Abstract

A 10-week-old Yorkshire terrier had lameness of the right forelimb with complete lateral radioulnar luxation at the humerus, consistent with Type III congenital elbow luxation; this is rarely treated in the presence of multiple skeletal deformities. Lateral subluxation of the radial head at the left elbow was diagnosed as Type I congenital elbow luxation. Procurvatum, distal valgus, and external torsion were present in both antebrachiae. Surgical stabilization of the right elbow was performed with temporary transarticular pins in the humeroulnar and radioulnar joints. A custom-made orthosis was applied to support the surgical reduction for 20 wk. Recurrent luxation was not observed. After complete right-sided function was established, the left forelimb showed noticeable instability in the antebrachium, and the puppy frequently fell while running. The lateral collateral ligament of the left elbow was augmented using screws and synthetic ligaments 22 wk after the right-side surgery. Congruity of the left elbow joint improved, and the puppy could bear full weight on the left forelimb, although slight deficits in movement and falling were observed. We demonstrate the effectiveness of combining a temporary transarticular pin and custom-made orthosis while treating Type III congenital elbow luxation and the inadequacy of collateral ligament augmentation alone for treating Type I congenital elbow luxation with antebrachium deformities.

Key clinical message:

Herein, we observed that a combination of a temporary transarticular pin and a custom-made orthosis was effective for the treatment of Type III congenital elbow luxations.

Résumé

Luxation bilatérale non traumatique du coude chez un chiot Yorkshire terrier. Un Yorkshire terrier de 10 semaines présentait une boiterie du membre antérieur droit avec une luxation radio-ulnaire latérale complète au niveau de l’humérus, compatible avec une luxation congénitale du coude de type III; ceci est rarement traité en présence de multiples déformations squelettiques. La subluxation latérale de la tête radiale au niveau du coude gauche a été diagnostiquée comme une luxation congénitale du coude de type I. Procurvatum, valgus distal et torsion externe étaient présents dans les deux sections antébrachiales. La stabilisation chirurgicale du coude droit a été réalisée avec des broches trans-articulaires temporaires dans les articulations huméro-ulnaire et radio-ulnaire. Une orthèse sur mesure a été appliquée pour soutenir la réduction chirurgicale pendant 20 semaines. Aucune luxation récurrente n’a été observée. Une fois la fonction complète du côté droit établie, le membre antérieur gauche a montré une instabilité notable de la section antébrachiale et le chiot tombait fréquemment en courant. Le ligament collatéral latéral du coude gauche a été augmenté à l’aide de vis et de ligaments synthétiques 22 semaines après la chirurgie du côté droit. La congruence de l’articulation du coude gauche s’est améliorée et le chiot pouvait supporter tout son poids sur le membre antérieur gauche, bien que de légers déficits de mouvement et des chutes aient été observés. Nous démontrons l’efficacité de la combinaison d’une broche trans-articulaire temporaire et d’une orthèse sur mesure dans le traitement de la luxation congénitale du coude de type III et l’insuffisance de l’augmentation du ligament collatéral seule pour traiter la luxation congénitale du coude de type I avec des déformations de la section antébrachiale.

Message clinique clé:

Ici, nous avons observé qu’une combinaison d’une broche trans-articulaire temporaire et d’une orthèse sur mesure était efficace pour le traitement des luxations congénitales du coude de type III.

(Traduit par Dr Serge Messier)

Neither congenital nor early acquired elbow luxation are common clinical presentations in dogs (1). Congenital elbow luxation is encountered in both males and females and may affect one or both sides of the elbow (2). Three types of congenital elbow luxation are recognized radiographically (1,2): Type I luxation, in which mainly dislocation of the lateral or caudal aspect of the radial head is observed; Type II luxation, which manifests as changes in the humeroulnar joint with lateral dislocation of the proximal ulna; and Type III luxation, described as congenital luxation with displacement of both the radius and ulna, which is often associated with generalized joint laxity (2). Type I congenital elbow luxation is suggested to be inheritable in Pekingese dogs, English bulldogs, Shetland sheepdogs, dachshunds, and Yorkshire terriers (3). Type III congenital elbow luxation has no predilection for a particular breed (1). Treatment for Type III congenital elbow luxation is rarely initiated because it is often associated with multiple skeletal deformities [e.g., split-foot, polyarthrodysplasia, patellar luxation, tail deformity, and avascular necrosis of the femoral head (3–6)] which suggests complete absence of the medial collateral ligament (3,4). However, various treatments have been reported to date, including temporary transarticular pins and/or external splinting (4,7).

Case description

A 10-week-old Yorkshire terrier dog was brought to our veterinary hospital with lameness in the right forelimb. The owner noted that the puppy’s right forelimb had appeared abnormal since the owner adopted the puppy from an animal shelter 2 wk before and that the puppy had never been able to use the limb properly. According to the owner, the same skeletal abnormalities were observed in the entire litter.

On physical examination, the puppy was able to walk/crawl by putting both elbow joints on the ground. This presentation was mostly observed in the right forelimb. More specifically, the right forelimb was held in partial flexion with supination of the antebrachium and with varus deviation of the paw. Crepitus was present on manipulation of the right elbow joint, and the range of motion was reduced for both extension and flexion. Campbell’s test (1) was positive in the right forelimb, demonstrated through oversupination of the antebrachium on the left and right paws. Palpation of the left elbow joint revealed slight lateral subluxation of the radial head. The puppy displayed no pain as either elbow was manipulated.

Radiographic examination of the right elbow joint revealed lateral radio-ulnar displacement relative to the humerus (Figure 1). Slight lateral subluxation of the radial head on the left side was confirmed on radiographic examination. This presentation was suspected to be the result of laxity of the lateral collateral ligament (Figure 2). Procurvatum, distal valgus, and external torsion were observed on both sides of the antebrachium and there was no evidence of degenerative joint disease in either elbow joint on radiographic examination. The puppy’s clinical history and radiographic findings were consistent with a diagnosis of Type III congenital elbow luxation on the right side along with Type I congenital elbow luxation on the left side. The medial and lateral patellar Grade 1 luxations in both stifle joints were left untreated because no symptoms had been observed.

Figure 1.

The mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) radiographic views showing lateral radioulnar displacement relative to the humerus on the right elbow joint, at 15 weeks of age.

Figure 2.

The mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) radiographic views showing slight lateral subluxation of the radial head on the left elbow joint, suspected as laxity of the lateral collateral ligament, at 15 weeks of age.

The only abnormal clinico-pathology finding before surgery was a high serum creatinine concentration (3.5 mg/dL, normal range: 0.5 ~ 1.5 mg/dL). The cause of the creatinine elevation was not determined. Urinalysis was normal, including urine protein/creatinine ratio. There were no abnormal findings in abdominal radiographic or ultrasonographic examinations. After 1 wk of daily subcutaneous fluid therapy, serum creatinine levels improved to 0.4 mg/dL. No increase in serum creatinine was observed thereafter.

Surgical stabilization of the right elbow joint was performed via open reduction and transarticular pin placement at 15 wk of age. The dog was premedicated with atropine sulfate (Nipro ES Pharma, Osaka, Japan), 0.025 mg/kg, SQ. Anesthesia was induced with propofol (Pfizer, New York, New York, USA), 8 mg/kg BW, IV to effect and maintained with 3% isoflurane (Mylan, Southpoint, Pennsylvania, USA), 2.0 L/min oxygen. We also administered morphine sulfate for pain management (Shionogi & Co, Osaka, Japan), 0.25 μg/kg, SQ as a premedication and 0.12 μg/kg, IV every 90 min during surgery (8). The dog was treated with cefazolin (LTL Pharma Co., Tokyo, Japan), 25 mg/kg, IV, which was repeated every 90 min during surgery.

Computed tomography before surgical repair, confirmed a lack of hypoplasia or aplasia of the medial coronoid or anconeal processes. Therefore, it was determined that the right elbow joint could be effectively reduced. The right forelimb was shaved and prepared aseptically. A lateral incision was made in the right elbow joint, extending from the supracondylar crest over the lateral epicondyle of the humerus to the proximal radius. Subcutaneous tissues were incised and bluntly dissected to expose the lateral surface of the elbow. A bipolar incision was made in the deep fascia of the brachium and the antebrachium. The fascia of the triceps brachii muscle was incised, the lateral head of this muscle was pulled caudally, and the anconeus muscle was incised along the lateral humeral epicondyle. A portion of the external humeral condyle was attached to the anconeus muscle in the joint. The ulnaris lateralis muscle tendon was also incised. The olecranon muscle was detached using a periosteal dissector to expose the humeroulnar joint. An arthrotomy was performed. The ulna was manually reduced and held in a reduced position with the joint flexed to approximately 135°. A 0.039-inch diameter (1.0-mm) Kirschner wire was inserted from the caudal cortical bone of the ulna towards the cranial cortical bone of the body of the humerus through the semilunar notch of the ulna using a pin driver. The Kirschner wire was cut to leave 1.0 cm extending outside the ulna effectively performing transarticular pinning between the ulna and the humerus. Another Kirschner wire was inserted slightly distally from the caudal cortical bone of the ulna towards the cranial cortical bone of the lateral humeral condyle through the semilunar notch of the ulna. Maintaining the reduced radioulnar position, a third Kirschner wire was inserted from the caudal cortical bone of the ulna toward the radial head. Immediate postoperative radiographs were obtained while the puppy was under inhalational anesthesia, showing that the congruity of the right elbow joint was improved (Figure 3). The dog was kept in our hospital for 1 wk to ensure cage rest and to confirm the extent of weight-bearing by the affected limb. Buprenorphine (Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Tokyo, Japan); 0.01 mg/kg, q12h for 1 wk was prescribed for pain control.

Figure 3.

Immediate postoperative mediolateral (a) and craniocaudal (b) radiographs of the right elbow joint showing improved congruity, at 15 weeks of age.

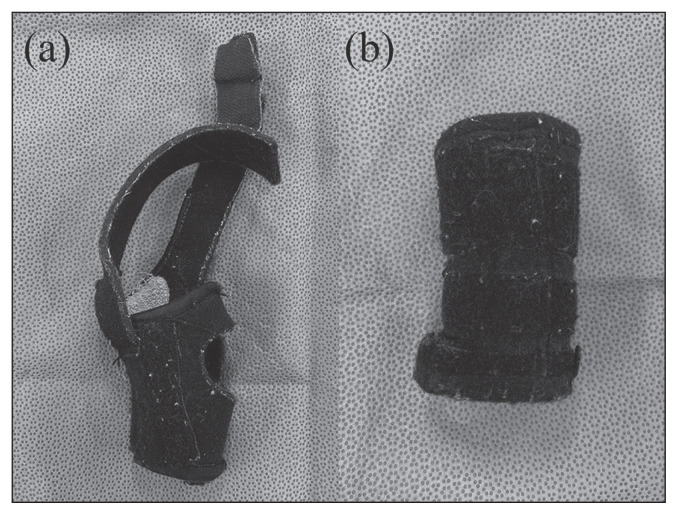

Postoperatively, a spica splint with fiberglass casting tape incorporated along its lateral aspect was applied to the right forelimb, extending from the axilla to the digits. The splint functioned to support the surgical reduction of the joint and to prevent joint motion during the immediate postoperative period until the custom-made orthoses were finalized. Fourteen days after surgery, at 17 weeks of age, the puppy was presented for the application of orthoses, for which an impression had been made in advance, replacing the splint. Subluxation of the humeroulnar and humeroradial joints persisted, although no obvious alterations of the surgical implants were noted. The custom-made orthoses (Toyo-Sogu, Tokyo, Japan) (Figure 4) were applied to the right elbow and the left carpal joints. The orthosis in the right elbow joint functioned to support the surgical reduction of the joint and to restrict motion in the joint during the postoperative period and the orthosis in the left carpal joint functioned to prevent oversupination of the antebrachium. The owner was advised to minimize the puppy’s activity until the transarticular pin was removed. The orthoses were intended to be placed for at least 6 to 8 wk. The owner was instructed to release the orthosis once daily at night, and to check for pressure ulcers or other problems. The transarticular pins were removed 5 wk after surgery, at 20 weeks of age.

Figure 4.

Custom orthoses (Toyo-sogu, Tokyo, Japan) were applied in the right elbow joint (a) and the left carpal joint (b).

Following the removal of the transarticular pins, we noted that, although the flexion range of motion was restricted in the right elbow joint, the puppy was bearing weight sufficiently on the right forelimb with the elbow orthosis at the time of re-examination (49 d after surgery, at 22 weeks of age). The range of motion of the right elbow joint tended to increase over time and there was no recurrent luxation (Figure 5). The puppy experienced no inconvenience when using orthoses for 20 wk after right-side surgery, until 35 wk of age, with a certain restricted exercise. However, the owner reported that the orthoses became smaller as the puppy grew. The owner also reported that, as of 3 mo after surgery, the left forelimb showed noticeable instability in the antebrachium and that falling was frequently seen when the puppy ran. No lameness was observed in the right forelimb.

Figure 5.

Thirty-six days after surgery, there was no recurrent luxation in the right elbow joint at 12 wk after pin removal.

Use of the orthoses was halted and the left elbow lateral collateral ligament was augmented using screws and synthetic ligaments (Fiberwire; Arthrex, Naples, Florida, USA) at 37 weeks of age. The left forelimb was shaved and prepared aseptically. Arthrotomy of the left elbow was performed in the same manner as that of the right elbow. The radial head had been subluxed laterally and easily moved manually, and the lateral collateral ligament was relaxed intraoperatively. The radial head was reduced manually, and screws and washers were placed on the lateral epicondyle and the radial head. Fiber wire synthetic ligaments were constructed using screws and the previously reported washer technique (9).

Immediate postoperative radiographs were obtained while the puppy was under inhalational anesthesia. Congruity of the left elbow joint improved (Figure 6). After surgery, a modified Robert-Jones bandage was applied to the left forelimb, extending from the axilla to the digits. The bandage functioned to support surgical reduction of the joint and to restrict motion in the joint during the immediate postoperative period for 14 d after left-side surgery. The bandage was changed every 2 d for 1 wk. There was no restriction in the extension or flexion of the left elbow and there was oversupination of the antebrachium. The puppy bore full weight on the left forelimb at the time of reexamination 50 d after surgery; although the slight falling resulting from the left forelimb that was observed when the puppy ran, had clearly improved compared to that before surgery.

Figure 6.

Immediate postoperative radiographs showed improved congruity of the left elbow joint.

Discussion

In this case, the right elbow had complete lateral radioulnar luxation with respect to the humerus, consistent with Type III congenital elbow luxation. Combining a temporary transarticular pin and a custom-made orthosis for the treatment of Type III congenital elbow luxation was very effective. Lateral subluxation of the radial head was diagnosed in the left elbow in this case, consistent with Type I congenital elbow luxation. Reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament was performed, and although the symptoms persisted, congruity of the left elbow joint improved.

Some congenital elbow luxation-associated abnormalities include hypoplasia or aplasia of the medial coronoid and anconeal processes (2,3), which did not appear in this case. However, hypoplasia of the supratrochlear foramen, which may occur following congenital elbow luxation (3), was present in this case. If hypoplasia or aplasia of these processes occurs, the elbow joint is more difficult to reduce and stabilize, with a poorer prognosis. Previous case reports and clinical findings suggest that a detailed preoperative evaluation of these areas, e.g., computed tomography examination, is essential to ensure surgical efficacy.

Congenital elbow luxations should be reduced and stabilized early to prevent permanent and severe changes in normal anatomy, such as the articular surface, due to secondary degeneration and remodeling (2,5,7). In this case, however, surgical repair was delayed given high creatinine concentration; the cause of the high creatinine was unclear. Both activity and lameness improved noticeably after surgery, although the right elbow range of flexion remained restricted. The purpose of surgical repair is not only to completely reconstruct the joint, but also to maintain the normal function of the affected limb (7). Therefore, we conclude that the results in this case were satisfactory, and that congenital elbow luxations may generally be effectively treated with open reduction, even when treatment is delayed.

A lack of collateral ligaments can lead to radial subluxation (3), which can be prevented by placing a small Steinmann pin between the radius and ulna (10). However, conducting synostosis of the radius and ulna should be avoided whenever possible, given the high risk of progression of elbow incongruity in rapidly growing dogs (11). This procedure involved surgical repair of the right elbow joint. Fixation was superior when the transarticular pin was driven from the caudal side of the ulna into the humeral diaphysis than when the pin was driven into the distal condyle and the distal metaphysis of the humerus (7). These transarticular pin methods do not cause recurrence luxation and can be used for the treatment of Type III congenital elbow luxations.

Despite good elbow function, persistent subluxation of the humeroulnar and humeroradial joints has been observed in cases managed with temporary placement of a transarticular pin (7,12). Subluxation of the humeroulnar and humeroradial joints was likewise observed in this case after surgery of the right elbow. This case was treated postoperatively with a spica splint and a custom-made orthosis. No obvious subluxation of the ulnar or radial humeral joints was evident 49 d after surgery. Elbow lateral luxation can usually be reduced with flexion and can usually be stabilized by extension (1). In this case, the elbow tended to luxate in the flexion position. Spica splints are generally considered to limit elbow joint flexion after reducing elbow luxation, and elbow orthoses can also be designed to prevent elbow flexion in dogs recovering from luxation of the elbow joint (13). It appears that restricting elbow flexion via a spica splint and orthosis prevented the progression of luxation until the elbow joint was stabilized. A Cavalier King Charles spaniel presenting with Type III congenital elbow luxation was treated with a spica splint which yielded an acceptable outcome (4). A spica splint should be replaced under sedation, whereas custommade orthoses can be placed and removed without sedation.

Long-standing fixation leads to contracture of the joint capsule and surrounding structures, which may limit the elbow’s range of motion (14), as observed in the current case, suggesting the importance of keeping the elbow in a functional position so that the leg retains maximal ability of flexion and extension when the fixation is eventually removed. Concerns regarding use of transarticular pins include: disruption of the physes, implant failure or migration, articular cartilage trauma, and impaired limb growth due to prolonged external coaptation (11). However, in this case, no degenerative changes were noted after surgery. Outcomes following the surgical management of Type I congenital elbow luxation have been inconsistent to date, and the importance of ligament reconstruction is currently unknown (9,11,15). However, an adjunctive ligament reconstruction that restored normal function to the affected limb is described in a previous report (16). Reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament and joint capsule, especially in mild cases, can provide stabilization after reduction (17).

Reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament was performed, as the radial head was easily reduced and the synthetic ligaments prevented oversupination of the left antebrachium. However, some falling was observed when the puppy ran, which could result not only from oversupination, but also from external torsion in the antebrachium.

Although the etiology of radial head luxation is controversial, a widely accepted pathophysiological hypothesis is that impaired growth of the radius and ulna and concomitant ligamentous laxity around the elbow joint are involved in radial head luxation (2,3,10,18–20), most often resulting from premature closure of the distal ulnar physis (21). Lateral luxation of the radial head, therefore, may be caused by premature closure of the distal ulnar physis (17,22,23). In this case, findings suggesting antebrachium deformity were likewise observed, consistent with prior reports. An additional corrective osteotomy of the antebrachium may have improved function. Surgical outcomes do not result in a normal elbow, but usually do provide improved function; however, some degree of luxation and carpal valgus generally persists (1,4,24).

In this case, a fiber wire was used for reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament. Although concerns about infection have been suggested when using fiber wires (25), we used plastic drapes, washed the surgical area frequently, and collected a sample for bacterial culture before closing the surgical site to confirm the absence of obvious bacterial infection. Bacterial culture tests did not detect any bacterial infection.

This case report has some limitations. First, it presents a subjective evaluation of a single case (i.e., not a case series). Second, a more accurate assessment of affected limb function could have been obtained, even within the described clinical evaluations and observations. In general, there is a lack of long-term follow-up for the progression of degenerative joint diseases in the medical literature to date. Congenital elbow luxation diagnoses are established based on clinical signs as well as the early radiographic onset of congenital, which must be differentiated from developmental elbow luxation. As congenital elbow luxation can be hereditary (2), it is important to verify the pedigree of the affected dog. However, the pedigree of the presenting dog and follow-up in other litters were unknown.

We conclude that the combination of a temporary transarticular pin, a spica splint, and custom-made orthoses are effective for the treatment of Type III congenital elbow luxation and that reconstruction of the lateral collateral ligament alone is insufficient for the treatment of Type I congenital elbow luxation accompanied by an antebrachium deformity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Toyo-Sogu Co. for the custom-made orthoses. We also thank the staff of the Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Azabu University for their support. CVJ

Footnotes

Use of this article is limited to a single copy for personal study. Anyone interested in obtaining reprints should contact the CVMA office (hbroughton@cvma-acmv.org) for additional copies or permission to use this material elsewhere.

References

- 1.Decamp CE, Johnston SA, Dejardin LM, Schaefer SL. The elbow joint. In: Decamp CE, Johnston SA, Dejardin LM, Schaefer SL, editors. Handbook of Small Animal Orthopedics and Fracture Repair. 5th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2016. pp. 327–365. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kene ROC, Lee R, Bennett D. The radiological features of congenital elbow luxation/subluxation in the dog. J Small Animal Practice. 1982;23:621–630. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bingel SA, Riser WH. Congenital elbow luxation in the dog. J Small Animal Practice. 1977;18:445–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1977.tb05911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McDonell HL. Unilateral congenital elbow luxation in a Cavalier King Charles Spaniel. Can Vet J. 2004;45:941–943. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Milton JL, Horne RD, Bartels JE, Henderson RA. Congenital elbow luxation in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1979;175:572–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montgomery M, Tomlinson J. Two cases of ectrodactyly and congenital elbow luxation in the dog. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1985;21:781–785. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rahal SC, De Biasi F, Vulcano LC, Neto FJ. Reduction of humeroulnar congenital elbow luxation in 8 dogs by using the transarticular pin. Can Vet J. 2000;41:849–853. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Plumb DC. Plumb’s Veterinary Drug Handbook. 6th ed. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell; 2008. p. 634. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krotscheck U, Böttcher P. Surgical disease of the elbow. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA, editors. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 836–884. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milton JL, Montgomery RD. Congenital elbow dislocations. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract. 1987;17:873–88. doi: 10.1016/s0195-5616(87)50082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark KJ, Jerram RM, Walker AM. Surgical management of suspected congenital luxation of the radial head in three dogs. N Z Vet J. 2010;58:103–109. doi: 10.1080/00480169.2010.65265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Withrow SJ. Management of a congenital elbow luxation by temporary transarticular pinning. Vet Med Small Anim Clin. 1977;72:1597–1602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marcellin-Little DJ. Bandaging, external coaptation, and external devices for companion animals. In: Tobias KM, Johnston SA, editors. Veterinary Surgery: Small Animal. 2nd ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2017. pp. 737–751. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wong K, Trudel G, Laneuville O. Noninflammatory joint contractures arising from immobility: Animal models to future treatments. BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:848290. doi: 10.1155/2015/848290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fitzpatrick N, Yeadon R, Farrell M. Surgical management of radial head luxation in a dog using an external skeletal traction device. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2013;26:140–146. doi: 10.3415/VCOT-11-11-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Spadari A, Romagnoli N, Venturini A. A modified Bell-Tawse proceduter for surgical correction of congenital elbow luxation in a Dalmatian puppy. Vet Comp Orthop Traumatol. 2001;14:210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Campbell JR. Congenital luxation of the elbow of the dog. Vet Annu. 1979;19:229–236. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grøndalen J. Malformation of the elbow joint in an Afghan hound litter. J Small Animal Practice. 1973;14:83–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1973.tb06897.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stevens DR, Sande RD. An elbow dysplasia syndrome in the dog. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1974;165:1065–1069. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell JR. Nonfracture injuries to the canine elbow. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1969;155:735–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramadan RO, Vaughan LC. Premature closure of the distal ulnar growth plate in dogs–A review of 58 cases. J Small Animal Practice. 1978;19:647–667. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-5827.1978.tb05554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Heidenreich DC, Fourie Y, Barreau P. Presumptive congenital radial head sub-luxation in a Shih Tzu: Successful management by radial head ostectomy. J Small Anim Pract. 2015;56:626–629. doi: 10.1111/jsap.12353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harasen G. Congenital radial head luxation in a bulldog puppy. Can Vet J. 2012;53:439–441. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fafard AR. Unilateral congenital elbow luxation in a dachshund. Can Vet J. 2006;47:909–912. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Von Pfeil DJF, Kowaleski MP, Glassman M, Dejardin LM. Results of a survey of veterinary orthopedic society members on the preferred method for treating cranial cruciate ligament rupture in dogs weighing more than 15 kilograms (33 pounds) J Am Vet Med Assoc. 2018;253:586–597. doi: 10.2460/javma.253.5.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]