Abstract

Background and Objectives

Diet may be a key contributor to brain health in midlife. In particular, omega-3 fatty acids have been related to better neurologic outcomes in older adults. However, studies focusing on midlife are lacking. We investigated the cross-sectional association of red blood cell (RBC) omega-3 fatty acid concentrations with MRI and cognitive markers of brain aging in a community-based sample of predominantly middle-aged adults and further explore effect modification by APOE genotype.

Methods

We included participants from the Third-Generation and Omni 2 cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study attending their second examination. Docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) concentrations were measured from RBC using gas chromatography, and the Omega-3 index was calculated as EPA + DHA. We used linear regression models to relate omega-3 fatty acid concentrations to brain MRI measures (i.e., total brain, total gray matter, hippocampal, and white matter hyperintensity volumes) and cognitive function (i.e., episodic memory, processing speed, executive function, and abstract reasoning) adjusting for potential confounders. We further tested for interactions between omega-3 fatty acid levels and APOE genotype (e4 carrier vs noncarrier) on MRI and cognitive outcomes.

Results

We included 2,183 dementia-free and stroke-free participants (mean age of 46 years, 53% women, 22% APOE-e4 carriers). In multivariable models, higher Omega-3 index was associated with larger hippocampal volumes (standard deviation unit beta ±standard error; 0.003 ± 0.001, p = 0.013) and better abstract reasoning (0.17 ± 0.07, p = 0.013). Similar results were obtained for DHA or EPA concentrations individually. Stratification by APOE-e4 status showed associations between higher DHA concentrations or Omega-3 index and larger hippocampal volumes in APOE-e4 noncarriers, whereas higher EPA concentrations were related to better abstract reasoning in APOE-e4 carriers. Finally, higher levels of all omega-3 predictors were related to lower white matter hyperintensity burden but only in APOE-e4 carriers.

Discussion

Our results, albeit exploratory, suggest that higher omega-3 fatty acid concentrations are related to better brain structure and cognitive function in a predominantly middle-aged cohort free of clinical dementia. These associations differed by APOE genotype, suggesting potentially different metabolic patterns by APOE status. Additional studies in middle-aged populations are warranted to confirm these findings.

Diet is a key modifiable risk factor contributing to brain health.1 In particular, several epidemiologic studies have linked higher omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) assessed in blood or diet to larger volumes of total brain,2 the hippocampus,3 and gray matter4; reduced amygdala volume over time5; lower prevalence of subclinical infarcts and white matter burden6; better cognitive function2,7; and reduced risk of dementia and Alzheimer disease.8,9 However, these studies have been conducted predominantly in older adults (mean age ranging from 67 to 84 years).

Despite the largely beneficial brain outcome associations observed in population-based studies, the results from dietary interventions using omega-3 PUFA supplementation do not provide clear evidence for improvements in cognitive function in individuals with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer disease dementia.10,11 These studies may be hampered in part by interventions that are deemed too late in the course of the disease, when individuals may have already experienced significant neuronal damage.12

Another important consideration when studying the impact of fatty acids on brain health is the role of ApoE. ApoE is involved in the transport and metabolism of lipids,13 and experimental models suggest that APOE genotype moderates the transport of omega-3 PUFA to the brain.14 This is in line with several population studies suggesting differential effects by APOE status in the association between omega-3 PUFA and neurologic outcomes.15,16 Furthermore, the e4 allele in the APOE gene is the strongest genetic risk factor for late onset Alzheimer disease.17

Few studies have characterized associations between omega-3 PUFA levels and the earliest markers of abnormal brain aging in midlife, when neuropathologic changes related to dementia are believed to begin. Therefore, we aimed to explore the association of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in red blood cells (RBCs) and their combination in the Omega-3 index, with structural brain MRI measures and cognitive function in a predominantly middle-aged sample from the community (mean age of 46 years). We further assess effect modification by APOE genotype.

Methods

Study Population

This report includes participants from the Third-generation and Omni 2 cohorts of the Framingham Heart Study attending their second examination.18 In brief, this is a community-based, multigenerational, longitudinal cohort study designed to investigate the determinants of cardiovascular disease. This study began in 1948, enrolling 5,209 residents of the town of Framingham, MA (Original cohort). Later, in 1975, 5,124 children of the Original cohort were enrolled (Offspring cohort).19 The Third-Generation cohort started in 2002 and includes 4,095 children of the Offspring and grandchildren of the Original cohort. To reflect the changing demographics of the population in Framingham, this study enrolled 2 unrelated non-White cohorts in 1994 (n = 506, Omni 1 cohort) and 2002 (n = 410, Omni 2 cohort), paralleling the examination cycles of the Offspring and Third-generation cohorts, respectively. The Third-generation and Omni 2 participants are invited to undergo examinations every 4–6 years and remain under surveillance for incident disease.

In this investigation, we include participants who provided blood samples for the assessment of fatty acids, and underwent brain MRI and neuropsychological evaluations. In analyses focused on MRI outcomes, we excluded participants with large brain infarcts (n = 18) and with prevalent stroke or neuroimaging findings that could interfere with the reading of scans (i.e., tumors, Multiple Sclerosis; n = 45).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

The study protocols and consent forms were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Boston University Medical Center. All participants provided written informed consent at each examination.

Fatty Acids and Covariates

Fatty acid composition was measured from RBC aliquots obtained during the second examination (2008–2011) following standard procedures.20 After transesterification with boron trifluoride, fatty acids were analyzed by gas chromatography using a GC2010 Gas Chromatograph (Shimadzu Corporation, Columbia, MD) equipped with an SP2560, 100-m column (Supelco, Bellefonte, PA). Individual fatty acids were identified through comparison with a standard mixture characteristic of RBC and are expressed as the percentage of the total pool of fatty acids. In this report, we focused on the long-chain omega-3 PUFA EPA and DHA, as well as the Omega-3 index, calculated as the sum of EPA and DHA.21 The interassay coefficient of variation was <4% for both EPA and DHA.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as the weight divided by the square of height (kg/m2). Type 2 diabetes was considered present when participants had fasting glucose levels of ≥126 mg/dL or they reported the use of antidiabetic medications. Smoking status was defined as current smoker or nonsmoker. Prevalent cardiovascular disease included the presence of coronary heart disease, heart failure, or peripheral arterial disease. APOE genotype was determined with a standard TaqMan assay; APOE-e4 carriers were defined as those having at least 1 e4 allele. Prevalent depression was defined based on a Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) score ≥16 and/or use of antidepressants (Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System code N06A).

MRI Markers

Participants underwent brain MRI examination on a 1.5T scanner from Siemens (Munich, Germany). We used 3D T1-weighted coronal spoiled gradient-recalled echo and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequences. The segmentation of gray and white matter volumes was based on an Expectation-Maximization algorithm that iteratively refines its segmentation estimates to produce outputs that are most consistent with the input intensities from the native space T1 images along with a model of image smoothness. The segmentation was refined using a Markov Random Field model and adaptive priors model.22 Hippocampal volume was computed using a semiautomated algorithm incorporating a multiatlas hippocampal segmentation.23 The segmentation and quantification of white matter hyperintensities (WMH) were performed on a combination of FLAIR and 3D T1 images using a modified Bayesian probability structure based on a previously published method of histogram fitting.24 Total intracranial volume was derived from 3D T1 after removal of nonbrain tissues. The skull was removed using an atlas-based method23 followed by quality control.

Neuropsychological Assessment

A detailed neuropsychological battery was administered by trained Framingham investigators at the time of or close to brain MRI. In this study, we considered tests assessing delayed episodic memory (Logical Memory–delayed), processing speed (Trail Making Test Part A, TMT-A), executive function (Trail Making Test Part B- Part A, TMT B-A), and abstract reasoning (Similarities). For ease of interpretation, Trail Making Test scores were inversed such that higher values indicate a faster time of completion, similar to other cognitive tasks. We also considered the Wide Range Achievement Test (WRAT) for adjustment in our regression models because WRAT test scores have been reported to better assess years of education when assessing premorbid cognitive function,25 especially among diverse participants.26,27

Statistical Analysis

We log-transformed EPA, DHA, Omega-3 index levels, BMI, WMH volumes, and test scores for TMT-A, TMT B-A, and WRAT to normalize their skewed distributions. Omega-3 PUFA levels were modeled continuously per increase in standard deviation units (SDUs) and dichotomized by the bottom quartile categories as a strategy to assess threshold effects, using the bottom quartile as the reference group. Brain volumes were regressed onto total intracranial volume to correct for differences in head size, and the residuals were used as outcome measures. We used linear regression models to separately relate each omega-3 PUFA concentrations (independent variables) to MRI measures or cognitive outcomes. Our primary models were adjusted for sex, age, age2 (MRI outcomes), cohort, the time between blood draw and either neuroimaging or cognitive evaluation, and WRAT scores (cognitive outcomes). A second model additionally adjusted for vascular risk factors including systolic blood pressure, antihypertensive medication, smoking, diabetes, total cholesterol to HDL ratio, BMI, lipid-lowering medication use, and prevalent cardiovascular disease. In secondary analyses, we tested for statistical interactions between omega-3 PUFA levels and APOE genotype (APOE-e4 carriers vs noncarriers) when evaluating the associations with MRI and cognitive outcomes. Interactions were considered statistically significant at p values of ≤0.1. A final exploratory analysis was performed to assess potential mediation of MRI measures in the associations between omega-3 PUFA and cognition. Owing to the exploratory nature of this work, associations were considered statistically significant at standard p values of <0.05. All analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Data Availability

Deidentified data are available through formal data request application procedures by qualified investigators. More information is presented in framinghamheartstudy.org or biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/framcohort/.

Results

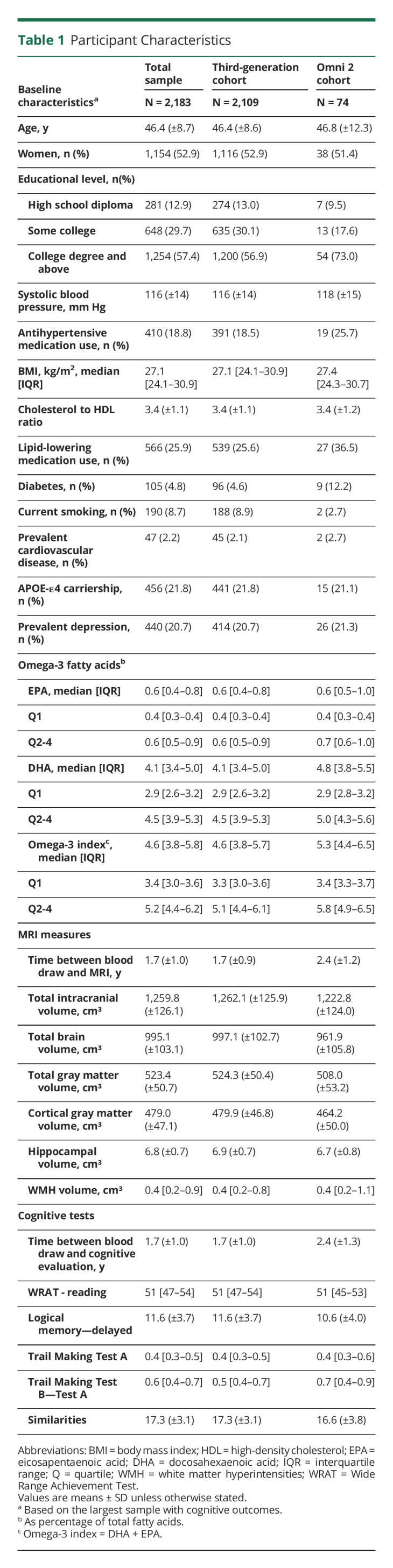

Table 1 presents the baseline characteristics for the whole sample and by cohort. Overall, the mean age of participants was 46 years (ranging from 24 to 83 years), 53% were women, 57% had a college degree or above, and 22% had at least 1 copy of the APOE-e4 allele. Compared with the Third-Generation cohort, a higher proportion of Omni 2 participants had diabetes and used antihypertensive and lipid-lowering medications; a lower proportion were current smokers. The median for RBC omega-3 PUFA levels was 4.6% (interquartile range 3.8–5.8), consistent with cohorts of similar age,28 but slightly lower than older cohorts.2,3

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

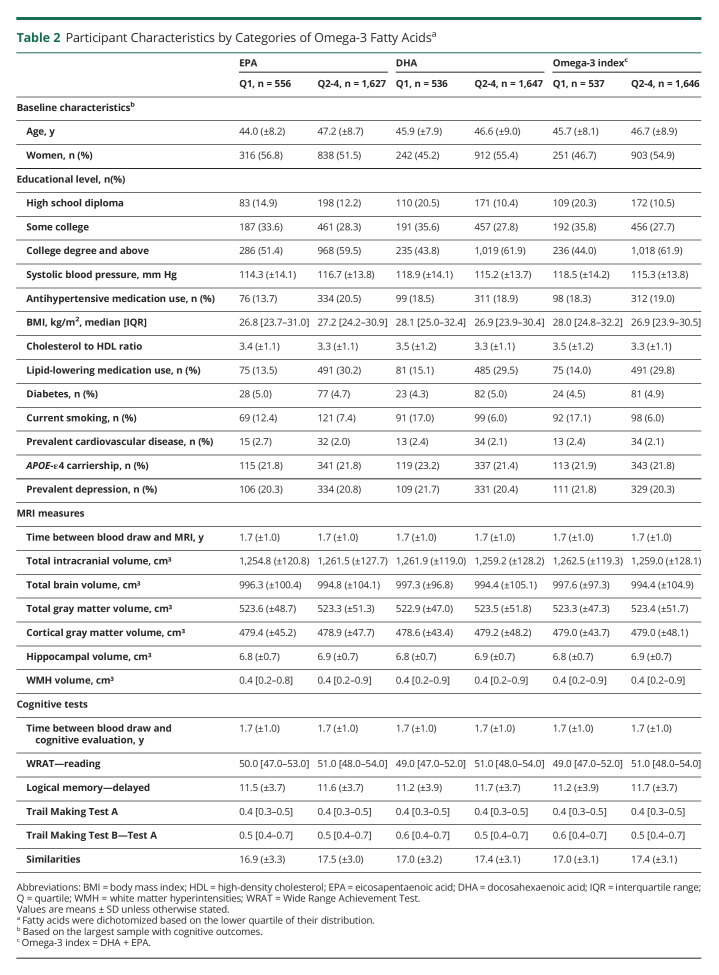

Table 2 presents the baseline characteristics and neurologic outcomes by omega-3 PUFA categories. In contrast to the upper 3 quartiles, participants within the bottom quartile of the distribution of EPA and DHA tended to be younger, have a lower educational level and lower WRAT scores, use less lipid-lowering medications, and be current smokers. Those in the lowest category of EPA concentrations also used less antihypertensive medications and had a lower BMI compared with those with higher levels. Those in the lowest category of DHA concentrations tended to have a higher BMI compared with those within higher levels.

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics by Categories of Omega-3 Fatty Acidsa

Associations With MRI Measures

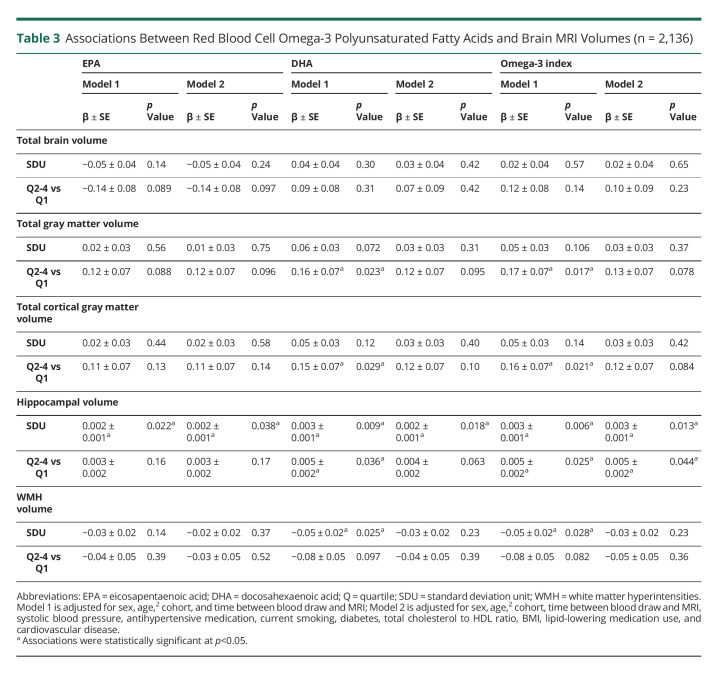

Higher levels of EPA, DHA, and the Omega-3 index were associated with larger hippocampal volumes when modeled continuously. For instance, every SDU increase of log-transformed Omega-3 index was related to 0.003 cm3 larger hippocampal volumes relative to intracranial volume (both models). We also observed a threshold effect for DHA levels and the Omega-3 index, where participants in the top 3 quartile levels had larger hippocampal volumes compared with those in the bottom quartile. Furthermore, participants with DHA levels and the Omega-3 index in the 3 upper quartiles had larger total gray and cortical gray matter volumes, as compared with participants in the bottom quartile. Finally, we found an association of higher DHA levels and Omega-3 index with lower WMH volumes. The associations between higher omega-3 PUFA and larger hippocampal volumes remained significant after adjustment for vascular risk factors, whereas those for total gray matter, cortical gray matter, and WMH volumes were attenuated (Table 3).

Table 3.

Associations Between Red Blood Cell Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Brain MRI Volumes (n = 2,136)

Associations With Cognitive Function

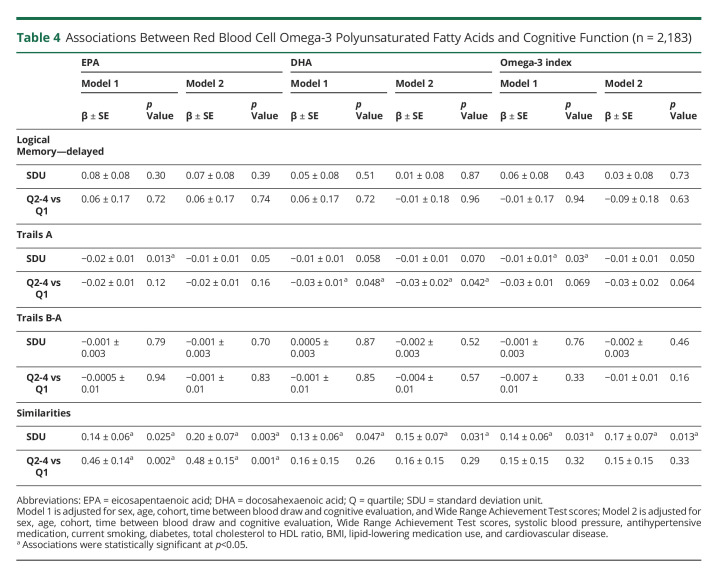

Higher levels of all omega-3 predictors (EPA, DHA, and the Omega-3 index), when modeled continuously, were associated with better performance in the Similarities test (Table 4). In addition, being in the top 3 quartiles of EPA levels was also associated with better performance in the Similarities test, as compared with participants in the bottom quartile of EPA. These associations remained after additional adjustment for vascular risk factors. Finally, we also observed that higher levels of the 3 omega-3 PUFA predictors were related to decreased processing speed, although associations were attenuated in fully adjusted models, except for DHA. Mediation analyses indicated the association between the Omega-3 index (SDU) and abstract reasoning was not mediated by hippocampal volume (natural indirect effect = 0.001, p = 0.795). Only 1.1% was mediated by hippocampal volume when considering the total effect.

Table 4.

Associations Between Red Blood Cell Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Cognitive Function (n = 2,183)

Interactions With APOE Status

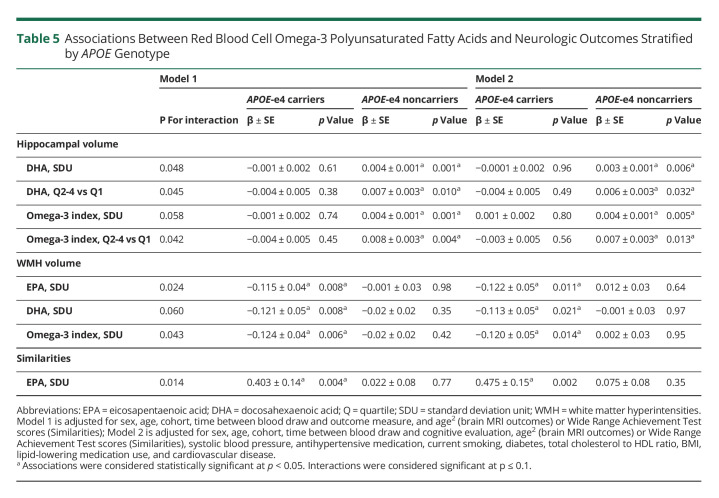

We found statistical interactions for DHA levels and the Omega-3 index with APOE genotype in relation to hippocampal volumes (Table 5). Only in APOE-e4 noncarriers, higher DHA levels and the Omega-3 index were related to larger hippocampal volumes. These associations were observed when omega-3 levels were modeled continuously and further doubled effect sizes when comparing participants within the top 3 vs the bottom quartile levels, suggesting threshold effects. In addition, the associations for all 3 omega-3 predictors with WMH burden (modeled continuously) were modified by APOE genotype status. Higher levels of EPA, DHA, and the Omega-3 index were associated with reduced WMH burden in APOE-e4 carriers. Finally, we found a statistical interaction between EPA and APOE for abstract reasoning, where increasing EPA levels were associated with better performance in the Similarities test in APOE-e4 carriers but not in noncarriers. All associations remained after additional adjustment for vascular risk factors.

Table 5.

Associations Between Red Blood Cell Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids and Neurologic Outcomes Stratified by APOE Genotype

Discussion

Our exploratory study suggests that higher RBC omega-3 PUFA levels, including EPA, DHA, and the Omega-3 index, are associated with larger hippocampal volumes and better abstract reasoning as early as midlife, independent of vascular risk factors. We also observed threshold effects for the association between the Omega-3 index and hippocampal volume and between EPA levels and abstract reasoning, suggesting only moderate consumption of omega-3 PUFA may be enough to preserve brain structure and function.

The synthesis of DHA and EPA de novo is inefficient in humans; therefore, these omega-3 PUFAs are largely obtained from dietary sources such as cold-water oily fish, omega-3 fortified foods, or in the form of nutritional supplements.29 The transport of fatty acids into the brain can take place through simple diffusion from the bloodstream30 or with the help of specialized proteins such as the fatty acid translocase CD36, the major facilitator superfamily domain-containing protein 2A (MFSD2A), fatty acid-binding proteins, and fatty acid transport proteins.31 In the brain, DHA is incorporated into neuronal and glial cell membranes, particularly in gray matter and synapses. Both DHA and EPA are metabolized into bioactive molecules involved in neurogenesis, neurotransmission, and inflammation resolution.32

Previous research has demonstrated that higher omega-3 fatty acid levels are associated with better brain measures in older individuals, but studies in middle-aged adults are scarce. Our results are in line with previous observations in the Framingham Offspring cohort.2 In this older sample (mean age of 67 years), we observed that participants in the bottom quartile of DHA and omega-3 levels had lower total brain volumes as compared with those in the upper 3 quartiles.2 There was also a linear association for higher levels of DHA and omega-3 with better abstract reasoning. Similarly, the Women's Health Initiative Memory Study (WHIMS) reported associations between higher Omega-3 index levels and larger total brain and hippocampal volumes in postmenopausal women (mean age of 70 years).3 A subsequent study in WHIMS also reported that omega-3 PUFA attenuated the harmful association between exposure to ambient air pollution and lower white matter volumes.33 Furthermore, a substudy of the Pittsburgh Adult Health and Behavior project reported that serum phospholipid DHA levels were associated with better performance in nonverbal abstract reasoning and working memory in young adults (mean age of 44 years).34 Finally, an analysis of circulating metabolites using proton nuclear magnetic resonance or mass spectrometry reported that higher DHA concentrations were related to better cognitive function and reduced risk of all-cause dementia and Alzheimer disease in 11 population-based cohorts (mean age ranging from 40 to 74 years).35

Studies in animal models suggest that omega-3 PUFA may act through multiple pathways to improve hippocampal function, plasticity, and reduce inflammation. DHA and EPA deficiency in mature mice leads to downregulation of the presynaptic vesicle proteins and glutamate receptor subunits in hippocampal synapses.36 Furthermore, in aged mice fed with an enriched diet on omega-3 PUFA during 8 weeks, larger hippocampal volumes were observed accompanied with both increased neuronal density, microglial phagocytic activity on neuronal debris, hippocampal neurogenesis, cell differentiation, as well as reduced apoptosis of hippocampal cells, and astrocytosis.37

Despite the beneficial associations observed for brain outcomes in population-based and experimental studies, the results from dietary intervention studies using omega-3 PUFA supplementation have been inconsistent. Whereas some do not show improvements in cognitive function in individuals with cognitive complaints or Alzheimer disease (mean age ranging from 55 to 78 years),10,38,39 other trials have reported a slower cognitive decline in a subgroup of older adults (mean age of 74 years) with mild dementia,40 or improved executive function, white matter microstructure, and gray matter volumes in cognitively normal older adults (mean age of 63 years).41 Additional interventions combining omega-3 PUFA with other nutrients or behavioral changes have shown slower cognitive decline and preservation of gray matter and hippocampal volumes in older adults (mean age of 70 years) with prodromal Alzheimer's disease or mild cognitive impairment.42,43

Thus, one of the main challenges for some of these studies may be that dietary interventions are performed perhaps too late for significant improvements in symptomatic participants because cognitive changes may be well established over the previous 15–20 years. Epidemiologic and intervention studies suggest that omega-3 PUFA may be most beneficial to preserve brain health from early midlife, as our study suggests, and just before the onset of moderate cognitive changes. Other potential sources of heterogeneity between observational and intervention studies are the quality and quantity of omega-3 PUFA dietary supplements44 and the duration of interventions as evidenced by the LipiDiDiet trial.42 Finally, an increasing number of studies suggest differential responses by APOE genotype,15 which are not always considered.

Intriguingly, stratification by APOE status in our study suggested distinct potentially protective associations of omega-3 PUFA with gray and white matter. On one hand, we observed that elevated DHA levels and Omega-3 index were related to larger hippocampal volumes only in APOE-e4 noncarriers. On the other hand, higher levels of all omega-3 PUFA markers were related to lower WMH burden and higher EPA levels were related to better abstract reasoning, both of these associations only among APOE-e4 carriers.

Compared with APOE non-e4 carriers, accelerated hippocampal loss and increased blood-brain barrier breakdown in the hippocampus and medial temporal lobe have been reported in APOE-e4 carriers in normal aging and Alzheimer disease.45-47 Further in the context of omega-3 PUFA, secondary analyses from an intervention trial in patients with mild Alzheimer disease found that an 18-month DHA supplementation was related to increased EPA and DHA in plasma and CSF among APOE-e4 noncarriers compared with e4 carriers,48,49 suggesting different fatty acid metabolic patterns by APOE genotype. This trial also reported an association between increased EPA to arachidonic acid levels and a slower decline of right hippocampal volumes in the treatment arm, also in APOE-e4 noncarriers only.49

Our findings relating omega-3 PUFA to better abstract reasoning, particularly in e4 carriers, are in line with results from population-based studies showing higher seafood intake was related to reduced cognitive decline in the Rush Memory and Aging Project,50 and results from the 3-City Study describing higher plasma DHA and EPA levels were associated with slower declines on visual memory,e1 both among APOE-e4 carriers. Furthermore, 2 intervention studies in older adults receiving DHA and EPA supplementation showed improvements in reasoninge2 and attentione3 only among APOE-e4 carriers compared with placebo. However, other studies report no interaction between APOE genotype and fish consumption on global cognition or episodic memory.e4

The associations of higher omega-3 PUFA with lower brain WMH require further research. The Multidomain Alzheimer Preventive Trial reported no associations between RBC omega-3 PUFA and WMH,e2 although this study was performed in older adults and considered APOE as a covariate instead of as an effect modifier. It has been suggested that APOE-e4 carriers have different patterns of brain activity at younger ages,e5 including larger white matter volumes, better white matter integrity on diffusion tensor imaging, and better attention.e6,e7 Alternatively, the beneficial effects of omega-3 PUFA on brain white matter may occur through other pathways related to reductions of vascular risk factors that may contribute to cerebral small vessel disease.e1

The strengths of our study are the inclusion of a large sample of middle-aged individuals from the community, with comprehensive assessments of neuroimaging markers and cognitive function as well as the collection of multiple health measures that can be included as potential confounders in our models. Furthermore, we use objective measurements of DHA and EPA from RBC, which more accurately reflect the dietary intake of foods containing omega-3 PUFA over the past 3 months and are more stable than those measured from plasma.e8-e9 However, our study has several limitations. Although we included a multiethnic sample, a large proportion of participants are White, which may limit the generalizability of results to other ethnic groups. Furthermore, this is a cross-sectional study, and therefore, we are not able to establish causality or assess the impact of omega-3 PUFA on changes in brain structure and function in this age group. Moreover, we cannot exclude the possibility of additional unmeasured confounding not accounted for in our analyses, such as indicators of healthier behaviors related both to intake of omega-3 rich foods and brain health. For instance, higher education or socioeconomic status have been related to omega-3 PUFA (intake and supplementation)e10 or brain volumes.e11 However, additional adjustment for education, as a proxy for socioeconomic position, led to virtually unchanged results in this study (data not shown). Finally, given the exploratory nature of our investigation, we did not account for multiple testing; therefore, our results should be considered as hypothesis generating.

In conclusion, this exploratory study suggests that higher RBC omega-3 PUFA levels are associated with larger hippocampal volumes and better performance in abstract reasoning, even in cognitively healthy middle-aged adults from the community, suggesting a possible role in improving cognitive resilience. Further exploration indicated that APOE modulates the associations of omega-3 with brain structure and function. Additional studies are needed to confirm these findings in young adults, particularly addressing the possible modulator role of APOE.

Acknowledgment

We thank Framingham Study participants for their dedication and contributions to this study and Framingham Study investigators and staff, especially the Neurology team, for their contributions to data collection.

Glossary

- APOE

apolipoprotein E

- BMI

body mass index

- CES-D

Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale

- DHA

docosahexaenoic acid

- EPA

eicosapentaenoic acid

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- PUFA

polyunsaturated fatty acid

- RBC

red blood cell

- SDU

standard deviation units

- WMH

white matter hyperintensities

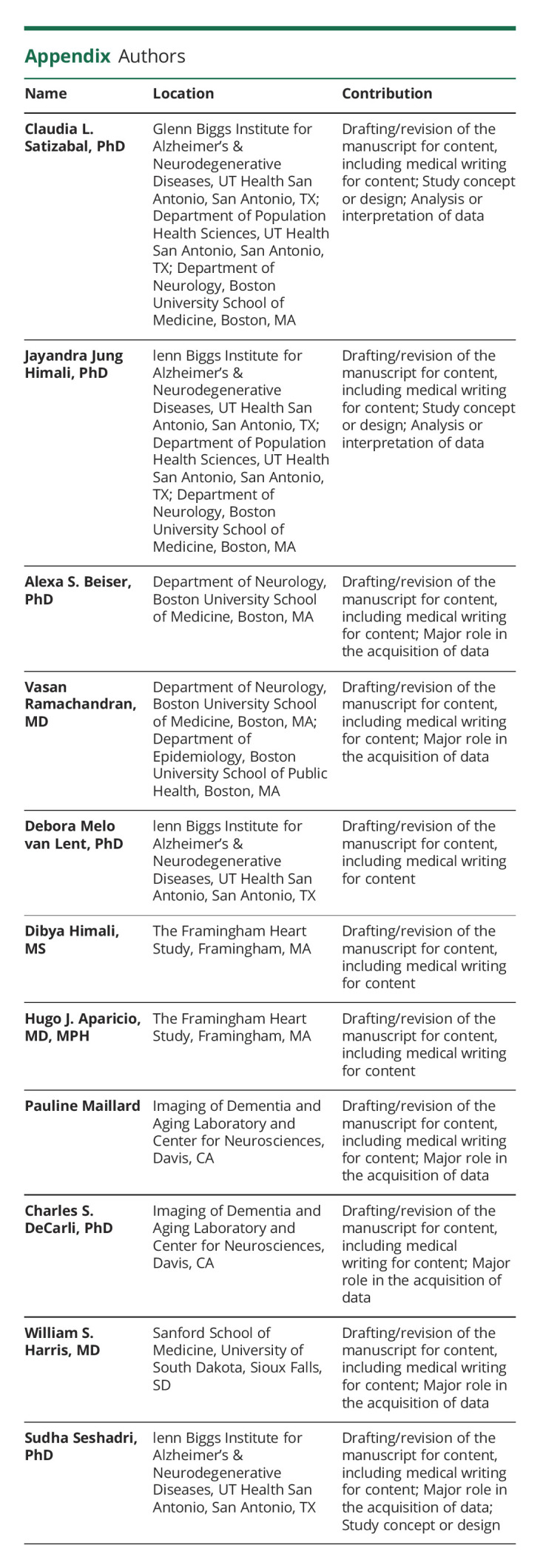

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

This study was supported by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute contract for the Framingham Heart Study (Contract No. N01-HC-25195, No. HHSN268201500001I, and No. 75N92019D00031), the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG054076, R01 AG049607, U01 AG052409, R01 AG059421, RF1 AG063507, RF1 AG066524, and U01 AG058589) and the National Institute of Neurologic Disorders and Stroke (R01 NS017950 and UH2 NS100605). Dr. Satizabal was supported by a New Investigator Research Grant to promote Diversity from the Alzheimer's Association (AARGD-16-443384) and also receives support from R01 AG059727, and UF1 NS125513. Dr. Himali is partly supported by AG062531 and by an endowment from the William Castella family as William Castella Distinguished University Chair for Alzheimer's Disease Research. Dr. Melo van Lent reports funding from R03 AG067062, the C. Richard Fleming grant and the Daniel H. Teitelbaum grant. Dr. Aparicio was supported by an American Academy of Neurology Career Development Award, Alzheimer's Association Research Grant (AARGD-20-685362), and Boston University's Aram V. Chobanian Assistant Professorship. Dr. DeCarli reports funding from P30 AG0101029. Drs. Satizabal, Himali, and Seshadri report funding from P30 AG066546. Drs. Seshadri and Himali are partially supported by the Bill and Rebecca Reed Endowment for Precision Therapies and Palliative Care. Dr. Seshadri is also supported by an endowment from the Barker Foundation as the Robert R. Barker Distinguished University Professor of Neurology, Psychiatry and Cellular and Integrative Physiology.

Disclosures

Dr. C.L. Satizabal reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. J.J. Himali reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. A.S. Beiser reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. R.S. Vasan reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. D. Melo van Lent reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. H.J. Aparicio reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. P. Maillard reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript; Dr. C. DeCarli serves as a consultant of Novartis Pharmaceuticals although this is not relevant to the manuscript Dr. W.S. Harris holds stock in OmegaQuant Analytics LLC, and in Brainspan LLC; Dr. S. Seshadri reports consulting for Eisai and Biogen although this is not relevant to the manuscript. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Jennings A, Cunnane SC, Minihane AM. Can nutrition support healthy cognitive ageing and reduce dementia risk? Bmj. 2020;369:m2269. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tan ZS, Harris WS, Beiser AS, et al. Red blood cell omega-3 fatty acid levels and markers of accelerated brain aging. Neurology. 2012;78(9):658-664. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318249f6a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pottala JV, Yaffe K, Robinson JG, Espeland MA, Wallace R, Harris WS. Higher RBC EPA + DHA corresponds with larger total brain and hippocampal volumes: WHIMS-MRI study. Neurology. 2014;82(5):435-442. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Raji CA, Erickson KI, Lopez OL, et al. Regular fish consumption and age-related brain gray matter loss. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47(4):444-451. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.05.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Samieri C, Maillard P, Crivello F, et al. Plasma long-chain omega-3 fatty acids and atrophy of the medial temporal lobe. Neurology. 2012;79(7):642-650. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e318264e394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Virtanen JK, Siscovick DS, Lemaitre RN, et al. Circulating omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and subclinical brain abnormalities on MRI in older adults: the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(5):e000305. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.113.000305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nishihira J, Tokashiki T, Higashiuesato Y, et al. Associations between serum omega-3 fatty acid levels and cognitive functions among community-dwelling octogenarians in okinawa, Japan: the KOCOA study. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2016;51(3):857-866. doi: 10.3233/JAD-150910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomas A, Baillet M, Proust-Lima C, et al. Blood polyunsaturated omega-3 fatty acids, brain atrophy, cognitive decline, and dementia risk. Alzheimer's Demen. 2021;17(3):407-416. doi: 10.1002/alz.12195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gustafson DR, Bäckman K, Scarmeas N, et al. Dietary fatty acids and risk of Alzheimer's disease and related dementias: observations from the Washington heights-Hamilton heights-inwood Columbia aging project (WHICAP). Alzheimer's Demen. 2020;16(12):1638-1649. doi: 10.1002/alz.12154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andrieu S, Guyonnet S, Coley N, et al. Effect of long-term omega 3 polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation with or without multidomain intervention on cognitive function in elderly adults with memory complaints (MAPT): a randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(5):377-389. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30040-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haider S, Schwarzinger A, Stefanac S, et al. Nutritional supplements for neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2020;35(11):1285-1291. doi: 10.1002/gps.5407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yassine HN. Targeting prodromal Alzheimer's disease: too late for prevention? Lancet Neurol. 2017;16(12):946-947. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(17)30372-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mahley RW. Apolipoprotein E: cholesterol transport protein with expanding role in cell biology. Science. 1988;240(4852):622-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vandal M, Alata W, Tremblay C, et al. Reduction in DHA transport to the brain of mice expressing human APOE4 compared to APOE2. J Neurochem. 2014;129(3):516-526. doi: 10.1111/jnc.12640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yassine HN, Braskie MN, Mack WJ, et al. Association of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation with alzheimer disease stage in Apolipoprotein E epsilon4 carriers: a review. JAMA Neurol. 2017;74(3):339-347. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2016.4899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Satizabal CL, Samieri C, Davis-Plourde KL, et al. APOE and the association of fatty acids with the risk of stroke, coronary heart disease, and mortality. Stroke. 2018;49(12):2822-2829. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.022132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.de Rojas I, Moreno-Grau S, Tesi N, et al. Common variants in Alzheimer's disease and risk stratification by polygenic risk scores. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):3417. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-22491-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Splansky GL, Corey D, Yang Q, et al. The Third generation cohort of the national heart, Lung, and blood institute's Framingham heart study: design, recruitment, and initial examination. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165(11):1328-1335. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kannel WB, Feinleib M, McNamara PM, Garrison RJ, Castelli WP. An investigation of coronary heart disease in families. The Framingham offspring study. Am J Epidemiol. 1979;110(3):281-290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harris WS, Pottala JV, Vasan RS, Larson MG, Robins SJ. Changes in erythrocyte membrane trans and marine fatty acids between 1999 and 2006 in older Americans. J Nutr. 2012;142(7):1297-1303. doi: 10.3945/jn.112.158295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harris WS, Von Schacky C. The Omega-3 Index: a new risk factor for death from coronary heart disease? Prev Med. 2004;39(1):212-220. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fletcher E, Singh B, Harvey D, Carmichael O, DeCarli C. Adaptive image segmentation for robust measurement of longitudinal brain tissue change. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2012;2012(5319-5322. doi: 10.1109/EMBC.2012.6347195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Aljabar P, Heckemann RA, Hammers A, Hajnal JV, Rueckert D. Multi-atlas based segmentation of brain images: atlas selection and its effect on accuracy. NeuroImage. 2009;46(3):726-738. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.DeCarli C, Miller BL, Swan GE, et al. Predictors of brain morphology for the men of the NHLBI twin study. Stroke. 1999;30(3):529-536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ahl RE, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Auerbach S, Wolf PA, Au R. Defining MCI in the Framingham heart study offspring: education versus WRAT-based norms. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2013;27(4):330-336. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e31827bde32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manly JJ, Jacobs DM, Touradji P, Small SA, Stern Y. Reading level attenuates differences in neuropsychological test performance between African American and White elders. J Int Neuropsychological Soc. 2002;8(3):341-348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.O'Bryant SE, Schrimsher GW, O'Jile JR. Discrepancies between self-reported years of education and estimated reading level: potential implications for neuropsychologists. Appl Neuropsychol. 2005;12(1):5-11. doi: 10.1207/s15324826an1201_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langlois K, Ratnayake WM. Omega-3 index of Canadian adults. Health Rep. 2015;26(11):3-11; doi. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Abedi E, Sahari MA. Long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acid sources and evaluation of their nutritional and functional properties. Food Sci Nutr. 2014;2(5):443-463. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ouellet M, Emond V, Chen CT, et al. Diffusion of docosahexaenoic and eicosapentaenoic acids through the blood-brain barrier: an in situ cerebral perfusion study. Neurochem Int. 2009;55(7):476-482. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2009.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang W, Chen R, Yang T, et al. Fatty acid transporting proteins: roles in brain development, aging, and stroke. Prostaglandins, Leukot Essent fatty Acids. 2018;136(35-45. doi: 10.1016/j.plefa.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bazinet RP, Laye S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(12):771-785. doi: 10.1038/nrn3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen C, Xun P, Kaufman JD, et al. Erythrocyte omega-3 index, ambient fine particle exposure, and brain aging. Neurology. 2020;95(8):e995-e1007. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muldoon MF, Ryan CM, Sheu L, Yao JK, Conklin SM, Manuck SB. Serum phospholipid docosahexaenonic acid is associated with cognitive functioning during middle adulthood. J Nutr. 2010;140(4):848-853. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.119578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van der Lee SJ, Teunissen CE, Pool R, et al. Circulating metabolites and general cognitive ability and dementia: evidence from 11 cohort studies. Alzheimer's Demen. 2018;14(6):707-722. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2017.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aryal S, Hussain S, Drevon CA, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids regulate plasticity in distinct hippocampal glutamatergic synapses. Eur J Neurosci. 2019;49(1):40-50. doi: 10.1111/ejn.14224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cutuli D, De Bartolo P, Caporali P, et al. n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation enhances hippocampal functionality in aged mice. Front Aging Neurosci. 2014;6:220. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2014.00220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quinn JF, Raman R, Thomas RG, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation and cognitive decline in Alzheimer disease: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2010;304(17):1903-1911. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lin PY, Cheng C, Satyanarayanan SK, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and blood-based biomarkers in Alzheimer's disease and mild cognitive impairment: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Brain Behav Immun. 2022;99(289-298. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2021.10.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Freund-Levi Y, Eriksdotter-Jonhagen M, Cederholm T, et al. Omega-3 fatty acid treatment in 174 patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer disease: OmegAD study: a randomized double-blind trial. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(10):1402-1408. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.10.1402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Witte AV, Kerti L, Hermannstadter HM, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids improve brain function and structure in older adults. Cereb Cortex. 2014;24(11):3059-3068. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Soininen H, Solomon A, Visser PJ, et al. 36-month LipiDiDiet multinutrient clinical trial in prodromal Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's & dementia : J Alzheimer's Assoc. 2021;17(1):29-40. doi: 10.1002/alz.12172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobe T, Witte AV, Schnelle A, et al. Combined omega-3 fatty acids, aerobic exercise and cognitive stimulation prevents decline in gray matter volume of the frontal, parietal and cingulate cortex in patients with mild cognitive impairment. NeuroImage. 2016;131:226-238. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2015.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arellanes IC, Choe N, Solomon V, et al. Brain delivery of supplemental docosahexaenoic acid (DHA): a randomized placebo-controlled clinical trial. EBioMedicine. 2020;59:102883. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2020.102883 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Crivello F, Lemaitre H, Dufouil C, et al. Effects of ApoE-epsilon4 allele load and age on the rates of grey matter and hippocampal volumes loss in a longitudinal cohort of 1186 healthy elderly persons. NeuroImage. 2010;53(3):1064-1069. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.12.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schuff N, Woerner N, Boreta L, et al. MRI of hippocampal volume loss in early Alzheimer's disease in relation to ApoE genotype and biomarkers. Brain. 2009;132(Pt 4):1067-1077. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Montagne A, Nation DA, Zlokovic BV. APOE4 accelerates development of dementia after stroke: is There a role for cerebrovascular dysfunction? Stroke. 2020;51(3):699-700. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.028814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yassine HN, Rawat V, Mack WJ, et al. The effect of APOE genotype on the delivery of DHA to cerebrospinal fluid in Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimer's Res Ther. 2016;8:25. doi: 10.1186/s13195-016-0194-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tomaszewski N, He X, Solomon V, et al. Effect of APOE genotype on plasma docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), eicosapentaenoic acid, arachidonic acid, and hippocampal volume in the Alzheimer's disease cooperative study-sponsored DHA clinical trial. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2020;74(3):975-990. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.van de Rest O, Wang Y, Barnes LL, Tangney C, Bennett DA, Morris MC. APOE epsilon4 and the associations of seafood and long-chain omega-3 fatty acids with cognitive decline. Neurology. 2016;86(22):2063-2070. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The eReferences (e1–e11) are available at links.lww.com/WNL/C319.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Deidentified data are available through formal data request application procedures by qualified investigators. More information is presented in framinghamheartstudy.org or biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/studies/framcohort/.