Abstract

Excessive reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage cells and affect normal cell functions, which are related to various diseases. Selenium nanoparticles are a potential selenium supplement for their good biocompatibility and antioxidant activity. However, their poor stability has become an obstacle for further applications. In this study, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) were prepared as a carrier of selenium nanoparticles. Pluronic F68 (PF68) was used for the surface modification of the compounds to prevent the leakage of the selenium nanoparticles. The prepared MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were characterized by transmission electron microscopy, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, dynamic light scattering, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy, confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy, and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles showed excellent antioxidant activity in HeLa tumor cells and zebrafish larvae. The cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was concentration- and time-dependent in HeLa tumor cells. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles showed a negligible cytotoxicity of ≤2 μg/mL at 48 h. At a concentration of 50 μg/mL, the cell viability of the HeLa tumor cells decreased to about 50%. The results indicated that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be a potential antitumor agent. The embryonic development of zebrafish cocultured with the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles showed that there was no lethal or obvious teratogenic toxicity. The results implied that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be a safe selenium supplement and have the potential for antioxidant and antitumor activity.

1. Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are excited oxygen molecules formed as a byproduct of the metabolism of oxygen, including hydroxyl radicals, superoxide anions, hydrogen peroxide, singlet oxygen, and so on.1 ROS play important roles in many physiological and pathological processes in an organism, which has attracted more and more attention of researchers. Intracellular ROS are maintained at a constant low level in normal physiological conditions, which promotes cell proliferation and survival.2 Oxidative stress is induced by the generation of excess ROS, which breaks the balance of oxidation and antioxidation in vivo. Excessive production of ROS in the body will damage the nucleic acids, proteins, and unsaturated fatty acids, which could affect the normal function of cells.3,4 Moreover, chronic excess ROS will cause cell damage, lead to cell necrosis, accelerate aging and pathological changes in organisms, and induce a series of clinical diseases such as cancer, inflammation, diabetes, and cardiovascular and neurodegenerative diseases.5−8 Oxidative stress is harmful not only to the human body but also to animals. Thus, it will cause great losses to the breeding industry and reduce the quality of livestock, which could affect the health of humans. Therefore, there is an urgent need to reduce oxidative stress.

Antioxidants are the most simple and effective substances in inhibiting and delaying oxidation reactions. At present, there are many potential antioxidants for the preclinical treatment of oxidative stress-related diseases, such as synthetic or natural small-molecule compounds.9−12 However, most antioxidants have unsatisfactory effects after systemic administration. Due to their poor water solubility, instability, or nonspecific distribution in vivo, the application of these agents is still facing great challenges. Therefore, it is important to improve the biocompatibility of antioxidants. Nanoparticles have the advantages of small size and large surface area, which could improve the water dispersion of insoluble antioxidants, keep them from being destroyed, and increase their targeting ability. Hence, antioxidant-loaded nanoparticles have been developed. Mo et al. designed polymer nanoparticles to improve the bioavailability of resveratrol, and the resveratrol-loaded nanoparticles showed great potential in intracerebral hemorrhage treatment.13 Moreover, some nanomaterials possessing antioxidant properties have attracted lots of interest. These nanoparticle antioxidants have been applied for the prevention and treatment of oxidative stress-related diseases. Nanoparticle antioxidants exhibit more effective antioxidant activity for their stronger interactions with biomolecules.14 Ceria nanoparticles have a strong ROS reduction capacity for the reversible binding to oxygen of Ce 3+ and Ce 4+ on the surface.15,16 Bao et al. designed angiopep-2 and poly(ethylene glycol) modified ceria nanoparticles as the carrier of edaravone for stroke treatment. The loaded edaravone and ceria nanoparticles could synergistically eliminate ROS with increased intracephalic uptake.17 Moreover, ceria nanoparticles have potential in the treatment of acute kidney injury18 and regenerative wound healing.19

Selenium is an essential trace element for human health20 and one of the important components of the antioxidant enzyme system.21 It can effectively eliminate free radicals and plays an important role in inhibiting the generation of ROS.22 There are many important endogenous selenium-containing antioxidants in the body. Selenoprotein is a key biomolecule for selenium to realize its physiological function. There are 25 selenoproteins found in the human body, including glutathione peroxidases, thioredoxin reductases, selenoprotein P, selenoprotein F, selenoprotein S, and selenoprotein M.23,24 Selenium, as the redox center of these enzymes, is critical to their biochemical activities. And selenium indirectly exerts its antioxidant activity by enhancing the endogenous antioxidant defense system.25 Selenium has good pharmacological activity in the human immune system and prevention of cardiovascular disease, is an anticancer agent, and so on.22,26 It is reported that more than 40 diseases are directly related to selenium deficiency.27 The undersupply of selenium can increase the risk of chronic degenerative diseases. Inorganic selenium compounds are widely used as selenium supplements. However, they are limited due to high toxicity and low absorption.28 Recent studies have shown that selenium nanoparticles have lower toxicity, higher bioavailability, and stronger biological activity,29 which make them a new selenium supplement. The traditionally synthesized bare selenium nanoparticles are prone to aggregating to precipitate with lower activity.30 The poor stability of selenium nanoparticles has limited their applications. Studies have shown that modification with organic polymer materials could improve the stability and activity of selenium nanoparticles, such as hyaluronic acid,31 bovine serum albumin,32 chitosan,33 and so on (Table 1). Therefore, it is of great importance to develop stable and effective selenium supplements.

Table 1. Comparisons between Published Papers and the Current Study.

| nanoparticle | selenium source | reductant | modification | activity | reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HA-Se@DOX | sodium selenite | vitamin C | HA | antitumor | (31) |

| BSA-Se | sodium selenite | vitamin C | bovine serum albumin | antibacterial | (32) |

| CTS–Se | sodium selenite | vitamin C | chitosan | immunostimulant | (33) |

| MSN@Se@PF68 | sodium selenite | vitamin C | tween 80; MSNs; PF68 | antioxidant and antitumor | the current study |

As a potential inorganic mesoporous material, mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs) can effectively improve their drug loading efficiency for the large specific surface area and specific pore volume.34 And the good biocompatibility of MSNs endows them with broad application prospects, such as drug/gene delivery, bioimaging, photothermal therapy, and so on.35,36 Due to the defect of easy drug desorption, the surface of MSNs is usually coated with polymer materials to reduce drug leakage during transportation. Pluronic F68 is one of the most commonly used polymers and is considered an ideal surface modification polymer for its surfactant function, low toxicity, and minimal immune response.37 In our previous studies, nanoparticle functionalization with pluronic F68 showed favorable stability and tumor accumulation in vitro and in vivo.37−39

Therefore, in this study, selenium nanoparticles are loaded by MSNs and coated with pluronic F68 to construct novel nanoparticle antioxidants. The large pore volume and surface area of MSNs make them suitable for the loading of selenium nanoparticles during the preparation. The activity of selenium nanoparticles is related to their size. The smaller selenium nanoparticles possess higher activity.40 Using the pores of MSNs as the template for the synthesis of selenium nanoparticles, selenium nanoparticles of small particle sizes were prepared and loaded. A sustained release behavior of the selenium nanoparticles from MSNs will be achieved. The modification with pluronic F68 could reduce the desorption of selenium nanoparticles from MSNs and improve the loading efficiency. The design will improve the water dispersibility and stability of the nanoparticles and prevent the selenium nanoparticles from forming inactive precipitates. Moreover, PF68 could enhance the cellular uptake of tumor cells. The composite nanoparticles are designed to supply selenium with the potential application of eliminating ROS and as an antitumor agent.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Hexadecyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB), tetraethoxysilane (TEOS), and (2-cyanopropyl) triethoxysilane (CPTES) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Regent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Sodium selenite, vitamin C (VC), and Tween 80 were bought from Sinopharm Chemical Regent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Pluronic F68 (PF68) was kindly provided by BASF China Ltd. (Shanghai, China).

2.2. Synthesis of MSNs

Carboxyl-modified mesoporous silica nanoparticles were prepared by polymerization and hydrolysis. CTAB (1.2 g) was dissolved in 180 mL of deionized water with 20 mL of ethylene glycol and 5.5 mL of aqueous ammonia solution and stirred at 60 °C for 30 min. Afterward, 2.0 mL of TEOS and 0.4 mL of CPTES were mixed and quickly added to the above solution and stirred for 2 h at 60 °C. Then, the mixture was allowed to stand for 24 h at 60 °C, and the product was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min. CTAB was removed by refluxing with acid ethanol (9 mL of HCl in 100 mL of ethanol) at 60 °C for 24 h. The product was washed with deionized water and acid ethanol repeatedly and purified by high-speed centrifugation. Then, the product was hydrolyzed under acidic conditions (9 M H2SO4 solution) at 80 °C for 24 h and purified by deionized water washing. Finally, carboxyl-modified MSNs were obtained by lyophilization.

2.3. Synthesis of MSN@Se@PF68 Nanoparticles

MSNs were dispersed in 1% Tween 80 solution, and sodium selenite was added. Under rapid stirring, vitamin C was added and stirred in the dark for 24 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min and dispersed in deionized water. Afterward, PF68 was added and stirred in the dark for 24 h. The product was collected by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 30 min and washed with deionized water 3 times. The nanoparticles were characterized by transmission electron microscopy (TEM; JEM-2100F microscope, Japan), dynamic light scattering (Malvern NANO-ZS, U.K.), energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS; JEM-2100F microscope, Japan), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS; Thermo Fisher Scientific 250XI, Germany), confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy (Thermo Fisher Scientific DXR2xi), and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet5700).

2.4. Cell Viability Assay

The 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to evaluate the cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles against HeLa tumor cells. The tumor cells were cultured in a cell incubator (37 °C and 5% CO2). HeLa tumor cells in the logarithmic growth phase were seeded into 96-well plates in a final volume of 100 μL of culture medium. After overnight incubation, the cells were treated with increasing concentrations of MSN@Se@PF68 and co-incubated for 24 or 48 h. Then, 31.5 μL of the MTT solution (5 mg/mL, in PBS) was added and incubated for another 4 h. Afterward, the culture medium was replaced with 200 μL of DMSO. A microplate reader (Bio-Rad) was used to detect the absorbance at 570 nm.

2.5. ROS Level Detection

HeLa tumor cells were seeded into 6-well plates at the density of 2 × 105 cells per well and cultured overnight. The cells were treated with 100 μM hydrogen peroxide and MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles and cocultured for 4 h. Then, the tumor cells were washed with deionized water and incubated in 5 μM 2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) working solution at 37 °C in the dark for 30 min. The cells were washed 3 times, and the fluorescence of 2′,7′-dichlorofluorescein (DCF) was detected by a fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ti-S, Tokyo, Japan).

2.6. Toxicity Evaluation In Vivo

Zebrafish have the advantages of small size, transparent embryos, high homology with human genes, and a short experiment period. Therefore, zebrafish are widely used as an important model for toxicology research. In this study, zebrafish were used to evaluate the developmental toxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The AB-wild type adult female and male zebrafish were cultured separately in feeding equipment at 28 °C with a 14/10 h (light/dark) photoperiod. Strong female and male zebrafish were selected and respectively placed in a spawning box with a partition at a 1:3 ratio at night before breeding. Then, the male and female zebrafish were mixed by removing the partition in the early morning. The male zebrafish would chase the female zebrafish to lay eggs and fertilize them. The healthy embryos were collected and cultured for further experiments. Zebrafish embryos at 7 h postfertilization (hpf) were randomly divided into five groups, with twenty embryos in each group. MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were exposed to zebrafish embryos with various concentrations (50, 100, 200, 400 μg/mL) and cultured at 28 °C until 24 hpf. The mortality of the zebrafish embryos was counted every day until 3 dpf, and the developmental morphology of the zebrafish embryos was observed under the microscope at 3 dpf. The hatchability of the zebrafish embryos and the normal spine development rate of the zebrafish larvae were calculated.

2.7. In Vivo Antioxidant

Studies have shown that 2,2′-azobis(2-methylpropionamidine) dihydrochloride (AAPH) can be used as a model chemical reagent to induce ROS in zebrafish embryos.41,42 Zebrafish embryos at 7 hpf were randomly divided into five groups with 20 embryos in each group. APPH (15 mM) was cocultured with the embryos until 24 hpf. Then, the culture medium was changed every 12 h until 3 dpf. Zebrafish larvae were incubated with 40 μM DCFH-DA working solution at 28 °C in the dark for 1 h and washed 3 times. Tricaine was added to anesthetize the zebrafish larvae. The fluorescence of DCF was detected by a fluorescence microscope (Nikon ECLIPSE Ti-S, Tokyo, Japan).

3. Results

3.1. Synthesis and Characterization of MSN@Se@PF68 Nanoparticles

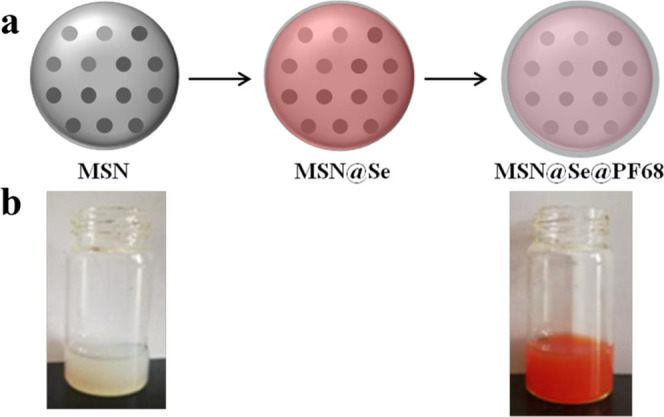

The schematic diagram of the preparation of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles is shown in Figure 1a. Selenium nanoparticles were encapsulated by MSNs with the surface modification of PF68. The purpose of the design is to increase the encapsulation efficiency and slow down the leakage of selenium nanoparticles. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were well dispersed in deionized water (Figure 1b). The solution of MSNs was milky white, and the solution of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was brick red due to the encapsulation of selenium nanoparticles.

Figure 1.

Synthesis of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (a) Schematic illustration of the construction of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (b) Water solutions of MSNs and MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles.

The morphology of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles is shown in Figure 2. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were nearly spherical with regular shapes and good dispersibility (Figure 2a). The mesoporous structure of MSNs could be clearly seen. The diameter of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was about 60 nm. The nanostructure of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was confirmed by EDS elemental mapping of O (red), Si (green), and Se (blue) (Figure 2b). The results revealed the existence of Se in the composite nanoparticles. The hydrodynamic size of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was detected by dynamic light scattering (Figure 2c). The results showed that the hydrodynamic size of freshly prepared MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was 227.2 ± 25.0 nm. After storage for 3 months at 4 °C, MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were still well dispersed in water and the hydrodynamic size became 247.9 ± 34.7 nm. The results implied that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles possessed good stability.

Figure 2.

Size and morphology of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (a) TEM images. (b) EDS elemental mapping of O (red), Si (green), and Se (blue). (c) Hydrodynamic diameters detected by dynamic light scattering (mean ± SD, n = 3). Sample 1: freshly prepared nanoparticles; sample 2: after storage for 3 months at 4 °C.

XPS was further used to verify the chemical composition of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The XPS spectra showed the characteristic peaks of O, C, Se, and Si (Figure 3). The characteristic binding energy of Si was 103.4 eV (Si, 2p), as shown in Figure 3e. The signature of C–O presented at 286.7 eV proved the successful modification with PF68 (Figure 3b). The peaks at 161.8 and 55.5 eV ascribed to Se 3p and Se 3d indicated the encapsulation of Se0 (Figure 3d,f).43

Figure 3.

(a) Survey XPS spectrum of the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles and the corresponding spectra of (b) O 1s, (c) C–O and C 1s, (d) Se 3p, (e) Si 2p, and (f) Se 3d.

The FTIR spectra of MSNs, PF68, and MSN@Se@PF68 are shown in Figure 4. The absorptions at 3388 and 1659 cm–1 belong to the −OH and C=O of the carboxyl group of MSNs, respectively (Figure 4a). The absorptions at 1076, 806, and 458.43 cm–1 are the characteristic peaks of Si–O–Si (Figure 4a).44 In Figure 4b, the absorption at 2900 cm–1 belongs to the stretching vibration frequency of C–H and the absorption at 1123 cm–1 belongs to the stretching vibration frequency of C–O, which are the characteristic peaks of PF68.45 In Figure 4c, the composite MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles have the characteristic absorption peaks of MSNs and pluronic F68, which confirmed the successful modification of MSNs with PF68.

Figure 4.

FTIR spectra of (a) MSNs/COOH, (b) PF68, and (c) MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (d) Raman spectrum of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles using 532 nm excitation.

The Raman spectrum of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was detected by confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy, and the result is shown in Figure 4d. The characteristic resonance peak at 253 cm–1 is attributed to the amorphous selenium.46 Therefore, the loaded selenium nanoparticles were amorphous.

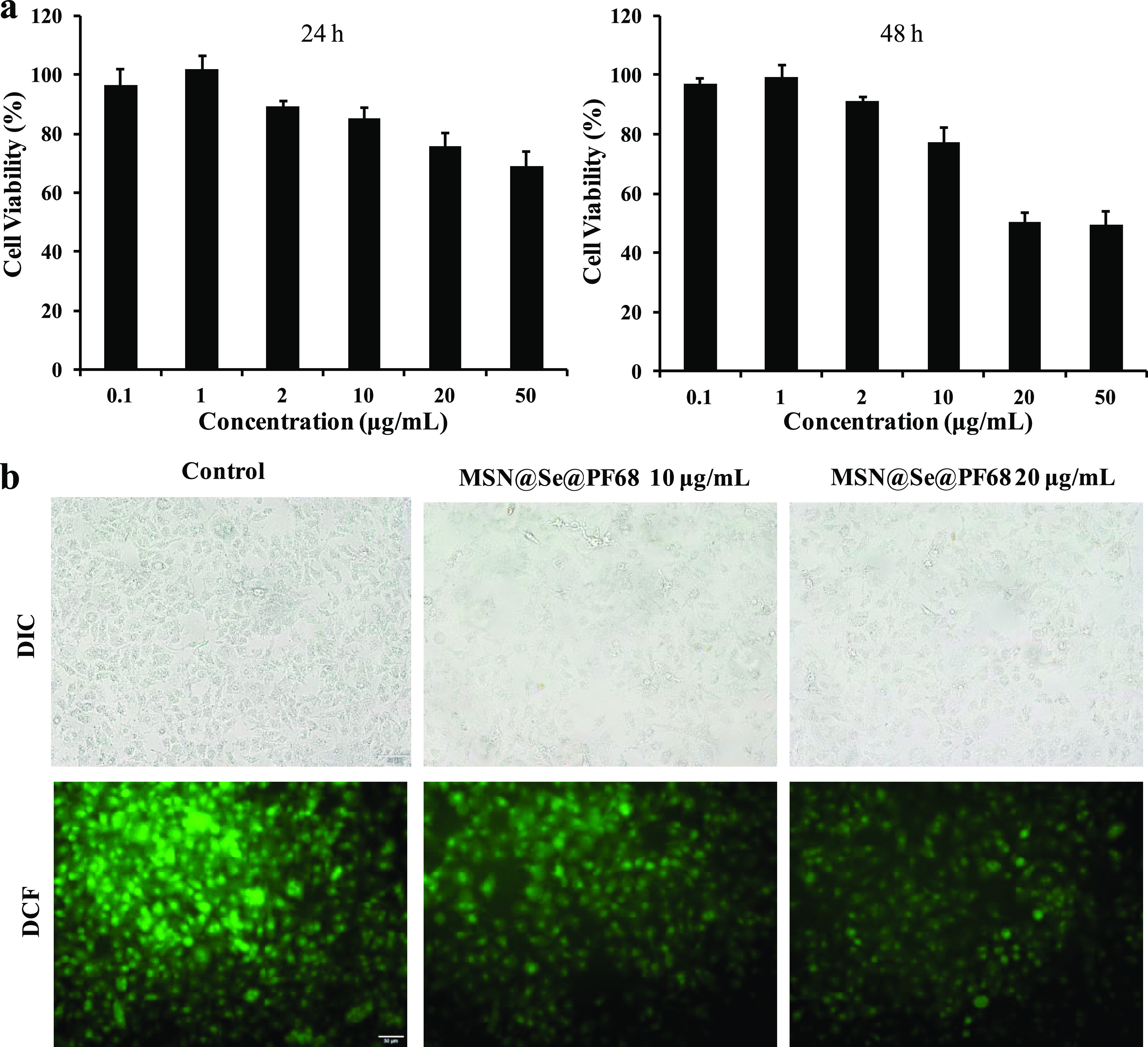

3.2. Cytotoxicity In Vitro

The cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was detected using HeLa tumor cells as a model, and the results are shown in Figure 5a. The cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was concentration-dependent. At 24 h, the nanoparticles showed negligible cytotoxicity at low concentrations with no more than 10 μg/mL. As the concentration increased, the cell viability decreased to about 70% at the concentration of 50 μg/mL. The cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was also time-dependent. At 48 h, higher toxicity of the nanoparticles was observed. The cell viability decreased to about 50% at the concentration of 50 μg/mL. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could inhibit the growth of tumor cells at high concentrations and in long-term cultures. The results implied that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be a safe selenium supplement at low concentrations and an antitumor agent at high concentrations.

Figure 5.

In vitro antitumor and antioxidant activity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (a) Cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles against HeLa tumor cells at 24 and 48 h. (b) Antioxidant activity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles in HeLa tumor cells by the DCFH-DA method.

3.3. Antioxidant Activity In Vitro

The cellular ROS level was detected by the DCFH-DA assay. DCFH-DA has no fluorescence and can pass through the cell membrane freely. In the cells, DCFH-DA can be hydrolyzed to fluorescent DCF by ROS. DCF cannot penetrate cell membranes, making it easy to be loaded into cells. The fluorescence intensity of DCF is shown in Figure 5b. The control group treated with H2O2 showed the highest fluorescence intensity. With the culture of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles, the fluorescence intensity decreased in a concentration-dependent manner. At 20 μg/mL concentration of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles, the cells showed the lowest DCF fluorescence intensity. The results imply that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles have the potential to reduce the intracellular ROS level induced by H2O2.

3.4. Toxicity In Vivo

The embryonic development of zebrafish was observed under a microscope, and the result is shown in Figure 6a. According to statistical calculations, the hatchability of the zebrafish embryos was 100%. There was no lethal or obvious teratogenic toxicity after the coculture with the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The hatchability of the zebrafish embryos was 100%. The zebrafish larvae were in normal shape with no cytosis after the treatment with 400 μg/mL MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The results implied that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles had no obvious developmental toxicity to zebrafish embryos.

Figure 6.

In vivo developmental toxicity and antioxidant activity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (a) Morphology of the zebrafish larvae after the treatment with various concentrations of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. (b) Antioxidant activity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles in zebrafish larvae by the DCFH-DA method.

3.5. Antioxidant Activity In Vivo

The in vivo antioxidant activity of the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was observed using zebrafish embryos as models. The fluorescence intensity of DCF is shown in Figure 6b. The fluorescence of the zebrafish larvae in the control group treated with APPH was the strongest. With the culture of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles, the fluorescence intensity significantly decreased. As the concentration of the nanoparticles increased, lower fluorescence intensity was observed. The results indicated that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles played a role in eliminating excessive ROS in vivo in a concentration-dependent manner and showed good antioxidant performance.

4. Discussion

ROS are a double-edged sword in vivo. At low levels, ROS have important physiological functions as essential cell transduction signals for tissue development, normal function, and repair.47 However, excessive ROS will damage normal cells and induce various diseases. Selenium is well known for its great importance as an antioxidative agent and in enhancing immunity.48 Nevertheless, selenium is unevenly distributed in nature. People in many countries suffer from selenium deficiency to varying degrees. Incidences of tumors and cardiovascular and cerebrovascular diseases are very high in areas with a lack of selenium.49 Therefore, supplementary selenium is necessary for enhancing physical fitness and preventing diseases. Selenium nanoparticles are a kind of nanosized volatile selenium. They have a higher antioxidant effect and lower toxicity than inorganic selenium. Nano-selenium has high surface energy and tends to aggregate into a gray color and lose activity. Therefore, the development of novel selenium nanoparticles as a functional food factor is of great significance in guiding the rational diet and scientific selenium supplement. Silicon is widely found in nature and is a very safe substance, which is widely used in cosmetics and food additives. Silicon is generally recognized as safe by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).50 MSNs are mainly eliminated through urine and feces and have relatively high biocompatibility in vitro and in vivo with no significant toxicity. Therefore, MSNs are relatively safe nanodrug delivery systems. Studies have shown that MSNs with the modification of organic materials may improve their biocompatibility.51 In this study, MSNs were prepared as the template and carrier of selenium nanoparticles. To improve the stability of the MSN@Se nanoparticles, pluronic F68, an FDA-approved triblock copolymer, was used to modify the surface of the nanoparticles. The amphiphilic PF68 copolymers were coated to improve the loading efficiency, prevent the leakage of selenium nanoparticles, and improve the water dispersion of the compounds. The stability of selenium nanoparticles was improved by the formation of the O–H···Se interaction with the carboxyl group of MSNs or the hydroxyl group of PF68.52 Selenium nanoparticles are brick red;53 thus, the loading of selenium nanoparticles can be observed by the change of the color. The prepared MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were brick red and well dispersed in water. The slight hydrodynamic size variation indicated that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles were stable enough after storage for 3 months at 4 °C. The morphology of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was nearly spherical. The EDC elemental mapping, XPS spectra, and FTIR spectra confirmed the successful preparation of the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The Raman spectrum implied that the loaded selenium nanoparticles were amorphous. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles showed good antioxidant activity in a concentration-dependent manner in vitro and in vivo. The intracellular ROS level in HeLa tumor cells induced by H2O2 could be reduced by the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The ROS level in zebrafish larvae induced by APPH also could be reduced by the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. There was no obvious developmental toxicity of zebrafish embryos after the treatment with the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles at a high concentration of 400 μg/mL. The results implied that the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be a safe selenium supplement. The cytotoxicity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles was detected against HeLa tumor cells. At high concentrations, the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could inhibit the growth of tumor cells to a certain extent. The potential antitumor mechanisms of the MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles are not clear. Many theories and hypotheses have been proposed for the mechanism of antitumor activity of selenium nanoparticles. Selenium nanoparticles mainly exert an antitumor effect by inducing apoptosis.54 The antioxidant activity of selenium nanoparticles could modulate the metabolism of tumor cells to inhibit cell proliferation.55,56 Moreover, studies have proved that selenium can mobilize immunity to resist tumors.57−59 Various mechanisms are involved in the antitumor activity of selenium nanoparticles. More complicated antitumor mechanisms of selenium nanoparticles are under study. Thus, the antioxidant activity and selenium supply of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be responsible for their antitumor activity. Moreover, the surface modification of PF68 is able to prolong the nanoparticle circulation in the blood and sensitize cancer cells to drugs.60 Therefore, the application of PF68 could improve the antitumor activity of MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles could be applied as a potential antitumor agent, and the antitumor activity should be improved by combination with chemotherapeutic drugs. Our next work will focus on the codelivery of chemotherapeutic drugs and selenium nanoparticles for the treatment of cancer and the study of the possible mechanisms.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we successfully constructed MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles. Selenium nanoparticles were loaded by MSNs and coated with PF68 to obtain a stable compound in deionized water. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles showed good antioxidant activity in vitro and in vivo. The MSN@Se@PF68 nanoparticles have potential as a in selenium supplement with antioxidant and antitumor properties. However, the complicated antitumor mechanisms have not been elucidated. Our next work will try to solve this problem and evaluate the antitumor effect of the nanoparticles with the codelivery of chemotherapeutic drugs.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82104112) and the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2019BH054).

Author Contributions

§ M.W. and X.S. contributed equally to this work.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

References

- Wu H.; Shabala L.; Shabala S.; Giraldo J. P. Hydroxyl radical scavenging by cerium oxide nanoparticles improves Arabidopsis salinity tolerance by enhancing leaf mesophyll potassium retention. Environ. Sci.: Nano 2018, 5, 1567–1583. 10.1039/C8EN00323H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ray P. D.; Huang B.-W.; Tsuji Y. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) homeostasis and redox regulation in cellular signaling. Cell. Signalling 2012, 24, 981–990. 10.1016/j.cellsig.2012.01.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez X.; Sanon S.; Zambrano K.; Asquel S.; Bassantes M.; Morales J. E.; Otáñez G.; Pomaquero C.; Villarroel S.; Zurita A.; Calvache C.; Celi K.; Contreras T.; Corrales D.; Naciph M. B.; Peña J.; Caicedo A. Key points for the development of antioxidant cocktails to prevent cellular stress and damage caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS) during manned space missions. NPJ Microgravity 2021, 7, 35 10.1038/s41526-021-00162-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polaka S.; Katare P.; Pawar B.; Vasdev N.; Gupta T.; Rajpoot K.; Sengupta P.; Tekade R. K. Emerging ROS-modulating technologies for augmentation of the wound healing process. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 30657–30672. 10.1021/acsomega.2c02675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waris G.; Ahsan H. Reactive oxygen species: role in the development of cancer and various chronic conditions. J. Carcinog. 2006, 5, 14 10.1186/1477-3163-5-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittal M.; Siddiqui M. R.; Tran K.; Reddy S. P.; Malik A. B. Reactive oxygen species in inflammation and tissue injury. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2014, 20, 1126–1167. 10.1089/ars.2012.5149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh A.; Kukreti R.; Saso L.; Kukreti S. Oxidative stress: a key modulator in neurodegenerative diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 1583 10.3390/molecules24081583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noddeland H. K.; Kemp P.; Urquhart A. J.; Herchenhan A.; Rytved K. A.; Petersson K.; B Jensen L. Reactive oxygen species-responsive polymer nanoparticles to improve the treatment of inflammatory skin diseases. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 25055–25065. 10.1021/acsomega.2c01071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- More G. K.; Makola R. T. In-vitro analysis of free radical scavenging activities and suppression of LPS-induced ROS production in macrophage cells by Solanum sisymbriifolium extracts. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 6493 10.1038/s41598-020-63491-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetisova E.; Chernyak B.; Korshunova G.; Muntyan M.; Skulachev V. Mitochondria-targeted antioxidants as a prospective therapeutic strategy for multiple sclerosis. Curr. Med. Chem. 2017, 24, 2086–2114. 10.2174/0929867324666170316114452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L.; Liu P.; Feng X.; Ma C. Salidroside suppressing LPS-induced myocardial injury by inhibiting ROS-mediated PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in vitro and in vivo. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2017, 21, 3178–3189. 10.1111/jcmm.12871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mira-Sánchez M. D.; Castillo-Sánchez J.; Morillas-Ruiz J. M. Comparative study of rosemary extracts and several synthetic and natural food antioxidants. Relevance of carnosic acid/carnosol ratio. Food Chem. 2020, 309, 125688 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Y.; Duan L.; Yang Y.; Liu W.; Zhang Y.; Zhou L.; Su S.; Lo P. C.; Cai J.; Gao L.; Liu Q.; Chen X.; Yang C.; Wang Q.; Chen T. Nanoparticles improved resveratrol brain delivery and its therapeutic efficacy against intracerebral hemorrhage. Nanoscale 2021, 13, 3827–3840. 10.1039/D0NR06249A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhir R.; Yadav A.; Sunkaria A.; Singhal N. Nano-antioxidants: an emerging strategy for intervention against neurodegenerative conditions. Neurochem. Int. 2015, 89, 209–226. 10.1016/j.neuint.2015.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu H.; Jin F.; Liu D.; Shu G.; Wang X.; Qi J.; Sun M.; Yang P.; Jiang S.; Ying X.; Du Y. ROS-responsive nano-drug delivery system combining mitochondria-targeting ceria nanoparticles with atorvastatin for acute kidney injury. Theranostics 2020, 10, 2342–2357. 10.7150/thno.40395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson P.; Truong A. H. T.; Brommesson C.; du Rietz A.; Kokil G. R.; Boyd R. D.; Hu Z.; Dang T. T.; Persson P. O. A.; Uvdal K. Cerium oxide nanoparticles with entrapped gadolinium for high T1 relaxivity and ROS-scavenging purposes. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 21337–21345. 10.1021/acsomega.2c03055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Q.; Hu P.; Xu Y.; Cheng T.; Wei C.; Pan L.; Shi J. Simultaneous blood-brain barrier crossing and protection for stroke treatment based on edaravone-loaded ceria nanoparticles. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 6794–6805. 10.1021/acsnano.8b01994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng Q.; Sun H.; Fang C.; Xia F.; Liao H.; Lee J.; Wang J.; Xie A.; Ren J.; Guo X.; Li F.; Yang B.; Ling D. Catalytic activity tunable ceria nanoparticles prevent chemotherapy-induced acute kidney injury without interference with chemotherapeutics. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 1436 10.1038/s41467-021-21714-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu H.; Li F.; Wang S.; Lu J.; Li J.; Du Y.; Sun X.; Chen X.; Gao J.; Ling D. Ceria nanocrystals decorated mesoporous silica nanoparticle based ROS-scavenging tissue adhesive for highly efficient regenerative wound healing. Biomaterials 2018, 151, 66–77. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geoffrion L. D.; Hesabizadeh T.; Medina-Cruz D.; Kusper M.; Taylor P.; Vernet-Crua A.; Chen J.; Ajo A.; Webster T. J.; Guisbiers G. Naked selenium nanoparticles for antibacterial and anticancer treatments. ACS Omega 2020, 5, 2660–2669. 10.1021/acsomega.9b03172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alkie T. N.; de Jong J.; Moore E.; DeWitte-Orr S. J. Phytoglycogen nanoparticle delivery system for inorganic selenium reduces cytotoxicity without impairing selenium bioavailability. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 10469–10479. 10.2147/IJN.S286948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q.; Guan X.; Lai C.; Gao H.; Zheng Y.; Huang J.; Lin B. Selenium enrichment improves anti-proliferative effect of oolong tea extract on human hepatoma HuH-7 cells. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2021, 147, 111873 10.1016/j.fct.2020.111873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khurana A.; Tekula S.; Saifi M. A.; Venkatesh P.; Godugu C. Therapeutic applications of selenium nanoparticles. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2019, 111, 802–812. 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.12.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuršvietienė L.; Mongirdienė A.; Bernatonienė J.; Šulinskienė J.; Stanevičienė I. Selenium anticancer properties and impact on cellular redox status. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 80 10.3390/antiox9010080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z.; Ren Y.; Liang Y.; Huang L.; Yang Y.; Zafar A.; Hasan M.; Yang F.; Shu X. Synthesis, characterization, immune regulation, and antioxidative assessment of yeast-derived selenium nanoparticles in cyclophosphamide-induced rats. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 24585–24594. 10.1021/acsomega.1c03205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins D. J. A.; Kitts D.; Giovannucci E. L.; Sahye-Pudaruth S.; Paquette M.; Blanco Mejia S.; Patel D.; Kavanagh M.; Tsirakis T.; Kendall C. W. C.; Pichika S. C.; Sievenpiper J. L. Selenium, antioxidants, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 112, 1642–1652. 10.1093/ajcn/nqaa245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng R.; Zhao P.; Zhu Y.; Yang J.; Wei X.; Yang L.; Liu H.; Rensing C.; Ding Y. Application of inorganic selenium to reduce accumulation and toxicity of heavy metals (metalloids) in plants: the main mechanisms, concerns, and risks. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 771, 144776 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.144776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangadoo S.; Dinev I.; Willson N. L.; Moore R. J.; Chapman J.; Stanley D. Nanoparticles of selenium as high bioavailable and non-toxic supplement alternatives for broiler chickens. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2020, 27, 16159–16166. 10.1007/s11356-020-07962-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L.; Zhao J.; Wang L.; Liu Q.; Fan Y.; Li B.; Yu Y. L.; Chen C.; Li Y. F. Using nano-selenium to combat Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19)?. Nano Today 2021, 36, 101037 10.1016/j.nantod.2020.101037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu B.; Zhang Y.; Zheng W.; Fan C.; Chen T. Positive surface charge enhances selective cellular uptake and anticancer efficacy of selenium nanoparticles. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 8956–8963. 10.1021/ic301050v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia Y.; Xiao M.; Zhao M.; Xu T.; Guo M.; Wang C.; Li Y.; Zhu B.; Liu H. Doxorubicin-loaded functionalized selenium nanoparticles for enhanced antitumor efficacy in cervical carcinoma therapy. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2020, 106, 110100 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S.; Zhou R.; Webster T. J. Green synthesized BSA-coated selenium nanoparticles inhibit bacterial growth while promoting mammalian cell growth. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 115–124. 10.2147/IJN.S193886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xia I. F.; Cheung J. S. T.; Wu M.; Wong K. S.; Kong H. K.; Zheng X. T.; Wong K. H.; Kwok K. W. Dietary chitosan-selenium nanoparticle (CTS-SeNP) enhance immunity and disease resistance in zebrafish. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 2019, 87, 449–459. 10.1016/j.fsi.2019.01.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sábio R. M.; Meneguin A. B.; Ribeiro T. C.; Silva R. R.; Chorilli M. New insights towards mesoporous silica nanoparticles as a technological platform for chemotherapeutic drugs delivery. Int. J. Pharm. 2019, 564, 379–409. 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2019.04.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou S.; Ding C.; Wang C.; Fu J. UV-light cross-linked and pH de-cross-linked coumarin-decorated cationic copolymer grafted mesoporous silica nanoparticles for drug and gene co-delivery in vitro. Mater. Sci. Eng.: C 2020, 108, 110469 10.1016/j.msec.2019.110469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan R.; Gadag S.; Garg S.; Nayak U. Y. Understanding the effect of functionalization on loading capacity and release of drug from mesoporous silica nanoparticles: a computationally driven study. ACS Omega 2022, 7, 8229–8245. 10.1021/acsomega.1c03618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Xiao Y.; Li Y.; Wu J.; Li F.; Ling D.; Gao J. Reactive oxygen species and near-infrared light dual-responsive indocyanine green-loaded nanohybrids for overcoming tumour multidrug resistance. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2019, 134, 185–193. 10.1016/j.ejps.2019.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Li Y.; HuangFu M.; Xiao Y.; Zhang T.; Han M.; Xu D.; Li F.; Ling D.; Jin Y.; Gao J. Pluronic-attached polyamidoamine dendrimer conjugates overcome drug resistance in breast cancer. Nanomedicine 2016, 11, 2917–2934. 10.2217/nnm-2016-0252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Wu J.; Li Y.; Li F.; Hu X.; Wang G.; Han M.; Ling D.; Gao J. A tumor targeted near-infrared light-controlled nanocomposite to combat with multidrug resistance of cancer. J. Controlled Release 2018, 288, 34–44. 10.1016/j.jconrel.2018.08.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres S. K.; Campos V. L.; León C. G.; Rodríguez-Llamazares S. M.; Rojas S. M.; González M.; et al. Biosynthesis of selenium nanoparticles by Pantoea agglomerans and their antioxidant activity. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14, 1236 10.1007/s11051-012-1236-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M. C.; Cha S. H.; Wijesinghe W. A.; Kang S. M.; Lee S. H.; Kim E. A.; Song C. B.; Jeon Y. J. Protective effect of marine algae phlorotannins against AAPH-induced oxidative stress in zebrafish embryo. Food Chem. 2013, 138, 950–955. 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.; Huang T.; Tian C.; Xiao Y.; Kou S.; Zhou X.; Liu S.; Ye X.; Li X. The defensive effect of phellodendrine against AAPH-induced oxidative stress through regulating the AKT/NF-κB pathway in zebrafish embryos. Life Sci. 2016, 157, 97–106. 10.1016/j.lfs.2016.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J.; Wei Y.; Yang X.; Ni S.; Hong F.; Ni S. Construction of selenium-embedded mesoporous silica with improved antibacterial activity. Colloids Surf., B 2020, 190, 110910 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2020.110910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paiva M. R. B.; Andrade G. F.; Dourado L. F. N.; Castro B. F. M.; Fialho S. L.; Sousa E. M. B.; Silva-Cunha A. Surface functionalized mesoporous silica nanoparticles for intravitreal application of tacrolimus. J. Biomater. Appl. 2021, 35, 1019–1033. 10.1177/0885328220977605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patil S.; Ujalambkar V.; Rathore A.; Rojatkar S.; Pokharkar V. Galangin loaded galactosylated pluronic F68 polymeric micelles for liver targeting. Biomed. Pharmacother 2019, 112, 108691 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tugarova A. V.; Mamchenkova P. V.; Dyatlova Y. A.; Kamnev A. A. FTIR and Raman spectroscopic studies of selenium nanoparticles synthesised by the bacterium Azospirillum thiophilum. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 2018, 192, 458–463. 10.1016/j.saa.2017.11.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkovic L.; Cipak Gasparovic A.; Cindric M.; Mouthuy P.-A.; Zarkovic N. Short overview of ROS as cell function regulators and their implications in therapy concepts. Cells 2019, 8, 793 10.3390/cells8080793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Z.; Rose A. H.; Hoffmann P. R. The role of selenium in inflammation and immunity: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Antioxid. Redox Signaling 2012, 16, 705–743. 10.1089/ars.2011.4145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akahoshi N.; Anan Y.; Hashimoto Y.; Tokoro N.; Mizuno R.; Hayashi S.; Yamamoto S.; Shimada K. I.; Kamata S.; Ishii I. Dietary selenium deficiency or selenomethionine excess drastically alters organ selenium contents without altering the expression of most selenoproteins in mice. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2019, 69, 120–129. 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2019.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun B.; Pokhrel S.; Dunphy D. R.; Zhang H.; Ji Z.; Wang X.; Wang M.; Liao Y. P.; Chang C. H.; Dong J.; Li R.; Mädler L.; Brinker C. J.; Nel A. E.; Xia T. Reduction of acute inflammatory effects of fumed silica nanoparticles in the lung by adjusting silanol display through calcination and metal doping. ACS Nano 2015, 9, 9357–9372. 10.1021/acsnano.5b03443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu J.; Liong M.; Li Z.; Zink J. I.; Tamanoi F. Biocompatibility, biodistribution, and drug-delivery efficiency of mesoporous silica nanoparticles for cancer therapy in animals. Small 2010, 6, 1794–1805. 10.1002/smll.201000538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J. K.; Qiu W. Y.; Wang Y. Y.; Wang W. H.; Yang Y.; Zhang H. N. Fabrication and stabilization of biocompatible selenium nanoparticles by carboxylic curdlans with various molecular properties. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 19–27. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvi G. B.; Iqbal M. S.; Ghaith M. M. S.; Haseeb A.; Ahmed B.; Qadir M. I. Biogenic selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) from citrus fruit have anti-bacterial activities. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4811 10.1038/s41598-021-84099-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varlamova E. G.; Goltyaev M. V.; Mal’tseva V. N.; Turovsky E. A.; Sarimov R. M.; Simakin A. V.; Gudkov S. V. Mechanisms of the cytotoxic effect of selenium nanoparticles in different human cancer cell lines. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7798 10.3390/ijms22157798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu B.; Zhang Q.; Luo X.; Ning X.; Luo J.; Guo J.; Liu Q.; Ling G.; Zhou N. Selenium nanoparticles reduce glucose metabolism and promote apoptosis of glioma cells through reactive oxygen species-dependent manner. NeuroReport 2020, 31, 226–234. 10.1097/WNR.0000000000001386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y.; Zhang Z.; Chen Q.; You Y.; Li X.; Chen T. Functionalized selenium nanoparticles synergizes with metformin to treat breast cancer cells through regulation of selenoproteins. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2021, 9, 758482 10.3389/fbioe.2021.758482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Y.; Liu T.; Li J.; Mai F.; Li J.; Chen Y.; Jing Y.; Dong X.; Lin L.; He J.; Xu Y.; Shan C.; Hao J.; Yin Z.; Chen T.; Wu Y. Selenium nanoparticles as new strategy to potentiate γδ T cell anti-tumor cytotoxicity through upregulation of tubulin-α acetylation. Biomaterials 2019, 222, 119397 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2019.119397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S.; Li T.; Guo Y.; Sun C.; Xianyu B.; Xu H. Selenium-containing nanoparticles combine the NK cells mediated immunotherapy with radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Adv. Mater. 2020, 32, e1907568 10.1002/adma.201907568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan S.; Li T.; Tan Y.; Xu H. Selenium-containing nanoparticles synergistically enhance Pemetrexed&NK cell-based chemoimmunotherapy. Biomaterials 2022, 280, 121321 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2021.121321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X.; Xu Y.; Wang S.; Wan J.; He C.; Chen M. Pluronic F68-linoleic acid nano-spheres mediated delivery of gambogic acid for cancer therapy. AAPS PharmSciTech 2017, 18, 147–155. 10.1208/s12249-015-0473-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]