Abstract

Research has consistently shown that access to parks and gardens is beneficial to people’s health and wellbeing. In this paper, we explore the role of both public and private green space in subjective health and wellbeing during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak that took place in the UK in the first half of 2020. It makes use of the longitudinal COVID-19 Public Experiences (COPE) study, with baseline data collected in March/April 2020 (during the first peak) and follow-up data collected in June/July 2020 (after the first peak) which included an optional module that asked respondents about their home and neighbourhood (n = 5,566). Regression analyses revealed that both perceived access to public green space (e.g. a park or woodland) and reported access to a private green space (a private garden) were associated with better subjective wellbeing and self-rated health. In line with the health compensation hypothesis for green space, private gardens had a greater protective effect where the nearest green space was perceived to be more than a 10-minute walk away. This interaction was however only present during the first COVID-19 peak when severe lockdown restrictions came into place, but not in the post-peak period when restrictions were being eased. The study found few differences across demographic groups. A private garden was relatively more beneficial for men than for women during but not after the first peak. The results suggest that both public and private green space are an important resource for health and wellbeing in times of crisis.

Keywords: Green space, Gardens, Subjective wellbeing, Self-rated health, COVID-19

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The rapid spread of the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 resulted in lockdowns across the world in a desperate bid to prevent further transmission of the disease. Within two weeks of the World Health Organisation declaring a pandemic (Cucinotta & Vanelli, 2020), the UK government imposed a strict nationwide lockdown on the 23rd of March 2020. The Welsh Government introduced similar measures for Wales, as did administrations of the other devolved UK nations (Colfer, 2020). For the first 2–3 months of the lockdown, individuals were only permitted to leave their home for essential travel, such as food shopping, and for outdoor exercise once a day. The lockdowns at start of the pandemic are thought to have saved millions of lives (Flaxman et al., 2020) due to reduced mobility (Badr et al., 2020, Paez, 2020) and therefore transmission of the disease (Courtemanche et al., 2020, Paez et al., 2021), but raised concerns about their impact on people’s mental health as a result of stress, substance abuse, anxiety, and loneliness (Galea et al., 2020, World Health Organization, 2020). Indeed, early evidence has shown increased prevalence of poor mental health and wellbeing during the early stages of the pandemic (e.g. Holttum, 2020, Karatzias et al., 2020, Li and Wang, 2020, Pappa et al., 2020).

A growing literature has shown that (perceived) access to green space plays an important role in people’s health and wellbeing (Houlden et al., 2018, Twohig-Bennett and Jones, 2018), and that it can act as a buffer against stressful life experiences (Van den Berg et al., 2010). The restrictions to people’s movement and assembly were unprecedented, highlighting the importance of having nearby green spaces to maintain physical and mental health (Gray & Kellas, 2020). A recent study, conducted in six European countries, found that individuals expressed a great need for spending time in urban green spaces during the pandemic, and that they were seen as places of solace and respite as well as for exercise and relaxation (Ugolini et al., 2020). Visits to urban green spaces were missed the most in countries with the most severe restrictions (ibid).

In this paper, we will examine the role of perceived access to green space at different time periods during the COVID-19 outbreak, making use of a longitudinal dataset that was collected during the first peak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the UK as lockdown restrictions were being introduced (March/April 2020) and immediately post-peak as lockdown restrictions were beginning to be eased (June/July 2020).

1.2. Green space, health and wellbeing

A wealth of research has pointed to the beneficial effects of green space and experiences with nature in terms of health and wellbeing (Maas et al., 2006). The association between (perceived) access to green space and health has been evidenced across a range of contexts, with one systematic review of 143 studies concluding that exposure to green space is linked to reduced incidence of stroke, hypertension, asthma and coronary heart disease (Twohig-Bennett & Jones, 2018). In addition to research supporting the positive role of green space in physical health, there is evidence to its psychological benefits. One study that identified a clear link with access to green space and mental wellbeing showed that individuals who reported visiting nature the day prior were happier, and those who visited nature regularly perceived their lives to be more worthwhile (White et al., 2017). Studies extend this finding through illustrating the role of nature experiences on life satisfaction (Biedenweg et al., 2017), eudaimonic and hedonic happiness (Passmore & Howell, 2014), personal growth (Pritchard et al., 2020) and psychological resilience (Buchecker & Degenhardt, 2015).

Nature has been shown to act as a buffer against the impact of life stressors. For example, Hazer et al. (2018) identified a significant reduction in perceived stress for every hour per week of exposure to green space, which would equate to an additional $2,210 in annual household income or 45 min of vigorous exercise. A second study utilised a large nationwide student survey across 42 Chinese cities found that green space plays a role in reducing uncertainty stress, and to a lesser extent life stress (Yang et al., 2019). Thompson et al. (2012) show that quantity of green space is associated with lower levels of self-reported stress and diurnal cortisol among residents living in economically deprived areas. The use of more objective biomarkers of stress alongside self-reported measures of stress provides clear converging evidence that green space can help mitigate physiological stress responses.

In a study of child psychological wellbeing, Wells and Evans (2003) demonstrated that nearby nature can help to moderate the effect of stressful events (such as family relocation or school punishment) on psychological distress and self-worth. Van den Berg and colleagues (2010) further highlight the role of green space as a potential buffer against negative life experiences. They show that the presence of green space in people’s living environment mitigates negative impacts of stressful life events on physical and general health. They found similar but weaker buffering effects for mental health. In line with these findings, Ottosson and Grahn (2008) show that green space can act as a buffer at times of personal crisis. Their study found that experiencing nature (e.g. by taking a walk or observing green landscapes) particularly benefits the rehabilitation of people who were greatly affected by a personal crisis, such as a divorce or death of a loved one, as compared to those who were less affected by such as crisis.

It is not only the presence but also the perceived distance and accessibility of green space that drives their use and benefits. Perceived travel distance is a main factor in the frequency of visits to per-urban green spaces (Žlender & Thompson, 2017), with users being six times more likely to visit green space for physical exercise if they perceive it to be nearby (Zuniga-Teran et al., 2019). People living further than 1 km from green space are far less likely to use them to keep in shape (Toftager et al., 2011). Using the Neighbourhood Environment Walkability Scale, Sugiyama et al. (2008) identified a significant association between perceived access to green environments and mental health. Dadvand et al. (2016) further illustrate the importance of perceived proximity to greenspace as an indicator for general health as opposed to objective measures of distance. The study found that subjective residential proximity to green spaces was associated with better self-reported general health measures, while results for measures of objective proximity were inconclusive. Evidence shows that the use of green and blue spaces for physical activity and recreational purposes can at least in part explain the link between perceived distance and physical and mental health (cf., Hartig et al., 2014). Völker et al. (2018) shows that the link between perceived walking distance and mental health was mediated by blue space use. Nielsen and Hansen (2007) similarly found that the health effects of perceived distance to green space reflect their conduciveness to outdoor activities. Sugiyama et al. (2008) concluded that the relationship between greenness and mental health was only partly accounted by recreational walking.

1.3. Access to public and private green space

Research thus far has mostly focused on the health effects of public green spaces such as parks, rather than on the health effects of private green spaces such as gardens. Many studies combined private or shared gardens with public green spaces within a given radius (e.g. Triguero-Mas et al., 2015, White et al., 2017) or left them out completely (e.g. Mitchell and Popham, 2007, Van den Berg et al., 2010, Völker et al., 2018). Yet, domestic gardens are common in the UK, covering about a third of urban areas in terms of space (ONS, 2020). Gardens may play an important role in people’s health and wellbeing as they provide opportunities for socialisation, physical activity and relaxation, which have been shown to reduce stress and provide benefits in terms of mental and physical health. Indeed, a recent English study (De Bell et al., 2020) found that respondents who engaged in garden-related activities (such as relaxing and gardening) reported better health and wellbeing, more physical activity, and more nature visits than those who did not. The study further considered different types of outdoor space (such as patios, balconies), but concluded that only reported access to a private garden was associated with better wellbeing. The role of garden use as an important health resource is in line with prior research on the perceived restorativeness of private gardens (Cervinka et al., 2016). Dennis and James (2017) analysed the relationship between public green spaces and gardens on local health deprivation in North West England and found that both public and private green space were negatively associated with health deprivation at the population level. They concluded that domestic gardens mitigate health deprivation more effectively than public green space at all levels of urbanity apart from the most rural areas. A population-level survey showed that garden size played a significant role on self-reported health, with areas with small gardens displaying greater income-related health inequalities (Brindley et al., 2018). This highlights that garden access and quality may play a key role in the buffering effect of nature regarding health and wellbeing.

Evidence shows that private gardens –just as public green spaces– may act as a buffer against stress. Nielsen and Hansen (2007) found that reported access to a private or shared garden was negatively correlated with levels of self-reported stress. A Swedish study showed that reported access to a garden at the workplace may play a positive role in “trivsel” (a Scandinavian term that encompasses comfort, pleasure and wellbeing) and subsequently stress-reduction (Stigsdotter & Grahn, 2004). Research has additionally demonstrated the role of gardens across a range of mental health dimensions. For example, one study utilised semi-structured interviews to highlight the role of gardens on the mental health of people with dementia (Liao et al., 2020). Staff members of care facilities reported positive effects of garden-use on mood, depression, and agitation levels. The study further pointed to the role of gardens on cognition, with reported improvements in attention and time orientation after garden use.

Maat and De Vries (2006) proposed that there is an interplay in the use of public and private green spaces, which they termed the compensation hypothesis. The hypothesis holds that people with less green space in their direct residential environment are more likely to visit public green space and natural areas as compensation. Strandell and Hall (2015) found some support for the compensation hypothesis. Their study showed a relationship between density of residential environment and time spent at a second home, with respondents without gardens using second homes more frequently. However, others have obtained evidence for that contradicts the compensation hypothesis. De Bell and colleagues (2020) found that people who use their own garden more frequently also visit nature away from their home more regularly. Similarly, Lin et al. (2014) found that public park users spend more time in their own private garden as compared to non-park users, which they attribute to differences in ‘nature orientation’ reflecting the value and relevance of nature to people’s life.

The compensation hypothesis of Maat and De Vries (2006) specifically relates to a potential substitution effect in the usage of different types of green spaces. Despite a wealth of evidence showing that both access to public and private green space are associated with a range of health outcomes, very few studies have explored the potential for compensatory effects in terms of health and wellbeing. We propose that access to public green space may compensate for the absence of a private garden in terms of health and wellbeing, which we refer to as the health compensation hypothesis for green space. The hypothesis holds that access to public green space is a stronger buffer against negative life experiences for people who do not have access to a private garden. The hypothesis can also be formulated in reverse: access to a private green space (i.e. a garden) has a stronger health protective effect where people have restricted access to public green space. The health compensation hypothesis can be seen as an extension of the compensation hypothesis (Maat and De Vries, 2006) in that when and where access to public parks is limited, potential negative effect for health and wellbeing may be buffered by access to a private garden. Equally, having access to public green spaces nearby may compensate for the absence of a private garden in dealing with stress and adverse life experiences.

1.4. Aim of the study

The aim of the current research is to explore the potential benefits of public and private green space during and after the first peak in COVID-19 infections in the UK, with associated lockdown restrictions coming into force and subsequently being gradually eased in the first half of 2020. More specifically, it examines whether (1) perceived access to public green space (e.g. a park or woodland) and reported access to a private green space (a private garden) are associated with better subjective wellbeing and self-rated health, (2) having access to a private garden has a protective effect where there is a lack of perceived access to public green space (the ‘health compensation hypothesis’ of green space), and (3) certain social and demographic groups benefit more from public green space and private garden access than others. Most research thus far has focused on the benefits of public green spaces and private gardens. Here we report on the role of the two types of green space in conjunction to examine potential compensatory effects in terms of health and wellbeing during a time of crisis (Spring 2020), when there were wide-ranging restrictions being implemented on freedom of movement, as well as when the most severe restrictions were (temporarily) lifted in the UK (Summer 2020).

2. Data and methods

2.1. COPE

The data were obtained from the COVID-19 Public Experiences (COPE) mixed-methods study that consists of a longitudinal online survey and qualitative interviews. A total of 11,112 responses were collected between the 13 March and 14 April 2020 with most participants recruited through Health Wise Wales (HWW), an existing national longitudinal study funded by the Welsh Government (Hurt et al., 2019). Additional respondents were recruited online via social media platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. The COPE study is a longitudinal study with the same respondents being represented in the baseline and follow-up surveys. Those who consented to follow-up at the baseline survey were sent an individualised link to the 3-month survey via e-mail, which included a unique identifier to enable us to link the baseline and 3-month data. No new participants were recruited for the follow-up survey. Of all baseline respondents, 89.0% gave consent to be recontacted for the follow-up surveys. Responses for the 3-month follow up were collected between 20 June and 20 July 2020. In total, 7,049 follow-up responses were received, a response rate of 63.4% from baseline and 71.2% from those who consented.

The COPE surveys covered a wide-range of topics, including behavioural responses and activities during the COVID-19 pandemic, measures of mental and physical health, trust in information, and general background/socio-demographic information. The follow-up survey included an optional module with questions on access to gardens and green space, with 5,566 responses (79.0% the follow-up respondents). The respondents answering the follow-up survey were the same persons in the during the peak. We make use of both the baseline and follow up data for the 5,566 respondents that were collected during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic when lockdown was coming into force in the UK (March/April 2020), and after the most severe restrictions were eased (June/July 2020) when retailers were allowed to reopen and many schools had reopened including in Wales. The 5-mile ‘stay local’ travel restrictions for Wales were lifted on 6 July 2020.

2.2. Measures

The study had two outcome variables: subjective wellbeing and self-rated health. Subjective wellbeing was measured using three items from the SF36 scale (Item 1: “Have you felt calm and peaceful?”, Item 2: “ Did you have a lot of energy?”, and Item 3: “ Have you felt downhearted and blue “). After reversing Item 3, a scale was created by averaging the three items, with higher scores indicating better psychological well-being. The resulting scale ranged from 0 “none of the time” to 5 “All the time”. The scale had good reliability (Cronbach’s α = 0.77 peak, and 0.82 post-peak). Self-rated health was measured by asking respondents “How is your health in general?” The response options were: 1 “poor”, 2 “Fair, 3 “Good”, 4 “Very Good” and 5 “excellent”. The scale is considered a good indicator of subjective wellbeing and physical health (Idler & Benyamini, 1997).

Perceived access public to public green space was indicated by responses to the question “How far away from your home is your nearest green space area? (e.g. park, playing field, public garden, woodland, or other green space). A distinction was made between Less than a 5-minute walk, Within a 5–10 min walk and>10 min walk. Table 1 shows that most respondents (64.2%) lived within a 5 min walk; around a quarter (23.9%) lived within a 5–10 min walk; and around one in nine (11.2%) lived > 10 min walk away from the nearest public green space. These numbers are comparable to research conducted in 2017 in Scotland, which found that 64.3% lived within a 5-minute walk, 20.3% living within 5–10 min walk, and 15.3% > 10 min walk away from the nearest green space (Scottish Government, 2018). Access to a private garden was measured by asking what option best applied to respondents’ homes (response options: ‘I have access to my own garden’, ‘I have access to a communal garden’, ‘ I have access to private outdoor space but not a garden (e.g. balcony, yead, patio area, driveway), and ‘I don’t have access to a garden or private outdoor space’). A distinction was made between “I have access to my own garden” and all other options to capture the significance of having access to private green space. Table 1 shows that most respondents (91.7%) had access to a private garden. This is slightly higher than national figures showing that around one in eight households in Great Britain has no access to a private or shared garden during the coronavirus; and around four in five has access to a private garden (ONS, 2020). There was an association between perceived distance to nearest public green space and reported access to a private garden, with access to a private garden increasing from 85.8% when a park is perceived to be > 10 mins away, to 89.7% when a park is perceived to be 5–10 mins away, and 93.7% when a park is perceived to be < 5 mins away. This however does not lead to problems with multi-collinearity, with a value inflation factor (VIF) of 1.00 for the two measures.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the COPE neighbourhood dataset (n = 5,566) and descriptive statistics for subjective wellbeing and self-rated health during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Subjective wellbeing |

Self-rated health |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak | Post-peak | Peak | Post-peak | |||

| n | % | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |

| Perceived access to public green space | ||||||

| < 5 min walk | 3,572 | 64.2 | 2.84 (1.07) | 3.02 (1.09) | 3.56 (0.99) | 3.46 (1.02) |

| 5–10 min walk | 1,328 | 23.9 | 2.71 (1.07) | 2.83 (1.13) | 3.35 (1.04) | 3.26 (1.04) |

| > 10 min walk | 622 | 11.2 | 2.53 (1.07) | 2.65 (1.15) | 3.10 (1.08) | 2.97 (1.10) |

| Private garden | ||||||

| Yes | 5,105 | 91.7 | 2.79 (1.07) | 2.96 (1.10) | 3.47 (1.12) | 3.38 (1.04) |

| No | 456 | 8.2 | 2.55 (1.12) | 2.56 (1.18) | 3.21 (1.12) | 3.07 (1.08) |

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 3,832 | 68.9 | 2.60 (1.05) | 2.77 (1.09) | 3.46 (1.02) | 3.36 (1.04) |

| Male | 1,721 | 30.9 | 3.17 (1.02) | 3.28 (1.09) | 3.41 (1.04) | 3.34 (1.06) |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–30 | 260 | 4.7 | 2.17 (1.04) | 2.29 (1.03) | 3.70 (0.93) | 3.59 (1.00) |

| 31–40 | 528 | 9.5 | 2.35 (0.99) | 2.40 (1.06) | 3.59 (0.98) | 3.50 (0.99) |

| 41–50 | 715 | 12.9 | 2.34 (1.04) | 2.52 (1.07) | 3.53 (1.03) | 3.41 (1.07) |

| 51–60 | 1,185 | 21.3 | 2.64 (1.08) | 2.80 (1.14) | 3.41 (1.12) | 3.30 (1.11) |

| 61–70 | 1,806 | 32.5 | 3.00 (1.02) | 3.19 (1.04) | 3.44 (1.01) | 3.35 (1.04) |

| 71 and older | 1,063 | 19.1 | 3.17 (0.97) | 3.32 (0.99) | 3.32 (1.00) | 3.25 (1.01) |

| Working status | ||||||

| In employment (full-time, part-time, self-employed) | 2,612 | 47.0 | 2.59 (1.03) | 2.76 (1.08) | 3.62 (0.96) | 3.52 (0.98) |

| Unemployed | 358 | 6.4 | 2.07 (1.13) | 2.15 (1.19) | 2.76 (1.25) | 2.64 (1.24) |

| Retired | 2,570 | 46.2 | 3.08 (1.01) | 3.24 (1.04) | 3.57 (1.02) | 3.29 (1.04) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married or living together | 5,004 | 89.9 | 2.81 (1.04) | 3.00 (1.09) | 3.51 (1.01) | 3.40 (1.03) |

| Single, widowed or separated | 536 | 9.7 | 2.67 (1.15) | 2.77 (1.15) | 3.31 (1.08) | 3.24 (1.08) |

| Overall | 5,566 | 100 | 2.77 (1.07) | 2.93 (1.11) | 3.45 (1.03) | 3.35 (1.05) |

Note: the figures do not always add up to 100% due to missing values; M = Mean; SD = Standard Deviation.

A number of socio-demographic variables were included relating to gender, age, working status and marital status. The descriptive statistics for the variables are presented in Table 1. The table shows that women are over-represented in the final sample, as are respondents over 50 years of age. Over-representation of older age groups is also reflected in the large number of respondents having retired (46.2%). Around 47% of the sample were in full-time or part-time employment, including self-employment; and 6.4% indicated being unemployed. A great majority (around 90%) were married or were living together, with 10% being single, separated or widowed.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Two sets of regression analyses were conducted for each of the two outcome variables of subjective wellbeing and self-rated health (see Table 2, Table 3 , respectively). Separate analyses were conducted for the Peak (baseline) and Post-peak (follow-up) surveys. Model 1 included perceived access to public green space and reported access to a private green space as independent variables. The different categories for the two variables were included as dummies, with ‘Public green Space (<5 min walk)’ and ‘no private garden’ as reference categories respectively. This means that three model parameters were estimated: ‘Public green space (5–10 min walk)’, ‘Public green Space (>10 min walk)’, and ‘private garden’. Model 2 extended the first model by adding interaction terms between the two independent variables, i.e. ‘Private garden × Public green space (>10 min walk)’ and ‘ Private garden × Public green space (>10 min walk)’. These regression models show whether perceived access to public green space (e.g. a park or woodland) and reported access to a private green space (a private garden) are associated with better subjective wellbeing and self-rated health. The interaction terms in Model 2 show whether having access to a private garden has a protective effect where there is a perceived lack of access to public green space. We also ran ordinal regressions for each of the individual self-rated health and subjective wellbeing items to check the robustness of our results. The results of the ordinal regression are reported in supplementary materials 1, Tables S8-S11.

Table 2.

Results from linear regression models predicting subjective wellbeing from perceived access to public green space and private garden during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Subjective wellbeing |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak |

Post-peak |

|||

| Model 1 B (95% CI) |

Model 2 B (95% CI) |

Model 1 B (95% CI) |

Model 2 B (95% CI) |

|

| Constant | 2.655 (2.553, 2.758)*** | 2.771 (2.632, 2.910)*** | 2.692 (2.586, 2.798)*** | 2.760 (2.616, 2.905)*** |

| Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.119 (−0.187, −0.052)*** | −0.324 (−0.550, −0.098)** | −0.175 (−0.245, −0.105)*** | −0.284 (−0.517, −0.050)** |

| Public green Space (>10 min walk) | −0.294 (−0.386, −0.203)*** | −0.571 (−0.833, −0.308)*** | −0.338 (−0.433, −0.244)*** | −0.518 (−0.789, −0.247)*** |

| Private garden | 0.196 (0.093, 0.299)*** | 0.072 (−0.072, 0.216) | 0.345 (0.238, 0.451)*** | 0.272 (0.123, 0.421)*** |

| Private garden × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | 0.223 (−0.014, 0.459) | 0.118 (−0.127, 0.363) | ||

| Private garden × Public green space (>10 min walk) | 0.311 (0.031, 0.591)** | 0.203 (−0.087, 0.492) | ||

| Observations | 5,498 | 5,498 | 5,504 | 5,504 |

Note: B = unstandardised regression coefficient; CI = confidence interval; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.01.

Table 3.

Results from linear regression models predicting self-rated health from perceived access to public green space and private garden during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak.

| Self-rated health |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak |

Post-peak |

|||

| Model 1 B (95% CI) |

Model 2 B (95% CI) |

Model 1 B (95% CI) |

Model 2 B (95% CI) |

|

| Constant | 3.366 (3.268, 3.464)*** | 3.427 (3.294, 3.559)*** | 3.230 (3.130, 3.329)*** | 3.252 (3.118, 3.387)*** |

| Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.195 (−0.259, −0.131)*** | −0.193 (−0.409, 0.022) | −0.196 (−0.261, −0.131)*** | −0.245 (−0.464, −0.026)** |

| Public green Space (>10 min walk) | −0.442 (−0.529, −0.355)*** | −0.756 (−1.006, −0.506)*** | −0.475 (−0.563, −0.387)*** | −0.514 (−0.768, −0.259)*** |

| Private garden | 0.203 (0.105, 0.302) *** | 0.138 (0.001, 0.275)* | 0.250 (0.150, 0.350)*** | 0.226 (0.087, 0.365)** |

| Private garden × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.005 (−0.231, 0.221) | 0.054 (−0.176, 0.283) | ||

| Private garden × Public green space (>10 min walk) | 0.361 (0.094, 0.627)** | 0.043 (−0.228, 0.314) | ||

| Observations | 5,505 | 5,505 | 5,516 | 5,516 |

Note: B = unstandardised regression coefficient; CI = confidence interval; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.01.

The third aim of the study (to examine whether certain social and demographic groups benefit more from access to public and private green spaces than others) was addressed by constructing regression models (Model 3) that included socio-demographic groups (gender, age, working status, and marital status) in addition to perceived public green space and private garden access as independent variables. Model 3 was subsequently extended by adding interactions between the respective socio-demographic groups and perceived access to public/private green space. Interactions between the socio-demographic groups on the one hand and perceived public green space and private garden access on the other were estimated in separate regression analyses (Models 4a-e). The full models are provided in supplementary materials 1 (Tables S1–S7). In all cases, the unstandardised regression coefficients and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are reported. The analyses were conducted in R statistical software (version 4.0.2) and RStudio (version 1.3.1073). All code is provided in supplementary materials 2.

3. Results

Table 1 shows that subjective wellbeing was higher in the post-peak period when lockdown restrictions were being eased than in the peak period when lockdown restrictions came into force in the UK. This difference was statistically significant (t = 13.386, df = 5530, p < 0.001), reflecting an effect size of Cohen’s d = 0.18. However, self-rated health saw a reverse effect: self-rated health was significantly lower in the post-peak period than at the outset of lockdown (t = −10.679, df = 5551, p < 0.001). The size of this effect was Cohen’s d = 0.14.

Table 2 reports the results of the regression analyses with subjective wellbeing as the dependent variable. The initial model (Model 1) shows that both perceived access to public green space and reported access to a private garden were significantly associated with subjective wellbeing during the peak and post-peak waves. People living a 5–10 min walk or more than a 10 min walk away from public green space had lower levels of subjective wellbeing than those living less than a 5 min walk away. Those with access to a private garden had higher levels of subjective wellbeing than those without a private garden. The subsequent model (Model 2) added interaction terms between perceived public green space and private garden access. Table 2 shows that the interaction between perceived private garden access and living > 10 min away from public green space was significant during the first COVID-19 peak, but not at the post-peak period. The results of ordinal regression analyses for each of the three subjective wellbeing items are reported in supplementary materials 1 (Tables S9-S11), and show only minor deviations from the results of the linear analyses, suggesting that the results are robust.

Table 3 shows the results of the regression analyses with self-rated health as the dependent variable. Similar results were found for self-rated health as for subjective wellbeing: both perceived public green space and private garden access were significantly associated with better self-rated health during and after the first COVID-19 peak in the UK (Model 1), with people living a 5–10 min walk or more than a 10 min walk away from public green space reporting poorer health than those living less than a 5 min walk away. The interaction between private garden access and living > 10 min away from public green space (Model 2) was significant during but not after the first COVID-19 peak in the UK, underlining the importance of proximal access to green space during most stringent lockdown conditions. The results of ordinal regression analyses for the self-rated health item are reported in Table S8 of supplementary materials 1. Just as for subjective wellbeing the main findings for the ordinal regressions were comparable to those of the linear regressions, suggesting that the results are robust.

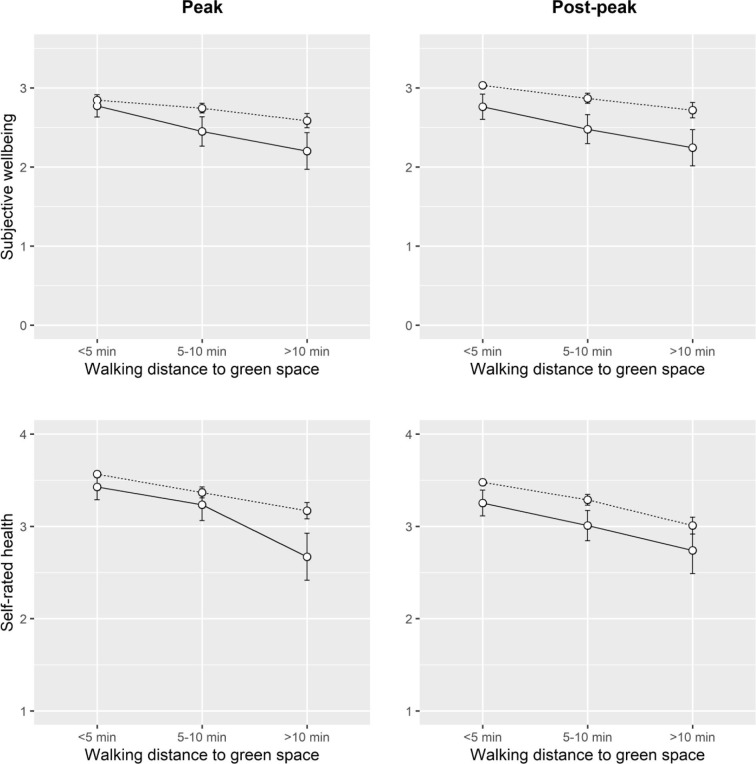

These interactions are shown in Fig. 1 . The steeper slopes in the left column of Fig. 1 illustrate that nearby public green spaces were more important for people without private gardens than for those with private gardens during the height of the first peak. The almost parallel lines in the right column of Fig. 1 show that nearby public green spaces were equally important for people with and without private gardens as lockdown was being eased.

Fig. 1.

Mean subjective wellbeing and self-rated health during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak according to walking distance to public green space for respondents with (dashed line) or without (solid line) private garden. The error bars show 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

The third aim of the study was to explore whether (perceived) public green space and private garden access benefited certain socio-demographic groups more than others. Results of the multiple regression analyses are reported in Table 4 . Model 3 results for subjective wellbeing show that men, older age groups, and those who are retired and married/living together reported better wellbeing during and after the most restrictive lockdown phase, as compared to women, younger age groups, and those who are not retired or married/living together. People who were unemployed reported lower wellbeing in both periods. The Model 3 results for self-rated health show that older age groups and those who were retired and unemployed reported poorer health during and after the most restrictive lockdown phase. Respondents who were married or living together reported better health in the two periods. There were no significant differences in self-rated health between men and women. All socio-demographic associations reported in Table 4 were consistent across the two periods, suggesting that they are more generic associations that are not due to differences in restrictions. Model 3 results further show that the subjective wellbeing effect for reported garden access was rendered non-significant by the socio-demographic covariates, but only in the period when most travel restrictions were lifted. All self-rated health effects for perceived public green space and private garden access stayed significant when controlling for socio-demographic covariates both during and after the first COVID-19 peak. This suggests that perceived public green space and private garden access contribute to subjective health and wellbeing independent of socio-demographic background of the participants, in particular during the height of the first COVID-19 outbreak.

Table 4.

Results from multiple linear regression models showing associations of subjective wellbeing and self-rated health with different socio-demographic groups and their interaction with perceived access to public green space and private garden during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak (Model 3 and Models 4a-e).

| Subjective wellbeing |

Self-rated health |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | Peak B (95% CI) |

Post-peak B (95% CI) |

Peak B (95% CI) |

Post-peak B (95% CI) |

|

| 3 | Constant | 2.623 (2.512, 2.735)*** | 2.559 (2.452, 2.667)*** | 3.401 (3.293, 3.510)*** | 3.270 (3.160, 3.380)*** |

| Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.172 (−0.237, −0.107)*** | −0.118 (−0.180, −0.055)*** | −0.169 (−0.232, −0.106)*** | −0.168 (−0.232, −0.103)*** | |

| Public green Space (>10 min walk) | −0.373 (−0.461, −0.284)*** | −0.330 (−0.416, −0.245)*** | −0.393 (−0.479, −0.308)*** | −0.428 (−0.515, −0.340)*** | |

| Private garden | 0.179 (0.077, 0.280)*** | 0.061 (−0.037, 0.159) | 0.168 (0.070, 0.267)*** | 0.225 (0.125, 0.325)*** | |

| Gender (male) | 0.311 (0.250, 0.372)*** | 0.387 (0.328, 0.447)*** | −0.010 (−0.070, 0.049). | 0.025 (−0.036, 0.085). | |

| Age | 0.175 (0.148, 0.201)*** | 0.140 (0.114, 0.166)*** | −0.051 (−0.076, −0.025)*** | −0.051 (−0.078, −0.025)*** | |

| Retired | 0.110 (0.033, 0.186)** | 0.173 (0.099, 0.247)*** | −0.108 (−0.182, −0.034)** | −0.088 (−0.163, −0.012)* | |

| Unemployed | −0.561 (−0.675, −0.446)*** | −0.486 (−0.597, −0.376)*** | −0.770 (−0.881, −0.659)*** | −0.800 (−0.913, −0.688)*** | |

| Married/Living together | 0.165 (0.104, 0.225)*** | 0.082 (0.023, 0.141)** | 0.122 (0.063, 0.181)*** | 0.075 (0.015, 0.135)* | |

| 4a | Gender × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.010 (−0.145, 0.126) | −0.008 (−0.148, 0.132) | −0.007 (−0.143, 0.129) | 0.008 (−0.131, 0.146) |

| Gender × Public green space (>10 min walk) | −0.031 (−0.218, 0.156) | −0.024 (−0.217, 0.168) | −0.104 (−0.292, 0.084) | −0.109 (−0.300, 0.082) | |

| Gender × Private garden | 0.232 (0.025, 0.440)* | 0.210 (−0.004, 0.425) | −0.013 (−0.222, 0.195) | 0.036 (−0.176, 0.247) | |

| 4b | Age × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | 0.009 (−0.034, 0.052) | 0.019 (−0.025, 0.064) | 0.002 (−0.041, 0.046) | 0.014 (−0.030, 0.058) |

| Age × Public green space (>10 min walk) | 0.043 (−0.017, 0.102) | 0.017 (−0.044, 0.079) | −0.029 (−0.089, 0.030) | −0.013 (−0.073, 0.048) | |

| Age × Private garden | 0.048 (−0.010, 0.105) | 0.043 (−0.017, 0.102) | 0.001 (−0.057, 0.058) | −0.006 (−0.065, 0.053) | |

| 4c | Retired × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.041 (−0.167, 0.085) | −0.025 (−0.155, 0.105) | 0.023 (−0.104, 0.149) | 0.045 (−0.083, 0.174) |

| Retired × Public green space (>10 min walk) | 0.065 (−0.105, 0.236) | 0.010 (−0.166, 0.187) | −0.125 (−0.296, 0.047) | −0.112 (−0.286, 0.063) | |

| Retired × Private garden | 0.158 (−0.042, 0.359) | 0.121 (−0.087, 0.328) | −0.054 (−0.255, 0.147) | −0.017 (−0.222, 0.188) | |

| 4d | Unemployed × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.027 (−0.272, 0.218) | 0.059 (−0.195, 0.313) | −0.019 (−0.265, 0.227) | −0.126 (−0.376, 0.124) |

| Unemployed × Public green space (>10 min walk) | −0.032 (−0.355, 0.291) | −0.027 (−0.362, 0.307) | −0.299 (−0.624, 0.025) | −0.281 (−0.612, 0.049) | |

| Unemployed × Private garden | 0.131 (−0.188, 0.449) | 0.077 (−0.255, 0.409) | 0.036 (−0.284, 0.357) | −0.166 (−0.492, 0.160) | |

| 4e | Married/Living together × Public green space (5–10 min walk) | −0.042 (−0.178, 0.094) | −0.050 (−0.191, 0.090) | 0.022 (−0.115, 0.159) | −0.013 (−0.152, 0.126) |

| Married/Living together × Public green space (>10 min walk) | 0.071 (−0.108, 0.250) | 0.050 (−0.135, 0.235) | 0.052 (−0.128, 0.231) | −0.028 (−0.211, 0.155) | |

| Married/Living together × Private garden | 0.027 (−0.168, 0.222) | −0.086 (−0.288, 0.115) | −0.095 (−0.291, 0.101) | −0.075 (−0.274, 0.125) | |

Note: B = unstandardised regression coefficient; CI = confidence interval; * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.01.

Table 4 further reports the results of the regression analyses that included interactions between the respective socio-demographic groups on the one hand and perceived public green space and private garden access on the other (Model 4a-e). Only one significant interaction was found for subjective wellbeing: having garden access had a bigger impact on the subjective wellbeing of men than of women. This interaction was however only found during but not after the first COVID-19 peak. There were no significant interactions for self-rated health at all. Broadly speaking, these results suggest that perceived public green space and private garden access benefited different sociodemographic groups equally in terms of subjective wellbeing and self-rated health both during and after the first COVID-19 peak. The full results of all socio-demographic regression models are provided in supplementary materials 1 (Tables S1–S7).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of results

This study investigated whether perceived access to public (e.g. a park or woodland) or private (a garden) green space was associated with better subjective health and wellbeing, both during and after the first COVID-19 peak that took place in the UK in the first half of 2020. We also examined whether there were compensatory health effects for perceived access to public and private green space, and whether (perceived) public green space and private garden access were more beneficial for specific socio-demographic groups in the two periods. The results show that both perceived access to public green space and reported access to a private garden were independently associated with better subjective wellbeing and self-rated health in both periods. In line with the health compensation hypothesis for green space, the study found that, during the height of the first COVID-19 outbreak, a private garden had a greater health protective effect where the nearest green space was perceived to be more than a 10-minute walk away. These results show that a private garden can partly compensate for a lack of access to public green space, but also that in times of crisis nearby public green spaces are particularly important for households without private garden. The study found no support that specific groups benefit more than others from public green space and private garden access. The lack of significant interactions suggests that both types of green space are an important resource for health and wellbeing irrespective of people’s socio-demographic background.

The results contribute to the literature showing that public green spaces and private gardens are beneficial for people’s health and wellbeing (Maas et al., 2006, White et al., 2017, Houlden et al., 2018, De Bell et al., 2020). As far as we are aware, this is the first analysis focusing on the role on green space in subjective health and wellbeing during the greatest public health crisis in recent history: the COVID-19 pandemic. The results are in line with other studies showing that green space can act as a buffer between negative life circumstances and experiences and health (Van den Berg et al., 2010, Roe et al., 2017, Mitchell and Popham, 2008); and suggest that the natural environment may be just as important as the social environment for community resilience and health (Poortinga, 2012, Ward-Thompson et al., 2016). The COVID-19 pandemic, which at the time of writing was still ongoing, was a stressful and traumatic period for many (e.g. Shevlin et al., 2020). It also limited social interactions and travel as a result of severe restrictions. For example, in Wales gatherings of more than two people were banned and residents had to stay within five miles of their home during lockdown. This highlights the importance of having sufficient good quality green spaces and nature nearby to maintain physical and mental health (Gray & Kellas, 2020), with urban parks and woodlands at the time being one of the few spaces that allowed for socially distanced recreation and physical activity (Venter et al., 2020, Ugolini et al., 2020).

The current study is one of the few that considered the health benefits of (perceived) access to public and private green space in conjunction. While several studies have reported the independent contributions of the two types of green space to population health (Nielsen and Hansen, 2007, Dennis and James, 2017, De Bell et al., 2020), there is no known research that has explored potential interaction effects in terms of health and wellbeing. Research on possible substitution or compensation effects has hitherto mainly focused on how public and private green spaces are used (e.g. Maat & De Vries, 2006). The combined benefits of perceived access to and/or the use of public green spaces and gardens in terms of human health and wellbeing have however been relatively unexplored. Here we show that the two types of green space counterbalance each other in terms of their effects for health and wellbeing.

The results regarding the health/wellbeing benefits of public and private green space for different socio-demographic groups were characterised by an absence of major effects. While a private garden was found to be relatively more beneficial for men than for women during the first COVID-19 peak, no other significant interactions were found. This may show that both types of green spaces provide health benefits across society. Previous research has suggested that good access to green space is relatively more important for lower income or deprived groups (e.g. Flouri et al., 2014, Mitchell et al., 2015, Xu et al., 2017), as well as for younger and older age group (Maas et al., 2006). That could however not be confirmed in the current research. The associations between urban green space and health outcomes are complex and may be confounded by socio-economic and demographic factors (Kabisch, 2019). Our study however confirmed independent associations between perceived public green space and private garden access on the one hand and subjective health and wellbeing on the other, even after controlling for the socio-demographic covariates.

5. Strengths and limitations

The study has a number of strengths and limitations. A key strength of the study is that it relies on a large-scale longitudinal dataset that was conducted in spring 2020 when the COVID-19 pandemic was emerging and wide-scale restrictions were being implemented, and in summer 2020 when the most severe restrictions were temporarily lifted. The sample was however non-representative. The sample was recruited predominantly through Health Wise Wales (HWW), a nation-wide longitudinal and dynamic cohort study (Hurt et al., 2019), supplemented by participants recruited via social media. This resulted in a dataset in which men, younger age groups, and those from deprived areas were under-represented. The study can therefore not be used to obtain population estimates. Furthermore, most respondents in our sample had access to their own garden. Although the figures were not completely out of line with national statistics (ONS, 2020), they may limit the conclusions we can draw from some of the findings, in particular those relating to the interactions of the socio-demographics with garden access. Interactions typically need many more observations than main effects to be detected (Brysbaert, 2019). Issues relating to statistical power need to be recognised across the research area on green space and health.

There are different ways in which green space can be conceptualised and measured (Houlden et al., 2018). Here we measured access to green space in terms of perceived walking distance to the nearest public green space (cf., Völker et al., 2018), using an item derived from the Scottish Household Survey (Green space Scotland, 2017, Scottish Government, 2018). This is a subjective measure that is likely to be influenced by personal characteristics. It is not clear from this measure how it relates to objectively measured distance to green space, the amount and type of green space, and the number and type of visits to these green spaces (cf., Giles-Corti et al., 2005). It is possible that respondents may have mis-interpreted what is meant by a green space as the items did not include the ‘public’ adjective. However, a list of examples was included to indicate that the question is about public spaces such as a park. The results relating to this subjective measure of green space need to be confirmed with other conceptualisations and measures of green space accessibility. That does however not mean that the current one is less valid or meaningful than more objective measures of green space access. Previous research has shown that perceived access is as important for health and wellbeing as more objective measures of green space availability within the neighbourhood. For example, Cleary et al. (2019) found that changes in perceived access to green space are associated with changes in psychological well-being over time. Furthermore, ‘nearby’ is typically interpreted as ‘within walking distance’, which is captured by our measure. The categories correspond loosely to the objective distance that is considered walkable (Ekkel & De Vries, 2017). In terms of reported garden access, the current analysis only looked only at the effects of having a private garden, not other types of outdoor spaces such as private balconies, patios or communal gardens. However, the focus on private gardens is appropriate, given that previous research has shown that private garden provide the largest contributions to health and wellbeing.

A related limitation of the research is that we do not know whether and in what way the two types of green space were used in the two studied periods and thus how the health benefits were established. Hartig et al. (2014) suggest that there are four interrelated pathways through which public green space can promote health and wellbeing, i.e., through improved air quality, enhanced physical activity, social contacts and cohesion, and stress reduction. The lockdown saw unprecedented drops in air pollution (Higham et al., 2020) and there is evidence that people made more use of green spaces during the period (Venter et al., 2020). It is however not clear whether this can explain the observed effects in subjective health and wellbeing. Similarly, the current study has no information on time spent in the private garden. De Bell et al. (2020) suggest that people who use the garden for relaxation and physical activities such as gardening report better health and higher levels of wellbeing. It is likely that these activities played a role in our reported results, but this remains speculation with no data available to confirm this. A more in-depth exploration of the way people used private outdoor spaces when the most severe restrictions were in place would be a welcome addition to the literature.

Access to private or public green space often varies across different types of environments in which people live, and there may have been residential self-selection into these different types of environments. Cross-sectional research on the built environment is particularly vulnerable to such residential selection (Boone-Heinonen et al., 2010). For example, it is possible that people with a greater need and/or preference for spending time in nature decide to live in an environment that makes that possible. Findings of previous research that people who use public parks also spend more time in their own private garden suggest that such an orientation on nature may exist. While the current study was able to control for a number socio-demographic variables, including working status, the study did not have measured or latent attributes of neighbourhood preference that would allow adjustments for residential selection. In a similar way, it was not possible to control for neighbourhood deprivation. Green space provision may be linked to neighbourhood deprivation and thus could introduce bias. It may be that those who are at greatest risk of poor mental health may have the least opportunity to benefit from easily accessible green space (Public Health England, 2020). Research from the UK suggests that accessibility of greenspaces is better in more deprived areas as compared to less deprived areas (Jones et al., 2009, Mitchell and Popham, 2008), but may be of lower quality (Mears et al., 2019) and not visited as often (Allen & Balfour, 2014). Limited attention to residential selection as a possible explanation for environmental effects is a limitation of the wider area of research on greenspace and health, with the research making very little use of longitudinal data. This makes it difficult to establish the directionality of such effects. A strength of the current paper is that it established the links between perceived access to (public and private) green space and health and wellbeing for the same people at two different time points during the pandemic.

The study used two standard measures of subjective wellbeing and self-rated health. The two measures showed different, sometimes contrasting results. For example, older age groups reported higher levels of subjective wellbeing, but poorer health as compared to younger age groups; and subjective wellbeing increased in the post-peak period, while general self-rated health decreased. However, results for (perceived) public green space and private garden access converged: both were associated with better subjective health and wellbeing, and health compensation effects were found for both measures in the peak but not post-peak period. This suggests that the benefits of green space in terms of health and wellbeing are robust. Mental wellbeing is however a multi-dimensional construct and effects may differ according to the measures used and/or aspects they are aimed to assess (Cleary et al., 2019). It could therefore be useful to consider hedonic and eudaimonic aspects of wellbeing, in addition to the evaluative health and wellbeing measures used in the current research. A recent meta-analysis (Houlden et al., 2018) concluded that there is sufficient evidence for green space providing benefits in terms of happiness and life satisfaction, but not in terms for meaning or self-realisation. The effects for the different aspects of wellbeing may also differ according to personal circumstances, life stage, and individual differences. For example, it may be that people with a greater need and/or preference for spending time in nature may experience greater benefits in terms of eudaimonic wellbeing (Cleary et al., 2017).

5.1. Conclusion

The results of this large-scale longitudinal study contribute to the evidence linking public and private green space to subjective health and wellbeing. It is the first study to assess the role of the two types of green space during and after the first peak of the COVID-19 outbreak that took place in the first half of 2020. The study shows that both perceived access to public green space and reported access to a private garden provide benefits in terms of subjective wellbeing and self-rated health. In addition, it shows that a private garden may protect against the detrimental health effects of limited access to public green space, and, in reverse, that public green space may partly compensate for the lack of a private garden. The research further suggests that the effects are uniform across society, with different groups benefiting equally from (perceived) public green space and private garden access. These findings highlight the central role of both public and private green spaces in making communities more resilient and the need for public green spaces in particular where residents do not have access to their own outdoor spaces. The results are timely, pertaining to the greatest public health crisis in recent history. They show that (perceived) access to green spaces and nature is essential for physical and mental health. Access to green space can help public deal with the challenges of a global pandemic when movement and social interaction are severely restricted. More quantitative and qualitative research is needed to show how the pandemic changed the use and perceptions of public and private green space, as well as the way in which these green spaces provided benefits to its users. Further analyses of longitudinal data in combination with the qualitative interviews that are part of COPE study are planned to explore the longer-term effects of availability of green space on health and wellbeing during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Wouter Poortinga: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Natasha Bird: Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Britt Hallingberg: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Rhiannon Phillips: Project administration, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing. Denitza Williams: Investigation, Writing - original draft, Writing - review & editing.

Acknowledgements

The study was made possible by a grant from Sêr Cymru (Welsh Government, Project No 90: COVID-19 public experiences in Wales) and facilitated by HealthWise Wales, the Heath and Care Research Wales initiative, which is led by Cardiff University in collaboration with SAIL, Swansea University.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2021.104092.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Allen J., Balfour R. UCL Institute of Health Equity; 2014. Natural solutions for tackling health inequalities. [Google Scholar]

- Badr H.S., Du H., Marshall M., Dong E., Squire M.M., Gardner L.M. Association between mobility patterns and COVID-19 transmission in the USA: a mathematical modelling study. The Lancet Infectious Diseases. 2020;20(11):1247–1254. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30553-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biedenweg K., Scott R.P., Scott T.A. How does engaging with nature relate to life satisfaction? Demonstrating the link between environment-specific social experiences and life satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2017;50:112–124. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.02.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boone-Heinonen J., Guilkey D.K., Evenson K.R., Gordon-Larsen P. Residential self-selection bias in the estimation of built environment effects on physical activity between adolescence and young adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity. 2010;7(1):70. doi: 10.1186/1479-5868-7-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brindley P., Jorgensen A., Maheswaran R. Domestic gardens and self-reported health: A national population study. International Journal of Health Geographics. 2018;17:31. doi: 10.1186/s12942-018-0148-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brysbaert M. How Many Participants Do We Have to Include in Properly Powered Experiments? A Tutorial of Power Analysis with Reference Tables. Journal of Cognition. 2019;2(1):16. doi: 10.5334/joc.72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchecker M., Degenhardt B. The effects of urban inhabitants’ nearby outdoor recreation on their wellbeing and their psychological resilience. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism. 2015;10:55–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jort.2015.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cervinka R., Schwab M., Schönbauer R., Hämmerle I., Pirgie L., Sudkamp J. My garden–my mate? Perceived restorativeness of private gardens and its predictors. Urban forestry & urban greening. 2016;16:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2016.01.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary A., Fielding K.S., Bell S.L., Murray Z., Roiko A. Exploring potential mechanisms involved in the relationship between eudaimonic wellbeing and nature connection. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2017;158:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cleary A., Roiko A., Burton N.W., Fielding K.S., Murray Z., Turrell G. Changes in perceptions of urban green space are related to changes in psychological well-being: Cross-sectional and longitudinal study of mid-aged urban residents. Health & Place. 2019;59 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colfer B. Herd-immunity across intangible borders: Public policy responses to COVID-19 in Ireland and the UK. European Policy Analysis. 2020;00:1–23. doi: 10.1002/epa2.1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtemanche C., Garuccio J., Le A., Pinkston J., Yelowitz A. Strong Social Distancing Measures In The United States Reduced The COVID-19 Growth Rate. Health Affairs. 2020;39(7):1237–1246. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucinotta, D., & Vanelli, M. (2020). WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medica: Atenei Parmensis, 91(1), 157. 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dadvand, P., Bartoll, X., Basagaña, X., Dalmau-Bueno, A., Martinez, D., Ambros, A., Cirach, M., ariguero-Mas, M., Gascon, M., Borrell, C., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2016). Green spaces and general health: roles of mental health status, social support, and physical activity. Environment International, 91, 161-167. 10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed]

- De Bell S., White M., Griffiths A., Darlow A., Taylor T., Wheeler B., Lovell R. Spending time in the garden is positively associated with health and wellbeing: Results from a national survey in England. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2020;103836 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2020.103836. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dennis M., James P. Evaluating the relative influence on population health of domestic gardens and green space along a rural-urban gradient. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2017;157:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ekkel E.D., de Vries S. Nearby green space and human health: Evaluating accessibility metrics. Landscape and Uurban Pplanning. 2017;157:214–220. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.06.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flaxman S., Mishra S., Gandy A., Unwin H.J.T., Mellan T.A., Coupland H., Monod M. Estimating the effects of non-pharmaceutical interventions on COVID-19 in Europe. Nature. 2020;584(7820):257–261. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2405-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flouri E., Midouhas E., Joshi H. The role of urban neighbourhood green space in children’s emotional and behavioural resilience. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 2014;40:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.06.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S., Merchant R.M., Lurie N. The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2020;180(6):817–818. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giles-Corti B., Broomhall M.H., Knuiman M., Collins C., Douglas K., Ng K., Donovan R.J. Increasing walking: how important is distance to, attractiveness, and size of public open space? American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2005;28(2):169–176. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray, S., & Kellas, A. (2020). Covid-19 has highlighted the inadequate, and unequal, access to high quality green spaces. The BMJ Opinion. Available from: https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2020/07/03/covid-19-has-highlighted-the-inadequate-and-unequal-access-to-high-quality-green-spaces/#:~:text=In*20the*20longer*20term*20this,allotments*20or*20communal*20green*20space (accessed 27 October 2020).

- Scotland Greenspace. Greenspace Scotland; Stirling: 2017. Greenspace Use and Attitudes Survey 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Hartig T., Mitchell R., De Vries S., Frumkin H. Nature and health. Annual Review of Public Health. 2014;35:207–228. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazer M., Formica M.K., Dieterlen S., Morley C.P. The relationship between self-reported exposure to greenspace and human stress in Baltimore, MD. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2018;169:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.08.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Higham, J. E., Ramírez, C. A., Green, M. A., & Morse, A. P. (2020). UK COVID-19 lockdown: 100 days of air pollution reduction?. Air Quality, Atmosphere & Health, 1-8. 10.1007/s11869-020-00937-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Holttum S. Research watch: Coronavirus (COVID-19), mental health and social inclusion in the UK and Ireland. Mental Health and Social Inclusion. 2020 doi: 10.1108/MHSI-05-2020-0032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Houlden V., Weich S., Porto de Albuquerque J., Jarvis S., Rees K. The relationship between greenspace and the mental wellbeing of adults: A systematic review. PloS ONE. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0203000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt L., Ashfield-Watt P., Townson J., Heslop L., Copeland L., Atkinson M.D., Horton J., Paranjothy S. Cohort profile: HealthWise Wales. A research register and population health data platform with linkage to National Health Service data sets in Wales. BMJ Open. 2019;9(12) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-031705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E.L., Benyamini Y. Self-rated health and mortality: a review of twenty-seven community studies. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;21–37 doi: 10.2307/2955359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A., Hillsdon M., Coombes E. Greenspace access, use, and physical activity: Understanding the effects of area deprivation. Preventive Medicine. 2009;49(6):500–505. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabisch N. (2019) The Influence of Socio-economic and Socio-demographic Factors in the Association Between Urban Green Space and Health. In: Marselle M., Stadler J., Korn H., Irvine K., Bonn A. (eds) Biodiversity and Health in the Face of Climate Change. Cham: Springer. 10.1007/978-3-030-02318-8_5.

- Karatzias T., Shevlin M., Murphy J., McBride O., Ben-Ezra M., Bentall R.P., Vallières F., Hyland P. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and associated comorbidity during the COVID-19 pandemic in Ireland: A population-based study. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2020;33(4):365–370. doi: 10.1002/jts.22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L.Z., Wang S. Prevalence and predictors of general psychiatric disorders and loneliness during COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. Psychiatry Research. 2020;291 doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao M.L., Ou S.J., Heng Hsieh C., Li Z., Ko C.C. Effects of garden visits on people with dementia: A pilot study. Dementia. 2020;19(4):1009–1028. doi: 10.1177/1471301218793319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B.B., Fuller R.A., Bush R., Gaston K.J., Shanahan D.F. Opportunity or orientation? Who uses urban parks and why. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(1) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas J., Verheij R.A., Groenewegen P.P., De Vries S., Spreeuwenberg P. Green space, urbanity, and health: how strong is the relation? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2006;60(7):587–592. doi: 10.1136/jech.2005.043125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maat K., de Vries P. The influence of the residential environment on greenspace travel: Testing the compensation hypothesis. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space. 2006;38(11):2111–2127. doi: 10.1068/a37448. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mears M., Brindley P., Maheswaran R., Jorgensen A. Understanding the socioeconomic equity of publicly accessible greenspace distribution: The example of Sheffield, UK. Geoforum. 2019;103:126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.04.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R.J., Richardson E.A., Shortt N.K., Pearce J.R. Neighborhood environments and socioeconomic inequalities in mental well-being. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2015;49(1):80–84. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R., Popham F. Greenspace, urbanity and health: relationships in England. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2007;61(8):681–683. doi: 10.1136/jech.2006.053553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell R., Popham F. Effect of exposure to natural environment on health inequalities: an observational population study. The Lancet. 2008;372(9650):1655–1660. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61689-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen T.S., Hansen K.B. Do green areas affect health? Results from a Danish survey on the use of green areas and health indicators. Health & Place. 2007;13(4):839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- ONS . Office for National Statistics. 2020. One in eight British households has no garden. (accessed 23 February 2021) [Google Scholar]

- Ottosson J., Grahn P. The role of natural settings in crisis rehabilitation: how does the level of crisis influence the response to experiences of nature with regard to measures of rehabilitation? Landscape Research. 2008;33(1):51–70. doi: 10.1080/01426390701773813. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paez A. Using Google Community Mobility Reports to investigate the incidence of COVID-19 in the United States. Findings. 2020 doi: 10.32866/001c.12976. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Paez, A., Lopez, F. A., Menezes, T., Cavalcanti, R., & Pitta, M. G. da R. (2021). A Spatio-Temporal Analysis of the Environmental Correlates of COVID-19 Incidence in Spain. Geographical Analysis. 10.1111/gean.12241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pappa S., Ntella V., Giannakas T., Giannakoulis V.G., Papoutsi E., Katsaounou P. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passmore H.A., Howell A.J. Nature involvement increases hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing: A two-week experimental study. Ecopsychology. 2014;6(3):148–154. doi: 10.1089/eco.2014.0023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poortinga W. Community resilience and health: The role of bonding, bridging, and linking aspects of social capital. Health & Place. 2012;18(2):286–295. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pritchard A., Richardson M., Sheffield D., McEwan K. The relationship between nature connectedness and eudaimonic well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies. 2020;21(3):1145–1167. doi: 10.1007/s10902-019-00118-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health England. (2020). Improving access to greenspace. A new review for 2020. Public Health England.

- Roe, J. J., Aspinall, P. A., & Ward Thompson, C. (2017). Coping with stress in deprived urban neighborhoods: what is the role of green space according to life stage?. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1760. 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Scottish Government (2018) Scotland’s People Annual Report 2017. Edinburgh: Scottish Government. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/binaries/content/documents/govscot/publications/statistics/2018/09/scotlands-people-annual-report-results-2017-scottish-household-survey/documents/scotlands-people-annual-report-2017/scotlands-people-annual-report-2017/govscot*3Adocument/00539979.pdf?forceDownload=true (accessed 13 October 2020).

- Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J., Miller, J. G., Hartman, T. K., Levita, L., ... & Bennett, K. M. (2020). Anxiety, Depression, Traumatic Stress, and COVID-19 Related Anxiety in the UK General Population During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Psyarxiv. Available from: https://psyarxiv.com/hb6nq/download/?format=pdf (accessed 27 October 2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Stigsdotter U.A., Grahn P. A garden at your workplace may reduce stress. Design & Health. 2004:147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Strandell A., Hall C.M. Impact of the residential environment on second home use in Finland-Testing the compensation hypothesi. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2015;133:12–23. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2014.09.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sugiyama T., Leslie E., Giles-Corti B., Owen N. Associations of neighbourhood greenness with physical and mental health: do walking, social coherence and local social interaction explain the relationships? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2008;62(5) doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.064287. e9 e9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson C.W., Roe J., Aspinall P., Mitchell R., Clow A., Miller D. More green space is linked to less stress in deprived communities: Evidence from salivary cortisol patterns. Landscape and Urban Planning. 2012;105(3):221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2011.12.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toftager M., Ekholm O., Schipperijn J., Stigsdotter U., Bentsen P., Grønbæk M., Kamper-Jørgensen F. Distance to green space and physical activity: a Danish national representative survey. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 2011;8(6):741–749. doi: 10.1123/jpah.8.6.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Triguero-Mas M., Dadvand P., Cirach M., Martínez D., Medina A., Mompart A., Nieuwenhuijsen M.J. Natural outdoor environments and mental and physical health: relationships and mechanisms. Environment international. 2015;77:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twohig-Bennett C., Jones A. The health benefits of the great outdoors: A systematic review and meta-analysis of greenspace exposure and health outcomes. Environmental research. 2018;166:628–637. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2018.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ugolini F., Massetti L., Calaza-Martínez P., Cariñanos P., Dobbs C., Ostoic S.K., Simoneti M. Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on the use and perceptions of urban green space: an international exploratory study. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2020;56 doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2020.126888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Berg A.E., Maas J., Verheij R.A., Groenewegen P.P. Green space as a buffer between stressful life events and health. Social Science & Medicine. 2010;70(8):1203–1210. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venter Z., Barton D., Gundersen V., Figari H., Nowell M. Urban nature in a time of crisis: recreational use of green space increases during the COVID-19 outbreak in Oslo. Norway. Environmental Research Letters. 2020;15(10) doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/abb396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Völker S., Heiler A., Pollmann T., Claßen T., Hornberg C., Kistemann T. Do perceived walking distance to and use of urban blue spaces affect self-reported physical and mental health? Urban Forestry & Urban Greening. 2018;29:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ufug.2017.10.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ward-Thompson C., Aspinall P., Roe J., Robertson L., Miller D. Mitigating stress and supporting health in deprived urban communities: the importance of green space and the social environment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2016;13(4):440. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13040440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells N.M., Evans G.W. Nearby nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children. Environment & Behavior. 2003;35(3):311–330. doi: 10.1177/0013916503035003001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White M.P., Pahl S., Wheeler B.W., Depledge M.H., Fleming L.E. Natural environments and subjective wellbeing: Different types of exposure are associated with different aspects of wellbeing. Health & Place. 2017;45:77–84. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2017.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2020). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak. Geneva: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331490/WHO-2019-nCoV-MentalHealth-2020.1-eng.pdf (accessed 01 December 2020).

- Xu L., Ren C., Yuan C., Nichol J.E., Goggins W.B. An ecological study of the association between area-level green space and adult mortality in Hong Kong. Climate. 2017;5(3):55. doi: 10.3390/cli5030055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang T., Barnett R., Fan Y., Li L. The effect of urban green space on uncertainty stress and life stress: a nationwide study of university students in China. Health & Place. 2019;59 doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2019.102199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Žlender V., Thompson C.W. Accessibility and use of peri-urban green space for inner-city dwellers: A comparative study. Landscape and urban planning. 2017;165:193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.06.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zuniga-Teran A.A., Stoker P., Gimblett R.H., Orr B.J., Marsh S.E., Guertin D.P., Chalfoun N.V. Exploring the influence of neighborhood walkability on the frequency of use of greenspace. Landscape and urban planning. 2019;190 doi: 10.1016/j.landurbplan.2019.103609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.