Abstract

Objective

Smoking rates among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) exceed those in the general population. This study identified smoking cessation strategies used in patients with RA and synthesized data on their effects.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review of studies that reported effects of interventions for smoking cessation in patients with RA. We searched 5 electronic databases until March 2022. Screening, quality appraisal, and data collection were done independently by 2 reviewers.

Results

We included 18 studies reporting interventions for patients or providers: 14 evaluated strategies for patients (5 education on cardiovascular risk factors including smoking, 3 educational interventions on smoking cessation alone, 3 education with nicotine replacement and counseling, and 1 study each: education with nicotine replacement, counseling sessions alone, and a social marketing campaign). Smoking cessation rates ranged from 4% (95% CI: 2%-6%, 24 to 48 weeks) for cardiovascular risk education to 43% (95% CI: 21%-67%, 104 weeks) for counseling sessions alone. The pooled cessation rate for all interventions was 22% (95% CI: 8%-41%, 4 weeks to 104 weeks; 9 studies). Four interventions trained providers to ascertain smoking status and provide referrals for smoking cessation. The pooled rates of referrals to quit services increased from 5% in pre-implementation populations to 70% in post-implementation populations.

Conclusion

Studies varied in patient characteristics, the interventions used, and their implementation structure. Only 3 studies were controlled clinical trials. Additional controlled studies are needed to determine best practices for smoking cessation for patients with RA.

Introduction

Smoking is the leading cause of preventable disease. More than 8 million people a year die from diseases related to tobacco use [1]. In 2020, 22% of the world population (approximately 1.3 billion) were current tobacco users [2]. Smoking thus poses a great global economic burden, leading to an annual net loss equivalent to 1.8% of the gross domestic product in the world, owing in large part to lost productivity and increased use of health services [3].

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic condition that typically starts in middle-age and is slightly more frequent in women. The disease has a major impact on quality of life. It is associated with significant comorbidities and early mortality. No curative therapy is available, and in most cases, treatment is required for life. It affects approximately 1% of the global population and poses a great economic burden to society [4,5].

Smoking rates among patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) have been reported to be as high as 30%, exceeding the overall smoking rates reported in general populations [6,7]. Previous epidemiological studies have identified smoking as an important risk factor for RA [8–10]. The risk has been estimated 40% higher among ever smokers compared to never smokers [8]. In 2001, a study reported more than 65% of people living with RA have smoked cigarettes [11]. By 2016, this number had increased to more than 80% [12]. Furthermore, evidence suggest that half of the patients with RA are current smokers at the time of disease onset [11] and up to 26% continue to smoke despite the risk for increased RA complications, hospitalizations due to cardiovascular disease and respiratory tract infections, osteoporosis, and poor response to treatment [13,14]. Factors associated with smoking persistence in patients with RA are thought to be a combination of biological, psychological and social factors including managing RA pain, using smoking as a coping strategy, behavior carried from adolescence, and/or limited knowledge about the effects of smoking on the disease [15].

Current guidelines on smoking cessation recommend clinicians to ask about tobacco use, advise them to stop using tobacco, and provide behavioral intervention (i.e., counseling) in addition to approved pharmacotherapy for cessation [16]. For patients with RA, the benefits of smoking cessation are numerous [17] including slowing down the progression of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [18], reduced risk of fractures after 10 years of quitting [19], risk of dying from lung cancer halved within ten years [20], the risk of hospitalization for cardiovascular events or respiratory tract infections decreasing for each additional year of smoking cessation [14], and reduced mortality risk within four years [21]. Immediate health benefits have also been reported such as improved blood pressure and lung function [22,23], improved disease activity, better response to RA treatment, reduced infective risks of immunosuppressive therapy, and improved success of medication dose reduction [17]. However, despite current guidelines on smoking cessation, only about 10% of rheumatology visits with patients who smoke include documentation of cessation counseling or follow-up advice [24]. The purpose of this systematic review of the literature was to identify smoking cessation strategies used in patients with RA and to synthesize data on smoking cessation outcomes, referrals to quit services, knowledge about cessation benefits, and health outcomes.

Methods

Registration

This systematic review was conducted following Cochrane methodological standards [25], and results were reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement [26]. The protocol of this systematic review was submitted to the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) under registration number CRD42020215287 (https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=215287).

Eligibility criteria

We included experimental (i.e., controlled trials [randomized or not], uncontrolled studies [i.e., same population before and after], and implementation studies [i.e., different population before and after]) that reported the effects of smoking cessation interventions in adult patients with RA in any setting and were published in abstract or full-text format. We included any smoking cessation strategy reported by the authors. We excluded basic science studies (i.e., in vivo, in vitro, or animal studies), studies with different population (i.e., juvenile idiopathic arthritis or not RA), reporting development of methods, opinion pieces (i.e., not original research), or reviews. We also excluded studies not reporting data on the effects of the smoking cessation strategy being evaluated (i.e., studies not directly reporting quantitative data on the intervention). Therefore, qualitative studies, articles reporting tool development without evaluation, case reports, guidelines, protocols, and surveys reporting the prevalence of tobacco use in RA were excluded.

Information sources

We searched the literature in 5 electronic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane, CINAHL, and Web of Science) for articles published from inception until March 2022. Sources of gray literature (unpublished records) were searched through ClinicalTrials.gov. In addition, the reference lists of included articles were hand-searched to identify other potentially relevant studies.

Search

We used a broad search strategy to capture all available studies, including terms related to smoking cessation and RA. An expert librarian (KJK) built the search strategy with input from the study team. Our search was limited to humans, but no other restrictions were imposed. S1 Table shows our search strategy for MEDLINE.

Study selection

For study selection, we followed a 2-step process using DistillerSR (Evidence Partners, Ottawa, Canada; https://www.evidencepartners.com). During the first step, two authors (GS and GS) independently screened titles and abstracts for possible inclusion. For the second step, relevant citations were retrieved in full text to determine the final eligibility for inclusion. Reasons for exclusion were independently recorded, and disagreements were resolved through discussion or, when needed, by a third author (MLO).

Data collection process

Two authors independently collected the data (GS, GS). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when needed, consultation of a third author (MLO). If more than 1 publication reported on the same study, the most recently published results were used. We contacted study authors when clarification was needed regarding any missing outcome data or inconsistencies. Data collected for analyses has been shared in the Open Science Framework repository (https://osf.io/hruyz/?view_only=887674593c43432aac52ddd74b93440b).

Data items

Data collected included: (i) study characteristics (author, year of publication, country, number of centers, funding, methods to assess risk of bias, design), (ii) participants’ characteristics (age, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, pack-years, eligibility criteria), (iii) intervention characteristics (description, provider, timing, duration, etc.), and (iv) outcome data (number of events and number of participants per treatment group for dichotomous outcomes; mean and standard deviation and number of participants per treatment group for continuous outcomes). Our primary outcome was the smoking cessation rates as reported by the authors. Other outcomes included smoking cessation-relate outcomes (i.e., percent abstinent, reduction in the number of cigarettes, referrals to cessation services, assessment of smoking status by providers, number of cigarettes smoked), knowledge about cessation benefits, and RA-related outcomes (i.e., disease activity measured by the Disease Activity Score [27], pain [28], global health assessment [29,30], and function measured by the Health Assessment Questionnaire [31]).

Risk of bias in individual studies

Two authors independently appraised the quality of the studies (GS, GS). Disagreements were resolved by consensus or, when needed, consultation of a third author (MLO). The risk of bias tool (RoB 2.0) for randomized controlled trials and the risk of bias in nonrandomized studies (ROBINS-I) were used to appraise study quality, and the RoBvis tool was used to generate traffic-light plots [32]. The RoB 2.0 questions evaluate the randomization process, the effect of assignment and adherence to the intervention, missing outcome data, measurement of outcomes, and selection of the reported result. Each item was judged as having a high or low risk of bias, some concerns, or no information. ROBINS-I was used to assess bias caused by confounding, selection of participants, classification of the interventions, deviations from intended interventions, missing data, measurements of outcomes, and selection of reported results. These domains were judged as having a low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias, or no information. An overall judgment of the risk of bias was obtained using domain-level judgments. A study with a critical risk of bias in any single domain or a serious risk of bias in 2 or more domains was judged to have an overall critical risk of bias.

Summary measures

Dichotomous data were analyzed as risk ratios with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Continuous data were analyzed as mean differences (MD) with their corresponding 95% CI. For studies without a comparison group, rates were pooled and their 95% CI was calculated. Similarly, for implementation studies with different participants assessed before and after intervention, we pooled the rates (before and after the implementation) separately without a test of difference and calculated their 95% CI.

Synthesis of results

Eligibility for synthesis

Data were pooled if at least 2 studies reported on the same outcome regardless of when was the follow-up assessed. Combining different follow-up times allowed us to determine an estimate independent of time. However, we also evaluated differences between short and long-term studies (≤6 vs > 6 months).

Preparing for synthesis

A random-effects model was used to pool studies. To pool rates of uncontrolled studies, we used the Freeman-Tukey arcsine transformation to stabilize variances and conduct a meta-analysis using inverse variance weights. The resulting estimates and CI boundaries were back-transformed into proportions. Separate analyses were performed for before-and-after studies using the Cochrane methodology to pool paired MDs. An imputed conservative correlation coefficient of 0.8 was used when the within-groups correlation coefficient was not reported [33]. When studies did not report means, we used the median values [34]. Ranges were transformed into standard deviations (SDs) using previously validated methods [35]. Mean and SD were calculated from a frequency distribution with intervals using the formulas: mean = SUM(FREQ*interval midpoint)/SUM(FREQ) and SD = SQRT((n*SUM(FREQ*mean2)—SUM(FREQ*mean)2)/n(n-1).

Statistical and synthesis methods

All statistical tests performed were 2-sided, and we considered a P value of less than 0.05 statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using STATA version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Methods to explore heterogeneity

Study heterogeneity was assessed by using the I2 statistic. An I2 value greater than 50% was considered to indicate substantial inconsistency. Subgroup analyses were performed to investigate whether study characteristics (design, follow-up, and type of intervention and control used) could explain the inconsistency observed.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the robustness of the methods used to impute measures of dispersion (i.e., SD or 95% CI) and the impact of excluding studies with a high risk of bias.

Risk of bias across studies

The risk of publication bias was assessed through funnel plots and an Egger regression test when 10 or more studies reporting on the same outcome were available.

Certainty assessment

A summary-of-findings table was created following the GRADE approach to rate the quality of the evidence for each outcome [36]. We expressed certainty using 4 categories: (i) high quality of evidence, that is, further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the effect estimate; (ii) moderate quality, that is, further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the effect estimate and may change the estimate; (iii) low quality, that is, further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the effect estimate and is likely to change the estimate; and (iv) very low quality, that is, we are uncertain about the estimate.

Results

Study selection

Flow of studies

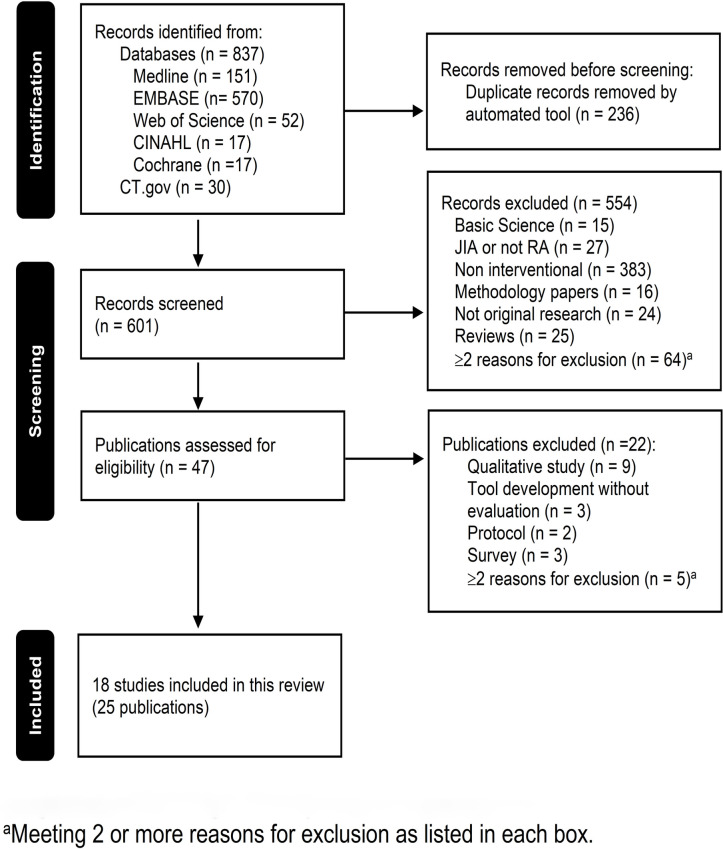

We retrieved 837 citations. After removal of duplicates, 601 abstracts were screened. Of these, only 47 moved to the full-text screening. Fig 1 shows the diagram of study selection with the reasons for exclusion in each phase. Twenty-five publications (18 studies) met our study eligibility criteria [37–61].

Fig 1. Diagram of study selection.

CT.gov, ClinicalTrials.gov; JIA, juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

Excluded studies

The list of excluded studies is shown in S2 Table.

Study characteristics

Among the 18 studies included in the review, 10 studies were reported in abstract format (Table 1). Three studies were randomized controlled trials [37,46,58], and the rest were nonrandomized studies: 10 were uncontrolled trials (same participants evaluated at baseline and follow-ups) [42,44,47,48,50–54,59], and 5 were implementation studies (different participants evaluated before and after implementation of the intervention) [38–41,45]. Sample sizes ranged from 20 to 970. Seven studies included patients with RA and other conditions [38–40,50,51,54,59].

Table 1. Study characteristics.

| Study | Country | No. of centers | Sample size, No.a | Population | Follow-up | Recruitment Period | Outcome(s) reportede | Funding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Randomized controlled trials | ||||||||

| Aimer 2017 [37,57] | New Zealand | 1 | 38 (I = 19, C = 19) |

All RA | 6 months | 2012–2014 | Smoking cessation Reduction in cigarette consumption |

New Zealand Health Research Council and Arthritis New Zealand. University of Otago Research Fund |

| John 2013 [46] | UK | 1 | 110 (I = 52, C = 58) |

All RA | 6 months | 2010 | Current smoking Knowledge |

Arthritis Research UK |

| Soubrier 2013 [56,58] b | France | 20 | 970 (I = 488, C = 482) |

All RA (ACR 1987 criteria) | 6 months | 2011 | Smoking cessation | French National Research Program. Roche Ltd France |

| Uncontrolled trials (same participants assessed at baseline and follow-up) | ||||||||

| Al Hamarneh 2021 [59] | Canada | 17 | 99 | Rheumatic diseases (55 with RA) | 6 months | 2017–2019 | Smoking status | Canadian Initiative for Outcomes in Rheumatology |

| Gordon 2001, 2002 [42,43] | UK | 1 | 22 | RA, starting treatment with sulfasalazine | 48 weeks | NR | Smoking cessation Reduction in cigarette consumption |

NR |

| Gudelj Gracanin 2014 [44] b | Croatia | 2 | 96 | RA (1987 criteria) | 1 month | NR | Smoking cessation Pain, DAS28-CRP |

None |

| Karlsson 2014 [47] b | Sweden | 1 | 40 | Early RA or starting a first biological treatment | 2 years | 2011–2013 | Smoking cessation Reduction in cigarette consumption Smoking status Pain, global health, HAQ |

NR |

| Khan 2017 [48] b | Ireland | 1 | 180 | RA (1987 criteria) | 6 months | 2016–2017 | Smoking cessation DAS28-CRP |

NR |

| Naranjo 2013, 2014 [49,50] | Spain | 1 | 152 | Inflammatory rheumatic diseases (55 with RA) | 12 months | 2011 | Smoking cessationc Reduction in cigarette consumptionc Smoking status |

None |

| Sadhana Singh Baghel 2016, 2017 [51,55] b | India | 1 | 211 | Rheumatology patients seen in outpatient department (162 with RA) | NR | NR | Smoking cessation | None |

| Tekkatte 2016 [52] b | UK | 1 | 20 | Established RA | NR | NR | Knowledge | None |

| Thomas 2015 [53] b | UK | 1 | 100 | NR | 1 year | 2011–2012 | Smoking status | None |

| Zeun 2015 [54] b | UK | 1 | 202 | Rheumatology patients (62 with RA) | 1 year | NR | Smoking cessationd | None |

| Implementation studies (different participants assessed before and after intervention) | ||||||||

| Bartels 2017 [38,60] | USA, Wisconsin | 3 | B = 135, A = 421 | Rheumatology patients seen in 3 clinics (unspecified # for RA) | 6 months | 2012–2016 | Referral to the Quit line | None |

| Brandt 2020 [39,61] b | USA, Atlanta | 1 | B = 535, A = 123 | Rheumatology patients with tobacco use (unspecified # for RA) | 3 months | NR | Referral to the Quit line Smoking status |

NR |

| Chodara 2018 [40] b | USA, Wisconsin | 1 | B = 100, A = 129 | Rheumatology patients seen in 1 clinic (unspecified # for RA) | NR | 2015–2018 | Referral to the Quit line | NR |

| Chow 2019 [41] | New Zealand | 1 | B = 53, A = 100 | All RA | NR | 2004–2016 | Referral for smoking cessation Reduction in cigarette consumption Smoking status |

NR |

| Harris 2016 [45] | UK, Scotland | 1 | B = 306, A = 340 | Seropositive RA attending UK National Health Service | NR | NR | Reduction in cigarette consumption Smoking status Knowledge |

Pfizer |

DAS28-CRP, Disease Activity Scale 28 Joints–C Reactive Protein; HAQ, Health Assessment Questionnaire–Disability Index; NR, not reported; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

aNumbers reflect the total number of patients included in the study (i.e., people who smoke [active, passive, current, past] or people who do NOT smoke), independently if they received the intervention or not.

bPublication was a conference abstract.

cTotal abstinence in the last 7 days; Reduction in cigarette consumption by ≥30% or at least 50%.

dTotal abstinence for at least 2 weeks, verified by a carbon monoxide reading of 0–6 parts per million.

eOutcomes reported relevant to this review.

Participants’ characteristics

Mean age ranged from 50 to 65 years (S3 Table). The percentage of female participants ranged from 51% to 91%. In 7 studies, all participants were current tobacco users [37–40,47,48,50]. The remaining studies included a mixture of former and current tobacco users, with rates of current tobacco users ranging from 11% to 36%.

Intervention characteristics

The studies were divided by type of intervention (Table 2). There were 6 types of interventions targeting patients: 1 study reporting on a social marketing campaign [45]; 3 reporting on a health education intervention alone [44,51,52], 1 reporting on health education combined with nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) [48], 3 reporting on health education combined with NRT plus counseling sessions [37,50,54], 1 reporting on counseling sessions alone [47], and 4 reporting on lifestyle education focused on cardiovascular risk with goal setting [43,46,53,56,59]. There were 2 types of interventions targeting providers: 3 studies (18%) reported using electronic health record prompts to assess smoking status and offer training on how to refer to Quit line support services [38–40], and 1 study reported using a screening questionnaire to assess smoking status to offer referrals [41].

Table 2. Intervention characteristics.

| Study | Description of intervention | Provided by | Duration | Follow-up assessment | Comparison groups or subgroup analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social marketing campaign | |||||

| Harris 2016 [45] | Postcards mailed, poster in outpatient departments, press statement, website, newspaper and radio | Not applicable | Not specified | 3–12 months following the campaign |

- |

| Health Education | |||||

| Gudelj Gracanin 2014 [44] | Short, spoken advice about the harms of smoking and advice to quit smoking | Not specified | Once | 1 month | - |

| Sadhana Singh Baghel 2014, 2016 [51,55] | Information about methods of quitting tobacco and its importance | Not specified | Once | Not specified | Passive vs active tobacco users |

| Tekkatte 2016 [52] | Information provided about the increased risk of RA, severe disease, and poor response with smoking | Not specified | Once | Immediately after | - |

| Health education + NRT | |||||

| Khan 2017 [48] | Face-to-face advice, handout, and NRT | Not specified | Once | 6 months | Gender, age, BMI, disease activity |

| Health education + NRT + Counseling sessions | |||||

| Aimer 2017 [37] | Face-to-face educational session, educational handout explaining the effect of smoking on RA | ABCa by the rheumatology clinical nurse specialist. Additional education by community-based arthritis educators trained in smoking cessation | 3 follow-up telephone calls, a support website, and 12 weekly smoking cessation advice e-mails with educationb | 6 months | Health education + NRT + Counseling sessions vs Health education + NRT |

| Naranjo 2013, 2014 [49,50] | Verbal or written advice on the benefits of quitting smoking + written documentation with helpful tips on how to quit smoking + NRT if needed | Rheumatologist | Telephone follow-up visit in the 3rd month by the rheumatology nurse | 12 months | Active vs former tobacco users |

| Zeun 2015 [54] | An information booklet in waiting areac + behavioral support sessions | Smoking advisor at the point of rheumatology contact | Patients attended counseling for 6 weeksd | 12 months | Patients attending the rheumatology service versus those attending the service of their preference |

| Counseling sessions | |||||

| Karlsson 2014 [47] | Individualized smoking cessation support | Rheumatology nurse with special training in motivational interviewing and smoking cessation | Contact every 4 weeks | 2 years | Patients who continue to tobacco users vs those quitting |

| Lifestyle education (in the context of CVD risk) + goal setting | |||||

| Al Hamarneh 2021 [59] | Individualized CVD risk assessment and education | Pharmacist | Monthly follow-up to check on progress and provide ongoing care and motivation | 6 months | - |

| Gordon 2001, 2002 [42,43] | Advised on CVD risk including generic quitter’s pack (further advice and telephone numbers) | General practitioner | Clinic appointments dealing with lifestyle factors every 12 weeks | 48 weeks | - |

| John 2013 [46] | Small-group education on CVD risk | Rheumatology research registrar with interest in patient education | 8-week coursee | 6 months | Participants vs waiting list candidatesf |

| Soubrier 2013 [56] | Advised on CVD risk management + reportg sent to physician and rheumatologist | Nurseh | Not specified | 6 months | Nurse-led program vs patients receiving a video on joint self-assessment |

| Thomas 2015 [53] | Lifestyle assessment + CVD risk + health promotion advice and literature | Not specified | Patients with high risk of CVD were offered 6 sessions to support goals (including smoking cessation) | 12 months | - |

| Interventions targeting providers | |||||

| Study | Intervention | Target population | Description | Implementation period | Objective |

| Bartels 2017 [38] | Quit Connect protocol training | Nurses and medical assistants | See footnotei | 6 months | To measure process steps |

| Brandt 2020 [39] | Quit Connect protocol training | Staff | See footnotei | 3 months | To determine performance and rates of triage |

| Chodara 2018 [40] | Quit Connect protocol training (1-h session + monthly feedback on fidelity) | Medical assistants | See footnotei | 3 years | To determine delivery of protocol components per patient visit |

| Chow 2019 [41] | Brief screening questionnaire completed in the waiting room prior to the clinic appointment | Reception staff | People who smoke were offered referral for smoking cessation support available free of charge | 6 years | To assess smoking status and offer referrals |

BMI, body mass index; CVD, cardiovascular disease; EHR,electronic health record system; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

aABC (Ask, Brief advice, Cessation support) = brief advice and subsidized NRT for 8 weeks.

bEducation about smoking and RA, pain control, exercise, coping, and support.

cAbout the impact of smoking in various rheumatological conditions.

dDuring the first session the counselor asked about smoking behavior and previous attempts to quit, assessed nicotine dependence and discussed stop-smoking medications with the patient. Behavioral support was provided to help manage cravings, withdrawal symptoms, and change routines.

eExplored current beliefs about CVD and participants’ responses to learning about the increased CVD risk associated with RA. The important role of lifestyle modifications was discussed, and participants were challenged to determine (using various probing behavioral techniques) and commit to a specific behavior change. Graded goal setting was used as a technique to help them achieve the goal.

fThe waiting-list participants received an information booklet about the study.

gSummary report of non-agreement with the recommendations of the French Society of Rheumatology in 4 RA comorbidities.

hNurses were trained and given a booklet to be used for the systematic identification and assessment of comorbidities (including CVD). Actions taken into account for CVD included smoking cessation (identification of smoking status and calculation of pack-years).

iEHR prompts to assess smoking status and 30-day readiness to quit or cut back + advise to quit + electronically connect those willing to receive Quitline support.

Risk of bias within studies

S1 Fig shows the traffic-light plot of the risks of bias in the included studies. The randomized controlled trials were rated as having an overall low risk of bias, although concerns about randomization were raised for 2 studies. However, for the nonrandomized trials, all studies were judged to have methodological concerns and 9 were considered to have an overall serious risk of bias.

Outcomes of interventions targeting patients

Smoking cessation

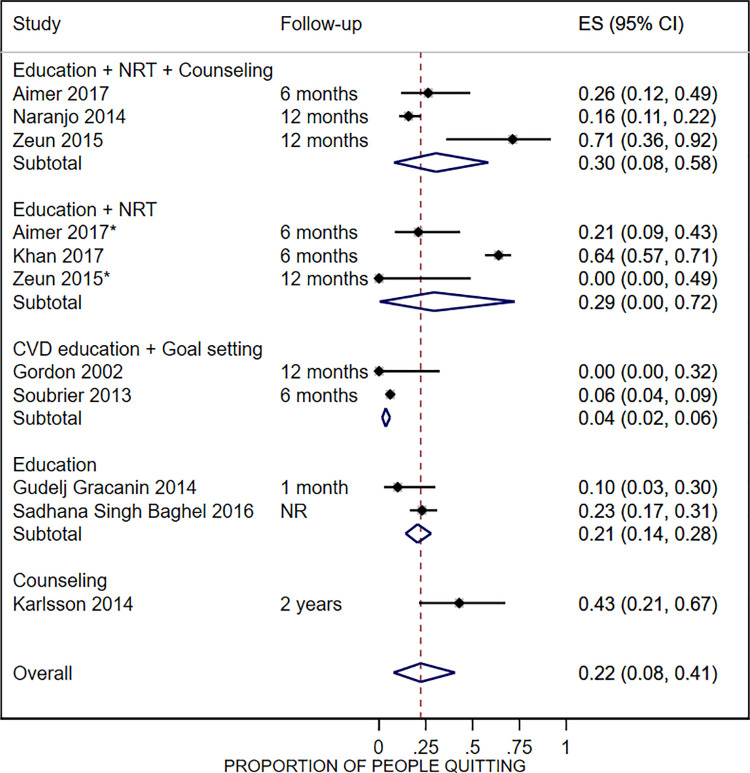

Nine studies reported on this outcome [37,42,44,47,48,50,51,54,56], but only 2 studies defined cessation: 1 as total abstinence in the last 7 days [50] and the other as total abstinence for at least 2 weeks, as verified by a carbon monoxide reading of 0 to 6 parts per million [54]. The remaining studies reported the rates at which participants self-reported quitting smoking without additional details regarding time frame. Rates of smoking cessation varied according to the type of intervention evaluated (Fig 2). The lowest pooled rate was observed in studies evaluating lifestyle education in the context of cardiovascular risk combined with goal setting sessions (4%, 95% CI: 2% to 6%), and the highest rate was reported by a study evaluating counseling sessions for 2 years (43%, 95% CI: 21% to 67%). The pooled rate of smoking cessation from all studies after any intervention (follow-up ranged from 4 weeks to 2 years) was 22% (95% CI: 8% to 41%; I2 = 96%; n = 9 studies). Table 3 shows the results of comparative studies evaluating this outcome [37,54,58]. No differences were observed in any of the 3 controlled trials comparing the intervention to a control group.

Fig 2. Self-reported smoking cessation rates.

*Smoking cessation rates for Aimer 2017 and Zeun 2015 are reported for the intervention and control group in separate rows because both strategies provided smoking cessation services. In the control group in Zeun 2015, patients were referred to their general practitioner for smoking cessation services. ES, effect estimate (proportion of people quitting); CI, confidence interval; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy; CVD, cardiovascular disease. Inconsistency scores for the subgroups (I2): Education+NRT+Counseling = 80.2%; Education+NRT = 90.3%; CVD education+Goal setting = 0%; Education = 0%; Counseling = not applicable.

Table 3. Synthesis of results from controlled studies evaluating interventions targeting patients.

| Study | Intervention | Control | Outcome | Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aimer 2017 [37] | ABC + brief advice and subsidized NRT + additional smoking cessation advice for 3 months | ABC + brief advice + subsidized NRT without the 3 months of sessions | Self-reported smoking cessation rates | RR 1.3 95% CI 0.40 to 4.0 |

| Reduction in the number of cigarettes | MD 1.3 95% CI −4.4 to 7.0 |

|||

| Sustained reduction in smoking at 6 months | RR 0.89 95% CI 0.44 to 1.8 |

|||

| Soubrier 2013 [58] | Nurse assessed comorbidities (including smoking) + with reports sent to the participant’s physicians | Sham program (video on joint self-assessment plus nurse training on joint self-assessment combined) | Self-reported smoking cessation rates | RR 1.3 95% CI 0.75 to 2.2 |

| Zeun 2015 [54] | Patients referred to a general practitioner for smoking cessation services | Patients received 1-year education program with access to the rheumatology clinic stop-smoking services | Self-reported smoking cessation rates | RR 0.76 95% CI 0.44 to 1.3 |

ABC, ask–brief advice–cessation support; RR, relative risk; CI, confidence interval; MD, mean difference; NRT, nicotine replacement therapy.

Percent abstinent

Two studies [47,50] provided the percentage of participants who continued to smoke after the intervention. The pooled rate of abstinent people after the intervention was 21% (95% CI: 11% to 31%). Two studies [53,59] evaluated a cardiovascular risk factors education and found no difference in the number of participants who continued smoking 6–12 months after the intervention (p>0.3). One implementation study with different participants assessed before and after implementation [45] reported similar rates of abstinence in both populations (80%; 95% CI: 75% to 84% vs 78%; 95% CI: 73% to 82%).

Reduction in the number of cigarettes

Five studies reported on this outcome. In 1 comparative study, there was no statistically significant difference between groups (Table 3) [37]. Among 3 uncontrolled trials, 1 study reported that only 2 of the 8 participants who were current tobacco users reduced the number of cigarettes smoked a day, but the mean number of cigarettes smoked was not provided [42,43]. At 12 months, Naranjo and colleagues reported a reduction in smoking cigarettes of 30% or greater in 55 of 152 participants and a reduction of 50% in cigarette consumption in 29 of 152 participants [49,50]. Karlson et al. reported a significant reduction in the number of cigarettes smoked before and after the intervention for those participants who continued smoking (MD −9.0, 95% CI: −13.8 to −4.1) [47]. For 1 implementation study with different participants assessed before and after the intervention, the mean (± SD) number of cigarettes smoked per day was similar in the post-implementation and pre-implementation periods (12 ± 7 vs. 14 ± 8, respectively) [45].

Knowledge about benefits of smoking cessation

Three studies reported on this outcome. John and colleagues reported mean scores at 6 months on the Heart Disease Fact Questionnaire-Rheumatoid Arthritis (HDFQ-RA), a 13-item questionnaire [46]. The mean (± SD) score in the intervention group, which participated in 2.5-hour education meetings weekly for 8 weeks, was 10.2 ± 2.4, while that of the control group, which was a waiting-list delayed-intervention arm, was 9.1 ± 2.75 (MD: 1.1; 95% CI: 0.13 to 2.1). Tekkatte et al. reported similar scores for participants’ knowledge regarding the importance of smoking on arthritis across 3 groups: current, past, and never-tobacco users (visual analog scale [VAS] mean ± SD: 7.1 ± 2.4, 7.7 ± 1.9, and 7.4 ± 2.2, respectively) [52]. In an implementation study (i.e., one with different participants before and after the intervention) asking participants whether there is a link between RA and smoking, the percentage of adequate responses increased from 5.2% to 25.9%. When participants in this study were asked whether smoking can lessen the effectiveness of RA treatment, the percentage of adequate responses rose from 4.2% to 48.5% [45].

Disease measures

Two studies reported data on disease measures. Karlsson et al. compared patients who quit smoking with the intervention versus those who continued smoking at 2 years [47]. The mean pain score of patients who quit smoking improved from 37.5 to 3.0; whereas the mean pain score of patients who continued smoking improved by much less (from 60 to 40; MD: −37.0; 95% CI: −64.7 to −9.3). The global health assessment score decreased from 37.5 to 3.5 in patients who quit smoking, compared to 56.5 to 29.0 in patients who continued smoking (MD: −25.5; 95% CI: −51.9 to 0.91). The mean Health Assessment Questionnaire score improved from 0.57 to 0.0 in patients who quit versus 0.75 to 0.26 in patients who continued smoking (MD: −0.26; 95% CI: −0.84 to 0.32). Similarly, Khan et al. compared participants who quit smoking with participants who continued to smoke. The mean Disease Activity Score-28 for Rheumatoid Arthritis with C-Reactive Protein (DAS28-CRP) was higher in patients who continued smoking than in patients who quit smoking (4.9 vs 2.9, respectively; MD: −2.0; 95% CI: −2.3 to −1.7).

Outcomes of interventions targeting providers

Referrals to smoking cessation services

Four studies provided rates of referral to smoking cessation services before and after implementation in different populations for each period evaluated (S4 Table). In all studies, the pooled rate of referrals increased from pre- to post-implementation (5% to 70% at 3–6 months).

Smoking status

Two implementation studies with different participants assessed an intervention for providers before and after implementation [39,41]. The pooled rate of current tobacco users was lower in the post-implementation population at 6 months (15%; 95% CI: 13% to 18%) than in the pre-implementation population (20%; 95% CI: 18% to 21%) (S4 Table).

Number of cigarettes smoked

For one implementation study with different participants assessed before and after intervention and unspecified follow-up, the mean (± SD) number of cigarettes smoked per day was similar in the post-implementation period and the pre-implementation period (7 ± 4 vs. 8 ± 5, respectively) [41].

Heterogeneity

No statistically significant differences were observed in the pooled smoking cessation rates when studies were grouped by design (controlled trials: 11%; 95% CI: 1% to 26%; I2 = 76% vs uncontrolled studies: 30%; 95% CI: 11% to 53%; I2 = 94%; p = 0.12). In addition, no differences in cessation rates were observed between studies with different follow-up periods (≤ 6 months: 23%; 95% CI: 4% to 51%; I2 = 98% vs > 6 months: 21%; 95% CI: 3% to 46%; I2 = 76%; p = 0.98). Finally, the type of intervention used also did not significantly affect smoking cessation rates (with follow-up sessions/contact: 22%; 95% CI: 7% to 41%; I2 = 72% vs without follow-up sessions/contact: 23%; 95% CI: 3% to 54%; I2 = 98%; p = 0.96).

Removing studies that included patients with other rheumatic diseases did not influence the direction or the magnitude of the smoking cessation rate (22%; 95% CI: 2% to 52%; I2 = 97.6%). However, removing studies with a high risk of confounding bias resulted in a lower proportion of patients quitting smoking (17%; 95% CI: 6% to 31%; I2 = 85%).

Reporting biases

There was no evidence of small-study effects (Egger test p = 0.69) in the funnel plot for the primary outcome assessed (S2 Fig).

Certainty of evidence

The summary of findings table is shown as S5 Table. The evidence for the main outcome, self-reported cessation rates, was of moderate quality due to limitations in study design and inconsistency of results. Similarly, the evidence for the effects of smoking cessation strategies versus control was of moderate quality due to imprecision and the estimate derived from one small study.

Discussion

We identified published reports of smoking cessation strategies for patients with RA and synthesized their data on smoking cessation outcomes, referrals to quit services, knowledge about the benefits of cessation, and the benefits of smoking cessation on health outcomes. We found that the success rates of people with RA quitting smoking varied according to strategy used, follow-up duration, and quality of the studies with a pooled cessation rate of 22%. Furthermore, the majority of studies were not randomized trials and several lacked adequate comparator groups, therefore being subject to bias. When high-risk of bias studies were removed, the cessation rates were even lower (17%). This indicates that an optimal and more active strategy for this specific population is yet to be established and tested with a more rigorous methodology.

The most frequent strategy used in the studies included in this review was education with advice to quit smoking delivered in the context of cardiovascular risk. This type of interventions do not conform to current smoking cessation guidelines, in which counseling treatments and medications are recommended [62]. In our review, fewer than half of the studies (41%) reported use of telephone calls, emails, and counseling sessions to provide follow-up support. Included studies reporting on interventions that included counselling and/or NRT achieved greater cessation rates. This is similar to the evidence observed from the general population showing that extended counseling with pharmacotherapy enhances sustained abstinence relative to brief, time-limited approaches. Although for patients with RA, there may need to be some tailoring to cover the specific needs of these patients. Prior studies have explored the specific problems that tobacco interventions need to address in patients with RA [63–66]. Patients have expressed the need for counseling that highlights the relationship between smoking and RA to understand better the short- and long-term complications. They also wanted to learn how to replace smoking for alternatives when smoking was used as a coping mechanism for the frustrations of living with the disease or as a distraction from pain, in particular when most patients with active or severe disease find it difficult to exercise and use it as an alternative distraction. Finally, they prefer alternatives that help them overcome feeling unsupported and isolated from other patients with RA.

One noteworthy finding is that the included controlled trials reported similar cessation rates between groups in 3 different clinical scenarios: (1) comparing education and advice combined with NRT plus counseling versus the same elements without the counseling sessions; (2) comparing a nurse-administered program to evaluate cardiovascular risk factors and other comorbidities combined with sending a report to providers versus a sham program; and (3) education and advice given in the rheumatology clinic versus a general practice of the patient’s choice. The study with the first scenario explored the specific problems that tobacco interventions need to address in patients with RA [37,57]. All participants (intervention and control group) were offered cessation support if they wanted to quit and NRT. They also were counseled to highlight the relationship between smoking and RA to understand better the short- and long-term complications. However, participants in the intervention group were instructed on how to replace smoking for alternatives when smoking was used as a coping mechanism for the frustrations of living with the disease or as a distraction from pain, in particular when most patients with active or severe disease find it difficult to exercise and use it as an alternative distraction. They also received access to a support website to help them overcome feeling unsupported and isolated from other patients with RA. Although the smoking cessation rates in the intervention group were higher compared to the control group, the difference did not reach statistical significance. Both groups achieved smoking cessation rates higher than those rates reported for the general population when no intervention is received [67]. This finding supports previous expert opinion that even a brief general advice intervention not necessarily tailored to specific barriers can increase smoking cessation rates and that more complex or intensive interventions add only small benefits compared to standard care of care. This hypothesis will need to be further tested given that the pooled rate of smoking cessation from all the included studies was lower than the published average cessation rates for minimal interventions in the general population (22% vs 50–60% [68]). Some qualitative studies have explored barriers to and facilitators of smoking cessation in rheumatology clinics. This evidence suggests that psychosocial factors (e.g., patients’ feeling that smoking is ‘the one thing they still have control over’ while dealing with the burden of rheumatic disease), judgmental cessation support from rheumatology staff, lack of investment from providers (e.g., every provider recommending quitting without providing a solution), and lack of cessation education resources are the main barriers to quitting for patients with RA [69]. Patients’ readiness to quit and use of NRT were the most common facilitators of smoking cessation, and visible health effects and the cost of cigarettes were found to be the factors with the most influence on the desire to quit [63,69].

Another important agenda for future research is to find the best choice of outcome measures in this population. Apart from smoking abstinence, the number of cigarettes consumed per day for participants who continued smoking after receiving the intervention and improvement in knowledge about the benefits of smoking cessation after participants received the intervention have also been reported. It is unknown if these outcomes would translate in benefits in disease outcomes. To date only one study has showed improvement in pain, disability, and disease activity scores for patients who quit smoking using structured counseling every 4 weeks over 2 years compared to those who continued to smoke [47]. Future studies focusing on smoking cessation interventions in patients with RA should ensure that disease outcomes are measured given the highly clinical relevance of the measures and considering that many tobacco users with RA report smoking to cope with disease symptoms. To our knowledge, no other reviews have attempted to synthesize the effects of smoking cessation interventions specifically for patients with RA. One Cochrane review considered studies in patients with chronic autoimmune inflammatory joint diseases, but only 2 studies (also included in this review) could be synthesized narratively with no attempt to combine results of the individual studies [70].

Our study has limitations, including a lack of comparative evidence for most strategies reported and large heterogeneity in the populations, definitions of cessation, settings, methodologies used, and points of assessment, which restricted our ability to synthesize the effects. Moreover, most of the meta-analyses performed showed substantial inconsistency scores reflecting substantial clinical, methodological, and statistical heterogeneity. Nonetheless, the trends observed in our results seem to indicate that interventions that include counseling or another type of follow-up method (rather than a 1-time interaction) achieve greater cessation rates. In addition, only limited evidence was reported regarding the effects of smoking cessation on disease-related outcomes, which as evidence by prior qualitative data, RA symptoms are one of the listed reasons for continuing smoking. Furthermore, none of the studies compared cessation rates according to RA treatment received, functional ability, or other medical characteristics that could be helpful to determine the subpopulations that could most benefit from cessation strategies. Another concern was the serious risk of bias observed in the majority of the nonrandomized studies (i.e., 10 out of 18 studies were uncontrolled trials assessing the same participants before and after the intervention and 5 were implementation studies with different participants assessed before and after the intervention). Most such studies did not account for confounding factors (e.g., socioeconomic status, previous smoking cessation attempts, mental health). Moreover, the cessation outcomes were biased given that all studies but one used participant self-reports, rather than biochemical methods, to verify smoking status. Although self-reported smoking cessation is a simple and convenient method, prior studies have shown that participants do not always accurately report their smoking status [71], which can yield inaccurate estimates of the proportion of people quitting. Therefore, the level of certainty of the evidence was considered moderate to very low. This was further exacerbated by the limited information reported in studies published as conference abstracts (10 out of 18). Finally, our results should be carefully interpreted. The cessation rates reported in the studies were substantially heterogeneous which may not only reflect the different population characteristics and cessation strategies used but could also be attributed to different implementation intensities of the interventions evaluated. Adequate research studies with more robust methodology still need to be conducted to identify the effectiveness of smoking cessation programs targeting patients with RA. One promising randomized controlled trial comparing the effect on disease activity of an intensive smoking cessation intervention versus standard of care is still in progress, and its results have not yet been reported [72]. Thus, it is imperative that further well-designed studies be conducted to confirm the results observed in this review.

In conclusion, there was substantial heterogeneity due to differences in patient characteristics, the interventions used, and their implementation structure. Only 3 studies were controlled clinical trials and smoking cessation rates were similar across controlled and uncontrolled trials. However, the rates observed were even lower when removing studies with high risk of bias and considering the likelihood of overestimation due to the self-reported nature of the primary outcome measure, our findings suggest that additional studies evaluating stronger interventions based on current smoking cessation guidelines are needed to facilitate smoking cessation in patients with RA.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

Preliminary results of this study were presented to the European League Against Rheumatism. Citation: Lopez-Olivo MA, Volk RJ, Krause KJ, Suarez-Almazor ME.

A review of smoking cessation strategies and lung cancer screening practices in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79 (supplement 1): 1422.

We acknowledge the literature searching and editorial support of the Research Medical Library at MD Anderson.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the Tobacco Settlement Funds Research Resource Program (Maria E. Suarez-Almazor, PhD, Principal Investigator), in part by a Cancer Prevention Fellowship for Justin James (National Cancer Institute R25 grant CA056452, Shine Chang, PhD, Principal Investigator), and in part by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center’s Cancer Center Support Grant from the National Cancer Institute (CA016672, Peter WT Pisters, MD, Principal Investigator).

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Tobacco. Key facts. Available at: https://wwwwhoint/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/tobacco; accessed on: 08/26/2022. 2021.

- 2.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The Health Consequences of Smoking—50 Years of Progress: A Report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health. 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goodchild M, Nargis N, Tursan d’Espaignet E. Global economic cost of smoking-attributable diseases. Tob Control. 2018;27(1):58–64. Epub 2017/02/01. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2016-053305 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5801657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Myasoedova E, Crowson CS, Kremers HM, Therneau TM, Gabriel SE. Is the Incidence of Rheumatoid Arthritis Rising? Results From Olmsted County, Minnesota, 1955–2007. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2010;62(6):1576–82. doi: 10.1002/art.27425 WOS:000279432500005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eriksson JK, Neovius M, Ernestam S, Lindblad S, Simard JF, Askling J. Incidence of Rheumatoid Arthritis in Sweden: A Nationwide Population-Based Assessment of Incidence, Its Determinants, and Treatment Penetration. Arthrit Care Res. 2013;65(6):870–8. doi: 10.1002/acr.21900 WOS:000319758900006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jamal A, King BA, Neff LJ, Whitmill J, Babb SD, Graffunder CM. Current Cigarette Smoking Among Adults—United States, 2005–2015. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2016;Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention:1205–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adult Tobacco Survey—19 States 2003–2007, Surveillance Summaries. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugiyama D, Nishimura K, Tamaki K, Tsuji G, Nakazawa T, Morinobu A, et al. Impact of smoking as a risk factor for developing rheumatoid arthritis: a meta-analysis of observational studies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(1):70–81. Epub 2009/01/29. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096487 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Di Giuseppe D, Discacciati A, Orsini N, Wolk A. Cigarette smoking and risk of rheumatoid arthritis: a dose-response meta-analysis. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(2):R61. Epub 2014/03/07. doi: 10.1186/ar4498 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4060378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ye D, Mao Y, Xu Y, Xu X, Xie Z, Wen C. Lifestyle factors associated with incidence of rheumatoid arthritis in US adults: analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey database and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2021;11(1):e038137. Epub 2021/01/28. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038137 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7843328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hutchinson D, Shepstone L, Moots R, Lear JT, Lynch MP. Heavy cigarette smoking is strongly associated with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), particularly in patients without a family history of RA. Ann Rheum Dis. 2001;60(3):223–7. Epub 2001/02/15. doi: 10.1136/ard.60.3.223 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1753588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokolove J, Wagner CA, Lahey LJ, Sayles H, Duryee MJ, Reimold AM, et al. Increased inflammation and disease activity among current cigarette smokers with rheumatoid arthritis: a cross-sectional analysis of US veterans. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2016;55(11):1969–77. Epub 2016/08/02. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kew285 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5088624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Naranjo A, Sokka T, Descalzo MA, Calvo-Alen J, Horslev-Petersen K, Luukkainen RK, et al. Cardiovascular disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from the QUEST-RA study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2008;10(2):R30. Epub 2008/03/08. doi: 10.1186/ar2383 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2453774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joseph RM, Movahedi M, Dixon WG, Symmons DP. Risks of smoking and benefits of smoking cessation on hospitalisations for cardiovascular events and respiratory infection in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective cohort study using the Clinical Practice Research Datalink. RMD Open. 2017;3(2):e000506. Epub 2017/10/12. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2017-000506 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5623338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roh S. Smoking as a Preventable Risk Factor for Rheumatoid Arthritis: Rationale for Smoking Cessation Treatment in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis. J Rheumat Dis. 2019;26(1):12–9. doi: 10.4078/jrd.2019.26.1.12 WOS:000523559600003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Force USPST, Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265–79. Epub 2021/01/20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Andersson ML, Bergman S, Soderlin MK. The Effect of Stopping Smoking on Disease Activity in Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA). Data from BARFOT, a Multicenter Study of Early RA. Open Rheumatol J. 2012;6:303–9. Epub 2012/11/02. doi: 10.2174/1874312901206010303 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3480711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Godtfredsen NS, Lam TH, Hansel TT, Leon ME, Gray N, Dresler C, et al. COPD-related morbidity and mortality after smoking cessation: status of the evidence. Eur Respir J. 2008;32(4):844–53. WOS:000259944500005. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00160007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornuz J, Feskanich D, Willett WC, Colditz GA. Smoking, smoking cessation, and risk of hip fracture in women. Am J Med. 1999;106(3):311–4. WOS:000079310300008. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)00022-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peto R, Darby S, Deo H, Silcocks P, Whitley E, Doll R. Smoking, smoking cessation, and lung cancer in the UK since 1950: combination of national statistics with two case-control studies. Brit Med J. 2000;321(7257):323–9. WOS:000088656300020. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7257.323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sparks JA, Chang SC, Nguyen UDT, Barbhaiya M, Tedeschi SK, Lu B, et al. Smoking Behavior Changes in the Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Period and Risk of Mortality During Thirty-Six Years of Prospective Followup. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2018;70(1):19–29. Epub 2017/05/04. doi: 10.1002/acr.23269 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5668209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.PHS Guideline Update Panel, Liaisons, Staff. Treating tobacco use and dependence: 2008 update U.S. Public Health Service Clinical Practice Guideline executive summary. Respir Care. 2008;53(9):1217–22. Epub 2008/09/24. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.US Preventive Services Task Force, Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, Barry MJ, Cabana M, et al. Interventions for Tobacco Smoking Cessation in Adults, Including Pregnant Persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021;325(3):265–79. Epub 2021/01/20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vreede A, Voelker K, Wong J, Bartels CM. Rheumatologists More Likely to Perform Tobacco Cessation Counselling in Uncontrolled Rheumatoid Arthritis Visits. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67. WOS:000370860204182. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, et al. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0 (updated July 2019). Cochrane, 2019. Available from wwwtrainingcochraneorg/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, et al. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. Epub 2019/10/24. doi: 10.1002/14651858.ED000142 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Prevoo ML, van ’t Hof MA, Kuper HH, van Leeuwen MA, van de Putte LB, van Riel PL. Modified disease activity scores that include twenty-eight-joint counts. Development and validation in a prospective longitudinal study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1995;38(1):44–8. Epub 1995/01/01. doi: 10.1002/art.1780380107 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fries JF, Spitz PW, Young DY. The dimensions of health outcomes: the health assessment questionnaire, disability and pain scales. J Rheumatol. 1982;9(5):789–93. Epub 1982/09/01. . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scott PJ, Huskisson EC. Measurement of functional capacity with visual analogue scales. Rheumatol Rehabil. 1977;16(4):257–9. Epub 1977/11/01. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/16.4.257 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan NA, Spencer HJ, Abda EA, Alten R, Pohl C, Ancuta C, et al. Patient’s global assessment of disease activity and patient’s assessment of general health for rheumatoid arthritis activity assessment: are they equivalent? Ann Rheum Dis. 2012;71(12):1942–9. Epub 2012/04/26. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2011-201142 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3731741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcome in arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 1980;23(2):137–45. Epub 1980/02/01. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGuinness LA, Higgins JPT. Risk-of-bias VISualization (robvis): An R package and Shiny web app for visualizing risk-of-bias assessments. Research Synthesis Methods. 2020;n/a(n/a). doi: 10.1002/jrsm.1411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rosenthal R. Meta-analytic procedures for social research. Newbury Park, CA: SAGE Publications Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Higgins J, Li T, Deeks Je. Chapter 6: Choosing effect measures and computing estimates of effect. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (editors) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 63 (updated February 2022) Cochrane, 2022. Available from wwwtrainingcochraneorg/handbook. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan X, Wang W, Liu J, Tong T. Estimating the sample mean and standard deviation from the sample size, median, range and/or interquartile range. BMC Medical Research Methodology. 2014;14(1):135. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-14-135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schünemann H, Brożek J, Guyatt G, Oxman A, editors. GRADE handbook for grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. The GRADE Working Group, 2013 Available from guidelinedevelopmentorg/handbook. Updated October 2013.

- 37.Aimer P, Treharne GJ, Stebbings S, Frampton C, Cameron V, Kirby S, et al. Efficacy of a Rheumatoid Arthritis-Specific Smoking Cessation Program: A Randomized Controlled Pilot Trial. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2017;69(1):28–37. Epub 2016/06/23. doi: 10.1002/acr.22960 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bartels CM, Ramly E, Panyard D, Lauver D, Johnson H, Li ZH, et al. Rheumatology Clinic Smoking Cessation Protocol Markedly Increases Quit Line Referrals. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69. WOS:000411824102004. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Brandt J, Lim SS, Ramly E, Messina M, Bartels C. EHR-Supported Staff Protocol Improves Smoking Cessation in a Diverse Rheumatology Clinic: Results of Quit Connect Dissemination Project. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72. WOS:000587568500060. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chodara AM, Ramly E, White D, Johnson H, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Bartels CM. Implementing a Staff Tobacco Cessation Protocol Increases Quit Line Referrals in a Community Rheumatology Practice. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2018;70. WOS:000447268900296. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chow E, Williams M, Giri B, Dalbeth N. Strategies to reduce the impact of smoking on rheumatoid arthritis outcomes: Clinical experience of a brief outpatient clinic screening questionnaire. Comment on "The impact of smoking on rheumatoid arthritis outcomes." By Vittecoq et al. Joint Bone Spine 2018; 85: 135–138. Joint Bone Spine. 2019;86(2):275–. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2018.09.012 WOS:000460013200029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gordon MM, Thomson EA, Madhok R, Capell HA. Can intervention modify adverse lifestyle variables in a rheumatoid population? Results of a pilot study. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2002;61(1):66–9. doi: 10.1136/ard.61.1.66 WOS:000172974300018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gordon MM, Thomson EA, Madhok R, Capell HA. Can intervention modify adverse lifestyle variables in a rheumatoid population?—Results of a pilot study. Rheumatology. 2001;40:27–. WOS:000207942000079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gracanin AG, Grubisic F, Markovic I, Milivojem I, Culo MI, Grazio S, et al. Efficiency of Spoken Medical Advice in Quitting Smoking in Patients Smokers with Rheumatoid Arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;73:1141. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-eular.3314 WOS:000346919806310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris HE, Tweedie F, White M, Samson K. How to Motivate Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis to Quit Smoking. Journal of Rheumatology. 2016;43(4):691–8. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.141368 WOS:000378169100004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.John H, Hale ED, Treharne GJ, Kitas GD, Carroll D. A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioural patient education intervention vs a traditional information leaflet to address the cardiovascular aspects of rheumatoid disease. Rheumatology. 2013;52(1):81–90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kes237 WOS:000312640300012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Karlsson ML, Pettersson S, Lundberg I. Smoking cessation in patients with rheumatic disease. Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology. 2014;43:78–. WOS:000341757300117.24446586 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan S, Butt A, Brennan E, Mohammad A, Rourke KO. Impact of Smoking Cessstion Advise in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis to Help Quit Smoking. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69. WOS:000411824100427. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Naranjo A, Bilbao A, Erausquin C, Ojeda S, Francisco FM, Quevedo JC, et al. Results of a Smoking-Cessation Program for Patients with Arthritis in a Rheumatology Department. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2013;72:849–50. WOS:000331587904624. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Naranjo A, Bilbao A, Erausquin C, Ojeda S, Francisco FM, Rua-Figueroa I, et al. Results of a specific smoking cessation program for patients with arthritis in a rheumatology clinic. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(1):93–9. doi: 10.1007/s00296-013-2851-8 WOS:000329324600012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sadhana Singh Baghel M, Ravita TD, Christy M. Impact of Nurses Counseling On Quitting Tobacco Use in Inflammatory Rheumatological Diseases (IRDs). Nur Primary Care. 2017;1(7):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tekkatte R, Williamson L, Price E, Carty S. Is a Brief Education Intervention Effective to Motivate Patients to Stop Smoking? Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2016;75:887. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-eular.5084 WOS:000401523104286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thomas A, Chitale S, Jones S. Positive Impact of Dolgellau Community Hospital Healthy Hearts Programme on Cardiovascular Risk in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: 1-Year Results. Rheumatology. 2015;54:92–3. WOS:000364513700226. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zeun P, Thoms B, Shivji S, Mmesi J, Abraham S. Stubbing it out: tackling smoking in rheumatology clinics. Rheumatology. 2015;54(8):1528–30. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kev120 WOS:000359667100029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sadhana Singh Baghel M. Effect of counselling related to Tobacco use in systemic immuno-inflammatory arthritides. Indian Journal of Rheumatology. 2016;11 (5 Supplement):S104–S5. PubMed PMID: 619194874. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Soubrier M, Perrodeau E, Gilson M, Cantagrel AG, Le Loet X, Flipo RM, et al. Impact of a nurse-led program on comorbidity management in rheumatoid arthritis (RA): Results of a prospective, multicenter, randomized, controlled trial. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 2013;65:S411. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Aimer P, Treharne G, Stebbings S, Frampton C, Cameron V, Kirby S, et al. A pilot randomized controlled trial of a tailored smoking cessation intervention for rheumatoid arthritis patients. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:S1035‐. doi: 10.1002/art.38914 CN-01049942. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Soubrier M, Perrodeau E, Gaudin P, Cantagrel A, Le Loet X, Flipo R, et al. Impact of a nurse led program on the management of comorbidities in rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Results of a prospective, multicentre, randomized, controlled trial (comedra). Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases Conference: Annual European Congress of Rheumatology of the European League Against Rheumatism, EULAR. 2013;72(SUPPL. 3). doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-204733 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Al Hamarneh YN, Marra C, Gniadecki R, Keeling S, Morgan A, Tsuyuki R. RxIALTA: evaluating the effect of a pharmacist-led intervention on CV risk in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases in a community pharmacy setting: a prospective pre-post intervention study. BMJ Open. 2021;11(3):e043612. Epub 2021/03/26. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043612 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7993291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bartels CM, Johnson L, Ramly E, Panyard DJ, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Johnson HM, et al. Impact of a Rheumatology Clinic Protocol on Tobacco Cessation Quit Line Referrals. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2021. Epub 2021/04/08. doi: 10.1002/acr.24589 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC8492788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brandt J, Ramly E, Messina M, Lim S, Bartels C. EHR-Supported Staff Protocol Improves Smoking Cessation in a Diverse Rheumatology Clinic: Updated Results of Quit Connect Dissemination. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2021;73: https://acrabstracts.org/abstract/title-ehr-supported-staff-protocol-improves-smoking-cessation-in-a-diverse-rheumatology-clinic-updated-results-of-quit-connect-dissemination/. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fiore MC, Jaén CR, Baker TB, et al. Treating Tobacco Use and Dependence: 2008 Update. Clinical Practice Guideline. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service; May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aimer P, Stamp LK, Stebbings S, Cameron V, Kirby S, Treharne GJ. Exploring perceptions of a rheumatoid arthritis-specific smoking cessation programme. Musculoskeletal Care. 2018;16(1):74–81. Epub 2017/07/07. doi: 10.1002/msc.1209 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gath ME, Stamp LK, Aimer P, Stebbings S, Treharne GJ. Reconceptualizing motivation for smoking cessation among people with rheumatoid arthritis as incentives and facilitators. Musculoskeletal Care. 2018;16(1):139–46. Epub 2017/12/14. doi: 10.1002/msc.1227 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Roelsgaard IK, Thomsen T, Ostergaard M, Semb AG, Andersen L, Esbensen BA. How do people with rheumatoid arthritis experience participation in a smoking cessation trial: a qualitative study. Int J Qual Stud Health Well-being. 2020;15(1):1725997. Epub 2020/02/13. doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1725997 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7034478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wattiaux A, Bettendorf B, Block L, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Ramly E, Piper ME, et al. Patient Perspectives on Smoking Cessation and Interventions in Rheumatology Clinics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2020;72(3):369–77. Epub 2019/02/16. doi: 10.1002/acr.23858 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6697238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stead LF, Buitrago D, Preciado N, Sanchez G, Hartmann-Boyce J, Lancaster T. Physician advice for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD000165. Epub 2013/06/04. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000165.pub4 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7064045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hartmann-Boyce J, Chepkin SC, Ye W, Bullen C, Lancaster T. Nicotine replacement therapy versus control for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;5:CD000146. Epub 2018/06/01. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000146.pub5 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6353172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wattiaux A, Bettendorf B, Block L, Gilmore-Bykovskyi A, Ramly E, Piper ME, et al. Patient Perspectives on Smoking Cessation and Interventions in Rheumatology Clinics. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2019. Epub 2019/02/16. doi: 10.1002/acr.23858 . [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roelsgaard IK, Esbensen BA, Ostergaard M, Rollefstad S, Semb AG, Christensen R, et al. Smoking cessation intervention for reducing disease activity in chronic autoimmune inflammatory joint diseases. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;9:CD012958. Epub 2019/09/03. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012958.pub2 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6718206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Scheuermann TS, Richter KP, Rigotti NA, Cummins SE, Harrington KF, Sherman SE, et al. Accuracy of self-reported smoking abstinence in clinical trials of hospital-initiated smoking interventions. Addiction. 2017;112(12):2227–36. Epub 2017/08/24. doi: 10.1111/add.13913 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5673569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Roelsgaard IK, Thomsen T, Ostergaard M, Christensen R, Hetland ML, Jacobsen S, et al. The effect of an intensive smoking cessation intervention on disease activity in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):570. Epub 2017/12/01. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-2309-5 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5706378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.