Abstract

Background

To minimize the spread of Coronavirus Disease-2019, Saudi Arabia imposed a nationwide lockdown for over 6 weeks. We examined the impact of lockdown on glycemic control in individuals with type 1 diabetes (T1D) using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM); and assessed whether changes in glycemic control differ between those who attended a telemedicine visit during lockdown versus those who did not.

Materials and Methods

Flash CGM data from 101 individuals with T1D were retrospectively evaluated. Participants were categorized into two groups: Attended a telemedicine visit during lockdown (n = 61) or did not attend (n = 40). Changes in CGM metrics from the last 2 weeks pre-lockdown period (Feb 25 - March 9, 2020) to the last 2 weeks of complete lockdown period (April 7–20, 2020) were examined in the two groups.

Results

Those who attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period had a significant improvement in the following CGM metrics by the end of lockdown: Average glucose (from 180 to 159 mg/dl, p < 0.01), glycemic management indicator (from 7.7 to 7.2%, p = 0.03), time in range (from 46 to 55%, p < 0.01), and time above range (from 48 to 35%, p < 0.01) without significant changes in time below range, number of daily scans or hypoglycemic events, and other indices. In contrast, there were no significant changes in any of the CGM metrics during lockdown in those who did not attend telemedicine.

Conclusions

A six-week lockdown did not worsen, nor improve, glycemic control in individuals with T1D who did not attend a telemedicine visit. Whereas those who attended a telemedicine visit had a significant improvement in glycemic metrics; supporting the clinical effectiveness of telemedicine in diabetes care.

Keywords: Telemedicine, Type 1 Diabetes, Lockdown, Continuous Glucose Monitoring, COVID-19

1. Introduction

Maintaining a good glycemic control in people with type 1 diabetes (T1D) is often challenging during “ordinary” times; and becomes more challenging and important during times of uncertainty and physical and mental distress. Glucose levels in people with T1D are affected by many factors including levels of physical activity, eating patterns, physical and mental health, frequency of glucose monitoring, adherence to insulin therapy, and availability of an uninterrupted access to healthcare providers (HCPs) [1], [2]. The unprecedented Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic has caused abrupt and unplanned-for changes in almost all of these factors; and people living with T1D were among those impacted the most by this pandemic. Furthermore, many countries have implemented precautionary measures including closures of schools and non-essential businesses, cancellations of routine (non-urgent) clinic appointments, and lockdowns, to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 [3]. Saudi Arabia has implemented one of the longest and most strictly enforced nationwide lockdowns that lasted for a total of 3 months. Some parts of the countries had a complete lockdown (i.e. 24 hr/day) that lasted for over a month; whereas others had approximately 3 weeks of complete lockdown. The complete lockdown was preceded and followed by a total of 8 weeks of partial lockdown (i.e. at least 15 hrs/day) [4], [5]. Recent studies have shown a negative impact of lockdown on health behaviors in people with diabetes [6], [7], [8]. Therefore, it is hypothesized that a prolonged lockdown, such as the one implemented in Saudi Arabia, would likely result in worsening of glycemic control in people living with diabetes.

In addition, many people with T1D lost access to their HCPs during the COVID-19 outbreak as a result of the lockdown and cancellation of routine clinic appointments. Though some patients with T1D were able to utilize telemedicine to restore communications with their HCPs during this difficult time, telemedicine was not available for the majority of people with T1D, particularly those who live in parts of the world where telemedicine is not well-established [9], [10]. Fortunately, the recent improvements in diabetes technologies, including the availability of continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) devices and blood glucose meters with remote data sharing capabilities, have made the transition to telemedicine during the COVID-19 outbreak a relatively smooth process for many clinics. We have recently described our experience with implementing a simplified Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic for people with diabetes living in Saudi Arabia, where diabetes is highly prevalent and telemedicine is not well-established. We showed that a Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic, utilizing simple technological tools widely available to most people with diabetes and HCPs such as smart phones and virtual communication applications, is not only feasible but also associated with high patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction [11]. The clinical effectiveness of such a simplified diabetes telemedicine clinic remains unknown, particularly when implemented in areas where telemedicine was not well-established prior to the COVID-19 pandemic.

In this study, we evaluate the impact of a six-week lockdown on CGM glycemic indices in people with T1D. We also examine the clinical effectiveness of a simplified diabetes telemedicine clinic, that was rapidly implemented at the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak in Saudi Arabia utilizing technological tools that are widely available for most people with T1D and HCPs.

2. Subjects and methods

2.1. Study design and participants

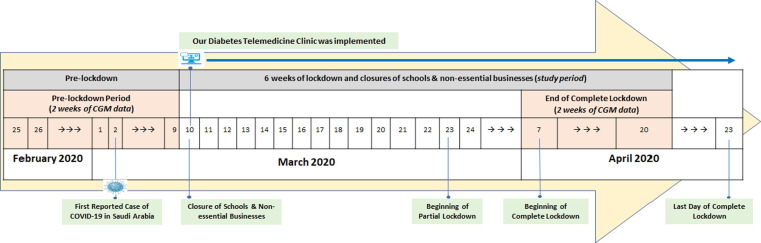

A retrospective analysis of FreeStyle Libre CGM data from 101 individuals with T1D who attended the Specialized Diabetes Clinic at King Saud University Medical City in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and had their data remotely shared with our clinic using Libreview, a web-based cloud system. Participants who did not have their CGM data shared with our clinic during these periods were excluded. The timeline of the COVID-19 outbreak and important dates related to the outbreak and lockdown in Saudi Arabia are shown in Fig. 1 . A nationwide closure of schools and non-essential businesses was ordered on March 10, 2020; followed by a nationwide partial lockdown (i.e. from 3 PM to 6 AM) starting on March 24, 2020 that was then upgraded to a nationwide complete lockdown (i.e. a 24-hr lockdown) from April 7 to April 23, 2020. After that, the lockdown was downgraded and became a partial lockdown again which lasted for almost two months (from April 24 to June 21, 2020). In this study, we examined changes in CGM metrics from the “Pre-lockdown” period (i.e. February 25 to March 9) to the “Complete Lockdown” period (i.e. April 7 to 20). The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at King Saud University.

Fig. 1.

A Nationwide closure of schools and non-essential businesses was ordered on March 10, 2020; followed by a partial lockdown starting on March 24, 2020 that was upgraded to a complete lockdown from April 7 to April 23, 2020. Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic was implemented on March 10, 2020..

2.2. Assessment of glycemic outcomes and covariates

The following CGM metrics were evaluated in all the study participants both pre-lockdown and at the end of the complete lockdown period: Average glucose, coefficient of variation (CV), glucose management indicator (GMI), TIR (time in range 70–180 mg/dl), TAR (time above range > 180 mg/dl), TBR (time below range < 70 mg/dl), CGM active time, and number of daily scans. In addition, the following demographic and clinical data were collected from the electronic medical records: Age, sex, diabetes duration, body mass index, hemoglobin A1C prior to the lockdown, and mode of insulin therapy.

2.3. Telemedicine clinic visit

We also collected data on whether the study participants attended a virtual visit with their diabetes care providers during the lockdown period or not; as this could be a potential predictor of changes in CGM metrics during lockdown. Study participants who had at least one virtual visit to our Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic during the lockdown period were considered in the “Telemedicine Visit” group; whereas, those who had no virtual visit during the lockdown were considered in the “No Telemedicine Visit” group. The detailed protocol of our Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic has been recently described in another paper [11]. Briefly, people with T1D were eligible to be seen in our Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic during the lockdown period if they had already been scheduled for a routine follow-up visit from prior to the pandemic and had any of the following: A1C of ≥ 9%, >1 reported hypoglycemic event/week, were planning to fast during the month of Ramadan, or requested to be seen virtually. All other people with T1D, who did not meet any of these criteria, were offered the option to postpone their clinic visit to 3 months.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Variable distributions were examined using Shapiro-Wilk test and visual examination of histograms. The non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR); whereas, categorical variables were presented as percentages. Baseline characteristics were compared between those who had a telemedicine visit versus those who didn’t have any visit during the lockdown period using Kruskal-Wallis test for the non-normally distributed continuous variables and chi-squared tests of homogeneity for categorical variables. The changes in CGM glycemic metrics within each study group over the six-week lockdown period were examined using Wilcoxon signed rank test. All significance testing was 2-tailed with α of 0.05, and data were analyzed using Stata Statistical Software (release 15).

3. Results

3.1. Baseline characteristics

A total of 101 individuals with T1D were included in the study, of whom 55% were women and 60% attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period. The median age of the study participants was 23 years with a median diabetes duration of 7 years and hemoglobin A1C of 8.3% at baseline. No significant differences were noted in age, gender, diabetes duration, BMI, baseline hemoglobin A1C, total daily dose of insulin, mode of insulin therapy, or prevalence of diabetic complications between those who attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period and those who did not (all p values > 0.05) (Table 1 ). However, those who attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period had a higher average sensor glucose, GMI, and TAR at baseline compared to those who did not attend a telemedicine visit (180 vs 159.5 mg/dl, p = 0.02; 7.7 vs 7.25%, p = 0.05; 48 vs 35%, p = 0.01; respectively). These differences are likely due to the protocol of our telemedicine clinic that prioritized patients with worse glucose control for a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period. No significant differences were noted in any of the other CGM metrics, including CGM active time and number of daily scans, at baseline between the two groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of study participants (n = 101).

| Characteristic | All Study Participants (n = 101) |

Telemedicine visit during the lockdown period |

P value † |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No (n = 40) |

Yes (n = 61) |

|||

| Age, median (25th, 75th percentile), years | 23 (18,28) | 27 (19,31.5) | 22 (17,26) | 0.08 |

| Gender | ||||

| Women (%) | 54.46 | 47.50 | 59.02 | 0.18 |

| Men (%) | 45.54 | 52.50 | 40.98 | |

| Diabetes duration, median (25th, 75th percentile), years | 7(3,16) | 10 (4,17.5) | 7 (3,13) | 0.12 |

| Body mass index, median (25th, 75th percentile), kg/m2 | 23.66 (21.36,27.66) |

23.74 (21.285,27.565) | 23.66 (21.36,27.66) | 0.79 |

| hemoglobin A1C, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 8.3 (7.7,9.9) | 8.2 (7.5,10.6) | 8.3 (7.8,9.7) | 0.66 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 10 (11) | 4 (12) | 6 (10) | 0.77 |

| Celiac disease, n (%) | 8 (9) | 3 (10) | 5 (9) | 0.83 |

| Dyslipidemia, n (%) | 8 (9) | 2 (6) | 6 (10) | 0.50 |

| HTN, n (%) | 30 (31) | 7 (19) | 23 (38) | 0.05 |

| Diabetic Complications | ||||

| Nephropathy, n (%) | 10 (10) | 3 (8) | 7 (12) | 0.59 |

| Albuminuria, n (%) | 15 (16) | 4 (11) | 11 (18) | 0.35 |

| Retinopathy, n (%) | 7 (13) | 4 (19) | 3 (9) | 0.29 |

| Mode of Insulin Therapy | ||||

| Using MDI (%)* | 71.43 | 70.27 | 72.13 | 0.11 |

| Using CSII (%)* | 28.57 | 29.73 | 27.87 | |

| Total Daily Dose of Insulin, median (25th, 75th percentile), Units/day | 50 (37.5, 68) | 44.5 (31.5, 68) | 51.5 (40, 68) | 0.12 |

| CGM metrics (pre-lockdown) * | ||||

| Average sensor glucose, median (25th, 75th percentile), mg/dl | 173 (145,204) | 159.5 (138,180.5) | 180 (154,208) | 0.02* |

| GMI, median (25th, 75th percentile), %* | 7.5 (6.8,8.3) | 7.25 (6.65,7.9) | 7.7 (7,8.4) | 0.05 |

| TIR, median (25th, 75th percentile), %* | 52 (35,65) | 58 (45.5,73.5) | 46 (34,61) | 0.01* |

| TAR, median (25th, 75th percentile), %* | 43 (23,60) | 35 (19.5,48.5) | 48 (33,63) | 0.01* |

| TBR, median (25th, 75th percentile), %* | 4 (2,7) | 4.5 (2.5,8.5) | 3 (2,7) | 0.16 |

| Coefficient of variation, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 37.7 (33,42.1) | 37.2 (33.8,41.25) | 37.8 (31.2,42.8) | 0.90 |

| CGM active time, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 92 (74,98) | 93.5 (74.5,100) | 92 (74,98) | 0.22 |

| Number of daily scans, median (25th, 75th percentile), n/day | 10 (6,14) | 10.5 (6,14) | 9 (6,14) | 0.39 |

Abbreviations: MDI, multiple daily injection; CSII, continuous subcutaneous insulin infusion; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring; GMI, glucose management indicator; TIR, time in range; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range.

P value examining the difference between those who attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period versus those who did not.

3.2. Impact of lockdown on glycemic control and CGM use

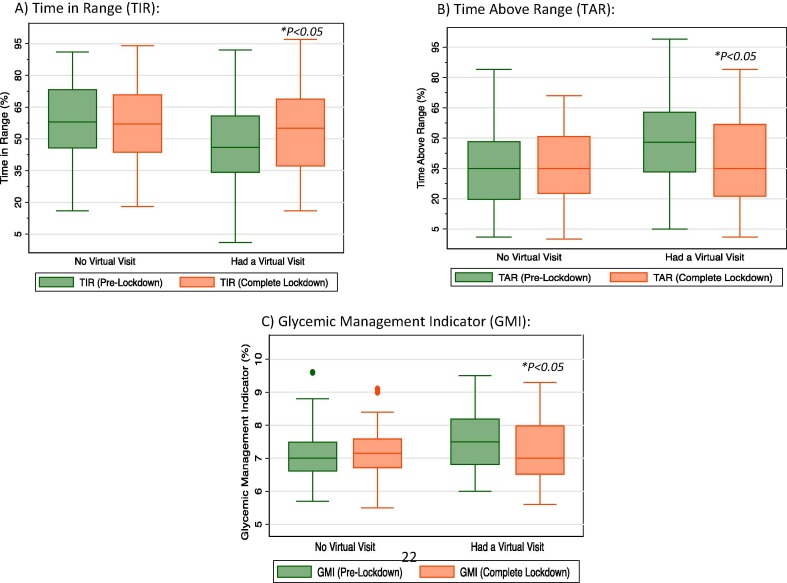

Overall, the six-week lockdown period was accompanied by an improvement in average glucose (from 173 to 159 mg/dl; P = 0.01) and TAR (from 43 to 35%; P = 0.01) in people with T1D in our study (Table 2 ). When stratified by whether or not they attended a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period, people with T1D who attended a telemedicine visit had statistically significant improvements in average glucose (from 180 to 159 mg/dl; P < 0.01), GMI (from 7.7 to 7.2%; P = 0.03), TIR (from 46 to 55%; P < 0.01), and TAR (from 48 to 35%; P < 0.01) (Fig. 2 ). No significant changes were noted in any of the other CGM metrics including TBR or low glucose events. In those who did not attend a telemedicine visit during lockdown, no significant changes were noted in any of the glycemic indices on CGM (Table 2). Similarly, the frequency of CGM use remained unchanged from baseline to the end of the lockdown period in the two groups with an overall median CGM active time of 92% at baseline and 90% at the end of the lockdown period (P = 0.56) and a median number of daily scans of 10 at baseline and 10 at the end of the lockdown (P = 0.45) (Table 2). No cases of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) or severe hypoglycemic events have been reported in the participants’ medical records during the study period.

Table 2.

Changes in various CGM metrics during the lockdown period compared to those in the period before lockdown in people with diabetes who had a telemedicine visit and those who didn’t have a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period.*

| Variable | All (n = 101) |

No telemedicine visit (n = 40) |

Had telemedicine visit (n = 61) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before lockdown |

During lockdown |

P value† | Before lockdown |

During lockdown |

P value† | Before lockdown |

During lockdown |

P value† | |

| Average glucose, median (25th, 75th), mg/dl | 173 (145,204) | 159 (137,194) | 0.01 | 159.5 (138,180.5) | 160 (140,188) | 0.99 | 180 (154,208) | 159 (135,199) | <0.01 |

| GMI, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 7.5 (6.8,8.3) | 7.2 (6.6,8.4) | 0.11 | 7.3 (6.7,7.9) | 7.2 (6.7,8.0) | 0.65 | 7.7 (7.0,8.4) | 7.2 (6.6,8.5) | 0.02 |

| TIR, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 52 (35,65) | 56 (38,69) | 0.10 | 58 (45.5,73.5) | 57 (43.5,71) | 0.20 | 46 (34,61) | 55 (37,69) | <0.01 |

| TAR, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 43 (23,60) | 35 (22,56) | 0.01 | 35 (19.5,48.5) | 35 (22.5,51) | 0.83 | 48 (33,63) | 35 (21,57) | <0.01 |

| TBR, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 4 (2,7) | 5 (2,10) | 0.05 | 4.5 (2.5,8.5) | 5.5 (2,10) | 0.40 | 3 (2,7) | 5 (2,8) | 0.06 |

| CV, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 37.7 (33,42.1) | 38.9 (33.3,44.8) | 0.10 | 37.2 (33.8,41.25) | 39.4 (34.05,44.7) | 0.11 | 37.8 (31.2,42.8) | 37.7 (33,44.8) | 0.33 |

| CGM active time, median (25th, 75th percentile), % | 92 (74,98) | 90 (68,99) | 0.56 | 93.5 (74.5,100) | 91.5 (66.5,98.5) | 0.24 | 92 (74,98) | 90 (69,99) | 0.86 |

| Daily scans, median (25th, 75th percentile), n/day | 10 (6,14) | 10 (5,15) | 0.45 | 10.5 (6,14) | 8.5 (4,14.5) | 0.40 | 9 (6,13) | 11 (6,15) | 0.09 |

| Low glucose events, median (25th, 75th percentile), n/day | 8 (3,14) | 8 (3,14) | 0.76 | 11 (5,16) | 8 (3.5,15) | 0.28 | 6 (2,13) | 8 (3,18) | 0.22 |

Abbreviations: GMI, glucose management indicator; TIR, time in range; TAR, time above range; TBR, time below range; CV, Coefficient of variation; CGM, continuous glucose monitoring.

Data are presented as median and interquartile ranges.

P value examining the difference in glycemic indices by period (before lockdown vs. during lockdown) using Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed-rank test in those who had a telemedicine visit and those who did not have a telemedicine visit during the lockdown period.

Fig. 2.

Changes in glycemic indices from pre-lockdown to end of lockdown in those who attended a telemedicine visit versus those who did not. A) Changes in Time In Range (TIR); B) Changes in Time Above Range (TAR); C) Changes in Glycemic Management Indicator (GMI). Abbreviations: TIR, time in range; TAR, time above range; GMI, glucose management indicator. * P < 0.05 comparing glycemic indices at the end-of-lockdown period to the pre-lockdown period.

4. Discussion

In this study, we showed that telemedicine use, during the lockdown period in Saudi Arabia, was associated with a significant improvement in several glycemic indices in people with T1D, including an increase in TIR by 9% (i.e. 2.25 h/day) and a reduction in TAR by 13% (i.e. 3.25 h/day). These changes in TIR and TAR are both statistically and clinically significant; as they represent an approximate decrease in hemoglobin A1C of 0.8% [12], [13], [14], [15], [16], [17], [18], [19]. Each 10% increase in TIR has been associated with a reduction in risk of retinopathy by 36% and microalbuminuria by 60% in people with T1D [20]. An equivalent reduction in A1C in people with type 2 diabetes has also been associated with reduced relative risks of all-cause mortality by 14%, death due to diabetes by 21%, any end point related to diabetes by 21%, fatal and non-fatal myocardial infarction by 14%, heart failure by 16%, fatal and non-fatal stroke 12%, and microvascular endpoints by 31% over 10 years [21], [22], [23].

We also showed that lockdown was not associated with worsening nor improvement of glycemic control in the subgroup of people with T1D who did not attend a telemedicine visit, a finding that warrants further discussion. Recent reports have shown similar findings in people with T1D during lockdown in Italy and Spain [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. However, no previous study has reported the changes in glycemic control in people with T1D who attended a diabetes telemedicine clinic during lockdown versus those who did not. Moreover, the lockdown in Saudi Arabia was one of the longest and most strictly imposed lockdowns in the world as it lasted for almost 3 months and violators could face a fine of $2,665, in addition to jail for repeat offenders [4]. The lack of worsening of glucose control during lockdown in those who did not attend a telemedicine visit was likely due to several factors. It is likely that being confined to home during lockdown has eliminated factors that typically contribute to the glycemic fluctuations seen in people living with T1D, such as eating at restaurants, physical activities and exercise, and going to work or schools [24], [25], [26], [27], [28], [29]. It is also possible that people with diabetes were able to devote more time to improve their glucose control during the COVID-19 lockdown as several reports have linked poor glucose control to risk of mortality from COVID-19 [30], [31], [32]. This is supported by the remarkably high CGM active time in the two groups in our study including those who attended or did not attend a telemedicine visit during lockdown.

The use of diabetes technology empowers people with T1D and has been of tremendous value during the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown. CGM use increases the patients’ awareness of their glucose levels, compared to relying on self-monitored blood glucose, and allows them to make frequent decisions about insulin dosing and seek advice from their HCPs whenever needed. This usually results in safely achieving glycemic goals including a greater time with glucose levels at target (i.e. 70 to 180 mg/dl) and less times in hyper- and hypoglycemia. The remote glucose data sharing offered by these devices has also been key in the success of diabetes telemedicine clinics during the COVID-19 outbreak, including at our center, as it facilitates remote diabetes management, reduces patients’ exposure to COVID-19, and preserves personal protective equipment [11]. Multiple studies have reported positive perception of telemedicine in people with T1D during COVID-19 outbreak; and we have recently reported high patients’ and physicians’ satisfaction with our Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic during the COVID-19 outbreak [11], [24], [33], [34], [35].

Our study is unique as it shows the clinical effectiveness of a simplified diabetes telemedicine clinic that was rapidly implemented during the COVID-19 outbreak, utilizing technological tools that are widely available to patients and HCPs. The implications of these findings are substantial, particularly for parts of the world where diabetes is highly prevalent and telemedicine is not well-established (e.g. the Middle East and South Asia). We are not aware of similar studies examining the clinical effectiveness of diabetes telemedicine clinics during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, we used CGM data to assess glycemic changes during lockdown which provided reliable and detailed information that otherwise would have been difficult to obtain using self-monitoring of blood glucose.

The limitations of our study include the retrospective nature of the study and lack of information on physical activity and dietary habits of the study participants during the lockdown period. In addition, our findings are limited to those who are actively using CGM and remotely sharing their data with HCPs which may impact the generalizability of our findings.

5. Conclusion

Our study shows an improvement in glycemic control in people with T1D who attended a simplified diabetes telemedicine clinic, which highlights the feasibility and clinical effectiveness of this model of care during times of pandemics and disasters. Studies are needed to examine the sustainability and effectiveness of such a simplified diabetes telemedicine clinic beyond times of disasters. We also showed that the lockdown and slowing down of daily life had no immediate negative impact on glycemic control in people with T1D; however, this also needs to be examined in studies with longer duration of follow up.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the diabetes educators (Aeshah Almutairi and Eman Mohamed) and dietitians (Sara Almuammar and Nouf Alzuaibi) at the Specialized Diabetes Clinics at King Saud University-Medical City on their contribution to the Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic.

Funding source

This project has been supported by the College of Medicine, Deanship of Scientific Research at King Saud University, Saudi Arabia.

References

- 1.Agiostratidou G, Anhalt H, Ball D, et al. Standardizing clinically meaningful outcome measures beyond HbA1c for type 1 diabetes: a consensus report of the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, the American Association of Diabetes Educators, the American Diabetes Association, the Endocrine Society, JDRF International, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, the Pediatric Endocrine Society, and the T1D Exchange. Diabetes Care 2017;40:1622–1630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.American Diabetes Association. 7. Diabetes Technology: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2020. Diabetes Care 2020;43(Suppl. 1):S77–S88 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Wamsley, L. Life during coronavirus: what different countries are doing to stop the spread. The Coronavirus Crisis; 2020. https://www.npr.org/sections/goatsandsoda/2020/03/10/813794446/life-during-coronavirus-what-different-countries-are-doing-to-stop-the-spread. Accessed September 4, 2020.

- 4.MOH News - COVID-19 Monitoring Committee Holds Its 35th Meeting https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/Ministry/MediaCenter/News/Pages/News-2020-03-25-004.aspx

- 5.Saudi Press Agency . Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques issues curfew order to limit spread of Novel Coronavirus from seven in the evening until six in the morning for 21 days starting in the evening of Monday 23 March. https://www.spa.gov.sa/2050402. Accessed September 4, 2020.

- 6.Khader M.A., Jabeen T., Namoju R. A cross sectional study reveals severe disruption in glycemic control in people with diabetes during and after lockdown in India. Diabet Metabolic Syndrome Clin Res Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ghosh A., Arora B., Gupta R., Anoop S., Misra A. Effects of nationwide lockdown during COVID-19 epidemic on lifestyle and other medical issues of patients with type 2 diabetes in north India. Diabet Metabolic Syndrome Clin Res Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.05.044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ruiz-Roso M.B., Knott-Torcal C., Matilla-Escalante D.C., Garcimartín A., Sampedro-Nuñez M.A., Dávalos A., et al. COVID-19 Lockdown and Changes of the Dietary Pattern and Physical Activity Habits in a Cohort of Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Nutrients. 2020;12(8):2327. doi: 10.3390/nu12082327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghosh A., Gupta R., Misra A. Telemedicine for diabetes care in India during COVID19 pandemic and national lockdown period: guidelines for physicians. Diabet Metab Syndr. 2020;14(4):273–276. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Malasanos T., Ramnitz M. Diabetes clinic at a distance: telemedicine bridges the gap. Diabet Spectr. 2013;26(4):226–231. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Al-Sofiani, M. E., Alyusuf, E. Y., Alharthi, S., Alguwaihes, A. M., Al-Khalifah, R., & Alfadda, A. (2020). Rapid Implementation of a Diabetes Telemedicine Clinic During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Outbreak: Our Protocol, Experience, and Satisfaction Reports in Saudi Arabia. Journal of diabetes science and technology, 1932296820947094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Battelino T., Danne T., Bergenstal R.M., Amiel S.A., Beck R., Biester T., et al. Clinical targets for continuous glucose monitoring data interpretation: recommendations from the international consensus on time in range. Diabet Care. 2019;42(8):1593–1603. doi: 10.2337/dci19-0028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vigersky R.A., McMahon C. The relationship of hemoglobin A1C to time-in-range in patients with diabetes. Diabet Technol Ther. 2019;21(2):81–85. doi: 10.1089/dia.2018.0310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beck R.W., Bergenstal R.M., Cheng P., Kollman C., Carlson A.L., Johnson M.L., et al. The relationships between time in range, hyperglycemia metrics, and HbA1c. J Diabet Sci Technol. 2019;13(4):614–626. doi: 10.1177/1932296818822496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabris C., Heinemann L., Beck R.W., Cobelli C., Kovatchev B. Estimation of Hemoglobin A1c from Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data in Individuals with type 1 diabetes: Is Time in Range All We Need? Diabet Technol Ther. 2020;ja doi: 10.1089/dia.2020.0236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The effect of intensive treatment of diabetes on the development and progression of long-term complications in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. N Engl J Med. 1993 Sep 30;329(14):977–86. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group. The relationship of glycemic exposure (HbA1c) to the risk of development and progression of retinopathy in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes. 1995 Aug;44(8):968–83. [PubMed]

- 18.American Diabetes Association. 6. Glycemic targets: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetesd2020. Diabetes Care 2020; 43(Suppl. 1):S66–S76. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Type 2 diabetes: newer agents for blood glucose control in type 2 diabetes; 2012. http://www. nice.org.uk/nicemedia/live/12165/44318/44318.pdf. [PubMed]

- 20.Beck R.W., Bergenstal R.M., Riddlesworth T.D., Kollman C., Li Z., Brown A.S., et al. Validation of time in range as an outcome measure for diabetes clinical trials. Diabet Care. 2019;42(3):400–405. doi: 10.2337/dc18-1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Selvin E., Marinopoulos S., Berkenblit G., Rami T., Brancati F.L., Powe N.R., et al. Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):421–431. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cavero-Redondo I., Peleteiro B., Álvarez-Bueno C., Rodriguez-Artalejo F., Martínez-Vizcaíno V. Glycated haemoglobin A1c as a risk factor of cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause mortality in diabetic and non-diabetic populations: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ open. 2017;7(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stratton I.M., Adler A.I., Neil H.A.W., Matthews D.R., Manley S.E., Cull C.A., et al. Association of glycaemia with macrovascular and microvascular complications of type 2 diabetes (UKPDS 35): prospective observational study. BMJ. 2000;321(7258):405–412. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7258.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fernández E., Cortazar A., Bellido V. Diabetes research and clinical practice. 2020. Impact of COVID-19 lockdown on glycemic control in patients with type 1 diabetes; p. 108348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bonora B.M., Boscari F., Avogaro A., Bruttomesso D., Fadini G.P. Glycaemic Control Among People with Type 1 Diabetes During Lockdown for the SARS-CoV-2 Outbreak in Italy. Diabetes. Therapy. 2020;1 doi: 10.1007/s13300-020-00829-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maddaloni E., Coraggio L., Pieralice S., Carlone A., Pozzilli P., Buzzetti R. Effects of COVID-19 Lockdown on Glucose Control: Continuous Glucose Monitoring Data From People With Diabetes on Intensive Insulin Therapy. Diabet Care. 2020 doi: 10.2337/dc20-0954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Capaldo B., Annuzzi G., Creanza A., Giglio C., De Angelis R., Lupoli R., et al. Blood Glucose Control During Lockdown for COVID-19: CGM Metrics in Italian Adults With Type 1 Diabetes. Diabet Care. 2020;43(8):e88–e89. doi: 10.2337/dc20-1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mesa, A., Viñals, C., Pueyo, I., Roca, D., Vidal, M., Giménez, M., & Conget, I., 2020. The impact of strict COVID-19 lockdown in Spain on glycemic profiles in patients with type 1 Diabetes prone to hypoglycemia using standalone continuous glucose monitoring. diabetes research and clinical practice, 108354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Cotovad-Bellas L., Tejera-Pérez C., Prieto-Tenreiro A., Sánchez-Bao A., Bellido-Guerrero D. The challenge of diabetes home control in COVID-19 times: proof is in the pudding. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2020;108379 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu L., She Z.G., Cheng X., Qin J.J., Zhang X.J., Cai J., et al. Association of blood glucose control and outcomes in patients with COVID-19 and pre-existing type 2 diabetes. Cell Metab. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gupta R., Ghosh A., Singh A.K., Misra A. Clinical considerations for patients with diabetes in times of COVID-19 epidemic. Diabet Metab Syndr. 2020;14(3):211–212. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., et al. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ghosh A., Gupta R., Misra A. Telemedicine for diabetes care in India during COVID19 pandemic and national lockdown period: guidelines for physicians. Diabet Metabolic Syndrome Clin Res Rev. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Odeh R., Gharaibeh L., Daher A., Kussad S., Alassaf A. Caring for a Child with Type 1 Diabetes During COVID-19 lockdown in a developing country: Challenges and Parents’ Perspectives on the Use of Telemedicine. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2020;108393 doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2020.108393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Anjana, R. M., Pradeepa, R., Deepa, M., JEBARANI, S., Venkatesan, U., Parvathi, S. J., ... & Rani, C. S. (2020). ACCEPTABILITY AND UTILISATION OF NEWER TECHNOLOGIES AND EFFECTS ON GLYCEMIC CONTROL IN TYPE 2 DIABETES–LESSONS LEARNT FROM LOCKDOWN. Diabetes Technology and Therapeutics, (ja). [DOI] [PubMed]