There is world-wide concern about psychological distress associated with COVID-19 amongst staff in healthcare settings, reflecting anxiety about personal and family infection, stress from triage with strained medical resources, and difficulty coping with social isolation and disruption to homelife [[1], [2], [3]]. A meta-analysis of 13 studies published by mid-April 2020 found 23% of respondents reporting significant, albeit mild, symptoms of anxiety or depression [4]. While most literature focusses on heightened distress, Pies [5] highlighted the importance of distinguishing elevated symptoms from mental health disorders, and concern about characterizing emotional responses to COVID-19 as a ‘mental health pandemic’.

Toronto's University Health Network (UHN), the largest academic hospital network in Canada, mounted new resources in anticipation of staff needs in March 2020. These include enhanced communication and rapid enabling of work-from-home, wellness options (e.g., peer-support-line, respite centres), and mental health resources with self-directed content (curated infographics and videos) and pro bono 1:1 care by UHN Psychiatrists and Psychologists. In June, a brief survey was sent to all staff that assessed symptoms of distress as well as potential drivers and protective factors. We also probed utilization of mental health and wellness resources, internal and external to UHN, and current work settings, occupations, and homelife variables. Our quality improvement (QI) aims were to assess barriers to use of resources and potential for improvement.

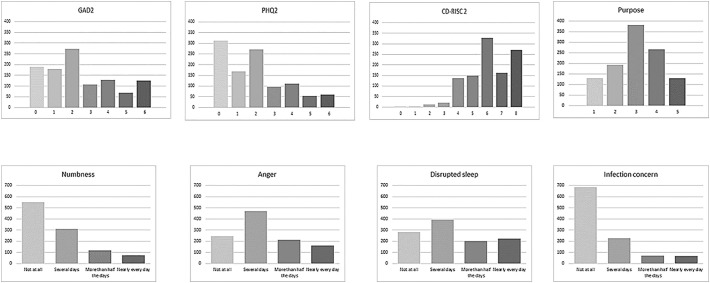

There were 1013 respondents with complete data. Specifics of methodology (survey distribution, questions, analyses) and detailed results are provided in Supplementary Materials. We achieved a broad representation of occupations (clinical, administrative, research) and work situations (work-from-home, typical clinical, redeployed). Fig. 1 shows descriptive results for the mental health symptoms and protective factors. Using cut-off scores of ≥3 on GAD-2 and PHQ-2, we found symptom elevation in 47% of respondents on one or both measures, but overall mean ratings were below cut-offs. As to protective factors, the sample demonstrated high resilience on the CD-RISC2 and 36% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that they felt ‘increased meaning and sense of purpose’ in their work during the pandemic.

Fig. 1.

Reponses to mental health/wellness questions. Response options for GAD-2 and PHQ-2 are: 0)not at all, 1)several days, 2)more than half the days, 3)nearly every day with 2 questions contributing to total score of 0–6. Responses for CD-RISC2 are: 0)not true at all, 1)rarely true, 2)sometimes true, 3)often true, 4)true nearly all the time with 2 questions contributing to total score of 0–8. Responses for purpose are: 1)strongly disagree, 2)disagree, 3)neutral, 4)agree, 5)strongly agree that during the pandemic I have felt increased sense of meaning and purpose in my work. Items on the bottom row were all framed as frequency of these indicators over the past two weeks.

Statistical analyses revealed similar factors promoting and mitigating elevated symptoms of both anxiety and depression. The drivers are factors associated with perceived personal harm; workplace exposure as has been shown in other studies [6,7] and, less studied in this sector, concern about loss of household income. Our sample also demonstrated that resilience – the ability to maintain or regain mental health despite experiencing adversity - and enhanced sense of purpose [8] are key buffers against distress in this cohort. We did not find major differences amongst occupations and work settings in this survey. Intriguingly, those in administrative/support roles demonstrated both highest levels of anxiety, but also the largest elevation in sense of purpose, suggesting a high-risk/high-reward characterization. It may be that those roles required the most substantial changes in responsibilities and activities (e.g., new strategies required to resource PPE, nursing administrators redesigning wards and shifts, physician administrators informing anxious patients of cancelled investigations and treatments).

Fifty-four percent reported using some type of support for wellness/mental health (see Supplementary Materials), with the majority using either formal or informal resources available outside UHN. Factors associated with use of any resource included occupation (marginally higher amongst Nursing and Allied Health), work setting (highest in inpatient settings), and COVID-19 exposure (highest amongst those uncertain of their status). Importantly for our QI purpose, only 20% of respondents reported accessing our well-advertised mental health program and wellness offerings, with only 1% accessing 1:1 psychiatric and/or psychological intervention, 3% using the self-directed infographics and videos, and 16% utilizing the wellness options (e.g., respite centres, peer-support line). Individuals seeking some form of assistance did not avail themselves of UHN wellness/mental health resources due mainly to lack of knowledge about the offerings, being too busy, or having sufficient outside resources, but not because of privacy concerns. Thus, a clear recommendation for institutions during current COVID-19 waves and beyond is to ensure wide promotion of available resources, and provision of resources like infographics, videos, peer support and respite areas, that can be readily disseminated and incorporated into very busy professional practices.

Study limitations include a modest response rate, the possibility that email distribution missed potential respondents, and use of brief generic screening measures GAD-2 and PHQ-2 that may not capture dimensions of psychological distress. Nonetheless, our findings suggest that enhanced communication and strategies to enhance resilience and sense of purpose in work offer opportunities to mitigate distress in meeting the challenges of coping with COVID-19 in healthcare settings, particularly if they can be integrated seamlessly into busy work schedules. It must be understood that resilience is not only about personal resources, but about the interaction of these with the environment and systems [9]. The opposing effects of infection concern and resilience underscores the importance of effective, transparent, and timely communication about the virus and work precautions and expectations by the organization [10]. Also, it is important to recognize that other workers, beyond frontline clinical staff, must be considered. Finally, expressions of gratitude within the organization and general pubic (e.g., ‘heroes recognition’ events) likely contribute to individuals' inherent sense of purpose in rising to new challenges.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.11.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material.

References

- 1.Qui J., Shen B., Zhao M., Wang Z., Xie B., Yu Y. A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(2) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Teng Z., et al. Psychological status and fatigue of frontline staff two months after the COVID-19 pandemic outbreak in China: a cross-sectional study. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:247–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang S.X., et al. Unprecedented disruption of lives and work: health, distress and life satisfaction of working adults in China one month into the COVID-19 outbreak. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112958. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pappa S., et al. Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:901–907. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pies R.W. Psychiatric Times; 2020. Are we really witnessing a “mental health pandemic?”. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lu W., et al. Psychological status of medical workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study. Psychiatry Res. 2020;288:112936. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu C.Y., et al. The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: a cross-sectional survey. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148 doi: 10.1017/S0950268820001107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shechter A., et al. Psychological distress, coping behaviors, and preferences for support among New York healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2020;66:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2020.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herrman H., et al. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(5):258–265. doi: 10.1177/070674371105600504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heath C., Sommerfield A., von Ungern-Sternberg B.S. Resilience strategies to manage psychological distress among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a narrative review. Anaesthesia. 2020;75(10):1364–1371. doi: 10.1111/anae.15180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material.