Abstract

This study of the phosphorylation ability of macrophage-like cells upon infection with Mycobacterium avium was undertaken to establish potential targets of the interference with host response mechanisms. Cytosolic and membrane fractions from noninfected and infected cells were incubated with [γ-32P]ATP, in the presence of Mg2+ and the absence of Ca2+, and the patterns of phosphoproteins synthesized were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Lower levels of a 110-kDa phosphoprotein were observed in association with cytosolic fractions from mycobacterium-infected cells compared to noninfected cells or cells treated with lipopolysaccharide or having ingested Escherichia coli or killed M. avium. The 110-kDa phosphoprotein was present in the soluble fraction (230,000 × g supernatant) after the kinase incubation, from where it was partially purified and identified as phosphonucleolin by amino acid sequencing. The decrease in nucleolin phosphorylation observed was not related to changes in the cytosolic or membrane levels of this protein, and was detected also in the cytosolic fraction of 32P-labeled intact cells.

The ability of obligate intracellular microorganisms to survive and proliferate within macrophages is a consequence of alterations at different stages of the host cell response to infection. Mycobacteria, important members of this group of microorganisms, are known to live and proliferate within phagosomes which, unlike those containing other bacteria, have been reported to be arrested in their maturation (8, 9, 29, 32). These phagosomes lack lysosomal markers (15) and fail to be acidified (10, 30, 33) as a result of an inhibition of lysosomal, endosomal, and vesicle fusion.

The molecular basis of the mycobacterium-induced impairment of macrophage functional responses is scarcely known, the most recent advance in this field being the important observation that the retention of a phagosomal protein by phagosomes containing live but not dead mycobacteria coincides with the impairment of lysosomal delivery (14). Further studies at a biochemical level are essential for the development of new strategies to fight this infection.

Along these lines, we have undertaken the investigation of the effect of Mycobacterium avium infection on the protein phosphorylation ability of human macrophage-like cells, a subject scarcely investigated to date. Lipoarabinomannan (LAM) from Mycobacterium tuberculosis has been reported to inhibit the activity of protein kinase C obtained from the macrophage cell line U937 in an in vitro assay (7). More recently, it has been demonstrated that THP-1 cells incubated with LAMs show decreased levels of tyrosine phosphorylated proteins (18).

We have examined the effect of an established M. avium infection on the phosphorylation-dephosphorylation balance of macrophage-like THP-1 cells by means of a cell-free assay containing cytosolic and membrane fractions along with [γ-32P]ATP. We report a difference in phosphoprotein patterns between noninfected and infected cells which represents a step forward in the understanding of the interactions between the mycobacterium and the host cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Preparation and culture of macrophage-like cells.

All cultures were performed in an air–7% CO2 incubator at 37°C. THP-1 cells (human monocytic leukemia) were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing 4.5 g of glucose per liter, 10 mM HEPES, 1 mM sodium pyruvate, and 10% (vol/vol) fetal bovine serum. They were induced to become adherent, elongated, macrophage-like cells by the addition of 20 nM phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate to the cultures 72 h before phagocytosis of M. avium or Escherichia coli or treatment with E. coli lipopolysaccharide (LPS). Harvesting was performed by scraping.

Culture and opsonization of bacteria.

M. avium 465/1, kindly provided by L. Fattorini and G. Orefici (Instituto Superiore di Sanitá, Rome, Italy), was grown on Middlebrook 7H11 agar (Difco, Detroit, Mich.) supplemented with 0.5% glycerol and 10% albumin-dextrose complex in anaerobic chambers for 15 to 18 days. Bacteria were scraped off, pelleted, and resuspended to a concentration of 1010 bacteria/ml. Single cell suspensions, as ascertained by microscopy, were obtained by brief sonication. Killing was performed by heating at 90°C for 45 min. Opsonization was performed by incubating the required amount of mycobacterial suspension with an equal volume of human serum for 30 min at 37°C. Serum-treated bacteria were pelleted and resuspended with 15 mM sodium phosphate–136 mM sodium chloride, pH 7.4 (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]).

E. coli DH5α was grown in Luria broth, pelleted, washed, and resuspended to 1010/ml with PBS. Killing was performed by heating at 100°C for 30 min. Either live or heat-killed bacteria were opsonized by incubation with human immunoglobulin G (1 mg/ml) for 30 min at 37°C.

Cell infection.

THP-1 cells (108) were infected overnight with opsonized live or heat-killed M. avium at bacterium/cell multiplicities of from 10:1 to 15:1. After removal of the free bacteria, cultures were continued for 3 to 5 days before harvesting and subcellular fractionation. In some time course experiments, M. avium phagocytosis was performed for 2.5 h.

E. coli ingestion experiments were performed by incubating 108 THP-1 cells with opsonized live or heat-killed bacteria at a 30:1 multiplicity, for 1 h, in the air-CO2 incubator. Cells were then washed, harvested, and fractionated.

Metabolic labeling with [32P]phosphate.

Macrophage-like THP-1 cells, noninfected or infected with heat-killed or live M. avium for 3 days (3 × 108 cells in each case), were washed twice with phosphate-free medium (PFM; consisting of 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM CaCl2, 3 mM KCl, 136 mM NaCl, 5 mM glucose, and 20 mM sodium HEPES, pH 7.4). They were then labeled by incubating them at 37°C for 1 h in the same medium containing 0.06 mCi of carrier-free [32P]orthophosphate per ml. At the end of the labeling period, cells were washed once with PFM, harvested in PFM containing 2 mM pervanadate, and subcellularly fractionated.

Subcellular fractionation.

All steps were carried out at 0 to 4°C in the presence of proteinase inhibitors (Complete; Boehringer) and, in the case of 32P-labeled cells, of proteinase inhibitors plus 2 mM pervanadate and 0.1 μM calyculin (Calbiochem). Washed cells (total number, 1 × 108 to 3 × 108) were resuspended with 1 ml of 9% (wt/wt) sucrose–10 mM PIPES [piperazine-N,N′-bis(2-ethanesulfonic acid)], pH 7.2, and disrupted by sonication (Soniprep; MSE) at an amplitude of 6 μ for 30 s (two pulses of 15 s). On some occasions cells were disrupted by repeated passage through a 23-gauge needle. Disrupted cell extracts were centrifuged at 600 × g (rmax) for 3 min to remove unbroken cells and nuclei. The turbid postnuclear supernatants were loaded onto sucrose gradients prepared by layering successively the following sucrose solutions (all given as wt/wt in 10 mM PIPES, pH 7.2): 55% (0.2 ml), 47% (0.3 ml), 40% (1.2 ml), 34% (0.8 ml), 25% (0.8 ml), and 20% (0.6 ml). The sucrose layers were allowed to diffuse into each other to linearity for 3 h at room temperature or for 1 h at 37°C to eliminate completely concentration discontinuities. The gradients were then loaded at the top with 1 ml of the postnuclear supernatants and centrifuged at 250,000 × g (rav) for 1 h. The top cytosolic fraction and then two membrane bands of increasing equilibrium density (band 1, 1.12 g/ml, and band 2, 1.31 g/ml, from top to bottom) were collected from each gradient and characterized as described below. Fraction densities were determined by refractometry.

Characterization of subcellular fractions.

Subcellular fractions were assayed for the following markers: (i) α1 subunit of the Na,K-ATPase (Western blotting), (ii) rab5 (Western blotting), (iii) clathrin (Western blotting), and (iv) β-glucuronidase activity (Sigma Diagnostics) as described previously (25). Both the endosomal marker rab5 and the coated vesicle marker clathrin were predominantly (>80%) associated to membrane band 1 (n = 4). The marker of plasma membrane origin Na,K-ATPase was found associated with band 1 in a greater proportion (>60%) than to band 2 (n = 4). The lysosomal hydrolase β-glucuronidase was found distributed between band 1 (mean, 36.3%; standard deviation [SD], 9.0%; n = 6) and band 2 (mean, 63.7%; SD, 9.0%; n = 6), which reflects a dual endosomal-lysosomal localization.

Protein kinase assay.

Reaction mixtures (total volume, 80 μl) consisted of 25 mM PIPES (pH 7.3), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 μM calyculin (Boehringer), 8 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM ATP, [γ-32P]ATP (62.5 μCi/ml), and cytosolic (15 to 30 μg) and band 1 membrane (10 to 15 μg) fractions. Incubations were performed for 30 min at 37°C unless stated otherwise and were ended by the addition of EDTA (final concentration, 12 mM). Aliquots of the incubations were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), and the gels were dried and autoradiographed. At a preliminary stage, kinase incubations were also performed by using (i) cytosolic fraction only, (ii) band 1 membranes only, or (iii) cytosolic fraction plus band 2 membranes.

Phosphoprotein quantification.

The radioactivity of bands from gels was determined either by scintillation counting or by means of a phosphorimager (Cyclone-Canberra; Packard).

Electrophoresis and immunoblotting.

SDS-PAGE was performed by loading identical amounts of protein into lanes that were to be compared with each other.

Gels (9%) to be autoradiographed were stained with Coomassie brilliant blue R-250 and dried.

Western blotting of gels was performed using Nitrocellulose-Extra membranes (Sartorius, Göttingen, Germany). The blotted membranes were blocked and probed with monoclonal antibodies against the α1 subunit of Na,K-ATPase (Upstate Biotechnology, New York, N.Y.), clathrin, and rab5 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, Ky.). Nucleolin was immunodetected using either a rabbit polyclonal antibody kindly provided by A. Ochem at our institute (31) or the D3 monoclonal antinucleolin antibody (hybridoma supernatant) from J. Deng (11). Second antibodies were peroxidase- or alkaline phosphatase-conjugated and developing was performed by enhanced chemiluminescence (Amersham) or by using chromogenic substrates.

Immunoprecipitations. (i) Phosphotyrosine.

Kinase reaction mixtures were immunoprecipitated overnight with an antiphosphotyrosine monoclonal antibody (PT-66; Sigma) at 4°C.

(ii) Nucleolin.

Cytosolic and membrane fractions from 32P-labeled cells were immunoprecipitated overnight with the D3 monoclonal antinucleolin antibody (11) at 4°C.

In both cases the procedure was done as described by Olsson et al. (23). The absorbing solid phase was Protein A/G PLUS-Agarose (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Purification of the 110-kDa phosphoprotein.

A protein kinase incubation of cytosolic and membrane fractions from noninfected cells was scaled up 15-fold and, at the end of the reaction, centrifuged at 230,000 × g (rmax) for 1 h. The 230,000 × g supernatant containing 32P-labeled P-110 was loaded on a DEAE-cellulose column (0.9 by 3.3 cm) equilibrated with 20 mM PIPES buffer (pH 7.3) at 4°C. The column was washed with 2 ml of equilibrating buffer and eluted sequentially with 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, and 1.0 M LiCl (1 ml of each). Fractions of 0.25 ml were collected throughout and analyzed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The exact position of P-110 was identified by comparison of autoradiographies corresponding to incubations using subcellular fractions from noninfected and M. avium-infected cells, which shows the infection-induced decrease of P-110 phosphorylation.

Protein sequencing.

Internal amino acid sequencing was performed on P-110 gel bands obtained by SDS-PAGE of fractions eluted with 0.5 M LiCl from DEAE-cellulose as described above. These bands were extracted and subjected to tryptic digestion, followed by fragment purification by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and Edman degradation (Eurosequence, Groningen, The Netherlands).

RESULTS

Characteristics of cell-free protein phosphorylation.

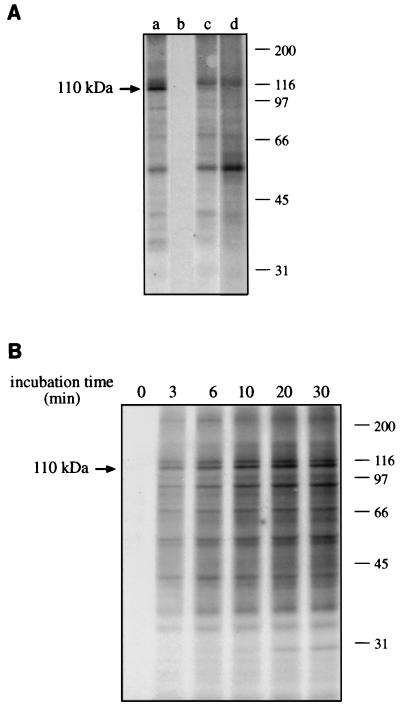

The first step in the investigation of the phosphorylation ability of mycobacterium-infected and noninfected macrophage-like cells was the study of the characteristics of a cell-free protein phosphorylation system. We determined the Mg2+-dependent kinase activity of different subcellular fractions and their combinations, in the presence of calyculin A as an inhibitor of protein phosphatases PP1 and PP2A (Fig. 1). There was no activity using the cytosolic fraction alone (Fig. 1A, lane b), whereas a number of phosphoproteins was apparent using membrane band 1 (equilibrium density, 1.12 g/ml) or band 2 (equilibrium density, 1.31 g/ml) (lanes c and d). The combination of cytosolic and membrane fractions, however, resulted in the much-increased phosphorylation of a protein of 110 kDa (lane a), which was practically absent if the cytosolic fraction was not included in the reaction. There was only a quantitative difference between cytosol plus band 1 or cytosol plus band 2 membranes, with reaction mixtures containing band 1 membranes giving a higher phosphorylation level (not shown). The time course of reaction using the combination of cytosolic and band 1 membrane fractions (Fig. 1B) showed that protein phosphorylations increased up to at least 30 min without any evidence of dephosphorylations. The Mg2+-dependence of the reaction was only partially replaceable by Mn2+, which can be the cofactor preferred by some tyrosine kinases. In fact, Mn2+ supported the phosphorylation of fewer proteins, with no additional phosphoprotein bands being detected in comparison with Mg2+ (not shown). Additionally, and supporting the poor tyrosine phosphorylation by our system, phosphotyrosine immunoprecipitation of kinase reaction mixtures showed very low levels of phosphorylation restricted to only two proteins within the range from 50 to 55 kDa (not shown).

FIG. 1.

Characteristics of the cell-free phosphorylation reaction. Kinase assays containing subcellular fractions from noninfected THP-1 cells were performed for 30 min (A) or for the times indicated (B). The incubation mixtures were analysed by SDS-PAGE and autoradiography. The molecular sizes of marker proteins (in kilodaltons) are shown on the righthand side. The position of the 110-kDa phosphoprotein is indicated on the lefthand side. (A) Results of incubations containing cytosolic plus band 1 membrane fractions (a), cytosolic fraction alone (b), band 1 membranes alone (c), and band 2 membranes alone (d). (B) Time course of incubations containing the combination of cytosolic plus band 1 membrane fractions from 0 to 30 min.

Time course of M. avium infection.

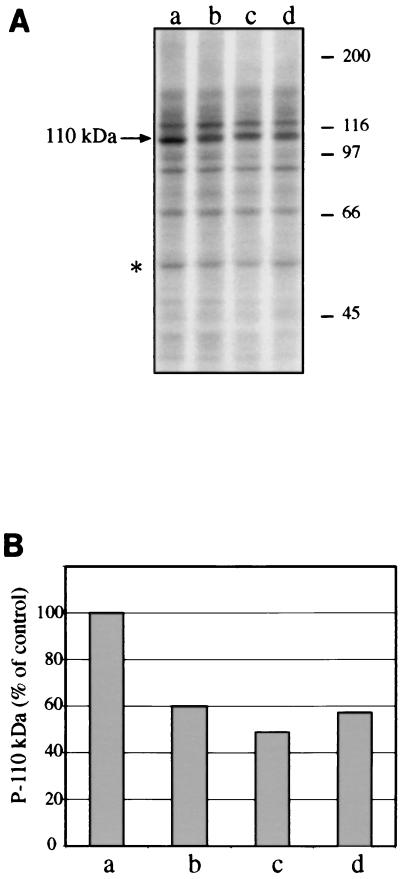

The next and main objective was to establish whether infection with mycobacteria had any influence on the phosphorylating ability of macrophages, as determined by the cell-free assay outlined above. Phosphoprotein patterns from kinase reactions containing cytosolic and membrane fractions from noninfected or M. avium-infected cells were very similar but for a sensibly diminished amount of a 110-kDa band (P-110) when the subcellular fractions incubated were from cells that had been infected for 4 days. To establish what fraction (cytosolic or/and membrane) was responsible for the effect observed, incubations were performed using cross-combinations of cytosolic and membrane fractions from noninfected and infected cells. The protein phosphorylation patterns obtained, of which the one shown in Fig. 2A is entirely representative, indicate that cytosolic fractions from infected cells only (1-, 2-, or 4-day infections), incubated with membrane fractions from either noninfected or infected cells, result in a clearly decreased amount of P-110. Therefore, the phosphorylation defect of infected cells is somehow associated with the cytosolic fraction.

FIG. 2.

Infection with M. avium results in a decrease of the phosphorylation of a 110-kDa protein. The patterns shown are from kinase assays performed using, in all cases, membrane fractions from noninfected THP-1 cells plus cytosolic fractions from either noninfected cells (a) or cells infected for 1 (b), 2 (c) or 4 (d) days, as indicated. (A) Autoradiographs of SDS-PAGE gels. Molecular size markers are shown on the right (in kilodaltons). The 110-kDa phosphoprotein (P-110) is indicated on the left. The position of the normalization band is indicated by an asterisk, on the left. (B) Radioactivity counting of P-110 bands from a gel like the one whose autoradiography is shown in panel A. The counts per minute of the P-110 band from incubation a (noninfected cells) were taken as 100% (control).

The decrease in P-110 was quantified by scintillation radioactivity counting of the corresponding gel bands and subsequent normalization with respect to a generally invariant phosphoprotein of 60 kDa which was taken as a reference to allow for the compensation of small differences among the total radioactivity of the lanes. This protein was chosen on the basis of both its high degree of phosphorylation and the absence of neighboring proteins which could result in errors due to contaminations from the band excision procedure. The radioactivity counting results (Fig. 2B) confirm those of the autoradiographs, with decreased amounts of P-110 being observed from the first to the fourth day of infection with M. avium. On some occasions the decrease was even more pronounced, as illustrated, for instance, in Fig. 3A.

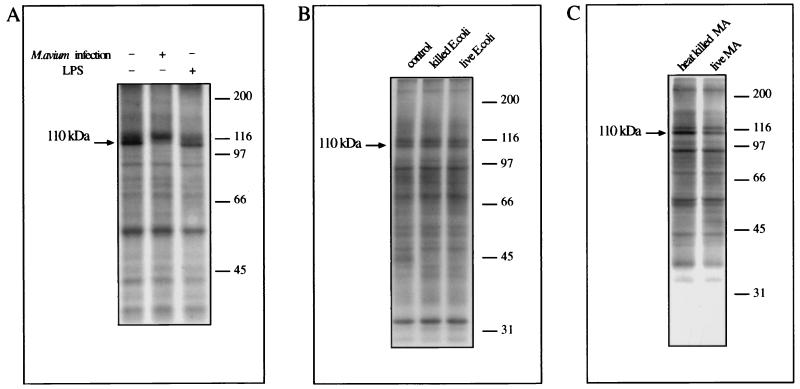

FIG. 3.

Ingestion of M. avium but not of live E. coli, heat-killed E. coli, or heat-killed M. avium or treatment with LPS leads to a lower level of P-110. Cytosolic plus band 1 membrane fractions obtained from THP-1 cells that underwent the treatments indicated were employed to perform kinase assays. Molecular size markers are indicated on the right in kilodaltons, and the 110-kDa phosphoprotein is indicated on the left. (A) Cells were cultured for 3 days without any additions, after infection with M. avium, or in the presence of LPS (10 ng/ml) as indicated. (B) Cells were incubated with no additions or with heat-killed or live E. coli for 1 h. (C) Cells were infected with heat-killed or live M. avium for 4 days.

Effect of LPS and infection with dead and live E. coli or M. avium.

In order to know whether the P-110 effect could also be obtained in circumstances other than mycobacterial infection, cells were treated with LPS for the same length of time as the M. avium infection. Kinase assays using cytosolic and membrane fractions from LPS-treated cells did not show any diminution in the amount of P-110, whereas mycobacterial infection had a pronounced effect (Fig. 3A). Moreover, no decrease in P-110 was observed when the subcellular fractions were from cells that had ingested either heat-killed or live E. coli (Fig. 3B), which also confirms the lack of effect of LPS shown in panel A. We also detected a decreased phosphorylation of the 110-kDa protein using fractions from live compared with killed M. avium. Again, the results shown were only dependent on the source of the cytosolic fraction used in the assay and not on the membrane fractions (which can be from either infected or noninfected cells).

Localization of the 110-kDa phosphoprotein.

To establish the soluble or membrane-associated character of P-110, the kinase incubation mixture was ultracentrifuged. The analysis of the ultracentrifugation supernatant and pellet by SDS-PAGE demonstrated that P-110 is exclusively present in the supernatant fraction (Fig. 4, lane a). This suggests that the nonphosphorylated protein is either soluble (cytosolic) or becomes soluble after its phosphorylation. An indication that the first possibility is likely to be true was given by kinase incubations performed keeping constant the amount of membrane fraction and increasing that of the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 5A) and vice versa (Fig. 5B). Increasing the concentration of cytosolic fraction resulted in an increase in P-110 (panel A) except for the first, very low cytosol concentration for which there was nearly no detectable P-110. This pattern is consistent with an increasing kinase substrate concentration in the cytosolic fraction. Instead, increasing the concentration of membrane fraction did not produce proportional increases in P-110 beyond the second concentration (Fig. 5B), a pattern corresponding to an increasing enzyme and/or cofactor concentration which cannot result in further substrate phosphorylation beyond the limit given by the availability of the substrate (present in the cytosol, which is fixed in panel B). These results support the idea that the nonphosphorylated protein is present in limiting amounts in the soluble (cytosolic) fraction and remains there after phosphorylation, whereas the membrane fractions would provide either the kinase or some other requirement of the reaction.

FIG. 4.

Phosphorylated 110-kDa protein (P-110) is localized in the soluble (cytosolic) fraction. A 10-times scaled-up kinase incubation of cytosolic plus band 1 membrane fractions from noninfected cells was performed as described in Materials and Methods and centrifuged at 230,000 × g for 1 h. The supernatant (lane a) and pellet (lane b) fractions were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gels were autoradiographed. The molecular sizes of marker proteins are indicated on the right in kilodaltons.

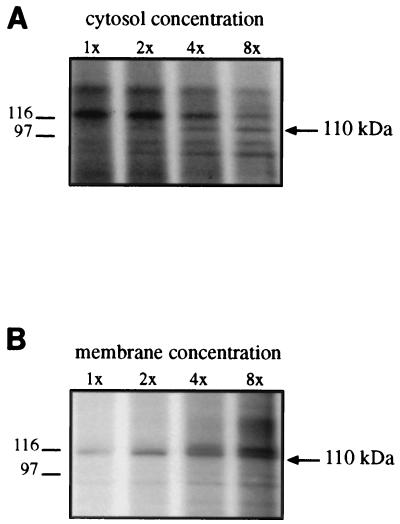

FIG. 5.

Kinetics of the phosphorylation of the 110-kDa protein. (A) Increasing cytosol concentrations and constant membrane concentration. Membranes (20 μg of protein per reaction mixture) were incubated in standard kinase assays with increasing amounts of cytosolic fraction, as indicated (1× = 8.6 μg). (B) Increasing membrane concentrations and constant cytosol concentration. Cytosolic fractions (4 μg per reaction mixture) were incubated in standard kinase assays with increasing amounts of membrane fraction, as indicated (1× = 1.7 μg). Only the relevant section of each gel is shown. Molecular sizes are indicated on the left in kilodaltons.

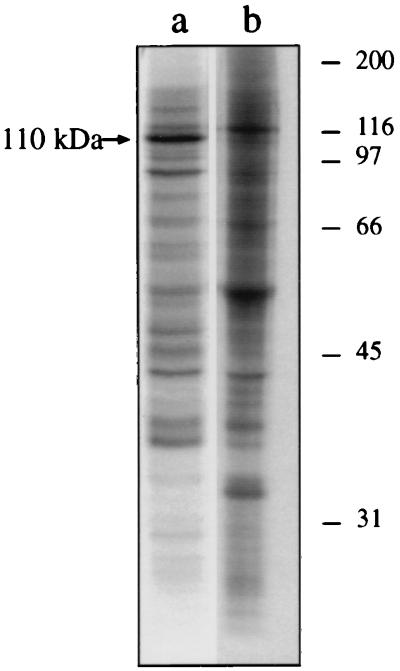

Purification and identification of P-110.

In order to identify P-110 by protein sequencing, it was necessary to purify it partially to eliminate potential contaminations with proteins of a close molecular weight which would interfere in the procedure. Ion-exchange chromatography of the ultracentrifugation supernatant from a scaled-up protein kinase reaction resulted in a clean, 32P-labeled P-110 band which eluted with 0.5 M LiCl (Fig. 6). A duplicate gel was run, and the P-110 bands of highest intensity eluting at 0.5 M LiCl were cut out and subjected to internal amino acid sequencing. Two HPLC-purified tryptic digestion fragments of 10 and 17 residues showed the following sequences: peptide 350-359, YVDFESAEDL, and peptide 577-593, GLSEDTTEETLKESFDG, which were found to be 100% homologous to human nucleolin sequences only (GenBank). There were no indications of cross-contamination with other proteins.

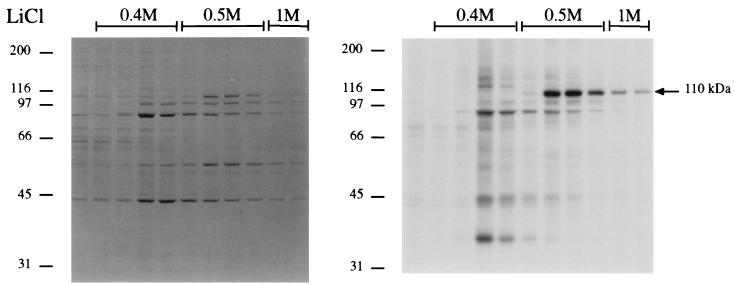

FIG. 6.

Purification of P-110 for amino acid sequencing. A 230,000 × g supernatant from a protein kinase reaction scaled up 15-fold was purified as described in Materials and Methods. Step elution was performed with LiCl at the concentrations indicated. Aliquots (0.06 ml/0.25 ml) were subjected to SDS-PAGE, and the gels were Coomassie blue stained (left panel) and then dried and autoradiographed (right panel). The arrow indicates the position of P-110. The molecular sizes of marker proteins are indicated along the left margin of each panel in kilodaltons.

The elution of nucleolin at a 0.5 M salt concentration is in agreement with the nucleolin purification procedure from nuclear extracts described by Miranda et al. (22). Subsequent to the identification of P-110 as nucleolin, the band of 110 kDa which can be seen to elute with 0.4 M LiCl (Coomassie staining panel of Fig. 6) was not recognized by the D3 monoclonal antinucleolin antibody (11), whereas the one eluting at 0.5 M LiCl reacted with it on immunoblots (not shown).

Effect of M. avium infection on nucleolin levels.

To examine the possibility of the cytoplasmic levels of nucleolin being decreased after infection with M. avium, which would lead to an apparent decrease in nucleolin phosphorylation, we probed Western blots of both cytosolic and membrane fractions from noninfected and infected macrophages with a polyclonal antibody against human nucleolin. The results obtained indicated that nucleolin is found associated with both cytosolic and membrane fractions, in agreement with previous observations (11, 20, 26–28). More importantly, they also demonstrated (Fig. 7) that there is no variation in nucleolin levels in the cytosolic fractions from noninfected cells compared with those from cells infected with M. avium for up to 5 days, with which a decrease in phosphonucleolin similar to that depicted in Fig. 2 had been observed.

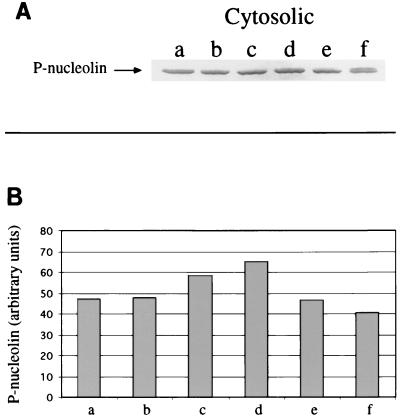

FIG. 7.

Nucleolin levels are not reduced after infection with M. avium. Cytosolic fractions from noninfected (a, c, and e) and M. avium-infected THP-1 cells harvested 1 h (b), 2 days (d), and 5 days (f) after the end of a 2.5-h infection were subjected to SDS-PAGE (50 μg/lane). The gel was Western blotted, and the membrane was probed with a rabbit anti-human nucleolin polyclonal antibody. Developing was performed by means of the alkaline phosphatase chromogenic reaction. (A) Bands obtained at the 110-kDa position, which were the only ones recognized by the antibody. (B) Quantification by densitometry of the immunoblot bands shown in panel A.

Phosphonucleolin in intact cells labeled with [32P]phosphate.

To test whether the infection-induced impairment in nucleolin phosphorylation observed using the kinase cell-free system was detectable in intact cells, we immunoprecipitated nucleolin from cytosolic and membrane fractions obtained from noninfected cells and cells infected with killed and live M. avium metabolically labeled with [32P]phosphate. It must be pointed out that whereas the cell-free system we use only allows the determination of Ca2+- and diacylglycerol-independent phosphorylations, 32P labeling of intact cells determines the “total” phosphorylation status at the time of measurement.

The results of the immunoprecipitations indicated (i) no detectable labeling of membrane fractions (not shown) and (ii) a substantial decrease of cytosolic phosphonucleolin levels after infection with M. avium compared with noninfected cells or cells that had ingested killed M. avium (Fig. 8). The latter show a small decrease of unknown relevance with respect to noninfected cells.

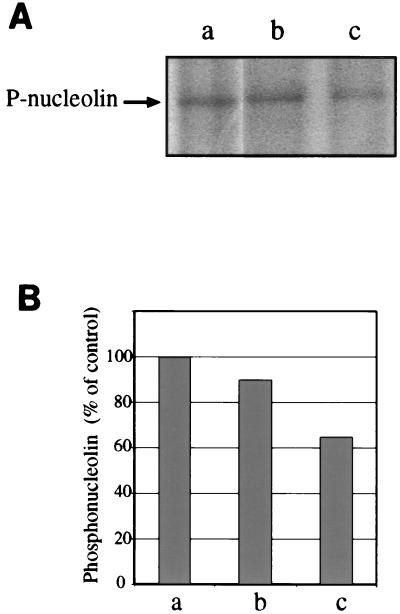

FIG. 8.

Decreased levels of phosphonucleolin in the cytosol from M. avium-infected cells labeled with [32P]phosphate. Cytosolic fractions from noninfected cells (lane a) or from cells infected with killed (lane b) or live (lane c) M. avium that had been labeled with [32P]phosphate were immunoprecipitated using a monoclonal antibody against nucleolin. (A) Autoradiography of the immunoprecipitates subjected to SDS-PAGE. (B) Quantification of the bands from panel A by a phosphorimager.

DISCUSSION

The present work shows that infection of macrophage-like cells with M. avium impairs their phosphorylation ability in a rather selective manner. We have detected a substantially diminished capacity of synthesis of a 110-kDa phosphoprotein (P-110) present in a soluble cell fraction, which was identified as nucleolin. This phenomenon is apparent throughout cell infection and is not a result of variations in nucleolin levels. The nucleolin phosphorylation impairment may be part of the mechanisms of disruption of the normal response of macrophages triggered by mycobacterial infection.

As far as phosphorylation in the host cell is concerned, only inhibitory effects of M. tuberculosis LAM on protein kinase activity (7) and protein tyrosine phosphorylation (18) have been reported to date, but no study of the direct effect of mycobacterial infection on phosphoprotein synthesis has been published. The present observations add new elements to the understanding of the biochemical events associated with host responses to mycobacteria by means of an unexplored approach.

During the last few years, important progress has been made with regard to our knowledge of the maturation arrest of mycobacterial phagosomes. This has been shown to be due to impairments of vesicle trafficking (8, 9, 29, 32), which result in failures of acidification (10, 30, 33) and of the fusion of late endosomes and lysosomes (15) or the lack of clearance of a phagosome coat protein (14). These findings need to be linked to biochemical events in order to elucidate their regulation. In this respect, phosphorylation-dephosphorylation reactions are likely to play a role, as is usually the case regarding intracellular talk mechanisms.

We report here a decrease in the capacity of macrophage-like cells to synthesize a phosphoprotein (P-110, later identified as P-nucleolin) after infection with live M. avium as opposed to killed M. avium, live or killed E. coli or after treatment with LPS. These results indicate either some degree of selectivity or, at least, a greater efficiency of the effect of live mycobacteria. The reported effect was found throughout periods of cell infection of up to 4 to 5 days; therefore, it concerns the steady-state situation established within the macrophage after a successful mycobacterial infection and not merely an early signaling event. In addition, P-nucleolin was found not to be immunoprecipitable by antityrosine antibodies.

We have identified P-110 as nucleolin by internal amino acid sequencing of the partially purified, in vitro-phosphorylated protein. We have also determined, by probing Western blots with a polyclonal antibody, that the amount of nucleolin in macrophage cytosolic and membrane fractions does not change after infection with M. avium for a period of up to 5 days. Therefore, the smaller amount of P-nucleolin in M. avium-infected cells could be due to a direct downregulation of a protein kinase(s), to an upregulation of a putative phosphatase, or to more-complex events within the interplaying reactions that regulate phosphorylation-dephosphorylation balances.

The subject is therefore raised regarding which is the relationship of nucleolin with mycobacterial infection of macrophages and the molecules involved in the regulation of its phosphorylation.

Nucleolin is a predominantly nucleolar protein of growing cells (5) that has been reported to shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm (3). It is implicated in chromatin decondensation (12), the packaging of pre-rRNA (4), and ribosomal DNA transcription (13), as well as exhibiting DNA helicase activity (31). The primary sequence of nucleolin features RNA recognition motifs, Asp-Glu-rich acidic stretches, and both serine and threonine putative phosphorylation sites. Interestingly, nucleolin has also been found associated with the cell membrane of HepG2 (11, 28), HEp-2 (11), Jurkat (20), HeLa S3 (26), and K562 (26) cells, as well as lymphocytes and macrophages (27), in agreement with our detection of membrane-associated nucleolin. Increased levels of nucleolin have been reported in splenocytes treated with a high concentration of LPS, as well as greater amounts of 32P-labeled nucleolin after incubating nuclear or cytoplasmic extracts from LPS-treated cells with [γ-32P]ATP, compared with control cells (22). The phosphorylations we performed employing subcellular fractions from LPS-treated THP-1 cells did not show differences in phosphonucleolin levels compared with control cells. This could be explained by both the lower LPS concentration we used and methodological differences in the isolation of subcellular fractions.

Nucleolin serves as a substrate for PKC-ζ (34), cdc2 (2, 24), and casein kinase II (1, 6). In fact, its functions may be regulated by phosphorylation, as has been demonstrated regarding DNA helicase activity (31). This stresses the importance of establishing which kinase(s) and phosphatase(s) determine the nucleolin phosphorylation state in noninfected and mycobacterium-infected macrophages, which phosphorylation site(s) is implicated, and whether phosphorylation determines intracellular translocations. Since the cell-free kinase system we used throughout this work consists of cytosol, membranes, and Mg2+ only, the results are consistent with either a calcium-independent, membrane-associated kinase or a phospholipid (membrane)-dependent cytosolic kinase being responsible for the phosphorylation of nucleolin which is found impaired after mycobacterial infection. Phosphorylated nucleolin was exclusively found in the soluble fraction after the kinase reaction, whereas nucleolin was immunodetected in both cytosolic and membrane fractions from the host cells and in the same relative proportions regardless of M. avium infection. Moreover, 32P labeling of intact cells allowed the detection of phosphorylated nucleolin in cytosolic but not in membrane fractions although, admittedly, the time scale of labeling might not have shown nucleolin phosphorylation if this occurred away from membranes, which would imply the subsequent transport to the membranes. Altogether, the results suggest that membrane-associated nucleolin is not likely to be phosphorylated, whereas cytosolic nucleolin is a kinase(s) substrate.

The decrease in nucleolin phosphorylation associated with mycobacterial infection could be related to only one or a few of its several phosphorylation sites. Determination of these sites, together with the identification of their kinases and kinase regulatory events, will be important for the assessment of the relevance of the observations here reported within the general phenomenon of the alteration of host cell behavior by mycobacterial intracellular infections.

It is a distinct possibility that phosphorylation events be related to cell apoptosis, particularly through Bcl-2, a protein whose phosphorylation correlates with its antiapoptotic function (16, 21). Prevention of programmed cell death can result in the possibility of a prolonged intracellular survival of mycobacteria. On the other hand, host cell apoptosis is a defense mechanism against mycobacteria. Both prevention and induction of apoptosis have been observed regarding the infection of mononuclear phagocytes with mycobacteria (17, 19).

Future work will have to address all of these questions in order to clarify further the mechanisms by which macrophage responses are disrupted.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by the National Tuberculosis Project (Istituto Superiore di Sanitá, Ministero della Sanitá, Rome, Italy) grant 96/D/T29.

The technical assistance of Barbara Sartori is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank J.-S. Deng (Department of Veterans Affairs Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pa.) for his generous gift of D3 monoclonal antibody against nucleolin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Belenguer P, Baldin V, Mathieu C, Prats H, Bensaid M, Bouche G, Amalric F. Protein kinase NII and the regulation of rDNA transcription in mammalian cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 1989;17:6625–6636. doi: 10.1093/nar/17.16.6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Belenguer P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Labbe J C, Doree M, Amalric F. Mitosis-specific phosphorylation of nucleolin by p34cdc2 protein kinase. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:3607–3618. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.7.3607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borer R A, Lehrer C F, Eppenberger H M, Nigg E A. Major nucleolar proteins shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm. Cell. 1989;56:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bugler B, Bourbon H, Lapeyre B, Wallace M O, Chang J H, Amalric F, Olson M O. RNA binding fragments from nucleolin contain the ribonucleoprotein consensus sequence. J Biol Chem. 1987;262:10922–10925. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bugler B, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Bouche G, Bourbon H, Amalric F. Detection and localization of a class of proteins immunologically related to a 100-kDa nucleolar protein. Eur J Biochem. 1982;128:475–480. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1982.tb06989.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caizergues-Ferrer M, Belenguer P, Lapeyre B, Amalric F, Wallace M O, Olson M O. Phosphorylation of nucleolin by a nucleolar type NII protein kinase. Biochemistry. 1987;26:7876–7883. doi: 10.1021/bi00398a051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan J, Fan X, Hunter S W, Brennan P J, Bloom B R. Lipoarabinomannan, a possible virulence factor involved in persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis within macrophages. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1755–1761. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1755-1761.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. Characterization of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome and evidence that phagosomal maturation is inhibited. J Exp Med. 1995;181:257–270. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clemens D L, Horwitz M A. The Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome interacts with early endosomes and is accessible to exogenously administered transferrin. J Exp Med. 1996;184:1349–1355. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.4.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Crowle A J, Dahl R, Ross E, May M H. Evidence that vesicles containing living, virulent Mycobacterium tuberculosis or Mycobacterium avium in cultured human macrophages are not acidic. Infect Immun. 1991;59:1823–1831. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.5.1823-1831.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deng J S, Ballou B, Hofmeister J K. Internalization of anti-nucleolin antibody into viable Hep-2 cells. Mol Biol Rep. 1996;23:191–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00351168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Erard M S, Belenguer P, Caizergues-Ferrer M, Pantaloni A, Amalric F. A major nucleolar protein, nucleolin, induces chromatin decondensation by binding to histone H1. Eur J Biochem. 1988;175:525–530. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1988.tb14224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Escande-Geraud M L, Azum M C, Tichadou J L, Gas N. Correlation between rDNA transcription and distribution of a 100 kDa nucleolar protein in CHO cells. Exp Cell Res. 1985;161:353–363. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(85)90092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari G, Langen H, Naito M, Pieters J. A coat protein on phagosomes involved in the intracellular survival of mycobacteria. Cell. 1999;97:435–447. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80754-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hasan Z, Schlax C, Kuhn L, Lefkovits I, Young D, Thole J, Pieters J. Isolation and characterization of the mycobacterial phagosome: segregation from the endosomal/lysosomal pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:545–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3591731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ito T, Deng X, Carr B, May W S. Bcl-2 phosphorylation required for anti-apoptosis function. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:11671–11673. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.18.11671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klingler K, Tchou-Wong K M, Brandli O, Aston C, Kim R, Chi C, Rom W N. Effects of mycobacteria on regulation of apoptosis in mononuclear phagocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:5272–5278. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.12.5272-5278.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knutson K L, Hmama Z, Herrera-Velit P, Rochford R, Reiner N E. Lipoarabinomannan of Mycobacterium tuberculosis promotes protein tyrosine dephosphorylation and inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase in human mononuclear phagocytes. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:645–652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.1.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kremer L, Estaquier J, Brandt E, Ameisen J C, Locht C. Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette Guerin infection prevents apoptosis of resting human monocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1997;27:2450–2456. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830270945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Larrucea S, González-Rubio C, Cambronero R, Ballou B, Bonay P, López-Granados E, Bouvet P, Fontán G, Fresno M, López-Trascasa M. Cellular adhesion mediated by Factor J, a complement inhibitor. Evidence for nucleolin involvement. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31718–31725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.48.31718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.May W S, Tyler P G, Ito T, Armstrong D K, Qatsha K A, Davidson N E. Interleukin-3 and bryostatin-1 mediate hyperphosphorylation of BCL2 alpha in association with suppression of apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:26865–26870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miranda G A, Chokler I, Aguilera R J. The murine nucleolin protein is an inducible DNA and ATP binding protein which is readily detected in nuclear extracts of lipopolysaccharide-treated splenocytes. Exp Cell Res. 1995;217:294–308. doi: 10.1006/excr.1995.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olsson I, Persson A M, Strömberg K. Biosynthesis, transport and processing of myeloperoxidase in the human leukaemic promyelocytic cell line HL-60 and normal marrow cells. Biochem J. 1984;223:911–920. doi: 10.1042/bj2230911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Peter M, Nakagawa J, Doree M, Labbe J C, Nigg E A. Identification of major nucleolar proteins as candidate mitotic substrates of cdc2 kinase. Cell. 1990;60:791–801. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90093-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pittis M G, Garcia R C. Annexins VII and XI are present in a human macrophage-like cell line. Differential translocation on FcR-mediated phagocytosis. J Leukoc Biol. 1999;66:845–850. doi: 10.1002/jlb.66.5.845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Qiu J, Brown K E. A 110-kDa nuclear shuttle protein, nucleolin, specifically binds to adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV-2) capsid. Virology. 1999;257:373–382. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Seddiki N, Nisole S, Krust B, Callebaut C, Guichard G, Muller S, Briand J-P, Hovanessian A G. The V3 loop-mimicking pseudopeptide 5[KΨ(CH2N)PR]-TASP inhibits HIV infection in primary macrophage cultures. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1999;15:381–390. doi: 10.1089/088922299311358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Semenkovich C F, Ostlund R E, Olson M O, Yang J W. A protein partially expressed on the surface of HepG2 cells that binds lipoproteins specifically is nucleolin. Biochemistry. 1990;29:9708–9713. doi: 10.1021/bi00493a028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schaible U E, Russell D G. Mycobacterium-containing phagosomes are accesible to early endosomes and reflect a transitional state in normal phagosome biogenesis. EMBO J. 1996;15:6960–6968. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sturgill-Koszycki S, Schlesinger P, Chakraborty P, Haddix P L, Collins H L, Fok A K, Allen R D, Gluck S L, Heuser J, Russell D G. Lack of acidification in Mycobacterium phagosomes produced by exclusion of the vesicular proton-ATPase. Science. 1994;263:678–681. doi: 10.1126/science.8303277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuteja N, Huang N W, Skopac D, Tuteja R, Hrvatic S, Zhang J, Pongor S, Joseph G, Faucher C, Amalric F, Falaschi A. Human DNA helicase IV is nucleolin, an RNA helicase modulated by phosphorylation. Gene. 1995;160:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(95)00207-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Via L E, Deretic D, Ulmer R J, Hibler N S, Huber L A, Deretic V. Arrest of mycobacterial phagosome maturation is caused by a block in vesicle fusion between stages controlled by rab5 and rab7. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13326–13331. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.20.13326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xu S, Cooper A, Sturgill-Koszycki S, van Heyningen T, Chatterjee D, Orme I, Allen P, Russell D G. Intracellular trafficking in Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium-infected macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;153:2568–2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou G, Seibenhener M L, Wooten M W. Nucleolin is a protein kinase C-ζ substrate. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:31130–31137. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.31130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]