Abstract

Mitochondria are increasingly recognized as cellular hubs to orchestrate signaling pathways that regulate metabolism, redox homeostasis, and cell fate decisions. Recent research revealed a role of mitochondria also in innate immune signaling; however, the mechanisms of how mitochondria affect signal transduction are poorly understood. Here, we show that the NF‐κB pathway activated by TNF employs mitochondria as a platform for signal amplification and shuttling of activated NF‐κB to the nucleus. TNF treatment induces the recruitment of HOIP, the catalytic component of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), and its substrate NEMO to the outer mitochondrial membrane, where M1‐ and K63‐linked ubiquitin chains are generated. NF‐κB is locally activated and transported to the nucleus by mitochondria, leading to an increase in mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites in a HOIP‐dependent manner. Notably, TNF‐induced stabilization of the mitochondrial kinase PINK1 furthermore contributes to signal amplification by antagonizing the M1‐ubiquitin‐specific deubiquitinase OTULIN. Overall, our study reveals a role for mitochondria in amplifying TNF‐mediated NF‐κB activation, both serving as a signaling platform, as well as a transport mode for activated NF‐κB to the nuclear.

Keywords: HOIP, NEMO, OTULIN, PINK1, ubiquitin

Subject Categories: Post-translational Modifications & Proteolysis, Signal Transduction

TNF induces remodeling of the outer mitochondrial membrane by assembling an NF‐κB signaling platform that facilitates nuclear translocation of activated NF‐κB.

Introduction

In addition to their bioenergetic and biosynthetic functions, mitochondria have emerged as potent and versatile signaling organelles to adapt metabolism to cellular demands, to communicate mitochondrial fitness to other cellular compartments, and to regulate cell death and viability (Nunnari & Suomalainen, 2012; Weinberg et al, 2015; Youle, 2019; Bock & Tait, 2020; Giacomello et al, 2020; Tiku et al, 2020; Bahat et al, 2021; Cervantes‐Silva et al, 2021). Increasing evidence implicates mitochondria in innate immune signaling, illustrating that mitochondria have been co‐opted by eukaryotic cells to react to cellular damage and to promote efficient immune responses. For example, invading pathogens expose pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), such as viral RNA, which is recognized by cytoplasmic RLRs (retinoic acid‐inducible gene‐I‐like receptors). Binding of viral RNA to RLRs induces a conformational change, allowing their recruitment to the mitochondrial RLR adaptor protein MAVS (mitochondrial antiviral signaling protein). Subsequent multimerization of MAVS at mitochondria results in the activation of the transcription factors IRF (interferon‐regulatory factor) 3, IRF7, and NF‐κB (nuclear factor‐kappaB), which regulate the expression of type 1 interferons and proinflammatory cytokines (Seth et al, 2005; Ablasser & Hur, 2020; Rehwinkel & Gack, 2020; Chowdhury et al, 2022).

NF‐κB is activated in several innate immune paradigms and is well known for its role in pathological conditions, where prolonged or profuse NF‐κB activation in reactive immune or glial cells causes inflammation. However, NF‐κB has important physiological functions in most—if not all—cell types. In the nervous system, NF‐κB maintains neuronal viability and regulates synaptic plasticity (Meffert et al, 2003; O'Riordan et al, 2006; Salles et al, 2015; Neidl et al, 2016; Dresselhaus et al, 2018). Constitutive NF‐κB activation by para‐ or autocrine loops is required for neuronal survival, and stress‐induced transient NF‐κB activation confers protection from various neurotoxic insults (Blondeau et al, 2001; Bhakar et al, 2002). Accordingly, TNF has been identified as a neuroprotective cytokine that prevents neuronal damage under various stress conditions (Cheng et al, 1994; Turrin & Rivest, 2006).

Although TNF can induce apoptotic or necroptotic cell death in certain pathological conditions, it usually protects from cell death. Engagement of TNF with its receptor TNFR1 at the plasma membrane results in the formation of signaling complex I that activates the transcription factor NF‐κB (typically p65/p50 heterodimers) in a tightly regulated manner, involving multiple phosphorylation and ubiquitination events (Hayden & Ghosh, 2014; Brenner et al, 2015; Annibaldi & Meier, 2018; Varfolomeev & Vucic, 2018). A crucial step in the activation process is the ubiquitination of NEMO (NF‐κB essential modulator) by HOIP, the catalytic component of the linear ubiquitin chain assembly complex (LUBAC), and binding of NEMO to linear ubiquitin chains by its UBAN (ubiquitin‐binding domain in ABIN and NEMO) domain (Haas et al, 2009; Rahighi et al, 2009; Tokunaga et al, 2009; Fujita et al, 2014). These events induce a conformational change and oligomerization of NEMO, activating the associated kinases IKKα and IKKβ. IKKα/β phosphorylates the NF‐κB inhibitor IκBα, which is subsequently modified by K48‐linked ubiquitin chains and degraded by the proteasome. NF‐κB heterodimers, liberated from their inhibitory binding to IκBα, are then translocated from the cytoplasm to the nucleus, where they increase the expression of anti‐apoptotic proteins or proinflammatory cytokines in a cell type‐ and context‐specific manner.

We have previously shown that the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin depends on this pathway to protect from stress‐induced neuronal cell death (Henn et al, 2007; Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013). Parkin modifies NEMO with K63‐linked ubiquitin chains and facilitates subsequent M1‐linked ubiquitination of NEMO by HOIP, supporting the concept that linear ubiquitin chains are preferentially assembled as heterotypic K63/M1‐linked chains in innate immune signaling pathways (Emmerich et al, 2013, 2016; Fiil et al, 2013; Hrdinka et al, 2016; Cohen & Strickson, 2017). Notably, in the absence of either HOIP or NEMO, Parkin cannot prevent stress‐induced cell death (Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013).

Linear or M1‐linked ubiquitination is characterized by the head‐to‐tail linkage of ubiquitin molecules via the C‐terminal carboxyl group of the donor ubiquitin and the N‐terminal methionine of the acceptor ubiquitin (Kirisako et al, 2006; Dittmar & Winklhofer, 2019; Spit et al, 2019; Oikawa et al, 2020; Fiil & Gyrd‐Hansen, 2021; Fuseya & Iwai, 2021; Jahan et al, 2021; Shibata & Komander, 2022; Tokunaga & Ikeda, 2022). Formation and disassembly of linear ubiquitin chains are highly specific processes. HOIP is the only E3 ubiquitin ligase that generates linear ubiquitin chains, whereas OTULIN is the only deubiquitinase that exclusively hydrolyses linear ubiquitin chains (Keusekotten et al, 2013; Rivkin et al, 2013; Lork et al, 2017; Verboom et al, 2021; Weinelt & van Wijk, 2021). Thus, M1‐linked ubiquitination can be studied with unique specificity, in contrast to other types of ubiquitination. Mass spectrometry data on TNF‐induced signaling networks and the interactive profile of HOIP and OTULIN directed our interest toward mitochondria (Wagner et al, 2016; Kupka et al, 2016a; Stangl et al, 2019). Here we show that TNF induces remodeling of the outer mitochondrial membrane by assembling an NF‐κB signaling platform that facilitates nuclear translocation of activated NF‐κB. HOIP plays a crucial role in this process by generating M1‐linked ubiquitin chains and stabilizing the mitochondrial kinase PINK1, which contributes to NF‐κB signal amplification through the phosphorylation of ubiquitin.

Results

TNF induces recruitment of LUBAC and the assembly of linear ubiquitin chains at mitochondria

To get insight into the subcellular localization of OTULIN and its interactive profile, we performed co‐immunoprecipitation of HA‐tagged OTULIN expressed in HEK293T cells coupled to mass spectrometry. Strict filtering criteria were applied in two independent experiments, including only proteins, which were detected by at least two unique peptides that were not present in the negative controls. By this approach, 59 potential OTULIN‐interacting proteins were identified (Appendix Fig S1A). An analysis of the subcellular localization of OTULIN‐interacting proteins indicated several mitochondrial proteins (Appendix Fig S1B), consistent with interactors screens previously performed with OTULIN and HOIP (Kupka et al, 2016a; Stangl et al, 2019). Moreover, mitochondrial proteins were found in a study on proteome‐wide dynamics of phosphorylation and ubiquitination in TNF‐induced signaling (Wagner et al, 2016). These findings prompted us to explore a possible mitochondrial localization of OTULIN and HOIP. Mitochondria from HEK293T cells were isolated and purified by subcellular fractionation using differential centrifugation followed by isopycnic density gradient centrifugation (Fig EV1A and B). Immunoblotting of purified mitochondrial fractions revealed that a small fraction of both OTULIN and HOIP co‐purified with mitochondria (Fig 1A). We wondered whether OTULIN antagonizes M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria and therefore silenced OTULIN expression by RNA interference. Immunoblotting of mitochondrial fractions using the M1‐ubiquitin‐specific antibodies 1E3 or 1F11/3F5/Y102L (Matsumoto et al, 2012) revealed a strong M1‐ubiquitin‐positive signal at mitochondria isolated from OTULIN‐silenced cells, indicating that OTULIN regulates mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination (Fig 1A and B). Based on the fact that TNF activates LUBAC (Haas et al, 2009; Rahighi et al, 2009; Tokunaga et al, 2009) and the identification of mitochondrial proteins in the proteome analysis of TNF signaling (Wagner et al, 2016), we were wondering whether TNF triggers linear ubiquitin chain formation at mitochondria. M1‐linked ubiquitin chains were detected 15 min after TNF treatment at mitochondria isolated from various cell types, such as HEK293T, HeLa, SH‐SY5Y cells, and mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) (Fig 1A–C). TNF‐induced mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination was not observed in HOIP CRISPR/Cas9 knockout (KO) cells, confirming HOIP‐dependent linear ubiquitination (Fig 1D). Co‐localization of M1‐linked ubiquitin with mitochondria after TNF treatment was also seen by immunocytochemistry followed by super‐resolution structured illumination microscopy (SR‐SIM) (Fig 1E). Consistent with an increase in mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination, the abundance of all three LUBAC components, HOIP, HOIL‐1L, and SHARPIN, was increased at mitochondria after TNF treatment (Fig 1F). Immunoblotting of mitochondrial fractions showed that M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria is a fast and transient response with maximum intensity after 15 min, which is paralleled by an increase in K63‐ubiquitination (Fig 1G). This is in line with the observation that linear ubiquitin chains are preferentially assembled as heterotypic K63/M1‐linked chains (Emmerich et al, 2013, 2016; Fiil et al, 2013; Hrdinka et al, 2016; Cohen & Strickson, 2017).

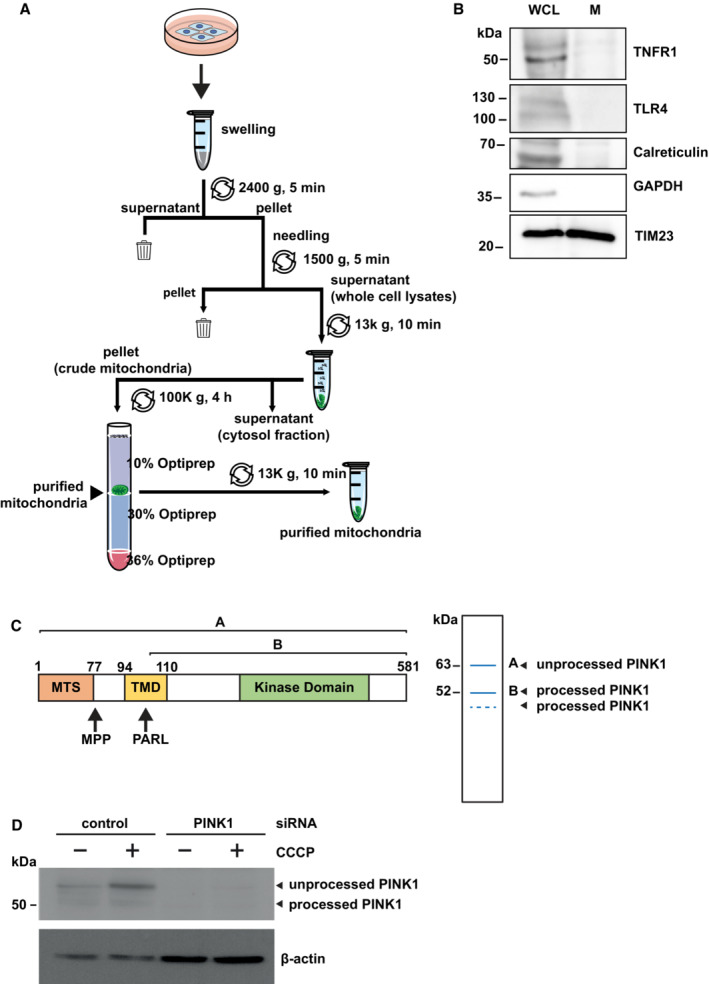

Figure EV1. Purification of mitochondria from mammalian cells and validation of the PINK1 antibody.

- Workflow for the preparation and purification of mitochondrial fractions.

- Quality control for the purity of the extracted mitochondria proteins. Purified mitochondrial fractions (M) and whole cell lysates (WCL) were tested for purity by immunoblotting using the antibodies indicated. For both the purified mitochondria and the whole cell lysate 10% of the total amount of cells was used for the analysis.

- PINK1 is proteolytically processed by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) and the presenilin‐associated rhomboid‐like protein (PARL). Domain structure of PINK1 (left panel) and representation of PINK1 species in immunoblots (right panel). MTS: mitochondrial targeting sequence; TMD: transmembrane domain.

- Validation of the PINK1 antibody in cells silenced for PINK1 expression. HEK 293T cells were transfected with control or PINK1 siRNA. 48 h after transfection, the cells were treated with CCCP (10 μM, 90 min) before harvesting. The cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using the PINK1 antibody D8G3 (rabbit mAb #6946) from Cell Signaling Technology. β‐Actin was used as a loading control.

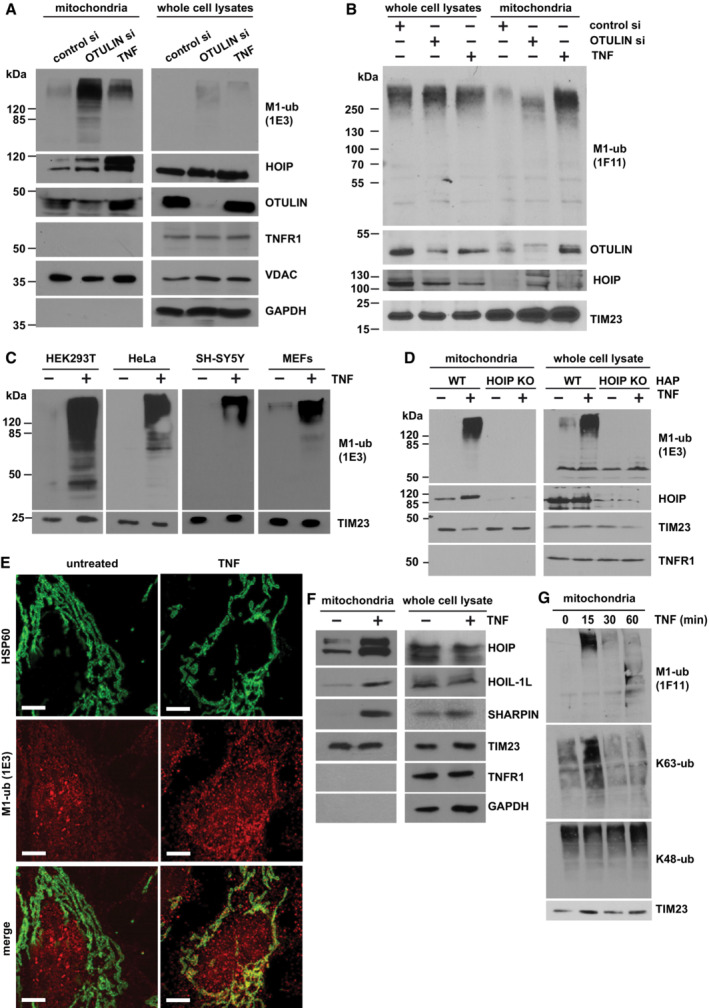

Figure 1. TNF induces M1‐linked ubiquitination at mitochondria.

-

A, BA fraction of OTULIN is localized at mitochondria where it suppresses M1‐linked ubiquitination. HEK293T cells were transfected with control or OTULIN siRNA. Cells were harvested 72 h (A) or 48 h (B) after transfection or 15 min after TNF treatment (25 ng/ml). Mitochondria were isolated by differential centrifugation and purified by ultracentrifugation using an OptiPrep™ density gradient. 38% (A) or 20% (B) of the mitochondrial fractions and 2% (A, B) of whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using the antibodies indicated. For the detection of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains, either the 1E3 (A) or the 1F11/3F5/Y102L (B) antibody was used.

-

CTNF induces M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria in various cell types. The indicated cell types were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and purified mitochondrial fractions analyzed as described in (A).

-

DTNF‐induced mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination does not occur in HOIP‐deficient cells. Wildtype (WT) and HOIP‐KO HAP cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and analyzed as described in (A).

-

EMitochondria and M1‐linked ubiquitin co‐localize after TNF treatment. SH‐SY5Y cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min), fixed, stained with antibodies against HSP60 (green) and M1‐ubiquitin (1E3, red), and analyzed by SR‐SIM. Scale bar, 5 μm.

-

FTNF induces recruitment of LUBAC components to mitochondria. HEK293T cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and analyzed as described in (A).

-

GTNF induces a fast and transient increase in M1‐ and K63‐specific ubiquitination at mitochondria. HEK 293T cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml) for the indicated time and the mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using M1‐, K63‐, and K48‐specific ubiquitin antibodies.

Source data are available online for this figure.

TNF stabilizes PINK1 at mitochondria

Next, we addressed the functional consequences of TNF‐induced mitochondrial ubiquitination. Ubiquitination of mitochondrial outer membrane proteins has been linked to a mitochondrial quality control pathway, resulting in the clearance of mitochondria by mitophagy (Nguyen et al, 2016; Whitworth & Pallanck, 2017; Harper et al, 2018; Pickles et al, 2018; Montava‐Garriga & Ganley, 2020; Goodall et al, 2022). In this pathway, depolarization of the inner mitochondrial membrane leads to an import arrest and stabilization of the mitochondrial kinase PINK1 at the outer mitochondrial membrane. PINK1 is then activated by autophosphorylation and phosphorylates ubiquitin and the ubiquitin‐like domain of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Parkin at serine 65, thereby activating Parkin (Gan et al, 2022; Kakade et al, 2022; Rasool et al, 2022; Sauve et al, 2022). Parkin‐mediated ubiquitination of outer membrane proteins recruits the autophagic machinery to eliminate damaged mitochondria. When the mitochondrial membrane potential is intact, full‐length PINK1 is imported by the translocases of the outer and inner mitochondrial membranes, the TOM and TIM23 complexes, and then PINK1 is processed to a 60 kDa intermediate species by the mitochondrial processing peptidase (MPP) in the matrix. Subsequently, the presenilin‐associated rhomboid‐like protein (PARL) and presumably other proteases in the inner membrane generate a 52‐kDa mature PINK1 fragment (Fig EV1C and D) (Whitworth et al, 2008; Jin et al, 2010; Deas et al, 2011; Meissner et al, 2011; Shi et al, 2011; Greene et al, 2012). Proteolytically processed PINK1 is retro‐translocated to the mitochondrial outer membrane, where it is ubiquitinated and rapidly degraded by the proteasome (Yamano & Youle, 2013; Liu et al, 2017). Whereas nonimported full‐length PINK1 has been linked to mitophagy induction, little is known about the function of mature PINK1 and the conditions that increase its abundance.

The artificial tethering of unbranched linear ubiquitin chains to the mitochondrial outer membrane was shown to induce mitophagy (Yamano et al, 2020), we therefore tested whether mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination induced by TNF has an impact on mitophagy. We first compared the relative amounts of PINK1 species in untreated, TNF‐stimulated, and CCCP (carbonyl cyanide 3‐chlorophenylhydrazone)‐treated cells. As expected, dissipation of the proton‐motive force across the mitochondrial inner membrane by CCCP (10 μM, 90 min) stabilized the unprocessed 63 kDa PINK1 species due to an impeded mitochondrial import. Upon 15 min TNF treatment, we observed a small but significant increase in PINK1 abundance (Fig 2A and B). Interestingly, M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria induced by TNF treatment or OTULIN silencing also increased the processed PINK1 species (Fig 2A). TNF‐induced PINK1 stabilization was accompanied by a slight increase in p‐S65‐ubiquitin and p‐S65‐Parkin signal intensities (Fig 2B).

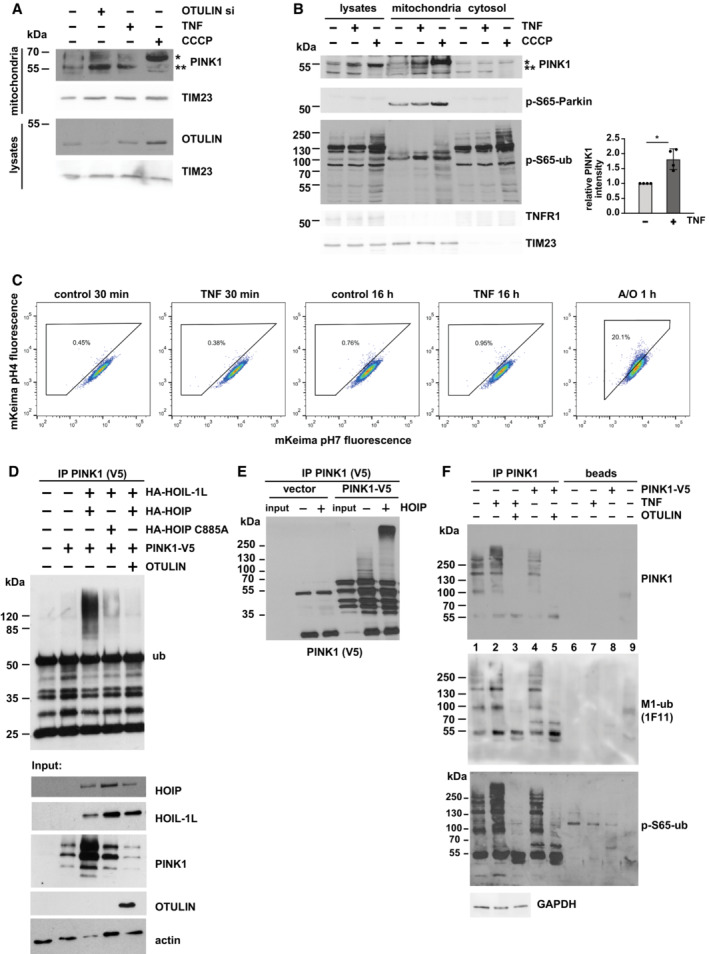

Figure 2. PINK1 is stabilized at mitochondria by LUBAC‐mediated ubiquitination.

-

A, BPINK1 is stabilized by TNF treatment. HEK293T cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) or CCCP (10 μM, 90 min) before harvesting or incubated with OTULIN‐specific siRNA for 48 h (A). Purified mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies. Quantification of PINK1‐specific signals normalized to TIM23 is shown in the right panel. Data represent the mean values with standard deviations of four independent experiments. *P < 0.05. A two‐tailed nonparametric Mann–Whitney U‐test was used to analyze statistical significance. In (A), *unprocessed PINK1; **processed PINK1.

-

CTNF‐induced PINK1 stabilization does not induce mitophagy. HeLa cells expressing mt‐mKeima were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml) for 30 min or 16 h. As a control, mt‐mKeima ‐expressing Hela cells were treated with antimycin A and oligomycin (A/O, 10 μM each) for 1 h. The analysis was done by flow cytometry gating lysosomal and neutral mt‐mKeima.

-

DCatalytically active HOIP ubiquitinates overexpressed PINK1. HEK293T cells were transfected with the plasmids indicated. After 24 h, the cells were harvested under denaturing conditions and PINK1 was immunoprecipitated via the V5 tag followed by immunoblotting against ubiquitin.

-

ERecombinant HOIP ubiquitinates PINK1 in vitro. V5‐tagged‐PINK1 immunoprecipitated from transiently transfected HEK293T cells via the V5 tag was incubated with recombinant mouse Ube1, UBE2L3, C‐terminal HOIP, and ubiquitin for in vitro ubiquitination. The samples were then analyzed by immunoblotting using V5 antibodies.

-

FEndogenous PINK1 is modified with M1‐ubiquitin chains after TNF treatment. HEK293T cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min), then endogenous PINK1 was immunoprecipitated from mitochondrial fractions. Cells mildly overexpressing PINK1‐V5 were also included (lanes 4, 5, 8), to make sure that the immunoreactive bands seen for endogenous PINK1 indeed correspond to PINK1. As a control for the presence of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains, immunoprecipitated PINK1 was treated with recombinant OTULIN. As controls for the specificity of the immunoprecipitation, beads only (lanes 6–8) and beads plus IgG (lane 9) were included. The samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against PINK1, M1‐ubiquitin, and phosphorylated ubiquitin. For immunoprecipitation of overexpressed PINK1, only 50% of cells were used in comparison to the immunoprecipitation of endogenous PINK1.

Source data are available online for this figure.

A kinetic analysis of TMRE (tetramethylrhodamine ethyl ester) fluorescence in TNF‐treated cells indicated a mild transient increase in the membrane potential between 15 and 60 min (Fig EV2A), revealing that PINK1 was not stabilized by dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential in TNF‐treated cells. Consistent with this result, TNF‐induced PINK1 stabilization at mitochondria did not induce mitophagy. Quantitative assessment of mitophagy by flow cytometry using the fluorescent reporter mt‐mKeima did not reveal changes in mitophagic activity induced by TNF treatment up to 16 h (Figs 2C and EV2C). Moreover, mitophagy was not affected by OTULIN silencing or overexpression, suggesting that M1‐linked ubiquitin chains do not regulate mitophagy (Fig EV2C–E), in line with proteomic ubiquitin profiling (Ordureau et al, 2014, 2018).

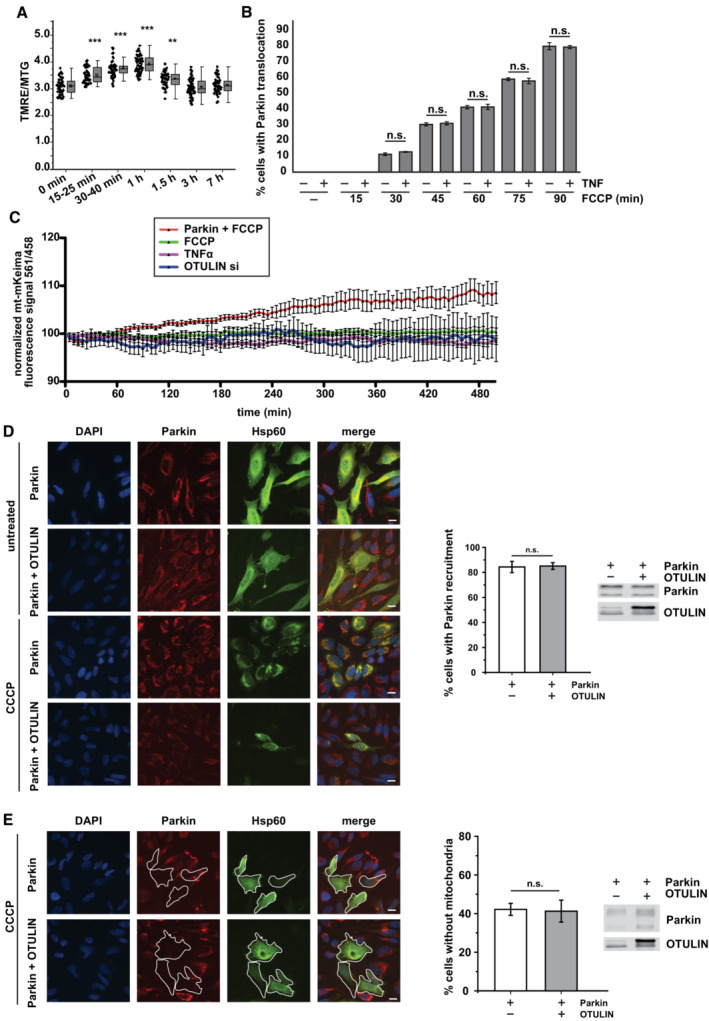

Figure EV2. TNF‐induced mitochondrial membrane remodeling effect is not linked to mitophagy.

- TNF‐induced PINK1 stabilization is not associated with a decrease in the mitochondrial membrane potential. HeLa cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and the mitochondrial membrane potential was assessed by the fluorescence signal intensity ratio of TMRE and MitoTracker™ Green (MTG), One‐way ANOVA, n = 2 (technical replicates). Each point presents the data from one cell (biological replicate). Box‐and Whiskers plots: The error bars denote the standard deviation (SD), and the boxes represent the 25th to 75th percentiles. Whiskers: outliers not included. The vertical lines in the boxes represent the median values, whereas the square symbols in the boxes denote the respective mean values. Significance: **P ≤ 0.01; ***P ≤ 0.001.

- TNF does not affect FCCP‐induced translocation of Parkin to mitochondria. HeLa cells transiently expressing Parkin were treated with FCCP (10 μM) for the indicated time with or without a TNF pretreatment (25 ng/ml for 15 min). Then, the cells were fixed and analyzed by immunocytochemistry and fluorescence microscopy using Parkin and Hsp60 antibodies. Shown is the mean ± standard deviation (student's t‐test) based on three independent experiments; at least 300 cells per condition were assessed.

- Neither TNF treatment nor OTULIN silencing increases mitophagy. SH‐SY5Y cells were treated as indicated: Parkin overexpression plus FCCP 10 μM (red), FCCP 10 μM only (green), TNF 25 ng/ml (purple), or OTULIN silencing for 48 h (blue). A ratiometric analysis of fluorescence intensities was performed at the time indicated by live‐cell microscopy in cells transiently expressing mt‐mKeima. Shown are the mean normalized fluorescence intensities ± standard deviation measured every 5 min over 500 min. At least five cells were monitored for each condition.

- OTULIN does not affect CCCP‐induced translocation of Parkin to mitochondria. HeLa cells transiently expressing Parkin or Parkin and OTULIN were treated with CCCP (10 μM) for 90 min. Then, untreated and CCCP‐treated cells were fixed and analyzed by immunocytochemistry and fluorescence microscopy using Parkin and Hsp60 antibodies. Middle panel: Quantification of mitochondrial Parkin translocation. Shown is the mean ± standard deviation (student's t‐test) based on three independent experiments. Right panel: Expression controls. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- OTULIN does not affect CCCP‐induced PINK1/Parkin‐dependent mitophagy. HeLa cells transiently expressing Parkin or Parkin and OTULIN were treated with CCCP (10 μM) for 24 h. Then, the cells were fixed and analyzed by immunocytochemistry and fluorescence microscopy using Parkin and Hsp60 antibodies. Middle panel: Quantification of mitochondrial clearance. Shown is the mean ± standard deviation (student's t‐test) based on three independent experiments; at least 300 cells per condition were assessed. Right panel: Expression controls. Scale bar: 10 μm.

It has been reported previously that the mature 52‐kDa PINK1 species is stabilized by K63‐linked ubiquitination induced by NF‐κB pathway activation (Lim et al, 2015). We therefore wondered whether PINK1 is a target for linear ubiquitination. Co‐immunoprecipitation experiments indicated that PINK1 interacts with HOIP (Fig EV3A–D). To map the domains of HOIP mediating this interaction, we employed transiently transfected cells. V5‐tagged PINK1 co‐purified with full‐length HOIP and the N‐terminal part of HOIP (aa 1–697), but not with the C‐terminal part of HOIP (aa 697–1,072) (Fig EV3A and B). We then tested different HOIP constructs lacking N‐terminal domains to more precisely define the region of HOIP that mediates the interaction with PINK1. PINK1 co‐immunoprecipitated only with the 1–697 aa HOIP construct and to a lesser extent with the 1–475 aa construct, which lacks the UBA domain, suggesting that the UBA domain directly or indirectly contributes to the interaction of HOIP with PINK1 (Fig EV3C and D). Of note, immunoblotting of cellular lysates indicated that PINK1 abundance was increased in the presence of either full‐length HOIP or N‐terminal HOIP (1–697 aa), suggesting that complex formation contributes to PINK1 stabilization (Fig EV3B and D, input). In support of PINK1 interacting with endogenous HOIP, both proteins were detected in the 450–720 kDa fractions (corresponding to the size of LUBAC) upon size‐exclusion chromatography of cellular lysates (Fig EV3E). In the next step, PINK1 ubiquitination was analyzed in cells overexpressing HOIP and HOIL‐1 to increase LUBAC activity. The cells were harvested under denaturing conditions and then PINK1 was affinity‐purified by its V5 tag and subjected to immunoblotting using ubiquitin antibodies. A strong ubiquitin‐positive signal in the higher molecular range occurred upon increased expression of HOIP and HOIL‐1, which was not present in cells overexpressing OTULIN, confirming a linear ubiquitin chain topology (Fig 2D). Compared with wildtype HOIP, only a weak ubiquitin‐positive signal was seen in cells overexpressing catalytically inactive HOIP C885A (Fig 2D), which can be explained by the ability of co‐expressed HOIL‐1L to increase endogenous LUBAC activity. An in vitro ubiquitination assay using catalytically active recombinant HOIP and PINK1 immunoprecipitated from cells also supported the notion that HOIP can ubiquitinate PINK1 (Fig 2E). We then tested for ubiquitination of endogenous PINK1 after TNF treatment. PINK1 was immunoprecipitated from untreated or TNF‐treated cells and analyzed by immunoblotting using PINK1‐, M1‐ubiquitin, and p‐S65‐ubiquitin‐specific antibodies. Increased signal intensities were observed in the high molecular weight range in TNF‐treated cells, which disappeared when the cell lysates were treated with recombinant OTULIN (Fig 2F). In conclusion, TNF signaling induces recruitment of LUBAC to mitochondria, where PINK1 is stabilized by complex formation and ubiquitination.

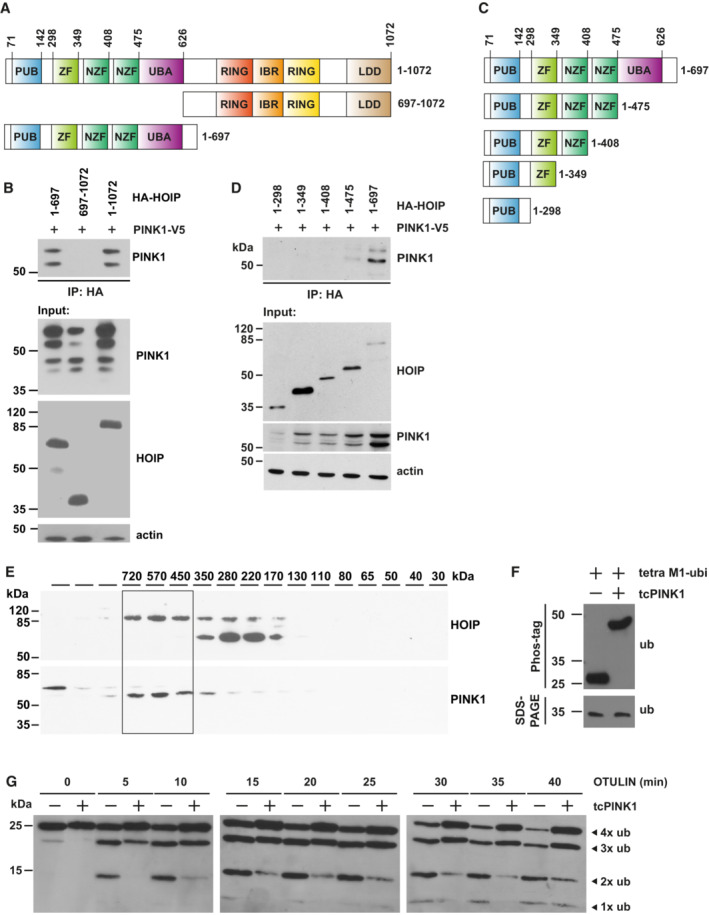

Figure EV3. PINK1 co‐immunoprecipitates with HOIP and phosphorylates M1‐linked tetra‐ubiquitin.

-

A, CSchematic representation of the HOIP constructs used to map the interaction between HOIP and PINK1. All constructs are equipped with an N‐terminal HA tag. IBR, in‐between RING domain; LDD, linear ubiquitin chain determining domain; NZF, nuclear protein localization 4‐type zinc finger domain; PUB, peptide N‐glycosidase/ubiquitin‐associated domain; RING, really interesting new gene; UBA, ubiquitin‐associated domain; ZF, zinc finger domain.

-

BPINK1 co‐immunoprecipitates with the N‐terminal part of HOIP. HEK293T cells were transfected with V5‐tagged PINK1 and the indicated HA‐tagged HOIP constructs. Twenty‐four hours after transfection cells were lysed under native conditions and subjected to immunoprecipitation using HA antibodies. Immunopurified proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting using V5 antibodies to detect PINK1.

-

DThe UBA domain enhances the interaction between HOIP and PINK1. HEK293T cells were analyzed as described in B.

-

EPINK1 co‐elutes with HOIP in cellular lysates. HEK293T cells expressing V5‐tagged PINK1 were lysed, and soluble proteins were separated by size‐exclusion chromatography. Fractions were collected and analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against HOIP and V5.

-

FPINK1 phosphorylates M1‐linked tetra‐ubiquitin in vitro. M1‐linked tetra‐ubiquitin was incubated with or without recombinant tcPINK1 in kinase buffer for 48 h. The samples were analyzed by Phos‐tag™ SDS–PAGE and immunoblotting using ubiquitin antibodies.

-

GThe efficiency of OTULIN to hydrolyze M1‐linked ubiquitin is decreased in the presence of PINK1. Recombinant M1‐linked tetra‐ubiquitin was incubated with or without recombinant Tribolium castaneum tcPINK1 for 48 h. Then, recombinant OTULIN was added for the indicated time. The reaction was stopped by adding Laemmli sample buffer and the samples were analyzed by immunoblotting using ubiquitin antibodies.

PINK1 counteracts OTULIN activity at mitochondria by phosphorylating M1‐linked ubiquitin chains

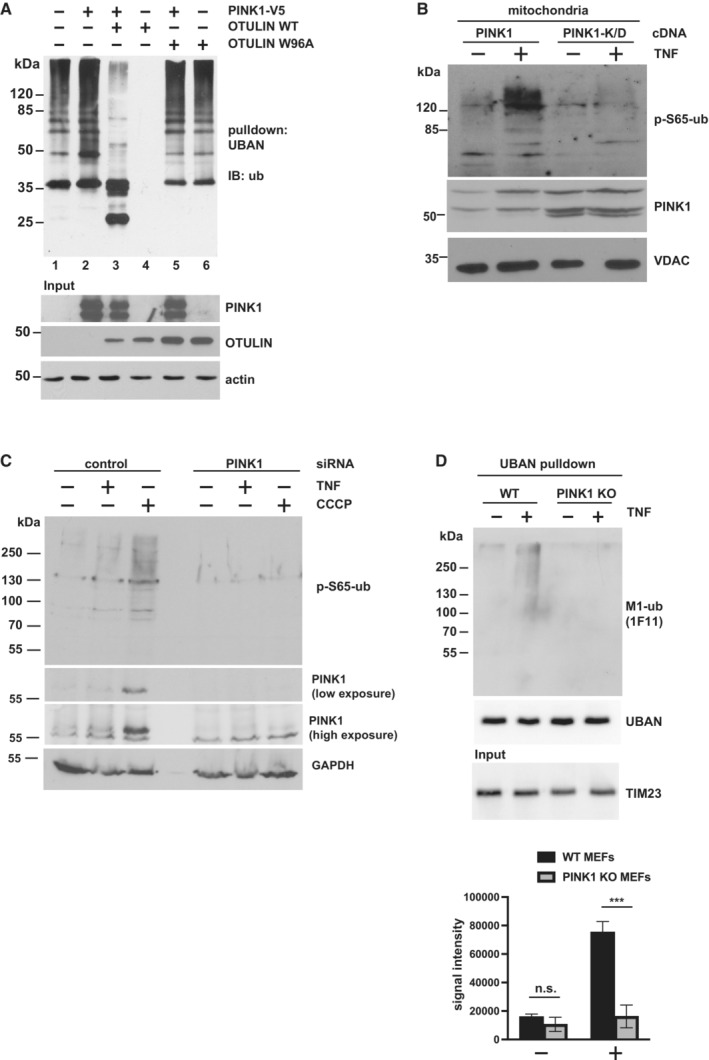

What could be the functional consequence of PINK1 stabilization at the mitochondrial outer membrane? PINK1‐mediated phosphorylation of ubiquitin alters the structure and surface properties of ubiquitin and thereby can affect the assembly and disassembly of polyubiquitin chains (Wauer et al, 2015). It has been shown previously in vitro that M1‐linked tetra‐ubiquitin is less efficiently hydrolyzed by OTULIN in the presence of PINK1 (Wauer et al, 2015). We confirmed these results (Fig EV3F and G) and tested whether PINK1 impairs OTULIN activity also in cells. Proteins modified by linear polyubiquitin chains were affinity‐purified using the recombinant UBAN domain of NEMO (Komander et al, 2009; Rahighi et al, 2009; Hadian et al, 2011; Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013), which shows a 100‐fold higher affinity for M1‐linked than for K63‐linked ubiquitin (Lo et al, 2009; Rahighi et al, 2009), and then analyzed by immunoblotting using M1‐ubiquitin‐specific antibodies. The M1‐ubiquitin‐positive signals in extracts prepared from cells overexpressing HOIP and HOIL‐1L were abolished by co‐expression of wildtype OTULIN (Fig 3A, lanes 1 and 4) but not by the inactive OTULIN variant W96A (Fig 3A, lane 6). Co‐expression of PINK1 increased M1‐ubiquitination induced by HOIP and HOIL‐1L (Fig 3A, lanes 1 and 2) and partially restored M1‐ubiquitination in cells co‐expressing wildtype OTULIN (Fig 3A, lanes 3 and 4). These results suggested that also in cells PINK1 can counteract the efficiency of OTULIN to hydrolyze M1‐linked polyubiquitin chains.

Figure 3. PINK1 stabilizes M1‐linked ubiquitin by phosphorylation and counteracts OTULIN activity.

- PINK1 antagonizes OTULIN activity in cells. HEK293T cells expressing HOIP and HOIL‐1L were transfected with PINK1, WT OTULIN, or the inactive OTULIN mutant W96A, as indicated. The cells were lysed 24 h later under denaturing conditions, and lysates were subjected to affinity purification using the Strep‐tagged UBAN domain of NEMO to enrich proteins modified with M1‐linked ubiquitin. Proteins affinity‐purified by Strep‐Tactin beads were immunoblotted against ubiquitin.

- Catalytically active PINK1 increases p‐S65‐ubiquitin at mitochondria. HEK293T cells were transfected with wildtype PINK1 or kinase‐dead (K/D) PINK1. Forty‐eight hours after transfection, the cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and lysed. Purified mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against p‐S65‐ubiquitin, PINK1, and VDAC (loading control).

- The TNF‐induced increase in p‐S65‐ubiquitin is abolished in PINK1‐deficient cells. HEK293T cells were transfected with control or PINK1‐specific siRNA and treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) or CCCP (10 μM, 90 min) 48 h after transfection. The whole cell lysates were analyzed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies.

- TNF‐induced M1‐ubiquitination is reduced in PINK1‐deficient cells. WT and PINK1‐KO MEFs were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) and then harvested. Purified mitochondrial fractions were subjected to affinity purification using the Strep‐tagged UBAN domain, as described in (A), followed by immunoblotting using M1‐ubiquitin‐specific antibodies, Strep‐Tactin conjugated to horse radish peroxidase (to control the UBAN pulldown efficiency), and TIM23 (input control). Quantification of the M1‐ubiquitin‐positive signal intensities is shown in the lower panel. Data represent the mean values with standard deviations of three independent experiments; n.s., not significant, ***P < 0.001. A two‐way ANOVA test was used to analyze statistical significance.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Prompted by these findings, we wondered whether PINK1 increases TNF‐induced M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria by phosphorylating ubiquitin. Increased expression of wildtype PINK1 but not kinase‐dead (K/D) PINK1 increased p‐S65‐ubiquitin in the mitochondrial fraction after TNF treatment (Fig 3B), whereas in cells silenced for PINK1 expression TNF did not increase p‐S65‐ubiquitin (Fig 3C). In favor of a role of PINK1 in stabilizing M1‐linked ubiquitin chains, the TNF‐induced M1‐ubiquitin‐specific signal was significantly reduced in MEFs from PINK1‐KO mice (Fig 3D).

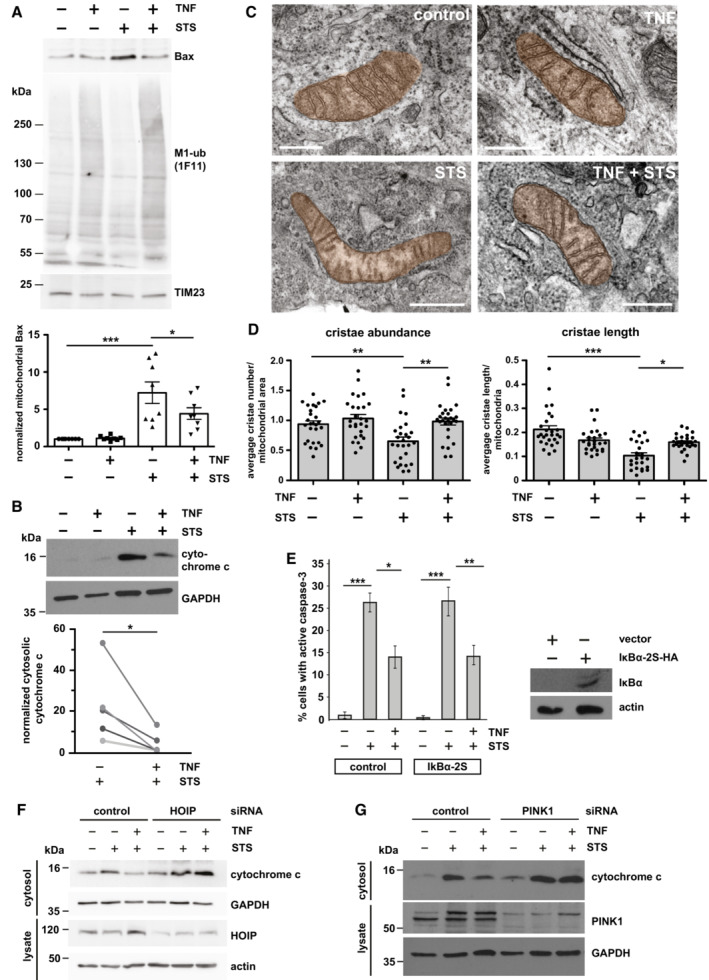

Mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination protects from apoptosis

Our data so far revealed that TNF increases M1‐linked ubiquitination at mitochondria and stabilizes PINK1 without inducing mitophagy. Based on the fact that both TNF and PINK1 have anti‐apoptotic functions, we were wondering whether M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria protects from cell death. TNF induces the increased expression of anti‐apoptotic proteins through the formation of complex I at the TNFR1 and activation of the transcription factor NF‐κB (Hayden & Ghosh, 2014; Brenner et al, 2015; Kupka et al, 2016b). We hypothesized that the fast TNF‐induced increase in mitochondrial ubiquitination protects mitochondria from apoptosis before transcriptional reprogramming by NF‐κB takes effect. To address this possibility experimentally, we exposed cells to a short proapoptotic stimulus with or without TNF pretreatment for 15 min. Apoptotic cell death was assessed by mitochondrial Bax recruitment, cytochrome c release, caspase‐3 activation, and ultrastructural analysis of cristae morphology. Bax was efficiently recruited to mitochondria within 1 h of staurosporine (STS) treatment, as detected by immunoblotting of purified mitochondria (Fig 4A). When STS was applied 15 min after TNF pretreatment, the amount of mitochondrial Bax was significantly reduced (Fig 4A). Likewise, STS‐induced cytochrome c release into the cytoplasm was decreased by the TNF pretreatment (Fig 4B). Electron microscopy revealed that TNF prevents the STS‐induced reduction in cristae abundance per mitochondrial area and cristae length per mitochondria (Fig 4C and D). Moreover, TNF significantly reduced the number of STS‐treated cells with activated caspase‐3 (Fig 4E). This effect was not compromised in the presence of the NF‐κB super‐repressor IκBα (serines 32 and 36 replaced by alanines), which blocks nuclear translocation of the NF‐κB subunit p65 and thus NF‐κB transcriptional activity (Sun et al, 1996; Appendix Fig S2A and B), indicating that the fast protective effect of TNF was not mediated by NF‐κB activation (Fig 4E). Notably, both HOIP and PINK1 were required for the protective effect of TNF pretreatment, since in cells silenced for HOIP or PINK1 expression, TNF was not able to reduce STS‐induced cytochrome c release (Fig 4F and G). We concluded that the TNF‐induced assembly of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains by HOIP and their phosphorylation by PINK1 interferes with the insertion of Bax into the outer mitochondrial membrane, thereby preventing apoptotic cell death. To check for mitochondrial fitness, we also analyzed cellular bioenergetics in response to TNF treatment and observed a transient increase in maximal respiration, spare respiratory capacity, and ATP production (Fig EV4A–C), suggesting that TNF at least transiently enhances the cellular energy metabolism.

Figure 4. M1‐ubiquitination at mitochondria protects from apoptosis.

-

ASTS‐induced mitochondrial Bax recruitment is reduced by TNF. HeLa cells were treated with STS (1 μM, 1 h) with or without a 15 min pretreatment with TNF (25 ng/ml) and then harvested. Purified mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies against Bax and M1‐ubiquitin. The input was immunoblotted for TIM23 (upper panel). Bax‐specific signal intensities were quantified and normalized to TIM23‐specific signals (lower panel). Data represent the mean with standard error of eight independent experiments. *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test, n = 8.

-

BSTS‐induced cytochrome c release is decreased by TNF. HeLa cells were treated as described in (A). The cytosolic fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using cytochrome c antibodies. GAPDH was used as a reference. Quantification of five biological replicates is shown in the lower panel. Signal intensities were quantified and normalized to that of GAPDH. *P < 0.05. Kolmogorow–Smirnov normality test, paired t‐test, two‐tailed, n = 5.

-

C, DTNF treatment prevents damage of mitochondrial cristae under proapoptotic conditions. (C) SH‐SY5Y cells were treated as described in (A), fixed and embedded and the mitochondrial ultrastructure was imaged by electron microscopy. Scale bar: 400 nm. (D) Cristae abundance (average cristae number per mitochondrial area) and cristae length (average cristae length per mitochondrium) were analyzed by Imaris 9.8. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.01. Cristae abundance: Shapiro–Wilk normality test, One‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test, n = 27. Cristae length: Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test, n = 24–27. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

-

EThe fast anti‐apoptotic effect of TNF is not affected by the NF‐κB inhibitor IκBα. SH‐SY5Y cells were transiently transfected with the NF‐κB super‐repressor IκBα‐2S or luciferase as a control. Twenty‐four hours later, the cells were treated with STS (5 μM, 2 h) with or without a 15 min pretreatment with TNF (25 ng/ml). Cells were fixed and stained by antibodies against active caspase‐3. Signal intensities were quantified by immunocytochemistry ancf IκBα‐2S was tested by immunoblotting using antibodies against the HA tag. Data represent the standard deviation of three independent experiments; at least 300 cells were counted per experiment. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01. Student's t‐test, two‐tailed, n = 3.

-

FThe protective effect of TNF is dependent on HOIP expression. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with control or HOIP siRNA. Forty‐eight hours after transfection, cells were treated with STS (1 μM, 1 h) with or without a 15 min TNF pretreatment (25 ng/ml) and then harvested. The cytosolic fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using cytochrome c antibodies. HOIP silencing efficiency was analyzed in whole cell lysates using antibodies against HOIP. GAPDH and actin were immunoblotted as input controls.

-

GThe protective effect of TNF is dependent on PINK1 expression. HeLa cells were transiently transfected with control or PINK1 siRNA and treated as described in (F). The cytosolic fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using cytochrome c and PINK1 antibodies. GAPDH was immunoblotted as input control.

Source data are available online for this figure.

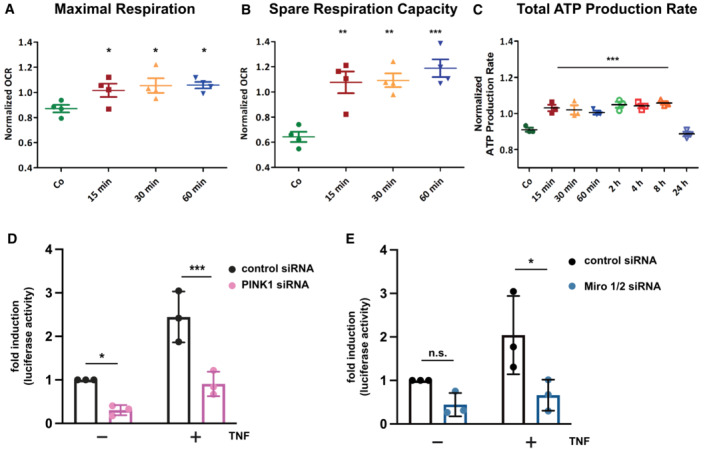

Figure EV4. TNF influences the bioenergetic profile and TNF‐induced NF‐κB transcriptional activity is impaired in PINK1‐ and Miro1/2‐deficient cells.

-

A, BTNF increases maximal respiration (A) and spare respiratory capacity (B). HeLa cells were treated with TNF for the indicated time and analyzed by the Agilent Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Test. The spare respiratory capacity is the difference between maximal and basal respiration. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, n = 4 independent experiments, bars represent mean ± SEM. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

-

CTNF increases total ATP production. HeLa cells were treated with TNF for indicated time and analyzed by the Agilent Seahorse ATP Rate Assay. One‐way ANOVA with Tukey's multiple comparisons test, n = 3 independent experiments, bars represent mean ± SEM. ***P < 0.001.

-

DPINK1 silencing decreases NF‐κB transcriptional activity. Hela cells were treated with PINK1‐specific or control siRNA. The next day, cells were transfected with an NF‐κB luciferase reporter construct. Twenty‐four hours after transfection, cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 3 h) harvesting. Luciferase activity was quantified in cell lysates with luciferase activity in untreated control cells set to 1. Data represent the mean with standard deviation. Sidak's multiple comparisons test, n = 3 independent experiments, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001.

-

EMiro1/2 silencing decreases NF‐κB transcriptional activity. Hela cells were treated with Miro 1/2‐specific or control siRNA. The next day, cells were transfected with an NF‐κB luciferase reporter construct and analyzed as described in (A). Data represent the mean with standard deviation. Sidak's multiple comparisons test, n = 3 independent experiments, n.s., not significant, *P < 0.05.

A signaling platform for TNF‐induced NF‐κB activation is assembled at mitochondria

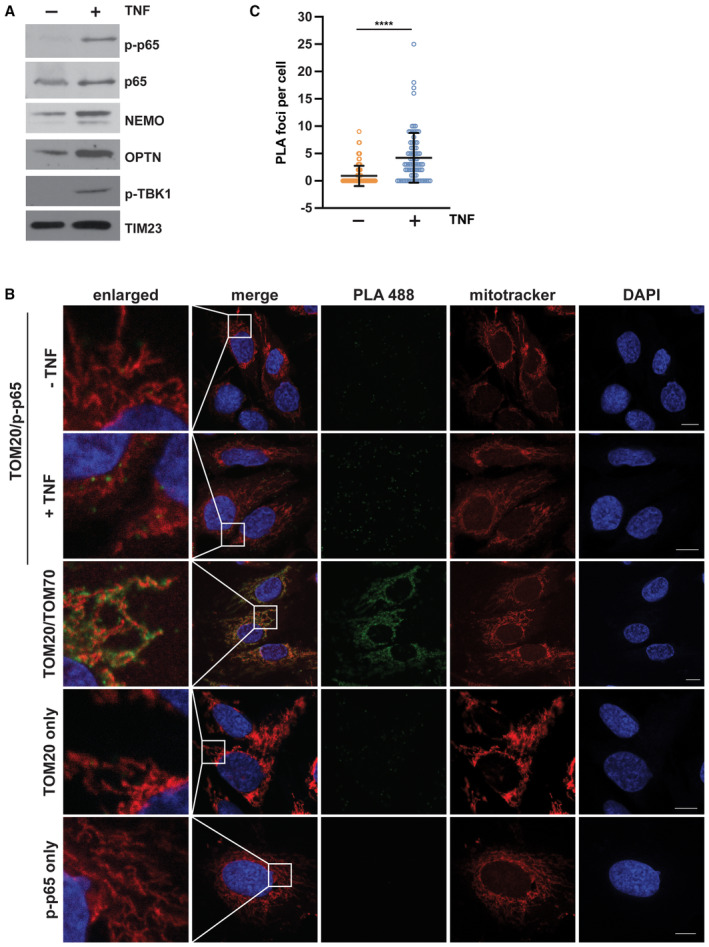

Why is mitochondrial fitness and protection fostered in the early phases of TNF signaling? Though the fast TNF‐mediated protection of mitochondria from apoptosis was NF‐κB‐independent, we observed an increased abundance of NEMO, p65, and phosphorylated p65 (p65) at mitochondria after 15 min TNF treatment (Fig 5A). We therefore speculated that mitochondrial M1‐ubiquitination contributes to TNF signal amplification and facilitates transmission of the signal to the nucleus. To confirm our data based on mitochondrial purification and immunoblotting, we performed a proximity ligation assay (PLA). In situ PLA using anti‐TOM20 and anti‐phospho‐S536‐p65 (p‐p65) antibodies revealed the presence of p‐p65 at mitochondria and an increased abundance upon TNF treatment (Fig 5B and C).

Figure 5. Mitochondria serve as a signaling platform for TNF‐induced NF‐κB activation.

-

ANF‐κB signaling components are recruited to mitochondria upon TNF treatment. (A) HEK293T cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min), harvested and purified mitochondrial fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using the antibodies indicated; p‐p65: phospho‐S536‐p65; p‐TBK1: phospho‐S172‐TBK1.

-

BPhosphorylated p65 is in close proximity to TOM20 in response to TNF treatment. Representative immunofluorescence images of SH‐SY5Y cells using the proximity ligation assay (PLA) between phospho‐S536‐p65 (rabbit) and TOM20 (mouse) coupled antibodies. One set of cells was treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min) before fixation. Nuclei were stained with DAPI, mitochondria were stained with MitoTracker™ Red CMXRos (red), and the PLA amplification reaction was visualized by green foci. As a positive control, fixed cells were incubated with primary TOM20 (mouse) and TOM70 (rabbit) antibodies and subjected to the PLA assay. As negative controls, fixed cells were incubated with either TOM20 or p‐p65 antibodies prior to the PLA assay. Scale bar, 10 μm.

-

CQuantification of the phospho‐S536‐p65/TOM20 PLA foci per cell. Data represent the number of PLA foci per cell (mean ± SD); at least 84 cells in total were analyzed per condition. ****P < 0.0001. A two‐tailed nonparametric Mann–Whitney test was used to analyze statistical significance.

Source data are available online for this figure.

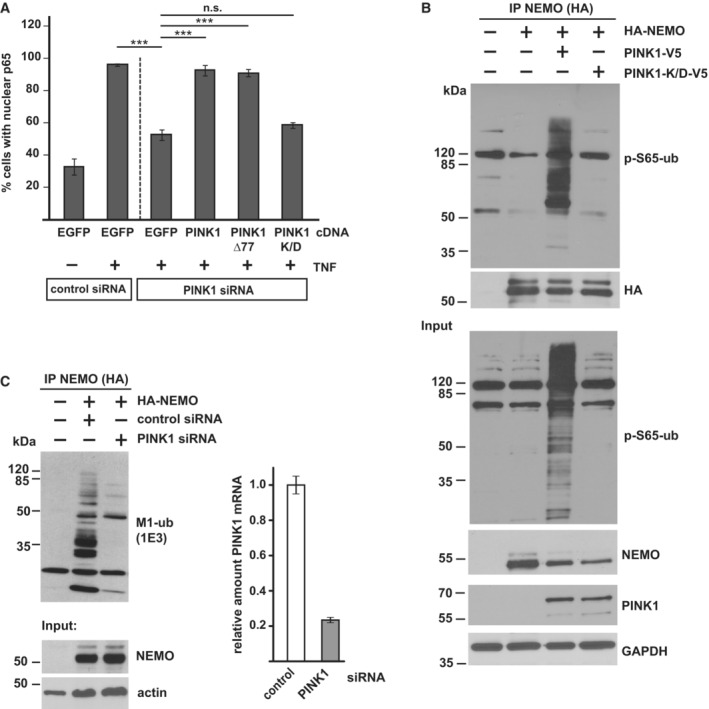

Next, we tested whether PINK1 has a role in mitochondrial NF‐κB pathway activation. TNF‐induced nuclear translocation of p65 was significantly decreased in cells silenced for PINK1 expression. This phenotype was rescued by wildtype PINK1 but not by the catalytically inactive PINK1‐K/D mutant (Fig 6A). Moreover, luciferase reporter assays indicated that basal and TNF‐induced NF‐κB‐dependent transcription is reduced in cells silenced for PINK1 expression (Fig EV4D), in line with earlier findings (Sha et al, 2010). NEMO is a highly relevant substrate of HOIP in NF‐κB pathway activation, and we and others previously found that Parkin modifies NEMO with K63‐linked ubiquitin chains (Henn et al, 2007; Sha et al, 2010; Van Humbeeck et al, 2011; Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013). We therefore explored the possibility that PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitinated NEMO. In cells expressing wildtype PINK1, the p‐S65‐ubiquitin signal was strongly enhanced on NEMO affinity‐purified from cell lysates, whereas no signal was seen when catalytically inactive PINK1‐K/D was expressed (Fig 6B). Supporting the physiological relevance of endogenous PINK1, TNF‐induced M1‐ubiquitination of NEMO was reduced in PINK1‐deficient cells (Fig 6C). Taken together, catalytically active PINK1 promotes NF‐κB activation, most likely by stabilizing M1‐linked ubiquitin chains on LUBAC substrates, such as NEMO, through phosphorylation.

Figure 6. PINK1 promotes NF‐κB activation and modulates NEMO ubiquitination.

- Nuclear translocation of p65 is impaired in cells silenced for PINK1 expression. SH‐SY5Y cells were transfected with control or PINK1‐specific siRNAs. For rescue experiments, cells were co‐transfected with wildtype PINK1, PINK1Δ77, or kinase‐dead PINK1‐K/D. Two days after transfection the cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 25 min), fixed, and stained with p65 antibodies. The fraction of cells showing nuclear translocation of p65 was determined for each condition. Data represent the mean ± SEM of three independent experiments. The experiment was performed in triplicates and more than 300 cells were quantified per experiment and condition. ***P < 0.001, Student's t‐test, two‐tailed, n = 3.

- PINK1 phosphorylates ubiquitinated NEMO. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with V5‐tagged wildtype PINK1 or kinase‐dead PINK1‐K/D and HA‐tagged NEMO. One day after transfection the cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies against HA. Precipitated proteins were then detected by immunoblotting using p‐S65‐ubiquitin antibodies. The input was immunoblotted for NEMO, PINK1, p‐S65‐ubiquitin, and GAPDH.

- Linear ubiquitination of NEMO is reduced in PINK1‐deficient cells. HEK293T cells were co‐transfected with HA‐NEMO and control or PINK1‐specific siRNAs. Forty‐eight hours after transfection the cells were lysed and subjected to immunoprecipitation using antibodies against HA. Precipitated proteins were then detected by immunoblotting using M1‐ubiquitin antibodies. The input was immunoblotted for NEMO and actin. PINK1 silencing efficiency was determined by real‐time RT–PCR. Bars represent mean ± SD with three technical replicates.

Source data are available online for this figure.

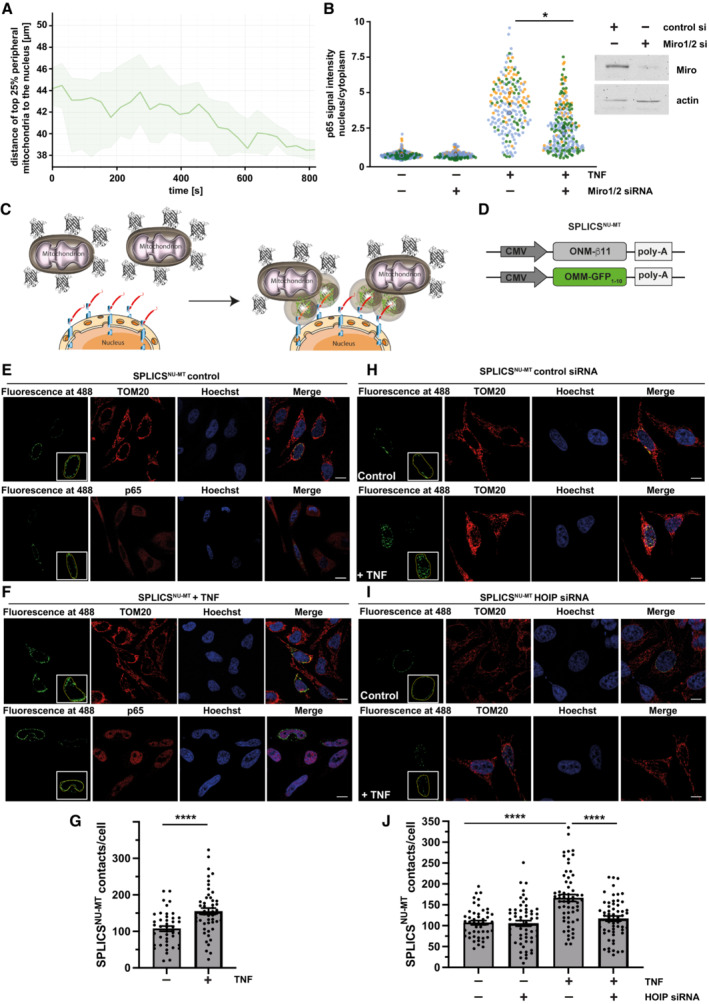

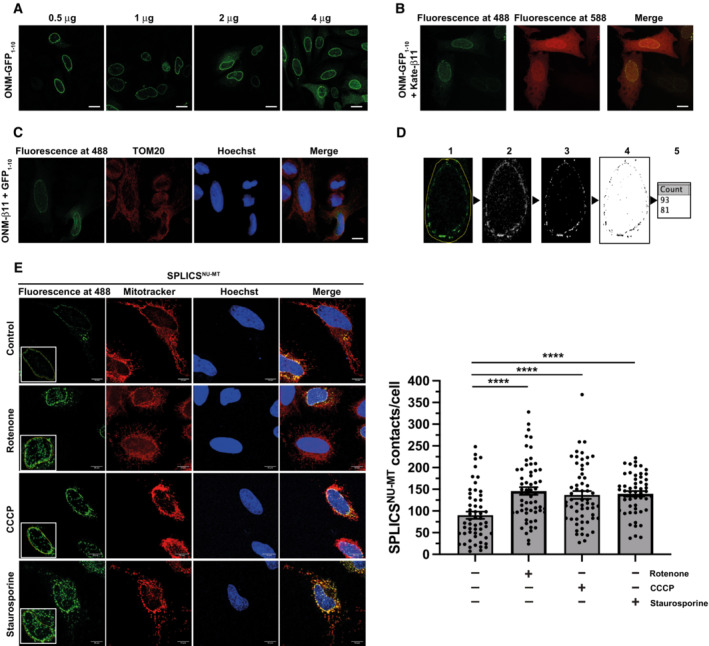

TNF promotes transport of p65 to the nucleus and increases mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites

What could be the advantage of assembling a signaling platform at mitochondria? First, the mitochondrial network provides a large surface area for signal amplification. Second and possibly even more relevant, mitochondria are highly dynamic and mobile organelles that engage in physical and functional interactions with other organelles and the plasma membrane (Scorrano et al, 2019; Giacomello et al, 2020; Harper et al, 2020; Prinz et al, 2020). We therefore wondered whether mitochondria facilitate the transport of activated NF‐κB components to the nucleus. First, we followed up on the motility of mitochondria in SH‐SY5Y cells upon TNF stimulation by life cell imaging and observed a decrease in the distance between peripheral mitochondria and the nucleus within 15 min of TNF treatment (Fig 7A; Movie EV1). Encouraged by this observation, we tested whether mitochondrial motility affects the nuclear translocation of p65 upon TNF stimulation. We silenced the expression of the mitochondrial outer membrane Rho GTPases Miro1 and Miro2, which are components of the adaptor complex that anchors mitochondria to motor proteins (Schwarz, 2013; Misgeld & Schwarz, 2017). A ratiometric analysis revealed a significant decrease in the fraction of nuclear p65 upon TNF stimulation in Miro1/2‐deficient cells (Fig 7B). Accordingly, NF‐κB‐dependent transcription was decreased in cells silenced for Miro1 and Miro 2 expression (Fig EV4E). We then reasoned that mitochondrial transport of p65 to the nucleus should increase the proximity between mitochondria and the nucleus and possibly favor the formation of mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites. To this end, we have generated a new genetically encoded split‐GFP contact site sensor (SPLICS) (Cieri et al, 2018; Vallese et al, 2020; Cali & Brini, 2021), capable to reconstitute fluorescence only when the nucleus and mitochondria are in close proximity (Fig 7C). Correct targeting and self‐complementation ability of the GFP1‐10 and the β11 split‐GFP fragments to the outer nuclear membrane (ONM) were tested (Fig EV5A–C). The ONM‐β11 was further selected to generate the SPLICSNU‐MT reporter along with the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM)‐targeted GFP1‐10, which has been extensively used in all mitochondrial sensors generated so far (Fig 7D; Cieri et al, 2018; Vallese et al, 2020). Expression of the SPLICSNU‐MT reporter in HeLa cells resulted in the emission of a fluorescent punctate signal within the nuclear/perinuclear region that could be easily quantified with the Fiji (https://imagej.net/software/fiji/) software, and custom macros written for interorganellar contact analysis (Cali & Brini, 2021), with an additional ROI traced around the nucleus of SPLICSNU‐MT‐positive cells to specifically focus only contacts that involve the nuclear envelope (Fig EV5D). To validate the ability of the SPLICSNU‐MT reporter to detect changes in the mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites, we triggered the mitochondrial retrograde response (MRR) in HeLa cells (Amuthan et al, 2001; Eisenberg‐Bord & Schuldiner, 2017; Desai et al, 2020; Walker & Moraes, 2022). A significant increase in the formation of nucleus‐mitochondria contact sites upon MRR activation was observed by employing the SPLICSNU‐MT reporter (Fig EV5E). With this new tool, we assessed whether mitochondrial transport of p65 to the nucleus favors the proximity between mitochondria and the nucleus in TNF‐treated SPLICSNU‐MT‐expressing cells. Indeed, the number of mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites strongly increased upon TNF stimulation (Fig 7E–G). Remarkably, HOIP silencing by siRNA completely abolished the TNF‐induced increase in mitochondria‐nucleus contacts (Fig 7H–J). Thus, different experimental approaches supported the notion that mitochondria are implicated in targeting activated NF‐κB to the nucleus upon TNF stimulation and that this process is dependent on linear ubiquitination.

Figure 7. Mitochondria facilitate the transfer of p65 to the nucleus.

-

ATNF induces the movement of peripheral mitochondria toward the nucleus. Primary macrophages were stained by Mitotracker™ Green to visualize mitochondria and by Hoechst 33342 to visualize the nucleus and monitored every 30 s for 15 min after treatment with TNF (25 ng/ml). The motility of mitochondria was analyzed using Imaris 9.8 spot function. The graphical representation of the top 25% peripheral mitochondrial indicates a decrease in the average mitochondrial distance to the nucleus after TNF treatment. Exemplified dataset shows the median distance with the upper and lower quartile (shaded area) of n = 105–187 mitochondrial spots per time point.

-

BNuclear p65 translocation upon TNF treatment is reduced cells silenced for Miro1/2 expression. HeLa cells were transfected with control or Miro1 and Miro2 siRNAs. 48 h later, cells were treated with TNF (25 ng/ml, 15 min), fixed, and stained using antibodies against p65 and tubulin and DAPI. Images were segmented in a cytoplasmic and nuclear compartment and the fluorescence signal intensity ratio of p65 was measured using CellProfiler 4.2.1. Quantification is based on three biological replicates. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test, n = 79–157, *P < 0.05.

-

CCartoon of newly developed SPLICS reporter to detect mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites. Fluorescence reconstitution between the ONM‐targeted β11 and the OMM‐targeted GFP1‐10 fragment occurs at the contact site.

-

DScheme of the plasmids encoding the SPLICSNU‐MT reporter.

-

E–GTNF increases mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites. Representative immunofluorescence images (E, F) and quantification (G) of mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites in HeLa cells transfected with the SPLICSNU‐MT and treated with 25 ng/ml TNF or PBS for 15 min. TOM20 antibodies were used to stain mitochondria and p65 antibodies to assess p65 nuclear translocation. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (ThermoFisher, 1 μg/ml). Unpaired two‐tailed t‐test, n = 43 (control) or 51 (TNF), Bars represent mean ± SEM. ****P < 0.0001. Scale bar: 10 μm.

-

H–JTNF increases mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites in a HOIP‐dependent manner. Representative immunofluorescence images (H, I) and quantification (J) of mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites in control or HOIP‐silenced (HOIP siRNA) HeLa cells transfected with the SPLICSNU‐MT probe treated with 25 ng/ml TNF or PBS for 15 min. Mitochondria and nuclei were stained as described in (E) and (F). Two‐way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple comparison test, n = 34–44 from three independent experiments, Bar represents mean ± SEM. ****P < 0.0001. Scale bar: 10 μm.

Source data are available online for this figure.

Figure EV5. Targeting, self‐complementation, and ability to respond to the MRR activation of the SPLICSNU‐MT reporters.

- Assessment of the nuclear envelope localization of the ONM‐targeted GFP1‐10 fragment at different plasmid concentrations transfected into HeLa cells. The GFP1‐10 fragment was stained with a mouse anti‐GFP primary antibody (Santa Cruz, 1:100) followed by an anti‐mouse AlexaFluor 488‐conjugated secondary antibody (ThermoFisher, 1:100). Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Assessment of the self‐complementation capability of the ONM‐targeted GFP1‐10 fragment with a cytosolic mKate‐tagged β11. Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Nuclear envelope localization and self‐complementation of the ONM‐targeted β11 fragment co‐transfected with an untargeted, cytosolic GFP1‐10 fragment. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst33342 (ThermoFisher, 1 μg/ml). Scale bar: 10 μm.

- Schematic representation of the contact quantification process using ImageJ plugin VolumeJ and custom‐made macros specifically developed for the analysis: (1) an ROI is traced around the nucleus of the cell; (2) the first macro is applied, which clears all the signal outside the ROI and convolves the signal inside; (3) VolumeJ is used to generate a rendering of the convolved signal; (4) the second custom macro is applied on the first and the last frame of the rendering; (5) the contacts per each frame are quantified and the overall number of contacts per cell is calculated by averaging the two results.

- Representative images and contact site quantification of HeLa cells after induction of the mitochondrial retrograde response (MRR) upon treatment with rotenone (5 μM for 3 h), CCCP (10 μM for 3 h) or staurosporine (1 μM for 2 h). Mitochondria were stained with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (ThermoFisher, 100 nM) in HBSS for 30 min. Nuclei were stained as described in (C). Scale bar: 10 μm. Kruskal–Wallis test followed by Dunn's multiple comparison test, n = 54–60 from three independent experiments, ****P < 0.0001. Bars represent mean ± SEM.

Discussion

We identified a mitochondrial signaling platform for NF‐κB pathway activation that is shaped by LUBAC‐mediated linear ubiquitination. This mitochondrial platform shares some features with a signaling platform that is assembled at cytosol‐invading bacteria, such as Salmonella species, to restrict bacterial proliferation. Ubiquitination of the bacterial outer membrane component lipopolysaccharide (LPS) by the RNF213 ubiquitin ligase and subsequent binding of LUBAC to pre‐existing ubiquitin results in the assembly of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains and the recruitment of the M1‐ubiquitin‐binding proteins NEMO and Optineurin to the bacterial surface (Noad et al, 2017; van Wijk et al, 2017; Otten et al, 2021). NEMO induces local activation of NF‐κB signaling, whereas Optineurin as a selective autophagy receptor promotes the autophagic clearance of bacteria. Similarly to the bacterial NF‐κB signaling platform, we observed recruitment of LUBAC, formation of OTULIN‐sensitive M1‐linked ubiquitin chains, and binding and activation of NF‐κB signaling components at the outer mitochondrial membrane. In contrast to the bacterial ubiquitin coat, enrichment of linear ubiquitin chains at mitochondria does not induce their autophagic clearance.

The formation of mitochondrial signaling platforms has been implicated in various signaling paradigms. However, many aspects of why cells employ mitochondria as signaling organelles are still unknown. One obvious advantage is that the integration of mitochondria in signaling pathways facilitates context‐dependent adaptive responses to bioenergetic or biosynthetic demands. Another plausible explanation is that several signaling pathways affect cell fate decisions, which are regulated by mitochondria. Our study revealed two other advantages of mitochondrial signaling platforms. Mitochondria can contribute to signal amplification by virtue of their large surface and the presence of signaling components that stabilize “signals” by forming protein complexes (signalosomes) and/or by posttranslational modifications of signaling components. In TNF signaling, the mitochondrial kinase PINK1 performs such a function. It increases the stability of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains assembled by HOIP by antagonizing the M1‐ubiquitin‐specific deubiquitinase OTULIN, thus enhancing downstream signaling. Moreover, mitochondria are highly dynamic and mobile organelles, allowing them to communicate and interact with various cellular components and organelles. Here we present evidence that mitochondria can act as vehicles to shuttle activated transcription factors to the nucleus. This mode of transport may be particularly relevant to polarized cells, such as neurons. In support of this notion, NF‐κB signaling components are present at synapses and concentrated at postsynaptic densities together with mitochondria, where neuronal activity‐dependent retrograde transport of the NF‐κB subunit p65 serves as a synapse‐to‐nucleus signal transducer (Mikenberg et al, 2007; Shrum et al, 2009). In our study, nuclear translocation of the NF‐κB subunit p65 upon TNF stimulation was decreased in cells silenced for Miro1 and Miro2 expression. Even more striking, we found that TNF increases mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites, which presumably facilitate the uptake of p65 into the nuclear compartment. In support of this notion, the expression level of a mitochondria‐nucleus tether component identified in breast cancer cells, the mitochondrial translocator protein TSPO, correlated with the abundance of nuclear NF‐κB (Desai et al, 2020). TNF‐induced formation of mitochondria‐nucleus contact sites was dependent on HOIP, confirming a role of M1‐linked ubiquitination. In a recent study performed in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, TOM70 has been implicated in the formation of tethers between mitochondria and the nucleus (Eisenberg‐Bord et al, 2021). TOM70 has also been identified as a target for ubiquitination within the TNF signaling network (Wagner et al, 2016) and was detected as an OTULIN‐interacting protein in our mass spectrometry‐based screen. In addition, TOM70 is required for the activation of IRF3 in MAVS signaling (Liu et al, 2010; Thorne et al, 2022). Hence, it will be interesting to explore the possible role of TOM70 in the NF‐κB pathway.

TNF signaling usually mounts an anti‐apoptotic response via the TNFR1/complex I/NF‐κB axis, implicating transcriptional regulation of anti‐ and proapoptotic gene expression (Varfolomeev & Vucic, 2018). We previously identified the mitochondrial GTPase OPA1 as an NF‐κB target gene, which contributes to anti‐apoptotic reprogramming by maintaining cristae integrity (Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013). Here we identified a fast, transcription‐independent anti‐apoptotic TNF response that protects mitochondria by remodeling the outer mitochondrial membrane. This remodeling involves the assembly of M1‐ and K63‐linked ubiquitin chains and the recruitment of ubiquitin‐binding proteins and signaling components to the outer mitochondrial membrane, which obviously impedes Bax insertion into the outer membrane under proapoptotic conditions. Conceptually, this early TNF response ensures mitochondrial integrity and fitness to fulfill their role in signal amplification and transport of activated NF‐κB to the nucleus. Along this line, maximal respiration and spare respiratory capacity were increased by TNF treatment.

Finally, our study unveiled a mitophagy‐independent function of PINK1 in mitochondrial signaling. Previous studies already provided evidence for a role of PINK1 in NF‐κB signaling. PINK1 was shown to increase Parkin‐mediated K63‐linked ubiquitination of NEMO in vitro and in cellular models and to increase TNF‐ and IL1‐induced transcriptional activity of NF‐κB (Sha et al, 2010; Akundi et al, 2011; Lee et al, 2012; Lee & Chung, 2012). Moreover, cytosolic PINK1 is stabilized by K63‐linked ubiquitination in response to NF‐κB pathway activation (Lim et al, 2015). In contrast to mitophagy‐inducing conditions, PINK1 is stabilized in TNF signaling without dissipation of the mitochondrial membrane potential. Accordingly, proteolytically processed, mature PINK1 is stabilized in addition to full‐length PINK1 destined for import through the TOM/TIM23 complexes. Albeit the accumulation of the mature PINK1 species after 15 min, TNF treatment is less striking than that of unprocessed PINK1 after 90 min CCCP treatment, several lines of evidence point toward a physiological role of PINK1 in NF‐κB signaling. First, PINK1 phosphorylates M1‐linked ubiquitin chains and thereby decreases the efficiency of OTULIN to hydrolyze linear ubiquitin chains. This explains why TNF‐induced M1‐ubiquitination is decreased in PINK1‐deficient cells. Second, the fast anti‐apoptotic TNF response depends on both HOIP and PINK1 expression. PINK1 is stabilized by complex formation with HOIP and HOIP‐dependent linear ubiquitination and in turn augments M1‐ubiquitination by antagonizing the disassembly of M1‐linked ubiquitin chains. This scenario is reminiscent of the feed‐forward activation loop in PINK1/Parkin‐dependent mitophagy and completes the picture of a mitophagy‐independent function of PINK1 and Parkin under physiological conditions that integrate their roles in innate immune signaling and stress protection.

Materials and Methods

Reagents and Tools table

| Reagent or resource | Source | Identifier |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐cleaved caspase‐3 | Cell Siganaling Technology | Cat#9664S |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐GAPDH | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat#AM4300, RRID: AB_2536381 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐HA | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat#H6908, RRID: AB_260070 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐HA | Covance Research Products Inc | Cat#NMS‐101R, RIDD: N/A |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐HA | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#3724, RRID: AB_1549585 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐HOIP (RNF31) | Bethyl | Cat#A303‐560A, RRID: AB_10949139 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐M1‐ubiquitin (clone 1E3) | Millipore | Cat#MABS199, RRID: AB_2576212 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐NEMO | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc‐8032, RRID: AB_627786 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐OTULIN | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#14127, RRID: AB_2576213 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐IKKβ | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2370, RRID: AB_2122154 |

| Human polyclonal anti‐M1‐ubiquitin (clone 1F11/3F5/Y102L) | Genentech | 1F11/3F5/Y102L |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐TNFR1 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc‐8436, RRID:AB_628377 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐TIM23 | BD Science | Cat#611222, RRID:AB_398755 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐K63‐ubiquitin | Millipore | Cat#05‐1308, RRID:AB_1587580 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐K48‐ubiquitin | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#8081, RRID:AB_10859893 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐HOIL‐1L (RBCK) | Invitrogen | Cat#PA5‐11949, RRID: AB_2175271 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐SHARPIN | Cell signaling Technology | Cat#12541, RRID: AB_2797949 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐Actin | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat#A5316, RRID:AB_476743 |

| Goat polyclonal anti‐HSP60 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc‐1052, RRID:AB_631683 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐VDAC | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#4866, RRID:AB_2272627 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐PINK1 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#6946, RRID:AB_11179069 |

| Mouse polyclonal anti‐PINK1 | Santa Cruz | Cat#sc‐517353 RRID: N/A |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐V5 | Invitrogen | Cat# R960‐25, RRID:AB_2556564 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐ubiquitin | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc‐8017, RRID:AB_628423 |

| Rabbit anti‐p‐S65‐ubiquitin | Fiesel et al (2015) | N/A |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐Bax | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat#2772, RRID:AB_10695870 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐cytochrome c | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 4280, RRID:AB_10695410 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐NF‐κB p65 | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 8242, RRID:AB_10859369 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐phospho‐NF‐κB p65 (S536) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 3033, RRID:AB_331284 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐IKBKG (NEMO) | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat# HPA000426, RRID:AB_1851572 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐Optineurin (OPTN) | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat# HPA003279, RRID:AB_1079527 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐Miro2 | Proteintech | Cat# 11237‐1‐AP RRID: AB_2179539 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐phospho TBK1/NAK (Ser172) | Cell Signaling Technology | Cat# 5483, RRID: AB_2798527 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti‐TOM20 | Santa Cruz | Cat# sc‐17764, RRID: AB_628381 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti‐TOM70 | Proteintech | Cat# 14528‐1‐AP, RRID: AB_2303727 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti‐phospho‐NF‐κB p65 (Ser536) | ThermoFisher | Cat# MA5‐15160 RRID: AB_10983078 |

| Rabbit anti‐p‐S65‐Parkin | Kane et al (2014) | |

| Strep‐Tactin® HRP conjugate | IBA Lifesciences | Cat# 2‐1502‐001 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells | DRK‐Blutspendedienst Baden‐Württemberg—Hessen, Institut für Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhämatologie, Frankfurt, Germany | https://www.blutspende.de |

| Human serum | DRK‐Blutspendedienst Baden‐Württemberg—Hessen | https://www.blutspende.de |

| Chemical, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Human TNF | Peprotech | Cat# 300‐01A |

| Murine TNF | Peprotech | Cat# 315‐01A |

| Staurosporine | Enzo life science | Cat# ALX 380‐014M001 |

| Carbonyl cyanide 3‐chlorophenylhydrazone | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat# C2759 |

| Antimycin A | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat# A8674 |

| Oligomycin | Sigma‐Aldrich | Cat# O4876 |

| Tetra‐ubiquitin (linear) | Enzo Life Sciences | Cat# BML‐UW0785‐0100 |

| Recombinant human ubiquitin | Biotechne | Cat# U‐100H‐10M |

| Cell lines | ||

| SH‐SY5Y | Leibniz‐Institut DSMZ‐Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH https://www.dsmz.de/home.html | DSMZ no.: ACC 209 |

| HEK293T | ATCC https://www.lgcstandards‐atcc.org/ | ATCC® CRL‐1573™ |

| HAP1 WT and HAP1 HOIP (RNF31) KO | Horizon | https://www.horizondiscovery.com |

| HeLa | Leibniz‐Institut DSMZ‐Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen und Zellkulturen GmbH https://www.dsmz.de/home.html | DSMZ no.: ACC 57 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

OTULIN siRNA human: GGAAGAAUGAGGACCUGGUUGAUAA GCGGAGGAAUAUAGCCUCUAUGAAG UCUCCAAGUACAACACGGAAGAAUU |

Invitrogen |

HSS131920 HSS131921 HSS131922 |

|

HOIP siRNA human: GGUACUGGCGUGGUGUCAAGUUUAA, GAGAUGUGCUGCGAUUAUAUGGCUA, CACCACCCUCGAGACUGCCUCUUCU |

Invitrogen |

HSS123836 HSS123837 HSS182838 |

|

PINK1 siRNA human: GGACGCUGUUCCUCGUUAUGAAGAA GGAGUAUCUGAUAGGGCAGUCCAUU GAGUAGCCGCAAAUGUGCUUCAUCU |

Invitrogen |

HSS127945 HSS127946 HSS185707 |

| RHOT1 siRNA human | GE Dharmacon | Cat# L‐010365‐01‐0005, smartpool |

| RHOT2 siRNA human | GE Dharmacon | Cat# L‐008340‐01‐0005, smartpool |

|

PINK1‐V5_K219A forward: 5′‐ CCCTTGGCCATCGCGATGATGTGGAACATCTCG‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1‐V5_K219A reverse: 5′‐ CGDGATGTTCCACATCATCGCGATGGCCAAGGG‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1‐V5 D362A forward: 5′‐ GGCATCGCGCACAGAGCCCTGAAATCCGAC‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1‐V5 D362A reverse: 5′‐ GTCGGATTTCAGGGCTCTGTGCGCGATGCC‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1‐V5 D384A forward: 5′‐ CTGGTGATCGCAGCTTTTGGCTGCTGCTG‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1‐V5 D384A reverse: 5′‐ CAGGCAGCAGCCAAAAGCTGCGATCACCG‐3′ |

This paper | N/A |

|

actin_forward: 5′‐ CCTGCCACCCAGCACAAT‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

actin_reverse: 5′‐ GGGCCGGACTCGTCATAC‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1 human forward: 5′‐ GTGGAACATCTCGGCAGGT‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

PINK1 human reverse: 5′‐ TTGCTTGGGACCTCTCTTGG‐3’ |

This paper | N/A |

|

Itprip HindIII‐FF: 5’‐TTTAGTAAGCTTATGGCCATGGGGCTCTTCCGC‐3‘ |

This paper | N/A |

|

RV Itprip XbaI Rev: 5’‐AGTGCTTCTAGAGCTTTTTGGGGTAGGCTGGTC‐3 |

This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pET47b HOIP‐RBR‐LDD (C‐terminal HOIP) | Stieglitz et al (2012) | N/A |

| pGEXP 6P1 tcPINK1 WT (a.a. 121–570) | Rasool et al (2018) | N/A |

| pET28a LIC UBE2L3 | Stieglitz et al (2012) | N/A |

| pcDNA6A PINK1‐V5 | Exner et al (2007) | N/A |

| pcDNA6A PINK1‐V5 kinase dead (K219A, D362A, D384A) | This paper | N/A |

| pcDNA6A PINK1 Δ77 | This paper | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐HOIP | Muller‐Rischart et al (2013) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (697–1,072) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (1–697) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (1–475) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (1–408) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (1–349) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐ (1–298) HOIP | Meschede et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 OTULIN WT | Stangl et al (2019) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 OTULIN W96A | Stangl et al (2019) | N/A |

| NF‐κB luciferase | Krappmann et al (2001) | N/A |

| pcDNA3.1 HA‐NEMO | This paper | N/A |

| pASK IBA 3+ Strep‐OTULIN | This paper | N/A |

| pET28b His‐mouseUBE1 | Addgene | #32534 |

| OMM‐GFP1‐10, GFP1‐10, RFP‐b11 | Cieri et al (2018), Vallese et al (2020) | N/A |

| pcDNA3 ONM‐β11 | This paper | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Duolink® In Situ PLA® Probe Anti‐Rabbit PLUS | Sigma‐Aldrich | #DUO92002 |

| Duolink® In Situ PLA® Probe Anti‐Mouse MINUS | Sigma‐Aldrich | #DUO92004 |

| Duolink® In Situ Detection Reagents Green | Sigma‐Aldrich | #DUO92014 |

| Duolink® In Situ Mounting Medium with DAPI | Sigma‐Aldrich | #DUO82040 |

| Seahorse XF Cell Mito Stress Kit | Agilent | #103015‐100 |

| Seahorse XF Real‐Time ATP Rate Assay Kit | Agilent | #1035292‐100 |

Methods and Protocols

DNA constructs

The wildtype PINK1‐V5 construct was described previously (Exner et al, 2007). It was generated by cloning the human PINK1 cDNA into the pcDNA6 vector via NheI and XhoI. For cloning of the kinase dead PINK1‐V5 mutant (K219A, D362A, D384A), the construct was modified by point mutations by using the indicated primers. For cloning of the PINK1‐Δ77‐V5 mutant, the PINK1 sequence 78–581 was cloned into pcDNA6 vector. Wildtype human HOIP, HOIL‐1L, and SHARPIN were described previously (Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013). HA‐HOIP 1–697 was generated using the indicated primers and then incorporated into pcDNA 3.1‐N‐HA via EcoRI and XbaI. HA‐HOIP ΔNZF1, HA‐HOIP ΔNZF2, HA‐HOIP ΔNZF1 + 2, HA‐HOIP ΔUBA, and HA‐HOIP ΔPUB were generated by overlap extension PCR (van Well et al, 2019; Meschede et al, 2020). The amplified fragments were generated using the primers indicated in the Materials section. The ONM‐β11 construct has been amplified by PCR from the template pLV‐EF1a‐Itprip‐V5 (Addgene plasmid #120241; http://n2t.net/addgene:120241; RRID:Addgene_120241) by using the following primers: Itprip HindIII‐FF and RV Itprip XbaI Rev and cloned in pcDNA3 vector containing the short‐β11 strand. The OMM‐GFP1‐10 construct, the GFP1‐10 construct, and the RFP‐β11 construct have been described previously (Cieri et al, 2018, Vallese et al, 2020).

Cell culture

HEK293T, HeLa cells, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs)

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 100 IU/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate. PINK1‐KO MEFs have been described previously (Muller‐Rischart et al, 2013).

SH‐SY5Y cells

Cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium F‐12 (DMEM/F12) supplemented with 15% (v/v) fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate and 1× MEM nonessential amino acids solution (Gibco™).

HAP1 WT and HAP1 HOIP (RNF31) KO

Cells were cultured in Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) supplemented with 10% (v/v) FBS, 100 IU/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin sulfate, and 8 mM L‐glutamine.

Human primary macrophages

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated from commercially available buffy coats from anonymous donors (DRK‐Blutspendedienst Baden‐Württemberg—Hessen, Institut für Transfusionsmedizin und Immunhämatologie, Frankfurt, Germany) using Pancoll (PAN Biotech, Aidenbach, Germany) density centrifugation. Monocytes were separated from PBMC by adherence to plastic after 1 h incubation in a serum‐free RPMI1640 medium. To differentiate into macrophages, monocytes were cultured in RPMI1640 medium (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin, and 3% human serum (DRK‐Blutspendedienst Baden‐Württemberg—Hessen) for 7 days followed by culture in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% fetal calf serum.

Cultured cells were tested for mycoplasma contamination regularly every 3–4 months.

Transfection and siRNA knockdown

Unless described otherwise, transfections were performed using the following procedures: For SH‐SY5Y and HeLa cells, Lipofectamine and Plus Reagent (Invitrogen) was used according to the manufacturer's instructions. For RNA interference, cells were transfected with stealth siRNA oligos (Invitrogen) using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) or Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) for co‐transfection of siRNA oligos and DNA plasmids. HEK293T cells were transfected using PEI (polyethylenimine). DNA and PEI were mixed in a 1:2 ratio (μg:μl) in Opti‐MEM and incubated for 15 min at room temperature. The DNA‐PEI mixture was then added to the cells.

SPLICSNU‐MT transfection

Transient transfection was performed using the calcium phosphate method. 30,000 HeLa cells/well were seeded on a 24‐well plate on coverslips in the evening. The morning after, a transfection mixture was prepared as follows (quantities reported per well): 50 μl HEPES buffered saline 2x (Merck), 5 μl 2.5 M CaCl2, 1 + 1 μg SPLICSNU‐MT plasmids, and up to 100 μl sterile H2O. The mixture was added to the wells, each containing 500 μl of growth medium. After 8 h, the mixture‐containing medium was removed and replaced with a fresh medium. 24 h after a medium change, the cells were treated as described below and fixed.

SPLICSNU‐MT and siRNA co‐transfection

Co‐transfection of SPLICSNU‐MT plasmids and siRNAs for HOIP silencing was performed using Lipofectamine 3000 (Thermo Fisher). 400,000 HeLa cells/well were seeded on a 6‐well plate in the evening. The morning after, the medium was replaced with 750 μl/well Opti‐MEM (Thermo Fisher), and a transfection mixture with the following composition per well was prepared and added to the wells: 250 μl Opti‐MEM, 0.5 + 0.5 μg SPLICSNU‐MT plasmids, 60 μM each (180 μM in total) stealth siRNA oligos (Invitrogen), and 5 μl Lipofectamine 3,000. 32 h after the addition of the transfection mixture, the cells were detached using trypsin and re‐seeded on a 24‐well plate on coverslips (30,000 cells/well). 16 h after the re‐seeding, the cells were treated as described below and fixed.

Immunoblotting

Proteins were size‐fractionated by SDS–PAGE and transferred to nitrocellulose or polyvinylidene difluoride membranes by electroblotting. The nitrocellulose membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk or 5% BSA in TBST (TBS containing 0.1% Tween 20) for 60 min at room temperature and subsequently incubated with the primary antibody diluted in blocking buffer for 16 h at 4°C. After extensive washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with horseradish peroxidase‐conjugated secondary antibody for 60 min at room temperature. Following washing with TBST, the antigen was detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL) detection system (Promega) as specified by the manufacturer. In addition, immunoblots with fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies were imaged by an Azure Sapphire Biomolecular Imager (Azure Biosystems, USA). For quantification of Western blots, Image Studio lite (version 3.1) and Fiji were used for X‐ray films and AzureSpot (version 2.0) was used for the Sapphire Biomolecular Imager (Azure Biosystems, USA).

Mitochondrial bioenergetics