Abstract

Background

Throughout the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers across the globe have attempted to understand how the health and socioeconomic crisis brought about by the coronavirus is affecting children’s exposure to violence. Since containment measures have disrupted many data collection and research efforts, studies have had to rely on existing data or design new approaches to gathering relevant information.

Objective

This article reviews the literature that has been produced on children’s exposure to violence during the pandemic to understand emerging patterns and critically appraise methodologies to help inform the design of future studies. The article concludes with recommendations for future research.

Participants and Setting

The study entailed a search of working papers, technical reports, and journal articles.

Methods

The search used a combination of search terms to identify relevant articles and reports published between March 1 and December 31, 2020. The sources were assessed according to scope and study design.

Results

The review identified 48 recent working papers, technical reports, and journal articles on the impact of COVID-19 on violence against children. In terms of scope and methods, the review led to three main findings: 1) Studies have focused on physical or psychological violence at home and less attention has been paid to other forms of violence against children, 2) most studies have relied on administrative records, while other data sources, such as surveys or big data, were less commonly employed, and 3) different definitions and study designs were used to gather data directly, resulting in findings that are hardly generalizable. With respect to children’s experience of violence, the review led to four main findings: 1) Studies found a decrease in police reports and referrals to child protective services, 2) mixed results were found with respect to the number of calls to police or domestic violence helplines, 3) articles showed an increase in child abuse-related injuries treated in hospitals, and 4) surveys reported an increase in family violence.

Conclusions

This review underscores the persistent challenges affecting the availability and quality of data on violence against children, including the absence of standards for measuring this sensitive issue as well as the limited availability of baseline data. Future research on COVID-19 and violence against children should address some of the gaps identified in this review.

Keywords: Violence, Children, COVID-19, Surveys

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted many aspects of children’s lives and may be putting children around the world at a greater risk of violence. Many of the factors associated with such violence have been exacerbated by COVID-19. Violence at home, for instance, is linked to parental stress, financial hardship and poor mental health (Cicchetti & Carlson, 1989; Jewkes, 2002; Zeanah & Humphreys, 2018). These issues may have deepened with the spread of the disease and with its associated economic and social impacts (Ramaswamy & Seshadri, 2020; Xiong et al., 2020). Likewise, children’s increased presence online might be tied to other forms of violence, such as cyberbullying and online abuse (Yang, 2021). School closures and national lockdowns have also meant that teachers and healthcare workers, who usually identify and report instances of child maltreatment (Feng, Huang, & Wang, 2010; Kenny, 2001; Nayda, 2002), are no longer interacting regularly with children.

Violence against children is a serious issue. In the short term, it can lead to severe injuries, dangerous coping behaviors, and even death (Hillis, Mercy, & Saul, 2017). In the long run, it can impair children’s health and development, lead to mental health issues, and contribute to unintended pregnancies and communicable diseases (Ramaswamy & Seshadri, 2020). What is more, children who are exposed to violence are more likely to be victims or perpetrators of violence in the future, in turn affecting new generations (Capaldi, Knoble, Shortt, & Kim, 2012; Tharp et al., 2013). It is therefore imperative that we understand how the current health crisis is affecting children’s exposure to violence, since such exposure may trigger wide-ranging and long-lasting impacts. Since containment efforts have disrupted many data collection and research efforts, studies have often had to rely on evidence from previous crises, existing data or design new approaches to gathering relevant information.

Studies of past epidemics have documented impacts on the experience and reporting of violence against children, as well as changes in the delivery of violence prevention and response services. Research conducted during Ebola outbreaks in West and Central Africa found increased reporting of physical violence by children and by community members, resulting from heightened parental stress and tension, children’s increased presence at home and sexual exploitation (International Rescue Committee, 2019; United Nations Development Programme, 2015). There is also evidence of widespread disruptions to child welfare structures and community, and child protection responses (Overseas Development Institute, 2015). During the 2017 cholera outbreak in Yemen, children with sick caregivers slept alone outside treatment centers, which led to an increased risk of sexual violence, particularly among girls (The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Emergencies, 2018). Despite these examples, evidence on the impacts of previous health crises on violence against children is scarce, and mostly obtained from qualitative studies, thus resulting in limited data (Fraser, 2020).

This article reviews the early literature that has been produced on children’s exposure to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic to understand emerging patterns and critically appraise methodologies to help inform the design of future studies. This article then discusses the difficulties in studying COVID-19 and violence against children and illustrates ways researchers have found to fill gaps in available data. The article concludes with recommendations for future research.

2. Methods

The World Health Organization (WHO) (2020) identifies six types of violence against children: 1) physical maltreatment and neglect, 2) bullying, 3) youth violence, 4) intimate partner violence, 5) sexual violence, and 6) emotional and psychological violence. This article uses these categories to review the available evidence. The following keyword groups were searched in PsycINFO, Sociological Abstracts, and Google Scholar: 1) child, children, 2) adolescent, adolescence, 3) COVID-19, coronavirus, and 4) violence, with the following variations of: 4.1) physical punishment, maltreatment, harsh parenting, 4.2.) bullying, cyberbullying, 4.3) gang, gangs, community violence, 4.4) intimate partner violence, gender-based violence, child marriage, 4.5) sexual abuse, rape, harassment, voyeurism, online exploitation, and 4.6) emotional abuse, psychological abuse, witness violence.

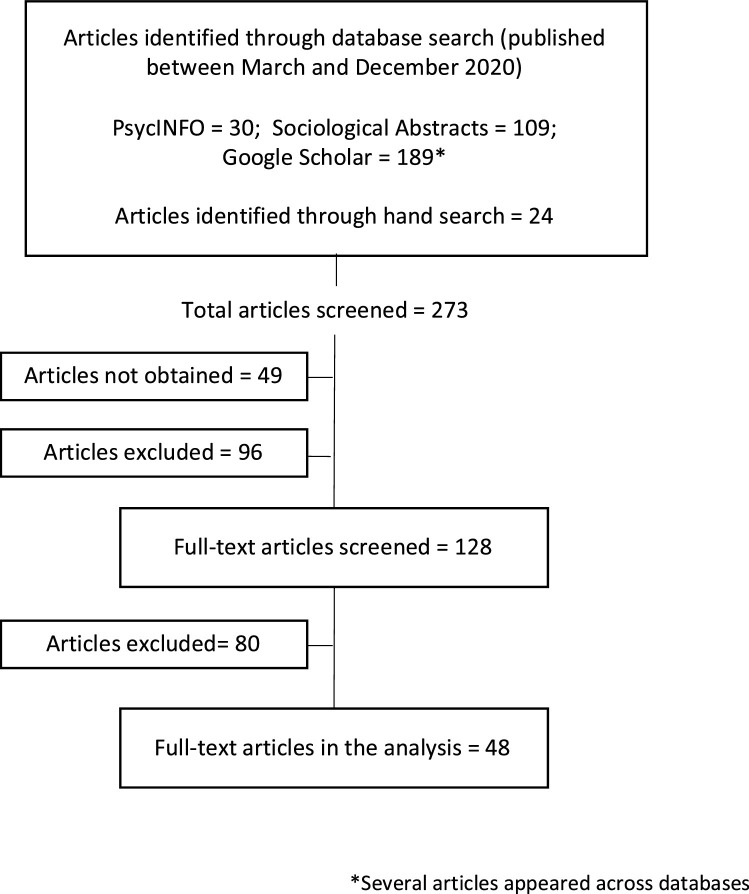

The search included published journal articles, studies produced by non-governmental organizations (NGOs) (labeled here as technical reports), and manuscripts submitted to academic journals that can be found in online repositories such as the Social Science Research Network (labeled here as working papers). Working papers that had not undergone the peer-review process at the time of the search were included because this article contends with an ongoing situation and is an analysis of preliminary research. The search was conducted between October 2020 and January 2021 and only articles published between March 2020 and December 2020 were included. PsycINFO returned 30 articles, Sociological Abstracts 109, and Google Scholar 189. Several articles appeared in at least two of these databases. Twenty-four articles were also reviewed through a manual search using the Google search engine. A total of 273 individual articles were screened.

All articles not written in English and that did not include data were excluded (i.e., opinion pieces, letters to the editor, commentaries, etc.). Articles focusing on COVID-19’s impact on crime in general (such as burglary, theft, and murder), as well as articles on people’s attitudes towards domestic violence and child abuse were excluded as well. Titles and abstracts were reviewed to determine eligibility. Full-text articles were then obtained and read. Fig. 1 outlines the selection process. Forty-eight articles were found. Thematic inductive analysis was used to identify the main themes and findings that are summarized in the following section (Nowell, Norris, White, & Moules, 2017).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA model of the article selection process.

3. Findings

Forty-eight papers published between March and December 2020 were identified (the main characteristics of these papers are summarized in Annex 1). Twenty-one articles studied COVID-19 and violence against children in the United States and Canada, five in Europe, three in Latin America and the Caribbean, three in sub-Saharan Africa, and three in South Asia. East Asia and Oceania were covered by two articles each and the Middle East and North Africa was only studied by one article. Eight papers studied COVID-19 and violence against children in more than one country or region of the world. Most of these studies reported preliminary findings, although some are part of larger, ongoing projects. Moreover, the majority of them examined how violence against children is changing (25), how children’s access to services is changing (6), or both (15), while 2 articles probed other issues.

From an inductive review of these articles, seven main findings emerged. Three of these findings concern the scope of the research, strengths and limitations of different methods used to arrive at the findings, and types of data sources, while four relate to children’s experience of violence during the pandemic.

Finding 1. Studies focused mostly on violence within the home, and more specifically on physical maltreatment and neglect, as well as emotional and psychological violence. Studies rarely investigated other forms of violence against children, often because they did not ask children themselves about their experiences.

In order to curb the spread of COVID-19, governments restricted people’s movement and instituted stay-at-home policies. By April 2020, one-third of the world’s population was under lockdown (Buchholz, 2020). Therefore, the first finding is unsurprising: most research on COVID-19 and violence against children has focused on violence within the home.

Although all studies were interested in understanding whether such violence has increased during the pandemic, a few also examined the specific stressors that can lead to violence. Brown, Doom, Lechuga-Peña, Watamura, and Koppels (2020), for instance, discussed how in the United States, parental anxiety and depression, more than the pandemic itself, correlates with a higher risk of violence. They found that greater parental support and perceived control during the pandemic are associated with lower perceived stress and child abuse potential. Another example is the Beland, Brodeur, Haddad, and Mikola (2020) study in Canada. They found that employment status and work arrangement are not related to family stress or violence, but that having difficulty fulfilling financial obligations or maintaining social ties is. In other words, parents who work from home or are unemployed but not under financial or social duress are less likely to engage in family or domestic violence.

Among the studies that focus on family violence, most of them did not specify who the perpetrator of violence is. It is assumed that it is a parent or caregiver, not a sibling or elderly relative. A study on intrafamilial sexual abuse and a study of sibling violence against children with disabilities are the exceptions (Tener et al., 2020; Toseeb, 2020).

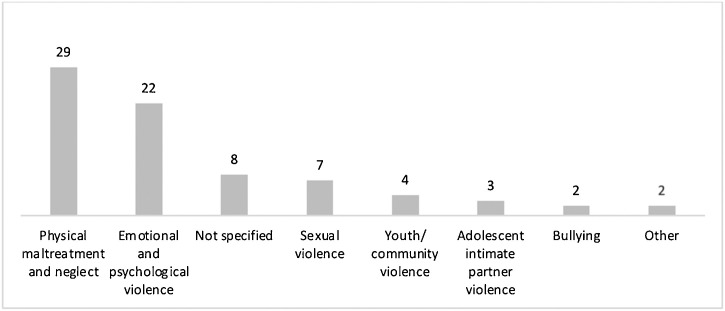

In terms of types of violence, almost three-quarters of all reviewed articles discussed physical maltreatment and neglect, emotional and psychological violence, or both. Only seven studies focused on sexual violence, usually within the domestic context. Sexual violence is usually studied along with physical, emotional, and psychological violence; only two reports were found that examined COVID-19’s impact on sexual violence, gender-based violence, and/or adolescent intimate partner violence specifically (International Rescue Committee, 2020; Tener et al., 2020). At least eight studies did not differentiate between domestic violence and violence against children (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Number of articles per type of violence against children.

Note: 21 articles cover more than one form of violence.

Four studies discussed youth or community violence, with mixed results. McKay, Metzl, and Piemonte (2020) draw from the United States’ Gun Violence Archive and argue that stay-at-home orders have reduced gun violence in public settings or schools (but increased injuries at home). Jones et al. (2020) analyzed interviews with adolescents in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Jordan and the State of Palestine, and their participants talked about an increase in community violence, as well as an increase in police brutality. Parkes et al. (2020) made similar claims regarding adolescents in Uganda. Boys are more likely to describe an increase in community violence than girls, probably because girls are more confined to their households. These arguments are difficult to compare, given the different types of data used and the different social contexts.

While the search revealed dozens of studies of COVID-19 and intimate partner violence among adults, only two studies spoke to the specific situation of adolescents. One report claimed that adolescent girls in Ethiopia are more scared of child marriage and intimate partner violence currently than before the pandemic (Jones et al., 2020). A survey of refugee and displaced girls and women in 15 African countries likewise stated that 73 percent of participants reported an increase in intimate partner violence (International Rescue Committee, 2020).

Finally, only two articles on COVID-19 and bullying were found. Babvey et al. (2020) examined bullying on social media. The authors argued that, since March, there has been a significant increase in abusive and hateful content and cyberbullying on Twitter. Jain, Gupta, Satam, and Panda (2020) studied cyberbullying among adolescents and young adults in India. They found an increase in time spent on social media and online gaming, which is associated with an increase in stalking, derogatory comments, leaking pictures and videos online, and harassment.

Finding 2. Most studies relied on administrative records, while other data sources, such as surveys or big data, were less commonly employed.

Around half of the studies relied on administrative records from police, child protection services, hospitals or helplines. This type of data reflects reporting of incidents of violence and cannot be used to determine whether violence against children has increased or decreased (UNICEF, 2020b). However, some of the studies had, as their objective, to report on the prevalence of victimization and made statements about actual victimization on the basis of such records.

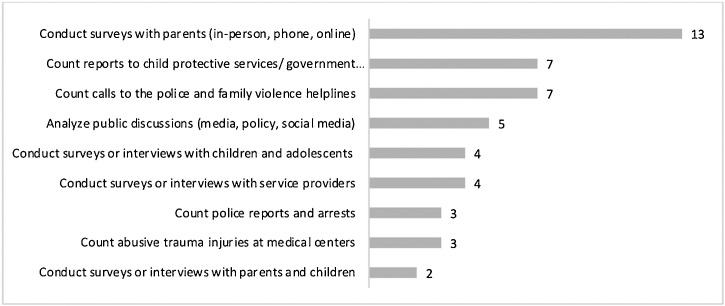

Twenty-two studies analyzed data from surveys. Thirteen surveyed parents only, 4 surveyed children and adolescents only, 2 surveyed both parents and children, and 4 interviewed service providers reporting on their perception of what has occurred to children (Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 3.

Number of articles per type of method used.

Among the six articles that describe findings reported by children and adolescents is a survey of adolescents and young adults in India (Jain et al., 2020). Also included are qualitative interviews with adolescents in Uganda (Parkes et al., 2020) and in Bangladesh, Ethiopia, Jordan and the State of Palestine (Jones et al., 2020), qualitative interviews with girls and women in refugee, displaced and post-conflict settings in Africa (International Rescue Committee, 2020), and one survey in the Netherlands with both parents and adolescents aged 15–18 (Tierolf, Geurts, & Steketee, 2020). Another study conducted in 37 countries surveyed parents and adolescents ages 11–17 (Save the Children, 2020a). Unlike the studies that surveyed parents alone, studies that focused on or included children tended to address a wider variety of forms of violence, not just physical maltreatment and neglect or emotional and psychological violence.

Finding 3. Different definitions and study designs were used to gather the data, resulting in findings that are hardly generalizable.

While most of the studies reached similar conclusions, the findings are hardly generalizable and comparable, given the significant differences in scope, definitions and study design. Indeed, a vast range of approaches were used to arrive at the findings. In the case of surveys of parents, a few studies involved participants who had children between specific age ranges – between ages 4 and 10, for instance (Lawson, Piel, & Simon, 2020; Takaku & Yokoyama, 2020) – or with specific characteristics, such as children with special educational needs (Toseeb, 2020). The rest only specified that they were interviewing mothers, parents, or caregivers in general with children under the age of 18.

Most parent and caregiver surveys examined disciplinary practices at home, such as harsh parenting (spanking or yelling) or child abuse potential (parental distress, rigidity, or parent-child conflict) (11 studies). Some asked about parents’ perception of violence in other households (2 studies). In most surveys, parents provided self-report data – for example, when parents were asked whether they had spanked their child (Lawson et al., 2020). However, in a few cases they reported on what had occurred to their children – for instance, when parents were asked if their child had been hurt by someone else within the household (Toseeb, 2020). Eight studies asked parents about violence directly, for instance asking respondents whether they agreed with the statement “I swore or cursed my child” or “I hit him/her on the bottom with a belt” (Lawson et al., 2020). Six studies, however, did not ask parents about violence but assessed risk factors, such as parental stress or depression, child behavioral problems or prosocial behavior, and family rigidity or conflict. For example, the surveys asked respondents whether they agree with statements such as “My family fights a lot,” “Children should never disobey,” or “A child needs very strict rules” (Brown, Doom, Lechuga-Peña, Watamura, & Koppels, 2020). Finally, two studies did not describe nor did they provide examples of the types of questions they asked (Poonam, Shama, & Tyagi, 2020; Rashid et al., 2020).

The sample sizes in these surveys ranged from 51 to more than 20,000 participants. Only two of the surveys had representative samples, a study in Japan (Takaku & Yokoyama, 2020) and a study in Uganda (Mahmud & Riley, 2021). Takaku and Yokoyama (2020) employed random sampling from about 4.8 million people across the nation who had preregistered as potential survey participants. The Uganda study was part of a larger longitudinal project, allowing researchers to compare the experiences of people before and during the pandemic. Researchers in the Netherlands similarly built on a previous study of domestic violence and child abuse to examine changes after the start of COVID-19 and nationwide lockdowns, although these researchers did not have a representative sample (Tierolf et al., 2020). Most of the other studies recruited participants through social media, such as Facebook ads or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk, or through pre-existing networks, and the majority did not report response rates. With the exception of the Uganda and Netherlands studies, most parent surveys could not compare current findings to pre-existing baseline data. They identified an increase in violence against children by asking parents to assess change, for instance asking if they “yelled/screamed at child(ren) more often” or “spanked or caned child(ren) more often” since the start of the pandemic (Chung, Lanier, & Wong, 2020), or asking parents about their actions in the past year and then asking about their actions in the past week (Lawson et al., 2020).

Some studies used standardized question banks, such as the Child Abuse Potential Inventory (Brown et al., 2020), the Conflict Tactics Scale, Parent-Child version (Lawson et al., 2020; Tierolf et al., 2020), the Multidimensional Neglectful Behavior Scale Parent Report (Bérubé et al., 2020), or the Child-Parent Relationship Scale (Russell, Hutchison, Tambling, Tomkunas, & Horton, 2020). Others develop their own measurements for harsh parenting (Chung et al., 2020) or domestic violence (Sharma & Tyagi, 2020). Most studies did not report instrument validity or reliability for these new instruments. Most studies also did not define the concepts used to report on violence against children, although all researchers cite the scholarly literature in order to justify their operationalization of each concept.

Of the six studies that surveyed or interviewed children, only three included information on their ethical protocols and ethical review process (Parkes et al., 2020; Save the Children, 2020a; Tierolf et al., 2020). These research projects received clearance from the Save the Children U.S. Ethics Review Committee (Save the Children, 2020a), the University College London Institute of Education, the Uganda Virus Research Institute and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (Parkes et al., 2020), and the Ethical Review Board of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (Tierolf et al., 2020).

Finding 4. Studies found a decrease in reports and referrals to police and child protective services.

Ten of the reviewed studies examined police reports on domestic violence and referrals to ombudsman offices or child protective services. Given that such data are usually compiled over several years, researchers were able to make comparisons and examine changes in patterns.

Most of these studies found that there has been no change or a decrease in referrals, reports, and arrests. One study, for instance, compares police reports in 16 major United States cities over the past few years and argues that there has been no difference in the frequency of serious assaults in residences since COVID-19 response measures (Ashby, 2020). Other papers found a decline in police reports of child abuse in Los Angeles (Barboza, Schiamberg, & Pachl, 2020) and Dallas (Piquero et al., 2020), for example. Researchers similarly showed that there are fewer referrals to child protective services in New York (Rapoport, Reisert, Schoeman, & Adesman, 2020), Florida (Baron, Goldstein, & Wallace, 2020), Georgia (Bullinger, Boy et al., 2020), Indiana (Bullinger, Raissian, Feely, & Schneider, 2020), and Mexico (Cabrera-Hernández & Padilla-Romo, 2020).

This literature, at first glance, would seem to suggest a decrease in certain forms of violence against children. Researchers, however, caution against this interpretation. As Rapoport et al. (2020) note, educators and health-care professionals are often the ones making abuse referrals. Therefore, stay-at-home measures may not mean a decrease of violence in practice, only a decrease in the people witnessing the effects of that violence. These authors and others call on teachers, social workers, doctors, and nurses to be vigilant, even if only through the online learning or telehealth format.

Likewise, some researchers write about the problems with inferring conclusions from aggregate data. Barboza et al. (2020) find a decrease in police reports on violence against children in Los Angeles, but they also identify “hotspots” of child abuse and neglect in places of severe housing burden, school absenteeism, and financial stress. They recommend considering the data by area, not the city level. Similarly, Piquero et al. (2020) found a decrease in the overall number of police reports in Dallas, but a short spike in reports in the two weeks following stay-at-home orders. They want researchers to more closely examine the timing of police reports. And Anderberg, Rainer, and Siuda (2020) showed that, in London, there was a slight increase in police reports of domestic violence, but a significant increase in searches for domestic violence-related terms online. These researchers invite others to consider alternative sources of data.

Finding 5. Studies find mixed results in terms of calls to the police and helplines.

While reports, referrals, and arrests regarding family violence and violence against children are in decline, another set of articles (seven in total) argues that there has been an increase in 911 calls and calls to family and domestic violence helplines. Authors find an upsurge in 911 calls in several major cities in the United States (Bullinger, Carr et al., 2020; Hsu & Henke, 2020; Sanga & McCrary, 2020; Mohler et al., 2020). One paper specifically shows an increase in calls from certain city blocks. In their study of domestic violence in 14 U.S. metropolitan areas, Leslie and Wilson (2020) argued that, compared to 2019, 2020 saw more calls from blocks without a history of domestic violence and less calls from blocks with this history.

Authors also pointed to varying patterns with respect to changes in calls to domestic violence helplines. In Mexico, one study argued that domestic violence calls for legal services have gone down, but domestic violence calls for psychological services have remained the same or increased during certain weeks of the pandemic (Silverio-Murillo, Balmori de la Miyar, & Hoehn-Velasco, 2020). In Argentina, another study concluded that, when compared to trends from the past three years, a national helpline received fewer calls from the police, but more from the victims of violence (Perez-Vincent & Carreras, 2020). A study comparing 48 child helplines spanning 45 countries showed mixed results (Petrowski, Cappa, Pereira, Mason, & Daban, 2020). Petrowski and colleagues found that the overall number of calls to the helplines has increased. However, the calls related to violence against children have only increased in about half the countries analyzed, while they decreased in the rest of the cases. This decrease may be explained by the fact that teachers and other adults who often report cases to helplines and hotlines are no longer in frequent and close contact with children. Lockdowns and living in close quarters with perpetrators may also limit children’s opportunities to safely reach out for help. Furthermore, they may not be aware that these services are still available.

Finding 6. Studies of hospital data found an increase in abuse-related injuries.

Three of the reviewed articles examined hospital data, which showed an increase in physical intimate partner violence and physical child abuse injuries in the United Kingdom and the United States, compared to the three years prior (Gosangi et al., 2020; Kovler et al., 2020; Sidpra, Abomeli, Hameed, Baker, & Mankad, 2021). By showing an increase in extreme cases, the authors make a case for an increase in violence against women and children overall. Gosangi et al. (2020), for instance, found that while patients are less likely to report domestic or family violence during COVID-19, medical professionals are more likely to treat injuries related to family violence compared to 2017, 2018, and 2019.

Finding 7. Surveys report an increase in violence.

Fifteen of the studies reviewed are based on surveys with parents and caregivers. These studies make very consistent claims. Around the world (Save the Children, 2020a) and in Bangladesh (Rashid et al., 2020), Canada (Beland et al., 2020; Bérubé et al., 2020), India (Poonam et al., 2020), Japan (Takaku & Yokoyama, 2020), the Netherlands (Tierolf et al., 2020), New Zealand (Overall, 2020), Singapore (Chung et al., 2020), Uganda (Mahmud & Riley, 2021), the United Kingdom (Toseeb, 2020), and the United States (Brown et al., 2020; Lawson et al., 2020; Russell et al., 2020; Ward & Lee, 2020), parents and caregivers reported an increase in violence against children in the home since the start of the pandemic. Most parents and caregivers admit that since March they are more violent than before – for instance, when asked whether since the outbreak of COVID-19 they are “[resorting] to physical punishment too often” (Save the Children, 2020b).

Four studies also reported findings from surveys with service providers. For instance, a survey of 87 NGO representatives in 43 countries indicated that most providers perceive an increase in children’s exposure to violence, especially physical and emotional maltreatment within the home, higher rates of community violence outside the home, and a higher risk of witnessing violence (Wilke, Howard, & Pop, 2020). Likewise, a study of staff in refuges for child survivors of domestic violence in Norway showed that staff are particularly worried about vulnerable children during the pandemic, even though they received fewer requests from clients (Øverlien, 2020). As with the parent surveys, these studies capture the change service providers perceive in the communities they assist.

4. Discussion

This article has reviewed early studies on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on violence against children. Seven findings have emerged, three on the scope and methods of these studies and four on the actual results. The methodological review revealed a focus on certain forms violence (physical and psychological within the family context), while other forms, such as sexual violence, community violence, and adolescent intimate partner violence have been less investigated. Studies were also found to use different definitions of violence against children and inconsistent study designs, and to rely on administrative data sources, while surveys and especially big data were used less often. In terms of results, studies found decreases in police reports and referrals to child protective services regarding violence against children, increases in violence-related injuries, as well as mixed results with respect to calls to police or domestic violence helplines. Surveys reported a perceived or actual increase in family violence, as reported by service providers or parents/caregivers.

4.1. Implications

This review underscores the persistent challenges affecting the availability and quality of data on violence against children. This includes the absence of established, internationally agreed standards for measuring and producing statistics on this sensitive issue as well as the limited availability of baseline data on certain forms of violence (Cappa & Petrowski, 2020). These data issues make it difficult to make broader claims about the changing patterns of violence against children during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Different methods, definitions and protocols were used to derive findings about changes in children’s experience of violence, which have resulted in studies of varying scope and quality. In some cases, the studies did not report on whether measures were put in place to ensure the rigorous implementation of the study protocols, nor did they clarify if data collection was undertaken with adequate mechanisms to safeguard the protection of the participants. The absence of information on ethical protocols for the surveys that involved children is of particular concern, given that the COVID-19 crisis brought up additional issues in terms of privacy and confidentiality (UNICEF, 2020a).

While it is undeniably important to understand violence against children in the domestic context during COVID-19 given stay-at-home restrictions, this focus nonetheless overlooked possible changes in other forms of violence. For example, limited evidence exists on the effect COVID-19 has had on online abuse. As more children study, socialize, and play on the Internet, researchers must be attentive to the possible risks that children face online. This should occur alongside the assessment of how the crisis has possibly reduced the occurrence of other forms of violence.

The assessment of changes in the number of calls to helplines, child protective service referrals, police reports, or hospital records is useful because it is indicative of changes in outreach and services utilization. These administrative data, however, cannot reveal the actual prevalence of violence against children (UNICEF, 2020b) and cannot be used to report on changes in children’s experiences.

There are several limitations to using online surveys to study violence against children. First, survey studies can rarely be compared to baseline data. Participants are asked about their experiences before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. This subjective understanding – influenced by bias, memory, level of assessment or mood – does not necessarily reflect the incidence of violent episodes. Second, while online surveys allow researchers to investigate COVID-19 and violence against children more quickly, the majority of the studies examined here did not survey representative samples of the population. Many researchers relied on Facebook ads or Amazon’s Mechanical Turk to disseminate their projects. Researchers made an effort to capture different demographic groups, but there is an inherent bias in who chooses to respond to an online survey.

Despite the shortcomings of some of the studies and findings, this review shows that researchers are finding innovative solutions in order to address data problems and respond to research questions. Some researchers used creative methodologies to engage children. Haffejee and Levine (2020) invited children in South Africa to draw and write about their experiences during lockdown. Jones and colleagues used a virtual participatory research model, meaning that researchers interacted with children online, individually and in groups (see Melachowska et al., 2020 for a detailed methodological description). Other researchers are also harnessing the power of social media. Xue, Chen, Chen, Hu, and Zhu (2020) examined how conversations about domestic violence and violence against children are changing on Twitter. Babvey et al. (2020) analyzed testimonials on violence on Reddit forums. Finally, Fabri and colleagues used statistical modelling to estimate the possible effects of COVID-19 on children’s experiences of violent discipline using pre-COVID data from large nationally representative surveys in three low- and middle-income countries. The authors developed a model of how the COVID-19 pandemic could affect risk factors for violent discipline. Country-specific multivariable linear models were then used to estimate the association between risk factors and children’s experience of violent discipline under a “high restrictions” pandemic scenario approximating conditions expected during a period of intense response measures, and a “lower restrictions” scenario with easing of COVID-19 restrictions but with sustained economic impacts (Fabbri et al., 2020).

4.2. Limitations

The articles reviewed here may not represent all current discussions of COVID-19 and violence against children. The articles skew to North America, probably given the language requirement; this may also reflect the fact that the majority of research on violence against children is conducted in this region. It makes it difficult to generalize results, also in light of the differences in the spread of the virus and the measures taken by governments to contain it. For instance, while China and later France implemented lockdown measures and internal mobility restrictions, Sweden has not imposed a full lockdown, has not restricted mobility, and has not closed schools, gyms, and restaurants, choosing instead to encourage people to exercise self-restraint (Yan, Zhang, Wu, Zhu, & Chen, 2020). Therefore, studies that discuss the pandemic’s impact on violence against children in one context cannot capture the pandemic’s impact in another. More comparative research is needed to ascertain the pandemic’s impact around the world.

There may also be articles currently in the review process that are not yet available for analysis. This preliminary review, however, does offer a first look at the research landscape. This will allow scholars, practitioners, and policymakers to recognize initial patterns in children’s experience of violence during COVID-19 and understand some of the methodological challenges and shortcomings that affect current research. This also points to overlooked areas that need to be studied and understood further, and adjustments to methods that can lead to more robust studies.

5. Conclusion

The reviewed articles illustrate the opportunities and challenges faced by researchers studying COVID-19 and violence against children. Future research on COVID-19 and violence against children should address the knowledge gaps and methodological shortcomings identified in this review. Representative surveys should be conducted when it is safe to do so and should include standardized measurement tools. Investments in strengthening the quality and availability of administrative data should be prioritized.

Footnotes

Supplementary material related to this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105053.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Anderberg D., Rainer H., Siuda F. 2020. Quantifying domestic violence in times of crisis (No. 8593). CESifo Working Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Ashby M.P. Initial evidence on the relationship between the coronavirus pandemic and crime in the United States. Crime Science. 2020;9:1–16. doi: 10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1186/s40163-020-00117-6.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babvey P., Capela F., Cappa C., Lipizzi C., Petrowski N., Ramirez-Marquez J. Using social media data for assessing children’s exposure to violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104747. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barboza G.E., Schiamberg L.B., Pachl L. A spatiotemporal analysis of the impact of COVID-19 on child abuse and neglect in the city of Los Angeles, California. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104740. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baron E.J., Goldstein E.G., Wallace C.T. 2020. Suffering in silence: How COVID-19 school closures inhibit the reporting of child maltreatment. (forthcoming). Available at SSRN 3601399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beland L.P., Brodeur A., Haddad J., Mikola D. 2020. COVID-19, family stress and domestic violence: Remote work, isolation and bargaining power. (No. 571). Global Labor Organization Discussion Paper. [Google Scholar]

- Bérubé A., Clément M.È., Lafantaisie V., LeBlanc A., Baron M., Picher G., et al. How societal responses to COVID-19 could contribute to child neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104761. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S.M., Doom J.R., Lechuga-Peña S., Watamura S.E., Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchholz K. 2020. What share of the world population is already on COVID-19 lockdown? Statista.com. Published April 23, 2020. (Accessed October 29, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L., Boy A., Feely M., Messner S., Raissian K., Schneider W., et al. 2020. COVID-19 and alleged child maltreatment. Available at SSRN 3702704. [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L.R., Carr J.B., Packham A. 2020. COVID-19 and crime: Effects of stay-at-home orders on domestic violence. National Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 27667. [Google Scholar]

- Bullinger L., Raissian K., Feely M., Schneider W. 2020. The neglected ones: Time at home during COVID-19 and child maltreatment. Available at SSRN 3674064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera-Hernández F., Padilla-Romo M. University of Tennessee, Department of Economics; 2020. Hidden violence: How COVID-19 school closures reduced the reporting of child maltreatment. Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi D.M., Knoble N.B., Shortt J.W., Kim H.K. A systematic review of risk factors for intimate partner violence. Partner Abuse. 2012;3:231–280. doi: 10.1891/1946-6560.3.2.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappa C., Petrowski N. Thirty years after the adoption of the Convention on the Rights of the Child: Progress and challenges in building statistical evidence on violence against children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104460. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung S.K.G., Lanier P., Wong P. Mediating effects of parental stress on harsh parenting and parent-child relationship during coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic in Singapore. Journal of Family Violence. 2020 doi: 10.1007/s10896-020-00200-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D., Carlson V., editors. Child maltreatment: Theory and research on the causes and consequences of child abuse and neglect. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1989. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-98324-000 [Google Scholar]

- Fabbri C., Bhatia A., Petzold M., Jugder M., Guedes A., Cappa C., et al. Modelling the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on violent discipline against children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104897. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng J.Y., Huang T.Y., Wang C.J. Kindergarten teachers’ experience with reporting child abuse in Taiwan. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(2):124–128. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser E. VAWG Helpdesk; London: 2020. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on violence against women and girls, VAWG helpdesk research report No. 284. [Google Scholar]

- Gosangi B., Park H., Thomas R., Gujrathi R., Bay C.P., Raja A.S., et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown. Radiology. 2020;298(1):E38–E45. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020202866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haffejee S., Levine D.T. “When will I be free?” Lessons from COVID-19 for child protection in South Africa. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104715. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillis S.D., Mercy J.A., Saul J.R. The enduring impact of violence against children. Psychology, Health & Medicine. 2017;22(4):393–405. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1153679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu L.C., Henke A. 2020. The effect of social distancing on police reports of domestic violence. Available at SSRN. [Google Scholar]

- International Rescue Committee . International Rescue Committee; New York: 2019. “Everything on her shoulders”: Rapid assessment on gender and violence against women and girls in Beni, DRC. [Google Scholar]

- International Rescue Committee . International Rescue Committee; New York: 2020. What happened? How the humanitarian response to COVID-19 failed to protect women and girls. [Google Scholar]

- Jain O., Gupta M., Satam S., Panda S. Has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the susceptibility to cyberbullying in India? Computers in Human Behavior Reports. 2020;2 doi: 10.1016/j.chbr.2020.100029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewkes R. Intimate partner violence: Causes and prevention. Lancet. 2002;359(9315):1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08357-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones N., Małachowska A., Guglielmi S., Alam F., Abu Hamad B., Alheiwidi S., et al. Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence; London: 2020. I have nothing to feed my family…. COVID-19 risk pathways for adolescent girls in low-and middle-income countries. Report. [Google Scholar]

- Kenny M.C. Child abuse reporting: Teachers’ perceived deterrents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2001;25(1):81–92. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00218-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovler M.L., Ziegfeld S., Ryan L.M., Goldstein M.A., Gardner R., Garcia A.V., et al. Increased proportion of physical child abuse injuries at a level I pediatric trauma center during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104756. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson M., Piel M.H., Simon M. Child maltreatment during the COVID-19 pandemic: Consequences of parental job loss on psychological and physical abuse towards children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104709. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leslie E., Wilson R. 2020. Sheltering in place and domestic violence: Evidence from calls for service during COVID-19. Available at SSRN 3600646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmud M., Riley E. University of Exeter Open Research; 2021. Household response to an extreme shock: Evidence on the immediate impact of the COVID-19 lockdown on economic outcomes and well-being in rural Uganda. Working paper. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay T., Metzl J., Piemonte J. 2020. Effects of statewide coronavirus public health measures and state gun laws on American gun violence.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3680050 Available at SSRN 3680050. [Google Scholar]

- Melachowska A., Jones N., Abu Hamad B., Al Abbadi T., Al Almaireh W., Alheiwidi S., et al. Gender and Adolescence: Global Evidence; London: 2020. GAGE virtual research toolkit: Qualitative research with young people about their COVID-19 experiences.https://scholar.google.com/scholar_lookup?title=GAGE%20virtual%20research%20toolkit%3A%20Qualitative%20research%20with%20young%20people%20about%20their%20COVID-19%20experiences&author=A.%20Melachowska&publication_year=2020 [Google Scholar]

- Mohler G., Bertozzi A.L., Carter J., Short M.B., Sledge D., Tita G.E., et al. Impact of social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic on crime in Los Angeles and Indianapolis. Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2020.101692. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nayda R. Influences on registered nurses’ decision‐making in cases of suspected child abuse. Child Abuse Review: Journal of the British Association for the Study and Prevention of Child Abuse and Neglect. 2002;11(3):168–178. doi: 10.1002/car.736. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nowell L.S., Norris J.M., White D.E., Moules N.J. Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods. 2017;16(1):1–13. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1609406917733847 [Google Scholar]

- Overall N. PsyArXiv Preprints; 2020. Sexist attitudes and family aggression during COVID-19 lockdown.https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2021-28244-001 Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Øverlien C. The COVID‐19 pandemic and its impact on children in domestic violence refuges. Child Abuse Review. 2020 doi: 10.1002/car.2650. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/car.2650 (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overseas Development Institute . ODI; London: 2015. Special feature: The Ebola crisis in West Africa, no. 64.https://odihpn.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/he_64.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Parkes J., Datzberger S., Howell C., Kasidi J., Kiwanuka T., Knight L., et al. 2020. Young people, inequality and violence during the COVID-19 lockdown in Uganda.https://osf.io/preprints/socarxiv/2p6hx/ Working paper. SocArXiv papers. [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Vincent S., Carreras E. 2020. Evidence from a domestic violence hotline in Argentina. Chapter 1 in: Inter-American Development Bank technical note Nº IDB-TN.https://publications.iadb.org/publications/english/document/COVID-19-Lockdowns-and-Domestic-Violence-Evidence-from-Two-Studies-in-Argentina.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Petrowski N., Cappa C., Pereira A., Mason H., Daban R.A. Violence against children during COVID-19: Assessing and understanding change in use of helplines. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104757. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piquero A.R., Riddell J.R., Bishopp S.A., Narvey C., Reid J.A., Piquero N.L. Staying home, staying safe? A short-term analysis of COVID-19 on Dallas domestic violence. American Journal of Criminal Justice. 2020:1–35. doi: 10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s12103-020-09531-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poonam S., Sharma K., Tyagi P. Correlates of domestic violence in relation to physical health and perceived stress during lockdown. Shodh Sarita. 2020;7(27):66–71. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344073584_Correlates_of_domestic_violence_in_relation_to_physical_health_and_perceived_stress_during_lockdown_sodha_sarita [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy S., Seshadri S. Children on the brink: Risks for child protection, sexual abuse, and related mental health problems in the COVID-19 pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 2020;62(Suppl 3):S404. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1032_20. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7659798/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rashid S.F., Aktar B., Farnaz N., Theobald S., Ali S., Alam W., et al. 2020. Fault-lines in the public health approach to COVID-19: Recognizing inequities and ground realities of poor residents’ lives in the slums of Dhaka City, Bangladesh.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3608577 Available at SSRN 3608577. [Google Scholar]

- Russell B.S., Hutchison M., Tambling R., Tomkunas A.J., Horton A.L. Initial challenges of caregiving during COVID-19: Caregiver burden, mental health, and the parent–child relationship. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2020;51(5):671–682. doi: 10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10578-020-01037-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapoport E., Reisert H., Schoeman E., Adesman A. Reporting of child maltreatment during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic in New York City from March to May 2020. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104719. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanga S., McCrary J. 2020. The impact of the coronavirus lockdown on domestic violence.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3612491 Available at SSRN 3612491. [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children . 2020. Protect a generation: The impact of COVID-19 on children’s lives. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/protect-generation-impact-covid-19-childrens-lives. Published September 10, 2020. (Accessed January 8, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Save the Children . 2020. The hidden impact of COVID-19: On children, research design and methods. https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/library/hidden-impact-covid-19-children-global-research-series. Published September 10, 2020. (Accessed January 11, 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., Tyagi P. 2020. Correlates of domestic violence in relation to physical health and perceived stress during lockdown.https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Pooja-Tyagi-5/publication/344073584_Correlates_of_domestic_violence_in_relation_to_physical_health_and_perceived_stress_during_lockdown_sodha_sarita/links/5f510acd299bf13a319c2c0d/Correlates-of-domestic-violence-in-relation-to-physical-health-and-perceived-stress-during-lockdown-sodha-sarita.pdf Working paper. [Google Scholar]

- Sidpra J., Abomeli D., Hameed B., Baker J., Mankad K. Rise in the incidence of abusive head trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2021 doi: 10.1136/archdischild-2020-319872. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverio-Murillo A., Balmori de la Miyar J.R., Hoehn-Velasco L. 2020. Families under confinement: COVID-19, domestic violence, and alcohol consumption. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research paper series.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3688384 (in press) [Google Scholar]

- Takaku R., Yokoyama I. 2020. What school closure left in its wake: Contrasting evidence between parents and children from the first COVID-19 outbreak.https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Papers.cfm?abstract_id=3693484 Available at SSRN 3693484. [Google Scholar]

- Tener D., Marmor A., Katz C., Newman A., Silovsky J.F., Shields J., et al. How does COVID-19 impact intrafamilial child sexual abuse? Comparison analysis of reports by practitioners in Israel and the US. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104779. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tharp A.T., DeGue S., Valle L.A., Brookmeyer K.A., Massetti G.M., Matjasko J.L. A systematic qualitative review of risk and protective factors for sexual violence perpetration. Trauma, Violence & Abuse. 2013;14(2):133–167. doi: 10.1177/1524838012470031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Alliance for Child Protection in Humanitarian Emergencies . The Alliance for Child Protection in Emergencies. 2018. The guidance note on the protection of children during infectious disease outbreak.https://alliancecpha.org/en/child-protection-online-library/guidance-note-protection-children-during-infectious-disease [Google Scholar]

- Tierolf B., Geurts E., Steketee M. Domestic violence in families in the Netherlands during the coronavirus crisis: A mixed method study. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toseeb U. PsyArXiv; 2020. Sibling conflict during COVID-19 in families with special educational needs and disabilities. Working paper https://psyarxiv.com/7fgcn/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund . New York; New York: 2020. Research on violence against children during the COVID-19 pandemic: Guidance to inform ethical data collection and evidence generation.https://data.unicef.org/resources/research-on-violence-against-children-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-guidance/ [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children’s Fund . UNICEF; New York: 2020. Strengthening administrative data on violence against children: Challenges and promising practices from a review of country experiences.https://data.unicef.org/resources/strengthening-administrative-data-on-violence-against-children/ [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Development Programme . UNDP; New York: 2015. Ebola recovery in Sierra Leone: tackling the rise in sexual and gender-based violence and teenage pregnancy during the Ebola crisis.https://www.undp.org/content/undp/en/home/librarypage/crisis-prevention-and-recovery/recovering-from-the-ebola-crisis---full-report.html [Google Scholar]

- Ward K.P., Lee S.J. Mothers’ and fathers’ parenting stress, responsiveness, and child wellbeing among low-income families. Children and Youth Services Review. 2020;116 doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105218. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (WHO) 2020. Violence against children.https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/violence-against-children Published June 2, 2020. (Accessed October 24, 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Wilke N.G., Howard A.H., Pop D. Data-informed recommendations for services providers working with vulnerable children and families during the COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104642. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong J., Lipsitz O., Nasri F., Lui L.M., Gill H., Phan L., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2020;277:55–64. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue J., Chen J., Chen C., Hu R., Zhu T. MedRXiv; 2020. Abusers indoors and coronavirus outside: An examination of public discourse about COVID-19 and family violence on Twitter using machine learning. Working paper https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.08.13.20167452v1. [Google Scholar]

- Yan B., Zhang X., Wu L., Zhu H., Chen B. Why do countries respond differently to COVID-19? A comparative study of Sweden, China, France, and Japan. The American Review of Public Administration. 2020;50(6-7):762–769. doi: 10.1177/0275074020942445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F. Coping strategies, cyberbullying behaviors, and depression among Chinese netizens during the COVID-19 pandemic: A web-based nationwide survey. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2021;281:138–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeanah C.H., Humphreys K.L. Child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;57(9):637–644. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2018.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.