et al., 2020, Dube, 2020).

Footnotes

We would like to thank Hyeri Choi and Jie Guan for excellent research assistance. We would like to thank for their very helpful comments Antoine Bertheau, Sydnee Caldwell, Pascal Noel, as well as the participants of the seminars in the University of Copenhagen, UCD Dublin, Harvard, Essex/Royal Holloway/Bristol, and in the NBER Labor Spring Meeting.

The data is a subset of total applications on Glassdoor. To enhance data quality, Glassdoor’s data processing retains likely people (not bots) who apply after organically searching for jobs on Glassdoor (rather than being redirected to the job posting from elsewhere, e.g. from Glassdoor emails or from paid advertisements on other sites).

Tightness is often defined as vacancies/unemployment. As suggested by theory (Landais et al., 2018b), we adjust for search intensity and define tightness as vacancies/applications.

The count of job openings reported in Glassdoor’s Job Market Report represents 81% of the count job openings reported in the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey.

Karabarbounis and Pinto (2018) show that the average and variance of the distribution of salaries within geographical region and within industry are fairly representative when compared against the Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, and the Panel Study of Income Dynamics.

This is the case for most individuals eligible for unemployment insurance, given the average number of days worked reported in the 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplement (ASEC) of the CPS.

The CARES Act also instated an additional 13 weeks of benefits for those whose regular unemployment benefits were exhausted (Pandemic Emergency Unemployment Compensation), and extended the access to unemployment insurance to workers not traditionally eligible, but who were unable to work because of the public health emergency (Pandemic Unemployment Assistance).

The estimates would be identical if we instead analyzed the changes in logged outcomes associated with changes in logged replacement rates: we only build this time-invariant replacement rate ratio to be able to estimate coefficients for periods before the FPUC was implemented, and hence test the validity of our identification strategy, as explained in what follows.

We use exposure deciles for more flexibility, but our results are similar if we instead control linearly for exposureweek.

Extensions in potential benefit duration kick in after July 2020 for most workers, and they only vary by state, so they do not bias our estimates.

There is substantial variation in earnings across frequent occupations in the construction sector in CPS-ORG: for instance, they range around $1410 for community association managers; $1020 for electricians; $960 for construction laborers.

We present the estimates from the same specifications for vacancies and tightness in Table A.5.

In the non seasonally adjusted series (Fig. A.8, left panel), applications decline a bit after FPUC, but this pattern occurs every year (Fig. A.10).

Results without controlling for seasonal variation are in Fig. A.9.

Appendix A.

Fig. A.8.

Changes in applications, vacancies, and labor market tightness relative to Jan-Feb 2020, not seasonally adjusted. Notes:The Figure presents the changes in tightness (ratio of the weekly count of new posted vacancies over weekly count of applications), relative to their baseline levels in Jan-Feb 2020. We regress the logged tightness on the time coefficients, and then subtract the average of the estimates obtained for the period Jan-Feb 2020, such that each coefficient represents the relative variation with respect to the average level in Jan-Feb 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Fig. A.10.

Weekly changes in applications, vacancies and tightness relative to Jan-Feb, each year. Notes: The Figure presents the weekly changes in the count of applications, of new posted vacancies and of labor market tightness (ratio of the weekly count of new posted vacancies over weekly count of applications), relative to their baseline levels in Jan.-Feb., such that each coefficient represents the relative variation with respect to the average level in Jan.-Feb. We present them separately for the years 2018, 2019 and 2020. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS.

Table A.1.

Descriptive statistics: Count of applications and job postings on Glassdoor by industry.

| Data source |

Glassdoor data |

CPS |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Application count | Job posting count | US labor | ||

| per weekindustry |

per weekindustry |

force | |||

| Mean | % | Mean | % | % | |

| Agriculture | 15 | 0.00 | 7 | 0.00 | 1.59 |

| Business Service | 81,112 | 17.78 | 84,050 | 13.84 | 12.42 |

| Construction | 4,420 | 0.97 | 3,776 | 0.62 | 7.30 |

| Consumer Service | 6,447 | 1.41 | 8,135 | 1.34 | 4.82 |

| Finance | 49,031 | 10.75 | 39,249 | 6.46 | 6.80 |

| Government | 7,047 | 1.55 | 8,421 | 1.39 | 4.67 |

| Health, Education | 68,506 | 15.02 | 164,691 | 27.12 | 22.51 |

| Information | 105,109 | 23.05 | 65,283 | 10.75 | 1.80 |

| Leisure, hospitality | 30,366 | 6.66 | 72,982 | 12.02 | 9.34 |

| Manufacturing | 46,673 | 10.23 | 33,052 | 5.44 | 9.88 |

| Retail | 43,129 | 9.46 | 69,722 | 11.48 | 12.92 |

| Transportation, warehousing | 14,217 | 3.12 | 57,889 | 9.53 | 5.66 |

Notes: This Table presents the mean weekly count of applications and new job postings and the proportion of applications and new vacancy postings by industry, in our study sample. In the last column, the Table reports the proportion of US labor force by industry based on the CPS in 2018–2020.

Table A.2.

Descriptive statistics in our study sample.

| Mean | SD | p25 | p50 | p75 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | |

| Count of applications, each week in each local labor market | 82.2 | 204.3 | 12.0 | 26.0 | 70.0 |

| Count of vacancies, each week in each local labor market | 189.6 | 659.1 | 16.0 | 44.0 | 126.0 |

| Tightness (vacancies/ applications) | 4.7 | 22.6 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 3.4 |

| Replacement rate without FPUC | 43.6 | 8.4 | 38.2 | 45.4 | 49.2 |

| Replacement rate with FPUC | 146.1 | 47.9 | 107.3 | 143.5 | 173.8 |

Notes: This Table presents descriptive statistics in our study sample. All variables are computed for each calendar week from January 2018 to July 2020, in each local labor market. We use weights reflecting the size of each Stateindustryoccupation in the labor force in the CPS. Note that the distribution of potential replacement rates in local labor markets in this Table is not directly comparable to the distribution of replacement rate in the population of unemployed workers computed in Ganong et al. (2020): the level of observation is different since one observation represents one local labor market in our analysis, while one observation represents one worker who lost their job during the COVID-19 crisis in Ganong et al. (2020). However, we note that these statistics are relatively close, with the first quartile of replacement rate ranging around 103%, the median around 145%, third quartile around 195% (Ganong et al., 2020).

Table A.3.

The probability of unemployment, in January-March 2020.

| Probability of unemployment | |

|---|---|

| WageDecile2 | −0.547*** |

| (0.117) | |

| WageDecile3 | −0.406*** |

| (0.123) | |

| WageDecile4 | −0.841*** |

| (0.133) | |

| WageDecile5 | −0.934*** |

| (0.150) | |

| WageDecile6 | −1.148*** |

| (0.160) | |

| WageDecile7 | −0.975*** |

| (0.158) | |

| WageDecile8 | −1.211*** |

| (0.166) | |

| WageDecile9 | −1.119*** |

| (0.166) | |

| WageDecile10 | −0.993*** |

| (0.167) | |

| State FE | ✓ |

| Occupation FE | ✓ |

| Industry FE | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 49,779 |

Notes: This table reports the estimates from the logit regressions of a dummy for unemployment on local labor market characteristics: wage deciles, occupation fixed effects, (two-digit) industry fixed effects and state fixed effects. The information on workers’ unemployment status, industry, and state come from the monthly CPS data for January-March 2020, and information on their prior earnings come from the Outgoing Rotation Group data for 2019. The two datasets are matched at the individual level. We use individual survey weights from the CPS 2020. Note that as we use the information on earnings from ORG 2019, we could also have computed alternative weights accounting for the composition of respondents in ORG 2019 and correcting for missing earnings values. We use the standard survey weights for replicability, but we checked that this does not affect our results. Robust standard errors in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.4.

The wage gradient in the probability of unemployment, by industry.

| Probability of unemployment |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| ln(prior earnings) | −0.372*** | ||

| (0.024) | |||

| Agriculture ln(prior earnings) | −0.525*** | −0.541*** | |

| (0.198) | (0.208) | ||

| Mining ln(prior earnings) | −0.061 | −0.047 | |

| (0.393) | (0.395) | ||

| Construction ln(prior earnings) | −0.096 | −0.097 | |

| (0.088) | (0.089) | ||

| Manufacturing ln(prior earnings) | −0.531*** | −0.553*** | |

| (0.097) | (0.096) | ||

| Retail ln(prior earnings) | −0.433*** | −0.449*** | |

| (0.081) | (0.081) | ||

| Transportation ln(prior earnings) | −0.521*** | −0.539*** | |

| (0.111) | (0.110) | ||

| Information ln(prior earnings) | −0.248* | −0.236* | |

| (0.130) | (0.134) | ||

| Finance ln(prior earnings) | −0.266*** | −0.277*** | |

| (0.057) | (0.059) | ||

| Business services ln(prior earnings) | −0.388*** | −0.403*** | |

| (0.066) | (0.067) | ||

| Education & health ln(prior earnings) | −0.360*** | −0.370*** | |

| (0.043) | (0.045) | ||

| Leisure & hospitality ln(prior earnings) | −0.262*** | −0.264*** | |

| (0.087) | (0.088) | ||

| Consumer services ln(prior earnings) | −0.657*** | −0.663*** | |

| (0.132) | (0.137) | ||

| Government ln(prior earnings) | −0.603*** | −0.575*** | |

| (0.136) | (0.137) | ||

| Industry FE | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| State FE | – | – | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 54,023 | 54,017 | 54,017 |

Notes: This table reports the estimates from the logit regressions of a dummy for unemployment on local labor market characteristics: prior earnings, two-digit industries and states. The information on workers’ unemployment status, industry, and state come from the monthly CPS data for January-March 2020, and information on their prior earnings come from the Outgoing Rotation Group data for 2019. The two datasets are matched at the individual level. We use individual survey weights from the CPS 2020. Note that as we use the information on earnings from ORG 2019, we could also have computed alternative weights accounting for the composition of respondents in ORG 2019 and correcting for missing earnings values. We use the standard survey weights for replicability, but we checked that this does not affect our results. Robust standard errors in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.5.

Additional results on the impact of FPUC on vacancies and tightness.

| Vacancies (ln) |

Tightness (ln) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | |

| FPUC period, March | −0.123 | 0.021 | ||||||

| (0.075) | (0.084) | |||||||

| FPUC period, April | −0.247** | 0.138 | ||||||

| (0.115) | (0.133) | |||||||

| FPUC period, May | −0.011 | 0.425*** | ||||||

| (0.069) | (0.106) | |||||||

| FPUC period, June | 0.026 | 0.421*** | ||||||

| (0.087) | (0.133) | |||||||

| FPUC period, July | 0.111 | 0.437*** | ||||||

| (0.092) | (0.132) | |||||||

| FPUC periodLockdown | −0.109 | 0.246** | ||||||

| (0.066) | (0.094) | |||||||

| FPUC periodOpen | 0.063 | 0.430*** | ||||||

| (0.084) | (0.126) | |||||||

| FPUC period Telework | 0.079 | 0.461*** | ||||||

| (0.098) | (0.153) | |||||||

| FPUC period Not telework | −0.066 | 0.245** | ||||||

| (0.077) | (0.114) | |||||||

| FPUC period Telework | −0.096 | −0.227 | ||||||

| (0.083) | (0.150) | |||||||

| FPUC period High temp layoff | 0.044 | 0.217 | ||||||

| (0.114) | (0.139) | |||||||

| FPUC period Low temp layoff | −0.148 | 0.267** | ||||||

| (0.090) | (0.118) | |||||||

| FPUC period High temp layoff | −0.193 | 0.168 | ||||||

| (0.171) | (0.179) | |||||||

| P-Value Test May = July | .047 | .852 | ||||||

| P-Value Test Lockdown = Open | .004 | .008 | ||||||

| P-Value Test Telework = Not Telework | .062 | .116 | ||||||

| P-Value Test High temp layoff = Low temp layoff | .178 | .741 | ||||||

| Exposure decileTime FE, IndustryTime FE, StateTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labor marketWeek of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,496,988 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,496,988 | 1,523,252 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimates from the regression of logged vacancies and tightness on various independent variables, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.6.

Additional results on the impact of FPUC, by prevalence of temporary layoff.

| Applications (ln) | Vacancies (ln) | Tightness (ln) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| (1) | (2) | (3) | |

| FPUC period Lowest quartile of temp layoff | −0.351*** | −0.380*** | −0.028 |

| (0.091) | (0.083) | (0.126) | |

| FPUC period 2nd quartile of temp layoff | −0.299*** | −0.020 | 0.279* |

| (0.094) | (0.123) | (0.142) | |

| FPUC period 3rd quartile of temp layoff | −0.211* | 0.077 | 0.288* |

| (0.107) | (0.148) | (0.155) | |

| FPUC period Highest quartile of temp layoff | −0.122 | 0.001 | 0.123 |

| (0.103) | (0.133) | (0.176) | |

| FPUC period 2nd quartile of temp layoff | −0.160 | −0.398** | −0.238 |

| (0.110) | (0.165) | (0.180) | |

| FPUC period 3rd quartile of temp layoff | −0.308** | −0.507** | −0.198 |

| (0.143) | (0.204) | (0.185) | |

| FPUC period Highest quartile of temp layoff | −0.398** | −0.339* | 0.059 |

| (0.151) | (0.188) | (0.244) | |

| Exposure decileTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IndustryTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| StateTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labor marketWeek of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimates from the regression of logged vacancies and tightness on various independent variables, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.7.

Robustness checks on the impact of FPUC on applications, vacancies and tightness.

| Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Q2 of FPUC period | −0.113*** | −0.022 | 0.091 | |||

| (0.029) | (0.046) | (0.058) | ||||

| Q3 of FPUC period | −0.184*** | 0.005 | 0.189*** | |||

| (0.037) | (0.042) | (0.066) | ||||

| Q4 of FPUC period | −0.188*** | 0.007 | 0.195*** | |||

| (0.046) | (0.037) | (0.065) | ||||

| FPUC period | −0.218*** | −0.013 | 0.205*** | |||

| (0.032) | (0.036) | (0.045) | ||||

| Exposure decileTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| IndustryTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| StateTime FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Labor marketWeek of year FE | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| No. of Obs | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 | 1,523,252 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimates from the regression of logged outcomes on various independent variables, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. Rep is the replacement rate. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.8.

Robustness check: The impact of FPUC on applications, vacancies and tightness, estimated in different local labor market samples.

| Sample | More than 250 applications |

More than 500 applications |

More than 1500 applications |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness |

| (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | (ln) | |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | (8) | (9) | |

| FPUC period | −0.204*** | 0.096 | 0.300*** | −0.272*** | 0.045 | 0.318** | −0.370*** | −0.067 | 0.304** |

| (0.067) | (0.068) | (0.096) | (0.079) | (0.087) | (0.122) | (0.086) | (0.103) | (0.138) | |

| No. of Obs | 3,157,174 | 3,157,174 | 3,157,174 | 2,300,914 | 2,300,914 | 2,300,914 | 1,170,088 | 1,170,088 | 1,170,088 |

Notes: This Table reports the estimates from the regression of logged outcomes on various independent variables, in a panel at the calendar week and local labor market level—where local labor markets are defined as as the interaction of state, 2-digit occupations and 2-digit industries and wage deciles. We estimate the results on different subsamples, based on the total count of applications in the local labor market in the period 2018–2020 (our main results are estimated on local labor markets with more than 1000 applications in total during 2018–2020). Rep is the replacement rate. We use weights to reflect the proportion of the labor force in each Stateindustryoccupation in the CPS. Robust standard errors clustered at the state level are in parenthesis (* p, ** p, *** p).

Table A.9.

Changes in labor market tightness during the period of the FPUC relative to Jan-Feb 2020, without accounting for seasonal variation.

| Potential increase in UI | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample: | All |

Q1 |

Q2 |

Q3 |

Q4 |

||

| Total | |||||||

| Outcome: | Applications | Vacancies | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness | Tightness |

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) | |

| FPUC period | −0.128*** | −0.237*** | −0.109*** | −0.221*** | −0.127*** | −0.091* | 0.004 |

| (0.021) | (0.024) | (0.024) | (0.022) | (0.032) | (0.046) | (0.042) | |

| Week of year FE | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| No. of Obs | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 613,586 | 412,050 | 297,346 | 217,616 |

| FPUC, Mar-May | −0.117*** | −0.415*** | −0.298*** | −0.356*** | −0.325*** | −0.310*** | −0.201*** |

| (0.022) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.023) | (0.024) | (0.043) | (0.043) | |

| FPUC, Jun-Jul | −0.142*** | −0.014 | 0.128*** | −0.052** | 0.121** | 0.183*** | 0.260*** |

| (0.022) | (0.027) | (0.029) | (0.026) | (0.046) | (0.056) | (0.045) | |

| Week of year FE | No | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| No. of Obs | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 1,540,598 | 613,586 | 412,050 | 297,346 | 217,616 |